Targeting Cardiac Stem Cell Senescence to Treat Cardiac Aging and Disease

Abstract

1. Introduction

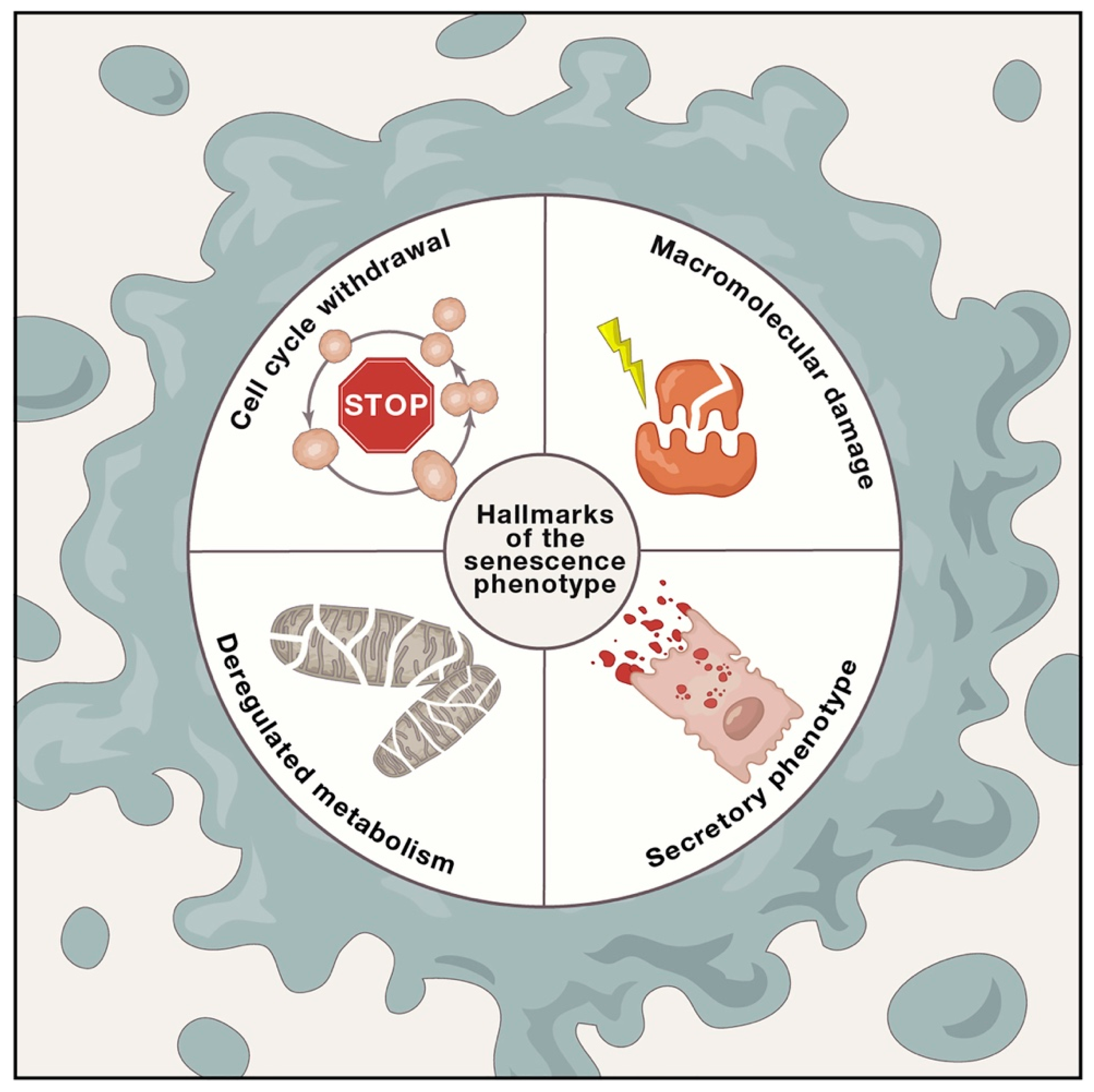

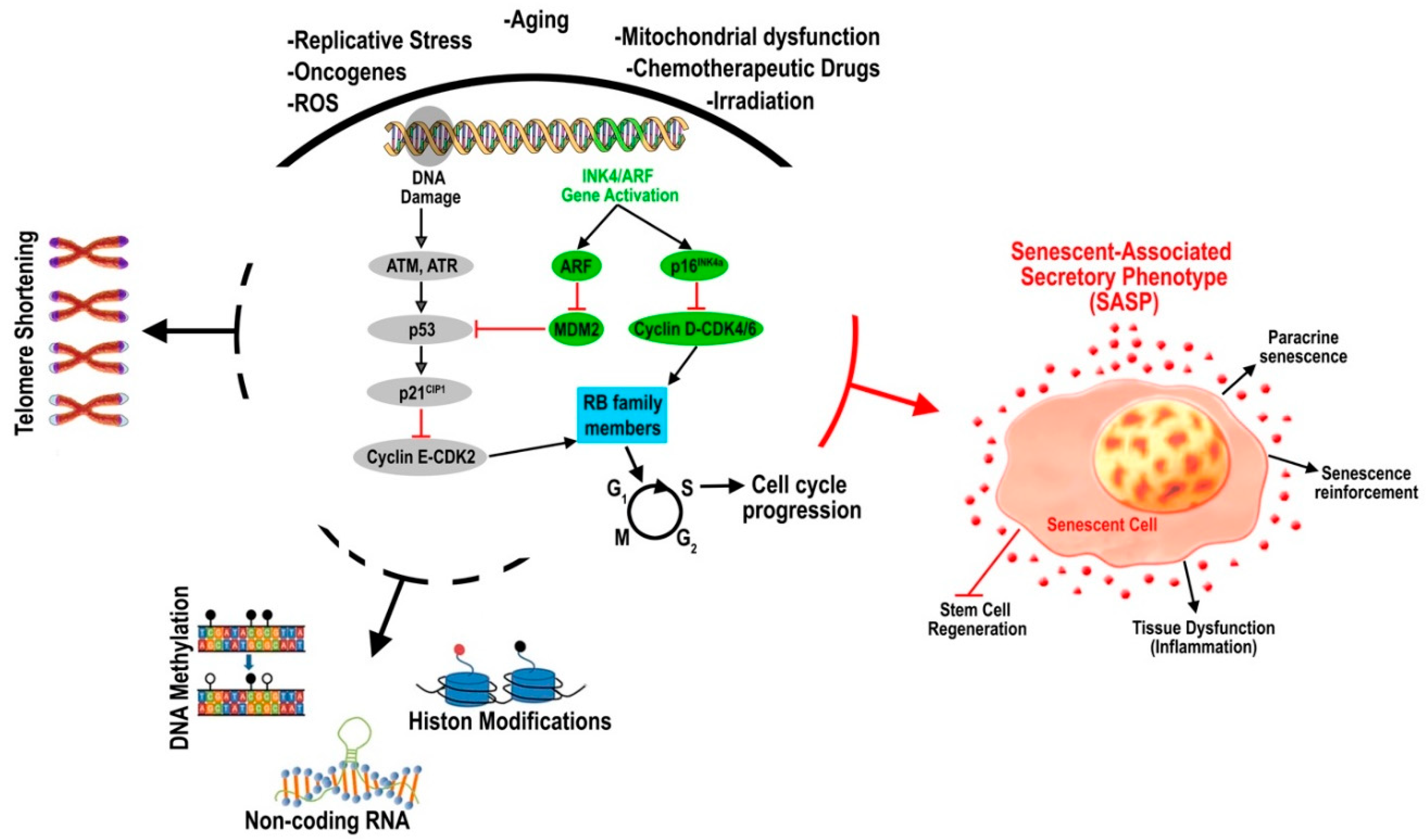

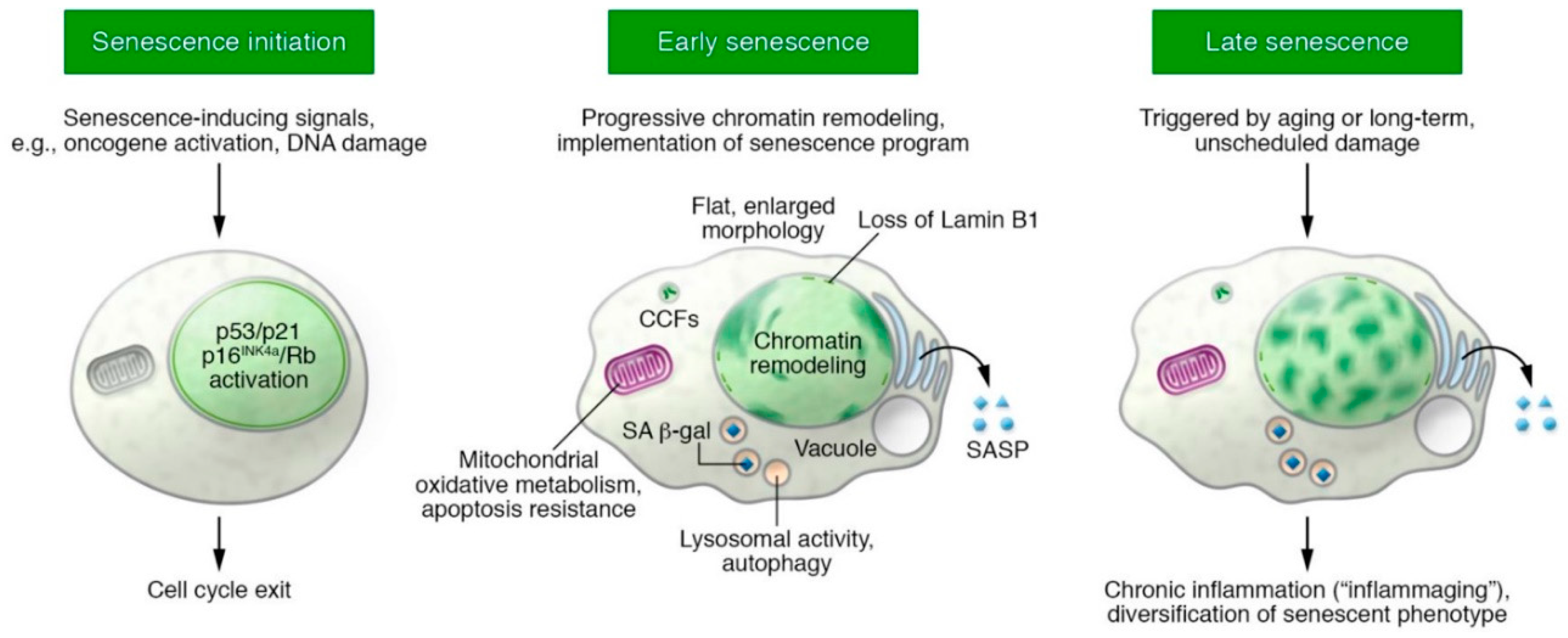

2. Molecular Mechanisms of Adult Stem Cell Senescence and Aging

3. SASP and Stem Cell Senescence and Aging

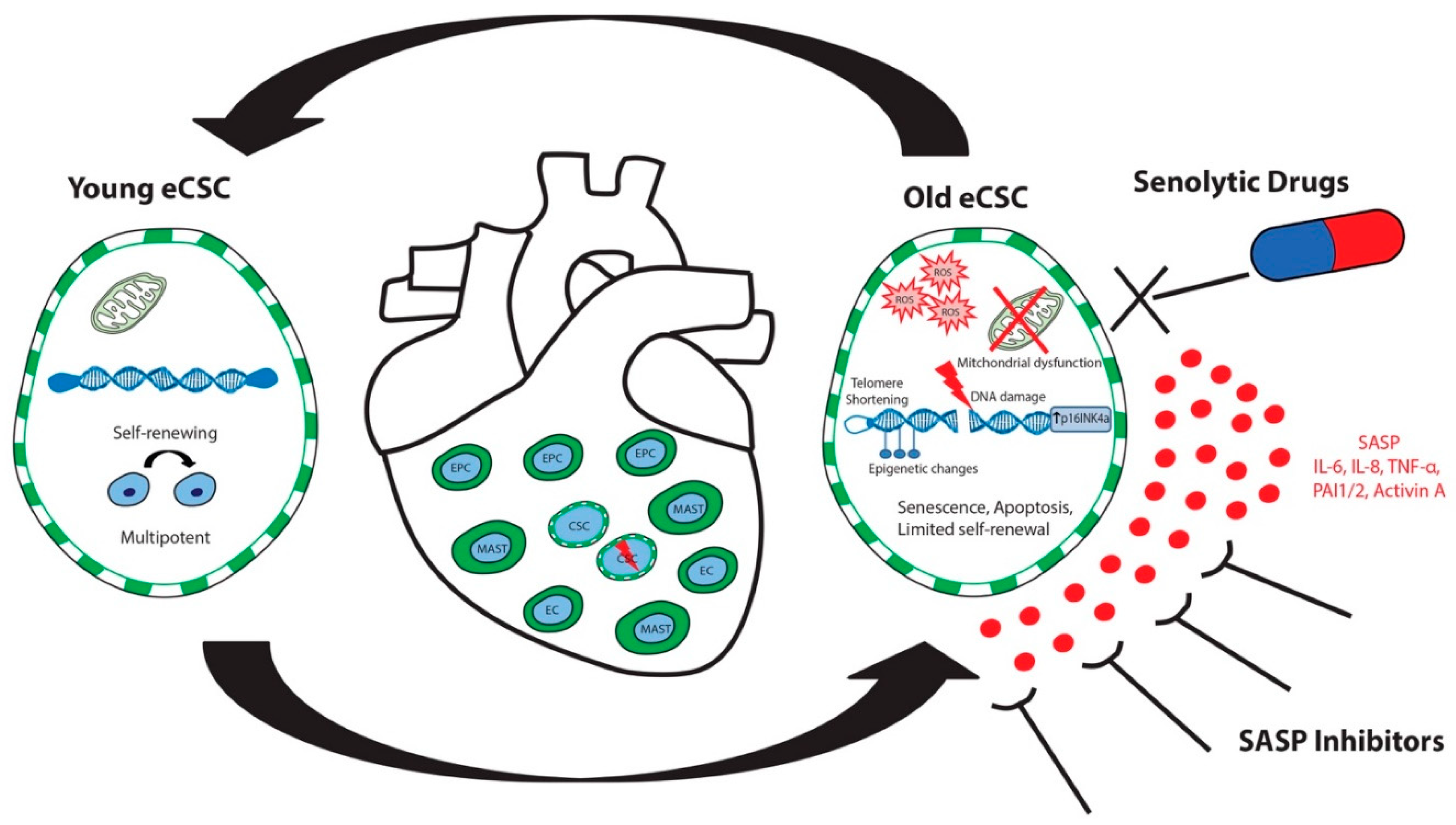

4. Cardiac Stem Cell Senescence

5. Cardiac Stem/Progenitor Cell SASP

6. CSC Senescence and Diabetic Cardiomyopathy

7. CSC Senescence and Anthracycline Cardiomyopathy

8. Is CSC Intrinsic Senescence Reversible?

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gorgoulis, V.; Adams, P.D.; Alimonti, A.; Bennett, D.C.; Bischof, O.; Bishop, C.; Campisi, J.; Collado, M.; Evangelou, K.; Ferbeyre, G.; et al. Cellular Senescence: Defining a Path Forward. Cell 2019, 179, 813–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Schmitt, C.A. The dynamic nature of senescence in cancer. Nat. Cell Biol. 2019, 21, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayflick, L.; Moorhead, P.S. The serial cultivation of human diploid cell strains. Exp. Cell Res. 1961, 25, 585–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Childs, B.G.; Durik, M.; Baker, D.J.; van Deursen, J.M. Cellular senescence in aging and age-related disease: From mechanisms to therapy. Nat. Med. 2015, 21, 1424–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shay, J.W. Role of Telomeres and Telomerase in Aging and Cancer. Cancer Discov. 2016, 6, 584–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppé, J.-P.; Kauser, K.; Campisi, J.; Beauséjour, C.M. Secretion of vascular endothelial growth factor by primary human fibroblasts at senescence. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 29568–29574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkland, J.L.; Tchkonia, T. Cellular Senescence: A Translational Perspective. EBioMedicine 2017, 21, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faget, D.V.; Ren, Q.; Stewart, S.A. Unmasking senescence: Context-dependent effects of SASP in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2019, 19, 439–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiley, C.D.; Campisi, J. From Ancient Pathways to Aging Cells-Connecting Metabolism and Cellular Senescence. Cell Metab. 2016, 23, 1013–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Espín, D.; Serrano, M. Cellular senescence: From physiology to pathology. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2014, 15, 482–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, P.D. Healing and hurting: Molecular mechanisms, functions, and pathologies of cellular senescence. Mol. Cell 2009, 36, 2–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campisi, J. Aging, cellular senescence, and cancer. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2013, 75, 685–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Mancera, P.A.; Young, A.R.J.; Narita, M. Inside and out: The activities of senescence in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2014, 14, 547–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cable, J.; Fuchs, E.; Weissman, I.; Jasper, H.; Glass, D.; Rando, T.A.; Blau, H.; Debnath, S.; Oliva, A.; Park, S.; et al. Adult stem cells and regenerative medicine-a symposium report. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2020, 1462, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinho, S.; Frenette, P.S. Haematopoietic stem cell activity and interactions with the niche. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2019, 20, 303–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almada, A.E.; Wagers, A.J. Molecular circuitry of stem cell fate in skeletal muscle regeneration, ageing and disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2016, 17, 267–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obernier, K.; Alvarez-Buylla, A. Neural stem cells: Origin, heterogeneity and regulation in the adult mammalian brain. Development 2019, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehart, H.; Clevers, H. Tales from the crypt: New insights into intestinal stem cells. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 16, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, E. Skin Stem Cells in Silence, Action, and Cancer. Stem Cell Rep. 2018, 10, 1432–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ermolaeva, M.; Neri, F.; Ori, A.; Rudolph, K.L. Cellular and epigenetic drivers of stem cell ageing. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2018, 19, 594–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, M.B.; Sinclair, D.A. When stem cells grow old: Phenotypes and mechanisms of stem cell aging. Development 2016, 143, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tümpel, S.; Rudolph, K.L. Quiescence: Good and Bad of Stem Cell Aging. Trends Cell Biol. 2019, 29, 672–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yankner, B.A.; Lu, T.; Loerch, P. The aging brain. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2008, 3, 41–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gude, N.A.; Broughton, K.M.; Firouzi, F.; Sussman, M.A. Cardiac ageing: Extrinsic and intrinsic factors in cellular renewal and senescence. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2018, 15, 523–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gage, F.H. Adult neurogenesis in mammals. Science 2019, 364, 827–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalamakis, G.; Brüne, D.; Ravichandran, S.; Bolz, J.; Fan, W.; Ziebell, F.; Stiehl, T.; Catalá-Martinez, F.; Kupke, J.; Zhao, S.; et al. Quiescence Modulates Stem Cell Maintenance and Regenerative Capacity in the Aging Brain. Cell 2019, 176, 1407–1419.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torella, D.; Rota, M.; Nurzynska, D.; Musso, E.; Monsen, A.; Shiraishi, I.; Zias, E.; Walsh, K.; Rosenzweig, A.; Sussman, M.A.; et al. Cardiac Stem Cell and Myocyte Aging, Heart Failure, and Insulin-Like Growth Factor-1 Overexpression. Circ. Res. 2004, 94, 514–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cianflone, E.; Torella, M.; Chimenti, C.; De Angelis, A.; Beltrami, A.P.; Urbanek, K.; Rota, M.; Torella, D. Adult Cardiac Stem Cell Aging: A Reversible Stochastic Phenomenon? Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 5813147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis-McDougall, F.C.; Ruchaya, P.J.; Domenjo-Vila, E.; Shin Teoh, T.; Prata, L.; Cottle, B.J.; Clark, J.E.; Punjabi, P.P.; Awad, W.; Torella, D.; et al. Aged-senescent cells contribute to impaired heart regeneration. Aging Cell 2019, 18, e12931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, I.; Minamino, T. Cellular senescence in cardiac diseases. J. Cardiol. 2019, 74, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodier, F.; Campisi, J. Four faces of cellular senescence. J. Cell Biol. 2011, 192, 547–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharpless, N.E.; Sherr, C.J. Forging a signature of in vivo senescence. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2015, 15, 397–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuilman, T.; Michaloglou, C.; Mooi, W.J.; Peeper, D.S. The essence of senescence. Genes Dev. 2010, 24, 2463–2479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Zamudio, R.I.; Robinson, L.; Roux, P.-F.; Bischof, O. SnapShot: Cellular Senescence Pathways. Cell 2017, 170, 816–816.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narita, M.; Nũnez, S.; Heard, E.; Narita, M.; Lin, A.W.; Hearn, S.A.; Spector, D.L.; Hannon, G.J.; Lowe, S.W. Rb-mediated heterochromatin formation and silencing of E2F target genes during cellular senescence. Cell 2003, 113, 703–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, M.; Lin, A.W.; McCurrach, M.E.; Beach, D.; Lowe, S.W. Oncogenic Ras Provokes Premature Cell Senescence Associated with Accumulation of p53 and p16INK4a. Cell 1997, 88, S0092–S8674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benhamed, M.; Herbig, U.; Ye, T.; Dejean, A.; Bischof, O. Senescence is an endogenous trigger for microRNA-directed transcriptional gene silencing in human cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 2012, 14, 266–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrón, S.R.; Marqués-Torrejón, M.A.; Mira, H.; Flores, I.; Taylor, K.; Blasco, M.A.; Fariñas, I. Telomere shortening in neural stem cells disrupts neuronal differentiation and neuritogenesis. J. Neurosci. 2009, 29, 14394–14407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, I.; Canela, A.; Vera, E.; Tejera, A.; Cotsarelis, G.; Blasco, M.A. The longest telomeres: A general signature of adult stem cell compartments. Genes Dev. 2008, 22, 654–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardes de Jesus, B.; Vera, E.; Schneeberger, K.; Tejera, A.M.; Ayuso, E.; Bosch, F.; Blasco, M.A. Telomerase gene therapy in adult and old mice delays aging and increases longevity without increasing cancer. Embo Mol. Med. 2012, 4, 691–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomás-Loba, A.; Flores, I.; Fernández-Marcos, P.J.; Cayuela, M.L.; Maraver, A.; Tejera, A.; Borrás, C.; Matheu, A.; Klatt, P.; Flores, J.M.; et al. Telomerase reverse transcriptase delays aging in cancer-resistant mice. Cell 2008, 135, 609–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ju, Z.; Jiang, H.; Jaworski, M.; Rathinam, C.; Gompf, A.; Klein, C.; Trumpp, A.; Rudolph, K.L. Telomere dysfunction induces environmental alterations limiting hematopoietic stem cell function and engraftment. Nat. Med. 2007, 13, 742–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Sung, Y.H.; Cheong, C.; Choi, Y.S.; Jeon, H.K.; Sun, W.; Hahn, W.C.; Ishikawa, F.; Lee, H.-W. TERT promotes cellular and organismal survival independently of telomerase activity. Oncogene 2008, 27, 3754–3760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, Y.; Gerson, S.L. DNA repair defects in stem cell function and aging. Annu. Rev. Med. 2005, 56, 495–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beerman, I.; Seita, J.; Inlay, M.A.; Weissman, I.L.; Rossi, D.J. Quiescent hematopoietic stem cells accumulate DNA damage during aging that is repaired upon entry into cell cycle. Cell Stem Cell 2014, 15, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rübe, C.E.; Fricke, A.; Widmann, T.A.; Fürst, T.; Madry, H.; Pfreundschuh, M.; Rübe, C. Accumulation of DNA damage in hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells during human aging. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e17487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, A.; Hughes, K.R.; Modrzynska, K.K.; Otto, T.D.; Pfander, C.; Dickens, N.J.; Religa, A.A.; Bushell, E.; Graham, A.L.; Cameron, R.; et al. A cascade of DNA-binding proteins for sexual commitment and development in Plasmodium. Nature 2014, 507, 253–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flach, J.; Bakker, S.T.; Mohrin, M.; Conroy, P.C.; Pietras, E.M.; Reynaud, D.; Alvarez, S.; Diolaiti, M.E.; Ugarte, F.; Forsberg, E.C.; et al. Replication stress is a potent driver of functional decline in ageing haematopoietic stem cells. Nature 2014, 512, 198–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasetti, C.; Vogelstein, B. Cancer etiology. Variation in cancer risk among tissues can be explained by the number of stem cell divisions. Science 2015, 347, 78–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Velthoven, C.T.J.; Rando, T.A. Stem Cell Quiescence: Dynamism, Restraint, and Cellular Idling. Cell Stem Cell 2019, 24, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanaar, R.; Wyman, C. DNA repair by the MRN complex: Break it to make it. Cell 2008, 135, 14–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohrin, M.; Bourke, E.; Alexander, D.; Warr, M.R.; Barry-Holson, K.; Le Beau, M.M.; Morrison, C.G.; Passegué, E. Hematopoietic stem cell quiescence promotes error-prone DNA repair and mutagenesis. Cell Stem Cell 2010, 7, 174–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walter, D.; Lier, A.; Geiselhart, A.; Thalheimer, F.B.; Huntscha, S.; Sobotta, M.C.; Moehrle, B.; Brocks, D.; Bayindir, I.; Kaschutnig, P.; et al. Exit from dormancy provokes DNA-damage-induced attrition in haematopoietic stem cells. Nature 2015, 520, 549–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, S.; Ebert, B.L. Clonal hematopoiesis in human aging and disease. Science 2019, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corces-Zimmerman, M.R.; Hong, W.-J.; Weissman, I.L.; Medeiros, B.C.; Majeti, R. Preleukemic mutations in human acute myeloid leukemia affect epigenetic regulators and persist in remission. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 2548–2553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, S.; Fontanillas, P.; Flannick, J.; Manning, A.; Grauman, P.V.; Mar, B.G.; Lindsley, R.C.; Mermel, C.H.; Burtt, N.; Chavez, A.; et al. Age-related clonal hematopoiesis associated with adverse outcomes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 2488–2498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genovese, G.; Kähler, A.K.; Handsaker, R.E.; Lindberg, J.; Rose, S.A.; Bakhoum, S.F.; Chambert, K.; Mick, E.; Neale, B.M.; Fromer, M.; et al. Clonal hematopoiesis and blood-cancer risk inferred from blood DNA sequence. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 2477–2487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jan, M.; Snyder, T.M.; Corces-Zimmerman, M.R.; Vyas, P.; Weissman, I.L.; Quake, S.R.; Majeti, R. Clonal evolution of preleukemic hematopoietic stem cells precedes human acute myeloid leukemia. Sci. Transl. Med. 2012, 4, 149ra118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waddington, C.H. The epigenotype. 1942. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2012, 41, 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, K.; Xu, L.; Wang, E. Quantifying the Waddington landscape and biological paths for development and differentiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 8257–8262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, B.E.; Mikkelsen, T.S.; Xie, X.; Kamal, M.; Huebert, D.J.; Cuff, J.; Fry, B.; Meissner, A.; Wernig, M.; Plath, K.; et al. A bivalent chromatin structure marks key developmental genes in embryonic stem cells. Cell 2006, 125, 315–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; Fernandez-Cid, A.; Riera, A.; Tognetti, S.; Yuan, Z.; Stillman, B.; Speck, C.; Li, H. Structural and mechanistic insights into Mcm2-7 double-hexamer assembly and function. Genes Dev. 2014, 28, 2291–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Florian, M.C.; Dörr, K.; Niebel, A.; Daria, D.; Schrezenmeier, H.; Rojewski, M.; Filippi, M.-D.; Hasenberg, A.; Gunzer, M.; Scharffetter-Kochanek, K.; et al. Cdc42 activity regulates hematopoietic stem cell aging and rejuvenation. Cell Stem Cell 2012, 10, 520–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, G.; Mattick, J.S.; Taft, R.J. A meta-analysis of the genomic and transcriptomic composition of complex life. Cell Cycle 2013, 12, 2061–2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, I.; Silva, J.; Colby, D.; Nichols, J.; Nijmeijer, B.; Robertson, M.; Vrana, J.; Jones, K.; Grotewold, L.; Smith, A. Nanog safeguards pluripotency and mediates germline development. Nature 2007, 450, 1230–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kofman, A.E.; Huszar, J.M.; Payne, C.J. Transcriptional analysis of histone deacetylase family members reveal similarities between differentiating and aging spermatogonial stem cells. Stem Cell Rev. Rep. 2013, 9, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, D.J.; Bryder, D.; Zahn, J.M.; Ahlenius, H.; Sonu, R.; Wagers, A.J.; Weissman, I.L. Cell intrinsic alterations underlie hematopoietic stem cell aging. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 9194–9199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-C.; Carson, J.J.; Feser, J.; Tamburini, B.; Zabaronick, S.; Linger, J.; Tyler, J.K. Acetylated lysine 56 on histone H3 drives chromatin assembly after repair and signals for the completion of repair. Cell 2008, 134, 231–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberdoerffer, P.; Michan, S.; McVay, M.; Mostoslavsky, R.; Vann, J.; Park, S.-K.; Hartlerode, A.; Stegmuller, J.; Hafner, A.; Loerch, P.; et al. SIRT1 redistribution on chromatin promotes genomic stability but alters gene expression during aging. Cell 2008, 135, 907–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beerman, I.; Bock, C.; Garrison, B.S.; Smith, Z.D.; Gu, H.; Meissner, A.; Rossi, D.J. Proliferation-dependent alterations of the DNA methylation landscape underlie hematopoietic stem cell aging. Cell Stem Cell 2013, 12, 413–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oakley, E.J.; Van Zant, G. Unraveling the complex regulation of stem cells: Implications for aging and cancer. Leukemia 2007, 21, 612–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyer, L.A.; Plath, K.; Zeitlinger, J.; Brambrink, T.; Medeiros, L.A.; Lee, T.I.; Levine, S.S.; Wernig, M.; Tajonar, A.; Ray, M.K.; et al. Polycomb complexes repress developmental regulators in murine embryonic stem cells. Nature 2006, 441, 349–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, T.I.; Jenner, R.G.; Boyer, L.A.; Guenther, M.G.; Levine, S.S.; Kumar, R.M.; Chevalier, B.; Johnstone, S.E.; Cole, M.F.; Isono, K.; et al. Control of developmental regulators by Polycomb in human embryonic stem cells. Cell 2006, 125, 301–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamminga, L.M.; Bystrykh, L.V.; de Boer, A.; Houwer, S.; Douma, J.; Weersing, E.; Dontje, B.; de Haan, G. The Polycomb group gene Ezh2 prevents hematopoietic stem cell exhaustion. Blood 2006, 107, 2170–2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lessard, J.; Sauvageau, G. Bmi-1 determines the proliferative capacity of normal and leukaemic stem cells. Nature 2003, 423, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lessard, J.; Sauvageau, G. Polycomb group genes as epigenetic regulators of normal and leukemic hemopoiesis. Exp. Hematol. 2003, 31, 567–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirrotta, V. Polycombing the genome: PcG, trxG, and chromatin silencing. Cell 1998, 93, 333–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringrose, L.; Paro, R. Epigenetic regulation of cellular memory by the Polycomb and Trithorax group proteins. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2004, 38, 413–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirmizis, A.; Bartley, S.M.; Kuzmichev, A.; Margueron, R.; Reinberg, D.; Green, R.; Farnham, P.J. Silencing of human polycomb target genes is associated with methylation of histone H3 Lys 27. Genes Dev. 2004, 18, 1592–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, A.H.; van Lohuizen, M. Polycomb complexes and silencing mechanisms. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2004, 16, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czermin, B.; Melfi, R.; McCabe, D.; Seitz, V.; Imhof, A.; Pirrotta, V. Drosophila enhancer of Zeste/ESC complexes have a histone H3 methyltransferase activity that marks chromosomal Polycomb sites. Cell 2002, 111, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Z.; Raible, F.; Mollaaghababa, R.; Guyon, J.R.; Wu, C.T.; Bender, W.; Kingston, R.E. Stabilization of chromatin structure by PRC1, a Polycomb complex. Cell 1999, 98, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lessard, J.; Baban, S.; Sauvageau, G. Stage-specific expression of polycomb group genes in human bone marrow cells. Blood 1998, 91, 1216–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, I.; Qian, D.; Kiel, M.; Becker, M.W.; Pihalja, M.; Weissman, I.L.; Morrison, S.J.; Clarke, M.F. Bmi-1 is required for maintenance of adult self-renewing haematopoietic stem cells. Nature 2003, 423, 302–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharpless, N.E.; DePinho, R.A. The INK4A/ARF locus and its two gene products. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 1999, 9, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, J.J.; Kieboom, K.; Marino, S.; DePinho, R.A.; van Lohuizen, M. The oncogene and Polycomb-group gene bmi-1 regulates cell proliferation and senescence through the ink4a locus. Nature 1999, 397, 164–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobs, J.J.; Scheijen, B.; Voncken, J.W.; Kieboom, K.; Berns, A.; van Lohuizen, M. Bmi-1 collaborates with c-Myc in tumorigenesis by inhibiting c-Myc-induced apoptosis via INK4a/ARF. Genes Dev. 1999, 13, 2678–2690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itahana, K.; Zou, Y.; Itahana, Y.; Martinez, J.-L.; Beausejour, C.; Jacobs, J.J.L.; Van Lohuizen, M.; Band, V.; Campisi, J.; Dimri, G.P. Control of the replicative life span of human fibroblasts by p16 and the polycomb protein Bmi-1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003, 23, 389–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardal, R.; Molofsky, A.V.; He, S.; Morrison, S.J. Stem cell self-renewal and cancer cell proliferation are regulated by common networks that balance the activation of proto-oncogenes and tumor suppressors. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 2005, 70, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takubo, K.; Nagamatsu, G.; Kobayashi, C.I.; Nakamura-Ishizu, A.; Kobayashi, H.; Ikeda, E.; Goda, N.; Rahimi, Y.; Johnson, R.S.; Soga, T.; et al. Regulation of Glycolysis by Pdk Functions as a Metabolic Checkpoint for Cell Cycle Quiescence in Hematopoietic Stem Cells. Cell Stem Cell 2013, 12, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, J.M.; Esain, V.; Frechette, G.M.; Harris, L.J.; Cox, A.G.; Cortes, M.; Garnaas, M.K.; Carroll, K.J.; Cutting, C.C.; Khan, T.; et al. Glucose metabolism impacts the spatiotemporal onset and magnitude of HSC induction in vivo. Blood 2013, 121, 2483–2493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, W.-M.; Liu, X.; Shen, J.; Jovanovic, O.; Pohl, E.E.; Gerson, S.L.; Finkel, T.; Broxmeyer, H.E.; Qu, C.-K. Metabolic regulation by the mitochondrial phosphatase PTPMT1 is required for hematopoietic stem cell differentiation. Cell Stem Cell 2013, 12, 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pervaiz, S.; Taneja, R.; Ghaffari, S. Oxidative stress regulation of stem and progenitor cells. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2009, 11, 2777–2789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, J.; Lee, Y.D.; Wagers, A.J. Stem cell aging: Mechanisms, regulators and therapeutic opportunities. Nat. Med. 2014, 20, 870–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harman, D. Free radical theory of aging: Dietary implications. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1972, 25, 839–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolzing, A.; Jones, E.; McGonagle, D.; Scutt, A. Age-related changes in human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells: Consequences for cell therapies. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2008, 129, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, Y.-Y.; Sharkis, S.J. A low level of reactive oxygen species selects for primitive hematopoietic stem cells that may reside in the low-oxygenic niche. Blood 2007, 110, 3056–3063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tothova, Z.; Kollipara, R.; Huntly, B.J.; Lee, B.H.; Castrillon, D.H.; Cullen, D.E.; McDowell, E.P.; Lazo-Kallanian, S.; Williams, I.R.; Sears, C.; et al. FoxOs are critical mediators of hematopoietic stem cell resistance to physiologic oxidative stress. Cell 2007, 128, 325–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Grindley, J.C.; Yin, T.; Jayasinghe, S.; He, X.C.; Ross, J.T.; Haug, J.S.; Rupp, D.; Porter-Westpfahl, K.S.; Wiedemann, L.M.; et al. PTEN maintains haematopoietic stem cells and acts in lineage choice and leukaemia prevention. Nature 2006, 441, 518–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Liu, Y.; Liu, R.; Ikenoue, T.; Guan, K.-L.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, P. TSC-mTOR maintains quiescence and function of hematopoietic stem cells by repressing mitochondrial biogenesis and reactive oxygen species. J. Exp. Med. 2008, 205, 2397–2408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juntilla, M.M.; Patil, V.D.; Calamito, M.; Joshi, R.P.; Birnbaum, M.J.; Koretzky, G.A. AKT1 and AKT2 maintain hematopoietic stem cell function by regulating reactive oxygen species. Blood 2010, 115, 4030–4038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, K.; Hirao, A.; Arai, F.; Matsuoka, S.; Takubo, K.; Hamaguchi, I.; Nomiyama, K.; Hosokawa, K.; Sakurada, K.; Nakagata, N.; et al. Regulation of oxidative stress by ATM is required for self-renewal of haematopoietic stem cells. Nature 2004, 431, 997–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyamoto, K.; Araki, K.Y.; Naka, K.; Arai, F.; Takubo, K.; Yamazaki, S.; Matsuoka, S.; Miyamoto, T.; Ito, K.; Ohmura, M.; et al. Foxo3a is essential for maintenance of the hematopoietic stem cell pool. Cell Stem Cell 2007, 1, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, K.; Hirao, A.; Arai, F.; Takubo, K.; Matsuoka, S.; Miyamoto, K.; Ohmura, M.; Naka, K.; Hosokawa, K.; Ikeda, Y.; et al. Reactive oxygen species act through p38 MAPK to limit the lifespan of hematopoietic stem cells. Nat. Med. 2006, 12, 446–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.-F.; Zhai, C.; Yan, X.-L.; Zhao, D.-D.; Wang, J.-X.; Zeng, Q.; Chen, L.; Nan, X.; He, L.-J.; Li, S.-T.; et al. SIRT1 is required for long-term growth of human mesenchymal stem cells. J. Mol. Med. 2012, 90, 389–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Liu, X.; Chen, H.; Cao, J.; Zhang, L.; Hu, X.; Wang, J. Role of SIRT1 and AMPK in mesenchymal stem cells differentiation. Ageing Res. Rev. 2014, 13, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-S.; Patel, K.; Muldoon-Jacobs, K.; Bisht, K.S.; Aykin-Burns, N.; Pennington, J.D.; van der Meer, R.; Nguyen, P.; Savage, J.; Owens, K.M.; et al. SIRT3 is a mitochondria-localized tumor suppressor required for maintenance of mitochondrial integrity and metabolism during stress. Cancer Cell 2010, 17, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K.; Xie, S.; Qiu, X.; Mohrin, M.; Shin, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, D.; Scadden, D.T.; Chen, D. SIRT3 reverses aging-associated degeneration. Cell Rep. 2013, 3, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, R.; Ocampo, A.; Liu, G.-H.; Izpisua Belmonte, J.C. Regulation of Stem Cell Aging by Metabolism and Epigenetics. Cell Metab. 2017, 26, 460–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontana, L.; Partridge, L.; Longo, V.D. Extending healthy life span--from yeast to humans. Science 2010, 328, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, D.E.; Strong, R.; Sharp, Z.D.; Nelson, J.F.; Astle, C.M.; Flurkey, K.; Nadon, N.L.; Wilkinson, J.E.; Frenkel, K.; Carter, C.S.; et al. Rapamycin fed late in life extends lifespan in genetically heterogeneous mice. Nature 2009, 460, 392–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tatar, M.; Sedivy, J.M. Mitochondria: Masters of Epigenetics. Cell 2016, 165, 1052–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger, S.L.; Sassone-Corsi, P. Metabolic Signaling to Chromatin. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2016, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahlqvist, K.J.; Hämäläinen, R.H.; Yatsuga, S.; Uutela, M.; Terzioglu, M.; Götz, A.; Forsström, S.; Salven, P.; Angers-Loustau, A.; Kopra, O.H.; et al. Somatic progenitor cell vulnerability to mitochondrial DNA mutagenesis underlies progeroid phenotypes in Polg mutator mice. Cell Metab. 2012, 15, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colman, R.J.; Anderson, R.M.; Johnson, S.C.; Kastman, E.K.; Kosmatka, K.J.; Beasley, T.M.; Allison, D.B.; Cruzen, C.; Simmons, H.A.; Kemnitz, J.W.; et al. Caloric restriction delays disease onset and mortality in rhesus monkeys. Science 2009, 325, 201–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattison, J.A.; Roth, G.S.; Beasley, T.M.; Tilmont, E.M.; Handy, A.M.; Herbert, R.L.; Longo, D.L.; Allison, D.B.; Young, J.E.; Bryant, M.; et al. Impact of caloric restriction on health and survival in rhesus monkeys from the NIA study. Nature 2012, 489, 318–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masaldan, S.; Clatworthy, S.A.S.; Gamell, C.; Meggyesy, P.M.; Rigopoulos, A.-T.; Haupt, S.; Haupt, Y.; Denoyer, D.; Adlard, P.A.; Bush, A.I.; et al. Iron accumulation in senescent cells is coupled with impaired ferritinophagy and inhibition of ferroptosis. Redox Biol. 2018, 14, 100–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cozzi, A.; Orellana, D.I.; Santambrogio, P.; Rubio, A.; Cancellieri, C.; Giannelli, S.; Ripamonti, M.; Taverna, S.; Di Lullo, G.; Rovida, E.; et al. Stem Cell Modeling of Neuroferritinopathy Reveals Iron as a Determinant of Senescence and Ferroptosis during Neuronal Aging. Stem Cell Rep. 2019, 13, 832–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuilman, T.; Peeper, D.S. Senescence-messaging secretome: SMS-ing cellular stress. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2009, 9, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salama, R.; Sadaie, M.; Hoare, M.; Narita, M. Cellular senescence and its effector programs. Genes Dev. 2014, 28, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laberge, R.-M.; Sun, Y.; Orjalo, A.V.; Patil, C.K.; Freund, A.; Zhou, L.; Curran, S.C.; Davalos, A.R.; Wilson-Edell, K.A.; Liu, S.; et al. MTOR regulates the pro-tumorigenic senescence-associated secretory phenotype by promoting IL1A translation. Nat. Cell Biol. 2015, 17, 1049–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, C.; Xu, Q.; Martin, T.D.; Li, M.Z.; Demaria, M.; Aron, L.; Lu, T.; Yankner, B.A.; Campisi, J.; Elledge, S.J. The DNA damage response induces inflammation and senescence by inhibiting autophagy of GATA4. Science 2015, 349, aaa5612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, Y.; Hoare, M.; Narita, M. Spatial and Temporal Control of Senescence. Trends Cell Biol. 2017, 27, 820–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freund, A.; Patil, C.K.; Campisi, J. p38MAPK is a novel DNA damage response-independent regulator of the senescence-associated secretory phenotype. Embo J. 2011, 30, 1536–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoare, M.; Ito, Y.; Kang, T.-W.; Weekes, M.P.; Matheson, N.J.; Patten, D.A.; Shetty, S.; Parry, A.J.; Menon, S.; Salama, R.; et al. NOTCH1 mediates a switch between two distinct secretomes during senescence. Nat. Cell Biol. 2016, 18, 979–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aird, K.M.; Iwasaki, O.; Kossenkov, A.V.; Tanizawa, H.; Fatkhutdinov, N.; Bitler, B.G.; Le, L.; Alicea, G.; Yang, T.-L.; Johnson, F.B.; et al. HMGB2 orchestrates the chromatin landscape of senescence-associated secretory phenotype gene loci. J. Cell Biol. 2016, 215, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capell, B.C.; Drake, A.M.; Zhu, J.; Shah, P.P.; Dou, Z.; Dorsey, J.; Simola, D.F.; Donahue, G.; Sammons, M.; Rai, T.S.; et al. MLL1 is essential for the senescence-associated secretory phenotype. Genes Dev. 2016, 30, 321–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Ruiz, P.D.; McKimpson, W.M.; Novikov, L.; Kitsis, R.N.; Gamble, M.J. MacroH2A1 and ATM Play Opposing Roles in Paracrine Senescence and the Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype. Mol. Cell 2015, 59, 719–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contrepois, K.; Coudereau, C.; Benayoun, B.A.; Schuler, N.; Roux, P.-F.; Bischof, O.; Courbeyrette, R.; Carvalho, C.; Thuret, J.-Y.; Ma, Z.; et al. Histone variant H2A.J accumulates in senescent cells and promotes inflammatory gene expression. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 14995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta, J.C.; O’Loghlen, A.; Banito, A.; Guijarro, M.V.; Augert, A.; Raguz, S.; Fumagalli, M.; Da Costa, M.; Brown, C.; Popov, N.; et al. Chemokine signaling via the CXCR2 receptor reinforces senescence. Cell 2008, 133, 1006–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuilman, T.; Michaloglou, C.; Vredeveld, L.C.W.; Douma, S.; van Doorn, R.; Desmet, C.J.; Aarden, L.A.; Mooi, W.J.; Peeper, D.S. Oncogene-induced senescence relayed by an interleukin-dependent inflammatory network. Cell 2008, 133, 1019–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martini, H.; Iacovoni, J.S.; Maggiorani, D.; Dutaur, M.; Marsal, D.J.; Roncalli, J.; Itier, R.; Dambrin, C.; Pizzinat, N.; Mialet-Perez, J.; et al. Aging induces cardiac mesenchymal stromal cell senescence and promotes endothelial cell fate of the CD90 + subset. Aging Cell 2019, 18, e13015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acosta, J.C.; Banito, A.; Wuestefeld, T.; Georgilis, A.; Janich, P.; Morton, J.P.; Athineos, D.; Kang, T.-W.; Lasitschka, F.; Andrulis, M.; et al. A complex secretory program orchestrated by the inflammasome controls paracrine senescence. Nat. Cell Biol. 2013, 15, 978–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krizhanovsky, V.; Yon, M.; Dickins, R.A.; Hearn, S.; Simon, J.; Miething, C.; Yee, H.; Zender, L.; Lowe, S.W. Senescence of activated stellate cells limits liver fibrosis. Cell 2008, 134, 657–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, W.; Zender, L.; Miething, C.; Dickins, R.A.; Hernando, E.; Krizhanovsky, V.; Cordon-Cardo, C.; Lowe, S.W. Senescence and tumour clearance is triggered by p53 restoration in murine liver carcinomas. Nature 2007, 445, 656–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lujambio, A.; Akkari, L.; Simon, J.; Grace, D.; Tschaharganeh, D.F.; Bolden, J.E.; Zhao, Z.; Thapar, V.; Joyce, J.A.; Krizhanovsky, V.; et al. Non-cell-autonomous tumor suppression by p53. Cell 2013, 153, 449–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Meljem, J.M.; Apps, J.R.; Fraser, H.C.; Martinez-Barbera, J.P. Paracrine roles of cellular senescence in promoting tumourigenesis. Br. J. Cancer 2018, 118, 1283–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krtolica, A.; Parrinello, S.; Lockett, S.; Desprez, P.Y.; Campisi, J. Senescent fibroblasts promote epithelial cell growth and tumorigenesis: A link between cancer and aging. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 12072–12077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritschka, B.; Storer, M.; Mas, A.; Heinzmann, F.; Ortells, M.C.; Morton, J.P.; Sansom, O.J.; Zender, L.; Keyes, W.M. The senescence-associated secretory phenotype induces cellular plasticity and tissue regeneration. Genes Dev. 2017, 31, 172–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhinn, M.; Ritschka, B.; Keyes, W.M. Cellular senescence in development, regeneration and disease. Development 2019, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baar, M.P.; Brandt, R.M.C.; Putavet, D.A.; Klein, J.D.D.; Derks, K.W.J.; Bourgeois, B.R.M.; Stryeck, S.; Rijksen, Y.; van Willigenburg, H.; Feijtel, D.A.; et al. Targeted Apoptosis of Senescent Cells Restores Tissue Homeostasis in Response to Chemotoxicity and Aging. Cell 2017, 169, 132–147.e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, J.; Wang, Y.; Shao, L.; Laberge, R.-M.; Demaria, M.; Campisi, J.; Janakiraman, K.; Sharpless, N.E.; Ding, S.; Feng, W.; et al. Clearance of senescent cells by ABT263 rejuvenates aged hematopoietic stem cells in mice. Nat. Med. 2016, 22, 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muñoz-Espín, D.; Rovira, M.; Galiana, I.; Giménez, C.; Lozano-Torres, B.; Paez-Ribes, M.; Llanos, S.; Chaib, S.; Muñoz-Martín, M.; Ucero, A.C.; et al. A versatile drug delivery system targeting senescent cells. Embo Mol. Med. 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schafer, M.J.; White, T.A.; Iijima, K.; Haak, A.J.; Ligresti, G.; Atkinson, E.J.; Oberg, A.L.; Birch, J.; Salmonowicz, H.; Zhu, Y.; et al. Cellular senescence mediates fibrotic pulmonary disease. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 14532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, M.; Pirtskhalava, T.; Farr, J.N.; Weigand, B.M.; Palmer, A.K.; Weivoda, M.M.; Inman, C.L.; Ogrodnik, M.B.; Hachfeld, C.M.; Fraser, D.G.; et al. Senolytics improve physical function and increase lifespan in old age. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 1246–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yosef, R.; Pilpel, N.; Tokarsky-Amiel, R.; Biran, A.; Ovadya, Y.; Cohen, S.; Vadai, E.; Dassa, L.; Shahar, E.; Condiotti, R.; et al. Directed elimination of senescent cells by inhibition of BCL-W and BCL-XL. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 11190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terlecki-Zaniewicz, L.; Lämmermann, I.; Latreille, J.; Bobbili, M.R.; Pils, V.; Schosserer, M.; Weinmüllner, R.; Dellago, H.; Skalicky, S.; Pum, D.; et al. Small extracellular vesicles and their miRNA cargo are anti-apoptotic members of the senescence-associated secretory phenotype. Aging (Albany. Ny). 2018, 10, 1103–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, M.; Ng, N.N.; Concepcion, W.; Thakor, A.S. Emerging role of stem cell-derived extracellular microRNAs in age-associated human diseases and in different therapies of longevity. Ageing Res. Rev. 2020, 57, 100979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghesan, M.; Fafián-Labora, J.; Eleftheriadou, O.; Carpintero-Fernández, P.; Paez-Ribes, M.; Vizcay-Barrena, G.; Swisa, A.; Kolodkin-Gal, D.; Ximénez-Embún, P.; Lowe, R.; et al. Small Extracellular Vesicles Are Key Regulators of Non-cell Autonomous Intercellular Communication in Senescence via the Interferon Protein IFITM3. Cell Rep. 2019, 27, 3956–3971.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadota, T.; Fujita, Y.; Yoshioka, Y.; Araya, J.; Kuwano, K.; Ochiya, T. Emerging role of extracellular vesicles as a senescence-associated secretory phenotype: Insights into the pathophysiology of lung diseases. Mol. Asp. Med. 2018, 60, 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltrami, A.P.; Barlucchi, L.; Torella, D.; Baker, M.; Limana, F.; Chimenti, S.; Kasahara, H.; Rota, M.; Musso, E.; Urbanek, K.; et al. Adult Cardiac Stem Cells Are Multipotent and Support Myocardial Regeneration we have documented the existence of cycling ventricu- lar myocytes in the normal and pathologic adult mam. Cell 2003, 114, 763–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison, G.M.; Vicinanza, C.; Smith, A.J.; Aquila, I.; Leone, A.; Waring, C.D.; Henning, B.J.; Stirparo, G.G.; Papait, R.; Scarfò, M.; et al. Adult c-kitpos Cardiac Stem Cells Are Necessary and Sufficient for Functional Cardiac Regeneration and Repair. Cell 2013, 154, 827–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Messina, E.; De Angelis, L.; Frati, G.; Morrone, S.; Chimenti, S.; Fiordaliso, F.; Salio, M.; Battaglia, M.; Latronico, M.V.G.; Coletta, M.; et al. Isolation and Expansion of Adult Cardiac Stem Cells From Human and Murine Heart. Circ. Res. 2004, 95, 911–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vicinanza, C.; Aquila, I.; Scalise, M.; Cristiano, F.; Marino, F.; Cianflone, E.; Mancuso, T.; Marotta, P.; Sacco, W.; Lewis, F.C.; et al. Adult cardiac stem cells are multipotent and robustly myogenic: C-kit expression is necessary but not sufficient for their identification. Cell Death Differ. 2017, 24, 2101–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aquila, I.; Cianflone, E.; Scalise, M.; Marino, F.; Mancuso, T.; Filardo, A.; Smith, A.J.; Cappetta, D.; De Angelis, A.; Urbanek, K.; et al. c-kit Haploinsufficiency impairs adult cardiac stem cell growth, myogenicity and myocardial regeneration. Cell Death Dis. 2019, 10, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Siena, S.; Gimmelli, R.; Nori, S.L.; Barbagallo, F.; Campolo, F.; Dolci, S.; Rossi, P.; Venneri, M.A.; Giannetta, E.; Gianfrilli, D.; et al. Activated c-Kit receptor in the heart promotes cardiac repair and regeneration after injury. Cell Death Dis. 2016, 7, e2317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Scalise, M.; Torella, M.; Marino, F.; Ravo, M.; Giurato, G.; Vicinanza, C.; Cianflone, E.; Mancuso, T.; Aquila, I.; Salerno, L.; et al. Atrial myxomas arise from multipotent cardiac stem cells. Eur. Heart J. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicinanza, C.; Aquila, I.; Cianflone, E.; Scalise, M.; Marino, F.; Mancuso, T.; Fumagalli, F.; Giovannone, E.D.; Cristiano, F.; Iaccino, E.; et al. Kitcre knock-in mice fail to fate-map cardiac stem cells. Nature 2018, 555, E1–E5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadal-Ginard, B.; Ellison, G.M.; Torella, D. Absence of Evidence Is Not Evidence of Absence: Pitfalls of Cre Knock-Ins in the c-Kit Locus. Circ. Res. 2014, 115, 415–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquila, I.; Marino, F.; Cianflone, E.; Marotta, P.; Torella, M.; Mollace, V.; Indolfi, C.; Torella, D. The use and abuse of Cre/Lox recombination to identify adult cardiomyocyte renewal rate and origin. Pharmacol. Res. 2018, 127, 116–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, F.; Scalise, M.; Cianflone, E.; Mancuso, T.; Aquila, I.; Agosti, V.; Torella, M.; Paolino, D.; Mollace, V.; Nadal-Ginard, B.; et al. Role of c-Kit in Myocardial Regeneration and Aging. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 2019, 10, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Berlo, J.H.; Molkentin, J.D. An emerging consensus on cardiac regeneration. Nat. Med. 2014, 20, 1386–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Berlo, J.H.; Molkentin, J.D. Most of the Dust Has Settled. Circ. Res. 2016, 118, 17–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scalise, M.; Marino, F.; Cianflone, E.; Mancuso, T.; Marotta, P.; Aquila, I.; Torella, M.; Nadal-Ginard, B.; Torella, D. Heterogeneity of Adult Cardiac Stem Cells. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2019, 1169, 141–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.; Appleby, N.; Fuentes, T.; Longo, L.D.; Bailey, L.L.; Hasaniya, N.; Kearns-Jonker, M. Isolation, Characterization, and Spatial Distribution of Cardiac Progenitor Cells in the Sheep Heart. J. Clin. Exp. Cardiolog. 2012, S6. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A.J.; Lewis, F.C.; Aquila, I.; Waring, C.D.; Nocera, A.; Agosti, V.; Nadal-Ginard, B.; Torella, D.; Ellison, G.M. Isolation and characterization of resident endogenous c-Kit+ cardiac stem cells from the adult mouse and rat heart. Nat. Protoc. 2014, 9, 1662–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chimenti, I.; Gaetani, R.; Barile, L.; Forte, E.; Ionta, V.; Angelini, F.; Frati, G.; Messina, E.; Giacomello, A. Isolation and Expansion of Adult Cardiac Stem/Progenitor Cells in the Form of Cardiospheres from Human Cardiac Biopsies and Murine Hearts; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2012; pp. 327–338. [Google Scholar]

- Bollini, S.; Vieira, J.M.N.; Howard, S.; Dubè, K.N.; Balmer, G.M.; Smart, N.; Riley, P.R. Re-Activated Adult Epicardial Progenitor Cells Are a Heterogeneous Population Molecularly Distinct from Their Embryonic Counterparts. Stem Cells Dev. 2014, 23, 1719–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smart, N.; Bollini, S.; Dubé, K.N.; Vieira, J.M.; Zhou, B.; Davidson, S.; Yellon, D.; Riegler, J.; Price, A.N.; Lythgoe, M.F.; et al. De novo cardiomyocytes from within the activated adult heart after injury. Nature 2011, 474, 640–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, C.M.; Meeson, A.P.; Robertson, S.M.; Hawke, T.J.; Richardson, J.A.; Bates, S.; Goetsch, S.C.; Gallardo, T.D.; Garry, D.J. Persistent expression of the ATP-binding cassette transporter, Abcg2, identifies cardiac SP cells in the developing and adult heart. Dev. Biol. 2004, 265, 262–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfister, O.; Mouquet, F.; Jain, M.; Summer, R.; Helmes, M.; Fine, A.; Colucci, W.S.; Liao, R. CD31- but Not CD31+ cardiac side population cells exhibit functional cardiomyogenic differentiation. Circ. Res. 2005, 97, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandstedt, J.; Jonsson, M.; Kajic, K.; Sandstedt, M.; Lindahl, A.; Dellgren, G.; Jeppsson, A.; Asp, J. Left atrium of the human adult heart contains a population of side population cells. Basic Res. Cardiol. 2012, 107, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, H.; Bradfute, S.B.; Gallardo, T.D.; Nakamura, T.; Gaussin, V.; Mishina, Y.; Pocius, J.; Michael, L.H.; Behringer, R.R.; Garry, D.J.; et al. Cardiac progenitor cells from adult myocardium: Homing, differentiation, and fusion after infarction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 12313–12318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Vliet, P.; Roccio, M.; Smits, A.M.; van Oorschot, A.A.M.; Metz, C.H.G.; van Veen, T.A.B.; Sluijter, J.P.G.; Doevendans, P.A.; Goumans, M.-J. Progenitor cells isolated from the human heart: A potential cell source for regenerative therapy. Neth. Heart J. 2008, 16, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smits, A.M.; van Vliet, P.; Metz, C.H.; Korfage, T.; Sluijter, J.P.G.; Doevendans, P.A.; Goumans, M.J. Human cardiomyocyte progenitor cells differentiate into functional mature cardiomyocytes: An in vitro model for studying human cardiac physiology and pathophysiology. Nat. Protoc. 2009, 4, 232–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laugwitz, K.-L.; Moretti, A.; Lam, J.; Gruber, P.; Chen, Y.; Woodard, S.; Lin, L.-Z.; Cai, C.-L.; Lu, M.M.; Reth, M.; et al. Postnatal isl1+ cardioblasts enter fully differentiated cardiomyocyte lineages. Nature 2005, 433, 647–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bu, L.; Jiang, X.; Martin-Puig, S.; Caron, L.; Zhu, S.; Shao, Y.; Roberts, D.J.; Huang, P.L.; Domian, I.J.; Chien, K.R. Human ISL1 heart progenitors generate diverse multipotent cardiovascular cell lineages. Nature 2009, 460, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noseda, M.; Harada, M.; McSweeney, S.; Leja, T.; Belian, E.; Stuckey, D.J.; Abreu Paiva, M.S.; Habib, J.; Macaulay, I.; de Smith, A.J.; et al. PDGFRα demarcates the cardiogenic clonogenic Sca1+ stem/progenitor cell in adult murine myocardium. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, C.-L.; Liang, X.; Shi, Y.; Chu, P.-H.; Pfaff, S.L.; Chen, J.; Evans, S. Isl1 Identifies a Cardiac Progenitor Population that Proliferates Prior to Differentiation and Contributes a Majority of Cells to the Heart. Dev. Cell 2003, 5, 877–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Berlo, J.H.; Kanisicak, O.; Maillet, M.; Vagnozzi, R.J.; Karch, J.; Lin, S.C.J.; Middleton, R.C.; Marbán, E.; Molkentin, J.D. C-kit+ cells minimally contribute cardiomyocytes to the heart. Nature 2014, 509, 337–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultana, N.; Zhang, L.; Yan, J.; Chen, J.; Cai, W.; Razzaque, S.; Jeong, D.; Sheng, W.; Bu, L.; Xu, M.; et al. Resident c-kit+ cells in the heart are not cardiac stem cells. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 8701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Yang, R.; Huang, X.; Zhang, H.; He, L.; Zhang, L.; Tian, X.; Nie, Y.; Hu, S.; Yan, Y.; et al. Genetic lineage tracing identifies in situ Kit-expressing cardiomyocytes. Cell Res. 2016, 26, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, L.; Han, M.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Y.; Huang, X.; Liu, X.; Pu, W.; Zhao, H.; Wang, Q.-D.; Nie, Y.; et al. Reassessment of c-Kit+ Cells for Cardiomyocyte Contribution in Adult Heart. Circulation 2019, 140, 164–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chien, K.R.; Frisén, J.; Fritsche-Danielson, R.; Melton, D.A.; Murry, C.E.; Weissman, I.L. Regenerating the field of cardiovascular cell therapy. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 232–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, J.A. A Time to Press Reset and Regenerate Cardiac Stem Cell Biology. Jama Cardiol. 2019, 4, 95–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cianflone, E.; Aquila, I.; Scalise, M.; Marotta, P.; Torella, M.; Nadal-Ginard, B.; Torella, D. Molecular basis of functional myogenic specification of Bona Fide multipotent adult cardiac stem cells. Cell Cycle. 2018, 17, 927–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marotta, P.; Cianflone, E.; Aquila, I.; Vicinanza, C.; Scalise, M.; Marino, F.; Mancuso, T.; Torella, M.; Indolfi, C.; Torella, D. Combining cell and gene therapy to advance cardiac regeneration. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2018, 18, 409–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancuso, T.; Barone, A.; Salatino, A.; Molinaro, C.; Marino, F.; Scalise, M.; Torella, M.; De Angelis, A.; Urbanek, K.; Torella, D.; et al. Unravelling the Biology of Adult Cardiac Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes to Foster Endogenous Cardiac Regeneration and Repair. Int J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesselli, D.; Aleksova, A.; Mazzega, E.; Caragnano, A.; Beltrami, A.P. Cardiac stem cell aging and heart failure. Pharmacol. Res. 2018, 127, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avolio, E.; Gianfranceschi, G.; Cesselli, D.; Caragnano, A.; Athanasakis, E.; Katare, R.; Meloni, M.; Palma, A.; Barchiesi, A.; Vascotto, C.; et al. Ex vivo molecular rejuvenation improves the therapeutic activity of senescent human cardiac stem cells in a mouse model of myocardial infarction. Stem Cells 2014, 32, 2373–2385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesselli, D.; Beltrami, A.P.; D’Aurizio, F.; Marcon, P.; Bergamin, N.; Toffoletto, B.; Pandolfi, M.; Puppato, E.; Marino, L.; Signore, S.; et al. Effects of age and heart failure on human cardiac stem cell function. Am. J. Pathol. 2011, 179, 349–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianfranceschi, G.; Caragnano, A.; Piazza, S.; Manini, I.; Ciani, Y.; Verardo, R.; Toffoletto, B.; Finato, N.; Livi, U.; Beltrami, C.A.; et al. Critical role of lysosomes in the dysfunction of human Cardiac Stem Cells obtained from failing hearts. Int. J. Cardiol. 2016, 216, 140–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, D.J.; Childs, B.G.; Durik, M.; Wijers, M.E.; Sieben, C.J.; Zhong, J.; Saltness, R.A.; Jeganathan, K.B.; Verzosa, G.C.; Pezeshki, A.; et al. Naturally occurring p16(Ink4a)-positive cells shorten healthy lifespan. Nature 2016, 530, 184–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chimenti, C.; Kajstura, J.; Torella, D.; Urbanek, K.; Heleniak, H.; Colussi, C.; Di Meglio, F.; Nadal-Ginard, B.; Frustaci, A.; Leri, A.; et al. Senescence and death of primitive cells and myocytes lead to premature cardiac aging and heart failure. Circ. Res. 2003, 93, 604–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbanek, K.; Torella, D.; Sheikh, F.; De Angelis, A.; Nurzynska, D.; Silvestri, F.; Beltrami, C.A.; Bussani, R.; Beltrami, A.P.; Quaini, F.; et al. Myocardial regeneration by activation of multipotent cardiac stem cells in ischemic heart failure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 8692–8697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hariharan, N.; Quijada, P.; Mohsin, S.; Joyo, A.; Samse, K.; Monsanto, M.; De La Torre, A.; Avitabile, D.; Ormachea, L.; McGregor, M.J.; et al. Nucleostemin Rejuvenates Cardiac Progenitor Cells and Antagonizes Myocardial Aging. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2015, 65, 133–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, D.J.; Wijshake, T.; Tchkonia, T.; LeBrasseur, N.K.; Childs, B.G.; van de Sluis, B.; Kirkland, J.L.; van Deursen, J.M. Clearance of p16Ink4a-positive senescent cells delays ageing-associated disorders. Nature 2011, 479, 232–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farr, J.N.; Xu, M.; Weivoda, M.M.; Monroe, D.G.; Fraser, D.G.; Onken, J.L.; Negley, B.A.; Sfeir, J.G.; Ogrodnik, M.B.; Hachfeld, C.M.; et al. Targeting cellular senescence prevents age-related bone loss in mice. Nat. Med. 2017, 23, 1072–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, M.; Korfei, M.; Mutze, K.; Klee, S.; Skronska-Wasek, W.; Alsafadi, H.N.; Ota, C.; Costa, R.; Schiller, H.B.; Lindner, M.; et al. Senolytic drugs target alveolar epithelial cell function and attenuate experimental lung fibrosis ex vivo. Eur. Respir. J. 2017, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogrodnik, M.; Miwa, S.; Tchkonia, T.; Tiniakos, D.; Wilson, C.L.; Lahat, A.; Day, C.P.; Burt, A.; Palmer, A.; Anstee, Q.M.; et al. Cellular senescence drives age-dependent hepatic steatosis. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 15691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roos, C.M.; Zhang, B.; Palmer, A.K.; Ogrodnik, M.B.; Pirtskhalava, T.; Thalji, N.M.; Hagler, M.; Jurk, D.; Smith, L.A.; Casaclang-Verzosa, G.; et al. Chronic senolytic treatment alleviates established vasomotor dysfunction in aged or atherosclerotic mice. Aging Cell 2016, 15, 973–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Palmer, A.K.; Ding, H.; Weivoda, M.M.; Pirtskhalava, T.; White, T.A.; Sepe, A.; Johnson, K.O.; Stout, M.B.; Giorgadze, N.; et al. Targeting senescent cells enhances adipogenesis and metabolic function in old age. Elife 2015, 4, e12997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, M.; Tchkonia, T.; Ding, H.; Ogrodnik, M.; Lubbers, E.R.; Pirtskhalava, T.; White, T.A.; Johnson, K.O.; Stout, M.B.; Mezera, V.; et al. JAK inhibition alleviates the cellular senescence-associated secretory phenotype and frailty in old age. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, E6301–E6310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Tchkonia, T.; Pirtskhalava, T.; Gower, A.C.; Ding, H.; Giorgadze, N.; Palmer, A.K.; Ikeno, Y.; Hubbard, G.B.; Lenburg, M.; et al. The Achilles’ heel of senescent cells: From transcriptome to senolytic drugs. Aging Cell 2015, 14, 644–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tchkonia, T.; Kirkland, J.L. Aging, Cell Senescence, and Chronic Disease: Emerging Therapeutic Strategies. JAMA 2018, 320, 1319–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivieri, F.; Prattichizzo, F.; Grillari, J.; Balistreri, C.R. Cellular Senescence and Inflammaging in Age-Related Diseases. Mediat. Inflamm. 2018, 2018, 9076485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prata, L.G.P.L.; Ovsyannikova, I.G.; Tchkonia, T.; Kirkland, J.L. Senescent cell clearance by the immune system: Emerging therapeutic opportunities. Semin. Immunol. 2018, 40, 101275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, J.J.H.; Chandrakanthan, V.; Xaymardan, M.; Asli, N.S.; Li, J.; Ahmed, I.; Heffernan, C.; Menon, M.K.; Scarlett, C.J.; Rashidianfar, A.; et al. Adult Cardiac-Resident MSC-like Stem Cells with a Proepicardial Origin. Cell Stem Cell 2011, 9, 527–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farbehi, N.; Patrick, R.; Dorison, A.; Xaymardan, M.; Janbandhu, V.; Wystub-Lis, K.; Ho, J.W.; Nordon, R.E.; Harvey, R.P. Single-cell expression profiling reveals dynamic flux of cardiac stromal, vascular and immune cells in health and injury. Elife 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliman, H.; Paylor, B.; Scott, R.W.; Lemos, D.R.; Chang, C.; Arostegui, M.; Low, M.; Lee, C.; Fiore, D.; Braghetta, P.; et al. Pathogenic Potential of Hic1-Expressing Cardiac Stromal Progenitors. Cell Stem Cell 2020, 26, 205–220.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, R.; Breda, E.; Oberg, A.L.; Powell, C.C.; Dalla Man, C.; Basu, A.; Vittone, J.L.; Klee, G.G.; Arora, P.; Jensen, M.D.; et al. Mechanisms of the age-associated deterioration in glucose tolerance: Contribution of alterations in insulin secretion, action, and clearance. Diabetes 2003, 52, 1738–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, A.M.; Halter, J.B. Aging and insulin secretion. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2003, 284, E7–E12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalyani, R.R.; Corriere, M.; Ferrucci, L. Age-related and disease-related muscle loss: The effect of diabetes, obesity, and other diseases. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014, 2, 819–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torella, D.; Ellison, G.M.; Torella, M.; Vicinanza, C.; Aquila, I.; Iaconetti, C.; Scalise, M.; Marino, F.; Henning, B.J.; Lewis, F.C.; et al. Carbonic anhydrase activation is associated with worsened pathological remodeling in human ischemic diabetic cardiomyopathy. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2014, 3, e000434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torella, D.; Iaconetti, C.; Tarallo, R.; Marino, F.; Giurato, G.; Veneziano, C.; Aquila, I.; Scalise, M.; Mancuso, T.; Cianflone, E.; et al. miRNA Regulation of the Hyperproliferative Phenotype of Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells in Diabetes. Diabetes 2018, 67, 2554–2568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satthenapalli, V.R.; Lamberts, R.R.; Katare, R.G. Concise Review: Challenges in Regenerating the Diabetic Heart: A Comprehensive Review. Stem Cells 2017, 35, 2009–2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecellio, M.; Spallotta, F.; Nanni, S.; Colussi, C.; Cencioni, C.; Derlet, A.; Bassetti, B.; Tilenni, M.; Carena, M.C.; Farsetti, A.; et al. The histone acetylase activator pentadecylidenemalonate 1b rescues proliferation and differentiation in the human cardiac mesenchymal cells of type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes 2014, 63, 2132–2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M.-H.; Cheng, M.; Koh, T.J. Impaired muscle regeneration in ob/ob and db/db mice. Sci. World J. 2011, 11, 1525–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rota, M.; LeCapitaine, N.; Hosoda, T.; Boni, A.; De Angelis, A.; Padin-Iruegas, M.E.; Esposito, G.; Vitale, S.; Urbanek, K.; Casarsa, C.; et al. Diabetes promotes cardiac stem cell aging and heart failure, which are prevented by deletion of the p66shc gene. Circ. Res. 2006, 99, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- She, T.; Wang, X.; Gan, Y.; Kuang, D.; Yue, J.; Ni, J.; Zhao, X.; Wang, G. Hyperglycemia suppresses cardiac stem cell homing to peri-infarcted myocardium via regulation of ERK1/2 and p38 MAPK activities. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2012, 30, 1313–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fomison-Nurse, I.; Saw, E.E.L.; Gandhi, S.; Munasinghe, P.E.; Van Hout, I.; Williams, M.J.A.; Galvin, I.; Bunton, R.; Davis, P.; Cameron, V.; et al. Diabetes induces the activation of pro-ageing miR-34a in the heart, but has differential effects on cardiomyocytes and cardiac progenitor cells. Cell Death Differ. 2018, 25, 1336–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Meng, K.; Pu, Y.; Wang, C.; Chen, Y.; Wang, L. Hyperglycemia Altered the Fate of Cardiac Stem Cells to Adipogenesis through Inhibiting the β-Catenin/TCF-4 Pathway. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 49, 2254–2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmer, A.K.; Tchkonia, T.; LeBrasseur, N.K.; Chini, E.N.; Xu, M.; Kirkland, J.L. Cellular Senescence in Type 2 Diabetes: A Therapeutic Opportunity. Diabetes 2015, 64, 2289–2298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cappetta, D.; De Angelis, A.; Sapio, L.; Prezioso, L.; Illiano, M.; Quaini, F.; Rossi, F.; Berrino, L.; Naviglio, S.; Urbanek, K. Oxidative Stress and Cellular Response to Doxorubicin: A Common Factor in the Complex Milieu of Anthracycline Cardiotoxicity. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2017, 2017, 1521020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farías, J.G.; Molina, V.M.; Carrasco, R.A.; Zepeda, A.B.; Figueroa, E.; Letelier, P.; Castillo, R.L. Antioxidant Therapeutic Strategies for Cardiovascular Conditions Associated with Oxidative Stress. Nutrients 2017, 9, 966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ewer, M.S.; Ewer, S.M. Troponin I provides insight into cardiotoxicity and the anthracycline-trastuzumab interaction. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 28, 3901–3904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deidda, M.; Madonna, R.; Mango, R.; Pagliaro, P.; Bassareo, P.P.; Cugusi, L.; Romano, S.; Penco, M.; Romeo, F.; Mercuro, G. Novel insights in pathophysiology of antiblastic drugs-induced cardiotoxicity and cardioprotection. J. Cardiovasc. Med. 2016, 17, S76–S83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Angelis, A.; Piegari, E.; Cappetta, D.; Marino, L.; Filippelli, A.; Berrino, L.; Ferreira-Martins, J.; Zheng, H.; Hosoda, T.; Rota, M.; et al. Anthracycline cardiomyopathy is mediated by depletion of the cardiac stem cell pool and is rescued by restoration of progenitor cell function. Circulation 2010, 121, 276–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piegari, E.; De Angelis, A.; Cappetta, D.; Russo, R.; Esposito, G.; Costantino, S.; Graiani, G.; Frati, C.; Prezioso, L.; Berrino, L.; et al. Doxorubicin induces senescence and impairs function of human cardiac progenitor cells. Basic Res. Cardiol. 2013, 108, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Angelis, A.; Piegari, E.; Cappetta, D.; Russo, R.; Esposito, G.; Ciuffreda, L.P.; Ferraiolo, F.A.V.; Frati, C.; Fagnoni, F.; Berrino, L.; et al. SIRT1 activation rescues doxorubicin-induced loss of functional competence of human cardiac progenitor cells. Int. J. Cardiol. 2015, 189, 30–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piegari, E.; Russo, R.; Cappetta, D.; Esposito, G.; Urbanek, K.; Dell’Aversana, C.; Altucci, L.; Berrino, L.; Rossi, F.; De Angelis, A. MicroRNA-34a regulates doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity in rat. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 62312–62326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazzarini, E.; Balbi, C.; Altieri, P.; Pfeffer, U.; Gambini, E.; Canepa, M.; Varesio, L.; Bosco, M.C.; Coviello, D.; Pompilio, G.; et al. The human amniotic fluid stem cell secretome effectively counteracts doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 29994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.; Zhang, X.; Ramil, J.M.; Rikka, S.; Kim, L.; Lee, Y.; Gude, N.A.; Thistlethwaite, P.A.; Sussman, M.A.; Gottlieb, R.A.; et al. Juvenile exposure to anthracyclines impairs cardiac progenitor cell function and vascularization resulting in greater susceptibility to stress-induced myocardial injury in adult mice. Circulation 2010, 121, 675–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carresi, C.; Musolino, V.; Gliozzi, M.; Maiuolo, J.; Mollace, R.; Nucera, S.; Maretta, A.; Sergi, D.; Muscoli, S.; Gratteri, S.; et al. Anti-oxidant effect of bergamot polyphenolic fraction counteracts doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy: Role of autophagy and c-kitposCD45negCD31neg cardiac stem cell activation. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2018, 119, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milano, G.; Biemmi, V.; Lazzarini, E.; Balbi, C.; Ciullo, A.; Bolis, S.; Ameri, P.; Di Silvestre, D.; Mauri, P.; Barile, L.; et al. Intravenous administration of cardiac progenitor cell-derived exosomes protects against doxorubicin/trastuzumab-induced cardiac toxicity. Cardiovasc. Res. 2020, 116, 383–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beauséjour, C.M.; Krtolica, A.; Galimi, F.; Narita, M.; Lowe, S.W.; Yaswen, P.; Campisi, J. Reversal of human cellular senescence: Roles of the p53 and p16 pathways. Embo J. 2003, 22, 4212–4222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sage, J.; Miller, A.L.; Pérez-Mancera, P.A.; Wysocki, J.M.; Jacks, T. Acute mutation of retinoblastoma gene function is sufficient for cell cycle re-entry. Nature 2003, 424, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milanovic, M.; Fan, D.N.Y.; Belenki, D.; Däbritz, J.H.M.; Zhao, Z.; Yu, Y.; Dörr, J.R.; Dimitrova, L.; Lenze, D.; Monteiro Barbosa, I.A.; et al. Senescence-associated reprogramming promotes cancer stemness. Nature 2018, 553, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Schleich, K.; Yue, B.; Ji, S.; Lohneis, P.; Kemper, K.; Silvis, M.R.; Qutob, N.; van Rooijen, E.; Werner-Klein, M.; et al. Targeting the Senescence-Overriding Cooperative Activity of Structurally Unrelated H3K9 Demethylases in Melanoma. Cancer Cell 2018, 33, 322–336.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voorhoeve, P.M.; Agami, R. The tumor-suppressive functions of the human INK4A locus. Cancer Cell 2003, 4, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chicas, A.; Wang, X.; Zhang, C.; McCurrach, M.; Zhao, Z.; Mert, O.; Dickins, R.A.; Narita, M.; Zhang, M.; Lowe, S.W. Dissecting the unique role of the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor during cellular senescence. Cancer Cell 2010, 17, 376–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debacq-Chainiaux, F.; Erusalimsky, J.D.; Campisi, J.; Toussaint, O. Protocols to detect senescence-associated beta-galactosidase (SA-betagal) activity, a biomarker of senescent cells in culture and in vivo. Nat. Protoc. 2009, 4, 1798–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herranz, N.; Gil, J. Mechanisms and functions of cellular senescence. J. Clin. Invest. 2018, 128, 1238–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocampo, A.; Reddy, P.; Martinez-Redondo, P.; Platero-Luengo, A.; Hatanaka, F.; Hishida, T.; Li, M.; Lam, D.; Kurita, M.; Beyret, E.; et al. In Vivo Amelioration of Age-Associated Hallmarks by Partial Reprogramming. Cell 2016, 167, 1719–1733.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkar, T.J.; Quarta, M.; Mukherjee, S.; Colville, A.; Paine, P.; Doan, L.; Tran, C.M.; Chu, C.R.; Horvath, S.; Qi, L.S.; et al. Transient non-integrative expression of nuclear reprogramming factors promotes multifaceted amelioration of aging in human cells. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Wang, L.; Vaseghi, H.R.; Liu, Z.; Lu, R.; Alimohamadi, S.; Yin, C.; Fu, J.-D.; Wang, G.G.; Liu, J.; et al. Bmi1 Is a Key Epigenetic Barrier to Direct Cardiac Reprogramming. Cell Stem Cell 2016, 18, 382–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Meana, M.; Bou-Teen, D.; Ferdinandy, P.; Gyongyosi, M.; Pesce, M.; Perrino, C.; Schulz, R.; Sluijter, J.; Tocchetti, C.G.; Thum, T.; et al. Cardiomyocyte ageing and cardioprotection: Consensus Document from the ESC Working Groups Cell Biology of the Heart and Myocardial Function. Cardiovasc. Res. 2020, 8, cvaa132, online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cianflone, E.; Torella, M.; Biamonte, F.; De Angelis, A.; Urbanek, K.; Costanzo, F.S.; Rota, M.; Ellison-Hughes, G.M.; Torella, D. Targeting Cardiac Stem Cell Senescence to Treat Cardiac Aging and Disease. Cells 2020, 9, 1558. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells9061558

Cianflone E, Torella M, Biamonte F, De Angelis A, Urbanek K, Costanzo FS, Rota M, Ellison-Hughes GM, Torella D. Targeting Cardiac Stem Cell Senescence to Treat Cardiac Aging and Disease. Cells. 2020; 9(6):1558. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells9061558

Chicago/Turabian StyleCianflone, Eleonora, Michele Torella, Flavia Biamonte, Antonella De Angelis, Konrad Urbanek, Francesco S. Costanzo, Marcello Rota, Georgina M. Ellison-Hughes, and Daniele Torella. 2020. "Targeting Cardiac Stem Cell Senescence to Treat Cardiac Aging and Disease" Cells 9, no. 6: 1558. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells9061558

APA StyleCianflone, E., Torella, M., Biamonte, F., De Angelis, A., Urbanek, K., Costanzo, F. S., Rota, M., Ellison-Hughes, G. M., & Torella, D. (2020). Targeting Cardiac Stem Cell Senescence to Treat Cardiac Aging and Disease. Cells, 9(6), 1558. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells9061558