Nature-Based Solutions (NbS) in Agricultural Soils for Greenhouse Gas Mitigation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Soil Organic Carbon (SOC)

3. Soil Inorganic Carbon (SIC)

4. Soil Organic Matter (SOM)

5. Nitrous Oxide (N2O)

6. Methane (CH4)

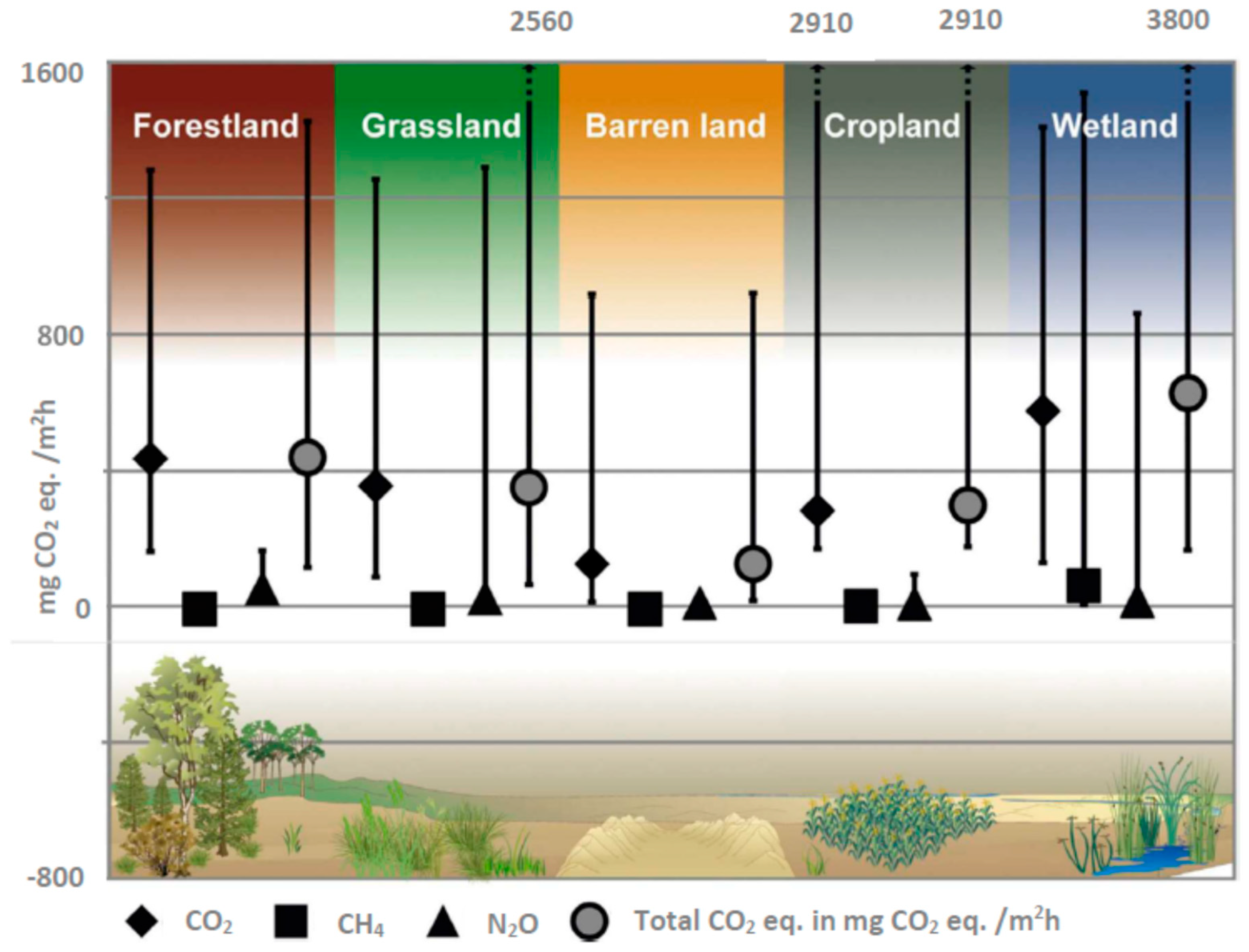

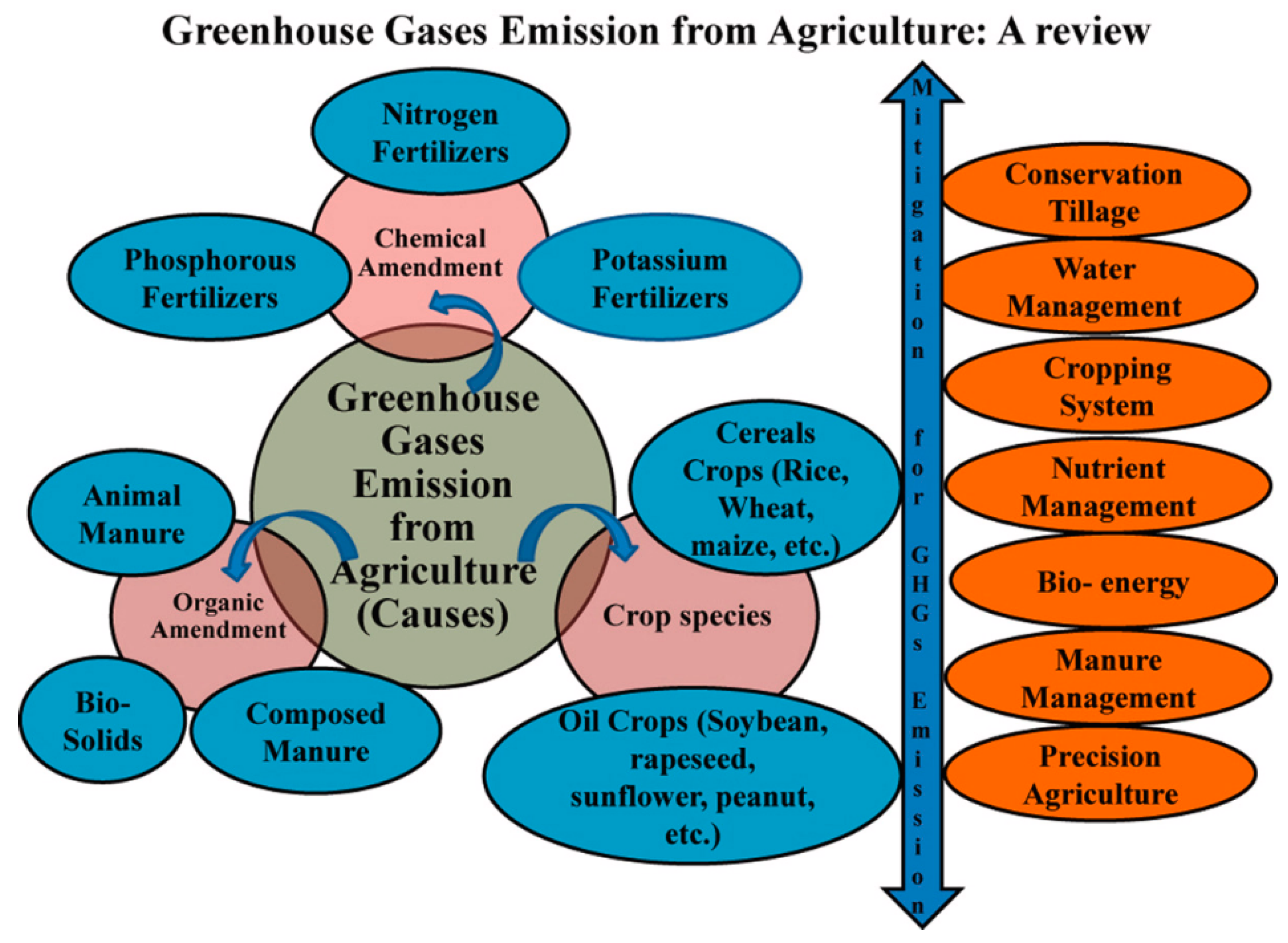

7. SOC and Erosion

8. GHG Emissions from Soil

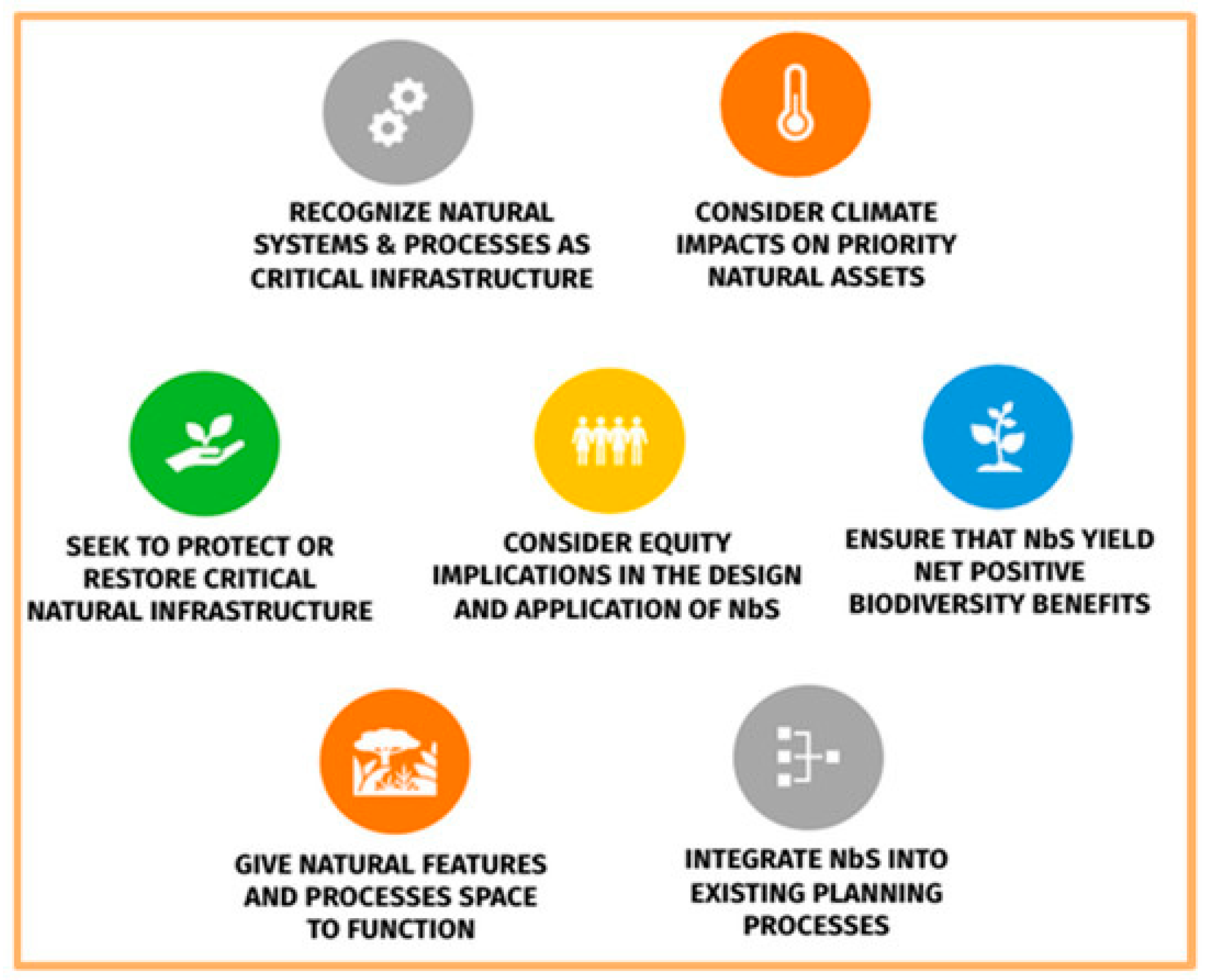

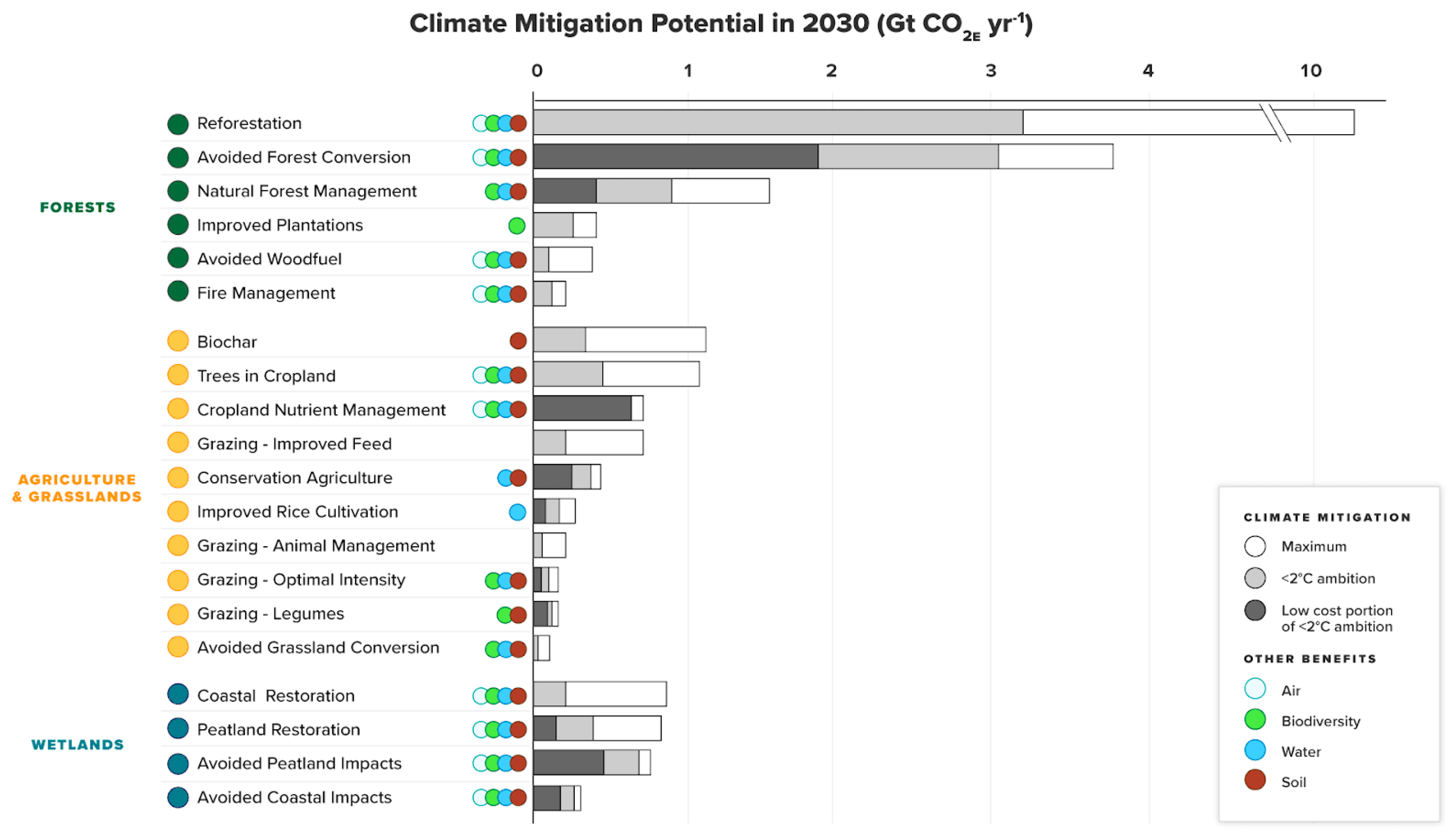

9. Solutions

10. Nature-Based Solution (NbS)

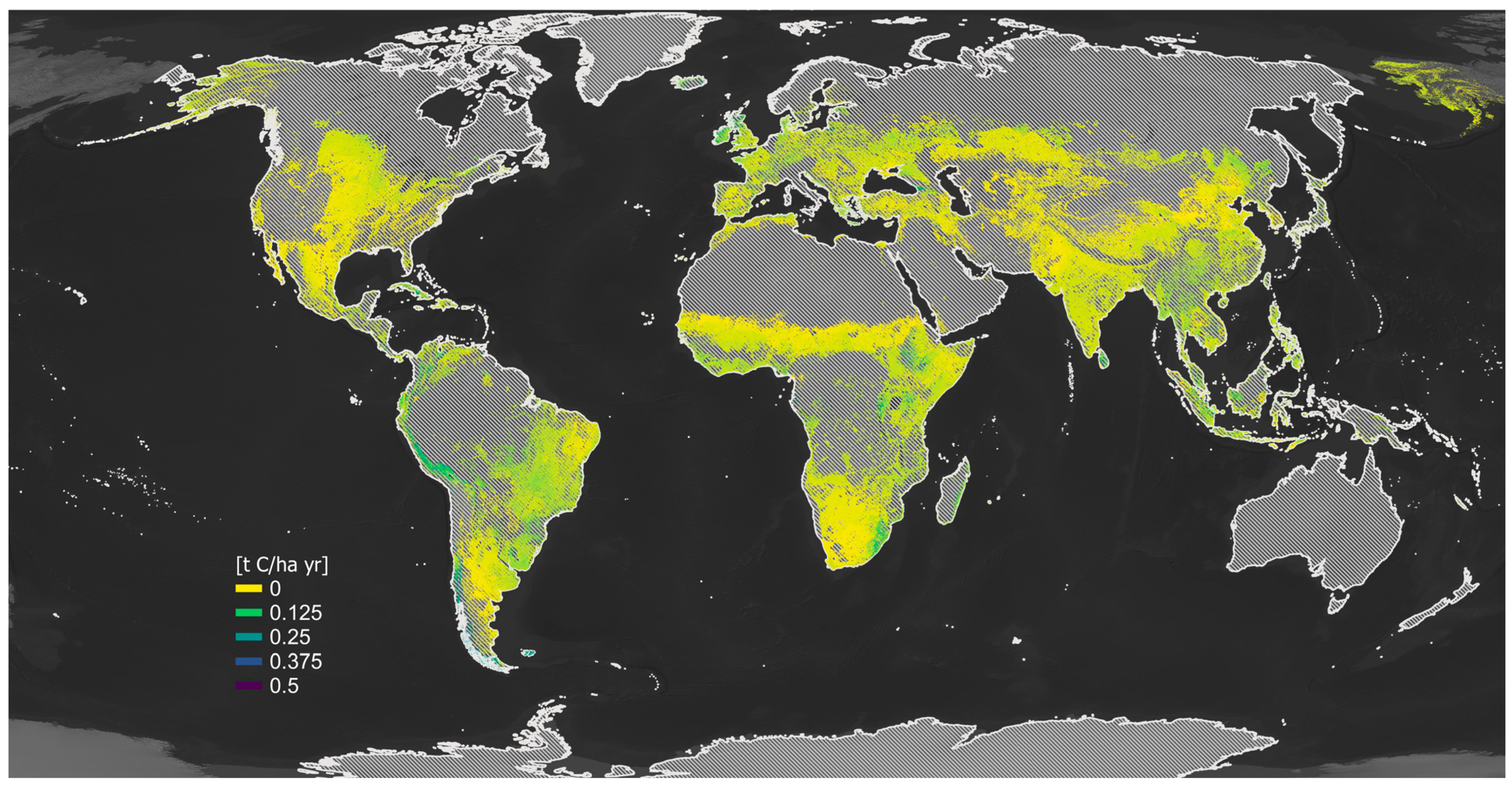

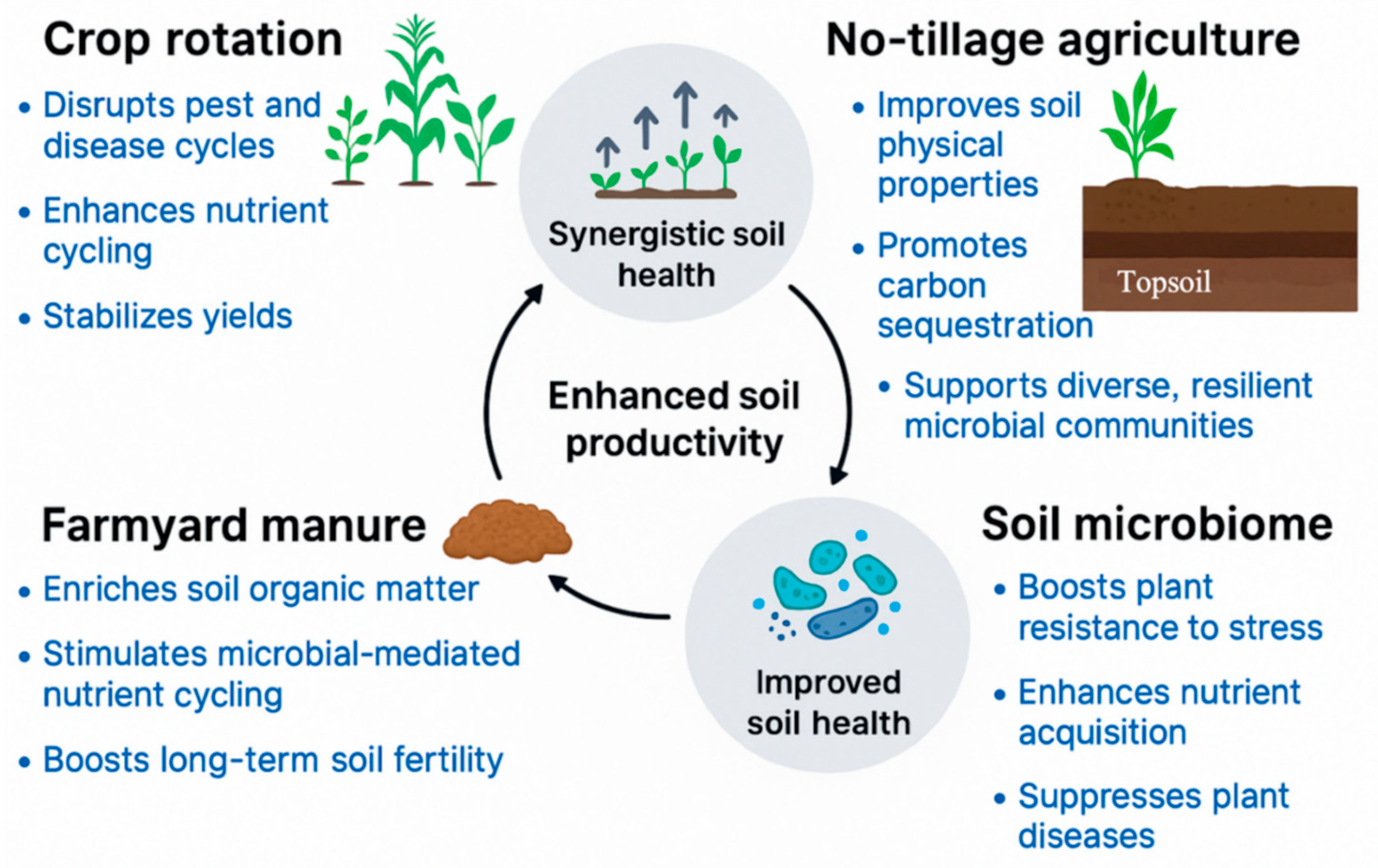

11. SOC Sequestration

12. Tillage

13. Water Management

14. Organic Agriculture

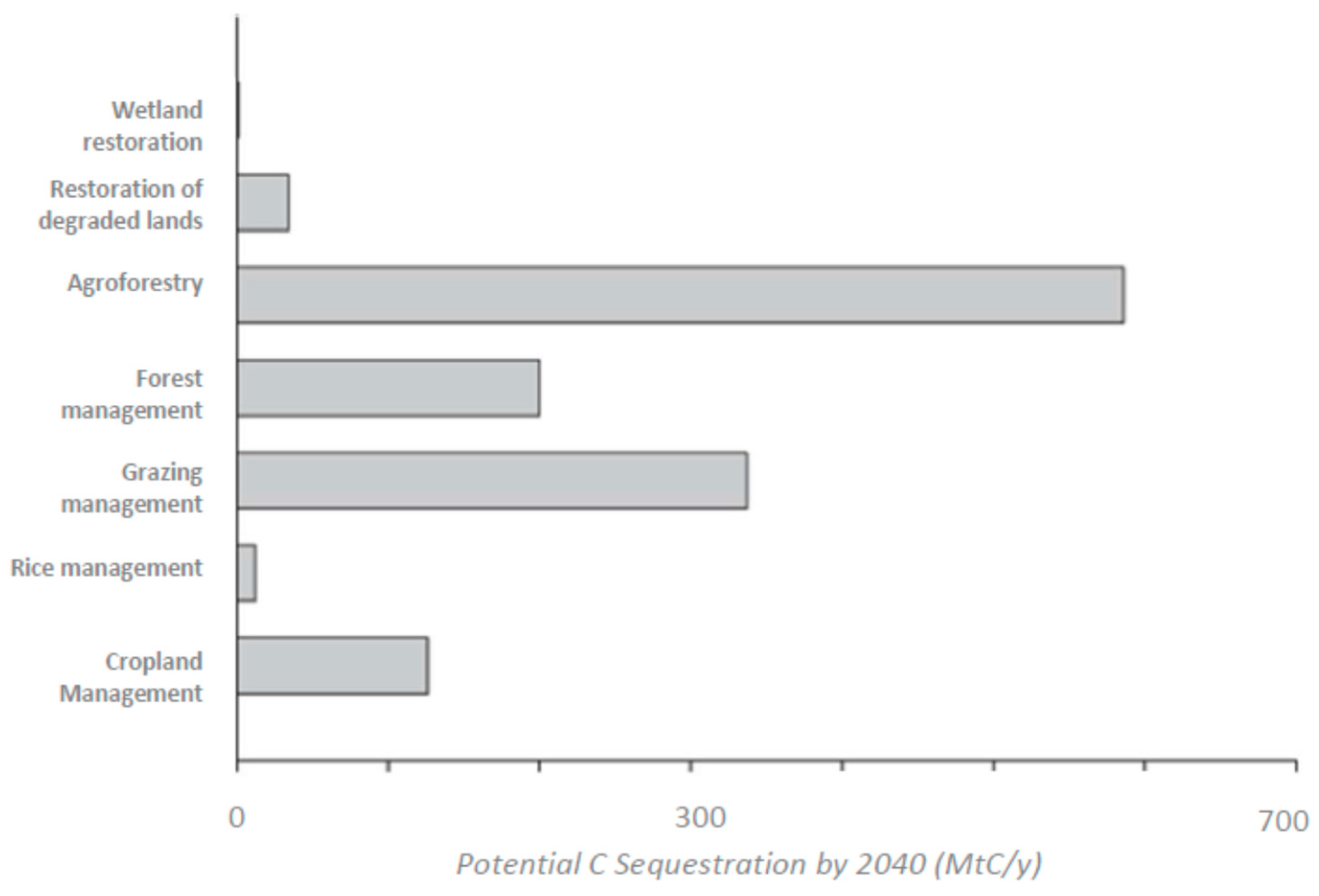

15. Biochar

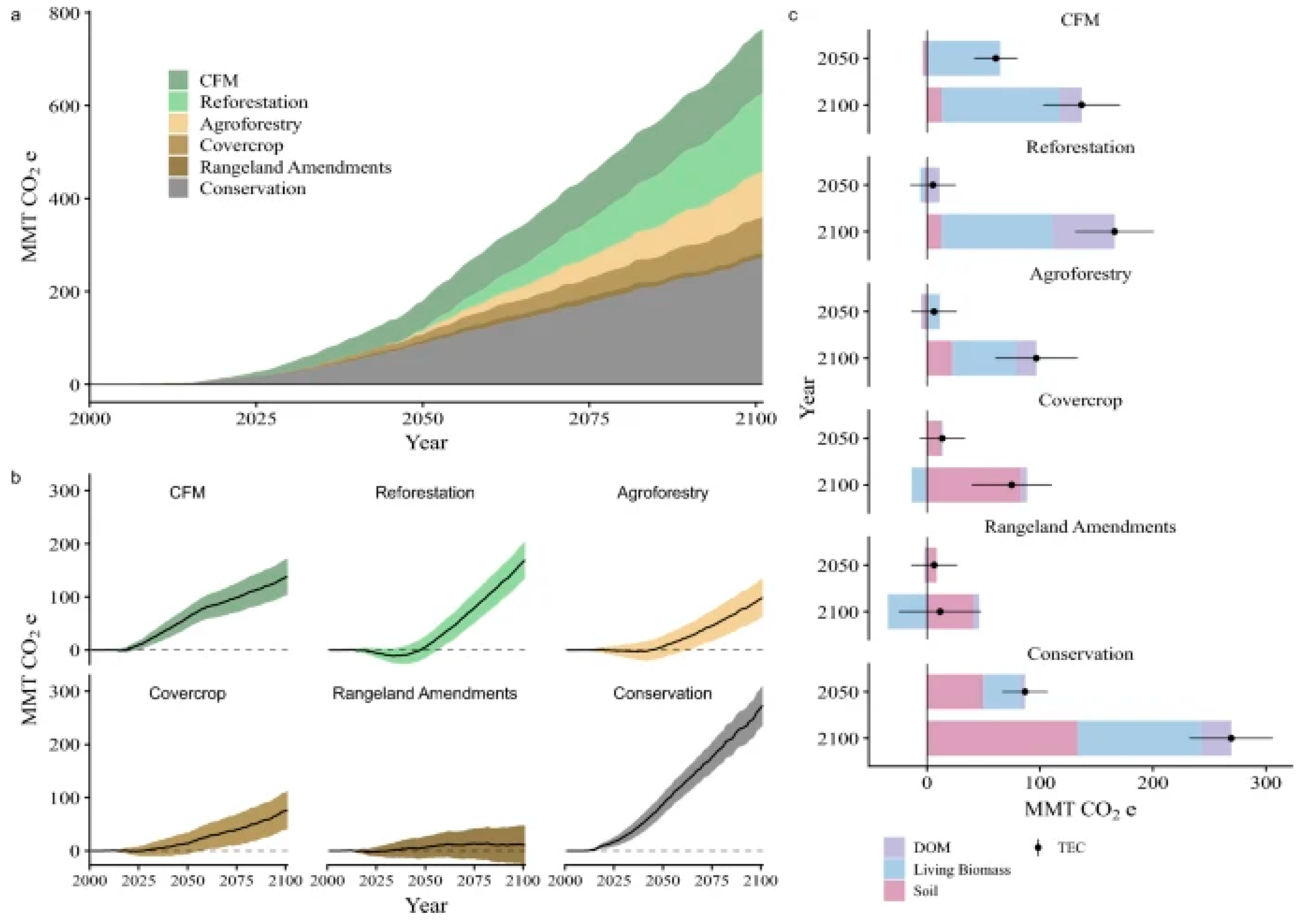

16. Agroforestry

17. Future Hints

18. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Andrews, S.; Karlen, D.; Cambardella, C. The soil management assessment framework: A quantitative soil quality evaluation method. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2004, 68, 1945–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouma, J.; McBratney, A. Framing soils as an actor when dealing with wicked environmental problems. Geoderma 2013, 201, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBratney, A.B.; Stockmann, U.; Angers, D.A.; Minasny, B.; Field, D.J. Challenges for soil organic carbon research. In Soil Carbon. Progress in Soil Science; Hartemink, A.E., McSweeney, K., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Meena, R.S.; Kumar, S.; Yadav, G.S. Soil Carbon Sequestration in Crop Production; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Lal, R. Soil carbon sequestration to mitigate climate change. Geoderma 2004, 123, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GLOBE. Carbon Cycle Project. 2010. Available online: https://kfrserver.natur.cuni.cz/globe/others.htm (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Naorem, A.; Jayaraman, S.; Dalal, R.C.; Patra, A.; Rao, C.S.; Lal, R. Soil inorganic carbon as a potential sink in carbon storage in dryland soils—A review. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Canadell, J.G.; Yu, L.; Yu, L.; Zhang, W.; Smith, P.; Fischer, T.; Huang, Y. Climate drives global soil carbon sequestration and crop yield changes under conservation agriculture. Glob. Change Biol. 2020, 26, 3325–3335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minasny, B.; McBratney, A.B.; Malone, B.P.; Lacoste, M.; Walter, C. Quantitatively predicting soil carbon across landscapes. In Soil Carbon. Progress in Soil Science; Hartemink, A.E., McSweeney, K., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Wei, F. Climate controls the global distribution of soil organic and inorganic carbon. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 175, 113514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, S.; Bhadoria, P.B.S.; Mandal, B.; Rakshit, A.; Singh, H.B. Soil organic carbon: Towards better soil health, productivity and climate change mitigation. Clim. Change Environ. Sustain. 2015, 3, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, R. Soil carbon management and climate change. In Progress in Soil Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Paustian, K.; Larson, E.; Kent, J.; Marx, E.; Swan, A. Soil C Sequestration as a Biological Negative Emission. Strategy Front. Clim. 2019, 1, 482133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrelli, P.; Robinson, D.A.; Panagos, P.; Lugato, E.; Yang, J.E.; Alewell, C.; Wuepper, D.; Montanarella, L.; Ballabio, C. Land use and climate change impacts on global soil erosion by water (2015–2070). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 17, 21994–22001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, D.A.; Panagos, P.; Borrelli, P.; Jones, A.; Montanarella, L.; Tye, A.; Obst, C.G. Soil natural capital in Europe; A framework for state and change assessment. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 6706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasarao, C.; Venkateswarlu, B.; Sudha Rani, Y.; Singh, A.K.; Dixit, S. Soil carbon sequestration with soil sanagement in three tribal villages in India. In Soil Carbon. Progress in Soil Science; Hartemink, A.E., McSweeney, K., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Borrelli, P.; Alewell, C.; Alvarez, P.; Anache, J.A.A.; Baartman, J.; Ballabio, C.; Bezak, N.; Biddoccu, M.; Cerdà, A.; Chalise, D.; et al. Soil erosion modelling: A global review and statistical analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 780, 146494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ontl, T.A.; Schulte, L.A. Soil carbon storage. Nat. Educ. Knowl. 2012, 3, 35. [Google Scholar]

- Bliss, N.B.; Waltman, S.W.; West, L.T.; Neale, A.; Mehaffey, M. Distribution of soil organic carbon in the conterminous United States. In Soil Carbon; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 85–93. [Google Scholar]

- Kirschbaum, M.U.F. The temperature dependence of soil organic matter decomposition, and the effect of global warming on soil organic C storage. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1995, 27, 753–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, C.; Paulino, L.; Monreal, C.; Zagal, E. Greenhouse gas (CO2 and N2O) emissions from soils: A review. Chil. J. Agric. Res. 2010, 70, 485–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, G.R.; Phillips-Housley, A.; Stevens, M.T. Soil-zone adsorption of atmospheric CO2 as a terrestrial carbon sink. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2013, 106, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Special Report. 1996. Available online: https://www.ipcc-nggip.iges.or.jp/public/gl/invs1.html (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- IPCC. AR5 Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. 2014. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/wg2/ (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- IPCC. AR5 Synthesis Report: Climate Change. 2014. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/syr/ (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Johnson, J.M.-F.; Franzluebbers, A.J.; Weyers, S.L.; Reicosky, D.C. Agricultural opportunities to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions. Environ. Pollut. 2007, 50, 107–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, R. Restoring soil quality to mitigate soil degradation sustainability. Sustainability 2015, 7, 5875–5895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dynarski, K.A.; Bossio, D.A.; Scow, K.M. Dynamic Stability of Soil Carbon: Reassessing the “Permanence” of Soil Carbon Sequestration. Front. Environ. Sci. 2020, 8, 514701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trumbore, S.E. Potential responses of soil organic carbon to global environmental change. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1997, 94, 8284–8291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paustian, K.; Andrén, O.; Janzen, H.; Lal, R.; Smith, P.; Tian, G.; Tiessen, H.; van Noordwijk, M.; Woomer, P. Agricultural soil as a C sink to offset CO2 emissions. Soil Use Manage 1997, 13, 230–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paustian, K.; Collins, H.P.; Paul, E.A. Management controls of soil carbon. In SOM in Temperate Agroecosystems: Long Term Experiments in North America; CRC Press Inc.: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1997; pp. 5–49. [Google Scholar]

- De Stefano, A.; Jacobson, M.G. Soil carbon sequestration in agroforestry systems: A meta-analysis. Agrofor. Syst. 2018, 92, 285–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Special Report Global Warming of 1.5 °C. 2021. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/ (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- IPCC. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. 2021. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/ (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Hakamata, T.; Matsumoto, N.; Ikeda, H.; Nakane, K. Do plant and soil systems contribute to global carbon cycling as a sink of CO2? Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 1997, 49, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canadell, J.G.; Schulze, E.D. Global potential of biospheric carbon management for climate mitigation. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 5282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Quéré, C.; Moriarty, R.; Andrew, R.M.; Canadell, J.G.; Sitch, S.; Korsbakken, J.I.; Friedlingstein, P.; Peters, G.P.; Andres, R.J.; Boden, T.A.; et al. Global carbon budget 2015. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2015, 7, 349–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Quéré, C.; Andrew, R.M.; Friedlingstein, P.; Sitch, S.; Hauck, J.; Pongratz, J.; Pickers, P.A.; Korsbakken, J.I.; Peters, G.P.; Canadell, J.G.; et al. Global carbon budget 2018. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2018, 10, 2141–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangroo, S.A.; Ali, T.; Mahdi, S.S.; Najar, G.R.; Sofi, J.A. Carbon and greenhouse gas mitigation through soil carbon sequestration potential of adaptive agriculture and agroforestry systems. Range Manag. Agrofor. 2013, 34, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, D.K.; Gupta, C.K.; Dubey, R.; Fagodiya, R.K.; Sharma, G.; Mohamed, M.B.N.; Dev, R.; Shukla, A.K. Role of biochar in carbon sequestration and greenhouse gas mitigation. In Biochar Applications in Agriculture and Environment Management; Singh, J.S., Singh, C., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 141–165. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner, C.; Gattinger, A.; Muller, A.; Mader, P.; Fliessbach, A.; Stolze, M.; Ruser, R.; Niggli, U. Greenhouse gas fluxes from agricultural soils under organic and non-organic management—A global meta- analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 468–469, 553–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seddon, N.; Chausson, A.; Berry, P.; Girardin, C.A.; Smith, A.; Turner, B. Understanding the value and limits of nature-based solutions to climate change and other global challenges. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 2020, 375, 20190120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paustian, K.; Babcock, B.; Hatfield, J.; Lal, R.; McCarl, B.; McLaughlin, S.; Mosier, A.; Rice, C.; Roberton, N.; Rosenberg, N.; et al. Agricultural Mitigation of Greenhouse Gases: Science and Policy Option; Council of Agricultural Science and Technology (CAST) Report, R 141 2004; CAST: Ames, IO, USA, 2004; p. 120. ISBN 1-887383-26-3. [Google Scholar]

- Abbas, F.; Hammad, H.M.; Ishaq, W.; Farooque, A.A.; Bakhat, H.F.; Zia, Z.; Fahad, S.; Farhad, W.; Cerdà, A. A review of soil carbon dynamics resulting from agricultural practices. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 268, 110319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galati, A.; Crescimanno, M.; Gristina, L.; Keesstra, S.; Novara, A. Actual provision as an alternative criterion to improve the efficiency of payments for ecosystem services for C sequestration in semiarid vineyards. Agric. Syst. 2016, 144, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oenema, O.; Velthof, G.; Kuikman, P. Technical and policy aspects of strategies to decrease greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosystems 2001, 60, 301–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oertel, C.; Matschullat, J.; Zurba, K.; Zimmermann, F.; Erasmi, S. Greenhouse gas emissions from soils—A review. Geochemistry 2016, 76, 327–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, R. Degradation and resilience of soils. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 1997, 352, 997–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrios, E.; Buresh, R.J.; Sprent, J.I. Organic matter in the soil particle size and density fractions from maize and legume cropping systems. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1996, 28, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellert, B.H.; Gregorich, E.G. Management-induced changes in the actively cycling fractions of soil organic matter. In Carbon Forms and Functions in Forest Soils; McFee, W.W., Kelly, J.M., Eds.; Soil Science Society of America: Madison, WI, USA, 1995; pp. 119–138. [Google Scholar]

- Bationo, A.; Kihara, J.; Vanlauwe, B.; Waswa, B.; Kimetu, J. Soil organic carbon dynamics, functions and management in West African agro-ecosystems. Agric. Syst. 2007, 94, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Wilson, B.; Ghoshal, S.; Senapati, N.; Mandal, B. Organic amendments influence soil quality and carbon sequestration in the Indo-Gangetic plains of India. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2012, 156, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, R. Soil carbon sequestration impacts on global climate change and food security. Science 2004, 304, 1623–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biederbeck, V.O.; Campbell, C.A.; Zentner, R.P. Effect of crop rotation and fertilization on some biological properties of a loam in southwestern Saskatchewan. Can. J. Soil Sci. 1984, 64, 355–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swift, R.S. Sequestration of C by soil. Soil Sci. 2001, 166, 858–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miltner, A.; Bombach, P.; Schmidt-Brücken, B.; Kästner, M. SOM genesis: Microbial biomass as a significant source. Biogeochemistry 2012, 111, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, L.; Barbosa, H.; Bhadwal, S.; Cowie, A.; Delusca, K.; Flores-Renteria, D.; Hermans, K.; Jobbagy, E.; Kurz, W.; Li, D.; et al. Land Degradation. In Climate Change and Land: An IPCC Special Report on Climate Change, Desertification, Land Degradation, Sustainable Land Management, Food Security, and Greenhouse Gas Fluxes in Terrestrial Ecosystems; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenland, D.J.; Szabolcs, I. (Eds.) Soil Resilience and Sustainable Land Use. In Proceedings of the Second Workshop on the Ecological Foundations of Sustainable Agriculture (WEFSA II), Budapest, Hungary, 28 September–2 October 1992; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhury, S.T.; Bhattacharyya, S.P.W.; Pal, D.K.; Sahrawat, K.L.; Chandran, P.; Venugopalan, M.V. Use and cropping effects on C in black soils of semi-arid tropical India. Curr. Sci. 2016, 110, 1652–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meena, R.S.; Meena, P.D.; Yadav, G.S.; Yadav, S.S. Phosphate solubilizing microorganisms, principles and application of microphos technology. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 145, 157–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordt, L.C.; Wilding, L.P.; Drees, L.R. Pedogenic carbonate transformations in leaching soil systems; implications for the global carbon cycle. In Global Climate Change and Pedogenic Carbonates; CRC/Lewis: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2000; pp. 43–64. [Google Scholar]

- Weil, R.R.; Brady, N.C. The Nature and Properties of Soils, 15th ed.; Pearson Press: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Monger, H.C.; Kraimer, R.A.; Khresat, S.; Cole, D.R.; Wang, X.; Wang, J. Sequestration of inorganic carbon in soil and groundwater. Geology 2015, 43, 375–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Six, J.; Conant, R.T.; Paul, E.A.; Paustian, K. Stabilization mechanisms of soil organic matter: Implications for C-saturation of soils. Plant Soil 2002, 241, 55–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, K.; Lal, R. Environmental impact of organic agriculture. Adv. Agron. 2016, 139, 99–152. [Google Scholar]

- Schlesinger, W.H. Carbon sequestration in soils: Some cautions amidst optimism. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2000, 82, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monger, H.C.; Cole, D.R.; Buck, B.J.; Gallegos, R.A. Scale and the isotopic record of C4 plants in pedogenic carbonate: From the biome to the rhizosphere. Ecology 2009, 90, 1498–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monger, H.C. Soils as a generator and sinks of inorganic Carbon in geologic time. In Soil Carbon. Progress in Soil Science; Hartemink, A.E., McSweeney, K., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gleixner, G. Soil organic matter dynamics: A biological perspective derived from the use of compound-specific isotopes studies. Ecol. Res. 2013, 28, 683–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandy, A.S.; Neff, J.C. Molecular C dynamics downstream: The biochemical decomposition sequence and its impact on soil organic matter structure and function. Sci. Total Environ. 2008, 404, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallenbach, C.M.; Frey, S.D.; Grandy, A.S. Direct evidence for microbial-derived soil organic matter formation and its ecophysiological controls. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 13630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopittke, P.M.; Dalal, R.C.; Hoeschen, C.; Li, C.; Menzies, N.W.; Mueller, C.W. Soil organic matter is stabilized by organo-mineral associations through two key processes: The role of the carbon to nitrogen ratio. Geoderma 2020, 357, 113974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaza, C.; Courtier-Murias, D.; Fernández, J.M.; Polo, A.; Simpson, A.J. Physical, chemical, and biochemical mechanisms of soil organic matter stabilization under conservation tillage systems: A central role for microbes and microbial by-products in C sequestration. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2013, 57, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, A.J.; Simpson, M.J.; Smith, E.; Kelleher, B.P. Microbially derived inputs to soil organic matter: Are current estimates too low? Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 42, 3115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebig, M.A.; Morgan, J.A.; Reeder, J.D.; Ellert, B.H.; Gollany, H.T.; Schuman, G.E. Greenhouse gas contributions and mitigation potential of agricultural practices in northwestern USA and western Canada. Soil Tillage Res. 2005, 83, 25–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pataki, D.E.; Ellsworth, D.S.; Evans, R.D.; Gonzalez-Meler, M.; King, J.; Leavitt, S.W.; Lin, G.; Matamala, R.; Pendall, E.; Siegwolf, R.; et al. Tracing changes in ecosystem function under elevated carbon dioxide conditions. Bioscience 2003, 53, 805–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gollany, H.T.; Schumacher, T.E.; Lindstrom, M.J.; Evenson, P.; Lemme, G.D. Topsoil thickness and desurfacing effects on properties and productivity of a typic argiustoll. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1992, 56, 220–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pikul, J.L.; Johnson, J.M.F.; Wright, S.F.; Caesar, T.; Ellsbury, M. Soil organic matter and aggregate stability affected by tillage. In Humic Substances: Molecular Details and Applications in Land and Water Conservation; Ghabbour, E.A., Davies, G., Eds.; Taylor and Francis: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 243–258. [Google Scholar]

- Six, J.; Bossuyt, H.; Degryze, S.; Denef, K. A history of research on the link between (micro)aggregates, soil biota, and soil organic matter dynamics. Soil Tillage Res. 2004, 79, 7–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tisdall, J.M.; Oades, J.M. Organic matter and water-stable aggregates in soils. J. Soil Sci. 1982, 33, 141–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tisdall, J.M. Formation of soil aggregates and accumulation of soil organic matter. In Structure and Organic Matter Storage in Agricultural Soils; Carter, M.R., Stewart, B.A., Eds.; CRC/Lewis Publishers: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1996; pp. 57–96. [Google Scholar]

- Charles, A.; Rochette, P.; Whalen, J.K.; Angers, D.A.; Chantigny, M.H.; Bertrand, N. Global nitrous oxide emission factors from agricultural soils after addition of organic amendments: A meta-analysis. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2017, 236, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cogger, C.; Fortuna, A.; Collins, D. Why the Concern About Nitrous Oxide Emissions? Available online: https://agclimate.net/greenhouse-gas-emissions/ (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- NSAC. Policy Imperatives and Opportunities to Help Producers Meet the Challenge 11/209. Available online: https://sustainableagriculture.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/NSAC-Climate-Change-Policy-Position_paper-112019_WEB.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Chataut, G.; Bhatta, B.; Joshi, D.; Subedi, K.; Kafle, K. Greenhouse gases emission from agricultural soil: A review. J. Agric. Food Res. 2023, 11, 100533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, S.O.; Regina, K.; Pöllinger, A.; Rigler, E.; Valli, L.; Yamulki, S.; Esala, M.; Fabbri, C.; Syväsalo, E.; Vinther, F.P. Nitrous oxide emissions from organic and conventional crop rotation in five European countries. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2006, 112, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Factors Regulating Nitrous Oxide and Nitric Oxide Emission. Global Estimates of Gaseous Emissions of NH3, NO and N2O from Agricultural Land; International Fertilizer Industry Association: Paris, France; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO): Rome, Italy, 2001; pp. 11–20. ISBN 92-5-104689-1. [Google Scholar]

- Burger, M.; Jackson, L. Microbial immobilization of ammonium and nitrate in relation to ammonification and nitrification rates in organic and conventional cropping systems. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2003, 35, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baas, D.G.; Robertson, G.P.; Miller, S.R.; Millar, N. Effects of Cover Crops on nitrous oxide emissions, nitrogen availability, and carbon accumulation in organic versus conventionally managed systems. Final report for ORG project. Cellulose 2011, 4, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, L. Soil Microbial Nitrogen Cycling for Organic Farms. 2010. Available online: https://eorganic.org/node/3227 (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Li, C.; Salas, W.; Muramoto, J. Process based models for optimizing N management in California cropping systems: Application of DNDC model for nutrient management for organic broccoli production. In Proceedings of the California Soil and Plant Conference—Conference Proceedings 2009, Fresno, CA, USA, 10–11 February 2009; pp. 92–98. [Google Scholar]

- Cavigelli, M. Impact of Organic Grain Farming Methods on Climate Change (Webinar). 2010. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5hgTeyjJ_t4 (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Reinbott, T. Identification of Factors Affecting Carbon Sequestration and Nitrous Oxide Emissions in Three Organic Cropping Systems. Final Report on ORG Project 2011-04958. CRIS Abstracts. 2015. Available online: https://hub.ofrf.org/repository/identifying-factors-in-carbon-sequestration-and-nitrous-oxide-emission-in-three-organic-cropping-systems (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Lin, B.B.; Chappell, M.J.; Vandermeer, J.; Smith, G.; Quintero, E.; Bezner-Kerr, R.; Griffith, D.M.; Ketcham, S.; Latta, S.C.; McMichael, P.; et al. Effects of industrial agriculture on climate change and the mitigation potential of small-scale agro-ecological farms. CAB Rev. 2011, 6, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakelin, S.A.; Gregg, A.L.; Simpson, R.J.; Li, G.D.; Riley, I.T.; Mckay, A.C. Pasture management clearly affects soil microbial community structure and N-cycling bacteria. Pedobiologia 2009, 52, 237–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, A.S.K.; Parkin, T.B. Effect of land use on methane flux from soil. J. Environ. Qual. 2001, 30, 786–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregorich, E.G.; Rochette, P.; VandenBygaart, A.J.; Angers, D.A. Greenhouse gas contributions of agricultural soils and potential mitigation practices in Eastern Canada. Soil Tillage Res. 2005, 83, 53–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLain, J.E.T.; Martens, D.A. Moisture controls on trace gas fluxes in semiarid riparian soils. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2006, 70, 367–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.Y.; Heenan, D.P. Effect of lime (CaCO3) application on soil structural stability of a red earth. Aust. J. Soil Res. 1998, 36, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reay, D.; Smith, K.; Hewitt, C. Methane: Importance, sources and sinks. In Greenhouse Gas Sinks; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 2007; pp. 143–151. [Google Scholar]

- Poesen, J. Soil erosion in the Anthropocene: Research needs. Earth Surf. Process. Landforms 2018, 84, 64–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, M.; Sun, R.; Chen, L. A global comparison of soil erosion associated with land use and climate type. Geoderma 2019, 343, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paustian, K.; Lehmann, J.; Ogle, S.; Reay, D.; Robertson, G.P.; Smith, P. Climate-smart soils. Nature 2016, 532, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lal, R. Soil erosion and gaseous emissions. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 2784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anache, J.A.A.; Wendland, E.C.; Oliveira, P.T.S.; Flanagan, D.C.; Nearing, M.A. Runoff and soil erosion plot-scale studies under natural rainfall: A meta-analysis of the Brazilian experience. Catena 2017, 152, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auerswald, K.; Fiener, P.; Dikau, R. Rates of sheet and rill erosion in Germany—A meta-analysis. Geomorphology 2009, 111, 182–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrelli, P.; Robinson, D.A.; Fleischer, L.R.; Lugato, E.; Ballabio, C.; Alewell, C.; Muesburger, K.; Modugno, S.; Schütt, B.; Ferro, V.; et al. An assessment of the global impact of 21st century land use change on soil erosion. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Ruiz, J.M.; Begueria, S.; Lana-Renault, N.; Nadal-Romero, E.; Cerda, A. Ongoing and emerging questions in water erosion studies. Land Degrad. Dev. 2017, 28, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, R. Soil erosion and carbon dynamics. Soil Tillage Res. 2005, 81, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pendall, E.; Rustad, L.; Schimel, J. Towards a predictive understanding of belowground process responses to climate change: Have we moved any closer? Funct. Ecol. 2008, 22, 937–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocci, K.S.; Lavallee, J.M.; Stewart, C.E.; Cotrufo, M.F. Soil organic carbon response to global environmental change depends on its distribution between mineral-associated and particulate organic matter: A meta-analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 793, 148569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.V.; Renwick, W.H.; Buddemeier, R.W.; Crossland, C.J. Budgets of soil erosion and deposition for sediments and sedimentary organic carbon across the conterminous United States. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2001, 15, 697–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugato, E.; Smith, P.; Borrelli, P.; Panagos, P.; Ballabio, C.; Orgiazzi, A.; Fernandez-Ugalde, O.; Montanarella, L.; Jones, A. Soil erosion is unlikely to drive a future carbon sink in Europe. Sci. Adv. 2018, 4, eaau3523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, H.; Li, Z.; Chang, X.; Huang, B.; Nie, X.; Liu, C.; Liu, L.; Wang, D.; Jiang, J. The mineralization and sequestration of organic carbon in relation to agricultural soil erosion. Geoderma 2018, 329, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dick, W.A.; Gregorich, E.G. Developing and maintaining soil organic matter levels. In Managing Soil Quality: Challenges in Modern Agriculture; Schjonning, P., Elmholt, S., Christensen, B.T., Eds.; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 2004; pp. 103–120. [Google Scholar]

- Shakoor, A.; Shahbaz, M.; Hassan, T.; Sahar, N.E.; Muhammad, S.; Mohsin, M.; Ashraf, M. A global meta-analysis of greenhouse gases emission and crop yield under no- tillage as compared to conventional tillage. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 750, 142299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; McLaughlin, N.; Zhang, X.; Xu, M.; Liang, A. Effect of tillage and crop residue on soil temperature following planting for a Black soil in Northeast China. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 4500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Oost, K.; Govers, G.; Quine, T.A.; Heckrath, G. Comment on “Managing Soil Carbon”. Science 2004, 305, 1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Six, J.; Elliott, E.T.; Paustian, K.; Doran, J.W. Aggregation and soil organic matter accumulation in cultivated and native grassland soils. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1998, 62, 1367–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, W.M.; Emanuel, W.R.; Zinke, P.J.; Stangenberger, A.G. Soil carbon pools and world life zones. Nature 1982, 298, 156–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, W.M.; Pastor, J.; Zinke, P.J.; Stangenberger, A.G. Global patterns of soil nitrogen storage. Nature 1985, 317, 613–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaver, G.R.; Billings, W.D.; Chapin, F.S.I.I.I.; Giblin, A.E.; Nadelhoffer, K.J.; Oechel, W.C.; Rastetter, E.B. Global change and the carbon balance of arctic ecosystems. Bioscience 1992, 42, 433–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, W.F.; Wiedmann, T.; Pongratz, J.; Andrew, R.; Crippa, M.; Olivier, J.G.D.; Wiedenhofer, D.; Mattioli, G.; Al Khourdajie, A.; House, J.; et al. A review of trends and drivers of greenhouse gas emissions by sector from 1990 to 2018. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 073005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, T.L. The potential of nature-based solutions to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from US agriculture. Socio-Ecol. Pract. Res. 2022, 4, 251–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

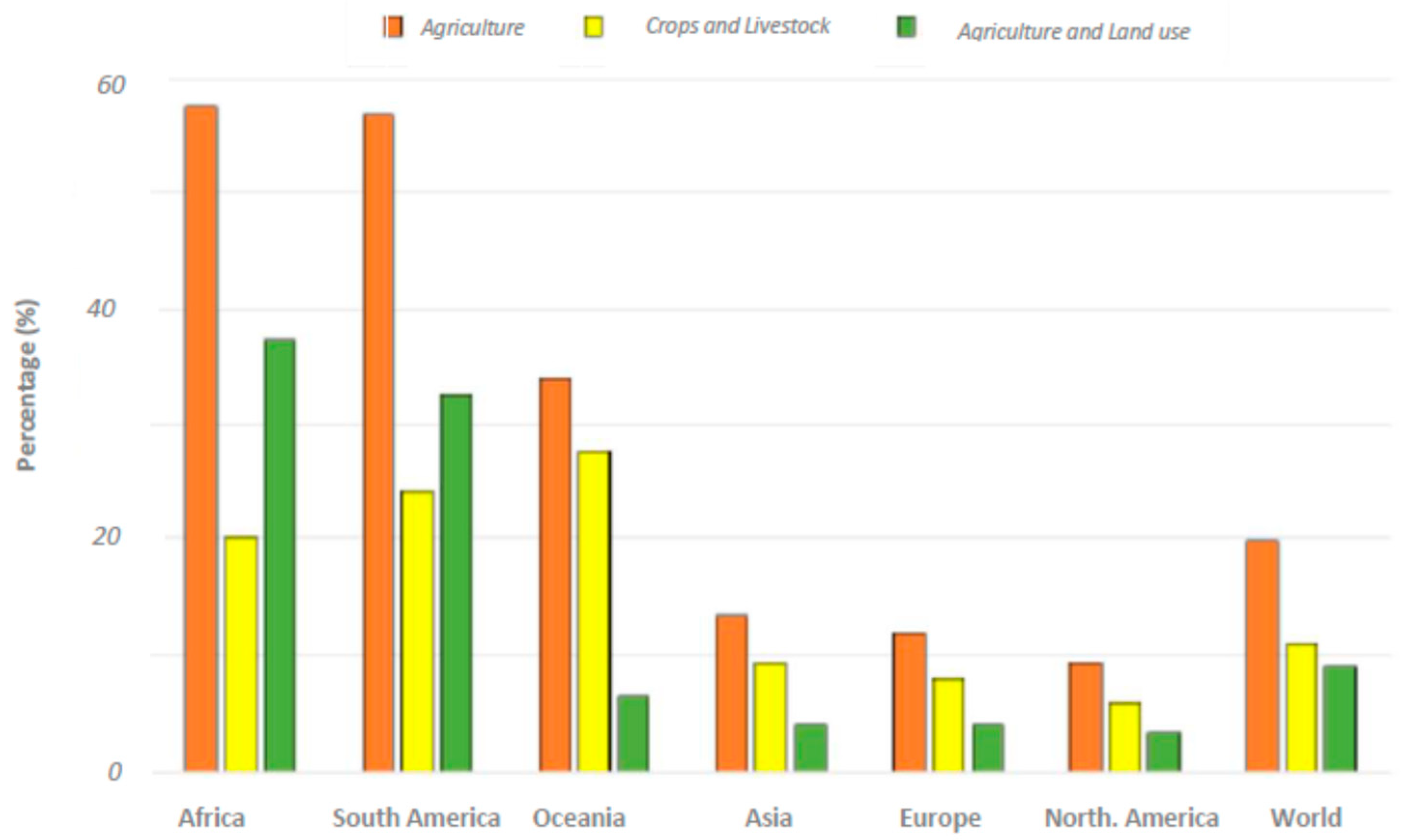

- FAO. The Share of Food Systems in Total Greenhouse Gas Emissions. Global, Regional and Country Trends, 1990–2019. FAOSTAT Analytical Brief Series No. 31. Rome. 2021. Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/ffb21ed0-05dd-46b1-b16c-50c9d47a6676/content (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Frank, S.; Havlík, P.; Soussana, J.F.; Levesque, A.; Valin, H.; Wollenberg, E.; Kleinwechter, U.; Fricko, O.; Gusti, M.; Herrero, M.; et al. Reducing greenhouse gas emissions in agriculture without compromising food security? Environ. Res. Lett. 2017, 12, 105004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valkama, E.; Kunypiyaeva, G.; Zhapayev, R.; Karabayev, M.; Zhusupbekov, E.; Perego, A.; Schillaci, C.; Sacco, D.; Moretti, B.; Grignani, C.; et al. Can conservation agriculture increase soil carbon sequestration? A modelling approach. Geoderma 2020, 369, 114298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

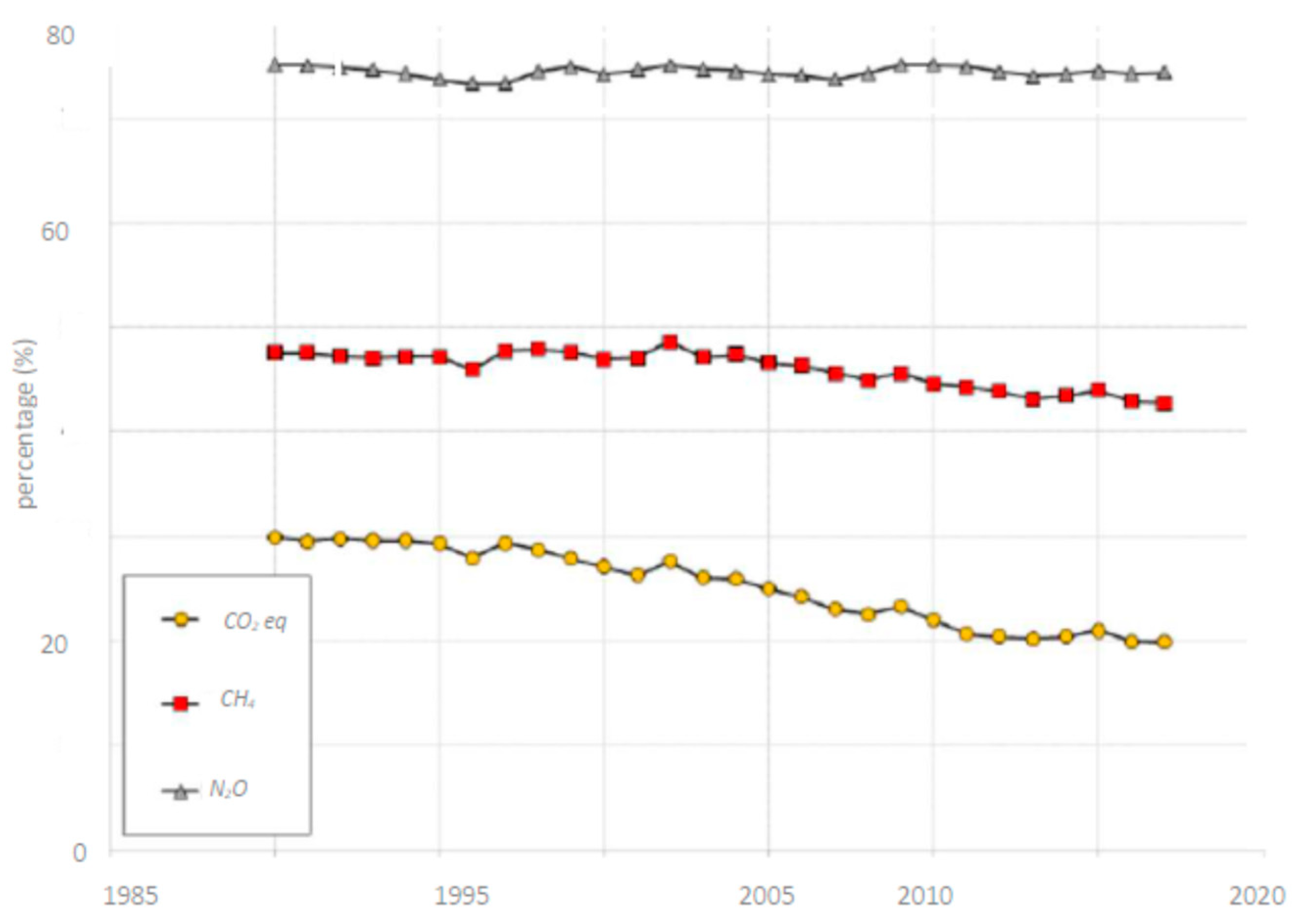

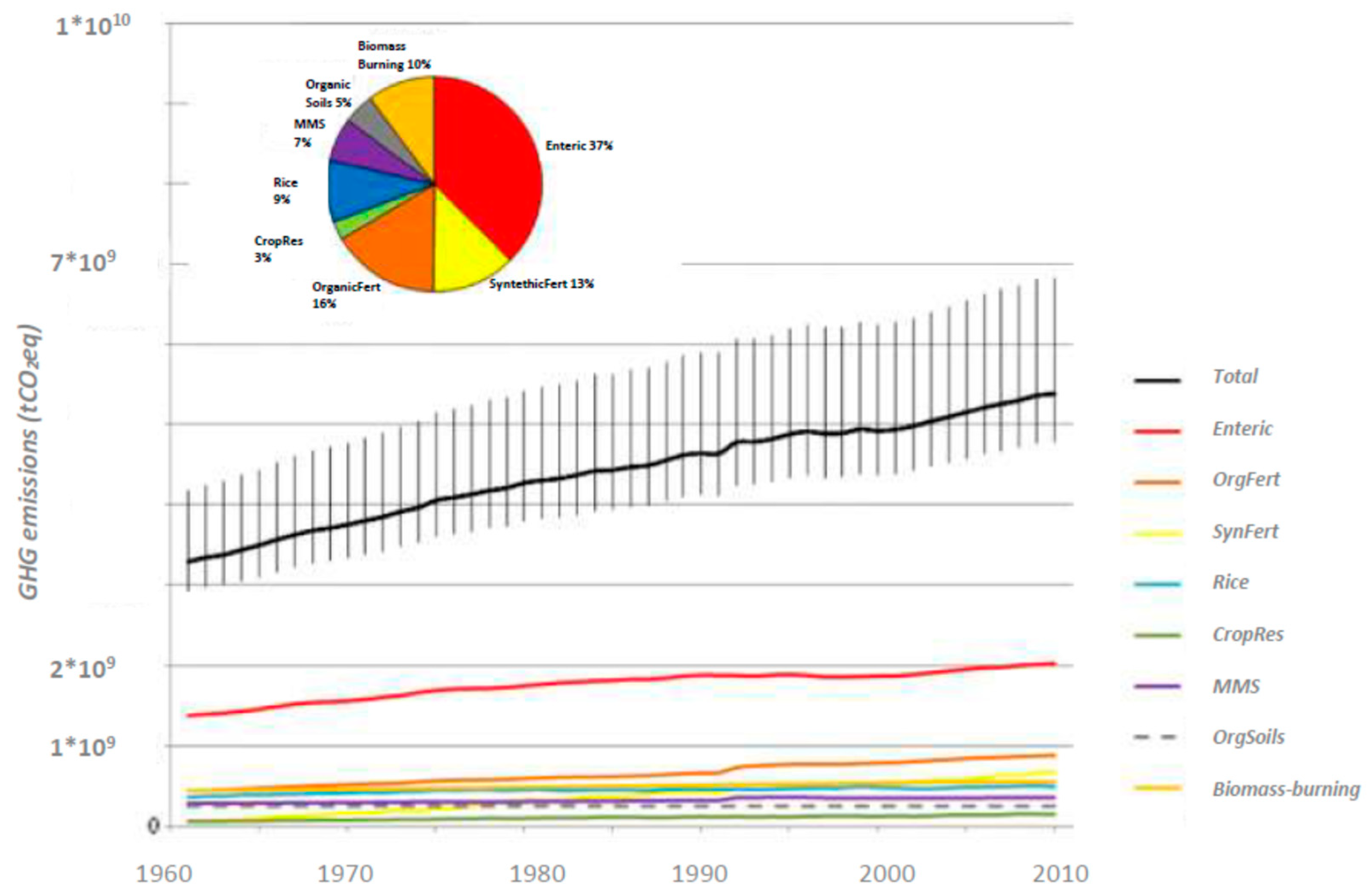

- Tubiello, F.N.; Salvatore, M.; Rossi, S.; Ferrara, A.; Fitton, N.; Smith, P. The FAOSTAT database of greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture. Environ. Res. Lett. 2013, 8, 015009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Follett, R.F.; Kimble, J.M.; Lal, R. The Potential of U.S. Grazing Lands to Sequester Soil Carbon and Mitigate the Greenhouse Effect; Lewis Publishers: London, UK, 2001; imprint of CRC Press LLC: Boca Raton, FL, USA; pp. 401–430. [Google Scholar]

- Matteucci, G.; Dore, S.; Rebmann, C.; Stivanello, S.; Buchmann, N. Soil respiration in beech and spruce forest in Europe: Trends, controlling factors, annual budgets and implications for the ecosystem carbon balance. In Carbon and Nitrogen Cycling in European Forest Ecosystems; Schulze, E.D., Ed.; Springer Verlag: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2000; pp. 217–236. [Google Scholar]

- Schonbeck, M.D.J.; Snyder, L. Soil Health and Organic Farming: Organic Practices for Climate Mitigation, Adaptation, and Carbon Sequestration; Organic Farming Research: Santa Cruz, CA, USA, 2018; 78p. [Google Scholar]

- Yohannes, H. A review on relationship between climate change and agriculture. J. Earth Sci. Clim. Change 2016, 7, 335. [Google Scholar]

- Rodale Inst. Farming Systems Trial Brochure. 2015. Available online: https://rodaleinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/farming-systems-trial.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Available online: https://www.fao.org/soils-portal/data-hub/soil-maps-and-databases/global-soil-organic-carbon-sequestration-potential-gsocseq-map/en/ (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Blanco-Canqui, H.; Lal, R. Soil and Water Conservation. In Principles of Soil Conservation and Management; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Havlin, J.L.; Kissel, D.E.; Maddus, L.D.; Claassen, M.M.; Long, J.H. Crop rotation and tillage effects on soil organic carbon and nitrogen. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1990, 54, 448–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulumba, L.N.; Lal, R. Mulching effects on selected soil physical properties. Soil Tillage Res. 2008, 98, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saroa, G.S.; Lal, R. Soil restorative effects of mulching on aggregation and carbon sequestration in a Miamian soil in Central Ohio. Land Degrad. Dev. 2003, 14, 481–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, R. Beyond COP21: Potential challenges of the “4 per thousand” initiative. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2016, 71, 20A–25A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, R.; Follett, R.F.; Kimble, J.M. Achieving Soil Carbon Sequestration in the U.S.: A challenge to the policymakers. Soil Sci. 2003, 168, 827–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalantari, Z.; Ferreira, C.S.S.; Deal, B.; Destouni, G. Nature-based solutions for meeting environmental and socio-economic challenges in land management and development Land. Degrad. Dev. 2019, 31, 1867–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKinnon, K.; Sobrevila, C.; Hickey, V. Biodiversity, Climate Change and Adaptation: Nature-Based Solutions from the Word Bank Portfolio; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Mittermeier, R.; Totten, M.; Pennypacker, L.L.; Boltz, F. A Climate for Life: Meeting the Global Challenge; International League of Conservation Photographers: Arlington, VA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Sowińska-Świerkosz, B.; García, J. What are Nature-based solutions (NBS)? Setting core ideas for concept clarification. Nat. Based Solut. 2022, 2, 100009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seddon, N.; Smith, A.; Smith, P.; Key, I.; Chausson, A.; Girardin, C.; House, J.; Srivastava, S.; Turner, B. Getting the message right on nature-based solutions to climate change. Glob. Change Biol. 2021, 27, 1518–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adil, M.; Yao, Z.; Zhang, C.; Lu, S.; Fu, S.; Mosa, W.F.; Hasan, M.E.; Lu, H. Climate change stress alleviation through nature-based solutions: A global perspective. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1007222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debele, S.E.; Leo, L.S.; Kumar, P.; Sahani, J.; Ommer, J.; Bucchignani, E.; Vranić, S.; Kalas, M.; Amirzada, Z.; Pavlova, I.; et al. Nature-based solutions can help reduce the impact of natural hazards: A global analysis of NBS case studies. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 902, 165824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, A.; Hilberg, L.E.; Hansen, L.J.; Stein, B.A. Key considerations for the use of nature-based solutions in climate services and adaptation. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favretto, N.; Stringer, L.C.; Dougill, A.J.; Dallimer, M.; Perkins, J.S.; Reed, M.S.; Mulale, K. Multi- Criteria Decision Analysis to identify dryland ecosystem service trade-offs under different rangeland land uses. Ecosyst. Serv. 2016, 17, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keesstra, S.; Nunes, J.; Novara, A.; Finger, D.; Avelar, D.; Kalantari, Z.; Cerdà, A. The superior effect of nature based solutions in land management for enhancing ecosystem services. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 610–611, 997–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, K.G.; Anderson, S.; Gonzales-Chang, M.; Costanza, R.; Courville, S.; Dalgaard, T.; Ratna, N. A review of methods, data, and models to assess changes in the value of ecosystem services from land degradation and restoration. Ecol. Model. 2016, 319, 190–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonneveld, B.G.J.S.; Merbis, M.D.; Alfarra, A.; Unver, I.H.O.; Arnal, M.F. Nature-Based Solutions for Agricultural Water Management and Food Security; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Eggermont, H.; Balian, E.; Azevedo, J.M.N.; Beumer, V.; Brodin, T.; Claudet, J.; Fady, B.; Grube, M.; Keune, H.; Lamarque, P.; et al. Nature-based solutions: New influence for environmental management and research in Europe. GAIA Ecol. Perspect. Sci. Soc. 2015, 24, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, L.K.; Manning, D.A. Soil health and related ecosystem services in organic agriculture. Sustain. Agric. Res. 2015, 4, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chenu, C.; Hassink, J.; Bloem, J. Short-term changes in the spatial distribution of microorganisms in soil aggregates as affected by glucose addition. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2001, 34, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen-Shacham, E.; Walters, G.; Janzen, C.; Maginnis, S. Nature-Based Solutions to Address Global Societal Challenges; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Miralles-Wilhelm, F. Management and Conservation of Land, Water and Biodiversity; FAO: Rome, Italy; The Nature Conservancy: Arlington, VA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenstock, T.S.; Rohrbach, D.; Nowak, A.; Girvetz, E. An Introduction to the Climate-Smart Agriculture Papers. In The Climate-Smart Agriculture Papers: Investigating the Business of a Productive, Resilient and Low Emission Future; Rosenstock, T.S., Nowak, A., Girvetz, E., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z.; Oshunsanya, S.O.; Li, Y.; Yu, H.; Ar, K.S. Vetiver grass hedgerows significantly trap P but little N from sloping land: Evidenced from a 10-year field observation. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2019, 281, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Livestock Report 2006; Animal Production and Health Division, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ewel, J.J. Natural systems as models for the design of sustainable systems of land use. Agrofor. Syst. 1999, 45, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruun, T.B.; de Neergaard, A.; Lawrence, D.; Ziegler, A.D. Environmental consequences of the demise in swidden cultivation in Southeast Asia: Carbon storage and soil quality. Hum. Ecol. 2009, 37, 375–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montagnini, F.; Nair, P.K.R. Carbon sequestration: An underexploited environmental benefit of agroforestry systems. Agrofor. Syst. 2004, 61, 281–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altieri, M.A.; Nicholls, C.I.; Henao, A.; Lana, M.A. Agroecology and the design of climate change-resilient farming systems. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2015, 35, 869–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamburini, G.; Bommarco, R.; Wanger, T.C.; Kremen, C.; van der Heijden, M.G.A.; Liebman, M.; Hallin, S. Agricultural diversification promotes multiple ecosystem services without compromising yield. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaba1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vignola, R.; Harvey, C.A.; Bautista-Solis, P.; Avelino, J.; Rapidel, B.; Donatti, C.; Martinez, R. Ecosystem-based adaptation for smallholder farmers: Definitions, opportunities and constraints. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2015, 211, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CBD. The Ecosystem Approach: COP 5 Decision V/6. Retired sections: Paragraphs 4–5. In Proceedings of the Fifth Meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity—Convention on Biological Diversity, Nairobi, Kenya, 15–26 May 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Griscom, B.W.; Busch, J.; Cook-Patton, S.C.; Ellis, P.W.; Funk, J.; Leavitt, S.M.; Lomax, G.; Turner, W.R.; Chapman, M.; Engelmann, J.; et al. National mitigation potential from natural climate solutions in the tropics. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2020, 375, 20190126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutchinson, J.J.; Campbell, C.A.; Desjardins, R.L. Some perspectives on carbon sequestration in agriculture. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2007, 142, 288–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Action Aid. The Time Is NOW: Lessons from Farmers Adapting to Climate Change; Action Aid: Johannesburg, South Africa, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Marvin, D.C.; Sleeter, B.M.; Cameron, D.R.; Nelson, E.; Plantinga, A.J. Natural climate solutions provide robust carbon mitigation capacity under future climate change scenarios. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 19008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griscom, B.W.; Adams, J.; Ellis, P.W.; Houghton, R.A.; Lomax, G.; Miteva, D.A.; Schlesinger, W.H.; Shoch, D.; Siikamäki, J.V.; Smith, P.; et al. Natural climate solutions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 11645–11650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chausson, A.; Turner, C.B.; Seddon, D.; Chabaneix, N.; Girardin, C.A.J.; Key, I.; Smith, A.C.; Woroniecki, S.; Seddon, N. Mapping the effectiveness of Nature-based solutions for climate change adaptation. Glob. Change Biol. 2020, 26, 6134–6155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, C.; Zhao, W.; Pereira, P. Soil conservation service underpins sustainable development goals. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2022, 33, e01974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burras, C.L.; Kimble, J.; Lal, R.; Mausbach, M.J.; Uehara, G. Carbon Sequestration: Position of the Soil Science Society of America. Available online: https://www.csuchico.edu/regenerativeagriculture/_assets/documents/carbon-sequestration-paper.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Liang, X.; Yu, S.; Ju, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yin, D. Integrated management practices foster soil health, productivity, and agroecosystem resilience. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, R.; Griffin, M.; Apt, J.; Lave, L.; Morgan, M.G. Managing Soil Carbon. Science 2004, 304, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Frolking, S.; Butterbach-Bahl, K. Carbon sequestration in arable soils is likely to increase nitrous oxide emissions, offsetting reductions in climate radiative forcing. Clim. Change 2005, 72, 321–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.A.; Conen, F. Impacts of land management on fluxes of trace greenhouse gases. Soil Use Manag. 2004, 20, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marland, G.; McCarl, B.A.; Schneider, U.A. Soil carbon: Policy and economics. Clim. Change 2001, 51, 101–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleischer, S.; Bouse, I. Nitrogen cycling drives a strong within-soil CO2-sink. Tellus 2008, 60B, 782–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Monreal, C.M.; Schulten, H.-R.; Kodama, H. Age, turnover and molecular diversity of soil organic matter in aggregates of a Gleysol. Can. J. Soil Sci. 1997, 77, 379–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piao, S.; Fang, J.; Ciais, P.; Peylin, P.; Huang, Y.; Sitch, S.; Wang, T. The carbon balance of terrestrial ecosystems in China. Nature 2010, 458, 1009–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oades, J.M.; Waters, A.G. Aggregate hierarchy in soils. Aust. J. Soil Res. 1991, 29, 815–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woomer, P.L.; Martin, A.; Albrecht, A.; Resck, D.V.S.; Scharpenseel, H.W. The importance and management of soil organic matter in the tropics. In The Biological Management of Tropical Soil Fertility; Woomer, P.L., Swift, M.J., Eds.; Wiley: Oxford, UK, 1993; pp. 47–80. [Google Scholar]

- Matus, F.; Amigo, X.; Kristiansen, S.M. Aluminum stabilization controls organic carbon levels in Chilean volcanic soils. Geoderma 2006, 132, 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, C.; Ovalle, C.; Zagal, E. Distribution of soil organic carbon stock in an Alfisol profile in Mediterranean Chilean ecosystems. Rev. Cienc. Suelo Nutr. Veg. 2007, 7, 15–27. [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury, S.; Bolan, N.; Farrell, M.; Sarkar, B.; Sarker, J.R.; Kirkham, M.B.; Hossain, M.Z.; Kim, G.H. Role of cultural and nutrient management practices in carbon sequestration in agricultural soil. Adv. Agron. 2021, 166, 131–196. [Google Scholar]

- Hobbs, P.R.; Sayre, K.; Gupta, R. The role of conservation agriculture in sustainable agriculture. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 2008, 363, 543–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, A.Y.Y.; Six, J.; Bryant, D.C.; Denison, R.F.; van Kessel, C. The relationship between carbon input, aggregation, and soil organic carbon stabilization in sustainable cropping systems. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2005, 69, 1078–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helfrich, M.; Ludwig, B.; Buurman, P.; Flessa, H. Effect of land use on the composition of soil organic matter in density and aggregate fractions as revealed by solid state 13C NMR spectroscopy. Geoderma 2006, 136, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meena, R.S.; Gogaoi, N.; Kumar, S. Alarming issues on agricultural crop production and environmental stresses. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 3357–3359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, R. Residue management, conservation tillage and soil restoration for mitigating greenhouse effect by CO2-enrichment. Soil Tillage Res. 1997, 43, 81–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.Y.; Heenan, D.P. Lime-induced loss of soil organic carbon and effect on aggregate stability. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1999, 63, 1841–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jastrow, J.D. Soil aggregate formation and the accrual of particulate and mineral-associated organic matter. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1996, 28, 665–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saggar, S.; Parshotam, A.; Sparling, G.P.; Feltham, C.W.; Hart, P.B.S. 14C-labeled ryegrass turnover and residence times in soils varying in clay content and mineralogy. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1996, 28, 1677–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, B.T. Physical fractionation of soil and structural and functional complexity in organic matter turnover. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2001, 52, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, B.M.; Singh, B.R.; Situala, B.K.; Lal, R.; Bajracharya, R.M. Soil aggregate and particle-associated organic carbon under different land uses in Nepal. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2007, 71, 1194–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Six, J.; Elliott, E.T.; Paustian, K. Soil macroaggregate turnover and microaggregate formation: A mechanism for C sequestration under no-tillage agriculture. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2000, 32, 2099–2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desjardins, T.; Volkoff, B.; Andreaux, F.; Cerri, C. Distribution du carbon total et de l’isotope 13C dans des sols ferrallitiques du Bresil. Sci. Sol 1991, 29, 175–187. [Google Scholar]

- Tiessen, H.; Cuevas, E.; Salcedo, I.H. Organic matter stability and nutrient availability under temperate and tropical conditions. In Towards Sustainable Land Use. Advances in GeoEcology; Catena Verlag: Reiskirchen, Germany, 1998; pp. 415–422. [Google Scholar]

- Balesdent, J.; Chenu, C.; Balabane, M. Relationship of soil organic matter dynamics to physical protection and tillage. Soil Tillage Res. 2000, 53, 215–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besnard, E.; Chenu, C.; Balesdent, J.; Puget, P.; Arrouays, D. Fate of particulate organic matter in soil aggregates during cultivation. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 1996, 47, 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skjemstad, J.O.; Clarke, P.; Taylor, J.A.; Oades, J.M.; McClure, S.G. The chemistry and nature of protected carbon in soil. Aust. J. Soil Res. 1996, 34, 251–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chantigny, M.H.; Angers, D.A.; Prévost, D.; Vézina, L.-P.; Chalifour, F.-P. Soil aggregation and fungal and bacterial biomass under annual and perennial cropping systems. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1997, 61, 262–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guggenberger, G.; Frey, S.D.; Six, J.; Paustian, K.; Elliott, E.T. Bacterial and fungal cell-wall residues in conventional and no-tillage agroecosystems. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1999, 63, 1188–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puget, P.; Angers, D.A.; Chenu, C. Nature of carbohydrates associated with water-stable aggregates of two cultivated soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1999, 31, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beare, M.H.; Hendrix, P.F.; Coleman, D.C. Water-stable aggregates and organic matter fractions in conventional- and no-tillage soils. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1994, 58, 777–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hediger, W. The non-permanence of optimal soil carbon sequestration. In Proceedings of the 83th Annual Conference of the Agricultural Economics Society, Dublin, Ireland, 30 March–1 April 2009; pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Sanderman, J.; Farquharson, R.; Baldock, J. Soil Carbon Sequestration Potential: A Review for Australian Agriculture; CSIRO: Canberra, Australia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, J.M.; Ochsner, T.E.; Venterea, R.T.; Griffis, T.J. Tillage and soil carbon sequestration: What do we really know? Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2007, 118, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, C.V.; Duxbury, J.; Freney, J.; Heinemeyer, O.; Minami, K.; Mosier, A.; Paustian, K.; Rosenberg, N.; Sampson, N.; Sauerbeck, D.; et al. Global estimates of potential mitigation of greenhouse gas emissions by agriculture. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 1997, 49, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duda, B.M.; Rusu, T.; Bogdan, I.; Pop, A.I.; Moraru, P.I.; Giurgiu, R.M.; Coste, C.L. Considerations Regarding the Opportunity of Conservative Agriculture in the Context of Global Warming. Res. J. Agric. Sci. 2014, 46, 210–217. [Google Scholar]

- Beare, M.H.; Pohland, B.R.; Wright, D.H.; Coleman, D.C. Residue placement and fungicide effects on fungal communities in conventional and no-tillage soils. Soil Sci. Sot. Am. J. 1993, 57, 392–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beam, M.H.; Hu, S.; Coleman, D.C.; Hendrix, P.F. Influence of mycelial fungi on aggregation and soil organic matter retention in conventional and no-tillage soil. Soil Sci. Sot. Am. J. 1997, 5, 211–219. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, W.M.; Shipitalo, M.J.; Owens, L.B.; Dick, W.A. Factors affecting preferential flow of water and atrazine through earthworm burrows under continuous no-till corn. J. Environ. Qual. 1993, 22, 453–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalal, R.C. Long-term effects of no-tillage, crop residue and nitrogen application on properties of a Vertisol. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1989, 53, 1511–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamblin, A.P. Changes in aggregate stability and associated organic matter properties after direct drilling and ploughing on some Australian soils. Aust. J. Soil Res. 1980, 18, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ike, I.P. Soil and crop responses to different tillage practices in a ferruginous soil in the Nigerian savanna. Soil Tillage Res. 1986, 6, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prove, B.G.; Loch, R.J.; Foley, J.L.; Anderson, V.J.; Younger, D.R. Improvements in aggregation and infiltration characteristics of a Krasnozem under maize with direct drill and stubble retention. Aust. J. Soil Res. 1990, 28, 577–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, R. Soil science and the carbon civilization. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2007, 71, 1425–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dendoncker, N.; Van Wesemael, B.; Rounsevell, M.D.A.; Roelandt, C.; Letten, S. Belgium’s CO2 mitigation potential under improved cropland management. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2004, 103, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freibauer, A.; Rounsevell, M.D.A.; Smith, P.; Verhagen, J. Carbon sequestration in the agricultural soils of Europe. Geoderma 2004, 122, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogle, S.M.; Alsaker, C.; Baldock, J.; Bernoux, M.; Breidt, F.J.; McConkey, B.; Regina, K.; Vazquez-Amabile, G.G. Climate and soil characteristics determine where no-till management can store carbon in soils and mitigate greenhouse gas emissions. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 11665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Sun, L.; Zhang, X.; Yang, B.; Wang, J.; Yin, B.; Yan, X.; Xiong, Z. Mitigation of nitrous oxide emissions from paddy soil under conventional and no-till practices using nitrification inhibitors during the winter wheat-growing season. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2013, 49, 627–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.F.; Chen, X.P.; Zhang, F.S.; Zhang, H.; Schroder, J.; Romheld, V. Fertilization and nitrogen balance in a wheat–maize rotation system in North China. J. Agron. 2006, 98, 938–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manela, A.P. Soil Carbon and the Mitigation of Flood Risks. In Soil Carbon Management: Economic, Environmental and Social Benefits; Kimble, J.M., Rice, C.W., Reed, D., Mooney, S., Follett, R.F., Lal, R., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Rawls, J.W.; Pachepsky, Y.A.; Ritchie, J.C.; Sobecki, T.M.; Bloodworth, H. Effects of Soil Organic Carbon on Soil Water Retention. Geoderma 2003, 116, 61–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, A. Ecosystem Services in the New York City Watershed. Ecosystem Marketplace. 2006. Available online: https://www.ecosystemmarketplace.com/articles/ecosystem-services-in-the-new-york-city-watershed-1969-12-31-2/ (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Vörösmarty, C.J.; Rodríguez Osuna, V.; Cak, A.D.; Bhaduri, A.; Bunn, S.E.; Corsi, F.; Gastelumendi, J.; Green, P.; Harrison, I.; Lawford, R.; et al. Ecosystem-based water security and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Ecohydrol. Hydrobiol. 2018, 18, 317–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westling, N.; Stromberg, P.M.; Swain, R.B. Can upstream ecosystems ensure safe drinking water—Insights from Sweden. Ecol. Econ. 2020, 169, 106552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawadzka, J.; Gallagher, E.; Smith, H.; Corstanje, R. Ecosystem services from combined natural and engineered water and wastewater treatment systems: Going beyond water quality enhancement. Ecol. Eng. 2019, 2, 100006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón Cendejas, J.; Ramírez, L.M.; Zierold, J.R.; Valenzuela, J.D.; Merino, M.; de Tagle, S.M.S.; Téllez, A.C. Evaluation of the impacts of land use in water quality and the role of nature-based solutions: A citizen science-based study. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDowell, R.W.; Noble, A.; Pletnyakov, P.; Mosley, L.M. Global database of diffuse riverine nitrogen and phosphorus loads and yields. Geosci. Data J. 2021, 8, 132–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorgoglione, A.; Gregorio, J.; Ríos, A.; Alonso, J.; Chreties, C.; Fossati, M. Influence of land use/land cover on surface-water quality of Santa Lucia River, Uruguay. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4692–4721. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Zhang, X.; Ma, J.; Han, B.; Li, W.; Zou, H.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, X. Impacts of irrigation methods on greenhouse gas emissions/absorptions from vegetable soils. J. Soils Sediments 2020, 20, 723–733. [Google Scholar]

- FAO; ITPS (Intergovernmental Technical Panel on Soils). Status of the World’s Soil Resources (SWSR)—Main Report; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Niggli, U.; Fließbach, A.; Hepperly, P.; Scialabba, N. Low Greenhouse Gas Agriculture: Mitigation and Adaptation Potential of Sustainable Farming Systems; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Poeplau, C.; Don, A. Carbon sequestration in agricultural soils via cultivation of cover crops—A meta- analysis. Agric Ecosyst Environ. 2015, 200, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Conservation Agriculture. 2017. Available online: http://www.fao.org/documents/card/en/c/981ab2a0-f3c6-4de3-a058-f0df6658e69f (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Pisante, M.; Stagnari, F.; Grant, C.A. Agricultural innovations for sustainable crop production intensification. Ital. J. Agron. 2012, 7, 300–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.B.; Gifford, R.M. Soil C stocks and land use change: A meta-analysis. Glob. Change Biol. 2002, 8, 345–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogle, S.M.; Breidt, F.J.; Eve, M.D.; Paustian, K. Uncertainty in estimating land use and management impacts on soil organic carbon storage for US agricultural lands between 1982 and 1997. Glob. Change Biol. 2003, 9, 1521–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, M.; Antoine, J.; Nachtergaele, F. Carbon Sequestration in Soils. Proposals for Land Management in Arid Areas of the Tropics; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, X.M.; Li, X.G.; Long, R.J.; Singh, B.P.; Li, Z.T.; Li, F.M. Dynamics of soil organic carbon and nitrogen associated with physically separated fractions in a grassland-cultivation sequence in the Qinghai–Tibetan plateau. Biol. Fert. Soils 2010, 46, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Söderström, B.; Hedlund, K.; Jackson, L.E.; Kätterer, T.; Lugato, E.; Thomsen, I.K.; Bracht Jørgensen, H. What are the effects of agricultural management on soil organic carbon (SOC) stocks? Environ. Evid. 2014, 3, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, G.S.; Lal, R.; Meena, R.S.; Babu, S.; Das, A.; Bhomik, S.N.; Datta, M.; Layak, J.; Saha, P. Conservation tillage and nutrient management effects on productivity and soil carbon sequestration under double cropping of rice in northeastern region of India. Ecol. Indic. 2017, 105, 303–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarecki, M.; Lal, R. Crop management for soil carbon sequestration. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2003, 22, 471–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purakayastha, T.J.; Bera, T.; Bhaduri, D.; Sarkar, B.; Mandal, S.; Wade, P.; Kumari, S.; Biswas, S.; Menon, M.; Pathag, H.; et al. A review on biochar modulated soil condition improvements and nutrient dynamics concerning crop yields: Pathways to climate change mitigation and global food security. Chemosphere 2019, 227, 345–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowles, M. Black carbon sequestration as an alternative to bioenergy. Biomass Bioenergy 2007, 31, 426–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, J.; Gaunt, J.; Rondon, M. Bio-char sequestration in terrestrial ecosystems—A review. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Clim. Change 2006, 11, 403–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffery, S.; Verheijen, F.G.A.; van der Velde, M.; Bastos, A.C. A quantitative review of the effects of biochar application to soils on crop productivity using meta-analysis. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2011, 144, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffery, S.; Verheijen, F.G.; Kammann, C.; Abalos, D. Biochar effects on methane emissions from soils: A meta-analysis. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2016, 101, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, J.; Joseph, S. (Eds.) Biochar for Environmental Management: Science and Technology; Routledge: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Majumder, S.; Neogia, S.; Duttaa, T.; Powelb, M.A.; Banik, P. The impact of biochar on soil carbon sequestration: Meta-analytical approach to evaluating environmental and economic advantages. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 250, 109466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.Y.; Xiong, Z.Q.; Kuzyakov, Y. Biochar stability in soil: Meta-analysis of decomposition and priming effects. Glob. Change Biol. Bioenergy 2016, 8, 512–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters, D.; Van Zwieten, L.; Singh, B.P.; Downie, A.; Cowie, A.L.; Lehmann, J. Biochar in soil for climate change mitigation and adaptation. In Soil Health and Climate Change. Soil Biology; Singh, B., Cowie, A., Chan, K., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; Volume 29. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, B.; Lehmann, J.; Solomon, D.; Sohi, S.; Thies, J.E.; Skjemstad, J.O.; Luizão, F.J.; Engelhard, M.H.; Neves, E.G.; Wirick, S. Stability of biomass-derived black carbon in soils. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2008, 72, 6069–6078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EBC. European Biochar Certificate—Guidelines for a Sustainable Production of Biochar; European Biochar Foundation (EBC): Arbaz, Switzerland, 2012; Available online: http://www.european-biochar.org/en/Download (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Gross, A.; Bromm, T.; Glaser, B. Soil organic carbon sequestration after biochar application: A global meta-analysis. Agronomy 2021, 11, 2474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmo, M.; Villar, R.; Salazar, P.; Alburquerque, J.A. Changes in soil nutrient availability explain biochar’s impact on wheat root development. Plant Soil. 2016, 399, 333–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Major, J.; Lehmann, J.; Rondon, M.; Goodale, C. Fate of soil-applied black carbon: Downward migration, leaching and soil respiration. Glob. Change Biol. 2010, 16, 1366–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, C.; Teixeira, W.G.; Lehmann, J.; Nehls, T.; de Macedo, J.L.V.; Blum, W.E.H.; Zech, W. Long term effects of manure, charcoal and mineral fertilization on crop production and fertility on a highly weathered central Amazonian upland soil. Plant Soil 2007, 291, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Cui, L.; Pan, G.; Li, L.; Hussain, Q.; Zhang, X.; Zheng, J.; Crowley, D. Effect of biochar amendment on yield and methane and nitrous oxide emissions from a rice paddy from Tai Lake plain, China. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2010, 139, 469–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chodak, M.; Niklińska, M. Effect of texture and tree species on microbial properties of mine soils. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2010, 46, 268–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Józefowska, A.; Pietrzykowski, M.; Woś, B.; Cajthaml, T.; Frouz, J. The effects of tree species and substrate on carbon sequestration and chemical and biological properties in reforested post-mining soils. Geoderma 2017, 292, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laganiere, J.; Angers, D.A.; Pare, D. Carbon accumulation in agricultural soils after afforestation: A meta-analysis. Glob. Change Biol. 2010, 16, 439–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tubiello, F.N.; Van Der Velde, M. Land and Water Use Options for Climate Change Adaptation and Mitigation in Agriculture; Solaw Background Thematic Report—Tr04a; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- IPCC. Land Use, Land-Use Change, and Forestry; A Special Report of the IPCC; Watson, R.T., Noble, I.R., Bolin, B., Ravindranath, N.H., Verardo, D.J., Dokken, D.J., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000; p. 375. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2018/03/srl-en-1.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2025).

| Methane | Nitrous Oxide | |

|---|---|---|

| Animal house | Modify feeding strategy Removal of a slurry from beneath the house | Modify feeding strategy Adopt a slurry-based system compared to a straw or deep litter system |

| Manure store | Cooling slurry; e.g., below the slatted floor Modify feeding strategy Removal of slurry from the slurry store Minimising slurry volume stored in summer months | Modify feeding strategy Keep anaerobic (e.g., cover and compact) Adopt a slurry-based system compared to a straw of deep litter-based system Add additional straw to immobilise ammonium-N |

| Land spreading | Cooling slurry Aerate solid manure heaps-composting Anaerobic digestion Enhancing crust formation Modify feeding strategy | Modify feeding strategy Nitrification and inhibition Spring application of slurry Integrate manure N with fertiliser N Slurry separation Solid manure application |

| Land use | Transformation Ecosystem resilience |

| Land cover | Forestlands, grasslands, barren lands, croplands, wetlands, other land covers |

| Vegetation | Age and type Distribution Leaf area index |

| Nutrients | C/N ratios Land use management Atmospheric deposition |

| Humidity | Soil water content (SWC) Water-filled pore space (WFPS) Precipitation/drought |

| Temperature | Radiation Exposure (Soil cover, exposition) Corg Soil colour (mineralogy) Wildfires |

| Agriculture category (MtCO2 eq/yr) | 1961 | 1990 | 2000 | 2005 | 2010 |

| Enteric fermentation | 1375 | 1875 | 1863 | 1947 | 2018 |

| Manure left on pasture | 386 | 578 | 682 | 731 | 764 |

| Synthetic fertiliser | 67 | 434 | 521 | 582 | 683 |

| Rice cultivation | 366 | 466 | 490 | 493 | 499 |

| Manure management | 284 | 319 | 348 | 348 | 353 |

| Crop residues | 66 | 124 | 129 | 142 | 151 |

| Manure applied to soils | 59 | 88 | 103 | 111 | 116 |

| Total (MtCO2 eq/yr) | 2604 | 3883 | 41,361 | 4354 | 4586 |

| Net deforestation | 4315 | 4296 | 3397 | 3374 | |

| Combined total | 8198 | 8432 | 7751 | 7960 |

| Type of Nature-based Solutions | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Green | Blue | Mixed (Green-Blue) | Hybrid (Green-Blue-Grey) |

| Urban parks | Ponds | Mangroves | Bioswales |

| Heritage parks | Wetlands | Vegetable wetlands | Rain gardens |

| Green strips | Rivers | Coral reefs | Green roof |

| Plains grass cover | Lakes and streams | Seagrass | Permeable surface channels |

| Trees and shrubs | Seas and oceans | Riparian buffer zones | Live pole drains |

| Forest orchard | Aquifer protection | Submerged dams or weirs | Live cribwalls |

| Hedges/shrubs/green fences | Room for the river | Beach nourishment | Live ground anchors, etc. |

| Street trees(s) | Constructed flood storage, etc. | ||

| Agroforestry Forest protection Reforestation Optimised forest Managements, etc. | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Corami, A.; Hursthouse, A. Nature-Based Solutions (NbS) in Agricultural Soils for Greenhouse Gas Mitigation. Agronomy 2026, 16, 360. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16030360

Corami A, Hursthouse A. Nature-Based Solutions (NbS) in Agricultural Soils for Greenhouse Gas Mitigation. Agronomy. 2026; 16(3):360. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16030360

Chicago/Turabian StyleCorami, Alessia, and Andrew Hursthouse. 2026. "Nature-Based Solutions (NbS) in Agricultural Soils for Greenhouse Gas Mitigation" Agronomy 16, no. 3: 360. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16030360

APA StyleCorami, A., & Hursthouse, A. (2026). Nature-Based Solutions (NbS) in Agricultural Soils for Greenhouse Gas Mitigation. Agronomy, 16(3), 360. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16030360