A Comprehensive Overview of Neurophysiological Correlates of Cognitive Impairment in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis

Abstract

1. Search Method

2. Clinical Features of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS)

3. Genetics

4. Cognitive Deficits in ALS

5. Brain Structural Correlates of Cognitive Decline in ALS

6. Functional Neuroimaging Correlates of Cognitive Impairment in ALS

| AUTHORS | NEUROIMAGING MODALITY | #ALS/CONTROL | METHOD/TASK | MAJOR FINDINGS IN NON-MOTOR REGIONS IN ALS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| REST | Ma et al., 2015 [49] | fMRI | 20/20 | Functional network analysis | Within the hub regions, higher functional connectivity in the prefrontal cortex with the connectivity strength in the abnormal hub associated with clinical variables, was obtained |

| Luo et al., 2012 [62] | fMRI | 20/20 | Functional connectivity | Alteration in low-frequency fluctuations in frontal areas was concluded | |

| Douaud et al., 2011 [63] | fMRI + DWI | 25/15 | Functional/structural connectivity | Increased functional connectivity spanning sensorimotor, premotor, prefrontal and thalamic regions associated with decreased structural connectivity, was obtained | |

| Agosta et al., 2013 [65] | fMRI | 20/15 | Functional network analysis | A divergent connectivity pattern in the default mode network (DMN), including decreased connectivity of the right orbitofrontal cortex and increased parietal connectivity, was associated with clinical and cognitive deficits | |

| Li et al., 2017 [67] | fMRI | 21/21 | Functional connectivity | Decreased functional connectivity in the left and right ventrolateral PFC, along with widespread and frequency-dependent FCS changes, provided evidence that ALS patients exhibit consistent impairments in extra-motor regions even at relatively early stages of the disease | |

| Fraschini et al., 2016 [69] | EEG | 21/16 | Functional network analysis | A significant group difference in MST dissimilarity and MST leaf fraction in the beta-band was found | |

| Kopitzki et al., 2016 [70] | fNIRS + DTI | 31/30 | Functional (hemodynamic) /structural connectivity | Anterior-temporal homotopic rs-FC was found to correlate with fractional anisotropy in the central corpus callosum (CC) | |

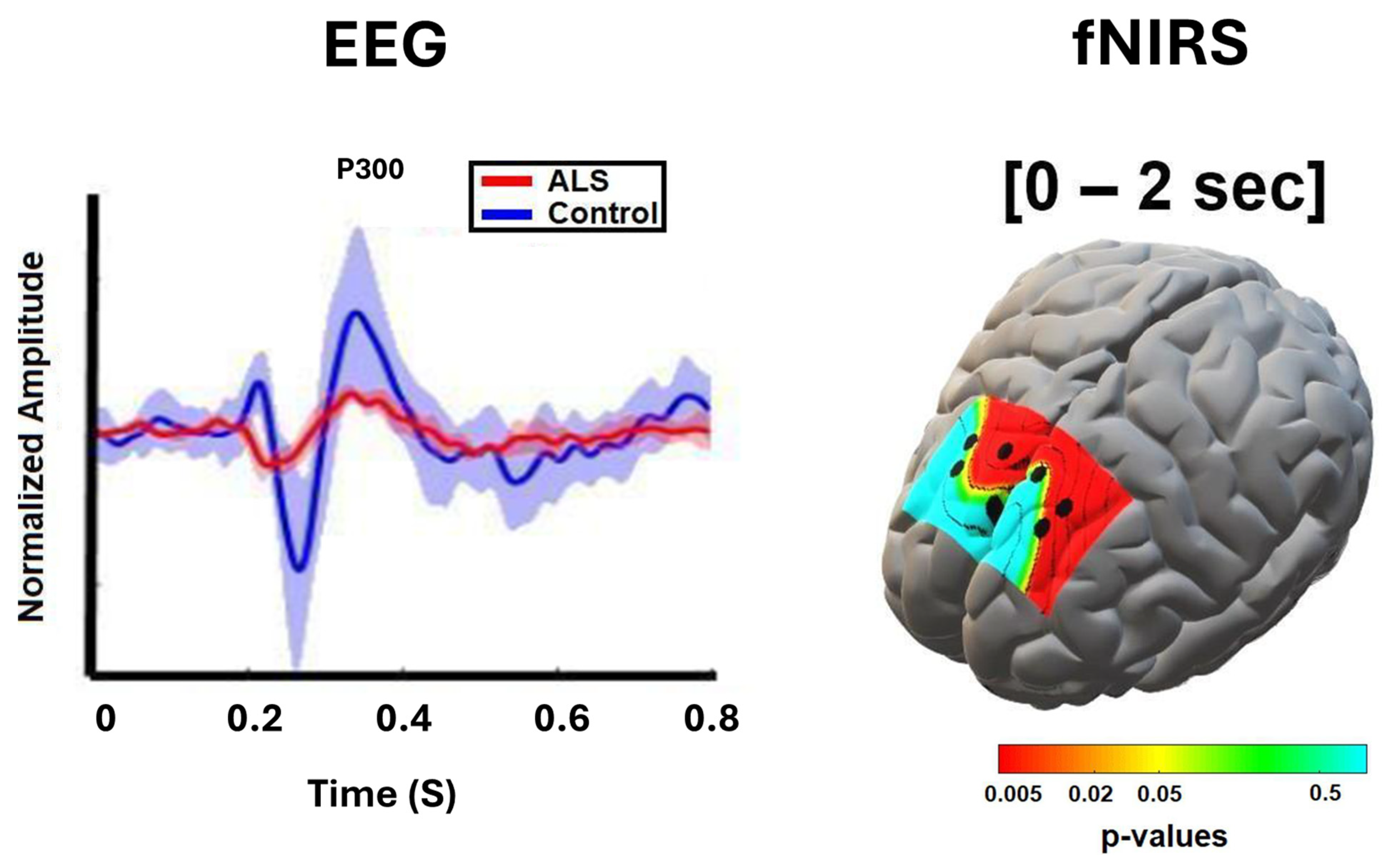

| Deligani et al., 2020 [59] | fNRIS + EEG | 10/9 | Functional connectivity | Increased fronto-parietal EEG connectivity in the alpha and beta bands, along with increased interhemispheric and right intra-hemispheric fNIRS connectivity in the frontal and prefrontal regions, was observed | |

| Nasseroleslam et al., 2019 [71] | EEG + MRI | 100/34 | Functional/structural connectivity | Increased EEG coherence between parietal–frontal scalp regions in the gamma band was observed. EEG signals associated with less extensively involved non-motor regions also showed enhanced structural connectivity on MRI | |

| Dukic et al., 2019 [72] | EEG+ MRI | 74/47 | Functional connectivity | Increased co-modulation in frontal regions (theta and gamma bands), along with decreased synchrony in the temporal and frontal regions (theta to beta bands), was observed | |

| TASK-BASED | Riccio et al., 2013 [84] | EEG | 8/NA | P300-BCI spelling | The temporal filtering capacity in the RSVP task was a predictor of both the P300-based BCI accuracy |

| Pinkhardt et al., 2008 [85] | EEG | 20/20 | ERP/dichotic listening task | A distinct decrease in the fronto-precentral negative difference signal (Nd) was observed in ALS, along with increased processing of non-relevant stimuli, as reflected by the P3 component, suggesting a reduced focus of attention | |

| Shahriari et al., 2019 [86] | EEG | 9/NA | P300-BCI spelling | BCI performance was positively correlated with a positive deflection in EEG amplitude around 220 ms at frontal mid-line locations | |

| Zisk et al., 2021 [90] | EEG | 6/9 | P300-BCI spelling | Latency jitter was significantly increased in participants with ALS | |

| Kasahara et al., 2012 [112] | EEG | 8/11 | ERD/motor imagery task | The ERD of ALS patients was significantly smaller | |

| Hosni et al., 2019 [113] | EEG | 6/11 | ERD/motor imagery task | Decreased ERD features were correlated with ALS clinical scores, specifically disease duration, bulbar, and cognitive functions | |

| Stanton et al., 2007 [115] | fMRI | 16/17 | Motor imagery task | Reduced activation during motor imagery was observed in ALS in the left inferior parietal region, as well as in the anterior cingulate gyrus and medial prefrontal cortex | |

| Borgheai et al., 2020 [127] | fNIRS | 9/10 | Functional network analysis /visuo-mental task | A more centralized frontal network organization was observed in the ALS group, with the most frequent network hubs showing an asymmetrical pattern predominantly localized in the right prefrontal cortex | |

| Shahriari et al., 2015 [136] | EEG | 9/13 | P300/BCI spelling | A significantly broader distribution of high-beta band connectivity, along with an absence of distinct connections in the directivity analysis, was observed in ALS patients | |

| Hammer et al., 2010 [138] | EEG | 17/20 | ERP/Go-NoGo task | An anteriorization of the NoGo-P3 was observed, a pattern that has been established as an index of impaired inhibitory function | |

| Proudfoot et al., 2017 [151] | MEG | 11/10 | Spectral power/motor task | A relative increase in beta-power was revealed in the frontal lobe and premotor regions |

7. Correspondence Between Structural and Functional Neuroimaging and Other Cognitive Biomarkers of ALS

8. Summary and Perspectives

9. Limitations, Gaps, and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Grad, L.I.; Rouleau, G.A.; Ravits, J.; Cashman, N.R. Clinical Spectrum of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS). Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2017, 7, a024117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, R.H.; Al-Chalabi, A. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 162–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agosta, F.; Chio, A.; Cosottini, M.; De Stefano, N.; Falini, A.; Mascalchi, M.; Rocca, M.A.; Silani, V.; Tedeschi, G.; Filippi, M. The present and the future of neuroimaging in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2010, 31, 1769–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardiman, O.; Al-Chalabi, A.; Chio, A.; Corr, E.M.; Logroscino, G.; Robberecht, W.; Shaw, P.J.; Simmons, Z.; van den Berg, L.H. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2017, 3, 17071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Es, M.A.; Hardiman, O.; Chio, A.; Al-Chalabi, A.; Pasterkamp, R.J.; Veldink, J.H.; van den Berg, L.H. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Lancet 2017, 390, 2084–2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Cooper-Knock, J.; Weimer, A.K.; Shi, M.; Moll, T.; Marshall, J.N.G.; Harvey, C.; Nezhad, H.G.; Franklin, J.; Souza, C.D.S.; et al. Genome-wide identification of the genetic basis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neuron 2022, 110, 992–1008.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renton, A.E.; Majounie, E.; Waite, A.; Simon-Sanchez, J.; Rollinson, S.; Gibbs, J.R.; Schymick, J.C.; Laaksovirta, H.; van Swieten, J.C.; Myllykangas, L.; et al. A hexanucleotide repeat expansion in C9ORF72 is the cause of chromosome 9p21-linked ALS-FTD. Neuron 2011, 72, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, Z.Y.; Zhou, Z.R.; Che, C.H.; Liu, C.Y.; He, R.L.; Huang, H.P. Genetic epidemiology of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2017, 88, 540–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.F.; Wu, Z.Y. Genotype-phenotype correlations of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Transl. Neurodegener. 2016, 5, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breevoort, S.; Gibson, S.; Figueroa, K.; Bromberg, M.; Pulst, S. Expanding Clinical Spectrum of C9ORF72-Related Disorders and Promising Therapeutic Strategies: A Review. Neurol. Genet. 2022, 8, e670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, N.; Nishiyama, A.; Warita, H.; Aoki, M. Genetics of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: Seeking therapeutic targets in the era of gene therapy. J. Hum. Genet. 2023, 68, 131–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akcimen, F.; Lopez, E.R.; Landers, J.E.; Nath, A.; Chio, A.; Chia, R.; Traynor, B.J. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: Translating genetic discoveries into therapies. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2023, 24, 642–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, S.J.; McKeown, S.R.; Rashid, S. Mutant SOD1 mediated pathogenesis of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Gene 2016, 577, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peggion, C.; Scalcon, V.; Massimino, M.L.; Nies, K.; Lopreiato, R.; Rigobello, M.P.; Bertoli, A. SOD1 in ALS: Taking stock in pathogenic mechanisms and the role of glial and muscle cells. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, G.; Gautier, O.; Tassoni-Tsuchida, E.; Ma, X.R.; Gitler, A.D. ALS Genetics: Gains, Losses, and Implications for Future Therapies. Neuron 2020, 108, 822–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCauley, M.E.; Baloh, R.H. Inflammation in ALS/FTD pathogenesis. Acta Neuropathol. 2019, 137, 715–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smeyers, J.; Banchi, E.G.; Latouche, M. C9ORF72: What It Is, What It Does, and Why It Matters. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 661447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi, M.; Brown, R.H., Jr. Genetics of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2018, 8, a024125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sephton, C.F.; Cenik, B.; Cenik, B.K.; Herz, J.; Yu, G. TDP-43 in central nervous system development and function: Clues to TDP-43-associated neurodegeneration. Biol. Chem. 2012, 393, 589–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, M.; Sampathu, D.M.; Kwong, L.K.; Truax, A.C.; Micsenyi, M.C.; Chou, T.T.; Bruce, J.; Schuck, T.; Grossman, M.; Clark, C.M.; et al. Ubiquitinated TDP-43 in frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Science 2006, 314, 130–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Arai, S.; Song, X.; Reichart, D.; Du, K.; Pascual, G.; Tempst, P.; Rosenfeld, M.G.; Glass, C.K.; Kurokawa, R. Induced ncRNAs allosterically modify RNA-binding proteins in cis to inhibit transcription. Nature 2008, 454, 126–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, J.; Yang, M.; Chen, Y.; Chen, X.; Liu, J.; Sun, S.; Cheng, H.; Li, Y.; Bigio, E.H.; Mesulam, M.; et al. FUS Interacts with HSP60 to Promote Mitochondrial Damage. PLoS Genet. 2015, 11, e1005357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elamin, M.; Bede, P.; Montuschi, A.; Pender, N.; Chio, A.; Hardiman, O. Predicting prognosis in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A simple algorithm. J. Neurol. 2015, 262, 1447–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mioshi, E.; Lillo, P.; Yew, B.; Hsieh, S.; Savage, S.; Hodges, J.R.; Kiernan, M.C.; Hornberger, M. Cortical atrophy in ALS is critically associated with neuropsychiatric and cognitive changes. Neurology 2013, 80, 1117–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poletti, B.; Solca, F.; Carelli, L.; Faini, A.; Madotto, F.; Lafronza, A.; Monti, A.; Zago, S.; Ciammola, A.; Ratti, A.; et al. Cognitive-behavioral longitudinal assessment in ALS: The Italian Edinburgh Cognitive and Behavioral ALS screen (ECAS). Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Front. Degener. 2018, 19, 387–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahams, S.; Newton, J.; Niven, E.; Foley, J.; Bak, T.H. Screening for cognition and behaviour changes in ALS. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Front. Degener. 2014, 15, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poletti, B.; Solca, F.; Carelli, L.; Madotto, F.; Lafronza, A.; Faini, A.; Monti, A.; Zago, S.; Calini, D.; Tiloca, C.; et al. The validation of the Italian Edinburgh Cognitive and Behavioural ALS Screen (ECAS). Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Front. Degener. 2016, 17, 489–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strong, M.J.; Abrahams, S.; Goldstein, L.H.; Woolley, S.; McLaughlin, P.; Snowden, J.; Mioshi, E.; Roberts-South, A.; Benatar, M.; HortobaGyi, T.; et al. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis—Frontotemporal spectrum disorder (ALS-FTSD): Revised diagnostic criteria. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Front. Degener. 2017, 18, 153–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phukan, J.; Elamin, M.; Bede, P.; Jordan, N.; Gallagher, L.; Byrne, S.; Lynch, C.; Pender, N.; Hardiman, O. The syndrome of cognitive impairment in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A population-based study. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2012, 83, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringholz, G.M.; Appel, S.H.; Bradshaw, M.; Cooke, N.A.; Mosnik, D.M.; Schulz, P.E. Prevalence and patterns of cognitive impairment in sporadic ALS. Neurology 2005, 65, 586–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montuschi, A.; Iazzolino, B.; Calvo, A.; Moglia, C.; Lopiano, L.; Restagno, G.; Brunetti, M.; Ossola, I.; Lo Presti, A.; Cammarosano, S.; et al. Cognitive correlates in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A population-based study in Italy. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2015, 86, 168–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, S.; Ji, Y.; Li, C.; He, J.; Liu, X.; Fan, D. The Edinburgh Cognitive and Behavioural ALS Screen in a Chinese Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Population. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0155496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costello, E.; Rooney, J.; Pinto-Grau, M.; Burke, T.; Elamin, M.; Bede, P.; McMackin, R.; Dukic, S.; Vajda, A.; Heverin, M.; et al. Cognitive reserve in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS): A population-based longitudinal study. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2021, 92, 460–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finsel, J.; Uttner, I.; Vazquez Medrano, C.R.; Ludolph, A.C.; Lule, D. Cognition in the course of ALS—A meta-analysis. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Front. Degener. 2023, 24, 2–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elamin, M.; Bede, P.; Byrne, S.; Jordan, N.; Gallagher, L.; Wynne, B.; O’Brien, C.; Phukan, J.; Lynch, C.; Pender, N.; et al. Cognitive changes predict functional decline in ALS: A population-based longitudinal study. Neurology 2013, 80, 1590–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolley, S.; Goetz, R.; Factor-Litvak, P.; Murphy, J.; Hupf, J.; Lomen-Hoerth, C.; Andrews, H.; Heitzman, D.; Bedlack, R.; Katz, J.; et al. Longitudinal Screening Detects Cognitive Stability and Behavioral Deterioration in ALS Patients. Behav. Neurol. 2018, 2018, 5969137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benbrika, S.; Desgranges, B.; Eustache, F.; Viader, F. Cognitive, Emotional and Psychological Manifestations in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis at Baseline and Overtime: A Review. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McHutchison, C.A.; Wuu, J.; McMillan, C.T.; Rademakers, R.; Statland, J.; Wu, G.; Rampersaud, E.; Myers, J.; Hernandez, J.P.; Abrahams, S.; et al. Temporal course of cognitive and behavioural changes in motor neuron diseases. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2024, 95, 316–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, B.; Muthén, L.K. Integrating person-centered and variable-centered analyses: Growth mixture modeling with latent trajectory classes. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2000, 24, 882–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bampton, A.; McHutchison, C.; Talbot, K.; Benatar, M.; Thompson, A.G.; Turner, M.R. The Basis of Cognitive and Behavioral Dysfunction in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Brain Behav. 2024, 14, e70115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geser, F.; Stein, B.; Partain, M.; Elman, L.B.; McCluskey, L.F.; Xie, S.X.; Van Deerlin, V.M.; Kwong, L.K.; Lee, V.M.; Trojanowski, J.Q. Motor neuron disease clinically limited to the lower motor neuron is a diffuse TDP-43 proteinopathy. Acta Neuropathol. 2011, 121, 509–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henstridge, C.M.; Sideris, D.I.; Carroll, E.; Rotariu, S.; Salomonsson, S.; Tzioras, M.; McKenzie, C.A.; Smith, C.; von Arnim, C.A.F.; Ludolph, A.C.; et al. Synapse loss in the prefrontal cortex is associated with cognitive decline in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Acta Neuropathol. 2018, 135, 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Liu, S.H.; Wei, X.J.; Sun, H.; Ma, Z.W.; Yu, X.F. Potential of neuroimaging as a biomarker in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: From structure to metabolism. J. Neurol. 2024, 271, 2238–2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, C.; Kasper, E.; Dyrba, M.; Machts, J.; Bittner, D.; Kaufmann, J.; Mitchell, A.J.; Benecke, R.; Teipel, S.; Vielhaber, S.; et al. Cortical thinning and its relation to cognition in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurobiol. Aging 2014, 35, 240–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consonni, M.; Dalla Bella, E.; Contarino, V.E.; Bersano, E.; Lauria, G. Cortical thinning trajectories across disease stages and cognitive impairment in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Cortex 2020, 131, 284–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chenji, S.; Ishaque, A.; Mah, D.; Fujiwara, E.; Beaulieu, C.; Seres, P.; Graham, S.J.; Frayne, R.; Zinman, L.; Genge, A.; et al. Neuroanatomical associations of the Edinburgh cognitive and Behavioural ALS screen (ECAS). Brain Imaging Behav. 2021, 15, 1641–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.H.G.; Nitert, A.D.; van Veenhuijzen, K.; Dukic, S.; van Zandvoort, M.J.E.; Hendrikse, J.; van Es, M.A.; Veldink, J.H.; Westeneng, H.J.; van den Berg, L.H. Neuroimaging correlates of domain-specific cognitive deficits in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. NeuroImage Clin. 2025, 45, 103749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abrahams, S.; Goldstein, L.H.; Kew, J.J.; Brooks, D.J.; Lloyd, C.M.; Frith, C.D.; Leigh, P.N. Frontal lobe dysfunction in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. A PET study. Brain 1996, 119 Pt 6, 2105–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, H.; Li, R.; Wang, J.; Chen, H. Altered cortical hubs in functional brain networks in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurol. Sci. 2015, 36, 2097–2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canosa, A.; Moglia, C.; Manera, U.; Vasta, R.; Torrieri, M.C.; Arena, V.; D’Ovidio, F.; Palumbo, F.; Zucchetti, J.P.; Iazzolino, B.; et al. Metabolic brain changes across different levels of cognitive impairment in ALS: A 18F-FDG-PET study. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2020, 92, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foucher, J.; Oijerstedt, L.; Lovik, A.; Sun, J.; Ismail, M.A.; Sennfalt, S.; Savitcheva, I.; Estenberg, U.; Pagani, M.; Fang, F.; et al. ECAS correlation with metabolic alterations on FDG-PET imaging in ALS. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Front. Degener. 2024, 25, 708–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahriari, Y.; Besio, W.; Hosni, S.I.; Hillary Zisk, A.; Borgheai, S.B.; Deligani, R.J.; McLinden, J. Electroencephalography. In Neural Interface Engineering: Linking the Physical World and the Nervous System; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, K.S.; Khan, M.J.; Hong, M.J. Feature Extraction and Classification Methods for Hybrid fNIRS-EEG Brain-Computer Interfaces. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindquist, M.A.; Meng Loh, J.; Atlas, L.Y.; Wager, T.D. Modeling the hemodynamic response function in fMRI: Efficiency, bias and mis-modeling. NeuroImage 2009, 45, S187–S198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Wang, B.; Xu, G.; Wang, W.; Liu, Z.; Li, Z. Functional connectivity analysis using fNIRS in healthy subjects during prolonged simulated driving. Neurosci. Lett. 2017, 640, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tulay, E.E.; Metin, B.; Tarhan, N.; Arikan, M.K. Multimodal Neuroimaging: Basic Concepts and Classification of Neuropsychiatric Diseases. Clin. EEG Neurosci. 2019, 50, 20–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borgheai, S.B.; Zisk, A.H.; McLinden, J.; McIntyre, J.; Sadjadi, R.; Shahriari, Y. Multimodal pre-screening can predict BCI performance variability: A novel subject-specific experimental scheme. Comput. Biol. Med. 2024, 168, 107658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borgheai, S.B.; Deligani, R.J.; McLinden, J.; Zisk, A.; Hosni, S.I.; Abtahi, M.; Mankodiya, K.; Shahriari, Y. Multimodal exploration of non-motor neural functions in ALS patients using simultaneous EEG-fNIRS recording. J. Neural Eng. 2019, 16, 066036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deligani, R.J.; Hosni, S.I.; Borgheai, S.B.; McLinden, J.; Zisk, A.H.; Mankodiya, K.; Shahriari, Y. Electrical and Hemodynamic Neural Functions in People With ALS: An EEG-fNIRS Resting-State Study. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2020, 28, 3129–3139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosni, S.M.I.; Borgheai, S.B.; McLinden, J.; Zhu, S.; Huang, X.; Ostadabbas, S.; Shahriari, Y. A Graph-Based Nonlinear Dynamic Characterization of Motor Imagery Toward an Enhanced Hybrid BCI. Neuroinformatics 2022, 20, 1169–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menke, R.A.; Proudfoot, M.; Wuu, J.; Andersen, P.M.; Talbot, K.; Benatar, M.; Turner, M.R. Increased functional connectivity common to symptomatic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and those at genetic risk. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2016, 87, 580–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.; Chen, Q.; Huang, R.; Chen, X.; Chen, K.; Huang, X.; Tang, H.; Gong, Q.; Shang, H.F. Patterns of spontaneous brain activity in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A resting-state FMRI study. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e45470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Douaud, G.; Filippini, N.; Knight, S.; Talbot, K.; Turner, M.R. Integration of structural and functional magnetic resonance imaging in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain 2011, 134, 3470–3479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verstraete, E.; van den Heuvel, M.P.; Veldink, J.H.; Blanken, N.; Mandl, R.C.; Hulshoff Pol, H.E.; van den Berg, L.H. Motor network degeneration in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A structural and functional connectivity study. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e13664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agosta, F.; Canu, E.; Valsasina, P.; Riva, N.; Prelle, A.; Comi, G.; Filippi, M. Divergent brain network connectivity in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurobiol. Aging 2013, 34, 419–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedeschi, G.; Trojsi, F.; Tessitore, A.; Corbo, D.; Sagnelli, A.; Paccone, A.; D’Ambrosio, A.; Piccirillo, G.; Cirillo, M.; Cirillo, S.; et al. Interaction between aging and neurodegeneration in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurobiol. Aging 2012, 33, 886–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Zhou, F.; Huang, M.; Gong, H.; Xu, R. Frequency-Specific Abnormalities of Intrinsic Functional Connectivity Strength among Patients with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: A Resting-State fMRI Study. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2017, 9, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, B.; Kollewe, K.; Samii, A.; Krampfl, K.; Dengler, R.; Munte, T.F. Changes of resting state brain networks in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Exp. Neurol. 2009, 217, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraschini, M.; Demuru, M.; Hillebrand, A.; Cuccu, L.; Porcu, S.; Di Stefano, F.; Puligheddu, M.; Floris, G.; Borghero, G.; Marrosu, F. EEG functional network topology is associated with disability in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 38653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopitzki, K.; Oldag, A.; Sweeney-Reed, C.M.; Machts, J.; Veit, M.; Kaufmann, J.; Hinrichs, H.; Heinze, H.J.; Kollewe, K.; Petri, S.; et al. Interhemispheric connectivity in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A near-infrared spectroscopy and diffusion tensor imaging study. NeuroImage Clin. 2016, 12, 666–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasseroleslami, B.; Dukic, S.; Broderick, M.; Mohr, K.; Schuster, C.; Gavin, B.; McLaughlin, R.; Heverin, M.; Vajda, A.; Iyer, P.M.; et al. Characteristic Increases in EEG Connectivity Correlate With Changes of Structural MRI in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Cereb. Cortex 2019, 29, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dukic, S.; McMackin, R.; Buxo, T.; Fasano, A.; Chipika, R.; Pinto-Grau, M.; Costello, E.; Schuster, C.; Hammond, M.; Heverin, M.; et al. Patterned functional network disruption in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2019, 40, 4827–4842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, R.; Facchetti, D.; Micheli, A.; Poloni, M. Quantitative electroencephalography in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1998, 106, 383–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santhosh, J.; Bhatia, M.; Sahu, S.; Anand, S. Decreased electroencephalogram alpha band [8–13 Hz] power in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients: A study of alpha activity in an awake relaxed state. Neurol. India 2005, 53, 99–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pievani, M.; Filippini, N.; van den Heuvel, M.P.; Cappa, S.F.; Frisoni, G.B. Brain connectivity in neurodegenerative diseases—From phenotype to proteinopathy. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2014, 10, 620–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raichle, M.E. The brain’s default mode network. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2015, 38, 433–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christidi, F.; Zalonis, I.; Smyrnis, N.; Evdokimidis, I. Selective attention and the three-process memory model for the interpretation of verbal free recall in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2012, 18, 809–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbetta, M.; Shulman, G.L. Control of goal-directed and stimulus-driven attention in the brain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2002, 3, 201–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vincent, J.L.; Kahn, I.; Snyder, A.Z.; Raichle, M.E.; Buckner, R.L. Evidence for a frontoparietal control system revealed by intrinsic functional connectivity. J. Neurophysiol. 2008, 100, 3328–3342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kellmeyer, P.; Grosse-Wentrup, M.; Schulze-Bonhage, A.; Ziemann, U.; Ball, T. Electrophysiological correlates of neurodegeneration in motor and non-motor brain regions in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-implications for brain-computer interfacing. J. Neural Eng. 2018, 15, 041003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raggi, A.; Iannaccone, S.; Cappa, S.F. Event-related brain potentials in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A review of the international literature. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. 2010, 11, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abiri, R.; Borhani, S.; Sellers, E.W.; Jiang, Y.; Zhao, X. A comprehensive review of EEG-based brain-computer interface paradigms. J. Neural Eng. 2019, 16, 011001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putze, F.; Hesslinger, S.; Tse, C.Y.; Huang, Y.; Herff, C.; Guan, C.; Schultz, T. Hybrid fNIRS-EEG based classification of auditory and visual perception processes. Front. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riccio, A.; Simione, L.; Schettini, F.; Pizzimenti, A.; Inghilleri, M.; Belardinelli, M.O.; Mattia, D.; Cincotti, F. Attention and P300-based BCI performance in people with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2013, 7, 732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinkhardt, E.H.; Jurgens, R.; Becker, W.; Molle, M.; Born, J.; Ludolph, A.C.; Schreiber, H. Signs of impaired selective attention in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Neurol. 2008, 255, 532–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahriari, Y.; Vaughan, T.M.; McCane, L.M.; Allison, B.Z.; Wolpaw, J.R.; Krusienski, D.J. An exploration of BCI performance variations in people with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis using longitudinal EEG data. J. Neural Eng. 2019, 16, 056031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arico, P.; Aloise, F.; Schettini, F.; Salinari, S.; Mattia, D.; Cincotti, F. Influence of P300 latency jitter on event related potential-based brain-computer interface performance. J. Neural Eng. 2014, 11, 035008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fjell, A.M.; Rosquist, H.; Walhovd, K.B. Instability in the latency of P3a/P3b brain potentials and cognitive function in aging. Neurobiol. Aging 2009, 30, 2065–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaśkowski, P.; Verleger, R. An evaluation of methods for single-trial estimation of P3 latency. Psychophysiology 2000, 37, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zisk, A.H.; Borgheai, S.B.; McLinden, J.; Hosni, S.M.; Deligani, R.J.; Shahriari, Y. P300 latency jitter and its correlates in people with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2021, 132, 632–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutas, M.; McCarthy, G.; Donchin, E. Augmenting mental chronometry: The P300 as a measure of stimulus evaluation time. Science 1977, 197, 792–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saville, C.W.N.; Feige, B.; Kluckert, C.; Bender, S.; Biscaldi, M.; Berger, A.; Fleischhaker, C.; Henighausen, K.; Klein, C. Increased reaction time variability in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder as a response-related phenomenon: Evidence from single-trial event-related potentials. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 2015, 56, 801–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verleger, R.; Baur, N.; Metzner, M.F.; Smigasiewicz, K. The hard oddball: Effects of difficult response selection on stimulus-related P3 and on response-related negative potentials. Psychophysiology 2014, 51, 1089–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magnuson, J.R.; Iarocci, G.; Doesburg, S.M.; Moreno, S. Increased intra-subject variability of reaction times and single-trial event-related potential components in children with autism spectrum disorder. Autism Res. 2020, 13, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinstein, I.; Heeger, D.J.; Behrmann, M. Neural variability: Friend or foe? Trends Cogn. Sci. 2015, 19, 322–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ford, J.M.; White, P.; Lim, K.O.; Pfefferbaum, A. Schizophrenics have fewer and smaller P300s: A single-trial analysis. Biol. Psychiatry 1994, 35, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, J.V.; Michalewski, H.; Starr, A. Latency variability of the components of auditory event-related potentials to infrequent stimuli in aging, Alzheimer-type dementia, and depression. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol./Evoked Potentials Sect. 1988, 71, 450–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unsal, A.; Segalowitz, S.J. Sources of P300 attenuation after head injury: Single-trial amplitude, latency jitter, and EEG power. Psychophysiology 1995, 32, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schettini, F.; Risetti, M.; Aricò, P.; Formisano, R.; Babiloni, F.; Mattia, D.; Cincotti, F. P300 latency Jitter occurrence in patients with disorders of consciousness: Toward a better design for Brain Computer Interface applications. In Proceedings of the 2015 37th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), Milan, Italy, 25–29 August 2015; pp. 6178–6181. [Google Scholar]

- Van Beek, L.; Ghesquiere, P.; De Smedt, B.; Lagae, L. Arithmetic difficulties in children with mild traumatic brain injury at the subacute stage of recovery. Dev. Med. Child. Neurol. 2015, 57, 1042–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Zhang, D.; Ouyang, M.; Hong, B. Employing an active mental task to enhance the performance of auditory attention-based brain-computer interfaces. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2013, 124, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, D.L. Broca’s arrow: Evolution, prediction, and language in the brain. Anat. Rec. B New Anat. 2006, 289, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shellikeri, S.; Karthikeyan, V.; Martino, R.; Black, S.E.; Zinman, L.; Keith, J.; Yunusova, Y. The neuropathological signature of bulbar-onset ALS: A systematic review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2017, 75, 378–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, S.; Shukla, S. Mirror neurons: Enigma of the metaphysical modular brain. J. Nat. Sci. Biol. Med. 2012, 3, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrison, K.A.; Winstein, C.J.; Aziz-Zadeh, L. The mirror neuron system: A neural substrate for methods in stroke rehabilitation. Neurorehabilit. Neural Repair 2010, 24, 404–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, D.; Teixeira, S.; Lucas, M.; Yuan, T.F.; Chaves, F.; Peressutti, C.; Machado, S.; Bittencourt, J.; Menendez-Gonzalez, M.; Nardi, A.E.; et al. The mirror neuron system in post-stroke rehabilitation. Int. Arch. Med. 2013, 6, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binkofski, F.; Buccino, G. Motor functions of the Broca’s region. Brain Lang. 2004, 89, 362–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, Y.; Nam, C.S.; Kim, Y.-J.; Whang, M.C. Event-related (De) synchronization (ERD/ERS) during motor imagery tasks: Implications for brain–computer interfaces. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2011, 41, 428–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfurtscheller, G.; Lopes da Silva, F.H. Event-related EEG/MEG synchronization and desynchronization: Basic principles. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1999, 110, 1842–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfurtscheller, G.; Neuper, C. Motor imagery activates primary sensorimotor area in humans. Neurosci. Lett. 1997, 239, 65–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; He, B. Brain-computer interfaces using sensorimotor rhythms: Current state and future perspectives. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2014, 61, 1425–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasahara, T.; Terasaki, K.; Ogawa, Y.; Ushiba, J.; Aramaki, H.; Masakado, Y. The correlation between motor impairments and event-related desynchronization during motor imagery in ALS patients. BMC Neurosci. 2012, 13, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosni, S.M.; Deligani, R.J.; Zisk, A.; McLinden, J.; Borgheai, S.B.; Shahriari, Y. An exploration of neural dynamics of motor imagery for people with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Neural Eng. 2019, 17, 016005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera, M.; Bedia, M.G.; Santos, B.A.; Barandiaran, X.E. The situated HKB model: How sensorimotor spatial coupling can alter oscillatory brain dynamics. Front. Comput. Neurosci. 2013, 7, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanton, B.R.; Williams, V.C.; Leigh, P.N.; Williams, S.C.; Blain, C.R.; Giampietro, V.P.; Simmons, A. Cortical activation during motor imagery is reduced in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Brain Res. 2007, 1172, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettit, L.D.; Bastin, M.E.; Smith, C.; Bak, T.H.; Gillingwater, T.H.; Abrahams, S. Executive deficits, not processing speed relates to abnormalities in distinct prefrontal tracts in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain 2013, 136, 3290–3304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahams, S.; Leigh, P.N.; Harvey, A.; Vythelingum, G.N.; Grise, D.; Goldstein, L.H. Verbal fluency and executive dysfunction in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). Neuropsychologia 2000, 38, 734–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolley, S.C.; York, M.K.; Moore, D.H.; Strutt, A.M.; Murphy, J.; Schulz, P.E.; Katz, J.S. Detecting frontotemporal dysfunction in ALS: Utility of the ALS Cognitive Behavioral Screen (ALS-CBS). Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. 2010, 11, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobson, H.M.; Bishop, D.V.M. Mu suppression—A good measure of the human mirror neuron system? Cortex 2016, 82, 290–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobson, H.M.; Bishop, D.V. The interpretation of mu suppression as an index of mirror neuron activity: Past, present and future. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2017, 4, 160662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deiber, M.-P.; Missonnier, P.; Bertrand, O.; Gold, G.; Fazio-Costa, L.; Ibanez, V.; Giannakopoulos, P. Distinction between perceptual and attentional processing in working memory tasks: A study of phase-locked and induced oscillatory brain dynamics. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 2007, 19, 158–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, M.; Donner, T.H.; Engel, A.K. Spectral fingerprints of large-scale neuronal interactions. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2012, 13, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastos, A.M.; Vezoli, J.; Bosman, C.A.; Schoffelen, J.M.; Oostenveld, R.; Dowdall, J.R.; De Weerd, P.; Kennedy, H.; Fries, P. Visual areas exert feedforward and feedback influences through distinct frequency channels. Neuron 2015, 85, 390–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engel, A.K.; Fries, P. Beta-band oscillations—Signalling the status quo? Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2010, 20, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wimmer, K.; Ramon, M.; Pasternak, T.; Compte, A. Transitions between Multiband Oscillatory Patterns Characterize Memory-Guided Perceptual Decisions in Prefrontal Circuits. J. Neurosci. 2016, 36, 489–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spitzer, B.; Haegens, S. Beyond the Status Quo: A Role for Beta Oscillations in Endogenous Content (Re)Activation. eNeuro 2017, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgheai, S.B.; McLinden, J.; Mankodiya, K.; Shahriari, Y. Frontal Functional Network Disruption Associated with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: An fNIRS-Based Minimum Spanning Tree Analysis. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 613990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Ji, C.; Shao, A. Neurovascular Unit Dysfunction and Neurodegenerative Disorders. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumenfeld, R.S.; Ranganath, C. Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex promotes long-term memory formation through its role in working memory organization. J. Neurosci. 2006, 26, 916–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radakovic, R.; Stephenson, L.; Newton, J.; Crockford, C.; Swingler, R.; Chandran, S.; Abrahams, S. Multidimensional apathy and executive dysfunction in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Cortex 2017, 94, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, J.A.; Emory, E. Executive function and the frontal lobes: A meta-analytic review. Neuropsychol. Rev. 2006, 16, 17–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stam, C.J.; de Haan, W.; Daffertshofer, A.; Jones, B.F.; Manshanden, I.; van Cappellen van Walsum, A.M.; Montez, T.; Verbunt, J.P.; de Munck, J.C.; van Dijk, B.W.; et al. Graph theoretical analysis of magnetoencephalographic functional connectivity in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain 2009, 132, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stam, C.J. Modern network science of neurological disorders. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2014, 15, 683–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Jing, Z.; Hu, B.; Zhu, J.; Zhong, N.; Li, M.; Ding, Z.; Yang, J.; Zhang, L.; Feng, L.; et al. A resting-state brain functional network study in MDD based on minimum spanning tree analysis and the hierarchical clustering. Complexity 2017, 2017, 9514369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraga Gonzalez, G.; Van der Molen, M.J.W.; Zaric, G.; Bonte, M.; Tijms, J.; Blomert, L.; Stam, C.J.; Van der Molen, M.W. Graph analysis of EEG resting state functional networks in dyslexic readers. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2016, 127, 3165–3175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahriari, Y.; Sellers, E.W.; McCane, L.M.; Vaughan, T.M.; Krusienski, D.J. Directional brain functional interaction analysis in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. In Proceedings of the 2015 7th International IEEE/EMBS Conference on Neural Engineering (NER), Montpellier, France, 22–24 April 2015; pp. 972–975. [Google Scholar]

- Gleichgerrcht, E.; Kocher, M.; Nesland, T.; Rorden, C.; Fridriksson, J.; Bonilha, L. Preservation of structural brain network hubs is associated with less severe post-stroke aphasia. Restor. Neurol. Neurosci. 2016, 34, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, A.; Vielhaber, S.; Rodriguez-Fornells, A.; Mohammadi, B.; Munte, T.F. A neurophysiological analysis of working memory in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain Res. 2011, 1421, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dehaene, S.; Molko, N.; Cohen, L.; Wilson, A.J. Arithmetic and the brain. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2004, 14, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, E.; Moeller, K.; Glauche, V.; Weiller, C.; Willmes, K. Processing pathways in mental arithmetic—Evidence from probabilistic fiber tracking. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e55455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sammer, G.; Blecker, C.; Gebhardt, H.; Bischoff, M.; Stark, R.; Morgen, K.; Vaitl, D. Relationship between regional hemodynamic activity and simultaneously recorded EEG-theta associated with mental arithmetic-induced workload. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2007, 28, 793–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schudlo, L.C.; Chau, T. Dynamic topographical pattern classification of multichannel prefrontal NIRS signals: II. Online differentiation of mental arithmetic and rest. J. Neural Eng. 2014, 11, 016003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monden, Y.; Dan, I.; Nagashima, M.; Dan, H.; Uga, M.; Ikeda, T.; Tsuzuki, D.; Kyutoku, Y.; Gunji, Y.; Hirano, D.; et al. Individual classification of ADHD children by right prefrontal hemodynamic responses during a go/no-go task as assessed by fNIRS. NeuroImage Clin. 2015, 9, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henson, R.N.; Shallice, T.; Dolan, R.J. Right prefrontal cortex and episodic memory retrieval: A functional MRI test of the monitoring hypothesis. Brain 1999, 122 Pt 7, 1367–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Causse, M.; Chua, Z.; Peysakhovich, V.; Del Campo, N.; Matton, N. Mental workload and neural efficiency quantified in the prefrontal cortex using fNIRS. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 5222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glahn, D.C.; Ragland, J.D.; Abramoff, A.; Barrett, J.; Laird, A.R.; Bearden, C.E.; Velligan, D.I. Beyond hypofrontality: A quantitative meta-analysis of functional neuroimaging studies of working memory in schizophrenia. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2005, 25, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roos, E.; Mariosa, D.; Ingre, C.; Lundholm, C.; Wirdefeldt, K.; Roos, P.M.; Fang, F. Depression in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurology 2016, 86, 2271–2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakore, N.J.; Pioro, E.P. Depression in ALS in a large self-reporting cohort. Neurology 2016, 86, 1031–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicks, P.; Abrahams, S.; Masi, D.; Hejda-Forde, S.; Leigh, P.N.; Goldstein, L.H. Prevalence of depression in a 12-month consecutive sample of patients with ALS. Eur. J. Neurol. 2007, 14, 993–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimond, D.; Ishaque, A.; Chenji, S.; Mah, D.; Chen, Z.; Seres, P.; Beaulieu, C.; Kalra, S. White matter structural network abnormalities underlie executive dysfunction in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2017, 38, 1249–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Proudfoot, M.; Rohenkohl, G.; Quinn, A.; Colclough, G.L.; Wuu, J.; Talbot, K.; Woolrich, M.W.; Benatar, M.; Nobre, A.C.; Turner, M.R. Altered cortical beta-band oscillations reflect motor system degeneration in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2017, 38, 237–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.S.; Chen, R. Invasive and Noninvasive Brain Stimulation in Parkinson’s Disease: Clinical Effects and Future Perspectives. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2019, 106, 763–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, J.; Wessel, J.R.; Ghahremani, A.; Aron, A.R. Establishing a Right Frontal Beta Signature for Stopping Action in Scalp EEG: Implications for Testing Inhibitory Control in Other Task Contexts. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 2018, 30, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, M.R.; Kiernan, M.C. Does interneuronal dysfunction contribute to neurodegeneration in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis? Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. 2012, 13, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dukic, S.; McMackin, R.; Costello, E.; Metzger, M.; Buxo, T.; Fasano, A.; Chipika, R.; Pinto-Grau, M.; Schuster, C.; Hammond, M.; et al. Resting-state EEG reveals four subphenotypes of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain 2022, 145, 621–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, R.; Verstraete, E.; de Reus, M.A.; Veldink, J.H.; van den Berg, L.H.; van den Heuvel, M.P. Correlation between structural and functional connectivity impairment in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2014, 35, 4386–4395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smallwood Shoukry, R.F.; Clark, M.G.; Floeter, M.K. Resting State Functional Connectivity Is Decreased Globally Across the C9orf72 Mutation Spectrum. Front. Neurol. 2020, 11, 598474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geronimo, A.; Sheldon, K.E.; Broach, J.R.; Simmons, Z.; Schiff, S.J. Expansion of C9ORF72 in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis correlates with brain-computer interface performance. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 8875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dukic, S.; van Veenhuijzen, K.; Michielsen, A.; Westeneng, H.-J.; van den Berg, L.H. Resting-state EEG oscillations are reduced in asymptomatic C9orf72 repeat expansion carriers. medRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dukic, S.; van Veenhuijzen, K.; Westeneng, H.J.; McMackin, R.; van Eijk, R.P.A.; Sleutjes, B.; Nasseroleslami, B.; Hardiman, O.; van den Berg, L.H. Altered EEG Response of the Parietal Network in Asymptomatic C9orf72 Carriers. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2025, 46, e70275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trubshaw, M.; Gohil, C.; Edmond, E.; Proudfoot, M.; Yoganathan, K.; Wuu, J.; Northall, A.; Kohl, O.; Stagg, C.J.; Nobre, A.C.; et al. Divergent Brain Network Activity in Asymptomatic C9orf72 and SOD1 Variant Carriers Compared With Established Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2025, 46, e70345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasano, A.; Vacchiano, V.; Bonan, L.; McMackin, R.; Nasseroleslami, B.; Hardiman, O.; Liguori, R. Neurophysiological biomarkers of networks impairment in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Neurol. 2025, 272, 507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van den Bos, M.A.J.; Menon, P.; Pavey, N.; Higashihara, M.; Kiernan, M.C.; Vucic, S. Direct interrogation of cortical interneuron circuits in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain 2025, 148, 1169–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, S.; Rogasch, N.C.; Premoli, I.; Blumberger, D.M.; Casarotto, S.; Chen, R.; Di Lazzaro, V.; Farzan, F.; Ferrarelli, F.; Fitzgerald, P.B.; et al. Clinical utility and prospective of TMS-EEG. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2019, 130, 802–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codina, T.; Blankertz, B.; von Luhmann, A. Multimodal fNIRS-EEG sensor fusion: Review of data-driven methods and perspective for naturalistic brain imaging. Imaging Neurosci. 2025, 3, IMAG.a.974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Shore, J.; Wang, M.; Yuan, F.; Buss, A.; Zhao, X. A systematic review on hybrid EEG/fNIRS in brain-computer interface. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2021, 68, 102595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Yu, K.; Bi, Y.; Ji, X.; Zhang, D. Strategic Integration: A Cross-Disciplinary Review of the fNIRS-EEG Dual-Modality Imaging System for Delivering Multimodal Neuroimaging to Applications. Brain Sci. 2024, 14, 1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.; Yang, D.; Fang, F.; Hong, K.-S.; Reiss, A.L.; Zhang, Y. Concurrent fNIRS and EEG for Brain Function Investigation: A Systematic, Methodology-Focused Review. Sensors 2022, 22, 5865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Zhang, X.; Chen, G.; Li, F. EEG and fNIRS-Based Emotion Recognition Using an Improved Graph Isomorphism Network. In Neural Computing for Advanced Applications; Springer: Singapore; pp. 394–408.

- Zhu, S.; Hosni, S.I.; Huang, X.; Wan, M.; Borgheai, S.B.; McLinden, J.; Shahriari, Y.; Ostadabbas, S. A dynamical graph-based feature extraction approach to enhance mental task classification in brain–computer interfaces. Comput. Biol. Med. 2023, 153, 106498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, Y.; Zhao, K.; Wei, X.; Carlisle, N.B.; Keller, C.J.; Oathes, D.J.; Fonzo, G.A.; Zhang, Y. Deep graph learning of multimodal brain networks defines treatment-predictive signatures in major depression. Mol. Psychiatry 2025, 30, 3963–3974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Gene | Frequency | Typical Age of Onset | Phenotypic Tendencies | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOD1 | ~20% of fALS | 40–60 | Limb-onset; variable progression depending on mutation | Some variants are aggressive, others slow |

| C9ORF72 | ~34% of fALS | 40–70 | Bulbar-onset more common; psychiatric symptoms; ALS-FTD overlap | Immune and autophagy dysfunction |

| TARDBP (TDP-43) | 3–5% of fALS | 50 s | Slow progression except certain variants (e.g., G376D) | RNA metabolism defects |

| FUS | 4–5% of fALS | Juvenile–adult | Aggressive, early onset; often cognitive symptoms | Nuclear transport defects |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Borgheai, S.B.; Achorn, B.E.; Zisk, A.H.; Hosni, S.M.; Richter, K.E.G.; Menniti, F.S.; Shahriari, Y. A Comprehensive Overview of Neurophysiological Correlates of Cognitive Impairment in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Cells 2026, 15, 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010037

Borgheai SB, Achorn BE, Zisk AH, Hosni SM, Richter KEG, Menniti FS, Shahriari Y. A Comprehensive Overview of Neurophysiological Correlates of Cognitive Impairment in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Cells. 2026; 15(1):37. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010037

Chicago/Turabian StyleBorgheai, Seyyed Bahram, Brie E. Achorn, Alyssa H. Zisk, Sarah M. Hosni, Karl E. G. Richter, Frank S. Menniti, and Yalda Shahriari. 2026. "A Comprehensive Overview of Neurophysiological Correlates of Cognitive Impairment in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis" Cells 15, no. 1: 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010037

APA StyleBorgheai, S. B., Achorn, B. E., Zisk, A. H., Hosni, S. M., Richter, K. E. G., Menniti, F. S., & Shahriari, Y. (2026). A Comprehensive Overview of Neurophysiological Correlates of Cognitive Impairment in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Cells, 15(1), 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010037