The Role of Autophagy Genes in Energy-Related Disorders

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Overview of Macroautophagy

3. Role of Autophagy-Related Complexes in Metabolic Diseases

3.1. Initiation and Nucleation Complexes in Obesity

3.1.1. Initiation and Nucleation Complexes in T2DM

3.1.2. Initiation and Nucleation Complexes in NAFLD

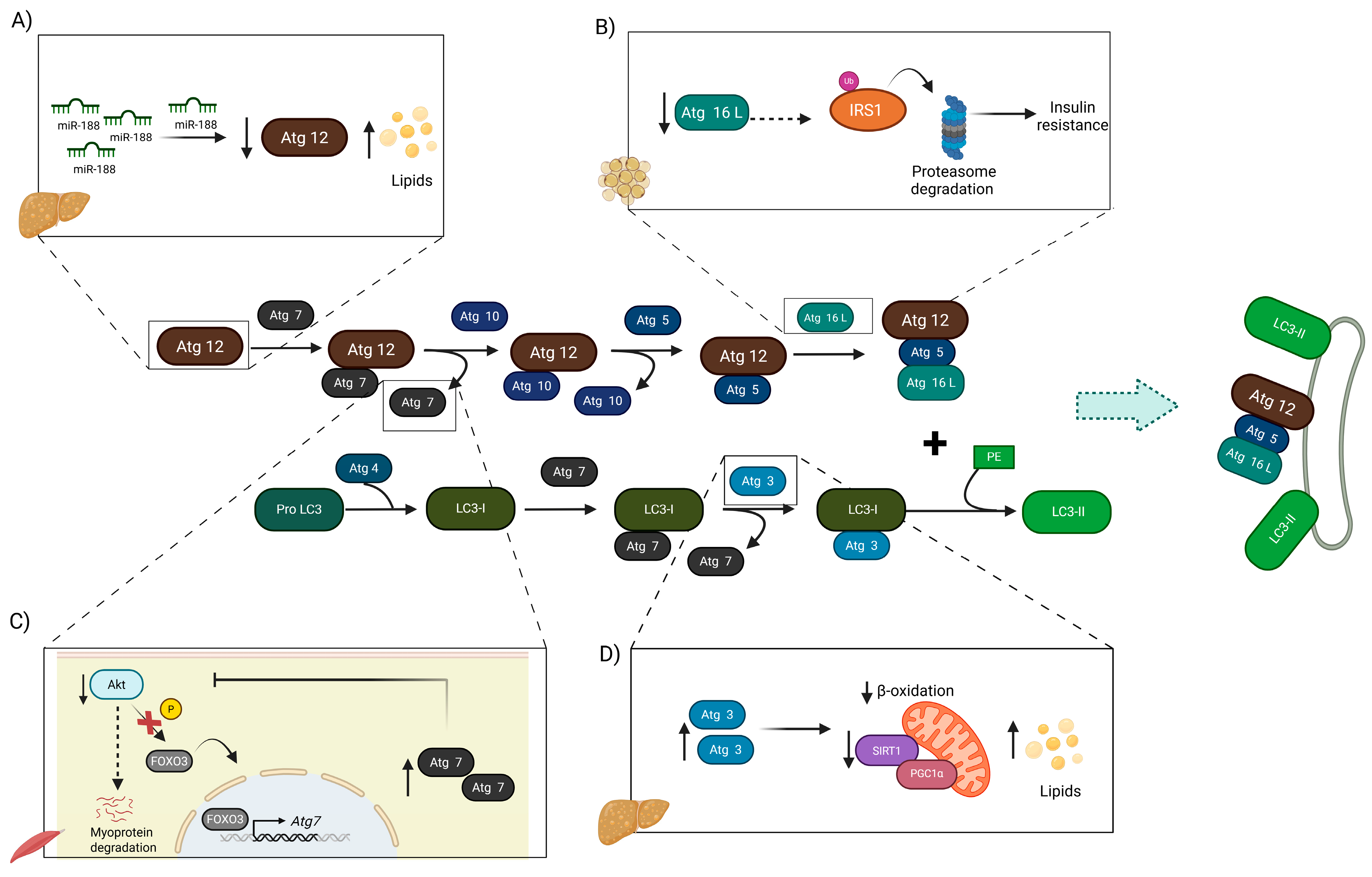

3.2. Conjugation Complexes in Obesity

3.2.1. Conjugation Complexes in T2DM

3.2.2. Conjugation Complexes in NAFLD

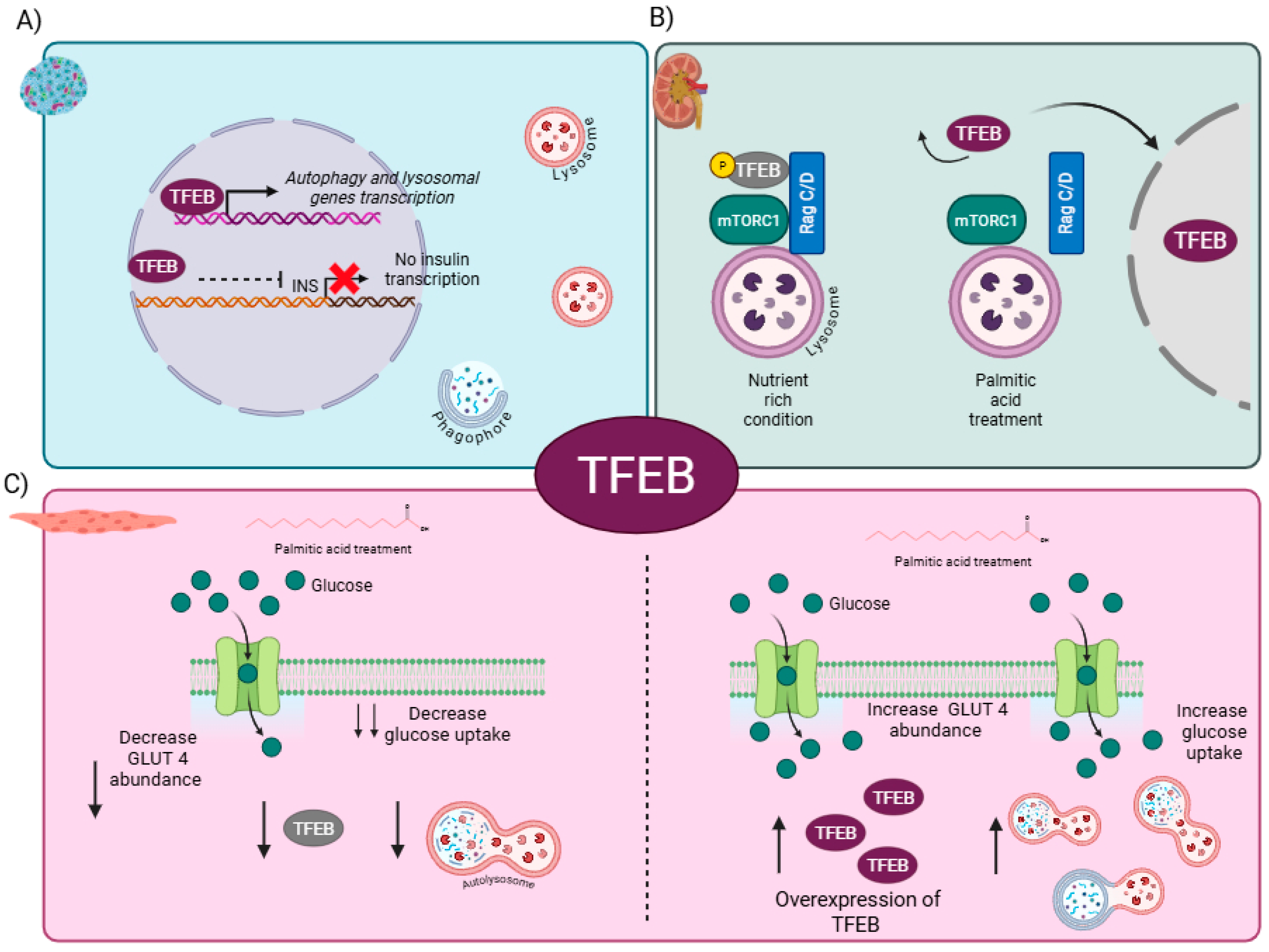

4. Master Regulator of Autophagy: The Role of TFEB in Metabolic-Related Diseases

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AKT | Protein kinase B |

| AMBRA1 | Activating Molecule in Beclin-1-Regulated Autophagy 1 |

| AMPK | AMP-activated protein kinase |

| ATG2 | Autophagy-related protein 2 |

| ATG3 | Autophagy-related protein 3 |

| ATG4B | Autophagy-related protein 4B |

| ATG5 | Autophagy-related protein 5 |

| ATG7 | Autophagy-related protein 7 |

| ATG8 | Autophagy-related protein 8 |

| ATG9 | Autophagy-related protein 9 |

| ATG10 | Autophagy-related protein 10 |

| ATG12 | Autophagy-related protein 12 |

| ATG13 | Autophagy-related protein 13 |

| Atg14 | Autophagy-related protein 14 |

| ATG14L | Autophagy-related protein 14L |

| ATG16(L) | Autophagy-related protein 16(L) |

| ATG16L1 | Autophagy-related protein 16L1 |

| ATG101 | Autophagy-related protein 101 |

| ATGL | Adipose triglyceride lipase |

| Becn1 | Beclin-1 |

| C2C12 | myoblast cell line |

| CALCOCO1 | Calcium-binding and coiled-coil domain-containing protein 2 |

| CGI-58 | Comparative Gene Identification-58 |

| CNS | Central nervous system |

| CPT1a | Carnitine Palmitoyltransferase 1A |

| CSE | Cystathionine γ-lyase |

| DFCP1 | Double-FYVE containing protein 1 |

| DKD | Diabetic Kidney Disease |

| DNMT1 | DNA (cytosine-5)-methyltransferase 1 |

| DRAK2 | DAP-related apoptosis-inducing kinase-2 |

| EndoC-βH1 | Human β-cell line |

| ER | Endoplasmic reticulum |

| ESCRT | Endosomal Sorting Complex Required for Transport |

| FFA | Free fatty acids |

| FIP200 | FAK-family Interacting Protein of 200 kDa |

| FOXO3 | Forkhead box O3 |

| GABARAP | γ-aminobutyrate type A receptor-associated protein |

| GABARAPL1 | GABA type A receptor-associated protein like 1 |

| GABARAPL2 | GABA type A receptor-associated protein like 2 |

| GLUT4 | Glucose transporter type 4 |

| H2S | Hydrogen Sulfide |

| HepG2 | human liver cancer cell line |

| HFD | High fat diet |

| IL-23 | Interleukine-23 |

| INS-1E | Insuline-1E |

| IRS1 | Insulin Receptor Substrate 1 |

| LAMP2 | Lysosome-associated membrane protein 2 |

| LC3A | Microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 alpha |

| LC3B | Microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3B |

| LC3C | Microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3B |

| LIR | LC3 interaction |

| 3-MA | 3-Methyladenine |

| MBLs | Multilamellar bodies |

| MEFs | Mouse embryonic fibroblasts |

| mTORC1 | Mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 |

| NAFLD | Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease |

| NASH | Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis |

| NBR1 | Autophagy Cargo Receptor |

| NDP52 | Nuclear dot protein 52 kDa |

| p62/SQSTM1 | Sequestosome-1 |

| PE | Phosphatidylethanolamine |

| PI3KC3 | Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase Catalytic Subunit Type 3 |

| PI3P | Phosphatidylinositol-3-phosphate |

| PIP4 | Phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate |

| POMC | Pro-opiomelanocortin |

| PTECs | Proximal tubular epithelial cells |

| RACK1 | Receptor for Activated C Kinase 1 |

| SARs | Selective autophagy receptors |

| Sec6 | Exocyst complex component Sec6 |

| SIRT1 | Sirtuin 1 |

| SNARE | Soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive fusion protein Attachment Protein Receptor |

| SREBP | Sterol Regulatory Element-Binding Protein |

| T2DM | Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus |

| TAX1BP1 | Tax1-binding protein 1 |

| TFEB | Transcription Factor EB |

| THLE2 | Human liver epithelial cell line |

| TRABID | TRAF-binding domain protein |

| ULK complex | UNC-51-like kinase complex |

| ULK1 | Unc-51–like autophagy-activating kinase 1 |

| ULK1/2 | UNC-51-like kinase 1 and 2 |

| UVRAG | UV radiation resistance-associated gene |

| VPS15 | Vacuolar Protein Sorting 15 |

| VPS34 | Vacuolar Protein Sorting 34 |

| WAT | White adipose tissue |

| WIPI | WD-repeat protein interacting with phosphoinositides |

References

- Lu, X.; Xie, Q.; Pan, X.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, X.; Peng, G.; Zhang, Y.; Shen, S.; Tong, N. Type 2 diabetes mellitus in adults: Pathogenesis, prevention and therapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekaran, P.; Weiskirchen, R. The Role of Obesity in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus-An Overview. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; An, Y.; Liu, H.; Jiang, J.; Liu, W.; Zhou, Y.; Shi, M.; Dai, W.; Lv, Y.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Global epidemiology of type 2 diabetes in patients with NAFLD or MAFLD: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2024, 22, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaidalkilani, A.T.; Al-Kuraishy, H.M.; Fahad, E.H.; Al-Gareeb, A.I.; Elewa, Y.H.A.; Zahran, M.H.; Alexiou, A.; Papadakis, M.; Al-Farga, A.; Batiha, G.E. Autophagy modulators in type 2 diabetes: A new perspective. J. Diabetes 2024, 16, e70010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, A.; Niknam, M.; Momeni-Moghaddam, M.A.; Shabani, M.; Aria, H.; Bastin, A.; Teimouri, M.; Meshkani, R.; Akbari, H. Crosstalk between autophagy and insulin resistance: Evidence from different tissues. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2023, 28, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, M.; Wang, Y. Induction of Autophagy as a Therapeutic Breakthrough for NAFLD: Current Evidence and Perspectives. Biology 2025, 14, 989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Liu, H.; Chen, K.; Guo, Y.; Mo, T.; Gao, T. Inhibition of autophagy impairs free fatty acid-induced excessive lipid accumulation in hepatocellular carcinoma and hepatic cells. J. Biosci. 2022, 47, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trelford, C.B.; Di Guglielmo, G.M. Molecular mechanisms of mammalian autophagy. Biochem. J. 2021, 478, 3395–3421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitto, V.A.M.; Bianchin, S.; Zolondick, A.A.; Pellielo, G.; Rimessi, A.; Chianese, D.; Yang, H.; Carbone, M.; Pinton, P.; Giorgi, C.; et al. Molecular Mechanisms of Autophagy in Cancer Development, Progression, and Therapy. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seok, S.; Kim, Y.C.; Zhang, Y.; Kong, B.; Guo, G.; Ma, J.; Kemper, B.; Kemper, J.K. Feeding activates FGF15-SHP-TFEB-mediated lipophagy in the gut. EMBO J. 2022, 41, e109997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, H.; Zhang, S.; Mizushima, N. Autophagy genes in biology and disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2023, 24, 382–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Stjepanovic, G. ATG2A-WDR45/WIPI4-ATG9A complex-mediated lipid transfer and equilibration during autophagosome formation. Autophagy 2025, 21, 1611–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almannai, M.; Marafi, D.; El-Hattab, A.W. WIPI proteins: Biological functions and related syndromes. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2022, 15, 1011918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercer, T.J.; Ohashi, Y.; Boeing, S.; Jefferies, H.B.J.; De Tito, S.; Flynn, H.; Tremel, S.; Zhang, W.; Wirth, M.; Frith, D.; et al. Phosphoproteomic identification of ULK substrates reveals VPS15-dependent ULK/VPS34 interplay in the regulation of autophagy. EMBO J. 2021, 40, e105985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noda, N.N. Atg2 and Atg9: Intermembrane and interleaflet lipid transporters driving autophagy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2021, 1866, 158956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karanasios, E.; Walker, S.A.; Okkenhaug, H.; Manifava, M.; Hummel, E.; Zimmermann, H.; Ahmed, Q.; Domart, M.C.; Collinson, L.; Ktistakis, N.T. Autophagy initiation by ULK complex assembly on ER tubulovesicular regions marked by ATG9 vesicles. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 12420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, Q.; Chen, S.; Li, Z.; Fu, L. Targeting VPS34 in autophagy: An update on pharmacological small-molecule compounds. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2023, 256, 115467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martens, S.; Fracchiolla, D. Activation and targeting of ATG8 protein lipidation. Cell Discov. 2020, 6, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iriondo, M.N.; Etxaniz, A.; Varela, Y.R.; Ballesteros, U.; Lazaro, M.; Valle, M.; Fracchiolla, D.; Martens, S.; Montes, L.R.; Goni, F.M.; et al. Effect of ATG12-ATG5-ATG16L1 autophagy E3-like complex on the ability of LC3/GABARAP proteins to induce vesicle tethering and fusion. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2023, 80, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.N.; Padman, B.S.; Usher, J.; Oorschot, V.; Ramm, G.; Lazarou, M. Atg8 family LC3/GABARAP proteins are crucial for autophagosome-lysosome fusion but not autophagosome formation during PINK1/Parkin mitophagy and starvation. J. Cell Biol. 2016, 215, 857–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, S.E.; Kolapalli, S.P.; Nielsen, T.M.; Frankel, L.B. Canonical and non-canonical roles for ATG8 proteins in autophagy and beyond. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2022, 9, 1074701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizushima, N. The ATG conjugation systems in autophagy. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2020, 63, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.N.; Padman, B.S.; Zellner, S.; Khuu, G.; Uoselis, L.; Lam, W.K.; Skulsuppaisarn, M.; Lindblom, R.S.J.; Watts, E.M.; Behrends, C.; et al. ATG4 family proteins drive phagophore growth independently of the LC3/GABARAP lipidation system. Mol. Cell 2021, 81, 2013–2030 e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubas, A.; Dikic, I. A guide to the regulation of selective autophagy receptors. FEBS J. 2022, 289, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adriaenssens, E.; Ferrari, L.; Martens, S. Orchestration of selective autophagy by cargo receptors. Curr. Biol. 2022, 32, R1357–R1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Chen, X.; Ji, C.; Zhang, W.; Song, J.; Li, J.; Wang, J. Key Regulators of Autophagosome Closure. Cells 2021, 10, 2814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, P.Y. Molecular Mechanism of Autophagosome-Lysosome Fusion in Mammalian Cells. Cells 2024, 13, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, T.T.P.; Kim, D.Y.; Lee, Y.G.; Lee, Y.S.; Truong, X.T.; Lee, J.H.; Song, D.K.; Kwon, T.K.; Park, S.H.; Jung, C.H.; et al. SREBP-1c impairs ULK1 sulfhydration-mediated autophagic flux to promote hepatic steatosis in high-fat-diet-fed mice. Mol. Cell 2021, 81, 3820–3832 e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, D.; Molusky, M.M.; Song, J.; Hu, C.R.; Fang, F.; Rui, C.; Mathew, A.V.; Pennathur, S.; Liu, F.; Cheng, J.X.; et al. Autophagy deficiency by hepatic FIP200 deletion uncouples steatosis from liver injury in NAFLD. Mol. Endocrinol. 2013, 27, 1643–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, Y.; Ji, Y.; Song, Y.; Choe, S.S.; Jeon, Y.G.; Na, H.; Nam, T.W.; Kim, H.J.; Nahmgoong, H.; Kim, S.M.; et al. Depletion of Adipocyte Becn1 Leads to Lipodystrophy and Metabolic Dysregulation. Diabetes 2021, 70, 182–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuramoto, K.; Kim, Y.J.; Hong, J.H.; He, C. The autophagy protein Becn1 improves insulin sensitivity by promoting adiponectin secretion via exocyst binding. Cell Rep. 2021, 35, 109184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Postoak, J.L.; Yang, G.; Guo, X.; Pua, H.H.; Bader, J.; Rathmell, J.C.; Kobayashi, H.; Haase, V.H.; Leaptrot, K.L.; et al. Lipid kinase PIK3C3 maintains healthy brown and white adipose tissues to prevent metabolic diseases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2214874120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Park, J.; Chowdhury, K.; Xu, J.; Lu, A.; Wang, L.; Zhang, W.; Ekser, B.; Yu, L.; et al. ATG14 plays a critical role in hepatic lipid droplet homeostasis. Metabolism 2023, 148, 155693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyo, J.O.; Yoo, S.M.; Ahn, H.H.; Nah, J.; Hong, S.H.; Kam, T.I.; Jung, S.; Jung, Y.K. Overexpression of Atg5 in mice activates autophagy and extends lifespan. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 2300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Li, L.; Livingston, M.J.; Zhang, D.; Mi, Q.; Zhang, M.; Ding, H.F.; Huo, Y.; Mei, C.; Dong, Z. p53/microRNA-214/ULK1 axis impairs renal tubular autophagy in diabetic kidney disease. J. Clin. Investig. 2020, 130, 5011–5026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Xu, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, R.; Dai, C.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, X.; Xu, L.; Tao, Y.; Han, M.; et al. DRAK2 suppresses autophagy by phosphorylating ULK1 at Ser(56) to diminish pancreatic beta cell function upon overnutrition. Sci. Transl. Med. 2024, 16, eade8647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, J.; Luo, H.; Wu, J. Drak2 overexpression results in increased beta-cell apoptosis after free fatty acid stimulation. J. Cell. Biochem. 2008, 105, 1073–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munasinghe, P.E.; Riu, F.; Dixit, P.; Edamatsu, M.; Saxena, P.; Hamer, N.S.; Galvin, I.F.; Bunton, R.W.; Lequeux, S.; Jones, G.; et al. Type-2 diabetes increases autophagy in the human heart through promotion of Beclin-1 mediated pathway. Int. J. Cardiol. 2016, 202, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohashi, Y. Activation Mechanisms of the VPS34 Complexes. Cells 2021, 10, 3124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemazanyy, I.; Montagnac, G.; Russell, R.C.; Morzyglod, L.; Burnol, A.F.; Guan, K.L.; Pende, M.; Panasyuk, G. Class III PI3K regulates organismal glucose homeostasis by providing negative feedback on hepatic insulin signalling. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 8283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilanges, B.; Alliouachene, S.; Pearce, W.; Morelli, D.; Szabadkai, G.; Chung, Y.L.; Chicanne, G.; Valet, C.; Hill, J.M.; Voshol, P.J.; et al. Vps34 PI 3-kinase inactivation enhances insulin sensitivity through reprogramming of mitochondrial metabolism. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, L.; Zhou, Y.; Cao, H.; Wen, P.; Jiang, L.; He, W.; Dai, C.; Yang, J. Autophagy attenuates diabetic glomerular damage through protection of hyperglycemia-induced podocyte injury. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e60546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yassin, R.; Tadmor, H.; Farber, E.; Igbariye, A.; Armaly-Nakhoul, A.; Dahan, I.; Nakhoul, F.; Nakhoul, N. Alteration of autophagy-related protein 5 (ATG5) levels and Atg5 gene expression in diabetes mellitus with and without complications. Diab Vasc. Dis. Res. 2021, 18, 14791641211062050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Benedittis, G.; Latini, A.; Spallone, V.; Novelli, G.; Borgiani, P.; Ciccacci, C. ATG5 gene expression analysis supports the involvement of autophagy in microangiopathic complications of type 2 diabetes. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2023, 33, 1797–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.H.; Park, S.H.; Ahn, J.; Hong, S.P.; Lee, E.; Jang, Y.J.; Ha, T.Y.; Huh, Y.H.; Ha, S.Y.; Jeon, T.I.; et al. Mir214-3p and Hnf4a/Hnf4alpha reciprocally regulate Ulk1 expression and autophagy in nonalcoholic hepatic steatosis. Autophagy 2021, 17, 2415–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salah Nour, M.; Sakara, Z.A.E.-H.; Hasanin, N.A.; Hamed, S.M. Histological and immunohistochemical study of the effect of liraglutide in experimental model of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Egypt. J. Basic. Appl. Sci. 2023, 10, 342–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.H.; Huang, T.Y.; Lin, Y.T.; Lin, S.Y.; Li, W.H.; Hsiao, H.J.; Yan, R.L.; Tang, H.W.; Shen, Z.Q.; Chen, G.C.; et al. VPS34 K29/K48 branched ubiquitination governed by UBE3C and TRABID regulates autophagy, proteostasis and liver metabolism. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galle-Treger, L.; Helou, D.G.; Quach, C.; Howard, E.; Hurrell, B.P.; Muench, G.R.A.; Shafiei-Jahani, P.; Painter, J.D.; Iorga, A.; Dara, L.; et al. Autophagy impairment in liver CD11c(+) cells promotes non-alcoholic fatty liver disease through production of IL-23. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pant, R.; Kabeer, S.W.; Sharma, S.; Kumar, V.; Patra, D.; Pal, D.; Tikoo, K. Pharmacological inhibition of DNMT1 restores macrophage autophagy and M2 polarization in Western diet-induced nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Biol. Chem. 2023, 299, 104779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Mariman, E.C.M.; Roumans, N.J.T.; Vink, R.G.; Goossens, G.H.; Blaak, E.E.; Jocken, J.W.E. Adipose tissue autophagy related gene expression is associated with glucometabolic status in human obesity. Adipocyte 2018, 7, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.; Yang, J.; Zheng, L.; Su, H.; Cao, S.; Jiang, X.; Liu, X.; Liu, W.; Wang, Z.; Meng, F.; et al. Dysfunction of Akt/FoxO3a/Atg7 regulatory loop magnifies obesity-regulated muscular mass decline. Mol. Metab. 2024, 81, 101892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Zhang, S.; Wang, X.; Gao, D.; Liu, J.; Cao, K.; Chen, L.; Liu, R.; Liu, J.; Long, J. ATG7 regulates hepatic Akt phosphorylation through the c-JUN/PTEN pathway in high fat diet-induced metabolic disorder. FASEB J. 2019, 33, 14296–14306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Goldman, S.; Baerga, R.; Zhao, Y.; Komatsu, M.; Jin, S. Adipose-specific deletion of autophagy-related gene 7 (atg7) in mice reveals a role in adipogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 19860–19865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Xiang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Baikati, K.; Cuervo, A.M.; Luu, Y.K.; Tang, Y.; Pessin, J.E.; Schwartz, G.J.; Czaja, M.J. Autophagy regulates adipose mass and differentiation in mice. J. Clin. Investig. 2009, 119, 3329–3339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakane, S.; Hikita, H.; Shirai, K.; Myojin, Y.; Sasaki, Y.; Kudo, S.; Fukumoto, K.; Mizutani, N.; Tahata, Y.; Makino, Y.; et al. White Adipose Tissue Autophagy and Adipose-Liver Crosstalk Exacerbate Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Mice. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 12, 1683–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, Y.; Tyndall, E.R.; Bui, V.; Bewley, M.C.; Wang, G.; Hong, X.; Shen, Y.; Flanagan, J.M.; Wang, H.G.; Tian, F. Multifaceted membrane interactions of human Atg3 promote LC3-phosphatidylethanolamine conjugation during autophagy. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 5503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sou, Y.S.; Waguri, S.; Iwata, J.; Ueno, T.; Fujimura, T.; Hara, T.; Sawada, N.; Yamada, A.; Mizushima, N.; Uchiyama, Y.; et al. The Atg8 conjugation system is indispensable for proper development of autophagic isolation membranes in mice. Mol. Biol. Cell 2008, 19, 4762–4775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuboyama, K.; Koyama-Honda, I.; Sakamaki, Y.; Koike, M.; Morishita, H.; Mizushima, N. The ATG conjugation systems are important for degradation of the inner autophagosomal membrane. Science 2016, 354, 1036–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malhotra, R.; Warne, J.P.; Salas, E.; Xu, A.W.; Debnath, J. Loss of Atg12, but not Atg5, in pro-opiomelanocortin neurons exacerbates diet-induced obesity. Autophagy 2015, 11, 145–154. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Zhou, X.; Xiao, Y.; Li, C.; Huang, Y.; Guo, Q.; Su, T.; Fu, L.; Luo, L. miR-188 promotes liver steatosis and insulin resistance via the autophagy pathway. J. Endocrinol. 2020, 245, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Guo, E.; Yang, J.; Li, A.; Yang, Y.; Liu, S.; Liu, A.; Jiang, X. 1,25(OH)2D3 attenuates hepatic steatosis by inducing autophagy in mice. Obesity 2017, 25, 561–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebato, C.; Uchida, T.; Arakawa, M.; Komatsu, M.; Ueno, T.; Komiya, K.; Azuma, K.; Hirose, T.; Tanaka, K.; Kominami, E.; et al. Autophagy is important in islet homeostasis and compensatory increase of beta cell mass in response to high-fat diet. Cell Metab. 2008, 8, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, W.; Hur, K.Y.; Lim, Y.; Oh, S.H.; Lee, J.C.; Kim, K.H.; Kim, G.H.; Kim, S.W.; Kim, H.L.; Lee, M.K.; et al. Autophagy deficiency in beta cells leads to compromised unfolded protein response and progression from obesity to diabetes in mice. Diabetologia 2012, 55, 392–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Li, P.; Fu, S.; Calay, E.S.; Hotamisligil, G.S. Defective hepatic autophagy in obesity promotes ER stress and causes insulin resistance. Cell Metab. 2010, 11, 467–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Pires, K.M.; Ferhat, M.; Chaurasia, B.; Buffolo, M.A.; Smalling, R.; Sargsyan, A.; Atkinson, D.L.; Summers, S.A.; Graham, T.E.; et al. Autophagy Ablation in Adipocytes Induces Insulin Resistance and Reveals Roles for Lipid Peroxide and Nrf2 Signaling in Adipose-Liver Crosstalk. Cell Rep. 2018, 25, 1708–1717 e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, L.; Wang, P.; Xue, Y.; Li, X.; Qiao, X.; Zhang, X.; Xu, T.; Liu, G.; et al. Autophagy impairment mediated by S-nitrosation of ATG4B leads to neurotoxicity in response to hyperglycemia. Autophagy 2017, 13, 1145–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frendo-Cumbo, S.; Jaldin-Fincati, J.R.; Coyaud, E.; Laurent, E.M.N.; Townsend, L.K.; Tan, J.M.J.; Xavier, R.J.; Pillon, N.J.; Raught, B.; Wright, D.C.; et al. Deficiency of the autophagy gene ATG16L1 induces insulin resistance through KLHL9/KLHL13/CUL3-mediated IRS1 degradation. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 16172–16185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waye, M.M.Y. Mutation of autophagy-related gene ATG7 increases the risk of severe disease in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Liver Res. 2023, 7, 365–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baselli, G.A.; Jamialahmadi, O.; Pelusi, S.; Ciociola, E.; Malvestiti, F.; Saracino, M.; Santoro, L.; Cherubini, A.; Dongiovanni, P.; Maggioni, M.; et al. Rare ATG7 genetic variants predispose patients to severe fatty liver disease. J. Hepatol. 2022, 77, 596–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrientos-Riosalido, A.; Real, M.; Bertran, L.; Aguilar, C.; Martinez, S.; Parada, D.; Vives, M.; Sabench, F.; Riesco, D.; Castillo, D.D.; et al. Increased Hepatic ATG7 mRNA and ATG7 Protein Expression in Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Associated with Obesity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva Lima, N.; Fondevila, M.F.; Novoa, E.; Buque, X.; Mercado-Gomez, M.; Gallet, S.; Gonzalez-Rellan, M.J.; Fernandez, U.; Loyens, A.; Garcia-Vence, M.; et al. Inhibition of ATG3 ameliorates liver steatosis by increasing mitochondrial function. J. Hepatol. 2022, 76, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Napolitano, G.; Ballabio, A. TFEB at a glance. J. Cell Sci. 2016, 129, 2475–2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Gong, S.; Zhang, H.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Y.; Hao, J.; Liu, H.; Li, X. From the regulatory mechanism of TFEB to its therapeutic implications. Cell Death Discov. 2024, 10, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco-Juarez, B.; Coronel-Cruz, C.; Hernandez-Ochoa, B.; Gomez-Manzo, S.; Cardenas-Rodriguez, N.; Arreguin-Espinosa, R.; Bandala, C.; Canseco-Avila, L.M.; Ortega-Cuellar, D.; TFEB. Beyond Its Role as an Autophagy and Lysosomes Regulator. Cells 2022, 11, 3153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquier, A.; Pastore, N.; D’Orsi, L.; Colonna, R.; Esposito, A.; Maffia, V.; De Cegli, R.; Mutarelli, M.; Ambrosio, S.; Tufano, G.; et al. TFEB and TFE3 control glucose homeostasis by regulating insulin gene expression. EMBO J. 2023, 42, e113928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Li, C.G.; Zhou, X.; Ding, S. Transcription factor EB enhances autophagy and ameliorates palmitate-induced insulin resistance at least partly via upregulating AMPK activity in skeletal muscle cells. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2022, 49, 302–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, J.; Yamamoto, T.; Takabatake, Y.; Namba-Hamano, T.; Minami, S.; Takahashi, A.; Matsuda, J.; Sakai, S.; Yonishi, H.; Maeda, S.; et al. TFEB-mediated lysosomal exocytosis alleviates high-fat diet-induced lipotoxicity in the kidney. JCI Insight 2023, 8, e162498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martina, J.A.; Puertollano, R. Rag GTPases mediate amino acid-dependent recruitment of TFEB and MITF to lysosomes. J. Cell Biol. 2013, 200, 475–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Franco-Juárez, B.; Rodríguez, N.C.; Camacho, L.; Gómez-Manzo, S.; Hernández-Ochoa, B.; Aguilera-Méndez, A.; Bandala, C.; Canseco-Ávila, L.M.; Ortega-Cuellar, D. The Role of Autophagy Genes in Energy-Related Disorders. Cells 2025, 14, 1947. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14241947

Franco-Juárez B, Rodríguez NC, Camacho L, Gómez-Manzo S, Hernández-Ochoa B, Aguilera-Méndez A, Bandala C, Canseco-Ávila LM, Ortega-Cuellar D. The Role of Autophagy Genes in Energy-Related Disorders. Cells. 2025; 14(24):1947. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14241947

Chicago/Turabian StyleFranco-Juárez, Berenice, Noemí Cárdenas Rodríguez, Luz Camacho, Saúl Gómez-Manzo, Beatriz Hernández-Ochoa, Asdrubal Aguilera-Méndez, Cindy Bandala, Luis Miguel Canseco-Ávila, and Daniel Ortega-Cuellar. 2025. "The Role of Autophagy Genes in Energy-Related Disorders" Cells 14, no. 24: 1947. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14241947

APA StyleFranco-Juárez, B., Rodríguez, N. C., Camacho, L., Gómez-Manzo, S., Hernández-Ochoa, B., Aguilera-Méndez, A., Bandala, C., Canseco-Ávila, L. M., & Ortega-Cuellar, D. (2025). The Role of Autophagy Genes in Energy-Related Disorders. Cells, 14(24), 1947. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14241947