Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms of Non-Invasive Brain Stimulation Techniques: A Systematic Review on the Implications for the Treatment of Neurological Disorders

Highlights

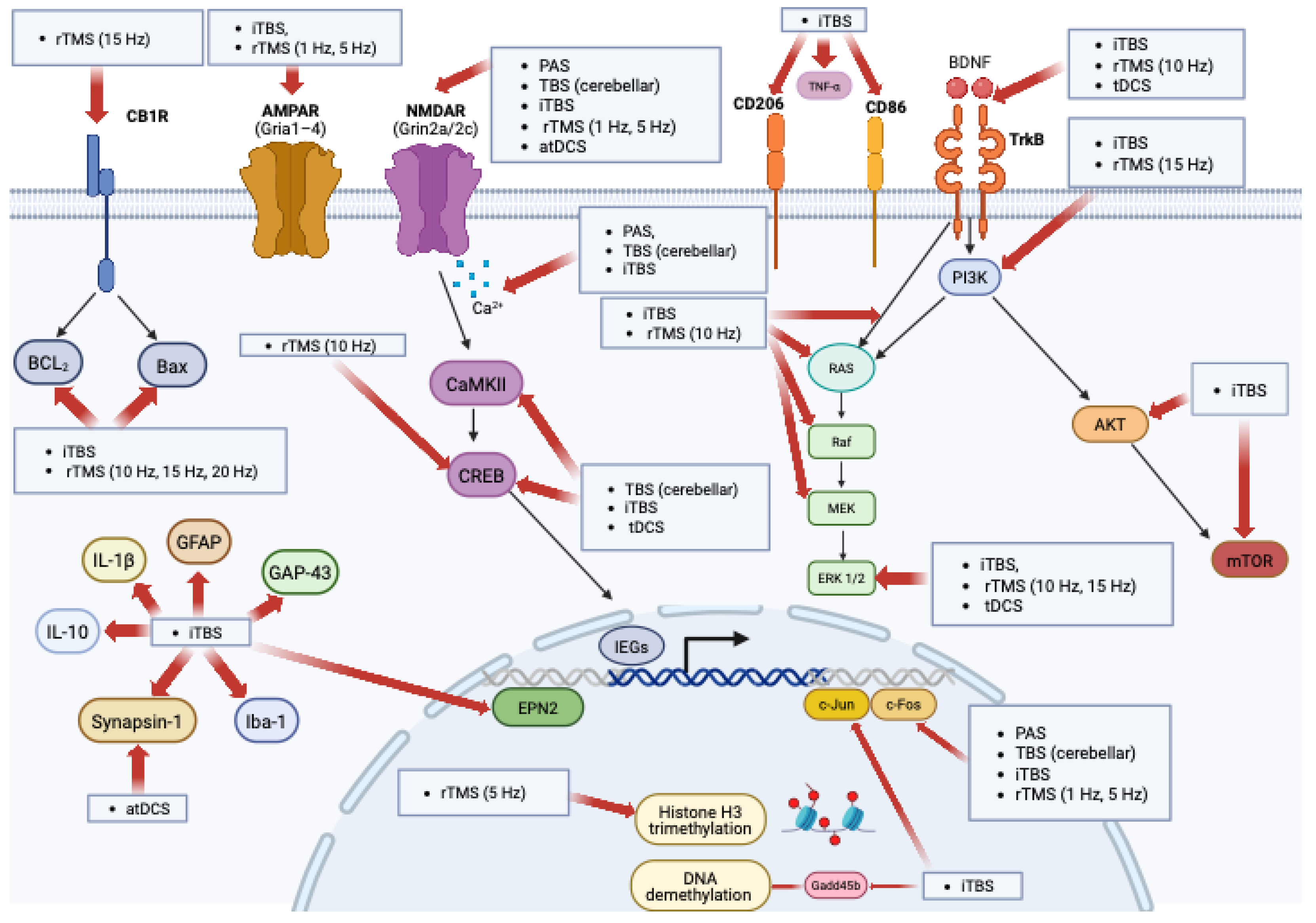

- NIBS effects involve multiple, interacting plasticity pathways that extend beyond a simple LTP/LTD framework

- Across studies, NIBS modulates BDNF–TrkB signaling, neurotransmitter receptor activity (NMDA/AMPA, GABA), and calcium-dependent mechanisms supporting synaptic plasticity

- Mechanistic biomarkers—rather than MEP-based LTP/LTD interpretations alone—are needed to guide and optimize NIBS protocols

- The involvement of conserved plasticity pathways supports the translational potential of NIBS for CNS disorders, although further cross-species validation is required

Abstract

1. Introduction

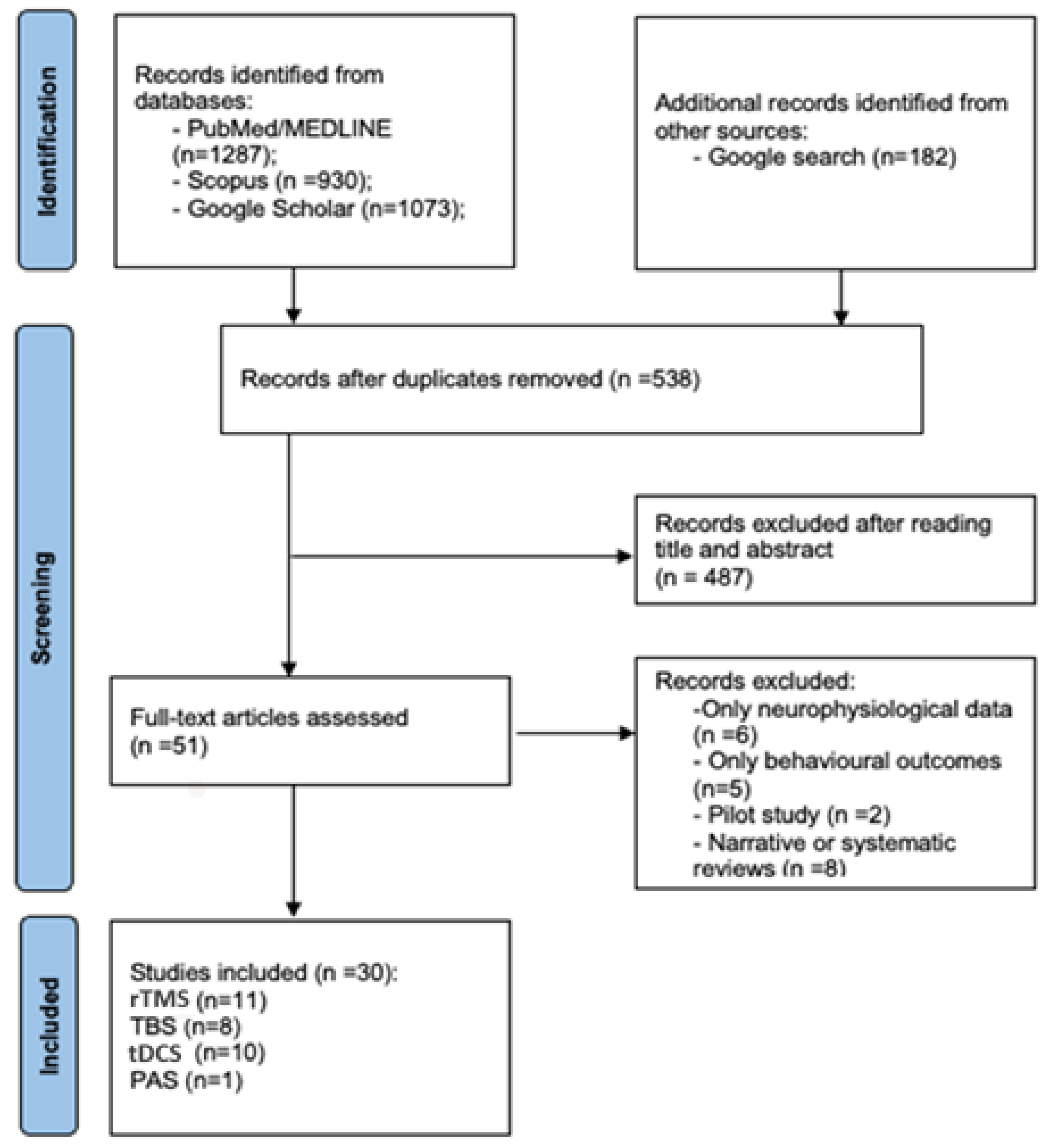

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. TMS Protocols

3.1.1. rTMS

3.1.2. Theta Burst Stimulation

3.1.3. PAS

3.2. tES

3.2.1. tDCS

3.2.2. tACS

4. Discussion

Future Directions and Limitation of Translation in Humans

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Polanía, R.; Nitsche, M.A.; Ruff, C.C. Studying and modifying brain function with non-invasive brain stimulation. Nat. Neurosci. 2018, 21, 174–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharya, A.; Mrudula, K.; Sreepada, S.S.; Sathyaprabha, T.N.; Pal, P.K.; Chen, R.; Udupa, K. An Overview of Noninvasive Brain Stimulation: Basic Principles and Clinical Applications. Can. J. Neurol. Sci. 2022, 49, 479–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desarkar, P.; Vicario, C.M.; Soltanlou, M. Non-invasive brain stimulation in research and therapy. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 29334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lefaucheur, J.P.; Aleman, A.; Baeken, C.; Benninger, D.H.; Brunelin, J.; Di Lazzaro, V.; Filipović, S.R.; Grefkes, C.; Hasan, A.; Hummel, F.C.; et al. Evidence-based guidelines on the therapeutic use of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS): An update (2014–2018). Clin. Neurophysiol. 2020, 131, 474–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trapp, N.T.; Purgianto, A.; Taylor, J.J.; Singh, M.K.; Oberman, L.M.; Mickey, B.J.; Youssef, N.A.; Solzbacher, D.; Zebley, B.; Cabrera, L.Y.; et al. Consensus review and considerations on TMS to treat depression: A comprehensive update endorsed by the National Network of Depression Centers, the Clinical TMS Society, and the International Federation of Clinical Neurophysiology. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2025, 170, 206–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latorre, A.; Rocchi, L.; Berardelli, A.; Bhatia, K.P.; Rothwell, J.C. The use of transcranial magnetic stimulation as a treatment for movement disorders: A critical review. Mov. Disord. 2019, 34, 769–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, Y.H.; Ton That, V.; Sundman, M. A systematic review and meta-analysis of rTMS effects on cognitive enhancement in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 2020, 86, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, G.; Spampinato, D. Alzheimer disease and neuroplasticity. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2022, 184, 473–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.C.; Stinear, C.M. Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) in stroke: Ready for clinical practice? J. Clin. Neurosci. 2016, 31, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sveva, V.; Cruciani, A.; Mancuso, M.; Santoro, F.; Latorre, A.; Monticone, M.; Rocchi, L. Cerebellar Non-Invasive Brain Stimulation: A Frontier in Chronic Pain Therapy. J. Pers. Med. 2024, 14, 675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanHaerents, S.; Chang, B.S.; Rotenberg, A.; Pascual-Leone, A.; Shafi, M.M. Noninvasive Brain Stimulation in Epilepsy. J. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2020, 37, 118–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, L.; Zhang, X.; Li, X.; Rong, X.; Peng, Y. The efficacy of transcranial magnetic stimulation on migraine: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trails. J. Headache Pain 2017, 18, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magee, J.C.; Grienberger, C. Synaptic Plasticity Forms and Functions. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2020, 43, 95–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Citri, A.; Malenka, R.C. Synaptic plasticity: Multiple forms, functions, and mechanisms. Neuropsychopharmacology 2008, 33, 18–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Runge, K.; Cardoso, C.; de Chevigny, A. Dendritic Spine Plasticity: Function and Mechanisms. Front. Synaptic Neurosci. 2020, 12, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granger, A.J.; Nicoll, R.A. Expression mechanisms underlying long-term potentiation: A postsynaptic view, 10 years on. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2014, 369, 20130136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumi, T.; Harada, K. Mechanism underlying hippocampal long-term potentiation and depression based on competition between endocytosis and exocytosis of AMPA receptors. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 14711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caporale, N.; Dan, Y. Spike timing-dependent plasticity: A Hebbian learning rule. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2008, 31, 25–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozo, K.; Goda, Y. Unraveling mechanisms of homeostatic synaptic plasticity. Neuron 2010, 66, 337–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karabanov, A.; Ziemann, U.; Hamada, M.; George, M.S.; Quartarone, A.; Classen, J.; Massimini, M.; Rothwell, J.; Siebner, H.R. Consensus Paper: Probing Homeostatic Plasticity of Human Cortex with Non-invasive Transcranial Brain Stimulation. Brain Stimul. 2015, 8, 993–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiev, D.; Rocchi, L.; Tocco, P.; Speekenbrink, M.; Rothwell, J.C.; Jahanshahi, M. Continuous Theta Burst Stimulation over the Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex and the Pre-SMA Alter Drift Rate and Response Thresholds Respectively During Perceptual Decision-Making. Brain Stimul. 2016, 9, 601–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendez, J.C.; Rocchi, L.; Jahanshahi, M.; Rothwell, J.; Merchant, H. Probing the timing network: A continuous theta burst stimulation study of temporal categorization. Neuroscience 2017, 356, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumitru, A.; Rocchi, L.; Saini, F.; Rothwell, J.C.; Roiser, J.P.; David, A.S.; Richieri, R.M.; Lewis, G.; Lewis, G. Influence of theta-burst transcranial magnetic stimulation over the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex on emotion processing in healthy volunteers. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 2020, 20, 1278–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bestmann, S.; Krakauer, J.W. The uses and interpretations of the motor-evoked potential for understanding behaviour. Exp. Brain Res. 2015, 233, 679–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klink, K.; Paßmann, S.; Kasten, F.H.; Peter, J. The Modulation of Cognitive Performance with Transcranial Alternating Current Stimulation: A Systematic Review of Frequency-Specific Effects. Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruciani, A.; Mancuso, M.; Sveva, V.; Maccarrone, D.; Todisco, A.; Motolese, F.; Santoro, F.; Pilato, F.; Spampinato, D.A.; Rocchi, L.; et al. Using TMS-EEG to assess the effects of neuromodulation techniques: A narrative review. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1247104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delvendahl, I.; Jung, N.H.; Kuhnke, N.G.; Ziemann, U.; Mall, V. Plasticity of motor threshold and motor-evoked potential amplitude—A model of intrinsic and synaptic plasticity in human motor cortex? Brain Stimul. 2012, 5, 586–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawji, V.; Latorre, A.; Sharma, N.; Rothwell, J.C.; Rocchi, L. On the Use of TMS to Investigate the Pathophysiology of Neurodegenerative Diseases. Front. Neurol. 2020, 11, 584664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanardi, R.; Magri, L.; Rossini, D.; Malaguti, A.; Giordani, S.; Lorenzi, C.; Pirovano, A.; Smeraldi, E.; Lucca, A. Role of serotonergic gene polymorphisms on response to transcranial magnetic stimulation in depression. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2007, 17, 651–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hille, M.; Kühn, S.; Kempermann, G.; Bonhoeffer, T.; Lindenberger, U. From animal models to human individuality: Integrative approaches to the study of brain plasticity. Neuron 2024, 112, 3522–3541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, S.F.; Bliss, T.V. Plasticity in the human central nervous system. Brain 2006, 129, 1659–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrade-Talavera, Y.; Pérez-Rodríguez, M.; Prius-Mengual, J.; Rodríguez-Moreno, A. Neuronal and astrocyte determinants of critical periods of plasticity. Trends Neurosci. 2023, 46, 566–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heldt, S.A.; Stanek, L.; Chhatwal, J.P.; Ressler, K.J. Hippocampus-specific deletion of BDNF in adult mice impairs spatial memory and extinction of aversive memories. Mol. Psychiatry 2007, 12, 656–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheeran, B.; Talelli, P.; Mori, F.; Koch, G.; Suppa, A.; Edwards, M.; Houlden, H.; Bhatia, K.; Greenwood, R.; Rothwell, J.C. A common polymorphism in the brain-derived neurotrophic factor gene (BDNF) modulates human cortical plasticity and the response to rTMS. J. Physiol. 2008, 586, 5717–5725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geng, H.; Chen, H.; Wang, H.; Wang, L. The Histone Modifications of Neuronal Plasticity. Neural Plast. 2021, 2021, 6690523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullian, E.M.; Sapperstein, S.K.; Christopherson, K.S.; Barres, B.A. Control of synapse number by glia. Science 2001, 291, 657–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagai, J.; Yu, X.; Papouin, T.; Cheong, E.; Freeman, M.R.; Monk, K.R.; Hastings, M.H.; Haydon, P.G.; Rowitch, D.; Shaham, S.; et al. Behaviorally consequential astrocytic regulation of neural circuits. Neuron 2021, 109, 576–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, D.W.; Wills, Z.P.; Fish, K.N.; Lewis, D.A. Developmental pruning of excitatory synaptic inputs to parvalbumin interneurons in monkey prefrontal cortex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E629–E637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Kim, J.Y.; Noh, S.; Lee, H.; Lee, S.Y.; Mun, J.Y.; Park, H.; Chung, W.S. Astrocytes phagocytose adult hippocampal synapses for circuit homeostasis. Nature 2021, 590, 612–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, S.; Gharagozloo, M.; Simard, C.; Gris, D. Astrocytes Maintain Glutamate Homeostasis in the CNS by Controlling the Balance between Glutamate Uptake and Release. Cells 2019, 8, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lines, J.; Corkrum, M.; Aguilar, J.; Araque, A. The Duality of Astrocyte Neuromodulation: Astrocytes Sense Neuromodulators and Are Neuromodulators. J. Neurochem. 2025, 169, e70054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baek, A.; Kim, J.H.; Pyo, S.; Jung, J.H.; Park, E.J.; Kim, S.H.; Cho, S.R. The Differential Effects of Repetitive Magnetic Stimulation in an In Vitro Neuronal Model of Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury. Front. Neurol. 2018, 9, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, S.F.; Shi, T.Y.; Fan, Y.; Wang, W.N.; Chen, Y.C.; Tan, Q.R. Long-lasting effects of chronic rTMS to treat chronic rodent model of depression. Behav. Brain Res. 2012, 232, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, F.; Wang, S.; Guo, Y.; Wang, J.; Lou, M.; Wu, J.; Ding, M.; Tian, M.; Zhang, H. Protective effects of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in a rat model of transient cerebral ischaemia: A microPET study. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2010, 37, 954–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Lou, J.; Han, X.; Deng, Y.; Huang, X. Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation Ameliorates Cognitive Impairment by Enhancing Neurogenesis and Suppressing Apoptosis in the Hippocampus in Rats with Ischemic Stroke. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, W.; Choi, J.K.; Bang, M.S.; Park, W.Y.; Oh, B.M. Gene Expression Profile Changes in the Stimulated Rat Brain Cortex After Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation. Brain Neurorehabil. 2022, 15, e27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.K.; Lee, G.Y.; Kim, S.K.; Kwon, Y.J.; Seo, E.B.; Lee, H.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, S.J.; Lee, S.; Ye, S.K. Protective Effects of Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation Against Streptozotocin-Induced Alzheimer’s Disease. Mol. Neurobiol. 2024, 61, 1687–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNerney, M.W.; Heath, A.; Narayanan, S.K.; Yesavage, J. Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation Improves Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor and Cholinergic Signaling in the 3xTgAD Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2022, 86, 499–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meneses-San Juan, D.; Lamas, M.; Ramírez-Rodríguez, G.B. Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation Reduces Depressive-like Behaviors, Modifies Dendritic Plasticity, and Generates Global Epigenetic Changes in the Frontal Cortex and Hippocampus in a Rodent Model of Chronic Stress. Cells 2023, 12, 2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.Y.; Crupi, D.; Liu, J.; Stucky, A.; Cruciata, G.; Di Rocco, A.; Friedman, E.; Quartarone, A.; Ghilardi, M.F. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation enhances BDNF-TrkB signaling in both brain and lymphocyte. J. Neurosci. 2011, 31, 11044–11054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.N.; Wang, L.; Zhang, R.G.; Chen, Y.C.; Liu, L.; Gao, F.; Nie, H.; Hou, W.G.; Peng, Z.W.; Tan, Q. Anti-depressive mechanism of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in rat: The role of the endocannabinoid system. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2014, 51, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiler, M.; Stieger, K.C.; Shroff, K.; Klein, J.P.; Wood, W.H., 3rd; Zhang, Y.; Chandrasekaran, P.; Lehrmann, E.; Camandola, S.; Long, J.M.; et al. Transcriptional changes in the rat brain induced by repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1215291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Battaglia, F.; Wang, H.Y.; Ghilardi, M.F.; Gashi, E.; Quartarone, A.; Friedman, E.; Nixon, R.A. Cortical plasticity in Alzheimer’s disease in humans and rodents. Biol. Psychiatry 2007, 62, 1405–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gandolfi, D.; Cerri, S.; Mapelli, J.; Polimeni, M.; Tritto, S.; Fuzzati-Armentero, M.T.; Bigiani, A.; Blandini, F.; Mapelli, L.; D’Angelo, E. Activation of the CREB/c-Fos Pathway during Long-Term Synaptic Plasticity in the Cerebellum Granular Layer. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2017, 11, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, S.; Wang, X.; Yang, X.; Ouyang, S.; Pan, X.; Fu, Y.; Wu, S. Long-term iTBS Improves Neural Functional Recovery by Reducing the Inflammatory Response and Inhibiting Neuronal Apoptosis Via miR-34c-5p/p53/Bax Signaling Pathway in Cerebral Ischemic Rats. Neuroscience 2023, 527, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, F.Y.; Krishnan, M.; Jayaraj, R.L.; Bru-Mercier, G.; Pessia, M.; Ljubisavljevic, M.R. Time dependent changes in protein expression induced by intermittent theta burst stimulation in a cell line. Front. Neurol. 2024, 15, 1396776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labedi, A.; Benali, A.; Mix, A.; Neubacher, U.; Funke, K. Modulation of inhibitory activity markers by intermittent theta-burst stimulation in rat cortex is NMDA-receptor dependent. Brain Stimul. 2014, 7, 394–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ljubisavljevic, M.R.; Javid, A.; Oommen, J.; Parekh, K.; Nagelkerke, N.; Shehab, S.; Adrian, T.E. The Effects of Different Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (rTMS) Protocols on Cortical Gene Expression in a Rat Model of Cerebral Ischemic-Reperfusion Injury. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0139892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stekic, A.; Zeljkovic, M.; Zaric Kontic, M.; Mihajlovic, K.; Adzic, M.; Stevanovic, I.; Ninkovic, M.; Grkovic, I.; Ilic, T.V.; Nedeljkovic, N.; et al. Intermittent Theta Burst Stimulation Ameliorates Cognitive Deficit and Attenuates Neuroinflammation via PI3K/Akt/mTOR Signaling Pathway in Alzheimer’s-Like Disease Model. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 889983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, A.C.; Kenis, G.; Tielens, S.; de Graaf, T.A.; Schuhmann, T.; Rutten, B.P.F.; Sack, A.T. Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation-Induced Plasticity Mechanisms: TMS-Related Gene Expression and Morphology Changes in a Human Neuron-Like Cell Model. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2020, 13, 528396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Liu, J.; Hui, Y.; Wu, Z.; Wang, L.; Wang, Y.; Bai, Y.; Li, J.; Zhang, L.; Xi, Y.; et al. Long-term intermittent theta burst stimulation enhanced hippocampus-dependent memory by regulating hippocampal theta oscillation and neurotransmitter levels in healthy rats. Neurochem. Int. 2024, 173, 105671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agrawal, B.; Boulos, S.; Khatib, S.; Feuermann, Y.; Panov, J.; Kaphzan, H. Molecular Insights into Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation Effects: Metabolomics and Transcriptomics Analyses. Cells 2024, 13, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cancel, L.M.; Silas, D.; Bikson, M.; Tarbell, J.M. Direct current stimulation modulates gene expression in isolated astrocytes with implications for glia-mediated plasticity. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 17964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmes, B.; Jung, S.H.; Lu, J.; Wagner, J.A.; Rubbi, L.; Pellegrini, M.; Jankord, R. Transcriptomic Modification in the Cerebral Cortex following Noninvasive Brain Stimulation: RNA-Sequencing Approach. Neural Plast. 2016, 2016, 5942980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.S.; Koo, H.; Han, S.W.; Paulus, W.; Nitsche, M.A.; Kim, Y.-H.; A Yoon, J.; Shin, Y.-I. Repeated anodal transcranial direct current stimulation induces neural plasticity-associated gene expression in the rat cortex and hippocampus. Restor. Neurol. Neurosci. 2017, 35, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, V.; Barbati, S.A.; Re, A.; Paciello, F.; Bolla, M.; Rinaudo, M.; Miraglia, F.; Alù, F.; Di Donna, M.G.; Vecchio, F.; et al. Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation Enhances Neuroplasticity and Accelerates Motor Recovery in a Stroke Mouse Model. Stroke 2022, 53, 1746–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magri, C.; Vitali, E.; Cocco, S.; Giacopuzzi, E.; Rinaudo, M.; Martini, P.; Barbon, A.; Grassi, C.; Gennarelli, M. Whole Blood Transcriptome Characterization of 3xTg-AD Mouse and Its Modulation by Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation (tDCS). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podda, M.V.; Cocco, S.; Mastrodonato, A.; Fusco, S.; Leone, L.; Barbati, S.A.; Colussi, C.; Ripoli, C.; Grassi, C. Anodal transcranial direct current stimulation boosts synaptic plasticity and memory in mice via epigenetic regulation of Bdnf expression. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 22180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-León, C.A.; Cordones, I.; Ammann, C.; Ausín, J.M.; Gómez-Climent, M.A.; Carretero-Guillén, A.; Campos, G.S.-G.; Gruart, A.; Delgado-García, J.M.; Cheron, G.; et al. Immediate and after effects of transcranial direct-current stimulation in the mouse primary somatosensory cortex. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 3123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Lipton, J.O.; Boyle, L.M.; Madsen, J.R.; Goldenberg, M.C.; Pascual-Leone, A.; Sahin, M.; Rotenberg, A. Direct current stimulation induces mGluR5-dependent neocortical plasticity. Ann. Neurol. 2016, 80, 233–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, H.L.; Pikhovych, A.; Endepols, H.; Rotthues, S.; Bärmann, J.; Backes, H.; Hoehn, M.; Wiedermann, D.; Neumaier, B.; Fink, G.R.; et al. Transcranial-Direct-Current-Stimulation Accelerates Motor Recovery After Cortical Infarction in Mice: The Interplay of Structural Cellular Responses and Functional Recovery. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair 2022, 36, 701–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannah, R.; Rocchi, L.; Tremblay, S.; Rothwell, J.C. Controllable Pulse Parameter TMS and TMS-EEG As Novel Approaches to Improve Neural Targeting with rTMS in Human Cerebral Cortex. Front. Neural Circuits 2016, 10, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefaucheur, J.P. Transcranial magnetic stimulation. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2019, 160, 559–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.Z.; Edwards, M.J.; Rounis, E.; Bhatia, K.P.; Rothwell, J.C. Theta burst stimulation of the human motor cortex. Neuron 2005, 45, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossini, P.M.; Burke, D.; Chen, R.; Cohen, L.; Daskalakis, Z.; Di Iorio, R.; Di Lazzaro, V.; Ferreri, F.; Fitzgerald, P.; George, M. Non-invasive electrical and magnetic stimulation of the brain, spinal cord, roots and peripheral nerves: Basic principles and procedures for routine clinical and research application. An updated report from an IFCN Committee. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2015, 126, 1071–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Biasio, F.; Conte, A.; Bologna, M.; Iezzi, E.; Rocchi, L.; Modugno, N.; Berardelli, A. Does the cerebellum intervene in the abnormal somatosensory temporal discrimination in Parkinson’s disease? Park. Relat. Disord. 2015, 21, 789–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocchi, L.; Spampinato, D.A.; Pezzopane, V.; Orth, M.; Bisiacchi, P.S.; Rothwell, J.C.; Casula, E.P. Cerebellar noninvasive neuromodulation influences the reactivity of the contralateral primary motor cortex and surrounding areas: A TMS-EMG-EEG study. Cerebellum 2023, 22, 319–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rounis, E.; Huang, Y.Z. Theta burst stimulation in humans: A need for better understanding effects of brain stimulation in health and disease. Exp. Brain Res. 2020, 238, 1707–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suppa, A.; Huang, Y.Z.; Funke, K.; Ridding, M.C.; Cheeran, B.; Di Lazzaro, V.; Ziemann, U.; Rothwell, J.C. Ten Years of Theta Burst Stimulation in Humans: Established Knowledge, Unknowns and Prospects. Brain Stimul. 2016, 9, 323–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefan, K.; Kunesch, E.; Cohen, L.G.; Benecke, R.; Classen, J. Induction of plasticity in the human motor cortex by paired associative stimulation. Brain 2000, 123, 572–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suppa, A.; Li Voti, P.; Rocchi, L.; Papazachariadis, O.; Berardelli, A. Early visuomotor integration processes induce LTP/LTD-like plasticity in the human motor cortex. Cereb. Cortex 2015, 25, 703–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conte, A.; Li Voti, P.; Pontecorvo, S.; Quartuccio, M.E.; Baione, V.; Rocchi, L.; Cortese, A.; Bologna, M.; Francia, A.; Berardelli, A. Attention-related changes in short-term cortical plasticity help to explain fatigue in multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. 2016, 22, 1359–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batsikadze, G.; Paulus, W.; Kuo, M.F.; Nitsche, M.A. Effect of serotonin on paired associative stimulation-induced plasticity in the human motor cortex. Neuropsychopharmacology 2013, 38, 2260–2267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silverstein, J.; Cortes, M.; Tsagaris, K.Z.; Climent, A.; Gerber, L.M.; Oromendia, C.; Fonzetti, P.; Ratan, R.R.; Kitago, T.; Iacoboni, M.; et al. Paired Associative Stimulation as a Tool to Assess Plasticity Enhancers in Chronic Stroke. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sohn, M.N.; Brown, J.C.; Sharma, P.; Ziemann, U.; McGirr, A. Pharmacological adjuncts and transcranial magnetic stimulation-induced synaptic plasticity: A systematic review. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2024, 49, E59–E76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tampi, R.R. Paired associative stimulation (PAS) and Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Int. Psychogeriatr. 2023, 35, 123–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nejati, V.; Vaziri, Z.; Antal, A.; Antonenko, D.; Behroozmand, R.; Bestmann, S.; Brunelin, J.; Brunoni, A.R.; Carvalho, S.; Davis, N.J.; et al. Report Approval for Transcranial Electrical Stimulation (RATES): Expert recommendation based on a Delphi consensus study. Nat. Protoc. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitsche, M.A.; Paulus, W. Excitability changes induced in the human motor cortex by weak transcranial direct current stimulation. J. Physiol. 2000, 527, 633–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jannati, A.; Oberman, L.M.; Rotenberg, A.; Pascual-Leone, A. Assessing the mechanisms of brain plasticity by transcranial magnetic stimulation. Neuropsychopharmacology 2023, 48, 191–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latorre, A.; Rocchi, L.; Paparella, G.; Manzo, N.; Bhatia, K.P.; Rothwell, J.C. Changes in cerebellar output abnormally modulate cortical myoclonus sensorimotor hyperexcitability. Brain 2024, 147, 1412–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebetanz, D.; Nitsche, M.A.; Tergau, F.; Paulus, W. Pharmacological approach to the mechanisms of transcranial DC-stimulation-induced after-effects of human motor cortex excitability. Brain 2002, 125, 2238–2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nitsche, M.A.; Fricke, K.; Henschke, U.; Schlitterlau, A.; Liebetanz, D.; Lang, N.; Henning, S.; Tergau, F.; Paulus, W. Pharmacological modulation of cortical excitability shifts induced by transcranial direct current stimulation in humans. J. Physiol. 2003, 553, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nitsche, M.A.; Liebetanz, D.; Schlitterlau, A.; Henschke, U.; Fricke, K.; Frommann, K.; Lang, N.; Henning, S.; Paulus, W.; Tergau, F. GABAergic modulation of DC stimulation-induced motor cortex excitability shifts in humans. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2004, 19, 2720–2726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosayebi-Samani, M.; Melo, L.; Agboada, D.; Nitsche, M.A.; Kuo, M.F. Ca2+ channel dynamics explain the nonlinear neuroplasticity induction by cathodal transcranial direct current stimulation over the primary motor cortex. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2020, 38, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitsche, M.A.; Lampe, C.; Antal, A.; Liebetanz, D.; Lang, N.; Tergau, F.; Paulus, W. Dopaminergic modulation of long-lasting direct current-induced cortical excitability changes in the human motor cortex. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2006, 23, 1651–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, M.F.; Grosch, J.; Fregni, F.; Paulus, W.; Nitsche, M.A. Focusing effect of acetylcholine on neuroplasticity in the human motor cortex. J. Neurosci. 2007, 27, 14442–14447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akaneya, Y.; Tsumoto, T.; Kinoshita, S.; Hatanaka, H. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor enhances long-term potentiation in rat visual cortex. J. Neurosci. 1997, 17, 6707–6716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balkowiec, A.; Katz, D.M. Cellular mechanisms regulating activity-dependent release of native brain-derived neurotrophic factor from hippocampal neurons. J. Neurosci. 2002, 22, 10399–10407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, B. BDNF and activity-dependent synaptic modulation. Learn. Mem. 2003, 10, 86–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritsch, B.; Reis, J.; Martinowich, K.; Schambra, H.M.; Ji, Y.; Cohen, L.G.; Lu, B. Direct current stimulation promotes BDNF-dependent synaptic plasticity: Potential implications for motor learning. Neuron 2010, 66, 198–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruohonen, J.; Karhu, J. tDCS possibly stimulates glial cells. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2012, 123, 2006–2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sala, G.; Bocci, T.; Borzì, V.; Parazzini, M.; Priori, A.; Ferrarese, C. Direct current stimulation enhances neuronal alpha-synuclein degradation in vitro. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fridriksson, J.; Elm, J.; Stark, B.C.; Basilakos, A.; Rorden, C.; Sen, S.; George, M.S.; Gottfried, M.; Bonilha, L. BDNF genotype and tDCS interaction in aphasia treatment. Brain Stimul. 2018, 11, 1276–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunoni, A.R.; Carracedo, A.; Amigo, O.M.; Pellicer, A.L.; Talib, L.; Carvalho, A.F.; Lotufo, P.A.; Benseñor, I.M.; Gattaz, W.; Cappi, C. Association of BDNF, HTR2A, TPH1, SLC6A4, and COMT polymorphisms with tDCS and escitalopram efficacy: Ancillary analysis of a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Braz. J. Psychiatry 2020, 42, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, C.; Wang, J.; Li, J.; Wang, J.; Zhang, L.; Yin, C.; Li, Y. Repetitive anodal transcranial direct current stimulation improves neurological recovery by preserving the neuroplasticity in an asphyxial rat model of cardiac arrest. Brain Stimul. 2021, 14, 407–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumontoy, S.; Ramadan, B.; Risold, P.Y.; Pedron, S.; Houdayer, C.; Etiévant, A.; Cabeza, L.; Haffen, E.; Peterschmitt, Y.; Van Waes, V. Repeated Anodal Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation (RA-tDCS) over the Left Frontal Lobe Increases Bilateral Hippocampal Cell Proliferation in Young Adult but Not Middle-Aged Female Mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 8750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardolino, G.; Bossi, B.; Barbieri, S.; Priori, A. Non-synaptic mechanisms underlie the after-effects of cathodal transcutaneous direct current stimulation of the human brain. J. Physiol. 2005, 568, 653–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spampinato, D.; Ibanez, J.; Spanoudakis, M.; Hammond, P.; Rothwell, J.C. Cerebellar transcranial magnetic stimulation: The role of coil type from distinct manufacturers. Brain Stimul. 2020, 13, 135–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korai, S.A.; Ranieri, F.; Di Lazzaro, V.; Papa, M.; Cirillo, G. Neurobiological After-Effects of Low Intensity Transcranial Electric Stimulation of the Human Nervous System: From Basic Mechanisms to Metaplasticity. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 587771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wischnewski, M.; Alekseichuk, I.; Opitz, A. Neurocognitive, physiological, and biophysical effects of transcranial alternating current stimulation. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2023, 27, 189–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirsch, D.L.; Nichols, F. Cranial electrotherapy stimulation for treatment of anxiety, depression, and insomnia. Psychiatr. Clin. North. Am. 2013, 36, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Limoge, A.; Robert, C.; Stanley, T.H. Transcutaneous cranial electrical stimulation (TCES): A review 1998. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 1999, 23, 529–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Peng, R.Y. Basic roles of key molecules connected with NMDAR signaling pathway on regulating learning and memory and synaptic plasticity. Mil. Med. Res. 2016, 3, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Jiang, C.H.; Tong, C.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Lam, S.M.; Wang, D.; Li, R.; Shui, G.; Shi, Y.S.; et al. Activity-dependent PI4P synthesis by PI4KIIIα regulates long-term synaptic potentiation. Cell Rep. 2022, 38, 110452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, A.; Pellegrino, C.; Rama, S.; Dumalska, I.; Salyha, Y.; Ben-Ari, Y.; Medina, I. Opposing role of synaptic and extrasynaptic NMDA receptors in regulation of the extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK) activity in cultured rat hippocampal neurons. J. Physiol. 2006, 572, 789–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-León, C.A.; Sánchez-Garrido Campos, G.; Fernández, M.; Sánchez-López, A.; Medina, J.F.; Márquez-Ruiz, J. Somatodendritic orientation determines tDCS-induced neuromodulation of Purkinje cell activity in awake mice. bioRxiv, 2023; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J.D.; Dominguez-Vargas, A.U.; Rosso, C.; Branscheidt, M.; Sheehy, L.; Quandt, F.; Zamora, S.A.; Fleming, M.K.; Azzollini, V.; Mooney, R.A.; et al. A translational roadmap for transcranial magnetic and direct current stimulation in stroke rehabilitation: Consensus-based core recommendations from the third stroke recovery and rehabilitation roundtable. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair 2024, 38, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Cui, H.; Xiao, X.; Manshaii, F.; Hong, G.; Chen, J. Precision at Deep Brain: Noninvasive Temporal Interference Stimulation. ACS Nano 2025, 19, 39589–39614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molero-Chamizo, A.; Nitsche, M.A.; Gutiérrez Lérida, C.; Salas Sánchez, Á.; Martín Riquel, R.; Andújar Barroso, R.T.; Alameda Bailén, J.R.; García Palomeque, J.C.; Rivera-Urbina, G.N. Standard Non-Personalized Electric Field Modeling of Twenty Typical tDCS Electrode Configurations via the Computational Finite Element Method: Contributions and Limitations of Two Different Approaches. Biology 2021, 10, 1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callejón-Leblic, M.A.; Miranda, P.C. A comprehensive analysis of the impact of head model extent on electric field predictions in transcranial current stimulation. J. Neural Eng. 2021, 18, 046024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markowska, A.; Tarnacka, B. Molecular Changes in the Ischemic Brain as Non-Invasive Brain Stimulation Targets-TMS and tDCS Mechanisms, Therapeutic Challenges, and Combination Therapies. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| “repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation”[Title/Abstract] OR “rTMS”[Title/Abstract] “theta burst stimulation”[Title/Abstract] OR “TBS”[Title/Abstract] ------------------------------------------- “paired associative stimulation”[Title/Abstract] OR “PAS”[Title/Abstract] ------------------------------------------- “transcranial direct current stimulation”[Title/Abstract] OR “tDCS”[Title/Abstract] ------------------------------------------- “transcranial alternating current stimulation”[Title/Abstract] OR “tACS”[Title/Abstract] | AND | “cellular effects”[Title/Abstract] OR “molecular effects”[Title/Abstract] OR “mechanisms”[Title/Abstract] OR “cellular mechanisms”[Title/Abstract] OR “molecular mechanisms”[Title/Abstract] OR “neuroplasticity”[Title/Abstract] OR “gene expression”[Title/Abstract] OR “synaptic plasticity”[Title/Abstract] OR “LTP-like”[Title/Abstract] OR “LTD-like”[Title/Abstract]) | AND | “human”[Title/Abstract] OR “ex vivo”[Title/Abstract] OR “in vivo”[Title/Abstract] OR “animal model”[Title/Abstract] OR “murine”[Title/Abstract] OR “primate”[Title/Abstract] OR “mammalian”[Title/Abstract] OR “cell line”[Title/Abstract] OR “neuron”[Title/Abstract] OR “in vitro”[Title/Abstract] OR “neurodegenerative disease”[Title/Abstract] OR “Alzheimer’s Disease”[Title/Abstract] OR “Parkinson’s Disease”[Title/Abstract] OR “stroke”[Title/Abstract] OR “psychiatric diseases”[Title/Abstract] |

| Authors | Stimulation Technique and Protocol | Parameters/Site of Stimulation | Animal Model/Neural Substrate | N° Groups/Participants | Cellular/Molecular/Genetic Techniques USED | Translation to Human Studies | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baek et al., 2018 [42] | rMS | 0.5/10 Hz, 10 min of stimulation | Mouse N2a cell culture of I/R model injury (OGD/R) | 3 groups: OGD/R + sham, OGD/R+LF (0.5 Hz) and OGD/R+HF (10 Hz) | qRT-PCR, Western blot, ICC | No | OGD/R+LF: ↓ p-ERK and p-AKT, ↓ BAX and caspase-3, ↑ Bcl-2 and Pro-caspase-3, ↓ NMDAR1, CaMKII–CREB OGD/R+HF: ↑ p-ERK and p-AKT, ↑ BAX and caspase-3, ↓ Bcl-2 and Pro-caspase-3, ↑ NMDAR1, CaMKII–CREB, ↑ BDNF, SYN-1 and PSD-95 |

| Feng et al., 2012 [43] | rTMS | 15 Hz, 1000 pulses/d, 3 w, 100% MSO, vertex | Depression model (CUMS) in male SD rats | 84 divided in 7 groups: sham, rTMS, Ven, CUMS, CUMS + rTMS, CUMS+Ven, CUMS + rTMS + Ven | ICC, Western blot, ELISA | No | ↑ BDNF and pERK1/2 after 3 weeks of rTMS and continued to stay at a stable high level 2 weeks later, after the treatments stopped |

| Gao et al., 2010 [44] | rTMS | 20 Hz, 5 s × 10 times, 7 d, right fronto-parietal cortex (bregma) | SD rat models of MCAO-stroke | 30, divided into 3 groups: control, rTMS, sham. | IHC | No | ↓ caspase3, ↑ Bcl-2 and ↑ Bcl-2/Bax ratio in the rTMS group |

| Guo et al., 2017 [45] | rTMS | 10 Hz, 10 times (300 pulses/d), 120% RMT, bregma | male SD rat models of MCAO | 7- and 14-day-treatment groups, divided into sham, MCAO and rTMS groups. | IF, Western blot, qRT-PCR, | No | ↑ BDNF, TrkB, p-AKT and Bcl-2 protein expression, and ↓ Bax expression in hippocampus during rTMS |

| Hwang et al., 2022 [46] | rTMS | 1 Hz single vs. repeated session (20 min/5 d), left hemisphere, 50% MT | male SD rats | 16 rats. Single session: 4 real stim, 4 sham Repeated session (5 d): 4 real stim, 4 sham | mRNA-miRNA microarray analysis | No | + regulation of intracellular transport and synaptic plasticity only with repeated rTMS group. A single session of rTMS primarily induced changes in the early genes. |

| Kim et al., 2024 [47] | rTMS | 1/10 Hz.

| STZ-induced model of AD in human neuroblastoma cell line. Male SD rats’ hippocampi | 15 rats divided into 3 groups: control, sham rTMS on STZ-induced AD and real rTMS on STZ-induced AD | IHC, qRT-PCR, Western blotting | No | ↑ STAT1, STAT3, STAT5, ERK, JNK, Akt, p70S6K, and CREB in cell lines and in AD’s animal model after 10 Hz rTMS ↑ ERK, JNK, Akt, p70S6K in 1 Hz and in 10 Hz rTMS groups at 20 min after stimulation. ↑ CREB only in 10 Hz rTMS after 20 min. Phosphorylation lasts 3 h in 10 Hz and 1 h in 1 Hz rTMS. |

| McNerney et al., 2022 [48] | rTMS | 10 Hz, 10 min/d, 2 times/w, 6 w, bregma | Female 3xTgAD mice and their wild type controls | 103 mice divided into real and sham, 2 weeks- and 6 weeks-stimulation groups | IHC, qRT-PCR, ELISA | No | = BDNF in the wild-type group that received 2 weeks of rTMS and ↑ in the 6-week group. ↑ BDNF expression in the 2-week and 6-week rTMS in 3xTgAD groups |

| Meneses-San Juan et al., 2023 [49] | rTMS | 5 Hz, 5 d × 4 w, 1500 pulses/d, FC and DG stimulation | Female BALB/c mice model of depression (CUMS) | 40 mice, divided in 2 groups: real rTMS and control group (CUMS+FLX) | IHC, IF, ELISA | No | 5 Hz rTMS and FLX reverse the decreased density of the DSs in the FC and DG caused by the CUMS protocol. ↑ SYP in the FC of mice treated with 5 Hz rTMS or FLX. ↑ Histone acetylation and demethylation |

| Wang et al., 2011 [50] | rTMS | 5 Hz, 5 d, 1600 pulses, 50% MSO in rats, 90% RMT in HC in M1, 1200 pulses | Ex vivo male SD rats, HC | 12 rats and 8 HC, divided into 2 groups: real vs. sham. | IHC, Western blot | Yes | ↑ BDNF, PLC-γ1, shc/N-shc, NMDAR subunits, PSD-95, ERK2, PI3K, Akt in brain slices of rat’s PFC and in lymphocytes |

| Wang et al., 2014 [51] | rTMS | 15 Hz, 15 trains of 60 pulses, 100% MSO, 7 d, vertex | Depression model (CUMS) in male SD rats | 36 rats, divided in 4 groups: sham, sham+rTMS, CUMS, CUMS+rTMS | Western blotting, ICC | No | ↑ CB1R, BDNF and Bcl-2/Bax expression levels in the hippocampus after rTMS ↑ CB1R, abolished after administration of a CB1R antagonist |

| Weiler et al., 2023 [52] | rTMS (1 Hz), iTBS | 15% MSO. rTMs and iTBS: 5 blocks, 600 pulses, repeated at 15 min intervals. | Ex vivo and in vivo male Long–Evans rats. In vitro hippocampal neurons of SD rats | 12 Long–Evans rats and 16 SD rats | microarray-based gene expression | No | - In the ex vivo and in vivo Long–Evans model: ↑ Ptk2b, Slc6a13, ↑ Slc5a7, ↑ Ryr2, Chrna5, Grin3a, Glun3a, Arc, Cnp. - In vitro SD rat model: ↑ Gabbr1,2 and Gabra4; ↑ Grik1,4; ↑ Grm3–7. |

| Authors | Stimulation Technique and Protocol | Parameters/Site of Stimulation | Animal Model/Neural Substrate | N° Groups/Participants | Cellular/Molecular/Genetic Techniques Used | Translation to Human Studies | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Battaglia et al., 2007 [53] | TBS, HF-rTMS PAS | AD patients:

| AD patients and double transgenic mice (APP/PS1) | 10 AD patients; transgenic mice compared with WT | IHC, Western blot | Yes | No increase of MEP amplitude of AD patients after PAS ↓ tyrosine-phosphorylated NR2A/NR2B in APP/PS1 transgenic mice ↑ NR2A subunit only in APP/PS1 prefrontal cortex = PSD-95 in the three cortical areas of APP/PS1 mice |

| Gandolfi et al., 2017 [54] | TBS | 8 bursts of 10 pulses at 100 Hz repeated every 250 ms | Cerebellar slices of Wistar rats | 4 groups: controls, 15 min and 120 min from stim, NMDAR antagonist | In situ hybridization, IHC, IF | No | ↑ P-CREB at 15 min and 120 min after TBS. ↑ c-Fos only at 120 min after TBS. No differences in P-CREB/c-Fos in the presence of an NMDAR antagonist |

| Hu et al., 2023 [55] | iTBS | 10 bursts, 600 pulses, 28 d, 26% MSO | Cerebral I/R injured model (MCAO) in SD rats | 4 groups: sham (n = 16), I/R 24 h (n = 19), I/R 28 d (n = 19), I/R + iTBS 28 d (n = 19) | IF, qRT-PCR, ELISA, Western blot, RNA transcriptome sequence analysis | No | ↑ GAP-43, MMP9. ↓ GFAP, Iba-1 ↓ CD86, IL-1b, TNF-a; ↑ CD206, IL-10. ↓ CytC, caspase-3, ↑ Bcl-2. ↓ Bax, caspase-3, CytC, caspase-9 after 28 days of iTBS. |

| Ismail et al., 2024 [56] | iTBS | 300 pulses, 25, 50, 75 and 100% MSO | N2A mouse neuroblastoma cells | 12-well plate of 104 cells divided into 5 groups: after 0.5 h, 3 h, 6 h, 12 h and 24 h | Immunoblotting, ICC | No | ↑ NMDAR1, GABBR2, mGluR, TrkB, GAP-43, synapsin-1, BDNF and β-tubulin III at 0.5 h post-iTBS |

| Labedi et al., 2014 [57] | iTBS | 5 blocks, 600 pulses/15 min, 23–25% MSO | male SD rats | 16 rats, divided in 4 groups: sham-iTBS, real iTBS, iTBS low dose of ketamine or iTBS high dose of ketamine. | IHC | No | ↓GAD67, CB and PV ketamine largely prevented the loss of PV and GAD67 expression at both low and high dose |

| Ljubisavljevic et al., 2015 [58] | iTBS, cTBS rTMS (1/5 Hz) | 30% MSO, 1 t/d, 4 blocks, 2400 pulse/d | stroke model (MCAO) of male Wistar rats | 149 rats divided in: 1 Hz, 5 Hz, iTBS, cTBS, sham | IHC, qRT-PCR | No | ↑ BDNF in 5 Hz rTMS, cTBS and iTBS. ↑ Creb1, Gria1–4, Grin2a–2c, Gabbr1, ↑Gadd45b, Junb, Gls, Bai1. c-Fos and Jun ↑ only after iTBS. ↑ Plat (tPA gene) after cTBS |

| Stekic et al., 2022 [59] | iTBS | 33% MSO, 15 sessions/2 stim per d/600 pulses, frontal | male Wistar rats of AD model induced by TMT intoxication | 54 rats divided into 4 groups:

| IHC, Western blot | No | ↑ P-ERK 1/2 and PI3K in iTBS group. Restored levels of mTOR and p-Akt/compared to TMT group |

| Thomson et al., 2020 [60] | iTBS, cTBS | 600 pulses, 100% MSO | in vitro SH-SY5Y human neuron model | 3 conditions:

| qRT-PCR, IF | No | ↑ NTRK2, Bcl2 and MAPK9 after 24 h of iTBS. No effects of cTBS on gene expression |

| Wu et al., 2024 [61] | iTBS | 20 trains, 600 pulses, 14 d, 30% MSO or 80% RMT | male SD rats | 97 rats divided into 2 groups: real and sham | IHC, microdyalisis | No | ↑ c-Fos. Normalized theta power significantly higher in real iTBS group. ↓ GABA, ↑ Glu, ↓ GABA/Glu ratio in real iTBs group |

| Authors | Stimulation Technique and Protocol | Parameters/Site of Stimulation | Animal Model/Neural Substrate | N° Groups/Participants | Cellular/Molecular/Genetic Techniques Used | Translation to Human Studies | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agrawal et al., 2024 [62] | atDCS | Parietal cortex, 20 min, 5 d, 250 μA | Male SD rats | 6 rats | mRNA sequencing and Metabolomic Analysis | No | ↑ adenosine, G6P, 3-BAIBA, ↓ sphingosine. ↑ glycolysis and mitochondrial function by the TCA cycle. ↓ Ca2+-related signal. |

| Cancel et al., 2022 [63] | DCS | 0.1–1 mA for 10 min | In vitro HA and mouse brain EC | A monolayer of 3 × 104 HA/cm2 and 6 × 104 EC/cm2 | qRT-PCR and Western blot immediately and 1 h after stim | No | ↑ NOS3 and VEGFR1 (modulate permeability of BBB ↑ c-FOS and BDNF in astrocytes |

| Holmes et al., 2016 [64] | atDCS | sham, 250- 500- 2000 μA 20 min, sagittal suture, 2.5 mm caudal bregma | Male SD rats | 7–8 rats × group stim condition | NGS whole transcriptome RNA-sequencing analysis | No | ↑ signaling pathways related to Ca2+ ion binding, transmembrane/signal peptide and NLRP3- IL-1β pathway. ↑ Ras signaling pathway |

| Kim et al., 2017 [65] | atDCS | 250 μA, 20 min, 7 d in the right sensorimotor cortex | Male SD rats | 19 rats, divided into 3 groups: intact control group(n = 5), sham-operated group (n = 7), real stim group (n = 7) | qRT-PCR after 6 h of stim | No | ↑ NMDAR and BDNF, CREB, CaMKII, and synapsin I. ↑ c-Fos and Arc. |

| Longo et al., 2022 [66] | tDCS delivered with 2 epicranial electrodes | 72 h post PT stroke on M1, 3 sessions of 250 μA, 20 min,3 d | C57BL/6 male mice | Not described. Divided into 2 groups: real or sham tDCS | Western immunoblotting, qRT-PCR, ELISA 24 h after stim | No | ↑ ERK1/2-CREB, CaMKII, BDNF. ↑ PSD-95 |

| Magri et al., 2021 [67] | atDCS with unilateral epicranial electrode | HP (3 stim, 20 min, 3 consecutive days), PFC (6 stim, 15 min, 3 d × 2 w) | 3xTg-AD mouse vs. age-matched WT mice | 14 real vs. 9 sham AD mouse; 7 real vs. 9 sham control WT mice | mRNA sequencing and blood whole transcriptome analysis | No | tDCS is able to modulate the gene expression of peripheral tissues, such as blood, and it suggests that blood gene expression profiles could be used as biomarkers of synaptic plasticity |

| Podda et al., 2016 [68] | atDCS with unilateral epicranial electrode | left hippocampi,1 mm left and 1 mm posterior to bregma, 350 μA, 20 min | Male C57 BL/6 mice | 18 mice (n = 9 active stim, n = 9 sham control) | qRT-PCR and ELISA, 24 h after stim Western blot 2 h after stim | No | ↑ BDNF and pCREB |

| Sánchez-León et al., 2021 [69] | Anodal or cathodal tDCS, tACS | tDCS: Right-S1, 20 min, 200 μA for cathodal, 150 μA for anodal. tACS: 2,20,200 μA at 1 Hz | adult male C57 mice | 10 mice, divided into 2 groups: real and sham stim | IHC | No | ↑ GAD65–67 and GABA level imbalance after cathodal stimulation but no changes after anodal stimulation. ↑ SEP amplitude during anodal stimulation and ↓ during cathodal stimulation |

| Sun et al., 2016 [70] | Cathodal DCS | In vitro: 300 or 400 μA, 10 or 25 min. In vivo: 1 mA, 25 min | In vitro brain slices of male C57BL/6 mice, human cortex in vivo (surgical removal of epileptogenic zone) | Not described | Immunoblot at 0, 15, 30, 60 min in vitro after stim | Yes | mGluR5-mTOR signaling as a novel pathway that neither GABAR nor NMDAR blockade abolished DCS-LTD |

| Walter et al., 2022 [71] | Anodal or cathodal tDCS | PT, bregma, 2 sessions: 15 min, 250 or 500 μA, 5 d | male C57BL/6JRj mice | 62 divided into 2 groups: real or sham stim | IHC | No | ctDCS: ↑ functional recovery, neurogenesis. ↓ microglial activation, and CD16/32. atDCS ↑ neurogenesis. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sveva, V.; Mancuso, M.; Cruciani, A.; Casula, E.P.; Leodori, G.; Selvaggi, S.A.; Bologna, M.; Di Lazzaro, V.; Latorre, A.; Rocchi, L. Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms of Non-Invasive Brain Stimulation Techniques: A Systematic Review on the Implications for the Treatment of Neurological Disorders. Cells 2025, 14, 1996. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14241996

Sveva V, Mancuso M, Cruciani A, Casula EP, Leodori G, Selvaggi SA, Bologna M, Di Lazzaro V, Latorre A, Rocchi L. Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms of Non-Invasive Brain Stimulation Techniques: A Systematic Review on the Implications for the Treatment of Neurological Disorders. Cells. 2025; 14(24):1996. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14241996

Chicago/Turabian StyleSveva, Valerio, Marco Mancuso, Alessandro Cruciani, Elias Paolo Casula, Giorgio Leodori, Silvia Antonella Selvaggi, Matteo Bologna, Vincenzo Di Lazzaro, Anna Latorre, and Lorenzo Rocchi. 2025. "Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms of Non-Invasive Brain Stimulation Techniques: A Systematic Review on the Implications for the Treatment of Neurological Disorders" Cells 14, no. 24: 1996. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14241996

APA StyleSveva, V., Mancuso, M., Cruciani, A., Casula, E. P., Leodori, G., Selvaggi, S. A., Bologna, M., Di Lazzaro, V., Latorre, A., & Rocchi, L. (2025). Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms of Non-Invasive Brain Stimulation Techniques: A Systematic Review on the Implications for the Treatment of Neurological Disorders. Cells, 14(24), 1996. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14241996