Testosterone and Long-Pulse-Width Stimulation (TLPS) on Denervated Muscles and Cardio-Metabolic Risk Factors After Spinal Cord Injury: A Pilot Randomized Trial

Highlights

- Long pulse width stimulation (LPWS)is a safe rehabilitation approach to stimulate denervated muscles.

- LPWS training has potential cardio-metabolic benefits in SCI persons with lower motor neuron injury.

- The current training protocol needs to be refined to increase dosing as well as loading of the denervated muscles in large sample sizes.

- The FDA should consider the findings to facilitate early rehabilitation of SCI persons with lower motor neuron injury.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Timeline of the Study

2.1.1. Testing for LMN Denervation

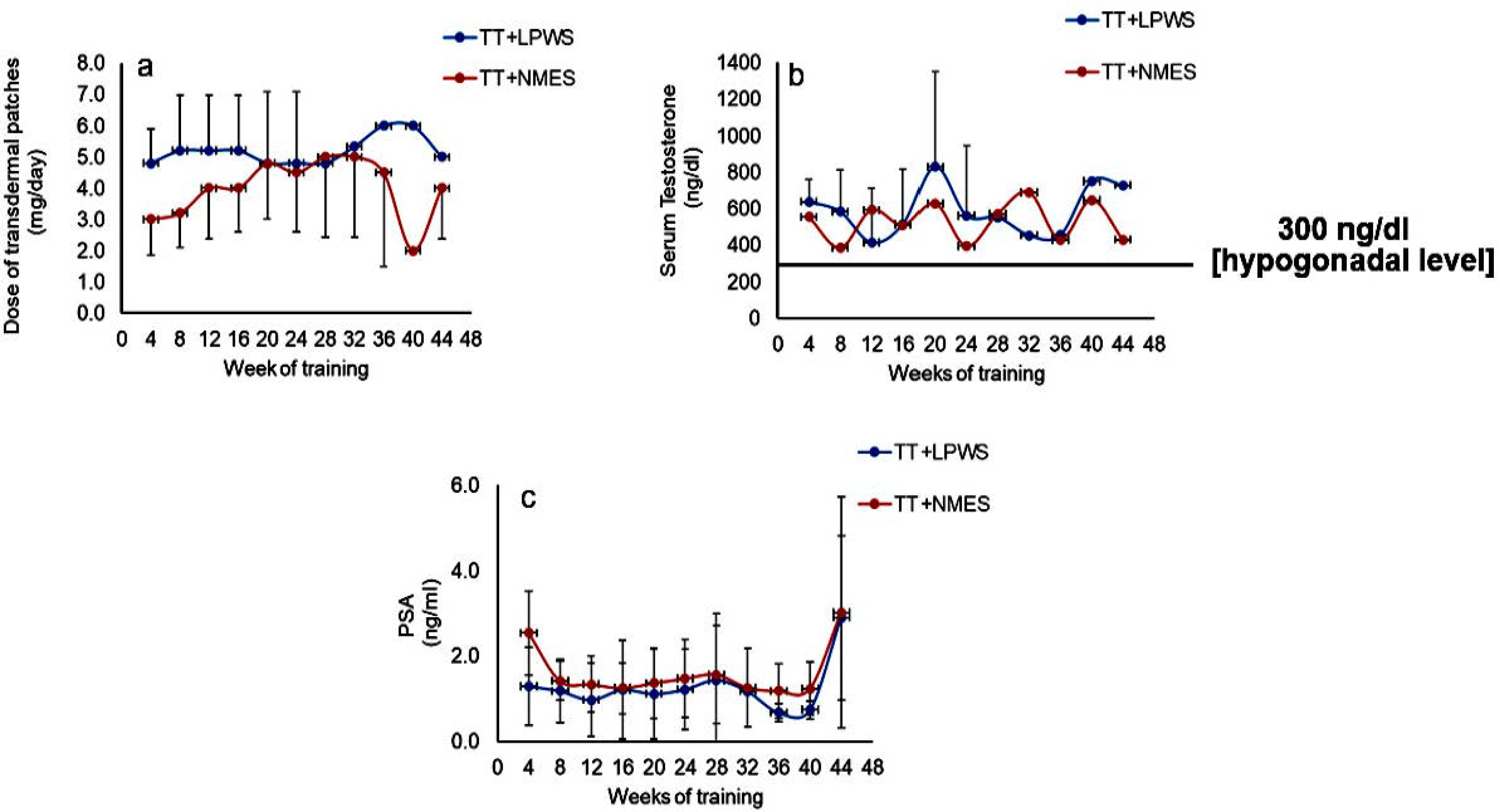

2.1.2. Testing for Serum Testosterone and PSA

2.2. Interventions

2.2.1. TT + LPWS Group

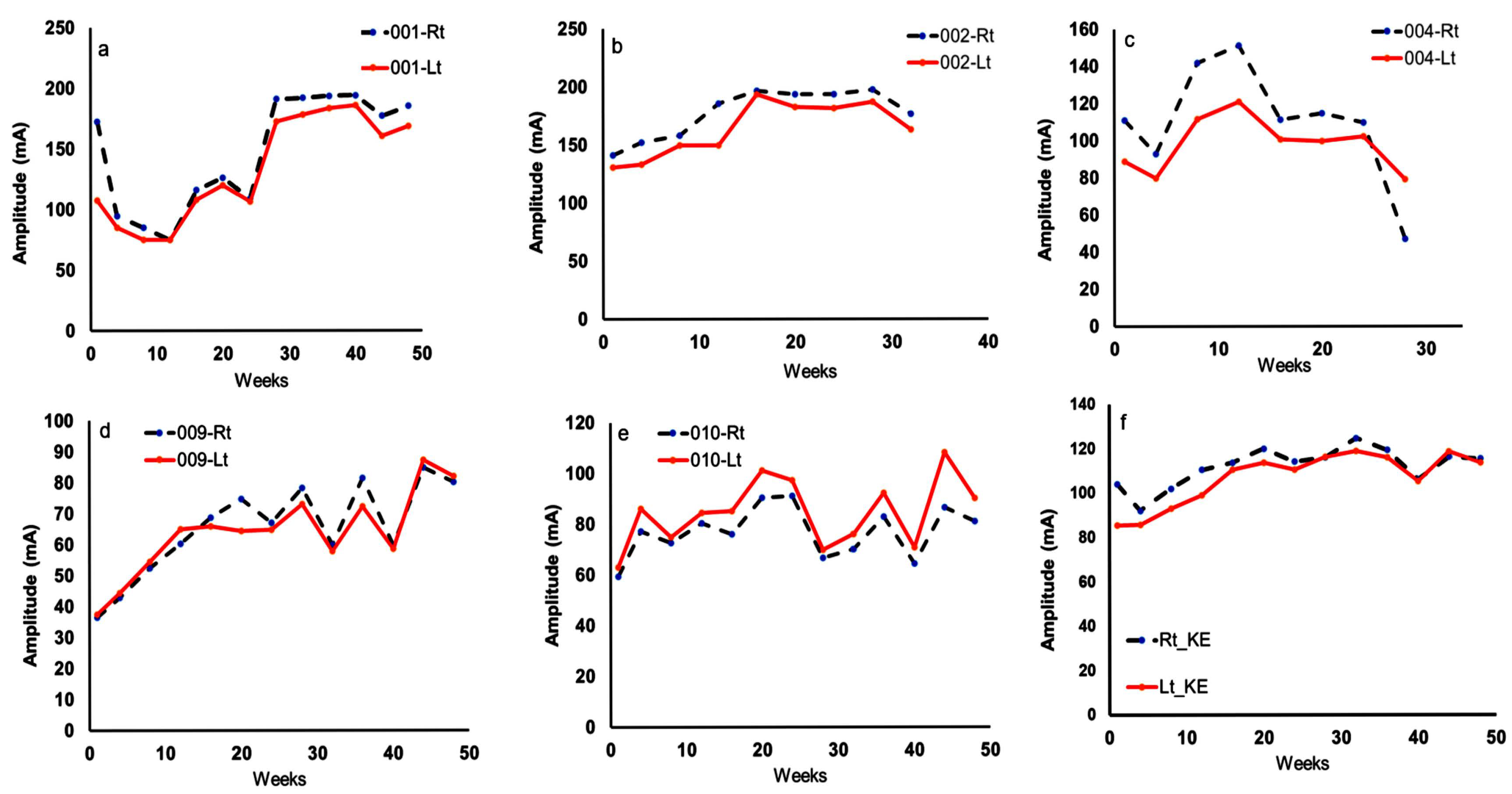

2.2.2. Control Group (TT + Standard NMES)

2.2.3. Transdermal TT for Both Groups

2.3. Measurements

2.3.1. Body Composition Assessment

Body Mass Index (BMI) and Anthropometrics

Dual Energy X-Ray Absorptiometry (iDXA)

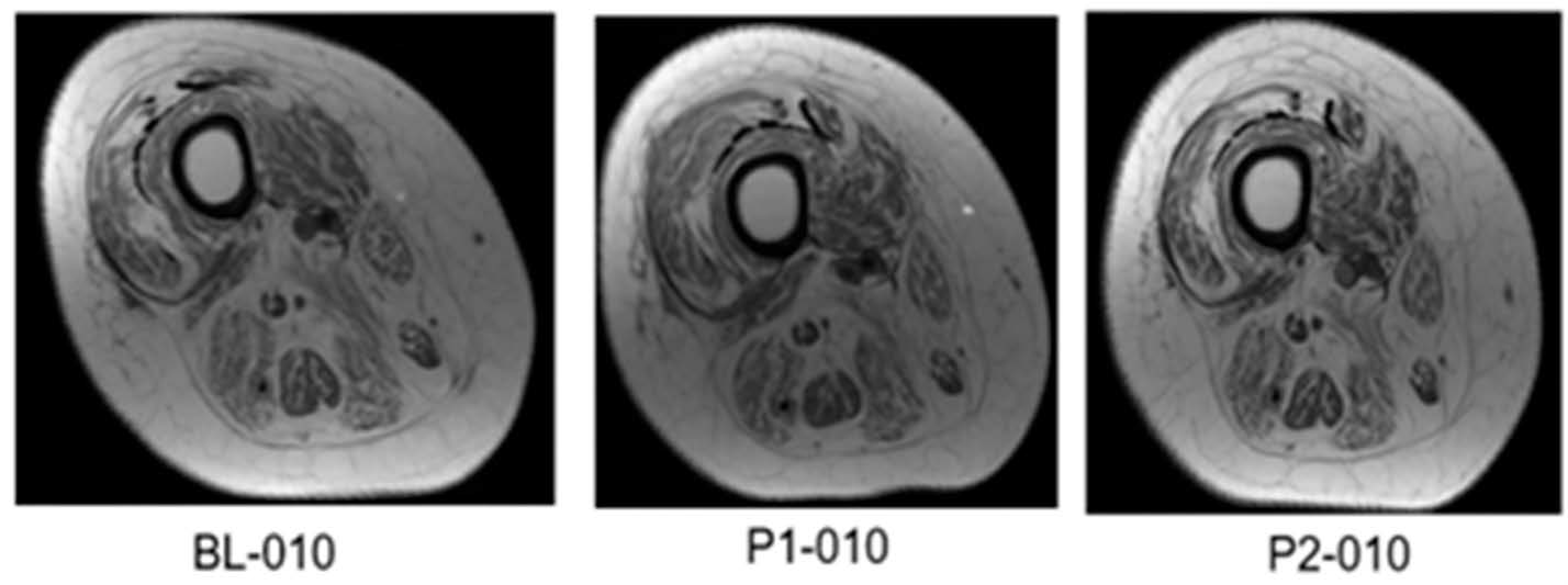

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

2.3.2. Metabolic Studies

Resting Metabolic Rate (RMR)

Serum Fasting Anabolic and Inflammatory Biomarkers

Blood Lipids

Intravenous Glucose Tolerance Test (IVGTT)

2.3.3. Muscle Biopsies

Real-Time Quantitative PCR (qPCR)

Mitochondrial Respiratory Activities

Statistical Analysis

3. Results

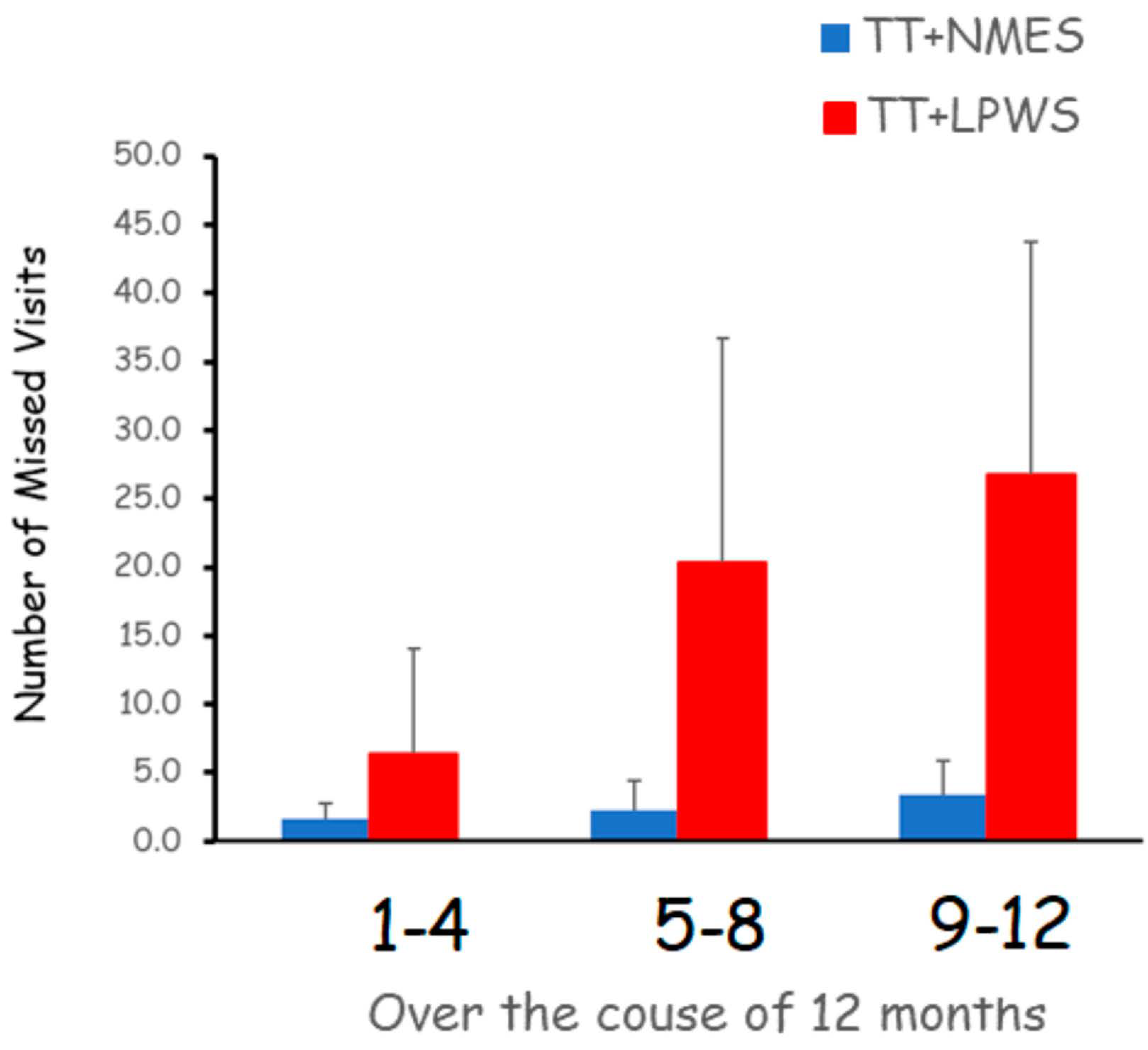

3.1. Compliance, Adherence and Dietary Records in Persons with SCI

3.2. Effects on Body Composition Parameters

3.2.1. Effects of TT + LPWS Compared to TT + NMES on Body Weight and BMI

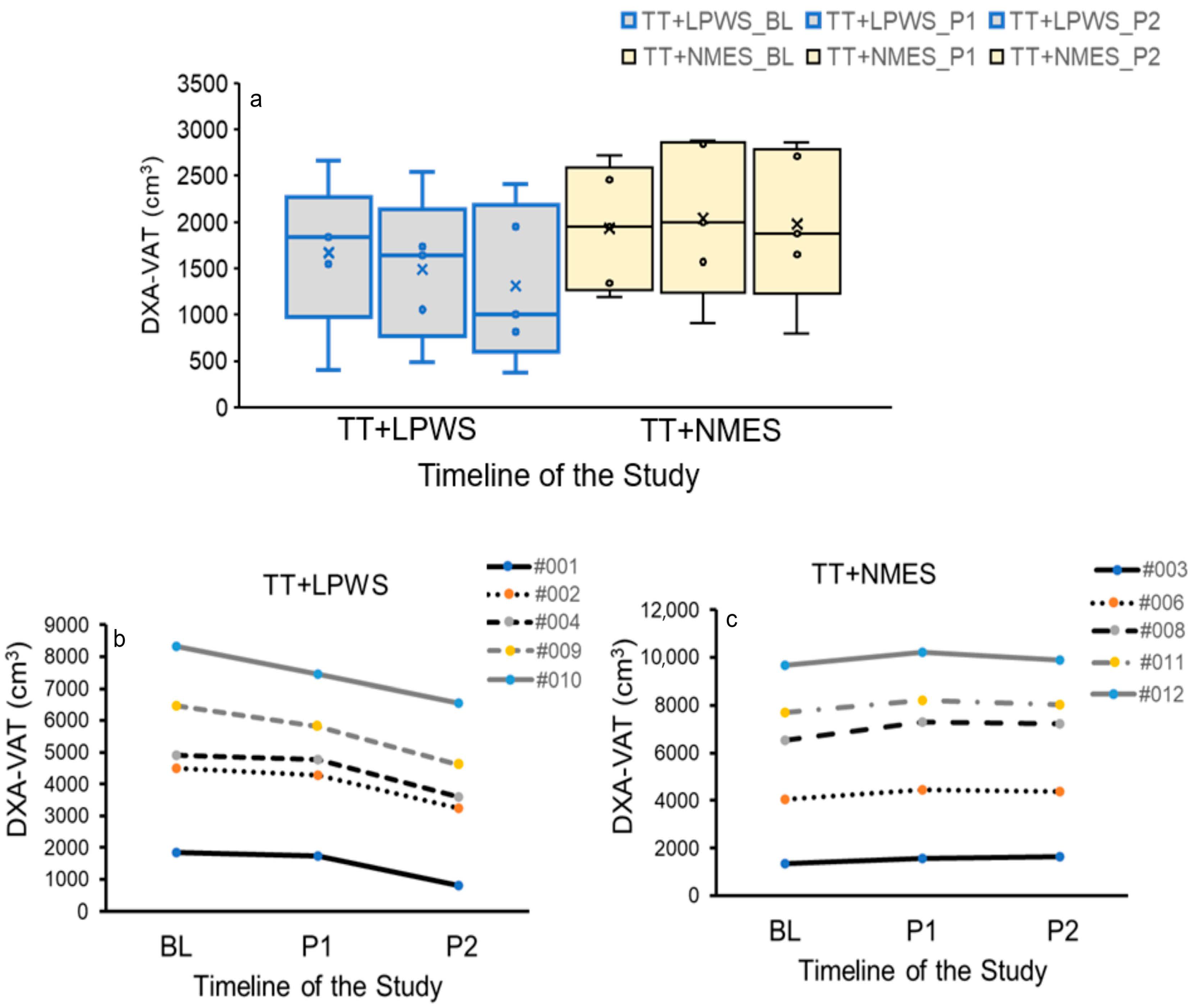

3.2.2. Effects of TT + LPWS Compared TT to + NMES on Body Composition Assessment

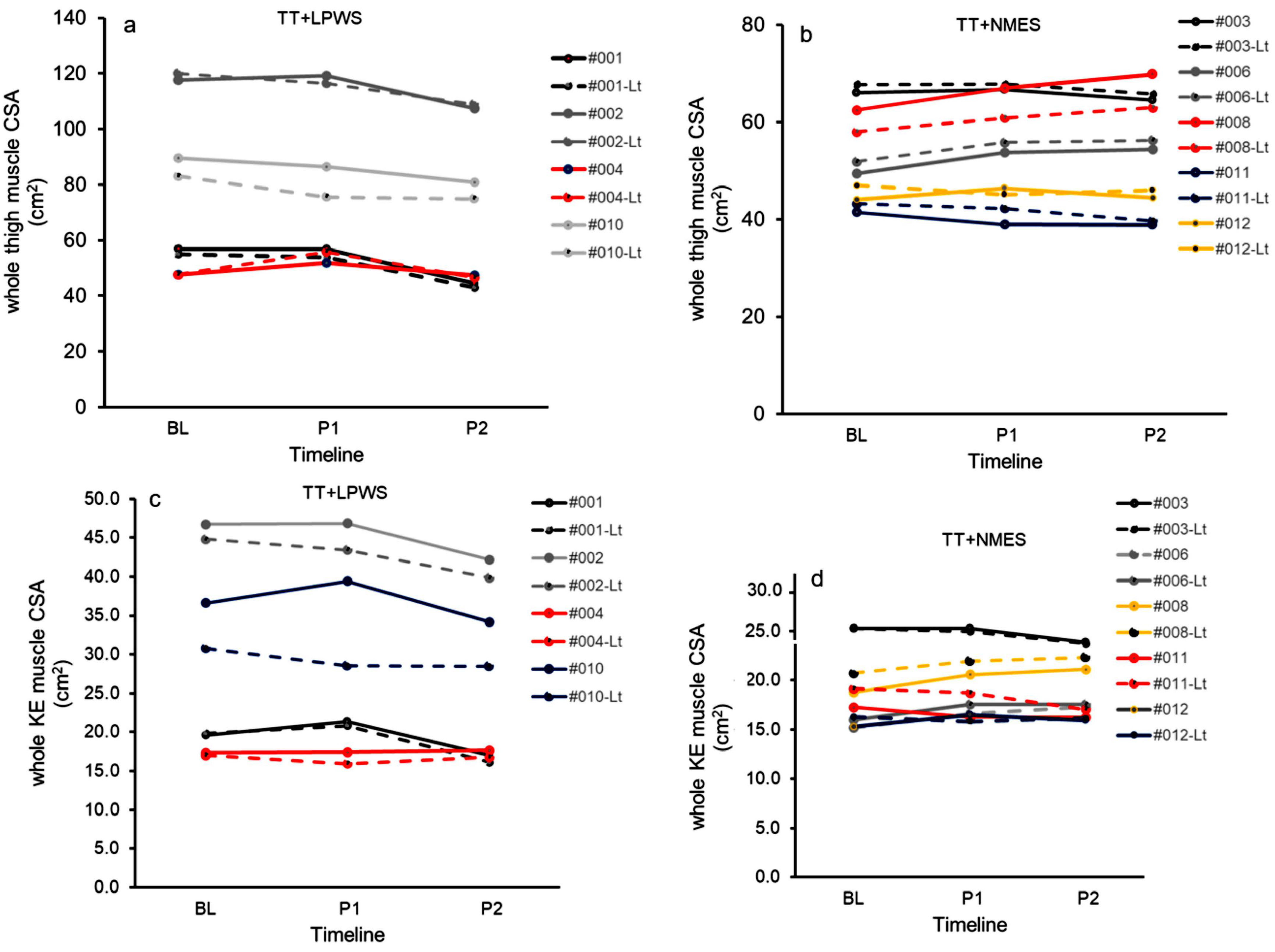

3.2.3. Effects of TT + LPWS Compared to TT + NMES on Muscle CSA

3.3. Effects on Metabolic Profile

3.3.1. RMR

3.3.2. Carbohydrate Profile

3.3.3. Lipid, Anabolic, Inflammatory Profiles

3.3.4. Real-Time Quantitative PCR (qPCR)

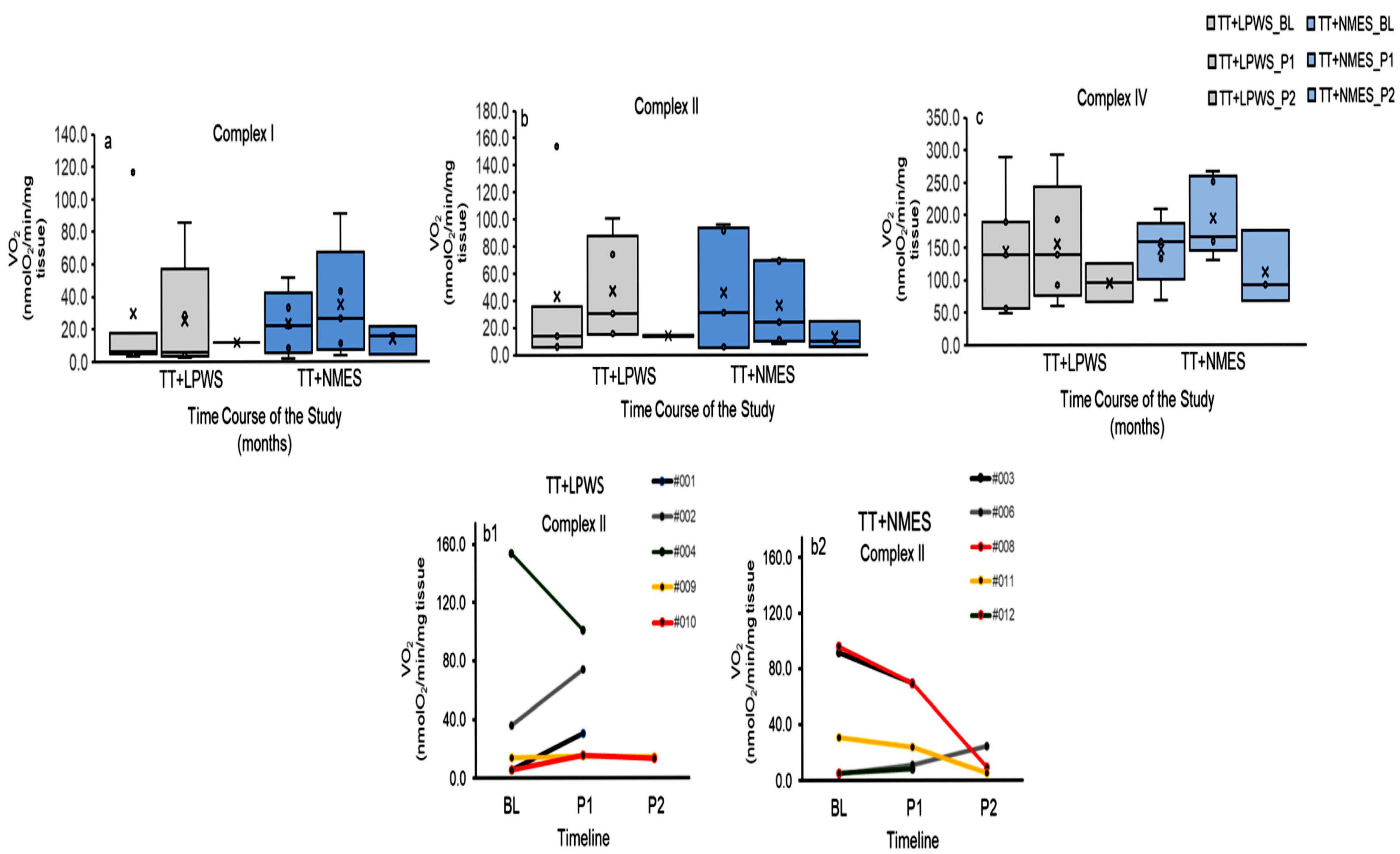

3.3.5. Mitochondrial Respiratory Activities

4. Discussion

4.1. Value of the Work to the Scientific Community

4.2. Effects on Muscle Size and Lean Mass

4.3. Effects on Secondary Outcome Variables

4.4. Practical Implications

4.5. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kern, H.; Hofer, C.; Mödlin, M.; Forstner, C.; Raschka-Högler, D.; Mayr, W.; Stöhr, H. Denervated muscles in humans: Limitations and problems of currently used functional electrical stimulation training protocols. Artif. Organs 2002, 26, 216–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carraro, U.; Kern, H. Severely Atrophic Human Muscle Fibers with Nuclear Misplacement Survive Many Years of Permanent Denervation. Eur. J. Transl. Myol. 2016, 26, 5894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alazzam, A.M.; Goldsmith, J.A.; Khalil, R.E.; Khan, M.R.; Gorgey, A.S. Denervation impacts muscle quality and knee bone mineral density after spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2023, 61, 276–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorgey, A.S.; Khalil, R.E.; Alrubaye, M.; Gill, R.; Rivers, J.; Goetz, L.L.; Cifu, D.X.; Castillo, T.; Caruso, D.; Lavis, T.D.; et al. Testosterone and long pulse width stimulation (TLPS) for denervated muscles after spinal cord injury: A study protocol of randomised clinical trial. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e064748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazarek, S.F.; Krenn, M.J.; Shah, S.B.; Mandeville, R.M.; Brown, J.M. Novel Technologies to Address the Lower Motor Neuron Injury and Augment Reconstruction in Spinal Cord Injury. Cells 2024, 13, 1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorgey, A.S.; Graham, Z.A.; Chen, Q.; Rivers, J.; Adler, R.A.; Lesnefsky, E.J.; Cardozo, C.P. Sixteen weeks of testosterone with or without evoked resistance training on protein expression, fiber hypertrophy and mitochondrial health after spinal cord injury. J. Appl. Physiol. (1985) 2020, 128, 1487–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorgey, A.S.; Lai, R.E.; Khalil, R.E.; Rivers, J.; Cardozo, C.; Chen, Q.; Lesnefsky, E.J. Neuromuscular electrical stimulation resistance training enhances oxygen uptake and ventilatory efficiency independent of mitochondrial complexes after spinal cord injury: A randomized clinical trial. J. Appl. Physiol. (1985) 2021, 131, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorgey, A.S.; Khalil, R.E.; Gill, R.; Gater, D.R.; Lavis, T.D.; Cardozo, C.P.; Adler, R.A. Low-Dose Testosterone and Evoked Resistance Exercise after Spinal Cord Injury on Cardio-Metabolic Risk Factors: An Open-Label Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Neurotrauma 2019, 36, 2631–2645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorgey, A.S.; Khalil, R.E.; Carter, W.; Ballance, B.; Gill, R.; Khan, R.; Goetz, L.; Lavis, T.; Sima, A.P.; Adler, R.A. Effects of two different paradigms of electrical stimulation exercise on cardio-metabolic risk factors after spinal cord injury. A randomized clinical trial. Front. Neurol. 2023, 14, 1254760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostovski, E.; Iversen, P.; Birkeland, K.; Torjesen, P.; Hjeltnes, N. Decreased levels of testosterone and gonadotrophins in men with long-standing tetraplegia. Spinal Cord 2008, 46, 559–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Zhao, J.; Zhao, W.; Pan, J.; Bauman, W.A.; Cardozo, C.P. Nandrolone normalizes determinants of muscle mass and fiber type after spinal cord injury. J. Neurotrauma 2012, 29, 1663–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauman, W.A.; Cirnigliaro, C.M.; La Fountaine, M.F.; Jensen, A.M.; Wecht, J.M.; Kirshblum, S.C.; Spungen, A.M. A small-scale clinical trial to determine the safety and efficacy of testosterone replacement therapy in hypogonadal men with spinal cord injury. Horm. Metab. Res. 2011, 43, 574–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nightingale, T.E.; Moore, P.; Harman, J.; Khalil, R.; Gill, R.S.; Castillo, T.; Adler, R.A.; Gorgey, A.S. Body composition changes with testosterone replacement therapy following spinal cord injury and aging: A mini review. J. Spinal Cord Med. 2018, 41, 624–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boncompagni, S. Severe muscle atrophy due to spinal cord injury can be reversed in complete absence of peripheral nerves. Eur. J. Transl. Myol. 2012, 22, 161–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, H.; Hofer, C.; Strohhofer, M.; Mayr, W.; Richter, W.; Stöhr, H. Standing up with denervated muscles in humans using functional electrical stimulation. Artif. Organs 1999, 23, 447–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofer, C.; Mayr, W.; Stöhr, H.; Unger, E.; Kern, H. A stimulator for functional activation of denervated muscles. Artif. Organs 2002, 26, 276–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, H.; Hofer, C.; Mayr, W.; Carraro, U.; Löfler, S.; Vogelauer, M.; Mödlin, M.; Forstner, C.; Bijak, M.; Rafolt, D.; et al. European Project RISE: Partners, protocols, demography. Basic Appl. Myol. Eur. J. Transl. Myol. 2009, 19, 211–216. [Google Scholar]

- Kern, H.; Carraro, U.; Adami, N.; Biral, D.; Hofer, C.; Forstner, C.; Mödlin, M.; Vogelauer, M.; Pond, A.; Boncompagni, S.; et al. Home-based functional electrical stimulation rescues permanently denervated muscles in paraplegic patients with complete lower motor neuron lesion. Neurorehabilit. Neural Repair. 2010, 24, 709–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, H.; Carraro, U. Home-Based Functional Electrical Stimulation of Human Permanent Denervated Muscles: A Narrative Review on Diagnostics, Managements, Results and Byproducts Revisited 2020. Diagnostics 2020, 10, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pond, A.; Marcante, A.; Zanato, R.; Martino, L.; Stramare, R.; Vindigni, V.; Zampieri, S.; Hofer, C.; Kern, H.; Masiero, S.; et al. History, Mechanisms and Clinical Value of Fibrillation Analyses in Muscle Denervation and Reinnervation by Single Fiber Electromyography and Dynamic Echomyography. Eur. J. Transl. Myol. 2014, 24, 3297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorgey, A.S.; Lester, R.M.; Wade, R.C.; Khalil, R.E.; Khan, R.K.; Anderson, M.L.; Castillo, T. A feasibility pilot using telehealth videoconference monitoring of home-based NMES resistance training in persons with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord Ser. Cases 2017, 3, 17039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Cheng, M.K.W.; Allison, T.A.; McSteen, B.W.; Cattle, C.J.; Lo, D.T. The Adoption of Video Visits During the COVID-19 Pandemic by VA Home Based Primary Care. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2021, 69, 318–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, D.E.; Kaidbey, K.; Boike, S.C.; Jorkasky, D.K. Use of topical corticosteroid pretreatment to reduce the incidence and severity of skin reactions associated with testosterone transdermal therapy. Clin. Ther. 1998, 20, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorgey, A.S.; Cirnigliaro, C.M.; Bauman, W.A.; Adler, R.A. Estimates of the precision of regional and whole body composition by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry in persons with chronic spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2018, 56, 987–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Scheer, J.W.; Totosy de Zepetnek, J.O.; Blauwet, C.; Brooke-Wavell, K.; Graham-Paulson, T.; Leonard, A.N.; Webborn, N.; Goosey-Tolfrey, V.L. Assessment of body composition in spinal cord injury: A scoping review. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0251142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dora, I.E.; Khalil, R.E.; Adler, R.A.; Gorgey, A.S. Basal Metabolic Rate Versus Dietary Vitamin D and Calcium Intakes and the Association with Body Composition and Bone Health After Chronic Spinal Cord Injury. Inquiry 2024, 61, 469580241278018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCauley, L.S.; Ghatas, M.P.; Sumrell, R.M.; Cirnigliaro, C.M.; Kirshblum, S.C.; Bauman, W.A.; Gorgey, A.S. Measurement of Visceral Adipose Tissue in Persons with Spinal Cord Injury by Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Dual X-Ray Absorptiometry: Generation and Application of a Predictive Equation. J. Clin. Densitom. 2020, 23, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeulen, A.; Verdonck, L.; Kaufman, J.M. A critical evaluation of simple methods for the estimation of free testosterone in serum. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1999, 84, 3666–3672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhasin, S.; Cunningham, G.R.; Hayes, F.J.; Matsumoto, A.M.; Snyder, P.J.; Swerdloff, R.S.; Montori, V.M. Testosterone therapy in men with androgen deficiency syndromes: An Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2010, 95, 2536–2559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manns, P.J.; McCubbin, J.A.; Williams, D.P. Fitness, inflammation, and the metabolic syndrome in men with paraplegia. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2005, 86, 1176–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Zhou, L.; Jensen, M.D. Errors in measuring plasma free fatty acid concentrations with a popular enzymatic colorimetric kit. Clin. Biochem. 2019, 66, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abilmona, S.M.; Sumrell, R.M.; Gill, R.S.; Adler, R.A.; Gorgey, A.S. Serum testosterone levels may influence body composition and cardiometabolic health in men with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2019, 57, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergman, R.N. Toward physiological understanding of glucose tolerance: Minimal-model approach. Diabetes 1989, 38, 1512–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuda, M.; DeFronzo, R.A. Insulin sensitivity indices obtained from oral glucose tolerance testing: Comparison with the euglycemic insulin clamp. Diabetes Care 1999, 22, 1462–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, D.R.; Hosker, J.; Rudenski, A.; Naylor, B.; Treacher, D.; Turner, R. Homeostasis model assessment: Insulin resistance and β-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia 1985, 28, 412–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolan, T.; Hands, R.E.; Bustin, S.A. Quantification of mRNA using real-time RT-PCR. Nat. Protoc. 2006, 1, 1559–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, J.; Yan, X.; Genders, A.J.; Granata, C.; Bishop, D.J. An overview of technical considerations when using quantitative real-time PCR analysis of gene expression in human exercise research. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0196438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barber, R.D.; Harmer, D.W.; Coleman, R.A.; Clark, B.J. GAPDH as a housekeeping gene: Analysis of GAPDH mRNA expression in a panel of 72 human tissues. Physiol. Genom. 2005, 21, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, Z.A.; Collier, L.; Peng, Y.; Saéz, J.C.; Bauman, W.A.; Qin, W.; Cardozo, C.P. A soluble activin receptor IIB fails to prevent muscle atrophy in a mouse model of spinal cord injury. J. Neurotrauma 2016, 33, 1128–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bigford, G.E.; Donovan, A.; Webster, M.T.; Dietrich, W.D.; Nash, M.S. Selective Myostatin Inhibition Spares Sublesional Muscle Mass and Myopenia-Related Dysfunction after Severe Spinal Cord Contusion in Mice. J. Neurotrauma 2021, 38, 3440–3455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, R.E.; Holman, M.E.; Chen, Q.; Rivers, J.; Lesnefsky, E.J.; Gorgey, A.S. Assessment of mitochondrial respiratory capacity using minimally invasive and noninvasive techniques in persons with spinal cord injury. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0265141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebanks, B.; Kwiecinska, P.; Moisoi, N.; Chakrabarti, L. A method to assess the mitochondrial respiratory capacity of complexes I and II from frozen tissue using the Oroboros O2k-FluoRespirometer. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0276147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sessa, C.; Cortes, J.; Conte, P.; Cardoso, F.; Choueiri, T.; Dummer, R.; Lorusso, P.; Ottmann, O.; Ryll, B.; Mok, T.; et al. The impact of COVID-19 on cancer care and oncology clinical research: An experts’ perspective. ESMO Open 2021, 7, 100339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elaraby, A.; Shahein, M.; Bekhet, A.H.; Perrin, P.B.; Gorgey, A.S. The COVID-19 pandemic impacts all domains of quality of life in Egyptians with spinal cord injury: A retrospective longitudinal study. Spinal Cord 2022, 60, 757–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biral, D.; Kern, H.; Adami, N.; Boncompagni, S.; Protasi, F.; Carraro, U. Atrophy-resistant fibers in permanent peripheral denervation of human skeletal muscle. Neurol. Res. 2008, 30, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, H.; Salmons, S.; Mayr, W.; Rossini, K.; Carraro, U. Recovery of long-term denervated human muscles induced by electrical stimulation. Muscle Nerve 2005, 31, 98–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salmons, S.; Ashley, Z.; Sutherland, H.; Russold, M.F.; Li, F.; Jarvis, J.C. Functional electrical stimulation of denervated muscles: Basic issues. Artif. Organs 2005, 29, 199–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha-Hikim, I.; Taylor, W.E.; Gonzalez-Cadavid, N.F.; Zheng, W.; Bhasin, S. Androgen receptor in human skeletal muscle and cultured muscle satellite cells: Up-regulation by androgen treatment. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2004, 89, 5245–5255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yarrow, J.F.; Conover, C.F.; Beggs, L.A.; Beck, D.T.; Otzel, D.M.; Balaez, A.; Combs, S.M.; Miller, J.R.; Ye, F.; Aguirre, J.I.; et al. Testosterone dose dependently prevents bone and muscle loss in rodents after spinal cord injury. J. Neurotrauma 2014, 31, 834–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, B.; Marks, D.L.; Grossberg, A.J. Diverging metabolic programmes and behaviours during states of starvation, protein malnutrition, and cachexia. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2020, 11, 1429–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waligora, A.C.; Johanson, N.A.; Hirsch, B.E. Clinical anatomy of the quadriceps femoris and extensor apparatus of the knee. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2009, 467, 3297–3306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodine, S.C.; Latres, E.; Baumhueter, S.; Lai, V.K.; Nunez, L.; Clarke, B.A.; Poueymirou, W.T.; Panaro, F.J.; Na, E.; Dharmarajan, K.; et al. Identification of ubiquitin ligases required for skeletal muscle atrophy. Science 2001, 294, 1704–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kern, H.; Carraro, U. Home-Based Functional Electrical Stimulation for Long-Term Denervated Human Muscle: History, Basics, Results and Perspectives of the Vienna Rehabilitation Strategy. Eur. J. Transl. Myol. 2014, 24, 3296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederiksen, L.; Højlund, K.; Hougaard, D.M.; Brixen, K.; Andersen, M. Testosterone therapy increased muscle mass and lipid oxidation in aging men. Age 2012, 34, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberty, M.; Mayr, W.; Bersch, I. Electrical Stimulation for Preventing Skin Injuries in Denervated Gluteal Muscles—Promising Perspectives from a Case Series and Narrative Review. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albertin, G.; Hofer, C.; Zampieri, S.; Vogelauer, M.; Löfler, S.; Ravara, B.; Guidolin, D.; Fede, C.; Incendi, D.; Porzionato, A.; et al. In complete SCI patients, long-term functional electrical stimulation of permanent denervated muscles increases epidermis thickness. Neurol. Res. 2018, 40, 277–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liang, Y.; Wang, X.; Shan, Y.; Xie, M.; Li, C.; Hong, J.; Chen, J.; Wan, G.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Effect of Modified Pharyngeal Electrical Stimulation on Patients with Severe Chronic Neurogenic Dysphagia: A Single-Arm Prospective Study. Dysphagia 2023, 38, 1128–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ifon, D.E.; Khalil, R.; Castillo, T.A.; Lavis, T.; Zhang, X.; Saha, P.K.; Chang, G.; Khan, R.M.; Adler, R.A.; Gorgey, A.S. Vitamin D Supplementation Adjunct to Home-Based Electrical Stimulation Exercise Program Versus Passive Movement Training in Chronic SCI: Individual Results From Trial Under Accrual. Top. Spinal Cord Inj. Rehabil, 2025; in press. [Google Scholar]

| ID | Gender | Age (Years) | Ethnicity | Weight (kg) | Height (cm) | LOI | BMI | TSI (Years) | AIS | Class | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TT + LPWS | 001 | M | 57 | White | 57.1 | 158.0 | T9 | 22.9 | 2 | A | Paraplegia |

| 002 | M | 22 | African American | 130.7 | 177.4 | T7 | 41.5 | 5 | C | Paraplegia | |

| 004 | M | 44 | African American | 59.2 | 173.8 | T11 | 19.6 | 19 | A | Paraplegia | |

| 007 | M | 49 | White | 80.0 | 175.3 | T10 | 26.0 | 2 | B | Paraplegia | |

| 009 | M | 39 | African American | 81.2 | 173.3 | T12 | 27.0 | 14 | A | Paraplegia | |

| 010 | M | 48 | African American | 86.9 | 170.2 | T12 | 30.0 | 6 | A | Paraplegia | |

| Mean ± SD | 43 ± 12 | 2 W:3AA | 83 ± 27 | 171 ± 7 | T7-T12 | 28 ± 8 | 8 ± 7 | 3A:1B:1C | |||

| TT + NMES | 003 | M | 41 | White | 69.8 | 171.5 | T11 | 23.7 | 2 | A | Paraplegia |

| 005 | M | 55 | White | 78.0 | 185.2 | T11 | 22.7 | 11 | A | Paraplegia | |

| 006 | M | 42 | White | 80.2 | 165.4 | T11 | 29.3 | 20 | A | Paraplegia | |

| 008 | M | 46 | White | 87.6 | 163.8 | T10 | 32.6 | 12 | A | Paraplegia | |

| 011 | M | 38 | Hispanic | 62.5 | 175.0 | T6 | 20.4 | 8 | A | Paraplegia | |

| 012 | M | 59 | African American | 65.7 | 169.0 | T11 | 23.0 | 28 | A | Paraplegia | |

| Mean ± SD | 47 ± 8 | 4W:1H:1AA | 74 ± 10 | 172 ± 8 | T6-T11 | 25 ± 5 | 14 ± 9 | 5A | |||

| p- values | 0.55 | 0.47 | 0.94 | 0.49 | 0.27 |

| TT + LPWS | TT + NMES | p-Values | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caloric intake (kcal/day) | Caloric intake Wk 1 and 2 | 1332 ± 450 | 2272 ± 735 | 0.05 |

| Caloric intake Wk 23–24 | 1514 ± 952 | 1800 ± 411 | 0.8 | |

| Caloric intake Wk 47–48 | 1368 ± 530.0 | 1858 ± 1069 | 0.3 | |

| % Fat | % Fat Wk 1 and 2 | 34.1 ± 6.1 | 37.6 ± 9.3 | 0.5 |

| % Fat Wk 23–24 | 37.1 ± 4.4 | 40.0 ± 3.0 | 0.4 | |

| % Fat Wk 47–48 | 39.0 ± 4.8 | 32.0 ± 13.0 | 0.7 | |

| % Carbohydrate | % Carbohydrate Wk 1 and 2 | 45.6 ± 6.3 | 40.1 ± 9.5 | 0.3 |

| % Carbohydrate Wk 23–24 | 42.8 ± 4.0 | 39.2 ± 2.1 | 0.2 | |

| % Carbohydrate Wk 47–48 | 42.0 ± 3.0 | 47.4 ± 19.1 | 0.4 | |

| % Protein | % Protein Wk 1 and 2 | 18.2 ± 2.7 | 19.3 ± 3.2 | 0.6 |

| % Protein Wk 23–24 | 17.3 ± 5.2 | 20.2 ± 3.4 | 0.4 | |

| % Protein Wk 47–48 | 19.3 ± 1.8 | 20.5 ± 6.5 | 0.5 | |

| Fat (g) | Total Fat (g) Wk 1 and 2 | 50.3 ± 16.1 | 92.8 ± 35.0 | 0.05 |

| Total Fat (g) Wk 23–24 | 82.4 ± 17.0 | 81.8 ± 15.5 | 0.5 | |

| Total Fat (g) Wk 47–48 | 62.7 ± 30.0 | 59.3 ± 11.0 | 0.1 | |

| Carbohydrate (g) | Total Carbohydrate (g) Wk 1 and 2 | 155.0 ± 64.4 | 250.4 ± 116.8 | 0.2 |

| Total Carbohydrate (g) Wk 23–24 | 201.5 ± 71.6 | 181.6 ± 53.0 | 0.6 | |

| Total Carbohydrate (g) Wk 47–48 | 136.4 ± 45.1 | 241.1 ± 232.2 | 0.4 | |

| Protein (g) | Total Protein (g) Wk 1 and 2 | 57.1 ± 23.2 | 104.2 ± 24.7 | 0.01 |

| Total Protein (g) Wk 23–24 | 74.2 ± 23.3 | 89.0 ± 26.5 | 0.4 | |

| Total Protein (g) Wk 47–48 | 65.2 ± 18.4 | 96.0 ± 11.2 | 0.04 |

| TT + LPWS (n = 5) | TT + NMES (n = 5) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Post-Int1 | Post-Int 2 | Baseline | Post-Int1 | Post-Int 2 | ||||

| Anthropometrics | Supine Waist circumference | 91.0 ± 14.0 | 86.0 ± 8.0 | 84.0 ± 9.0 | 87.0 ± 9.0 | 86.0 ± 9.0 | 88.0 ± 9.0 | ||

| Supine Abdominal circumference (cm) | 93.0 ± 9.0 | 91.0 ± 9.0 | 94.0 ± 13.0 | 92.0 ± 9.0 | 90.0 ± 12.0 | 92.0 ± 12.0 | |||

| Supine Hip circumference (cm) | 105 ± 20.0 | 104.0 ± 18.0 | 94.0 ± 9.0 | 95.0 ± 9.0 | 96.0 ± 8.0 | 98.0 ± 10.0 | |||

| Seated Waist circumference (cm) | 90.0 ± 11.0 | 88 ± 11.0 | 86.0 ± 10.0 | 89.0 ± 9.0 | 90.0 ± 10.0 | 88.0 ± 11.0 | |||

| Seated Abdominal circumference (cm) | 101.0 ± 14.0 | 99.0 ± 12.0 | 97.0 ± 13.0 | 98.0 ± 7.0 | 98.0 ± 9.0 | 100 ± 11.0 | |||

| Supine Thigh circumference (cm) | 50 ± 13 | 47 ± 14 | 42 ± 7.0 | 40 ± 4.0 | 40 ± 5.0 | 40 ± 5.0 | |||

| Seated Calf circumference (cm) | 30.0 ± 7.0 | 28.0 ± 5.0 | 28.0 ± 2.0 | 29.0 ± 3.0 | 29.0 ± 4.0 | 30 ± 3.0 | |||

| Body composition | |||||||||

| DXA Arm | %Fat mass | 24.2 ± 7.0 | 23.6 ± 7.0 | 23.7 ± 4.0 | 22.6 ± 3.5 | 22.6 ± 3.6 | 22.6 ± 3.6 | ||

| Fat mass (g) | 2814 ± 1314 | 2897 ± 1589 | 2201 ± 935 | 2281 ± 749 | 2401 ± 865 | 2332 ± 986 | |||

| Lean mass (g) | 8274 ± 3037 | 8522 ± 3267 | 7292 ± 2216 | 7259 ± 1185 | 7569 ± 1333 | 7246 ± 2018 | |||

| BMC (g) | 462 ± 98 | 459 ± 95 | 426 ± 98 | 405 ± 56 | 415 ± 63 | 423 ± 69 | |||

| Lower extremity | %Fat mass | 40.0 ± 8.2 | 42.3 ± 6.0 | 42.4 ± 4.0 | 43.4 ± 3.6 | 41.5 ± 3.7 | 42.5 ± 4.0 | ||

| Fat mass (g) | 8449 ± 4634 | 9058 ± 3600 | 8793 ± 3035 | 8247 ± 1727 | 7763 ± 2107 | 7753 ± 2444 | |||

| Lean mass (g) | 11,486 ± 6109 | 11,853 ± 5757 | 9882 ± 3025 | 9963 ± 1455 | 10,038 ± 1895 | 10,883 ± 1539 | |||

| BMC (g) | 669 ± 370 | 696 ± 345 | 665 ± 261 | 710 ± 221 | 698 ± 206 | 784 ± 221 | |||

| Trunk | %Fat mass | 39.3 ± 10.0 | 36.3 ± 12.0 | 35.7 ± 11.3 | 40.7 ± 5.0 | 39.2 ± 7.7 | 37.9 ± 7.2 | ||

| Fat mass (g) | 17,997 ± 8022 | 15,326 ± 8051 | 13,758 ± 6085 | *? | 15,957 ± 5051 | 15,620 ± 5989 | 16,020 ± 5218 | X? | |

| Lean mass (g) | 25,855 ± 7225 | 24,724 ± 6207 | 25,246 ± 5069 | 21,724 ± 2445 | 22,304 ± 3147 | 22,425 ± 3482 | |||

| BMC (g) | 883 ± 359 | 840 ± 413 | 584 ± 160 | 759 ± 183 | 743 ± 179 | 797 ± 151 | |||

| Android | %Fat mass | 41.3 ± 14.4 | 38.4 ± 15.7 | 37.5 ± 8.5 | 43.2 ± 5.4 | 41.8 ± 9.1 | 43.5 ± 3.7 | ||

| Fat mass (g) | 3026 ± 1563 | 2457 ± 1376 | 2632 ± 1162 | 2682 ± 818 | 2637 ± 1071 | 2724 ± 870 | |||

| Lean mass (g) | 3911 ± 966 | 3579 ± 856 | 3999 ± 729 | 3377 ± 472 | 3453 ± 662 | 3272 ± 838 | X | ||

| BMC (g) | 58 ± 21 | 53 ± 20 | 42 ± 11 | 53 ± 16 | 53 ± 17 | 55 ± 6 | |||

| Gynoid | %Fat mass | 43.4 ± 11.3 | 43.1 ± 8.9 | 45.2 ± 5.7 | 48.2 ± 3.7 | 47.3 ± 3.2 | 45.1 ± 6.5 | ||

| Fat mass (g) | 4615 ± 2833 | 4764 ± 2475 | 4170 ± 1200 | 4156 ± 1361 | 4117 ± 1619 | 4103 ± 1753 | |||

| Lean mass (g) | 5459 ± 2623 | 5928 ± 2700 | 4601 ± 654 | 4206 ± 1172 | 4226 ± 1278 | 4849 ± 606 | |||

| BMC (g) | 176 ± 96 | 176 ± 112 | 165 ± 88 | 203 ± 57 | 198 ± 55 | 195 ± 66 | |||

| Total | %Fat mass | 36.3 ± 7.7 | 35.0 ± 8.5 | 35.3 ± 6.0 | 37.5 ± 4.0 | 36.2 ± 5.5 | 36.3 ± 4.5 | ||

| Fat mass (g) | 303,08 ± 12,999 | 28,302 ± 13,105 | 26,778 ± 10,468 | 27,451 ± 7282 | 26,777 ± 8783 | 27,629 ± 7914 | |||

| Lean mass (g) | 49,261 ± 15,043 | 48696 ± 14,529 | 43,857 ± 8828 | 42,282 ± 4255 | 43,306 ± 5756 | 43,098 ± 6716 | |||

| BMC (g) | 2608 ± 822 | 2597 ± 871 | 2238 ± 375 | 2378 ± 411 | 2359 ± 408 | 2320 ± 450 | |||

| TT + LPWS (n = 4) | TT + NMES (n = 5) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Post-Int1 | Post-Int 2 | Baseline | Post-Int1 | Post-Int 2 | ||||

| Muscle CSA | Rt. Whole thigh muscle CSA (cm2) | 78.0 ± 32.0 | 79.0 ± 31.0 | 70.0 ± 30.0 | * | 53.0 ± 11.0 | 54.5 ± 12.4 | 54.4 ± 13.0 | X |

| Lt. Whole thigh muscle CSA (cm2) | 76.5 ± 33.0 | 75.5 ± 29.0 | 68.4 ± 30.6 | *? | 53.5 ± 10.0 | 54.4 ± 11 | 54.0 ± 11.0 | X? | |

| Rt. Absolute thigh muscle CSA (cm2) | 48.0 ± 13.0 | 52.4 ± 17.0 | 46.5 ± 15.0 | 31.0 ± 13.0 | 36.5 ± 10.0 | 40.0 ± 11.4 | |||

| Lt. Absolute thigh muscle CSA (cm2) | 47.0 ± 18.0 | 50.0 ± 17.0 | 43.0 ± 16.0 | 35.0 ± 12.0 | 33.3 ± 17.0 | 35.0 ± 11.0 | |||

| Rt. Adjusted Absolute muscle CSA | 0.65 ± 0.13 | 0.68 ± 0.07 | 0.69 ± 0.17 | 0.59 ± 0.19 | 0.67 ± 0.14 | 0.72 ± 0.06 | |||

| Lt. Adjusted Absolute muscle CSA | 0.62 ± 0.05 | 0.67 ± 0.05 | 0.64 ± 0.05 | *? | 0.62 ± 0.19 | 0.70 ± 0.11 | 0.62 ± 0.16 | ||

| Rt. Whole KE muscle CSA (cm2) | 30.0 ± 14.0 | 31.3 ± 14.0 | 28.0 ± 12.5 | 18.3 ± 4.0 | 19.0 ± 4.0 | 19.0 ± 3.5 | X? | ||

| Lt. Whole KE muscle CSA (cm2) | 28.0 ± 13.0 | 27.2 ± 12.0 | 25.3 ± 11.2 | 19.5 ± 4.0 | 20.0 ± 4.0 | 19.4 ± 3.4 | |||

| Rt. Absolute KE muscle (cm2) | 20.0 ± 5.0 | 22.0 ± 6.7 | 19.0 ± 5.7 | 10.0 ± 8.0 | 12.3 ± 5.6# | 13.0 ± 4.4 | # | ||

| Lt. Absolute KE muscle (cm2) | 18.5 ± 4.4 | 19.3 ± 5.0 | 16.2 ± 3.2 | 13.3 ± 7.0 | 13.2 ± 6.3 | 13.2 ± 5.0 | |||

| Rt. Adjusted Absolute KE CSA | 0.72 ± 0.17 | 0.75 ± 0.16 | 0.74 ± 0.17 | 0.49 ± 0.34 | 0.65 ± 0.26 | 0.68 ± 0.14 | |||

| Lt. Adjusted Absolute KE CSA | 0.71 ± 0.17 | 0.75 ± 0.14 | 0.70 ± 0.18 | 0.66 ± 0.28 | 0.64 ± 0.24 | 0.68 ± 0.21 | |||

| Individual Muscle CSA | Rt. Vasti m CSA (cm2) | 27.0 ± 13.0 | 27.0 ± 13.2 | 25.0 ± 11.0 | 15.5 ± 4.0 | 16.3 ± 4.0 | 16.4 ± 3.0 | ||

| Lt. Vasti m CSA (cm2) | 25.0 ± 11.4 | 23.0 ± 11.3 | 22.0 ± 10 | 17.0 ± 3.3 | 17.2 ± 3.3 | 16.5 ± 3.0 | |||

| Rt. Adjusted Vasti m to whole KE | 0.88 ± 0.02 | 0.85 ± 0.06 | 0.89 ± 0.01 | 0.84 ± 0.04 | 0.85 ± 0.02 | 0.86 ± 0.02 | |||

| Lt. Adjusted Vasti m to whole KE | |||||||||

| Rt. RF m CSA (cm2) | 2.4 ± 1.0 | 3.0 ± 1.3 | 2.3 ± 1.0 | * | 2.0 ± 0.5 | 2.2 ± 0.3 | 2.0 ± 0.3 | ||

| Lt. RF m CSA (cm2) | 2.5 ± 1.0 | 3.2 ± 1.2 | 3.0 ± 1.1 | 2.0 ± 0.5 | 2.1 ± 0.3 | 2.2 ± 0.4 | |||

| Rt. Adjusted RF m to whole KE | 0.084 ± 0.02 | 0.10 ± 0.04 | 0.09 ± 0.02 | * | 0.11 ± 0.01 | 0.12 ± 0.02 | 0.11 ± 0.01 | ||

| Lt. Adjusted RF m to whole KE | |||||||||

| Rt. Post-Medial Comp. Muscle (cm2) | 47.0 ± 18.0 | 46.3 ± 17.0 | 41.6 ± 18.0 | *? | 33.5 ± 8.0 | 34.5 ± 9.3 | 35.0 ± 10.2 | X, 0.016 | |

| Lt. Post-Medial Comp. Muscle (cm2) | 47.4 ± 20.0 | 47.2 ± 17.2 | 40.3 ± 17.0 | * | 33.2 ± 7.0 | 34.0 ± 8.0 | 34.0 ± 8.3 | X, 0.006 | |

| Rt. Adjusted Post-Medial Comp. to whole thigh Muscle | 0.61 ± 0.02 | 0.60 ± 0.05 | 0.60 ± 0.02 | 0.63 ± 0.05 | 0.63 ± 0.05 | 0.63 ± 0.05 | |||

| Lt. Adjusted Post-Medial Comp. to whole thigh Muscle | 0.63 ± 0.006 | 0.63 ± 0.05 | 0.60 ± 0.03 | 0.62 ± 0.05 | 0.62 ± 0.04 | 0.62 ± 0.05 | |||

| Intramuscular fat (IMF) | Rt. Whole thigh IMF (cm2) | 36.0 ± 13.0 | 32.0 ± 7.5 | 31.0 ± 6.0 | 42.0 ± 19.0 | 33.0 ± 13.3 | 28.0 ± 6.0 | ||

| Lt. Whole thigh IMF | 38.0 ± 5.5 | 32.5 ± 6.0 | 33.0 ± 6.4 | 38.0 ± 19.3 | 30.0 ± 11.0 | 38.0 ± 16.0 | |||

| Rt. Knee IMF (cm2) | 10.3 ± 10.0 | 9.3 ± 9.2 | 7.2 ± 5.0 | 8.7 ± 5.2 | 6.7 ± 5.4 | 6.0 ± 2.6 | |||

| Lt. Knee IMF (cm2) | 10.0 ± 10.0 | 8.0 ± 8.0 | 8.9 ± 8.3 | 6.2 ± 4.7 | 6.6 ± 3.7 | 6.0 ± 4.0 | |||

| Time Since Injury (TSI; Years) | Whole Thigh Muscle CSA (cm2) | Absolute Whole Thigh Muscle CSA (cm2) | Whole KE Muscle CSA (cm2) | Absolute KE Muscle CSA (cm2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Post-intervention 1 (P1) | Right P1: r2 = 0.33, p = 0.1 (+ve, n = 9) | Right P1: r2 = 0.05, p = 0.6 (+ve, n = 9) | Right P1: r2 = 0.006, p = 0.85 (+ve, n = 9) | Right P1: r2 = 0.32, p = 0.18 (+ve, n = 9) |

| Left P1: r2 = 0.18, p = 0.24 (+ve, n = 9) | Left P1: r2 = 0.63, p = 0.02 (+ve, n = 9) | Left P1: r2 = 0.025, p = 0.7 (+ve, n = 9) | Left P1: r2 = 0.16, p = 0.32 (+ve, n = 8) | |

| Post-intervention 2 (P2) | Right P2: r2 = 0.47, p = 0.06 (+ve, n = 8) *? | Right P2: r2 = 0.37, p = 0.08 (+ve, n = 9) *? | Right P2: r2 = 0.47, p = 0.04 (+ve, n = 9) * | Right P2: r2 = 0.55, p = 0.021 (+ve, n = 9) * |

| Left P2: r2 = 0.77, p = 0.004 (+ve, n = 8) * | Left P2: r2 = 0.24, p = 0.18 (+ve, n = 9) | Left P2: r2 = 0.46, p = 0.045 (+ve, n = 9) * | Left P2: r2 = 0.29, p = 0.13 (+ve, n = 9) |

| TT + LPWS | TT + NMES | p-Values Within Groups | p-Values Between Groups | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMR (kcal/day) | Baseline | 1634 ± 416 | 1580 ± 383 | ||

| Post-intervention 1 | 1564 ± 428 | 1424 ± 251 | |||

| Post-intervention 2 | 1530 ± 472 | 1391 ± 275 | 0.3 | 0.6 | |

| Adjusted RMR (kcal/day) | Baseline | 33.6 ± 2.7 | 33.1 ± 2.7 | ||

| Post-intervention 1 | 32.6 ± 4.3 | 32.6 ± 2.2 | |||

| Post-intervention 2 | 35.4 ± 9.8 | 32.2 ± 1.5 | 0.9 | 0.5 | |

| Sg [min−1] | Baseline | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 0.04 ± 0.04 | ||

| Post-intervention 1 | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 0.03 ± 0.01 | 0.4 | 0.03 | |

| Si [(mu/L)−1.min−1] | Baseline | 6.3 ± 5.5 | 4.6 ± 5.0 | ||

| Post-intervention 1 | 4.7 ± 5.7 | 3.8 ± 3.9 | 0.9 | 0.9 | |

| TNFα (pg/mL) | Baseline | 18.3 ± 13.6 | 15.7 ± 16.9 | ||

| Post-intervention 1 | 20.1 ± 8.8 | 13.4 ± 4.2 | |||

| Post-intervention 2 | 16.4 ± 11.6 | 11.8 ± 5.9 | 0.7 | 0.2 | |

| IGF-1 (ng/mL) | Baseline | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 0.9 ± 0.3 | ||

| Post-intervention 1 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 0.9 ± 0.2 | |||

| Post-intervention 2 | 0.8 ± 0.01 | 0.9 ± 0.01 | 0.9 | 0.3 | |

| IGFBP3 (ng/mL) | Baseline | 20.3 ± 5.7 | 22.4 ± 5.3 | ||

| Post-intervention 1 | 17.8 ± 4.9 | 21.3 ± 8.5 | |||

| Post-intervention 2 | 20.9 ± 1.6 | 22.4 ± 2.5 | 0.3 | 0.4 | |

| CRP (ng/mL) | Baseline | 332.6 ± 338.7 | 141.8 ± 168.1 | ||

| Post-intervention 1 | 232.7 ± 225.9 | 167.9 ± 191.8 | |||

| Post-intervention 2 | 154.6 ± 118.4 | 141.7 ± 138.9 | 0.8 | 0.4 | |

| LDL mg/dL | Baseline | 86.4 ± 48.0 | 99.9 ± 32.0 | ||

| Post-intervention 1 | 89.8 ± 55.1 | 86.6 ± 39.3 | |||

| Post-intervention 2 | 109.4 ± 17.5 | 100.3 ± 35.2 | 0.3 | 0.9 | |

| HDL mg/dL | Baseline | 47.8 ± 7.2 | 44.8 ± 11.6 | ||

| Post-intervention 1 | 44.2 ± 6.9 | 44.0 ± 12.0 | |||

| Post-intervention 2 | 46.0 ± 8.9 | 46.8 ± 10.3 | 0.4 | 0.9 | |

| Total Cholesterol mg/dL | Baseline | 151.0 ± 52.9 | 169.0 ± 25.1 | ||

| Post-intervention 1 | 150.6 ± 64.8 | 150.6 ± 40.7 | |||

| Post-intervention 2 | 176.1 ± 30.8 | 179.9 ± 22.9 | 0.3 | 0.7 | |

| Triglyceride mg/dL | Baseline | 82.8 ± 19.5 | 121.6 ± 58.9 | ||

| Post-intervention 1 | 81.8 ± 21.7 | 99.8 ± 25.4 | |||

| Post-intervention 2 | 90.9 ± 24.2 | 98.1 ± 29.4 | 0.6 | 0.2 | |

| % Hemoglobin A1C | Baseline | 5.7 ± 0.6 | 5.4 ± 0.5 | ||

| Post-intervention 1 | 5.7 ± 0.8 | 5.5 ± 0.5 | |||

| Post-intervention 2 | 5.7 ± 0.4 | 5.3 ± 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.2 | |

| Total Testosterone ng/dL | Baseline | 525.8 ± 212.7 | 330.0 ± 111.6 | ||

| Post-intervention 1 | 471.0 ± 234.0 | 291.8 ± 141.5 | |||

| Post-intervention 2 | 381.8 ± 251.9 | 263.7 ± 168.5 | 0.2 | 0.2 | |

| Free Fatty Acid (mmol/L) | Baseline | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 0.5 ± 0.2 | ||

| Post-intervention 1 | 0.7 ± 0.2 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | |||

| Post-intervention 2 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 0.6 | 0.1 | |

| Albumin (g/dL) | Baseline | 3.9 ± 0.2 | 4.2 ± 0.1 | ||

| Post-intervention 1 | 3.9 ± 0.3 | 4.2 ± 0.1 | |||

| Post-intervention 2 | 17.8 ± 15.7 | 10.7 ± 13.1 | 0.1 | 0.6 | |

| Prostate-Specific Antigen (ng/mL) | Baseline | 0.9 ± 0.9 | 1.6 ± 0.3 | ||

| Post-intervention 1 | 1.3 ± 1.1 | 1.2 ± 0.7 | |||

| Post-intervention 2 | 1.0 ± 0.7 | 1.5 ± 1.1 | 0.9 | 0.5 | |

| Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin (nmol/L) | Baseline | 45.6 ± 19.6 | 18.6 ± 6.1 | ||

| Post-intervention 1 | 43.4 ± 19.8 | 18.2 ± 6.8 | |||

| Post-intervention 2 | 41.5 ± 9.1 | 24.6 ± 5.7 | 0.8 | 0.01 | |

| Free Testosterone (ng/dL) | Baseline | 7.4 ± 2.8 | 9.1 ± 3.3 | ||

| Post-intervention 1 | 7.5 ± 4.1 | 7.9 ± 3.5 | |||

| Post-intervention 2 | 6.7 ± 4.9 | 5.5 ± 4.3 | 0.0 | 0.9 | |

| Bioavailable Testosterone (ng/dL) | Baseline | 167.2 ± 58.4 | 203.2 ± 70.7 | ||

| Post-intervention 1 | 148.4 ± 81.2 | 175.8 ± 81.5 | |||

| Post-intervention 2 | 155.5 ± 109.7 | 132.5 ± 104.5 | 0.2 | 0.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gorgey, A.S.; Khalil, R.E.; Alazzam, A.; Gill, R.; Rivers, J.; Caruso, D.; Garten, R.; Redden, J.T.; McClure, M.J.; Castillo, T.; et al. Testosterone and Long-Pulse-Width Stimulation (TLPS) on Denervated Muscles and Cardio-Metabolic Risk Factors After Spinal Cord Injury: A Pilot Randomized Trial. Cells 2025, 14, 1974. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14241974

Gorgey AS, Khalil RE, Alazzam A, Gill R, Rivers J, Caruso D, Garten R, Redden JT, McClure MJ, Castillo T, et al. Testosterone and Long-Pulse-Width Stimulation (TLPS) on Denervated Muscles and Cardio-Metabolic Risk Factors After Spinal Cord Injury: A Pilot Randomized Trial. Cells. 2025; 14(24):1974. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14241974

Chicago/Turabian StyleGorgey, Ashraf S., Refka E. Khalil, Ahmad Alazzam, Ranjodh Gill, Jeannie Rivers, Deborah Caruso, Ryan Garten, James T. Redden, Michael J. McClure, Teodoro Castillo, and et al. 2025. "Testosterone and Long-Pulse-Width Stimulation (TLPS) on Denervated Muscles and Cardio-Metabolic Risk Factors After Spinal Cord Injury: A Pilot Randomized Trial" Cells 14, no. 24: 1974. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14241974

APA StyleGorgey, A. S., Khalil, R. E., Alazzam, A., Gill, R., Rivers, J., Caruso, D., Garten, R., Redden, J. T., McClure, M. J., Castillo, T., Goetz, L., Chen, Q., Lesnefsky, E. J., & Adler, R. A. (2025). Testosterone and Long-Pulse-Width Stimulation (TLPS) on Denervated Muscles and Cardio-Metabolic Risk Factors After Spinal Cord Injury: A Pilot Randomized Trial. Cells, 14(24), 1974. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14241974