Identification of Wild Segments Related to High Seed Protein Content Under Multiple Environments and Analysis of Its Candidate Genes in Soybean

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials

2.2. Field Experiment Design

2.3. Measurement and Phenotypic Analysis of Protein Content

2.4. Identification of Wild Segments Associated with Protein Content

2.5. Prediction of Candidate Genes for Seed Protein Content

3. Results

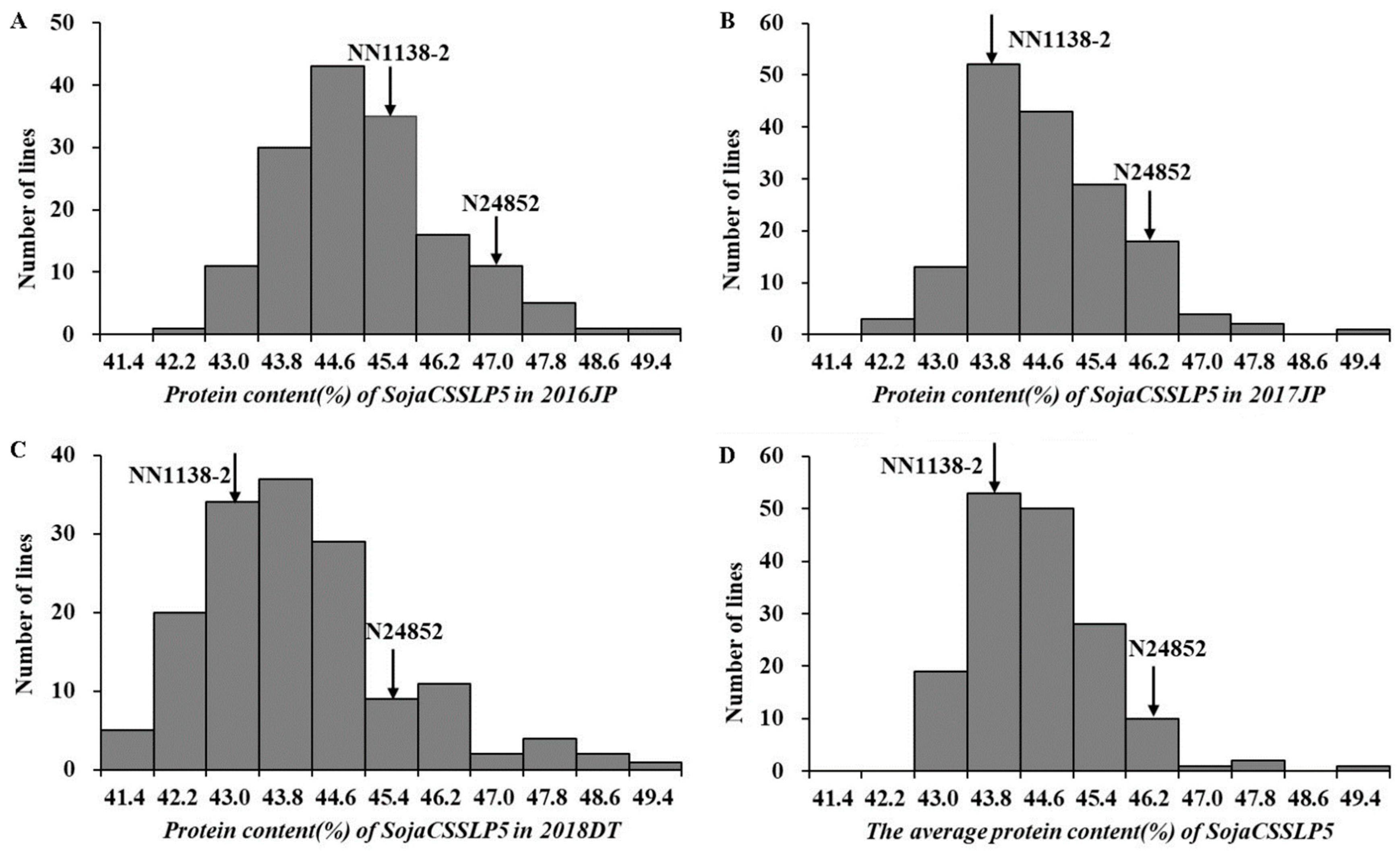

3.1. Performance of Protein Content Among the CSSL Population and Its Parents

3.2. Identification of Wild Segments Associated with Protein Content

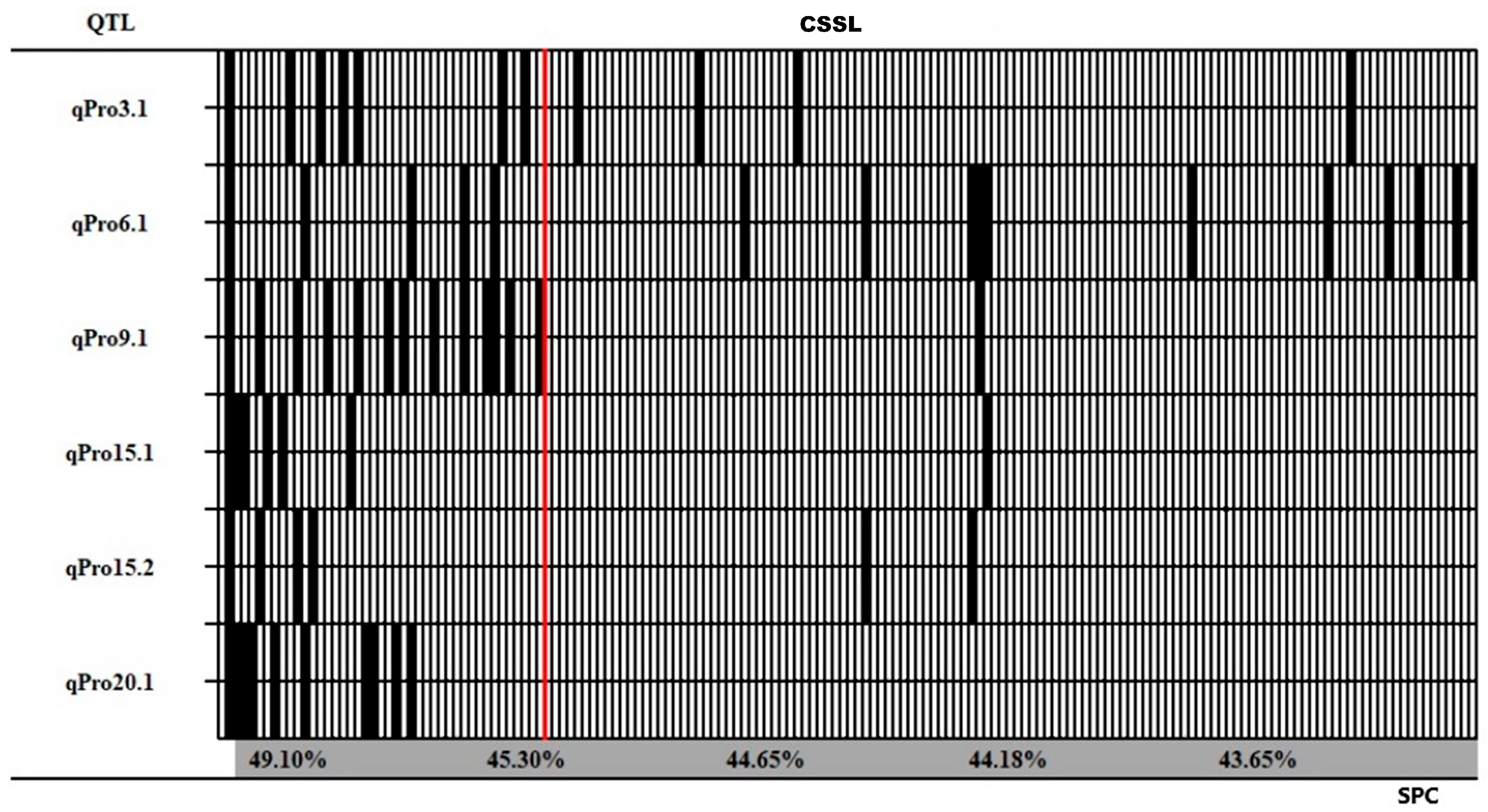

3.3. QTL–Allele Matrix for Protein Content in the SojaCSSLP5

3.4. Prediction of Candidate Genes for Soybean Protein Content

4. Discussion

4.1. Genetic Basis of Protein Content in Wild Soybean and Comparison with Previous Studies

4.2. Candidate Gene of Protein Content in Soybean

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Foyer, C.H.; Lam, H.M.; Nguyen, H.T.; Siddique, K.H.M.; Varshney, R.K.; Colmer, T.D.; Cowling, W.; Bramley, H.; Mori, T.A.; Hodgson, J.M.; et al. Neglecting legumes has compromised human health and sustainable food production. Nat. Plants 2016, 2, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.H.; Zhou, R.B.; Gai, J.Y. A comparative analysis of protein and fat content between wild and cultivaed soybeans in China. Soyb. Sci. 2009, 28, 566–573. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.L.; Meng, Q.X.; Yang, Q.K.; Zhao, S.W.; Wu, T.L. Effect of backcrossing on overcoming viny and lodging hablt of cultivated × wild and cultivated × semi-wild crosses. Soyb. Sci. 1986, 5, 181–187. [Google Scholar]

- Hyten, D.L.; Pantalone, V.R.; Sams, C.E.; Saxton, A.M.; Landau-Ellis, D.; Stefaniak, T.R.; Schmidt, M.E. Seed quality QTL in a prominent soybean population. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2004, 109, 552–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liao, H.; Yan, X. Study on analying soybean protein and oil content by neat-infrared spectroscopy. Soyb. Sci. 2005, 24, 199–201. [Google Scholar]

- Bolon, Y.; Joseph, B.; Cannon, S.; Graham, M.; Diers, B.; Farmer, A.; May, G.; Muehlbauer, G.; Specht, J.; Tu, Z. Complementary genetic and genomic approaches help characterize the linkage group I seed protein QTL in soybean. BMC Plant Biol. 2010, 10, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fliege, C.; Ward, R.A.; Vogel, P.; Nguyen, H.; Quach, T.; Guo, M.; Viana, J.P.G.; Dos Santos, L.B.; Specht, J.E.; Clemente, T.E. Fine mapping and cloning of the major seed protein qtl on soybean chromosome 20. Plant J. 2022, 10, 1011–1025. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh, J.I.; Hu, H.; Petereit, J.; Bayer, P.E.; Valliyodan, B.; Batley, J.; Nguyen, H.T.; Edwards, D. Haplotype mapping uncovers unexplored variation in wild and domesticated soybean at the major protein locus cqProt-003. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2022, 153, 1443–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diers, B.W.; Keim, P.; Fehr, W.R.; Shoemaker, R.C. RFLP analysis of soybean seed protein and oil content. Theor. Appl. Genet. 1992, 83, 608–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebolt, A.M.; Shoemaker, R.C.; Diers, B.W. Analysis of a quantitative trait locus allele from wild soybean that increases seed protein concentration in soybean. Crop Sci. 2000, 40, 1438–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshed, Y.; Zamir, D. A genomic library of Lycopersicon pennellii in L. esculentum: A tool for fine mapping of genes. Euphytica 1994, 79, 175–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, X.Y.; Weng, J.F.; Zhai, H.Q.; Wang, J.K.; Lei, C.L.; Liu, X.L.; Guo, T.; Jiang, L.; Su, N.; Wan, J.M. Quantitative trait loci (QTL) analysis for rice grain width and fine mapping of an identified QTL allele gw-5 in a recombination hotspot region on chromosome 5. Genetics 2008, 179, 2239–2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alpert, K.B.; Tanksley, S.D. High-resolution mapping and isolation of a yeast artificial chromosome contig containing fw2.2: A major fruit weight quantitative trait locus in tomato. Plant Biol. 1996, 93, 15503–15507. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.B.; He, Q.Y.; Yang, H.Y.; Xiang, S.H.; Zhao, T.J.; Gai, J.Y. Development of a chromosome segment substitution line population with wild soybean (Glycine soja Sieb. et Zucc.) as donor parent. Euphytica 2013, 189, 293–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.W.; Li, C.D.; Li, R.C.; Li, Y.Y.; Yin, Y.B.; Ma, Z.Z.; Zeng, Q.L.; Zhang, W.B.; Liu, C.Y.; Chen, Q.S. Construction of wild soybean backcross introgression lines. Chin. J. Oil Crop. Sci. 2020, 42, 8–16. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, S.H.; Wang, W.B.; He, Q.Y.; Yang, H.Y.; Liu, C.; Xing, G.N.; Zhao, T.J.; Gai, J.Y. Identification of QTL/segments related to agronomic traits using CSSL population under multiple environments. Sci. Agric. Sin. 2015, 48, 10–22. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.Y.; Wang, W.B.; He, Q.Y.; Xiang, S.H.; Tian, D.; Zhao, T.J.; Gai, J.Y. Identifying a wild allele conferring small seed size, high protein content and low oil content using chromosome segment substitution lines in soybean. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2019, 132, 2793–2807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.Y.; Wang, W.B.; He, Q.Y.; Xiang, S.H.; Tian, D.; Zhao, T.J.; Gai, J.Y. Chromosome segment detection for seed size and shape traits using an improved population of wild soybean chromosome segment substitution lines. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2017, 23, 877–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.L.; Wang, W.B.; Guo, N.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Bu, Y.P.; Zhao, J.M.; Xing, H. Combining QTL-seq and linkage mapping to fine map a wild soybean allele characteristic of greater plant height. BMC Genom. 2018, 19, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miao, L.; Yang, S.; Zhang, K.; He, J.; Wu, C.; Ren, Y.; Gai, J.; Li, Y. Natural variation and selection in Gmsweet39 affect soybean seed oil content. New Phytol. 2020, 225, 1651–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Chen, X.N.; Wang, W.B.; Hu, X.Y.; Han, W.; He, Q.Y.; Yang, H.Y.; Xiang, S.H.; Gai, J.Y. Identifying wild versus cultivated gene-alleles conferring seed coat color and days to flowering in soybean. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byfield, G.E.; Xue, H.; Upchurch, R.G. Two genes from soybean encoding soluble Δ9 stearoyl-ACP desaturases. Crop Sci. 2006, 46, 840–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goettel, W.; Zhang, H.; Li, Y.; Qiao, Z.; Jiang, H.; Hou, D.; An, Y.Q.C. POWR1 is a domestication gene pleiotropically regulating seed quality and yield in soybean. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 3051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Xue, J.; Lin, L.; Liu, D.; Wu, J.; Jiang, J.; Wang, Y. Overexpression of soybean transcription factors GmDof4 and GmDof11 significantly increase the oleic acid content in seed of Brassica napus L. Agronomy 2018, 8, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wei, J.-J.; Zhang, W.K.; Chen, S.Y.; Zhang, J.S. Regulation of seed traits in soybean. Abiotech 2023, 4, 372–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, T.T.; Jiang, Z.F.; Han, Y.P.; Teng, W.L.; Zhao, X.; Li, W.B. Identification of quantitative trait loci underlying seed protein and oil contents of soybean across multi-genetic backgrounds and environments. Plant Breed. 2013, 132, 630–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajuddin, T.; Watanabe, S.; Yamanaka, N.; Harada, K. Analysis of quantitative trait loci for protein and lipid contents in soybean seeds using recombinant inbred lines. Breed Sci. 2003, 53, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asekova, S.; Kulkarni, K.P.; Kim, M.; Kim, J.H.; Song, J.T.; Shannon, J.G.; Lee, J.D. Novel quantitative trait loci for forage quality traits in a cross between pi 483463 and ‘hutcheson’ in soybean. Crop Sci. 2016, 56, 2600–2611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, D.M.; Glover, K.D.; Carlson, S.R.; Specht, J.E.; Diers, B.W. Fine mapping of a seed protein QTL on soybean linkage group I and its correlated effects on agronomic traits. Crop Sci. 2006, 46, 834–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brummer, E.C.; Graef, G.L.; Orf, J.; Wilcox, J.R.; Shoemaker, R.C. Mapping QTL for seed protein and oil content in eight soybean populations. Crop Sci. 1997, 37, 370–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandurangan, S.; Pajak, A.; Molnar, S.J.; Cober, E.R.; Dhaubhadel, S.; Hernandez-Sebastia, C.; Kaiser, W.M.; Nelson, R.L.; Huber, S.C.; Marsolais, F. Relationship between asparagine metabolism and protein concentration in soybean seed. J. Exp. Bot. 2012, 63, 3173–3184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.G.; Wen, Z.X.; Li, H.C.; Yuan, D.H.; Li, J.Y.; Zhang, H.; Huang, Z.W.; Cui, S.Y.; Du, W.J. Identification of the quantitative trait loci (QTL) underlying water soluble protein content in soybean. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2013, 126, 425–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.Z.; Jiang, G.L.; Green, M.; Scott, R.A.; Song, Q.J.; Hyten, D.L.; Cregan, P.B. Identification and validation of quantitative trait loci for seed yield, oil and protein contents in two recombinant inbred line populations of soybean. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2014, 289, 935–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Q.Y.; Yang, H.Y.; Xiang, S.H.; Wang, W.B.; Xing, G.N.; Zhao, T.J.; Gai, J.Y. QTL mapping for the number of branches and pods using wild chromosome segment substitution lines in soybean [Glycine max (L.) Merr.]. Plant Genet. Resour. 2014, 12, S172–S177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.B.; He, Q.Y.; Yang, H.Y.; Xiang, S.H.; Xing, G.N.; Zhao, T.J.; Gai, J.Y. Identification of QTL/segments related to seed-quality traits in G. soja using chromosome segment substitution lines. Plant Genet. Resour. 2014, 12, S65–S69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derbyshire, E.; Wright, D.; Boulter, D. Legumin and vicilin, storage proteins of legume seeds. Phytochemistry 1976, 15, 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, S.; Wakasa, Y.; Ozawa, K.; Takaiwa, F. Characterization of IRE1 ribonuclease-mediated mRNA decay in plants using transient expression analyses in rice protoplasts. New Phytol. 2016, 210, 1259–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hegedus, D.; Yu, M.; Baldwin, D.; Gruber, M.; Sharpe, A.; Parkin, I.; Whitwill, S.; Lydiate, D. Molecular characterization of brassica napus NAC domain transcriptional activators induced in response to biotic and abiotic stress. Plant Mol. Biol. 2003, 53, 383–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chen, Z.C.; Zhang, Q.; Meng, S.S.; Wei, C.X. The NAC transcription factors OsNAC20 and OsNAC26 regulate starch and storage protein synthesis. Plant Physiol. 2020, 184, 1775–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Env. | Parents | SojaCSSLP5 | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NN1138-2 | N24852 | Class Mid-Value (%) | Range (%) | Mean (%) | CV | h2 | |||||||||||

| 41.4 | 42.2 | 43.0 | 43.8 | 44.6 | 45.4 | 46.2 | 47.0 | 47.8 | 48.6 | 49.4 | |||||||

| 2016JP | 45.48 | 46.97 | 0 | 1 | 11 | 30 | 43 | 35 | 16 | 11 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 42.22–49.27 | 45.08 | 0.03 | 0.75 |

| 2017JP | 43.98 | 45.88 | 0 | 3 | 13 | 52 | 43 | 29 | 18 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 42.13–49.15 | 44.60 | 0.03 | 0.80 |

| 2018DT | 43.00 | 45.75 | 5 | 20 | 34 | 37 | 29 | 9 | 11 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 41.40–49.15 | 44.00 | 0.04 | 0.78 |

| Mean | 44.15 | 46.20 | 0 | 0 | 19 | 53 | 50 | 28 | 10 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 42.86–49.08 | 45.00 | 0.03 | 0.70 |

| Source of Variation | DF | MS | F Value | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environment (Env) | 2 | 107.73 | 100.82 | <0.0001 |

| Repeat (Env) | 6 | 17.01 | 15.92 | <0.0001 |

| Line | 163 | 7.91 | 7.40 | <0.0001 |

| Line × Env | 306 | 2.59 | 2.42 | <0.0001 |

| Error | 837 | 1.07 | ||

| Total | 1314 |

| QTL | Marker | Genome Region | Size of Region (KB) | LOD | PVE (%) | Add (%) | Reported QTL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| qPro3.1 | Gm03_LDB_36 | 40,609,452–41,028,039 | 418.59 | 3.06 | 3.58 | 0.42 | Seed protein36-34 [26] |

| Seed protein36-35 [26] | |||||||

| qPro6.1 | Gm06_LDB_14 | 4,859,600–5,358,717 | 499.12 | 4.75 | 5.74 | 0.44 | New |

| qPro9.1 | Gm09_LDB_74 | 44,878,012–44,951,892 | 73.88 | 8.02 | 10.13 | 0.62 | Seed protein36-28 [26] |

| Seed protein36-29 [26] | |||||||

| qPro15.1 | Gm15_LDB_12 | 5,335,613–6,085,762 | 750.15 | 8.49 | 10.84 | 0.92 | Seed protein 30-3 [27] |

| qPro15.2 | Gm15_LDB_31 | 11,936,865–12,087,185 | 150.32 | 3.93 | 4.67 | 0.66 | Crude protein, R6 1-5 [28] |

| qPro20.1 | Gm20_LDB_28 | 13,996,858–24,336,032 | 10,339.17 | 15.82 | 22.46 | 1.09 | cqSeed protein-003 [29] |

| Seed protein 1-3 [9] | |||||||

| Seed protein 1-4 [9] | |||||||

| Seed protein 3-12 [30] | |||||||

| Seed protein 10-1 [10] | |||||||

| Seed protein 11-1 [10] | |||||||

| Seed protein 30-1 [27] | |||||||

| Seed protein 31-1 [31] | |||||||

| Seed protein 34-11 [32] | |||||||

| Seed protein36-26 [26] | |||||||

| Seed protein 37-8 [33] |

| Gene | Gene Position | QTL | Annotation | Parents | SNP Haplotype | Expression Difference (FPKM) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wm82.a2.v1 | 14 Seed | 21 Seed | 28 Seed | 35 Seed | Leaf | Flower | |||||

| Glyma.03G198500 | Gm03:40774384–40776151 | qPro3.1 | Nucleic acid binding | NN1138-2 | GCAC | 13.34 | 12.94 | 4.50 | 8.91 | 15.30 | 9.52 |

| N24852 | ATTG | 13.89 | 7.04 | 14.87 | 58.44 | 20.17 | 8.33 | ||||

| Glyma.03G200000 | Gm03:40887582–40889109 | qPro3.1 | Polynucleotidyl transferase/ribonuclease | NN1138-2 | T | 6.93 | 4.16 | 1.31 | 1.68 | 4.91 | 9.05 |

| N24852 | C | 5.11 | 1.31 | 3.04 | 10.76 | 5.11 | 14.85 | ||||

| Glyma.06G065900 | Gm06:5028393–5034377 | qPro6.1 | Serine-rich protein-related | NN1138-2 | CT | 13.44 | 2.41 | 2.33 | 3.80 | 13.93 | 12.26 |

| N24852 | AA | 5.88 | 3.10 | 21.90 | 59.96 | 27.17 | 18.54 | ||||

| Glyma.06G066900 | Gm06:5093927–5103072 | qPro6.1 | Protein binding | NN1138-2 | CGAGTTCG | 7.70 | 6.37 | 3.90 | 4.01 | 9.38 | 6.14 |

| N24852 | AATTGATC | 7.33 | 3.32 | 7.84 | 19.26 | 10.44 | 5.57 | ||||

| Glyma.09G223900 | Gm09:44887793–44891771 | qPro9.1 | Protein transmembrane transport | NN1138-2 | AAGT | 6.42 | 6.33 | 3.75 | 3.49 | 3.32 | 2.82 |

| N24852 | TGTA | 4.37 | 2.18 | 6.65 | 26.63 | 3.52 | 2.61 | ||||

| Glyma.09G224300 | Gm09:44916070–44919953 | qPro9.1 | Cysteine-rich protein-related | NN1138-2 | CGAGCATT | 22.41 | 17.47 | 9.19 | 8.49 | 20.72 | 15.41 |

| N24852 | TACCGGAC | 18.07 | 9.79 | 19.51 | 89.40 | 20.04 | 10.92 | ||||

| Glyma.15G005900 | Gm15:503903–506167 | qPC15-1 | hydroxyproline-rich glycoprotein family protein | NN1138-2 | GAACTTCACG | 40.93 | 37.03 | 8.05 | 16.54 | 32.60 | 20.16 |

| N24852 | AGTTGATCGA | 32.38 | 12.01 | 22.39 | 25.56 | 38.00 | 22.72 | ||||

| Glyma.15G008800 | Gm15:700088–701291 | qPC15-1 | Embryo-specific protein 3 | NN1138-2 | CCAACTAC | 99.22 | 88.49 | 19.82 | 22.64 | 67.61 | 97.39 |

| N24852 | ATTTAGGT | 89.02 | 55.65 | 30.93 | 1.15 | 45.05 | 163.15 | ||||

| Glyma.15G145000 | Gm15:11930954–11932523 | qPro15.2 | - | NN1138-2 | GA | 15.08 | 21.69 | 10.93 | 17.49 | 41.46 | 12.79 |

| N24852 | AG | 31.51 | 19.94 | 9.96 | 0.25 | 25.42 | 15.84 | ||||

| Glyma.20G085100 | Gm20:31774770–31779804 | qPro20.1 | Nucleoprotein containing a CCT domain | NN1138-2 | - | 0.59 | 1.13 | 0.57 | 1.31 | 0.27 | 2.75 |

| N24852 | 321bp-InDel | 2.23 | 2.26 | 1.45 | 0.19 | 1.96 | 0.64 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, N.; Cai, M.; Luo, W.; Han, W.; Liu, C.; He, J.; Liu, F.; Sun, L.; Xing, G.; Gai, J.; et al. Identification of Wild Segments Related to High Seed Protein Content Under Multiple Environments and Analysis of Its Candidate Genes in Soybean. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2902. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122902

Li N, Cai M, Luo W, Han W, Liu C, He J, Liu F, Sun L, Xing G, Gai J, et al. Identification of Wild Segments Related to High Seed Protein Content Under Multiple Environments and Analysis of Its Candidate Genes in Soybean. Agronomy. 2025; 15(12):2902. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122902

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Ning, Mengdan Cai, Wei Luo, Wei Han, Cheng Liu, Jianbo He, Fangdong Liu, Lei Sun, Guangnan Xing, Junyi Gai, and et al. 2025. "Identification of Wild Segments Related to High Seed Protein Content Under Multiple Environments and Analysis of Its Candidate Genes in Soybean" Agronomy 15, no. 12: 2902. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122902

APA StyleLi, N., Cai, M., Luo, W., Han, W., Liu, C., He, J., Liu, F., Sun, L., Xing, G., Gai, J., & Wang, W. (2025). Identification of Wild Segments Related to High Seed Protein Content Under Multiple Environments and Analysis of Its Candidate Genes in Soybean. Agronomy, 15(12), 2902. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122902