Deficit Irrigation and Preharvest Chitosan Sprays Enhance Fruit Quality and Postharvest Performance in Peach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material, Growing Conditions and Experimental Design

- FI–Q (Control–With chitosan): 100% ETc irrigation, sprayed with QuitoMax® solution.

- FI–NQ (Control–No chitosan): 100% ETc irrigation, untreated.

- DI–Q (Deficit irrigation–With chitosan): 67% ETc, sprayed with QuitoMax® solution.

- DI–NQ (Deficit irrigation–No chitosan): 67% ETc irrigation, untreated.

2.2. Physicochemical Quality Parameters

2.3. Organic Acids, Sugars, and Sweetness Index

2.4. Antioxidant Activity (AA) and Total Phenolics Content (TPC)

2.5. Phenolic Compounds

2.6. Mineral Content

2.7. Postharvest Performance

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

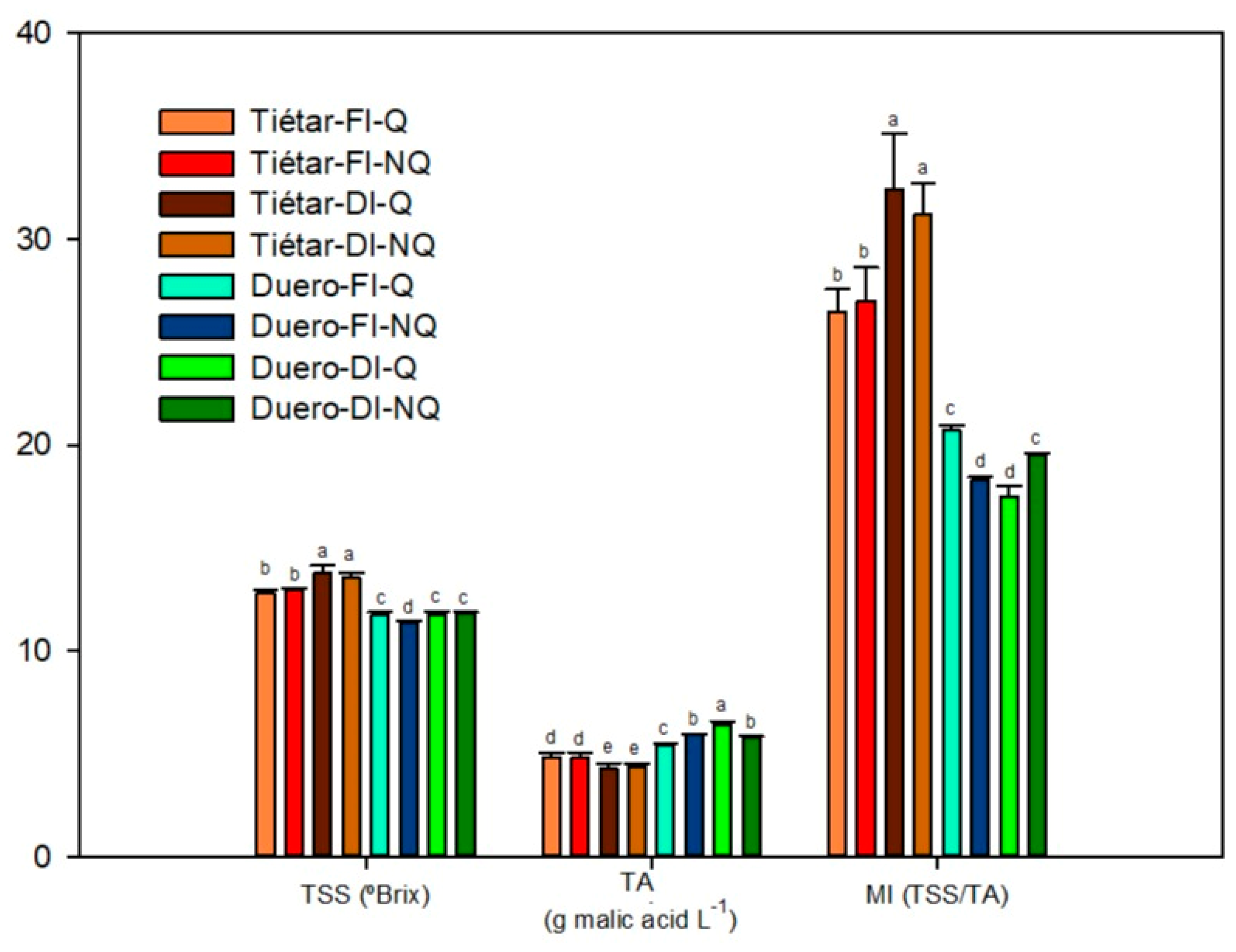

3.1. Physicochemical Quality Parameters

3.2. Organic Acids, Sugars and Sweetness Index

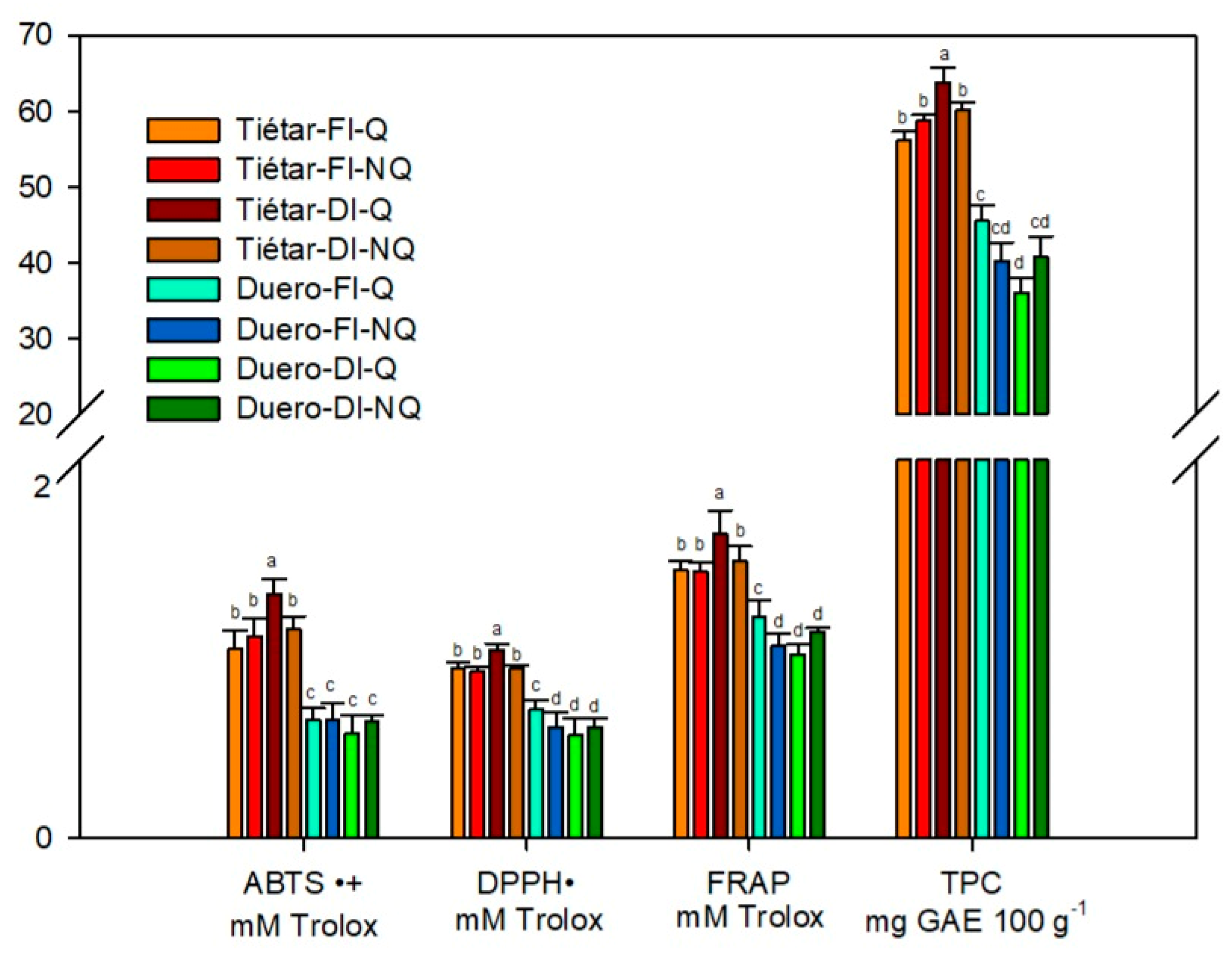

3.3. Antioxidant Activity and Total Phenolics Content

3.4. Phenolic Compounds

3.5. Mineral Content

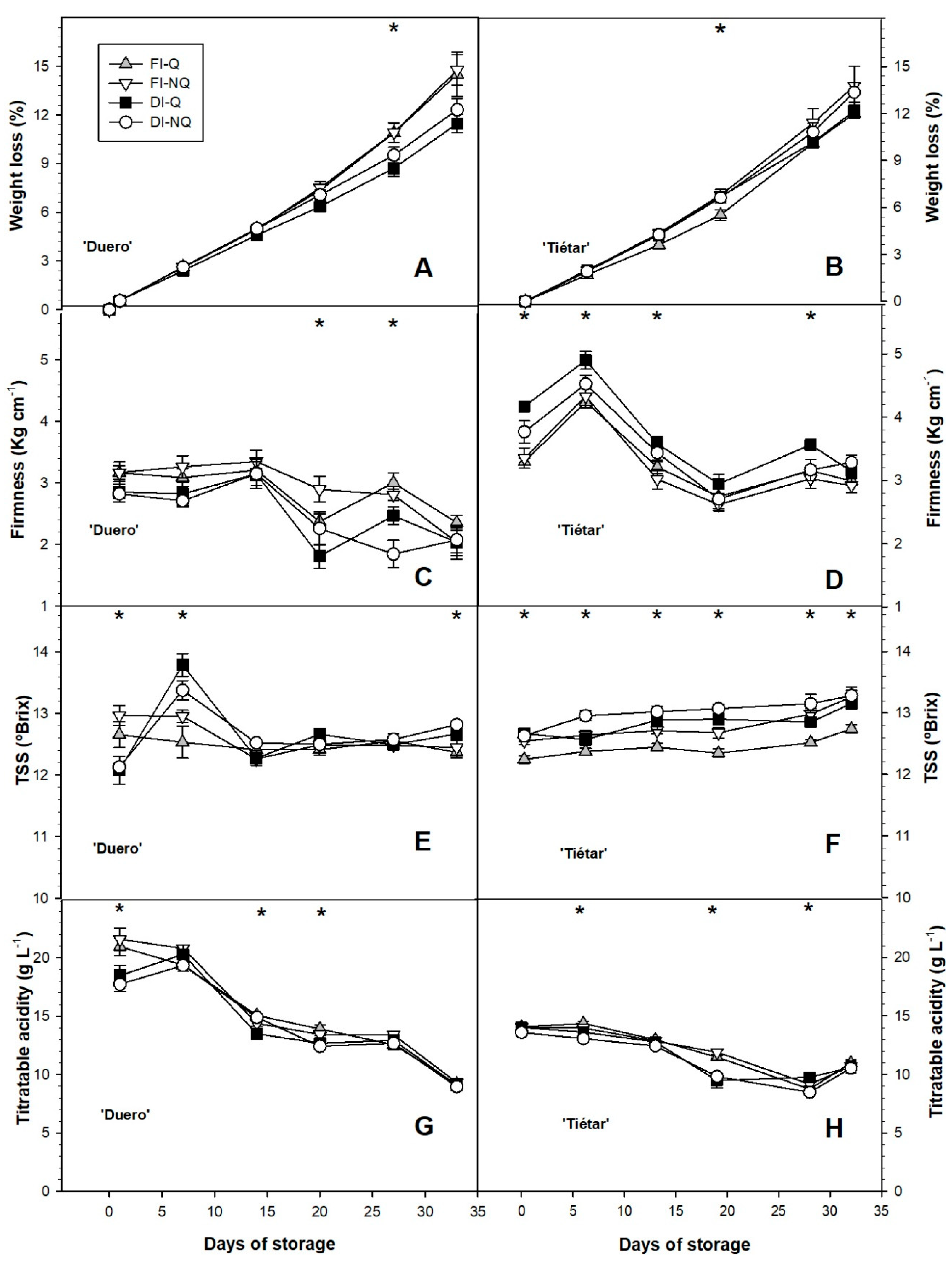

3.6. Postharvest Performance

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

| DI | Deficit irrigation |

| ETc | Crop evapotranspiration |

| FI | Full irrigation |

| MI | Maturity index |

| SΨ | Water stress integral |

| TA | Titratable acidity |

| TSS | Total soluble solids |

| Ψstem | Stem water potential |

References

- Legg, S. Interaction. Climate Change 2021—The Physical Science Basis; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 49, pp. 44–45. [Google Scholar]

- Urdiales-Flores, D.; Zittis, G.; Hadjinicolaou, P.; Osipov, S.; Klingmüller, K.; Mihalopoulos, N.; Kanakidou, M.; Economou, T.; Lelieveld, J. Drivers of accelerated warming in Mediterranean climate-type regions. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2023, 6, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Sánchez, M.C.; Domingo, R.; Castel, J.R. Review: Deficit irrigation in fruit trees and vines in Spain. Span. J. Agric. Res. 2010, 8, S5–S20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. FAOSTAT Statistical Database. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2023. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/ (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- MAPA. Anuario de Estadística Agraria 2024; Ministerio de Agricultura, Pesca y Alimentación: Madrid, Spain, 2024; Available online: https://www.mapa.gob.es/es/agricultura/temas/producciones-agricolas/boletin6_2024frutadehuesocampana202427deseptiembre2024_tcm30-697931.pdf (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Chaves, M.M. Effects of water deficits on carbon assimilation. J. Exp. Bot. 1991, 42, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Losciale, P.; Gaeta, L.; Corsi, M.; Galeone, C.; Tarricone, L.; Leogrande, R.; Stellacci, A.M. Physiological responses of apricot and peach cultivars under progressive water shortage: Different crop signals for anisohydric and isohydric behaviours. Agric. Water Manag. 2023, 286, 108384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalmers, D.J.; Mitchell, P.D.; Van Heek, L. Control of peach tree growth and productivity by regulated water supply, tree density, and summer pruning. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 1981, 106, 307–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fereres, E.; Goldhamer, D.A. Deciduous fruit and nut trees. In Irrigation of Agricultural Crops; Stewart, B.A., Nielsen, D.R., Eds.; ASA-CSSA-SSSA: Madison, WI, USA, 1990; pp. 987–1017. [Google Scholar]

- Galindo, A.; Calín-Sánchez, Á.; Griñán, I.; Rodríguez, P.; Cruz, Z.N.; Girón, I.F.; Corell, M.; Martínez-Font, R.; Moriana, A.; Carbonell-Barrachina, A.A.; et al. Water stress at the end of the pomegranate fruit ripening stage produces earlier harvest and improves fruit quality. Sci. Hortic. 2017, 226, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toumi, I.; Zarrouk, O.; Ghrab, M.; Nagaz, K. Improving peach fruit quality traits using deficit irrigation strategies in southern Tunisia arid area. Plants 2022, 11, 1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreu-Coll, L.; Burló, F.; Galindo, A.; García-Brunton, J.; Vigueras-Fernández, J.; Blaya-Ros, P.J.; Martínez-Font, R.; Noguera-Artiaga, L.; Sendra, E.; Hernández, F.; et al. Enhancing ‘Mirlo Rojo’ Apricot (Prunus armeniaca L.) Quality Through Regulated Deficit Irrigation: Effects on Antioxidant Activity, Fatty Acid Profile, and Volatile Compounds. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajid, M.; Basit, A.; Khan, S.; Nafees, M.; Ullah, S. Chitosan-based foliar application modulated the yield and biochemical attributes of peach (Prunus persica L.) cv. Early Grand. Bull. Natl. Res. Cent. 2020, 44, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidangmayum, A.; Dwivedi, P.; Katiyar, D.; Hemantaranjan, A. Application of chitosan on plant responses with special reference to abiotic stress. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2019, 25, 313–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.J.; Sakhi, S.; Azam, N.; Ahmad, Z.; Hadayat, N.; Ahmad, B.; Hussain, F.; Shuaib, M.; Khan, S.; Hussain, F.; et al. Effect of Chitosan and Gibberellic Acid on Fruit Yield and Production of Peach (Prunus persica L.). Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2024, 33, 721–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griñán, I.; Morales, D.; Collado-González, J.; Falcón-Rodríguez, A.B.; Torrecillas, A.; Martín-Palomo, M.J.; Centeno, A.; Corell, M.; Carbonell-Barrachina, A.A.; Hernández, F.; et al. Reducing incidence of peel physiopathies and increasing antioxidant activity in pomegranate fruit under different irrigation conditions by preharvest application of chitosan. Sci. Hortic. 2019, 247, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hueso Martín, J.J.; Cuevas González, J. (Eds.) La fruticultura del siglo XXI en España; Cajamar Caja Rural: Almería, Spain, 2014; ISBN -13 978-84-95531-64-3. Available online: https://publicacionescajamar.es/series-tematicas/agricultura/la-fruticultura-del-siglo-xxi-en-espana/ (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- SIAM. Sistema de Información Agraria de Murcia; Consejería de Agricultura: Región de Murcia, Spain; Available online: http://siam.imida.es/apex/f?p=101:1:1412596729992377 (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Allen, R.G.; Pereira, L.S.; Raes, D.; Smith, M. Crop Evapotranspiration—Guidelines for Computing Crop Water Requirements; FAO Irrigation and Drainage Paper No. 56; FAO: Rome, Italy, 1998; ISBN 9253042192. [Google Scholar]

- Girona, J.; Fereres, E. Peach. In Crop Yield Response to Water; Steduto, P., Hsiao, T.C., Fereres, E., Raes, D., Eds.; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2012; pp. 392–406. [Google Scholar]

- Fereres, E.; Martinich, D.; Aldrich, T.; Castel, J.R.; Holzapfel, E.; Schulbach, H. Drip irrigation saves money in young almond orchards. Calif. Agric. 1982, 36, 12–13. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, B.J. Water stress integral—A link between short-term stress and long-term growth. Tree Physiol. 1988, 4, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández, F.; Noguera-Artiaga, L.; Burló, F.; Wojdyło, A.; Carbonell-Barrachina, Á.A.; Legua, P. Physico-chemical, nutritional, and volatile composition and sensory profile of Spanish jujube (Ziziphus jujuba Mill.) fruits. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2016, 96, 2682–2691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keutgen, A.; Pawelzik, E. Modifications of taste-relevant compounds in strawberry fruit under NaCl salinity. Food Chem. 2007, 105, 1487–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojdyło, A.; Oszmiański, J.; Laskowski, P. Polyphenolic compounds and antioxidant activity of new and old apple varieties. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 6520–6530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand-Williams, W.; Cuvelier, M.E.; Berset, C. Use of a free radical method to evaluate antioxidant activity. LWT–Food Sci. Technol. 1995, 28, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzie, I.F.F.; Strain, J.J. The ferric reducing ability of plasma (FRAP) as a measure of “antioxidant power”: The FRAP assay. Anal. Biochem. 1996, 239, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Re, R.; Pellegrini, N.; Proteggente, A.; Pannala, A.; Yang, M.; Rice-Evans, C. Antioxidant activity applying an improved ABTS radical cation decolorization assay. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999, 26, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, V.L.; Orthofer, R.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.M. Analysis of total phenols and other oxidation substrates and antioxidants by means of Folin–Ciocalteu reagent. Methods Enzymol. 1999, 299, 152–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caranqui-Aldaz, J.M.; Muelas-Domingo, R.; Hernández, F.; Martínez, R. Chemical composition and polyphenol compounds of Vaccinium floribundum Kunth (Ericaceae) from the volcano Chimborazo Páramo (Ecuador). Horticulturae 2022, 8, 956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addinsoft. XLSTAT Software, version 9; Addinsoft: Barcelona, Spain, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Systat Software, version 12.5; SigmaPlot for Windows; Systat Software Inc.: San Jose, CA, USA, 2013.

- Crisosto, C.H.; Crisosto, G.M. Relationship between ripe soluble solids concentration (RSSC) and consumer acceptance of high- and low-acid melting-flesh peach and nectarine cultivars. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2005, 38, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girona, J.; Mata, M.; Arbonès, A.; Alegre, S.; Rufat, J.; Marsal, J. Peach tree response to single and combined regulated deficit irrigation regimes under shallow soils. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 2003, 128, 432–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcobendas, R.; Mounzer, O.; Alarcón, J.J.; Nicolás, E. Effects of irrigation and fruit position on size, colour, firmness and sugar contents of fruits in a mid-late maturing peach cultivar. Sci. Hortic. 2013, 164, 340–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera, J.; Abrisqueta, I.; Abrisqueta, J.M.; Ruiz-Sánchez, M.C. Effect of deficit irrigation on early-maturing peach tree performance. Irrig. Sci. 2013, 31, 747–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanazzi, G.; Gabler, F.M.; Smilanick, J.L. Preharvest chitosan and postharvest UV irradiation treatments suppress gray mold of table grapes. Plant Dis. 2006, 90, 445–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Zhang, F.; Kjelgren, R.; Wu, L.; Gong, D.; Zhao, N.; Yin, D.; Xiang, Y.; Li, Z. Peach yield and fruit quality is maintained under mild deficit irrigation in semi-arid China. J. Integr. Agric. 2017, 16, 1173–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Gartung, J. Long-term productivity of early season peach trees under postharvest deficit irrigation. Agric. Water Manag. 2020, 231, 105940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliman, N.G.; Nomier, S.A.A.; Ibrahim, M.; Gad, M.M. Effect of spraying nano-chitosan and nano-silicon on physicochemical fruit quality and leaf mineral content of Florida Prince peach trees. Zagazig J. Agric. Res. 2021, 48, 1215–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmenofy, H.M.; Okba, S.K.; Salama, A.-M.; Alam-Eldein, S.M. Yield, fruit quality, and storability of ‘Canino’ apricot in response to aminoethoxyvinylglycine, salicylic acid, and chitosan. Plants 2021, 10, 1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giacalone, G.; Chiabrando, V. Effect of preharvest and postharvest application of chitosan coating on storage quality of nectarines. Acta Hortic. 2015, 1084, 675–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelly, M.; Recasens, I.; Girona, J.; Mata, M.; Arbonès, A.; Rufat, J.; Marsal, J. Effects of stage II and postharvest deficit irrigation on peach quality during maturation and after cold storage. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2004, 84, 561–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Bianco, R.; Rieger, M.; Sung, S.J.S. Effect of drought on sorbitol and sucrose metabolism in sinks and sources of peach. Physiol. Plant. 2000, 108, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantín, C.M.; Gogorcena, Y.; Moreno, M.Á. Analysis of phenotypic variation of sugar profile in different peach and nectarine [Prunus persica (L.) Batsch] breeding progenies. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2009, 89, 1909–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.-H.; Génard, M.; Lescourret, F.; Gomez, L.; Li, S.-H. Influence of assimilate and water supply on seasonal variation of acids in peach (cv Suncrest). J. Sci. Food Agric. 2002, 82, 1829–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buendía, B.; Allende, A.; Nicolás, E.; Alarcón, J.J.; Gil, M.I. Effect of regulated deficit irrigation and crop load on the antioxidant compounds of peaches. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 3601–3608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guizani, M.; Dabbou, S.; Maatallah, S.; Montevecchi, G.; Antonelli, A.; Serrano, M.; Hajlaooui, H.; Rezig, M.; Kilani-Jaziri, S. Evaluation of two water deficit models on phenolic profiles and antioxidant activities of different peach fruits parts. Chem. Biodivers. 2022, 19, e202100851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano-Lamadrid, M.; Hernández, F.; Corell, M.; Burló, F.; Legua, P.; Moriana, A.; Carbonell-Barrachina, Á.A. Antioxidant capacity, fatty acids profile, and descriptive sensory analysis of table olives as affected by deficit irrigation. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2016, 97, 444–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipan, L.; Moriana, A.; López-Lluch, D.B.; Cano-Lamadrid, M.; Sendra, E.; Hernández, F.; Vázquez-Araújo, L.; Corell, M.; Carbonell-Barrachina, Á.A. Nutrition quality parameters of almonds as affected by deficit irrigation strategies. Molecules 2019, 24, 2646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abrisqueta, I.; Quezada-Martin, R.; Munguía-López, J.P.; Ruiz-Sánchez, M.C.; Abrisqueta, J.M.; Vera, J. Nutrient concentrations of peach-tree leaves under deficit irrigation. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2011, 174, 871–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boland, A.M.; Jerie, P.H.; Mitchell, P.D.; Goodwin, I.; Connor, D.J. Long-term Effects of Restricted Root Volume and Regulated Deficit Irrigation on Peach: I. Growth and Mineral Nutrition. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 2000, 125, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Gao, X.; Xiao, L.; Shu, J.; Li, Q.; Liao, M. Effects of Chitosan on the Uptake of Total Calcium, Magnesium and Sodium in Peach Seedlings. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 446, 032005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briat, J.F.; Dubos, C.; Gaymard, F. Iron nutrition, biomass production, and plant product quality. Trends Plant Sci. 2015, 20, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karley, A.J.; White, P.J. Moving cationic minerals to edible tissues: Potassium, magnesium, calcium. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2009, 12, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veneklaas, E.J.; Lambers, H.; Bragg, J.; Finnegan, P.M.; Lovelock, C.E.; Plaxton, W.C.; Price, C.A.; Scheible, W.-R.; Shane, M.W.; White, P.J.; et al. Opportunities for improving phosphorus-use efficiency in crop plants. New Phytol. 2012, 195, 306–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hocking, B.; Tyerman, S.D.; Burton, R.A.; Gilliham, M. Fruit calcium: Transport and physiology. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrasco-Cuello, F.; Van der Heijden, G.; Rufat, J.; Torres, E. Unraveling calcium absorption and distribution in peach and nectarine during fruit development through 44Ca isotope labeling. Plants 2024, 13, 2287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, R.; ValizadehKaji, B.; Khadivi, A.; Shahrjerdi, I. Effect of chitosan and thymol essential oil on quality maintenance and shelf life extension of peach fruits cv. ‘Zaferani’. J. Hortic. Postharvest Res. 2019, 2, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falagán, N.; Artés, F.; Gómez, P.A.; Artés-Hernández, F.; Conejero, W.; Aguayo, E. Deficit irrigation strategies combined with controlled atmosphere preserve quality in early peaches. Food Sci. Technol. Int. 2015, 21, 547–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.J.; Lee, D.B.; Kim, S.J.; Choi, S.J.; Yun, H.K. Extended shelf-life of ‘Kumhong’ nectarine and ‘Madoka’ peach fruits by treating the trees with calcium compounds and chitosan. Korean J. Agric. Sci. 2019, 46, 737–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, K.; Tang, R.; Li, L. Carbon dots–melatonin–chitosan coating to alleviate chilling injury, enhance storage quality and antioxidant capacity of yellow peaches. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2025, 52, 101629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cultivar | Irrigation Treatment | Chitosan Treatment | Weight (g) | Length (mm) | Equatorial Diameter (mm) | Suture Diameter (mm) | Firmness (kg cm−2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tiétar | Full irrigation | Chitosan | 217 b 1 | 71.5 bc | 75.4 b | 73.5 b | 4.1 cd |

| Control | 231 a | 76.1 a | 77.3 a | 75.5 a | 4.4 bc | ||

| Deficit irrigation | Chitosan | 203 c | 72.1 b | 74.1 bc | 72.6 b | 4.8 a | |

| Control | 204 c | 72.0 b | 73.4 c | 72.8 b | 3.9 de | ||

| Duero | Full irrigation | Chitosan | 183 de | 71.4 bc | 70.2 de | 69.2 c | 4.7 ab |

| Control | 181 de | 72.1 b | 70.0 de | 68.9 c | 4.3 c | ||

| Deficit irrigation | Chitosan | 191 d | 72.3 b | 71.1 d | 69.8 c | 3.9 de | |

| Control | 178 e | 69.7 c | 69.5 e | 68.7 c | 3.8 e | ||

| ANOVA | *** 2 | *** | *** | *** | *** | ||

| Cultivar | Tiétar | 214 | 72.9 | 75.0 | 73.6 | 4.3 | |

| Duero | 183 | 71.3 | 70.2 | 69.2 | 4.1 | ||

| ANOVA | *** | *** | *** | *** | * | ||

| Irrigation treatment | Full Irrigation | 203 | 72.8 | 73.2 | 71.8 | 4.4 | |

| Deficit irrigation | 194 | 71.5 | 72.0 | 71.0 | 4.1 | ||

| ANOVA | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | ||

| Chitosan application | Chitosan | 199 | 71.8 | 72.7 | 71.3 | 4.4 | |

| Control | 198 | 72.5 | 72.6 | 71.5 | 4.1 | ||

| ANOVA | NS | * | NS | NS | *** | ||

| Cultivar | Irrigation Treatment | Chitosan Treatment | L* (D65) | a* (D65) | b* (D65) | C* (D65) | H° (D65) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tiétar | Full irrigation | Chitosan | 70.4 b 1 | 10.3 b | 44.6 a | 45.9 ab | 76.9 a |

| Control | 69.6 b | 10.9 b | 44.0 ab | 45.6 abc | 75.6 a | ||

| Deficit irrigation | Chitosan | 70.4 b | 10.5 b | 45.1 a | 46.4 a | 77.0 a | |

| Control | 70.3 b | 12.3 ab | 46.0 a | 47.7 a | 75.0 a | ||

| Duero | Full irrigation | Chitosan | 74.7 a | 14.3 a | 40.4 cd | 43.9 cd | 69.0 b |

| Control | 73.9 a | 14.8 a | 39.8 d | 43.6 d | 67.7 b | ||

| Deficit irrigation | Chitosan | 74.7 a | 14.4 a | 40.9 bcd | 44.4 bcd | 69.1 b | |

| Control | 75.8 a | 14.9 a | 42.7 abc | 46.1 ab | 69.7 b | ||

| ANOVA | *** 2 | *** | *** | *** | *** | ||

| Cultivar | Tiétar | 70.2 | 11.0 | 44.9 | 46.4 | 76.1 | |

| Duero | 74.8 | 14.6 | 41.0 | 44.5 | 68.9 | ||

| ANOVA | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | ||

| Irrigation treatment | Full Irrigation | 72.1 | 12.6 | 42.2 | 44.8 | 72.3 | |

| Deficit irrigation | 72.8 | 13.0 | 43.7 | 46.1 | 72.7 | ||

| ANOVA | NS | NS | * | ** | NS | ||

| Chitosan application | Chitosan | 72.5 | 12.4 | 42.8 | 45.1 | 73.0 | |

| Control | 72.4 | 13.2 | 43.1 | 45.8 | 72.0 | ||

| ANOVA | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | ||

| Cultivar | Irrigation Treatment | Chitosan Treatment | Citric | Malic | Quinic | Total Organic Acids | Sucrose | Glucose | Fructose | Total Sugars | SI 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tiétar | Full irrigation | Chitosan | 0.10 e 1 | 0.76 a | 0.17 d | 1.03 de | 26.2 bc | 0.23 g | 0.68 c | 27.1 bcd | 37.2 abc |

| Control | 0.10 e | 0.76 a | 0.17 d | 1.03 de | 27.0 ab | 0.28 fg | 0.91 bc | 28.2 ab | 38.9 abc | ||

| Deficit irrigation | Chitosan | 0.09 e | 0.73 ab | 0.20 b | 1.02 de | 28.0 a | 0.36 de | 1.11 b | 29.5 a | 40.8 a | |

| Control | 0.09 e | 0.73 ab | 0.18 cd | 1.00 e | 26.7 b | 0.38 d | 0.72 c | 27.8 bc | 38.1 abc | ||

| Duero | Full irrigation | Chitosan | 0.24 a | 0.77 a | 0.26 a | 1.26 a | 25.6 c | 0.66 a | 1.73 a | 28.0 b | 39.3 ab |

| Control | 0.22 ab | 0.77 a | 0.20 b | 1.18 b | 24.0 de | 0.47 c | 1.46 a | 26.0 de | 36.3 bc | ||

| Deficit irrigation | Chitosan | 0.18 c | 0.72 b | 0.16 d | 1.06 cd | 23.5 e | 0.31 ef | 1.12 b | 24.9 e | 34.5 c | |

| Control | 0.20 bc | 0.73 ab | 0.19 bc | 1.12 c | 24.5 d | 0.54 b | 1.53 a | 26.6 cd | 37.1 abc | ||

| ANOVA | *** 2 | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | ||

| Cultivar | Tiétar | 0.10 | 0.74 | 0.18 | 1.02 | 27.0 | 0.31 | 0.86 | 28.2 | 38.7 | |

| Duero | 0.21 | 0.75 | 0.20 | 1.16 | 24.4 | 0.49 | 1.46 | 26.3 | 36.8 | ||

| ANOVA | *** | NS | *** | ** | *** | *** | *** | *** | ** | ||

| Irrigation treatment | Full Irrigation | 0.17 | 0.76 | 0.20 | 1.13 | 25.7 | 0.41 | 1.19 | 27.4 | 37.9 | |

| Deficit irrigation | 0.14 | 0.73 | 0.18 | 1.05 | 25.7 | 0.40 | 1.12 | 27.2 | 37.6 | ||

| ANOVA | *** | *** | *** | *** | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | ||

| Chitosan application | Chitosan | 0.15 | 0.75 | 0.20 | 1.09 | 25.8 | 0.39 | 1.16 | 27.4 | 37.9 | |

| Control | 0.15 | 0.74 | 0.18 | 1.08 | 25.6 | 0.42 | 1.15 | 27.1 | 37.6 | ||

| ANOVA | NS | NS | *** | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | ||

| Cultivar | Irrigation Treatment | Chitosan Treatment | NeoCGA 1 | CGA | Q-3-Rut | Q-3-Glcp | Q-3-Glc | Cy-3-Glc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tiétar | Full irrigation | Chitosan | 12.5 d 2 | 12.2 c | 1.16 d | 0.14 bc | 0.53 c | 0.06 c |

| Control | 14.7 bcd | 14.9 bc | 1.54 cd | 0.18 bc | 0.63 bc | 0.09 c | ||

| Deficit irrigation | Chitosan | 17.7 ab | 17.7 a | 1.33 cd | 0.20 bc | 0.73 bc | 0.12 c | |

| Control | 18.0 a | 17.7 ab | 1.19 d | 0.10 c | 0.46 c | 0.08 c | ||

| Duero | Full irrigation | Chitosan | 16.1 abc | 17.3 ab | 2.48 abc | 0.70 ab | 2.25 ab | 1.17 ab |

| Control | 14.4 cd | 15.3 ab | 3.01 ab | 1.12 a | 3.26 a | 1.90 a | ||

| Deficit irrigation | Chitosan | 14.3 cd | 16.3 ab | 3.48 a | 1.27 a | 3.65 a | 1.24 ab | |

| Control | 14.9 abcd | 15.2 ab | 1.97 bcd | 0.37 bc | 1.19 bc | 0.41 bc | ||

| ANOVA | *** 3 | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | ||

| Cultivar | Tiétar | 15.7 a | 15.6 a | 1.30 b | 0.15 b | 0.59 b | 0.07 b | |

| Duero | 14.9 a | 16.0 a | 2.74 a | 0.87 a | 2.58 a | 1.18 a | ||

| ANOVA | NS | NS | *** | *** | *** | *** | ||

| Irrigation treatment | Full Irrigation | 14.4 b | 14.9 b | 2.05 a | 0.53 a | 1.67 a | 0.79 a | |

| Deficit irrigation | 16.2 a | 16.7 a | 1.99 a | 0.49 a | 1.51 a | 0.45 b | ||

| ANOVA | ** | *** | NS | NS | NS | * | ||

| Chitosan application | Chitosan | 15.2 a | 15.9 a | 2.11 a | 0.58 a | 1.79 a | 0.64 a | |

| Control | 15.5 a | 15.8 a | 1.93 a | 0.44 b | 1.38 a | 0.62 a | ||

| ANOVA | NS | NS | NS | * | NS | NS | ||

| Cultivar | Irrigation Treatment | Chitosan Treatment | Macroelements (mg 100 g−1 dw) | Microelements (µg 100 g−1 dw) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | K | Mg | Na | P | Cu | Fe | Mn | Zn | |||

| Tiétar | Full irrigation | Chitosan | 72.2 d 1 | 1795 a | 52.4 bc | 13.7 abc | 149 a | 380 bc | 2277 c | 344 bc | 782 abc |

| Control | 78.2 d | 1585 bc | 50.8 bcd | 9.74 bc | 133 bcd | 361 bc | 2198 c | 348 bc | 705 bc | ||

| Deficit irrigation | Chitosan | 82.3 d | 1650 b | 48.1 d | 15.3 ab | 119 d | 341 c | 2071 c | 299 d | 645 c | |

| Control | 86.4 d | 1611 bc | 47.8 d | 15.8 ab | 123 cd | 332 c | 2587 bc | 338 cd | 767 abc | ||

| Duero | Full irrigation | Chitosan | 181 b | 1510 cd | 53.2 bc | 20.8 a | 130 bcd | 401 ab | 3552 ab | 382 ab | 896 a |

| Control | 92.2 d | 1572 bcd | 57.5 a | 4.99 c | 137 abc | 391 b | 2731 bc | 390 a | 778 abc | ||

| Deficit irrigation | Chitosan | 500 a | 1471 d | 50.5 cd | 8.83 bc | 133 bc | 380 bc | 4088 a | 359 abc | 833 ab | |

| Control | 107 c | 1612 bc | 54.4 ab | 6.35 bc | 142 ab | 443 a | 2680 bc | 368 abc | 862 ab | ||

| ANOVA | *** 2 | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | ||

| Cultivar | Tiétar | 79.8 | 1660 | 49.8 | 13.7 | 131 | 354 | 2283 | 332 | 725 | |

| Duero | 220 | 1541 | 53.9 | 10.3 | 136 | 404 | 3263 | 375 | 842 | ||

| ANOVA | *** | *** | *** | * | * | *** | *** | *** | *** | ||

| Irrigation treatment | Full Irrigation | 106 | 1615 | 53.5 | 12.3 | 137 | 383 | 2690 | 366 | 790 | |

| Deficit irrigation | 194 | 1586 | 50.2 | 11.6 | 129 | 374 | 2856 | 341 | 777 | ||

| ANOVA | * | NS | *** | NS | ** | NS | NS | *** | NS | ||

| Chitosan application | Chitosan | 209 | 1606 | 51.1 | 14.7 | 133 | 375 | 2997 | 346 | 789 | |

| Control | 90.9 | 1595 | 52.6 | 9.22 | 134 | 382 | 2549 | 361 | 778 | ||

| ANOVA | *** | NS | * | *** | NS | NS | ** | * | NS | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Andreu-Coll, L.; Blaya-Ros, P.J.; García-Castellanos, B.; Vigueras-Fernández, J.; Morales-Guevara, D.; García-García, J.; García-Brunton, J.; Calín-Sánchez, Á.; Hernández, F.; Galindo, A. Deficit Irrigation and Preharvest Chitosan Sprays Enhance Fruit Quality and Postharvest Performance in Peach. Agronomy 2026, 16, 361. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16030361

Andreu-Coll L, Blaya-Ros PJ, García-Castellanos B, Vigueras-Fernández J, Morales-Guevara D, García-García J, García-Brunton J, Calín-Sánchez Á, Hernández F, Galindo A. Deficit Irrigation and Preharvest Chitosan Sprays Enhance Fruit Quality and Postharvest Performance in Peach. Agronomy. 2026; 16(3):361. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16030361

Chicago/Turabian StyleAndreu-Coll, Lucía, Pedro J. Blaya-Ros, Begoña García-Castellanos, Jesús Vigueras-Fernández, Donaldo Morales-Guevara, José García-García, Jesús García-Brunton, Ángel Calín-Sánchez, Francisca Hernández, and Alejandro Galindo. 2026. "Deficit Irrigation and Preharvest Chitosan Sprays Enhance Fruit Quality and Postharvest Performance in Peach" Agronomy 16, no. 3: 361. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16030361

APA StyleAndreu-Coll, L., Blaya-Ros, P. J., García-Castellanos, B., Vigueras-Fernández, J., Morales-Guevara, D., García-García, J., García-Brunton, J., Calín-Sánchez, Á., Hernández, F., & Galindo, A. (2026). Deficit Irrigation and Preharvest Chitosan Sprays Enhance Fruit Quality and Postharvest Performance in Peach. Agronomy, 16(3), 361. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16030361