Technosol Construction for Sustainable Agriculture: Research Status and Prospects

Abstract

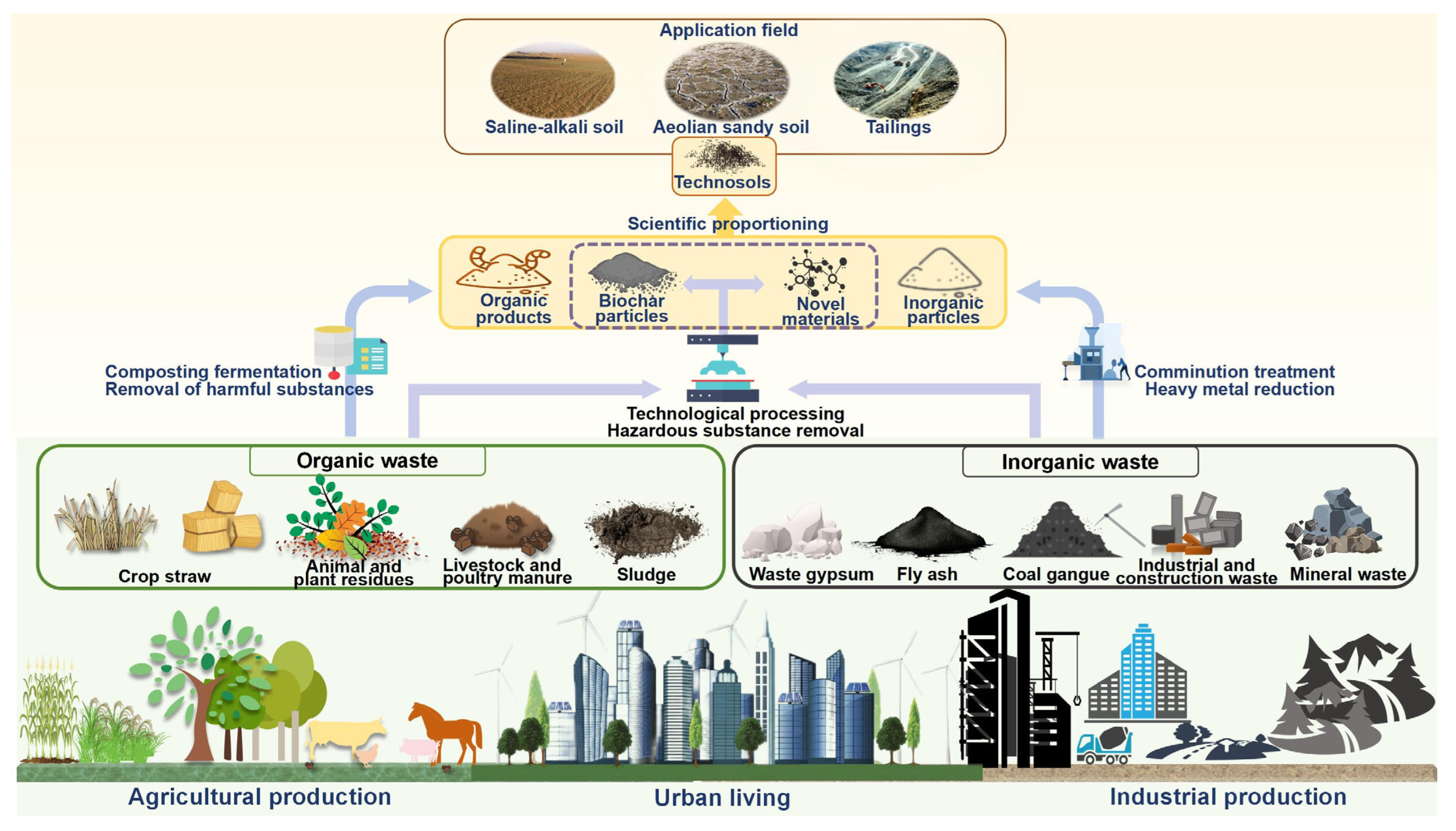

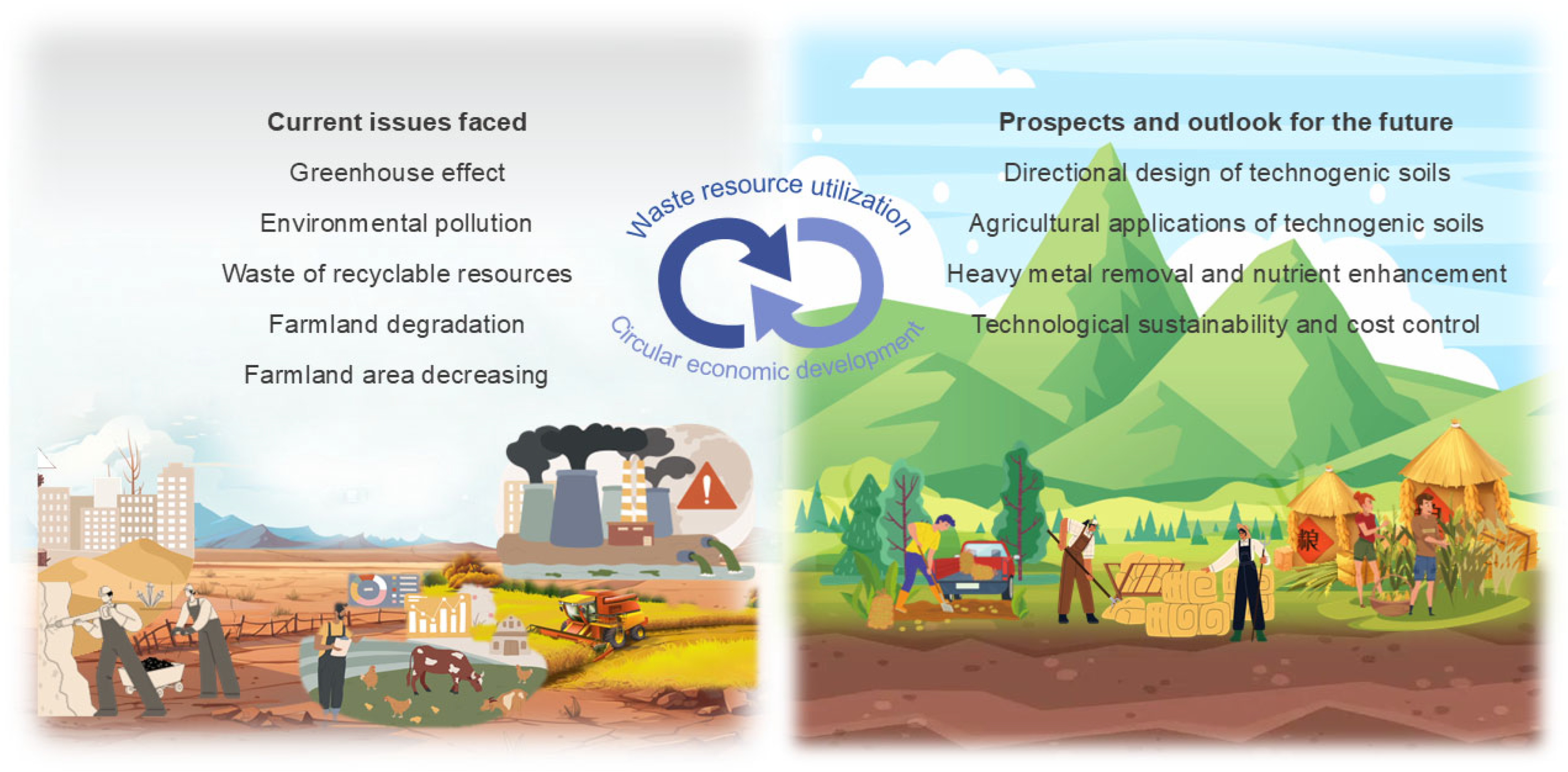

1. Introduction

2. Waste Sources and Characteristics for Technosol Construction

2.1. Livestock and Poultry Waste

2.2. Crop Straw

2.3. Biochar

2.4. Industrial and Construction Waste

2.5. Mineral Waste

2.6. Coal Gangue and Fly Ash

2.7. Waste Gypsum

3. Issues in Waste Utilization During the Technosol Construction

3.1. Soil Degradation

3.2. Pest and Disease Risk

3.3. Heavy Metal Pollution

3.4. Antibiotic Residues

3.5. Lack of Economic Viability

4. Application of Novel Nanomaterials in the Construction of Technosols

4.1. Nanozyme

4.2. Nano-Hydroxyapatite (nHA)

4.3. Nanocarbon

4.4. Nanoscale Zero-Valent Iron (nZVI)

4.5. Nano-Titanium Dioxide (Nano-TiO2)

5. Agroecological Impacts of Technosol Application

5.1. Soil Property Improvement and Carbon Sequestration Potential

5.2. Soil Biological Activity

5.3. Crop Growth Response

5.4. Soil Pollution Remediation

6. Conclusions and Future Research Perspectives

- (1)

- Targeted design of Technosols for agricultural applications. Conduct systematic research on the agricultural suitability of diverse waste materials. Develop targeted Technosols formulations to address specific soil issues (e.g., nutrient deficiency, heavy metal/organic pollution, salinization) and application contexts (e.g., tailings reclamation, desert restoration, urban soil rehabilitation). Optimize raw material pretreatment and mixing ratios to balance nutrient supply and soil physical structure [102]. Integrate techniques such as straw incorporation, green manure cultivation, and humic-promoting agents to shorten soil maturation cycles. Establish a coordinated “urban-industrial-agricultural” waste utilization chain, promote standardization of Technosols in agriculture, and formulate supportive policies to enhance ecological compensation and land restoration incentives.

- (2)

- Construction technologies and efficacy of novel nanomaterial-enhanced Technosols. Develop novel materials capable of passivating, adsorbing, or degrading pollutants to mitigate their translocation risks in soil-crop systems. Investigate the dispersion stability and mechanisms of materials like nano-hydroxyapatite and graphene in soils, focusing on their effects on nutrient release and microbial activity. Enhance nutrient retention and erosion resistance of Technosols through chemical modifications. Explore stimuli-responsive materials (e.g., thermo-/photo-sensitive hydrogels, shape-memory polymers) for adaptive regulation of soil aeration and water retention. Design stratified functional systems for Technosols with surface evaporation suppression, rhizosphere microbiome activation, and deep-layer pollutant immobilization. The environmental application of nanomaterials must address two intertwined challenges: their potential mobility in porous soils and the difficulty of achieving uniform dispersion at scale. In sandy or highly permeable soils, nanoparticles risk leaching or uptake by biota. This could be mitigated by immobilization strategies such as surface functionalization for strong soil binding, encapsulation within stable matrices (e.g., biochar), or in situ synthesis to create fixed reactive sites. Concurrently, the pursuit of perfect pore-scale homogeneity is being replaced by pragmatic delivery methods for functional efficacy. These include using granular composite carriers for mechanical spreading, creating targeted treatment zones (e.g., reactive barriers), and employing improved mixing techniques to ensure predictable nanoparticle performance in field-scale applications without requiring uniform dispersion.

- (3)

- Ecological effects and application assessment of agricultural Technosols. Integrate soil biome and microbiome design into Technosols construction to evaluate changes in soil biodiversity and functionality. Introduce functional microorganisms to accelerate soil network formation and assess their impacts on soil health and crop growth. Establish dynamic monitoring systems to study key nutrient cycles and long-term pollutant release patterns in reclaimed soils, evaluating risks to the food chain. Develop low-carbon Technosols technologies to enhance ecosystem services, carbon sequestration, and emission reduction potential.

- (4)

- Economic efficiency enhancement of agricultural Technosols. Utilize localized waste resources based on regional natural endowments to reduce transportation costs and associated environmental risks. Conduct comprehensive economic feasibility assessments, including life cycle analysis (LCA) to quantify energy consumption and carbon footprints from material production to waste recycling. Cultivate high-value cash crops within ecological safety thresholds to maximize overall economic benefits. Formulate engineering application specifications to support scalable implementation under varying scenarios (e.g., heavy metal-contaminated farmland, desertified land). The scalability of nano-enabled agriculture hinges on economic viability. While precision nanomaterials can be costly, research into low-cost synthesis routes is mitigating this barrier. Notably, green synthesis using plant extracts or agricultural waste provides an economical and sustainable alternative to conventional chemical synthesis. Furthermore, the direct use of engineered waste streams (e.g., nano-structured biochar from crop residues, mineral nano-by-products from industry) aligns nanotechnology with circular economy models, transforming low-value waste into high-value soil amendments. A full techno-economic assessment that accounts for reduced input costs (e.g., fertilizers) and enhanced crop resilience is needed to accurately evaluate the net benefit of these nano-formulations at scale.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rodríguez-Espinosa, T.; Navarro-Pedreño, J.; Gómez-Lucas, I.; Jordán-Vidal, M.M.; Bech-Borras, J.; Zorpas, A.A. Urban areas, human health and technosols for the green deal. Environ. Geochem. Health 2021, 43, 5065–5086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soria, R.; González-Pérez, J.A.; de la Rosa, J.M.; San Emeterio, L.M.; Domene, M.A.; Ortega, R.; Miralles, I. Effects of technosols based on organic amendments addition for the recovery of the functionality of degraded quarry soils under semiarid Mediterranean climate: A field study. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 816, 151572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, Y.; Cui, B.; Wang, Z.; Sun, J.; Niu, W. Effects of manure fertilizer on crop yield and soil properties in China: A meta-analysis. Catena 2020, 193, 104617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginni, G.; Kavitha, S.; Kannah, Y.; Bhatia, S.K.; Kumar, A.; Rajkumar, M.; Kumar, G.; Pugazhendhi, A.; Chi, N.T.L. Valorization of agricultural residues: Different biorefinery routes. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 105435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rees, F.; Dagois, R.; Derrien, D.; Fiorelli, J.L.; Watteau, F.; Morel, J.L.; Schwartz, C.; Simonnot, M.O.; Séré, G. Storage of carbon in constructed technosols: In situ monitoring over a decade. Geoderma 2019, 337, 641–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, F.; Cherubin, M.R.; Ferreira, T.O. Soil quality assessment of constructed Technosols: Towards the validation of a promising strategy for land reclamation, waste management and the recovery of soil functions. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 276, 111344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiler, J.; Firpo, B.A.; Schneider, I.A. Technosol as an integrated management tool for turning urban and coal mining waste into a resource. Miner. Eng. 2020, 147, 106179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoah-Antwi, C.; Kwiatkowska-Malina, J.; Thornton, S.F.; Fenton, O.; Malina, G.; Szara, E. Restoration of soil quality using biochar and brown coal waste: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 722, 137852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrón, D.B.; Capa, J.; Flores, L.C. Retention of heavy metals from mine tailings using Technosols prepared with native soils and nanoparticles. Heliyon 2021, 7, e07631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Y.; Al-Kaisi, M.; Yuan, J.; Liu, J.; Zhang, H.; Wang, L.; Cai, H.; Ren, J. Effect of chemical fertilizer and straw-derived organic amendments on continuous maize yield, soil carbon sequestration and soil quality in a Chinese Mollisol. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2021, 314, 107403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Garrido, A.; Romero-Freire, A.; Paniagua-López, M.; Martínez-Garzón, F.J.; Martín-Peinado, F.J.; Sierra-Aragón, M. Technosols derived from mining, urban, and agro-industrial waste for the remediation of metal (loid)-polluted soils: A microcosm assay. Toxics 2023, 11, 854. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Olivo, E.F.; Zaccaron, A.; Acordi, J.; Ribeiro, M.J.; Fernandes, É.M.R.; Zocche, J.J.; Raupp-Pereira, F. Technosol development based on residual fraction of coal tailings processing, agro-industrial waste, and paper industry waste. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mujtaba, M.; Fraceto, L.F.; Fazeli, M.; Mukherjee, S.; Savassa, S.M.; de Medeiros, G.A.; Santo Pereira, A.D.E.; Mancini, S.D.; Lipponen, J.; Vilaplana, F. Lignocellulosic biomass from agricultural waste to the circular economy: Areview with focus on biofuels biocomposites bioplastics. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 402, 136815. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz, F.; Perlatti, F.; Oliveira, D.P.; Ferreira, T.O. Revealing tropical technosols as an alternative for mine reclamation and waste management. Minerals 2020, 10, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deeb, M.; Groffman, P.M.; Blouin, M.; Egendorf, S.P.; Vergnes, A.; Vasenev, V.; Cao, D.L.; Walsh, D.; Morin, T.; Séré, G. Using constructed soils for green infrastructure–challenges and limitations. Soil 2020, 6, 413–434. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, X.C.; Han, F.; Yang, G.T.; Wu, J.G.; Ma, Y. Enhanced soil ecosystem multifunctionality and microbial community shifts following spent mushroom substrate application in vineyards. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2025, 213, 106230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozłowski, M.; Otremba, K.; Tatuśko-Krygier, N.; Komisarek, J.; Wiatrowska, K. The effect of an extended agricultural reclamation on changes in physical properties of technosols in post-lignite-mining areas: A case study from central Europe. Geoderma 2022, 410, 115664. [Google Scholar]

- Hua, K.; Zhang, W.; Guo, Z.; Wang, D.; Oenema, O. Evaluating crop response and environmental impact of the accumulation of phosphorus due to long-term manuring of vertisol soil in northern China. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2016, 219, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zhu, L.; Chen, S.; Wu, H.; Li, R.; Li, J.; Yuan, J.; Wen, T.; Xue, C.; Shen, Q. Risk assessment and dissemination mechanism of antibiotic resistance genes in compost. Environ. Int. 2023, 178, 108126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Li, H.; Zhu, S.; Gao, Y.; Zheng, X.; Xu, Y. The response of agronomic characters and rice yield to organic fertilization in subtropical China: A three-level meta-analysis. Field Crops Res. 2021, 263, 108049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Sun, S.; Yao, B.; Peng, Y.; Gao, C.; Qin, T.; Zhou, Y.; Sun, C.; Quan, W. Effects of straw return and straw biochar on soil properties and crop growth: A review. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 986763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, J.; Tao, M.; Wang, L.; Liu, X.; Xu, J. Changes in heavy metal bioavailability and speciation from a Pb-Zn mining soil amended with biochars from co-pyrolysis of rice straw and swine manure. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 633, 300–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.S.; Lim, S.S.; Park, H.J.; Yang, H.I.; Park, S.I.; Kwak, J.H.; Choi, W.J. Fly ash and zeolite decrease metal uptake but do not improve rice growth in paddy soils contaminated with Cu and Zn. Environ. Int. 2019, 129, 551–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Chen, Z.; Wen, Q. Impacts of biochar on anaerobic digestion of swine manure: Methanogenesis and antibiotic resistance genes dissemination. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 324, 124679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S.H.; Chafik, Y.; Sena-Velez, M.; Lebrun, M.; Scippa, G.S.; Bourgerie, S.; Trupiano, D.; Morabito, D. Importance of application rates of compost and biochar on soil metal (loid) immobilization and plant growth. Plants 2023, 12, 2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruvost, C.; Mathieu, J.; Nunan, N.; Gigon, A.; Pando, A.; Lerch, T.Z.; Blouin, M. Tree growth and macrofauna colonization in Technosols constructed from recycled urban wastes. Ecol. Eng. 2020, 153, 105886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbruzzini, T.F.; Reyes-Ortigoza, A.L.; Alcántara-Hernández, R.J.; Mora, L.; Flores, L.; Prado, B. Chemical, biochemical, and microbiological properties of Technosols produced from urban inorganic and organic wastes. J. Soils Sediments 2022, 22, 146–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, J.O.; Fruto, C.M.; Barranco, M.J.; Oliveira, M.L.S.; Ramos, C.G. Recovery of degraded areas through technosols and mineral nanoparticles: A review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrández-Gómez, B.; Jordá, J.D.; Sánchez-Sánchez, A.; Cerdán, M. Characterization of Technosols for Urban Agriculture. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozłowski, M.; Otremba, K.; Pająk, M.; Pietrzykowski, M. Changes in physical and water retention properties of Technosols by agricultural reclamation with wheat–Rapeseed rotation in a post-mining area of Central Poland. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slukovskaya, M.V.; Vasenev, V.I.; Ivashchenko, K.V.; Morev, D.V.; Drogobuzhskaya, S.V.; Ivanova, L.A.; Kremenetskaya, I.P. Technosols on mining wastes in the subarctic: Efficiency of remediation under Cu-Ni atmospheric pollution. Int. Soil Water Conserv. Res. 2019, 7, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, F.; Sartor, L.R.; de Souza Júnior, V.S.; dos Santos, J.C.B.; Ferreira, T.O. Fast pedogenesis of tropical Technosols developed from dolomitic limestone mine spoils (SE-Brazil). Geoderma 2020, 374, 114439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, T.; Wang, D.; Bai, Y.; Zhang, Z. Optimizing the formulation of coal gangue planting substrate using wastes: The sustainability of coal mine ecological restoration. Ecol. Eng. 2020, 143, 105669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alterary, S.S.; Marei, N.H. Fly ash properties characterization applications: Areview. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2021, 33, 101536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Zhu, X.; Chen, C.; Yang, B.; Pandey, V.C.; Liu, W.; Singh, N. Investigating the recovery in ecosystem functions and multifunctionality after 10 years of natural revegetation on fly ash technosol. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 875, 162598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koralegedara, N.H.; Pinto, P.X.; Dionysiou, D.D.; Al-Abed, S.R. Recent advances in flue gas desulfurization gypsum processes applications—A review. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 251, 109572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.W.; Luo, X.H.; Li, C.X.; Millar, G.J.; Jiang, J.; Xue, S.G. Variation of alkaline characteristics in bauxite residue under phosphogypsum amendment. J. Cent. South Univ. 2019, 26, 361–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Liu, W.; Jiao, F.; Qin, W.; Yang, C. Production and resource utilization of flue gas desulfurized gypsum in China—A review. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 288, 117799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Li, X.; Yu, L.; Wang, T.; Wang, J.; Liu, T. Review of soil heavy metal pollution in China: Spatial distribution, primary sources, and remediation alternatives. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 181, 106261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seow, Y.X.; Tan, Y.H.; Mubarak, N.M.; Kansedo, J.; Khalid, M.; Ibrahim, M.L.; Ghasemi, M. Areview on biochar production from different biomass wastes by recent carbonization technologies its sustainable applications. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 107017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alidou-Arzika, I.; Lebrun, M.; Miard, F.; Nandillon, R.; Bayçu, G.; Bourgerie, S.; Morabito, D. Assessment of compost and three biochars associated with Ailanthus altissima (Miller) Swingle for lead and arsenic stabilization in a post-mining Technosol. Pedosphere 2021, 31, 944–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebrun, M.; Miard, F.; Hattab-Hambli, N.; Scippa, G.S.; Bourgerie, S.; Morabito, D. Effect of different tissue biochar amendments on As and Pb stabilization and phytoavailability in a contaminated mine technosol. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 707, 135657. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, X.; Wang, X.; Wu, J.; He, P. Both carbon sequestration yield are related to particulate organic carbon stability affected by organic amendment origins in mollisol. J. Soils Sediments 2021, 21, 3044–3056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meena, M.D.; Yadav, R.K.; Narjary, B.; Yadav, G.; Jat, H.S.; Sheoran, P.; Meena, M.K.; Antil, R.S.; Meena, B.L.; Singh, H.V.; et al. Municipal solid waste (MSW): Strategies to improve salt affected soil sustainability: A review. Waste Manag. 2019, 84, 38–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deus, A.C.F.; Büll, L.T.; Guppy, C.N.; Santos, S.D.M.C.; Moreira, L.L.Q. Effects of lime and steel slag application on soil fertility and soybean yield under a no till-system. Soil Tillage Res. 2020, 196, 104422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, T.; Zhang, C.L.; Feng, Z.; Yuan, S.X.; Ying, G.; Xue, S.G. Effect of phosphogypsum on saline-alkalinity and aggregate stability of bauxite residue. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2021, 31, 1484–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadwick, D.; Wei, J.; Yan’an, T.; Guanghui, Y.; Qirong, S.; Qing, C. Improving manure nutrient management towards sustainable agricultural intensification in China. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2015, 209, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Ma, J.; Rong, Z.; Zeng, D.; Wang, Y.; Hu, S.; Ye, W.; Zheng, X. Wheat straw return influences nitrogen-cycling and pathogen associated soil microbiota in a wheat–soybean rotation system. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivashchenko, K.; Lepore, E.; Vasenev, V.; Ananyeva, N.; Demina, S.; Khabibullina, F.; Vaseneva, I.; Selezneva, A.; Dolgikh, A.; Sushko, S.; et al. Assessing soil-like materials for ecosystem services provided by constructed technosols. Land 2021, 10, 1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wu, S.; Liu, Y.; Yi, Q.; Nguyen, T.A.H.; Ma, Y.; You, F.; Hall, M.; Chan, T.S.; Huang, Y.; et al. Plant biomass amendment regulates arbuscular mycorrhizal role in organic carbon and nitrogen sequestration in eco-engineered iron ore tailings. Geoderma 2022, 428, 116178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Caliani, J.C.; Fernández-Landero, S.; Giráldez, M.I.; Hidalgo, P.J.; Morales, E. Unveiling a Technosol-based remediation approach for enhancing plant growth in an iron-rich acidic mine soil from the Rio Tinto Mars analog site. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 922, 171217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, Y.M.; Kim, S.C.; Abd El-Azeem, S.A.; Kim, K.H.; Kim, K.R.; Kim, K.; Jeon, C.; Lee, S.S.; Ok, Y.S. Veterinary antibiotics contamination in water, sediment, and soil near a swine manure composting facility. Environ. Earth Sci. 2014, 71, 1433–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Liu, Z.; Hu, B.; Zhu, L. Co-occurrence of crAssphage and antibiotic resistance genes in agricultural soils of the Yangtze River Delta, China. Environ. Int. 2021, 156, 106620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, M.; He, X.; Feng, Y.; Wang, W.; Chen, H.; Gong, M.; Liu, D.; Clarke, J.L.; van Eerde, A. Pollution by antibiotics and antimicrobial resistance in livestock and poultry manure in China, and countermeasures. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, Z.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, Z.; Ding, C.; Wan, L.; Liu, J.; Chen, L.; Wang, X. Pollution characteristics of livestock faeces the key driver of the spread of antibiotic resistance genes. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 409, 124957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, Z.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, Z.; Ding, C.; Zhang, T.; Wan, L.; Wang, X. Antibiotic degradation dominates the removal of antibiotic resistance genes during composting. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 344, 126229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yue, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Ding, C.; Zhang, T.; Kamran, M.; Wan, L.; Wang, X. Key microbial clusters and environmental factors affecting the removal of antibiotics in an engineered anaerobic digestion system. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 348, 126770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, K.; Peng, J.; Li, J.; Yang, Q.; Zhan, X.; Liu, N.; Han, X. Stabilization of soil aggregate organic matter under the application of three organic resources biochar-based compound fertilizer. J. Soils Sediments 2020, 20, 3633–3643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.; Yu, G.; Jiang, R.; Ma, J.; Shang, X.; Wang, G.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Li, C. Moderate sewage sludge biochar application on alkaline soil for corn growth: A field study. Biochar 2021, 3, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, Y.; Meng, J.; Han, X.R.; Chen, W.F. Advances in research on biochar-based products their effects on soil fertility improvement. J. Plant Nutr. Fertil. 2024, 30, 1396–1412. [Google Scholar]

- Ashish, K.; Md Zishan, A.; Rameshwari, A.B.; Raffaele, R.; Lucia De, L.; Antonello, S.; Jitendra Kumar, T. Nanotechnology for Sustainable Biotic Stress Management in Plants. Plant Stress 2025, 18, 101064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felipe Hipolito Dos, S.; Matheus Bortolanza, S.; Luis Reynaldo Ferracciu, A. Pristine Biochar-Supported Nano Zero-Valent Iron to Immobilize As Zn Pb in Soil Contaminated by Smelting Activities. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 321, 116017. [Google Scholar]

- Dharmendra, S.K.; Alok, S. Recent Developments in Surface Modification of Nano Zero-Valent Iron (nzvi): Remediation, Toxicity and Environmental Impacts. Environ. Nanotechnol. Monit. Manag. 2020, 14, 100344. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Ren, J.; Qu, X. Nanozymes: Classification, catalytic mechanisms, activity regulation, and applications. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 4357–4412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Zhang, A.; Wang, R.; Zhang, Q.; Cui, D. A review on metal- and metal oxide-based nanozymes: Properties, mechanisms, and applications. Nano-Micro Lett. 2021, 13, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, H.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, Z.; Wang, Q. Amechanism of microbial sensitivity regulation on interventional remediation by nanozyme manganese oxide in soil heavy metal pollution. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 373, 133825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Uppaluri, R.V.; Mitra, S. A review on waste derived carbon nanozyme: An emerging catalytic material for monitoring and degrading environmental pollutants. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 507, 160762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Fang, Z.; Zheng, L.; Cheng, W.; Tsang, P.E.; Fang, J.; Zhao, D. Remediation of lead contaminated soil by biochar-supported nano-hydroxyapatite. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2016, 132, 224–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Song, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H.; Ge, S. The sorption and short-term immobilization of lead and cadmium by nano-hydroxyapatite/biochar in aqueous solution and soil. Chemosphere 2022, 286, 131810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, L.; Zhou, Y.; Su, Y.; Zhao, P.; Zhang, J.; Fan, W.; Yang, S.; Long, G. Coupling raw material cultivation with nano-hydroxyapatite application to utilize and remediate severely Cd-containing soil. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2024, 184, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Duan, R.; Liang, X.; Liu, H.; Qin, S.; Wang, L.; Fu, H.; Zhao, P.; Li, C. Zinc oxide nanoparticles nano-hydroxyapatite enhanced Cd immobilization activated antioxidant activity improved wheat growth minimized dietary health risks in soil-wheat system. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 113574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Li, H.; Ma, W.; Fu, D.; Han, K.; Wang, H.; He, N.; Li, Q.; Wang, Y. Addition of graphene sheets enhances reductive dissolution of arsenic and iron from arsenic contaminated soil. Land Degrad. Dev. 2018, 29, 572–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Qiu, S.; Xu, X.; Ciampitti, I.A.; Zhang, S.; He, P. Change in straw decomposition rate and soil microbial community composition after straw addition in different long-term fertilization soils. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2019, 138, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nepal, J.; Maltais-Landry, G.; Ahmad, W.; Wright, A.L.; Ogram, A.; Stoffella, P.J.; He, Z. Comparing carbon nanomaterial and biochar as soil amendment in field: Influences on soil biochemical properties in coarse-textured soils. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 2025, 130, 233–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhang, P.; Adeel, M.; Guo, Z.; Chetwynd, A.J.; Ma, C.; Bai, T.; Hao, Y.; Rui, Y. Physiological impacts of zero valent iron, Fe3O4 and Fe2O3 nanoparticles in rice plants and their potential as Fe fertilizers. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 269, 116134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, L. Recent advances in nanoscale zero-valent iron/oxidant system as a treatment for contaminated water and soil. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 106276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Seijo, A.; Soares, C.; Ribeiro, S.; Amil, B.F.; Patinha, C.; Cachada, A.; Fidalgo, F.; Pereira, R. Nano-Fe2O3 as a tool to restore plant growth in contaminated soils–Assessment of potentially toxic elements (bio) availability redox homeostasis in Hordeum vulgare L. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 425, 127999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Quan, X.; Chen, S.; Zhao, H.M.; Liu, Y. Photocatalytic remediation ofγ-hexachlorocyclohexane contaminated soils using TiO2 and montmorillonite composite photocatalyst. J. Environ. Sci. 2007, 19, 358–361. [Google Scholar]

- Asadishad, B.; Chahal, S.; Akbari, A.; Cianciarelli, V.; Azodi, M.; Ghoshal, S.; Tufenkji, N. Amendment of agricultural soil with metal nanoparticles: Effects on soil enzyme activity and microbial community composition. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 1908–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, H.; Kalia, A.; Sandhu, J.S.; Dheri, G.S.; Kaur, G.; Pathania, S. Interaction of TiO2 nanoparticles with soil: Effect on microbiological and chemical traits. Chemosphere 2022, 301, 134629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, H.; Wang, F.; Wu, H.; Qin, Q.; Ma, S.; Chen, H.; Zhou, B.; Yuan, R.; Luo, S.; Sun, K. Biochar nano-hydroxyapatite combined remediation of soil surrounding tailings area: Multi-metal (loid) s fixation soybean rhizosphere soil microbial improvement. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 469, 133817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qie, H.; Ren, M.; You, C.; Cui, X.; Tan, X.; Ning, Y.; Liu, M.; Hou, D.; Lin, A.; Cui, J. High-efficiency control of pesticide heavy metal combined pollution in paddy soil using biochar/g-C3N4 photoresponsive soil remediation agent. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 452, 139579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Zhang, S.; Fu, Q.; Antonietti, M. Conjugation of artificial humic acids with inorganic soil matter to restore land for improved conservation of water and nutrients. Land Degrad. Dev. 2020, 31, 884–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltrá, J.C.; Gabarrón, M.; Faz, Á.; Zornoza, R.; Acosta, J.A.; Martínez-Martínez, S. Nitrogen Assessment in Amended Mining Soils Sown with Coronilla juncea and Piptatherum miliaceum. Minerals 2022, 12, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sammauria, R.; Kumawat, S.; Kumawat, P.; Singh, J.; Jatwa, T.K. Microbial inoculants: Potential tool for sustainability of agricultural production systems. Arch. Microbiol. 2020, 202, 677–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, R.S.; Kaur, N.; Kennedy, J.F. Pullulan production from agro-industrial waste and its applications in food industry: A review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 217, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lian, W.; Shi, W.; Tian, S.; Gong, X.; Yu, Q.; Lu, H.; Liu, Z.; Zheng, J.; Wang, Y.; Bian, R.; et al. Preparation and application of biochar from co-pyrolysis of different feedstocks for immobilization of heavy metals in contaminated soil. Waste Manag. 2023, 163, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sombrero, A.; De Benito, A. Carbon accumulation in soil. Ten-year study of conservation tillage and crop rotation in a semi-arid area of Castile-Leon, Spain. Soil Tillage Res. 2010, 107, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontaine, S.; Hénault, C.; Aamor, A.; Bdioui, N.; Bloor, J.M.G.; Maire, V.; Mary, B.; Revaillot, S.; Maron, P.A. Fungi mediate long term sequestration of carbon and nitrogen in soil through their priming effect. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2011, 43, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Zhu, C.; Li, S.; Huang, J.; Wang, W.; Lian, C.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, S. Impact of ectomycorrhizal symbiosis on root system architecture and nutrient absorption in Chinese chestnut and pecan seedlings. Plant Soil 2025, 513, 2689–2705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egendorf, S.P.; Deeb, M.; Singer, B.; Flores, N.; Prefer, M.; Cheng, Z.; Groffman, P. Carbon and nitrogen cycling in an urban constructed technosol: The artist-led carbon sponge pilot study. Geoderma 2025, 460, 117422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhu, L.; Zhao, F.; Li, J.; Zhang, X.; Kong, X.; Wu, H.; Zhang, Z. Plant salinity stress response and nano-enabled plant salt tolerance. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 843994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, J.M.; Ippolito, J.A.; Watts, D.W.; Sigua, G.C.; Ducey, T.F.; Johnson, M.G. Biochar compost blends facilitate switchgrass growth in mine soils by reducing Cd and Zn bioavailability. Biochar 2019, 1, 97–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebrun, M.; Miard, F.; Nandillon, R.; Scippa, G.S.; Bourgerie, S.; Morabito, D. Biochar effect associated with compost iron to promote Pb As soil stabilization Salix viminalis L. growth. Chemosphere 2019, 222, 810–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.; Huang, X.; Liu, F.; Hu, X.; Zhao, X.; Wang, L.; Gao, P.; Ji, P. A two-year field study of using a new material for remediation of cadmium contaminated paddy soil. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 263, 114614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Huang, Y.; Huang, L.; Huang, Q.; Li, Y.; Li, X.; Yang, S.; Liu, C.; Liu, Z. Combined biochar and soda residues increases maize yields and decreases grain Cd/Pb in a highly Cd/Pb-polluted acid Udults soil. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2021, 306, 107198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Ran, Q.; Li, F.; Shaheen, S.M.; Wang, H.; Rinklebe, J.; Liu, C.; Fang, L. Carbon-based strategy enables sustainable remediation of paddy soils in harmony with carbon neutrality. Carbon Res. 2022, 1, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palansooriya, K.N.; Ok, Y.S.; Awad, Y.M.; Lee, S.S.; Sung, J.K.; Koutsospyros, A.; Moon, D.H. Impacts of biochar application on upland agriculture: A review. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 234, 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Lv, L.; Yu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Wang, B.; Yang, R.; Chen, M.; Wu, P.; Wang, S. Synergistic effect between biochar and sulfidized nano-sized zero-valent iron enhanced cadmium immobilization in a contaminated paddy soil. Biochar 2024, 6, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Espinosa, T.; Papamichael, I.; Voukkali, I.; Gimeno, A.P.; Candel, M.B.A.; Navarro-Pedreño, J.; Zorpas, A.A.; Lucas, I.G. Nitrogen management in farming systems under the use of agricultural wastes and circular economy. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 876, 162666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luna Ramos, L.; Solé Benet, A.; Lázaro Suau, R.; Arzadun Larrucea, A.; Hens del Campo, L.; Urdiales Matilla, A. Field-testing and Characterization of Technosols Made from Industrial and Agricultural Residues for Restoring Degraded Slopes in Semiarid SE Spain. J. Soils Sediments 2021, 21, 1989–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carabassa, V.; Domene, X.; Alcañiz, J.M. Soil restoration using compost-like-outputs digestates from non-source-separated urban waste as organic amendments: Limitations opportunities. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 255, 109909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type | Category | Key Constituent | Effect | Description | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organic matter | Livestock and poultry waste | C, N, P, K. | + |

| [3,18,19] |

| − |

| ||||

| Crop straw | Cellulose, hemicellulose, lignin. | + |

| [10,20,21] | |

| − |

| ||||

| Biochar | C, P, K, Ca, Mg. | + |

| [22,23,24,25] | |

| − |

| ||||

| Inorganic matter | Industrial and construction waste | P, K, Si, Al, Fe. | + |

| [26,27,28,29,30] |

| − |

| ||||

| Mineral waste | Oxides of Ca, Mg, Si, Al, Fe, Mn. | + |

| [14,17,31,32] | |

| − |

| ||||

| Coal gangue and fly ash | P, K, Ca, Mg, Na, S, Fe, Mn, Zn. | + |

| [8,33,34,35] | |

| − |

| ||||

| Waste gypsum | Ca, S. | + |

| [36,37,38,39] | |

| − |

|

| Category | Property | Function | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nanozymes |

|

| [64,65,66,67] |

| Nano-Hydroxyapatite |

|

| [68,69,70,71] |

| Nanocarbon |

|

| [72,73,74] |

| Nanoscale zero-valent iron | Large surface area enables rapid pollutant degradation. |

| [9,75,76,77] |

| Nano-titanium dioxide |

| Photogenerated free radicals degrade soil pollutants (e.g., PAHs, petroleum hydrocarbons) into harmless substances for remediation. | [78,79,80] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ma, X.; Wang, W.; Han, F.; Jiang, B.; Liu, Y.; Geng, Y.; Ma, Y.; Wu, J.; Wu, S. Technosol Construction for Sustainable Agriculture: Research Status and Prospects. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2903. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122903

Ma X, Wang W, Han F, Jiang B, Liu Y, Geng Y, Ma Y, Wu J, Wu S. Technosol Construction for Sustainable Agriculture: Research Status and Prospects. Agronomy. 2025; 15(12):2903. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122903

Chicago/Turabian StyleMa, Xiaochi, Wenyu Wang, Feng Han, Binxian Jiang, Yanbo Liu, Yuhui Geng, Yan Ma, Jinggui Wu, and Shuang Wu. 2025. "Technosol Construction for Sustainable Agriculture: Research Status and Prospects" Agronomy 15, no. 12: 2903. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122903

APA StyleMa, X., Wang, W., Han, F., Jiang, B., Liu, Y., Geng, Y., Ma, Y., Wu, J., & Wu, S. (2025). Technosol Construction for Sustainable Agriculture: Research Status and Prospects. Agronomy, 15(12), 2903. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122903