EPO-R76E Enhances Retinal Pigment Epithelium Viability Under Mitochondrial Oxidative Stress Induced by Paraquat

Abstract

1. Introduction

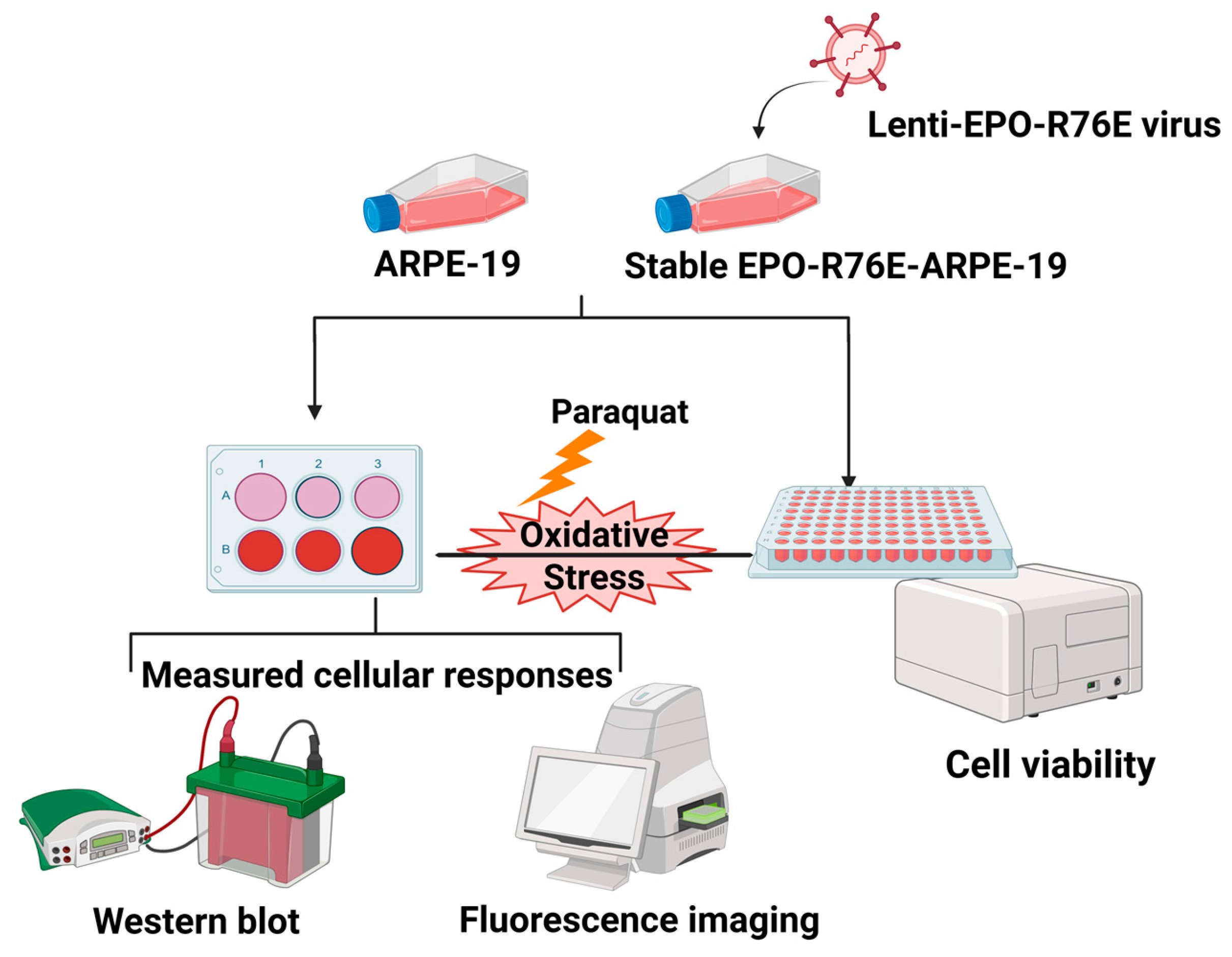

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plasmid Preparation

2.1.1. Gradient PCR Amplification of EPO-R76E Insert

2.1.2. Gel Electrophoresis and DNA Elution

2.1.3. Quantification and Restriction Digestion

2.1.4. Ligation and Bacterial Transformation

2.1.5. Colony Screening and Plasmid Isolation

2.1.6. Confirmation by Restriction Analysis and In Silico Validation

2.1.7. Validation of Lenti-EPO-R76E Plasmid

2.2. Lentivirus Production

2.2.1. Cell Seeding for Lentivirus Production

2.2.2. Plasmid Transfection

2.2.3. Virus Harvesting and Purification

2.3. Stable ARPE-19 Cell Line Generation

2.3.1. Cell Preparation and Transduction

2.3.2. Selection of Stable Clones

2.3.3. Validation of Stable EPO-R76E Expression in ARPE-19 Cells

2.4. Cell Viability Assay

2.4.1. Cell Seeding for Cell Viability Assay

2.4.2. Paraquat Treatment

2.4.3. WST-1 Assay for Viability Measurement

2.4.4. Absorbance Measurement

2.4.5. Data Analysis

2.5. Protein Expression Analysis

2.5.1. Cell Culture and Protein Extraction

2.5.2. Protein Quantification

2.5.3. Electrophoresis and Transfer

2.5.4. Primary Antibody Incubation

- Ferritin (Rabbit monoclonal)—MA5-32244, Invitrogen, 1:5000;

- SQSTM1/p62 (Rabbit polyclonal)—Abcam, Cat. No: ab109012, 1:10,000;

- GPX4 (Rabbit monoclonal)—Abcam, Cat. No: ab125066 or Proteintech, Cat. No: 67763-1-Ig, 1:1000;

- NRF2 polyclonal antibody—PA5-27882, Invitrogen, 1:1000;

- Phospho-AMPKα (Thr172, Rabbit monoclonal)—Cell Signaling Technology, Cat. No: 2537S, 1:1000;

- β-Actin (Mouse monoclonal)—Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Cat. No: SC-47778, 1:2000.

2.5.5. Secondary Antibody Incubation and Detection

2.5.6. Densitometric Analysis

2.6. Intracellular Ferrous Ion Content Assay

2.6.1. Cell Seeding and Treatment for Intracellular Ferrous Ion Content Assay

2.6.2. FerroOrange Staining

2.6.3. Imaging and Quantification of FerroOrange Staining

2.7. Reactive Oxygen Species Analysis

2.7.1. Cell Seeding and Treatment for ROS Analysis

2.7.2. DCFDA Staining

2.7.3. Imaging and Quantification of DCFDA Staining

3. Results

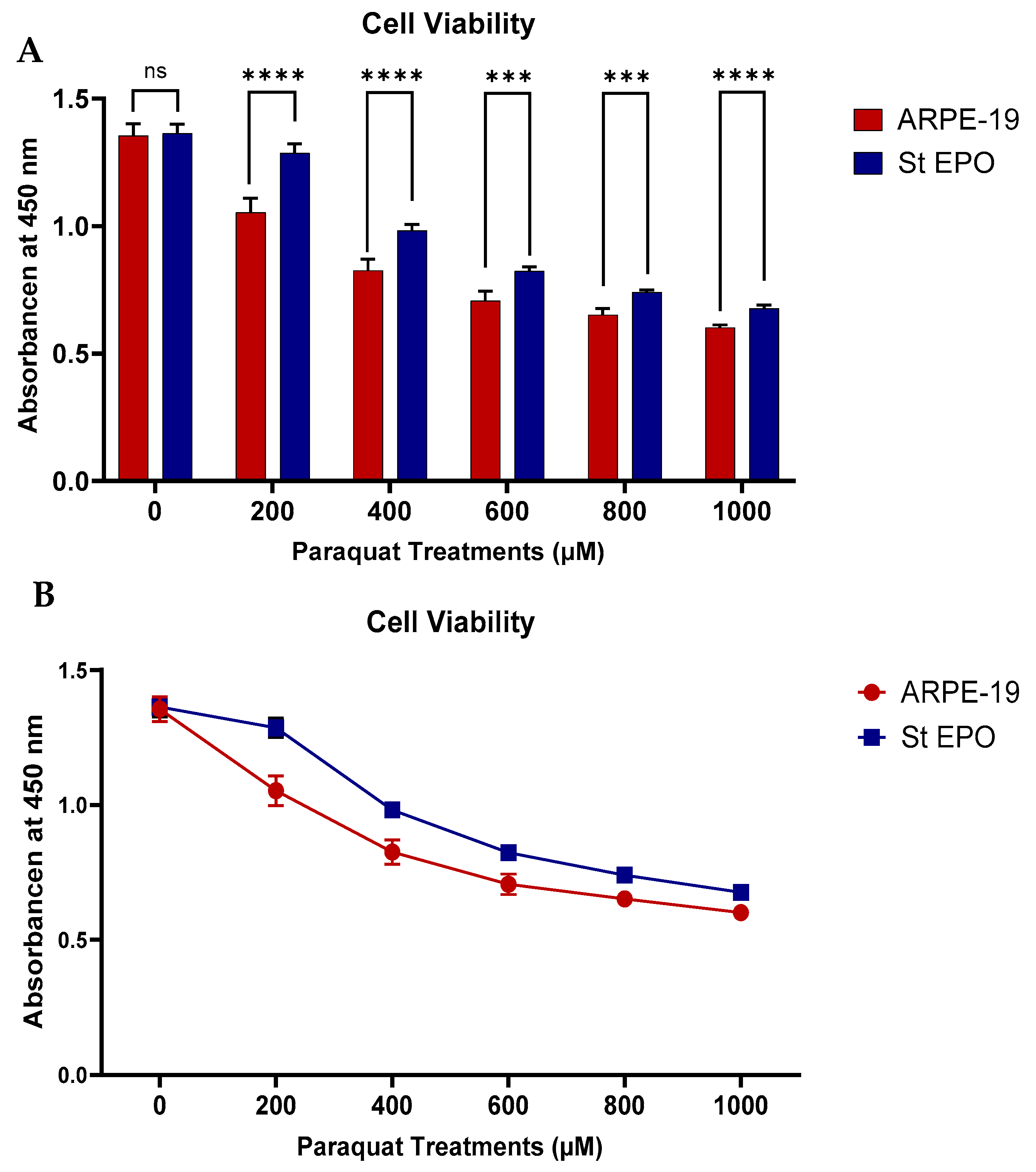

3.1. Cell Viability Under Oxidative Stress

3.2. Impact on Oxidative Stress-Related Proteins by EPO-R76E

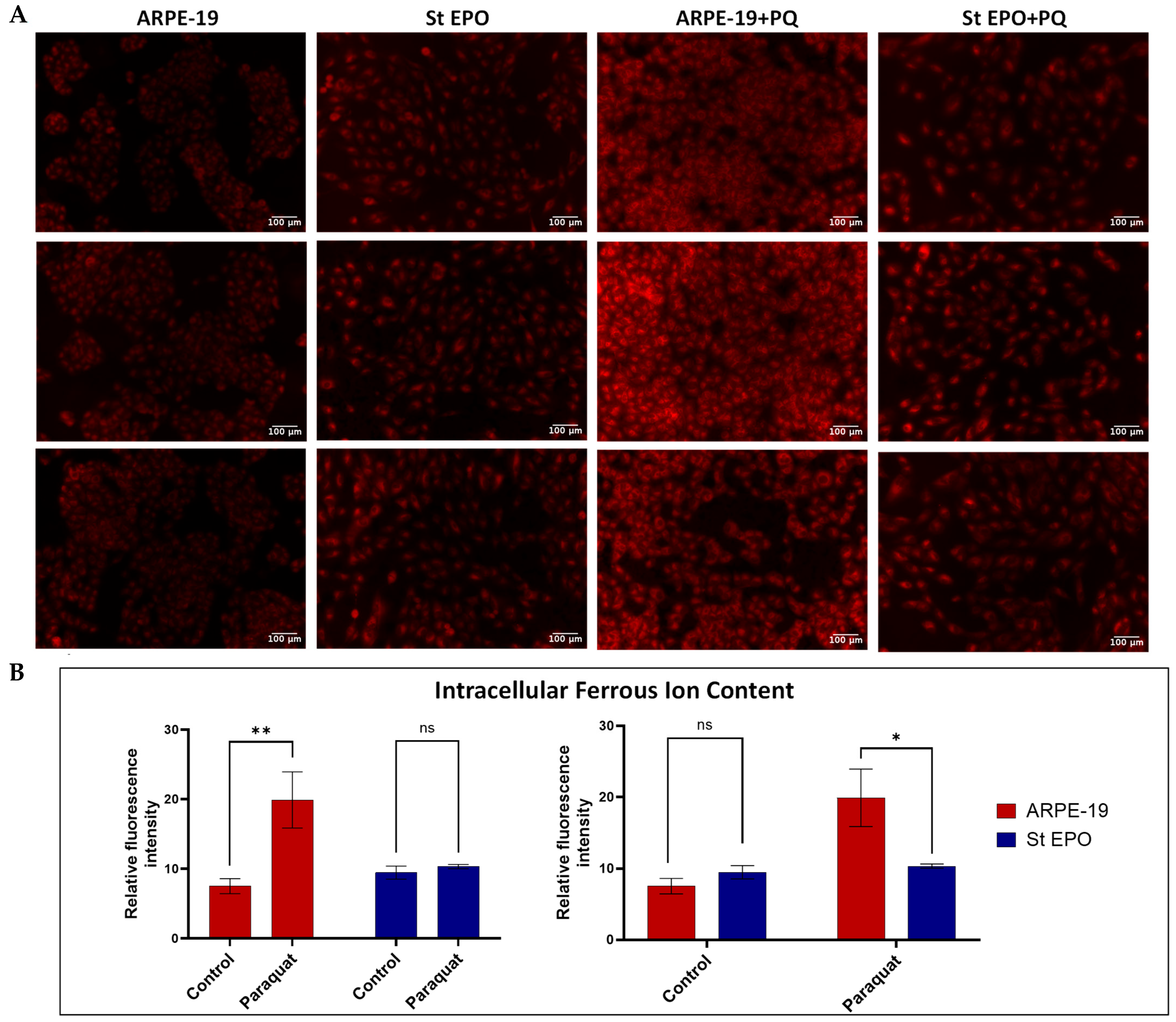

3.3. Impact of EPO-R76E on Intracellular Ferrous Ion Content

3.4. Impact of EPO-R76E on Reactive Oxygen Species Content

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMD | Age-related macular degeneration |

| RPE | Retinal pigment epithelium |

| EPO | Erythropoietin |

| EPO-R76E | Non-erythropoietic erythropoietin variant |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| GPX4 | Glutathione peroxidase 4 |

| NRF2 | Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 |

| p-AMPK | Phosphorylated AMP-activated protein kinase |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline |

| DCFDA | 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescin diacetate |

| DMEM | Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium |

| SDS-PAGE | Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate-Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis |

| FBS | Fetal Bovine Serum |

| PCR | Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| GFP | Green Fluorescent Protein |

| PEI | Polyethylenimine |

| ICM | Incomplete culture medium |

| DMSO | Dimethyl sulfoxide |

References

- Stahl, A. The Diagnosis and Treatment of Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2020, 117, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Guimaraes, T.A.C.; Varela, M.D.; Georgiou, M.; Michaelides, M. Treatments for dry age-related macular degeneration: Therapeutic avenues, clinical trials and future directions. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2022, 106, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, O. The retinal pigment epithelium in visual function. Physiol. Rev. 2005, 85, 845–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, N.M.; Bhardwaj, S.; Barclay, C.; Gaspar, L.; Schwartz, J. Global Burden of Dry Age-Related Macular Degeneration: A Targeted Literature Review. Clin. Ther. 2021, 43, 1792–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaarniranta, K.; Uusitalo, H.; Blasiak, J.; Felszeghy, S.; Kannan, R.; Kauppinen, A.; Salminen, A.; Sinha, D.; Ferrington, D. Mechanisms of mitochondrial dysfunction and their impact on age-related macular degeneration. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2020, 79, 100858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salceda, R. Light Pollution and Oxidative Stress: Effects on Retina and Human Health. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, T.; Guo, X.; Sun, Y. Iron Accumulation and Lipid Peroxidation in the Aging Retina: Implication of Ferroptosis in Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Aging Dis. 2021, 12, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcão, A.S.; Pedro, M.L.; Tenreiro, S.; Seabra, M.C. Targeting Lysosomal Dysfunction and Oxidative Stress in Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Si, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Zhao, J. The Role of Retinal Pigment Epithelial Cells in Age-Related Macular Degeneration: Phagocytosis and Autophagy. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.; Wei, S.; Nguyen, T.H.; Jo, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Park, W.; Gariani, K.; Oh, C.-M.; Kim, H.H.; Ha, K.-T.; et al. Mitochondria-associated programmed cell death as a therapeutic target for age-related disease. Exp. Mol. Med. 2023, 55, 1595–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, S.J.; Lemberg, K.M.; Lamprecht, M.R.; Skouta, R.; Zaitsev, E.M.; Gleason, C.E.; Patel, D.N.; Bauer, A.J.; Cantley, A.M.; Yang, W.S.; et al. Ferroptosis: An iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death. Cell 2012, 149, 1060–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswal, M.R.; Wang, Z.; Paulson, R.J.; Uddin, R.R.; Tong, Y.; Zhu, P.; Li, H.; Lewin, A.S. Erythropoietin gene therapy delays retinal degeneration resulting from oxidative stress in the retinal pigment epithelium. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeJulius, C.R.; Bernardo-Colón, A.; Naguib, S.; Backstrom, J.; Kavanaugh, T.; Gupta, M.; Duvall, C.; Rex, T. Microsphere antioxidant and sustained erythropoietin-R76E release functions cooperate to reduce traumatic optic neuropathy. J. Control. Release 2020, 329, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sullivan, T.A.; Geisert, E.E.; Templeton, J.P.; Rex, T.S. Dose-dependent treatment of optic nerve crush by exogenous systemic mutant erythropoietin. Exp. Eye Res. 2012, 96, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baek, A.; Yoon, S.; Kim, J.; Baek, Y.M.; Park, H.; Lim, D.; Chung, H.; Kim, D.-E. Autophagy and KRT8/keratin 8 protect degeneration of retinal pigment epithelium under oxidative stress. Autophagy 2017, 13, 248–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, Q.; Shen, Q.; Zhu, W.; Zhang, S.; Ke, J.; Lu, Z. Paraquat-induced ferroptosis suppression via NRF2 expression regulation. Toxicol. Vitr. 2023, 92, 105655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, C.; Liu, Y. Glutathione depletion induces ferroptosis, autophagy, and premature cell senescence in retinal pigment epithelial cells. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henning, Y.; Blind, U.S.; Larafa, S.; Matschke, J.; Fandrey, J. Hypoxia aggravates ferroptosis in RPE cells by promoting the Fenton reaction. Cell Death Dis. 2022, 13, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Monian, P.; Pan, Q.; Zhang, W.; Xiang, J.; Jiang, X. Ferroptosis is an autophagic cell death process. Cell Res. 2016, 26, 1021–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockwell, B.R.; Angeli, J.P.F.; Bayir, H.; Bush, A.I.; Conrad, M.; Dixon, S.J.; Fulda, S.; Gascón, S.; Hatzios, S.K.; Kagan, V.E.; et al. Ferroptosis: A Regulated Cell Death Nexus Linking Metabolism, Redox Biology, and Disease. Cell 2017, 171, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjørkøy, G.; Lamark, T.; Pankiv, S.; Øvervatn, A.; Brech, A.; Johansen, T. Monitoring Autophagic Degradation of p62/SQSTM1. Methods Enzymol. 2009, 451, 181–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komatsu, M.; Kurokawa, H.; Waguri, S.; Taguchi, K.; Kobayashi, A.; Ichimura, Y.; Sou, Y.-S.; Ueno, I.; Sakamoto, A.; Tong, K.I.; et al. The selective autophagy substrate p62 activates the stress responsive transcription factor Nrf2 through inactivation of Keap1. Nat. Cell Biol. 2010, 12, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, F.; Sun, Q.; Zhang, S.; Ye, L.; Xu, Y.; Deng, G.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, S.; Liu, B.; Chen, Q. The dual role of p62 in ferroptosis of glioblastoma according to p53 status. Cell Biosci. 2022, 12, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, W.S.; SriRamaratnam, R.; Welsch, M.E.; Shimada, K.; Skouta, R.; Viswanathan, V.S.; Cheah, J.H.; Clemons, P.A.; Shamji, A.F.; Clish, C.B.; et al. Regulation of Ferroptotic Cancer Cell Death by GPX4. Cell 2014, 156, 317–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodson, M.; Castro-Portuguez, R.; Zhang, D.D. NRF2 plays a critical role in mitigating lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis. Redox Biol. 2019, 23, 101107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemmerer, Z.A.; Ader, N.R.; Mulroy, S.S.; Eggler, A.L. Comparison of human Nrf2 antibodies: A tale of two proteins. Toxicol. Lett. 2015, 238, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pi, J.; Bai, Y.; Reece, J.M.; Williams, J.; Liu, D.; Freeman, M.L.; Fahl, W.E.; Shugar, D.; Liu, J.; Qu, W.; et al. Molecular Mechanism of Human Nrf2 Activation and Degradation: Role of Sequential Phosphorylation by Protein Kinase CK2. Free Radic Biol. Med. 2007, 42, 1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tóthová, Z.; Tomc, J.; Debeljak, N.; Solár, P. STAT5 as a Key Protein of Erythropoietin Signalization. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.B.; Wu, Y.T.; Wu, T.P.; Wei, Y.H. Role of AMPK-mediated adaptive responses in human cells with mitochondrial dysfunction to oxidative stress. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) Gen. Subj. 2014, 1840, 1331–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardie, D.G.; Ross, F.A.; Hawley, S.A. AMPK: A nutrient and energy sensor that maintains energy homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012, 13, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.S.; Li, M.; Ma, T.; Zong, Y.; Cui, J.; Feng, J.-W.; Wu, Y.-Q.; Lin, S.-Y.; Lin, S.-C. Metformin Activates AMPK Through the Lysosomal Pathway. Cell Metab. 2016, 24, 521–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Cao, F.; Yin, H.; Huang, Z.; Lin, Z.; Mao, N.; Sun, B.; Wang, G. Ferroptosis: Past, present and future. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galaris, D.; Barbouti, A.; Pantopoulos, K. Iron homeostasis and oxidative stress: An intimate relationship. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) Mol. Cell Res. 2019, 1866, 118535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alam, J.; Ponnam, A.; Souvangini, A.; Gopi, S.; Ildefonso, C.J.; Biswal, M.R. EPO-R76E Enhances Retinal Pigment Epithelium Viability Under Mitochondrial Oxidative Stress Induced by Paraquat. Cells 2025, 14, 1794. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14221794

Alam J, Ponnam A, Souvangini A, Gopi S, Ildefonso CJ, Biswal MR. EPO-R76E Enhances Retinal Pigment Epithelium Viability Under Mitochondrial Oxidative Stress Induced by Paraquat. Cells. 2025; 14(22):1794. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14221794

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlam, Jemima, Alekhya Ponnam, Arusmita Souvangini, Sundaramoorthy Gopi, Cristhian J. Ildefonso, and Manas R. Biswal. 2025. "EPO-R76E Enhances Retinal Pigment Epithelium Viability Under Mitochondrial Oxidative Stress Induced by Paraquat" Cells 14, no. 22: 1794. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14221794

APA StyleAlam, J., Ponnam, A., Souvangini, A., Gopi, S., Ildefonso, C. J., & Biswal, M. R. (2025). EPO-R76E Enhances Retinal Pigment Epithelium Viability Under Mitochondrial Oxidative Stress Induced by Paraquat. Cells, 14(22), 1794. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14221794