Role of Extracellular Vesicle-Based Cell-to-Cell Communication in Multiple Myeloma Progression

Abstract

:1. Introduction

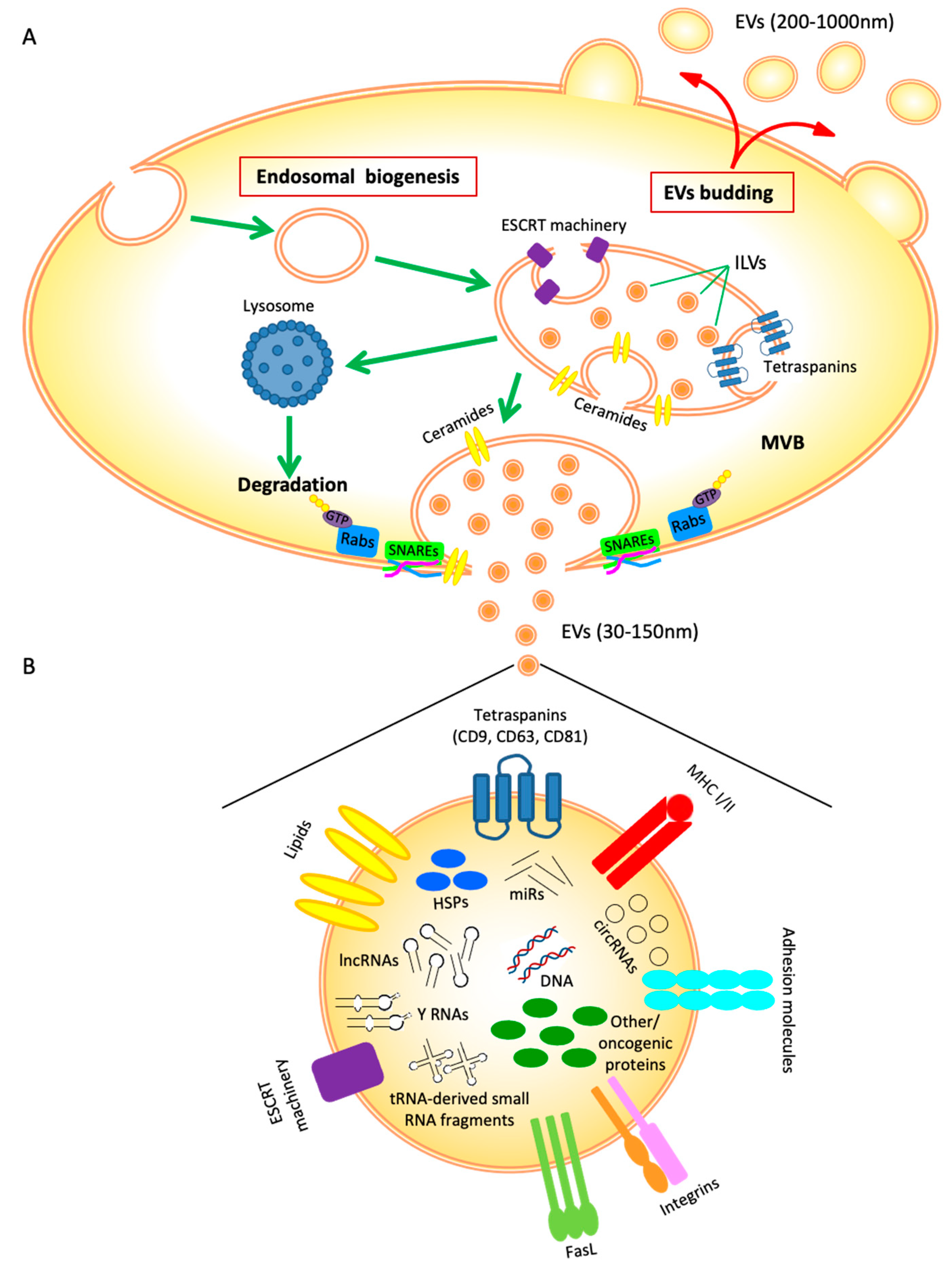

2. EVs Biogenesis

3. EVs Cargo

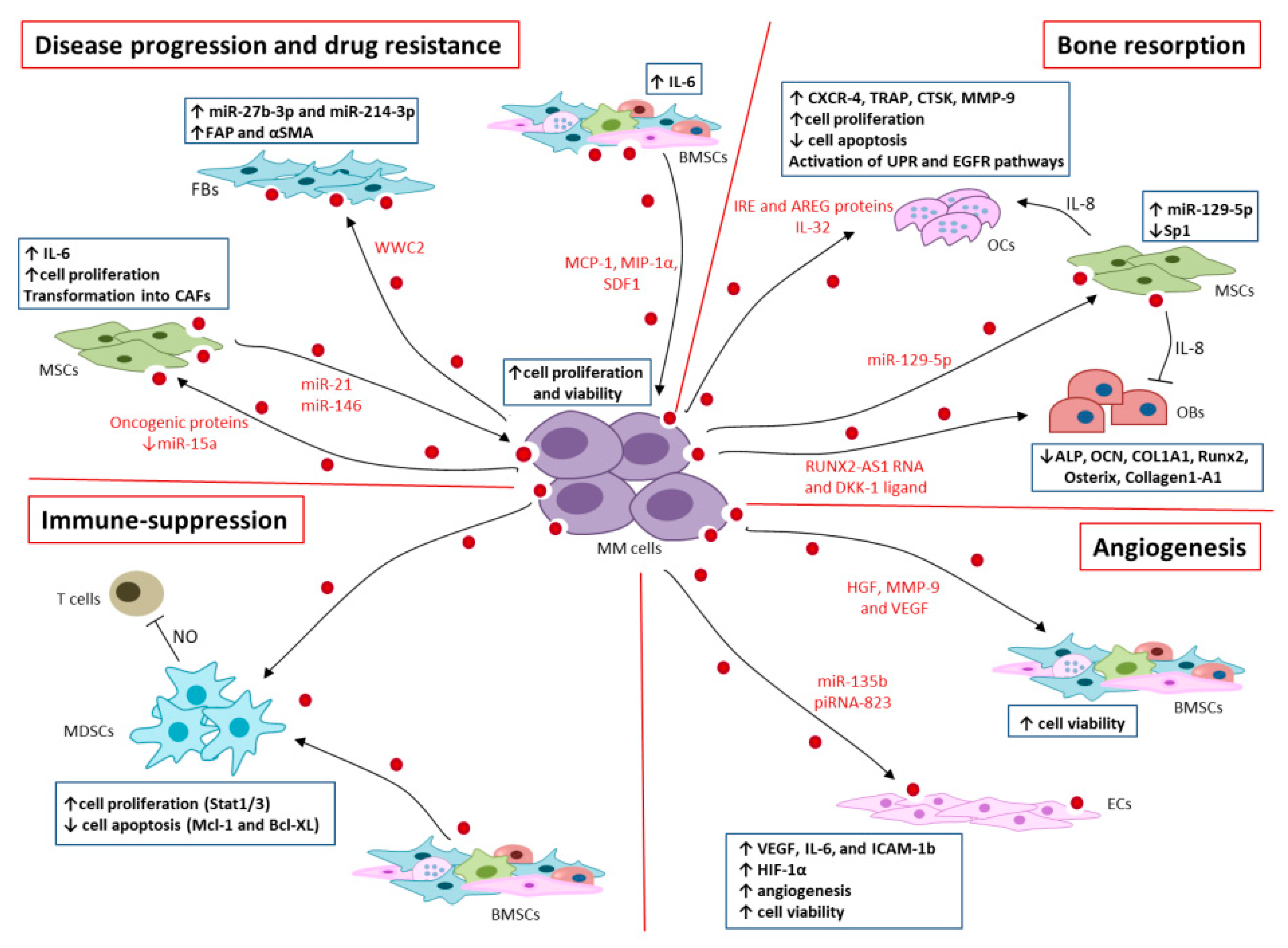

4. EVs in MM Progression and Drug Resistance

5. EVs in MM Bone Resorption

6. EVs in Immunosuppression

7. EVs in Angiogenesis

8. Diagnostic Potential of EVs

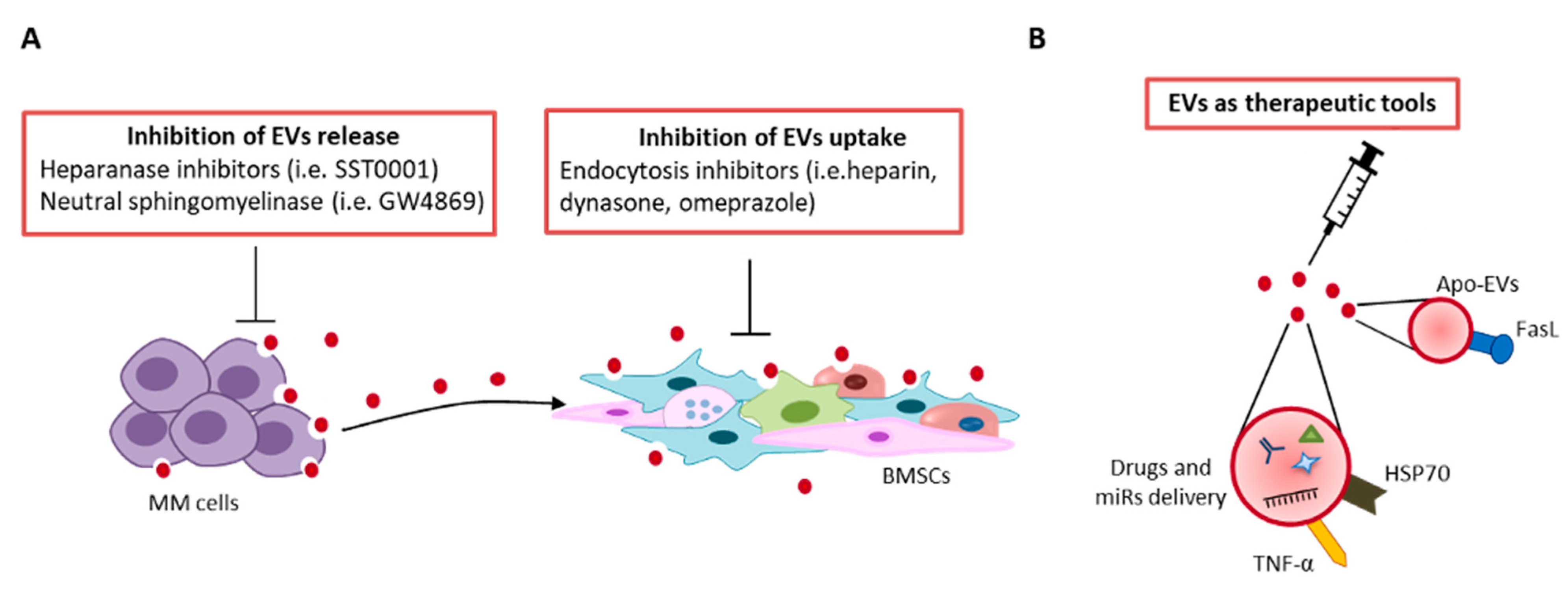

9. Therapeutic Perspective

10. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Korde, N.; Kristinsson, S.Y.; Landgren, O. Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) and smoldering multiple myeloma (SMM): Novel biological insights and development of early treatment strategies. Blood 2011, 117, 5573–5581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Di Marzo, L.; Desantis, V.; Solimando, A.G.; Ruggieri, S.; Annese, T.; Nico, B.; Fumarulo, R.; Vacca, A.; Frassanito, M.A. Microenvironment drug resistance in multiple myeloma: Emerging new players. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 60698–60711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brinton, L.T.; Sloane, H.S.; Kester, M.; Kelly, K.A. Formation and role of exosomes in cancer. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2015, 72, 659–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Thery, C.; Ostrowski, M.; Segura, E. Membrane vesicles as conveyors of immune responses. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2009, 9, 581–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thery, C.; Witwer, K.W.; Aikawa, E.; Alcaraz, M.J.; Anderson, J.D.; Andriantsitohaina, R.; Antoniou, A.; Arab, T.; Archer, F.; Atkin-Smith, G.K.; et al. Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles 2018 (MISEV2018): A position statement of the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles and update of the MISEV2014 guidelines. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2018, 7, 1535750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Johnstone, R.M.; Adam, M.; Hammond, J.R.; Orr, L.; Turbide, C. Vesicle formation during reticulocyte maturation. Association of plasma membrane activities with released vesicles (exosomes). J. Biol. Chem. 1987, 262, 9412–9420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peinado, H.; Aleckovic, M.; Lavotshkin, S.; Matei, I.; Costa-Silva, B.; Moreno-Bueno, G.; Hergueta-Redondo, M.; Williams, C.; Garcia-Santos, G.; Ghajar, C.; et al. Melanoma exosomes educate bone marrow progenitor cells toward a pro-metastatic phenotype through MET. Nat. Med. 2012, 18, 883–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Whiteside, T.L. Tumor-Derived Exosomes and Their Role in Cancer Progression. Adv. Clin. Chem. 2016, 74, 103–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Larssen, P.; Wik, L.; Czarnewski, P.; Eldh, M.; Lof, L.; Ronquist, K.G.; Dubois, L.; Freyhult, E.; Gallant, C.J.; Oelrich, J.; et al. Tracing Cellular Origin of Human Exosomes Using Multiplex Proximity Extension Assays. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2017, 16, 502–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yu, X.; Harris, S.L.; Levine, A.J. The regulation of exosome secretion: A novel function of the p53 protein. Cancer Res. 2006, 66, 4795–4801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ostrowski, M.; Carmo, N.B.; Krumeich, S.; Fanget, I.; Raposo, G.; Savina, A.; Moita, C.F.; Schauer, K.; Hume, A.N.; Freitas, R.P.; et al. Rab27a and Rab27b control different steps of the exosome secretion pathway. Nat. Cell. Biol. 2010, 12, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bebelman, M.P.; Smit, M.J.; Pegtel, D.M.; Baglio, S.R. Biogenesis and function of extracellular vesicles in cancer. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018, 188, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowal, J.; Tkach, M.; Thery, C. Biogenesis and secretion of exosomes. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2014, 29, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- White, I.J.; Bailey, L.M.; Aghakhani, M.R.; Moss, S.E.; Futter, C.E. EGF stimulates annexin 1-dependent inward vesiculation in a multivesicular endosome subpopulation. EMBO J. 2006, 25, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lachenal, G.; Pernet-Gallay, K.; Chivet, M.; Hemming, F.J.; Belly, A.; Bodon, G.; Blot, B.; Haase, G.; Goldberg, Y.; Sadoul, R. Release of exosomes from differentiated neurons and its regulation by synaptic glutamatergic activity. Mol. Cell Neurosci. 2011, 46, 409–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Andreu, Z.; Yanez-Mo, M. Tetraspanins in extracellular vesicle formation and function. Front. Immunol. 2014, 5, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, H.; Tang, W.H. Exosomes: Biogenesis, biologic function and clinical potential. Cell Biosci. 2019, 9, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colombo, M.; Moita, C.; van Niel, G.; Kowal, J.; Vigneron, J.; Benaroch, P.; Manel, N.; Moita, L.F.; Thery, C.; Raposo, G. Analysis of ESCRT functions in exosome biogenesis, composition and secretion highlights the heterogeneity of extracellular vesicles. J. Cell Sci. 2013, 126, 5553–5565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Henne, W.M.; Buchkovich, N.J.; Emr, S.D. The ESCRT pathway. Dev. Cell 2011, 21, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vietri, M.; Radulovic, M.; Stenmark, H. The many functions of ESCRTs. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2020, 21, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villarroya-Beltri, C.; Baixauli, F.; Gutierrez-Vazquez, C.; Sanchez-Madrid, F.; Mittelbrunn, M. Sorting it out: Regulation of exosome loading. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2014, 28, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ghossoub, R.; Lembo, F.; Rubio, A.; Gaillard, C.B.; Bouchet, J.; Vitale, N.; Slavik, J.; Machala, M.; Zimmermann, P. Syntenin-ALIX exosome biogenesis and budding into multivesicular bodies are controlled by ARF6 and PLD2. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 3477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Perez-Hernandez, D.; Gutierrez-Vazquez, C.; Jorge, I.; Lopez-Martin, S.; Ursa, A.; Sanchez-Madrid, F.; Vazquez, J.; Yanez-Mo, M. The intracellular interactome of tetraspanin-enriched microdomains reveals their function as sorting machineries toward exosomes. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 11649–11661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Trajkovic, K.; Hsu, C.; Chiantia, S.; Rajendran, L.; Wenzel, D.; Wieland, F.; Schwille, P.; Brugger, B.; Simons, M. Ceramide triggers budding of exosome vesicles into multivesicular endosomes. Science 2008, 319, 1244–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riches, A.; Campbell, E.; Borger, E.; Powis, S. Regulation of exosome release from mammary epithelial and breast cancer cells—A new regulatory pathway. Eur. J. Cancer 2014, 50, 1025–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenmark, H. Rab GTPases as coordinators of vesicle traffic. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009, 10, 513–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Y.; Wang, D.; Jin, F.; Bian, Z.; Li, L.; Liang, H.; Li, M.; Shi, L.; Pan, C.; Zhu, D.; et al. Pyruvate kinase type M2 promotes tumour cell exosome release via phosphorylating synaptosome-associated protein 23. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 14041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Han, J.; Pluhackova, K.; Bockmann, R.A. The Multifaceted Role of SNARE Proteins in Membrane Fusion. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hoshino, D.; Kirkbride, K.C.; Costello, K.; Clark, E.S.; Sinha, S.; Grega-Larson, N.; Tyska, M.J.; Weaver, A.M. Exosome secretion is enhanced by invadopodia and drives invasive behavior. Cell Rep. 2013, 5, 1159–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Isaac, R.; Reis, F.C.G.; Ying, W.; Olefsky, J.M. Exosomes as mediators of intercellular crosstalk in metabolism. Cell Metab. 2021, 33, 1744–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitzner, D.; Schnaars, M.; van Rossum, D.; Krishnamoorthy, G.; Dibaj, P.; Bakhti, M.; Regen, T.; Hanisch, U.K.; Simons, M. Selective transfer of exosomes from oligodendrocytes to microglia by macropinocytosis. J. Cell Sci. 2011, 124, 447–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Feng, D.; Zhao, W.L.; Ye, Y.Y.; Bai, X.C.; Liu, R.Q.; Chang, L.F.; Zhou, Q.; Sui, S.F. Cellular internalization of exosomes occurs through phagocytosis. Traffic 2010, 11, 675–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, T.; Zhu, Y.L.; Zhou, Y.Y.; Liang, G.F.; Wang, Y.Y.; Hu, F.H.; Xiao, Z.D. Exosome uptake through clathrin-mediated endocytosis and macropinocytosis and mediating miR-21 delivery. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 22258–22267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Svensson, K.J.; Christianson, H.C.; Wittrup, A.; Bourseau-Guilmain, E.; Lindqvist, E.; Svensson, L.M.; Morgelin, M.; Belting, M. Exosome uptake depends on ERK1/2-heat shock protein 27 signaling and lipid Raft-mediated endocytosis negatively regulated by caveolin-1. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 17713–17724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hoshino, A.; Costa-Silva, B.; Shen, T.L.; Rodrigues, G.; Hashimoto, A.; Tesic Mark, M.; Molina, H.; Kohsaka, S.; Di Giannatale, A.; Ceder, S.; et al. Tumour exosome integrins determine organotropic metastasis. Nature 2015, 527, 329–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Toda, Y.; Takata, K.; Nakagawa, Y.; Kawakami, H.; Fujioka, S.; Kobayashi, K.; Hattori, Y.; Kitamura, Y.; Akaji, K.; Ashihara, E. Effective internalization of U251-MG-secreted exosomes into cancer cells and characterization of their lipid components. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015, 456, 768–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Munich, S.; Sobo-Vujanovic, A.; Buchser, W.J.; Beer-Stolz, D.; Vujanovic, N.L. Dendritic cell exosomes directly kill tumor cells and activate natural killer cells via TNF superfamily ligands. Oncoimmunology 2012, 1, 1074–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tkach, M.; Kowal, J.; Zucchetti, A.E.; Enserink, L.; Jouve, M.; Lankar, D.; Saitakis, M.; Martin-Jaular, L.; Thery, C. Qualitative differences in T-cell activation by dendritic cell-derived extracellular vesicle subtypes. EMBO J. 2017, 36, 3012–3028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, D.S.; Kim, D.K.; Kim, Y.K.; Gho, Y.S. Proteomics of extracellular vesicles: Exosomes and ectosomes. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 2015, 34, 474–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimaoka, M.; Kawamoto, E.; Gaowa, A.; Okamoto, T.; Park, E.J. Connexins and Integrins in Exosomes. Cancers 2019, 11, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Runz, S.; Keller, S.; Rupp, C.; Stoeck, A.; Issa, Y.; Koensgen, D.; Mustea, A.; Sehouli, J.; Kristiansen, G.; Altevogt, P. Malignant ascites-derived exosomes of ovarian carcinoma patients contain CD24 and EpCAM. Gynecol. Oncol. 2007, 107, 563–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyciszkiewicz, A.; Kalinowska-Lyszczarz, A.; Nowakowski, B.; Kazmierczak, K.; Osztynowicz, K.; Michalak, S. Expression of small heat shock proteins in exosomes from patients with gynecologic cancers. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 9817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ciravolo, V.; Huber, V.; Ghedini, G.C.; Venturelli, E.; Bianchi, F.; Campiglio, M.; Morelli, D.; Villa, A.; Della Mina, P.; Menard, S.; et al. Potential role of HER2-overexpressing exosomes in countering trastuzumab-based therapy. J. Cell Physiol. 2012, 227, 658–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxevanis, C.N.; Anastasopoulou, E.A.; Voutsas, I.F.; Papamichail, M.; Perez, S.A. Immune biomarkers: How well do they serve prognosis in human cancers? Expert. Rev. Mol. Diagn. 2015, 15, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieckowski, E.U.; Visus, C.; Szajnik, M.; Szczepanski, M.J.; Storkus, W.J.; Whiteside, T.L. Tumor-derived microvesicles promote regulatory T cell expansion and induce apoptosis in tumor-reactive activated CD8+ T lymphocytes. J. Immunol. 2009, 183, 3720–3730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Buzas, E.I.; Toth, E.A.; Sodar, B.W.; Szabo-Taylor, K.E. Molecular interactions at the surface of extracellular vesicles. Semin. Immunopathol. 2018, 40, 453–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Baranyai, T.; Herczeg, K.; Onodi, Z.; Voszka, I.; Modos, K.; Marton, N.; Nagy, G.; Mager, I.; Wood, M.J.; El Andaloussi, S.; et al. Isolation of Exosomes from Blood Plasma: Qualitative and Quantitative Comparison of Ultracentrifugation and Size Exclusion Chromatography Methods. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0145686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gyorgy, B.; Szabo, T.G.; Turiak, L.; Wright, M.; Herczeg, P.; Ledeczi, Z.; Kittel, A.; Polgar, A.; Toth, K.; Derfalvi, B.; et al. Improved flow cytometric assessment reveals distinct microvesicle (cell-derived microparticle) signatures in joint diseases. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e49726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, N.; Cvjetkovic, A.; Jang, S.C.; Crescitelli, R.; Hosseinpour Feizi, M.A.; Nieuwland, R.; Lotvall, J.; Lasser, C. Detailed analysis of the plasma extracellular vesicle proteome after separation from lipoproteins. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2018, 75, 2873–2886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Onodi, Z.; Pelyhe, C.; Terezia Nagy, C.; Brenner, G.B.; Almasi, L.; Kittel, A.; Mancek-Keber, M.; Ferdinandy, P.; Buzas, E.I.; Giricz, Z. Isolation of High-Purity Extracellular Vesicles by the Combination of Iodixanol Density Gradient Ultracentrifugation and Bind-Elute Chromatography From Blood Plasma. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Toth, E.A.; Turiak, L.; Visnovitz, T.; Cserep, C.; Mazlo, A.; Sodar, B.W.; Forsonits, A.I.; Petovari, G.; Sebestyen, A.; Komlosi, Z.; et al. Formation of a protein corona on the surface of extracellular vesicles in blood plasma. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2021, 10, e12140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palviainen, M.; Saraswat, M.; Varga, Z.; Kitka, D.; Neuvonen, M.; Puhka, M.; Joenvaara, S.; Renkonen, R.; Nieuwland, R.; Takatalo, M.; et al. Extracellular vesicles from human plasma and serum are carriers of extravesicular cargo-Implications for biomarker discovery. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0236439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gusachenko, O.N.; Zenkova, M.A.; Vlassov, V.V. Nucleic acids in exosomes: Disease markers and intercellular communication molecules. Biochemistry 2013, 78, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balaj, L.; Lessard, R.; Dai, L.; Cho, Y.J.; Pomeroy, S.L.; Breakefield, X.O.; Skog, J. Tumour microvesicles contain retrotransposon elements and amplified oncogene sequences. Nat. Commun. 2011, 2, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, T.H.; Chennakrishnaiah, S.; Audemard, E.; Montermini, L.; Meehan, B.; Rak, J. Oncogenic ras-driven cancer cell vesiculation leads to emission of double-stranded DNA capable of interacting with target cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2014, 451, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kahlert, C.; Melo, S.A.; Protopopov, A.; Tang, J.; Seth, S.; Koch, M.; Zhang, J.; Weitz, J.; Chin, L.; Futreal, A.; et al. Identification of double-stranded genomic DNA spanning all chromosomes with mutated KRAS and p53 DNA in the serum exosomes of patients with pancreatic cancer. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 3869–3875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Veziroglu, E.M.; Mias, G.I. Characterizing Extracellular Vesicles and Their Diverse RNA Contents. Front. Genet. 2020, 11, 700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Nedawi, K.; Meehan, B.; Micallef, J.; Lhotak, V.; May, L.; Guha, A.; Rak, J. Intercellular transfer of the oncogenic receptor EGFRvIII by microvesicles derived from tumour cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 2008, 10, 619–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, Y.; Kamohara, H.; Kinoshita, K.; Kurashige, J.; Ishimoto, T.; Iwatsuki, M.; Watanabe, M.; Baba, H. Clinical impact of serum exosomal microRNA-21 as a clinical biomarker in human esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer 2013, 119, 1159–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conigliaro, A.; Costa, V.; Lo Dico, A.; Saieva, L.; Buccheri, S.; Dieli, F.; Manno, M.; Raccosta, S.; Mancone, C.; Tripodi, M.; et al. CD90+ liver cancer cells modulate endothelial cell phenotype through the release of exosomes containing H19 lncRNA. Mol. Cancer 2015, 14, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, Z.; Jiang, P.; Peng, M.; Zhang, X.; Chen, K.; Liu, H.; Bi, H.; Liu, X.; Li, X. Circular RNA IARS (circ-IARS) secreted by pancreatic cancer cells and located within exosomes regulates endothelial monolayer permeability to promote tumor metastasis. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 37, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Manier, S.; Liu, C.J.; Avet-Loiseau, H.; Park, J.; Shi, J.; Campigotto, F.; Salem, K.Z.; Huynh, D.; Glavey, S.V.; Rivotto, B.; et al. Prognostic role of circulating exosomal miRNAs in multiple myeloma. Blood 2017, 129, 2429–2436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.Y.; Li, Y.C.; Geng, C.Y.; Zhou, H.X.; Gao, W.; Chen, W.M. Serum exosomal microRNAs as novel biomarkers for multiple myeloma. Hematol. Oncol. 2019, 37, 409–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, D.D.; Gercel-Taylor, C. MicroRNA signatures of tumor-derived exosomes as diagnostic biomarkers of ovarian cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 2008, 110, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manier, S.; Sacco, A.; Leleu, X.; Ghobrial, I.M.; Roccaro, A.M. Bone marrow microenvironment in multiple myeloma progression. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2012, 2012, 157496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frassanito, M.A.; Rao, L.; Moschetta, M.; Ria, R.; Di Marzo, L.; De Luisi, A.; Racanelli, V.; Catacchio, I.; Berardi, S.; Basile, A.; et al. Bone marrow fibroblasts parallel multiple myeloma progression in patients and mice: In vitro and in vivo studies. Leukemia 2014, 28, 904–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Frassanito, M.A.; De Veirman, K.; Desantis, V.; Di Marzo, L.; Vergara, D.; Ruggieri, S.; Annese, T.; Nico, B.; Menu, E.; Catacchio, I.; et al. Halting pro-survival autophagy by TGFbeta inhibition in bone marrow fibroblasts overcomes bortezomib resistance in multiple myeloma patients. Leukemia 2016, 30, 640–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frassanito, M.A.; Desantis, V.; Di Marzo, L.; Craparotta, I.; Beltrame, L.; Marchini, S.; Annese, T.; Visino, F.; Arciuli, M.; Saltarella, I.; et al. Bone marrow fibroblasts overexpress miR-27b and miR-214 in step with multiple myeloma progression, dependent on tumour cell-derived exosomes. J. Pathol. 2019, 247, 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Q.; Li, X.; Liu, J.; Ye, Q.; Chen, Y.; Tan, S.; Liu, J. Multiple Myeloma-Derived Exosomes Regulate the Functions of Mesenchymal Stem Cells Partially via Modulating miR-21 and miR-146a. Stem Cells Int. 2017, 2017, 9012152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Liu, H.; Li, Y.; Shao, Q.; Chen, J.; Song, J.; Fu, R. Multiple myeloma-derived exosomes inhibit osteoblastic differentiation and improve IL-6 secretion of BMSCs from multiple myeloma. J. Investig. Med. 2020, 68, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reale, A.; Carmichael, I.; Xu, R.; Mithraprabhu, S.; Khong, T.; Chen, M.; Fang, H.; Savvidou, I.; Ramachandran, M.; Bingham, N.; et al. Human myeloma cell- and plasma-derived extracellular vesicles contribute to functional regulation of stromal cells. Proteomics 2021, 21, e2000119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dabbah, M.; Attar-Schneider, O.; Tartakover Matalon, S.; Shefler, I.; Jarchwsky Dolberg, O.; Lishner, M.; Drucker, L. Microvesicles derived from normal and multiple myeloma bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells differentially modulate myeloma cells’ phenotype and translation initiation. Carcinogenesis 2017, 38, 708–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Watanabe, T. Realization of Osteolysis, Angiogenesis, Immunosuppression, and Drug Resistance by Extracellular Vesicles: Roles of RNAs and Proteins in Their Cargoes and of Ectonucleotidases of the Immunosuppressive Adenosinergic Noncanonical Pathway in the Bone Marrow Niche of Multiple Myeloma. Cancers 2021, 13, 2969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roccaro, A.M.; Sacco, A.; Maiso, P.; Azab, A.K.; Tai, Y.T.; Reagan, M.; Azab, F.; Flores, L.M.; Campigotto, F.; Weller, E.; et al. BM mesenchymal stromal cell-derived exosomes facilitate multiple myeloma progression. J. Clin. Investig. 2013, 123, 1542–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dabbah, M.; Lishner, M.; Jarchowsky-Dolberg, O.; Tartakover-Matalon, S.; Brin, Y.S.; Pasmanik-Chor, M.; Neumann, A.; Drucker, L. Ribosomal proteins as distinct “passengers” of microvesicles: New semantics in myeloma and mesenchymal stem cells’ communication. Transl. Res. 2021, 236, 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Hendrix, A.; Hernot, S.; Lemaire, M.; De Bruyne, E.; Van Valckenborgh, E.; Lahoutte, T.; De Wever, O.; Vanderkerken, K.; Menu, E. Bone marrow stromal cell-derived exosomes as communicators in drug resistance in multiple myeloma cells. Blood 2014, 124, 555–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Terpos, E.; Ntanasis-Stathopoulos, I.; Gavriatopoulou, M.; Dimopoulos, M.A. Pathogenesis of bone disease in multiple myeloma: From bench to bedside. Blood Cancer J. 2018, 8, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Faict, S.; Muller, J.; De Veirman, K.; De Bruyne, E.; Maes, K.; Vrancken, L.; Heusschen, R.; De Raeve, H.; Schots, R.; Vanderkerken, K.; et al. Exosomes play a role in multiple myeloma bone disease and tumor development by targeting osteoclasts and osteoblasts. Blood Cancer J. 2018, 8, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Raimondi, L.; De Luca, A.; Amodio, N.; Manno, M.; Raccosta, S.; Taverna, S.; Bellavia, D.; Naselli, F.; Fontana, S.; Schillaci, O.; et al. Involvement of multiple myeloma cell-derived exosomes in osteoclast differentiation. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 13772–13789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Raimondi, L.; De Luca, A.; Fontana, S.; Amodio, N.; Costa, V.; Carina, V.; Bellavia, D.; Raimondo, S.; Siragusa, S.; Monteleone, F.; et al. Multiple Myeloma-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Induce Osteoclastogenesis through the Activation of the XBP1/IRE1alpha Axis. Cancers 2020, 12, 2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raimondo, S.; Saieva, L.; Vicario, E.; Pucci, M.; Toscani, D.; Manno, M.; Raccosta, S.; Giuliani, N.; Alessandro, R. Multiple myeloma-derived exosomes are enriched of amphiregulin (AREG) and activate the epidermal growth factor pathway in the bone microenvironment leading to osteoclastogenesis. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2019, 12, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zahoor, M.; Westhrin, M.; Aass, K.R.; Moen, S.H.; Misund, K.; Psonka-Antonczyk, K.M.; Giliberto, M.; Buene, G.; Sundan, A.; Waage, A.; et al. Hypoxia promotes IL-32 expression in myeloma cells, and high expression is associated with poor survival and bone loss. Blood Adv. 2017, 1, 2656–2666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Colla, S.; Morandi, F.; Lazzaretti, M.; Rizzato, R.; Lunghi, P.; Bonomini, S.; Mancini, C.; Pedrazzoni, M.; Crugnola, M.; Rizzoli, V.; et al. Human myeloma cells express the bone regulating gene Runx2/Cbfa1 and produce osteopontin that is involved in angiogenesis in multiple myeloma patients. Leukemia 2005, 19, 2166–2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Saeki, Y.; Mima, T.; Ishii, T.; Ogata, A.; Kobayashi, H.; Ohshima, S.; Ishida, T.; Tabunoki, Y.; Kitayama, H.; Mizuki, M.; et al. Enhanced production of osteopontin in multiple myeloma: Clinical and pathogenic implications. Br. J. Haematol. 2003, 123, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Xu, H.; Han, H.; Song, S.; Zhang, X.; Ouyang, L.; Qian, C.; Hong, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Zhou, W.; et al. Exosome-mediated transfer of lncRUNX2-AS1 from multiple myeloma cells to MSCs contributes to osteogenesis. Oncogene 2018, 37, 5508–5519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raimondo, S.; Urzi, O.; Conigliaro, A.; Bosco, G.L.; Parisi, S.; Carlisi, M.; Siragusa, S.; Raimondi, L.; Luca, A.; Giavaresi, G.; et al. Extracellular Vesicle microRNAs Contribute to the Osteogenic Inhibition of Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Multiple Myeloma. Cancers 2020, 12, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lopes, R.; Caetano, J.; Ferreira, B.; Barahona, F.; Carneiro, E.A.; Joao, C. The Immune Microenvironment in Multiple Myeloma: Friend or Foe? Cancers 2021, 13, 625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelle-Rieser, C.; Thangavadivel, S.; Biedermann, R.; Brunner, A.; Stoitzner, P.; Willenbacher, E.; Greil, R.; Johrer, K. T cells in multiple myeloma display features of exhaustion and senescence at the tumor site. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2016, 9, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Frassanito, M.A.; Ruggieri, S.; Desantis, V.; Di Marzo, L.; Leone, P.; Racanelli, V.; Fumarulo, R.; Dammacco, F.; Vacca, A. Myeloma cells act as tolerogenic antigen-presenting cells and induce regulatory T cells in vitro. Eur. J. Haematol. 2015, 95, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhala, R.H.; Pelluru, D.; Fulciniti, M.; Prabhala, H.K.; Nanjappa, P.; Song, W.; Pai, C.; Amin, S.; Tai, Y.T.; Richardson, P.G.; et al. Elevated IL-17 produced by TH17 cells promotes myeloma cell growth and inhibits immune function in multiple myeloma. Blood 2010, 115, 5385–5392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leone, P.; Solimando, A.G.; Malerba, E.; Fasano, R.; Buonavoglia, A.; Pappagallo, F.; De Re, V.; Argentiero, A.; Silvestris, N.; Vacca, A.; et al. Actors on the Scene: Immune Cells in the Myeloma Niche. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 599098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veglia, F.; Sanseviero, E.; Gabrilovich, D.I. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the era of increasing myeloid cell diversity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2021, 21, 485–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Favaloro, J.; Liyadipitiya, T.; Brown, R.; Yang, S.; Suen, H.; Woodland, N.; Nassif, N.; Hart, D.; Fromm, P.; Weatherburn, C.; et al. Myeloid derived suppressor cells are numerically, functionally and phenotypically different in patients with multiple myeloma. Leuk. Lymphoma 2014, 55, 2893–2900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; De Veirman, K.; De Beule, N.; Maes, K.; De Bruyne, E.; Van Valckenborgh, E.; Vanderkerken, K.; Menu, E. The bone marrow microenvironment enhances multiple myeloma progression by exosome-mediated activation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 43992–44004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wang, J.; De Veirman, K.; Faict, S.; Frassanito, M.A.; Ribatti, D.; Vacca, A.; Menu, E. Multiple myeloma exosomes establish a favourable bone marrow microenvironment with enhanced angiogenesis and immunosuppression. J. Pathol. 2016, 239, 162–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morandi, F.; Marimpietri, D.; Horenstein, A.L.; Bolzoni, M.; Toscani, D.; Costa, F.; Castella, B.; Faini, A.C.; Massaia, M.; Pistoia, V.; et al. Microvesicles released from multiple myeloma cells are equipped with ectoenzymes belonging to canonical and non-canonical adenosinergic pathways and produce adenosine from ATP and NAD(+). Oncoimmunology 2018, 7, e1458809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Saltarella, I.; Desantis, V.; Melaccio, A.; Solimando, A.G.; Lamanuzzi, A.; Ria, R.; Storlazzi, C.T.; Mariggio, M.A.; Vacca, A.; Frassanito, M.A. Mechanisms of Resistance to Anti-CD38 Daratumumab in Multiple Myeloma. Cells 2020, 9, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chillemi, A.; Quarona, V.; Antonioli, L.; Ferrari, D.; Horenstein, A.L.; Malavasi, F. Roles and Modalities of Ectonucleotidases in Remodeling the Multiple Myeloma Niche. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Umezu, T.; Tadokoro, H.; Azuma, K.; Yoshizawa, S.; Ohyashiki, K.; Ohyashiki, J.H. Exosomal miR-135b shed from hypoxic multiple myeloma cells enhances angiogenesis by targeting factor-inhibiting HIF-1. Blood 2014, 124, 3748–3757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Hong, J.; Hong, M.; Wang, Y.; Yu, T.; Zang, S.; Wu, Q. piRNA-823 delivered by multiple myeloma-derived extracellular vesicles promoted tumorigenesis through re-educating endothelial cells in the tumor environment. Oncogene 2019, 38, 5227–5238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ria, R.; Catacchio, I.; Berardi, S.; De Luisi, A.; Caivano, A.; Piccoli, C.; Ruggieri, V.; Frassanito, M.A.; Ribatti, D.; Nico, B.; et al. HIF-1alpha of bone marrow endothelial cells implies relapse and drug resistance in patients with multiple myeloma and may act as a therapeutic target. Clin. Cancer Res. 2014, 20, 847–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bhaskar, A.; Tiwary, B.N. Hypoxia inducible factor-1 alpha and multiple myeloma. Int. J. Adv. Res. 2016, 4, 706–715. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, X.; Sun, M.; Wu, H.; Chen, C.; Li, H.; Qiu, S.; Wang, T.; Han, J.; Xiao, Q.; Chen, K. Exosome-derived miR-let-7c promotes angiogenesis in multiple myeloma by polarizing M2 macrophages in the bone marrow microenvironment. Leuk. Res. 2021, 105, 106566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sedlarikova, L.; Bollova, B.; Radova, L.; Brozova, L.; Jarkovsky, J.; Almasi, M.; Penka, M.; Kuglik, P.; Sandecka, V.; Stork, M.; et al. Circulating exosomal long noncoding RNA PRINS-First findings in monoclonal gammopathies. Hematol. Oncol. 2018, 36, 786–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Pan, L.; Xiang, B.; Zhu, H.; Wu, Y.; Chen, M.; Guan, P.; Zou, X.; Valencia, C.A.; Dong, B.; et al. Potential role of exosome-associated microRNA panels and in vivo environment to predict drug resistance for patients with multiple myeloma. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 30876–30891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Xu, H.; Han, H.; Song, S.; Yi, N.; Qian, C.; Qiu, Y.; Zhou, W.; Hong, Y.; Zhuang, W.; Li, Z.; et al. Exosome-Transmitted PSMA3 and PSMA3-AS1 Promote Proteasome Inhibitor Resistance in Multiple Myeloma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 1923–1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Khan, A.; Huang, R.; Ye, S.; Di, K.; Xiong, T.; Li, Z. Recent advances in single extracellular vesicle detection methods. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2020, 154, 112056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchisio, M.; Simeone, P.; Bologna, G.; Ercolino, E.; Pierdomenico, L.; Pieragostino, D.; Ventrella, A.; Antonini, F.; Del Zotto, G.; Vergara, D.; et al. Flow Cytometry Analysis of Circulating Extracellular Vesicle Subtypes from Fresh Peripheral Blood Samples. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 22, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russo, M.; Tirinato, L.; Scionti, F.; Coluccio, M.L.; Perozziello, G.; Riillo, C.; Mollace, V.; Gratteri, S.; Malara, N.; Di Martino, M.T.; et al. Raman Spectroscopic Stratification of Multiple Myeloma Patients Based on Exosome Profiling. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 30436–30443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurenzana, I.; Trino, S.; Lamorte, D.; Girasole, M.; Dinarelli, S.; De Stradis, A.; Grieco, V.; Maietti, M.; Traficante, A.; Statuto, T.; et al. Analysis of Amount, Size, Protein Phenotype and Molecular Content of Circulating Extracellular Vesicles Identifies New Biomarkers in Multiple Myeloma. Int. J. Nanomed. 2021, 16, 3141–3160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raimondo, S.; Giavaresi, G.; Lorico, A.; Alessandro, R. Extracellular Vesicles as Biological Shuttles for Targeted Therapies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thompson, C.A.; Purushothaman, A.; Ramani, V.C.; Vlodavsky, I.; Sanderson, R.D. Heparanase regulates secretion, composition, and function of tumor cell-derived exosomes. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 10093–10099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ritchie, J.P.; Ramani, V.C.; Ren, Y.; Naggi, A.; Torri, G.; Casu, B.; Penco, S.; Pisano, C.; Carminati, P.; Tortoreto, M.; et al. SST0001, a chemically modified heparin, inhibits myeloma growth and angiogenesis via disruption of the heparanase/syndecan-1 axis. Clin. Cancer Res. 2011, 17, 1382–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cheng, Q.; Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Dong, M.; Zhan, F.H.; Liu, J. The ceramide pathway is involved in the survival, apoptosis and exosome functions of human multiple myeloma cells in vitro. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2018, 39, 561–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menck, K.; Sonmezer, C.; Worst, T.S.; Schulz, M.; Dihazi, G.H.; Streit, F.; Erdmann, G.; Kling, S.; Boutros, M.; Binder, C.; et al. Neutral sphingomyelinases control extracellular vesicles budding from the plasma membrane. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2017, 6, 1378056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vuckovic, S.; Vandyke, K.; Rickards, D.A.; McCauley Winter, P.; Brown, S.H.J.; Mitchell, T.W.; Liu, J.; Lu, J.; Askenase, P.W.; Yuriev, E.; et al. The cationic small molecule GW4869 is cytotoxic to high phosphatidylserine-expressing myeloma cells. Br. J. Haematol. 2017, 177, 423–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Tu, C.; Zhang, J.; Wang, J. Inhibition of multiple myelomaderived exosomes uptake suppresses the functional response in bone marrow stromal cell. Int. J. Oncol. 2019, 54, 1061–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, C.; Du, Z.; Zhang, H.; Feng, Y.; Qi, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, J. Endocytic pathway inhibition attenuates extracellular vesicle-induced reduction of chemosensitivity to bortezomib in multiple myeloma cells. Theranostics 2021, 11, 2364–2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Y.; Bai, O.; Zhang, H.; Yuan, J.; Zong, S.; Chibbar, R.; Slattery, K.; Qureshi, M.; Wei, Y.; Deng, Y.; et al. Membrane-bound HSP70-engineered myeloma cell-derived exosomes stimulate more efficient CD8(+) CTL- and NK-mediated antitumour immunity than exosomes released from heat-shocked tumour cells expressing cytoplasmic HSP70. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2010, 14, 2655–2666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Xie, Y.; Bai, O.; Zhang, H.; Li, W.; Xiang, J. Tumor necrosis factor gene-engineered J558 tumor cell-released exosomes stimulate tumor antigen P1A-specific CD8+ CTL responses and antitumor immunity. Cancer Biother. Radiopharm. 2010, 25, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Cao, Z.; Wang, P.; Zhang, X.; Tang, J.; He, Y.; Huang, Z.; Mao, X.; Shi, S.; Kou, X. Apoptotic Extracellular Vesicles Ameliorate Multiple Myeloma by Restoring Fas-Mediated Apoptosis. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 14360–14372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desantis, V.; Saltarella, I.; Lamanuzzi, A.; Melaccio, A.; Solimando, A.G.; Mariggio, M.A.; Racanelli, V.; Paradiso, A.; Vacca, A.; Frassanito, M.A. MicroRNAs-Based Nano-Strategies as New Therapeutic Approach in Multiple Myeloma to Overcome Disease Progression and Drug Resistance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Li, S.; Song, J.; Ji, T.; Zhu, M.; Anderson, G.J.; Wei, J.; Nie, G. A doxorubicin delivery platform using engineered natural membrane vesicle exosomes for targeted tumor therapy. Biomaterials 2014, 35, 2383–2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; He, L.; Huang, X.; Zhang, S.; Cao, W.; Che, F.; Zhu, Y.; Dai, J. Recent Progress of Exosomes in Multiple Myeloma: Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, Prognosis and Therapeutic Strategies. Cancers 2021, 13, 1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, D.S.; Kang, Y.K.; Borad, M.; Sachdev, J.; Ejadi, S.; Lim, H.Y.; Brenner, A.J.; Park, K.; Lee, J.L.; Kim, T.Y.; et al. Phase 1 study of MRX34, a liposomal miR-34a mimic, in patients with advanced solid tumours. Br. J. Cancer 2020, 122, 1630–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Cargo Molecule | EVs Source | Target Cells | Biological Effect in Target Cells | Studies Model | Clinical Relevance | Clinical Application | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WWC2 | MM cells | FBs | Hippo pathway activation; miR-27b-3p and miR214-3p | In vitro | Transition MGUS to MM | Prognostic * | [68] |

| IL-6, MCP-1, fibronectin, miR-15a | MSCs | MM cells | Tumor growth | In vitro and in vivo | Tumor progression | Prognostic * | [74] |

| MCP-1, MIP-1α, SDF-1 | BMSCs | MM cells | Activation of JNK, p38, p53, AKT pathways | In vitro | Tumor progression | Prognostic * | [76] |

| RUNX2-AS1 | MM cells | MSCs | Down-regulation of RUNX2 expression and of osteogenic potential | In vitro and in vivo | Tumor-associated bone loss | Prognostic * | [85] |

| Not specified | BMSCs, MM cells | MSDCs | Increased STATs-mediated viability | In vitro and in vivo | Immunosuppression | Prognostic * | [94,95] |

| miR-129-5p | MM cells, BM plasma | MSCs | Down-regulation of Sp1 and reduced osteogenic differentiation | In vitro and ex vivo | Bone lesions, transition SMM to MM | Prognostic | [86] |

| Angiogenin, HGF, MMP-9, VEGF | MM cells | ECs | Enhanced viability | In vitro and in vivo | Increased angiogenesis | Prognostic | [95] |

| IL32 | MM cells | preOCs | Increased osteoclast activity | In vitro and ex vivo | Osteolytic bone disease, reduced PFS | Prognostic | [82] |

| miR-135b | Hypoxic MM cell lines | ECs | Downregulation FIH-1 | In vitro and in vivo | Increased angiogenesis | Prognostic | [99] |

| let-7b and miR-18a | Plasma | Not specified | Not specified | Ex vivo | Negative correlation with PFS and OS | Prognostic | [62] |

| Adenosinergic ectoenzymes | BM plasma | Not specified | Increased ADO | Ex vivo | Immunosuppression, HD to MM transition | Diagnostic | [96] |

| miR-20a-5p, miR-103a-3p, miR-4505 | Serum | Not specified | Not specified | Ex vivo | HD and MM transition transition | Diagnostic | [63] |

| Let-7c-5p, miR-185-5p, miR-4741 | Serum | Not specified | Not specified | Ex vivo | SMM to MM transition | Diagnostic | [63] |

| lncRNA PRINS | Serum | Not specified | Not specified | Ex vivo | Correlation with biochemical parameters in MGUS and MM patients | Diagnostic | [104] |

| PSMA3 mRNA, PSMA3-AS1 | MSCs | Not specified | Increased PSMA3 protein levels and increased proteasome activity | In vitro and ex vivo | Resistance to proteasome inhibitors, high levels correlating to OS and PFF | Prognostic, Response to therapy | [106] |

| miR-16-5p, miR-15a-5p, miR-20a-5p, miR-17-5p | Serum | Not specified | Not specified | Ex vivo | Resistance to bortezomib | Prognostic, Response to therapy | [105] |

| UPR proteins | MM cells | Macrophages | OCs terminal differentiation | In vitro | Bone resorption | Prognostic, Therapeutic target | [80] |

| piRNA-823 | MM cells, serum | ECs | Increased survival, proliferation, and angiogenesis | In vitro and ex vivo | Increased angiogenesis, poor prognosis | Prognostic, Therapeutic target | [100] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Saltarella, I.; Lamanuzzi, A.; Apollonio, B.; Desantis, V.; Bartoli, G.; Vacca, A.; Frassanito, M.A. Role of Extracellular Vesicle-Based Cell-to-Cell Communication in Multiple Myeloma Progression. Cells 2021, 10, 3185. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells10113185

Saltarella I, Lamanuzzi A, Apollonio B, Desantis V, Bartoli G, Vacca A, Frassanito MA. Role of Extracellular Vesicle-Based Cell-to-Cell Communication in Multiple Myeloma Progression. Cells. 2021; 10(11):3185. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells10113185

Chicago/Turabian StyleSaltarella, Ilaria, Aurelia Lamanuzzi, Benedetta Apollonio, Vanessa Desantis, Giulia Bartoli, Angelo Vacca, and Maria Antonia Frassanito. 2021. "Role of Extracellular Vesicle-Based Cell-to-Cell Communication in Multiple Myeloma Progression" Cells 10, no. 11: 3185. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells10113185

APA StyleSaltarella, I., Lamanuzzi, A., Apollonio, B., Desantis, V., Bartoli, G., Vacca, A., & Frassanito, M. A. (2021). Role of Extracellular Vesicle-Based Cell-to-Cell Communication in Multiple Myeloma Progression. Cells, 10(11), 3185. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells10113185