Effect of Zinc Application on Maize Dry Matter, Zinc Uptake, and Soil Microbial Community Grown Under Different Paddy Soil pH

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sites Description

2.2. Experimental Management and Design

2.3. Plant Sampling and Measuring

2.4. Soil Sampling and Measuring

2.5. DNA Extraction, PCR Amplification, and Sequencing

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

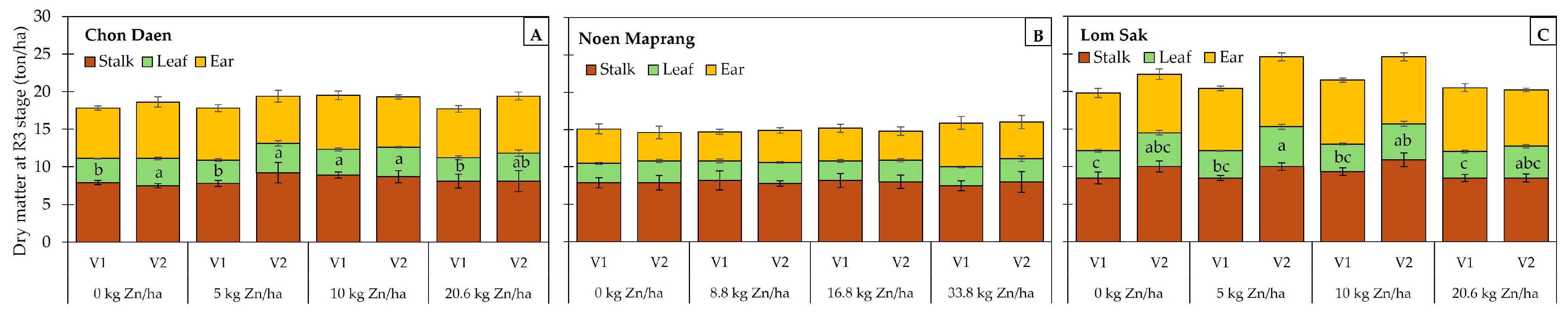

3.1. Dry Matter Accumulation and Shoot Zn Uptake at the Milking (R3) Stage

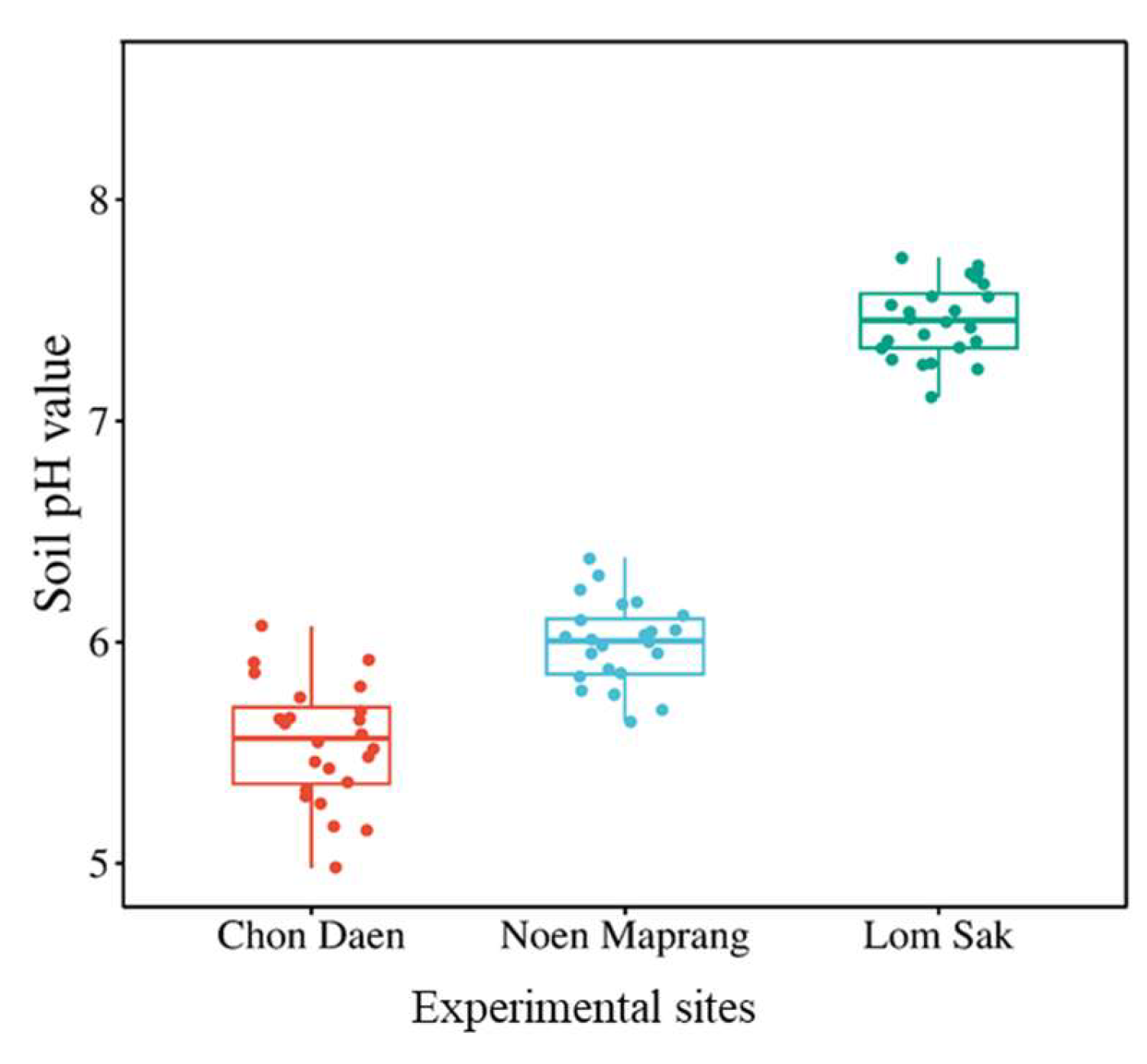

3.2. Soil Zn Concentration and Soil pH

3.3. Soil Bacterial and Archaeal Community

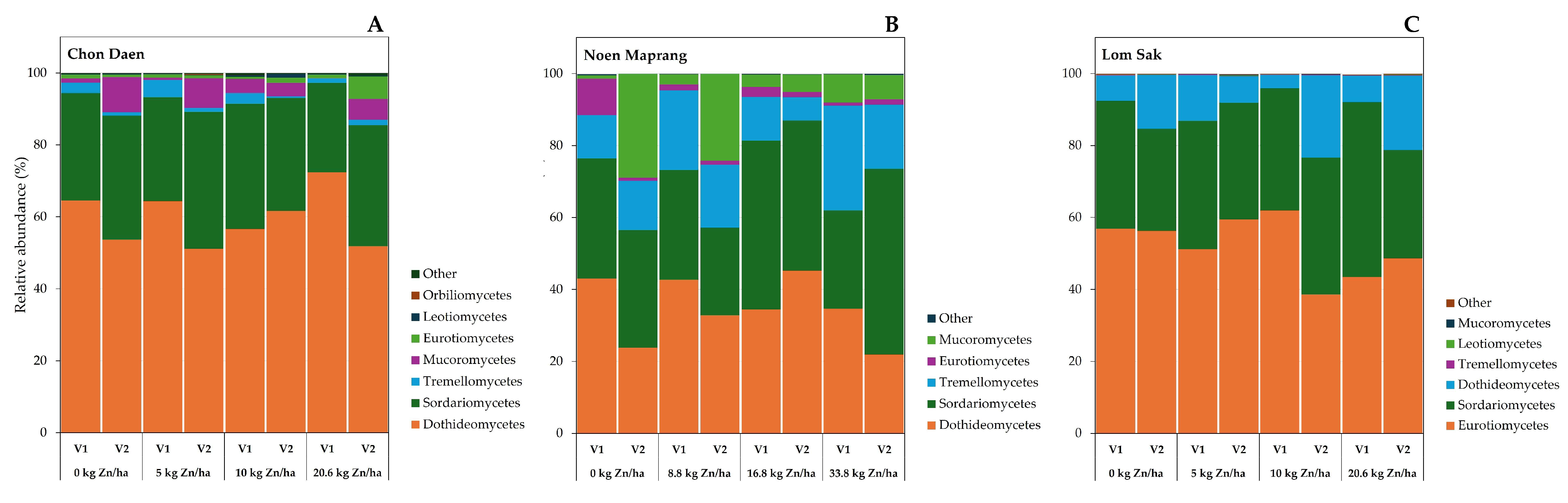

3.4. Soil Fungal Community

3.5. Correlation Between Soil Microbial Community and Environmental Factors

4. Discussion

4.1. Effect of Zn Application on Biomass, Zn Accumulation, and Soil Zn Concentration

4.2. Effect of Zn Application on Soil Microbial Community Under Different Soil pH

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alloway, B.J. Zinc in Soils and Crop Nutrition, 2nd ed.; International Zinc Association and International Fertilizer Industry Association: Paris, France, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Stanton, C.; Sanders, D.; Krämer, U.; Podar, D. Zinc in Plants: Integrating Homeostasis and Biofortification. Mol. Plant 2022, 15, 65–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalal, A.; da Silva Oliveira, C.E.; Fernandes, G.C.; Horschut, B.; Furlani, E.; Henrique, P.; Galindo, F.S.; Martins, I.; Carvalho, M. Nanozinc and Plant Growth-Promoting Bacteria Improve Biochemical and Metabolic Attributes of Maize in Tropical Cerrado. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 13, 1046642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jalal, A.; Júnior, E.F.; Teixeira Filho, M.C.M. Interaction of Zinc Mineral Nutrition and Plant Growth-Promoting Bacteria in Tropical Agricultural Systems: A Review. Plants 2024, 13, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mutambu, D.; Kihara, J.; Mucheru-Muna, M.; Bolo, P.; Kinyua, M. Maize Grain Yield and Grain Zinc Concentration Response to Zinc Fertilization: A Meta-Analysis. Heliyon 2023, 9, e16040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alloway, B.J. Soil Factors Associated with Zinc Deficiency in Crops and Humans. Environ. Geochem. Health 2009, 31, 537–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisawapipat, W.; Janlaksana, Y.; Christl, I. Zinc Solubility in Tropical Paddy Soils: A Multi-Chemical Extraction Technique Study. Geoderma 2017, 301, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulte, E. Understanding Plant Nutrients Soil and Applied Zinc; Cooperative Extension Publications; University of Wisconsin: Madison, WI, USA, 2002; Available online: https://corn.aae.wisc.edu/Management/pdfs/a2528.pdf (accessed on 29 April 2020).

- Bender, R.R.; Haegele, J.W.; Ruffo, M.L.; Below, F.E. Nutrient Uptake, Partitioning, and Remobilization in Modern, Transgenic Insect-Protected Maize Hybrids. Agron. J. 2013, 105, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Impa, S.M.; Morete, M.J.; Ismail, A.M.; Schulin, R.; Johnson-Beebout, S.E. Zn Uptake, Translocation and Grain Zn Loading in Rice (Oryza sativa L.) Genotypes Selected for Zn Deficiency Tolerance and High Grain Zn. J. Exp. Bot. 2013, 64, 2739–2751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters, B.M.; Uauy, C.; Dubcovsky, J.; Grusak, M.A. Wheat (Triticum aestivum) NAM Proteins Regulate the Translocation of Iron, Zinc, and Nitrogen Compounds from Vegetative Tissues to Grain. J. Exp. Bot. 2009, 60, 4263–4274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Singh, A.; Gill, H.K. Zinc Biofortification through Biofertilizers, Foliar and Soil Application in Maize (Zea mays L.). J. Exp. Agric. Int. 2024, 46, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khongchiu, P.; Wongkaew, A.; Murase, J.; Sajjaphan, K.; Rakpenthai, A.; Kumdee, O.; Nakasathien, S. Zinc Application Enhances Biomass Production, Grain Yield, and Zinc Uptake in Hybrid Maize Cultivated in Paddy Soil. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.-Y.; Zhang, W.; Liu, Y.-M.; Chen, X.-P.; Zou, C.-Q. Soil Application of Zinc Fertilizer Increases Maize Yield by Enhancing the Kernel Number and Kernel Weight of Inferior Grains. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.-Y.; Zhang, W.; Yan, P.; Chen, X.-P.; Zhang, F.-S.; Zou, C.-Q. Soil Application of Zinc Fertilizer Could Achieve High Yield and High Grain Zinc Concentration in Maize. Plant Soil 2017, 411, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takrattanasaran, N.; Chanchareonsook, J.; Johnson, P.G.; Thongpae, S.; Sarobol, E. Amelioration of Zinc Deficiency of Corn in Calcareous Soils of Thailand: Zinc Sources and Application Methods. J. Plant Nutr. 2013, 36, 1275–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Cao, W.; Chen, X.; Yu, B.-G.; Lang, M.; Chen, X.; Zou, C. The Responses of Soil Enzyme Activities, Microbial Biomass and Microbial Community Structure to Nine Years of Varied Zinc Application Rates. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 737, 140245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarrete, A.A.; Mellis, E.V.; Escalas, A.; Lemos, L.B.; Henrique, F.; Quaggio, J.A.; Zhou, J.; Tsai, S.M. Zinc Concentration Affects the Functional Groups of Microbial Communities in Sugarcane-Cultivated Soil. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2017, 236, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Office of Agricultural Economics. Agricultural Statistics of Thailand 2024; Office of Agricultural Economics, Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives: Bangkok, Thailand, 2025; pp. 29–33. Available online: https://oae.go.th/uploads/files/2025/05/06/13e8089a3f69ea96.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Kadiyala, M.D.M.; Mylavarapu, R.S.; Li, Y.C.; Reddy, G.B.; Reddy, M.D. Impact of Aerobic Rice Cultivation on Growth, Yield, and Water Productivity of Rice-Maize Rotation in Semiarid Tropics. Agron. J. 2012, 104, 1757–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Agriculture. Fertilizer Recommendation Based on Soil Chemical Analysis for Economic Crops. Department of Agriculture, Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives. Available online: https://www.doa.go.th/apsrdo/?page_id=3241 (accessed on 2 November 2021).

- Liu, H.; Gan, W.; Rengel, Z.; Zhao, P. Effects of Zinc Fertilizer Rate and Application Method on Photosynthetic Characteristics and Grain Yield of Summer Maize. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2016, 16, 95162016005000045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, W.L.; Norvell, W.A. Development of a DTPA Soil Test for Zinc, Iron, Manganese, and Copper. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1978, 42, 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IRRI. Statistical Tool for Agricultural Research (STAR). Biometrics and Breeding Informatics, PBGB Division. International Rice Research Institute: Los Baños, Philippines. Available online: https://news.irri.org/2013/08/irri-biometrics-group-releases.html (accessed on 1 March 2020).

- Gupta, N.; Ram, H.; Kumar, B. Mechanism of Zinc Absorption in Plants: Uptake, Transport, Translocation and Accumulation. Rev. Environ. Sci. Bio/Technol. 2016, 15, 89–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, P.A.; Sainz, R.; Wyngaard, N.; Eyherabide, M.; Calvo, R.; Salvagiotti, F.; Correndo, A.A.; Barbagelata, P.A.; Espósito, G.P.; Colazo, J.C.; et al. Can Edaphic Variables Improve DTPA-Based Zinc Diagnosis in Corn? Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2017, 81, 556–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuesta, N.M.; Wyngaard, N.; Rozas, H.S.; Calvo, N.R.; Carciochi, W.; Eyherabide, M.; Colazo, J.C.; Barraco, M.; Guertal, E.A.; Barbieri, P. Determining Mehlich-3 and DTPA Extractable Soil Zinc Optimum Economic Threshold for Maize. Soil Use Manag. 2020, 37, 736–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Patel, K.C.; Ramani, V.P.; Shukla, A.K.; Behera, S.K.; Patel, R.A. Influence of Different Rates and Frequencies of Zn Application to Maize–Wheat Cropping on Crop Productivity and Zn Use Efficiency. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saboor, A.; Ali, M.A.; Ahmed, N.; Skalicky, M.; Danish, S.; Fahad, S.; Hassan, F.; Hassan, M.M.; Brestic, M.; EL Sabagh, A.; et al. Biofertilizer-Based Zinc Application Enhances Maize Growth, Gas Exchange Attributes, and Yield in Zinc-Deficient Soil. Agriculture 2021, 11, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.S.; Zhou, B.; Han, Z.; Liu, S.; Ding, C.; Jia, F.; Zeng, W. Microbial Mechanism of Zinc Fertilizer Input on Rice Grain Yield and Zinc Content of Polished Rice. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 962246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, P.K.; Dey, A.; Singh, V.K.; Dwivedi, B.S.; Singh, R.K.; Rajanna, G.A.; Babu, S.; Rathore, S.S.; Shekhawat, K.; Rai, P.K.; et al. Changes in Microbial Community Structure and Yield Responses with the Use of Nano-Fertilizers of Nitrogen and Zinc in Wheat–Maize System. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Zhou, S.; Zhang, L.; Qin, C. Pronounced Temporal Changes in Soil Microbial Community and Nitrogen Transformation Caused by Benzalkonium Chloride. J. Environ. Sci. 2023, 126, 827–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyszkowska, J.; Boros-Lajszner, E.; Borowik, A.; Baćmaga, M.; Kucharski, J.; Tomkiel, M. Implication of Zinc Excess on Soil Health. J. Environ. Sci. Health Part B 2016, 51, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahlawat, V.; Ahalawat, N.; Boora, N.; Dadarwal, R.S.; Dhanda, D.; Sangwan, P.; Kumar, V.; Kumar, R.; Yadav, P.K. Impact of Long Term Integrated Nutrient Management Practices on Soil Bacterial Diversity: A 16S RRNA-Based Metagenomic Approach. bioRxiv 2025, 639006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukhatem, Z.F.; Merabet, C.; Tsaki, H. Plant Growth Promoting Actinobacteria, the Most Promising Candidates as Bioinoculants? Front. Agron. 2022, 4, 849911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Qin, H.; Wang, J.; Yao, D.; Zhang, L.; Guo, J.; Zhu, B. Immediate Response of Paddy Soil Microbial Community and Structure to Moisture Changes and Nitrogen Fertilizer Application. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1130298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Sites | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chon Daen | Noen Maprang | Lom Sak | ||

| Geographic | Latitude (°N) | 16°12′28.0′′ | 16°26′10.2′′ | 16°45′00.4′′ |

| Longitude (°E) | 100°51′17.4′′ | 100°41′12.7′′ | 101°10′17.9′′ | |

| Climatic | Mean temperature (°C) | 28.4 | 28.8 | 27.6 |

| Total precipitation (mm) | 243.2 | 128.7 | 272.2 | |

| Characteristics | Experimental Sites | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Chon Daen | Noen Maprang | Lom Sak | |

| Soil type | clay | clay loam | clay |

| Sand (%) | 30 | 42 | 34 |

| Silt (%) | 26 | 28 | 24 |

| Clay (%) | 44 | 30 | 42 |

| pH (1:1) | 5.8 | 6.7 | 7.8 |

| Soil organic matter (%) | 0.35 | 0.91 | 1.63 |

| Available phosphorus (mg/kg) | 1.50 | 20.75 | 26.84 |

| Exchangeable potassium (mg/kg) | 27.50 | 62.18 | 60.45 |

| DTPA-Zn (mg/kg) | 0.55 | 0.87 | 0.53 |

| Experimental Sites | Zn Application Rate (kg Zn/ha) | Variety | Mean | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SW 5731 | SW 5819 | |||

| Chon Daen | 0 | 1.52 ± 0.28 bc | 1.46 ± 0.20 c | 1.49 ± 0.22 B |

| 5 | 2.23 ± 0.62 abc | 1.60 ± 0.05 bc | 1.91 ± 0.52 B | |

| 10 | 1.63 ± 0.47 bc | 1.67 ± 0.34 bc | 1.65 ± 0.37 B | |

| 20.6 | 4.50 ± 2.03 a | 3.41 ± 1.94 ab | 3.96 ± 1.88 A | |

| Mean | 2.47 ± 1.57 | 2.03 ± 1.19 | ||

| Source of variation | Zn application rate | ** | Variety (Var) | ns |

| Zn × Var | ** | |||

| Noen Maprang | 0 | 1.54 ± 0.35 bc | 1.37 ± 0.05 c | 1.46 ± 0.24 C |

| 8.8 | 2.85 ± 1.11 abc | 2.06 ± 0.52 bc | 2.46 ± 0.89 B | |

| 16.8 | 2.12 ± 0.43 abc | 2.64 ± 0.89 abc | 2.38 ± 0.69 BC | |

| 33.8 | 4.50 ± 1.01 a | 3.89 ± 1.40 ab | 4.20 ± 1.14 A | |

| Mean | 2.75 ± 1.35 | 2.49 ± 1.2 | ||

| Source of variation | Zn application rate | ** | Variety | ns |

| Zn × Var | ** | |||

| Lom Sak | 0 | 0.52 ± 0.11 d | 1.46 ± 0.90 bcd | 0.99 ± 0.77 B |

| 5 | 0.80 ± 0.12 cd | 1.21 ± 0.58 bcd | 1.00 ± 0.44 B | |

| 10 | 1.63 ± 0.45 abc | 1.70 ± 0.73 abc | 1.67 ± 0.75 AB | |

| 20.6 | 2.43 ± 0.78 a | 1.89 ± 0.61 ab | 2.16 ± 0.69 A | |

| Mean | 1.35 ± 1.06 | 1.56 ± 0.67 | ||

| Source of variation | Zn application rate | ** | Variety | ns |

| Zn × Var | ** | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Khongchiu, P.; Murase, J.; Wongkaew, A.; Sajjaphan, K.; Kumdee, O.; Rakpenthai, A.; Nakasathien, S. Effect of Zinc Application on Maize Dry Matter, Zinc Uptake, and Soil Microbial Community Grown Under Different Paddy Soil pH. Agronomy 2026, 16, 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010078

Khongchiu P, Murase J, Wongkaew A, Sajjaphan K, Kumdee O, Rakpenthai A, Nakasathien S. Effect of Zinc Application on Maize Dry Matter, Zinc Uptake, and Soil Microbial Community Grown Under Different Paddy Soil pH. Agronomy. 2026; 16(1):78. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010078

Chicago/Turabian StyleKhongchiu, Phanuphong, Jun Murase, Arunee Wongkaew, Kannika Sajjaphan, Orawan Kumdee, Apidet Rakpenthai, and Sutkhet Nakasathien. 2026. "Effect of Zinc Application on Maize Dry Matter, Zinc Uptake, and Soil Microbial Community Grown Under Different Paddy Soil pH" Agronomy 16, no. 1: 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010078

APA StyleKhongchiu, P., Murase, J., Wongkaew, A., Sajjaphan, K., Kumdee, O., Rakpenthai, A., & Nakasathien, S. (2026). Effect of Zinc Application on Maize Dry Matter, Zinc Uptake, and Soil Microbial Community Grown Under Different Paddy Soil pH. Agronomy, 16(1), 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010078