National-Scale Soil Organic Carbon Change in China’s Paddy Fields: Drivers, Spatial Patterns, and a New Long-Term Estimate (1980–2018)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

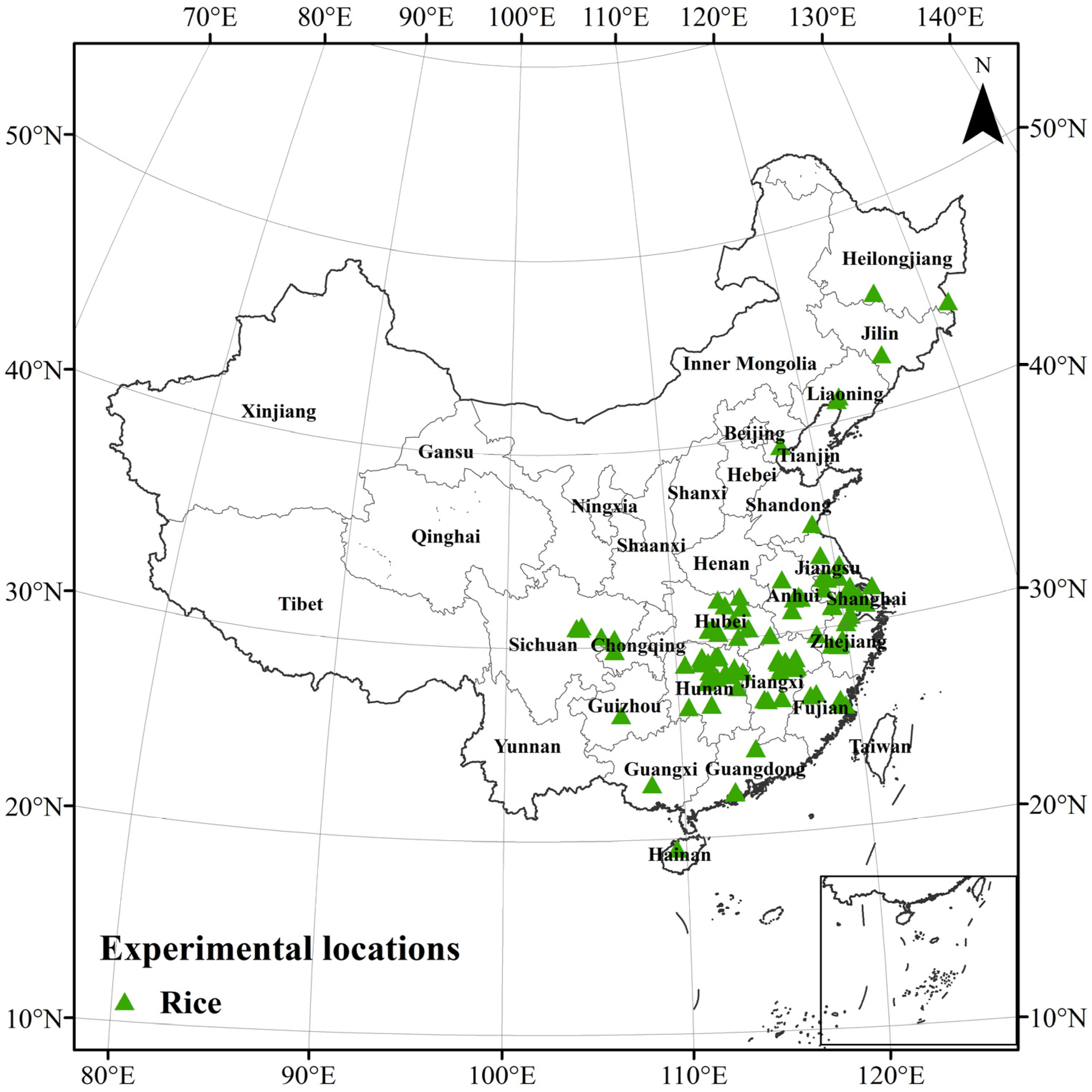

2.1. Data Compilation for Model Development

2.2. Model Development and Statistical Analysis

2.3. National-Scale Model Application

3. Results

3.1. Model Performance and Validation

3.2. Drivers of SOC Change: Relative Importance and Effects

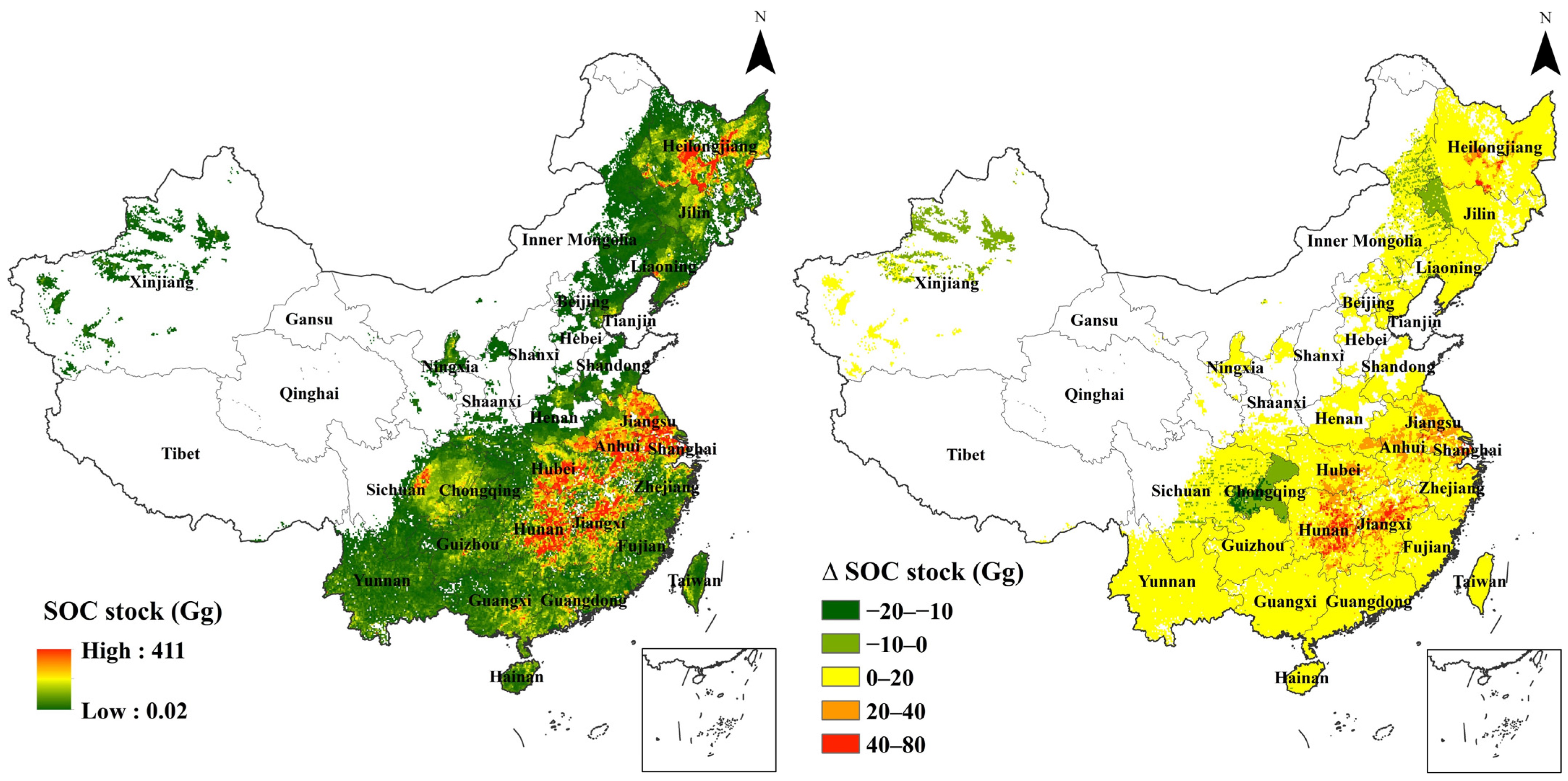

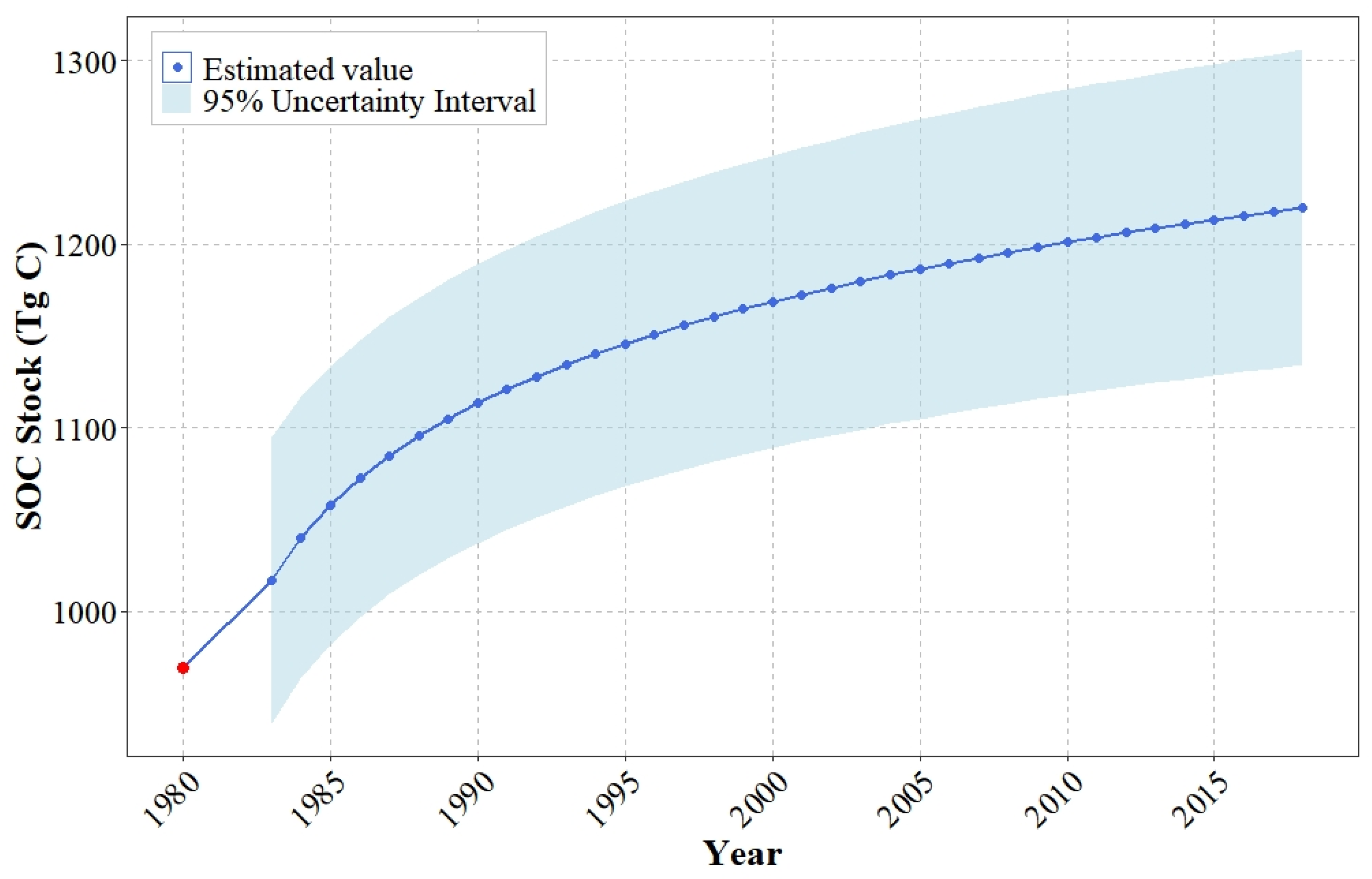

3.3. Spatial Patterns of SOC Change in Chinese Paddy Fields from 1980 to 2018

4. Discussion

4.1. Key Drivers of SOC Sequestration

4.2. Interpreting the Spatial Patterns of SOC Change

4.3. Limitations and Implications of This Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SOC | Soil organic carbon |

| SOCD | Soil organic carbon density |

| BD | Soil bulk density |

| RMSE | Root mean square error |

| EF | Modeling efficiency |

| GHG | Greenhouse gas |

References

- IPCC. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. In Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ussiri, D.A.N.; Lal, R. Carbon Sequestration for Climate Change Mitigation and Food Security; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sanderman, J.; Hengl, T.; Fiske, G.J. Soil carbon debt of 12,000 years of human land use. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 9575–9580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foley, J.A.; Ramankutty, N.; Brauman, K.A.; Cassidy, E.S.; Gerber, J.S.; Johnston, M.; Mueller, N.D.; O’Connell, C.; Ray, D.K.; West, P.C.; et al. Solutions for a cultivated planet. Nature 2011, 478, 337–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paustian, K.; Lehmann, J.; Ogle, S.; Reay, D.; Robertson, G.P.; Smith, P. Climate-smart soils. Nature 2016, 532, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.; Soussana, J.-F.; Angers, D.; Schipper, L.; Chenu, C.; Rasse, D.P.; Batjes, N.H.; van Egmond, F.; McNeill, S.; Kuhnert, M.; et al. How to measure, report and verify soil carbon change to realize the potential of soil carbon sequestration for atmospheric GHG removal. Glob. Change Biol. 2020, 26, 219–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulton, P.; Johnston, J.; Macdonald, A.; White, R.; Powlson, D. Major limitations to achieving “4 per 1000” increases in soil organic carbon stock in temperate regions: Evidence from long-term experiments at Rothamsted Research, United Kingdom. Glob. Change Biol. 2018, 24, 2563–2584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Chapter 5: Cropland. In 2019 Refinement to the 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories: Agriculture, Forestry and Other Land Use; Blain, D., Agus, F., Alfaro, M.A., Vreuls, H., Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 5, p. 68. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, X.Y.; Cai, Z.C.; Wang, S.W.; Smith, P. Direct measurement of soil organic carbon content change in the croplands of China. Glob. Change Biol. 2011, 17, 1487–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.C.; Wang, M.Y.; Hu, S.J.; Zhang, X.D.; Ouyang, Z.; Zhang, G.L.; Huang, B.; Zhao, S.W.; Wu, J.S.; Xie, D.T.; et al. Economics- and policy-driven organic carbon input enhancement dominates soil organic carbon accumulation in Chinese croplands. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 4045–4050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virto, I.; Barré, P.; Burlot, A.; Chenu, C. Carbon input differences as the main factor explaining the variability in soil organic C storage in no-tilled compared to inversion tilled agrosystems. Biogeochemistry 2012, 108, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.S.; Zhuang, Y.H.; Frolking, S.; Galloway, J.; Harriss, R.; Moore, B., III; Schimel, D.; Wang, X.K. Modeling soil organic carbon change in croplands of China. Ecol. Appl. 2003, 13, 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogle, S.M.; Breidt, F.J.; Easter, M.; Williams, S.; Killian, K.; Paustian, K. Scale and uncertainty in modeled soil organic carbon stock changes for US croplands using a process-based model. Glob. Change Biol. 2010, 16, 810–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurung, R.B.; Ogle, S.M.; Breidt, F.J.; Williams, S.A.; Parton, W.J. Bayesian calibration of the DayCent ecosystem model to simulate soil organic carbon dynamics and reduce model uncertainty. Geoderma 2020, 376, 114529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.C.; Huang, Y. Quantification of soil organic carbon sequestration potential in cropland: A model approach. Sci. China Life Sci. 2010, 53, 868–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.F.; Wang, M.H.; Xu, X.R.; Cheng, K.; Yue, Q.; Pan, G.X. Re-estimating methane emissions from Chinese paddy fields based on a regional empirical model and high-spatial-resolution data. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 265, 115017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kögel-Knabner, I.; Amelung, W.; Cao, Z.; Fiedler, S.; Frenzel, P.; Jahn, R.; Kalbitz, K.; Kölbl, A.; Schloter, M. Biogeochemistry of paddy soils. Geoderma 2010, 157, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.L.; Ge, T.D.; Zhu, Z.K.; Liu, S.L.; Luo, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, P.; Gavrichkova, O.; Xu, X.; Wang, J.; et al. Carbon input and allocation by rice into paddy soils: A review. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2019, 133, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Ge, T.D.; Zhu, Z.K.; Ye, R.Z.; Peñuelas, J.; Li, Y.H.; Lynn, T.M.; Jones, D.L.; Wu, J.S.; Kuzyakov, Y. Paddy soils have a much higher microbial biomass content than upland soils: A review of the origin, mechanisms, and drivers. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2022, 326, 107798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, G.H.; Li, L.Q.; Pan, G.X.; Zhang, Q. Topsoil organic carbon storage of China and its loss by cultivation. Biogeochemistry 2005, 74, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, S. Trends in global rice consumption. Rice Today 2013, 12, 44–45. [Google Scholar]

- FAOSTAT. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Available online: http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- FAO; IIASA. Harmonized World Soil Database Version 2.0; FAO: Rome, Italy; IIASA: Laxenburg, Austria, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ruehlmann, J.; Körschens, M. Calculating the effect of soil organic matter concentration on soil bulk density. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2009, 73, 876–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poeplau, C.; Don, A. Sensitivity of soil organic carbon stocks and fractions to different land-use changes across Europe. Geoderma 2013, 192, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiesmeier, M.; Urbanski, L.; Hobley, E.; Lang, B.; von Lützow, M.; Marin-Spiotta, E.; van Wesemael, B.; Rabot, E.; Ließ, M.; Garcia-Franco, N.; et al. Soil organic carbon storage as a key function of soils-A review of drivers and indicators at various scales. Geoderma 2019, 333, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Agricultural Technology Extension Service Center. Chinese Organic Fertilizer Nutrient Manual; China Agriculture Press: Beijing, China, 1999. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Resource and Environment Science and Data Center, Chinese Academy of Sciences. Chinese Meteorological Forcing Dataset. Available online: http://www.resdc.cn (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Yang, Y.H.; Mohammat, A.; Feng, J.M.; Zhou, R.; Fang, J.Y. Storage, patterns and environmental controls of soil organic carbon in China. Biogeochemistry 2007, 84, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuur, A.F.; Ieno, E.N.; Smith, G.M. Analyzing Ecological Data; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, P.; Smith, J.U.; Powlson, D.S.; Mcgill, W.B.; Arah, J.R.M.; Chertov, O.G.; Coleman, K.; Franko, U.; Frolking, S.; Jenkinson, D.S.; et al. A comparison of the performance of nine soil organic matter models using datasets from seven long-term experiments. Geoderma 1997, 81, 153–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monfreda, C.; Ramankutty, N.; Foley, J.A. Farming the planet: 2. Geographic distribution of crop areas, yields, physiological parameters, and net primary production in the year 2000. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2008, 22, GB1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Bureau of Statistics of China (NBS). China Rural Statistical Yearbook 2019; China Statistics Press: Beijing, China, 2019. (In Chinese)

- National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC). China Agricultural Products Cost-Benefit Yearbook 2019; China Statistics Press: Beijing, China, 2019. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Agriculture of the People’s Republic of China. National Crop Straw Resources Survey and Evaluation Report; China Agriculture Press: Beijing, China, 2010. (In Chinese)

- Ministry of Ecology and Environment. Letter of Response to Proposal No. 1326 (Resource and Environment Category No. 094) of the Fourth Session of the 12th National Committee of the CPPCC. 2016. Available online: https://www.mee.gov.cn/gkml/sthjbgw/qt/201610/t20161026_366239_wh.htm (accessed on 3 November 2025). (In Chinese)

- Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs. The 2024 National Straw Comprehensive Utilization On-Site Promotion Meeting Was Held. 2024. Available online: https://kjs.moa.gov.cn/gzdt/202406/t20240614_6457216.htm (accessed on 3 November 2025). (In Chinese)

- Sun, J.F.; Chen, L.B.; Ogle, S.; Cheng, K.; Xu, X.R.; Li, Y.P.; Pan, G.X. Future climate change may pose pressures on greenhouse gas emission reduction in China’s rice production. Geoderma 2023, 440, 116732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, G.X.; Li, L.Q.; Wu, L.S.; Zhang, X.H. Storage and sequestration potential of topsoil organic carbon in China’s paddy soils. Glob. Change Biol. 2004, 10, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkinson, D.S.; Rayner, J.H. The turnover of soil organic matter in some of the Rothamsted classical experiments. Soil Sci. 1977, 123, 298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parton, W.J.; Schimel, D.S.; Cole, C.V.; Ojima, D.S. Analysis of factors controlling soil organic matter levels in Great Plains grasslands. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1987, 51, 1173–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larney, F.J.; Angers, D.A. The role of organic amendments in soil reclamation: A review. Can. J. Soil Sci. 2012, 92, 19–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotrufo, M.F.; Wallenstein, M.D.; Boot, C.M.; Denef, K.; Paul, E.A. The Microbial Efficiency-Matrix Stabilization (MEMS) framework integrates plant litter decomposition with soil organic matter stabilization: Do labile plant inputs form stable soil organic matter? Glob. Change Biol. 2013, 19, 988–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavallee, J.M.; Soong, J.L.; Cotrufo, M.F. Conceptualizing soil organic matter into particulate and mineral-associated forms to address global change in the 21st century. Glob. Change Biol. 2020, 26, 261–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, N.; Zhang, M.M.; Pan, X.P.; Dang, P.F.; Wang, S.G.; Han, X.Q.; Wang, X.F.; Zhang, C.H.; Meng, M.; Wang, W.; et al. Characteristics of Changes to POC and MAOC After Straw Returning in China: A Meta-Analysis. Land Degrad. Dev. 2025, 36, 3537–3550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.X.; Du, M.L.; Chen, J.; Tie, L.H.; Zhou, S.X.; Buckeridge, K.M.; Cornelissen, J.H.C.; Huang, C.; Kuzyakov, Y. Microbial Necromass under Global Change and Implications for Soil Organic Matter. Glob. Change Biol. 2023, 29, 3503–3515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castellano, M.J.; Mueller, K.E.; Olk, D.C.; Sawyer, J.E.; Six, J. Integrating plant litter quality, soil organic matter stabilization, and the carbon saturation concept. Glob. Change Biol. 2015, 21, 3200–3209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fageria, N.K.; Baligar, V.C. Ameliorating soil acidity of tropical Oxisols by liming for sustainable crop production. Adv. Agron. 2008, 99, 345–399. [Google Scholar]

- Malik, A.A.; Puissant, J.; Buckeridge, K.M.; Goodall, T.; Jehmlich, N.; Chowdhury, S.; Gweon, H.S.; Peyton, J.M.; Mason, K.E.; van Agtmaal, M.; et al. Land use driven change in soil pH affects microbial carbon cycling processes. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 3591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, T.O.; Six, J. Considering the influence of sequestration duration and carbon saturation on estimates of soil carbon capacity. Clim. Change 2007, 80, 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommer, R.; Bossio, D. Dynamics and climate change mitigation potential of soil organic carbon sequestration. J. Environ. Manag. 2014, 144, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Z.B.; Zhu, J.G.; Liu, G.; Cadisch, G.; Hasegawa, T.; Chen, C.M.; Sun, H.F.; Tang, H.Y.; Zeng, Q. Soil organic carbon stocks in China and changes from 1980s to 2000s. Glob. Change Biol. 2007, 13, 1989–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.J.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Yu, Y.Q. Carbon sequestration and its potential in agricultural soils of China. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2010, 24, GB3010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poeplau, C.; Don, A.; Vesterdal, L.; Leifeld, J.; van Wesemael, B.; Schumacher, J.; Gensior, A. Temporal dynamics of soil organic carbon after land-use change in the temperate zone–carbon response functions as a model approach. Glob. Change Biol. 2011, 17, 2415–2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Oost, K.; Verstraeten, G.; Doetterl, S.; Notebaert, B.; Wiaux, F.; Broothaerts, N.; Six, J. Legacy of human-induced C erosion and burial on soil–atmosphere C exchange. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 19492–19497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.B.; Huang, H.; Liu, J.X.; Yao, L.; He, H. Recent progress and prospects in the development of ridge tillage cultivation technology in China. Soil Tillage Res. 2014, 142, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Li, T.; Cheng, K.; Pan, G.X. Is the Topsoil Carbon Sequestration Potential Underestimated of Agricultural Soils under Best Management? Soil Tillage Res. 2025, 250, 106528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, R.M.; Roderick, M.L. Soil Carbon Stocks and Bulk Density: Spatial or Cumulative Mass Coordinates as a Basis of Expression? Glob. Change Biol. 2003, 9, 1507–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.R.; Wiesmeier, M.; Conant, R.T.; Kühnel, A.; Sun, Z.G.; Kögel-Knabner, I.; Hou, R.X.; Cong, P.F.; Liang, R.B.; Ouyang, Z. Large soil organic carbon increase due to improved agronomic management in the North China Plain from 1980s to 2010s. Glob. Change Biol. 2018, 24, 987–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guilpart, N.; Iizumi, T.; Makowski, D. Data-driven projections suggest large opportunities to improve Europe’s soybean self-sufficiency under climate change. Nat. Food 2022, 3, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samarinas, N.; Tsakiridis, N.L.; Kokkas, S.; Kalopesa, E.; Zalidis, G.C. Soil Data Cube and Artificial Intelligence Techniques for Generating National-Scale Topsoil Thematic Maps: A Case Study in Lithuanian Croplands. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 5304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogle, S.M.; Breidt, F.J.; Easter, M.; Williams, S.; Paustian, K. An empirically based approach for estimating uncertainty associated with modelling carbon sequestration in soils. Ecol. Model. 2007, 205, 453–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadwick, D.; Jia, W.; Tong, Y.A.; Yu, G.H.; Shen, Q.R.; Chen, Q. Improving manure nutrient management towards sustainable agricultural intensification in China. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2015, 209, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks Pries, C.E.; Castanha, C.; Porras, R.C.; Torn, M.S. The whole-soil carbon flux in response to warming. Science 2017, 355, 1420–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaiser, K.; Kalbitz, K. Cycling downwards–dissolved organic matter in soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2012, 52, 29–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolan, N.S.; Adriano, D.C.; Kunhikrishnan, A.; James, T.; McDowell, R.; Senesi, N. Dissolved organic matter: Biogeochemistry, dynamics, and environmental significance in soils. Adv. Agron. 2011, 110, 1–75. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Df | Sum of Squares | Mean Square | F-Value | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Latitude | 4 | 496.10 | 124.03 | 13.43 | <0.001 | *** |

| Longitude | 4 | 309.50 | 77.37 | 8.38 | <0.001 | *** |

| Mineral Nitrogen inputs | 1 | 60.80 | 60.84 | 6.59 | 0.011 | * |

| Straw carbon input | 1 | 76.80 | 76.77 | 8.32 | 0.004 | ** |

| Livestock manure carbon input | 1 | 1586.90 | 1586.89 | 171.89 | <0.001 | *** |

| Green manure input | 1 | 158.70 | 158.66 | 17.19 | <0.001 | *** |

| Initial SOC content | 1 | 132.10 | 132.10 | 14.31 | <0.001 | *** |

| pH | 7 | 501.70 | 71.68 | 7.76 | <0.001 | *** |

| Experimental duration | 1 | 444.80 | 444.85 | 48.18 | <0.001 | *** |

| Residuals | 496 | 4579.20 | 9.23 | |||

| Total | 521 | 8346.60 | ||||

| Estimate | Standard Error | p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −4.4236872 | 1.4297853 | 0.002 | ** |

| Mineral Nitrogen inputs (kg N ha−1) | 0.0043223 | 0.0009689 | <0.001 | *** |

| Initial SOC content (g kg−1) | −0.1221477 | 0.0295165 | <0.001 | *** |

| Ln (Experimental duration) | 0.1241022 | 0.0168418 | <0.001 | *** |

| Ln (1 + Straw carbon input) | 0.665608 | 0.11873 | <0.001 | *** |

| Ln (1 + Green manure input) | 0.8283698 | 0.1450942 | <0.001 | *** |

| Ln (1 + Livestock manure carbon input) | 1.7305887 | 0.1519914 | <0.001 | *** |

| Latitude | ||||

| LA1 (<25°) | 0 | |||

| LA2 (25–28°) | 2.9976226 | 1.1770912 | 0.011 | * |

| LA3 (28–32°) | 1.0037782 | 1.1105605 | 0.367 | |

| LA4 (32–40°) | 3.1426507 | 1.2409192 | 0.012 | * |

| LA5 (>40°) | −1.5274348 | 1.6954189 | 0.368 | |

| Longitude | ||||

| LO1 (<109°) | 0 | |||

| LO2 (109–114°) | 2.4762039 | 0.5237664 | <0.001 | *** |

| LO3 (114–117°) | 0.9068045 | 0.5467711 | 0.098 | . |

| LO4 (117–124°) | 1.3185247 | 0.5395201 | 0.015 | * |

| LO5 (>124°) | 5.7829866 | 1.6048535 | <0.001 | *** |

| pH | ||||

| <5 | 0 | |||

| 5–5.5 | 2.8834086 | 0.7569134 | <0.001 | *** |

| 5.5–6 | 1.7153829 | 0.7512487 | 0.023 | * |

| 6–6.5 | 2.4611542 | 0.7383296 | <0.001 | *** |

| 6.5–7 | 3.1201699 | 0.7651897 | <0.001 | *** |

| 7–7.5 | 5.1103674 | 0.9210038 | <0.001 | *** |

| 7.5–8 | 3.0373235 | 0.8689575 | <0.001 | *** |

| >8 | 2.6302811 | 1.0119667 | 0.010 | ** |

| Province | Rice Cultivation Area (ha) | SOC (g kg−1) | ΔSOC (g kg−1) | ∆SOC Density (t C ha−1) | SOC Density Changes (%) | ∆SOC Stock (Tg) | SOC Stock (Tg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beijing | 170 | 1.55 ± 0.17 | 0.65 ± 0.17 | 1.28 ± 0.34 | 54.68 ± 14.35 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 |

| Shanxi | 800 | 17.56 ± 1.21 | 6.08 ± 1.21 | 12.08 ± 2.46 | 43.65 ± 8.89 | 0.01 ± 0.00 | 0.03 ± 0.00 |

| Tibet | 940 | 11.97 ± 0.93 | 2.14 ± 0.93 | 4.34 ± 1.89 | 18.94 ± 8.25 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.03 ± 0.00 |

| Gansu | 3820 | 13.22 ± 1.23 | 2.93 ± 1.23 | 5.79 ± 2.45 | 23.32 ± 9.85 | 0.02 ± 0.01 | 0.12 ± 0.01 |

| Tianjin | 39,900 | 21.15 ± 1.65 | 7.49 ± 1.65 | 14.83 ± 3.29 | 43.95 ± 9.75 | 0.59 ± 0.13 | 1.94 ± 0.13 |

| Ningxia | 78,010 | 18.53 ± 1.88 | 4.58 ± 1.88 | 9.10 ± 3.72 | 26.61 ± 10.89 | 0.71 ± 0.29 | 3.38 ± 0.29 |

| Xinjiang | 78,390 | 16.33 ± 2.59 | 1.07 ± 2.59 | 2.13 ± 5.12 | 5.80 ± 13.98 | 0.17 ± 0.40 | 3.04 ± 0.40 |

| Hebei | 78,430 | 18.95 ± 1.78 | 6.20 ± 1.78 | 12.28 ± 3.53 | 38.83 ± 11.18 | 0.96 ± 0.28 | 3.44 ± 0.28 |

| Shanghai | 103,580 | 28.28 ± 1.50 | 8.32 ± 1.50 | 16.44 ± 3.03 | 34.37 ± 6.34 | 1.70 ± 0.31 | 6.66 ± 0.31 |

| Shaanxi | 105,390 | 20.23 ± 1.77 | 5.56 ± 1.77 | 10.99 ± 3.54 | 30.91 ± 9.94 | 1.16 ± 0.37 | 4.91 ± 0.37 |

| Shandong | 113,830 | 20.90 ± 1.46 | 6.59 ± 1.46 | 13.10 ± 2.94 | 38.02 ± 8.54 | 1.49 ± 0.33 | 5.41 ± 0.33 |

| Hainan | 123,050 | 23.52 ± 2.44 | 3.83 ± 2.44 | 7.71 ± 5.00 | 17.03 ± 11.04 | 0.95 ± 0.61 | 6.52 ± 0.61 |

| Taiwan | 135,753 | 20.84 ± 2.51 | 4.06 ± 2.51 | 8.16 ± 5.08 | 20.69 ± 12.88 | 1.11 ± 0.69 | 6.46 ± 0.69 |

| Inner Mongolia | 150,450 | 15.73 ± 2.21 | 0.83 ± 2.21 | 1.63 ± 4.41 | 4.67 ± 12.63 | 0.25 ± 0.66 | 5.50 ± 0.66 |

| Fujian | 441,160 | 23.72 ± 1.78 | 6.92 ± 1.78 | 13.98 ± 3.62 | 35.37 ± 9.16 | 6.17 ± 1.60 | 23.61 ± 1.60 |

| Liaoning | 488,360 | 16.46 ± 2.47 | 2.53 ± 2.47 | 5.03 ± 4.89 | 14.80 ± 14.40 | 2.46 ± 2.39 | 19.05 ± 2.39 |

| Zhejiang | 553,005 | 22.47 ± 1.28 | 8.10 ± 1.28 | 16.14 ± 2.59 | 46.47 ± 7.46 | 8.92 ± 1.43 | 28.13 ± 1.43 |

| Henan | 620,410 | 21.26 ± 1.44 | 6.30 ± 1.44 | 12.48 ± 2.91 | 34.75 ± 8.09 | 7.74 ± 1.80 | 30.03 ± 1.80 |

| Chongqing | 656,450 | 10.88 ± 1.93 | −4.63 ± 1.93 | −9.26 ± 3.90 | −24.80 ± 10.45 | −6.08 ± 2.56 | 18.43 ± 2.56 |

| Guizhou | 671,780 | 21.71 ± 1.71 | 5.10 ± 1.71 | 10.36 ± 3.46 | 26.45 ± 8.83 | 6.96 ± 2.32 | 33.27 ± 2.32 |

| Yunnan | 815,015 | 20.59 ± 2.39 | 4.07 ± 2.39 | 8.20 ± 4.83 | 21.02 ± 12.38 | 6.68 ± 3.94 | 38.47 ± 3.94 |

| Jilin | 839,710 | 20.13 ± 1.89 | 3.24 ± 1.89 | 6.41 ± 3.80 | 16.16 ± 9.59 | 5.38 ± 3.19 | 38.68 ± 3.19 |

| Guangdong | 893,695 | 20.88 ± 2.55 | 2.96 ± 2.55 | 5.94 ± 5.16 | 14.23 ± 12.34 | 5.31 ± 4.61 | 42.64 ± 4.61 |

| Guangxi | 944,045 | 21.68 ± 2.39 | 4.58 ± 2.39 | 9.22 ± 4.85 | 23.05 ± 12.13 | 8.71 ± 4.58 | 46.48 ± 4.58 |

| Sichuan | 1,874,000 | 15.29 ± 1.50 | 0.59 ± 1.50 | 1.17 ± 2.96 | 3.29 ± 8.37 | 2.18 ± 5.55 | 68.58 ± 5.55 |

| Jiangxi | 2,173,000 | 23.33 ± 1.54 | 7.83 ± 1.54 | 15.82 ± 3.13 | 42.69 ± 8.44 | 34.38 ± 6.79 | 114.91 ± 6.79 |

| Hubei | 2,212,650 | 20.43 ± 1.16 | 5.36 ± 1.16 | 10.57 ± 2.32 | 29.11 ± 6.39 | 23.39 ± 5.13 | 103.74 ± 5.13 |

| Jiangsu | 2,214,720 | 21.05 ± 1.51 | 5.31 ± 1.51 | 10.50 ± 3.03 | 27.77 ± 8.01 | 23.24 ± 6.70 | 106.94 ± 6.70 |

| Anhui | 2,358,780 | 19.56 ± 1.31 | 4.44 ± 1.31 | 8.76 ± 2.62 | 24.14 ± 7.22 | 20.66 ± 6.18 | 106.25 ± 6.18 |

| Hunan | 2,740,750 | 24.46 ± 1.38 | 8.78 ± 1.38 | 17.73 ± 2.83 | 47.57 ± 7.59 | 48.60 ± 7.75 | 150.77 ± 7.75 |

| Heilongjiang | 3,783,100 | 23.74 ± 1.97 | 4.82 ± 1.97 | 9.67 ± 4.01 | 21.98 ± 9.10 | 36.59 ± 15.15 | 203.07 ± 15.15 |

| Sum | 25,293,143 | 21.11 ± 1.68 | 4.95 ± 1.68 | 9.90 ± 3.39 | 25.82 ± 8.84 | 242.51 ± 85.80 | 1220.48 ± 85.80 |

| Method | Time Period | Stock Change (Tg yr−1) | Annual Stock Change Rate (%) | Literature |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Literature survey | 1980–2000 | 5.08 | 0.62 | [52] |

| Literature survey | 1980–2002 | 10.26 | 1.22 | [39] |

| Literature survey | 1980–2000 | 4.1 | / | [53] |

| Direct measurement | 1980–2007 | / | 0.28 | [9] |

| Literature survey and Model simulation | 1980–2018 | 1980–2000: 10.31 | 1980–2000: 0.88 | This study |

| 1980–2002: 9.83 | 1980–2002: 0.83 | |||

| 1980–2007: 8.57 | 1980–2007: 0.72 | |||

| 1980–2018: 6.65 | 1980–2018: 0.54 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sun, J.; Jie, X.; Chen, S.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Xiong, L.; Liu, C.; Huang, Y.; Chen, M.; et al. National-Scale Soil Organic Carbon Change in China’s Paddy Fields: Drivers, Spatial Patterns, and a New Long-Term Estimate (1980–2018). Agronomy 2025, 15, 2901. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122901

Sun J, Jie X, Chen S, Zhang P, Zhang J, Li Y, Xiong L, Liu C, Huang Y, Chen M, et al. National-Scale Soil Organic Carbon Change in China’s Paddy Fields: Drivers, Spatial Patterns, and a New Long-Term Estimate (1980–2018). Agronomy. 2025; 15(12):2901. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122901

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Jianfei, Xiaoting Jie, Sujuan Chen, Peiyu Zhang, Jibing Zhang, Yunpeng Li, Li Xiong, Cheng Liu, Yanqiu Huang, Mei Chen, and et al. 2025. "National-Scale Soil Organic Carbon Change in China’s Paddy Fields: Drivers, Spatial Patterns, and a New Long-Term Estimate (1980–2018)" Agronomy 15, no. 12: 2901. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122901

APA StyleSun, J., Jie, X., Chen, S., Zhang, P., Zhang, J., Li, Y., Xiong, L., Liu, C., Huang, Y., Chen, M., Zhang, L., & Zeng, Y. (2025). National-Scale Soil Organic Carbon Change in China’s Paddy Fields: Drivers, Spatial Patterns, and a New Long-Term Estimate (1980–2018). Agronomy, 15(12), 2901. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122901