Dihydroorotate Dehydrogenase in Mitochondrial Ferroptosis and Cancer Therapy

Highlights

- DHODH connects pyrimidine synthesis with mitochondrial ferroptosis defense.

- Elevated DHODH expression promotes tumor growth and resistance.

- DHODH inhibition synergizes with GPX4 blockade to induce ferroptosis.

- Targeting DHODH represents a promising strategy to overcome cancer resistance.

- The combination of nanomedicine or immunotherapy enhances therapeutic efficacy.

- Integrating DHODH with lipid and iron metabolism pathways may guide precision therapy.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Dihydroorotate Dehydrogenase: Structure, Function, and Metabolic Roles

2.1. Structural Organization and Evolutionary Conservation

2.2. Canonical Role in Pyrimidine Metabolism

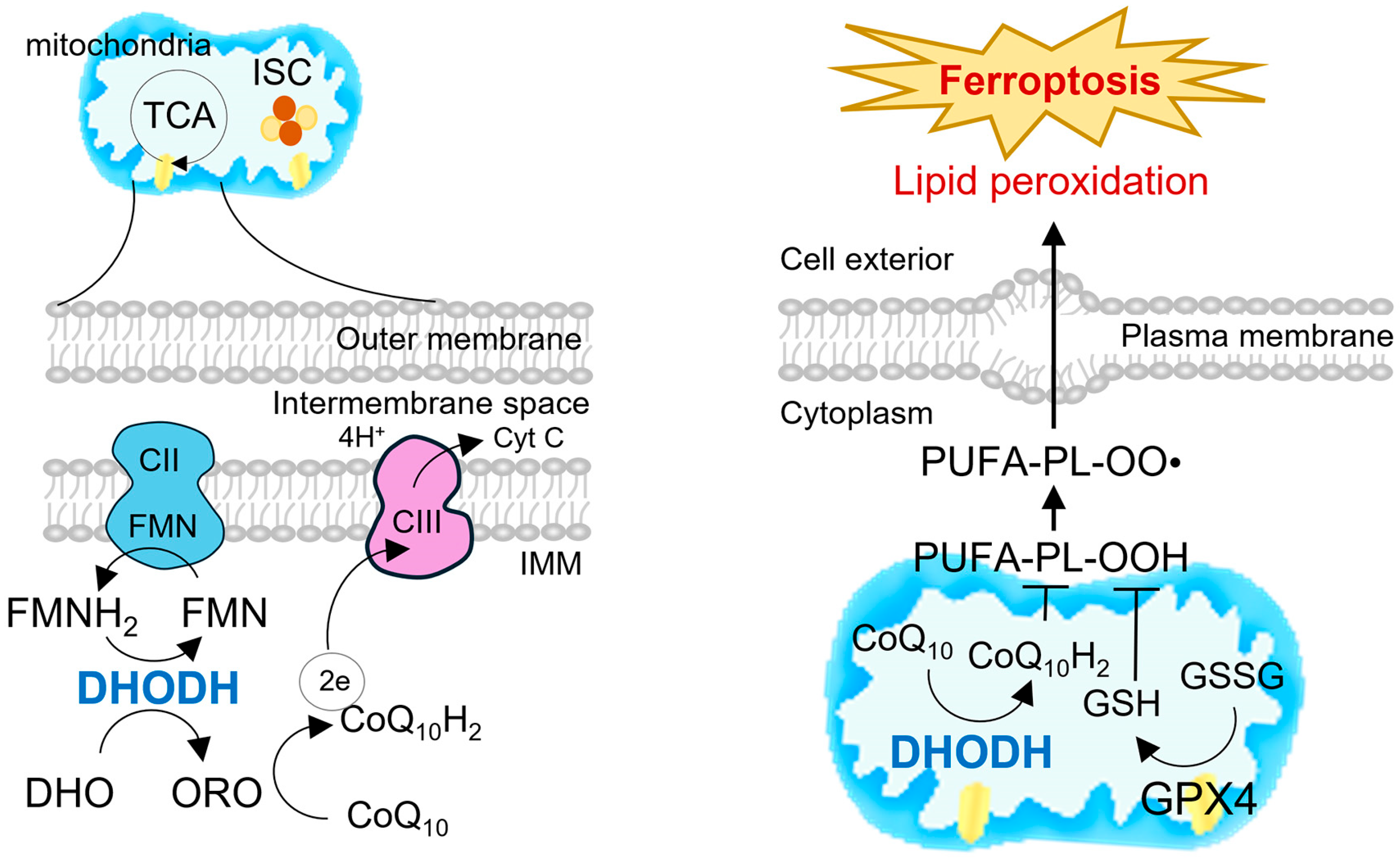

2.3. Integration with Mitochondrial Electron Transport and Redox Control

2.4. Non-Canonical Functions and Signaling Roles

2.5. Implications for Cancer Biology

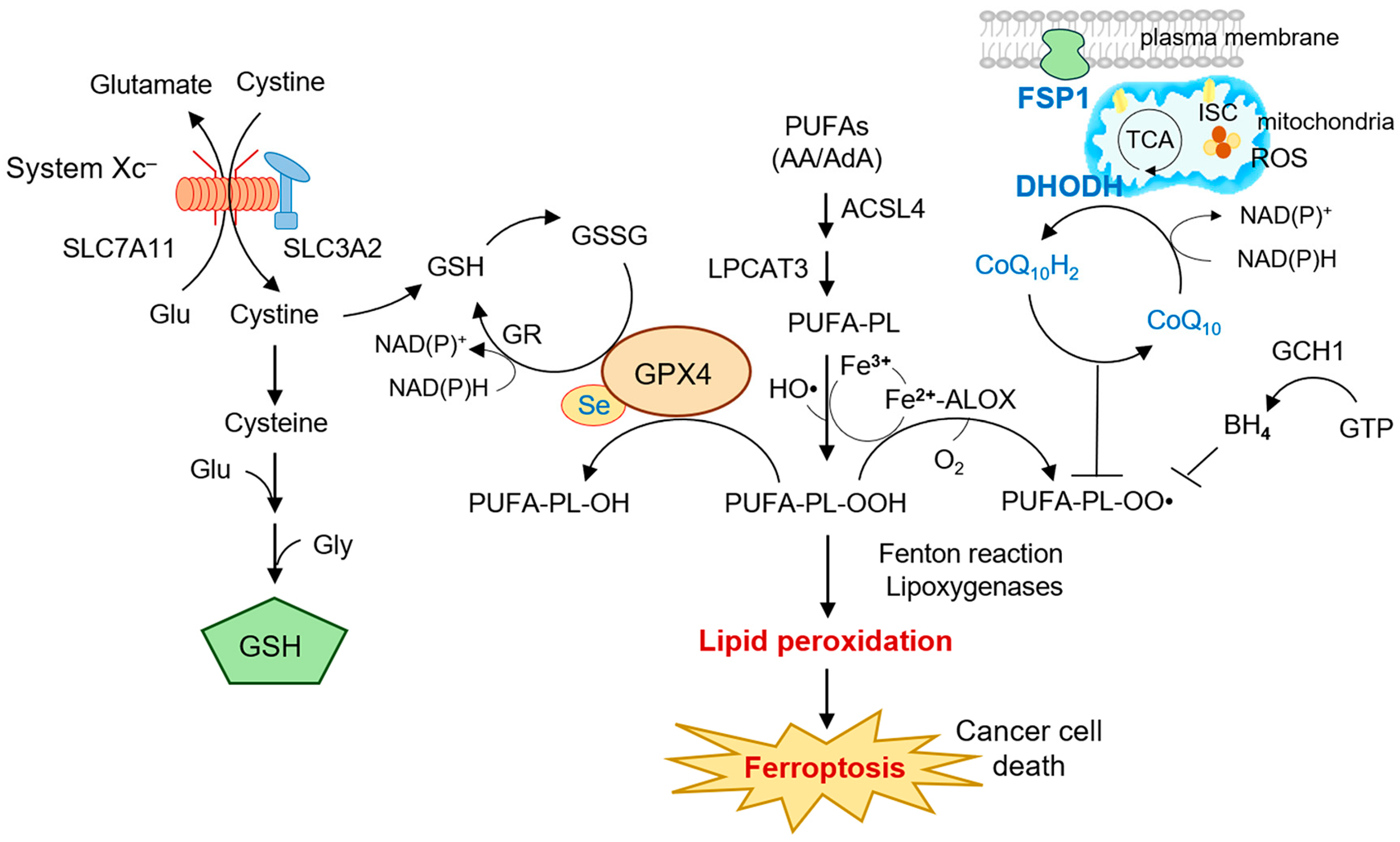

3. Mitochondrial Ferroptosis Defense: DHODH in Context

3.1. Parallel Antioxidant Systems in Ferroptosis Defense

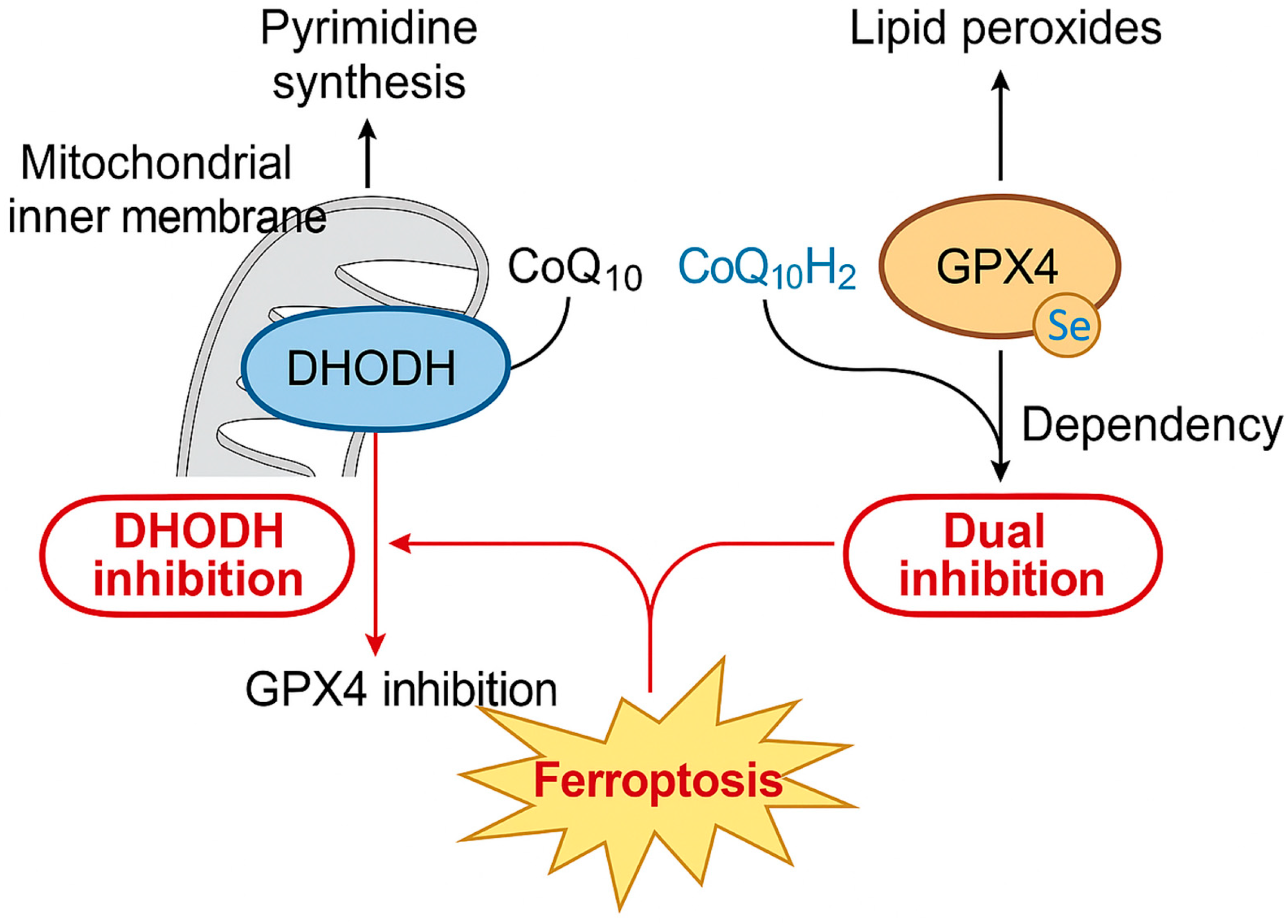

3.2. DHODH as a Mitochondrial Ferroptosis Checkpoint

3.3. Crosstalk Between DHODH and GPX4/FSP1 Pathways

3.4. Implications for Mitochondrial Ferroptosis in Cancer

4. DHODH and Cancer Progression

4.1. DHODH Expression Across Cancer Types

4.2. Oncogenic Signaling and Metabolic Reprogramming

4.3. DHODH and Therapy Resistance

4.4. Contribution to Immune Evasion and Tumor Microenvironment

4.5. Prognostic and Translational Significance

5. Therapeutic Targeting of DHODH in Ferroptosis-Induced Cancer Therapy

5.1. Conventional DHODH Inhibitors and Repurposing Strategies

5.2. Combination Therapy Strategies

5.3. Nanomedicine and Targeted Delivery Platforms

5.4. Challenges and Translational Considerations

5.5. Clinical Perspectives

6. DHODH, Ferroptosis, and Tumor Immunity

6.1. Ferroptosis and Immunogenic Cell Death

6.2. DHODH-Mediated Metabolic Adaptation and Immune Evasion

6.3. Crosstalk with Immune Checkpoint Therapy

6.4. Tumor Microenvironment Reprogramming by DHODH Inhibition

6.5. Translational and Clinical Perspectives

7. Conclusions and Perspectives

| Cancer Type | DHODH Expression/Function | Mechanism | Clinical/Prognostic Implications | Therapeutic Response to DHODH Inhibition | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colorectal cancer (CRC) | Upregulated; redistribution in 5-FU resistance | Maintains pyrimidine pools independently of mitochondria | Promotes chemoresistance; poor prognosis | Brequinar or leflunomide resensitize 5-FU–resistant CRC cells to chemotherapy and induce ferroptosis | [13] |

| Glioblastoma (GBM) | Stabilized by PRR11 | Prevents ferroptosis, enhances DNA repair | Confers temozolomide resistance | Brequinar restores temozolomide sensitivity by triggering mitochondrial ferroptosis | [14] |

| Neuroblastoma | High DHODH dependence | Rewires mevalonate/lipid metabolism | Targetable metabolic vulnerability; ferroptosis induction | DHODH blockade (brequinar) induces ferroptosis via the mevalonate pathway and suppresses tumor growth | [15] |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) | DHODH stabilized by RNF115 via YBX1–m5C modification axis | RNF115 ubiquitinates DHODH (K27) to prevent autophagic degradation, suppressing ferroptosis | YBX1/RNF115–DHODH axis promotes HCC progression; high expression predicts poor survival | Leflunomide or brequinar enhance ferroptosis and improve oxaliplatin efficacy in HCC | [74] |

| Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) | Stabilized by USP24 | Prevents DHODH degradation, suppresses lipid peroxidation | Ferroptosis resistance; poor prognosis | DHODH inhibition synergizes with ferroptosis inducers and immune checkpoint therapy | [16] |

| Skin cancers (UV-induced cSCC) | UVB-induced DHODH upregulation via STAT3 | Drives pyrimidine synthesis reprogramming under UV stress | DHODH inhibition (leflunomide) blocks tumor initiation and enhances chemoprevention/combination therapy | Leflunomide suppresses UV-induced tumorigenesis and enhances chemopreventive efficacy | [78] |

| Therapeutic Approach | Agents/Platforms | Mechanism of Action | Synergy/Applications | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional inhibitors | Leflunomide, teriflunomide, brequinar | Block pyrimidine biosynthesis and CoQ reduction | Cytostatic + ferroptosis induction; effective in CRC, HCC, GBM | [46,80,81,82] |

| Novel small molecules | Piperine derivatives, CAPE | Direct DHODH inhibition, ferroptosis activation | Synergy with GPX4 inhibitors; potential low-toxicity options | [16,83] |

| Combination with chemotherapy | Brequinar + temozolomide (GBM), leflunomide + Oxaliplatin (HCC), brequinar + 5-FU (CRC) | Dual disruption of DNA synthesis and redox defense | Overcomes chemoresistance, enhances apoptosis + ferroptosis | [13,14,80] |

| Combination with ferroptosis inducers | Erastin, RSL3 with brequinar | Inhibit SLC7A11 or GPX4 + DHODH | Potent ferroptosis amplification; effective in GPX4-low tumors | [85,86,87] |

| Combination with FSP1 inhibition | Brequinar (high dose), DHODH inhibitors + iFSP1 or genetic FSP1 loss (CRC, breast cancer) | Dual blockade of ubiquinol regeneration (DHODH in mitochondria, FSP1 at plasma membrane) | Synergistic ferroptosis induction; context-specific vulnerability | [6,88] |

| Combination with immunotherapy | DHODH inhibitors + anti–PD-1/PD-L1 | Increase lipid peroxidation and antigenicity; restore MHC-II | Reverse immune evasion, enhance T cell infiltration | [22,76] |

| Nanoplatforms | brequinar–erastin–iFSP1 nanoparticles; gemcitabine–leflunomide nanocomplex; metal–phenolic networks | Co-delivery of DHODH inhibitors with ferroptosis inducers/chemo drugs | Deep tumor penetration, reduced systemic toxicity, synergy with ICIs | [17,18,20] |

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dixon, S.J.; Lemberg, K.M.; Lamprecht, M.R.; Skouta, R.; Zaitsev, E.M.; Gleason, C.E.; Patel, D.N.; Bauer, A.J.; Cantley, A.M.; Yang, W.S.; et al. Ferroptosis: An iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death. Cell 2012, 149, 1060–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ubellacker, J.M.; Dixon, S.J. Prospects for ferroptosis therapies in cancer. Nat. Cancer 2025, 6, 1326–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stockwell, B.R.; Friedmann Angeli, J.P.; Bayir, H.; Bush, A.I.; Conrad, M.; Dixon, S.J.; Fulda, S.; Gascón, S.; Hatzios, S.K.; Kagan, V.E.; et al. Ferroptosis: A Regulated Cell Death Nexus Linking Metabolism, Redox Biology, and Disease. Cell 2017, 171, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedmann Angeli, J.P.; Krysko, D.V.; Conrad, M. Ferroptosis at the crossroads of cancer-acquired drug resistance and immune evasion. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2019, 19, 405–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Kang, R.; Tang, D.; Liu, J. Ferroptosis: Principles and significance in health and disease. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2024, 17, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, C.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Lei, G.; Yan, Y.; Lee, H.; Koppula, P.; Wu, S.; Zhuang, L.; Fang, B.; et al. DHODH-mediated ferroptosis defence is a targetable vulnerability in cancer. Nature 2021, 593, 586–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Chen, X.; Chen, L.; Lu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Deng, A.; Pan, F.; Huang, H.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; et al. DHODH-mediated mitochondrial redox homeostasis: A novel ferroptosis regulator and promising therapeutic target. Redox Biol. 2025, 85, 103788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukalova, S.; Hubackova, S.; Milosevic, M.; Ezrova, Z.; Neuzil, J.; Rohlena, J. Dihydroorotate dehydrogenase in oxidative phosphorylation and cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2020, 1866, 165759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, F.; Li, J.; Zhou, L.; Yi, R.; Chen, Y.; He, S. Targeting vulnerability in tumor therapy: Dihydroorotate dehydrogenase. Life Sci. 2025, 371, 123612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, G.; Zhuang, L.; Gan, B. Targeting ferroptosis as a vulnerability in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2022, 22, 381–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Meng, Y.; Li, D.; Yao, L.; Le, J.; Liu, Y.; Sun, Y.; Zeng, F.; Chen, X.; Deng, G. Ferroptosis in cancer: From molecular mechanisms to therapeutic strategies. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Lu, S.; Wu, L.L.; Yang, L.; Yang, L.; Wang, J. The diversified role of mitochondria in ferroptosis in cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2023, 14, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Zhang, M.; Cheng, Z.; Zhang, X.; Liang, W.; Li, S.; Li, L.; Xu, Q.; Song, S.; Liu, Z.; et al. Redistribution of defective mitochondria-mediated dihydroorotate dehydrogenase imparts 5-fluorouracil resistance in colorectal cancer. Redox Biol. 2024, 73, 103207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Z.; Xu, L.; Gu, W.; Ren, Y.; Li, R.; Zhang, S.; Chen, C.; Wang, H.; Ji, J.; Chen, J. A targetable PRR11-DHODH axis drives ferroptosis- and temozolomide-resistance in glioblastoma. Redox Biol. 2024, 73, 103220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shir, J.C.; Chen, P.Y.; Kuo, C.H.; Hsieh, C.H.; Chang, H.Y.; Lee, H.C.; Huang, C.H.; Hsu, C.H.; Hsu, W.M.; Huang, H.C.; et al. DHODH Blockade Induces Ferroptosis in Neuroblastoma by Modulating the Mevalonate Pathway. Mol. Cell Proteom. 2025, 24, 101014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; An, X.; Yang, S.; Lin, X.; Chen, Z.; Xue, Q.; Chen, X.; Wang, Y.; Yan, D.; Chen, S.; et al. The deubiquitinase USP24 suppresses ferroptosis in triple-negative breast cancer by stabilizing DHODH protein. Cell Death Dis. 2025, 16, 564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Fan, H.; Chen, Q.; Song, H.; Li, X.; Su, B.; Sun, T.; Cheng, L.; Jiang, C. Mitocytosis-inducing nanoparticles alleviate gemcitabine resistance via dual disruption of pyrimidine synthesis and redox homeostasis in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Biomaterials 2025, 325, 123630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X.; Xie, L.; Liao, Q.; Tian, J.; Peng, J.; Chen, Z.; Song, E.; Song, Y. Calcium phosphate-mineralized nanoplatform for enhanced ferroptosis and synergistic anti-PDL1 therapy in triple-negative breast cancer through multi-pathway targeting. Acta Biomater. 2025, 204, 610–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teng, D.; Swanson, K.D.; Wang, R.; Zhuang, A.; Wu, H.; Niu, Z.; Cai, L.; Avritt, F.R.; Gu, L.; Asara, J.M.; et al. DHODH modulates immune evasion of cancer cells via CDP-Choline dependent regulation of phospholipid metabolism and ferroptosis. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 3867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, N.; Wang, B.; Wang, Y.; Tian, L.; Han, S.; Zheng, B.; Feng, F.; Song, S.; Zhang, H. A Metal-Phenolic Network Nanoresensitizer Overcoming Glioblastoma Drug Resistance through the Metabolic Adaptive Strategy and Targeting Drug-Tolerant Cells. Nano Lett. 2025, 25, 9570–9580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, R.; Deng, A.; Lin, R.; Zhang, S.; Cheng, C.; Zhuang, J.; Hai, Y.; Zhao, M.; Yang, L.; Wei, G. A platinum(IV)-artesunate complex triggers ferroptosis by boosting cytoplasmic and mitochondrial lipid peroxidation to enhance tumor immunotherapy. MedComm 2024, 5, e570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chai, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Z.; Yin, S.; Luo, J.; Li, Z.; Gu, Y.; et al. Inhibition of tumor cell macropinocytosis driver DHODH reverses immunosuppression and overcomes anti-PD1 resistance. Immunity 2025, 58, 2456–2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, P.; Zhuang, H.; Shao, S.; Bai, T.; Zeng, X.; Yan, S. Engineering Biodegradable Hollow Silica/Iron Composite Nanozymes for Breast Tumor Treatment through Activation of the “Ferroptosis Storm”. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 25795–25812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Uchiumi, T.; Yagi, M.; Matsumoto, S.; Amamoto, R.; Takazaki, S.; Yamaza, H.; Nonaka, K.; Kang, D. Dihydro-orotate dehydrogenase is physically associated with the respiratory complex and its loss leads to mitochondrial dysfunction. Biosci. Rep. 2013, 33, e00021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rainger, J.; Bengani, H.; Campbell, L.; Anderson, E.; Sokhi, K.; Lam, W.; Riess, A.; Ansari, M.; Smithson, S.; Lees, M.; et al. Miller (Genee-Wiedemann) syndrome represents a clinically and biochemically distinct subgroup of postaxial acrofacial dysostosis associated with partial deficiency of DHODH. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2012, 21, 3969–3983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amos, A.; Amos, A.; Wu, L.; Xia, H. The Warburg effect modulates DHODH role in ferroptosis: A review. Cell Commun. Signal 2023, 21, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, R.A.G.; Calil, F.A.; Feliciano, P.R.; Pinheiro, M.P.; Nonato, M.C. The dihydroorotate dehydrogenases: Past and present. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2017, 632, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, R.; Purhonen, J.; Kallijärvi, J. The mitochondrial coenzyme Q junction and complex III: Biochemistry and pathophysiology. FEBS J. 2022, 289, 6936–6958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercola, J. Reductive stress and mitochondrial dysfunction: The hidden link in chronic disease. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2025, 233, 118–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, B.; Lyssiotis, C.A.; Shah, Y.M. Mitochondria-organelle crosstalk in establishing compartmentalized metabolic homeostasis. Mol. Cell 2025, 85, 1487–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orozco Rodriguez, J.M.; Wacklin-Knecht, H.P.; Clifton, L.A.; Bogojevic, O.; Leung, A.; Fragneto, G.; Knecht, W. New Insights into the Interaction of Class II Dihydroorotate Dehydrogenases with Ubiquinone in Lipid Bilayers as a Function of Lipid Composition. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ullrich, A.; Knecht, W.; Piskur, J.; Löffler, M. Plant dihydroorotate dehydrogenase differs significantly in substrate specificity and inhibition from the animal enzymes. FEBS Lett. 2002, 529, 346–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Mori, R.M.; Aleixo, M.A.A.; Zapata, L.C.C.; Calil, F.A.; Emery, F.S.; Nonato, M.C. Structural basis for the function and inhibition of dihydroorotate dehydrogenase from Schistosoma mansoni. FEBS J. 2021, 288, 930–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarmuszkiewicz, W.; Dominiak, K.; Budzinska, A.; Wojcicki, K.; Galganski, L. Mitochondrial Coenzyme Q Redox Homeostasis and Reactive Oxygen Species Production. Front. Biosci. (Landmark Ed) 2023, 28, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, A.A.; Georgiades, J.D.; Dranow, D.M.; Lorimer, D.D.; Edwards, T.; Barrett, K.F.; Craig, J.K.; Van Voorhis, W.C.; Myler, P.J.; Smith, C.L. Crystal structure of dihydroorotate dehydrogenase from Helicobacter pylori with bound flavin mononucleotide. Acta Crystallogr. F Struct. Biol. Commun. 2025, 81, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Yang, S.; Li, Y.; Ziwen, X.; Zhang, P.; Song, Q.; Yao, Y.; Pei, H. De novo nucleotide biosynthetic pathway and cancer. Genes Dis. 2023, 10, 2331–2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajzikova, M.; Kovarova, J.; Coelho, A.R.; Boukalova, S.; Oh, S.; Rohlenova, K.; Svec, D.; Hubackova, S.; Endaya, B.; Judasova, K.; et al. Reactivation of Dihydroorotate Dehydrogenase-Driven Pyrimidine Biosynthesis Restores Tumor Growth of Respiration-Deficient Cancer Cells. Cell Metab. 2019, 29, 399–416.e310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- So, J.; Lewis, A.C.; Smith, L.K.; Stanley, K.; Franich, R.; Yoannidis, D.; Pijpers, L.; Dominguez, P.; Hogg, S.J.; Vervoort, S.J.; et al. Inhibition of pyrimidine biosynthesis targets protein translation in acute myeloid leukemia. EMBO Mol. Med. 2022, 14, e15203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhaman, M.M.; Powell, D.R.; Hossain, M.A. Supramolecular Assembly of Uridine Monophosphate (UMP) and Thymidine Monophosphate (TMP) with a Dinuclear Copper(II) Receptor. ACS Omega 2017, 2, 7803–7811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, D.D.; Savani, M.R.; Levitt, M.M.; Wang, A.C.; Endress, J.E.; Bird, C.E.; Buehler, J.; Stopka, S.A.; Regan, M.S.; Lin, Y.F.; et al. De novo pyrimidine synthesis is a targetable vulnerability in IDH mutant glioma. Cancer Cell 2022, 40, 939–956.e916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diehl, F.F.; Miettinen, T.P.; Elbashir, R.; Nabel, C.S.; Darnell, A.M.; Do, B.T.; Manalis, S.R.; Lewis, C.A.; Vander Heiden, M.G. Nucleotide imbalance decouples cell growth from cell proliferation. Nat. Cell Biol. 2022, 24, 1252–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Tao, L.; Zhou, X.; Zuo, Z.; Gong, J.; Liu, X.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, C.; Sang, N.; Liu, H.; et al. DHODH and cancer: Promising prospects to be explored. Cancer Metab. 2021, 9, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, J.; Wang, J.; Ren, C.; Tang, P.; Ouyang, L.; Wang, Y. Recent advances of human dihydroorotate dehydrogenase inhibitors for cancer therapy: Current development and future perspectives. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 232, 114176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Lilienfeldt, N.; Hekimi, S. Understanding coenzyme Q. Physiol. Rev. 2024, 104, 1533–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Jia, Y.C.; Ding, Y.X.; Bai, J.; Cao, F.; Li, F. The crosstalk between ferroptosis and mitochondrial dynamic regulatory networks. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2023, 19, 2756–2771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hai, Y.; Fan, R.; Zhao, T.; Lin, R.; Zhuang, J.; Deng, A.; Meng, S.; Hou, Z.; Wei, G. A novel mitochondria-targeting DHODH inhibitor induces robust ferroptosis and alleviates immune suppression. Pharmacol. Res. 2024, 202, 107115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junco, M.; Ventura, C.; Santiago Valtierra, F.X.; Maldonado, E.N. Facts, Dogmas, and Unknowns About Mitochondrial Reactive Oxygen Species in Cancer. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlova, N.N.; Zhu, J.; Thompson, C.B. The hallmarks of cancer metabolism: Still emerging. Cell Metab. 2022, 34, 355–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, L.; Guo, Z.; Ma, L.; Yang, R.; Wu, Y.; Li, X.; Niu, J.; Chu, Q.; et al. De novo pyrimidine biosynthetic complexes support cancer cell proliferation and ferroptosis defence. Nat. Cell Biol. 2023, 25, 836–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Santana-Codina, N.; Yu, Q.; Poupault, C.; Campos, C.; Qin, X.; Sindoni, N.; Ciscar, M.; Padhye, A.; Kuljanin, M.; et al. De novo pyrimidine biosynthesis inhibition synergizes with BCL-X(L) targeting in pancreatic cancer. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 6987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Cui, K.; Kong, Y.; Yu, J.; Luo, Z.; Yang, X.; Gong, L.; Xie, Y.; Lin, J.; Liu, C.; et al. Targeting both the enzymatic and non-enzymatic functions of DHODH as a therapeutic vulnerability in c-Myc-driven cancer. Cell Rep. 2025, 44, 115327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y.; Liang, X.; Kong, P.; Cheng, Y.; Cui, H.; Yan, T.; Wang, J.; Zhang, L.; Liu, Y.; Guo, S.; et al. Elevated DHODH expression promotes cell proliferation via stabilizing β-catenin in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, D.; Wang, W.; Chen, W.; Lian, F.; Lang, L.; Huang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, N.; Chen, Y.; Liu, M.; et al. Pharmacological inhibition of dihydroorotate dehydrogenase induces apoptosis and differentiation in acute myeloid leukemia cells. Haematologica 2018, 103, 1472–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.Z.; Jin, X.; Li, W.T.; Tao, H.; Song, S.J.; Fan, Z.W.; Jiang, W.; Liang, J.W.; Bai, J. Dihydroorotate dehydrogenase promotes cell proliferation and suppresses cell death in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and colorectal carcinoma. Transl. Cancer Res. 2023, 12, 2294–2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Kang, R.; Klionsky, D.J.; Tang, D. GPX4 in cell death, autophagy, and disease. Autophagy 2023, 19, 2621–2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Roh, J.L. Targeting GPX4 in human cancer: Implications of ferroptosis induction for tackling cancer resilience. Cancer Lett. 2023, 559, 216119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Roh, J.L. SLC7A11 as a Gateway of Metabolic Perturbation and Ferroptosis Vulnerability in Cancer. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Stockwell, B.R.; Conrad, M. Ferroptosis: Mechanisms, biology and role in disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2021, 22, 266–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bersuker, K.; Hendricks, J.M.; Li, Z.; Magtanong, L.; Ford, B.; Tang, P.H.; Roberts, M.A.; Tong, B.; Maimone, T.J.; Zoncu, R.; et al. The CoQ oxidoreductase FSP1 acts parallel to GPX4 to inhibit ferroptosis. Nature 2019, 575, 688–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doll, S.; Freitas, F.P.; Shah, R.; Aldrovandi, M.; da Silva, M.C.; Ingold, I.; Goya Grocin, A.; Xavier da Silva, T.N.; Panzilius, E.; Scheel, C.H.; et al. FSP1 is a glutathione-independent ferroptosis suppressor. Nature 2019, 575, 693–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, D.Y.; Chen, X.; Liu, Y.; Williams, C.M.; Pedersen, L.C.; Stafford, D.W.; Tie, J.K. A genome-wide CRISPR-Cas9 knockout screen identifies FSP1 as the warfarin-resistant vitamin K reductase. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gan, B. Mitochondrial regulation of ferroptosis. J. Cell Biol. 2021, 220, e202105043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Q.; Tang, Z.; Luo, L. The crosstalk between oncogenic signaling and ferroptosis in cancer. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2024, 197, 104349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berndt, C.; Alborzinia, H.; Amen, V.S.; Ayton, S.; Barayeu, U.; Bartelt, A.; Bayir, H.; Bebber, C.M.; Birsoy, K.; Böttcher, J.P.; et al. Ferroptosis in health and disease. Redox Biol. 2024, 75, 103211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Wang, X.; Qin, B.; Hu, R.; Miao, R.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, L.; Liu, T. Targeting NQO1 induces ferroptosis and triggers anti-tumor immunity in immunotherapy-resistant KEAP1-deficient cancers. Drug Resist. Updat. 2024, 77, 101160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, J.D.; Dinkova-Kostova, A.T.; Tew, K.D. Oxidative Stress in Cancer. Cancer Cell 2020, 38, 167–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mailloux, R.J. Proline and dihydroorotate dehydrogenase promote a hyper-proliferative state and dampen ferroptosis in cancer cells by rewiring mitochondrial redox metabolism. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 2024, 1871, 119639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Song, Y.; Liu, H.; Jin, Y.; Li, R.; Zhu, X. DHODH Inhibition Exerts Synergistic Therapeutic Effect with Cisplatin to Induce Ferroptosis in Cervical Cancer through Regulating mTOR Pathway. Cancers 2023, 15, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubackova, S.; Davidova, E.; Boukalova, S.; Kovarova, J.; Bajzikova, M.; Coelho, A.; Terp, M.G.; Ditzel, H.J.; Rohlena, J.; Neuzil, J. Replication and ribosomal stress induced by targeting pyrimidine synthesis and cellular checkpoints suppress p53-deficient tumors. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lafita-Navarro, M.C.; Venkateswaran, N.; Kilgore, J.A.; Kanji, S.; Han, J.; Barnes, S.; Williams, N.S.; Buszczak, M.; Burma, S.; Conacci-Sorrell, M. Inhibition of the de novo pyrimidine biosynthesis pathway limits ribosomal RNA transcription causing nucleolar stress in glioblastoma cells. PLoS Genet. 2020, 16, e1009117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olsen, T.K.; Dyberg, C.; Embaie, B.T.; Alchahin, A.; Milosevic, J.; Ding, J.; Otte, J.; Tümmler, C.; Hed Myrberg, I.; Westerhout, E.M.; et al. DHODH is an independent prognostic marker and potent therapeutic target in neuroblastoma. JCI Insight 2022, 7, e153836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, N.; Weinberg, E.M.; Nguyen, A.; Liberti, M.V.; Goodarzi, H.; Janjigian, Y.Y.; Paty, P.B.; Saltz, L.B.; Kingham, T.P.; Loo, J.M.; et al. PCK1 and DHODH drive colorectal cancer liver metastatic colonization and hypoxic growth by promoting nucleotide synthesis. Elife 2019, 8, e52135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Hu, L.; Zhang, M.; Liu, S.; Xu, S.; Chow, V.L.; Chan, J.Y.; Wong, T.S. Mitochondrial DHODH regulates hypoxia-inducible factor 1 expression in OTSCC. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2022, 12, 48–67. [Google Scholar]

- Li, O.; An, K.; Wang, H.; Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Huang, L.; Du, Y.; Qin, N.; Dong, J.; Wei, J.; et al. Targeting YBX1-m5C mediates RNF115 mRNA circularisation and translation to enhance vulnerability of ferroptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin. Transl. Med. 2025, 15, e70270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amos, A.; Jiang, N.; Zong, D.; Gu, J.; Zhou, J.; Yin, L.; He, X.; Xu, Y.; Wu, L. Depletion of SOD2 enhances nasopharyngeal carcinoma cell radiosensitivity via ferroptosis induction modulated by DHODH inhibition. BMC Cancer 2023, 23, 117, Erratum in BMC Cancer 2023, 23, 462. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-023-10969-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Q.; Tang, W.; Li, X.; Ding, Y.; Chen, X.; Cao, W.; Wang, X.; Mo, W.; Su, Z.; Zhang, Q.; et al. Mitochondrial-targeted brequinar liposome boosted mitochondrial-related ferroptosis for promoting checkpoint blockade immunotherapy in bladder cancer. J. Control. Release 2023, 363, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, C.; Mori, N. Pivotal role of dihydroorotate dehydrogenase as a therapeutic target in adult T-cell leukemia. Eur. J. Haematol. 2024, 113, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, M.; Dousset, L.; Michon, P.; Mahfouf, W.; Muzotte, E.; Bergeron, V.; Bortolotto, D.; Rossignol, R.; Moisan, F.; Taieb, A.; et al. UVB-induced DHODH upregulation, which is driven by STAT3, is a promising target for chemoprevention and combination therapy of photocarcinogenesis. Oncogenesis 2019, 8, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madak, J.T.; Bankhead, A., 3rd; Cuthbertson, C.R.; Showalter, H.D.; Neamati, N. Revisiting the role of dihydroorotate dehydrogenase as a therapeutic target for cancer. Pharmacol. Ther. 2019, 195, 111–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, M.; Ding, Y.; Huang, S.; Liu, Y.; Xiao, J.; Yu, H.; Lu, L.; Wang, X. Lysyl oxidase-like 3 restrains mitochondrial ferroptosis to promote liver cancer chemoresistance by stabilizing dihydroorotate dehydrogenase. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 3123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhou, Y.; Xu, J.; Zhou, X.; Huang, Z.; Zeng, T.; Yang, X.; Tao, L.; Gou, K.; Zhong, X.; et al. A novel series of teriflunomide derivatives as orally active inhibitors of human dihydroorotate dehydrogenase for the treatment of colorectal carcinoma. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 238, 114489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullen, N.J.; Shukla, S.K.; Thakur, R.; Kollala, S.S.; Wang, D.; Chaika, N.; Santana, J.F.; Miklavcic, W.R.; LaBreck, D.A.; Mallareddy, J.R.; et al. DHODH inhibition enhances the efficacy of immune checkpoint blockade by increasing cancer cell antigen presentation. Elife 2024, 12, e87292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.F.; Hong, L.H.; Fan, S.Y.; Zhu, L.; Yu, Z.P.; Chen, C.; Kong, L.Y.; Luo, J.G. Discovery of piperine derivatives as inhibitors of human dihydroorotate dehydrogenase to induce ferroptosis in cancer cells. Bioorg Chem. 2024, 150, 107594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian, S.; Merz, C.; Evans, L.; Gradl, S.; Seidel, H.; Friberg, A.; Eheim, A.; Lejeune, P.; Brzezinka, K.; Zimmermann, K.; et al. The novel dihydroorotate dehydrogenase (DHODH) inhibitor BAY 2402234 triggers differentiation and is effective in the treatment of myeloid malignancies. Leukemia 2019, 33, 2403–2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Min, J. DHODH tangoing with GPX4 on the ferroptotic stage. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.J.; Zhang, M.M.; Liu, D.M.; Huang, L.L.; Yu, H.Q.; Wang, Y.; Xing, L.; Jiang, H.L. Glutathione depletion and dihydroorotate dehydrogenase inhibition actuated ferroptosis-augment to surmount triple-negative breast cancer. Biomaterials 2024, 305, 122447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Yang, N.; Zhou, W.; Akhtar, M.H.; Zhou, W.; Liu, C.; Song, S.; Li, Y.; Han, W.; Yu, C. Exploiting Cancer Vulnerabilities by Blocking of the DHODH and GPX4 Pathways: A Multifunctional Bodipy/PROTAC Nanoplatform for the Efficient Synergistic Ferroptosis Therapy. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2023, 12, e2300871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishima, E.; Nakamura, T.; Zheng, J.; Zhang, W.; Mourão, A.S.D.; Sennhenn, P.; Conrad, M. DHODH inhibitors sensitize to ferroptosis by FSP1 inhibition. Nature 2023, 619, E9–E18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, D.; Stratikopoulos, E.; Ozturk, S.; Steinbach, N.; Pegno, S.; Schoenfeld, S.; Yong, R.; Murty, V.V.; Asara, J.M.; Cantley, L.C.; et al. PTEN Regulates Glutamine Flux to Pyrimidine Synthesis and Sensitivity to Dihydroorotate Dehydrogenase Inhibition. Cancer Discov. 2017, 7, 380–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Yang, J.; Liang, Z.; Li, Z.; Xiong, W.; Fan, Q.; Shen, Z.; Liu, J.; Xu, Y. Synergistic Functional Nanomedicine Enhances Ferroptosis Therapy for Breast Tumors by a Blocking Defensive Redox System. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 2705–2713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Sun, M.; Huang, H.; Jin, W.L. Drug repurposing for cancer therapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, X.; Chen, D.; Yu, J. Radiotherapy combined with immunotherapy: The dawn of cancer treatment. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Qi, Z.; Li, X.; Zhao, Y. Ferroptosis: CD8(+)T cells’ blade to destroy tumor cells or poison for self-destruction. Cell Death Discov. 2025, 11, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaafeen, B.H.; Ali, B.R.; Elkord, E. Resistance mechanisms to immune checkpoint inhibitors: Updated insights. Mol. Cancer 2025, 24, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.B.; Kim, H.R.; Ha, S.J. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in 10 Years: Contribution of Basic Research and Clinical Application in Cancer Immunotherapy. Immune Netw. 2022, 22, e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimnezhad, M.; Valizadeh, A.; Yousefi, B. Ferroptosis and immunotherapy: Breaking barriers in cancer treatment resistance. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2025, 214, 104907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, G.; Zhuang, L.; Gan, B. The roles of ferroptosis in cancer: Tumor suppression, tumor microenvironment, and therapeutic interventions. Cancer Cell 2024, 42, 513–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, K.; Wang, K.; Huang, Z. Ferroptosis and the tumor microenvironment. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2024, 43, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kay, E.J.; Zanivan, S. The tumor microenvironment is an ecosystem sustained by metabolic interactions. Cell Rep. 2025, 44, 115432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arner, E.N.; Rathmell, J.C. Metabolic programming and immune suppression in the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Cell 2023, 41, 421–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Kang, L.; Dai, X.; Chen, J.; Chen, Z.; Wang, M.; Jiang, H.; Wang, X.; Bu, S.; Liu, X.; et al. Manganese induces tumor cell ferroptosis through type-I IFN dependent inhibition of mitochondrial dihydroorotate dehydrogenase. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2022, 193, 202–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, J.; Roh, J.-L. Dihydroorotate Dehydrogenase in Mitochondrial Ferroptosis and Cancer Therapy. Cells 2025, 14, 1889. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14231889

Lee J, Roh J-L. Dihydroorotate Dehydrogenase in Mitochondrial Ferroptosis and Cancer Therapy. Cells. 2025; 14(23):1889. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14231889

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Jaewang, and Jong-Lyel Roh. 2025. "Dihydroorotate Dehydrogenase in Mitochondrial Ferroptosis and Cancer Therapy" Cells 14, no. 23: 1889. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14231889

APA StyleLee, J., & Roh, J.-L. (2025). Dihydroorotate Dehydrogenase in Mitochondrial Ferroptosis and Cancer Therapy. Cells, 14(23), 1889. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14231889