Shaping the Immune Response: Cathepsins in Virus-Dendritic Cell Interactions

Abstract

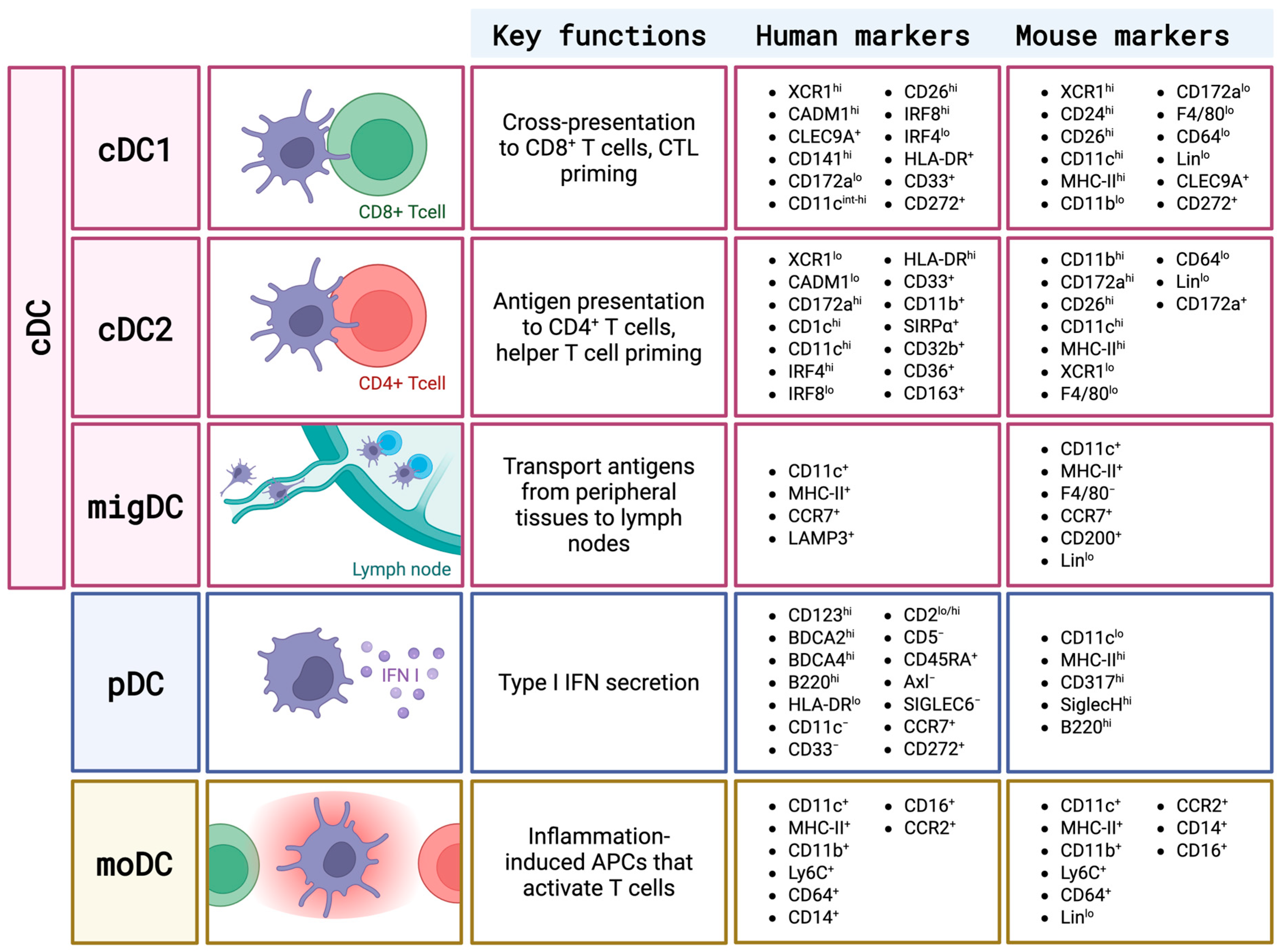

1. Overview of DC Subsets and Cathepsin Biology

2. Role of Cathepsins in the Function of DCs During Viral Infections

2.1. Cathepsins in Innate Immune Functions of DCs

2.1.1. Virus Sensing

2.1.2. Inflammatory Cytokine Production

2.1.3. Adhesion and Migration

2.2. Cathepsins and Adaptive Immune Functions of DCs

2.2.1. DC Maturation

2.2.2. Antigen Processing and Presentation

2.2.3. Activation and Polarization of the Th Immune Response

3. Cathepsins as Targets of Virus Modulation in DCs

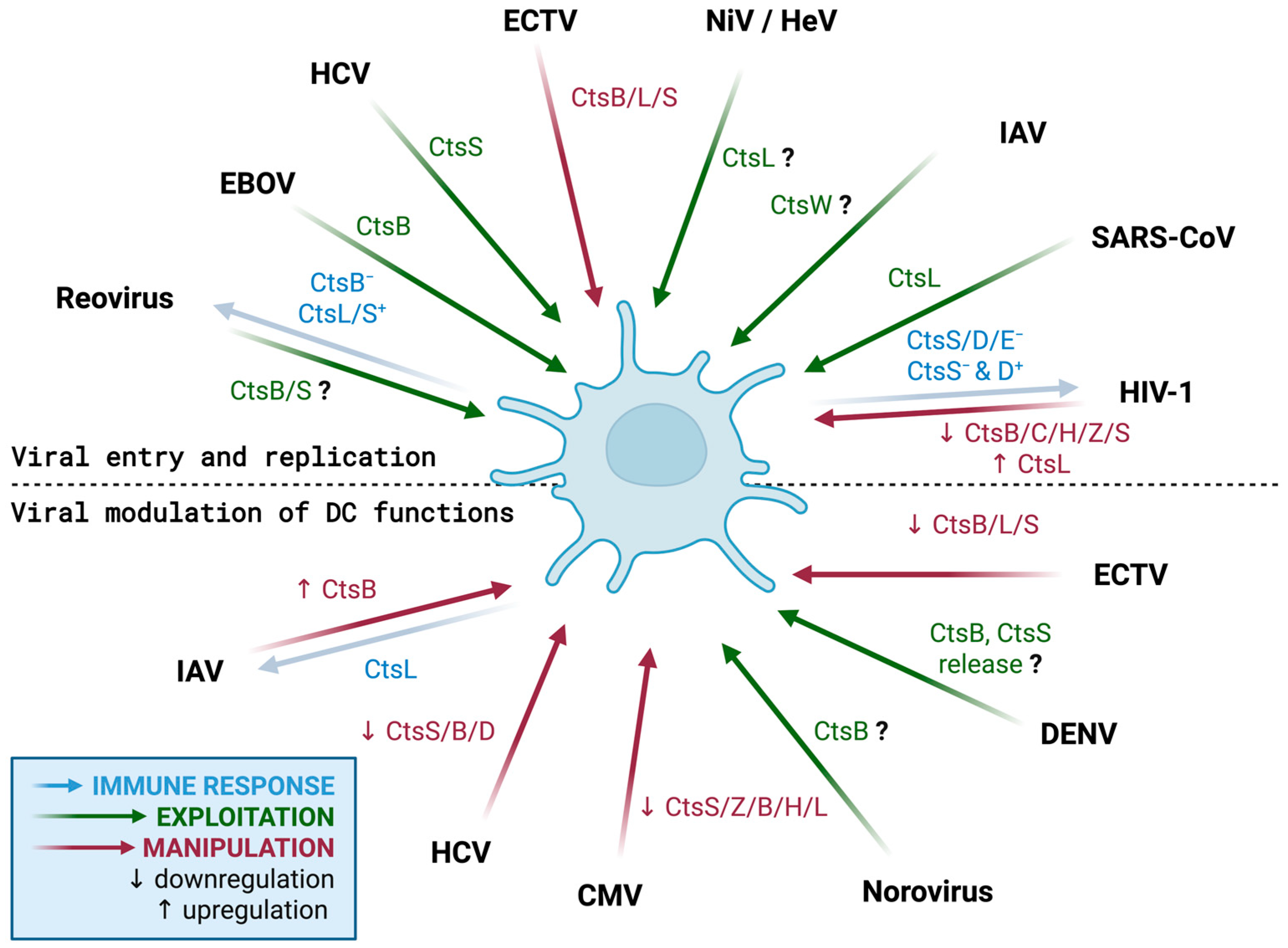

3.1. Cathepsins in the Viral Replication Cycle in DCs

3.1.1. Cathepsins in Viral Entry into DCs

3.1.2. Cathepsins in Viral Replication, Release, and Dissemination

3.2. Cathepsins as a Target for Viral Modulation of DC Functions

3.2.1. Cathepsins and Viral Modulation of Innate Immune Properties of DCs

3.2.2. Cathepsins and Viral Modulation of Adaptive Immune Properties of DCs

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACE2 | angiotensin-converting enzyme |

| AEP | asparaginyl endopeptidase |

| APC | antigen-presenting cell |

| BMDC | bone marrow-derived dendritic cell |

| CD-MPR | cation-dependent mannose-6-phosphate receptor |

| cGAS | cyclic GMP-AMP synthetase |

| CLIP | class II-associated invariant chain peptide |

| CMV | cytomegalovirus |

| CTL | cytotoxic T lymphocyte |

| DC | dendritic cell |

| EBOV | Ebola virus |

| ECTV | ectromelia virus |

| FLT3 | tyrosine kinase 3 ligand receptor |

| HCMV | human cytomegalovirus |

| HCV | hepatitis C virus |

| HeV | Hendra virus |

| HIV-1 | human immunodeficiency virus 1 |

| IAV | influenza A virus |

| IFN | interferon |

| Ii | invariant chain |

| IL | interleukin |

| IRF | interferon regulatory factor |

| MAVS | mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein |

| MHC | major histocompatibility complex class |

| moDCs | monocyte-derived DCs |

| MyD88 | myeloid differentiation primary response 88 |

| NiV | Nipah virus |

| NLR | nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain (NOD)-like receptors |

| NPC1 | Niemann-Pick type C1 protein |

| pDC | plasmacytoid dendritic cell |

| PI | protease inhibitor |

| PPARγ | peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ |

| PRR | pattern recognition receptor |

| rER | rough endoplasmic reticulum |

| RIG-I | retinoic acid-inducible gene-I |

| RLR | RIG-I-like receptor |

| SARS-CoV | severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus |

| STING | stimulator of interferon genes |

| Tfh | T follicular helper cell |

| TGN | trans-Golgi network |

| TIR | Toll/IL 1 receptor |

| TLR | Toll-like receptor |

| TRIF | TIR-domain-containing adapter-inducing interferon-β |

| VLP | viral-like particle |

| vRNP | viral ribonucleoprotein |

References

- Pishesha, N.; Harmand, T.J.; Ploegh, H.L. A guide to antigen processing and presentation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2022, 22, 751–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caro, A.A.; Deschoemaeker, S.; Allonsius, L.; Coosemans, A.; Laoui, D. Dendritic cell vaccines: A promising approach in the fight against ovarian cancer. Cancers 2022, 14, 4037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.Y.; Zhang, F.; Goedegebuure, S.P.; Gillanders, W.E. Dendritic cell subsets and implications for cancer immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1393451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randolph, G.J.; Angeli, V.; Swartz, M.A. Dendritic-cell trafficking to lymph nodes through lymphatic vessels. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2005, 5, 617–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durai, V.; Murphy, K.M. Functions of murine dendritic cells. Immunity 2016, 45, 719–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, L.; Lu, H.; Qiao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Hou, L.; Yu, X.; Cheng, H.; Chen, J.; Zheng, Q.; Hou, J.; et al. Conventional dendritic cells 2, the targeted antigen-presenting-cell, induces enhanced type 1 immune responses in mice immunized with CVC1302 in oil formulation. Immunol. Lett. 2024, 267, 106856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sancho, D.; Joffre, O.P.; Keller, A.M.; Rogers, N.C.; Martínez, D.; Hernanz-Falcón, P.; Rosewell, I.; Sousa, C.R.E. Identification of a dendritic cell receptor that couples sensing of necrosis to immunity. Nature 2009, 458, 899–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musumeci, A.; Lutz, K.; Winheim, E.; Krug, A.B. What makes a pDC: Recent advances in understanding plasmacytoid DC development and heterogeneity. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadati, T.; Houben, T.; Bitorina, A.; Shiri-Sverdlov, R. The ins and outs of cathepsins: Physiological function and role in disease management. Cells 2020, 9, 1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hook, G.; Jacobsen, J.S.; Grabstein, K.; Kindy, M.; Hook, V. Cathepsin B is a new drug target for traumatic brain injury therapeutics: Evidence for E64d as a promising lead drug candidate. Front. Neurol. 2015, 6, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burster, T.; Macmillan, H.; Hou, T.; Boehm, B.O.; Mellins, E.D. Cathepsin G: Roles in antigen presentation and beyond. Mol. Immunol. 2010, 47, 658–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benes, P.; Vetvicka, V.; Fusek, M. Cathepsin D—Many functions of one aspartic protease. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2008, 68, 12–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szulc-Dąbrowska, L.; Bossowska-Nowicka, M.; Struzik, J.; Toka, F.N. Cathepsins in bacteria–macrophage interaction: Defenders or victims of circumstance? Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 601072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brix, K. Host cell proteases: Cathepsins. In Activation of Viruses by Host Proteases; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 249–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turk, V.; Stoka, V.; Vasiljeva, O.; Renko, M.; Sun, T.; Turk, B.; Turk, D. Cysteine cathepsins: From structure, function and regulation to new frontiers. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Proteins Proteom. 2012, 1824, 68–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahiddine, K.; Hassel, C.; Murat, C.; Girard, M.; Guerder, S. Tissue-specific factors differentially regulate the expression of antigen-processing enzymes during dendritic cell ontogeny. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trombetta, E.S.; Ebersold, M.; Garrett, W.; Pypaert, M.; Mellman, I. Activation of lysosomal function during dendritic cell maturation. Science 2003, 299, 1400–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burster, T.; Beck, A.; Tolosa, E.; Schnorrer, P.; Weissert, R.; Reich, M.; Kraus, M.; Kalbacher, H.; Häring, H.U.; Weber, E.; et al. Differential processing of autoantigens in lysosomes from human monocyte-derived and peripheral blood dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 2005, 175, 5940–5949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Martínez, E.; Planès, R.; Anselmi, G.; Reynolds, M.; Menezes, S.; Adiko, A.C.; Saveanu, L.; Guermonprez, P. Cross-presentation of cell-associated antigens by MHC class I in dendritic cell subsets. Front. Immunol. 2015, 6, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohn, L.; Chatterjee, B.; Esselborn, F.; Smed-Sörensen, A.; Nakamura, N.; Chalouni, C.; Lee, B.C.; Vandlen, R.; Keler, T.; Lauer, P.; et al. Antigen delivery to early endosomes eliminates the superiority of human blood BDCA3+ dendritic cells at cross presentation. J. Exp. Med. 2013, 210, 1049–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, B.; Anderson, B.M.; Mintern, J.D.; Edgington-Mitchell, L.E. TLR9-dependent dendritic cell maturation promotes IL-6-mediated upregulation of cathepsin X. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2024, 102, 787–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wilson, K.R.; Firth, A.M.; Macri, C.; Schriek, P.; Blum, A.B.; Villar, J.; Wormald, S.; Shambrook, M.; Xu, B.; et al. Ubiquitin-like protein 3 (UBL3) is required for MARCH ubiquitination of major histocompatibility complex class II and CD86. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 29524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zavašnik-Bergant, T.; Repnik, U.; Schweiger, A.; Romih, R.; Jeras, M.; Turk, V.; Kos, J. Differentiation- and maturation-dependent content, localization, and secretion of cystatin C in human dendritic cells. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2005, 78, 122–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monaco, G.; Lee, B.; Xu, W.; Mustafah, S.; Hwang, Y.Y.; Carré, C.; Burdin, N.; Visan, L.; Ceccarelli, M.; Poidinger, M.; et al. RNA-seq signatures normalized by mRNA abundance allow absolute deconvolution of human immune cell types. Cell Rep. 2019, 26, 1627–1640.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudziak, D.; Kamphorst, A.O.; Heidkamp, G.F.; Buchholz, V.R.; Trumpfheller, C.; Yamazaki, S.; Cheong, C.; Liu, K.; Lee, H.W.; Park, C.G.; et al. Differential antigen processing by dendritic cell subsets in vivo. Science 2007, 315, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chain, B.M.; Free, P.; Medd, P.; Swetman, C.; Tabor, A.B.; Terrazzini, N. The expression and function of cathepsin E in dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 2005, 174, 1791–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanem, M.H.; Shih, A.J.; Khalili, H.; Werth, E.G.; Chakrabarty, J.K.; Brown, L.M.; Simpfendorfer, K.R.; Gregersen, P.K. Proteomic and single-cell transcriptomic dissection of human plasmacytoid dendritic cell response to influenza virus. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 814627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obermajer, N.; Švajger, U.; Bogyo, M.; Jeras, M.; Kos, J. Maturation of dendritic cells depends on proteolytic cleavage by cathepsin X. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2008, 84, 1306–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmer, A.; Bouley, J.; Le Mignon, M.; Pliquet, E.; Horiot, S.; Turfkruyer, M.; Baron-Bodo, V.; Horak, F.; Nony, E.; Louise, A.; et al. A regulatory dendritic cell signature correlates with the clinical efficacy of allergen-specific sublingual immunotherapy. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2012, 129, 1020–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich, M.; Spindler, K.D.; Burret, M.; Kalbacher, H.; Boehm, B.O.; Burster, T. Cathepsin A is expressed in primary human antigen-presenting cells. Immunol. Lett. 2010, 128, 143–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakken, B.; Varga, T.; Szatmari, I.; Szeles, L.; Gyongyosi, A.; Illarionov, P.A.; Dezso, B.; Gogolak, P.; Rajnavolgyi, E.; Nagy, L. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ-regulated cathepsin D is required for lipid antigen presentation by dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 2011, 187, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saito, Y.; Komori, S.; Kotani, T.; Murata, Y.; Matozaki, T. The role of type-2 conventional dendritic cells in the regulation of tumor immunity. Cancers 2022, 14, 1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewald, S.E.; Engel, A.; Lee, J.; Wang, M.; Bogyo, M.; Barton, G.M. Nucleic acid recognition by Toll-like receptors is coupled to stepwise processing by cathepsins and asparagine endopeptidase. J. Exp. Med. 2011, 208, 643–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Cattaneo, A.; Gobert, F.X.; Müller, M.; Toscano, F.; Flores, M.; Lescure, A.; del Nery, E.; Benaroch, P. Cleavage of Toll-like receptor 3 by cathepsins B and H is essential for signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 9053–9058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mielcarska, M.B.; Bossowska-Nowicka, M.; Toka, F.N. Functional failure of TLR3 and its signaling components contribute to herpes simplex encephalitis. J. Neuroimmunol. 2018, 316, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campden, R.I.; Zhang, Y. The role of lysosomal cysteine cathepsins in NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2019, 670, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, S.M.; Ma, X.; Abdullah, S.W.; Zheng, H. Activation and inhibition of the NLRP3 inflammasome by RNA viruses. J. Inflamm. Res. 2021, 14, 1145–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, I.C.; Scull, M.A.; Moore, C.B.; Holl, E.K.; McElvania-TeKippe, E.; Taxman, D.J.; Guthrie, E.H.; Pickles, R.J.; Ting, J.P.Y. The NLRP3 inflammasome mediates in vivo innate immunity to influenza A virus through recognition of viral RNA. Immunity 2009, 30, 556–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Jia, L.; Shen, J.; Wang, Y.; Fu, Z.; Su, S.A.; Cai, Z.; Wang, J.A.A.; Xiang, M. Cathepsin B aggravates coxsackievirus B3-induced myocarditis through activating the inflammasome and promoting pyroptosis. PLoS Pathog. 2018, 14, e1006872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Mazumdar, B.; Bose, S.K.; Meyer, K.; Di Bisceglie, A.M.; Hoft, D.F.; Ray, R. Hepatitis C virus-mediated inhibition of cathepsin S increases invariant-chain expression on hepatocyte surface. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 9919–9928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shortman, K.; Naik, S.H. Steady-state and inflammatory dendritic-cell development. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2007, 7, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honey, K.; Rudensky, A.Y. Lysosomal cysteine proteases regulate antigen presentation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2003, 3, 472–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, L.; Sigal, L.J.; Boes, M.; Rock, K.L. Important role of cathepsin S in generating peptides for TAP-independent MHC class I crosspresentation in vivo. Immunity 2004, 21, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, S.L.; Pasare, C.; Barton, G.M. Control of adaptive immunity by pattern recognition receptors. Immunity 2024, 57, 632–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Wagh, P.; Shinde, T.; Trimbake, D.; Tripathy, A.S. Exploring the role of pattern recognition receptors as immunostimulatory molecules. Immun. Inflamm. Dis. 2025, 13, e70150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roselli, E.; Araya, P.; Núñez, N.G.; Gatti, G.; Graziano, F.; Sedlik, C.; Benaroch, P.; Piaggio, E.; Maccioni, M. TLR3 activation of intratumoral CD103+ dendritic cells modifies the tumor infiltrate conferring anti-tumor immunity. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swiecki, M.; Wang, Y.; Riboldi, E.; Kim, A.H.J.; Dzutsev, A.; Gilfillan, S.; Vermi, W.; Ruedl, C.; Trinchieri, G.; Colonna, M. Cell depletion in mice that express diphtheria toxin receptor under the control of SiglecH encompasses more than plasmacytoid dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 2014, 192, 4409–4416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes-Santos, C.; de Azeredo, E.L. Innate immune response to dengue virus: Toll-like receptors and antiviral response. Viruses 2022, 14, 992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Lin, J.; Zhao, Y.; Ma, X.; Yi, H. Toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3) regulation mechanisms and roles in antiviral innate immune responses. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B 2021, 22, 609–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meås, H.Z.; Haug, M.; Beckwith, M.S.; Louet, C.; Ryan, L.; Hu, Z.; Landskron, J.; Nordbø, S.A.; Taskén, K.; Yin, H.; et al. Sensing of HIV-1 by TLR8 activates human T cells and reverses latency. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, T.J.; Igarashi, S.; Zhao, H.; Perez, O.A.; Pereira, M.R.; Zorn, E.; Shen, Y.; Goodrum, F.; Rahman, A.; Sims, P.A.; et al. Human plasmacytoid dendritic cells mount a distinct antiviral response to virus-infected cells. Sci. Immunol. 2021, 6, eabc7302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiola, S.; Gosselin, D.; Takada, K.; Gosselin, J. TLR9 contributes to the recognition of EBV by primary monocytes and plasmacytoid dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 2010, 185, 3620–3631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuelsson, C.; Hausmann, J.; Lauterbach, H.; Schmidt, M.; Akira, S.; Wagner, H.; Chaplin, P.; Suter, M.; O’Keeffe, M.; Hochrein, H. Survival of lethal poxvirus infection in mice depends on TLR9, and therapeutic vaccination provides protection. J. Clin. Investig. 2008, 118, 1776–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, J.; Sato, A.; Akira, S.; Medzhitov, R.; Iwasaki, A. Toll-like receptor 9-mediated recognition of herpes simplex virus-2 by plasmacytoid dendritic cells. J. Exp. Med. 2003, 198, 513–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Ohto, U.; Shibata, T.; Krayukhina, E.; Taoka, M.; Yamauchi, Y.; Tanji, H.; Isobe, T.; Uchiyama, S.; Miyake, K.; et al. Structural analysis reveals that Toll-like receptor 7 is a dual receptor for guanosine and single-stranded RNA. Immunity 2016, 45, 737–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishii, N.; Funami, K.; Tatematsu, M.; Seya, T.; Matsumoto, M. Endosomal localization of TLR8 confers distinctive proteolytic processing on human myeloid cells. J. Immunol. 2014, 193, 5118–5128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirahama-Noda, K.; Yamamoto, A.; Sugihara, K.; Hashimoto, N.; Asano, M.; Nishimura, M.; Hara-Nishimura, I. Biosynthetic processing of cathepsins and lysosomal degradation are abolished in asparaginyl endopeptidase-deficient mice. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 33194–33199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sepulveda, F.E.; Maschalidi, S.; Colisson, R.; Heslop, L.; Ghirelli, C.; Sakka, E.; Lennon-Duménil, A.M.; Amigorena, S.; Cabanie, L.; Manoury, B. Critical role for asparagine endopeptidase in endocytic Toll-like receptor signaling in dendritic cells. Immunity 2009, 31, 737–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asagiri, M.; Hirai, T.; Kunigami, T.; Kamano, S.; Gober, H.J.; Okamoto, K.; Nishikawa, K.; Latz, E.; Golenbock, D.T.; Aoki, K.; et al. Cathepsin K-dependent Toll-like receptor 9 signaling revealed in experimental arthritis. Science 2008, 319, 624–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, B.; Brinkmann, M.M.; Spooner, E.; Lee, C.C.; Kim, Y.M.; Ploegh, H.L. Proteolytic cleavage in an endolysosomal compartment is required for activation of Toll-like receptor 9. Nat. Immunol. 2008, 9, 1407–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, P.; Wang, W.; Cao, H.; Avogadri, F.; Dai, L.; Drexler, I.; Joyce, J.A.; Li, X.D.; Chen, Z.; Merghoub, T.; et al. Modified vaccinia virus Ankara triggers type I IFN production in murine conventional dendritic cells via a cGAS/STING-mediated cytosolic DNA-sensing pathway. PLoS Pathog. 2014, 10, e1003989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekita, M.; Wu, Z.; Ni, J.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; Yan, X.; Nakanishi, H.; Takahashi, I. Cathepsin S is involved in Th17 differentiation through the upregulation of IL-6 by activating PAR-2 after systemic exposure to lipopolysaccharide from Porphyromonas gingivalis. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, J.; Kawai, T.; Tsuchida, T.; Kozaki, T.; Tanaka, H.; Shin, K.S.; Kumar, H.; Akira, S. Poly IC triggers a cathepsin D- and IPS-1-dependent pathway to enhance cytokine production and mediate dendritic cell necroptosis. Immunity 2013, 38, 717–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kish, D.D.; Min, S.; Dvorina, N.; Baldwin, W.M.; Stohlman, S.A.; Fairchild, R.L. Neutrophil cathepsin G regulates dendritic cell production of IL-12 during development of CD4 T cell responses to antigens in the skin. J. Immunol. 2019, 202, 1045–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Leal, I.J.; Röger, B.; Schwarz, A.; Schirmeister, T.; Reinheckel, T.; Lutz, M.B.; Moll, H. Cathepsin B in antigen-presenting cells controls mediators of the Th1 immune response during Leishmania major infection. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2014, 8, e3194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasid, O.; Mériaux, V.; Khan, E.M.; Borde, C.; Ciulean, I.S.; Fitting, C.; Manoury, B.; Cavaillon, J.M.; Doyen, N. Cathepsin B-deficient mice resolve Leishmania major inflammation faster in a T cell-dependent manner. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2016, 10, e0004716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossowska-Nowicka, M.; Mielcarska, M.B.; Struzik, J.; Jackowska-Tracz, A.; Tracz, M.; Gregorczyk-Zboroch, K.P.; Gieryńska, M.; Toka, F.N.; Szulc-Dąbrowska, L. Deficiency of selected cathepsins does not affect the inhibitory action of ECTV on immune properties of dendritic cells. Immunol. Investig. 2020, 49, 232–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiebiger, E.; Meraner, P.; Weber, E.; Fang, I.F.; Stingl, G.; Ploegh, H.; Maurer, D. Cytokines regulate proteolysis in major histocompatibility complex class II-dependent antigen presentation by dendritic cells. J. Exp. Med. 2001, 193, 881–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Yu, X.; Ma, X.; Xie, L.; Xia, Z.; Liu, L.; Yu, X.; Wang, J.; Zhou, H.; Zhou, X.; et al. Deguelin attenuates non-small cell lung cancer cell metastasis through inhibiting the CtsZ/FAK signaling pathway. Cell. Signal. 2018, 50, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevriaux, A.; Pilot, T.; Derangère, V.; Simonin, H.; Martine, P.; Chalmin, F.; Ghiringhelli, F.; Rébé, C. Cathepsin B is required for NLRP3 inflammasome activation in macrophages through NLRP3 interaction. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, N.; Jeltema, D.; Duan, Y.; He, Y. The NLRP3 inflammasome: An overview of mechanisms of activation and regulation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waithman, J.; Mintern, J.D. Dendritic cells and influenza A virus infection. Virulence 2012, 3, 603–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campden, R.I.; Warren, A.L.; Greene, C.J.; Chiriboga, J.A.; Arnold, C.R.; Aggarwal, D.; McKenna, N.; Sandall, C.F.; MacDonald, J.A.; Yates, R.M. Extracellular cathepsin Z signals through the α5 integrin and augments NLRP3 inflammasome activation. J. Biol. Chem. 2022, 298, 101459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, E.R.O.; Campden, R.I.; Ewanchuk, B.W.; Tailor, P.; Balce, D.R.; McKenna, N.T.; Greene, C.J.; Warren, A.L.; Reinheckel, T.; Yates, R.M. A role for cathepsin Z in neuroinflammation provides mechanistic support for an epigenetic risk factor in multiple sclerosis. J. Neuroinflamm. 2017, 14, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengwasser, J.; Babes, L.; Cordes, S.; Mertlitz, S.; Riesner, K.; Shi, Y.; McGearey, A.; Kalupa, M.; Reinheckel, T.; Penack, O. Cathepsin E deficiency ameliorates graft-versus-host disease and modifies dendritic cell motility. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calle, Y.; Carragher, N.O.; Thrasher, A.J.; Jones, G.E. Inhibition of calpain stabilises podosomes and impairs dendritic cell motility. J. Cell Sci. 2006, 119, 2375–2385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; Kala, M.; Scott, B.G.; Goluszko, E.; Chapman, H.A.; Christadoss, P. Cathepsin S is required for murine autoimmune myasthenia gravis pathogenesis. J. Immunol. 2005, 174, 1729–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vidak, E.; Javoršek, U.; Vizovišek, M.; Turk, B. Cysteine cathepsins and their extracellular roles: Shaping the microenvironment. Cells 2019, 8, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Zhang, Z.; Deng, J.; Song, Y. Cathepsin S: Molecular mechanisms in inflammatory and immunological processes. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1600206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfisterer, K.; Shaw, L.E.; Symmank, D.; Weninger, W. The extracellular matrix in skin inflammation and infection. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 682414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardella, S.; Andrei, C.; Lotti, L.V.; Poggi, A.; Torrisi, M.R.; Zocchi, M.R.; Rubartelli, A. CD8+ T lymphocytes induce polarized exocytosis of secretory lysosomes by dendritic cells with release of interleukin-1β and cathepsin D. Blood 2001, 98, 2152–2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, G.; Jie, Y.; Haibo, L.; Chaoneng, W.; Dong, H.; Jianbing, Z.; Junjie, G.; Leilei, M.; Hongtao, S.; Yunzeng, Z.; et al. Dendritic cells derived exosomes migration to spleen and induction of inflammation are regulated by CCR7. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 42996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez-Castejon, G.; Theaker, J.; Pelegrin, P.; Clifton, A.D.; Braddock, M.; Surprenant, A. P2X7 receptor-mediated release of cathepsins from macrophages is a cytokine-independent mechanism potentially involved in joint diseases. J. Immunol. 2010, 185, 2611–2619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamon, Y.; Legowska, M.; Hervé, V.; Dallet-Choisy, S.; Marchand-Adam, S.; Vanderlynden, L.; Demonte, M.; Williams, R.; Scott, C.J.; Si-Tahar, M.; et al. Neutrophilic cathepsin C is maturated by a multistep proteolytic process and secreted by activated cells during inflammatory lung diseases. J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291, 8486–8499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jevnikar, Z.; Mirković, B.; Fonović, U.P.; Zidar, N.; Švajger, U.; Kos, J. Three-dimensional invasion of macrophages is mediated by cysteine cathepsins in protrusive podosomes. Eur. J. Immunol. 2012, 42, 3429–3441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, C.; Ortega-Cava, C.F.; Chen, G.; Fernandes, N.D.; Cavallo-Medved, D.; Sloane, B.F.; Band, V.; Band, H. Lysosomal cathepsin B participates in the podosome-mediated extracellular matrix degradation and invasion via secreted lysosomes in v-Src fibroblasts. Cancer Res. 2008, 68, 9147–9156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakehashi, H.; Nishioku, T.; Tsukuba, T.; Kadowaki, T.; Nakamura, S.; Yamamoto, K. Differential regulation of the nature and functions of dendritic cells and macrophages by cathepsin E. J. Immunol. 2007, 179, 5728–5737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, N.I.; Camps, M.G.; Garcia-Vallejo, J.J.; Bos, E.; Koster, A.J.; Verdoes, M.; van Kooyk, Y.; Ossendorp, F. Distinct antigen uptake receptors route to the same storage compartments for cross-presentation in dendritic cells. Immunology 2021, 164, 494–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossowska-Nowicka, M.; Mielcarska, M.B.; Romaniewicz, M.; Kaczmarek, M.M.; Gregorczyk-Zboroch, K.P.; Struzik, J.; Grodzik, M.; Gieryńska, M.M.; Toka, F.N.; Szulc-Dąbrowska, L. Ectromelia virus suppresses expression of cathepsins and cystatins in conventional dendritic cells to efficiently execute the replication process. BMC Microbiol. 2019, 19, 1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villadangos, J.A.; Cardoso, M.; Steptoe, R.J.; Van Berkel, D.; Pooley, J.; Carbone, F.R.; Shortman, K. MHC class II expression is regulated in dendritic cells independently of invariant chain degradation. Immunity 2001, 14, 739–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, K.; Sun, Y.; Zhong, S.; Luo, J.L. The multifaceted roles of cathepsins in immune and inflammatory responses: Implications for cancer therapy, autoimmune diseases, and infectious diseases. Biomark. Res. 2024, 12, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Wei, Z.; Cia, G.; Song, X.; Pucci, F.; Rooman, M.; Xue, F.; Hou, Q. MHCII-peptide presentation: An assessment of the state-of-the-art prediction methods. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1293706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reich, M.; Zou, F.; Sieńczyk, M.; Oleksyszyn, J.; Boehm, B.O.; Burster, T. Invariant chain processing is independent of cathepsin variation between primary human B cells/dendritic cells and B-lymphoblastoid cells. Cell. Immunol. 2011, 269, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manoury, B.; Mazzeo, D.; Li, D.N.; Billson, J.; Loak, K.; Benaroch, P.; Watts, C. Asparagine endopeptidase can initiate the removal of the MHC class II invariant chain chaperone. Immunity 2003, 18, 489–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maehr, R.; Hang, H.C.; Mintern, J.D.; Kim, Y.M.; Cuvillier, A.; Nishimura, M.; Yamada, K.; Shirahama-Noda, K.; Hara-Nishimura, I.; Ploegh, H.L. Asparagine endopeptidase is not essential for class II MHC antigen presentation but is required for processing of cathepsin L in mice. J. Immunol. 2005, 174, 7066–7074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ten Broeke, T.; Wubbolts, R.; Stoorvogel, W. MHC class II antigen presentation by dendritic cells regulated through endosomal sorting. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2013, 5, a016873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoeckle, C.; Quecke, P.; Rückrich, T.; Burster, T.; Reich, M.; Weber, E.; Kalbacher, H.; Driessen, C.; Melms, A.; Tolosa, E. Cathepsin S dominates autoantigen processing in human thymic dendritic cells. J. Autoimmun. 2012, 38, 332–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riese, R.J.; Wolf, P.R.; Brömme, D.; Natkin, L.R.; Villadangos, J.A.; Ploegh, H.L.; Chapman, H.A. Essential role for cathepsin S in MHC class II-associated invariant chain processing and peptide loading. Immunity 1996, 4, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, H.A.; Riese, R.J.; Shi, G.P. Emerging roles for cysteine proteases in human biology. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 1997, 59, 63–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiendl, H.; Lautwein, A.; Mitsdörffer, M.; Krause, S.; Erfurth, S.; Wienhold, W.; Morgalla, M.; Weber, E.; Overkleeft, H.S.; Lochmüller, H.; et al. Antigen processing and presentation in human muscle: Cathepsin S is critical for MHC class II expression and upregulated in inflammatory myopathies. J. Neuroimmunol. 2003, 138, 132–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, C.S.; deRoos, P.; Honey, K.; Beers, C.; Rudensky, A.Y. A role for cathepsin L and cathepsin S in peptide generation for MHC class II presentation. J. Immunol. 2002, 168, 2618–2625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, G.P.; Villadangos, J.A.; Dranoff, G.; Small, C.; Gu, L.; Haley, K.J.; Riese, R.; Ploegh, H.L.; Chapman, H.A. Cathepsin S required for normal MHC class II peptide loading and germinal center development. Immunity 1999, 10, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geetha, D.; Skaria, T. Cathepsin S: A key drug target and signalling hub in immune system diseases. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2025, 155, 114622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burster, T.; Giffon, T.; Dahl, M.E.; Björck, P.; Bogyo, M.; Weber, E.; Mahmood, K.; Lewis, D.B.; Mellins, E.D. Influenza A virus elevates active cathepsin B in primary murine DC. Int. Immunol. 2007, 19, 645–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz, F.M.; Chan, A.; Rock, K.L. Pathways of MHC I cross-presentation of exogenous antigens. Semin. Immunol. 2023, 66, 101729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stryhn, A.; Rötzschke, O.; Falk, K.; Faath, S.; Ottenhoff, T.H.; Jung, G.; Strominger, J.L.; Claesson, M.H. pH dependence of MHC class I-restricted peptide presentation. J. Immunol. 1996, 156, 4191–4197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lennon-Duménil, A.M.; Bakker, A.H.; Maehr, R.; Fiebiger, E.; Overkleeft, H.S.; Rosemblatt, M.; Ploegh, H.L.; Lagaudrière-Gesbert, C. Analysis of protease activity in live antigen-presenting cells shows regulation of the phagosomal proteolytic contents during dendritic cell activation. J. Exp. Med. 2002, 196, 529–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnowski, C.; Ciupka, G.; Tao, R.; Jin, L.; Busch, D.H.; Tao, S.; Drexler, I. Efficient induction of cytotoxic T cells by viral vector vaccination requires STING-dependent DC functions. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katunuma, N.; Matsunaga, Y.; Himeno, K.; Hayashi, Y. Insights into the roles of cathepsins in antigen processing and presentation revealed by specific inhibitors. Biol. Chem. 2003, 384, 883–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katunuma, N.; Matsunaga, Y.; Matsui, A.; Kakegawa, H.; Endo, K.; Inubushi, T.; Saibara, T.; Ohba, Y.; Kakiuchi, T. Novel physiological functions of cathepsins B and L on antigen processing and osteoclastic bone resorption. Adv. Enzyme Regul. 1998, 38, 235–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Maekawa, Y.; Yasutomo, K.; Ishikawa, H.; Nashed, B.F.; Dainichi, T.; Hisaeda, H.; Sakai, T.; Kasai, M.; Mizuochi, T.; et al. Pepstatin A-sensitive aspartic proteases in lysosome are involved in degradation of the invariant chain and antigen-processing in antigen presenting cells of mice infected with Leishmania major. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2000, 276, 693–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Maekawa, Y.; Hanba, J.; Dainichi, T.; Nashed, B.F.; Hisaeda, H.; Sakai, T.; Asao, T.; Himeno, K.; Good, R.A.; et al. Lysosomal cathepsin B plays an important role in antigen processing, while cathepsin D is involved in degradation of the invariant chain in ovalbumin-immunized mice. Immunology 2000, 100, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maekawa, Y.; Himeno, K.; Ishikawa, H.; Hisaeda, H.; Sakai, T.; Dainichi, T.; Asao, T.; Good, R.A.; Katunuma, N. Switch of CD4+ T cell differentiation from Th2 to Th1 by treatment with cathepsin B inhibitor in experimental leishmaniasis. J. Immunol. 1998, 161, 2120–2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Maekawa, Y.; Sakai, T.; Nakano, Y.; Ishii, K.; Hisaeda, H.; Dainichi, T.; Asao, T.; Katunuma, N.; Himeno, K. Treatment with cathepsin L inhibitor potentiates Th2-type immune response in Leishmania major-infected BALB/c mice. Int. Immunol. 2001, 13, 975–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Peng, H.; Lv, Y.; Li, C.; Cheng, Z.; He, S.; Wang, C.; Liu, J. Cathepsin S inhibition in dendritic cells prevents Th17 cell differentiation in perivascular adipose tissues following vascular injury in diabetic rats. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2023, 37, e23419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Rong, S.J.; Zhou, H.F.; Yang, C.; Sun, F.; Li, J.Y. Lysosomal control of dendritic cell function. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2023, 114, 518–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, T.; Pal, S.; Banerjee, I. Cathepsins in cellular entry of human pathogenic viruses. J. Virol. 2025, 99, e01642-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, E.M.; Doyle, J.D.; Wetzel, J.D.; McClung, R.P.; Katunuma, N.; Chappell, J.D.; Washington, M.K.; Dermody, T.S. Genetic and pharmacologic alteration of cathepsin expression influences reovirus pathogenesis. J. Virol. 2009, 83, 9630–9640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.; Sachdev, E.; Mita, A.C.; Mita, M.M. Clinical development of reovirus for cancer therapy: An oncolytic virus with immune-mediated antitumor activity. World J. Methodol. 2016, 6, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, M.B.; Stuart, J.D.; Rodríguez Stewart, R.; Berry, J.T.; Mainou, B.A.; Boehme, K.W. Current understanding of reovirus oncolysis mechanisms. Oncolytic Virother. 2018, 7, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilett, E.J.; Bárcena, M.; Errington-Mais, F.; Griffin, S.; Harrington, K.J.; Pandha, H.S.; Coffey, M.; Selby, P.J.; Limpens, R.W.A.L.; Mommaas, M.; et al. Internalization of oncolytic reovirus by human dendritic cell carriers protects the virus from neutralization. Clin. Cancer Res. 2011, 17, 2767–2776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamed, A.; Johnston, R.N.; Shmulevitz, M. Potential for improving potency and specificity of reovirus oncolysis with next-generation reovirus variants. Viruses 2015, 7, 6251–6278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrlich, M.; Boll, W.; Van Oijen, A.; Hariharan, R.; Chandran, K.; Nibert, M.L.; Kirchhausen, T. Endocytosis by random initiation and stabilization of clathrin-coated pits. Cell 2004, 118, 591–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonilha, C.S.; Benson, R.A.; Scales, H.E.; Brewer, J.M.; Garside, P. Junctional adhesion molecule-A on dendritic cells regulates Th1 differentiation. Immunol. Lett. 2021, 235, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebert, D.H.; Deussing, J.; Peters, C.; Dermody, T.S. Cathepsin L and cathepsin B mediate reovirus disassembly in murine fibroblast cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 24609–24617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golden, J.W.; Bahe, J.A.; Lucas, W.T.; Nibert, M.L.; Schiff, L.A. Cathepsin S supports acid-independent infection by some reoviruses. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 8547–8557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüdtke, A.; Ruibal, P.; Wozniak, D.M.; Pallasch, E.; Wurr, S.; Bockholt, S.; Gómez-Medina, S.; Qiu, X.; Kobinger, G.P.; Rodríguez, E.; et al. Ebola virus infection kinetics in chimeric mice reveal a key role of T cells as barriers for virus dissemination. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 43776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olukitibi, T.A.; Ao, Z.; Mahmoudi, M.; Kobinger, G.A.; Yao, X. Dendritic cells/macrophages-targeting feature of Ebola glycoprotein and its potential as immunological facilitator for antiviral vaccine approach. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, S.; Martynova, E.; Rizvanov, A.; Khaiboullina, S.; Baranwal, M. Structural and functional aspects of Ebola virus proteins. Pathogens 2021, 10, 1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carette, J.E.; Raaben, M.; Wong, A.C.; Herbert, A.S.; Obernosterer, G.; Mulherkar, N.; Kuehne, A.I.; Kranzusch, P.J.; Griffin, A.M.; Ruthel, G.; et al. Ebola virus entry requires the cholesterol transporter Niemann-Pick C1. Nature 2011, 477, 340–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, O.; Johnson, J.; Manicassamy, B.; Rong, L.; Olinger, G.G.; Hensley, L.E.; Basler, C.F. Zaire Ebola virus entry into human dendritic cells is insensitive to cathepsin L inhibition. Cell. Microbiol. 2010, 12, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnirß, K.; Kühl, A.; Karsten, C.; Glowacka, I.; Bertram, S.; Kaup, F.; Hofmann, H.; Pöhlmann, S. Cathepsins B and L activate Ebola but not Marburg virus glycoproteins for efficient entry into cell lines and macrophages independent of TMPRSS2 expression. Virology 2012, 424, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misasi, J.; Chandran, K.; Yang, J.Y.; Considine, B.; Filone, C.M.; Côté, M.; Sullivan, N.; Fabozzi, G.; Hensley, L.; Cunningham, J. Filoviruses require endosomal cysteine proteases for entry but exhibit distinct protease preferences. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 3284–3292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Najjar, F.; Lampe, L.; Baker, M.L.; Wang, L.F.; Dutch, R.E. Analysis of cathepsin and furin proteolytic enzymes involved in viral fusion protein activation in cells of the bat reservoir host. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0115736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pager, C.T.; Craft, W.W.; Patch, J.; Dutch, R.E. A mature and fusogenic form of the Nipah virus fusion protein requires proteolytic processing by cathepsin L. Virology 2006, 346, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pager, C.T.; Dutch, R.E. Cathepsin L is involved in proteolytic processing of the Hendra virus fusion protein. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 12714–12720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiong, V.; Shu, M.H.; Wong, W.F.; Abubakar, S.; Chang, L.Y. Nipah virus infection of immature dendritic cells increases its transendothelial migration across human brain microvascular endothelial cells. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiyama, H.; Miller, C.; Patel, H.V.; Hatch, S.C.; Archer, J.; Ramirez, N.G.P.; Gummuluru, S. Virus particle release from glycosphingolipid-enriched microdomains is essential for dendritic cell-mediated capture and transfer of HIV-1 and Henipavirus. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 8813–8825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, T.; Iqbal, M. The influenza A virus replication cycle: A comprehensive review. Viruses 2024, 16, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edinger, T.O.; Pohl, M.O.; Yángüez, E.; Stertz, S. Cathepsin W is required for escape of influenza A virus from late endosomes. mBio 2015, 6, e00297-15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günther, S.C.; Martínez-Romero, C.; Sempere Borau, M.; Pham, C.T.N.; García-Sastre, A.; Stertz, S. Proteomic identification of potential target proteins of cathepsin W for its development as a drug target for influenza. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e00921-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anes, E.; Azevedo-Pereira, J.M.; Pires, D. Cathepsins and their endogenous inhibitors in host defense during Mycobacterium tuberculosis and HIV infection. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 726984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, P.; Usami, O.; Suzuki, Y.; Ling, H.; Shimizu, N.; Hoshino, H.; Zhuang, M.; Ashino, Y.; Gu, H.; Hattori, T. Characterization of a CD4-independent clinical HIV-1 that can efficiently infect human hepatocytes through chemokine (C-X-C motif) receptor 4. AIDS 2008, 22, 1749–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Messaoudi, K.; Thiry, L.F.; Liesnard, C.; Van Tieghem, N.; Bollen, A.; Moguilevsky, N. A human milk factor susceptible to cathepsin D inhibitors enhances human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infectivity and allows virus entry into a mammary epithelial cell line. J. Virol. 2000, 74, 1004–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Montfort, T.; Thomas, A.A.M.; Pollakis, G.; Paxton, W.A. Dendritic cells preferentially transfer CXCR4-using human immunodeficiency virus type 1 variants to CD4+ T lymphocytes in trans. J. Virol. 2008, 82, 7886–7896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshii, H.; Kamiyama, H.; Goto, K.; Oishi, K.; Katunuma, N.; Tanaka, Y.; Hayashi, H.; Matsuyama, T.; Sato, H.; Yamamoto, N.; et al. CD4-independent human immunodeficiency virus infection involves participation of endocytosis and cathepsin B. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e19352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, M.D.; Ha, S.D.; Haeryfar, M.; Barr, S.D.; Kim, S.O. Cathepsin B plays a key role in optimal production of the influenza A virus. J. Virol. Antivir. Res. 2018, 7, 1000178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harman, A.N.; Kraus, M.; Bye, C.R.; Byth, K.; Turville, S.G.; Tang, O.; Mercier, S.K.; Nasr, N.; Stern, J.L.; Slobedman, B.; et al. HIV-1–infected dendritic cells show two phases of gene expression changes, with lysosomal enzyme activity decreased during the second phase. Blood 2009, 114, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coberley, C.R.; Kohler, J.J.; Brown, J.N.; Oshier, J.T.; Baker, H.V.; Popp, M.P.; Sleasman, J.W.; Goodenow, M.M. Impact on genetic networks in human macrophages by a CCR5 strain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 11477–11486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, S.D.; Park, S.; Hattlmann, C.J.; Barr, S.D.; Kim, S.O. Inhibition or deficiency of cathepsin B leads to defects in HIV-1 Gag pseudoparticle release in macrophages and HEK293T cells. Antivir. Res. 2012, 93, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goutagny, N.; Fatmi, A.; De Ledinghen, V.; Penin, F.; Couzigou, P.; Inchauspé, G.; Bain, C. Evidence of viral replication in circulating dendritic cells during hepatitis C virus infection. J. Infect. Dis. 2003, 187, 1951–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, I.S.; Lekkerkerker, A.N.; Depla, E.; Bosman, F.; Musters, R.J.P.; Depraetere, S.; van Kooyk, Y.; Geijtenbeek, T.B.H. Hepatitis C virus targets DC-SIGN and L-SIGN to escape lysosomal degradation. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 8322–8332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanford, M.M.; McFadden, G.; Karupiah, G.; Chaudhri, G. Immunopathogenesis of poxvirus infections: Forecasting the impending storm. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2007, 85, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, B. Poxvirus DNA replication. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2013, 5, a010199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleeton, M.N.; Contractor, N.; Leon, F.; Wetzel, J.D.; Dermody, T.S.; Kelsall, B.L. Peyer’s patch dendritic cells process viral antigen from apoptotic epithelial cells in the intestine of reovirus-infected mice. J. Exp. Med. 2004, 200, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soto, J.A.; Gálvez, N.M.S.; Andrade, C.A.; Pacheco, G.A.; Bohmwald, K.; Berrios, R.V.; Bueno, S.M.; Kalergis, A.M. The role of dendritic cells during infections caused by highly prevalent viruses. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sartorius, R.; Trovato, M.; Manco, R.; D’Apice, L.; De Berardinis, P. Exploiting viral sensing mediated by Toll-like receptors to design innovative vaccines. NPJ Vaccines 2021, 6, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, C.; Garrec, C.; Tomasello, E.; Dalod, M. The role of plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) in immunity during viral infections and beyond. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2024, 21, 1008–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, G.; Décembre, E.; Brocard, J.; Montpellier, C.; Ferrié, M.; Allatif, O.; Mehnert, A.K.; Pons, J.; Galiana, D.; Dao Thi, V.L.; et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cell sensing of hepatitis E virus is shaped by both viral and host factors. Life Sci. Alliance 2025, 8, e202503256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.; Chiang, C.; Gack, M.U. Viral evasion of the interferon response at a glance. J. Cell Sci. 2023, 136, jcs260682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lester, S.N.; Li, K. Toll-like receptors in antiviral innate immunity. J. Mol. Biol. 2014, 426, 1246–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Town, T.; Alexopoulou, L.; Anderson, J.F.; Fikrig, E.; Flavell, R.A. Toll-like receptor 3 mediates West Nile virus entry into the brain causing lethal encephalitis. Nat. Med. 2004, 10, 1366–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constant, O.; Maarifi, G.; Barthelemy, J.; Martin, M.F.; Tinto, B.; Savini, G.; Van de Perre, P.; Nisole, S.; Simonin, Y.; Salinas, S. Differential effects of Usutu and West Nile viruses on neuroinflammation, immune cell recruitment and blood-brain barrier integrity. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2023, 12, 2156815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foronjy, R.F.; Taggart, C.C.; Dabo, A.J.; Weldon, S.; Cummins, N.; Geraghty, P. Type-I interferons induce lung protease responses following respiratory syncytial virus infection via RIG-I-like receptors. Mucosal Immunol. 2015, 8, 161–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conus, S.; Simon, H.U. Cathepsins and their involvement in immune responses. Swiss Med. Wkly. 2010, 140, w13042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scarcella, M.; D’Angelo, D.; Ciampa, M.; Tafuri, S.; Avallone, L.; Pavone, L.M.; De Pasquale, V. The key role of lysosomal protease cathepsins in viral infections. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins, S.T.; Silveira, G.F.; Alves, L.R.; Duarte dos Santos, C.N.; Bordignon, J. Dendritic cell apoptosis and the pathogenesis of dengue. Viruses 2012, 4, 2736–2753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morchang, A.; Panaampon, J.; Suttitheptumrong, A.; Yasamut, U.; Noisakran, S.; Yenchitsomanus, P.T.; Limjindaporn, T. Role of cathepsin B in dengue virus-mediated apoptosis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2013, 438, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furman, L.M.; Maaty, W.S.; Petersen, L.K.; Ettayebi, K.; Hardy, M.E.; Bothner, B. Cysteine protease activation and apoptosis in murine norovirus infection. Virol. J. 2009, 6, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wobus, C.E.; Karst, S.M.; Thackray, L.B.; Chang, K.O.; Sosnovtsev, S.V.; Belliot, G.; Krug, A.; Mackenzie, J.M.; Green, K.Y.; Virgin, H.W. Replication of norovirus in cell culture reveals a tropism for dendritic cells and macrophages. PLoS Biol. 2004, 2, e432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Liu, Y.; Cao, L.; Wang, D.; Guo, M.; Jiang, A.; Guo, D.; Hu, W.; Yang, J.; Tang, Z.; et al. Transcriptomic characteristics of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid and peripheral blood mononuclear cells in COVID-19 patients. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2020, 9, 761–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Fang, M.; Hu, Y.; Huang, B.; Li, N.; Chang, C.; Huang, R.; Xu, X.; Yang, Z.; Chen, Z.; et al. Hepatitis B virus X protein inhibits autophagic degradation by impairing lysosomal maturation. Autophagy 2014, 10, 416–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuliandari, P.; Matsui, C.; Deng, L.; Abe, T.; Mori, H.; Taguwa, S.; Ono, C.; Fukuhara, T.; Matsuura, Y.; Shoji, I. Hepatitis C virus NS5A protein promotes the lysosomal degradation of diacylglycerol O-acyltransferase 1 (DGAT1) via endosomal microautophagy. Autophagy Rep. 2022, 1, 264–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, M.; Sanchez-Martinez, A.; Longo, M.; Suomi, F.; Stenlund, H.; Johansson, A.I.; Ehsan, H.; Salo, V.T.; Montava-Garriga, L.; Naddafi, S.; et al. DGAT1 activity synchronises with mitophagy to protect cells from metabolic rewiring by iron depletion. EMBO J. 2022, 41, e109390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, K.; Ait-Goughoulte, M.; Truscott, S.M.; Meyer, K.; Blazevic, A.; Abate, G.; Ray, R.B.; Hoft, D.F.; Ray, R. Hepatitis C virus inhibits cell surface expression of HLA-DR, prevents dendritic cell maturation, and induces interleukin-10 production. J. Virol. 2008, 82, 3320–3328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storm van’s Gravesande, K.; Layne, M.D.; Ye, Q.; Le, L.; Baron, R.M.; Perrella, M.A.; Santambrogio, L.; Silverman, E.S.; Riese, R.J. IFN regulatory factor-1 regulates IFN-γ-dependent cathepsin S expression. J. Immunol. 2002, 168, 4488–4494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auffermann-Gretzinger, S.; Keeffe, E.B.; Levy, S. Impaired dendritic cell maturation in patients with chronic, but not resolved, hepatitis C virus infection. Blood 2001, 97, 3171–3176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granato, M.; Lacconi, V.; Peddis, M.; Di Renzo, L.; Valia, S.; Rivanera, D.; Antonelli, G.; Frati, L.; Faggioni, A.; Cirone, M. Hepatitis C virus present in the sera of infected patients interferes with the autophagic process of monocytes impairing their in-vitro differentiation into dendritic cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2014, 1843, 1348–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Gredmark-Russ, S.; Söderberg-Nauclér, C. Dendritic cell biology in human cytomegalovirus infection and the clinical consequences for host immunity and pathology. Virulence 2012, 3, 621–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, T.; Reich, M.; Jahn, G.; Tolosa, E.; Beck, A.; Kalbacher, H.; Overkleeft, H.; Schempp, S.; Driessen, C. Human cytomegalovirus infection interferes with major histocompatibility complex type II maturation and endocytic proteases in dendritic cells at multiple levels. J. Gen. Virol. 2008, 89, 2427–2436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.W.; Hertel, L.; Louie, R.K.; Burster, T.; Lacaille, V.; Pashine, A.; Abate, D.A.; Mocarski, E.S.; Mellins, E.D. Human cytomegalovirus alters localization of MHC class II and dendrite morphology in mature Langerhans cells. J. Immunol. 2006, 177, 3960–3971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandhu, P.K.; Buchkovich, N.J. Human cytomegalovirus decreases major histocompatibility complex class II by regulating class II transactivator transcript levels in a myeloid cell line. J. Virol. 2020, 94, e01901-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Z.; Li, X. Human cytomegalovirus: Pathogenesis, prevention, and treatment. Mol. Biomed. 2024, 5, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benvenuti, F.; Hugues, S.; Walmsley, M.; Ruf, S.; Fetler, L.; Popoff, M.; Tybulewicz, V.L.J.; Amigorena, S. Requirement of Rac1 and Rac2 expression by mature dendritic cells for T cell priming. Science 2004, 305, 1150–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Alwan, M.M.; Rowden, G.; Lee, T.D.G.; West, K.A. Fascin is involved in the antigen presentation activity of mature dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 2001, 166, 338–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kourjian, G.; Rucevic, M.; Berberich, M.J.; Dinter, J.; Wambua, D.; Boucau, J.; Le Gall, S. HIV protease inhibitor–induced cathepsin modulation alters antigen processing and cross-presentation. J. Immunol. 2016, 196, 3595–3607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, N.; Baig, M.S.; Rizvi, A.H.; Arzoo, A.; Sharma, M.; Shahadab, M.; Arya, A.; Das, A.K.; Batra, V.V.; Mohanty, K.K.; et al. Profiling HIV-1–host protein-protein interaction networks in patient-derived exosome proteins: Impact on pathophysiology and innate immune pathways. Virol. J. 2025, 22, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Z.; Chu, Y.; Wang, Y. HIV protease inhibitors: A review of molecular selectivity and toxicity. HIV AIDS (Auckl.) 2015, 7, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Greenland, J.R.; Gotts, J.E.; Matthay, M.A.; Caughey, G.H. Cathepsin L helps to defend mice from infection with influenza A. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0164501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cathepsin | cDC1 | cDC2 | migDC | pDC | moDC | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A (serine) | moderate to high | moderate to high | ND | moderate | moderate to high | [11,30] |

| B (cysteine) | moderate | moderate to high | ND | high | moderate to high | [18,19,20,24] |

| C (cysteine) | low to moderate | moderate | ND | high | moderate | [24,27,29] |

| D (aspartic) | moderate | moderate | ND | moderate to high | moderate | [11,24,31] |

| E (aspartic) | ND | ND | ND | low | low to moderate | [24,26] |

| F (cysteine) | ND | ND | ND | very low | ND | [24] |

| G (serine) | low | low | ND | low to moderate | low | [11,30] |

| H (cysteine) | low to moderate | moderate to high | ND | low | moderate | [23,25] |

| K (cysteine) | ND | ND | ND | low | ND | [24] |

| L (cysteine) | moderate | high | ND | high | high | [18,19,20] |

| O (cysteine) | ND | ND | ND | low | ND | [24] |

| S (cysteine) | moderate | high | low | moderate | very high | [18,19,20,24] |

| V (cysteine) | ND | ND | ND | moderate to high | ND | [24] |

| X(Z/P) (cysteine) | moderate to high | high | ND | low | high | [21,22,24,25,27,28] |

| W (cysteine) * | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Niedzielska, A.; Bossowska-Nowicka, M.; Biernacka, Z.; Gregorczyk-Zboroch, K.; Toka, F.N.; Szulc-Dąbrowska, L. Shaping the Immune Response: Cathepsins in Virus-Dendritic Cell Interactions. Cells 2025, 14, 1900. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14231900

Niedzielska A, Bossowska-Nowicka M, Biernacka Z, Gregorczyk-Zboroch K, Toka FN, Szulc-Dąbrowska L. Shaping the Immune Response: Cathepsins in Virus-Dendritic Cell Interactions. Cells. 2025; 14(23):1900. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14231900

Chicago/Turabian StyleNiedzielska, Adrianna, Magdalena Bossowska-Nowicka, Zuzanna Biernacka, Karolina Gregorczyk-Zboroch, Felix N. Toka, and Lidia Szulc-Dąbrowska. 2025. "Shaping the Immune Response: Cathepsins in Virus-Dendritic Cell Interactions" Cells 14, no. 23: 1900. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14231900

APA StyleNiedzielska, A., Bossowska-Nowicka, M., Biernacka, Z., Gregorczyk-Zboroch, K., Toka, F. N., & Szulc-Dąbrowska, L. (2025). Shaping the Immune Response: Cathepsins in Virus-Dendritic Cell Interactions. Cells, 14(23), 1900. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14231900