Highlights

What are the main findings?

- Developed an optimized dissociation and recording protocol enabling reliable automated patch-clamp recordings of major atrial ionic currents (INa, ICaL, Ito, IKur, ISK, and If) in hiPSC-derived atrial cardiomyocytes.

- Demonstrated that current profiles obtained with the automated Patchliner system resemble those of native human atrial cardiomyocytes, validating the physiological relevance of the model.

What are the implications of the main findings?

- The optimized automated patch-clamp workflow provides a robust platform for the functional characterization of ion channels and genetic variants implicated in atrial arrhythmias.

- This approach facilitates precision medicine applications and targeted drug development for atrial channelopathies.

Abstract

Human-induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes (hiPSC-CMs) represent a robust platform for modelling inherited cardiac disorders. Comparative analysis of ion channel activity in patient-specific and isogenic control lines provides critical insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying channelopathies and arrhythmias. Atrial-specific hiPSC-CMs (hiPSC-aCMs) exhibit distinct electrophysiological properties governed by unique ion channel expression profiles, underscoring the need for optimized methodologies to record atrial ionic currents accurately. Here, we characterized the electrophysiological features of hiPSC-aCMs using the Nanion Patchliner automated patch-clamp system. An optimized cell dissociation protocol was developed to enhance cell integrity and seal formation, while tailored intra- and extracellular solutions were employed to isolate specific ionic currents. Using this approach, we reliably recorded major atrial currents, including the sodium current (INa), L-type calcium current (ICaL), transient outward potassium current (Ito), ultrarapid component of the delayed rectifier current (IKur), small-conductance calcium-activated potassium current (ISK), and pacemaker funny current (If). The resulting current profiles were reproducible and consistent with those observed in native atrial cardiomyocytes. These findings establish the feasibility of the automated electrophysiological characterization of ion channels in hiPSC-aCMs. This platform enables more efficient investigation of pathogenic variants and facilitates the development of targeted therapeutics for atrial arrhythmias and related channelopathies.

1. Introduction

In the past decade, human-induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes (hiPSC-CMs) have emerged as a promising model for studying cardiac diseases and drug screening [1,2,3,4,5,6]. Although differentiation efficiency has improved notably, the obtained cardiomyocytes are still immature compared to native human adult cardiomyocytes [7]. Moreover, some variability has been shown between laboratories and cell lines. Despite these challenges, the hiPSC-CM model is powerful as it presents different advantages to modelling human cardiac disease compared to animal models, which show notable differences in physiology and cellular regulation [8,9].

The hiPSC-CM model allows for the generation of chamber-specific cardiomyocytes using different protocols [5,10,11], which is an important advantage for modelling specific heart diseases and developing novel therapies to advance precision medicine. Moreover, the advancement of genome editing technology using CRISPR/Cas9 and other systems has allowed the creation of genetically engineered cell lines harbouring different genetic risk variants associated with inherited arrhythmic syndromes and their isogenic control lines. In line with this, hiPSC-CMs have been successfully used as models to study different arrhythmic diseases such as long QT syndrome (LQTS) [12,13], Brugada syndrome [14], catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (CPVT) [15,16], Timothy syndrome [17], and atrial fibrillation (AF) [18,19].

Inherited arrhythmic syndromes usually involve abnormalities in cardiac ion channels or proteins associated with ion channels [20]. To assess the functionality of the ion channels for this disease group, the patch-clamp technique remains the gold standard for in vitro electrophysiology experiments. However, it presents different challenges as it is a low-throughput complex technique even with a highly experienced experimentalist [21]. Thus, there has been a high interest in developing automated patch-clamp technology to address the previously mentioned challenges [22,23,24,25]. Although automated patch-clamp technology presents some limitations, such as less consistency in high-quality spatial and temporal voltage control, it has been used in different cells, including hiPSC-CMs [26,27,28]. However, most studies using automated patch-clamp technology have been performed in hiPSC-derived ventricular CMs (hiPSC-vCMs), whose channel expression differs from hiPSC-derived atrial CMs (hiPSC-aCMs). Moreover, although sodium (INa) and L-type calcium currents (ICaL) have been successfully recorded in hiPSC-vCMs [29], the transient outward potassium current (Ito) and the ultrarapid component of the delayed rectifier current (IKur) recordings in hiPSC-CMs have exhibited variability [30,31,32], and further investigation is needed. Here, we aim to establish a set of protocols to characterize different ion currents in hiPSC-aCMs that allows for the use of automated patch-clamp technology to study the impact of genetic variants associated with atrial arrhythmias on ion currents.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Differentiation of hiPSC into Atrial Cardiomyocytes

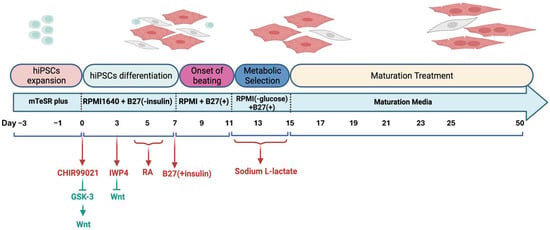

To study atrial arrhythmias, directed differentiation of hiPSCs into hiPSC-aCMs was performed using a protocol that has been previously refined and optimized [4,5]. The cell line was provided by Prof. Bjorn Knollman. As shown in Figure 1, hiPSCs were cultured in mTeSR Plus (05850, StemCell Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada) medium supplemented with a Rho-associated kinase (ROCK) inhibitor, Y-27632 dihydrochloride (1254, TOCRIS, Bio-Techne Canada, Toronto, ON, Canada), on Matrigel-coated substrates (356234, Corning, New York, NY, USA) (0.25 mg per 6-well plate, dissolved in DMEM/F-12 medium). hiPSCs were maintained in fresh mTeSR Plus medium for 3 days to achieve a confluent cell density between 70% and 90%. To initiate differentiation, hiPSCs were cultured in Roswell Park Memorial Institute Medium (RPMI) 1640 basal medium (11875093, ThermoFisher Scientific, Mississauga, ON, Canada) supplemented with 2% B27 without insulin (A18956-01, Gibco, ThermoFisher Scientific, Mississauga, ON, Canada), along with 12 µM CHIR99021 (2520691, Biogems, Westlake Village, CA, USA) for 24 h to indirectly activate the Wnt signalling pathway by inhibiting Glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3). Following this, the cells were treated with 5 µM IWP4 (5214, TOCRIS, Bio-Techne Canada, Toronto, ON, Canada), a Wnt inhibitor, in combination with RPMI 1640 and 2% B27 without insulin. aCMs differentiation was induced by administering 0.75 µM retinoic acid (RA) (R2625-50MG, Sigma-Aldrich, Oakville, ON, Canada), the biologically active form of vitamin A, every 24 h from days 4 to 6. This RA exposure during a specific developmental window converts a subset of cardiovascular mesoderm cells into aCMs. The medium was then switched to RPMI 1640 supplemented with 2% B27 50X with insulin (17504-044, Gibco, ThermoFisher Scientific, Mississauga, ON, Canada), with subsequent medium changes every 2 days. By days 8 to 11, spontaneous beating of hiPSC-aCMs was typically observed. Purification of cardiomyocytes was conducted by introducing sodium L-lactate (71718, Sigma-Aldrich, Oakville, ON, Canada) while omitting glucose from the media. Subsequently, the hiPSC-aCMs underwent a maturation process for 5 weeks in maturation media based on Feyen et al. [33] to improve their electrophysiological characteristics.

Figure 1.

hiPSC-aCMs differentiation, metabolic selection, and maturation protocol. GSK-3, glycogen synthase kinase 3; RA, retinoic acid.

2.2. Preparation of hiPSC-aCMs for Automated Patch-Clamp Experiments

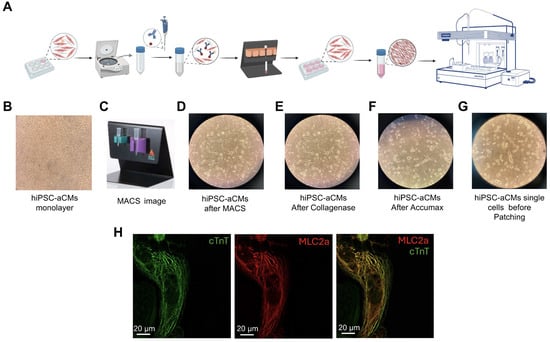

To ensure optimal cell membrane quality for subsequent automated patch-clamp experiments, we developed an optimized protocol for hiPSC-aCM preparation (see the workflow shown in Figure 2A). Although monolayers of hiPSC-aCMs (Figure 2B) underwent metabolic selection between days 11 and 15 of differentiation to decrease the number of non-cardiomyocyte cells within the culture, we designed a second purification step using magnetic-activated cell sorting technology (MACS®; Miltenyi Biotec, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) (Figure 2C) after 5 weeks of maturation treatment to further purify the atrial cardiomyocytes. A negative selection protocol to target the non-cardiomyocytes was used, which typically allowed us to obtain over 90% hiPSC-aCMs (Figure 2D). After purification, hiPSC-aCMs were seeded at a low density to foster single-beating cells within each well, totaling approximately 600,000 hiPSC-aCMs per well after replating. To confirm that the majority of the low-density hiPSC-CMs exhibit an atrial phenotype, immunocytochemistry was performed using antibodies against cardiac troponin T (cTnT), a general cardiomyocyte marker, and myosin light chain 2a (MLC2a), a marker specific to atrial cardiomyocytes. As shown in Figure 2H, a representative single cardiomyocyte displayed substantial expression and co-localization of MLC2a with cTnT, supporting the identification of the cell as an atrial cardiomyocyte. These cells underwent a recovery period of approximately 2 weeks before dissociation for patch-clamp experiments, so the recordings were obtained from 9-week-old cells.

Figure 2.

Optimized preparation protocol for hiPSC-aCMs using magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACS®). (A) Schematic workflow representation of the preparation process of hiPSC-aCMs for electrophysiological analysis using the Patchliner system. (B) hiPSC-aCM monolayer (10X objective). (C) Magnetic activated cell sorting Miltenyi set up. (D) Plated hiPSC-aCMs after purification with MACS® (10X objective). (E) hiPSC-aCMs illustration after 30 min of incubation in Collagenase B. (F) hiPSC-aCMs illustration after 10 min of incubation in Accumax. (G) Resuspended dissociated single atrial cardiomyocytes. (H) Fluorescence images captured using a confocal SP8 60X objective showing immunolabeling of cardiac troponin T (cTnT, green), myosin light chain 2a (MLC2a, red), and their overlay image.

Following recovery, hiPSC-aCMs were dissociated using a customized protocol utilizing Collagenase B (1 mM) (LS004147, Worthington Biochemical Corporation, Lakewood, NJ, USA) and AccumaxTM (07921, STEM CELL Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada). hiPSC-aCMs were incubated in Collagenase B for 15–30 min, depending on the maturation stage of the cells (Figure 2E). The more mature the cells, the longer the incubation time that was required. After the suitable incubation time with Collagenase B, the enzyme was removed, and the cells were incubated in AccumaxTM as the secondary digestive enzyme. AccumaxTM incubation time varied in the 5–15 min range, depending on the aforementioned parameters (Figure 2F). The resulting hiPSC-aCMs were counted and resuspended in a 1:1 mixture of RPMI supplemented with B27 and external solution and then transferred to the Patchliner cell hotel for experimental procedures (Figure 2G).

2.3. Automated Patch-Clamp Technique

Electrophysiological recordings were performed using a Patchliner (Nanion Technologies GmbH, Munich, Germany) automated patch-clamp rig. The low-density mature hiPSC-aCMs were freshly isolated with the described optimized dissociation protocol and kept in suspension at 12 °C. The pipette, chip wagon, and measure head temperature were set at 25 °C in all the experiments to ensure consistency. Medium-resistance NPC-16 chips (1.8–3 MΩ) were used in all experiments, as they resulted in a significantly higher catch rate (4–6 cells out of 8) compared to low- and high-resistance chips. A summary table showing the number of cells expressing the current of interest relative to the total number of captured cells is shown in Table 1. Cells that met the criteria of >200 MΩ seal resistance and <10 MΩ series resistance were included in the analysis. In addition, following multiple recordings from both mature and immature cells, a quality-control criterion was established based on the presence of both detectable INa and Ito currents, which are hallmark features of atrial electrophysiology and may indicate a more mature phenotype. Only cells that met these electrophysiological and quality-control criteria were used for subsequent analyses.

Table 1.

Electrophysiological parameters for each recorded current. The table shows the % of cells expressing the currents and the electrophysiological parameters recorded for each current. The % of cells expressing the current is presented as the proportion of cells exhibiting the current of interest relative to the total number of captured cells. Only cells meeting the criteria mentioned above were used for subsequent analyses. The electrophysiological parameters are expressed as the mean ± SEM, with the number of cells contributing to each parameter’s mean indicated in parentheses.

2.3.1. Solutions and Specific Protocols Used for Electrophysiological Recordings

Nanion’s standard internal, external, and seal enhancer solutions (whose compositions are specified below) were used to record most of the desired ion currents. Nevertheless, slight adjustments to these solutions were necessary for the accurate measurement of certain currents included in this study. The details of these adjustments and the specific protocols are outlined in the subsections related to each current. Nanion extracellular standard solution for recording Na+ and K+ currents contained the following (in mM): 140 NaCl, 4 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 5 D-Glucose monohydrate, and 10 Hepes (pH = 7.4, Osm = 298 mOsmol).

The standard intracellular solution for recording Na+ and Ca2+ currents contained the following (in mM): 50 CsCl, 10 NaCl, 60 CsF, 20 EGTA, and 10 HEPES (pH 7.2, Osm = 285 mOsmol). The standard intracellular solution for recording K+ currents contained the following (in mM): 50 KCl, 10 NaCl, 60 K-Fluoride, 20 EGTA, and 10 Hepes (pH = 7.2, Osm = 285 mOsmol).

The seal enhancer solution contained the following (in mM): 80 NaCl, 3 KCl, 10 MgCl2, 35 CaCl2, and 10 Hepes (pH = 7.4, Osm = 298 mOsmol).

2.3.2. Measurement of Na+ Current

Nanion standard extracellular, intracellular, and seal enhancer solutions were utilized to record INa. However, to achieve improved voltage control in the INa recordings, experiments were conducted using extracellular solutions with a reduced extracellular sodium concentration ([Na+]o) of 30% (42 mM) and 10% (14 mM) relative to the standard solution. An I-V step protocol was used to study the current-voltage relationship of INa. Cells were held at a holding potential of −100 mV, and 20 ms depolarizing voltage steps were applied from −80 mV to +40 mV in 10 mV increments.

2.3.3. Measurement of L-Type Calcium Current

The extracellular solution used to record ICaL was previously reported by Li et al. [26] and contained (in mM) 150 TEA-Cl, 10 D-glucose monohydrate, 10 HEPES, 1 MgCl2, and 2 CaCl2 (pH = 7.4). Nanion intracellular and seal enhancer standard solutions were used. On the day of the experiment, 0.3 mM Na3GTP, 5 mM ATP (Mg salt), and 5 mM BAPTA were freshly added to minimize current rundown. An I-V step protocol was used to determine the voltage-dependency of the ICaL. Cells were held at a holding potential of −80 mV, followed by a 100 ms pre-pulse step to −40 mV to inactivate Na+ channels and subsequent 200 ms depolarizing voltage steps from −40 to +40 mV in 10 mV increments. Steady-state ICaL was recorded using a pacing interval of 2 s. Currents were evoked by applying a 50 ms pre-pulse from −80 mV to −40 mV, followed by a 200 ms depolarizing step to 0 mV. The ICaL density was measured as the peak current normalized to cell capacitance. The recordings were obtained in control conditions and after incubation with 1 µM BAY-K (an L-type calcium channel-specific activator) and 1 µM nifedipine (a L-type calcium channel blocker).

2.3.4. Measurement of Major Atrial Potassium Repolarizing Currents

Nanion Standard extracellular, intracellular, and seal enhancer solutions were used to record the major atrial K+ repolarizing currents. The voltage-dependence of the K+ current was determined using an I-V step protocol. Cells were held at a holding potential of −80 mV, and 500 ms depolarizing voltage steps were applied from −40 to +50 mV in 10 mV increments, following a 100 ms step to −40 mV to inactivate Na+ channels. The protocol was performed under control conditions, and after incubation with the voltage-gated potassium channel inhibitor 4-aminopyridine (4-AP, 2 mM). The peak transient outward current (Ipeak) was measured as the difference between the peak current and the current at 200 ms from the beginning of the depolarization pulses. The sustained current (Isus) was measured as the current at 200 ms from the beginning of the depolarization pulses. The 4-AP-sensitive Ipeak includes contributions from both Ito and IKur, whereas the Isus primarily reflects IKur amplitude, since Ito and IKr are negligible at the time the Isus is being calculated, as previously demonstrated [34].

2.3.5. Measurement of Small-Conductance Calcium-Activated Potassium Current

Nanion standard extracellular, intracellular, and seal enhancer solutions were used to record the small-conductance calcium-activated potassium current (ISK). An I-V ramp voltage protocol was used to study the current-voltage relationship of ISK. The I-V ramp protocol was conducted over a voltage range of −80 mV to +60 mV at a rate of 28 mV/s. Current measurements were recorded in control conditions and after adding 100 nM of apamin, a specific SK channel inhibitor. The subtracted apamin-sensitive current was taken as ISK.

2.3.6. Measurement of Funny Current

Nanion standard extracellular, intracellular, and seal enhancer solutions were employed to record funny currents (If) resulting from hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated (HCN) channels. However, additional experiments were performed by increasing the extracellular K+ concentration to 30 mM. The If was activated from a holding potential of −40 mV by applying a series of 10 mV hyperpolarizing voltage test steps of 1s from −40 mV to −110 mV, followed by a depolarization step of 250 ms at +30 mV. The I-V relationship was determined by calculating the difference between the initial and final amplitude for the slowly activating current for each test voltage pulse. To investigate the effect of If inhibition, the specific inhibitor ivabradine (1 μM) was employed. Time constants of activation (τact) were obtained by fitting the current traces recorded during the voltage steps from −110 mV to −90 mV in experiments performed under control conditions with 30 mM extracellular K+ using a single exponential function. Values of time constants were used in this analysis from cells whose R2 values from the fitting were >0.9 for the three current traces at −90 mV, −100 mV, and −110 mV.

2.4. Data Analysis

2.4.1. Statistical Analysis

Quantitative variables are represented as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM), unless otherwise specified. As the variables were normally distributed, one-way or two-way ANOVA were conducted, followed by Tukey’s post hoc analysis. All statistical analyses were executed using GraphPad Prism 9.5.1. The specific tests employed are detailed in each figure’s caption.

2.4.2. Mathematical Analysis

The sodium equilibrium potential (ENa) at 25 °C was calculated using the Nernst Equation (1).

where R is the universal gas constant (8.3114 J), T is the temperature in degrees Kelvin, z is the valence of the ion, F is the Faraday constant (96.483 C/mol), and [Na+]o and [Na+]i are the concentrations of Na+ outside and inside, respectively.

ENa = (RT/zF) ln([Na+]o/[Na+]i)

The curve fitting for the Na+ conductance/maximal Na+ conductance (G/GMax)-voltage relation was obtained using Equation (2) [35]:

GNa = GMax/[1 + exp[(V − Vhalf)/s]

3. Results

3.1. Sodium Current Characterization in hiPSC-aCMs

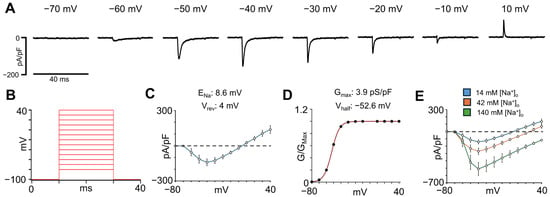

The INa plays a critical role in the initiation and propagation of the cardiac action potential (AP), determining the upstroke velocity and overall excitability of atrial cardiomyocytes. To characterize the INa density in isolated single hiPSC-aCMs, the voltage-clamp protocol shown in Figure 3B was used. As illustrated in the representative INa recordings normalized to membrane capacitance (pA/pF) in Figure 3A, hiPSC-aCMs displayed robust inward INa that activated upon depolarization. The current-voltage (I-V) relationship revealed that INa increased with depolarization and reached a maximal peak amplitude of −141 ± 29 pA/pF (n = 11) at −40 mV under 14 mM [Na]o (Figure 3C). The ENa, calculated using Equation (1) (see Methods), was 8.6 mV, which is consistent with the reversal potential (Vrev) obtained from the I-V relationship (4 mV), confirming accurate voltage control. From the same recordings, the conductance (G/GMax)-voltage relationship (Figure 3D) was calculated using the mean peak value at each potential. The curve was fitted using Equation (2), specified in the Methods section. The mean Vhalf was −52 ± 4 mV, and the GMax before normalization was 3.9 ± 0.3 pS/pF. Importantly, the voltage of peak INa occurred at the same voltage when different [Na+]o were used (Figure 3E).

Figure 3.

Sodium current characterization in hiPSC-aCMs using a [Na+]o concentration of 14 mM. (A) Representative INa traces at voltages between −70 and +10 mV normalized to membrane capacitance. (B) Voltage protocol used to obtain the current-voltage (I-V) relationship for the INa. (C) I-V relationship determined in single hiPSC-aCMs (n = 11). The equilibrium potential from Na+ (ENa) and the reversal potential (Vrev) calculated from the I-V relationship are shown above. (D) Normalized conductance (G/GMax)-voltage curve of the INa from the same hiPSC-aCMs used for the I-V relationship. The equation specified in the Methods section was used to fit this curve. The calculated values for the maximum conductance (GMax) and the half-activation voltage (Vhalf) are given above. (E) I-V relationships recorded in the same hiPSC-aCMs using 14 mM, 42 mM, and 140 mM [Na+]o.

3.2. L-Type Calcium Current Characterization in hiPSC-aCMs

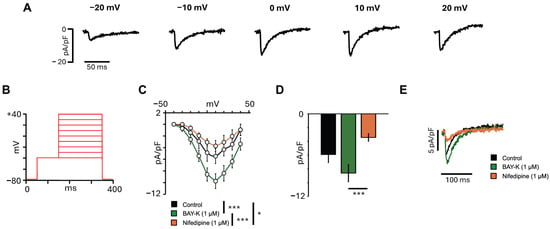

The ICaL is a key inward current that contributes to the plateau phase of the cardiac AP and is essential for excitation-contraction coupling in atrial cardiomyocytes. To characterize ICaL density in hiPSCs-aCMs, the voltage protocol shown in Figure 4B was used. As illustrated in the representative traces of Figure 4A, depolarizing voltage steps elicited inward calcium currents that reached the peak at +10 mV, consistent with the activation profile of ICaL. The I-V relationship (Figure 4C) revealed that the mean current density reached the peak at +10 mV and was significantly modulated by pharmacological agents, although no differences in the shape of the curve were observed. The mean current density recorded at 0 mV (Figure 4D) resulted in a 1.4-fold increase after incubation with BAY-K (1 µM), while subsequent treatment with nifedipine (1 µM) led to a significant 60.2% reduction (p = 0.0008). Representative ICaL traces for each condition are shown in Figure 4E.

Figure 4.

L-type calcium current characterization in hiPSC-aCMs. (A) Representative ICaL traces from a cell under control conditions at different voltages. (B) Voltage protocol used to obtain the current-voltage relationship for the ICaL. (C) I-V relationship recorded in the same hiPSC-aCMs in control and after the addition of the activator BAY-K (1 µM) and the inhibitor nifedipine (1 µM) (n = 9). Statistical significance was determined using a repeated-measures two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD post hoc. (D) Mean ICaL amplitude recorded at 0 mV in control and after the addition of BAY-K (1 µM) and subsequent addition of nifedipine (1 µM) (n = 9). Statistical significance was determined using a one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD post hoc. (E) Representative ICaL traces from the same cell recorded at 0 mV in control, after addition of BAY-K (1 µM) and subsequent addition of nifedipine (1 µM). The significant differences are indicated with the following: * p < 0.05; *** p < 0.001.

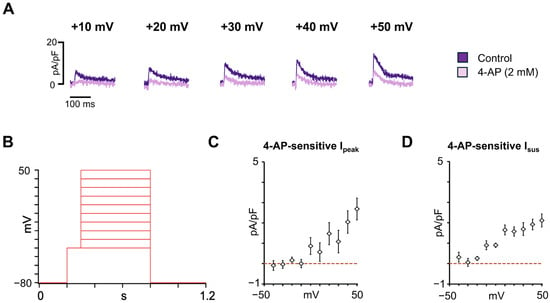

3.3. Characterization of the Major Atrial K+ Repolarizing Currents in hiPSC-aCMs

The Ito and IKur are 4-AP-sensitive and represent key atrial repolarizing currents that shape the early and late phases of the atrial AP, contributing to the electrophysiological distinction between atrial and ventricular cardiomyocytes. To characterize these repolarizing K+ currents in hiPSC-aCMs, the voltage-clamp protocol shown in Figure 5B was used. Figure 5A shows representative current traces recorded at different depolarizing voltages before and after the addition of 2 mM 4-AP, which reduced both the Ipeak and Isus. The I-V relationship of the 4-AP-sensitive Ipeak is presented in Figure 5C and was 2.7 ± 0.5 pA/pF (n = 6) at +50 mV. The I-V relationship for 4-AP-sensitive Isus, representing IKur, is shown in Figure 5D and was 2.1 ± 0.3 pA/pF (n = 6) at +50 mV. Together, these findings demonstrate that hiPSC-aCMs express functional 4-AP-sensitive Ito and IKur currents, supporting their electrophysiological identity as atrial-like cardiomyocytes.

Figure 5.

Major atrial potassium repolarizing currents characterization in hiPSC-aCMs. (A) Representative traces recorded at different voltages before (control) and after the addition of 4-AP (2 mM). (B) Voltage protocol used to obtain the current-voltage relationship of the major atrial K+ repolarizing currents. (C) Current-voltage (I-V) relationship for the 4-AP-sensitive peak transient outward current (Ipeak) (n = 6). (D) I-V relationship for the 4-AP-sensitive sustained current (Isus) (n = 6). Dashed lines in panels C and D indicate the zero current level.

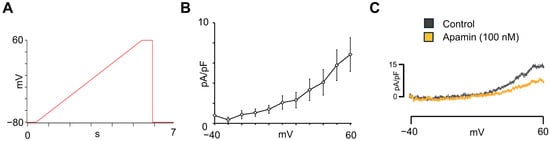

3.4. Apamin-Sensitive SK Current Characterization in hiPSC-aCMs

SK channels are important determinants of the atrial electrophysiological phenotype, as they contribute to repolarization and calcium-dependent regulation of AP duration (APD), and have recently been proposed as potential therapeutic targets for AF. To our knowledge, there is no published literature on the characterization of apamin-sensitive SK current in hiPSC-aCMs using automated patch-clamp technology. To investigate the presence of SK currents in hiPSC-aCMs, apamin-sensitive SK currents were recorded. The voltage-ramp protocol used for these recordings is shown in Figure 6A. The I-V relationship of the apamin-sensitive current, obtained by subtracting current traces recorded in the presence of apamin from those under control conditions, is presented in Figure 6B (n = 16). As shown in the representative traces in Figure 6C, a depolarizing voltage ramp elicited outward currents that were markedly reduced after the addition of 100 nM apamin. These results confirmed the functional expression of SK channels in hiPSC-aCMs.

Figure 6.

Small-conductance Ca2+-activated K+-current characterization in hiPSC-aCMs. (A) Voltage ramp protocol used to obtain the I-V relationship for the apamin-sensitive ISK. (B) Voltage-dependence of apamin-sensitive ISK obtained from hiPSC-aCMs (n = 16). (C) Representative current recordings before (control) and after the addition of apamin (100 nM).

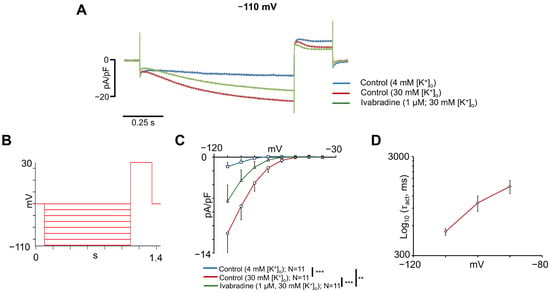

3.5. Funny Current Characterization in hiPSC-aCMs

The If contributes to the diastolic depolarization that controls spontaneous rhythm generation in the sinoatrial node (SAN), and alterations in HCN expression and function have been associated with atrial arrhythmias [36,37]. To characterize the If current in hiPSC-aCMs, we used an external solution (see Methods) containing 30 mM [K+]o, which produced an expected increase in If. Raising extracellular potassium has been shown to increase If amplitude in Purkinje fibres [38] and sinoatrial pacemaker cells [39], as well as in heterologous cells that express mammalian HCN forms [38,40,41]. To help identify the If, we used 1 μM ivabradine. This drug has been reported to inhibit If of the rabbit SAN with an EC50 of 1.5 mM [42].

Figure 7A shows representative traces recorded at −110 mV with 4 mM [K+]o, 30 mM [K+]o, and 30 mM [K+]o plus 1 µM ivabradine. The voltage protocol used to record the I-V relationships is shown in Figure 7B and consisted of a holding voltage of −40 mV and a series of subsequent hyperpolarizing test voltages. Statistical analysis of I-V relationships (Figure 7C) showed significant differences between the conditions (p = 0.0028). At −110 mV, the mean current density increased from −1.4 ± 0.6 pA/pF under 4 mM [K+]o to −11.1 ± 2.8 pA/pF with 30 mM [K+]o (n = 11, p < 0.01), and decreased to −6.4 ± 2.3 pA/pF after the addition of 1 μM ivabradine (n = 11, p < 0.01). Analysis of the time constants of current activation (Figure 7D) showed a voltage-dependent slowing of activation at less negative potentials, consistent with the gating properties of If channels. The observed voltage-dependence, sensitivity to ivabradine, and modulation by extracellular K+ confirm that hiPSC-aCMs express a functional If with properties resembling those reported in native cardiac pacemaker cells.

Figure 7.

Funny current characterization in hiPSC-aCMs. (A) Representative If traces recorded at −110 mV with 4 mM [K+]o, 30 mM [K+]o, and 30 mM [K+]o plus 1 μM ivabradine. (B) Voltage protocol used to obtain the current-voltage relationship of If. (C) Current-voltage (I-V) relationship for If with 4 mM [K+]o, 30 mM [K+]o, and 30 mM [K+]o plus 1 µM ivabradine. Statistical significance in panel (C) was determined using a repeated-measures two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD post hoc test. Multiple comparisons between conditions have been performed and are indicated with **: p < 0.01; ***: p < 0.001. (D) Voltage-dependent activation time constants (τact) obtained as described in Methods section for If current elicited at voltage steps from −110 mV to −90 mV in experiments performed under control conditions with 30 mM [K+]o. τact is in logarithmic scale, and n = 5–7 cells per voltage step.

4. Discussion

Alterations in the ion channels involved in the cardiac AP and/or Ca2+ handling proteins have been shown to underlie atrial electrical remodelling and ectopic activity, contributing to the appearance of atrial arrhythmias such as AF. Accordingly, several studies have linked genetic variants in genes encoding sodium (SCN5A, INa) [43], potassium (KCND3,Ito; KCNA5, IKur; KCNN2, ISK2; KCNN3, ISK3) [44,45,46,47], calcium (CACNB2 and CACNA2D4, ICaL) [48], and HCN4 (If) [49] channels with AF. Alterations in the function of these channels can modify AP properties, conduction velocity, and pacemaking frequency, thereby increasing susceptibility to AF. Thus, functional characterization of these variants in relevant human atrial tissue is essential.

Electrophysiological techniques, such as manual patch-clamp, have long been used to characterize ion channel functionality in cardiomyocytes derived from hiPSCs, human tissue, or animal models. However, because the manual patch-clamp technique is very labour-intensive and low-throughput, significant efforts have been made in the last decade to improve the automated patch-clamp systems [24,26,50]. One of the most critical factors for using automated patch-clamp systems is the preparation of high-quality unicellular cell suspensions. Here, we present an optimized protocol (Figure 2) to maintain membrane integrity while minimizing enzymatic and mechanical membrane damage and cytotoxicity, thereby enabling reliable recordings of atrial currents using an automated patch-clamp system. Thus, our protocol using the replating of hiPSC-aCMs at low density as single cells after purification using the MACS® technology facilitates a more efficient and gentle preparation process that allows the cells to recover from the replating procedure while maintaining membrane integrity.

Another challenge of using hiPSC-CMs has been their structural, electrophysiological, calcium handling, and metabolic immaturity compared to adult cardiomyocytes [51]. In this context, previous studies on hiPSC-CMs employing automated patch-clamp technology reported membrane capacitance values from 17 to 40 pF [28], whereas the cells obtained with our optimized protocol yielded values ranging from 11 to 103 pF (mean of 37.6 pF), closely approximating those measured in native human atrial myocytes [52]. These findings are consistent with Li et al. [26], who also reported improved maturation and INa density using refined dissociation procedures. Thus, the optimized protocol presented in this study enhances both electrophysiological stability and morphological maturation of hiPSC-aCMs, providing a physiologically relevant human atrial model.

Among the characterized ionic currents, the INa is fundamental for the rapid depolarization phase of the cardiac AP and determines conduction velocity and excitability in atrial tissue. Altered INa can slow conduction and facilitate re-entry, contributing to AF substrates. The SCN5 gene encodes the α subunit of the voltage-gated sodium channel (Nav1.5) and plays an essential role in the generation and propagation of the cardiac AP [53]. The INa peak density obtained in this study (−141 ± 29 pA/pF at −40 mV) aligns with manual patch-clamp data from native atrial myocytes of several species, including rabbit [54], dog [55], rat [56], and human [57]. Differences across studies may be attributed to differences in [Na+]o and β-subunit expression, notably SCN1B and SCN3B, which are known to regulate Nav1.5 expression and modulate current density [58,59]. In addition, reduced connexin 43 (GJA1) expression has been linked to decreased INa [60,61].

Our findings align with the study conducted by Li et al. [26] in hiPSC-CMs, reporting a peak INa of −187 pA/pF, which was two-fold greater than that reported in prior investigations [28], which they attributed to enhanced cellular maturation or a gentler cell dissociation process [26]. Together, these findings confirm that our protocol preserves functional sodium channels with densities comparable to native atrial cells.

The ICaL sustains the AP plateau phase and regulates excitation-contraction coupling. Alterations in ICaL can promote triggered activity, delayed afterdepolarizations, and abnormal calcium cycling, all of them key features in AF pathophysiology. The mean ICaL density recorded at 0 mV in this study was −5.9 ± 1.2 pA/pF, which aligns with previous studies in native human atrial myocytes using manual patch-clamp [7,60,62] and in native swine atrial myocytes using automated patch-clamp [63]. According to previous dose-response studies, a concentration of 1 μM nifedipine was used in this study to observe the maximum blocking effect [64,65]. However, a complete block of ICaL was not achieved in this study, possibly due to the recording sequence involving the activator BAY-K followed by the blocker. On the other hand, few studies have assessed ICaL in hiPSC-CMs, and reported values show considerable variability. Notably, approximately 10% of monolayer-derived hiPSC-CMs have been reported to lack detectable ICaL, potentially reflecting differences in maturation or differentiation [60,66]. Thus, this study provides standardized protocols and recording conditions for ICaL in hiPSC-aCMs, facilitating comparison with ICaL measured in native human atrial cardiomyocytes.

Voltage-gated potassium (Kv) channels play a pivotal role in cardiac repolarization and myocardial excitability. Among these, the Ito, comprising fast (Ito,f, primarily mediated by Kv4.3 and Kv4.2) and slow components (Ito,s, attributed to Kv1.4) [67,68], contributes to early repolarization [69] and exhibits marked differences between atrial and ventricular cells [70]. In addition, IKur is mediated by Kv1.5, which is highly expressed in human atria [71], and also participates in early atrial repolarization [72]. Alterations in both Ito and IKur have been implicated in arrhythmogenic disorders such as Brugada syndrome, early repolarization syndrome [73], and AF [34,46,47]. In this study, the Ipeak recorded in hiPSC-aCMs displayed a rapidly activating and inactivating profile, consistent with Ito properties previously reported in native human atrial cardiomyocytes [34,74]. On the other hand, the Isus recorded at +50 mV in this study, which is mainly attributed to IKur, aligns with previous reports on hiPSC-aCMs [32]. However, there is variability in Ito and IKur between other reports on hiPSC-CMs [31,75,76], which may be attributed to the maturity state of hiPSC-aCMs [77], variability in differentiation methods, and experimental conditions such as temperature or ionic composition of the bath solutions. Electrical heterogeneity has also been reported in isolated native human atrial myocytes [34], in which cells from the sinus rhythm and AF displayed differences in the K+ plateau phase (Ito-predominant, Isus-predominant, or intermediate pattern). Despite these discrepancies, the results obtained from the hiPSC-aCMs in this study reproduce atrial-specific repolarization, supporting their use as a platform to investigate the molecular mechanisms of KCND3 or KCNA5-associated AF variants and to evaluate drugs modulating repolarization.

Atrial repolarization is also modulated by SK channels, which have emerged as a novel therapeutic target for AF [78,79,80]. Previous studies using hiPSC-CMs lacking atrial specification reported that apamin, an SK-channel blocker, failed to prolong repolarization [81]. However, a recent study compared the effects of SK channel inhibition using patch-clamp technique in isolated hiPSC-aCMs and monolayer cultures of hiPSC-aCMs [82]. While only a minority of isolated hiPSC-aCMs responded to the application of the SK channel blocker UCL1684 (100 nM), all hiPSC-aCMs monolayers demonstrated a prolongation of AP duration at 50% repolarization (APD50) following UCL1684 treatment. The amplitude of the apamin-sensitive SK current reported in Figure 6 of this work is consistent with that observed in native human atrial myocytes using manual patch-clamp technique [83,84,85]. These results demonstrate that the hiPSC-aCMs reproduce atrial-specific repolarization features and provide a human model for testing SK-targeted therapies.

The If plays a crucial role in diastolic repolarization and cardiac pacemaking, and numerous studies have linked alterations in HCN channel expression or function with sinus node dysfunction, AF, and cardiomyopathies [86,87,88,89,90,91,92]. Due to the limited availability of human hearts and the anatomic inaccessibility of the SAN, obtaining human SAN biopsies is unfeasible. Consequently, most investigations into the physiological and pathological roles of If have been conducted in rabbit and murine SAN cells [42,91]. hiPSC-aCMs offer a human-based alternative since some display high If and low IK1, which are both hallmark features of the sinoatrial and atrioventricular pacemaker cells [29,39,93,94]. In the present study, the mean If density recorded at −110 mV was lower than values reported in previous studies involving human SAN diseased cells [90], hiPSCs-CMs[60,95,96], and human embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes [97], but showed the expected dependence of If on extracellular K+ concentration, even exceeding responses reported in rabbit SAN cells [39]. Although evidence suggests that HCN4 is the major form found in the hearts of mammals [92,98], the relative expression of HCN isoforms may vary depending on cardiomyocyte type, functional state, and maturation stage [99,100,101]. Previous studies have shown that the different HCN isoforms exhibit distinct activation kinetics [102,103,104], and the time activation constants of this study may be in the range of HCN2, HCN3, and HCN4 activation. However, the variability of If current density and activation kinetics across studies may be attributed to differences in experimental conditions and models, HCN isoform expression, or cell maturity. Nevertheless, cell-to-cell variation in If density and expression that was observed in the hiPSCs-aCMs of this study has also been noted in a previous report by our group in stem cell-derived atrial cells from mice [105]. In our previous report of stem cell-derived atrial cells from mice, higher levels of If correlated with faster beating rates [105], and this has also been observed in other animal pacemaker tissues [39,93]. Thus, it seems possible that there are hiPSC-CMs that possess high levels of If, beat at the highest rate, and act as primary pacemakers. These results reinforce the potential of hiPSC-aCMs for studying atrial pacemaking and AF-associated HCN4 variants.

Overall, this study advances the use of hiPSC-aCMs as a physiologically relevant platform for investigating human atrial electrophysiology and arrhythmogenesis. By enabling stable and reproducible recordings of multiple key ionic currents using automated patch-clamp technology, our work overcomes limitations of conventional manual approaches. The electrophysiological properties observed resemble those of native atrial cardiomyocytes, establishing a strong methodological foundation for mechanistic investigations into atrial arrhythmogenesis and the validation of atrial-selective pharmacological targets.

Although hiPSC-aCMs represent a promising model for investigating atrial arrhythmias and addressing some of the challenges of using animal models, other limitations should be considered. First, it is known that the maturation process undergone by the hiPSC-aCMs used in this study can result in a heterogeneous maturation state, which can influence ion channel expression and contribute to certain variability in the data. This may be particularly relevant when comparing results from hiPSCs-CMs and native cardiomyocytes obtained from animals or human tissue. Furthermore, as patch-clamp experiments are conducted in single cells, future integration with complementary techniques available in our laboratory (such as high-speed optical mapping or micro-optical mapping) in 2D monolayers and 3D structures would help understand the electrophysiological behaviour of cells within a tissue context. Finally, more detailed molecular characterization of the atrial phenotype will be an important goal for future studies.

5. Conclusions and Clinical Relevance

This study elucidates the feasibility of using automated patch-clamp technology to study the functional impact of genetic risk variants affecting the function of ion channels addressed in this study. Furthermore, it underscores the importance of using an optimized cell dissociation protocol to ensure the quality of the experiments, which has allowed us to record major atrial ionic currents such as INa, ICaL, Ito, IKur, ISK, and If. This approach provides a powerful platform for the functional characterization of ion channels, enabling the detection of electrophysiological dysfunction caused by pathogenic genetic variants. In conclusion, employing automated patch-clamp technology in hiPSC-aCMs models is a valuable and efficient tool for drug screening and precision medicine that can potentially facilitate the development of targeted therapies for atrial arrhythmias and ion channel-related disorders.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.F.T.; methodology, V.J.-S., H.B., P.C.R., E.A.A., T.W.C., L.H.-M. and G.F.T.; validation, V.J.-S., H.B., P.C.R., E.A.A., T.W.C., L.H.-M. and G.F.T.; formal analysis, V.J.-S., H.B. and G.F.T.; investigation, V.J.-S. and H.B.; resources, G.F.T.; data curation, V.J.-S., H.B. and G.F.T.; writing—original draft preparation, V.J.-S., H.B., P.C.R., E.A.A., T.W.C., L.H.-M. and G.F.T.; writing—review and editing, V.J.-S., H.B., P.C.R., E.A.A., T.W.C., L.H.-M. and G.F.T.; visualization, V.J.-S., H.B. and G.F.T.; supervision, G.F.T.; project administration, G.F.T.; funding acquisition, G.F.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, GIA G-24-0037532, and CIHR Project Grant PJT-191855 to G.F.T. L.H.M. is supported by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation and Universities (PID2023-152610OB-C21). V.J.-S. was supported by the Daniel Bravo Andreu Private Foundation Award for research stays abroad and the Michael Smith Health Research BC Research Trainee Award (RT-2023-3230).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

This work is dedicated to the memory of Glen Tibbits, who passed away just before the acceptance of this manuscript. We are grateful for his commitment, support and friendship during the completion of this project. The authors are very grateful for the infrastructural support from BC Children’s Hospital Foundation and the Mining for Miracles for the creation of the Cellular and Regenerative Medicine Centre (CRMC) at the BC Children’s Hospital Research Institute.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 4-AP | 4-aminopyridine |

| AF | Atrial fibrillation |

| AP | Action potential |

| APD | Action potential duration |

| cTnT | Cardiac troponin T |

| CPVT | Catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia |

| DAD | Delayed afterdepolarization |

| ENa | Sodium equilibrium potential |

| HCN | Hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated |

| hiPSC-aCMs | Human-induced pluripotent stem cell-derived atrial cardiomyocytes |

| hiPSC-CMs | Human-induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes |

| hiPSC-vCMs | Human-induced pluripotent stem cell-derived ventricular cardiomyocytes |

| ICaL | L-type calcium current |

| If | Funny current |

| IKur | Ultrarapid component of the delayed rectifier current |

| INa | Sodium current |

| ISK | Small-conductance calcium-activated potassium current |

| Ito | Transient outward potassium current |

| LQTS | Long QT syndrome |

| MACS | Magnetic-activated cell sorting |

| MLC2a | Myosin light chain 2a |

| SAN | Sinoatrial node |

| Vrev | Reversal potential |

References

- Arslanova, A.; Shafaattalab, S.; Lin, E.; Barszczewski, T.; Hove-Madsen, L.; Tibbits, G.F. Investigating Inherited Arrhythmias Using HiPSC-Derived Cardiomyocytes. Methods 2022, 203, 542–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezzerides, V.J.; Zhang, D.; Pu, W.T. Modeling Inherited Arrhythmia Disorders Using Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Cardiomyocytes. Circ. J. 2016, 81, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandão, K.O.; Tabel, V.A.; Atsma, D.E.; Mummery, C.L.; Davis, R.P. Human Pluripotent Stem Cell Models of Cardiac Disease: From Mechanisms to Therapies. Dis. Model. Mech. 2017, 10, 1039–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharanei, M.; Shafaattalab, S.; Sangha, S.; Gunawan, M.; Laksman, Z.; Hove-Madsen, L.; Tibbits, G.F. Atrial-Specific HiPSC-Derived Cardiomyocytes in Drug Discovery and Disease Modeling. Methods 2022, 203, 364–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunawan, M.G.; Sangha, S.S.; Shafaattalab, S.; Lin, E.; Heims-Waldron, D.A.; Bezzerides, V.J.; Laksman, Z.; Tibbits, G.F. Drug Screening Platform Using Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Atrial Cardiomyocytes and Optical Mapping. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2021, 10, 68–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsa, E.; Burridge, P.W.; Wu, J.C. Human Stem Cells for Modeling Heart Disease and for Drug Discovery. Sci. Transl. Med. 2014, 6, 239ps6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolanowski, T.J.; Antos, C.L.; Guan, K. Making Human Cardiomyocytes up to Date: Derivation, Maturation State and Perspectives. Int. J. Cardiol. 2017, 241, 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garg, P.; Garg, V.; Shrestha, R.; Sanguinetti, M.C.; Kamp, T.J.; Wu, J.C. Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Cardiomyocytes as Models for Cardiac Channelopathies: A Primer for Non-Electrophysiologists. Circ. Res. 2018, 123, 224–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaese, S.; Verheule, S. Cardiac Electrophysiology in Mice: A Matter of Size. Front. Physiol. 2012, 3, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cyganek, L.; Tiburcy, M.; Sekeres, K.; Gerstenberg, K.; Bohnenberger, H.; Lenz, C.; Henze, S.; Stauske, M.; Salinas, G.; Zimmermann, W.H.; et al. Deep Phenotyping of Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Atrial and Ventricular Cardiomyocytes. JCI Insight 2018, 3, e99941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, X.; Zhang, J.; Azarin, S.M.; Zhu, K.; Hazeltine, L.B.; Bao, X.; Hsiao, C.; Kamp, T.J.; Palecek, S.P. Directed Cardiomyocyte Differentiation from Human Pluripotent Stem Cells by Modulating Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling under Fully Defined Conditions. Nat. Protoc. 2013, 8, 162–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moretti, A.; Bellin, M.; Welling, A.; Jung, C.B.; Lam, J.T.; Bott-Flügel, L.; Dorn, T.; Goedel, A.; Höhnke, C.; Hofmann, F.; et al. Patient-Specific Induced Pluripotent Stem-Cell Models for Long-QT Syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 1397–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkateshappa, R.; Hunter, D.V.; Muralidharan, P.; Nagalingam, R.S.; Huen, G.; Faizi, S.; Luthra, S.; Lin, E.; Cheng, Y.M.; Hughes, J.; et al. Targeted Activation of Human Ether-à-Go-Go-Related Gene Channels Rescues Electrical Instability Induced by the R56Q+/- Long QT Syndrome Variant. Cardiovasc. Res. 2023, 119, 2522–2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, P.; Sallam, K.; Wu, H.; Li, Y.; Itzhaki, I.; Garg, P.; Zhang, Y.; Termglichan, V.; Lan, F.; Gu, M.; et al. Patient-Specific and Genome-Edited Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell–Derived Cardiomyocytes Elucidate Single-Cell Phenotype of Brugada Syndrome. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2016, 68, 2086–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslanova, A.; Shafaattalab, S.; Ye, K.; Asghari, P.; Lin, L.; Kim, B.; Roston, T.M.; Hove-Madsen, L.; van Petegem, F.; Sanatani, S.; et al. Using HiPSC-CMs to Examine Mechanisms of Catecholaminergic Polymorphic Ventricular Tachycardia. Curr. Protoc. 2021, 1, e320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.-H.; Haviland, S.; Wei, H.; Šarić, T.; Fatima, A.; Hescheler, J.; Cleemann, L.; Morad, M. Ca2+ Signaling in Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Cardiomyocytes (IPS-CM) from Normal and Catecholaminergic Polymorphic Ventricular Tachycardia (CPVT)-Afflicted Subjects. Cell Calcium 2013, 54, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazawa, M.; Hsueh, B.; Jia, X.; Pasca, A.M.; Bernstein, J.A.; Hallmayer, J.; Dolmetsch, R.E. Using Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells to Investigate Cardiac Phenotypes in Timothy Syndrome. Nature 2011, 471, 230–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babini, H.; Jiménez-Sábado, V.; Stogova, E.; Arslanova, A.; Butt, M.; Dababneh, S.; Asghari, P.; Moore, E.D.W.; Claydon, T.W.; Chiamvimonvat, N.; et al. HiPSC-Derived Cardiomyocytes as a Model to Study the Role of Small-Conductance Ca2+-Activated K+ (SK) Ion Channel Variants Associated with Atrial Fibrillation. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2024, 12, 1298007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seibertz, F.; Rubio, T.; Springer, R.; Popp, F.; Ritter, M.; Liutkute, A.; Bartelt, L.; Stelzer, L.; Haghighi, F.; Pietras, J.; et al. Atrial Fibrillation-Associated Electrical Remodelling in Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Atrial Cardiomyocytes: A Novel Pathway for Antiarrhythmic Therapy Development. Cardiovasc. Res. 2023, 119, 2623–2637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bezzina, C.R.; Lahrouchi, N.; Priori, S.G. Genetics of Sudden Cardiac Death. Circ. Res. 2015, 116, 1919–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlop, J.; Bowlby, M.; Peri, R.; Vasilyev, D.; Arias, R. High-Throughput Electrophysiology: An Emerging Paradigm for Ion-Channel Screening and Physiology. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2008, 7, 358–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fertig, N.; Blick, R.H.; Behrends, J.C. Whole Cell Patch Clamp Recording Performed on a Planar Glass Chip. Biophys. J. 2002, 82, 3056–3062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González, J.; Oades, K.; Leychkis, Y.; Harootunian, A.; Negulescu, P. Cell-Based Assays and Instrumentation for Screening Ion-Channel Targets. Drug Discov. Today 1999, 4, 431–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.G.; Vandenberg, J.I.; Ng, C.-A. Development of Automated Patch Clamp Assays to Overcome the Burden of Variants of Uncertain Significance in Inheritable Arrhythmia Syndromes. Front. Physiol. 2023, 14, 1294741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milligan, C.J.; Li, J.; Sukumar, P.; Majeed, Y.; Dallas, M.L.; English, A.; Emery, P.; Porter, K.E.; Smith, A.M.; McFadzean, I.; et al. Robotic Multiwell Planar Patch-Clamp for Native and Primary Mammalian Cells. Nat. Protoc. 2009, 4, 244–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Luo, X.; Ulbricht, Y.; Wagner, M.; Piorkowski, C.; El-Armouche, A.; Guan, K. Establishment of an Automated Patch-Clamp Platform for Electrophysiological and Pharmacological Evaluation of HiPSC-CMs. Stem Cell Res. 2019, 41, 101662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melgari, D.; Calamaio, S.; Frosio, A.; Prevostini, R.; Anastasia, L.; Pappone, C.; Rivolta, I. Automated Patch-Clamp and Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Cardiomyocytes: A Synergistic Approach in the Study of Brugada Syndrome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajamohan, D.; Kalra, S.; Duc Hoang, M.; George, V.; Staniforth, A.; Russell, H.; Yang, X.; Denning, C. Automated Electrophysiological and Pharmacological Evaluation of Human Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Cardiomyocytes. Stem Cells Dev. 2016, 25, 439–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goversen, B.; Becker, N.; Stoelzle-Feix, S.; Obergrussberger, A.; Vos, M.A.; van Veen, T.A.B.; Fertig, N.; de Boer, T.P. A Hybrid Model for Safety Pharmacology on an Automated Patch Clamp Platform: Using Dynamic Clamp to Join IPSC-Derived Cardiomyocytes and Simulations of IK1 Ion Channels in Real-Time. Front. Physiol. 2018, 8, 1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordeiro, J.M.; Nesterenko, V.V.; Sicouri, S.; Goodrow, R.J.; Treat, J.A.; Desai, M.; Wu, Y.; Doss, M.X.; Antzelevitch, C.; Di Diego, J.M. Identification and Characterization of a Transient Outward K+ Current in Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Cardiomyocytes. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 2013, 60, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devalla, H.D.; Schwach, V.; Ford, J.W.; Milnes, J.T.; El-Haou, S.; Jackson, C.; Gkatzis, K.; Elliott, D.A.; Chuva de Sousa Lopes, S.M.; Mummery, C.L.; et al. Atrial-like Cardiomyocytes from Human Pluripotent Stem Cells Are a Robust Preclinical Model for Assessing Atrial-Selective Pharmacology. EMBO Mol. Med. 2015, 7, 394–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilderink, S.; Devalla, H.D.; Bosch, L.; Wilders, R.; Verkerk, A.O. Ultrarapid Delayed Rectifier K+ Channelopathies in Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Cardiomyocytes. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feyen, D.A.M.; McKeithan, W.L.; Bruyneel, A.A.N.; Spiering, S.; Hörmann, L.; Ulmer, B.; Zhang, H.; Briganti, F.; Schweizer, M.; Hegyi, B.; et al. Metabolic Maturation Media Improve Physiological Function of Human IPSC-Derived Cardiomyocytes. Cell Rep. 2020, 32, 107925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero, R.; de la Fuente, M.G.; Gómez, R.; Barana, A.; Amorós, I.; Dolz-Gaitón, P.; Osuna, L.; Almendral, J.; Atienza, F.; Fernández-Avilés, F.; et al. In Humans, Chronic Atrial Fibrillation Decreases the Transient Outward Current and Ultrarapid Component of the Delayed Rectifier Current Differentially on Each Atria and Increases the Slow Component of the Delayed Rectifier Current in Both. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2010, 55, 2346–2354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgkin, A.L.; Huxley, A.F. The Dual Effect of Membrane Potential on Sodium Conductance in the Giant Axon of Loligo. J. Physiol. 1952, 116, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duhme, N.; Schweizer, P.A.; Thomas, D.; Becker, R.; Schröter, J.; Barends, T.R.M.; Schlichting, I.; Draguhn, A.; Bruehl, C.; Katus, H.A.; et al. Altered HCN4 Channel C-Linker Interaction Is Associated with Familial Tachycardia-Bradycardia Syndrome and Atrial Fibrillation. Eur. Heart J. 2013, 34, 2768–2775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macri, V.; Mahida, S.N.; Zhang, M.L.; Sinner, M.F.; Dolmatova, E.V.; Tucker, N.R.; McLellan, M.; Shea, M.A.; Milan, D.J.; Lunetta, K.L.; et al. A Novel Trafficking-Defective HCN4 Mutation Is Associated with Early-Onset Atrial Fibrillation. Heart Rhythm 2014, 11, 1055–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiFrancesco, D. Block and Activation of the Pace-maker Channel in Calf Purkinje Fibres: Effects of Potassium, Caesium and Rubidium. J. Physiol. 1982, 329, 485–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiFrancesco, D.; Ferroni, A.; Mazzanti, M.; Tromba, C. Properties of the Hyperpolarizing-activated Current (If) in Cells Isolated from the Rabbit Sino-atrial Node. J. Physiol. 1986, 377, 61–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macri, V.; Proenza, C.; Agranovich, E.; Angoli, D.; Accili, E.A. Separable Gating Mechanisms in a Mammalian Pacemaker Channel. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 35939–35946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moroni, A.; Barbuti, A.; Altomare, C.; Viscomi, C.; Morgan, J.; Baruscotti, M.; DiFrancesco, D. Kinetic and Ionic Properties of the Human HCN2 Pacemaker Channel. Pflügers Arch. 2000, 439, 618–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bucchi, A.; Barbuti, A.; DiFrancesco, D.; Baruscotti, M. Funny Current and Cardiac Rhythm: Insights from HCN Knockout and Transgenic Mouse Models. Front. Physiol. 2012, 3, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, T.M.; Michels, V.V.; Ballew, J.D.; Reyna, S.P.; Karst, M.L.; Herron, K.J.; Horton, S.C.; Rodeheffer, R.J.; Anderson, J.L. Sodium Channel Mutations and Susceptibility to Heart Failure and Atrial Fibrillation. JAMA 2005, 293, 447–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olesen, M.S.; Refsgaard, L.; Holst, A.G.; Larsen, A.P.; Grubb, S.; Haunsø, S.; Svendsen, J.H.; Olesen, S.-P.; Schmitt, N.; Calloe, K. A Novel KCND3 Gain-of-Function Mutation Associated with Early-Onset of Persistent Lone Atrial Fibrillation. Cardiovasc. Res. 2013, 98, 488–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellinor, P.T.; Lunetta, K.L.; Glazer, N.L.; Pfeufer, A.; Alonso, A.; Chung, M.K.; Sinner, M.F.; de Bakker, P.I.W.; Smith, N.L.; Smith, J.D.; et al. Common Variants in KCNN3 Are Associated with Lone Atrial Fibrillation. Nat. Genet. 2010, 42, 240–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, T.M.; Alekseev, A.E.; Liu, X.K.; Park, S.; Zingman, L.V.; Bienengraeber, M.; Sattiraju, S.; Ballew, J.D.; Jahangir, A.; Terzic, A. Kv1.5 Channelopathy Due to KCNA5 Loss-of-Function Mutation Causes Human Atrial Fibrillation. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2006, 15, 2185–2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christophersen, I.E.; Olesen, M.S.; Liang, B.; Andersen, M.N.; Larsen, A.P.; Nielsen, J.B.; Haunsø, S.; Olesen, S.-P.; Tveit, A.; Svendsen, J.H.; et al. Genetic Variation in KCNA5: Impact on the Atrial-Specific Potassium Current IKur in Patients with Lone Atrial Fibrillation. Eur. Heart J. 2013, 34, 1517–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weeke, P.; Muhammad, R.; Delaney, J.T.; Shaffer, C.; Mosley, J.D.; Blair, M.; Short, L.; Stubblefield, T.; Roden, D.M.; Darbar, D. Whole-Exome Sequencing in Familial Atrial Fibrillation. Eur. Heart J. 2014, 35, 2477–2483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.-H.; Hu, Y.-M.; Yin, G.-L.; Wu, P. Correlation between HCN4 Gene Polymorphisms and Lone Atrial Fibrillation Risk. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2019, 47, 2989–2993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haythornthwaite, A.; Stoelzle, S.; Hasler, A.; Kiss, A.; Mosbacher, J.; George, M.; Brüggemann, A.; Fertig, N. Characterizing Human Ion Channels in Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell–Derived Neurons. SLAS Discov. 2012, 17, 1264–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodola, F.; De Giusti, V.C.; Maniezzi, C.; Martone, D.; Stadiotti, I.; Sommariva, E.; Maione, A.S. Modeling Cardiomyopathies in a Dish: State-of-the-Art and Novel Perspectives on HiPSC-Derived Cardiomyocytes Maturation. Biology 2021, 10, 730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hove-Madsen, L.; Llach, A.; Bayes-Geniís, A.; Roura, S.; Font, E.R.; Ariís, A.; Cinca, J. Atrial Fibrillation Is Associated with Increased Spontaneous Calcium Release from the Sarcoplasmic Reticulum in Human Atrial Myocytes. Circulation 2004, 110, 1358–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fozzard, H.A.; Hanck, D.A. Structure and Function of Voltage-Dependent Sodium Channels: Comparison of Brain II and Cardiac Isoforms. Physiol. Rev. 1996, 76, 887–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caves, R.E.; Cheng, H.; Choisy, S.C.; Gadeberg, H.C.; Bryant, S.M.; Hancox, J.C.; James, A.F. Atrial-Ventricular Differences in Rabbit Cardiac Voltage-Gated Na+ Currents: Basis for Atrial-Selective Block by Ranolazine. Heart Rhythm 2017, 14, 1657–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burashnikov, A.; Di Diego, J.M.; Zygmunt, A.C.; Belardinelli, L.; Antzelevitch, C. Atrium-Selective Sodium Channel Block as a Strategy for Suppression of Atrial Fibrillation. Circulation 2007, 116, 1449–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caves, R.E.; Carpenter, A.; Choisy, S.C.; Clennell, B.; Cheng, H.; McNiff, C.; Mann, B.; Milnes, J.T.; Hancox, J.C.; James, A.F. Inhibition of Voltage-Gated Na+ Currents by Eleclazine in Rat Atrial and Ventricular Myocytes. Heart Rhythm O2 2020, 1, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakakibara, Y.; Wasserstrom, J.A.; Furukawa, T.; Jia, H.; Arentzen, C.E.; Hartz, R.S.; Singer, D.H. Characterization of the Sodium Current in Single Human Atrial Myocytes. Circ. Res. 1992, 71, 535–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rook, M.B.; Evers, M.M.; Vos, M.A.; Bierhuizen, M.F.A. Biology of Cardiac Sodium Channel Nav1.5 Expression. Cardiovasc. Res. 2012, 93, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cervantes, D.O.; Pizzo, E.; Ketkar, H.; Parambath, S.P.; Tang, S.; Cianflone, E.; Cannata, A.; Vinukonda, G.; Jain, S.; Jacobson, J.T.; et al. Scn1b Expression in the Adult Mouse Heart Modulates Na+ Influx in Myocytes and Reveals a Mechanistic Link between Na+ Entry and Diastolic Function. Am. J. Physiol. -Heart Circ. Physiol. 2022, 322, H975–H993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapotte-Baldacci, C.-A.; Pierre, M.; Djemai, M.; Pouliot, V.; Chahine, M. Biophysical Properties of NaV1.5 Channels from Atrial-like and Ventricular-like Cardiomyocytes Derived from Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 20685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, J.A.; Noorman, M.; Musa, H.; Stein, M.; de Jong, S.; van der Nagel, R.; Hund, T.J.; Mohler, P.J.; Vos, M.A.; van Veen, T.A.; et al. Reduced Heterogeneous Expression of Cx43 Results in Decreased Nav1.5 Expression and Reduced Sodium Current That Accounts for Arrhythmia Vulnerability in Conditional Cx43 Knockout Mice. Heart Rhythm 2012, 9, 600–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, F.; Flockerzi, V.; Kahl, S.; Wegener, J.W. L-Type Cav1.2 Calcium Channels: From In Vitro Findings to In Vivo Function. Physiol. Rev. 2014, 94, 303–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seibertz, F.; Rapedius, M.; Fakuade, F.E.; Tomsits, P.; Liutkute, A.; Cyganek, L.; Becker, N.; Majumder, R.; Clauß, S.; Fertig, N.; et al. A Modern Automated Patch-Clamp Approach for High Throughput Electrophysiology Recordings in Native Cardiomyocytes. Commun. Biol. 2022, 5, 969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eroglu, T.E.; Mohr, G.H.; Blom, M.T.; Verkerk, A.O.; Souverein, P.C.; Torp-Pedersen, C.; Folke, F.; Wissenberg, M.; van den Brink, L.; Davis, R.P.; et al. Differential Effects on Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest of Dihydropyridines: Real-World Data from Population-Based Cohorts across Two European Countries. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacother. 2020, 6, 347–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verkerk, A.O.; Marchal, G.A.; Zegers, J.G.; Kawasaki, M.; Driessen, A.H.G.; Remme, C.A.; de Groot, J.R.; Wilders, R. Patch-Clamp Recordings of Action Potentials From Human Atrial Myocytes: Optimization Through Dynamic Clamp. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 649414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzun, A.U.; Mannhardt, I.; Breckwoldt, K.; Horváth, A.; Johannsen, S.S.; Hansen, A.; Eschenhagen, T.; Christ, T. Ca(2+)-Currents in Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Cardiomyocytes Effects of Two Different Culture Conditions. Front. Pharmacol. 2016, 7, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niwa, N.; Nerbonne, J.M. Molecular Determinants of Cardiac Transient Outward Potassium Current (Ito) Expression and Regulation. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 2010, 48, 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wettwer, E.; Amos, G.J.; Posival, H.; Ravens, U. Transient Outward Current in Human Ventricular Myocytes of Subepicardial and Subendocardial Origin. Circ. Res. 1994, 75, 473–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiamvimonvat, N.; Chen-Izu, Y.; Clancy, C.E.; Deschenes, I.; Dobrev, D.; Heijman, J.; Izu, L.; Qu, Z.; Ripplinger, C.M.; Vandenberg, J.I.; et al. Potassium Currents in the Heart: Functional Roles in Repolarization, Arrhythmia and Therapeutics. J. Physiol. 2017, 595, 2229–2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shibata, E.F.; Drury, T.; Refsum, H.; Aldrete, V.; Giles, W. Contributions of a Transient Outward Current to Repolarization in Human Atrium. Am. J. Physiol. -Heart Circ. Physiol. 1989, 257, H1773–H1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellinghaus, P.; Scheubel, R.J.; Dobrev, D.; Ravens, U.; Holtz, J.; Huetter, J.; Nielsch, U.; Morawietz, H. Comparing the Global MRNA Expression Profile of Human Atrial and Ventricular Myocardium with High-Density Oligonucleotide Arrays. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2005, 129, 1383–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wettwer, E.; Hála, O.; Christ, T.; Heubach, J.F.; Dobrev, D.; Knaut, M.; Varró, A.; Ravens, U. Role of IKur in Controlling Action Potential Shape and Contractility in the Human Atrium: Influence of Chronic Atrial Fibrillation. Circulation 2004, 110, 2299–2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, E.K.; Springer, S.J.; Wang, W.; Dranoff, E.J.; Zhang, Y.; Kanter, E.M.; Yamada, K.A.; Nerbonne, J.M. Differential Expression and Remodeling of Transient Outward Potassium Currents in Human Left Ventricles. Circ. Arrhythm. Electrophysiol. 2018, 11, e005914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wagoner, D.R.; Pond, A.L.; McCarthy, P.M.; Trimmer, J.S.; Nerbonne, J.M. Outward K+ Current Densities and Kv1.5 Expression Are Reduced in Chronic Human Atrial Fibrillation. Circ. Res. 1997, 80, 772–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veerman, C.C.; Mengarelli, I.; Guan, K.; Stauske, M.; Barc, J.; Tan, H.L.; Wilde, A.A.M.; Verkerk, A.O.; Bezzina, C.R. HiPSC-Derived Cardiomyocytes from Brugada Syndrome Patients without Identified Mutations Do Not Exhibit Clear Cellular Electrophysiological Abnormalities. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 30967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, D.; Zhou, W.; Hamrick, S.K.; Tester, D.J.; Kim, C.S.J.; Barajas-Martinez, H.; Hu, D.; Giudicessi, J.R.; Antzelevitch, C.; Ackerman, M.J. Acacetin, a Potent Transient Outward Current Blocker, May Be a Novel Therapeutic for KCND3-Encoded Kv4.3 Gain-of-Function-Associated J-Wave Syndromes. Circ. Genom. Precis. Med. 2022, 15, e003238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, C.; Sönmez, M.; Krause, J.; Schwedhelm, E.; Bangfen, P.; Alihodzic, D.; Hansen, A.; Eschenhagen, T.; Christ, T. A Critical Role of Retinoic Acid Concentration for the Induction of a Fully Human-like Atrial Action Potential Phenotype in HiPSC-CM. Stem Cell Rep. 2023, 18, 2096–2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diness, J.G.; Kirchhoff, J.E.; Speerschneider, T.; Abildgaard, L.; Edvardsson, N.; Sørensen, U.S.; Grunnet, M.; Bentzen, B.H. The KCa2 Channel Inhibitor AP30663 Selectively Increases Atrial Refractoriness, Converts Vernakalant-Resistant Atrial Fibrillation and Prevents Its Reinduction in Conscious Pigs. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, M.M.; Qian, L.L.; Wang, R.X. Modulation of SK Channels: Insight into Therapeutics of Atrial Fibrillation. Heart Lung Circ. 2021, 30, 1130–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.-D.; Timofeyev, V.; Li, N.; Myers, R.E.; Zhang, D.-M.; Singapuri, A.; Lau, V.C.; Bond, C.T.; Adelman, J.; Lieu, D.K.; et al. Critical Roles of a Small Conductance Ca2+-Activated K+ Channel (SK3) in the Repolarization Process of Atrial Myocytes. Cardiovasc. Res. 2014, 101, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Lan, H.; El-Battrawy, I.; Li, X.; Buljubasic, F.; Sattler, K.; Yücel, G.; Lang, S.; Tiburcy, M.; Zimmermann, W.-H.; et al. Ion Channel Expression and Characterization in Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Cardiomyocytes. Stem Cells Int. 2018, 2018, 6067096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, A.S.; Ascione, R.; Marrion, N.V.; Harmer, S.C.; Hancox, J.C. In Situ Monolayer Patch Clamp of Acutely Stimulated Human IPSC-Derived Cardiomyocytes Promotes Consistent Electrophysiological Responses to SK Channel Inhibition. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 3185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez-Sabado, V.; Tarifa, C.; Casabella-Ramon, S.; Montiel, J.; Rodriguez-Font, E.; Olesen, M.S.; Hove-Madsen, L. The Rs13376333 Risk Allele Mimics the Effect of Atrial Fibrillation on SK-Current Density and Afterdepolarizations in Human Atrial Myocytes. Eur. Heart J. 2022, 43 (Suppl. 2), ehac544.2978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Yu, Y.; Lan, H.; Ou, X.; Yang, L.; Li, T.; Cao, J.; Zeng, X.; Li, M. Ca2+/Calmodulin-Dependent Protein Kinase II (CaMKII) Increases Small-Conductance Ca2+-Activated K+ Current in Patients with Chronic Atrial Fibrillation. Med. Sci. Monit. 2018, 24, 3011–3023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heijman, J.; Zhou, X.; Morotti, S.; Molina, C.E.; Abu-Taha, I.H.; Tekook, M.; Jespersen, T.; Zhang, Y.; Dobrev, S.; Milting, H.; et al. Enhanced Ca2+-Dependent SK-Channel Gating and Membrane Trafficking in Human Atrial Fibrillation. Circ. Res. 2023, 132, e116–e133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benzoni, P.; Campostrini, G.; Landi, S.; Bertini, V.; Marchina, E.; Iascone, M.; Ahlberg, G.; Olesen, M.S.; Crescini, E.; Mora, C.; et al. Human IPSC Modelling of a Familial Form of Atrial Fibrillation Reveals a Gain of Function of If and ICaL in Patient-Derived Cardiomyocytes. Cardiovasc. Res. 2020, 116, 1147–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiFrancesco, D. HCN4, Sinus Bradycardia and Atrial Fibrillation. Arrhythm. Electrophysiol. Rev. 2015, 4, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartiani, L.; Mannaioni, G.; Masi, A.; Novella Romanelli, M.; Cerbai, E. The Hyperpolarization-Activated Cyclic Nucleotide–Gated Channels: From Biophysics to Pharmacology of a Unique Family of Ion Channels. Pharmacol. Rev. 2017, 69, 354–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.; Sun, X.; Yuan, R.; Hou, X.; Wan, J.; Liao, B. HCN4 and Arrhythmias: Insights into Base Mutations. Mutat. Res. Rev. Mutat. Res. 2025, 795, 108534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verkerk, A.O.; Wilders, R. Pacemaker Activity of the Human Sinoatrial Node: Effects of HCN4 Mutations on the Hyperpolarization-Activated Current. EP Eur. 2014, 16, 384–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiFrancesco, D. Funny Channel Gene Mutations Associated with Arrhythmias. J. Physiol. 2013, 591, 4117–4124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, L.-C.; Rämö, J.T.; Jurgens, S.J.; Khurshid, S.; Chaffin, M.; Hall, A.W.; Morrill, V.N.; Wang, X.; Nauffal, V.; Sun, Y.V.; et al. The Impact of Common and Rare Genetic Variants on Bradyarrhythmia Development. Nat. Genet. 2025, 57, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munk, A.A.; Adjemian, R.A.; Zhao, J.; Ogbaghebriel, A.; Shrier, A. Electrophysiological Properties of Morphologically Distinct Cells Isolated from the Rabbit Atrioventricular Node. J. Physiol. 1996, 493, 801–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiFrancesco, D.; Noble, D. A Model of Cardiac Electrical Activity Incorporating Ionic Pumps and Concentration Changes. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. London. B Biol. Sci. 1985, 307, 353–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giannetti, F.; Benzoni, P.; Campostrini, G.; Milanesi, R.; Bucchi, A.; Baruscotti, M.; Dell’Era, P.; Rossini, A.; Barbuti, A. A Detailed Characterization of the Hyperpolarization-Activated “Funny” Current (If) in Human-Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell (IPSC)–Derived Cardiomyocytes with Pacemaker Activity. Pflug. Arch. 2021, 473, 1009–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.; Guo, L.; Fiene, S.J.; Anson, B.D.; Thomson, J.A.; Kamp, T.J.; Kolaja, K.L.; Swanson, B.J.; January, C.T. High Purity Human-Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Cardiomyocytes: Electrophysiological Properties of Action Potentials and Ionic Currents. Am. J. Physiol. -Heart Circ. Physiol. 2011, 301, H2006–H2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosman, A.; Sartiani, L.; Spinelli, V.; Del Lungo, M.; Stillitano, F.; Nosi, D.; Mugelli, A.; Cerbai, E.; Jaconi, M. Molecular and Functional Evidence of HCN4 and Caveolin-3 Interaction during Cardiomyocyte Differentiation from Human Embryonic Stem Cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2013, 22, 1717–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linscheid, N.; Logantha, S.J.R.J.; Poulsen, P.C.; Zhang, S.; Schrölkamp, M.; Egerod, K.L.; Thompson, J.J.; Kitmitto, A.; Galli, G.; Humphries, M.J.; et al. Quantitative Proteomics and Single-Nucleus Transcriptomics of the Sinus Node Elucidates the Foundation of Cardiac Pacemaking. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.; Torre, E.; Marrot, M.; Peters, C.H.; Feather, A.; Nichols, W.G.; Logantha, S.J.R.J.; Arshad, A.; Martis, S.A.; Ozturk, N.T.; et al. Identifying Sex Similarities and Differences in Structure and Function of the Sinoatrial Node in the Mouse Heart. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1488478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Khoury, N.; Mathieu, S.; Marger, L.; Ross, J.; El Gebeily, G.; Ethier, N.; Fiset, C. Upregulation of the Hyperpolarization-Activated Current Increases Pacemaker Activity of the Sinoatrial Node and Heart Rate during Pregnancy in Mice. Circulation 2013, 127, 2009–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Souza, A.; Bucchi, A.; Johnsen, A.B.; Logantha, S.J.R.J.; Monfredi, O.; Yanni, J.; Prehar, S.; Hart, G.; Cartwright, E.; Wisloff, U.; et al. Exercise Training Reduces Resting Heart Rate via Downregulation of the Funny Channel HCN4. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 3775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stieber, J.; Stöckl, G.; Herrmann, S.; Hassfurth, B.; Hofmann, F. Functional Expression of the Human HCN3 Channel. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 34635–34643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altomare, C.; Terragni, B.; Brioschi, C.; Milanesi, R.; Pagliuca, C.; Viscomi, C.; Moroni, A.; Baruscotti, M.; DiFrancesco, D. Heteromeric HCN1-HCN4 Channels: A Comparison with Native Pacemaker Channels from the Rabbit Sinoatrial Node. J. Physiol. 2003, 549, 347–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altomare, C.; Bucchi, A.; Camatini, E.; Baruscotti, M.; Viscomi, C.; Moroni, A.; DiFrancesco, D. Integrated Allosteric Model of Voltage Gating of HCN Channels. J. Gen. Physiol. 2001, 117, 519–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Whitaker, G.M.; Hove-Madsen, L.; Tibbits, G.F.; Accili, E.A. Hyperpolarization-activated Cyclic Nucleotide-modulated ‘HCN’ Channels Confer Regular and Faster Rhythmicity to Beating Mouse Embryonic Stem Cells. J. Physiol. 2008, 586, 701–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).