The PIN-LIKES Auxin Transport Genes Involved in Regulating Yield in Soybean

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Phylogenetic Analysis

2.2. Analysis and Visualization of Conserved Motifs and Phylogenetic Relationships in the Soybean PILS Gene Family

2.3. Analysis of Physicochemical Properties and Prediction of Subcellular Localization

2.4. Synteny Analysis of the GmPILS Genes

2.5. Analysis of Tissue Expression Patterns

2.6. qRT-PCR Analysis

2.7. Plant Material and Field Management

2.8. Population Genetic Analysis

2.9. Haplotype Analysis

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Superior Seed Submergence Tolerance in Cultivated Variety SN14 Compared to Wild Variety ZYD00006

3.2. The Predictions of Physicochemical Properties and Subcellular Localization of Soybean GmPILSs

3.3. Chromosomal Distribution and Synteny Analysis of GmPILSs

3.4. The Expression Pattern Analysis of GmPILS Genes in Soybean

3.5. Population Genetic Analysis and Haplotype Analysis of Yield Candidate Gene GmPILS40

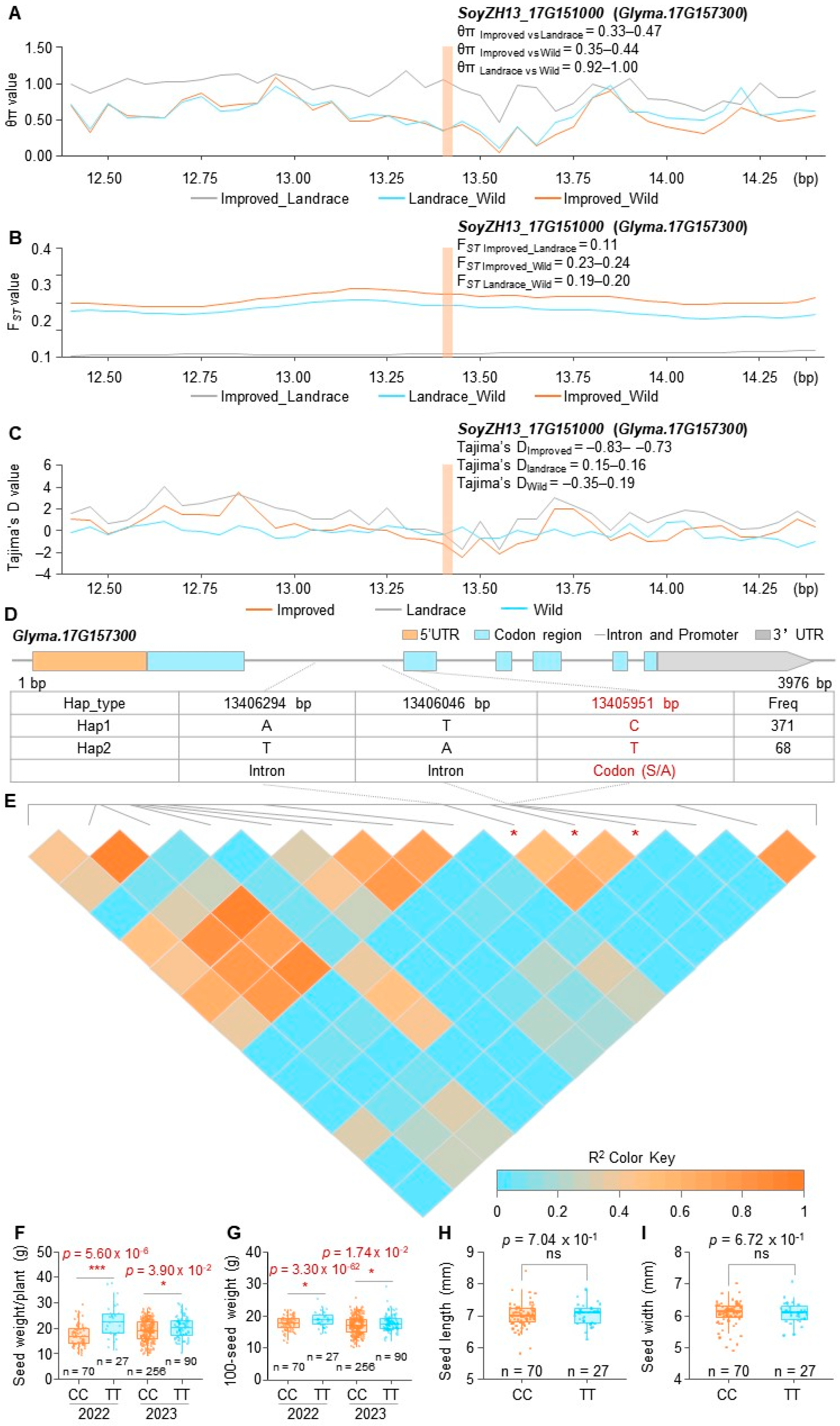

3.6. Population Genetic and Haplotype Analyses of Yield Candidate Gene GmPILS36

4. Discussion

4.1. The PILS Genes Reveal Significant Functional Differentiation Among Multiple Species

4.2. The GmPILS Genes Demonstrate Significant Functional Diversification in Soybean Evolution

4.3. The Natural Variation CC/TT of GmPILS36 May Be Involved in the Domestication of Soybean Single-Plant Yield

4.4. The Functions and Molecular Mechanisms of GmPILS Genes in Soybean Seed Development Warrant Further Investigation

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, R.; Estelle, M. Diversity and specificity: Auxin perception and signaling through the TIR1/AFB pathway. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2014, 21, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strader, L.C.; Zhao, Y. Auxin perception and downstream events. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2016, 33, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Han, N.; Xie, Y.; Fang, K.; Yang, Y.; Zhu, M.; Wang, J.; Bian, H. The miR393a/target module regulates seed germination and seedling establishment under submergence in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Plant Cell Environ. 2016, 39, 2288–2302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, J.; Li, G.; Qu, D.; Li, X.; Wang, Y. Into the seed: Auxin controls seed development and grain yield. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feraru, E.; Vosolsobě, S.; Feraru, M.I.; Petrášek, J.; Kleine-Vehn, J. Evolution and structural diversification of PILS putative auxin carriers in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2012, 3, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogaert, K.A.; Blomme, J.; Beeckman, T.; De Clerck, O. Auxin’s origin: Do PILS hold the key? Trends Plant Sci. 2022, 27, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauer, M.; Kleine-Vehn, J. PIN-FORMED and PIN-LIKES auxin transport facilitators. Development 2019, 146, dev168088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Meng, X.; Fan, X.; Chen, S.; Sang, K.; Yu, J.; Zhou, Y.; Xia, X. Regulation of PILS genes by bZIP transcription factor TGA7 in tomato plant growth. Plant Sci. 2025, 352, 112359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Béziat, C.; Barbez, E.; Feraru, M.I.; Lucyshyn, D.; Kleine-Vehn, J. Light triggers PILS-dependent reduction in nuclear auxin signalling for growth transition. Nat. Plants 2017, 3, 17105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feraru, E.; Feraru, M.I.; Barbez, E.; Waidmann, S.; Sun, L.; Gaidora, A.; Kleine-Vehn, J. PILS6 is a temperature-sensitive regulator of nuclear auxin input and organ growth in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 3893–3898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chai, C.; Valliyodan, B.; Maupin, C.; Annen, B.; Nguyen, H.T. Genome-wide analysis and expression profiling of the PIN auxin transporter gene family in soybean (Glycine max). BMC Genom. 2015, 16, 951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Lu, L.; Tao, J.J.; Cheng, T.; Jin, M.; Wang, Z.Y.; Wei, J.J.; Jiang, Z.H.; Sun, W.C.; et al. Global analysis of seed transcriptomes reveals a novel PLATZ regulator for seed size and weight control in soybean. New Phytol. 2023, 240, 2436–2454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Beecher, B.S.; Morris, C.F. Physical mapping and a new variant of Puroindoline b-2 genes in wheat. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2010, 120, 745–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.; Du, Y.; Li, F.; Sun, H.; Zhang, J.; Li, J.; Peng, T.; Xin, Z.; Zhao, Q. The basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor, OsPIL15, regulates grain size via directly targeting a purine permease gene OsPUP7 in rice. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2019, 17, 1527–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Maokai, Y.; Cheng, H.; Guo, M.; Liu, Y.; Wang, L.; Chao, S.; Zhang, M.; Lai, L.; Qin, Y. Characterization of auxin transporter AUX, PIN and PILS gene families in pineapple and evaluation of expression profiles during reproductive development and under abiotic stresses. PeerJ 2021, 9, e11410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Tao, J.J.; Lu, L.; Jiang, Z.H.; Wei, J.J.; Wu, C.M.; Yin, C.C.; Li, W.; Bi, Y.D.; et al. GmJAZ3 interacts with GmRR18a and GmMYC2a to regulate seed traits in soybean. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2023, 65, 1983–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Gao, L.; Ke, M.; Gao, Z.; Tu, T.; Huang, L.; Chen, J.; Guan, Y.; Huang, X.; Chen, X. GmPIN1-mediated auxin asymmetry regulates leaf petiole angle and plant architecture in soybean. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2022, 64, 1325–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Liu, Z.B.; Sanyour-Doyel, N.; Lenderts, B.; Worden, A.; Anand, A.; Cho, H.J.; Bolar, J.; Harris, C.; Huang, L.; et al. Efficient gene targeting in soybean using Ochrobactrum haywardense-mediated delivery of a marker-free donor template. Plant Physiol. 2022, 189, 585–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majidian, P.; Ghorbani, H.R.; Farajpour, M. Achieving agricultural sustainability through soybean production in Iran: Potential and challenges. Heliyon 2024, 10, e26389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.; Yu, Z.; Du, F.; Cao, F.; Yang, M.; Liu, C.; Qi, Z.; Chen, Q.; Zou, J.; Wang, J. Integrated transcriptomic and proteomic characterization of a chromosome segment substitution line reveals the regulatory mechanism controlling the seed weight in soybean. Plants 2024, 13, 908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Wang, Z.; Ren, Y.; Sun, H. Full-length transcriptome analysis of the ABCB, PIN/PIN-LIKES, and AUX/LAX families involved in somatic embryogenesis of Lilium pumilum DC. Fisch. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Thomas, H.R.; Frank, M.H.; He, Y.; Xia, R. TBtools: An integrative toolkit developed for interactive analyses of big biological data. Mol. Plant 2020, 13, 1194–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.; Yong, B.; Jiang, H.; An, Z.; Wang, Y.; Li, B.; Yang, C.; Zhu, W.; Chen, Q.; He, C. A loss-of-function mutant allele of a glycosyl hydrolase gene has been co-opted for seed weight control during soybean domestication. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2023, 65, 2469–2489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, R.; Fan, C.; Li, H.; Zhang, Q.; Fu, Y.F. Evaluation of putative reference genes for gene expression normalization in soybean by quantitative real-time RT-PCR. BMC Mol. Biol. 2009, 10, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Z.; Guo, C.; Li, H.; Qiu, H.; Li, H.; Jong, C.; Yu, G.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, L.; Wu, X.; et al. Natural variation in Fatty Acid 9 is a determinant of fatty acid and protein content. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2024, 22, 759–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Librado, P.; Rozas, J. DnaSP v5: A software for comprehensive analysis of DNA polymorphism data. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1451–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danecek, P.; Auton, A.; Abecasis, G.; Albers, C.A.; Banks, E.; DePristo, M.A.; Handsaker, R.E.; Lunter, G.; Marth, G.T.; Sherry, S.T.; et al. The variant call format and VCFtools. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 2156–2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purcell, S.; Neale, B.; Todd-Brown, K.; Thomas, L.; Ferreira, M.A.; Bender, D.; Maller, J.; Sklar, P.; de Bakker, P.I.; Daly, M.J.; et al. PLINK: A tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007, 81, 559–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clement, M.; Posada, D.; Crandall, K.A. TCS: A computer program to estimate gene genealogies. Mol. Ecol. 2000, 9, 1657–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbez, E.; Kubeš, M.; Rolčík, J.; Béziat, C.; Pěnčík, A.; Wang, B.; Rosquete, M.R.; Zhu, J.; Dobrev, P.I.; Lee, Y.; et al. A novel putative auxin carrier family regulates intracellular auxin homeostasis in plants. Nature 2012, 485, 119–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zheng, Y.; Zhao, L.; Gulam, M.; Ullah, A.; Xie, G. CALMODULIN-LIKE16 and PIN-LIKES7a cooperatively regulate rice seedling primary root elongation under chilling. Plant Physiol. 2024, 195, 1660–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; He, Y.; Liu, Z.; Qin, T.; Wang, L.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, H.; Li, H.; Liu, L.; et al. OsSPL14 acts upstream of OsPIN1b and PILS6b to modulate axillary bud outgrowth by fine-tuning auxin transport in rice. Plant J. 2022, 111, 1167–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhai, L.; Yang, L.; Xiao, X.; Jiang, J.; Guan, Z.; Fang, W.; Chen, F.; Chen, S. PIN and PILS family genes analyses in Chrysanthemum seticuspe reveal their potential functions in flower bud development and drought stress. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 220, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, J.M.; Tian, S.R.; Liang, Y.L.; Zhu, Y.L.; Zhou, D.G.; Que, Y.X.; Ling, H.; Huang, N. Identification and expression analysis of PIN-LIKES gene family in sugarcane. Acta Agron. Sin. 2023, 49, 414–425. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Y.K.; Huang, D.Q.; Gao, Z.; Chen, X. Identification, expression profile of soybean PIN-Like (PILS) gene family and its function in symbiotic nitrogen fixation in root nodules. Acta Agron. Sin. 2022, 48, 353–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmutz, J.; Cannon, S.B.; Schlueter, J.; Ma, J.; Mitros, T.; Nelson, W.; Hyten, D.L.; Song, Q.; Thelen, J.J.; Cheng, J.; et al. Genome sequence of the palaeopolyploid soybean. Nature 2010, 463, 178–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Force, A.; Lynch, M.; Pickett, F.B.; Amores, A.; Yan, Y.L.; Postlethwait, J. Preservation of duplicate genes by complementary, degenerative mutations. Genetics 1999, 151, 1531–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panchy, N.; Lehti-Shiu, M.; Shiu, S.H. Evolution of gene duplication in plants. Plant Physiol. 2016, 171, 2294–2316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.; Yang, M.; Tang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, H.; Ni, H.; Chen, Q.; Meng, F.; Jiang, J. Dynamics of cis-regulatory sequences and transcriptional divergence of duplicated genes in soybean. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2303836120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, A.E.; Liberles, D.A. Dosage balance acts as a time-dependent selective barrier to subfunctionalization. BMC Ecol. Evol. 2023, 23, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goettel, W.; Zhang, H.; Li, Y.; Qiao, Z.; Jiang, H.; Hou, D.; Song, Q.; Pantalone, V.R.; Song, B.H.; Yu, D.; et al. POWR1 is a domestication gene pleiotropically regulating seed quality and yield in soybean. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 3051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, H.; Hou, L.; Xie, J.; Cao, F.; Wei, R.; Yang, M.; Qi, Z.; Zhu, R.; Zhang, Z.; Xin, D.; et al. Construction of chromosome segment substitution lines and inheritance of seed-pod characteristics in wild soybean. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 869455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Gene_ Name | Gene_ ID | No. Amino Acids | Theoretical_ pI | Instability_ Index | Grand Average of Hydropathicity | Subcellular Localization |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GmPILS1 | Glyma.01G156200 | 415 | 5.59 | 32.13 | 0.707 | Cell membrane |

| GmPILS2 | Glyma.01G157700 | 419 | 5.1 | 37.96 | 0.593 | Cell membrane |

| GmPILS3 | Glyma.03G113600 | 424 | 7.54 | 40.39 | 0.725 | Cell membrane |

| GmPILS4 | Glyma.03G126000 | 597 | 9.08 | 34.77 | 0.243 | Cell membrane |

| GmPILS5 | Glyma.05G109800 | 362 | 8.92 | 39.9 | 0.642 | Cell membrane |

| GmPILS6 | Glyma.06G297700 | 122 | 4.68 | 40.87 | 0.698 | Cell membrane |

| GmPILS7 | Glyma.07G102500 | 605 | 8.64 | 33.98 | 0.097 | Cell membrane |

| GmPILS8 | Glyma.07G113100 | 418 | 8.71 | 33.92 | 0.61 | Cell membrane |

| GmPILS9 | Glyma.07G164600 | 556 | 6.57 | 38.09 | 0.185 | Cell membrane |

| GmPILS10 | Glyma.07G217900 | 665 | 7.72 | 37.66 | 0.159 | Cell membrane and nucleus |

| GmPILS11 | Glyma.08G054700 | 603 | 8.64 | 33.15 | 0.054 | Cytoplasm |

| GmPILS12 | Glyma.09G061800 | 443 | 9.12 | 42.48 | 0.53 | Cytoplasm |

| GmPILS13 | Glyma.09G097300 | 487 | 9.03 | 46.98 | 0.431 | Cytoplasm |

| GmPILS14 | Glyma.09G116100 | 440 | 5.3 | 36.6 | 0.644 | Cell membrane |

| GmPILS15 | Glyma.09G117900 | 634 | 7.27 | 37.09 | 0.179 | Cell membrane |

| GmPILS16 | Glyma.09G176300 | 420 | 9.19 | 38.28 | −0.057 | Cell membrane |

| GmPILS17 | Glyma.09G195600 | 414 | 8.97 | 36.89 | 0.594 | Cell membrane |

| GmPILS18 | Glyma.09G196900 | 409 | 5.5 | 36.65 | 0.631 | Cell membrane |

| GmPILS19 | Glyma.09G240500 | 358 | 9.7 | 37.82 | 0.726 | Cell membrane |

| GmPILS20 | Glyma.09G251600 | 377 | 7.53 | 30.08 | 0.683 | Cell membrane |

| GmPILS21 | Glyma.09G271100 | 414 | 8.09 | 36.57 | 0.732 | Cell membrane |

| GmPILS22 | Glyma.10G189000 | 400 | 8.82 | 40.82 | 0.716 | Cell membrane |

| GmPILS23 | Glyma.10G189100 | 313 | 8.46 | 37.58 | 0.527 | Cell membrane |

| GmPILS24 | Glyma.11G087300 | 419 | 5.1 | 41.4 | 0.594 | Cell membrane |

| GmPILS25 | Glyma.11G088600 | 415 | 5.18 | 31.16 | 0.709 | Cell membrane |

| GmPILS26 | Glyma.13G038300 | 350 | 5.96 | 41.1 | 0.247 | Chloroplast |

| GmPILS27 | Glyma.13G038400 | 126 | 9.51 | 37.92 | 1.009 | Chloroplast |

| GmPILS28 | Glyma.13G101900 | 642 | 9.1 | 42.09 | 0.12 | Cell membrane |

| GmPILS29 | Glyma.14G120900 | 531 | 8.88 | 37.09 | 0.366 | Cell membrane |

| GmPILS30 | Glyma.15G168100 | 469 | 9.21 | 36.98 | 0.186 | Cell membrane |

| GmPILS31 | Glyma.15G208600 | 492 | 8.27 | 37.63 | 0.344 | Cytoplasm |

| GmPILS32 | Glyma.16G114900 | 594 | 5.43 | 37.59 | 0.553 | Cell membrane |

| GmPILS33 | Glyma.16G115000 | 115 | 7.74 | 28.03 | 1.219 | Cell membrane |

| GmPILS34 | Glyma.16G115500 | 414 | 7.03 | 35.78 | 0.674 | Cell membrane |

| GmPILS35 | Glyma.17G057300 | 637 | 9.05 | 43.64 | 0.141 | Cell membrane |

| GmPILS36 | Glyma.17G157300 | 363 | 8.92 | 39.64 | 0.63 | Cell membrane |

| GmPILS37 | Glyma.18G218300 | 414 | 7.51 | 36.92 | 0.727 | Cell membrane |

| GmPILS38 | Glyma.18G241000 | 369 | 8.3 | 35.2 | 0.707 | Cell membrane |

| GmPILS39 | Glyma.18G255800 | 359 | 9.72 | 40.29 | 0.699 | Cell membrane |

| GmPILS40 | Glyma.19G072900 | 445 | 5.38 | 34.63 | 0.636 | Cell membrane |

| GmPILS41 | Glyma.19G128800 | 481 | 7.69 | 39.96 | 0.14 | Cytoplasm |

| GmPILS42 | Glyma.20G014300 | 666 | 7.21 | 38.62 | 0.147 | Nucleus |

| GmPILS43 | Glyma.20G201600 | 409 | 9.14 | 37.18 | 0.746 | Cell membrane |

| GmPILS44 | Glyma.20G201700 | 259 | 7.71 | 31.93 | 0.634 | Cell membrane |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wei, S.; Han, J.; Tang, C.; Zhang, L.; Yang, M.; Cao, F.; Zhao, Y.; Li, X.; Xu, H.; Qi, Z.; et al. The PIN-LIKES Auxin Transport Genes Involved in Regulating Yield in Soybean. Agronomy 2026, 16, 226. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16020226

Wei S, Han J, Tang C, Zhang L, Yang M, Cao F, Zhao Y, Li X, Xu H, Qi Z, et al. The PIN-LIKES Auxin Transport Genes Involved in Regulating Yield in Soybean. Agronomy. 2026; 16(2):226. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16020226

Chicago/Turabian StyleWei, Siming, Jiayin Han, Chun Tang, Lei Zhang, Mingliang Yang, Fubin Cao, Yuyao Zhao, Xinghua Li, Hao Xu, Zhaoming Qi, and et al. 2026. "The PIN-LIKES Auxin Transport Genes Involved in Regulating Yield in Soybean" Agronomy 16, no. 2: 226. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16020226

APA StyleWei, S., Han, J., Tang, C., Zhang, L., Yang, M., Cao, F., Zhao, Y., Li, X., Xu, H., Qi, Z., & Chen, Q. (2026). The PIN-LIKES Auxin Transport Genes Involved in Regulating Yield in Soybean. Agronomy, 16(2), 226. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16020226