Design and Synthesis of New Quinoxaline Analogs to Regenerate Sensory Auditory Hair Cells

Highlights

- Two new lead quinoxaline derivatives promote measurable auditory supporting cell proliferation and the generation of new sensory hair cells in zebrafish neuromasts and mouse organs of Corti without inducing apoptosis or impacting the function of the sensory hair cells.

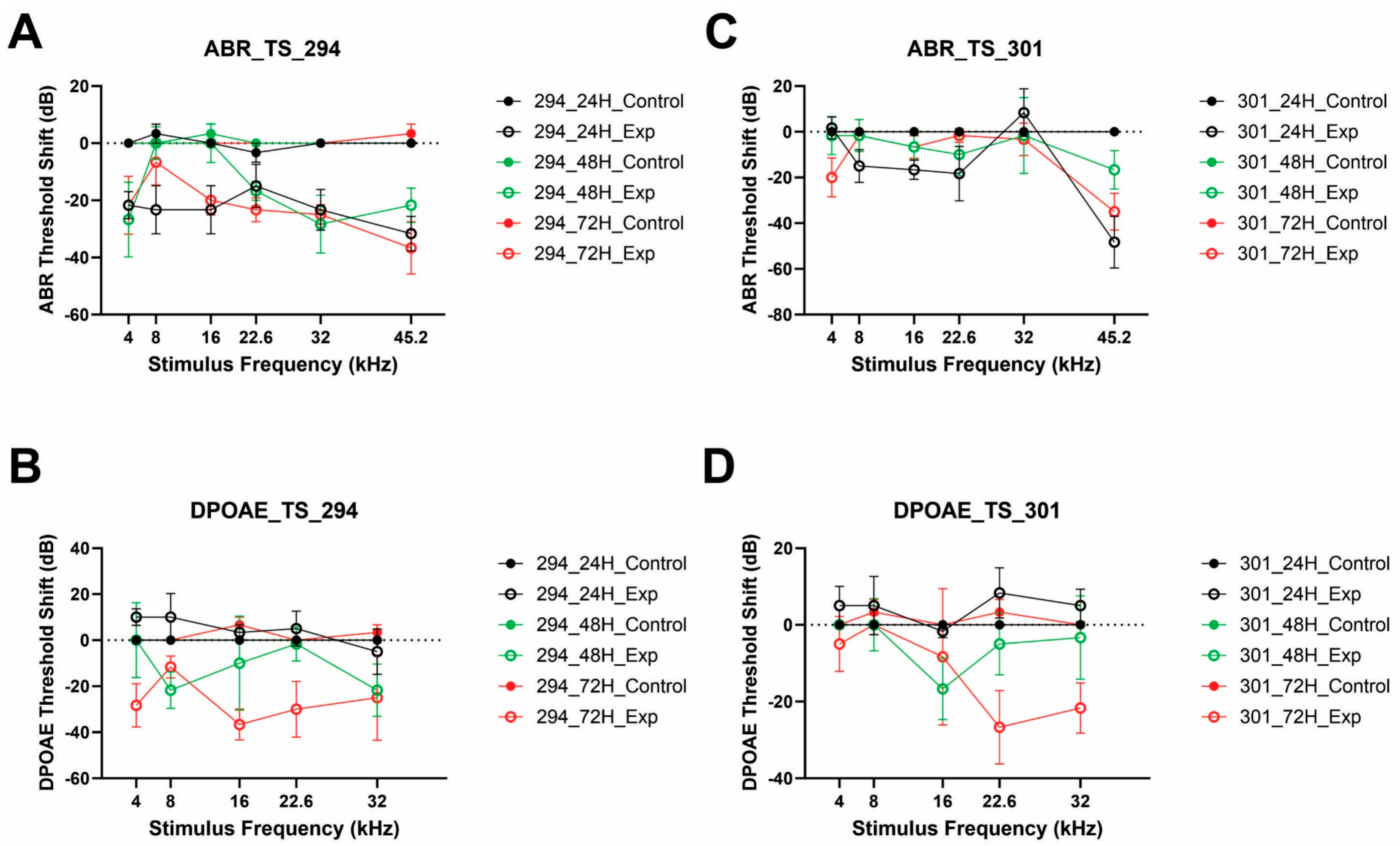

- Improved hearing in mice at certain treatment doses, along with observed proliferation patterns, indicates compound-specific effects and suggests the engagement of canonical pro-growth pathways, including Wnt/β-catenin and MAP3K1-IKK-NF-κB.

- Enhancing the proliferation of auditory supporting cells through pharmacological modulation could improve the mitotic regenerative capacity of mammalian sensory epithelia, ultimately creating more favorable conditions for future strategies aimed at regenerating auditory hair cells.

- These findings highlight two quinoxaline derivatives as promising candidates for further exploration into their role in treatment pathways, long-term safety, and potential use in regeneration-based strategies for sensorineural hearing loss.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. General Chemistry Methods and Instrumentation

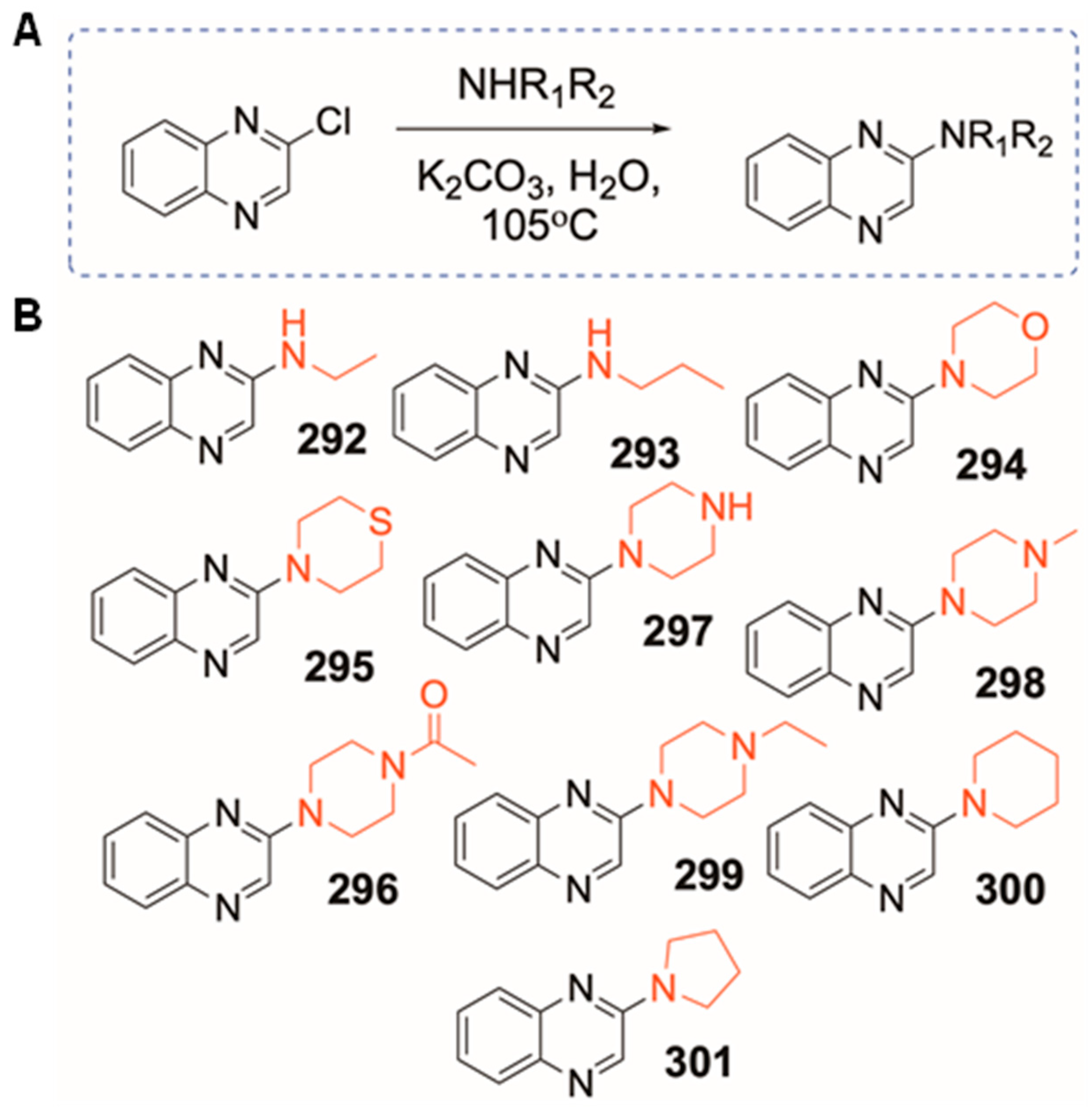

2.2. General Synthetic Method for Straight-Chain 2-Aminoquinoxaline Analogs

- 2-(ethylamine)-quinoxaline (292): 7.6 mg (7.2%); 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ = 1.41 (t, J = 8 Hz, 3H), 3.64 (q, J = 8 Hz, 2H), 7.46 (t, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 7.50 (t, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 7.75 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 7.93 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 8.40 (s, 1H). ESI-MS calculated for C10H12N3: 174.2, found: 175.0 [M+H]+.

- 2-(propylamine)-quinoxaline (293): 12.0 mg (10.5%); 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ = 0.97 (t, J = 8 Hz, 3H), 1.65 (sex, J = 8 Hz, 2H), 3.44 (q, J = 8 Hz, 2H), 7.30 (t, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 7.49 (t, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 7.61 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 7.78 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 8.15 (s, 1H). ESI-MS calculated for C11H14N3: 188.3, found: 188.9 [M+H]+.

2.3. General Synthetic Method for Cyclic 2-Aminoquinoxaline Analogs

- 2-(morpholine)-quinoxaline (294): 13.6 mg (10.4%); 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ = 3.79–3.81 (m, 4H), 3.89–3.91 (m, 4H), 7.45 (t, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 7.62 (t, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 7.74 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 7.91 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 8.60 (s, 1H). ESI-MS calculated for C12H14N3O: 216.3, found: 216.9 [M+H]+.

- 2-(thiomorpholine)-quinoxaline (295): 11.0 mg (7.8%); 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ = 2.77–2.80 (m, 4H), 4.17–4.20 (m, 4H), 7.43 (t, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 7.60 (t, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 7.72 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 7.90 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 8.56 (s, 1H). ESI-MS calculated for C12H14N3S: 232.3, found: 233.0 [M+H]+.

- 2-(4-acetylpiperazine)-quinoxaline (296): 14.8 mg (9.5%); 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ = 2.19 (s, 3H), 3.66–3.69 (m, 2H), 3.78–3.85 (m, 4H), 3.85–3.90 (m, 2H), 7.46 (t, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 7.63 (t, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 7.73 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 7.92 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 8.62 (s, 1H). ESI-MS calculated for C14H17N4O: 257.3, found: 258.0 [M+H]+.

- 2-(piperazine)-quinoxaline (297): 12.3 mg (9.4%); 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ = 2.95 (s, 2H), 3.07–3.09 (m, 4H), 3.80–3.83 (m, 4H), 7.42 (t, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 7.60 (t, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 7.69 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 7.89 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 8.60 (s, 1H). ESI-MS calculated for C12H15N4: 215.3, found: 216.0 [M+H]+.

- 2-(4-methylpiperazine)-quinoxaline (298): 10.5 mg (7.6%); 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ = 2.42 (s, 3H), 2.62–2.65 (m, 4H), 3.85–3.88 (m, 4H), 7.42 (t, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 7.60 (t, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 7.70 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 7.89 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 8.60 (s, 1H). ESI-MS calculated for C13H17N4: 229.3, found: 230.0 [M+H]+.

- 2-(4-ethylpiperazine)-quinoxaline (299): 11.9 mg (8.1%); 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ = 1.18 (t, J = 8 Hz, 3H), 2.53 (q, J = 8 Hz, 2H), 2.64–2.67 (m, 4H), 3.85–3.88 (m, 4H), 7.41 (t, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 7.59 (t, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 7.69 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 7.88 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 8.60 (s, 1H). ESI-MS calculated for C14H19N4: 243.3, found: 243.9 [M+H]+.

- 2-(piperidine)-quinoxaline (300): 24.2 mg (18.7%); 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ = 1.74 (br, 6H), 3.80 (br, 4H), 7.39 (t, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 7.58 (t, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 7,71 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 7.87 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 8.61 (s, 1H). ESI-MS calculated for C13H16N3: 214.3, found: 214.9 [M+H]+.

- 2-(pyrrolidine)-quinoxaline (301): 12.5 mg (10.3%); 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ = 2.08–2.12 (m, 4H), 3.69–3.72 (m, 4H), 7.36 (t, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 7.58 (t, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 7.72 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 7.88 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 8.37 (s, 1H). ESI-MS calculated for C12H14N3: 200.3, found: 200.7 [M+H]+.

2.4. Cell Culture

2.5. Animals

2.6. Zebrafish

2.7. Mice

2.8. Immunolabeling

2.9. Proliferation and Apoptosis Assays

2.10. FM1-43

2.11. Confocal Imaging

2.12. Auditory Function

2.13. ABR

2.14. DPOAE Recording and Data Analysis

2.15. In Vitro Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMETox)

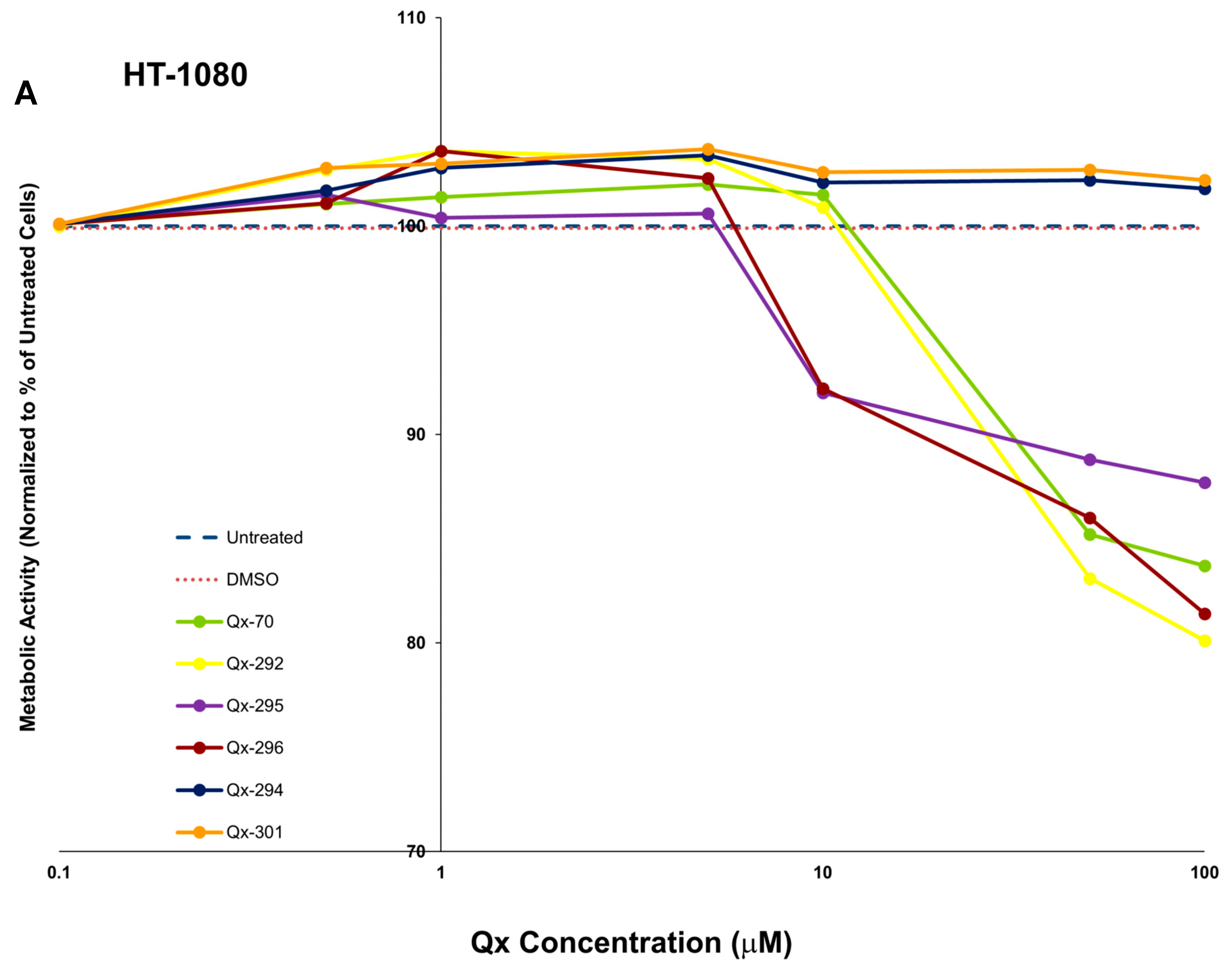

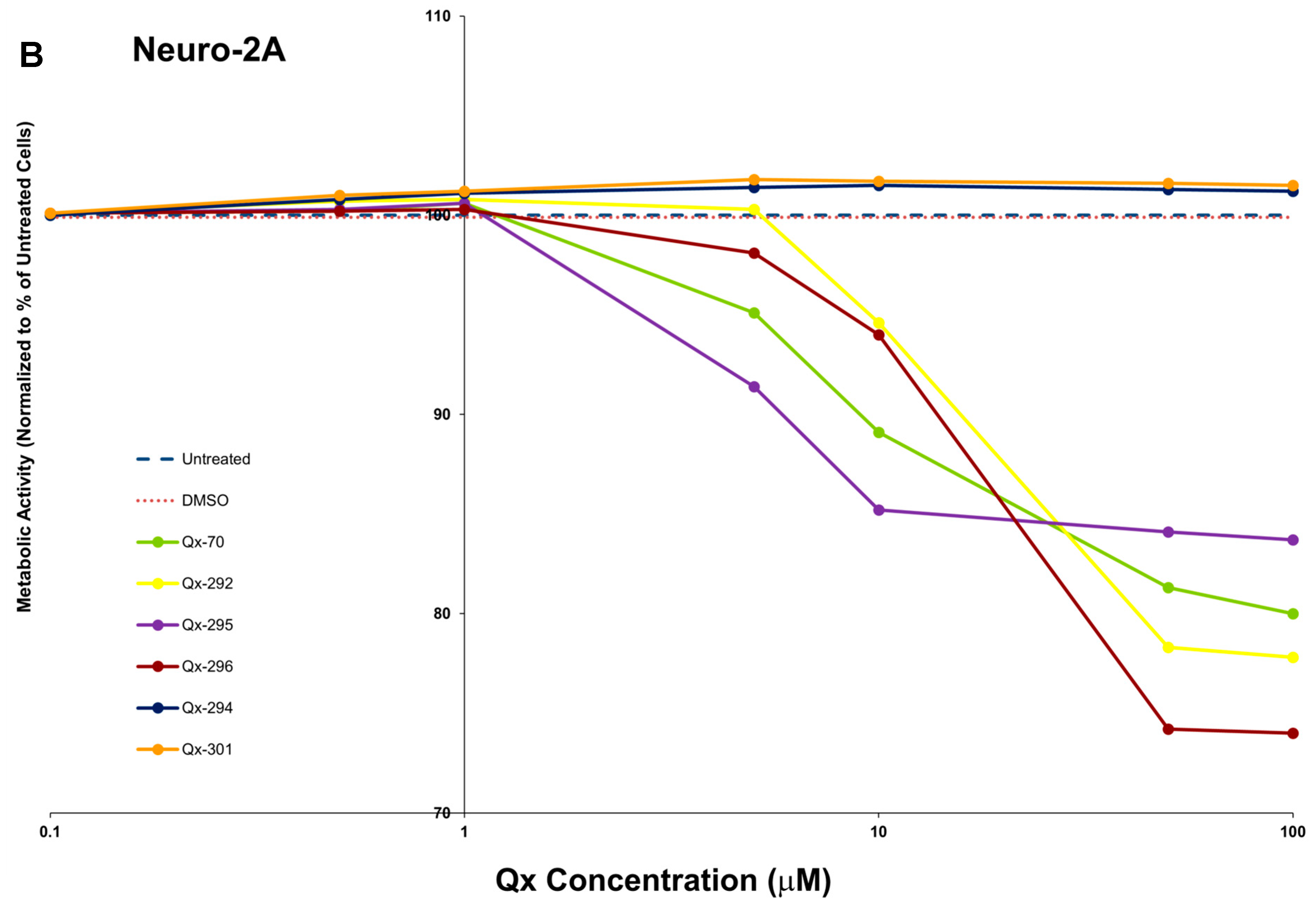

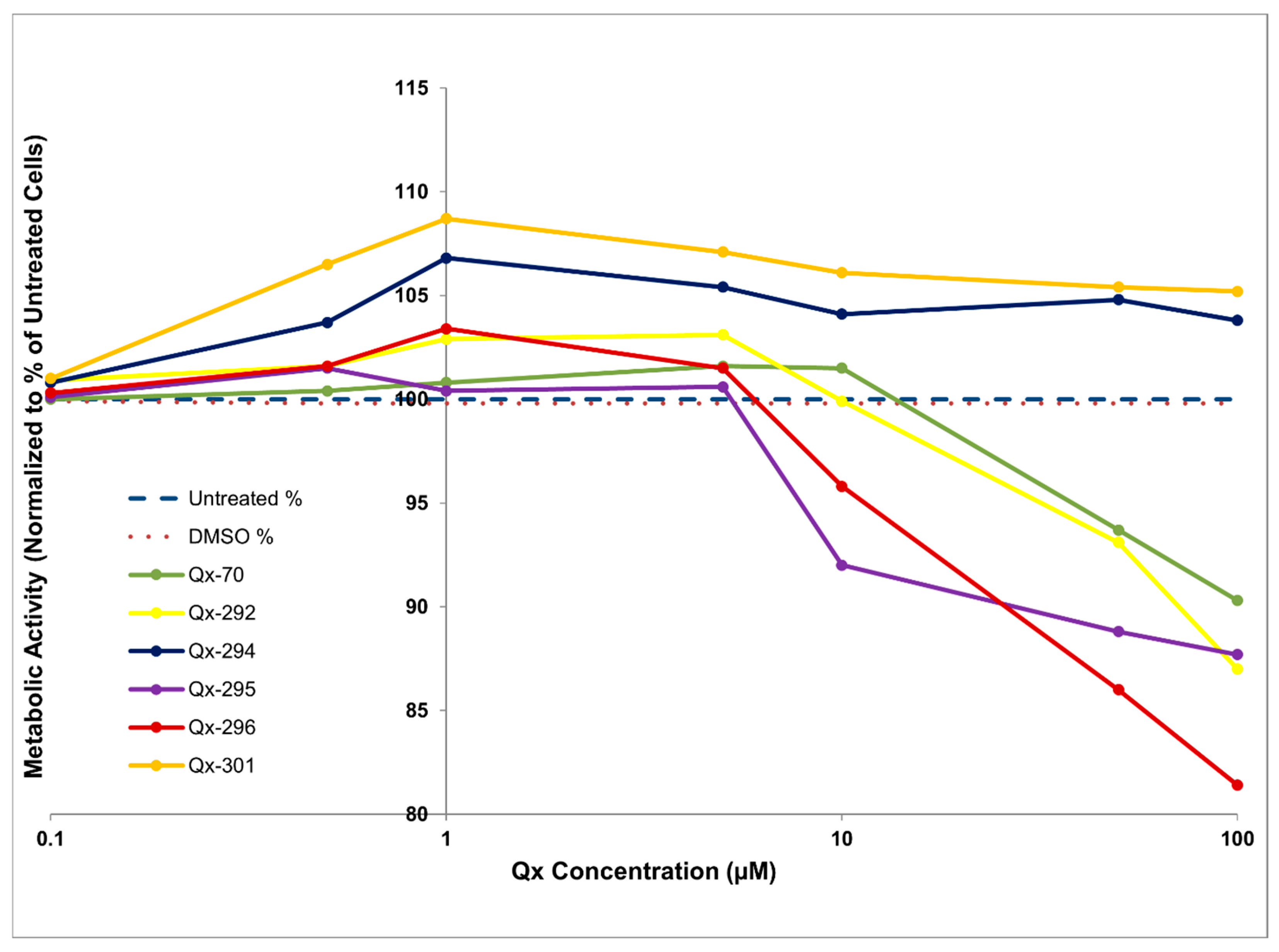

2.15.1. Cytotoxicity

2.15.2. Kinetic Solubility Assay

2.15.3. PAMPA Permeability Assay

- VD = donor compartment volume (0.15 mL);

- VA = acceptor compartment volume (0.3 mL);

- Area = area of the membrane (0.3 cm2);

- Time = time of incubation (57,600 s);

- CA(t) = concentration of solution in the acceptor chamber after 16 h;

- Ceq = represents the equilibrium concentration;

- Quality control standards, Verapamil (Pe = 16 × 10−6 cm s−1) for high permeability and theophylline (Pe = 0.12 × 10−6 cm s−1) for low permeability, were run with each sample set to monitor the consistency of the analysis.

2.15.4. Plasma Protein Binding (PPB)

2.15.5. Metabolic Stability

2.16. Data Analysis and Statistics

3. Results

3.1. Synthesis of Qx-294 and 301

3.2. In Vitro ADMETox

3.3. Increasing Concentrations of Qx-294 and Qx-301 on Zebrafish Neuromasts Do Not Affect the Integrity or Survival of Neuromast HCs In Vivo

3.4. Qx-294 and Qx-301 Treatments Lead to Unscheduled Proliferation and Supernumerary Cells on Zebrafish Neuromasts and Mouse Cochlear Explants

3.5. The Effect of Qx-294 and Qx-301 Treatments in the Mouse Cochlea

3.6. Assessing Auditory Function in Qx-294- and Qx-301-Treated Mouse Cochlea

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HC | Hair Cell (s) |

| SC | Supporting Cell (s) |

| Qx | Quinoxaline |

| HEI–OC1 | House Ear Institute-Organ of Corti 1 |

| ADME | Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, & Excretion |

| ABR | Auditory Brainstem Response |

| DPOAE | Distortion Product Otoacoustic Emissions |

| OC | Organ of Corti |

| TLC | Thin Layer Chromatography |

| Q1 | Single Quadrupole Analyzer |

| IACUC | Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee |

| GFP | Green Fluorescent Protein |

| PFA | Paraformaldehyde |

| IO4 | Infraorbital 4 |

| OP1 | Opercular 1 |

| M2 | Mandibular 2 |

| O | Otic |

| MI2 | Middle 2 |

| IP | Intraperitoneal |

| DMSO | Dimethyl Sulfoxide |

| FFT | Fast Fourier Transform |

| TDT | Transducers |

| MTT | 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide |

| FBS | Fetal Bovine Serum |

| PAMPA | Parallel Artificial Membrane Permeability Assay |

| PBS | Phosphate-Buffered Saline |

| NADPH | Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide Phosphate |

| IHC | Inner Hair Cell (s) |

| OHC | Outer Hair Cell (s) |

| ICC | Intra-Class Correlations |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| IS | Internal Standard |

| ADMETox | Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, & Toxicity |

| NCI | National Cancer Institute |

| MET | Mechanotransduction |

| LER | Lesser Epithelial Ridge |

| IPh | Inner Phalangeal |

| IB | Inner Border Cells |

| G | Gap |

Appendix A

References

- World Health Organization. World Report on Hearing; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Schwander, M.; Kachar, B.; Müller, U. Review series: The Cell Biology of Hearing. J. Cell Biol. 2010, 190, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corwin, J.T.; Cotanche, D.A. Regeneration of Sensory Hair Cells After Acoustic Trauma. Science 1988, 240, 1772–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, E.Y.; Rubel, E.W.; Raible, D.W. Notch Signaling Regulates the Extent of Hair Cell Regeneration in the Zebrafish Lateral Line. J. Neurosci. 2008, 28, 2261–2273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daudet, N.; Żak, M. Notch signalling: The multitask manager of inner ear development and regeneration. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2020, 1218, 129–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacques, B.E.; Montgomery, W.H., IV; Uribe, P.M.; Yatteau, A.; Asuncion, J.D.; Resendiz, G.; Matsui, J.I.; Dabdoub, A. The role of Wnt/β-catenin signaling in proliferation and regeneration of the developing basilar papilla and lateral line. Dev. Neurobiol. 2014, 74, 438–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jahanshir, E.; Llamas, J.; Kim, Y.; Biju, K.; Oak, S.; Gnedeva, K. The Hippo pathway and p27Kip1 cooperate to suppress mitotic regeneration in the organ of Corti and the retina. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2025, 122, e2411313122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, M.C.; Chang, Q.; Pan, A.; Lin, X.; Chen, P. Atoh1 directs the formation of sensory mosaics and induces cell proliferation in the postnatal mammalian cochlea in vivo. J. Neurosci. 2012, 32, 6699–6710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, B.J.; Coak, E.; Dearman, J.; Bailey, G.; Yamashita, T.; Kuo, B.; Zuo, J. In vivo interplay between p27Kip1, GATA3, ATOH1, and POU4F3 converts non-sensory cells to hair cells in adult mice. Cell Rep. 2017, 19, 307–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, A.; Sánchez-Guardado, L.; Juniat, S.; García-Sánchez, J.; Négre, N.; Ribeiro, A.; Fasano, L.; Romojaro, F.; Sánchez-Calderón, F.; Tunnacliffe, E.; et al. Generation of sensory hair cells by genetic programming with a combination of transcription factors. Development 2015, 142, 1948–1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warchol, M.E. Sensory regeneration in the vertebrate inner ear: Differences at the levels of cells and species. Hear. Res. 2011, 273, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, P.J.; Dong, Y.; Gu, S.; Liu, W.; Najarro, E.H.; Udagawa, T.; Cheng, A.G. Sox2 haploinsufficiency primes regeneration and Wnt responsiveness in the mouse cochlea. J. Clin. Investig. 2018, 128, 1641–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koehler, K.R.; Hashino, E. 3D mouse embryonic stem cell culture for generating inner ear organoids. Nat. Protoc. 2014, 9, 1229–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Segil, N. Early transcriptional response to aminoglycoside antibiotic reveals key pathways for hair cell death and survival in the mouse cochlea. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha-Sanchez, S.M.; Scheetz, L.R.; Contreras, M.; Weston, M.D.; Korte, M.; McGee, J.; Walsh, E.J. Mature mice lacking Rbl2/p130 gene have supernumerary inner ear hair cells and supporting cells. J. Neurosci. 2011, 31, 8883–8893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha-Sanchez, S.M.; Scheetz, L.R.; Siddiqi, S.; Weston, M.W.; Smith, L.M.; Dempsey, K.; Ali, H.; McGee, J.; Walsh, E.J. Lack of Rbl1/p107 effects on cell proliferation and maturation in the inner ear. J. Behav. Brain Sci. 2013, 3, 534–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tarang, S.; Doi, S.M.S.R.; Gurumurthy, C.B.; Harms, D.; Quadros, R.; Rocha-Sanchez, S.M. Generation of a Retinoblastoma (Rb)1-inducible dominant-negative (DN) mouse model. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarang, S.; Pyakurel, U.; Weston, M.D.; Vijayakumar, S.; Jones, T.; Wagner, K.U.; Rocha-Sanchez, S.M. Spatiotemporally controlled overexpression of cyclin D1 triggers generation of supernumerary cells in the postnatal mouse inner ear. Hear. Res. 2020, 390, 107951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocha-Sanchez, S.M.; Fuson, O.; Tarang, S.; Goodman, L.; Pyakurel, U.; Liu, H.; He, D.Z.; Zallocchi, M. Quinoxaline protects zebrafish lateral line hair cells from cisplatin and aminoglycosides damage. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 15119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouz, G.; Bouz, S.; Janďourek, O.; Konečná, K.; Bárta, P.; Vinšová, J.; Doležal, M.; Zitko, J. Synthesis, biological evaluation, and in silico modeling of N-substituted quinoxaline-2-carboxamides. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waseem, A.M.; Elmagzoub, R.M.; Abdelgadir, M.M.; Mazhar, M.; Al Bahir, A.A.; Abd EL-Gawaad, N.S.; Abdel-Samea, A.S.; Rao, D.P.; Kossenas, K.; Bräse, S.; et al. An insight into the therapeutic impact of quinoxaline derivatives: Recent advances in biological activities (2020–2024). Results Chem. 2025, 13, 101989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinec, G.M.; Webster, P.; Lim, D.J.; Kalinec, F. A cochlear cell line as an in vitro system for drug ototoxicity screening. Audiol. Neurootol. 2003, 8, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammond-Weinberger, D.R.; ZeRuth, G.T. Whole mount immunohistochemistry in zebrafish embryos and larvae. J. Vis. Exp. 2020, 155, e60575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guimaraes, P.; Zhu, X.; Cannon, T.; Kim, S.; Frisina, R.D. Sex differences in distortion product otoacoustic emissions as a function of age in CBA mice. Hear. Res. 2004, 192, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez, A.M.; Stagner, B.B.; Martin, G.K.; Lonsbury-Martin, B.L. Age-related loss of distortion product otoacoustic emissions in four mouse strains. Hear. Res. 1999, 138, 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, G.K.; Vazquez, A.E.; Jimenez, A.M.; Stagner, B.B.; Howard, M.A.; Lonsbury-Martin, B.L. Comparison of distortion product otoacoustic emissions in 28 inbred strains of mice. Hear. Res. 2007, 234, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Figueroa, M.J.; Pessoa-Mahana, C.D.; Palavecino-González, M.E.; Mella-Raipán, J.; Espinosa-Bustos, C.; Lagos-Muñoz, M.E. Evaluation of the membrane permeability (PAMPA and skin) of benzimidazoles with potential cannabinoid activity and their relation with the Biopharmaceutics Classification System (BCS). AAPS PharmSciTech 2011, 12, 573–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caprara, G.A.; Peng, A.W. Mechanotransduction in mammalian sensory hair cells. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2022, 120, 103706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellado Lagarde, M.M.; Wan, G.; Zhang, L.; Gigliello, A.R.; McInnis, J.J.; Zhang, Y.; Bergles, D.; Zuo, J.; Corfas, G. Spontaneous regeneration of cochlear supporting cells after neonatal ablation ensures hearing in the adult mouse. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 16919–16924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, W.; Zeng, S.; Li, W.; Cheng, Y.; Zhang, S.; Tang, M.; Sun, S.; Chai, R.; Li, H. Wnt activation followed by Notch inhibition promotes mitotic hair cell regeneration in the postnatal mouse cochlea. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 66754–66768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, W.; Lin, C.; Guo, L.; Wu, J.; Chen, Y.; Chai, R.; Li, W.; Li, H. Extensive Supporting Cell Proliferation and Mitotic Hair Cell Generation by In Vivo Genetic Reprogramming in the Neonatal Mouse Cochlea. J. Neurosci. 2016, 36, 873–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, J.A.; Cheng, A.G.; Cunningham, L.L.; MacDonald, G.; Raible, D.W.; Rubel, E.W. Neomycin-Induced Hair Cell Death and Rapid Regeneration in the Lateral Line of Zebrafish (Danio rerio). J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. 2003, 4, 219–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, E.D.; Cruz, I.A.; Hailey, D.W.; Raible, D.W. There and Back Again: Development and Regeneration of the Zebrafish Lateral Line System. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Dev. Biol. 2015, 4, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Head, J.R.; Gacioch, L.; Pennisi, M.; Meyers, J.R. Activation of Canonical Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling Stimulates Proliferation in Neuromasts in the Zebrafish Posterior Lateral Line. Dev. Dyn. 2013, 242, 832–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lush, M.E.; Diaz, D.C.; Koenecke, N.; Baek, S.; Boldt, H.; St Peter, M.K.; Gaitan-Escudero, T.; Romero-Carvajal, A.; Busch-Nentwich, E.M.; Perera, A.G.; et al. scRNA-Seq Reveals Distinct Stem Cell Populations that Drive Hair Cell Regeneration after Loss of Fgf and Notch Signaling. elife 2019, 8, e44431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.G.; Huang, M.; Obholzer, N.D.; Sun, S.; Li, W.; Petrillo, M.; Dai, P.; Zhou, Y.; Cotanche, D.A.; Megason, S.G.; et al. Myc and Fgf Are Required for Zebrafish Neuromast Hair Cell Regeneration. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0157768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, D.; He, Y.; Li, W.; Li, H. Wnt/β-Catenin Interacts with the FGF Pathway to Promote Proliferation and Regenerative Cell Proliferation in the Zebrafish Lateral Line Neuromast. Exp. Mol. Med. 2019, 51, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlovskaja-Gumbrienė, A.; Yi, R.; Alexander, R.; Aman, A.; Jiskra, R.; Nagelberg, D.; Knaut, H.; McClain, M.; Piotrowski, T. Proliferation-Independent Regulation of Organ Size by Fgf/Notch Signaling. elife 2017, 6, e21049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, F.; Hu, L.; Edge, A.S.B. Generation of Hair Cells in Neonatal Mice by β-Catenin Overexpression in Lgr5-Positive Cochlear Progenitors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 13851–13856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, W.J.; Yin, X.; Lu, L.; Lenz, D.R.; McLean, D.; Langer, R.; Karp, J.M.; Edge, A.S.B. Clonal expansion of Lgr5-positive cells from mammalian cochlea and high-purity generation of sensory hair cells. Cell Rep. 2017, 18, 1917–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Wu, J.; Yang, J.; Sun, S.; Chai, R.; Chen, Z.Y.; Li, H. Notch inhibition induces mitotic hair cell regeneration in the mammalian cochlea and is dependent on Wnt signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maass, J.C.; Gu, R.; Basch, M.L.; Waldhaus, J.; López, E.M.; Xia, A.; Oghalai, J.S.; Heller, S.; Groves, A.K. Transcriptomic analysis of mouse cochlear supporting cell maturation reveals large-scale changes in Notch responsiveness prior to the onset of hearing. J. Neurosci. 2015, 35, 3163–3180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sage, C.; Huang, M.; Vollrath, M.A.; Brown, M.C.; Hinds, P.W.; Corey, D.P.; Vetter, D.E.; Chen, Z.Y. Essential role of Ret-inoblastoma protein in mammalian hair cell development and hearing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 7345–7350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mantela, J.; Jiang, Z.; Ylikoski, J.; Fritzsch, B.; Zacksenhaus, E.; Pirvola, U. The retinoblastoma gene pathway regulates the postmitotic state of hair cells in the mouse inner ear. Development 2005, 132, 2377–2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, P.; Segil, N. p27(Kip1) links cell proliferation to morphogenesis in the developing organ of Corti. Development 1999, 126, 1581–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.S.; Liu, F.; Segil, N. A morphogenetic wave of p27Kip1 transcription directs cell cycle exit during organ of Corti development. Development 2006, 133, 2817–2826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boghean, L.; Singh, S.; Mangalaparthi, K.K.; Kizhake, S.; Umeta, L.; Wishka, D.; Grothaus, P.; Pandey, A.; Natarajan, A. A Selective MAP3K1 Inhibitor Facilitates Discovery of NPM1 as a Member of the Network. Molecules 2025, 30, 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, T.; Ma, C.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Hu, H. NF-κB Signaling in Inflammation and Cancer. MedComm 2021, 2, 618–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roccio, M.; Hahnewald, S.; Perny, M.; Senn, P. Cell cycle reactivation of cochlear progenitor cells in neonatal FUCCI mice by a GSK3 small molecule inhibitor. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 17886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.T.; Angus, S.P.; Johnson, G.L. MAP3K1: Genomic Alterations in Cancer and Function in Promoting Cell Survival or Apoptosis. Genes Cancer 2013, 4, 419–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.; Hottiger, M.O. Crosstalk between Wnt/β-Catenin and NF-κB Signaling Pathway during Inflammation. Front. Immunol. 2016, 7, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinz, M.; Krappmann, D.; Eichten, A.; Heder, A.; Scheidereit, C.; Strauss, M. NF-κB Function in Growth Control: Regulation of Cyclin D1 Expression and G0/G1-to-S-Phase Transition. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999, 19, 2690–2698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, W.M.; Althauser, C.; Ruohola-Baker, H. Notch-Delta Signaling Induces a Transition from Mitotic Cell Cycle to Endocycle in Drosophila Follicle Cells. Development 2001, 128, 4737–4746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shcherbata, H.R.; Althauser, C.; Findley, S.D.; Ruohola-Baker, H. The Mitotic-to-Endocycle Switch in Drosophila Follicle Cells Is Executed by Notch-Dependent Regulation of G1/S, G2/M, and M/M/G1 Cell-Cycle Transitions. Development 2004, 131, 3169–3181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemir, M.; Metrich, M.; Plaisance, I.; Lepore, M.; Cruchet, S.; Berthonneche, C.; Sarre, A.; Radtke, F.; Pedrazzini, T. The Notch Pathway Controls Fibrotic and Regenerative Repair in the Adult Heart. Eur. Heart J. 2014, 35, 2174–2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizutari, K.; Fujioka, M.; Hosoya, M.; Bramhall, N.; Okano, H.J.; Okano, H.; Edge, A.S. Notch inhibition induces cochlear hair cell regeneration and recovery of hearing after acoustic trauma. Neuron 2013, 77, 58–69, Erratum in Neuron 2013, 78, 403. Erratum in Neuron 2015, 96, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erni, S.T.; Gill, J.C.; Palaferri, C.; Fernandes, G.; Buri, M.; Lazarides, K.; Grandgirard, D.; Edge, A.S.B.; Leib, S.L.; Roccio, M. Hair cell generation in cochlear culture models mediated by novel γ-secretase inhibitors. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 710159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilder, A.G.M.; Wolpert, S.; Saeed, S.; Middelink, L.M.; Edge, A.S.B.; Blackshaw, H.; REGAIN Consortium; Pastiadis, K.; Bibas, A.G. A phase I/IIa safety and efficacy trial of intratympanic gamma-secretase inhibitor as a regenerative drug treatment for sensorineural hearing loss. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawamoto, K.; Ishimoto, S.; Minoda, R.; Brough, D.E.; Raphael, Y. Math1 gene transfer generates new cochlear hair cells in mature guinea pigs in vivo. J. Neurosci. 2003, 23, 4395–4400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, J.L.; Gao, W.Q. Overexpression of Math1 induces robust production of extra hair cells in postnatal rat inner ears. Nat. Neurosci. 2000, 3, 580–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruben, R.J. Development of the Inner Ear of the Mouse: A Radioautographic Study of Terminal Mitoses. Acta Otolaryngol. 1967, 220, 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley, M.W. Hair Cell Development: Commitment through Differentiation. Brain Res. 2006, 1091, 172–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sha, S.H.; Taylor, R.; Forge, A.; Schacht, J. Differential Vulnerability of Basal and Apical Hair Cells Is Based on Intrinsic Susceptibility to Free Radicals. Hear. Res. 2001, 155, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Experiment | Animal Model | N Per Compound (Qx-294 and Qx-301) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immunolabeling | Zebrafish | 25 | 50 |

| Mice | 9 | 18 | |

| EdU | Zebrafish | 25 | 50 |

| Mice | 9 | 18 | |

| TUNEL | Zebrafish | 25 | 50 |

| Mice | 9 | 18 | |

| FM1-43 | Zebrafish | 25 | 50 |

| Mice | 9 | 18 | |

| Auditory Function | Zebrafish | - | - |

| Mice | 9 | 18 |

| Compound Code | Solubility a (ng/mL) | Permeability b (×10−6 cm/s−1) | PPB c (% Bound) | Metabolic Stability d t1/2 = hour | Cytotoxicity e (IC50, μg/mL) * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qx-294 | 551 ± 24 | 3.5 ± 3.0 | 88.5 ± 4.0 | 57.2 ± 4.7 | >20 |

| Qx-301 | 365 ± 28 | 0.77 ± 0.91 | 32.3 ± 4.3 | 9.1 ± 8.4 | >20 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rocha-Sanchez, S.M.; North, E.J.; Calisto, L.E.; Barthol, B.M.; Nguyen, K.D.; Sethiya, J.P. Design and Synthesis of New Quinoxaline Analogs to Regenerate Sensory Auditory Hair Cells. Cells 2025, 14, 1946. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14241946

Rocha-Sanchez SM, North EJ, Calisto LE, Barthol BM, Nguyen KD, Sethiya JP. Design and Synthesis of New Quinoxaline Analogs to Regenerate Sensory Auditory Hair Cells. Cells. 2025; 14(24):1946. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14241946

Chicago/Turabian StyleRocha-Sanchez, Sonia M., Elton Jeffrey North, Lilian E. Calisto, Brock M. Barthol, Kenneth D. Nguyen, and Jigar P. Sethiya. 2025. "Design and Synthesis of New Quinoxaline Analogs to Regenerate Sensory Auditory Hair Cells" Cells 14, no. 24: 1946. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14241946

APA StyleRocha-Sanchez, S. M., North, E. J., Calisto, L. E., Barthol, B. M., Nguyen, K. D., & Sethiya, J. P. (2025). Design and Synthesis of New Quinoxaline Analogs to Regenerate Sensory Auditory Hair Cells. Cells, 14(24), 1946. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14241946