2.1. Response Surface Methodology-Based Optimization for an Adaptive Banana Gripper

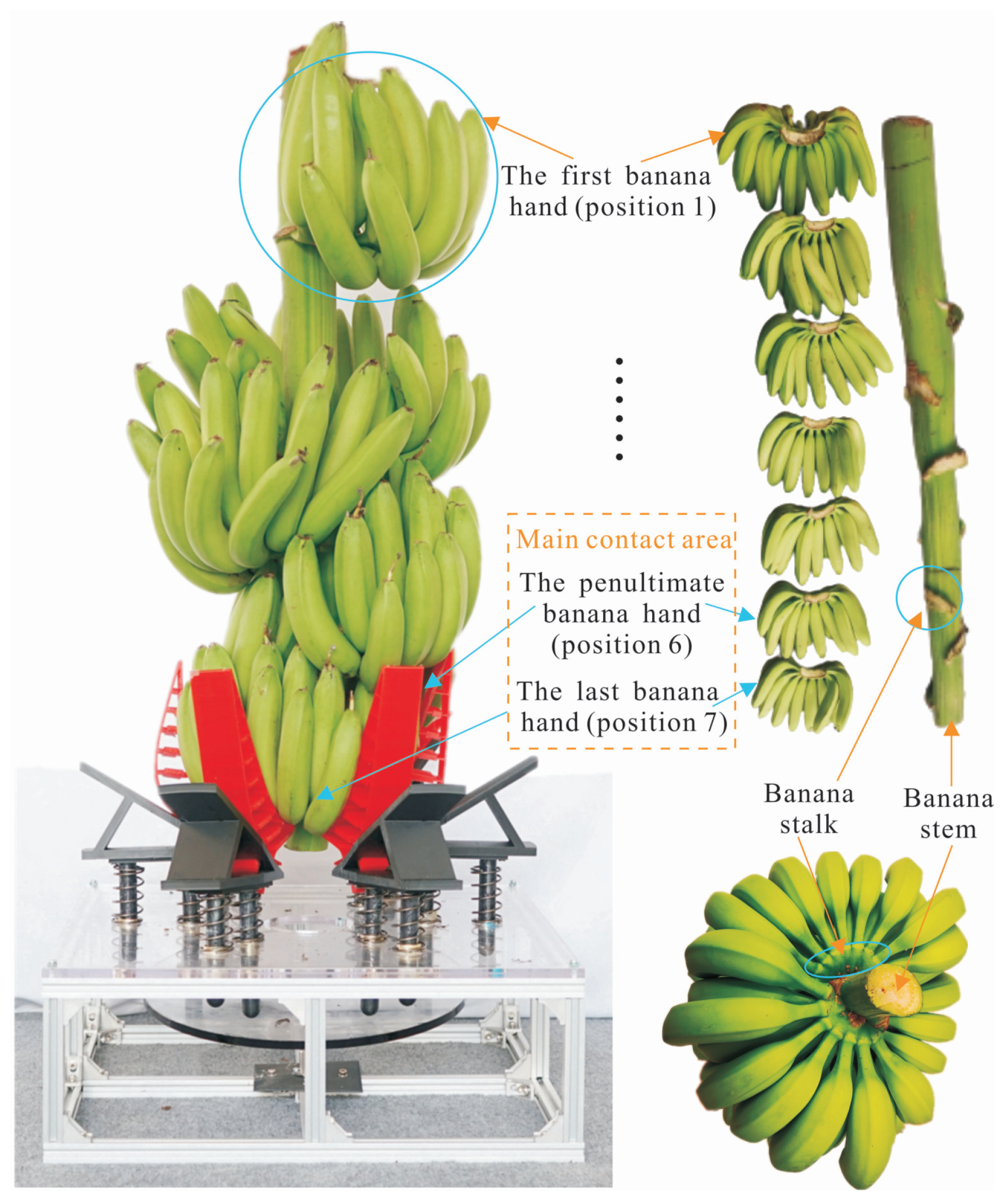

As shown in

Figure 1, the device incorporates a banana support mechanism equipped with flexible supporting fingers. These fingers were fabricated from Thermoplastic Polyurethane (TPU) with a Shore hardness of 83A using Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) 3D printing, with an infill density of 60% (TPU and 3D printer, Tuozhu Technology Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China). This material configuration was selected to ensure sufficient surface friction for stable grasping while providing the structural compliance necessary for the passive adaptive mechanism. The experimental gripper assembly comprises six flexible fingers arranged circumferentially and integrated into a passive adaptive adjustment mechanism. This configuration enables the device to automatically compensate for irregularities in banana bunch morphology, such as variations in stem curvature and differences in hand height, as confirmed through preliminary continuity and load-bearing tests.

This study applies the Response Surface Methodology (RSM) to optimize the structural parameters of the adaptive gripper. By integrating experimental design, statistical modeling, and response analysis, RSM enables the identification of key factors affecting contact performance and determines their optimal configurations, thereby enhancing the overall grasping stability and supporting capability of the flexible banana harvesting device.

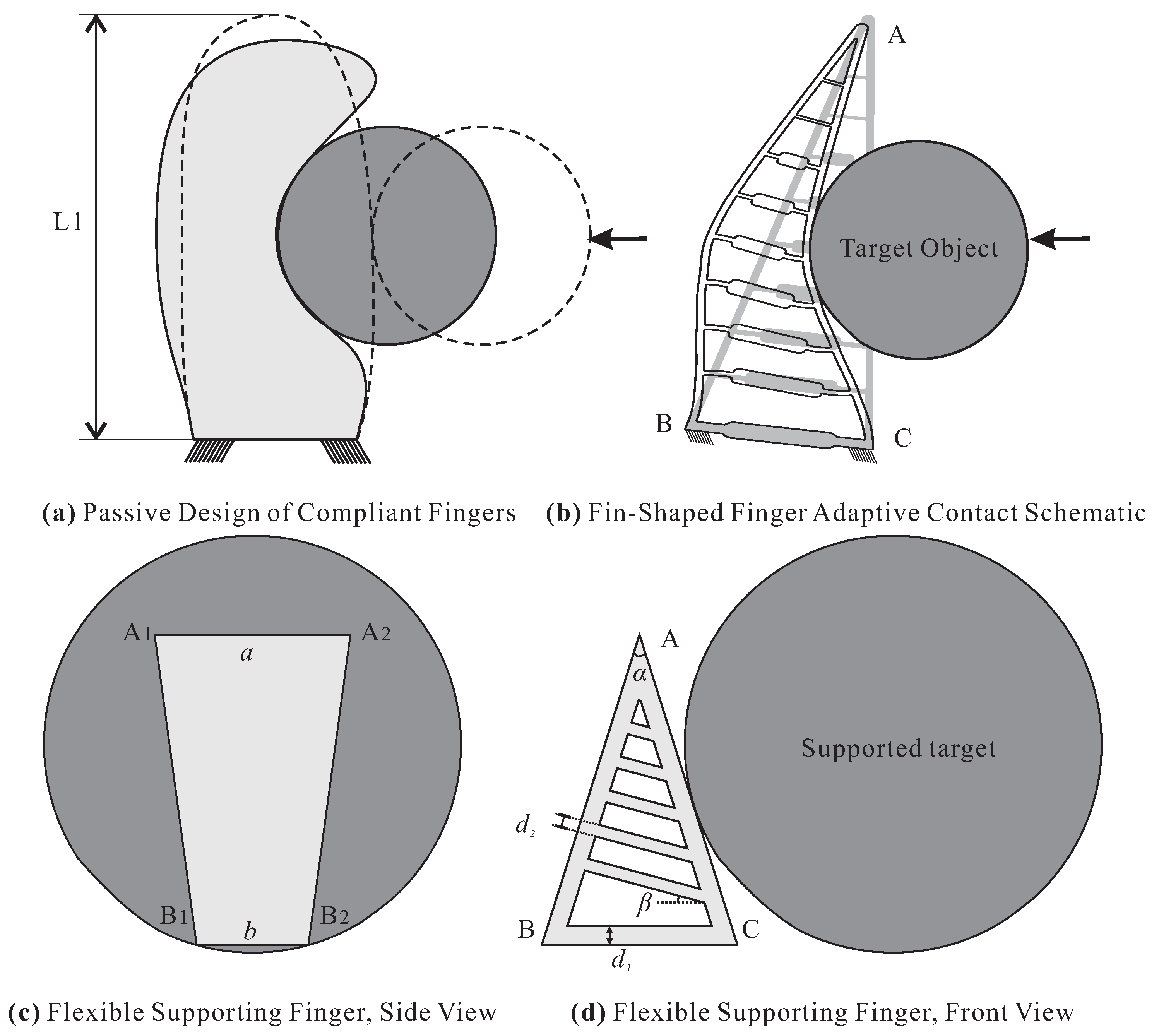

Based on the previous experimental evaluation of the flexible banana support system, a set of contact behavior constraints was introduced to guide the optimization process. The passive adaptive configuration of the supporting fingers is shown in

Figure 2. Considering the practical requirements for supporting banana bunches, the finger length

was fixed at 260 mm. The key geometric parameters selected for optimization include: the upper base length

a and lower base length

b of the trapezoidal finger section, the outer beam angle

and thickness

, the inner beam inclination angle

and thickness

, and the number of inner beams

N. The initial design parameters were set as follows:

mm,

mm,

,

mm,

,

mm, and

. These initial parameters were established based on the geometric envelope of the harvesting robot’s end-effector and the manufacturing constraints of FDM 3D printing. Specifically, the base dimensions (

) were sized to fit the average curvature of the banana hands, while the thickness values (

) were set to the minimum printable wall thickness for TPU to ensure baseline structural integrity before optimization. The optimization objective is to improve the contact interaction between the gripper and the banana bunch during harvesting. By enhancing the gripper’s surface conformity and pressure distribution uniformity, the design aims to ensure reliable grasping while minimizing mechanical damage to the fruit. Accordingly, three performance indicators were defined as optimization objectives: contact area (

A), contact stress (

), and radial static stiffness (

). The comprehensive objective function for the supporting finger design is expressed as:

The range of each optimization parameter of the banana holding finger is shown in

Table 1.

In the Response Surface Methodology (RSM), selecting an appropriate experimental design is crucial for obtaining reliable and interpretable results. Different design strategies possess distinct advantages and limitations, making each suitable for specific research objectives and experimental constraints. Considering the practical requirements and experimental complexity associated with optimizing the adaptive flexible banana support gripper, a Central Composite Design (CCD) was adopted.

After completing the experimental trials, a surrogate model was constructed to approximate the functional relationship between the input variables and output responses. Within the RSM framework, commonly used fitting models include multivariate quadratic polynomials, Kriging functions, and genetic aggregation models, each offering a trade-off between predictive accuracy and computational efficiency. Among these, the quadratic polynomial model serves as the fundamental regression form in RSM. Through variable substitution, the regression equation can be simplified into a multiple linear regression form, as expressed in Equation (

2). The regression coefficients are then obtained via least-squares estimation, yielding the final response surface model, as shown in Equation (

3). As a basic surrogate model, the quadratic polynomial offers high computational efficiency compared with more complex regression models. However, the contact behavior of the flexible finger against the irregular banana surface involves complex, non-linear deformations. Its limited capability for error control and nonlinearity representation may result in larger residual deviations in highly nonlinear systems.

The Kriging model (Equation (

4)) integrates a global polynomial trend function, typically a quadratic polynomial

, with a Gaussian stochastic process

characterized by a zero mean and a non-zero covariance structure (Equation (

5)). This hybrid formulation enables the model to exactly interpolate all sampled data points while simultaneously providing a quantitative measure of prediction uncertainty at unsampled locations. Consequently, Kriging is particularly effective for modeling complex and nonlinear relationships that cannot be captured by simpler regression methods.

The response estimate of the Kriging model is given by Equation (

6), and the variance of the estimate is expressed in Equation (

7). These two formulations enable the Kriging model to not only predict the response at any unsampled point but also quantify the uncertainty associated with each prediction. Such dual capability makes it particularly effective for modeling nonlinear and spatially correlated response surfaces, thereby improving the reliability of optimization and design analyses.

In the modeling process, a key hyperparameter controlling the covariance scale of the Kriging model is determined by Equation (

8). During the fitting stage, the global trend of the response surface is represented by a quadratic polynomial, while the local deviations are captured through a Gaussian stochastic process. For improved error control, the model utilizes the local interpolation characteristics of the Gaussian kernel, which allows the adaptive insertion of additional sampling points in regions of high nonlinearity or uncertainty. Although this approach provides better error regulation than a pure quadratic polynomial model, it also increases computational cost due to repeated matrix inversion operations within the stochastic component. Given our 7-variable design space, pure Kriging can suffer from stability issues or excessive computational costs without providing the global generalization needed for the radial stiffness objective.

The genetic aggregation response surface model, as defined in Equation (

9), integrates multiple surrogate modeling techniques—including a full quadratic polynomial, non-parametric regression, and Kriging functions—to achieve a balance between predictive robustness and computational efficiency. Our optimization needs to balance conflicting objectives: maximizing Contact Area while minimizing Contact Stress and ensuring sufficient Radial Stiffness. The Genetic Aggregation model functions as an ensemble, automatically weighing and combining different algorithms. This allows it to use the global trend capabilities of polynomials for stiffness predictions while leveraging the local adjustment capabilities of Kriging for precise stress peak prediction. In this study, the genetic aggregation model is adopted as the optimization algorithm for the flexible support gripper. By combining the complementary strengths of different surrogate models, it effectively mitigates overfitting and improves generalization performance across diverse design conditions.

The predictive accuracy of the response surface model developed using the above methodology must be quantitatively evaluated to verify its capability to represent the actual physical behavior. The coefficient of determination (

) is employed as the primary metric to assess the goodness of fit of the model, and it is defined as:

In Equation (

10),

denotes the total sum of squares, which quantifies the overall deviation of each observed response from the mean value.

represents the regression sum of squares, corresponding to the variation explained by the model, whereas

denotes the error sum of squares, reflecting the portion of variability not captured by the model. An

value approaching 1 indicates that a larger proportion of the total response variability is explained by the regression model. The three statistical terms are calculated as follows:

And the following relationship is satisfied among the three:

The coefficient of determination (

) ranges from 0 to 1, where values closer to 1 indicate smaller modeling errors and higher fitting accuracy. An

value of 1 represents a perfect fit, meaning that the model precisely captures the input–output relationship and all data points lie exactly on the response surface. However, a key limitation of

is its tendency to increase with the inclusion of additional predictor variables, even when those variables contribute little or no explanatory power. Such behavior can lead to overfitting, where the model performs well on training data but poorly on unseen data. To mitigate this problem, the adjusted coefficient of determination (

) is introduced. It incorporates a penalty term for the number of predictors, thereby providing a more reliable measure of model performance—particularly when comparing regression models with different numbers of variables. The adjusted

is defined as:

where

k denotes the number of model parameters. The adjusted coefficient of determination (

) also ranges between 0 and 1, with values closer to 1 indicating a more accurate representation of the input–output relationship by the response surface model. In general,

is slightly lower than

. A large discrepancy between the two (i.e.,

) suggests the presence of redundant or insignificant terms in the polynomial model, implying that model recalibration or parameter reduction may be necessary.

The optimization of contact behavior and radial stiffness for the adaptive banana gripper constitutes a multi-objective optimization problem (MOOP). Conventional genetic algorithms often face challenges in effectively resolving the trade-offs among competing objectives in such problems. To address this, a Multi-Objective Genetic Algorithm (MOGA) is employed. This algorithm mimics natural selection and genetic operations to evolve a population of candidate designs toward the Pareto front. The optimization variables are classified as continuous or discrete, depending on their nature. Continuous variables can assume any value within a specified range. For these variables, crossover and mutation operations—defined by Equations (

14) and (

15), respectively—are applied to generate new candidate solutions during the evolutionary process.

Based on the optimization objectives for contact behavior and radial stiffness of the adaptive banana supporting finger, a Multi-Objective Genetic Algorithm (MOGA) was employed to optimize its structural parameters. MOGA is particularly suitable for handling mixed variables, including continuous parameters (e.g., geometric dimensions) and discrete parameters (e.g., standard manufacturing specifications), without requiring explicit functional expressions to propagate parameter information to offspring. The algorithm begins with the random generation of an initial population of potential solutions. Through selection, crossover, and mutation operations, parental genetic information is recombined and passed on to offspring. Discrete variables, representing non-continuous parameter values, are processed via recombination and random alteration rather than formula-based computation. During each iteration, individuals satisfying the optimization conditions are selected, elite members are retained, and new offspring are generated to maintain the population size. This cycle of selection and genetic variation continues until the convergence criteria are met. By applying MOGA, the multi-objective optimization of the supporting finger’s contact behavior and radial stiffness was successfully achieved. The resulting design effectively balances competing performance requirements without introducing complex sensing or control systems.

2.2. Multi-Objective Optimization of Flexible Banana Supporting Fingers

To reduce computational complexity while maintaining generality and representativeness, a single flexible finger was selected as the optimization unit, as the supporting device comprises six fingers arranged circumferentially around the central frame. A simplified support target was constructed based on the morphological characteristics of banana bunches, as illustrated in

Figure 2a,b.

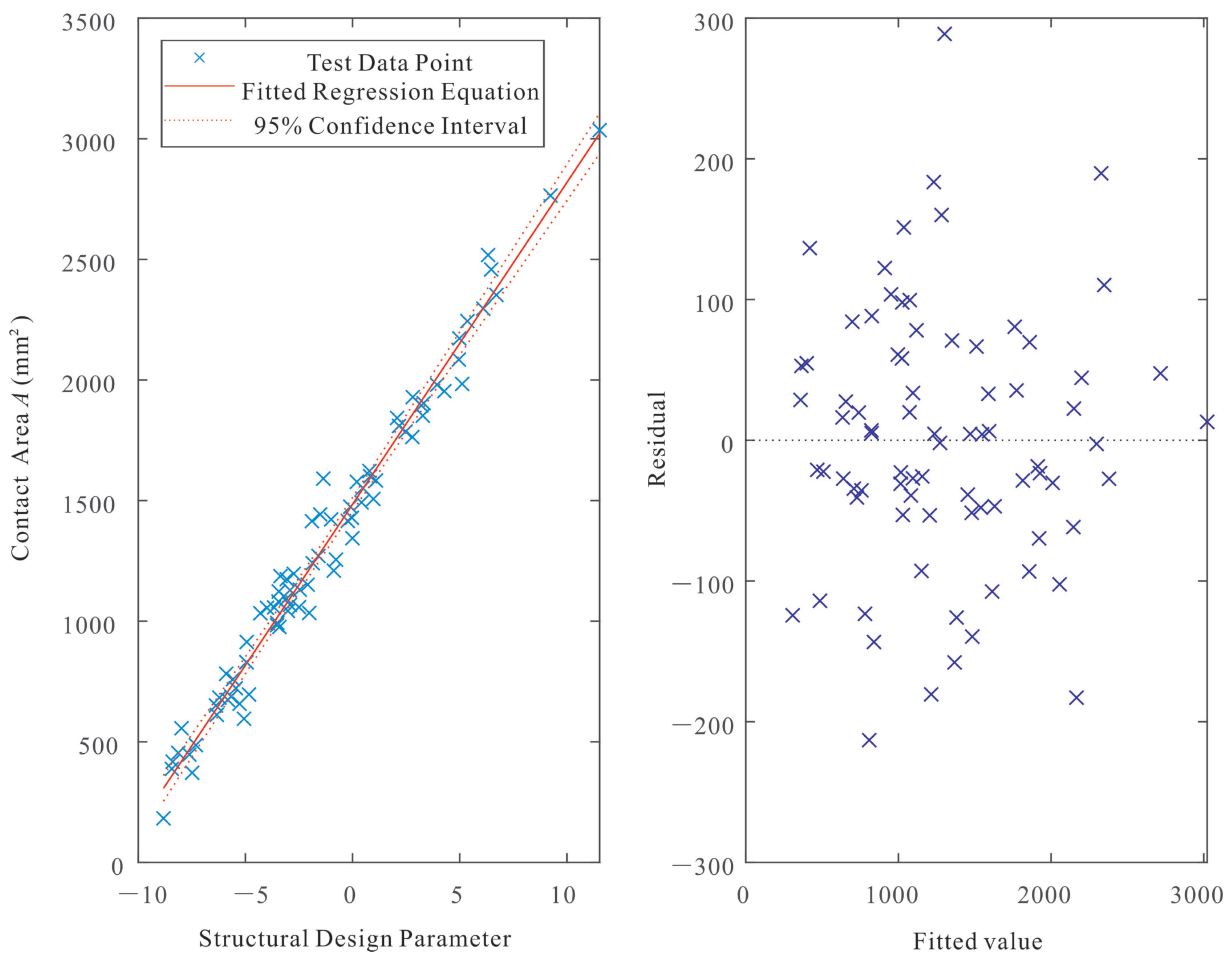

Using the fundamental principles of a genetic algorithm, the structural parameters influencing contact behavior and radial static stiffness of the flexible finger were optimized to generate a Pareto-optimal solution set. From this set, the best parameter combination was selected to determine the final structural design, thereby enhancing the overall adaptability, force distribution uniformity, and stability of the supporting device. A multiple regression model was fitted to the experimental data using MATLAB R2020b, establishing the relationship between the contact area (

A) and key geometric parameters of the trapezoidal section of the flexible finger: the upper base length (

a), lower base length (

b), outer beam angle (

), outer beam thickness (

), inner beam inclination angle (

), inner beam thickness (

), and the number of inner beams (

N). This relationship is expressed in Equation (

16), and the corresponding fit is visualized in

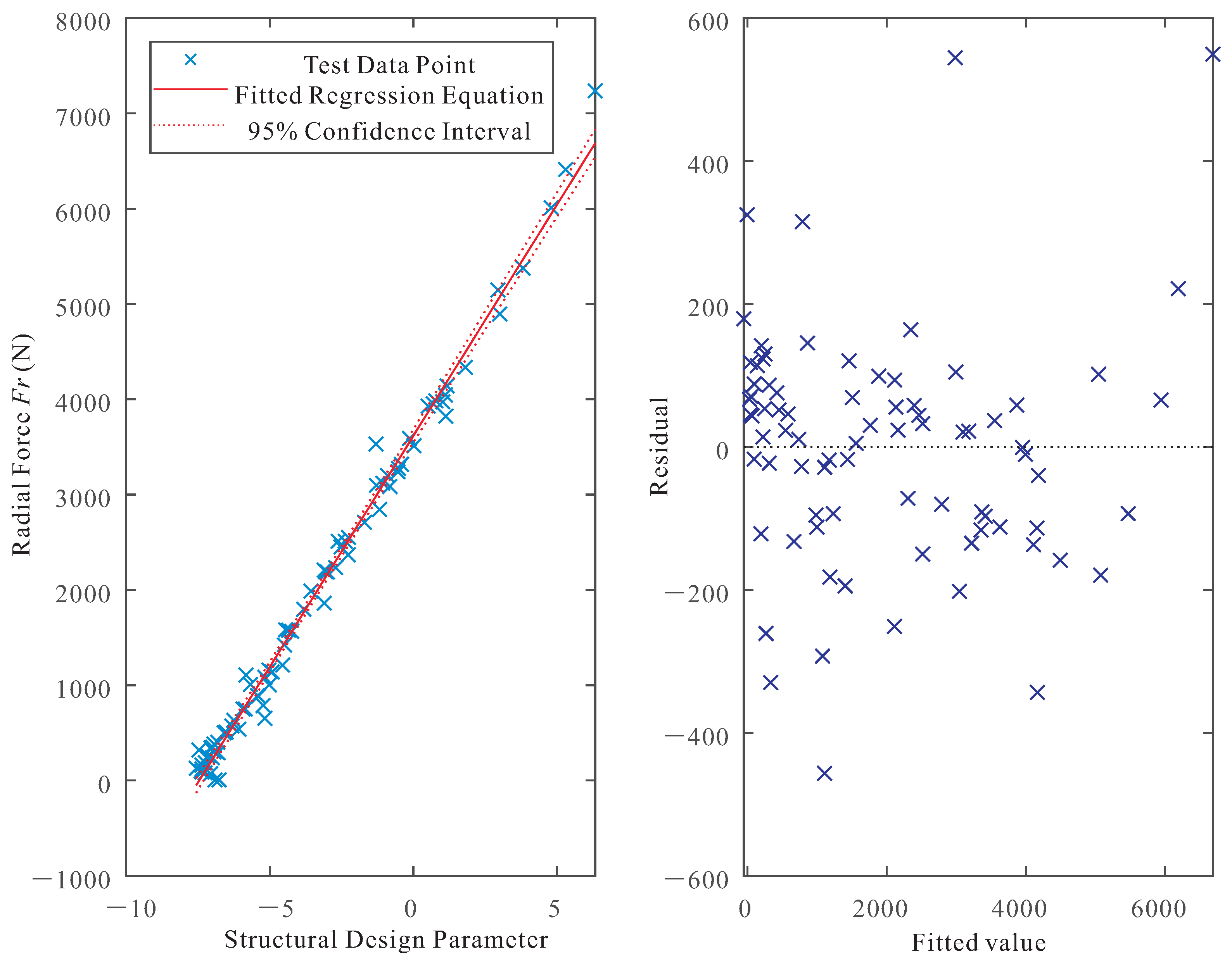

Figure 3.

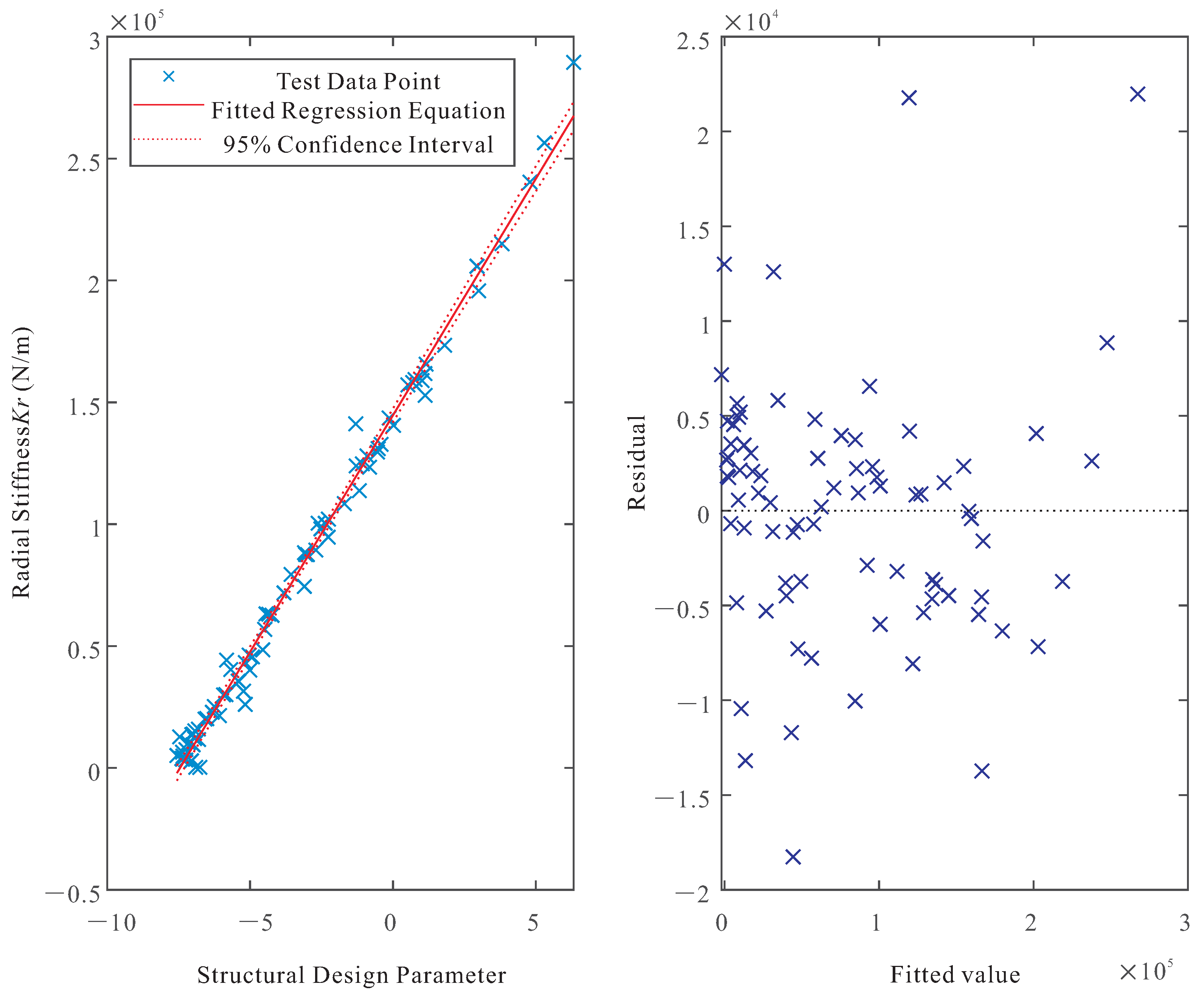

Error analysis performed on all response surface models, using an F-test, indicated that the probability of model unreliability was less than 1%, confirming the model’s ability to accurately represent the underlying input-output statistical relationship. Furthermore, the residual plots presented in

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 show a random distribution of residuals around the zero line, confirming that the model has no systematic bias and adequately captures the nonlinear behavior across the parameter range. The coefficient of determination (

) for the contact area model was 0.977, while the adjusted coefficient of determination (

) was 0.959. These values indicate that approximately 95.9% of the variation in contact area can be attributed to the structural parameters of the flexible finger, demonstrating a well-fitted response model that effectively captures the input-output relationship.

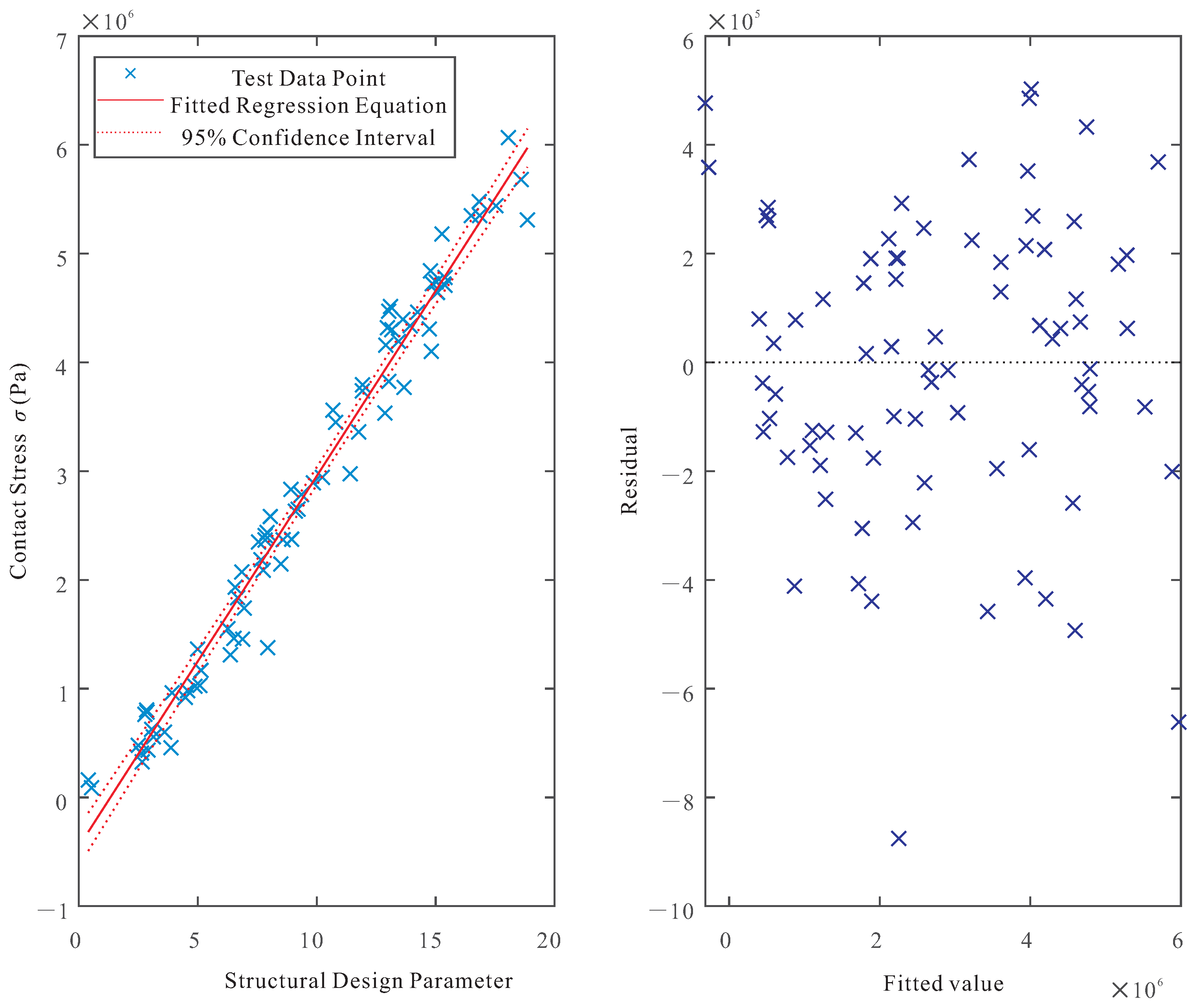

The relationship between contact stress (

) and the key geometric parameters of the trapezoidal section of the flexible finger—including the upper base length (

a), lower base length (

b), outer beam angle (

), outer beam thickness (

), inner beam inclination angle (

), inner beam thickness (

), and the number of inner beams (

N)—was modeled using a multiple regression equation, as given in Equation (

17). The corresponding fit is illustrated in

Figure 4.

The coefficient of determination () for the contact stress model was 0.974, while the adjusted coefficient of determination () was 0.954. These values indicate that approximately 95.4% of the observed variation in contact stress can be attributed to the combined effects of the specified structural parameters, confirming the model’s excellent predictive capability.

The relationship between radial force (

) and the key geometric parameters of the trapezoidal section of the flexible finger—including the upper base length (

a), lower base length (

b), outer beam angle (

), outer beam thickness (

), inner beam inclination angle (

), inner beam thickness (

), and the number of inner beams (

N)—was modeled using a multiple regression equation, as given in Equation (

18). The corresponding fit is illustrated in

Figure 5.

The coefficient of determination (

) for the radial force model was 0.992, while the adjusted coefficient of determination (

) was 0.984. These values indicate that approximately 98.4% of the observed variation in radial force can be attributed to the combined effects of the specified structural parameters, confirming the model’s excellent predictive capability.

Similarly, the relationship between radial stiffness (

) and the key geometric parameters of the trapezoidal section was modeled using a multiple regression equation, as given in Equation (

19). The corresponding fit is illustrated in

Figure 6. The

and

values for the radial stiffness model were 0.992 and 0.984, respectively, indicating that approximately 98.4% of the observed variation in radial stiffness is explained by the combined effects of the structural parameters. These results confirm that the regression models provide excellent predictive capability for both radial force and stiffness.

By leveraging these regression models, the contact behavior and radial stiffness of the adaptive banana gripper can be effectively optimized. This enables the identification of the optimal combination of structural parameters for the flexible fingers, thereby enhancing grasping performance while minimizing mechanical damage to the fruit.

2.3. Analysis of Response Surface Results for Flexible Supporting Fingers

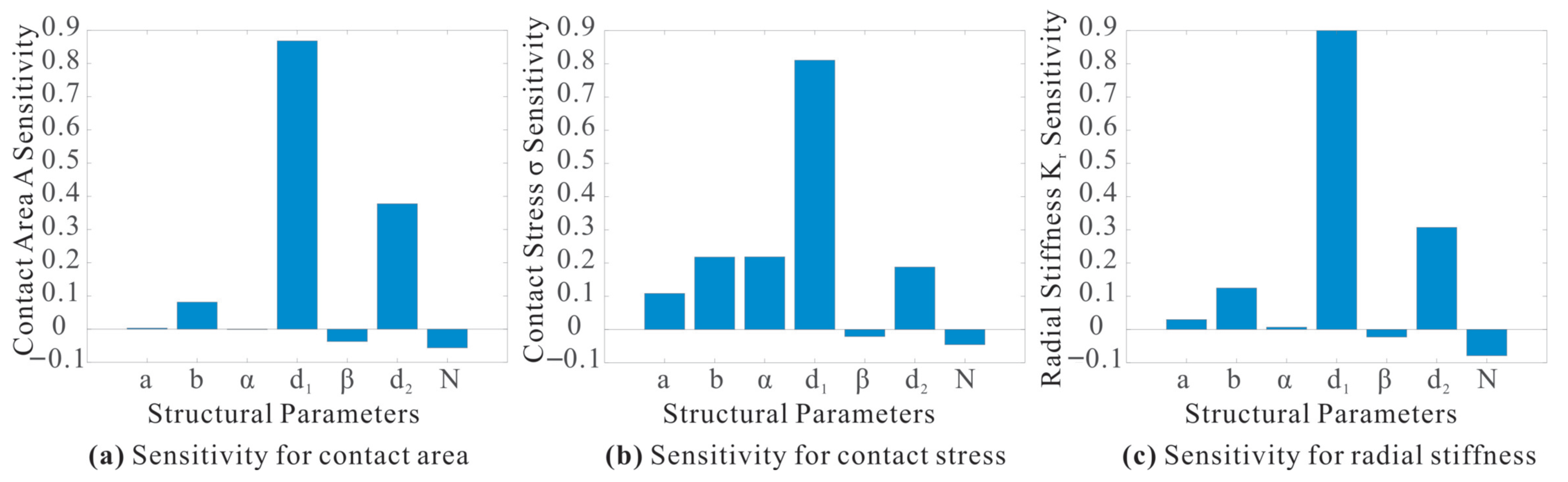

Sensitivity analysis provides a scientific basis for design decisions in the development of pick-up grippers, enabling the identification of key design variables that significantly influence output performance. This approach supports targeted design improvements, leading to more reliable and higher-quality products while optimizing manufacturing costs without compromising performance. A correlation analysis of the experimental data was conducted, and the sensitivity of the trapezoidal structural parameters of the flexible finger to the contact area was quantified, as shown in

Figure 7a.

The magnitude of sensitivity reflects the degree to which each input parameter affects the target output. As illustrated in

Figure 7a, the sensitivity of each design variable to contact area varies significantly. The trapezoidal base length

a and the outer beam angle

exhibit the lowest sensitivity to contact area, indicating that their individual effects on contact area during support operations are minimal. However, as shown in

Figure 7b, both parameters demonstrate high sensitivity to contact stress (

), and therefore cannot be neglected in the overall optimization process.

By contrast, the outer beam thickness (

) shows high sensitivity to both contact behavior and radial stiffness (

), highlighting its critical influence on overall support performance. Furthermore, because the banana initially contacts the region near the base of the flexible finger during operation, the lower base length (

b) of the trapezoidal section has a stronger effect on contact performance than the upper base length (

a). This observation aligns with the sensitivity patterns presented in

Figure 7.

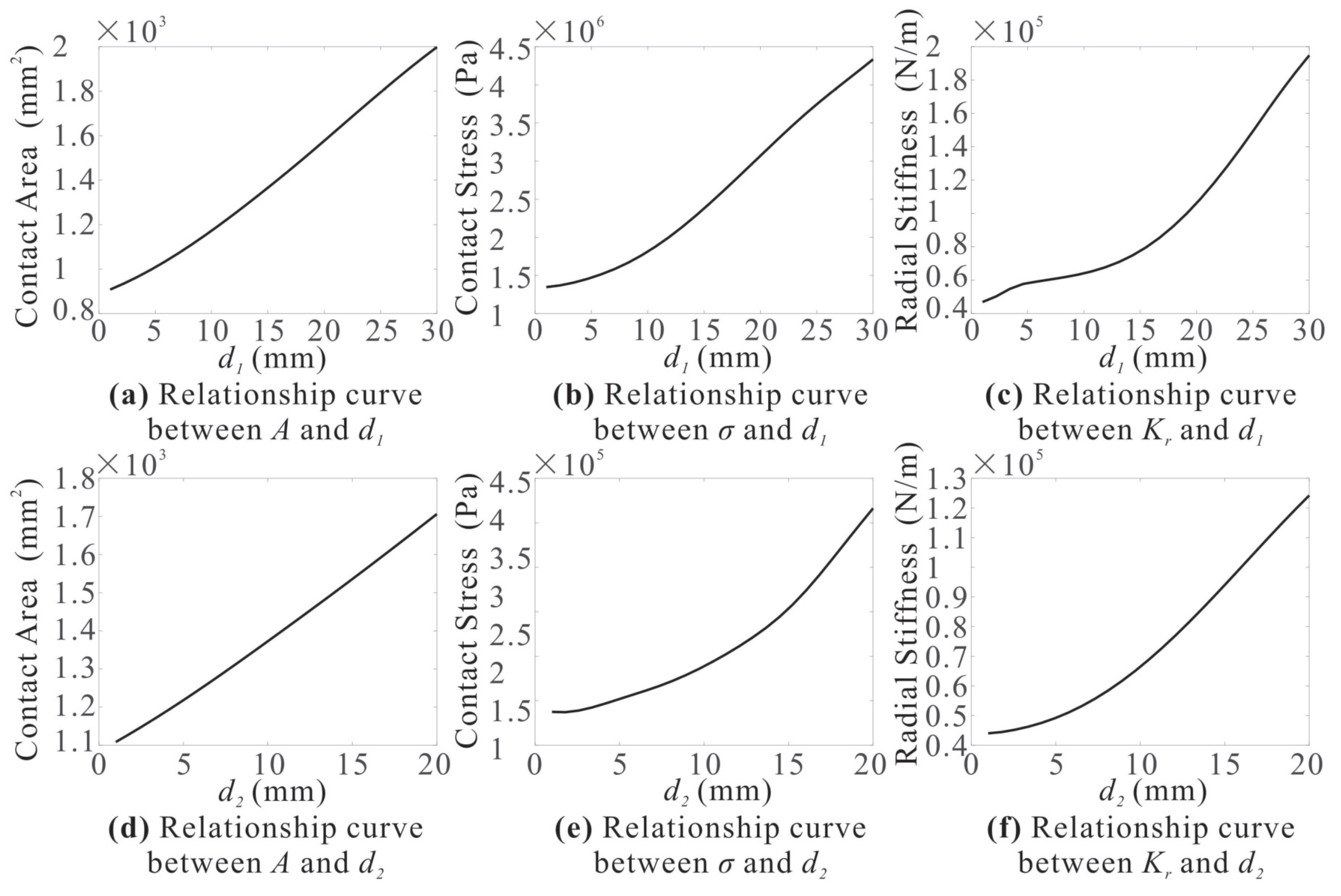

In addition, the relationships between the structural design parameters of the flexible finger and the key performance targets for docking tasks were established. Correlation curves illustrating the influence of the maximum outer beam thickness (

) and inner beam thickness (

) on the output responses are presented in

Figure 8.

The results indicate that the contact area increases approximately linearly with both outer and inner beam thicknesses.

In contrast, contact stress () and radial stiffness () exhibit distinct nonlinear growth patterns depending on the parameter range. When the outer beam thickness is below 15 mm, both contact stress and radial stiffness increase nonlinearly, with the rate of change accelerating as increases. Beyond mm, the responses transition to an approximately linear growth trend. Similarly, the inner beam thickness shows a nonlinear relationship with contact stress and radial stiffness, with the magnitude of increase becoming more pronounced for larger values.

Based on the experimental sample data, response surface models were constructed to characterize the relationships between the key design parameters of the flexible finger structure—including outer beam thickness (

), inner beam thickness (

), trapezoidal lower base length (

b), and outer beam angle (

)—and the corresponding output performance targets. The resulting response surfaces are illustrated in

Figure 9.

Analysis of the response surfaces indicates that the interaction between the thickness and dimensional parameters of the inner and outer beams has a substantially greater influence on the output targets than the interaction between the trapezoidal lower base length (b) and the outer beam angle (). The combined effect of beam thickness and size on contact area is approximately linear, whereas its influence on contact stress () and radial stiffness () exhibits a nonlinear increasing trend.

In contrast, the response surface corresponding to b and displays distinct peaks and troughs, indicating a more complex interactive behavior. These results suggest that the influence of the lower base length (b) on the output responses is predominantly linear, while the outer beam angle () follows a pronounced nonlinear relationship. The presence of characteristic peaks and troughs further validates the appropriateness of the selected upper and lower bounds for the optimized design parameters.