Conservative Management of Focal Chondral Lesions of the Knee and Ankle: Current Concepts

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Biology of Cartilage Injury and Repair

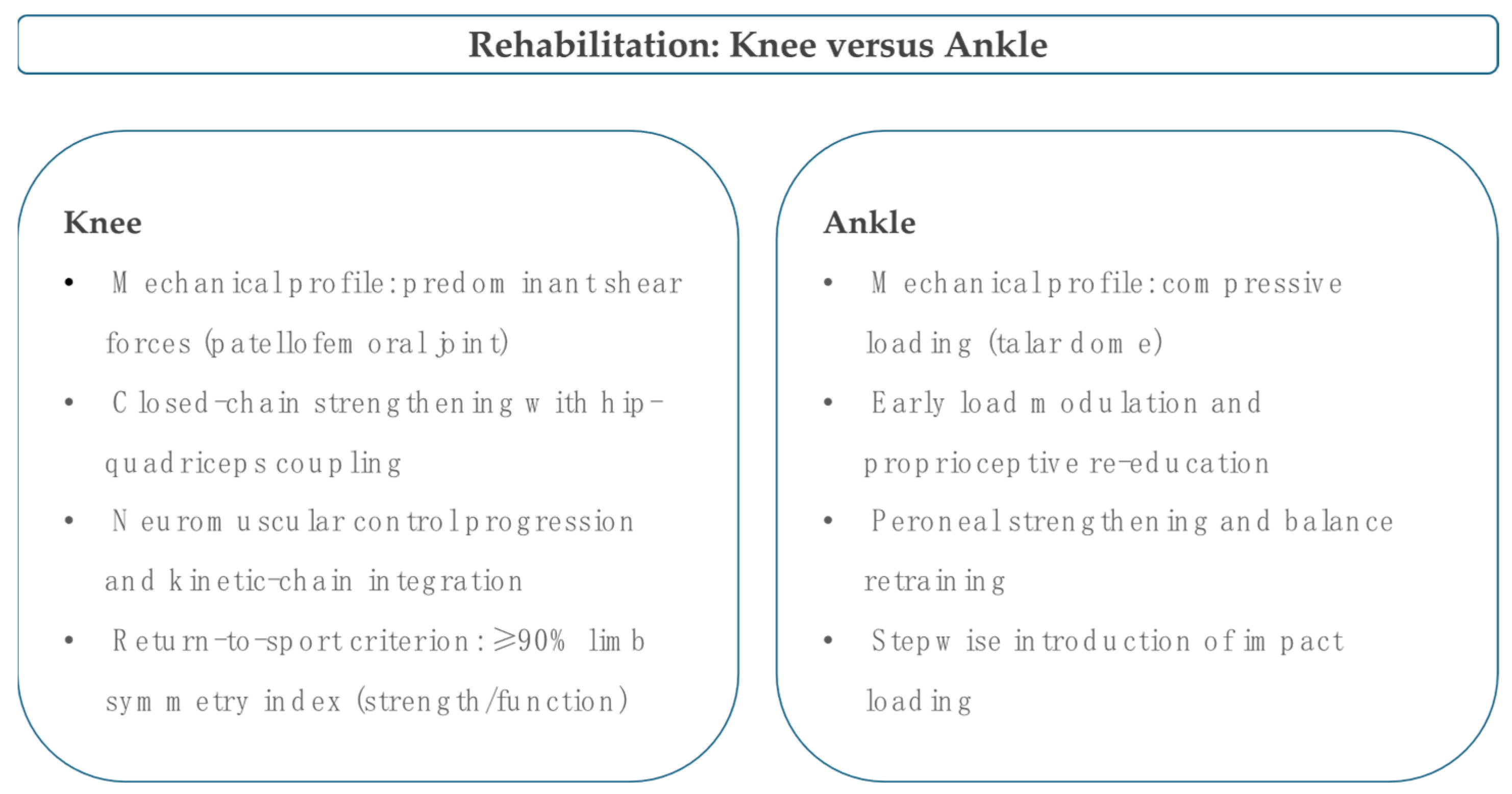

4. Rehabilitation and Load Management

5. Pharmacotherapy

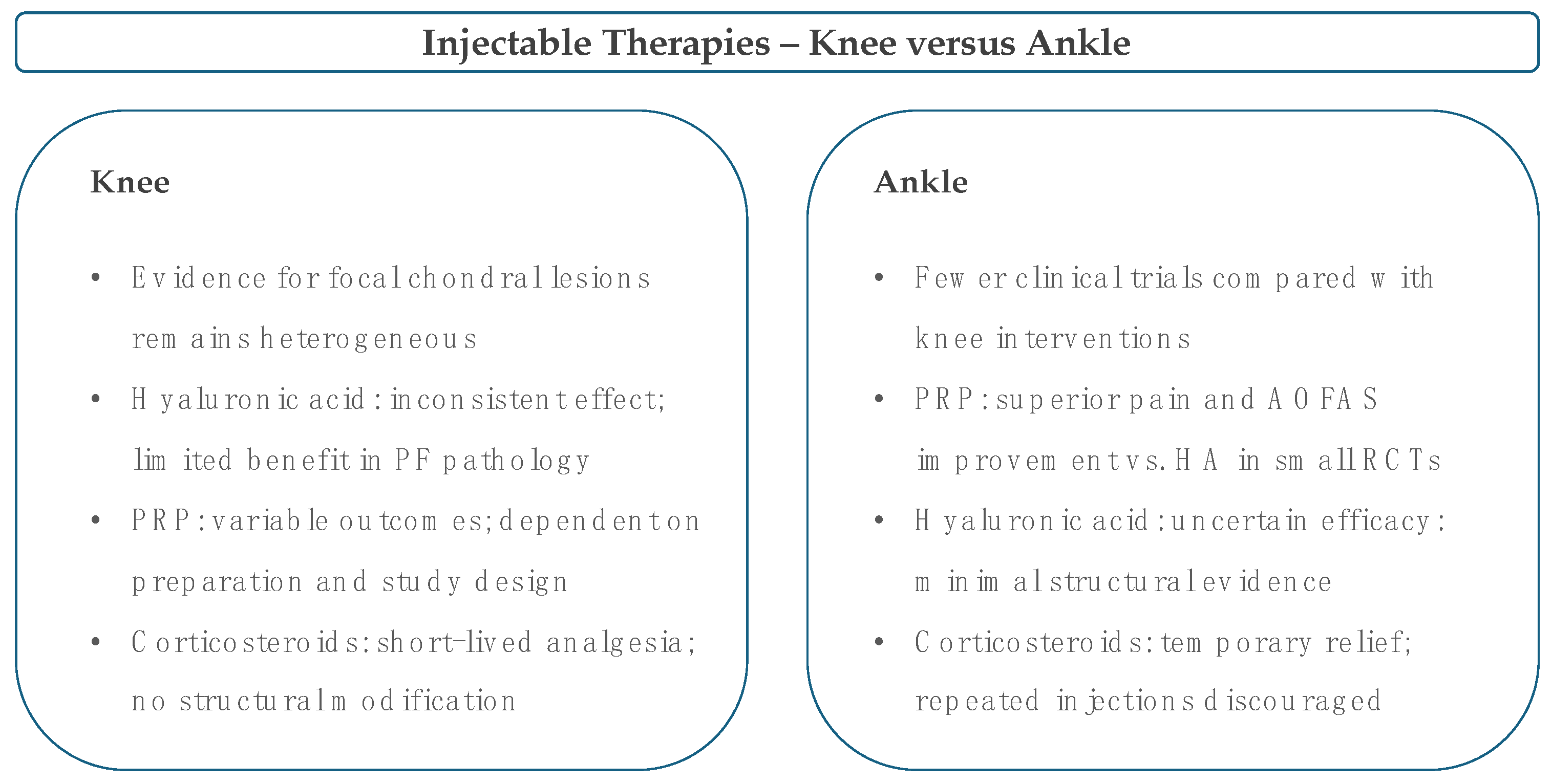

6. Intra-Articular Injectables

7. Nutraceuticals and Adjuncts

8. Knee Versus Ankle: Presentation, Pathophysiology and Biomechanics

9. Indications, Patient Selection and Monitoring

10. Evidence Gaps and Research Priorities

11. Future Prospects

12. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aroen, A.; Loken, S.; Heir, S.; Alvik, E.; Ekeland, A.; Granlund, O.G.; Engebretsen, L. Articular cartilage lesions in 993 consecutive knee arthroscopies. Am. J. Sports Med. 2004, 32, 211–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widuchowski, W.; Widuchowski, J.; Trzaska, T. Articular cartilage defects: Study of 25,124 knee arthroscopies. Knee 2007, 14, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curl, W.W.; Krome, J.; Gordon, E.S.; Rushing, J.; Smith, B.P.; Poehling, G.G. Cartilage injuries: A review of 31,516 knee arthroscopies. Arthroscopy 1997, 13, 456–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migliorini, F.; Simeone, F.; Bardazzi, T.; Memminger, M.K.; Pipino, G.; Vaishya, R.; Maffulli, N. Regenerative cartilage treatment for focal chondral defects in the knee: Focus on marrow-stimulating and cell-based scaffold approaches. Cells 2025, 14, 1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, E.; Epanomeritakis, I.E.; Lu, V.; Khan, W. Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cell implants for the treatment of focal chondral defects of the knee in animal models: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papadopoulos, G.; Griffin, S.; Rathi, H.; Gupta, A.; Sharma, B.; van Bavel, D. Cost-effectiveness analysis of arthroscopic injection of a bioadhesive hydrogel implant in conjunction with microfracture for the treatment of focal chondral defects of the knee—An australian perspective. J. Med. Econ. 2022, 25, 712–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cases, E.; Natera, L.; Anton, C.; Consigliere, P.; Guillen, J.; Cruz, E.; Garrucho, M. Focal inlay resurfacing for full-thickness chondral defects of the femoral medial condyle may delay the progression to varus deformity. Eur. J. Orthop. Surg. Traumatol. 2021, 31, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanaoka, C.; Fausett, C.; Jayabalan, P. Nonsurgical management of cartilage defects of the knee: Who, when, why, and how? J. Knee Surg. 2020, 33, 1078–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torrey, J.S.; Brown, C.R.; Hurley, E.T.; Danilkowicz, R.M.; Campbell, K.A.; Figueroa, D.; Guiloff, R.; Gursoy, S.; Hiemstra, L.A.; Matache, B.A.; et al. Nonoperative management of knee cartilage injuries—An international delphi consensus statement. J. Cartil. Jt. Preserv. 2024, 4, 100197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutaish, H.; Klopfenstein, A.; Adorisio, S.N.O.; Tscholl, P.M.; Fucentese, S. Current trends in the treatment of focal cartilage lesions: A comprehensive review. EFORT Open Rev. 2025, 10, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilat, R.; Haunschild, E.D.; Patel, S.; Yang, J.; DeBenedetti, A.; Yanke, A.B.; Della Valle, C.J.; Cole, B.J. Understanding the difference between symptoms of focal cartilage defects and osteoarthritis of the knee: A matched cohort analysis. Int. Orthop. 2021, 45, 1761–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Y.; Tian, Z.; Wang, M.; Chen, Z. Advances in the pathology and treatment of osteoarthritis. J. Adv. Res. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sophia Fox, A.J.; Bedi, A.; Rodeo, S.A. The basic science of articular cartilage: Structure, composition, and function. Sports Health 2009, 1, 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buckwalter, J.A.; Mankin, H.J. Articular cartilage: Tissue design and chondrocyte-matrix interactions. Instr. Course Lect. 1998, 47, 477–486. [Google Scholar]

- Karpiński, R.; Prus, A.; Baj, J.; Radej, S.; Prządka, M.; Krakowski, P.; Jonak, K. Articular cartilage: Structure, biomechanics, and the potential of conventional and advanced diagnostics. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 6896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurenkova, A.D.; Romanova, I.A.; Kibirskiy, P.D.; Timashev, P.; Medvedeva, E.V. Strategies to convert cells into hyaline cartilage: Magic spells for adult stem cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 11169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Migliorini, F.; Maffulli, N.; Eschweiler, J.; Götze, C.; Hildebrand, F.; Betsch, M. Prognostic factors for the management of chondral defects of the knee and ankle joint: A systematic review. Eur. J. Trauma Emerg. Surg. 2023, 49, 723–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migliorini, F.; Eschweiler, J.; Prinz, J.; Weber, C.D.; Hofmann, U.K.; Hildebrand, F.; Maffulli, N. Autologous chondrocyte implantation in the knee is effective in skeletally immature patients: A systematic review. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2023, 31, 2518–2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Shah, K.M.; Luo, J. Strategies for articular cartilage repair and regeneration. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 770655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, D.J.; Ortved, K.F.; Nixon, A.J.; Bonassar, L.J. Mechanical properties and structure-function relationships in articular cartilage repaired using igf-i gene-enhanced chondrocytes. J. Orthop. Res. 2016, 34, 149–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahr, H.; Matta, C.; Mobasheri, A. Physicochemical and biomechanical stimuli in cell-based articular cartilage repair. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 2015, 17, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, A.; Kelly, D.J. Role of oxygen as a regulator of stem cell fate during the spontaneous repair of osteochondral defects. J. Orthop. Res. 2016, 34, 1026–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buck, T.M.F.; Lauf, K.; Dahmen, J.; Altink, J.N.; Stufkens, S.A.S.; Kerkhoffs, G. Non-operative management for osteochondral lesions of the talus: A systematic review of treatment modalities, clinical- and radiological outcomes. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2023, 31, 3517–3527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattler, L.; Kan, A.; Hing, W.; Vertullo, C. The addition of structured lifestyle modifications to a traditional exercise program for the management of patients with knee osteoarthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials. Musculoskelet. Sci. Pract. 2023, 68, 102858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migliorini, F.; Driessen, A.; Quack, V.; Gatz, M.; Tingart, M.; Eschweiler, J. Surgical versus conservative treatment for first patellofemoral dislocations: A meta-analysis of clinical trials. Eur. J. Orthop. Surg. Traumatol. 2020, 30, 771–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thacher, R.R.; Pascual-Leone, N.; Rodeo, S.A. Treatment of knee chondral defects in athletes. Sports Med. Arthrosc. Rev. 2024, 32, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migliorini, F.; Driessen, A.; Quack, V.; Sippel, N.; Cooper, B.; Mansy, Y.E.; Tingart, M.; Eschweiler, J. Comparison between intra-articular infiltrations of placebo, steroids, hyaluronic and prp for knee osteoarthritis: A bayesian network meta-analysis. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 2021, 141, 1473–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clegg, T.E.; Caborn, D.; Mauffrey, C. Viscosupplementation with hyaluronic acid in the treatment for cartilage lesions: A review of current evidence and future directions. Eur. J. Orthop. Surg. Traumatol. 2013, 23, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brittberg, M. Treatment of knee cartilage lesions in 2024: From hyaluronic acid to regenerative medicine. J. Exp. Orthop. 2024, 11, e12016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angele, P.; Docheva, D.; Pattappa, G.; Zellner, J. Cell-based treatment options facilitate regeneration of cartilage, ligaments and meniscus in demanding conditions of the knee by a whole joint approach. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2022, 30, 1138–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, J.R.; Acuña, A.J.; Villareal, J.B.; Berreta, R.S.; Ayala, S.G.; del Baño-Barragán, L.; Allende, F.; Chahla, J. New horizons in cartilage repair: Update on treatment trends and outcomes. J. Cartil. Jt. Preserv. 2024, 4, 100179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utsunomiya, H.; Gao, X.; Cheng, H.; Deng, Z.; Nakama, G.; Mascarenhas, R.; Goldman, J.L.; Ravuri, S.K.; Arner, J.W.; Ruzbarsky, J.J.; et al. Intra-articular injection of bevacizumab enhances bone marrow stimulation-mediated cartilage repair in a rabbit osteochondral defect model. Am. J. Sports Med. 2021, 49, 1871–1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, Y.; Liu, Q.; Chen, P.; Zhao, S.; Jiang, W.; Wang, F.; Li, P.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, W.; Zhong, T.P.; et al. A novel prostaglandin e receptor 4 (ep4) small molecule antagonist induces articular cartilage regeneration. Cell Discov. 2022, 8, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basci, O.; Cimsit, M.; Zeren, S.; Saglican, Y.; Akgun, U.; Kocaoglu, B.; Basdemir, G.; Karahan, M. Effect of adjuvant hyperbaric oxygen on healing of cartilage lesions treated with microfracture: An experimental study in rats. Undersea Hyperb. Med. 2018, 45, 411–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavalle, S.; Scapaticci, R.; Masiello, E.; Salerno, V.M.; Cuocolo, R.; Cannella, R.; Botteghi, M.; Orro, A.; Saggini, R.; Zeppa, S.D.; et al. Beyond the surface: Nutritional interventions integrated with diagnostic imaging tools to target and preserve cartilage integrity: A narrative review. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makitsubo, M.; Adachi, N.; Nakasa, T.; Kato, T.; Shimizu, R.; Ochi, M. Differences in joint morphology between the knee and ankle affect the repair of osteochondral defects in a rabbit model. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2016, 11, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treppo, S.; Koepp, H.; Quan, E.C.; Cole, A.A.; Kuettner, K.E.; Grodzinsky, A.J. Comparison of biomechanical and biochemical properties of cartilage from human knee and ankle pairs. J. Orthop. Res. 2000, 18, 739–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howick, J.C.I.; Glasziou, P.; Greenhalgh, T.; Heneghan, C.; Liberati, A.; Moschetti, I.; Phillips, B.; Thornton, H.; Goddard, O.; Hodgkinson, M. The 2011 Oxford Cebm Levels of Evidence. Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine. 2011. Available online: https://www.cebm.net/index.aspx?o=5653 (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Krawetz, R.J.; Larijani, L.; Corpuz, J.M.; Ninkovic, N.; Das, N.; Olsen, A.; Mohtadi, N.; Rezansoff, A.; Dufour, A. Mesenchymal progenitor cells from non-inflamed versus inflamed synovium post-acl injury present with distinct phenotypes and cartilage regeneration capacity. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2023, 14, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellsandt, E.; Kallman, T.; Golightly, Y.; Podsiadlo, D.; Dudley, A.; Vas, S.; Michaud, K.; Tao, M.; Sajja, B.; Manzer, M. Knee joint unloading and daily physical activity associate with cartilage t2 relaxation times 1 month after acl injury. J. Orthop. Res. 2022, 40, 138–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rashidi, A.; Theruvath, A.J.; Huang, C.H.; Wu, W.; Mahmoud, E.E.; Raj, J.G.J.; Marycz, K.; Daldrup-Link, H.E. Vascular injury of immature epiphyses impair stem cell engraftment in cartilage defects. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 11696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, G.; Flaman, L.; Alaybeyoglu, B.; Struglics, A.; Frank, E.H.; Chubinskya, S.; Trippel, S.B.; Rosen, V.; Cirit, M.; Grodzinsky, A.J. Inflammatory cytokines and mechanical injury induce post-traumatic osteoarthritis-like changes in a human cartilage-bone-synovium microphysiological system. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2022, 24, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mow, V.C.; Guo, X.E. Mechano-electrochemical properties of articular cartilage: Their inhomogeneities and anisotropies. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2002, 4, 175–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsui, H.; Aoyama, T.; Furu, M.; Ito, K.; Jin, Y.; Maruyama, T.; Kanaji, T.; Fujimura, S.; Sugihara, H.; Nishiura, A.; et al. Prostaglandin E2 receptor type 2-selective agonist prevents the degeneration of articular cartilage in rabbit knees with traumatic instability. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2011, 13, R146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otsuka, S.; Aoyama, T.; Furu, M.; Ito, K.; Jin, Y.; Nasu, A.; Fukiage, K.; Kohno, Y.; Maruyama, T.; Kanaji, T.; et al. Pge2 signal via ep2 receptors evoked by a selective agonist enhances regeneration of injured articular cartilage. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2009, 17, 529–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, M.; Gao, Y.; Gu, Y.; Song, D.; Wang, J.; Ni, J.; He, G. Hmgb1 can activate cartilage progenitor cells in response to cartilage injury through the cxcl12/cxcr4 pathway. Endokrynol. Pol. 2023, 74, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosonen, J.P.; Eskelinen, A.S.A.; Orozco, G.A.; Nieminen, P.; Anderson, D.D.; Grodzinsky, A.J.; Korhonen, R.K.; Tanska, P. Injury-related cell death and proteoglycan loss in articular cartilage: Numerical model combining necrosis, reactive oxygen species, and inflammatory cytokines. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2023, 19, e1010337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranmuthu, C.K.I.; Ranmuthu, C.D.S.; Wijewardena, C.K.; Seah, M.K.T.; Khan, W.S. Evaluating the effect of hypoxia on human adult mesenchymal stromal cell chondrogenesis in vitro: A systematic review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 15210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.X.; Ma, Z.; Szojka, A.R.; Lan, X.; Kunze, M.; Mulet-Sierra, A.; Westover, L.; Adesida, A.B. Non-hypertrophic chondrogenesis of mesenchymal stem cells through mechano-hypoxia programing. J. Tissue Eng. 2023, 14, 20417314231172574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browe, D.C.; Coleman, C.M.; Barry, F.P.; Elliman, S.J. Hypoxia activates the pthrp -mef2c pathway to attenuate hypertrophy in mesenchymal stem cell derived cartilage. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 13274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Legendre, F.; Ollitrault, D.; Gomez-Leduc, T.; Bouyoucef, M.; Hervieu, M.; Gruchy, N.; Mallein-Gerin, F.; Leclercq, S.; Demoor, M.; Galera, P. Enhanced chondrogenesis of bone marrow-derived stem cells by using a combinatory cell therapy strategy with bmp-2/tgf-beta1, hypoxia, and col1a1/htra1 sirnas. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 3406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pattappa, G.; Johnstone, B.; Zellner, J.; Docheva, D.; Angele, P. The importance of physioxia in mesenchymal stem cell chondrogenesis and the mechanisms controlling its response. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chahla, J.; Williams, B.T.; Yanke, A.B.; Farr, J. The large focal isolated chondral lesion. J. Knee Surg. 2023, 36, 368–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, S.S.; Kim, C.W.; Jung, D.W. Management of focal chondral lesion in the knee joint. Knee Surg. Relat. Res. 2011, 23, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhtiary, A.H.; Fatemi, E. Open versus closed kinetic chain exercises for patellar chondromalacia. Br. J. Sports Med. 2008, 42, 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kettunen, J.A.; Harilainen, A.; Sandelin, J.; Schlenzka, D.; Hietaniemi, K.; Seitsalo, S.; Malmivaara, A.; Kujala, U.M. Knee arthroscopy and exercise versus exercise only for chronic patellofemoral pain syndrome: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Med. 2007, 5, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salem, H.S.; Chaudhry, Z.S.; Lucenti, L.; Tucker, B.S.; Freedman, K.B. The importance of staging arthroscopy for chondral defects of the knee. J. Knee Surg. 2022, 35, 145–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Q.M.; Wang, H.N.; Liu, X.H.; Zhou, W.Q.; Zhang, X.; Luo, X.B. Home-based exercise program and health education in patients with patellofemoral pain: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2023, 24, 896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warden, S.J.; Hinman, R.S.; Watson, M.A.; Avin, K.G., Jr.; Bialocerkowski, A.E.; Crossley, K.M. Patellar taping and bracing for the treatment of chronic knee pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008, 59, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honkonen, E.E.; Sillanpää, P.J.; Reito, A.; Mäenpää, H.; Mattila, V.M. A randomized controlled trial comparing a patella-stabilizing, motion-restricting knee brace versus a neoprene nonhinged knee brace after a first-time traumatic patellar dislocation. Am. J. Sports Med. 2022, 50, 1867–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Ambrosi, R.; Migliorini, F.; Cerciello, S.; Guerra, G.; Corona, K.; Mangiavini, L.; Ursino, N.; Vlaic, J.; Jelic, M. Management of the first episode of traumatic patellar dislocation: An international survey. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2023, 31, 2257–2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, G.W.; de Oliveira, D.F.; Ramos, A.P.S.; Sanada, L.S.; Migliorini, F.; Maffulli, N.; Okubo, R. Conservative management following patellar dislocation: A level i systematic review. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2023, 18, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, P.R.; Patil, D.S.; Sasun, A.R.; Phansopkar, P. The novelty of orthopedic rehabilitation after conservative management for patellar dislocation with partial tear of medial meniscus and early osteoarthritis in a 31-year-old female. Cureus 2023, 15, e46298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raju, A.; Jayaraman, K.; Nuhmani, S.; Sebastian, S.; Khan, M.; Alghadir, A.H. Effects of hip abductor with external rotator strengthening versus proprioceptive training on pain and functions in patients with patellofemoral pain syndrome: A randomized controlled trial. Medicine 2024, 103, e37102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wondrasch, B.; Aroen, A.; Rotterud, J.H.; Hoysveen, T.; Bolstad, K.; Risberg, M.A. The feasibility of a 3-month active rehabilitation program for patients with knee full-thickness articular cartilage lesions: The oslo cartilage active rehabilitation and education study. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2013, 43, 310–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.M.; Chen, J.; Ma, C.; Migliorini, F.; Oliva, F.; Maffulli, N. Limited medial osteochondral lesions of the talus associated with chronic ankle instability do not impact the results of endoscopic modified broström ligament repair. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2022, 17, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.; He, J.; Chen, L.; Chu, J.; Wu, H. Platelet rich plasma in the repair of articular cartilage injury: A narrative review. Cartilage 2022, 13, 19476035221118419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migliorini, F.; Oliva, F.; Eschweiler, J.; Torsiello, E.; Hildebrand, F.; Maffulli, N. Knee osteoarthritis, joint laxity and proms following conservative management versus surgical reconstruction for acl rupture: A meta-analysis. Br. Med. Bull. 2023, 145, 72–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plancher, K.D.; Agyapong, G.; Dows, A.; Wang, K.H.; Reyes, M.M.; Briggs, K.K.; Petterson, S.C. Management of articular cartilage defects in the knee: An evidence-based algorithm. JBJS J. Orthop. Physician Assist. 2024, 12, e24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artioli, E.; Mazzotti, A.; Gerardi, S.; Arceri, A.; Barile, F.; Manzetti, M.; Viroli, G.; Ruffilli, A.; Faldini, C. Retrograde drilling for ankle joint osteochondral lesions: A systematic review. J. Orthop. Traumatol. 2023, 24, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itha, R.; Vaishya, R.; Vaish, A.; Migliorini, F. Management of chondral and osteochondral lesions of the hip: A comprehensive review. Die Orthopädie 2024, 53, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozudogru, A.; Gelecek, N. Effects of closed and open kinetic chain exercises on pain, muscle strength, function, and quality of life in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Rev. Assoc. Médica Bras. 2023, 69, e20230164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mithoefer, K.; Hambly, K.; Logerstedt, D.; Ricci, M.; Silvers, H.; Della Villa, S. Current concepts for rehabilitation and return to sport after knee articular cartilage repair in the athlete. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2012, 42, 254–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chmielewski, T.L.; Myer, G.D.; Kauffman, D.; Tillman, S.M. Plyometric exercise in the rehabilitation of athletes: Physiological responses and clinical application. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2006, 36, 308–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, C.; Cicuttini, F.; Jones, G. Do nsaids affect longitudinal changes in knee cartilage volume and knee cartilage defects in older adults? Am. J. Med. 2009, 122, 836–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solaiman, R.H.; Dirnberger, J.; Kennedy, N.I.; DePhillipo, N.N.; Tagliero, A.J.; Malinowski, K.; Dimmen, S.; LaPrade, R.F. The effect of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use on soft tissue and bone healing in the knee: A systematic review. Ann. Jt. 2024, 9, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heintjes, E.; Berger, M.Y.; Bierma-Zeinstra, S.M.; Bernsen, R.M.; Verhaar, J.A.; Koes, B.W. Pharmacotherapy for patellofemoral pain syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2004, 2004, CD003470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCoy, J.M.; Wicks, J.R.; Audoly, L.P. The role of prostaglandin e2 receptors in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. J. Clin. Investig. 2002, 110, 651–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, N.E.; Schnitzer, T.J.; Birbara, C.A.; Mokhtarani, M.; Shelton, D.L.; Smith, M.D.; Brown, M.T. Tanezumab for the treatment of pain from osteoarthritis of the knee. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 1521–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevalier, X.; Eymard, F.; Richette, P. Biologic agents in osteoarthritis: Hopes and disappointments. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2013, 9, 400–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solanki, K.; Shanmugasundaram, S.; Shetty, N.; Kim, S.J. Articular cartilage repair & joint preservation: A review of the current status of biological approach. J. Clin. Orthop. Trauma 2021, 22, 101602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkely, G.; Chisari, E.; Rosso, C.L.; Lattermann, C. Do nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs have a deleterious effect on cartilage repair? A systematic review. Cartilage 2021, 13, 326S–341S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Bekerom, M.P.J.; Sjer, A.; Somford, M.P.; Bulstra, G.H.; Struijs, P.A.A.; Kerkhoffs, G. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (nsaids) for treating acute ankle sprains in adults: Benefits outweigh adverse events. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2015, 23, 2390–2399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, A.R.; Patel, J.M.; Zlotnick, H.M.; Carey, J.L.; Mauck, R.L. Emerging therapies for cartilage regeneration in currently excluded ‘red knee’ populations. NPJ Regen. Med. 2019, 4, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres-Torrillas, M.; Damia, E.; Del Romero, A.; Pelaez, P.; Miguel-Pastor, L.; Chicharro, D.; Carrillo, J.M.; Rubio, M.; Sopena, J.J. Intra-osseous plasma rich in growth factors enhances cartilage and subchondral bone regeneration in rabbits with acute full thickness chondral defects: Histological assessment. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1131666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAlindon, T.E.; LaValley, M.P.; Harvey, W.F.; Price, L.L.; Driban, J.B.; Zhang, M.; Ward, R.J. Effect of intra-articular triamcinolone vs. saline on knee cartilage volume and pain in patients with knee osteoarthritis: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2017, 317, 1967–1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuyucu, E.; Cabuk, H.; Guler, Y.; Cabuk, F.; Kilic, E.; Bulbul, M. Can intra-articular 1alpha, 25-dihydroxyvitamin d3 administration be therapeutical in joint cartilage damage? Acta Chir. Orthop. Traumatol. Cech. 2020, 87, 90–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuggle, N.R.; Cooper, C.; Oreffo, R.O.C.; Price, A.J.; Kaux, J.F.; Maheu, E.; Cutolo, M.; Honvo, G.; Conaghan, P.G.; Berenbaum, F.; et al. Alternative and complementary therapies in osteoarthritis and cartilage repair. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2020, 32, 547–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, J.M.; Kuenze, C.; Norte, G.; Bodkin, S.; Patrie, J.; Denny, C.; Hart, J.; Diduch, D.R. Prospective, randomized, double-blind evaluation of the efficacy of a single-dose hyaluronic acid for the treatment of patellofemoral chondromalacia. Orthop. J. Sports Med. 2019, 7, 2325967119854192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Migliorini, F.; Maffulli, N.; Schafer, L.; Kubach, J.; Betsch, M.; Pasurka, M. Less pain with intra-articular hyaluronic acid injections for knee osteoarthritis compared to placebo: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migliorini, F.; Schafer, L.; Pilone, M.; Bell, A.; Simeone, F.; Maffulli, N. Similar efficacy of intra-articular hyaluronic acid injections and other biologically active injections in patients with early stages knee osteoarthritis: A level i meta-analysis. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 2024, 145, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migliorini, F.; Maffulli, N.; Nijboer, C.H.; Pappalardo, G.; Pasurka, M.; Betsch, M.; Kubach, J. Comparison of different molecular weights of intra-articular hyaluronic acid injections for knee osteoarthritis: A level i bayesian network meta-analysis. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mei-Dan, O.; Carmont, M.R.; Laver, L.; Mann, G.; Maffulli, N.; Nyska, M. Platelet-rich plasma or hyaluronate in the management of osteochondral lesions of the talus. Am. J. Sports Med. 2012, 40, 534–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migliorini, F.; Maffulli, N.; Bell, A.; Hildebrand, F.; Weber, C.D.; Lichte, P. Autologous matrix-induced chondrogenesis (amic) for osteochondral defects of the talus: A systematic review. Life 2022, 12, 1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chahla, J.; Cinque, M.E.; Shon, J.M.; Liechti, D.J.; Matheny, L.M.; LaPrade, R.F.; Clanton, T.O. Bone marrow aspirate concentrate for the treatment of osteochondral lesions of the talus: A systematic review of outcomes. J. Exp. Orthop. 2016, 3, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jo, C.H.; Lee, Y.G.; Shin, W.H.; Kim, H.; Chai, J.W.; Jeong, E.C.; Kim, J.E.; Shim, H.; Shin, J.S.; Shin, I.S.; et al. Intra-articular injection of mesenchymal stem cells for the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: A proof-of-concept clinical trial. Stem Cells 2014, 32, 1254–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davila Castrodad, I.M.; Kraeutler, M.J.; Fasulo, S.M.; Festa, A.; McInerney, V.K.; Scillia, A.J. Improved outcomes with arthroscopic bone marrow aspirate concentrate and cartilage-derived matrix implantation versus chondroplasty for the treatment of focal chondral defects of the knee joint: A retrospective case series. Arthrosc. Sports Med. Rehabil. 2022, 4, e411–e416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt, M.; Uysal, O.; Kilic, E.; Emre, F.; Kaya, O. A new concept of mosaicplasty: Autologous osteoperiosteal cylinder graft covered with cellularized scaffold. Arthrosc. Tech. 2022, 11, e655–e660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobti, A.S.; Baryeh, K.W.; Woolf, R.; Chana, R. Autologous matrix-induced chondrogenesis and bone marrow aspirate concentrate compared with microfracture for arthroscopic treatment of femoroacetabular impingement and chondral lesions of the hip: Bridging the osteoarthritis gap and facilitating enhanced recovery. J. Hip Preserv. Surg. 2020, 7, 503–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migliorini, F.; Schenker, H.; Maffulli, N.; Eschweiler, J.; Lichte, P.; Hildebrand, F.; Weber, C.D. Autologous matrix induced chondrogenesis (amic) as revision procedure for failed amic in recurrent symptomatic osteochondral defects of the talus. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 16244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migliorini, F.; Berton, A.; Salvatore, G.; Candela, V.; Khan, W.; Longo, U.G.; Denaro, V. Autologous chondrocyte implantation and mesenchymal stem cells for the treatments of chondral defects of the knee- a systematic review. Curr. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2020, 15, 547–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Z.; Wu, Y.; Xie, L.; Xu, Z.; Chang, C. Nutrition supplementation combined with exercise versus exercise alone in treating knee osteoarthritis: A double-blinded, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Age Ageing 2025, 54, afaf010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdon, B.; Casse, F.; Gruchy, N.; Cambier, P.; Leclercq, S.; Oddoux, S.; Noel, A.; Lafont, J.E.; Contentin, R.; Galera, P. Marine collagen hydrolysates promote collagen synthesis, viability and proliferation while downregulating the synthesis of pro-catabolic markers in human articular chondrocytes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McAlindon, T.; LaValley, M.; Schneider, E.; Nuite, M.; Lee, J.Y.; Price, L.L.; Lo, G.; Dawson-Hughes, B. Effect of vitamin d supplementation on progression of knee pain and cartilage volume loss in patients with symptomatic osteoarthritis: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2013, 309, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clegg, D.O.; Reda, D.J.; Harris, C.L.; Klein, M.A.; O’Dell, J.R.; Hooper, M.M.; Bradley, J.D.; Bingham, C.O., 3rd; Weisman, M.H.; Jackson, C.G.; et al. Glucosamine, chondroitin sulfate, and the two in combination for painful knee osteoarthritis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006, 354, 795–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, K.L.; Sebastianelli, W.; Flechsenhar, K.R.; Aukermann, D.F.; Meza, F.; Millard, R.L.; Deitch, J.R.; Sherbondy, P.S.; Albert, A. 24-week study on the use of collagen hydrolysate as a dietary supplement in athletes with activity-related joint pain. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2008, 24, 1485–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zdzieblik, D.; Oesser, S.; Gollhofer, A.; König, D. Improvement of activity-related knee joint discomfort following supplementation of specific collagen peptides. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2017, 42, 588–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowley, D.C.; Lau, F.C.; Sharma, P.; Evans, M.; Guthrie, N.; Bagchi, M.; Bagchi, D.; Dey, D.K.; Raychaudhuri, S.P. Safety and efficacy of undenatured type ii collagen in the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: A clinical trial. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2009, 6, 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugo, J.P.; Saiyed, Z.M.; Lane, N.E. Efficacy and tolerability of an undenatured type ii collagen supplement in modulating knee osteoarthritis symptoms: A multicenter randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Nutr. J. 2016, 15, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rondanelli, M.; Faliva, M.A.; Barrile, G.C.; Cavioni, A.; Mansueto, F.; Mazzola, G.; Oberto, L.; Patelli, Z.; Pirola, M.; Tartara, A.; et al. Nutrition, physical activity, and dietary supplementation to prevent bone mineral density loss: A food pyramid. Nutrients 2021, 14, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cicero, A.F.G.; Girolimetto, N.; Bentivenga, C.; Grandi, E.; Fogacci, F.; Borghi, C. Short-term effect of a new oral sodium hyaluronate formulation on knee osteoarthritis: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Diseases 2020, 8, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagim, A.R.; Harty, P.S.; Erickson, J.L.; Tinsley, G.M.; Garner, D.; Galpin, A.J. Prevalence of adulteration in dietary supplements and recommendations for safe supplement practices in sport. Front. Sports Act. Living 2023, 5, 1239121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Coronado, J.M.; Martínez-Olvera, L.; Elizondo-Omaña, R.E.; Acosta-Olivo, C.A.; Vilchez-Cavazos, F.; Simental-Mendía, L.E.; Simental-Mendía, M. Effect of collagen supplementation on osteoarthritis symptoms: A meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Int. Orthop. 2019, 43, 531–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, S.; Sahanand, K.S. Managing chondral lesions: A literature review and evidence-based clinical guidelines. Indian J. Orthop. 2021, 55, 252–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baydar, M.; Gulbahar, S. Physical therapy and rehabilitation in chondral lesions. Acta Orthop. Traumatol. Turc. 2007, 41 (Suppl. 2), 54–61. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18180585 (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Logerstedt, D.S.; Scalzitti, D.A.; Bennell, K.L.; Hinman, R.S.; Silvers-Granelli, H.; Ebert, J.; Hambly, K.; Carey, J.L.; Snyder-Mackler, L.; Axe, M.J.; et al. Knee pain and mobility impairments: Meniscal and articular cartilage lesions revision 2018. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2018, 48, A1–A50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruns, J.; Habermann, C.; Werner, M. Osteochondral lesions of the talus: A review on talus osteochondral injuries, including osteochondritis dissecans. Cartilage 2021, 13, 1380S–1401S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, E.Y.; Tadros, A.S.; Amini, B.; Bell, A.M.; Bernard, S.A.; Fox, M.G.; Gorbachova, T.; Ha, A.S.; Lee, K.S.; Metter, D.F.; et al. Acr appropriateness criteria(®) chronic ankle pain. J. Am. Coll. Radiol. 2018, 15, S26–S38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Expert Panel on Musculoskeletal Imaging; Fox, M.G.; Chang, E.Y.; Amini, B.; Bernard, S.A.; Gorbachova, T.; Ha, A.S.; Iyer, R.S.; Lee, K.S.; Metter, D.F.; et al. Acr appropriateness criteria® chronic knee pain. J. Am. Coll. Radiol. 2018, 15, S302–S312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Wang, X. Advancements in the treatment of osteochondral lesions of the talus. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2024, 19, 827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domayer, S.E.; Welsch, G.H.; Dorotka, R.; Mamisch, T.C.; Marlovits, S.; Szomolanyi, P.; Trattnig, S. Mri monitoring of cartilage repair in the knee: A review. Semin. Musculoskelet. Radiol. 2008, 12, 302–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marlovits, S.; Singer, P.; Zeller, P.; Mandl, I.; Haller, J.; Trattnig, S. Magnetic resonance observation of cartilage repair tissue (mocart) for the evaluation of autologous chondrocyte transplantation: Determination of interobserver variability and correlation to clinical outcome after 2 years. Eur. J. Radiol. 2006, 57, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migliorini, F.; Maffulli, N.; Eschweiler, J.; Driessen, A.; Tingart, M.; Baroncini, A. Reliability of the mocart score: A systematic review. J. Orthop. Traumatol. 2021, 22, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Migliorini, F.; Maffulli, N.; Jeyaraman, M.; Schäfer, L.; Rath, B.; Huber, T. Minimal clinically important difference (mcid), patient-acceptable symptom state (pass), and substantial clinical benefit (scb) following surgical knee ligament reconstruction: A systematic review. Eur. J. Trauma Emerg. Surg. 2025, 51, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selzer, F.; Zarra, M.B.; MacFarlane, L.A.; Song, S.; McHugh, C.G.; Bronsther, C.; Huizinga, J.; Losina, E.; Katz, J.N. Objective performance tests assess aspects of function not captured by self-report in knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr. Cart. Open 2022, 4, 100311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, K.R.; Kaiser, J.T.; DeFroda, S.F.; Meeker, Z.D.; Cole, B.J. Rehabilitation, restrictions, and return to sport after cartilage procedures. Arthrosc. Sports Med. Rehabil. 2022, 4, e115–e124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherng, J.H.; Chang, S.C.; Chen, S.G.; Hsu, M.L.; Hong, P.D.; Teng, S.C.; Chan, Y.H.; Wang, C.H.; Chen, T.M.; Dai, N.T. The effect of hyperbaric oxygen and air on cartilage tissue engineering. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2012, 69, 650–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindenmann, J.; Kamolz, L.; Graier, W.; Smolle, J.; Smolle-Juettner, F.M. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy and tissue regeneration: A literature survey. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 3145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| PubMed | Scopus | WoS |

|---|---|---|

| (“Cartilage, Articular”[MeSH] OR “chondral defect” OR “chondral de-fects” OR “cartilage lesion” OR “osteochondral lesion” OR “focal carti-lage defect” OR “cartilage injury” OR “cartilage repair”) AND (“treat-ment “[MeSH] “outcome”[MeSH] “management”[MeSH] “conserva-tive”[MeSH] OR outcome OR efficacy OR safety OR “magnetic reso-nance imaging” OR MRI OR histology OR “clinical evaluation” OR “functional outcome” OR “patient reported outcome” OR PROM OR complication OR failure OR “return to sport”) | TITLE-ABS-KEY(“chondral defect” OR “chondral defects” OR “cartilage lesion” OR “osteochondral lesion” OR “cartilage injury” OR “cartilage repair”) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(“outcome” OR treatment OR efficacy OR safety OR MRI OR histology OR “clinical evaluation” OR “functional out-come” OR “patient reported outcome” OR PROM OR complication OR failure OR “return to sport”) | TS = (“chondral defect” OR “chondral defects” OR “cartilage lesion” OR “osteochondral lesion” OR “cartilage injury” OR “cartilage repair”) AND TS = (“treatment” OR outcome OR efficacy OR safety OR MRI OR histology OR “clinical evaluation” OR “functional outcome” OR “patient reported outcome” OR PROM OR complication OR failure OR “return to sport”) |

| Treatment | Main Clinical Outcome in Focal Knee/Ankle Lesions | Key Limitations/ Structural Effects |

|---|---|---|

| Structured rehabilitation and load management | Consistent short- to mid-term improvements in pain, function and return to sport when delivered as a 6–12-week, criterion-based programme focusing on closed-chain strengthening, neuromuscular control and education. | Cornerstone of care but not reliably associated with structural cartilage restoration; success depends on adherence, high-quality supervision and correct dosing. |

| Oral pharmacotherapy | Short courses reduce pain and synovitis sufficiently to enable full participation in rehabilitation, particularly during symptomatic flares. | Supportive rather than disease-modifying; no evidence of cartilage repair and long-term use is limited by gastrointestinal, renal and cardiovascular adverse events. |

| Bracing and taping | Medially directed patellofemoral braces and taping can improve pain and function in the short term and facilitate exposure to strengthening and gait retraining. | Effects attenuate over time; motion-restricting stabilising braces may cause quadriceps atrophy and reduced range of motion and are therefore discouraged in chondral phenotypes. |

| Intra-articular corticosteroids | Single injections may provide short-lived analgesia and reduce florid synovitis, occasionally unblocking rehabilitation. | Repeated courses in knee OA accelerate cartilage volume loss without sustained clinical benefit; thus, not recommended as a disease-modifying or repetitive treatment for non-arthritic focal defects. |

| Intra-articular hyaluronic acid (HA) | In patellofemoral pain, a single 6 mL injection combined with exercise improved symptoms, but not more than sham plus exercise; ankle data remain limited and heterogeneous. | Acts mainly as a symptomatic adjunct with no proven structural repair; should be reserved, if used at all, for short, clearly defined adjunctive courses within supervised rehabilitation. |

| Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) | In a randomised trial of talar osteochondral lesions, leukocyte-poor PRP provided superior pain relief and AOFAS improvement at 28 weeks compared with hyaluronan, suggesting meaningful short- to mid-term clinical benefit after high-quality rehabilitation has plateaued. | Evidence for focal knee lesions is thinner and often confounded by osteoarthritis; structural regeneration is unproven and expectations should focus on symptomatic and functional gains rather than cartilage repair. |

| Nutraceuticals | May offer modest symptomatic relief in selected patients (e.g., collagen peptides in activity-related pain), but data in focal knee and ankle chondral defects are limited. | No convincing imaging evidence of cartilage regeneration; vitamin D is recommended only in deficiency, glucosamine/chondroitin are not routinely advised, and all nutraceuticals should remain secondary to rehabilitation and evidence-based injectables. |

| Volume Fill of Cartilage Defect | |

|---|---|

| Complete filling OR minor hypertrophy: 100% to 150% filling of total defect volume | 20 |

| Major hypertrophy ≥150% OR 75% to 99% filling of total defect volume | 15 |

| 50% to 74% filling of total defect volume | 10 |

| 25% to 49% filling of total defect volume | 5 |

| <25% filling of total defect volume OR complete delamination in situ | 0 |

| Integration into adjacent cartilage | |

| Complete integration | 15 |

| Split-like defect at repair tissue and native cartilage interface ≥ 2 mm | 10 |

| Defect at repair tissue and native cartilage interface > 2 mm, but < 0% of repair tissue length | 5 |

| Defect at repair tissue and native cartilage interface ≥ 50% of repair tissue length | 0 |

| Surface of the repair tissue | |

| Surface intact | 10 |

| Surface irregular < 50% of repair tissue diameter | 5 |

| Surface irregular ≥ 50% of repair tissue diameter | 0 |

| Structure of the repair tissue | |

| Homogeneous | 10 |

| Inhomogeneous | 0 |

| Signal intensity of the repair tissue | |

| Normal | 15 |

| Minor abnormal—minor hyperintense OR minor hypointense | 10 |

| Severely abnormal—almost fluid-like OR close to subchondral plate signal | 0 |

| Bony defect or bony overgrowth | |

| No bony defect or bony overgrowth | 10 |

| Bony defect: depth < thickness of adjacent cartilage OR overgrowth < 50% of adjacent cartilage | 5 |

| Bony defect: depth ≥ thickness of adjacent cartilage OR overgrowth ≥ 50% of adjacent cartilage | 0 |

| Subchondral changes | |

| No major subchondral changes | 20 |

| Minor oedema-like marrow signal—maximum diameter < 50% of repair tissue diameter | 15 |

| Severe oedema-like marrow signal—maximum diameter ≥ 50% of repair tissue diameter | 10 |

| Subchondral cyst ≥5 mm in longest diameter OR osteonecrosis-like signal | 0 |

| Total score (0–100) | |

| PROM (Score Range) | MCID |

|---|---|

| IKDC (0–100) | 17.4 |

| KOOS–ADL (0–100) | 10 |

| KOOS–Pain (0–100) | 13.4 |

| KOOS–QoL (0–100) | 13.4 |

| KOOS–Sports/Rec (0–100) | 19.2 |

| KOOS–Symptoms (0–100) | 19.2 |

| WOMAC–Pain (0–20) | 7.5 |

| WOMAC–Physical Function (0–68) | 5.9 |

| WOMAC–Stiffness (0–8) | 18.8 |

| WOMAC–Overall (0–96) | 11.5 |

| Tegner Lysholm (0–100) | 19.2 |

| SF-36–MCS (0–100) | 0.3 |

| SF-36–PCS (0–100) | 4.6 |

| SF-36–Physical Functioning (0–100) | 17.5 |

| SF-36–Role Physical (0–100) | 12.5 |

| SF-36–Vitality (0–100) | 2.6 |

| CKRS (6–100) | 26 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Migliorini, F.; Vaishya, R.; Koettnitz, J.; Jeyaraman, M.; Schäfer, L.; Eschweiler, J.; Simeone, F. Conservative Management of Focal Chondral Lesions of the Knee and Ankle: Current Concepts. Cells 2025, 14, 1899. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14231899

Migliorini F, Vaishya R, Koettnitz J, Jeyaraman M, Schäfer L, Eschweiler J, Simeone F. Conservative Management of Focal Chondral Lesions of the Knee and Ankle: Current Concepts. Cells. 2025; 14(23):1899. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14231899

Chicago/Turabian StyleMigliorini, Filippo, Raju Vaishya, Julian Koettnitz, Madhan Jeyaraman, Luise Schäfer, Jörg Eschweiler, and Francesco Simeone. 2025. "Conservative Management of Focal Chondral Lesions of the Knee and Ankle: Current Concepts" Cells 14, no. 23: 1899. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14231899

APA StyleMigliorini, F., Vaishya, R., Koettnitz, J., Jeyaraman, M., Schäfer, L., Eschweiler, J., & Simeone, F. (2025). Conservative Management of Focal Chondral Lesions of the Knee and Ankle: Current Concepts. Cells, 14(23), 1899. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14231899