Identification of Major QTLs and Candidate Genes Determining Stem Strength in Soybean

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials, Growth Condition and Phenotyping

2.2. DNA Extraction and Sequencing

2.3. Analysis of Genomic Variants Between the Parental Varieties

2.4. Analysis of BSA-Seq Data and Preliminary Identification of QTLs

2.5. RNA Extraction, Sequencing and Analysis

2.6. Linkage Mapping and Candidate Gene Exploration

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

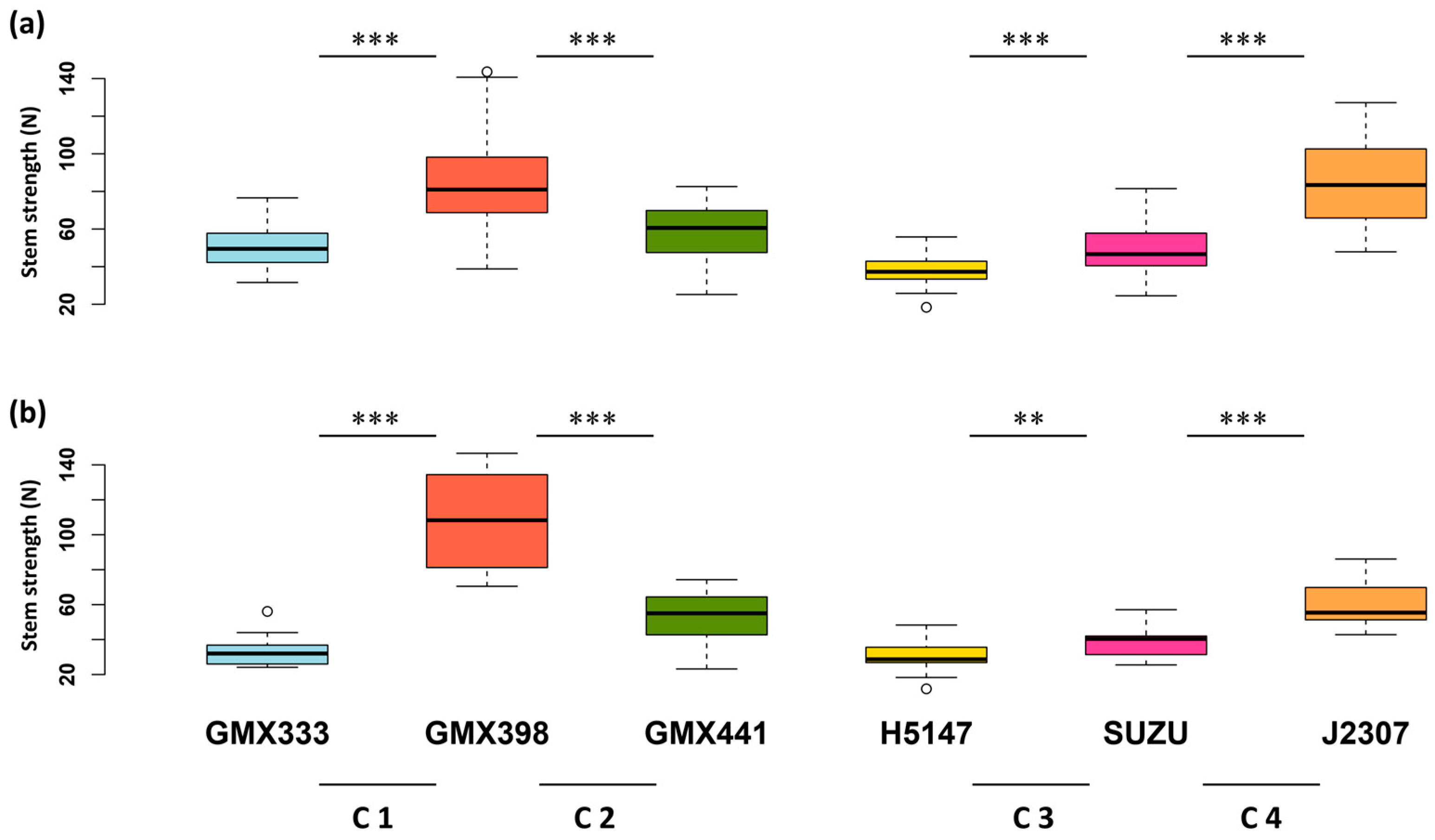

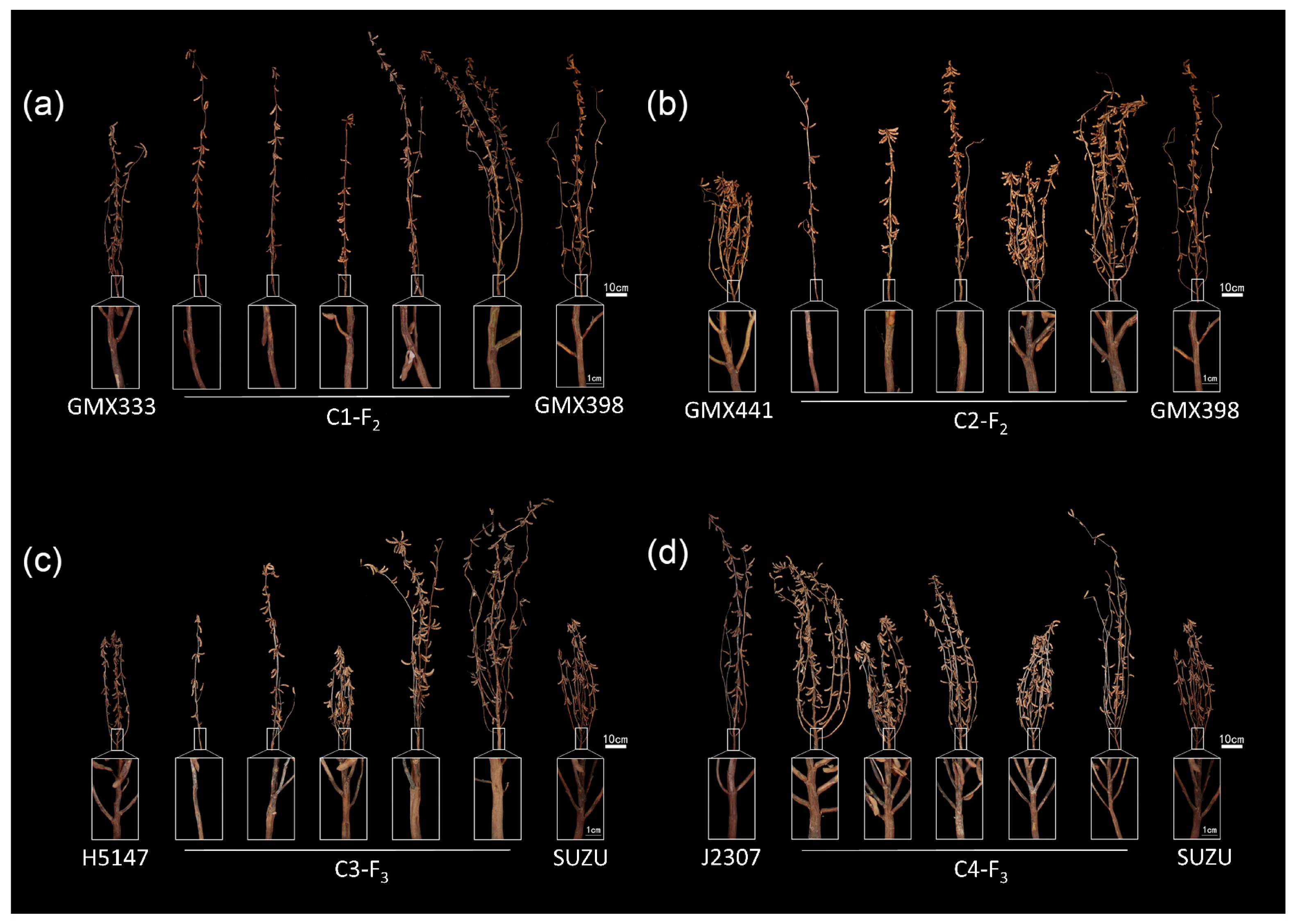

3.1. Comparative Analysis of Stem Strength Among Six Soybean Varieties

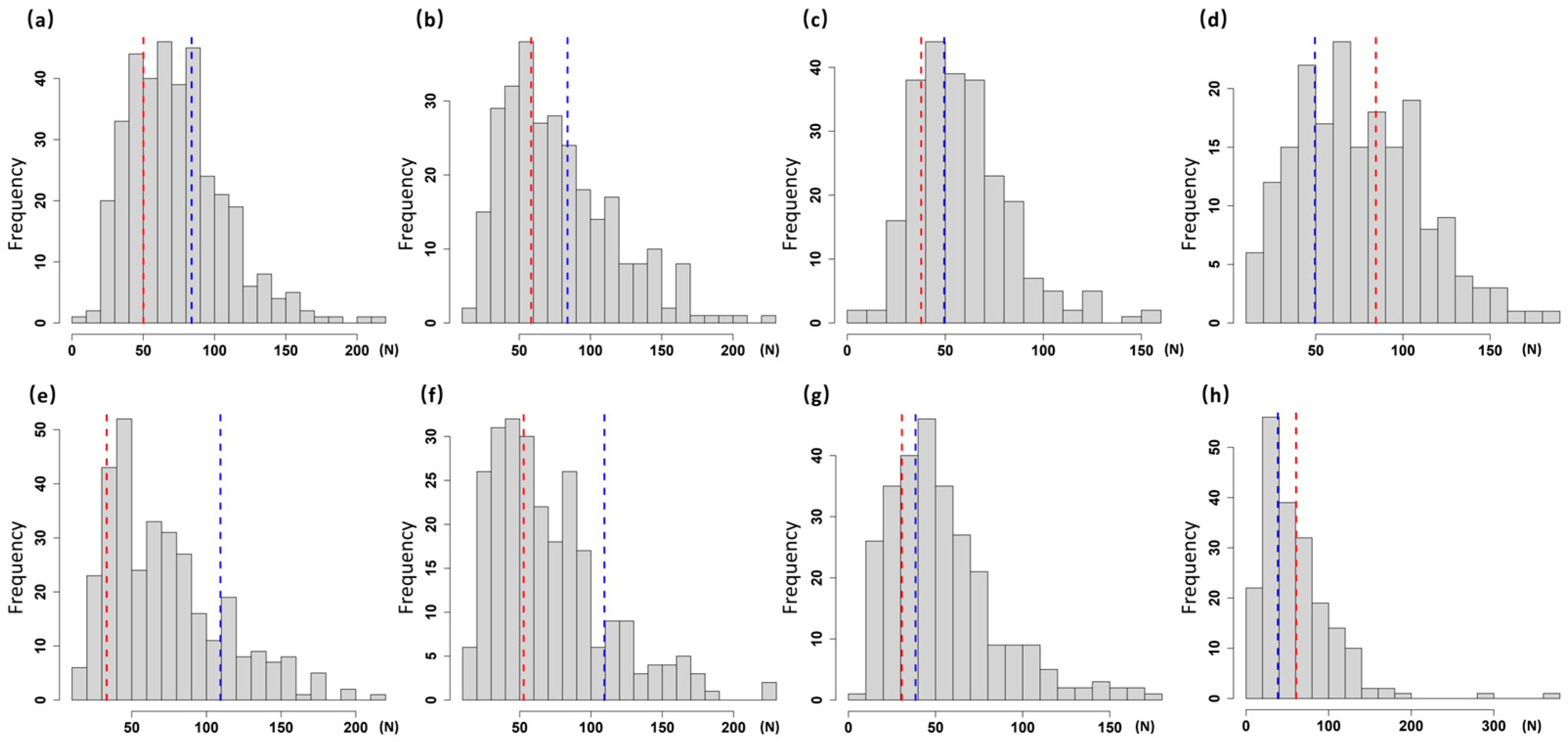

3.2. Analysis of Stem Strength Variation in Four Segregating Populations

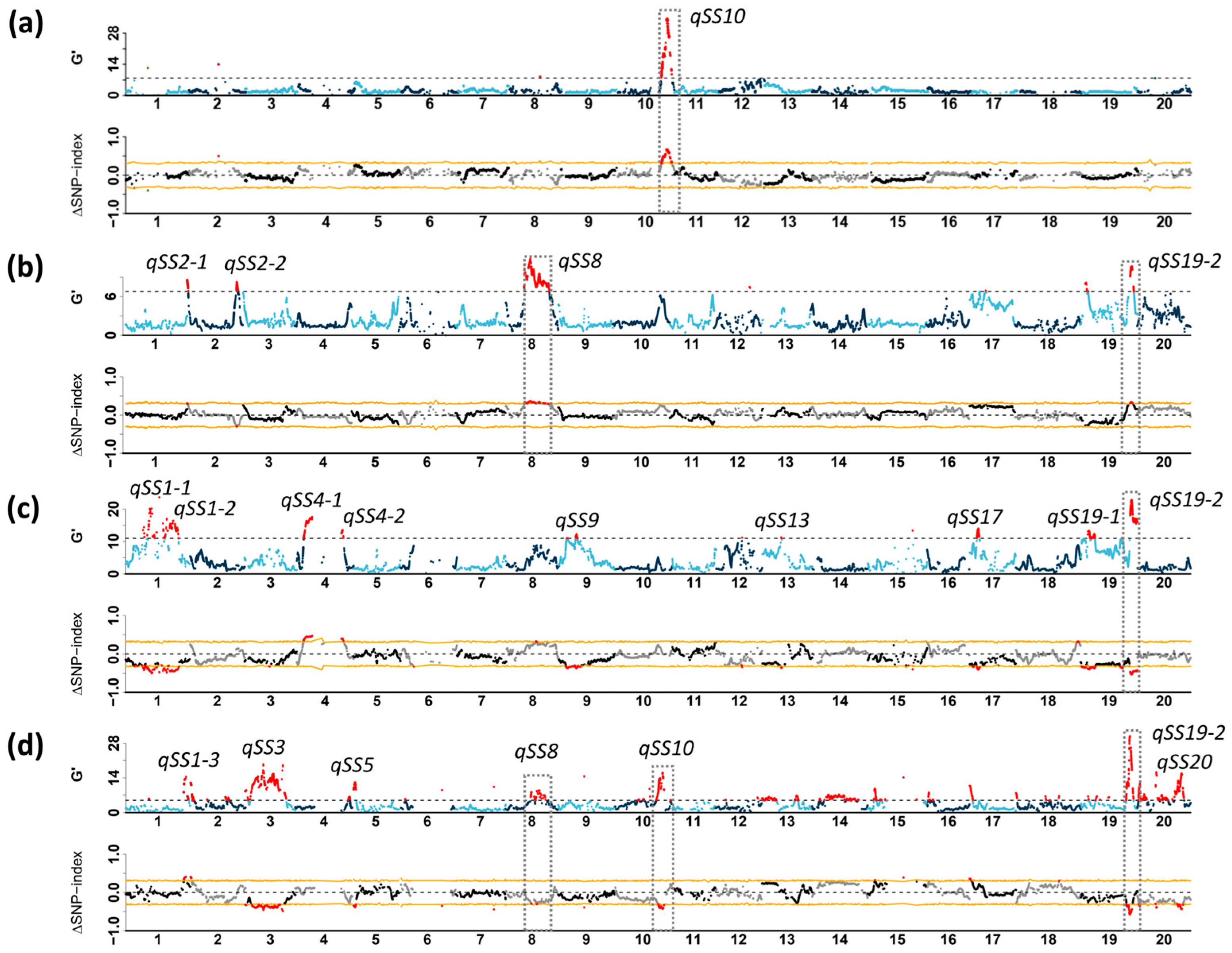

3.3. Identification of Genetic Loci for Stem Strength Through BSA-Seq

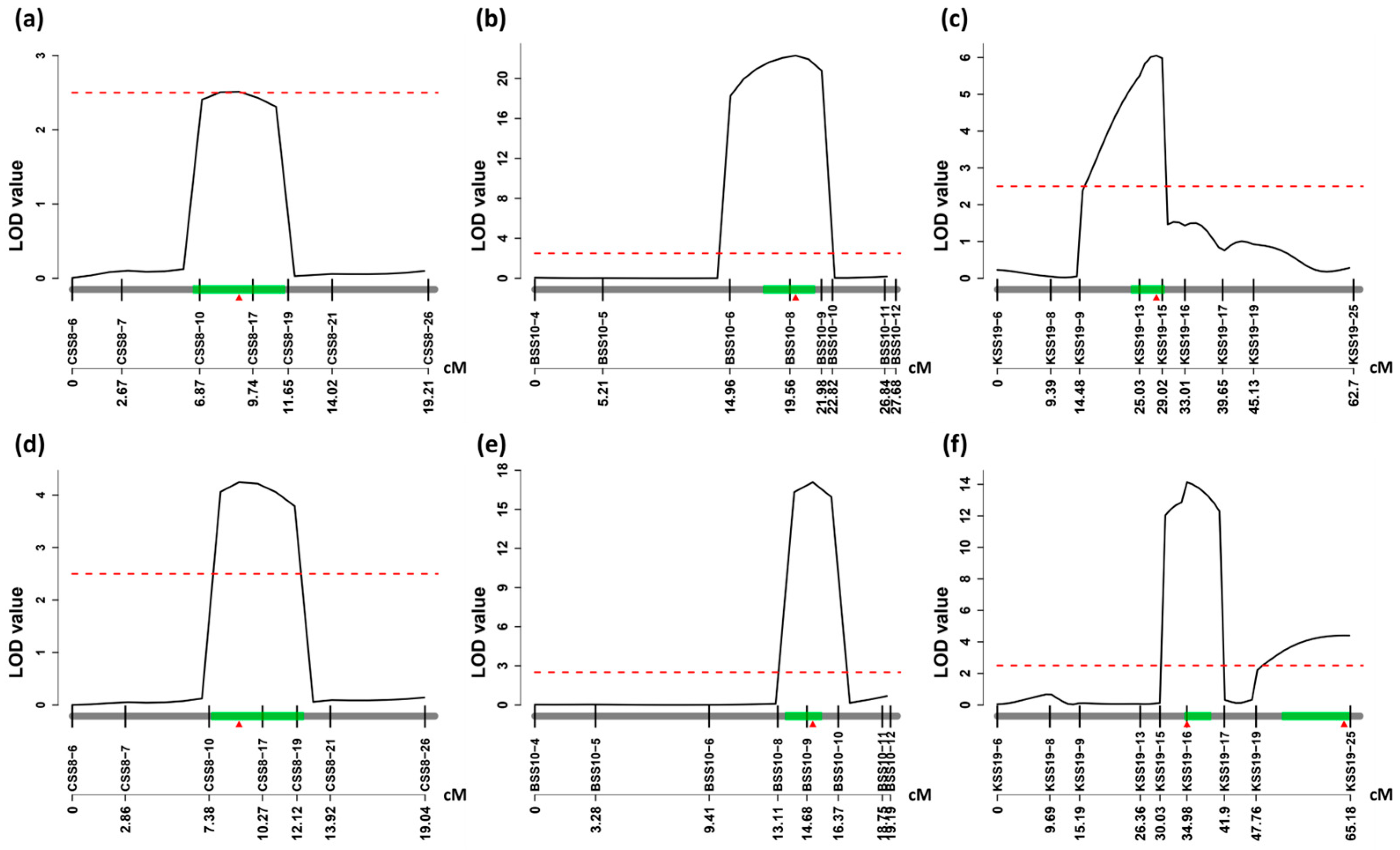

3.4. Linkage Mapping of Three Stable QTLs

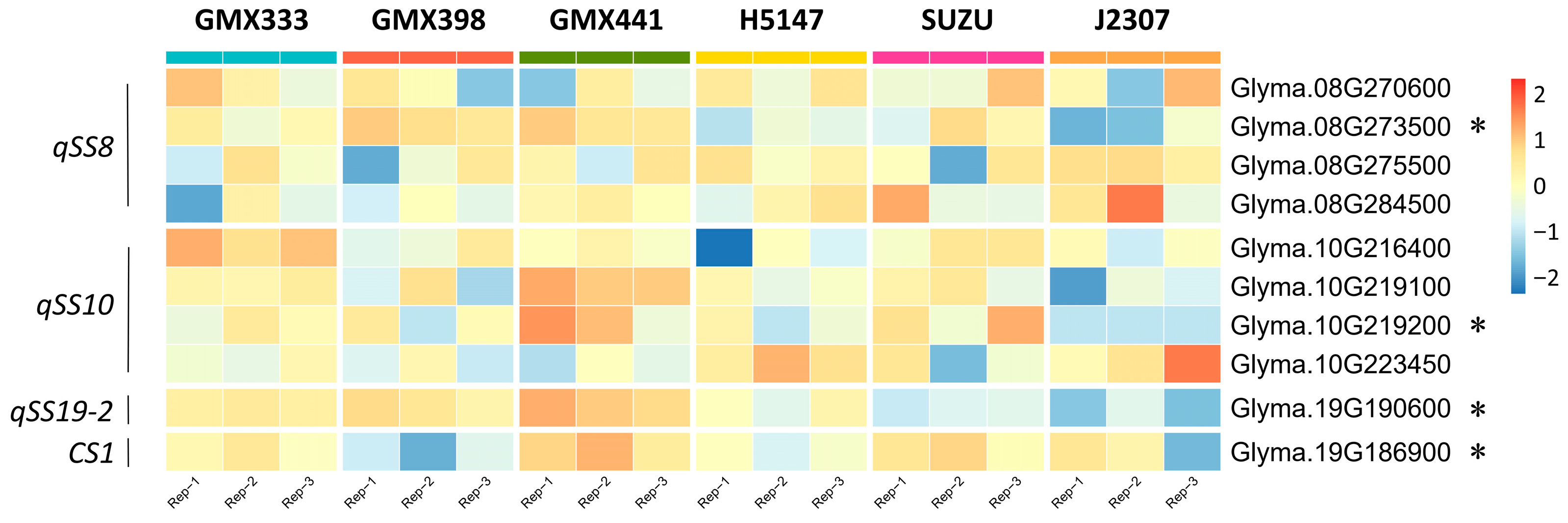

3.5. Genetic Variation and Expression Differentiation in Candidate Genes of Stable QTLs

4. Discussion

4.1. Identification of Novel Stable Major QTL for Stem Strength in Soybean

4.2. Genetic Connections Between Stem Strength and Logging in Soybean

4.3. Prediction of Candidate Genes in qSS8, qSS10, and qSS19-2

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Graham, P.H.; Vance, C.P. Legumes: Importance and constraints to greater use. Plant Physiol. 2003, 131, 872–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Messina, M. Perspective: Soybeans Can Help Address the Caloric and Protein Needs of a Growing Global Population. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 909464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, H.W.; Yang, M.Y.; Yan, L.; Hu, X.Z.; Hong, H.L.; Zhang, X.; Sun, R.J.; Wang, H.R.; Wang, X.B.; Liu, L.K.; et al. Identification of tolerance to high density and lodging in short petiolate germplasm M657 and the effect of density on yield-related phenotypes of soybean. J. Integr. Agr. 2023, 22, 434–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.L.; Zhang, M.; Feng, F.v; Tian, Z.X. Toward a “Green Revolution” for Soybean. Mol. Plant 2020, 13, 688–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Board, J. Reduced lodging for soybean in low plant population is related to light quality. Crop Sci. 2001, 41, 379–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Mauro, G.; Rotundo, J.L. Lodging dynamics and seed yield for two soybean genotypes with contrasting lodging-susceptibility. Eur. J. Agron. 2025, 163, 127445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Zeng, D.; Zhao, C.; Han, D.; Li, S.; Wen, M.; Liang, X.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Z.; Ali, S.; et al. Identification of QTLs and Key Genes Enhancing Lodging Resistance in Soybean Through Chemical and Physical Trait Analysis. Plants 2024, 13, 3470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S.; Lee, T.G. Integration of lodging resistance QTL in soybean. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 6540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y.A.; Chen, T.X.; Zhao, C.C.; Zhou, M.X. Improving Crop Lodging Resistance by Adjusting Plant Height and Stem Strength. Agronomy 2021, 11, 2421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.-s.; Pu, G.-f.; Ma, L.; He, W.-j.; Wu, J.-j. Study on Lodging Resistance Evaluation Method of Soybean Based on Model Method. Soybean Sci. 2023, 42, 64–69. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, D.U.; Reynolds, T.P.S.; Ramage, M.H. The strength of plants: Theory and experimental methods to measure the mechanical properties of stems. J. Exp. Bot. 2017, 68, 4497–4516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, S.; Samanfar, B.; Morrison, M.J.; Bekele, W.A.; Torkamaneh, D.; Rajcan, I.; O’Donoughue, L.; Belzile, F.; Cober, E.R. Genome-wide association study to identify soybean stem pushing resistance and lodging resistance loci. Can. J. Plant Sci. 2021, 101, 663–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.F.; Shan, Z.H.; Sha, A.H.; Wu, B.D.; Yang, Z.L.; Chen, S.L.; Zhou, R.; Zhou, X.N. Quantitative trait loci analysis of stem strength and related traits in soybean. Euphytica 2011, 179, 485–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Cao, H.; Yao, H.; Zhuang, Y.; Chen, B.; Zhang, C.; Li, X.; Zhang, D. Identification of a major QTL and its candidate genes controlling stem strength in soybean via QTL mapping and GWAS. Crop J. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.; Liu, T.; Iqbal, N.; Brestic, M.; Pang, T.; Mumtaz, M.; Shafiq, I.; Li, S.X.; Wang, L.; Gao, Y.; et al. Effects of lignin, cellulose, hemicellulose, sucrose and monosaccharide carbohydrates on soybean physical stem strength and yield in intercropping. Photoch Photobio Sci. 2020, 19, 462–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, W.; Li, F.C.; Lu, J.C.; Wang, D.L.; Chen, M.K.; Tang, L.; Xu, Z.J.; Chen, W.F. Biochar application enhanced rice biomass production and lodging resistance via promoting co-deposition of silica with hemicellulose and lignin. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 855, 158818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.; Iqbal, N.; Rahman, T.; Liu, T.; Brestic, M.; Safdar, M.E.; Asghar, M.A.; Farooq, M.U.; Shafiq, I.; Ali, A.; et al. Shade effect on carbohydrates dynamics and stem strength of soybean genotypes. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2019, 162, 374–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhu, J.M.; Lin, Q.Q.; Li, X.J.; Teng, N.J.; Li, Z.S.; Li, B.; Zhang, A.M.; Lin, J.X. Effects of stem structure and cell wall components on bending strength in wheat. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2006, 51, 815–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.P.; Li, M.; Yin, Y.; Liu, Y.; Gan, X.K.; Mu, X.H.; Li, H.Q.; Li, J.K.; Li, H.C.; Zheng, J.; et al. Spatial accumulation of lignin monomers and cellulose underlying stalk strength in maize. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 214, 108918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.M.; Zhang, W.J.; Ding, Y.F.; Zhang, J.W.; Cambula, E.D.; Weng, F.; Liu, Z.H.; Ding, C.Q.; Tang, S.; Chen, L.; et al. Shading Contributes to the Reduction of Stem Mechanical Strength by Decreasing Cell Wall Synthesis in Japonica Rice (Oryza sativa L.). Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, A.; Asghar, M.A.; Javed, H.H.; Ullah, A.; Cheng, B.; Xu, M.; Wang, W.Y.; Liu, C.Y.; Rahman, A.; Iqbal, T.; et al. Optimum nitrogen improved stem breaking resistance of intercropped soybean by modifying the stem anatomical structure and lignin metabolism. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2023, 199, 107720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z.Y.; Zhang, L.Y.; Kong, K.K.; Kong, J.J.; Ji, R.H.; Liu, Y.; Liu, J.; Li, H.Y.; Ren, Y.L.; Zhou, W.B.; et al. Creeping Stem 1 regulates directional auxin transport for lodging resistance in soybean. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2025, 23, 377–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, Y.H.; Cheng, Z.Y.; Yang, X.J.; Yang, S.X.; Tang, K.Q.; Yu, H.; Gao, J.S.; Zhang, Y.H.; Leng, J.T.; Zhang, W.; et al. LRM3 positively regulates stem lodging resistance by degradating MYB6 transcriptional repressor in soybean. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2025, 23, 2978–2993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.Q.; Xu, Y.H. Bulk segregation analysis in the NGS era: A review of its teenage years. Plant J. 2022, 109, 1355–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takagi, H.; Abe, A.; Yoshida, K.; Kosugi, S.; Natsume, S.; Mitsuoka, C.; Uemura, A.; Utsushi, H.; Tamiru, M.; Takuno, S.; et al. QTL-seq: Rapid mapping of quantitative trait loci in rice by whole genome resequencing of DNA from two bulked populations. Plant J. 2013, 74, 174–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Khine, E.E.; Thi, K.M.; Nyein, E.E.; Huang, L.K.; Lin, L.H.; Xie, X.F.; Lin, M.H.W.; Oo, K.T.; Moe, M.M.; et al. Multi-environment BSA-seq using large F3 populations is able to achieve reliable QTL mapping with high power and resolution: An experimental demonstration in rice. Crop J. 2024, 12, 549–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.R.; Abdelghany, A.M.; Azam, M.; Qi, J.; Li, J.; Feng, Y.; Liu, Y.T.; Feng, H.Y.; Ma, C.Y.; Gebregziabher, B.S.; et al. Mining candidate genes underlying seed oil content using BSA-seq in soybean. Ind. Crop Prod. 2023, 194, 116308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Yuan, M.; Xia, H.; He, L.; Ma, J.; Wang, M.; Zhao, H.; Hou, L.; Zhao, S.; Li, P.; et al. BSA-seq and genetic mapping reveals AhRt2 as a candidate gene responsible for red testa of peanut. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2022, 135, 1529–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Win, K.T.; Vegas, J.; Zhang, C.Y.; Song, K.; Lee, S. QTL mapping for downy mildew resistance in cucumber via bulked segregant analysis using next-generation sequencing and conventional methods. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2017, 130, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Jiang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Xie, J.; Wang, Q.; Zheng, H.; Hou, L.; Xiong, X.; Xin, D.; et al. Combined Linkage Mapping and BSA to Identify QTL and Candidate Genes for Plant Height and the Number of Nodes on the Main Stem in Soybean. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 21, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.D.; Liu, J.J.; Huang, J.; Xiao, Q.; Hayward, A.; Li, F.Y.; Gong, Y.Y.; Liu, Q.; Ma, M.; Fu, D.H.; et al. Mapping and Identifying Candidate Genes Enabling Cadmium Accumulation in Revealed by Combined BSA-Seq and RNA-Seq Analysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 10163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Ding, X.Y.; Zeng, Y.; Xie, G.; Yu, J.X.; Jin, M.Y.; Liu, L.; Li, P.Y.; Zhao, N.; Dong, Q.L.; et al. Identification of Multiple Genetic Loci and Candidate Genes Determining Seed Size and Weight in Soybean. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolger, A.M.; Lohse, M.; Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2114–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Handsaker, B.; Wysoker, A.; Fennell, T.; Ruan, J.; Homer, N.; Marth, G.; Abecasis, G.; Durbin, R.; Genome Project Data Processing, S. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 2078–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danecek, P.; Auton, A.; Abecasis, G.; Albers, C.A.; Banks, E.; DePristo, M.A.; Handsaker, R.E.; Lunter, G.; Marth, G.T.; Sherry, S.T.; et al. The variant call format and VCFtools. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 2156–2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cingolani, P.; Platts, A.; Wang, L.L.; Coon, M.; Nguyen, T.; Wang, L.; Land, S.J.; Lu, X.; Ruden, D.M. A program for annotating and predicting the effects of single nucleotide polymorphisms, SnpEff: SNPs in the genome of Drosophila melanogaster strain w1118; iso-2; iso-3. Fly 2012, 6, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Schulz-Trieglaff, O.; Shaw, R.; Barnes, B.; Schlesinger, F.; Kallberg, M.; Cox, A.J.; Kruglyak, S.; Saunders, C.T. Manta: Rapid detection of structural variants and indels for germline and cancer sequencing applications. Bioinformatics 2016, 32, 1220–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansfeld, B.N.; Grumet, R. QTLseqr: An R Package for Bulk Segregant Analysis with Next-Generation Sequencing. Plant Genome 2018, 11, 180006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Li, H.H.; Zhang, L.Y.; Wang, J.K. QTL IciMapping: Integrated software for genetic linkage map construction and quantitative trait locus mapping in biparental populations. Crop J. 2015, 3, 269–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.S.; Diers, B.W.; Hyten, D.L.; Mian, M.A.R.; Shannon, J.G.; Nelson, R.L. Identification of positive yield QTL alleles from exotic soybean germplasm in two backcross populations. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2012, 125, 1353–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinprecht, Y.; Poysa, V.W.; Yu, K.; Rajcan, I.; Ablett, G.R.; Pauls, K.P. Seed and agronomic QTL in low linolenic acid, lipoxygenase-free soybean (Glycine max (L.) Merrill) germplasm. Genome 2006, 49, 1510–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzman, P.S.; Diers, B.W.; Neece, D.J.; Martin, S.K.S.; Leroy, A.R.; Grau, C.R.; Hughes, T.J.; Nelson, R.L. QTL associated with yield in three backcross-derived populations of soybean. Crop Sci. 2007, 47, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Jun, T.H.; Michel, A.P.; Mian, M.A.R. SNP markers linked to QTL conditioning plant height, lodging, and maturity in soybean. Euphytica 2015, 203, 521–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, M.E.; Orf, J.H.; Liu, L.J.; Dong, Z.; Rajcan, I. Genetic basis of soybean adaptation to North American vs. Asian mega-environments in two independent populations from Canadian x Chinese crosses. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2013, 126, 1809–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Bailey, M.A.; Mian, M.A.R.; Carter, T.E.; Ashley, D.A.; Hussey, R.S.; Parrott, W.A.; Boerma, H.R. Molecular markers associated with soybean plant height, lodging, and maturity across locations. Crop Sci. 1996, 36, 728–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.; Ma, Y.; Wu, S.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Z.; Yang, R.; Hu, G.; Zhou, Z.; Yu, H.; Zhang, M.; et al. Genome-wide association studies dissect the genetic networks underlying agronomical traits in soybean. Genome Biol. 2017, 18, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuong, T.D.; Sonah, H.; Meinhardt, C.G.; Deshmukh, R.; Kadam, S.; Nelson, R.L.; Shannon, J.G.; Nguyen, H.T. Genetic architecture of cyst nematode resistance revealed by genome-wide association study in soybean. BMC Genom. 2015, 16, 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.D.; Pfeiffer, T.W.; Cornelius, P.L. Soybean QTL for yield and yield components associated with Glycine soja alleles. Crop Sci. 2008, 48, 571–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keim, P.; Diers, B.W.; Olson, T.C.; Shoemaker, R.C. RFLP mapping in soybean: Association between marker loci and variation in quantitative traits. Genetics 1990, 126, 735–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.Y.; Yang, Y.M.; Jia, L.; Liu, X.Q.; Xu, H.Q.; Lv, H.Y.; Huang, Z.W.; Zhang, D. QTL mapping of the genetic basis of stem diameter in soybean. Planta 2021, 253, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Yang, Q.C.; Chen, Y.J.; Liu, K.L.; Zhang, Z.Q.; Xiong, Y.J.; Yu, H.; Yu, Y.D.; Wang, J.; Song, J.; et al. QTL mapping and genomic selection of stem and branch diameter in soybean (Glycine max L.). Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1388365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.K.; Tang, W.Q.; Wu, W.R. Optimization of BSA-seq experiment for QTL mapping. G3-Genes. Genom. Genet. 2022, 12, jkab370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capron, A.; Chang, X.F.; Hall, H.; Ellis, B.; Beatson, R.P.; Berleth, T. Identification of quantitative trait loci controlling fibre length and lignin content in Arabidopsis thaliana stems. J. Exp. Bot. 2013, 64, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor-Teeples, M.; Lin, L.; de Lucas, M.; Turco, G.; Toal, T.W.; Gaudinier, A.; Young, N.F.; Trabucco, G.M.; Veling, M.T.; Lamothe, R.; et al. An Arabidopsis gene regulatory network for secondary cell wall synthesis. Nature 2015, 517, 571–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, J.H.; Park, C.R.; Gong, Y.; Chung, M.S.; Nam, S.H.; Yun, H.S.; Kim, C.S. Rhamnogalacturonan lyase 1 (RGL1), as a suppressor of E3 ubiquitin ligase Arabidopsis thaliana ring zinc finger 1 (AtRZF1), is involved in dehydration response to mediate proline synthesis and pectin rhamnogalacturonan-I composition. Plant J. 2024, 119, 942–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bischoff, V.; Selbig, J.; Scheible, W.R. Involvement of TBL/DUF231 proteins into cell wall biology. Plant Signal Behav. 2010, 5, 1057–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries, L.; Vanholme, R.; Van Acker, R.; De Meester, B.; Sundin, L.; Boerjan, W. Stacking of a low-lignin trait with an increased guaiacyl and 5-hydroxyguaiacyl unit trait leads to additive and synergistic effects on saccharification efficiency in Arabidopsis thaliana. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2018, 11, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Guo, L.Y.; Morgan, J.; Dudareva, N.; Chapple, C. Transcript and metabolite network perturbations in lignin biosynthetic mutants of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2022, 190, 2828–2846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phookaew, P.; Ma, Y.; Suzuki, T.; Stolze, S.C.; Harzen, A.; Sano, R.; Nakagami, H.; Demura, T.; Ohtani, M. Active protein ubiquitination regulates xylem vessel functionality. Plant Cell 2024, 36, 3298–3317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, M.; Davis, E.; Gardner, D.; Cai, X.; Wu, Y. Involvement of AtLAC15 in lignin synthesis in seeds and in root elongation of Arabidopsis. Planta 2006, 224, 1185–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthet, S.; Demont-Caulet, N.; Pollet, B.; Bidzinski, P.; Cezard, L.; Le Bris, P.; Borrega, N.; Herve, J.; Blondet, E.; Balzergue, S.; et al. Disruption of LACCASE4 and 17 results in tissue-specific alterations to lignification of Arabidopsis thaliana stems. Plant Cell 2011, 23, 1124–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Zhang, C.H. The Mode of Action of Endosidin20 Differs from That of Other Cellulose Biosynthesis Inhibitors. Plant Cell Physiol. 2020, 61, 2139–2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.C.; Kim, J.Y.; Ko, J.H.; Kang, H.; Han, K.H. Identification of direct targets of transcription factor MYB46 provides insights into the transcriptional regulation of secondary wall biosynthesis. Plant Mol. Biol. 2014, 85, 589–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Gray, W.M. SAUR Proteins as Effectors of Hormonal and Environmental Signals in Plant Growth. Mol. Plant 2015, 8, 1153–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Watanabe, S.; Uchiyama, T.; Kong, F.; Kanazawa, A.; Xia, Z.; Nagamatsu, A.; Arai, M.; Yamada, T.; Kitamura, K.; et al. The soybean stem growth habit gene Dt1 is an ortholog of Arabidopsis TERMINAL FLOWER1. Plant Physiol. 2010, 153, 198–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| QTL | Chromosome | Region (Mb) | Max G’ | q-Value | ΔSNP Index | Population | Positive Allele * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| qSS1-1 | Chr1 | 20.67–26.23 | 20.14 | 5.27 × 10−3 | −0.50 | C3-F3 | H5147 |

| qSS1-2 | Chr1 | 39.73–47.15 | 16.37 | 4.13 × 10−3 | −0.46 | C3-F3 | H5147 |

| qSS1-3 | Chr1 | 52.62–53.96 | 14.40 | 1.25 × 10−3 | 0.41 | C4-F3 | SUZU |

| qSS2-1 | Chr2 | 0.00–0.90 | 8.57 | 3.67 × 10−3 | 0.30 | C2-F2 | GMX398 |

| qSS2-2 | Chr2 | 44.28–44.53 | 8.24 | 4.86 × 10−3 | −0.30 | C2-F2 | GMX441 |

| qSS3 | Chr3 | 5.84–33.68 | 19.41 | 1.69 × 10−4 | −0.49 | C4-F3 | J2307 |

| qSS4-1 | Chr4 | 6.35–13.80 | 17.53 | 2.76 × 10−3 | 0.48 | C3-F3 | SUZU |

| qSS4-2 | Chr4 | 40.22–41.97 | 13.48 | 5.81 × 10−3 | 0.40 | C3-F3 | SUZU |

| qSS5 | Chr5 | 1.34–3.29 | 12.28 | 1.06 × 10−5 | −0.39 | C4-F3 | J2307 |

| qSS8 | Chr8 | 16.92–38.38 | 11.86, 8.24 | 3.19 × 10−3, 4.98 × 10−3 | 0.34, −0.31 | C2-F2, C4-F3 | GMX398, J2307 |

| qSS9 | Chr9 | 14.96–16.48 | 12.24 | 8.18 × 10−3 | −0.37 | C3:F3 | H5147 |

| qSS10 | Chr10 | 39.93–49.31 | 34.40, 16.00 | 1.26 × 10−4, 1.15 × 10−3 | 0.66, −0.43 | C1-F2, C4-F3 | GMX398, J2307 |

| qSS13 | Chr13 | 17.02–17.25 | 11.26 | 9.96 × 10−3 | −0.37 | C3-F3 | H5147 |

| qSS17 | Chr17 | 6.76–8.85 | 13.96 | 5.93 × 10−3 | −0.41 | C3:F3 | H5147 |

| qSS19-1 | Chr19 | 6.51–8.56 | 13.29 | 5.71 × 10−3 | −0.40 | C3:F3 | H5147 |

| qSS19-2 | Chr19 | 44.91–45.67 | 10.69, 22.80, 30.85 | 1.97 × 10−3, 1.70 × 10−3, 3.55 × 10−4 | 0.33, −0.54, −0.57 | C2:F2, C3:F3, C4:F3 | GMX441, H5147, J2307 |

| qSS20 | Chr20 | 35.87–40.82 | 15.80 | 2.43 × 10−4 | 0.44 | C4:F3 | SUZU |

| QTL | Chr | Position (bp) a | LOD | PVE(%) b | Left Marker | Right Marker | Population/ Size c | Length (cM) | Positive Allele d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| qSS8 | 8 | 34,203,399–38,888,594 | 2.51 | 5.66 | CSS8-10 | CSS8-17 | C2-F2/284 | 19.21 | GMX398 |

| 4.25 | 9.08 | CSS8-10 | CSS8-17 | C2-F3/254 | 19.03 | GMX398 | |||

| qSS10 | 10 | 44,824,364–45,886,465 | 22.30 | 25.15 | BSS10-8 | BSS10-10 | C1-F2/357 | 27.67 | GMX398 |

| 17.08 | 23.31 | BSS10-9 | BSS10-10 | C1-F3/295 | 19.19 | GMX398 | |||

| qSS19-2 | 19 | 45,099,480–46,637,650 | 6.05 | 14.21 | KSS19-13 | KSS19-15 | C4-F2/193 | 62.7 | J2307 |

| 14.13 | 19.93 | KSS19-16 | KSS19-17 | C4-F3/183 | 65.18 | J2307 | |||

| 4.40 | 5.70 | KSS19-19 | KSS19-25 | SUZU |

| QTL | ID | At Locus | Name a | DEG b | Variation c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| qSS8 | Glyma.08G270600 | AT2G23910 | / | intron/upstream/downstream (C2), Intron (C3, C4) | |

| Glyma.08G273500 | AT5G65670 | IAA9 | C4 | missense/downstream (C2) | |

| Glyma.08G275500 | AT2G22620 | RGL1 | 3′ UTR/intron/downstream (C2), downstream (C3), NA (C4) | ||

| Glyma.08G275600 | AT2G22620 | RGL1 | NA | upstream/downstream (C2) | |

| Glyma.08G284500 | AT1G60790 | TBL2 | upstream/downstream (C2) | ||

| qSS10 | Glyma.10G215700 | AT5G54160 | OMT1 | NA | |

| Glyma.10G216400 | AT1G71930 | VND7 | |||

| Glyma.10G219100 | AT5G48100 | LAC15 | upstream (C1) | ||

| Glyma.10G219200 | AT5G48100 | LAC15 | C4 | upstream (C1) | |

| Glyma.10G223450 | AT5G64740 | CESA6 | |||

| qSS19-2 | Glyma.19G190600 | AT5G03760 | CSLA9 | C3 | intron/upstream (C2), upstream/downstream (C3), downstream (C4) |

| Glyma.19G194300(DT1) | AT5G03840 | TFL1 | NA | upstream/downstream (C2), intron/upstream (C3), | |

| Glyma.19G195200 | AT2G36210 | SAUR45 | NA | upstream/downstream (C2), 5′ UTR/3′ UTR/upstream/start lost & conservative in-frame deletion (C3) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, X.; Liu, L.; Cheng, Y.; Ding, X.; Yu, J.; Li, P.; Gu, H.; Xu, W.; Jiang, W.; Xu, C.; et al. Identification of Major QTLs and Candidate Genes Determining Stem Strength in Soybean. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2905. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122905

Wang X, Liu L, Cheng Y, Ding X, Yu J, Li P, Gu H, Xu W, Jiang W, Xu C, et al. Identification of Major QTLs and Candidate Genes Determining Stem Strength in Soybean. Agronomy. 2025; 15(12):2905. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122905

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Xinyue, Liu Liu, Yuting Cheng, Xiaoyang Ding, Jiaxin Yu, Peiyuan Li, Hesong Gu, Wenbo Xu, Wenwen Jiang, Chunming Xu, and et al. 2025. "Identification of Major QTLs and Candidate Genes Determining Stem Strength in Soybean" Agronomy 15, no. 12: 2905. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122905

APA StyleWang, X., Liu, L., Cheng, Y., Ding, X., Yu, J., Li, P., Gu, H., Xu, W., Jiang, W., Xu, C., & Zhao, N. (2025). Identification of Major QTLs and Candidate Genes Determining Stem Strength in Soybean. Agronomy, 15(12), 2905. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122905