Inflammation Regulates the Multi-Step Process of Retinal Regeneration in Zebrafish

Abstract

:1. Inflammation and Tissue Regeneration

2. Persistent and Regenerative Neurogenesis in Adult Zebrafish

3. Activation of Microglia

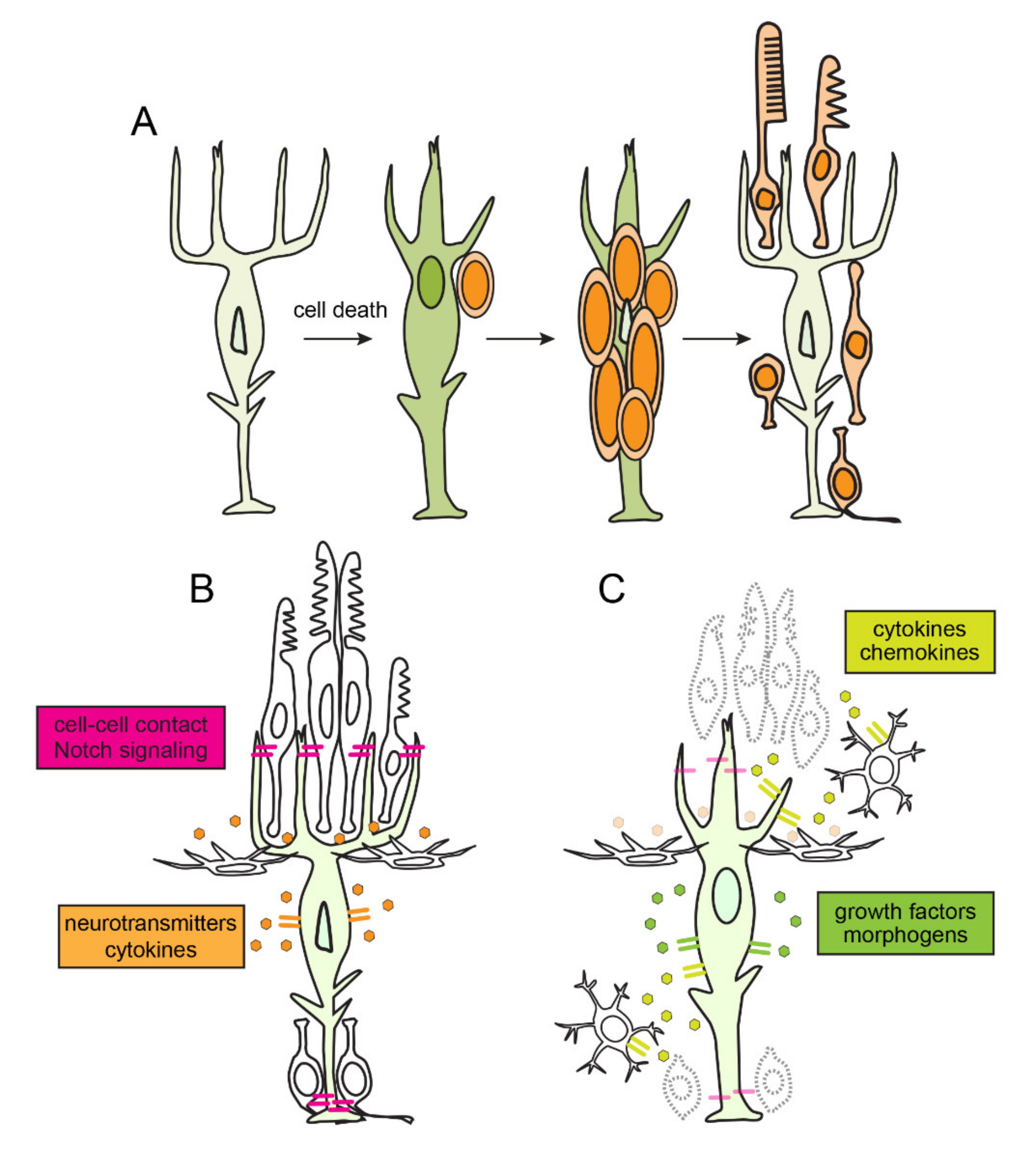

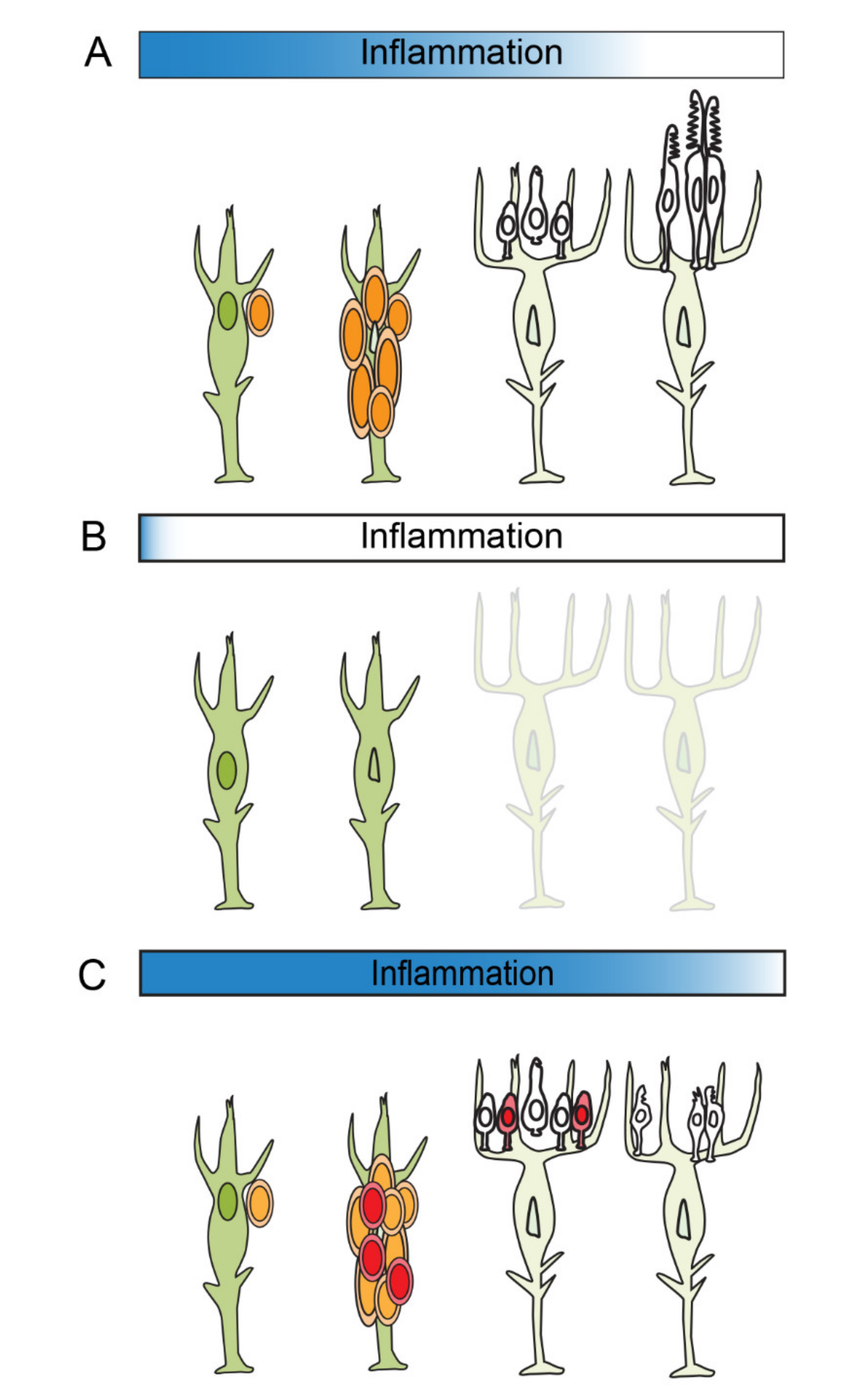

4. Quiescence, Reprogramming and Proliferation in Müller Glia

5. Inflammation and the Amplification of Müller Glia-Derived Progenitors

6. The Resolution of Inflammation

7. Summary and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lee, J.; Sayed, N.; Hunter, A.; Au, K.F.; Wong, W.H.; Mocarski, E.S.; Pera, R.R.; Yakubov, E.; Cooke, J.P. Activation of innate immunity is required for efficient nuclear reprogramming. Cell 2012, 151, 547–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cooke, J.P. Inflammation and Its Role in Regeneration and Repair. Circ. Res. 2019, 124, 1166–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aurora, A.B.; Olson, E.N. Immune Modulation of Stem Cells and Regeneration. Cell Stem Cell 2014, 15, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Michael, S.; Achilleos, C.; Panayiotou, T.; Strati, K. Inflammation Shapes Stem Cells and Stemness during Infection and Beyond. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2016, 4, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kyritsis, N.; Kizil, C.; Zocher, S.; Kroehne, V.; Kaslin, J.; Freudenreich, D.; Iltzsche, A.; Brand, M. Acute inflammation initiates the regenerative response in the adult zebrafish brain. Science 2012, 338, 1353–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, D.T.; Sengupta, S.; Saxena, M.T.; Xu, Q.; Hanes, J.; Ding, D.; Ji, H.; Mumm, J.S. Immunomodulation-accelerated neuronal regeneration following selective rod photoreceptor cell ablation in the zebrafish retina. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E3719–E3728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Serhan, C.N.; Brain, S.D.; Buckley, C.D.; Gilroy, D.W.; Haslett, C.; O’Neill, L.A.J.; Perretti, M.; Rossi, A.G.; Wallace, J.L. Resolution of inflammation: State of the art, definitions and terms. FASEB J. 2007, 21, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Iribarne, M. Inflammation induces zebrafish regeneration. Neural Regen. Res. 2021, 16, 1693–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, T.; Liu, L.; Jiang, W.; Zhou, R. DAMP-sensing receptors in sterile inflammation and inflammatory diseases. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2020, 20, 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matzinger, P. Tolerance, Danger, and the Extended Family. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1994, 12, 991–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Land, W. Allograft injury mediated by reactive oxygen species: From conserved proteins of Drosophila to acute and chronic rejection of human transplants. Part III: Interaction of (oxidative) stress-induced heat shock proteins with toll-like receptor-bearing cells of innate immunity and its consequences for the development of acute and chronic allograft rejection. Transplant. Rev. 2003, 17, 67–86. [Google Scholar]

- Newton, K.; Dixit, V.M. Signaling in innate immunity and inflammation. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2012, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, S.; Sanjo, H.; Takeda, K.; Ninomiya-Tsuji, J.; Yamamoto, M.; Kawai, T.; Matsumoto, K.; Takeuchi, O.; Akira, S. Essential function for the kinase TAK1 in innate and adaptive immune responses. Nat. Immunol. 2005, 6, 1087–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israël, A. The IKK complex, a central regulator of NF-kappaB activation. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2010, 2, a000158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, G.Y.; Nuñez, G. Sterile inflammation: Sensing and reacting to damage. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2010, 10, 826–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, C.; Sano, Y.; Todorova, K.; Carlson, B.A.; Arpa, L.; Celada, A.; Lawrence, T.; Otsu, K.; Brissette, J.L.; Arthur, J.S.C.; et al. The kinase p38α serves cell type–specific inflammatory functions in skin injury and coordinates pro- and anti-inflammatory gene expression. Nat. Immunol. 2008, 9, 1019–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, W.-H.; Grégori, G.; Hullinger, R.L.; Andrisani, O.M. Sustained Activation of p38 Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase and c-Jun N-Terminal Kinase Pathways by Hepatitis B Virus X Protein Mediates Apoptosis via Induction of Fas/FasL and Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF) Receptor 1/TNF-α Expression. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004, 24, 10352–10365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dinarello, C.A. Historical insights into cytokines. Eur. J. Immunol. 2007, 37 (Suppl. S1), S34–S45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, J.-M.; An, J. Cytokines, inflammation, and pain. Int. Anesth. Clin. 2007, 45, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gouwy, M.; Struyf, S.; Proost, P.; Van Damme, J. Synergy in cytokine and chemokine networks amplifies the inflammatory response. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2005, 16, 561–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzio, M.; Ni, J.; Feng, P.; Dixit, V.M. IRAK (Pelle) family member IRAK-2 and MyD88 as proximal mediators of IL-1 signaling. Science 1997, 278, 1612–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peschon, J.J.; Torrance, D.S.; Stocking, K.L.; Glaccum, M.B.; Otten, C.; Willis, C.R.; Charrier, K.; Morrissey, P.J.; Ware, C.B.; Mohler, K.M. TNF receptor-deficient mice reveal divergent roles for p55 and p75 in several models of inflammation. J. Immunol. 1998, 160, 943–952. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rawlings, J.S.; Rosler, K.M.; Harrison, D.A. The JAK/STAT signaling pathway. J. Cell Sci. 2004, 117, 1281–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Leonard, W.J.; Lin, J.X. Cytokine receptor signaling pathways. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2000, 105, 877–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Von der Thüsen, J.H.; Kuiper, J.; van Berkel, T.J.C.; Biessen, E.A.L. Interleukins in atherosclerosis: Molecular pathways and therapeutic potential. Pharm. Rev. 2003, 55, 133–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Seif, F.; Khoshmirsafa, M.; Aazami, H.; Mohsenzadegan, M.; Sedighi, G.; Bahar, M. The role of JAK-STAT signaling pathway and its regulators in the fate of T helper cells. Cell Commun. Signal. 2017, 15, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Turner, M.D.; Nedjai, B.; Hurst, T.; Pennington, D.J. Cytokines and chemokines: At the crossroads of cell signalling and inflammatory disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2014, 1843, 2563–2582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hitchcock, P.; Ochocinska, M.; Sieh, A.; Otteson, D. Persistent and injury-induced neurogenesis in the vertebrate retina. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2004, 23, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otteson, D.C.; Hitchcock, P.F. Stem cells in the teleost retina: Persistent neurogenesis and injury-induced regeneration. Vis. Res. 2003, 43, 927–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hitchcock, P.F.; Raymond, P.A. Retinal regeneration. Trends Neurosci. 1992, 15, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Harris, W.A.; Perron, M. Molecular recapitulation: The growth of the vertebrate retina. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 1998, 42, 299–304. [Google Scholar]

- Cerveny, K.L.; Varga, M.; Wilson, S.W. Continued growth and circuit building in the anamniote visual system. Dev. Neurobiol. 2012, 72, 328–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond, P.A.; Barthel, L.K.; Bernardos, R.L.; Perkowski, J.J. Molecular characterization of retinal stem cells and their niches in adult zebrafish. BMC Dev. Biol. 2006, 6, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bernardos, R.L.; Barthel, L.K.; Meyers, J.R.; Raymond, P.A. Late-stage neuronal progenitors in the retina are radial Müller glia that function as retinal stem cells. J. Neurosci. 2007, 27, 7028–7040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stenkamp, D.L. The rod photoreceptor lineage of teleost fish. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2011, 30, 395–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Raymond, P.A.; Rivlin, P.K. Germinal cells in the goldfish retina that produce rod photoreceptors. Dev. Biol. 1987, 122, 120–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Otteson, D.C.; Cirenza, P.F.; Hitchcock, P.F. Persistent neurogenesis in the teleost retina: Evidence for regulation by the growth-hormone/insulin-like growth factor-I axis. Mech. Dev. 2002, 117, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond, P.A.; Reifler, M.J.; Rivlin, P.K. Regeneration of goldfish retina: Rod precursors are a likely source of regenerated cells. J. Neurobiol. 1988, 19, 431–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fausett, B.V.; Goldman, D. A role for alpha1 tubulin-expressing Müller glia in regeneration of the injured zebrafish retina. J. Neurosci. 2006, 26, 6303–6313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nelson, C.M.; Hyde, D.R. Müller glia as a source of neuronal progenitor cells to regenerate the damaged zebrafish retina. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2012, 723, 425–430. [Google Scholar]

- Otteson, D.C.; D’Costa, A.R.; Hitchcock, P.F. Putative stem cells and the lineage of rod photoreceptors in the mature retina of the goldfish. Dev. Biol. 2001, 232, 62–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nagashima, M.; Barthel, L.K.; Raymond, P.A. A self-renewing division of zebrafish Müller glial cells generates neuronal progenitors that require N-cadherin to regenerate retinal neurons. Development 2013, 140, 4510–4521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Powell, C.; Cornblath, E.; Elsaeidi, F.; Wan, J.; Goldman, D. Zebrafish Müller glia-derived progenitors are multipotent, exhibit proliferative biases and regenerate excess neurons. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 24851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Silva, N.J.; Nagashima, M.; Li, J.; Kakuk-Atkins, L.; Ashrafzadeh, M.; Hyde, D.R.; Hitchcock, P.F. Inflammation and matrix metalloproteinase 9 (Mmp-9) regulate photoreceptor regeneration in adult zebrafish. Glia 2020, 68, 1445–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lahne, M.; Nagashima, M.; Hyde, D.R.; Hitchcock, P.F. Reprogramming Müller Glia to Regenerate Retinal Neurons. Annu. Rev. Vis. Sci. 2020, 6, 171–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vihtelic, T.S.; Hyde, D.R. Light-induced rod and cone cell death and regeneration in the adult albino zebrafish (Danio rerio) retina. J. Neurobiol. 2000, 44, 289–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fausett, B.V.; Gumerson, J.D.; Goldman, D. The proneural basic helix-loop-helix gene ascl1a is required for retina regeneration. J. Neurosci. 2008, 28, 1109–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fimbel, S.M.; Montgomery, J.E.; Burket, C.T.; Hyde, D.R. Regeneration of inner retinal neurons after intravitreal injection of ouabain in zebrafish. J. Neurosci. 2007, 27, 1712–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mitchell, D.M.; Lovel, A.G.; Stenkamp, D.L. Dynamic changes in microglial and macrophage characteristics during degeneration and regeneration of the zebrafish retina. J. Neuroinflamm. 2018, 15, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Ham, T.J.; Brady, C.A.; Kalicharan, R.D.; Oosterhof, N.; Kuipers, J.; Veenstra-Algra, A.; Sjollema, K.A.; Peterson, R.T.; Kampinga, H.H.; Giepmans, B.N.G. Intravital correlated microscopy reveals differential macrophage and microglial dynamics during resolution of neuroinflammation. Dis. Model. Mech. 2014, 7, 857–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Conedera, F.M.; Pousa, A.M.Q.; Mercader, N.; Tschopp, M.; Enzmann, V. Retinal microglia signaling affects Müller cell behavior in the zebrafish following laser injury induction. Glia 2019, 67, 1150–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hristovska, I.; Pascual, O. Deciphering Resting Microglial Morphology and Process Motility from a Synaptic Prospect. Front. Integr. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Silverman, S.M.; Wong, W.T. Microglia in the Retina: Roles in Development, Maturity, and Disease. Annu. Rev. Vis. Sci. 2018, 4, 45–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, S.E.L.; Calinescu, A.-A.; Hitchcock, P.F. Identification of the molecular signatures integral to regenerating photoreceptors in the retina of the zebra fish. J. Ocul. Biol. Dis. Infor. 2008, 1, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mitchell, D.M.; Sun, C.; Hunter, S.S.; New, D.D.; Stenkamp, D.L. Regeneration associated transcriptional signature of retinal microglia and macrophages. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 4768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, T.; Wang, J.; Boyd, P.; Wang, F.; Santiago, C.; Jiang, L.; Yoo, S.; Lahne, M.; Todd, L.J.; Jia, M.; et al. Gene regulatory networks controlling vertebrate retinal regeneration. Science 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourtzelis, I.; Hajishengallis, G.; Chavakis, T. Phagocytosis of Apoptotic Cells in Resolution of Inflammation. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W. Eat-me signals: Keys to molecular phagocyte biology and “Appetite” control. J. Cell. Physiol. 2012, 227, 1291–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Park, S.-Y.; Kim, I.-S. Engulfment signals and the phagocytic machinery for apoptotic cell clearance. Exp. Mol. Med. 2017, 49, e331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ravichandran, K.S.; Lorenz, U. Engulfment of apoptotic cells: Signals for a good meal. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2007, 7, 964–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blume, Z.I.; Lambert, J.M.; Lovel, A.G.; Mitchell, D.M. Microglia in the developing retina couple phagocytosis with the progression of apoptosis via P2RY12 signaling. Dev. Dyn. 2020, 249, 723–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bringmann, A.; Pannicke, T.; Grosche, J.; Francke, M.; Wiedemann, P.; Skatchkov, S.N.; Osborne, N.N.; Reichenbach, A. Müller cells in the healthy and diseased retina. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2006, 25, 397–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bringmann, A.; Iandiev, I.; Pannicke, T.; Wurm, A.; Hollborn, M.; Wiedemann, P.; Osborne, N.N.; Reichenbach, A. Cellular signaling and factors involved in Müller cell gliosis: Neuroprotective and detrimental effects. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2009, 28, 423–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsaeidi, F.; Macpherson, P.; Mills, E.A.; Jui, J.; Flannery, J.G.; Goldman, D. Notch Suppression Collaborates with Ascl1 and Lin28 to Unleash a Regenerative Response in Fish Retina, But Not in Mice. J. Neurosci. 2018, 38, 2246–2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rao, M.B.; Didiano, D.; Patton, J.G. Neurotransmitter-Regulated Regeneration in the Zebrafish Retina. Stem Cell Rep. 2017, 8, 831–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kent, M.R.; Kara, N.; Patton, J.G. Inhibition of GABA-ρ receptors induces retina regeneration in zebrafish. Neural Regen. Res. 2021, 16, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Campbell, L.J.; Hobgood, J.S.; Jia, M.; Boyd, P.; Hipp, R.I.; Hyde, D.R. Notch3 and DeltaB maintain Müller glia quiescence and act as negative regulators of regeneration in the light-damaged zebrafish retina. Glia 2021, 69, 546–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.-S.; Wan, J.; Goldman, D. Tgfb3 collaborates with PP2A and notch signaling pathways to inhibit retina regeneration. Elife 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardos, R.L.; Lentz, S.I.; Wolfe, M.S.; Raymond, P.A. Notch–Delta signaling is required for spatial patterning and Müller glia differentiation in the zebrafish retina. Dev. Biol. 2005, 278, 381–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conner, C.; Ackerman, K.M.; Lahne, M.; Hobgood, J.S.; Hyde, D.R. Repressing notch signaling and expressing TNFα are sufficient to mimic retinal regeneration by inducing Müller glial proliferation to generate committed progenitor cells. J. Neurosci. 2014, 34, 14403–14419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lenkowski, J.R.; Qin, Z.; Sifuentes, C.J.; Thummel, R.; Soto, C.M.; Moens, C.B.; Raymond, P.A. Retinal regeneration in adult zebrafish requires regulation of TGFβ signaling. Glia 2013, 61, 1687–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tappeiner, C.; Maurer, E.; Sallin, P.; Bise, T.; Enzmann, V.; Tschopp, M. Inhibition of the TGFβ Pathway Enhances Retinal Regeneration in Adult Zebrafish. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0167073. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, J.L.; Ranski, A.H.; Morgan, G.W.; Thummel, R. Reactive gliosis in the adult zebrafish retina. Exp. Eye Res. 2016, 143, 98–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Gupta, S.; Chaudhary, M.; Mitra, S.; Chawla, B.; Khursheed, M.A.; Ramachandran, R. Oct4 mediates Müller glia reprogramming and cell cycle exit during retina regeneration in zebrafish. Life Sci. Alliance 2019, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thummel, R.; Enright, J.M.; Kassen, S.C.; Montgomery, J.E.; Bailey, T.J.; Hyde, D.R. Pax6a and Pax6b are required at different points in neuronal progenitor cell proliferation during zebrafish photoreceptor regeneration. Exp. Eye Res. 2010, 90, 572–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gorsuch, R.A.; Lahne, M.; Yarka, C.E.; Petravick, M.E.; Li, J.; Hyde, D.R. Sox2 regulates Müller glia reprogramming and proliferation in the regenerating zebrafish retina via Lin28 and Ascl1a. Exp. Eye Res. 2017, 161, 174–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenkowski, J.R.; Raymond, P.A. Müller glia: Stem cells for generation and regeneration of retinal neurons in teleost fish. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2014, 40, 94–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahne, M.; Li, J.; Marton, R.M.; Hyde, D.R. Actin-Cytoskeleton- and Rock-Mediated INM Are Required for Photoreceptor Regeneration in the Adult Zebrafish Retina. J. Neurosci. 2015, 35, 15612–15634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sifuentes, C.J.; Kim, J.-W.; Swaroop, A.; Raymond, P.A. Rapid, Dynamic Activation of Müller Glial Stem Cell Responses in Zebrafish. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2016, 57, 5148–5160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, C.M.; Ackerman, K.M.; O’Hayer, P.; Bailey, T.J.; Gorsuch, R.A.; Hyde, D.R. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha is produced by dying retinal neurons and is required for Muller glia proliferation during zebrafish retinal regeneration. J. Neurosci. 2013, 33, 6524–6539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhao, X.-F.; Wan, J.; Powell, C.; Ramachandran, R.; Myers, M.G., Jr.; Goldman, D. Leptin and IL-6 family cytokines synergize to stimulate Müller glia reprogramming and retina regeneration. Cell Rep. 2014, 9, 272–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wan, J.; Zhao, X.-F.; Vojtek, A.; Goldman, D. Retinal injury, growth factors, and cytokines converge on β-catenin and pStat3 signaling to stimulate retina regeneration. Cell Rep. 2014, 9, 285–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nagashima, M.; D’Cruz, T.S.; Danku, A.E.; Hesse, D.; Sifuentes, C.; Raymond, P.A.; Hitchcock, P.F. Midkine-a Is Required for Cell Cycle Progression of Müller Glia during Neuronal Regeneration in the Vertebrate Retina. J. Neurosci. 2020, 40, 1232–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muramatsu, T. Midkine: A promising molecule for drug development to treat diseases of the central nervous system. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2011, 17, 410–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Weckbach, L.T.; Muramatsu, T.; Walzog, B. Midkine in inflammation. Sci. World J. 2011, 11, 2491–2505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, Z.; Hou, H.; Yu, S.; Zhou, C.; Zhang, X.; Li, N.; Zhang, S.; Song, K.; Lu, Y.; Liu, D.; et al. Inflammation-induced mammalian target of rapamycin signaling is essential for retina regeneration. Glia 2020, 68, 111–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Opdenakker, G.; Masure, S.; Proost, P.; Billiau, A.; van Damme, J. Natural human monocyte gelatinase and its inhibitor. FEBS Lett. 1991, 284, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Masure, S.; Proost, P.; Van Damme, J.; Opdenakker, G. Purification and identification of 91-kDa neutrophil gelatinase. Release by the activating peptide interleukin-8. Eur. J. Biochem. 1991, 198, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parks, W.C.; Wilson, C.L.; López-Boado, Y.S. Matrix metalloproteinases as modulators of inflammation and innate immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2004, 4, 617–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurco, P.; Cameron, D.A. Responses of Müller glia to retinal injury in adult zebrafish. Vis. Res. 2005, 45, 991–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Montgomery, J.E.; Parsons, M.J.; Hyde, D.R. A novel model of retinal ablation demonstrates that the extent of rod cell death regulates the origin of the regenerated zebrafish rod photoreceptors. J. Comp. Neurol. 2010, 518, 800–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Buckley, C.D.; Gilroy, D.W.; Serhan, C.N.; Stockinger, B.; Tak, P.P. The resolution of inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2013, 13, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fullerton, J.N.; Gilroy, D.W. Resolution of inflammation: A new therapeutic frontier. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2016, 15, 551–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugimoto, M.A.; Sousa, L.P.; Pinho, V.; Perretti, M.; Teixeira, M.M. Resolution of Inflammation: What Controls Its Onset? Front. Immunol. 2016, 7, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Oishi, Y.; Manabe, I. Macrophages in inflammation, repair and regeneration. Int. Immunol. 2018, 30, 511–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadok, V.A.; Bratton, D.L.; Konowal, A.; Freed, P.W.; Westcott, J.Y.; Henson, P.M. Macrophages that have ingested apoptotic cells in vitro inhibit proinflammatory cytokine production through autocrine/paracrine mechanisms involving TGF-beta, PGE2, and PAF. J. Clin. Investig. 1998, 101, 890–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Szondy, Z.; Sarang, Z.; Kiss, B.; Garabuczi, É.; Köröskényi, K. Anti-inflammatory Mechanisms Triggered by Apoptotic Cells during Their Clearance. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cvetanovic, M.; Ucker, D.S. Innate immune discrimination of apoptotic cells: Repression of proinflammatory macrophage transcription is coupled directly to specific recognition. J. Immunol. 2004, 172, 880–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Erwig, L.-P.; Henson, P.M. Clearance of apoptotic cells by phagocytes. Cell Death Differ. 2008, 15, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doran, A.C.; Yurdagul, A., Jr.; Tabas, I. Efferocytosis in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2020, 20, 254–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackshaw, S.; Harpavat, S.; Trimarchi, J.; Cai, L.; Huang, H.; Kuo, W.P.; Weber, G.; Lee, K.; Fraioli, R.E.; Cho, S.-H.; et al. Genomic analysis of mouse retinal development. PLoS Biol. 2004, 2, E247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jadhav, A.P.; Roesch, K.; Cepko, C.L. Development and neurogenic potential of Müller glial cells in the vertebrate retina. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2009, 28, 249–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ueki, Y.; Wilken, M.S.; Cox, K.E.; Chipman, L.; Jorstad, N.; Sternhagen, K.; Simic, M.; Ullom, K.; Nakafuku, M.; Reh, T.A. Transgenic expression of the proneural transcription factor Ascl1 in Müller glia stimulates retinal regeneration in young mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 13717–13722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- VandenBosch, L.S.; Wohl, S.G.; Wilken, M.S.; Hooper, M.; Finkbeiner, C.; Cox, K.; Chipman, L.; Reh, T.A. Developmental changes in the accessible chromatin, transcriptome and Ascl1-binding correlate with the loss in Müller Glial regenerative potential. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 13615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorstad, N.L.; Wilken, M.S.; Grimes, W.N.; Wohl, S.G.; VandenBosch, L.S.; Yoshimatsu, T.; Wong, R.O.; Rieke, F.; Reh, T.A. Stimulation of functional neuronal regeneration from Müller glia in adult mice. Nature 2017, 548, 103–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todd, L.; Finkbeiner, C.; Wong, C.K.; Hooper, M.J.; Reh, T.A. Microglia Suppress Ascl1-Induced Retinal Regeneration in Mice. Cell Rep. 2020, 33, 108507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallina, D.; Todd, L.; Fischer, A.J. A comparative analysis of Müller glia-mediated regeneration in the vertebrate retina. Exp. Eye Res. 2014, 123, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Silverman, S.M.; Zhao, L.; Villasmil, R.; Campos, M.M.; Amaral, J.; Wong, W.T. Absence of TGFβ signaling in retinal microglia induces retinal degeneration and exacerbates choroidal neovascularization. Elife 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palazzo, I.; Deistler, K.; Hoang, T.V.; Blackshaw, S.; Fischer, A.J. NF-κB signaling regulates the formation of proliferating Müller glia-derived progenitor cells in the avian retina. Development 2020, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, S.P.; Sheng, D.Z.; Sugimoto, K.; Gonzalez-Rajal, A.; Nakagawa, S.; Hesselson, D.; Kikuchi, K. Zebrafish Regulatory T Cells Mediate Organ-Specific Regenerative Programs. Dev. Cell 2017, 43, 659–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Josefowicz, S.Z.; Lu, L.-F.; Rudensky, A.Y. Regulatory T Cells: Mechanisms of Differentiation and Function. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2012, 30, 531–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakaguchi, S.; Miyara, M.; Costantino, C.M.; Hafler, D.A. FOXP3 regulatory T cells in the human immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2010, 10, 490–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesaresi, M.; Bonilla-Pons, S.A.; Simonte, G.; Sanges, D.; Di Vicino, U.; Cosma, M.P. Endogenous Mobilization of Bone-Marrow Cells Into the Murine Retina Induces Fusion-Mediated Reprogramming of Müller Glia Cells. EBioMedicine 2018, 30, 38–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Abler, A.S.; Chang, C.J.; Ful, J.; Tso, M.O.; Lam, T.T. Photic injury triggers apoptosis of photoreceptor cells. Res. Commun. Mol. Pathol. Pharm. 1996, 92, 177–189. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, A.Y.; Wei, L.; Xia, S.; Rothman, S.; Yu, S.P. Ionic mechanism of ouabain-induced concurrent apoptosis and necrosis in individual cultured cortical neurons. J. Neurosci. 2002, 22, 1350–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Topcu, S.O.; Celik, S.; Erturhan, S.; Erbagci, A.; Yagci, F.; Ucak, R. Verapamil prevents the apoptotic and hemodynamic changes in response to unilateral ureteral obstruction. Int. J. Urol. 2008, 15, 350–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markiewski, M.M.; Lambris, J.D. The role of complement in inflammatory diseases from behind the scenes into the spotlight. Am. J. Pathol. 2007, 171, 715–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Serhan, C.N.; Chiang, N.; Van Dyke, T.E. Resolving inflammation: Dual anti-inflammatory and pro-resolution lipid mediators. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2008, 8, 349–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Branco, A.C.C.C.; Yoshikawa, F.S.Y.; Pietrobon, A.J.; Sato, M.N. Role of Histamine in Modulating the Immune Response and Inflammation. Mediators Inflamm. 2018, 2018, 9524075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nagashima, M.; Hitchcock, P.F. Inflammation Regulates the Multi-Step Process of Retinal Regeneration in Zebrafish. Cells 2021, 10, 783. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells10040783

Nagashima M, Hitchcock PF. Inflammation Regulates the Multi-Step Process of Retinal Regeneration in Zebrafish. Cells. 2021; 10(4):783. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells10040783

Chicago/Turabian StyleNagashima, Mikiko, and Peter F. Hitchcock. 2021. "Inflammation Regulates the Multi-Step Process of Retinal Regeneration in Zebrafish" Cells 10, no. 4: 783. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells10040783

APA StyleNagashima, M., & Hitchcock, P. F. (2021). Inflammation Regulates the Multi-Step Process of Retinal Regeneration in Zebrafish. Cells, 10(4), 783. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells10040783