Cellulolytic Microbial Inoculation Enhances Sheep Manure Composting by Improving Nutrient Retention and Reshaping Microbial Community Structure

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Composting Materials

2.2. Composting Experiments

2.3. Physico-Chemical Analysis

2.4. DNA Extraction and High-Throughput Sequencing

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

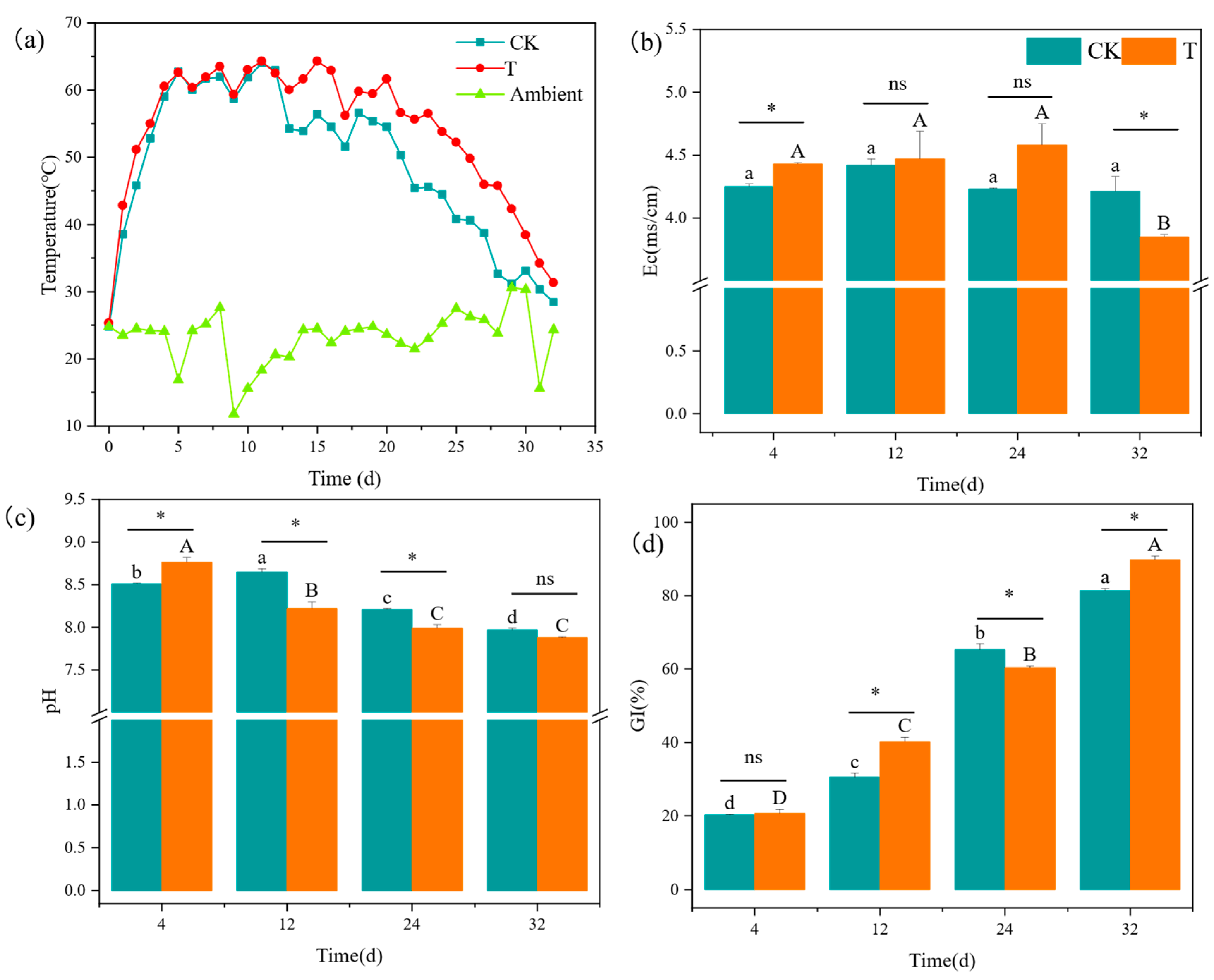

3.1. Evaluation of Temperature

3.2. Changes in Physicochemical Properties

3.2.1. Electrical Conductivity

3.2.2. pH

3.2.3. GI

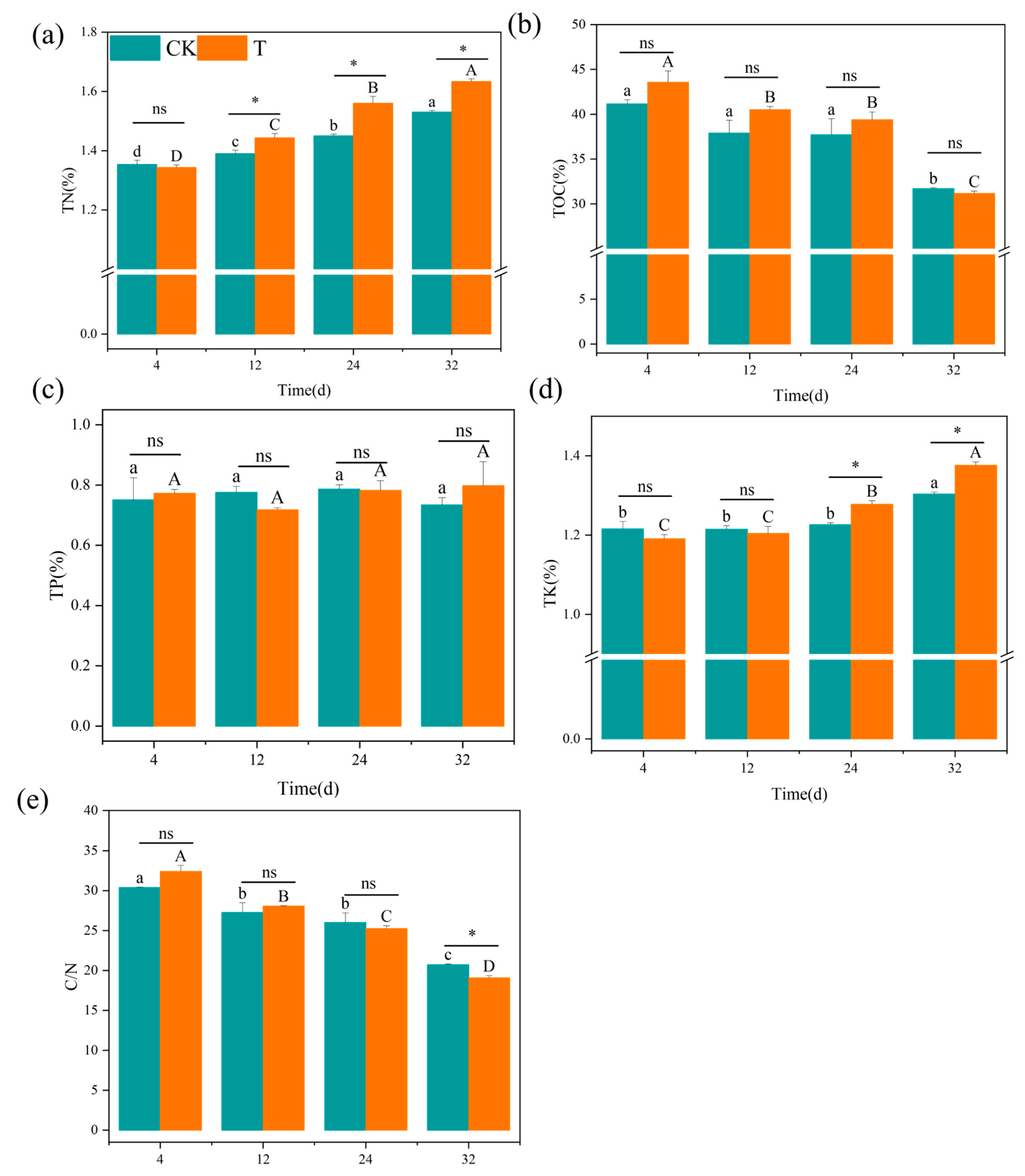

3.2.4. Changes in Major Nutrient Content

3.3. Microbial Community Structure Analysis

3.3.1. Biodiversity of Microbial Communities

3.3.2. Taxonomic Composition of Bacterial and Fungal Communities

3.3.3. Analysis of Microbial Correlation Network

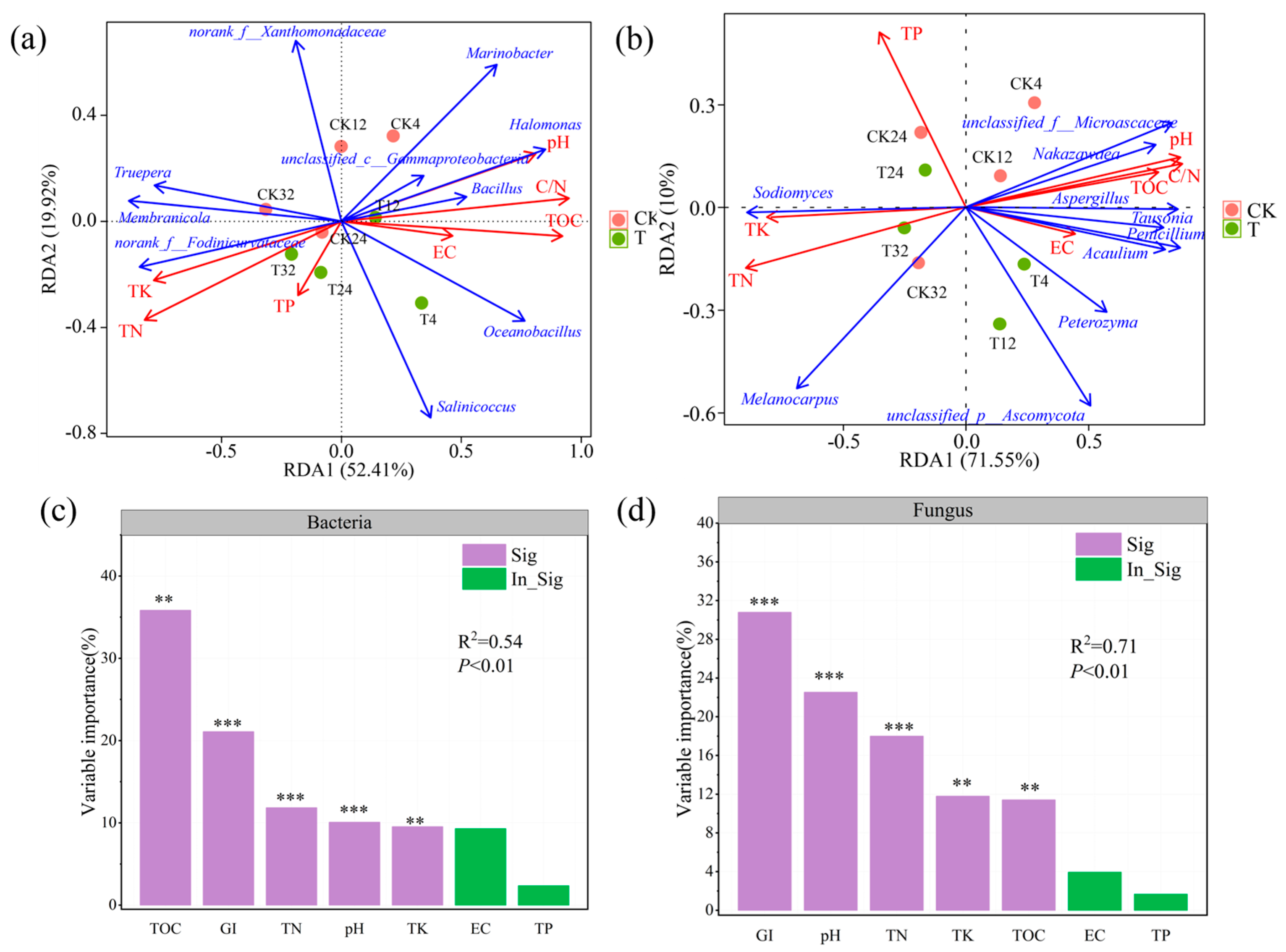

3.4. Correlations Between Environmental Factors and Microbial Community Composition

3.5. The Relationship Between Physicochemical Factors and Microbial Communities

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TOC | Total organic carbon |

| GI | Germination index |

| TN | Total nitrogen |

| TP | Total phosphorus |

| TK | Total potassium |

| EC | Electrical conductivity |

References

- Statista. China: Sheep and Goat Livestock 2013–2023; China Statistical Yearbook: Beijing, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.; Yuan, J.; Ding, J.; Wang, H.; Shen, Y.; Li, G. Effects of carbon/nitrogen ratio and aeration rate on the sheep manure composting process and associated gaseous emissions. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 323, 116093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Zhou, H.; Meng, H.; Ding, J.; Shen, Y.; Cheng, H.; Zhang, X.; Li, R.; Fan, S. Amino acid profile characterization during the co-composting of a livestock manure and maize straw mixture. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 278, 123494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, S.; Douglas, P.; Jarvis, D.; Marczylo, E. Bioaerosol exposure from composting facilities and health outcomes in workers and in the community: A systematic review update. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2019, 222, 364–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Insam, H.; De Bertoldi, M. Microbiology of the composting process. In Waste Management Series; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007; Volume 8, pp. 25–48. [Google Scholar]

- Aguilar-Paredes, A.; Valdés, G.; Araneda, N.; Valdebenito, E.; Hansen, F.; Nuti, M. Microbial Community in the Composting Process and Its Positive Impact on the Soil Biota in Sustainable Agriculture. Agronomy 2023, 13, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, R.; Cai, Y.; Li, J.; Kong, Y.; Jiang, T.; Chang, J.; Yao, S.; Yuan, J.; Li, G.; Wang, G. Biochar reduces gaseous emissions during poultry manure composting: Evidence from the evolution of associated functional genes. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 452, 142060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Awasthi, M.K.; Zhang, Z.; Syed, A.; Bahkali, A.H. Evaluation of gases emission and enzyme dynamics in sheep manure compost occupying with peach shell biochar. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 351, 124065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, C.; Shang, W.; Zhang, T.; Chang, X.; Wu, Z.; He, Y. Effect of microbial inoculum on composting efficiency in the composting process of spent mushroom substrate and chicken manure. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 353, 120145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zainudin, M.H.M.; Zulkarnain, A.; Azmi, A.S.; Muniandy, S.; Sakai, K.; Shirai, Y.; Hassan, M.A. Enhancement of Agro-Industrial Waste Composting Process via the Microbial Inoculation: A Brief Review. Agronomy 2022, 12, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, T.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, D.; Wei, C.; Lin, Y.; Feng, R.; Nan, J.; Feng, Y. Effect of hydrothermal pretreatment and compound microbial agents on compost maturity and gaseous emissions during aerobic composting of kitchen waste. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 854, 158712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Xu, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhang, L.; Li, G.; Nghiem, L.D.; Luo, W. Bacterial dynamics for gaseous emission and humification in bio-augmented composting of kitchen waste. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 801, 149640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Shi, A.; Muhammad, A.; Ye, L.; Muhammad, A. Comprehensive review on agricultural waste utilization and high-temperature fermentation and composting. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2023, 13, 5445–5468. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Long, H.; Hu, X.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; Guo, J.; Zheng, X.; Ye, Y.; Shao, R.; Yang, Q. The co-inoculation of Trichoderma viridis and Bacillus subtilis improved the aerobic composting efficiency and degradation of lignocellulose. Bioresour. Technol. 2024, 394, 130285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Ghanizadeh, H.; Cui, G.; Liu, J.; Miao, S.; Liu, C.; Song, W.; Chen, X.; Cheng, M.; Wang, P.; et al. Microbiome—Based agents can optimize composting of agricultural wastes by modifying microbial communities. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 374, 128765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Qin, X.; Tian, X.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, T.; Huang, J. Inoculating with the microbial agents to start up the aerobic composting of mushroom residue and wood chips at low temperature. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 105294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Li, H.; Yao, T.; Su, M.; Ran, F.; Han, B.; Li, J.; Lan, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, X.; et al. Microbial inoculation influences bacterial community succession and physicochemical characteristics during pig manure composting with corn straw. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 289, 121653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puyuelo, B.; Gea, T.; Sánchez, A. A new control strategy for the composting process based on the oxygen uptake rate. Chem. Eng. J. 2010, 165, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, W.L.P.; Millner, P.; Watson, M.E. (Eds.) Test Methods for the Examination of Composts and Composting (TMECC). In The US Composting Council; US Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, F.; Li, Y.; Han, Y.; Qian, W.; Li, G.; Luo, W. Performance of mature compost to control gaseous emissions in kitchen waste composting. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 657, 262–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wang, G.; Li, G.; Ma, R.; Kong, Y.; Yuan, J. Selection of sensitive seeds for evaluation of compost maturity with the seed germination index. Waste Manag. 2021, 136, 238–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, G.; Yu, Z.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, H.; Yu, M.; Zhao, M. Response of compost maturity and microbial community composition to pentachlorophenol (PCP)-contaminated soil during composting. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 5905–5911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaalid, R.; Kumar, S.; Nilsson, R.H.; Abarenkov, K.; Kirk, P.M.; Kauserud, H. ITS1 versus ITS2 as DNA metabarcodes for fungi. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2013, 13, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, J.; Zou, Y.; Zhang, J.; Peres-Neto, P.R. Generalizing hierarchical and variation partitioning in multiple regression and canonical analyses using the rdacca. hp R package. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2022, 13, 782–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Li, H.; Yao, T.; Su, M.; Li, J.; Liu, Z.; Xin, Y.; Wang, L.; Chen, J.; Gun, S. Effects of microbial inoculation on enzyme activity, available nitrogen content, and bacterial succession during pig manure composting. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 306, 123167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yuan, Z.; Tang, Y. Enhancing food security and environmental sustainability: A critical review of food loss and waste management. Resour. Environ. Sust. 2021, 4, 100023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Fang, C.; Sun, X.; Han, L.; He, X.; Huang, G. Bacterial community succession during pig manure and wheat straw aerobic composting covered with a semi-permeable membrane under slight positive pressure. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 259, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meilander, J.; Caporaso, J.G. Microbiome science of human excrement composting. ISME J. 2024, 18, wrae228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Zhang, L. Addition of mature compost improves the composting of green waste. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 350, 126927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García, C.; Hernández, T.; Costa, F. Study on water extract of sewage sludge composts. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 1991, 37, 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arab, G.; McCartney, D. Benefits to decomposition rates when using digestate as compost co-feedstock: Part I—Focus on physicochemical parameters. Waste Manag. 2017, 68, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Sun, X.; Tian, Y.; Gong, X. Effects of brown sugar and calcium superphosphate on the secondary fermentation of green waste. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 131, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Xu, Y.; Yang, T.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, T.; Zheng, C. Effects of biochar carried microbial agent on compost quality, greenhouse gas emission and bacterial community during sheep manure composting. Biochar 2023, 5, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Kumar Awasthi, M.; Kumar Awasthi, S.; Ren, X.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Z. Influence of fine coal gasification slag on greenhouse gases emission and volatile fatty acids during pig manure composting. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 316, 123915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Xu, K.; Ali, A.; Deng, H.; Cai, H.; Wang, Q.; Pan, J.; Chang, C.-C.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Z. Sulfur-aided composting facilitates ammonia release mitigation, endocrine disrupting chemicals degradation and biosolids stabilization. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 312, 123653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Jia, Y.; Li, J.; Li, P.; Wang, Y.; Yan, F.; Wu, M.; Fang, W.; Xu, F.; Qiu, Z. Influence of microbial augmentation on contaminated manure composting: Metal immobilization, matter transformation, and bacterial response. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 441, 129762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashad, F.M.; Saleh, W.D.; Moselhy, M.A. Bioconversion of rice straw and certain agro-industrial wastes to amendments for organic farming systems: 1. Composting, quality, stability and maturity indices. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, 5952–5960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Luo, W.; Li, Y.; Wang, G.; Li, G. Performance of co-composting sewage sludge and organic fraction of municipal solid waste at different proportions. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 250, 853–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Cai, L.; Li, S.; Chang, S.X.; Sun, X.; An, Z. Bamboo biochar amendment improves the growth and reproduction of Eisenia fetida and the quality of green waste vermicompost. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2018, 156, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammayen, I.; Errami, M.; Ben-Aazza, S.; Iberache, N.; El Housse, M.; Ourouadi, S.; Castanho, R.A.; Loures, L.; Belattar, M.; Hadfi, A. From Marine and Agricultural Waste to Soil Health: Optimized Co-Composting of Sardine By-Products and Tomato Plant Biomass for Sustainable Agriculture and Environmental Protection. Compost Sci. Util. 2025, 32, 120–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Liu, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, K.; Zhang, Y. Development of a compound microbial agent beneficial to the composting of Chinese medicinal herbal residues. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 330, 124948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Wu, Y.; Zhao, J.; Liu, Y.; Gao, L.; Jiang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Tian, W. Comparison of composting factors, heavy metal immobilization, and microbial activity after biochar or lime application in straw-manure composting. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 363, 127872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Li, S.; Meng, Q.; Chen, S.; Wang, J.; Guo, X.; Ding, F.; Shi, L. Feedstock optimization with rice husk chicken manure and mature compost during chicken manure composting: Quality and gaseous emissions. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 387, 129694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdi, R.; Shahgholi, G.; Sharabiani, V.R.; Fanaei, A.R.; Szymanek, M. Prediction compost criteria of organic wastes with Biochar additive in in-vessel composting machine using ANFIS and ANN methods. Energy Rep. 2023, 9, 1684–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, Y.; Ma, X.; Wu, J.; Wang, R.; Zhang, X.; Chu, S.; Zhang, D.; Zhou, P. Plant growth promoting endophyte promotes cadmium accumulation in Solanum nigrum L. by regulating plant homeostasis. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 457, 131866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, D.; Yan, Y.; Wang, R.; Chi, Y.; Zhang, D.; Zhou, P.; Chu, S. Enhancing aerobic composting performance of high-salt oily food waste with Bacillus safensis YM1. Bioresour. Technol. 2024, 397, 130475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Wang, N.; Yang, N.; Chen, X.; Liu, Q.; Wang, Z.; Shi, J.; Liu, L. Multivariate insights into the effects of inoculating thermophilic aerobic bacteria on the biodegradation of food waste: Process properties, organic degradation and bacterial communities. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2023, 29, 102968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-González, J.A.; Estrella-González, M.J.; Lerma-Moliz, R.; Jurado, M.M.; Suárez-Estrella, F.; López, M.J. Industrial Composting of Sewage Sludge: Study of the Bacteriome, Sanitation, and Antibiotic-Resistant Strains. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 784071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Wang, X.; Liu, L.; Le, B.; Tan, C.; Dong, C.; Yao, X.; Hu, B. Fungi play a crucial role in sustaining microbial networks and accelerating organic matter mineralization and humification during thermophilic phase of composting. Environ. Res. 2024, 254, 119155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Yu, C.; Wang, X.; Yin, S.; Chang, X. Additives improved saprotrophic fungi for formation of humic acids in chicken manure and corn stover mix composting. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 346, 126626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.-y.; Fan, B.-q.; Hu, Q.-x.; Yin, Z.-w. Effect of inoculation with Penicillium expansum on the microbial community and maturity of compost. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 11189–11193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Shen, Y.; Ding, J.; Luo, W.; Zhou, H.; Cheng, H.; Wang, H.; Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; Xu, P.; et al. High oil content inhibits humification in food waste composting by affecting microbial community succession and organic matter degradation. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 376, 128832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Singh, V.S.; Sahu, P.K.; Mishra, T.; Chaurasia, R.; Tripathi, V.; Jaiswal, D.K. Role of Microbial Enzymes in Agro-waste Composting: A Comprehensive Review. Waste Biomass Valorization 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Cheruiyot, N.K.; Bui, X.T.; Ngo, H.H. Composting and its application in bioremediation of organic contaminants. Bioengineered 2022, 13, 1073–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, R.; Yang, X.; Sun, H.; Ye, X.; Liao, H.; Qin, S.; Chen, Z.; Zhou, S. Extensive production and evolution of free radicals during composting. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 359, 127491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Wei, Y.; Zhou, K.; Gao, X.; Chang, Y.; Zhang, K.; Deng, J.; Zhan, Y.; Li, J.; Li, R.; et al. Regulating pH and Phanerochaete chrysosporium inoculation improved the humification and succession of fungal community at the cooling stage of composting. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 384, 129291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Raw Materials | Moisture (%) | Organic Matter (%) | TN (%) | TK (%) | TP (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sheep manure | 40.13 ± 1.25 | 31.54 ± 0.89 | 2.24 ± 0.11 | 0.78 ± 0.01 | 1.17 ± 0.01 |

| Saw dust | 10.23 ± 1.03 | 75.30 ± 1.99 | 0.36 ± 0.01 | 0.09 ± 0.00 | 0.01 ± 0.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhou, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Li, C.; Chai, X.; He, S.; Lei, Y.; Fu, W. Cellulolytic Microbial Inoculation Enhances Sheep Manure Composting by Improving Nutrient Retention and Reshaping Microbial Community Structure. Agronomy 2026, 16, 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010079

Zhou Z, Zhang Y, Li C, Chai X, He S, Lei Y, Fu W. Cellulolytic Microbial Inoculation Enhances Sheep Manure Composting by Improving Nutrient Retention and Reshaping Microbial Community Structure. Agronomy. 2026; 16(1):79. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010079

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Ze, Yincui Zhang, Changning Li, Xiaohong Chai, Shanmu He, Yang Lei, and Weigang Fu. 2026. "Cellulolytic Microbial Inoculation Enhances Sheep Manure Composting by Improving Nutrient Retention and Reshaping Microbial Community Structure" Agronomy 16, no. 1: 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010079

APA StyleZhou, Z., Zhang, Y., Li, C., Chai, X., He, S., Lei, Y., & Fu, W. (2026). Cellulolytic Microbial Inoculation Enhances Sheep Manure Composting by Improving Nutrient Retention and Reshaping Microbial Community Structure. Agronomy, 16(1), 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010079