PLGA Nanoencapsulation Enhances Immunogenicity of Heat-Shocked Melanoma Tumor Cell Lysates

Highlights

- PLGA nanoencapsulation preserves and significantly enhances the immunogenic activity of TRIMEL, a clinically validated heat-shock melanoma cell lysate used in TAPCells and TRIMELVax.

- NP-TRIMEL maintains functional stability for at least 24 weeks at 4 °C, enabling efficient TAPCells differentiation and generation of cytotoxic lymphocytes with >100-fold dose-normalized potency compared with soluble TRIMEL.

- Stabilizing TRIMEL at 4 °C overcomes an important logistical barrier limiting large-scale deployment of TAPCells/TRIMELVax-like vaccines.

- Nanoencapsulation represents a feasible translational path to next-generation whole-tumor-cell vaccines, enabling improved accessibility, dose-sparing, and broader clinical applicability.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

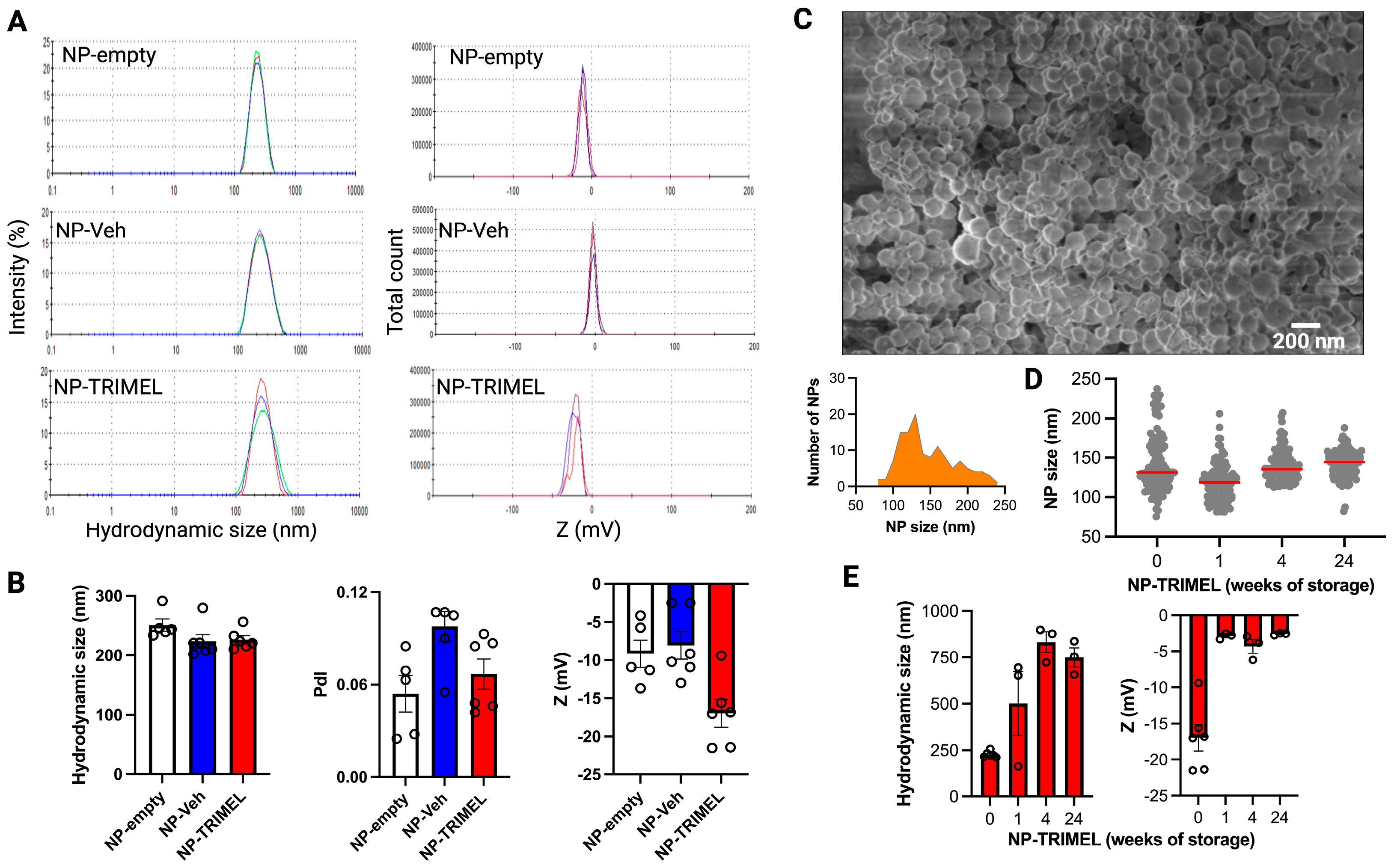

3.1. Physicochemical Characterization of NP-TRIMEL

3.2. TRIMEL Encapsulation Efficiency and Peptide Preservation in TRIMEL-NP

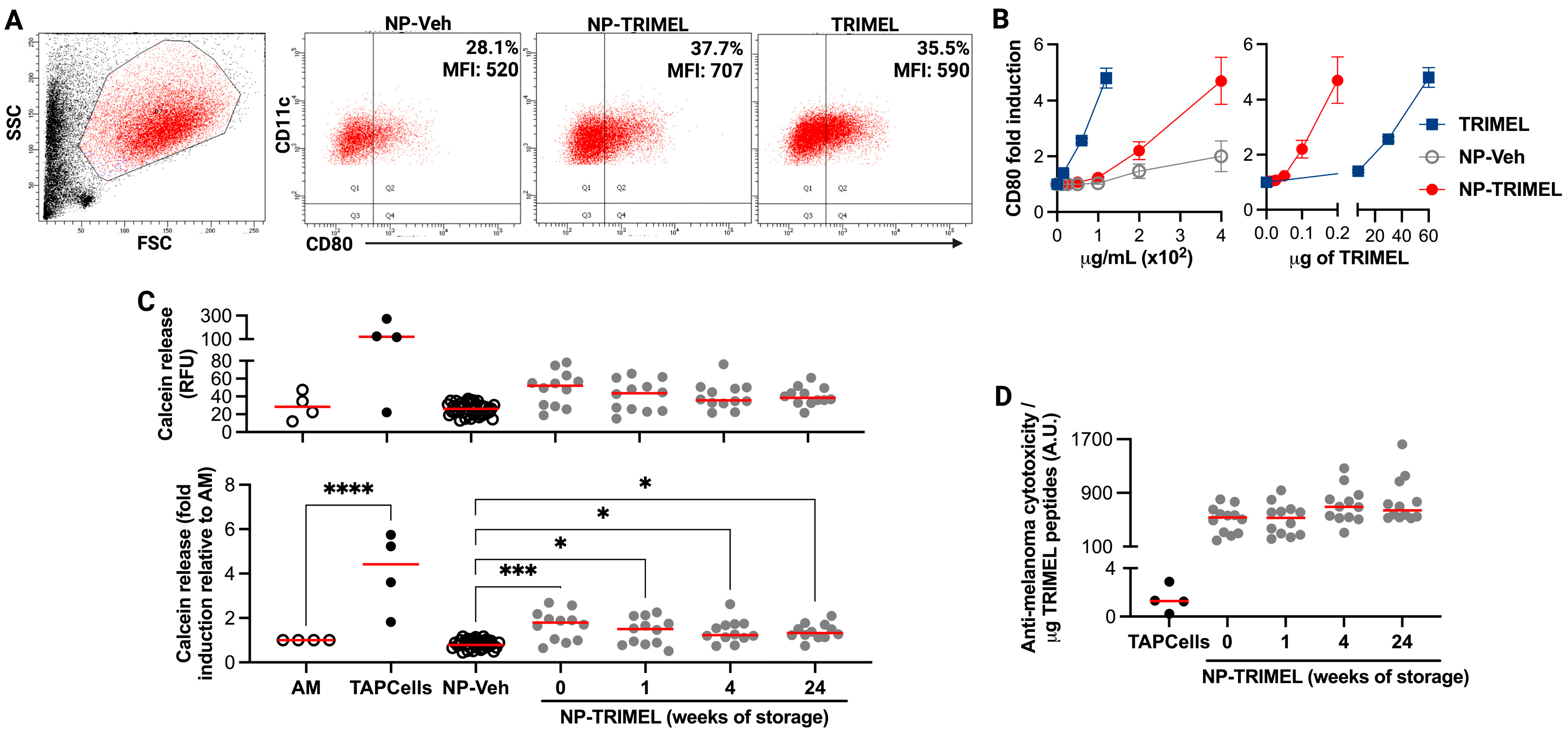

3.3. Biological Activity of NP-TRIMEL

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AM | Activated monocytes |

| APC | Antigen-presenting cell |

| A.U. | Arbitrary units |

| CCH | Concholepas concholepas hemocyanin |

| DC | Dendritic cell |

| DCM | Dichloromethane |

| DLS | Dynamic light scattering |

| DAMPs | Damage-associated molecular patterns |

| EDS | Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy |

| E:T | Effector-to-target ratio |

| FE-SEM | Field-emission scanning electron microscopy |

| FBS | Fetal bovine serum |

| GM-CSF | Granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor |

| HLA | Human leukocyte antigen |

| HSP | Heat-shock protein |

| IL-2 | Interleukin-2 |

| IL-4 | Interleukin-4 |

| NP | Nanoparticle |

| PBMC | Peripheral blood mononuclear cells |

| PBL | Peripheral blood lymphocytes |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline |

| PdI | Polydispersity index |

| PLGA | Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) |

| PVA | Polyvinyl alcohol |

| TLR | Toll-like receptor |

| WTC | Whole tumor cell (vaccine) |

References

- Arnold, M.; Singh, D.; Laversanne, M.; Vignat, J.; Vaccarella, S.; Meheus, F.; Cust, A.E.; de Vries, E.; Whiteman, D.C.; Bray, F. Global Burden of Cutaneous Melanoma in 2020 and Projections to 2040. JAMA Dermatol. 2022, 158, 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Restifo, N.P.; Smyth, M.J.; Snyder, A. Acquired resistance to immunotherapy and future challenges. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2016, 16, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, A.C.; Zappasodi, R. A decade of checkpoint blockade immunotherapy in melanoma: Understanding the molecular basis for immune sensitivity and resistance. Nat. Immunol. 2022, 23, 660–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, H.N.; Zou, W. Beyond the Barrier: Unraveling the Mechanisms of Immunotherapy Resistance. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2024, 42, 521–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Baños, A.; Gleisner, M.A.; Flores, I.; Pereda, C.; Navarrete, M.; Araya, J.P.; Navarro, G.; Quezada-Monrás, C.; Tittarelli, A.; Salazar-Onfray, F. Whole tumour cell-based vaccines: Tuning the instruments to orchestrate an optimal antitumour immune response. Br. J. Cancer 2023, 129, 572–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, M.N.; Pereda, C.; Segal, G.; Muñoz, L.; Aguilera, R.; González, F.E.; Escobar, A.; Ginesta, A.; Reyes, D.; González, R.; et al. Prolonged survival of dendritic cell-vaccinated melanoma patients correlates with tumor-specific delayed type IV hypersensitivity response and reduction of tumor growth factor beta-expressing T cells. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 27, 945–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera, R.; Saffie, C.; Tittarelli, A.; González, F.E.; Ramírez, M.; Reyes, D.; Pereda, C.; Hevia, D.; García, T.; Salazar, L.; et al. Heat-shock induction of tumor-derived danger signals mediates rapid monocyte differentiation into clinically effective dendritic cells. Clin. Cancer Res. 2011, 17, 2474–2483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, D.; Salazar, L.; Espinoza, E.; Pereda, C.; Castellón, E.; Valdevenito, R.; Huidobro, C.; Becker, M.I.; Lladser, A.; López, M.N.; et al. Tumour cell lysate-loaded dendritic cell vaccine induces biochemical and memory immune response in castration-resistant prostate cancer patients. Br. J. Cancer 2013, 109, 1488–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleisner, M.A.; Pereda, C.; Tittarelli, A.; Navarrete, M.; Fuentes, C.; Ávalos, I.; Tempio, F.; Araya, J.P.; Becker, M.I.; González, F.E.; et al. A heat-shocked melanoma cell lysate vaccine enhances tumor infiltration by prototypic effector T cells inhibiting tumor growth. J. Immunother. Cancer 2020, 8, e000999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tittarelli, A.; Pereda, C.; Gleisner, M.A.; López, M.N.; Flores, I.; Tempio, F.; Lladser, A.; Achour, A.; González, F.E.; Durán-Aniotz, C.; et al. Long-Term Survival and Immune Response Dynamics in Melanoma Patients Undergoing TAPCells-Based Vaccination Therapy. Vaccines 2024, 12, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ledford, H. Therapeutic cancer vaccine survives biotech bust. Nature 2015, 519, 17–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A. Pharmaceutics of Vaccine Delivery: Current Trends and Future Prospects. Am. J. Pharm. 2023, 4, 13–23. [Google Scholar]

- Venturini, J.; Chakraborty, A.; Baysal, M.A.; Tsimberidou, A.M. Developments in nanotechnology approaches for the treatment of solid tumors. Exp. Hematol. Oncol. 2025, 14, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbery, B.G.; Lukesh, N.R.; Bachelder, E.M.; Ainslie, K.M. Biodegradable Polymers for Application as Robust Immunomodulatory Biomaterial Carrier Systems. Small 2025, e2409422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasad, S.; Cody, V.; Saucier-Sawyer, J.K.; Saltzman, W.M.; Sasaki, C.T.; Edelson, R.L.; Birchall, M.A.; Hanlon, D.J. Polymer nanoparticles containing tumor lysates as antigen delivery vehicles for dendritic cell-based antitumor immunotherapy. Nanomedicine 2011, 7, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasad, S.; Cody, V.; Saucier-Sawyer, J.K.; Fadel, T.R.; Edelson, R.L.; Birchall, M.A.; Hanlon, D.J. Optimization of stability, encapsulation, release, and cross-priming of tumor antigen-containing PLGA nanoparticles. Pharm. Res. 2012, 29, 2565–2577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iranpour, S.; Nejati, V.; Delirezh, N.; Biparva, P.; Shirian, S. Enhanced stimulation of anti-breast cancer T cells responses by dendritic cells loaded with poly lactic-co-glycolic acid (PLGA) nanoparticle encapsulated tumor antigens. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016, 35, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kohnepoushi, C.; Nejati, V.; Delirezh, N.; Biparva, P. Poly Lactic-co-Glycolic Acid Nanoparticles Containing Human Gastric Tumor Lysates as Antigen Delivery Vehicles for Dendritic Cell-Based Antitumor Immunotherapy. Immunol. Investing. 2019, 48, 794–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.D.; Lü, K.L.; Yu, J.; Du, H.J.; Fan, C.Q.; Chen, L. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of DC-targeting PLGA nanoparticles encapsulating heparanase CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell epitopes for cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2022, 71, 2969–2983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berti, C.; Graciotti, M.; Boarino, A.; Yakkala, C.; Kandalaft, L.E.; Klok, H.A. Polymer Nanoparticle-Mediated Delivery of Oxidized Tumor Lysate-Based Cancer Vaccines. Macromol. Biosci. 2022, 22, e2100356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, K.; Pack, D.W.; Klibanov, A.M.; Langer, R. Visual evidence of acidic environment within degrading poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) microspheres. Pharm. Res. 2000, 17, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, V.-T.; Karam, J.-P.; Garric, X.; Coudane, J.; Benoît, J.-P.; Montero-Menei, C.N.; Venier-Julienne, M.-C. Protein-loaded PLGA-PEG-PLGA microspheres: A tool for cell therapy. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2012, 45, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, L.J.; Tacken, P.J.; Eich, C.; Rueda, F.; Torensma, R.; Figdor, C.G. Controlled release of antigen and Toll-like receptor ligands from PLGA nanoparticles enhances immunogenicity. Nanomedicine 2017, 12, 491–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, R.; Smyth, J.W.; Will, J.; Roberts, P.; Grek, C.L.; Ghatnekar, G.S.; Sheng, Z.; Gourdie, R.G.; Lamouille, S.; Foster, E.J. Development of PLGA nanoparticles for sustained release of a connexin43 mimetic peptide to target glioblastoma cells. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2020, 108, 110191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neri, S.; Mariani, E.; Meneghetti, A.; Cattini, L.; Facchini, A. Calcein-acetyoxymethyl cytotoxicity assay: Standardization of a method allowing additional analyses on recovered effector cells and supernatants. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 2001, 8, 1131–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ueda, G.; Tamura, Y.; Hirai, I.; Kamiguchi, K.; Ichimiya, S.; Torigoe, T.; Hiratsuka, H.; Sunakawa, H.; Sato, N. Tumor-derived heat shock protein 70-pulsed dendritic cells elicit tumor-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) and tumor immunity. Cancer Sci. 2004, 95, 248–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, F.E.; Chernobrovkin, A.; Pereda, C.; García-Salum, T.; Tittarelli, A.; López, M.N.; Salazar-Onfray, F.; Zubarev, R.A. Proteomic Identification of Heat Shock-Induced Danger Signals in a Melanoma Cell Lysate Used in Dendritic Cell-Based Cancer Immunotherapy. J. Immunol. Res. 2018, 2018, 3982942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanlon, D.J.; Saluja, S.S.; Sharp, F.; Hong, E.; Khalil, D.; Tigelaar, R.; Fahmy, T.M.; Edelson, R.L.; Robinson, E. Targeting human dendritic cells via DEC-205 using PLGA nanoparticles leads to enhanced cross-presentation of a melanoma-associated antigen. Int. J. Nanomed. 2014, 9, 5231–5246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Matheu, K.C.; Araya, B.C.; Diaz, F.T.; Hassan, N.; Salazar-Onfray, F.; Tittarelli, A. PLGA Nanoencapsulation Enhances Immunogenicity of Heat-Shocked Melanoma Tumor Cell Lysates. Cells 2025, 14, 1939. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14241939

Matheu KC, Araya BC, Diaz FT, Hassan N, Salazar-Onfray F, Tittarelli A. PLGA Nanoencapsulation Enhances Immunogenicity of Heat-Shocked Melanoma Tumor Cell Lysates. Cells. 2025; 14(24):1939. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14241939

Chicago/Turabian StyleMatheu, Kevin Calderón, Benjamín Cáceres Araya, Fiorella Tarkowski Diaz, Natalia Hassan, Flavio Salazar-Onfray, and Andrés Tittarelli. 2025. "PLGA Nanoencapsulation Enhances Immunogenicity of Heat-Shocked Melanoma Tumor Cell Lysates" Cells 14, no. 24: 1939. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14241939

APA StyleMatheu, K. C., Araya, B. C., Diaz, F. T., Hassan, N., Salazar-Onfray, F., & Tittarelli, A. (2025). PLGA Nanoencapsulation Enhances Immunogenicity of Heat-Shocked Melanoma Tumor Cell Lysates. Cells, 14(24), 1939. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14241939