Molecular Mechanisms of Atrial Fibrillation Recurrence After Successful Catheter Ablation

Abstract

1. Introduction

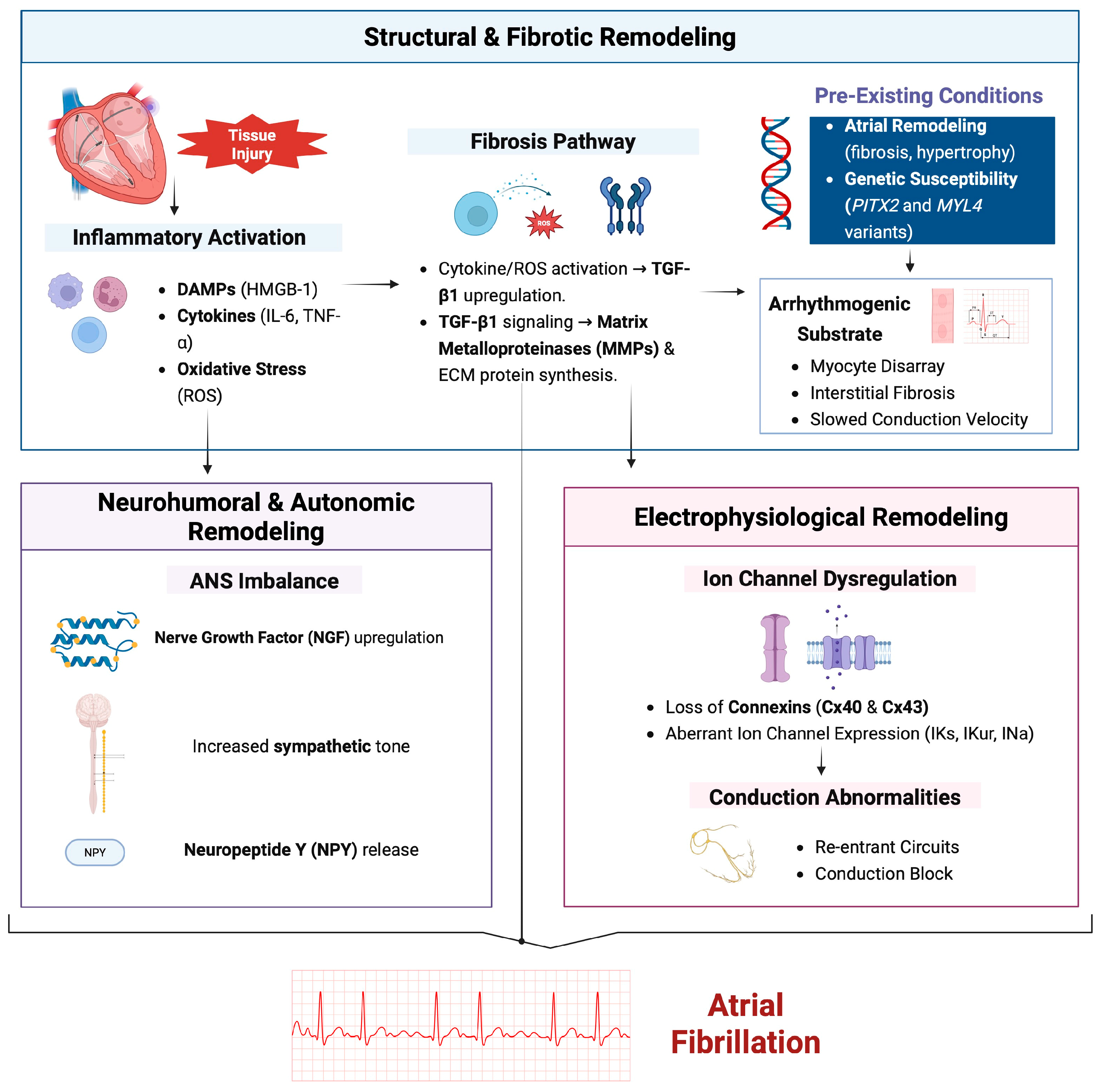

2. Structural Remodeling

2.1. Fibrosis and Extracellular Matrix (ECM) Alterations

2.2. Role of Transforming Growth Factor-Beta (TGF-β) and Matrix Metalloproteinases (MMPs)

2.3. Cellular Hypertrophy and Myocyte Disarray

2.4. Impact on Conduction Velocity and Arrhythmogenic Substrate Formation

2.5. Ion-Channel Dysregulation

2.6. Electrophysiological and Structural Determinants

2.7. Role of Connexins and Gap Junctions

3. Inflammatory Pathways

4. Autonomic Nervous System (ANS) Imbalance

5. Genetic and Epigenetic Factors

6. Neurohumoral Factors and Circulating Biomarkers

7. Emerging Exposures

8. Ablation Energy Sources and Their Biological Footprint

9. Therapeutic Implications

9.1. Colchicine

9.2. Corticosteroids

9.3. Methotrexate

9.4. Cardiac Drugs with Pleiotropic Effects

9.5. Statins and PCSK9 Inhibitors

9.6. Metformin

9.7. Sodium–Glucose Cotransporter 2 Inhibitors

9.8. Glucagon-like-Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists

9.9. n-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids (PUFAs)

10. Future Therapeutic Targets

11. Limitations of Current Research and Future Directions

12. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AF | Atrial fibrillation |

| AAD | Anti-arrhythmic drug |

| ACEi | Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor |

| ADMA | Asymmetric dimethylarginine |

| AMPK | AMP-activated protein kinase |

| ANS | Autonomic nervous system |

| ANF | Atrial natriuretic factor |

| AUROC | Area under the receiver operating characteristic |

| BNP | Brain natriuretic peptide |

| CA | Catheter ablation |

| CFAE | Complex fractionated atrial electrogram |

| CpG | Cytosine–phosphate–guanine |

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| Cx | Connexin |

| DAMPs | Damage-associated molecular patterns |

| DLS | Difference between the longest and shortest P-A0 interval |

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

| ECV | Electrical cardioversion |

| GWAS | Genome-wide association study |

| GDF-15 | Growth differentiation factor-15 |

| GI | Gastrointestinal |

| HDAC | Histone deacetylase |

| HCM | Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy |

| HMGB-1 | High-mobility group box-1 |

| HR | Hazard ratio |

| hs-CRP | High-sensitivity C-reactive protein |

| ICa-L | L-type calcium current |

| ICTP | Carboxylterminal telopeptide of collagen type I |

| IL | Interleukin |

| INa | Sodium current |

| IKur | Ultrarapid delayed rectifier potassium current |

| IKs | Slow delayed rectifier potassium current |

| IV | Intravenous |

| LA | Left atrium / Left atrial |

| LAA | Left atrial appendage |

| LACV | Left atrial conduction velocity |

| LGE | Late gadolinium enhancement |

| LVAs | Low-voltage areas |

| MAPK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| miRNA | MicroRNA |

| MMP | Matrix metalloproteinase |

| MNPs | Microplastics/nanoplastics |

| MPO | Myeloperoxidase |

| mtDNA | Mitochondrial DNA |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor kappa-B |

| NGF | Nerve growth factor |

| NO | Nitric oxide |

| NOS | Nitric oxide synthase |

| NPY | Neuropeptide Y |

| NT-proBNP | N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide |

| OR | Odds ratio |

| PCSK9 | Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 |

| PITX2 | Paired-like homeodomain transcription factor 2 |

| PMNs | Polymorphonuclear neutrophils |

| POAF | Postoperative atrial fibrillation |

| PsAF | Persistent atrial fibrillation |

| PUFAs | Polyunsaturated fatty acids |

| PVI | Pulmonary vein isolation |

| PW-TDI | Pulsed-wave tissue Doppler imaging |

| RAAS | Renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system |

| RECK | Reversion-inducing cysteine-rich protein with Kazal motifs |

| RFCA | Radiofrequency catheter ablation |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| RR | Relative risk |

| sST2 | Soluble suppression of tumorigenicity-2 |

| SNP | Single-nucleotide polymorphism |

| SP | Substance P |

| SV | Sacubitril–valsartan |

| TASK1 | Twik-related acid-sensitive potassium channel 1 |

| TGF-β1 | Transforming growth factor-beta 1 |

| TIMP | Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase |

| TLR | Toll-like receptor |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor-alpha |

| TTN | Titin |

| TTNtv | Titin-truncating variant |

References

- Chugh, S.S.; Havmoeller, R.; Narayanan, K.; Singh, D.; Rienstra, M.; Benjamin, E.J.; Gillum, R.F.; Kim, Y.-H.; McAnulty, J.H.; Zheng, Z.-J.; et al. Worldwide Epidemiology of Atrial Fibrillation: A Global Burden of Disease 2010 Study. Circulation 2014, 129, 837–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krijthe, B.P.; Kunst, A.; Benjamin, E.J.; Lip, G.Y.H.; Franco, O.H.; Hofman, A.; Witteman, J.C.M.; Stricker, B.H.; Heeringa, J. Projections on the Number of Individuals with Atrial Fibrillation in the European Union, from 2000 to 2060. Eur. Heart J. 2013, 34, 2746–2751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, E.J.; Wolf, P.A.; D’Agostino, R.B.; Silbershatz, H.; Kannel, W.B.; Levy, D. Impact of Atrial Fibrillation on the Risk of Death: The Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 1998, 98, 946–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vermond, R.A.; Geelhoed, B.; Verweij, N.; Tieleman, R.G.; Van der Harst, P.; Hillege, H.L.; Van Gilst, W.H.; Van Gelder, I.C.; Rienstra, M. Incidence of Atrial Fibrillation and Relationship With Cardiovascular Events, Heart Failure, and Mortality: A Community-Based Study From the Netherlands. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2015, 66, 1000–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.J.; Wolf, P.A.; Kelly-Hayes, M.; Beiser, A.S.; Kase, C.S.; Benjamin, E.J.; D’Agostino, R.B. Stroke Severity in Atrial Fibrillation. The Framingham Study. Stroke 1996, 27, 1760–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliman, E.Z.; Safford, M.M.; Muntner, P.; Khodneva, Y.; Dawood, F.Z.; Zakai, N.A.; Thacker, E.L.; Judd, S.; Howard, V.J.; Howard, G.; et al. Atrial Fibrillation and the Risk of Myocardial Infarction. JAMA Intern. Med. 2014, 174, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walters, T.E.; Nisbet, A.; Morris, G.M.; Tan, G.; Mearns, M.; Teo, E.; Lewis, N.; Ng, A.; Gould, P.; Lee, G.; et al. Progression of Atrial Remodeling in Patients with High-Burden Atrial Fibrillation: Implications for Early Ablative Intervention. Heart Rhythm 2016, 13, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaïs, P.; Haïssaguerre, M.; Shah, D.C.; Chouairi, S.; Gencel, L.; Hocini, M.; Clémenty, J. A Focal Source of Atrial Fibrillation Treated by Discrete Radiofrequency Ablation. Circulation 1997, 95, 572–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calkins, H.; Kuck, K.H.; Cappato, R.; Brugada, J.; Camm, A.J.; Chen, S.-A.; Crijns, H.J.G.; Damiano, R.J.; Davies, D.W.; DiMarco, J.; et al. 2012 HRS/EHRA/ECAS Expert Consensus Statement on Catheter and Surgical Ablation of Atrial Fibrillation: Recommendations for Patient Selection, Procedural Techniques, Patient Management and Follow-up, Definitions, Endpoints, and Research Trial Design. Eur. Eur. Pacing Arrhythm. Card. Electrophysiol. J. Work. Groups Card. Pacing Arrhythm. Card. Cell. Electrophysiol. Eur. Soc. Cardiol. 2012, 14, 528–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calkins, H.; Hindricks, G.; Cappato, R.; Kim, Y.-H.; Saad, E.B.; Aguinaga, L.; Akar, J.G.; Badhwar, V.; Brugada, J.; Camm, J.; et al. 2017 HRS/EHRA/ECAS/APHRS/SOLAECE Expert Consensus Statement on Catheter and Surgical Ablation of Atrial Fibrillation. Heart Rhythm 2017, 14, e275–e444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- January, C.T.; Wann, L.S.; Alpert, J.S.; Calkins, H.; Cigarroa, J.E.; Cleveland, J.C.; Conti, J.B.; Ellinor, P.T.; Ezekowitz, M.D.; Field, M.E.; et al. 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS Guideline for the Management of Patients with Atrial Fibrillation: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation 2014, 130, 2071–2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchhof, P.; Benussi, S.; Kotecha, D.; Ahlsson, A.; Atar, D.; Casadei, B.; Castella, M.; Diener, H.-C.; Heidbuchel, H.; Hendriks, J.; et al. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the Management of Atrial Fibrillation Developed in Collaboration with EACTS. Eur. Heart J. 2016, 37, 1609–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packer, D.L.; Mark, D.B.; Robb, R.A.; Monahan, K.H.; Bahnson, T.D.; Poole, J.E.; Noseworthy, P.A.; Rosenberg, Y.D.; Jeffries, N.; Mitchell, L.B.; et al. Effect of Catheter Ablation vs Antiarrhythmic Drug Therapy on Mortality, Stroke, Bleeding, and Cardiac Arrest Among Patients With Atrial Fibrillation: The CABANA Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2019, 321, 1261–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuck, K.-H.; Brugada, J.; Fürnkranz, A.; Metzner, A.; Ouyang, F.; Chun, K.R.J.; Elvan, A.; Arentz, T.; Bestehorn, K.; Pocock, S.J.; et al. Cryoballoon or Radiofrequency Ablation for Paroxysmal Atrial Fibrillation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 374, 2235–2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaïs, P.; Cauchemez, B.; Macle, L.; Daoud, E.; Khairy, P.; Subbiah, R.; Hocini, M.; Extramiana, F.; Sacher, F.; Bordachar, P.; et al. Catheter Ablation versus Antiarrhythmic Drugs for Atrial Fibrillation: The A4 Study. Circulation 2008, 118, 2498–2505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.; Sheppard, R. Fibrosis in Heart Disease: Understanding the Role of Transforming Growth Factor-Beta in Cardiomyopathy, Valvular Disease and Arrhythmia. Immunology 2006, 118, 10–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verheule, S.; Sato, T.; Everett, T.; Engle, S.K.; Otten, D.; Rubart-von der Lohe, M.; Nakajima, H.O.; Nakajima, H.; Field, L.J.; Olgin, J.E. Increased Vulnerability to Atrial Fibrillation in Transgenic Mice with Selective Atrial Fibrosis Caused by Overexpression of TGF-Beta1. Circ. Res. 2004, 94, 1458–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmutula, D.; Marcus, G.M.; Wilson, E.E.; Ding, C.-H.; Xiao, Y.; Paquet, A.C.; Barbeau, R.; Barczak, A.J.; Erle, D.J.; Olgin, J.E. Molecular Basis of Selective Atrial Fibrosis Due to Overexpression of Transforming Growth Factor-Β1. Cardiovasc. Res. 2013, 99, 769–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Wang, Y.; Chen, W.; Yin, Y.; Qin, M. Role of Serum TGF-Β1 Level in Atrial Fibrosis and Outcome after Catheter Ablation for Paroxysmal Atrial Fibrillation. Medicine 2017, 96, e9210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Jian, Z.; Yang, Z.Y.; Chen, L.; Wang, X.F.; Ma, R.Y.; Xiao, Y.B. Increased Expression of Connective Tissue Growth Factor and Transforming Growth Factor-Beta-1 in Atrial Myocardium of Patients with Chronic Atrial Fibrillation. Cardiology 2013, 124, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.; Lei, H.; Qin, S.; Ma, K.; Wang, X. TGF-Beta1 Expression and Atrial Myocardium Fibrosis Increase in Atrial Fibrillation Secondary to Rheumatic Heart Disease. Clin. Cardiol. 2010, 33, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.K.; Park, J.H.; Kim, J.Y.; Choi, J.I.; Joung, B.; Lee, M.-H.; Kim, S.S.; Kim, Y.-H.; Pak, H.-N. High Plasma Concentrations of Transforming Growth Factor-β and Tissue Inhibitor of Metalloproteinase-1: Potential Non-Invasive Predictors for Electroanatomical Remodeling of Atrium in Patients with Non-Valvular Atrial Fibrillation. Circ. J. Off. J. Jpn. Circ. Soc. 2011, 75, 557–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- On, Y.K.; Jeon, E.-S.; Lee, S.Y.; Shin, D.-H.; Choi, J.-O.; Sung, J.; Kim, J.S.; Sung, K.; Park, P. Plasma Transforming Growth Factor Beta1 as a Biochemical Marker to Predict the Persistence of Atrial Fibrillation after the Surgical Maze Procedure. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2009, 137, 1515–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rundhaug, J.E. Matrix Metalloproteinases and Angiogenesis. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2005, 9, 267–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pistol, G.; Matache, C.; Calugaru, A.; Stavaru, C.; Tanaseanu, S.; Ionescu, R.; Dumitrache, S.; Stefanescu, M. Roles of CD147 on T Lymphocytes Activation and MMP-9 Secretion in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2007, 11, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moshal, K.S.; Tyagi, N.; Moss, V.; Henderson, B.; Steed, M.; Ovechkin, A.; Aru, G.M.; Tyagi, S.C. Early Induction of Matrix Metalloproteinase-9 Transduces Signaling in Human Heart End Stage Failure. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2005, 9, 704–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Sun, B. Toll-like Receptor 4 in Atherosclerosis. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2007, 11, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jinga, D.C.; Blidaru, A.; Condrea, I.; Ardeleanu, C.; Dragomir, C.; Szegli, G.; Stefanescu, M.; Matache, C. MMP-9 and MMP-2 Gelatinases and TIMP-1 and TIMP-2 Inhibitors in Breast Cancer: Correlations with Prognostic Factors. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2006, 10, 499–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anghelina, M.; Moldovan, L.; Zabuawala, T.; Ostrowski, M.C.; Moldovan, N.I. A Subpopulation of Peritoneal Macrophages Form Capillarylike Lumens and Branching Patterns in Vitro. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2006, 10, 708–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spinale, F.G. Matrix Metalloproteinases: Regulation and Dysregulation in the Failing Heart. Circ. Res. 2002, 90, 520–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spinale, F.G.; Coker, M.L.; Bond, B.R.; Zellner, J.L. Myocardial Matrix Degradation and Metalloproteinase Activation in the Failing Heart: A Potential Therapeutic Target. Cardiovasc. Res. 2000, 46, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.; Takahashi, R.; Kondo, S.; Mizoguchi, A.; Adachi, E.; Sasahara, R.M.; Nishimura, S.; Imamura, Y.; Kitayama, H.; Alexander, D.B.; et al. The Membrane-Anchored MMP Inhibitor RECK Is a Key Regulator of Extracellular Matrix Integrity and Angiogenesis. Cell 2001, 107, 789–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, M.P.; Sukhova, G.K.; Kisiel, W.; Foster, D.; Kehry, M.R.; Libby, P.; Schönbeck, U. Tissue Factor Pathway Inhibitor-2 Is a Novel Inhibitor of Matrix Metalloproteinases with Implications for Atherosclerosis. J. Clin. Investig. 2001, 107, 1117–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mott, J.D.; Thomas, C.L.; Rosenbach, M.T.; Takahara, K.; Greenspan, D.S.; Banda, M.J. Post-Translational Proteolytic Processing of Procollagen C-Terminal Proteinase Enhancer Releases a Metalloproteinase Inhibitor. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 1384–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welm, B.; Mott, J.; Werb, Z. Developmental Biology: Vasculogenesis Is a Wreck without RECK. Curr. Biol. CB 2002, 12, R209–R211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noda, M.; Oh, J.; Takahashi, R.; Kondo, S.; Kitayama, H.; Takahashi, C. RECK: A Novel Suppressor of Malignancy Linking Oncogenic Signaling to Extracellular Matrix Remodeling. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2003, 22, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Echizenya, M.; Kondo, S.; Takahashi, R.; Oh, J.; Kawashima, S.; Kitayama, H.; Takahashi, C.; Noda, M. The Membrane-Anchored MMP-Regulator RECK Is a Target of Myogenic Regulatory Factors. Oncogene 2005, 24, 5850–5857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.-H.; Hu, Y.-F.; Chou, C.-Y.; Lin, Y.-J.; Chang, S.-L.; Lo, L.-W.; Tuan, T.-C.; Li, C.-H.; Chao, T.-F.; Chung, F.-P.; et al. Transforming Growth Factor-Β1 Level and Outcome after Catheter Ablation for Nonparoxysmal Atrial Fibrillation. Heart Rhythm 2013, 10, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Wang, S.; Cheng, M.; Peng, B.; Liang, J.; Huang, H.; Jiang, X.; Zhang, L.; Yang, B.; Cha, Y.; et al. The Serum Matrix Metalloproteinase-9 Level Is an Independent Predictor of Recurrence after Ablation of Persistent Atrial Fibrillation. Clinics 2016, 71, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, F.; Bänsch, D.; Ernst, S.; Schaumann, A.; Hachiya, H.; Chen, M.; Chun, J.; Falk, P.; Khanedani, A.; Antz, M.; et al. Complete Isolation of Left Atrium Surrounding the Pulmonary Veins: New Insights from the Double-Lasso Technique in Paroxysmal Atrial Fibrillation. Circulation 2004, 110, 2090–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.-J.; Tai, C.-T.; Kao, T.; Chang, S.-L.; Lo, L.-W.; Tuan, T.-C.; Udyavar, A.R.; Wongcharoen, W.; Hu, Y.-F.; Tso, H.-W.; et al. Spatiotemporal Organization of the Left Atrial Substrate After Circumferential Pulmonary Vein Isolation of Atrial Fibrillation. Circ. Arrhythm. Electrophysiol. 2009, 2, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okumura, Y.; Watanabe, I.; Nakai, T.; Ohkubo, K.; Kofune, T.; Kofune, M.; Nagashima, K.; Mano, H.; Sonoda, K.; Kasamaki, Y.; et al. Impact of Biomarkers of Inflammation and Extracellular Matrix Turnover on the Outcome of Atrial Fibrillation Ablation: Importance of Matrix Metalloproteinase-2 as a Predictor of Atrial Fibrillation Recurrence. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 2011, 22, 987–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penela, D.; Sorgente, A.; Cappato, R. State-of-the-Art Treatments for Atrial Fibrillation in Patients with Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 3025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castagno, D.; Di Donna, P.; Olivotto, I.; Frontera, A.; Calò, L.; Scaglione, M.; Arretini, A.; Anselmino, M.; Giustetto, C.; De Ferrari, G.M.; et al. Transcatheter Ablation for Atrial Fibrillation in Patients with Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: Long-term Results and Clinical Outcomes. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 2021, 32, 657–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, H.S.K.; Wang, N.; Wong, S.; Phan, S.; Liao, J.; Kumar, N.; Qian, P.; Yan, T.D.; Phan, K. Catheter Ablation for Atrial Fibrillation in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Patients: A Systematic Review. J. Interv. Card. Electrophysiol. 2015, 44, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.-S.; Shen, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Lin, G.; Lu, Y.-H.; Chen, B.-T.; Shi, L.-S.; Huang, J.-F.; Lu, H.-H. Outcomes of Catheter Ablation of Atrial Fibrillation in Patients with Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Europace 2016, 18, 508–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Providencia, R.; Elliott, P.; Patel, K.; McCready, J.; Babu, G.; Srinivasan, N.; Bronis, K.; Papageorgiou, N.; Chow, A.; Rowland, E.; et al. Catheter Ablation for Atrial Fibrillation in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Heart 2016, 102, 1533–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antzelevitch, C.; Burashnikov, A. Overview of Basic Mechanisms of Cardiac Arrhythmia. Card. Electrophysiol. Clin. 2011, 3, 23–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frontera, A.; Villella, F.; Cristiano, E.; Comi, F.; Latini, A.; Ceriotti, C.; Galimberti, P.; Zachariah, D.; Pinna, G.; Taormina, A.; et al. The Functional Substrate in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation Is Predictive of Recurrences after Catheter Ablation. Heart Rhythm 2024, 22, 1401–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lukito, A.A.; Raffaello, W.M.; Pranata, R. Slow Left Atrial Conduction Velocity in the Anterior Wall Calculated by Electroanatomic Mapping Predicts Atrial Fibrillation Recurrence after Catheter Ablation-Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Arrhythmia 2024, 40, 1077–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDowell, K.S.; Vadakkumpadan, F.; Blake, R.; Blauer, J.; Plank, G.; MacLeod, R.S.; Trayanova, N.A. Mechanistic Inquiry into the Role of Tissue Remodeling in Fibrotic Lesions in Human Atrial Fibrillation. Biophys. J. 2013, 104, 2764–2773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahnkopf, C.; Badger, T.J.; Burgon, N.S.; Daccarett, M.; Haslam, T.S.; Badger, C.T.; McGann, C.J.; Akoum, N.; Kholmovski, E.; Macleod, R.S.; et al. Evaluation of the Left Atrial Substrate in Patients with Lone Atrial Fibrillation Using Delayed-Enhanced MRI: Implications for Disease Progression and Response to Catheter Ablation. Heart Rhythm 2010, 7, 1475–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okubo, Y.; Oguri, N.; Sakai, T.; Uotani, Y.; Furutani, M.; Miyamoto, S.; Miyauchi, S.; Okamura, S.; Tokuyama, T.; Nakano, Y. Conduction Velocity Mapping in Atrial Fibrillation Using Omnipolar Technology. Pacing Clin. Electrophysiol. 2024, 47, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, D.; Guan, X.; Liu, X.; Liu, L.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, J. Slow Conduction Velocity Predicts Atrial Fibrillation Recurrence after Radiofrequency Ablation. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 2024, 35, 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukumoto, K.; Habibi, M.; Ipek, E.G.; Zahid, S.; Khurram, I.M.; Zimmerman, S.L.; Zipunnikov, V.; Spragg, D.; Ashikaga, H.; Trayanova, N.; et al. Association of Left Atrial Local Conduction Velocity With Late Gadolinium Enhancement on Cardiac Magnetic Resonance in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation. Circ. Arrhythm. Electrophysiol. 2016, 9, e002897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGann, C.; Akoum, N.; Patel, A.; Kholmovski, E.; Revelo, P.; Damal, K.; Wilson, B.; Cates, J.; Harrison, A.; Ranjan, R.; et al. Atrial Fibrillation Ablation Outcome Is Predicted by Left Atrial Remodeling on MRI. Circ. Arrhythm. Electrophysiol. 2014, 7, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, Y.; Shao, Y.; Li, S.; Liu, T. Research Progress of Low-Voltage Areas Associated with Atrial Fibrillation. Rev. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 24, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voigt, N.; Dobrev, D. Ion Channel Remodelling in Atrial Fibrillation. Eur. Cardiol. Rev. 2011, 7, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinov, B.; Knopp, H.; Löbe, S.; Nedios, S.; Bode, K.; Schönbauer, R.; Sommer, P.; Bollmann, A.; Arya, A.; Hindricks, G. Patterns of Left Atrial Activation and Evaluation of Atrial Dyssynchrony in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation and Normal Controls: Factors beyond the Left Atrial Dimensions. Heart Rhythm 2016, 13, 1829–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löbe, S.; Knopp, H.; Le, T.-V.; Nedios, S.; Seewöster, T.; Bode, K.; Sommer, P.; Bollmann, A.; Hindricks, G.; Dinov, B. Left Atrial Asynchrony Measured by Pulsed-Wave Tissue Doppler Is Associated With Abnormal Atrial Voltage and Recurrences of Atrial Fibrillation After Catheter Ablation. JACC Clin. Electrophysiol. 2018, 4, 1640–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- den Uijl, D.W.; Gawrysiak, M.; Tops, L.F.; Trines, S.A.; Zeppenfeld, K.; Schalij, M.J.; Bax, J.J.; Delgado, V. Prognostic Value of Total Atrial Conduction Time Estimated with Tissue Doppler Imaging to Predict the Recurrence of Atrial Fibrillation after Radiofrequency Catheter Ablation. EP Europace 2011, 13, 1533–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.-H.; Yang, Y.-Q. Atrial Fibrillation: Focus on Myocardial Connexins and Gap Junctions. Biology 2022, 11, 489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaldoupi, S.-M.; Loh, P.; Hauer, R.N.W.; de Bakker, J.M.T.; van Rijen, H.V.M. The Role of Connexin40 in Atrial Fibrillation. Cardiovasc. Res. 2009, 84, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polontchouk, L.; Haefliger, J.A.; Ebelt, B.; Schaefer, T.; Stuhlmann, D.; Mehlhorn, U.; Kuhn-Regnier, F.; De Vivie, E.R.; Dhein, S. Effects of Chronic Atrial Fibrillation on Gap Junction Distribution in Human and Rat Atria. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2001, 38, 883–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostin, S.; Klein, G.; Szalay, Z.; Hein, S.; Bauer, E.P.; Schaper, J. Structural Correlate of Atrial Fibrillation in Human Patients. Cardiovasc. Res. 2002, 54, 361–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wetzel, U.; Boldt, A.; Lauschke, J.; Weigl, J.; Schirdewahn, P.; Dorszewski, A.; Doll, N.; Hindricks, G.; Dhein, S.; Kottkamp, H. Expression of Connexins 40 and 43 in Human Left Atrium in Atrial Fibrillation of Different Aetiologies. Heart Br. Card. Soc. 2005, 91, 166–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gollob, M.H.; Jones, D.L.; Krahn, A.D.; Danis, L.; Gong, X.-Q.; Shao, Q.; Liu, X.; Veinot, J.P.; Tang, A.S.L.; Stewart, A.F.R.; et al. Somatic Mutations in the Connexin 40 Gene (GJA5) in Atrial Fibrillation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006, 354, 2677–2688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thibodeau, I.L.; Xu, J.; Li, Q.; Liu, G.; Lam, K.; Veinot, J.P.; Birnie, D.H.; Jones, D.L.; Krahn, A.D.; Lemery, R.; et al. Paradigm of Genetic Mosaicism and Lone Atrial Fibrillation: Physiological Characterization of a Connexin 43-Deletion Mutant Identified from Atrial Tissue. Circulation 2010, 122, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhein, S.; Rothe, S.; Busch, A.; Rojas Gomez, D.M.; Boldt, A.; Reutemann, A.; Seidel, T.; Salameh, A.; Pfannmüller, B.; Rastan, A.; et al. Effects of Metoprolol Therapy on Cardiac Gap Junction Remodelling and Conduction in Human Chronic Atrial Fibrillation. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2011, 164, 607–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igarashi, T.; Finet, J.E.; Takeuchi, A.; Fujino, Y.; Strom, M.; Greener, I.D.; Rosenbaum, D.S.; Donahue, J.K. Connexin Gene Transfer Preserves Conduction Velocity and Prevents Atrial Fibrillation. Circulation 2012, 125, 216–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nattel, S.; Heijman, J.; Zhou, L.; Dobrev, D. Molecular Basis of Atrial Fibrillation Pathophysiology and Therapy: A Translational Perspective. Circ. Res. 2020, 127, 51–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, J.H.; Werner, J.H.; Plitt, G.D.; Noble, V.V.; Spring, J.T.; Stephens, B.A.; Siddique, A.; Merritt-Genore, H.L.; Moulton, M.J.; Agrawal, D.K. Immunopathogenesis and Biomarkers of Recurrent Atrial Fibrillation Following Ablation Therapy in Patients with Preexisting Atrial Fibrillation. Expert Rev. Cardiovasc. Ther. 2019, 17, 193–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, H.; Zhou, Q.; Lan, R.; Røe, O.D.; Chen, X.; Chen, Y.; Wang, D. A Functional Polymorphism C-509T in TGFβ-1 Promoter Contributes to Susceptibility and Prognosis of Lone Atrial Fibrillation in Chinese Population. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e112912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Liu, S.; Yu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, W.; Cui, M.; Li, L. The Predictive Value of Growth Differentiation Factor-15 in Recurrence of Atrial Fibrillation after Catheter Ablation. Mediators Inflamm. 2020, 2020, 8360936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakynthinos, G.E.; Tsolaki, V.; Oikonomou, E.; Pantelidis, P.; Gialamas, I.; Kalogeras, K.; Zakynthinos, E.; Vavuranakis, M.; Siasos, G. Unveiling the Role of Endothelial Dysfunction: A Possible Key to Enhancing Catheter Ablation Success in Atrial Fibrillation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 2317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyalla, V.; Harling, L.; Snell, A.; Kralj-Hans, I.; Barradas-Pires, A.; Haldar, S.; Khan, H.R.; Cleland, J.G.F.; Athanasiou, T.; Harding, S.E.; et al. Biomarkers as Predictors of Recurrence of Atrial Fibrillation Post Ablation: An Updated and Expanded Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Res. Cardiol. 2022, 111, 680–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henningsen, K.M.A.; Nilsson, B.; Bruunsgaard, H.; Chen, X.; Pedersen, B.K.; Svendsen, J.H. Prognostic Impact of Hs-CRP and IL-6 in Patients Undergoing Radiofrequency Catheter Ablation for Atrial Fibrillation. Scand. Cardiovasc. J. SCJ 2009, 43, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carballo, D.; Noble, S.; Carballo, S.; Stirnemann, J.; Muller, H.; Burri, H.; Vuilleumier, N.; Talajic, M.; Tardif, J.-C.; Keller, P.-F.; et al. Biomarkers and Arrhythmia Recurrence Following Radiofrequency Ablation of Atrial Fibrillation. J. Int. Med. Res. 2018, 46, 5183–5194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, H.S.; Schultz, C.; Dang, J.; Alasady, M.; Lau, D.H.; Brooks, A.G.; Wong, C.X.; Roberts-Thomson, K.C.; Young, G.D.; Worthley, M.I.; et al. Time Course of Inflammation, Myocardial Injury, and Prothrombotic Response After Radiofrequency Catheter Ablation for Atrial Fibrillation. Circ. Arrhythm. Electrophysiol. 2014, 7, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Z.; Song, T.; Huang, S.; Liu, M.; Ma, J.; Zhang, J.; Yu, P.; Liu, X. Relationship between Serum Growth Differentiation Factor 15, Fibroblast Growth Factor-23 and Risk of Atrial Fibrillation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 899667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragón-Herrera, A.; Couselo-Seijas, M.; Feijóo-Bandín, S.; Anido-Varela, L.; Moraña-Fernández, S.; Tarazón, E.; Roselló-Lletí, E.; Portolés, M.; Martínez-Sande, J.L.; García-Seara, J.; et al. Relaxin-2 Plasma Levels in Atrial Fibrillation Are Linked to Inflammation and Oxidative Stress Markers. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 22287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, X.; Chen, L.; Sun, L.; Chen, C.; Gao, Z.; Huang, W.; Zhou, H. Serum Relaxin Level Predicts Recurrence of Atrial Fibrillation after Radiofrequency Catheter Ablation. Heart Vessels 2019, 34, 1543–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalenderoglu, K.; Hayiroglu, M.I.; Cinar, T.; Oz, M.; Bayraktar, G.A.; Cam, R.; Gurkan, K. Comparison of Inflammatory Markers for the Prediction of Atrial Fibrillation Recurrence Following Cryoablation. Biomark. Med. 2024, 18, 717–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- University Hospital. Bordeaux Inflammatory Response Following “Pulsed Field Ablation” vs. Radiofrequency Ablation of Paroxysmal Atrial Fibrillation-2. 2025. Available online: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov (accessed on 18 March 2025).

- Meng, F.; Jin, S.; Liu, N. Cardiac Selectivity in Pulsed Field Ablation. Curr. Opin. Cardiol. 2025, 40, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, G.R.; Nalliah, C.J.; Lee, G.; Voskoboinik, A.; Prabhu, S.; Parameswaran, R.; Sugumar, H.; Anderson, R.D.; Ling, L.-H.; McLellan, A.; et al. Genetic Susceptibility to Atrial Fibrillation Is Associated With Atrial Electrical Remodeling and Adverse Post-Ablation Outcome. JACC Clin. Electrophysiol. 2020, 6, 1509–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, E.; Zhao, Y.; Everett, T.H.; Chen, P. Ganglionated Plexi as Neuromodulation Targets for Atrial Fibrillation. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 2017, 28, 1485–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saffitz, J.E. Gap Junctions: Functional Effects of Molecular Structure and Tissue Distribution. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1997, 430, 291–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatkin, D.; Otway, R.; Vandenberg, J.I. Genes and Atrial Fibrillation: A New Look at an Old Problem. Circulation 2007, 116, 782–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feghaly, J.; Zakka, P.; London, B.; MacRae, C.A.; Refaat, M.M. Genetics of Atrial Fibrillation. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2018, 7, e009884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.; Li, M.; Li, H.; Tang, K.; Zhuang, J.; Zhang, J.; Xiao, J.; Jiang, H.; Li, D.; Yu, Y.; et al. Dysfunction of Myosin Light-Chain 4 (MYL4) Leads to Heritable Atrial Cardiomyopathy With Electrical, Contractile, and Structural Components: Evidence From Genetically-Engineered Rats. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2017, 6, e007030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahlberg, G.; Refsgaard, L.; Lundegaard, P.R.; Andreasen, L.; Ranthe, M.F.; Linscheid, N.; Nielsen, J.B.; Melbye, M.; Haunsø, S.; Sajadieh, A.; et al. Rare Truncating Variants in the Sarcomeric Protein Titin Associate with Familial and Early-Onset Atrial Fibrillation. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 4316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.D.; Marcus, G.M. The Burgeoning Field of Ablatogenomics. Circ. Arrhythm. Electrophysiol. 2015, 8, 258–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudbjartsson, D.F.; Arnar, D.O.; Helgadottir, A.; Gretarsdottir, S.; Holm, H.; Sigurdsson, A.; Jonasdottir, A.; Baker, A.; Thorleifsson, G.; Kristjansson, K.; et al. Variants Conferring Risk of Atrial Fibrillation on Chromosome 4q25. Nature 2007, 448, 353–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mommersteeg, M.T.M.; Brown, N.A.; Prall, O.W.J.; de Gier-de Vries, C.; Harvey, R.P.; Moorman, A.F.M.; Christoffels, V.M. Pitx2c and Nkx2-5 Are Required for the Formation and Identity of the Pulmonary Myocardium. Circ. Res. 2007, 101, 902–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, L.; Yin, Y.; Ling, Z.; Su, L.; Liu, Z.; Wu, J.; Du, H.; Lan, X.; Fan, J.; Chen, W.; et al. Predictors of Late Recurrence of Atrial Fibrillation after Catheter Ablation. Int. J. Cardiol. 2013, 164, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lage, R.; Cebro-Márquez, M.; Vilar-Sánchez, M.E.; González-Melchor, L.; García-Seara, J.; Martínez-Sande, J.L.; Fernández-López, X.A.; Aragón-Herrera, A.; Martínez-Monzonís, M.A.; González-Juanatey, J.R.; et al. Circulating miR-451a Expression May Predict Recurrence in Atrial Fibrillation Patients after Catheter Pulmonary Vein Ablation. Cells 2023, 12, 638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakimoto, Y.; Tanaka, M.; Kamiguchi, H.; Hayashi, H.; Ochiai, E.; Osawa, M. MicroRNA Deep Sequencing Reveals Chamber-Specific miR-208 Family Expression Patterns in the Human Heart. Int. J. Cardiol. 2016, 211, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Girmatsion, Z.; Biliczki, P.; Bonauer, A.; Wimmer-Greinecker, G.; Scherer, M.; Moritz, A.; Bukowska, A.; Goette, A.; Nattel, S.; Hohnloser, S.H.; et al. Changes in microRNA-1 Expression and IK1 up-Regulation in Human Atrial Fibrillation. Heart Rhythm 2009, 6, 1802–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Den Berg, N.W.E.; Kawasaki, M.; Berger, W.R.; Neefs, J.; Meulendijks, E.; Tijsen, A.J.; De Groot, J.R. MicroRNAs in Atrial Fibrillation: From Expression Signatures to Functional Implications. Cardiovasc. Drugs Ther. 2017, 31, 345–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, A.M.G.D.; Araújo, J.N.G.D.; Freitas, R.C.C.D.; Silbiger, V.N. Circulating MicroRNAs as Potential Biomarkers of Atrial Fibrillation. BioMed Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 7804763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boxhammer, E.; Dienhart, C.; Rezar, R.; Hoppe, U.C.; Lichtenauer, M. Deciphering the Role of microRNAs: Unveiling Clinical Biomarkers and Therapeutic Avenues in Atrial Fibrillation and Associated Stroke—A Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komal, S.; Yin, J.-J.; Wang, S.-H.; Huang, C.-Z.; Tao, H.-L.; Dong, J.-Z.; Han, S.-N.; Zhang, L.-R. MicroRNAs: Emerging Biomarkers for Atrial Fibrillation. J. Cardiol. 2019, 74, 475–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Maleck, C.; Von Ungern-Sternberg, S.N.I.; Neupane, B.; Heinzmann, D.; Marquardt, J.; Duckheim, M.; Scheckenbach, C.; Stimpfle, F.; Gawaz, M.; et al. Circulating MicroRNA-21 Correlates With Left Atrial Low-Voltage Areas and Is Associated With Procedure Outcome in Patients Undergoing Atrial Fibrillation Ablation. Circ. Arrhythm. Electrophysiol. 2018, 11, e006242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sygitowicz, G.; Maciejak-Jastrzębska, A.; Sitkiewicz, D. A Review of the Molecular Mechanisms Underlying Cardiac Fibrosis and Atrial Fibrillation. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 4430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, K.; Tu, T.; Yuan, Z.; Yi, J.; Zhou, Y.; Liao, X.; Liu, Q.; Zhou, X. DNA Methylation Dysregulations in Valvular Atrial Fibrillation. Clin. Cardiol. 2017, 40, 686–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felisbino, M.B.; McKinsey, T.A. Epigenetics in Cardiac Fibrosis: Emphasis on Inflammation and Fibroblast Activation. JACC Basic Transl. Sci. 2018, 3, 704–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, H.; Shi, K.-H.; Yang, J.-J.; Li, J. Epigenetic Mechanisms in Atrial Fibrillation: New Insights and Future Directions. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2016, 26, 306–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz, B.; Schulte, J.S.; Hamer, S.; Himmler, K.; Pluteanu, F.; Seidl, M.D.; Stein, J.; Wardelmann, E.; Hammer, E.; Völker, U.; et al. HDAC (Histone Deacetylase) Inhibitor Valproic Acid Attenuates Atrial Remodeling and Delays the Onset of Atrial Fibrillation in Mice. Circ. Arrhythm. Electrophysiol. 2019, 12, e007071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Zhou, J.; Gao, J.; Liu, Y.; Gu, S.; Zhang, X.; Su, P. Genome-Wide DNA Methylation Analysis in Permanent Atrial Fibrillation. Mol. Med. Rep. 2017, 16, 5505–5514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, H.; Yang, J.-J.; Chen, Z.-W.; Xu, S.-S.; Zhou, X.; Zhan, H.-Y.; Shi, K.-H. DNMT3A Silencing RASSF1A Promotes Cardiac Fibrosis through Upregulation of ERK1/2. Toxicology 2014, 323, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, M.; Ge, W.; Li, Z.; Wang, C.; Zhang, Y. DNA Methylation in Atrial Fibrillation and Its Potential Role in Precision Medicine. Methods Mol. Biol. 2020, 2204, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalla, M.; Hao, G.; Tapoulal, N.; Tomek, J.; Liu, K.; Woodward, L.; Oxford Acute Myocardial Infarction (OxAMI) Study; Dall’Armellina, E.; Banning, A.P.; Choudhury, R.P.; et al. The Cardiac Sympathetic Co-Transmitter Neuropeptide Y Is pro-Arrhythmic Following ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction despite Beta-Blockade. Eur. Heart J. 2020, 41, 2168–2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajijola, O.A.; Chatterjee, N.A.; Gonzales, M.J.; Gornbein, J.; Liu, K.; Li, D.; Paterson, D.J.; Shivkumar, K.; Singh, J.P.; Herring, N. Coronary Sinus Neuropeptide Y Levels and Adverse Outcomes in Patients With Stable Chronic Heart Failure. JAMA Cardiol. 2020, 5, 318–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelavic, M.M.; Țica, O.; Pintaric, H.; Țica, O. Circulating Neuropeptide Y May Be a Biomarker for Diagnosing Atrial Fibrillation. Cardiology 2023, 148, 593–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stavrakis, S.; Morris, L.; Takashima, A.D.; Elkholey, K.; Van Wagoner, D.R.; Ajijola, O.A. Circulating Neuropeptide Y as a Biomarker for Neuromodulation in Atrial Fibrillation. JACC Clin. Electrophysiol. 2020, 6, 1575–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Q.; Zhang, N.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, A.; Li, H.; Bai, S.; Shang, L.; Du, J.; Hou, Y. Multiomics Analysis of Canine Myocardium after Circumferential Pulmonary Vein Ablation: Effect of Neuropeptide Y on Long-Term Reinduction of Atrial Fibrillation. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2024, 28, e18582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Guo, J.; Li, Y.; Liu, H.; Kang, X.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Y. Circulating Neuropeptide Y May Be a Biomarker for Diagnosing Atrial Fibrillation. Cardiology 2023, 148, 517–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; He, Y.; Yin, Z.; Li, R.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H. Circulating Neuropeptide Y as a Biomarker in Postoperative Atrial Fibrillation Cases Administered Off-Pump Coronary Bypass Graft Surgery. Heliyon 2024, 10, e31251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Liu, L.; Jiang, J.Y.; Qu, X.F.; Yu, G. Parasympathetic and Substance P-Immunoreactive Nerve Denervation in Atrial Fibrillation Models. Cardiovasc. Pathol. 2012, 21, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavrakis, S.; Po, S. Ganglionated Plexi Ablation: Physiology and Clinical Applications. Arrhythmia Electrophysiol. Rev. 2017, 6, 186–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avazzadeh, S.; McBride, S.; O’Brien, B.; Coffey, K.; Elahi, A.; O’Halloran, M.; Soo, A.; Quinlan, L.R. Ganglionated Plexi Ablation for the Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 3081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksu, T.; Skeete, J.R.; Huang, H.H. Ganglionic Plexus Ablation: A Step-by-Step Guide for Electrophysiologists and Review of Modalities for Neuromodulation for the Management of Atrial Fibrillation. Arrhythm Electrophysiol. Rev. 2022, 12, e02. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherschel, K.; Hedenus, K.; Jungen, C.; Lemoine, M.D.; Rübsamen, N.; Veldkamp, M.W.; Klatt, N.; Lindner, D.; Westermann, D.; Casini, S.; et al. Cardiac Glial Cells Release Neurotrophic S100B upon Catheter-Based Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation. Sci. Transl. Med. 2019, 11, eaav7770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafeiropoulos, S.; Stavrakis, S. Impact of Pulsed Field Ablation on Autonomic Nervous System. JACC Clin. Electrophysiol. 2023, 9, 494–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mark Richards, A.; Lainchbury, J.G.; Troughton, R.W.; Nicholls, G.; Frampton, C.M.; Yandle, T.G. Plasma Amino-Terminal pro-B-Type Natriuretic Peptide Predicts Postcardioversion Reversion to Atrial Fibrillation. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2003, 41, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dernellis, J.; Panaretou, M. C-Reactive Protein and Paroxysmal Atrial Fibrillation: Evidence of the Implication of an Inflammatory Process in Paroxysmal Atrial Fibrillation. Acta Cardiol. 2001, 56, 375–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, C.A.; Rembert, J.C.; Greenfield, J.C. Compliance of Left Atrium with and without Left Atrium Appendage. Am. J. Physiol.-Heart Circ. Physiol. 1990, 259, H1006–H1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Saady, N.M.; Obel, O.A.; Camm, A.J. Left Atrial Appendage: Structure, Function, and Role in Thromboembolism. Heart 1999, 82, 547–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaghi, S.; Song, C.; Gray, W.A.; Furie, K.L.; Elkind, M.S.V.; Kamel, H. Left Atrial Appendage Function and Stroke Risk. Stroke 2015, 46, 3554–3559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unsicker, K.; Spittau, B.; Krieglstein, K. The Multiple Facets of the TGF-β Family Cytokine Growth/Differentiation Factor-15/Macrophage Inhibitory Cytokine-1. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2013, 24, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kempf, T.; Eden, M.; Strelau, J.; Naguib, M.; Willenbockel, C.; Tongers, J.; Heineke, J.; Kotlarz, D.; Xu, J.; Molkentin, J.D.; et al. The Transforming Growth Factor-β Superfamily Member Growth-Differentiation Factor-15 Protects the Heart From Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury. Circ. Res. 2006, 98, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.J.; Wollert, K.C.; Larson, M.G.; Coglianese, E.; McCabe, E.L.; Cheng, S.; Ho, J.E.; Fradley, M.G.; Ghorbani, A.; Xanthakis, V.; et al. Prognostic Utility of Novel Biomarkers of Cardiovascular Stress: The Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 2012, 126, 1596–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gizatulina, T.P.; Mamarina, A.V.; Martyanova, L.U.; Belonogov, D.V.; Kolunin, G.V.; Petelina, T.I.; Shirokov, N.E.; Gorbatenko, E.A. The Soluble ST2 Level Predicts Risk of Atrial Fibrillation Recurrences in Long-Term Period after Radiofrequency Ablation. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2024, 24, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teichman, S.L.; Unemori, E.; Teerlink, J.R.; Cotter, G.; Metra, M. Relaxin: Review of Biology and Potential Role in Treating Heart Failure. Curr. Heart Fail. Rep. 2010, 7, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Qu, X.; Gao, Z.; Zheng, G.; Lin, J.; Su, L.; Huang, Z.; Li, H.; Huang, W. Relaxin Level in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation and Association with Heart Failure Occurrence: A STROBE Compliant Article. Medicine 2016, 95, e3664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmud, F.; Sarker, D.B.; Jocelyn, J.A.; Sang, Q.-X.A. Molecular and Cellular Effects of Microplastics and Nanoplastics: Focus on Inflammation and Senescence. Cells 2024, 13, 1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, H.; Vidili, G.; Casu, G.; Navarese, E.P.; Sechi, L.A.; Chen, Y. Microplastics and Nanoplastics in Cardiovascular Disease—A Narrative Review with Worrying Links. Front. Toxicol. 2024, 6, 1479292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marfella, R.; Prattichizzo, F.; Sardu, C.; Fulgenzi, G.; Graciotti, L.; Spadoni, T.; D’Onofrio, N.; Scisciola, L.; Grotta, R.L.; Frigé, C.; et al. Microplastics and Nanoplastics in Atheromas and Cardiovascular Events. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 390, 900–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Monaco, A.; Vitulano, N.; Troisi, F.; Quadrini, F.; Romanazzi, I.; Calvi, V.; Grimaldi, M. Pulsed Field Ablation to Treat Atrial Fibrillation: A Review of the Literature. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2022, 9, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oda, Y.; Nogami, A.; Igarashi, D.; Usui, R.; Uno, K. A Case Report of Persistent Phrenic Nerve Injury by Pulsed Field Ablation: Lessons from Anatomical Reconstruction and Electrode Positioning. Hear. Case Rep. 2025, 11, 763–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, V.Y.; Gerstenfeld, E.P.; Natale, A.; Whang, W.; Cuoco, F.A.; Patel, C.; Mountantonakis, S.E.; Gibson, D.N.; Harding, J.D.; Ellis, C.R.; et al. Pulsed Field or Conventional Thermal Ablation for Paroxysmal Atrial Fibrillation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 389, 1660–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurhofer, J.; Kueffer, T.; Madaffari, A.; Stettler, R.; Stefanova, A.; Seiler, J.; Thalmann, G.; Kozhuharov, N.; Galuszka, O.; Servatius, H.; et al. Pulsed-Field vs. Cryoballoon vs. Radiofrequency Ablation: A Propensity Score Matched Comparison of One-Year Outcomes after Pulmonary Vein Isolation in Patients with Paroxysmal Atrial Fibrillation. J. Interv. Card. Electrophysiol. 2024, 67, 389–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinsch, N.; Füting, A.; Hartl, S.; Höwel, D.; Rausch, E.; Lin, Y.; Kasparian, K.; Neven, K. Pulmonary Vein Isolation Using Pulsed Field Ablation vs. High-Power Short-Duration Radiofrequency Ablation in Paroxysmal Atrial Fibrillation: Efficacy, Safety, and Long-Term Follow-up (PRIORI Study). Europace 2024, 26, euae194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.-C.; Mao, Y.-J.; Huang, Q.-Y.; Cheng, Z.-D.; He, S.-B.; Xu, Q.-X.; Zhang, Y. Meta-Analysis of Thermal Versus Pulse Field Ablation for Pulmonary Vein Isolation Durability in Atrial Fibrillation: Insights From Repeat Ablation. Clin. Cardiol. 2025, 48, e70151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, V.Y.; Neuzil, P.; Koruth, J.S.; Petru, J.; Funosako, M.; Cochet, H.; Sediva, L.; Chovanec, M.; Dukkipati, S.R.; Jais, P. Pulsed Field Ablation for Pulmonary Vein Isolation in Atrial Fibrillation. JACC 2019, 74, 315–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, G.; Yao, L.; You, L. Inflammation Response Post-Radiofrequency Ablation for Atrial Fibrillation: Implications for Early Atrial Fibrillation Recurrence. Pol. Heart J. Kardiologia Pol. 2025, 83, 570–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozen, S.; Demirkaya, E.; Erer, B.; Livneh, A.; Ben-Chetrit, E.; Giancane, G.; Ozdogan, H.; Abu, I.; Gattorno, M.; Hawkins, P.N.; et al. EULAR Recommendations for the Management of Familial Mediterranean Fever. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2016, 75, 644–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kommu, S.; Arepally, S. The Effect of Colchicine on Atrial Fibrillation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cureus 2023, 15, e35120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarpelon, C.S.; Netto, M.C.; Jorge, J.C.M.; Fabris, C.C.; Desengrini, D.; Jardim, M.d.S.; Silva, D.G. da Colchicine to Reduce Atrial Fibrillation in the Postoperative Period of Myocardial Revascularization. Arq. Bras. Cardiol. 2016, 107, 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imazio, M.; Brucato, A.; Ferrazzi, P.; Rovere, M.E.; Gandino, A.; Cemin, R.; Ferrua, S.; Belli, R.; Maestroni, S.; Simon, C.; et al. Colchicine Reduces Postoperative Atrial Fibrillation: Results of the Colchicine for the Prevention of the Postpericardiotomy Syndrome (COPPS) Atrial Fibrillation Substudy. Circulation 2011, 124, 2290–2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koyama, T.; Sekiguchi, Y.; Tada, H.; Arimoto, T.; Yamasaki, H.; Kuroki, K.; Machino, T.; Tajiri, K.; Zhu, X.D.; Kanemoto, M.; et al. Comparison of Characteristics and Significance of Immediate versus Early versus No Recurrence of Atrial Fibrillation after Catheter Ablation. Am. J. Cardiol. 2009, 103, 1249–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deftereos, S.; Giannopoulos, G.; Kossyvakis, C.; Efremidis, M.; Panagopoulou, V.; Kaoukis, A.; Raisakis, K.; Bouras, G.; Angelidis, C.; Theodorakis, A.; et al. Colchicine for Prevention of Early Atrial Fibrillation Recurrence after Pulmonary Vein Isolation: A Randomized Controlled Study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2012, 60, 1790–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koyama, T.; Tada, H.; Sekiguchi, Y.; Arimoto, T.; Yamasaki, H.; Kuroki, K.; Machino, T.; Tajiri, K.; Zhu, X.D.; Kanemoto-Igarashi, M.; et al. Prevention of Atrial Fibrillation Recurrence with Corticosteroids after Radiofrequency Catheter Ablation: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2010, 56, 1463–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Won, H.; Kim, J.-Y.; Shim, J.; Uhm, J.-S.; Pak, H.-N.; Lee, M.-H.; Joung, B. Effect of a Single Bolus Injection of Low-Dose Hydrocortisone for Prevention of Atrial Fibrillation Recurrence after Radiofrequency Catheter Ablation. Circ. J. Off. J. Jpn. Circ. Soc. 2013, 77, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yared, J.-P.; Bakri, M.H.; Erzurum, S.C.; Moravec, C.S.; Laskowski, D.M.; Van Wagoner, D.R.; Mascha, E.; Thornton, J. Effect of Dexamethasone on Atrial Fibrillation after Cardiac Surgery: Prospective, Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 2007, 21, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, J.G.; Khairy, P.; Nattel, S.; Vanella, A.; Rivard, L.; Guerra, P.G.; Dubuc, M.; Dyrda, K.; Thibault, B.; Talajic, M.; et al. Corticosteroid Use during Pulmonary Vein Isolation Is Associated with a Higher Prevalence of Dormant Pulmonary Vein Conduction. Heart Rhythm 2013, 10, 1569–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.W.; Han, M.; Jung, I.; Ahn, S.S. New-Onset Atrial Fibrillation in Seropositive Rheumatoid Arthritis: Association with Disease-Modifying Anti-Rheumatic Drugs Treatment. Rheumatology 2024, 63, 630–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, M.P.; Hua, T.A.; Böhm, M.; Wachtell, K.; Kjeldsen, S.E.; Schmieder, R.E. Prevention of Atrial Fibrillation by Renin-Angiotensin System Inhibition a Meta-Analysis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2010, 55, 2299–2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baía Bezerra, F.; Rodrigues Sobreira, L.E.; Tsuchiya Sano, V.K.; de Oliveira Macena Lôbo, A.; Cavalcanti Orestes Cardoso, J.H.; Alves Kelly, F.; Aquino de Moraes, F.C.; Consolim-Colombo, F.M. Efficacy of Sacubitril-Valsartan vs. Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors or Angiotensin Receptor Blockers in Preventing Atrial Fibrillation Recurrence after Catheter Ablation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Herz 2025, 50, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Cui, W.; Zhang, X.; Tian, Y.; Huang, G.; He, W.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, X.; Li, D.; Liu, X. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Renin-Angiotensin System Inhibitors and Angiotensin Receptor Neprilysin Inhibitors in Preventing Recurrence After Atrial Fibrillation Ablation. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2024, 83, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saygili, E.; Rana, O.R.; Saygili, E.; Reuter, H.; Frank, K.; Schwinger, R.H.G.; Müller-Ehmsen, J.; Zobel, C. Losartan Prevents Stretch-Induced Electrical Remodeling in Cultured Atrial Neonatal Myocytes. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2007, 292, H2898–H2905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goette, A.; Arndt, M.; Röcken, C.; Spiess, A.; Staack, T.; Geller, J.C.; Huth, C.; Ansorge, S.; Klein, H.U.; Lendeckel, U. Regulation of Angiotensin II Receptor Subtypes during Atrial Fibrillation in Humans. Circulation 2000, 101, 2678–2681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, H.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Xiao, H. The Effect of Statins on the Recurrence Rate of Atrial Fibrillation after Catheter Ablation: A Meta-Analysis. Pacing Clin. Electrophysiol. PACE 2018, 41, 1420–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, X.; Gao, Y.; He, M.; Luo, Y.; Wei, Y.; Duan, Y.; Zhang, S.; Yu, H.; Kan, J.; Hou, T.; et al. Evolocumab Prevents Atrial Fibrillation in Rheumatoid Arthritis Rats through Restraint of PCSK9 Induced Atrial Remodeling. J. Adv. Res. 2024, 61, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes, R.D.; Guimarães, P.O.; Schwartz, G.G.; Bhatt, D.L.; Bittner, V.A.; Budaj, A.; Dalby, A.J.; Diaz, R.; Goodman, S.G.; Harrington, R.A.; et al. Effect of Alirocumab on Incidence of Atrial Fibrillation After Acute Coronary Syndromes: Insights from the ODYSSEY OUTCOMES Trial. Am. J. Med. 2022, 135, 915–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saljic, A.; Heijman, J.; Dobrev, D. Emerging Antiarrhythmic Drugs for Atrial Fibrillation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostropolets, A.; Elias, P.A.; Reyes, M.V.; Wan, E.Y.; Pajvani, U.B.; Hripcsak, G.; Morrow, J.P. Metformin Is Associated With a Lower Risk of Atrial Fibrillation and Ventricular Arrhythmias Compared With Sulfonylureas: An Observational Study. Circ. Arrhythm. Electrophysiol. 2021, 14, e009115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metformin as an Adjunctive Therapy to Catheter Ablation in Atrial Fibrillation|Clinical Research Trial Listing (Atrial Fibrillation) (NCT04625946). Available online: https://www.trialx.com/clinical-trials/listings/225558/metformin-as-an-adjunctive-therapy-to-catheter-ablation-in-atrial-fibrillation/ (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Abdelhadi, N.A.; Ragab, K.M.; Elkholy, M.; Koneru, J.; Ellenbogen, K.A.; Pillai, A. Impact of Sodium-Glucose Co-Transporter 2 Inhibitors on Atrial Fibrillation Recurrence Post-Catheter Ablation Among Patients With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 2025, 36, 673–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Qaoud, M.R.; Kumar, A.; Tarun, T.; Abraham, S.; Ahmad, J.; Khadke, S.; Husami, R.; Kulbak, G.; Sahoo, S.; Januzzi, J.L.; et al. Impact of SGLT2 Inhibitors on AF Recurrence After Catheter Ablation in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes. JACC Clin. Electrophysiol. 2023, 9, 2109–2118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paasche, A.; Wiedmann, F.; Kraft, M.; Seibertz, F.; Herlt, V.; Blochberger, P.L.; Jávorszky, N.; Beck, M.; Weirauch, L.; Seeger, T.; et al. Acute Antiarrhythmic Effects of SGLT2 Inhibitors-Dapagliflozin Lowers the Excitability of Atrial Cardiomyocytes. Basic Res. Cardiol. 2024, 119, 93–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, H.; Sheth, A.; Nair, A.; Patel, B.; Thakkar, S.; Narasimhan, B.; Mehta, N.; Azad, Z.; Kowlgi, G.N.; Desimone, C.V.; et al. Long-Term Impact of GLP-1 Receptor Agonists on AF Recurrence After Ablation in Obese Patients. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 2025, 36, 1808–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakasis, P.; Fragakis, N.; Patoulias, D.; Theofilis, P.; Kassimis, G.; Karamitsos, T.; El-Tanani, M.; Rizzo, M. Effects of Glucagon-Like Peptide 1 Receptor Agonists on Atrial Fibrillation Recurrence After Catheter Ablation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Adv. Ther. 2024, 41, 3749–3756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohne, L.J.; Jansen, H.J.; Dorey, T.W.; Daniel, I.M.; Jamieson, K.L.; Belke, D.D.; McRae, M.D.; Rose, R.A. Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Protects Against Atrial Fibrillation and Atrial Remodeling in Type 2 Diabetic Mice. JACC Basic Transl. Sci. 2023, 8, 922–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Chen, J.; Zhao, L. N-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids for Prevention of Postoperative Atrial Fibrillation: Updated Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review. J. Interv. Card. Electrophysiol. Int. J. Arrhythm. Pacing 2018, 51, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, X.; Gao, F.; Pickett, J.K.; Al Rifai, M.; Birnbaum, Y.; Nambi, V.; Virani, S.S.; Ballantyne, C.M. Association Between Omega-3 Fatty Acid Treatment and Atrial Fibrillation in Cardiovascular Outcome Trials: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cardiovasc. Drugs Ther. 2021, 35, 793–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, M.D.; Link, M.S. Omega-3 Fatty Acids and Arrhythmias. Circulation 2024, 150, 488–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, T.; Li, B.; Li, X.; Zhang, B.; Xiao, Y.; Li, J.; Qin, F.; Liu, N.; Sun, C.; Liu, Q.; et al. Dietary ω-3 Fatty Acids Reduced Atrial Fibrillation Vulnerability via Attenuating Myocardial Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and Inflammation in a Canine Model of Atrial Fibrillation. J. Cardiol. 2022, 79, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.-F.; Chen, Y.-J.; Lin, Y.-J.; Chen, S.-A. Inflammation and the Pathogenesis of Atrial Fibrillation. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2015, 12, 230–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiedmann, F.; Beyersdorf, C.; Zhou, X.B.; Kraft, M.; Paasche, A.; Jávorszky, N.; Rinné, S.; Sutanto, H.; Büscher, A.; Foerster, K.I.; et al. Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation with Doxapram: TASK-1 Potassium Channel Inhibition as a Novel Pharmacological Strategy. Cardiovasc. Res. 2022, 118, 1728–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krisai, P.; Blum, S.; Schnabel, R.B.; Sticherling, C.; Kühne, M.; von Felten, S.; Ammann, P.; Pruvot, E.; Albert, C.M.; Conen, D. Canakinumab After Electrical Cardioversion in Patients With Persistent Atrial Fibrillation: A Pilot Randomized Trial. Circ. Arrhythm. Electrophysiol. 2020, 13, e008197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiedmann, F.; Schmidt, C. Novel Drug Therapies for Atrial Fibrillation. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2024, 21, 275–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Mechanism | Key Findings |

|---|---|

| Fibrosis and ECM Alterations |

|

| |

| |

| Role of TGF-β and MMPs |

|

| |

| |

| Cellular Hypertrophy & Myocyte Disarray |

|

| |

| Conduction Velocity & Arrhythmogenic Substrate Formation |

|

| |

| Ion-Channel Dysregulation |

|

| Connexins and Gap Junctions |

|

| |

| Inflammatory Pathways |

|

| Autonomic Nervous System Imbalance |

|

| Genetic & Epigenetic Factors |

|

| Neurohumoral Factors & Biomarkers |

|

| Nanoplastics & Microplastics (MNPs) |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sanusi, M.; Vempati, R.; Umashankar, D.; Tarannum, S.; Varma, Y.; Mohammed, F.; Mylavarapu, M.; Zakaria, F.; Nair, R.; Reddy, Y.M.; et al. Molecular Mechanisms of Atrial Fibrillation Recurrence After Successful Catheter Ablation. Cells 2026, 15, 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010036

Sanusi M, Vempati R, Umashankar D, Tarannum S, Varma Y, Mohammed F, Mylavarapu M, Zakaria F, Nair R, Reddy YM, et al. Molecular Mechanisms of Atrial Fibrillation Recurrence After Successful Catheter Ablation. Cells. 2026; 15(1):36. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010036

Chicago/Turabian StyleSanusi, Muhammad, Roopeessh Vempati, Dinakaran Umashankar, Suha Tarannum, Yash Varma, Fawaz Mohammed, Maneeth Mylavarapu, Faiza Zakaria, Rajiv Nair, Yeruva Madhu Reddy, and et al. 2026. "Molecular Mechanisms of Atrial Fibrillation Recurrence After Successful Catheter Ablation" Cells 15, no. 1: 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010036

APA StyleSanusi, M., Vempati, R., Umashankar, D., Tarannum, S., Varma, Y., Mohammed, F., Mylavarapu, M., Zakaria, F., Nair, R., Reddy, Y. M., & Toquica Gahona, C. (2026). Molecular Mechanisms of Atrial Fibrillation Recurrence After Successful Catheter Ablation. Cells, 15(1), 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010036