Abstract

Soybean (Glycine max) is a globally important grain and oil crop, but its yield and quality are severely limited by soybean cyst nematode (SCN, Heterodera glycines Ichinohe), a devastating soil-borne pathogen. Here, we evaluated SCN race 3 resistance in 306 soybean germplasms and combined a genome-wide association study (GWAS) with transcriptome analysis to identify key resistance-related genes. GWAS using 30× resequencing data (632,540 SNPs) revealed 77 significant quantitative trait loci (QTLs) associated with SCN resistance, while transcriptome comparison between the extreme resistant accession Dongnong L10 and susceptible Heinong 37 identified 4185 upregulated and 3195 downregulated genes. Integrating these results, we characterized the GmRF2-like gene as a candidate resistance gene. Subcellular localization showed GmRF2-like encodes a nuclear-localized protein. Functional validation via soybean hairy root transformation demonstrated that overexpression of GmRF2-like significantly inhibits SCN race 3 infection. Collectively, our findings confirm that GmRF2-like plays a positive role in soybean resistance to SCN race 3, providing critical insights for dissecting the molecular mechanism of SCN resistance and facilitating the development of resistant soybean varieties.

1. Introduction

Soybean cyst nematode disease (Heterodera glycines, SCN) is distributed worldwide and is a common soil-borne disease during soybean cultivation, which severely restricts soybean yield [1]. This disease can be favored by various factors such as climate and soil conditions, and it leads to a reduction in soybean planting area yield [2]. In China, this disease has a wide spread range and a fast transmission speed. During the transmission process, physiological races have also undergone differentiation. The disease occurs seriously in the major soybean-producing areas of Northeast China and the Huang-Huai region in China [3]. Specifically, physiological races SCN 1 and SCN 4 are mainly distributed in the Huang-Huai region of China, while physiological races SCN 3 and SCN 4 are mainly distributed in Northeast China [4,5]. The J2 stage of the larval phase causes the most severe damage to soybean. Larvae secrete cellulase and pectinase through their mouthparts to destroy the cell walls of soybean roots, and further form “syncytia” to continuously absorb nutrients from soybean [6]. Under normal circumstances, it causes a 20–30% reduction in soybean yield, and in severe cases, it can lead to a total crop failure [7]. At present, the control of SCN mainly focuses on measures such as agricultural cultivation improvement, resistant variety breeding, chemical agents, and biological control. Currently, the most economical method is crop rotation, but crop rotation cannot fundamentally eliminate SCN [8]. Chemical agents cause great harm to soil fertility and microbial environment [2]. For biological control, once it is promoted to the field, it will be affected by various external extreme environments, temperature, humidity and other factors, which will lead to the instability of biocontrol bacteria. Therefore, its promotion and application have become very limited [9]. Consequently, the most effective method is the cultivation of resistant soybean germplasm resources. The traditional breeding cycle is relatively long, and molecular biology-assisted breeding is one of the most economical and effective methods for obtaining soybean. Currently, the internationally recognized SCN-resistant germplasms include PI88788 (with high copy number of rhg1-b), PI 548402 (Peking, carrying rhg1-a and Rhg4), PI 437654, and PI 567516C (qSCN10, HG Type 1.3.5.6.7), etc. The domestically recognized varieties include Wuzhai Black Soybean, Huipi Branch Black Soybean, Kangxian 2, etc.

In molecular genetics, soybean resistance to SCN is mainly controlled by recessive genes Rgh1, Rgh2, Rgh3 and dominant genes Rgh4, Rgh5. Rgh1 is located on chromosome 18 and exhibits incomplete dominance [10], while Rgh4 is located on chromosome 8 and exhibits complete dominant inheritance [11,12]. A large number of QTL studies have confirmed and recognized that Rgh1 and Rgh4 are the main genetic resistance loci for SCN [13,14]. Many studies have focused on the development of molecular markers around these gene loci. However, currently, Rgh1 and Rgh4 can only explain 60% of the genetic variation [15]. Currently, the application of Rgh1 in breeding is still constrained by linkage drag, as Rgh1 is tightly linked to several unfavorable agronomic traits, such as seed size and protein content [16]. The α-SNAP protein encoded by Rgh1 exerts resistance by interfering with the formation of feeding sites in SCN, while Rgh4 mediates resistance through regulating the expression of cell wall modification-related genes. Both loci belong to “structural defense-type” resistance with relatively simple mechanisms of action. Long-term exclusive reliance on these two loci has led to an increase in the frequency of virulent alleles in SCN populations [17,18]. A large part of the remaining variation needs to be further explored and developed.

bZIP (basic Leucine Zipper) transcription factors are widely present in eukaryotes as regulatory proteins, and they are named after their conserved basic region and leucine zipper domain. The bZIP structural motif consists of a basic region and a leucine zipper. The leucine zipper is composed of an α-helix, in which leucine residues appear every 7 amino acids [19]. This structure stabilizes the dimerization process through interaction with parallel leucine zipper domains [20]. Dimerization of the leucine zipper forms a pair of adjacent basic regions, which bind to DNA and undergo conformational changes. By binding to specific DNA sequences in the promoter region of genes, these basic regions regulate the expression of downstream genes and participate in various life activities such as stress response and metabolic balance [21]. They specifically recognize the ACGT core sequence in gene promoters (for example, CACGTG, G-box, C-box, etc.), and this region is the key determinant of DNA binding specificity [22]. In plants, bZIP transcription factors regulate gene expression by binding to the promoters of target genes and recruiting co-activators or co-repressors. They can improve the stress resistance of crops and thus have important application value [23]. In recent years, a large number of studies have confirmed that bZIP transcription factors are involved in the regulatory response of plants to abiotic and biotic stresses. Yang et al. systematically elaborated their roles in plant stress growth, development, and disease response, and the disease resistance process mediated by them is closely related to the signaling pathways of plant hormones such as SA, JA, and ethylene [24]. Among these hormones, SA mainly mediates the defense pathway against biotrophic pathogens, while JA and ethylene dominate the defense pathways against necrotrophic pathogens and insects [25]. At present, in-depth studies on members of the bZIP family have been conducted in species such as potato [26], soybean GmbZIP15 [27], pepper CabZIP2 [28], and cassava MebZIP3 and MebZIP5 [29]. The expression of GmbZIP15 can be induced by SA, JA, ABA, and ethylene (all of which are signal molecules for pathogen invasion), and its expression level is significantly upregulated after pathogen invasion. Transgenic plants overexpressing GmbZIP15, CabZIP2, and RcbZIP17 show significantly higher tolerance to Sclerotinia sclerotiorum, Phytophthora sojae, Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria (causal agent of tomato bacterial spot), and gray mold compared with wild-type plants. In contrast, their RNAi lines are more susceptible to diseases, with a significant decrease in disease resistance. MebZIP3 and MebZIP5 also play a positive regulatory role in the defense against cassava bacterial blight. Pathogen invasion can rapidly induce the expression of bZIP transcription factors. Through enhancing the expression of downstream defense-related genes, mediating plant hormone signaling pathways, and activating various metabolic pathways to produce defense proteins, metabolites, and plant hormones, bZIP transcription factors thereby enhance the ability of plants to resist biotic stresses [29]. It has been reported that ATHB8, a member of the class III HD-ZIP transcription factor family, acts as a key downstream regulator of the CLE signaling pathway in syncytium formation. It promotes the establishment of cyst nematode feeding sites by inducing root cells to enter a quiescent state; overexpression of miR165a, which inhibits the expression of class III HD-ZIP genes, significantly impairs the female development of the sugar beet cyst nematode [30]. To date, no research on bZIP genes in the context of SCN disease has been reported. Therefore, it has become increasingly important to analyze the molecular mechanism of the GmRF2-like gene in SCN disease.

In this study, a total of 306 domestic and international soybean germplasm resources were utilized. Combined with the identification results of SCN 3 and resequencing data, a genome-wide association study (GWAS) was conducted using the compressed mixed linear model (cMLM). Furthermore, by integrating the RNA-Seq data of Dongnong L10 (an extreme SCN 3-resistant variety) and Heinong 37 (an extreme SCN 3-susceptible variety) under SCN 3 stress, the candidate gene GmRF2-like was identified. Subsequently, the GmRF2-like gene was cloned, and transgenic hairy roots with gene overexpression and gene editing were created. These experimental materials were then transplanted into SCN 3-infested soil, followed by the identification of their disease resistance. This research explored the function of the GmRF2-like gene and also provided a reference for understanding the molecular mechanism by which the GmRF2-like gene participates in regulating resistance to SCN. Gaining in-depth insights into the molecular mechanism underlying the regulation of SCN resistance by the GmRF2-like gene will provide valuable resources for the subsequent development of efficiently and stably expressing soybean lines, which can be used to control SCN disease and ultimately improve soybean yield and quality.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

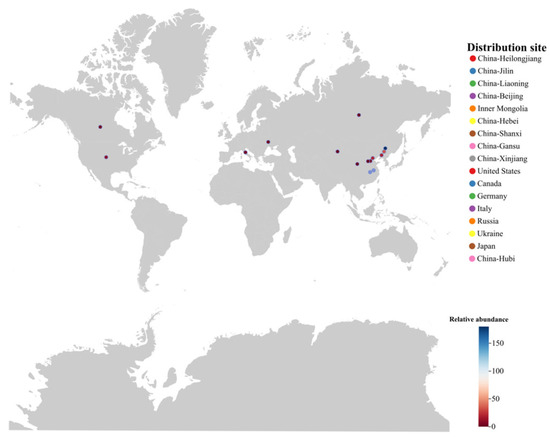

The 306 soybean germplasm resources (base on geographical diversity) employed in this study were primarily collected from various provinces in China (e.g., Heilongjiang, Liaoning, Jilin), supplemented by some accessions from countries like the United States, Russia, and Canada. All soybean germplasm materials were planted in 2023 at Xiangyang Farm of Northeast Agricultural University, located in Harbin City, Heilongjiang Province, China (45°45′16.2″ N, 126°54′39.6″ E). The field trial was conducted using a randomized block design, with a row length of 1 m, row spacing of 0.65 m, plant spacing of 0.06 m, and three replicates (Figure 1 and Supplementary Table S1).

Figure 1.

Geographical distribution of 306 soybean germplasm resources. Distribution site: Different colors indicate the distribution of enriched germplasm resources; Relative abundance: 0–150 represents the enrichment depth of germplasm resources. The darker the blue, the higher the abundance of germplasm resources; the darker the brown, the lower the abundance.

2.2. Experimental Methods

2.2.1. Evaluation of Resistance to Soybean Cyst Nematode

Before assessing soybean cyst nematode (SCN) resistance, soil samples were randomly collected from the SCN-infested nursery using a five-point sampling method. Each sample weighed 5 kg, with a sampling area of 0.8 m2 (2 m × 0.4 m) per sampling point. Following air-drying, cysts were isolated from the soil samples through an improved clean soil sieving technique. The number of cysts per 100 g of soil was counted under a 20× stereomicroscope to verify that the cyst density per unit area conformed to the requirements for resistance identification.

Soybean seeds free of disease spots and with intact seed coats were selected and sown in a field severely infested with SCN. Sixteen days after seedling emergence, 10 seedlings with uniform growth were chosen from each row. The entire root system of each selected seedling was excavated, and the residual soil adhering to the root surface was rinsed away with clean water. The number of female nematodes on each root system was observed under a stereomicroscope, and the Female Index (FI) was calculated based on the observed results. Based on the FI values, the soybean materials were classified for SCN resistance, and the identification criteria were referred to the method proposed by Riggs et al. [31].

The formula for the identification of the female index: [31]

Female Insect Index (FI) = average number of cysts in identified plants/average number of cysts in Lee 68 × 100%

In this study, different criteria for classifying SCN resistance were established via identification and analysis of the SCN Female Index (FI). SCN resistance was categorized into four grades, namely very resistant (VR), moderately resistant (MR), moderately susceptible (MS), and very susceptible (VS). It was observed that the SCN resistance of soybean germplasm showed an inverse correlation with the Female Index (FI)—the lower the FI value, the stronger the resistance [27]. The specific identification criteria were defined as follows: very resistant (VR): 0 < FI ≤ 10; moderately resistant (MR): 10 < FI ≤ 30; moderately susceptible (MS): 30 < FI ≤ 60; very susceptible (VS): FI > 60.

2.2.2. Transcriptome Sequencing Sample Preparation

The SCN 3-susceptible soybean cultivar ‘Dongnong 50’ was used as the host for SCN 3 propagation and planted in flower pots. Thirty days later, the intact root systems of host plants were excised and gently rinsed with tap water to eliminate residual soil. Cysts were collected using 40-mesh and 60-mesh sieves; those retained on the sieves were gently ground, and the cysts left on the 40-mesh sieve were rinsed with distilled water for collection. The harvested cysts were transferred into a 50 mL centrifuge tube, and after homogenization, an aliquot of the cyst-containing solution was taken. The egg concentration of the solution was determined through microscopic observation, and the solution was adjusted to a final egg concentration of 1800 eggs/mL [2].

Dongnong L10 and Heinong 37 were used as experimental groups inoculated with SCN 3, while the non-inoculated groups served as controls. Three biological replicates were set up, with 10 plants cultivated per replicate. The indoor temperature was kept at 25 °C and humidity at 70%. When the seedlings reached the V2 growth stage, they were inoculated with SCN 3, and each plant was given 2 mL of eggs suspension. Root tissues were sampled at 0 d and 14 d post-inoculation, and identified by the acid fuchsin staining method to verify the successful SCN 3 inoculation at 14 d [2].

2.2.3. Genome-Wide Association and RNA-Seq Analysis

Whole-genome resequencing (WGRS) was performed on 306 soybean germplasm resources using next-generation sequencing technology, with an average sequencing depth of approximately 30×. Sequencing-derived genome-wide SNP data were filtered with minor allele frequency (MAF) ≥ 5% and genotype missing rate ≤ 10% as quality control standards. Ultimately, 1,355,928 high-quality SNPs were obtained and applied to genome-wide association analysis. For GWAS analysis, the compressed mixed linear model (cMLM) in GAPIT v3.0 software was adopted, and SNPs with −log10(P) ≥ 5.5 were regarded as significant SNP loci [32].

Total RNA was extracted with an RNA extraction kit (Tiangen, Beijing, China). The integrity of RNA was confirmed to be good via agarose gel electrophoresis, and its purity, concentration, and integrity were further verified as satisfactory using a NanoDrop instrument (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Dreieich, Germany). mRNA enrichment was implemented (specifically, mRNA molecules containing poly(A) tails were captured with oligo(dT) magnetic beads). Following this, mRNA fragmentation was achieved through an enzymatic digestion approach. Adapter ligation and PCR amplification were performed in sequence, and a cDNA library was built using the Illumina TruSeq RNA Library Preparation Kit. The constructed library was loaded onto a high-throughput sequencer (Illumina platform), and RNA-Seq sequencing was conducted on cDNA samples with the Illumina HiSeq™ 2500 system, generating raw sequencing data (reads). Subsequent data analysis was carried out, encompassing procedures such as data quality control, alignment to the reference genome, calculation of gene expression levels, and differential expression analysis. In the differential expression analysis, differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified using the criteria of |log2(fold change)| ≥ 1 and adjusted p-value (padj) < 0.05. The padj was calculated via the Benjamini-Hochberg method to control the false discovery rate (FDR) [33].

2.2.4. Soybean Root System RNA Extraction and cDNA Synthesis

Disease-resistant soybean Dongnong L10 and disease-susceptible soybean Heinong 37 were planted in vermiculite. When the soybean grew to the second trifoliate stage (V2 stage), 2 g of fresh soybean root tissues was weighed, and total RNA from the soybean roots was extracted using TRIzol™ Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Shanghai, China). The RNA was subjected to reverse transcription using ReverTra Ace® qPCR RT Master Mix (TOYOBO, Tokyo, Japan) to synthesize cDNA, and the synthesized cDNA was finally stored at −20 °C [2].

2.2.5. qRT-PCR

Specific qRT-PCR primers for the GmRF2-like gene were designed using PrimerQuest™ Toolv2.2.3 (https://sg.idtdna.com/PrimerQuest/Home/Index, accessed on 1 February 2025), with GmActin4 (GenBank: AF049106) as the reference gene. The assay was conducted on a ROCGENE quantitative PCR instrument (Kunpeng Gene) under the Archimed X6 system, The designed system and procedures refer to (Supplementary Tables S11 and S12). Relative expression was calculated via the 2−ΔΔCT method, with CT values from three biological replicates [34].

2.2.6. Cloning of the GmRF2-like Gene and Recombination of the Expression Vector

Molecular cloning was performed using Dongnong L-10 cDNA as the template. For the designed system and procedures, refer to Supplementary Tables S11 and S12, and for the primers, refer to Supplementary Table S2. The target bands of the PCR products were detected by 2% gel electrophoresis, and the PCR products were sent to a biological company in Shanghai for sequencing.

The pCAMBIA3300 vector was linearized via digestion with Hind III enzyme (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA; Cat. No. R3104), while the pCAMBIA1302 vector was linearized through digestion with Nco I enzyme (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA; Cat. No. R3193), with both subjected to single-enzyme digestion (Supplementary Table S12). The reaction was run under the following program (Supplementary Table S11). The restriction enzyme digestion products were preserved at −20 °C in a refrigerator for subsequent experiments.

Cloned DNA was separately subjected to homologous recombination ligation with linearized pCAMBIA3300 and pCAMBIA1302 using the ClonExpress II One Step Cloning Kit (Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd., Nanjing, Jiangsu, China; Cat. No. C112-01). Prepare a 20 μL reaction system (Supplementary Table S12). After incubation in a water bath at 37 °C for 30 min, transformation into DH5α was performed. The successfully recombined plasmids were transferred into Agrobacterium K599.

For the construction of gene editing vectors, Reaction 1 was performed to conduct specific amplification (including 1 round-3d and 1 round-3b). On the basis of antisense 1, Reaction 2 was carried out for the second round of specific PCR amplification (2 round-3d and 2 round-3b). The amplification products from the two rounds were purified via gel extraction, and then recombined with the pYLCRISPR/Cas9 vector, followed by transformation into DH5α competent cells. After the transformation process, colony PCR amplification was performed using the universal primers SP_F/R. The resulting PCR amplification products were sent to Ruibo Biological Company for sequencing, so as to confirm that the target site had been recombined into the plasmid. Finally, the plasmids that were successfully recombined were transferred into Agrobacterium K599.

2.2.7. Generation of Transgenic Hairy Roots

SCN 3-susceptible soybean Dongnong 50 were planted in a vermiculite substrate. When the soybean plants grew to the vegetative emergence stage (VE stage), the junction of the soybean root systems was obliquely cut, and the plants were then transferred into a pre-prepared Agrobacterium tumefaciens bacterial solution containing plasmid K599 [2]. Plants were shaken at 28 °C (50 rpm) for 30 min, immersed in Agrobacterium tumefaciens suspension, and vacuum-treated (8–10 kPa) with 1 min vacuum/30 s standing, repeated 3 times. The control group was treated with immersion in distilled water, and the operation procedure was consistent with that of the infection and transformation group. The treated soybean seedlings were re-planted into vermiculite and cultured under conditions of 80% humidity and 25–28 °C until reaching the second trifoliate stage (V2 stage) [34]. These seedlings were then used for subsequent SCN resistance identification and analysis.

2.2.8. SCN Resistance Evaluation

V2-stage soybean were removed from vermiculite and thoroughly rinsed with clean water. Plants identified as transgenic (OE, KO) and control (WT) groups were transplanted together into soil infested with SCN 3, and cultured for 14 d under conditions of 25 °C and 40% soil moisture. Intact root systems were extracted from the SCN 3-infested soil and rinsed clean with water. The root systems were assessed via the acid fuchsin solution method (Supplementary Table S3). After staining, the root systems were taken out, evenly spread on a transparent pressing plate, and observed under a 20× stereomicroscope [34]. The number of SCN 3 on the root systems per unit area was counted.

2.2.9. Measurement of Physiological Indices

Wild-type (WT) soybean plants not inoculated with SCN were used as the negative control to exclude interference from inherent root traits or background physiological differences of plants on the resistance evaluation results. Meanwhile, WT soybean plants inoculated with SCN served as the positive control to verify the infection efficiency of SCN and the relative resistance level of transgenic overexpression (OX) hairy roots. All control groups and the treatment group (SCN-inoculated OX hairy roots) were grown in a sterile sand substrate under strictly consistent culture conditions: temperature of 25–28 °C, photoperiod of 16 h light/8 h dark, and relative humidity of 70%. Three biological replicates were set up, with 10 plants per replicate. For inoculation, 1800 second-stage juveniles (J2) of SCN were quantitatively added around the root system of each plant following standard protocols, while an equal volume of sterile water was added to the non-inoculated control group. After root samples were collected from all groups, they were immediately rinsed thoroughly with sterile water to remove adhering sand particles and impurities, followed by the selection of lateral roots with consistent growth status. In this study, root systems of SCN 3-stressed OX plants (14 d) and wild-type (WT) plants were rinsed with ddH2O water. Lateral roots of equal mass were then used to determine peroxidase (POD) activity, superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity, malondialdehyde (MDA) content, relative water content (RWC), electrical conductivity (EC), and proline synthetase (Pro) activity [34]. Specific determination methods were conducted in accordance with the kit manual instructions.

2.2.10. Establishment of Nicotiana benthamiana Culture System and Transient Transformation via Agrobacterium Infiltration

MS (Murashige and Skoog) solid medium was employed as the solid culture medium in the experiment (Supplementary Table S4). Tobacco seeds were transferred into 1.5 mL EP tubes, and a mixed solution of 100 μL NaClO and 900 μL sterile water was added to each tube. The seeds were vortexed for 10 min using a vortex oscillator, followed by a 5 min standing period at 25 °C to enhance disinfection efficiency [35]. Within a laminar flow hood, the seeds were rinsed three times with 500 μL of sterile water for the removal of residual disinfectant. Subsequently, the seeds were inoculated onto the surface of MS solid medium using a sterile pipette tip and cultured under optimal conditions for a duration of 10 d. Tobacco seedlings cultured for 10 d were transplanted into black pots filled with vermiculite and nutrient soil in equal volume proportions, and subjected to an additional 28 d of cultivation. When the plants reached a favorable growth state, they were initially subjected to a 24 h dark treatment [36]. Post dark treatment, the plants were transferred to a normal light environment for 1 h of pre-treatment before the infiltration process. Agrobacterium harboring the pCAMBIA1302-GmRF2-like recombinant plasmid was adjusted to an OD600 value of 0.8 using Nicotiana benthamiana resuspension solution, incubated at a constant temperature for 6 h, and then infiltration was performed by delivering the solution into the abaxial surface of Nicotiana benthamiana leaves via a sterile syringe. Agroinfiltrated Nicotiana benthamiana plants were incubated in darkness for 12 h, followed by 24 h under light. Leaf fluorescence was observed and imaged via a Leica (Leica, Germany) laser scanning confocal microscope.

3. Result

3.1. Genotypic Analysis of the Soybean Germplasm Resource Population

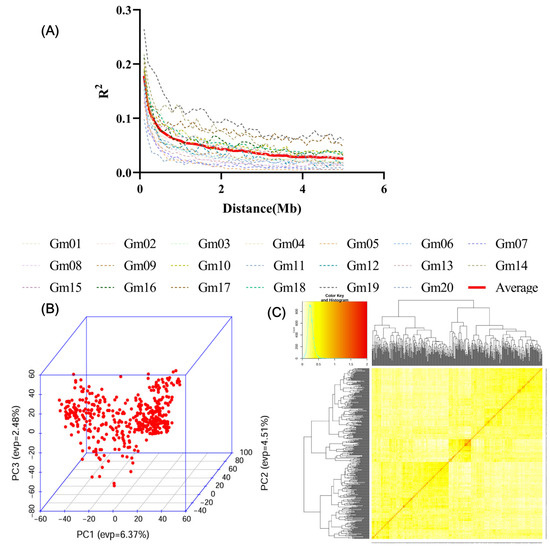

In this research, 632,540 single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) markers derived from 306 domestic and international soybean germplasm resources served as the genetic data foundation for conducting linkage disequilibrium (LD) analysis, population structure analysis, and genetic relationship analysis on the studied population. Analytical findings showed that population structure analysis could divide the tested natural population into 3 subpopulations (Supplementary Figure S1). For genome-wide linkage disequilibrium (LD) decay analysis, when the linkage disequilibrium coefficient R2 reached 0.1, the average LD decay distance across the whole genome was 332.9 kb (Figure 2A). In Principal Component Analysis (PCA), no obvious population stratification was detected in this population, and the genetic relatedness level among all tested accessions was low (Figure 2B). For further verification, heatmap analysis was applied to the genetic relationship matrix, which confirmed that the genetic relatedness between accessions in this study population was low (Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

Soybean Germplasm Population Genotype Analysis. (A): Genome-wide LD pattern; the dashed line denotes the LD decay curve of 20 chromosomes, and the solid red line represents the average decay curve of 20 chromosomes. (B): Principal Component Analysis (PCA). (C): Kinship analysis among individuals in the natural population. High-throughput omics data (gene expression abundance) clustering heatmap: The color bar at the top left corner indicates the correlation between values and colors (yellow/orange represents higher values). The dendrograms at the top and left sides show the clustering results, where samples and features are grouped based on the similarity in their expression/value patterns, respectively. The color of each cell in the middle matrix corresponds to the specific value of a particular gene in a given sample. Most areas in the figure are yellow, indicating that the expression levels of these features (genes) are generally high in the corresponding samples.

3.2. Classification and Evaluation of SCN Resistance and Screening of SCN-Resistant Germplasm Resources

The results revealed that the number of soil cysts at the sampling locations ranged from 43 to 53 per 100 g of air-dried soil (Supplementary Table S5), with the average number of SCN 3 eggs per 100 g of air-dried soil being 47. These findings indicated that the measured values of soil cyst numbers at each sampling site had a small variation range, and the unit density of nematodes in the soil of this disease nursery met the identification standards, making it suitable for disease resistance identification of soybean resources.

Female Index (FI) of tested accessions ranged from 0–1.5, with an average of 27.91, standard deviation of 29.20, and coefficient of variation of 1.07, indicating significant genetic differences. A total of 206 disease-resistant (67.3%) and 100 disease-susceptible (30.6%) accessions were identified, including 33 very resistant (VR) ones (10.78%, e.g., kx3, kx5, zp03-5373, Table 1) and 85 resistant accessions with FI 10–20 (27.77%, Supplementary Table S6). The selected elite germplasm resources can be cultivated and further tested in Northeast China and the Huang-Huai-Hai region, where SCN 3 is predominant. Through the determination of yield and quality, these resources will make significant contributions to mitigating soybean yield losses caused by SCN disease.

Table 1.

Information on highly resistant materials.

Geographical distribution analysis indicated that among 180 Heilongjiang accessions (58.82% of total), 74.44% were disease-resistant (17 VR, 117 moderately resistant (MR)). Disease-resistant accessions were also distributed in Jilin (8 VR, 15 MR among 33 accessions), Liaoning (66.11% resistant among 18 accessions), Beijing (1 VR, 14 MR among 19 accessions), and Inner Mongolia (4 VR, 13 MR among 20 accessions). Notably, resistant accessions from Northeast China accounted for 81.55% of the total resistant ones (Supplementary Table S6). The identified VR accessions provide important resistant germplasm resources for studies on soybean SCN resistance genetic mechanism and SCN-resistant soybean breeding.

3.3. Genome-Wide Association Study of SCN Phenotypes

The frequency distribution of the Female Index (FI) among 306 domestic and international soybean germplasm resources was computed using Microsoft Excel 2010. Histogram results displayed a nearly normal distribution (Supplementary Figure S3), indicating that the natural soybean population harbors rich genetic variation and is suitable for genome-wide association study (GWAS).

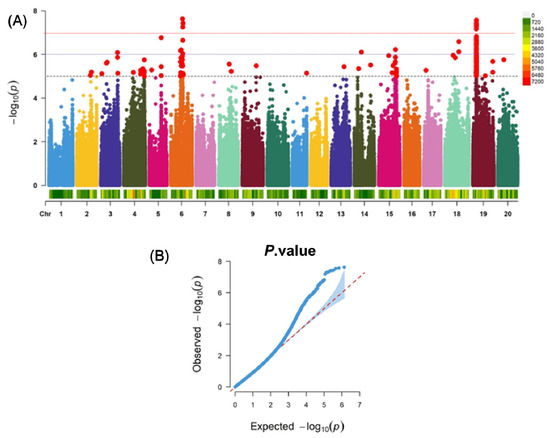

GWAS was implemented using the compressed Mixed Linear Model (cMLM), which identified quantitative trait locus (QTL) loci showing significant associations between phenotype and genotype. Further analysis of these QTL loci revealed 77 significant loci with −log10(P) ≥ 5.5 (Figure 3A,B and Supplementary Table S7), distributed across Chromosomes 3, 5, 6, 8, 14, 15, 18, and 19. A total of 93 candidate genes were screened from these loci (Supplementary Table S8). Among the candidate genes, Glyma.19G051500 (RING domain-containing ubiquitin ligase), Glyma.04G222200 (bZIP transcription factor), Glyma.15G222500 (RmlC-like cupins superfamily protein), and Glyma.03G189800 (leucine-rich repeat protein kinase) are all involved in plant stress responses or signal transduction. Glyma.18G093300 and Glyma.18G093400 harbor the NB-ARC domain, a key disease resistance domain that regulates plant immunity and stress responses. Glyma.18G093100 and Glyma.03G190300 are pentatricopeptide repeat (PPR) proteins, which are implicated in plant growth and development as well as abiotic stress responses. Additionally, the GDSL lipase family, exocin family proteins, RNA-binding proteins, α/β hydrolase superfamily proteins, P-loop nucleoside triphosphate hydrolase superfamily proteins, uridine kinase family, and MADS-box transcription factors have also been identified as potential candidate genes potentially involved in SCN resistance.

Figure 3.

Manhattan plots for the GWAS for FI. The line indicates the significance threshold (−log10(P) = 5.5) and QQ Plot. (A): Manhattan plot of the genome-wide association study (GWAS) under the compressed mixed linear model (CMLM), where the black line represents −log10(p) = 5.5, the purple line represents −log10(p) = 6, and the red line represents −log10(p) = 7; Among them, dots of different colors represent SNPs on the 20 chromosomes, and the red dots above the threshold line are significant SNP loci. (B): Quantile-quantile plot (Q-Q plot) of the genome-wide association study (GWAS). Observed blue curve: The distribution trend of −log10(p) values for SNP loci obtained from the actual analysis.Expected red dashed line: The theoretical distribution trend dominated by random errors (if all SNPs have no true associations, the blue curve should perfectly overlap with the red dashed line). Light blue area: Typically the confidence interval of the random distribution (e.g., 95% confidence interval)—If the observed values fall within this area, they are most likely random errors; if they fall outside this area, they are more likely to be true association signals.

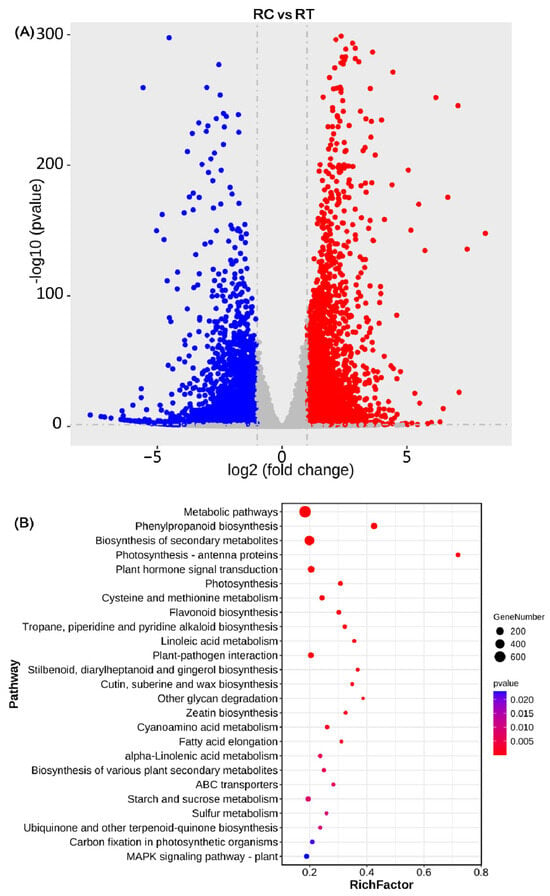

3.4. Results and Analysis of RNA-Seq

This study aimed to analyze the expression changes of genes involved in synthesis and regulation in soybean varieties exhibiting extreme SCN resistance or susceptibility. RNA-Seq analysis was performed using the Illumina HiSeqTM 2500 platform following SCN infection. Twelve sequencing samples underwent data quality control; after filtering, the Q30 ratio ranged from 94.38% to 95.32%, and the GC content ranged from 41.75% to 44.15% (Supplementary Table S9). These results indicated that the base calling accuracy was high, and the data could be used for screening differentially expressed genes (DEGs).

HISAT2.0 was employed to align the generated sequencing data to the soybean reference genome (Glycine max Wm82.a2.v1). The results showed that the Mapped rate among the 12 sequencing samples ranged from 82.48% to 92.33% (Supplementary Table S10), indicating a high gene coverage rate. Differentially expressed genes were visualized using a volcano plot (Figure 4A). With |log2(Fold change)| > 1 and p < 0.05 as thresholds for fold change screening, a total of 4185 up-regulated genes and 3195 down-regulated genes were identified. KEGG analysis was performed on the differentially expressed genes (Figure 4B). The results showed that 1127 differentially expressed genes were enriched in KEGG pathways, and these DEGs were distributed across multiple metabolic pathways. Among them, significant enrichment was observed in the Phenylpropanoid biosynthesis pathway, Biosynthesis of secondary metabolites pathway, and other pathways. In addition, a large number of differentially expressed genes were also significantly enriched in the Plant hormone signal transduction pathway, Flavonoid biosynthesis pathway, and MAPK signaling pathway–plant. The results indicated that after being subjected to SCN stress, resistance genes in SCN-resistant soybean are involved in multiple biological metabolic pathways. Among these, phenylpropanoid metabolism is a key pathway for plants to synthesize disease resistance-related substances such as lignin, flavonoids, and phytoalexins. Lignin reinforces plant cell walls, forming a physical barrier to hinder nematode invasion; flavonoids can interfere with nematode chemotaxis or development; phytoalexins are specific antimicrobial substances produced by plants in response to pathogen attack. The enrichment of these metabolites indicates that plants enhance secondary metabolism to defend against SCN. Plant hormones (e.g., jasmonic acid, salicylic acid) are core signaling molecules regulating disease resistance responses. The enrichment of this pathway suggests that plants coordinate defense reactions through a hormonal signaling network. For instance, jasmonic acid induces the production of insect resistance-related protease inhibitors in plants, while salicylic acid activates systemic acquired resistance, thereby enhancing resistance to SCN. The Plant-pathogen interaction pathway involves key mechanisms of plant pathogen recognition and immune response activation, such as the activation of resistance proteins and the initiation of hypersensitive responses. Its enrichment indicates that plants activate classical disease resistance signaling pathways to trigger a series of defense responses against SCN invasion. The KEGG enrichment results, encompassing phenylpropanoid metabolism, pathogen recognition and immune activation, and plant hormone regulation, collectively constitute the plant defense system against SCN infection.

Figure 4.

Analysis of gene expression levels and KEGG Enrichment (A): Volcano plot of differentially expressed genes between RC and RT (SCN-resistant DN L10 vs. SCN-susceptible HN37); Red: upregulated differentially expressed genes (DEGs); Blue: downregulated differentially expressed genes (DEGs); Dashed lines represent the selection criteria: log2FC > 1 and false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05. (B): KEGG enrichment analysis of 25 pathways for differentially expressed genes.

3.5. Identification of the GmRF2-like Gene

The GmRF2-like gene was jointly identified via genome-wide association study (GWAS) results and transcriptome data of soybean with extreme resistance/susceptibility under SCN stress. This gene was up-regulated in the transcriptome, and the QTL loci mapped by GWAS had a −log10(P) value ≥ 5.5, so it was selected as a potential candidate gene for further in-depth study.

3.6. qRT-PCR Analysis

To further confirm whether GmRF2-like is up-regulated in soybean germplasm with extreme resistance or susceptibility to SCN, four accessions were selected as the SCN 3 treatment group: extreme SCN 3-resistant accessions (DN L10, RILF1016) and extreme SCN 3-susceptible accessions (DN50, RILF1016). Meanwhile, four resistant and susceptible soybean accessions without SCN 3 stress served as the control group (Supplementary Figure S4). The results showed that the GmRF2-like gene was expressed in soybean roots to varying degrees. The average expression levels of DN50 and SN14 (SN14 was not mentioned in the original material list; it is recommended to verify the accession name) without stress treatment were approximately 0.609 and 0.781, respectively, while their relative expression levels after SCN stress were 1.397 and 2.496. For RILF1016 and DN L10, the average expression levels without SCN stress were 4.576 and 3.621, respectively, and their relative expression levels under SCN stress were 9.824 and 8.520. Compared with the roots of resistant soybean without stress, the GmRF2-like gene was significantly up-regulated in the roots of resistant soybean under SCN 3 stress. Furthermore, the relative expression level of the gene in disease-resistant germplasm was more significantly up-regulated than that in disease-susceptible germplasm under SCN 3 stress. These results suggested that the GmRF2-like gene may respond to SCN 3 stress and may be involved in the response process of SCN disease.

3.7. Gene Cloning and Vector Homologous Recombination

Results showed that the RNA had good concentration, purity, and integrity, with clear electrophoretic bands free of smearing, indicating high integrity (Supplementary Figure S5A). RNA was reverse-transcribed with ReverTra Ace® qPCR RT Master Mix, and the resulting cDNA was used for subsequent gene cloning. Plasmids pYLCRISPR/Cas9, pCAMBIA3300, and pCAMBIA1302 were linearized by single enzyme digestion; the linearized vectors showed a distinct electrophoretic distance from the original plasmids, confirming complete digestion (Supplementary Figure S5B). For target gene cloning, a clear band was observed at 891 bp (Supplementary Figure S5C). Ligation was performed using the ClonExpress II One Step Cloning Kit, and the ligation product was transformed into DH5α competent cells. Specific PCR amplification (Supplementary Figure S5D) and sequencing analysis confirmed the successful transformation of the recombinant plasmid into DH5α. In gene editing vector construction, the first-round PCR showed clear bands: 3d DNA at 250–500 bp and 3b DNA at 140 bp (Supplementary Figure S5E,F). The second-round PCR exhibited a clear band at approximately 500 bp (Supplementary Figure S5G). The second-round PCR products (3d/3b) were homologously recombined with pYLCRISPR/Cas9 and successfully transformed into DH5α, with a clear target band at 1000 bp in gel electrophoresis (Supplementary Figure S5H). Finally, pCAMBIA3300-GmRF2-like and pYLCRISPR/Cas9-GmRF2-like were transformed into Agrobacterium strain K599.

3.8. Agrobacterium-Mediated Transformation and Soybean Cyst Nematode (SCN) Disease Identification and Analysis

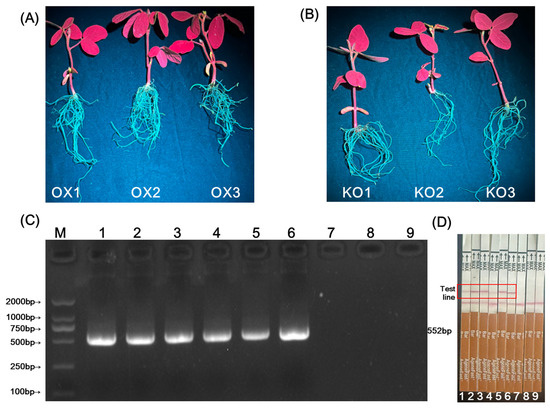

Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain K599 harboring gene-editing and overexpression recombinant vectors was genetically transformed into the roots of soybean at the second trifoliolate leaf stage (R2 stage). The roots of OX1-OX3 (overexpression lines) and KO1-KO3 (gene-editing lines) were irradiated with 440 nm excitation light using a handheld portable LUYOR-3415RG dual-wavelength fluorescent protein excitation light source LUYOR Instrument Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China; Cat. LUYOR-3415RG). The results showed that green fluorescence was observed in the plant roots (Figure 5A). At the protein level, transformed hairy roots were detected using BAR test strips. The results showed that positive signals were observed in the test lines of the BAR test strips for the roots of OX1-OX3 and KO1-KO3, while negative signals were observed in the test lines of the BAR test strips for wild-type (WT) roots (Figure 5D). At the DNA level, detection using specific primers (BAR-F/R) showed that clear electrophoretic bands appeared at 552 bp for the roots of OX1-OX3 and KO1-KO3 (Figure 5B). Sequencing results confirmed that these bands matched the exogenous BAR (bialaphos resistance gene). No electrophoretic bands were observed in WT roots (Figure 5B). In conclusion, soybean hairy roots with overexpression (OX) and gene editing (KO) were successfully obtained.

Figure 5.

Detection of transgenic roots. (A): OX1-OX3 roots with overexpressed GmRF2-like (recipient DN50); (B): KO1-KO3 roots with GmRF2-like edited by CRISPR-Cas9 (recipient DN50); (C): M: DL2000 Marker; 1–3: PCR electrophoresis results of BAR gene in OX1-3 roots; 4–6: PCR electrophoresis results of BAR gene in KO1-3 roots; 7-9: PCR electrophoresis results of BAR gene in WT1-3 roots; (D): 1–3: Test strip detection results of BAR gene in overexpressed roots; 4–6: Test strip detection results of BAR gene in gene-edited roots; 7–9: Test strip detection results of BAR gene in WT roots. The red box indicates the test line for Bar gene detection, which appears as a Bar-transgenic positive signal in the image.

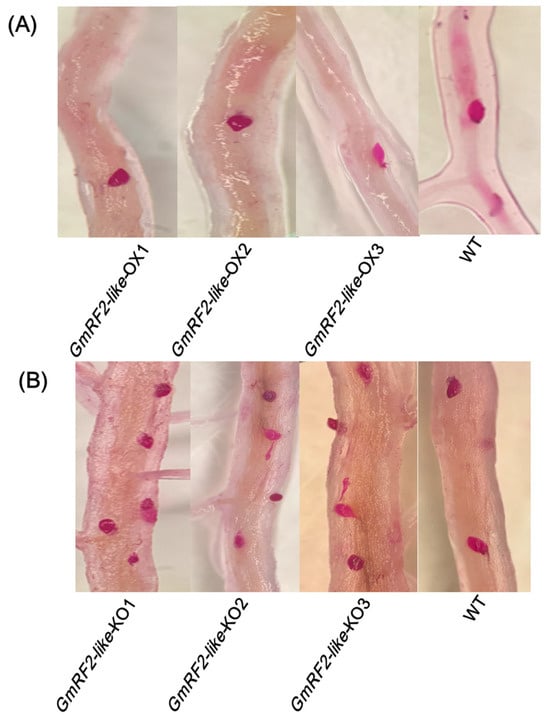

Soybean hairy roots of OX1-OX3 (overexpression lines), KO1-KO3 (gene-editing lines), and WT1-WT3 (wild-type lines) were transplanted into SCN 3-infested soil. After 14 d, acid fuchsin staining revealed an average of 2.95, 8.30, and 5.04 nematodes per unit area in the OX, KO, and WT lines, respectively. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 29.0 software. The results revealed that the number of SCN in the hairy roots of the OX group exhibited an extremely significant difference compared with the WT group (p < 0.01), and the KO group also showed an extremely significant difference compared with the WT group (p < 0.01). These results demonstrated that the OX-GmRF2-like gene has a function in inhibiting SCN 3 (Figure 6A,B and Supplementary Figure S2A,B).

Figure 6.

Results of SCN Disease Phenotypic Identification. (A): GmRF2-like-OX1-3: Phenotypic identification of SCN in GmRF2-like-overexpressing roots; (B): Phenotypic identification of SCN in WT roots. The red spots in the roots represent female nematodes stained with acid fuchsin solution per unit area.

Using SPSS 29.0 software, T-test for difference analysis was conducted on the number of SCN 3 per unit area in the roots of GmRF2-like gene OE/KO/WT treated with SCN 3. The results showed that among the three groups of data, the average numbers of SCN 3 in WT, KO and WT were 8.31, 2.95 and 5.04, respectively; the two-tailed mean p-values of WT-OX and WT-KO were 5.8497 × 10−11 and 3.8391 × 10−12, respectively. Extremely significant differences were observed in the mean number of SCN 3 per unit area between OX and WT, as well as between KO and WT. GmRF2-like may play a positive regulatory role and be involved in regulating soybean resistance to SCN (Table 2).

Table 2.

Paired samples T-test results.

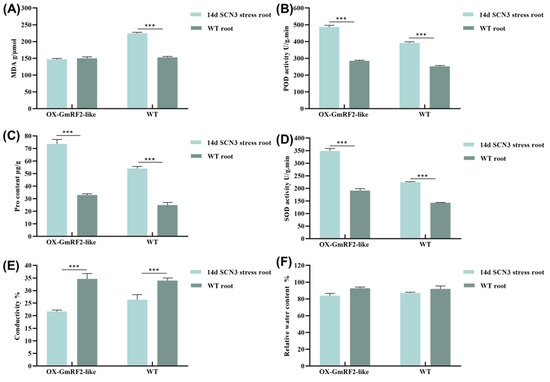

3.9. Root Physiological and Biochemical Indicator Identification

The results of the physiological responses of roots in OX-GmRF2-like and wild-type (WT) plants under SCN 3 stress for 14 d were as follows: Under stress, the malondialdehyde (MDA) content in OX-GmRF2-like was significantly lower than that in WT, indicating less severe membrane damage in OX-GmRF2-like roots. Regarding peroxidase (POD) activity, that in OX-GmRF2-like roots was significantly higher than that in WT roots, which suggested a stronger reactive oxygen species (ROS)-scavenging capacity in OX-GmRF2-like. For proline (Pro) content, the level in OX-GmRF2-like was significantly higher than that in WT, implying better osmotic adjustment ability and stress tolerance in OX-GmRF2-like. In terms of superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity, that in OX-GmRF2-like roots was significantly higher than that in WT roots, indicating a further enhanced ROS-scavenging capacity in OX-GmRF2-like. The electrical conductivity of OX-GmRF2-like roots was significantly lower than that of WT roots, demonstrating better cell membrane integrity and less stress-induced damage in OX-GmRF2-like roots. No significant difference was observed in relative water content between the two genotypes, suggesting comparable water retention capacity. It was confirmed by these results that under SCN 3 stress, OX-GmRF2-like roots exhibited stronger resistance than WT roots, which could significantly improve the stress tolerance of plants (Figure 7A–F).

Figure 7.

Determination of SCN 3 stress-related indices in transgenic root systems. (A) Determine the MDA content of OX-GmRF2-like and WT (DN50); (B) Determine the POD content of OX-GmRF2-like and WT (DN50); (C) Determine the Pro content of OX-GmRF2-like and WT (DN50); (D) Determine the SOD content of OX-GmRF2-like and WT (DN50); (E) Determine the relative electrical conductivity of OX-GmRF2-like and WT (DN50); (F) Determine the relative water content of OX-GmRF2-like and WT (DN50); p < 0.001: Extremely significant (Marked with three asterisks, ***).

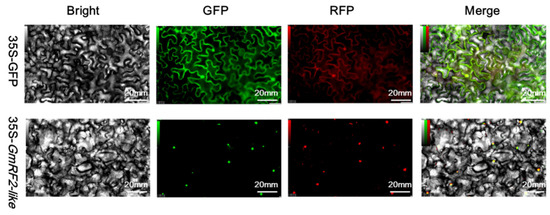

3.10. Nuclear Localization of Soybean GmRF2-like Protein in Nicotiana benthamiana

Results from laser scanning confocal microscopy showed that in tobacco leaves infiltrated with pCAMBIA1302-GFP (empty vector control), green fluorescence was observed in the nucleus, cytoplasm, and cell membrane—confirming that GFP (the reporter protein) was expressed in these three locations. In contrast, for tobacco leaves infiltrated with pCAMBIA1302-GmRF2-like, the brightest fluorescence was detected in the nucleus. These results indicated that the protein encoded by GmRF2-like is mainly expressed in the nucleus and is a nuclear-localized protein (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Subcellular Localization Analysis of GmRF2-like-Encoded Protein. Bright: Bright field; GFP: Green fluorescent protein field; RFP: Red fluorescent protein field (nuclear localization Marer); Merge: Merged field; 35S-GFP: Results of tobacco infiltration with Agrobacterium tumefaciens GV3101 (p-soup19) harboring pCAMBIA1302-GFP; 35S-GmRF2-like: Results of tobacco infiltration with Agrobacterium tumefaciens GV3101 (p-soup19) transformed with pCAMBIA1302-GmRF2-like.

4. Discussion

SCN disease severely endangers soybean yield and quality; it is a highly widespread soil-borne disease. Current research on SCN resistance genes has mainly focused on genes near the two loci rgh1 and rgh4. Even so, these loci can only account for approximately 60% of the genetic variation [37]. However, long-term reliance on these two major resistance loci will lead to the gradual loss of SCN resistance in soybean. Therefore, mining new SCN resistance genes has become increasingly important.

GmRF2-like gene is classified as a member of the Basic leucine zipper (bZIP) family. This subfamily is composed of plant bZIP transcription factors that share similarity with RF2a and RF2b from Oryza sativa (rice). An important role is played by these transcription factors in plant development. Interaction between them can be achieved through homodimerization (dimer formation by the same protein itself) or heterodimerization (dimer formation between different members of this subfamily), and transcriptional activation can be induced by them at the promoter of Rice Tungro Bacilliform Virus (RTBV). The regulation of this promoter is dependent on sequence-specific DNA-binding proteins that are capable of binding to the key cis-acting element Box II [37]. Differences exist between RF2a and RF2b in the following aspects: binding affinity for the Box II element, expression patterns in different organs of rice, and subcellular localization. Significantly enhanced resistance to Rice Tungro Disease (RTD) has been observed in transgenic rice with increased expression levels of RF2a and RF2b. In the process of regulating various cellular processes, the functional role of bZIP factors is exerted through a regulatory network formed by homodimers and heterodimers. Meanwhile, an important role is also played by bZIP factors in the response to stimulatory or stress signals, such as cytokines, genotoxic substances, or physiological stresses [38]. The subcellular localization analysis of the protein encoded by GmRF2-like revealed a nuclear localization pattern, which indirectly confirms the transcriptional regulatory function of this protein. It is speculated that GmRF2-like may exert its defensive function against SCN through the pathway of “intranuclear transcriptional regulation—defense pathway activation-nematode infection inhibition”. When SCN penetrates root cells, signal transduction pathways are activated to promote the nuclear translocation of GmRF2-like protein. This protein can then bind to the promoters of pathogenesis-related (PR) genes, NBS-LRR resistance genes, or cell wall synthesis genes (e.g., cellulose synthase genes), thereby inhibiting SCN growth and reinforcing the formation of nematode feeding sites.

To date, no direct reports have been documented regarding Soybean Cyst Nematode (SCN) disease. However, relevant reports have been published on bZIP transcription factors in response to stresses such as Sclerotinia sclerotiorum, plant hormones, salt, drought, and heavy metals. Tan et al. revealed that the Brassica napus bZIP44 transcription factor specifically binds to the CGTCA motif in the promoter of BnaC07.GLIP1 to positively regulate its expression. BnbZIP44 can respond to Sclerotinia sclerotiorum infection; its heterologous expression in Arabidopsis thaliana inhibited the accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and enhanced the resistance of Arabidopsis to Sclerotinia stem rot [39]. Gao et al. found that under drought stress, OsbZIP86 can promote the transcription of OsNCED3—a key rate-limiting enzyme gene for abscisic acid (ABA) synthesis—thereby enhancing rice drought tolerance by regulating ABA biosynthesis in rice [40]. Li et al. pointed out the regulatory role of the TGA subfamily within bZIP transcription factors in salicylic acid (SA)-mediated disease resistance signal transduction, and that the expression of other bZIP transcription factor genes is also affected by SA hormone signals [41]. AtbZIP17 is a membrane-bound bZIP transcription factor in Arabidopsis thaliana that is activated in response to salt stress. When the constitutively active form of AtbZIP17 was introduced into transgenic plants, the induced expression of activated AtbZIP17 enhanced the salt tolerance of Arabidopsis under salt stress conditions [42]. In summary, bZIP transcription factors are widely involved in plant responses to biotic and abiotic stress processes, and it has become increasingly important to further explore the relationship between bZIP transcription factors and SCN disease. Compared with the disease-resistant bZIP genes reported in other crops, GmRF2-like exhibits specific regulation on SCN disease in soybean, providing a novel genetic resource and regulatory model for deciphering the molecular mechanisms underlying resistance to host-specific parasitic nematodes.

Several limitations exist in the research on the GmRF2-like gene associated with SCN resistance: Resistance identification relies on controlled greenhouse conditions, and discrepancies from complex field ecological environments (e.g., SCN population heterogeneity, abiotic stresses) may lead to phenotypic deviations, necessitating further validation through multi-year and multi-environment field trials. Additionally, the selected SCN physiological races are dominant in Northeast China, which cannot ensure the universality of gene function and the broad-spectrum nature of resistance. In the future, it will be necessary to expand soybean variety resources and include more physiological races for combined evaluation.

In this study, the compressed Mixed Linear Model (cMLM) in genome-wide association study (GWAS) was used to perform association analysis on 306 soybean germplasm resources from domestic and international sources. Combined with transcriptome data of soybean materials with extreme resistance or susceptibility to SCN, the potential candidate gene GmRF2-like was jointly identified. qRT-PCR analysis, construction of overexpression vectors and gene editing vectors, acquisition of transgenic hairy roots, and resistance identification to SCN 3 were conducted to determine the regulatory function of the target gene. It provides important genetic resources for soybean resistance to SCN disease. In future studies, the SCN-resistant function of GmRF2-like can be further validated through field trials. Under natural soil conditions and different SCN population pressures, systematic evaluations should be conducted on soybean materials with overexpression or knockout of this gene, focusing on disease resistance, agronomic trait stability, and environmental adaptability. Additionally, elite alleles of GmRF2-like can be efficiently integrated into superior soybean cultivars via gene editing, marker-assisted selection (MAS), and other molecular breeding technologies to develop new varieties with both high SCN resistance and excellent agronomic traits. This research will provide novel genetic resources for soybean breeding against SCN.

5. Conclusions

In this study, a combined GWAS and RNA-Seq approach identified GmRF2-like, a basic leucine zipper (bZIP) transcription factor gene, as a candidate for soybean resistance to SCN 3. qRT-PCR validation confirmed that GmRF2-like is more strongly induced by SCN 3 in resistant germplasms. Transgenic hairy root assays demonstrated that overexpression (OX) of GmRF2-like significantly reduced nematode numbers, while gene editing (KO) increased susceptibility, establishing its positive regulatory role in SCN 3 resistance. Mechanistically, GmRF2-like enhances resistance by improving reactive oxygen species (ROS) scavenging capacity (elevated POD and SOD activities), osmotic adjustment (increased proline content), and cell membrane integrity (reduced MDA levels and relative electrical conductivity). Subcellular localization analysis showed nuclear targeting, consistent with its function as a transcription factor. Collectively, the results show that GmRF2-like is a key gene mediating soybean resistance to SCN 3, providing a valuable resource for molecular breeding. Future studies will focus on deciphering its downstream target gene network.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/agronomy15122752/s1, Supplementary Table S1: Source of material for testing; Supplementary Table S2: Primers sequence information; Supplementary Table S3: 30× fuchsine solution stock solution; Supplementary Table S4: MS medium formulations; Supplementary Table S5: Number of soil cysts in the nursery; Supplementary Table S6: Information on medium resistance material; Supplementary Table S7: SNPs that significantly associated with SCN resistance of soybean; Supplementary Table S8: Candidate gene information; Supplementary Table S9: Statistics Table of Sample Sequencing Data; Supplementary Table S10: Statistics of sequencing date aligned with reference genome sequence; Supplementary Table S11: Design of PCR-related procedures, restriction enzyme digestion and ligation procedures; Supplementary Table S12: Composition of restriction enzyme digestion, linearization and ligation-cloning systems; Supplementary Figure S1: Population structure analysis diagram; Supplementary Figure S2: Results of SCN Disease Phenotypic Identification; Supplementary Figure S3: Distribution of female index of 306 soybean materials; Supplementary Figure S4: Analysis of relative expression levels of soybean roots under SCN3 stress; Supplementary Figure S5: 2% Agarose gel electrophoresis.

Author Contributions

Y.H.: Writing—review and editing, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Data curation, Conceptualization. W.T.: Investigation, Formal analysis. Y.L.: Investigation, Formal analysis. H.L.: Investigation, Formal analysis. X.Z.: Writing—review and editing, Conceptualization. S.Q.: Writing—original draft, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation. S.H.: Visualization, Formal analysis, Data curation. G.S.: Visualization, Formal analysis. M.Z.: Methodology, Formal analysis. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was conducted in the Key Laboratory of Soybean Biology of the Chinese Education Ministry, Soybean Research & Development Center (CARS) and the Key Laboratory of Northeastern Soybean Biology and Breeding/Genetics of the Chinese Agriculture Ministry, and was financially supported by The Chinese National Natural Science Foundation (32472196, U22A20473), The Biological Breeding-National Science and Technology Major Projects (2023ZD04070), The Inner Mongolia Science and Technology project (2023DXZD0002), Heilongjiang Provincial ‘Outstanding Young Teachers’ Basic Research Support Program (YQJH2023187), The National Key Research and Development Project of China (2021YFD1201103), The Youth Leading Talent Project, The Ministry of Science and Technology in China (2015RA228), The national project (CARS-04-PS07), and Young leading talents of Northeast Agricultural University (NEAU2023QNLJ-003).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to the Closed Breeding Center in Anda Area, Daqing City, China for providing the diseased soil infected with soybean cyst nematode (SCN).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Qu, S.; Hu, S.H.; Song, G.C.; Sun, H.W.; Liu, F.; Zhang, M.L.; Zhan, Y.H.; Li, Y.G.; Teng, W.L.; Li, H.Y.; et al. Genome-wide association study and molecular marker development for resistance to soybean cyst nematode in soybean. Plant Genome 2025, 18, e70083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, S.; Liu, F.; Song, G.C.; Hu, S.H.; Fang, Y.Y.; Zhao, X.; Han, Y.P. Cloning and Preliminary Functional Analysis of Zinc Finger Protein Gene GmC2H2-2like for Soybean Resistance to Cyst Nematode. Acta Agric. Boreali-Sin. 2024, 39, 195–207. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, Y.S.; Wang, Z. Research progress on resistance to soybean cyst nematode in China. Mol. Plant Breed. 2004, 5, 609–619. [Google Scholar]

- Lian, Y.; Wang, J.S.; Li, H.C.; Wei, H.; Li, J.Y.; Wu, Y.K.; Lei, C.F.; Zhang, H.; Wang, S.F.; Guo, J.Q.; et al. Race Distribution of Soybean Cyst Nematode in the Main Soybean Producing Area of Huang-Huai Valleys. Acta Agron. Sin. 2016, 42, 1479–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, J.; Li, J.R.; Zhen, S.J.; Dong, L.W.; Wang, J.L.; Hu, Y.F.; Shen, Z.B.; Wang, J.J. Investigation on Soybean Cyst Nematode Disease in Soybean Producing Areas of Heilongjiang Province from 2015 to 2022. Soybean Sci. 2024, 43, 176–184. [Google Scholar]

- Hewezi, T.; Howe, P.; Maier, T.R.; Hussey, R.S.; Mitchum, M.G.; Davis, E.L.; Baum, T.J. Cellulose binding protein from the parasitic nematode Heterodera schachtii interacts with Arabidopsis pectin methylesterase: Cooperative cell wall modification during parasitism. Plant Cell 2008, 20, 3080–3093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, S.S.; Ma, H.; Li, K.; Li, J.F.; Liu, H.L.; Quan, L.P.; Zhu, X.L.; Chen, M.L.; Lu, W.Y.; Chen, X.M.; et al. Comparisons of constitutive resistances to soybean cyst nematode between PI 88788- and Peking-type sources of resistance in soybean by transcriptomic and metabolomic profilings. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 1055867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, F.L.; Yu, J.Y.; Li, C.J.; Huang, M.H.; Zhao, L.; Wang, X.; Jiang, Y.; Qin, R.F.; Wang, C.L. Research progress on occurrence and management of soybean cyst nematode in Northeast China. J. Northeast Agric. Univ. 2022, 53, 87–94. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.L.; Fan, L.J.; Wu, C.Y.; Yao, J.; Kang, M.H.; Liu, Z.R.; Peng, D.L.; Yao, Y.J. Overview of the Main Mechanisms of Biocontrol Microorganisms Acting on Plant Pathogenic Nematodes. J. South. Agric. 2023, 54, 2969–2977. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell, B.E.; Brim, C.A.; Ross, J.P. Inheritance of resistance of soybeans to the cyst nematode, Heterodera Glycines. Agron. J. 1960, 52, 635–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matson, A.L.; Williams, L.F. Evidence of a fourt gene for resistance to the soybean cyst nematodde. Crop Sci. 1965, 5, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao-Arelli, A.P. Inheritance of resistance to Heterodera glycines Race 3 in soybean accessions. Plant Dis. 1994, 78, 898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Concibido, V.C.; Diers, B.W.; Arelli, P.R. A decade of QTL mapping for cyst nematode resistance in soybean. Crop Sci. 2004, 44, 1121–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niblack, T.L.; Colgrove, A.L.; Colgrove, K.; Bond, J.P. Shift in virulence of soybean cyst nematode is associated with use of resistance from PI88788. Plant Health Prog. 2008, 9, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Hudson, M.E. WI12Rhg1 interacts with DELLAs and mediates soybean cyst nematode resistance through hormone pathways. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2022, 20, 283–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, L.; Chang, H.X.; Brown, P.J.; Domier, L.L.; Hartman, G.L. Genome-wide association and genomic prediction identifies soybean cyst nematode resistance in common bean including a syntenic region to soybean Rhg1 locus. Hortic Res. 2019, 6, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayless, A.M.; Smith, J.M.; Song, J.; McMinn, P.H.; Teillet, A.; August, B.K.; Bent, A.F. Disease resistance through impairment of α-SNAP-NSF interaction and vesicular trafficking by soybean Rhg1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 7375–7382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Kandoth, P.K.; Warren, S.D.; Yeckel, G.; Heinz, R.; Alden, J.; Yang, C.; Jamai, A.; El-Mellouki, T.; Juvale, P.S.; et al. A soybean cyst nematode resistance gene points to a new mechanism of plant resistance to pathogens. Nature 2012, 492, 256–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijhawan, A.; Jain, M.; Tyagi, A.K.; Khurana, J.P. Genomic Survey and Gene Expression Analysis of the Basic Leucine Zipper Transcription Factor Family in Rice. Plant Physiol. 2008, 146, 333–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.T.; Wu, G.Q.; Wei, M. Roles of bZIP Transcription Factor in the Response to Stresses and Growth and Development in Plants. Biotechnol. Bull. 2024, 40, 148–160. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Yao, T.; Lin, W.; Hinckley, W.E.; Galli, M.; Muchero, W.; Gallavotti, A.; Chen, J.G.; Huang, S.S.C. Double DAP-seq uncovered synergistic DNA binding of interacting bZIP transcription factors. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 2600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Yuan, S.J.; Li, R.F.; Du, C.H.; Zhan, H.X.; Zhang, S.S.; Ma, J.Z.; Yang, Y. Research Progress on Biological Functions of Plant bZIP Transcription Factors. J. Shanxi Univ. Chin. Med. 2023, 24, 221–225. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, J.Z.; Yan, Z.L.; Qi, H.Z.; Chen, H.Y.; Zhang, H.F.; Yang, C.P.; Wang, N. Soybean Regulatory Genes in Drought-Resistant Genetic Engineering: New Application Progress. Soybean Sci. 2025, 44, 135–146. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.S.; Zhang, X.X.; Zhang, X.M.; Bi, Y.M.; Gao, W.W. A bZIP transcription factor, PqbZIP1, is involved in the plant defense response of American ginseng. PeerJ 2022, 10, e12939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dröge-Laser, W.; Snoek, B.L.; Snel, B.; Weiste, C. The Arabidopsis bZIP transcription factor family-an update. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2018, 45, 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chacón-Cerdas, R.; Barboza-Barquero, L.; Albertazzi, F.J.; Rivera-Méndez, W. Transcription factors controlling biotic stress response in potato plants. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2020, 112, 101527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Liu, Y.H.; Li, Z.X.; She, Z.Y.; Chai, M.G.; Aslam, M.; He, Q.; Huang, Y.M.; Chen, F.Q.; Chen, H.H.; et al. The bZIP transcription factor GmbZIP15 facilitates resistance against Sclerotinia sclerotiorum and Phytophthora sojae infection in soybean. iScience 2021, 24, 102642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, C.W.; Baek, W.; Lim, S.; Han, S.; Lee, S.C. Expression and functional roles of the pepper pathogen-induced bZIP transcription factor CabZIP2 in enhanced disease resistance to bacterial pathogen infection. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2015, 28, 825–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.L.; Fan, S.H.; Hu, W.; Liu, G.Y.; Wei, Y.X.; He, C.Z.; Shi, H.T. Two cassava basic leucine zipper (bZIP) transcription factors (MebZIP3 and MebZIP5) confer disease resistance against cassava bacterial blight. Front Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Mitchum, M.G. A major role of class III HD-ZIPs in promoting sugar beet cyst nematode parasitism in Arabidopsis. PLoS Pathog. 2024, 20, e1012610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riggs, R.D.; Schmitt, D.P. Complete characterization of the race scheme for Heterodera glycines. J. Nematol. 1988, 20, 392–395. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.M.; Liu, Y.; Tao, Y.; Xu, C.J.; Li, X.; Zhang, X.M.; Han, Y.P.; Yang, X.; Sun, J.Z.; Li, W.B. Identification of genetic loci and candidate genes related to soybean flowering through genome wide association study. BMC Genom. 2019, 20, 987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahraeian, S.M.E.; Mohiyuddin, M.; Sebra, R.; Tilgner, H.; Afshar, P.T.; Au, K.F.; Bani Asadi, N.; Gerstein, M.B.; Wong, W.H.; Snyder, M.P.; et al. Gaining comprehensive biological insight into the transcriptome by performing a broad-spectrum RNA-seq analysis. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, S.; Zhang, M.; Song, G.; Hu, S.; Teng, W.; Li, Y.; Zhao, X.; Guan, R.; Li, H. Characterization of GmABI3VP1 associated with resistance to soybean cyst nematode in Glycine max. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Van Delden, S.H.; Nazari del Jou, M.J.; Marcelis, L.F.M. Research on nutrient solution composition for Arabidopsis thaliana hydroponics: Nutrient solutions for Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Methods 2020, 16, 72. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.; Chen, L.; Wang, Y. Optimization of tobacco seedling transplanting conditions for functional genomics studies. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2018, 134, 567–575. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchum, M.G. Soybean resistance to the soybean cyst nematode Heterodera glycines: An update. Phytopathology 2016, 106, 1444–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chitsaz, F.; Derbyshire, M.K.; Gonzales, N.R.; Gwadz, M.; Lu, S.; Marchler, G.H.; Song, J.S.; Thanki, N.; Yamashita, R.A.; et al. The conserved domain database in 2023. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D384–D388. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, L.N.; Hu, Y.H.; Li, T.; Li, M.; Li, Y.T.; Wu, Y.Z.; Cao, J.; Tan, X.L. A GDSL motif-containing lipase modulates Sclerotinia sclerotiorum resistance in Brassica napus. Plant Physiol. 2024, 196, 2973–2988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.W.; Li, M.K.; Yang, S.G.; Gao, C.Z.; Su, Y.; Zeng, X.; Jiao, Z.L.; Xu, W.J.; Zhang, M.Y.; Xia, K.F. miR2105 and the kinase OsSAPK10 co-regulate OsbZIP86 to mediate drought-induced ABA biosynthesis in rice. Plant Physiol. 2022, 189, 889–905. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.Y.; Yuan, W.X.; Zheng, C.; Wang, X.M.; Zhou, J.; Yan, C.Q.; Chen, J.P. Role of bZIP Transcription Factors in Plant Hormone-Mediated Disease Resistance and Stress Tolerance Pathways. Acta Agric. Zhejiangensis 2017, 29, 168–175. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.X.; Srivastava, R.; Howell, S.H. Stress-induced expression of an activated form of AtbZIP17 provides protection from salt stress in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Environ. 2008, 31, 1735–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).