Fine Mapping of Phytophthora sojae PNJ1 Resistance Locus Rps15 in Soybean (Glycine max (L.) Merr.)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials

2.2. P. sojae Isolates

2.3. Evaluation of Genetic Materials for Phytophthora Resistance

2.4. Data Analysis and Candidate Gene Prediction

2.5. Identification of Molecular Markers

2.6. Expression Analysis of Candidate Genes

3. Results

3.1. Phenotype Reaction of the Parents to P. sojae Isolates

3.2. Genetic Analysis of Resistance to P. sojae Isolate PNJ1 in the Guizao 1 × B13 (GB) Population

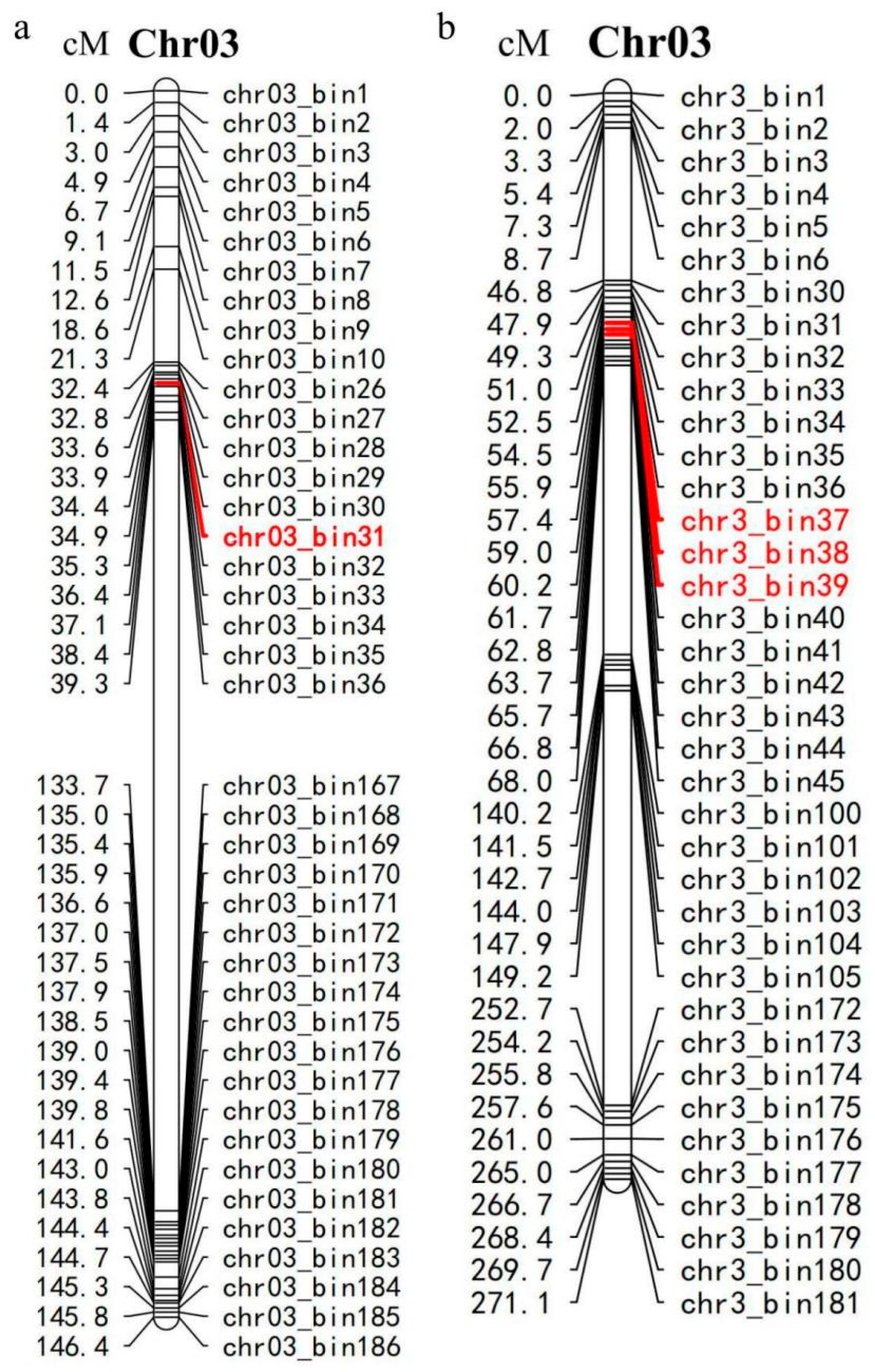

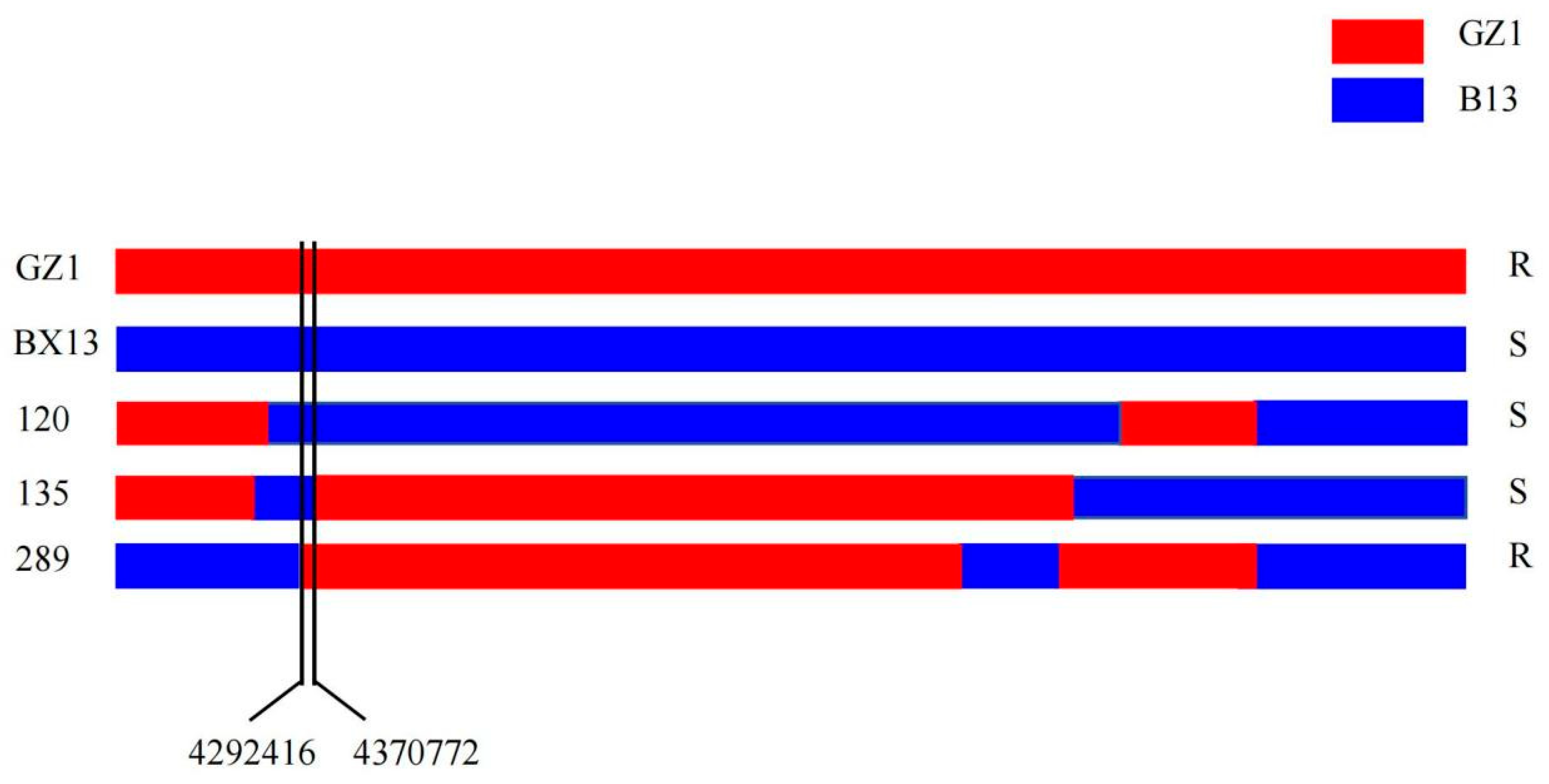

3.3. Fine Mapping of Rps15 by High-Throughput Genome-Wide Resequencing

3.4. Identification of SSR Molecular Markers

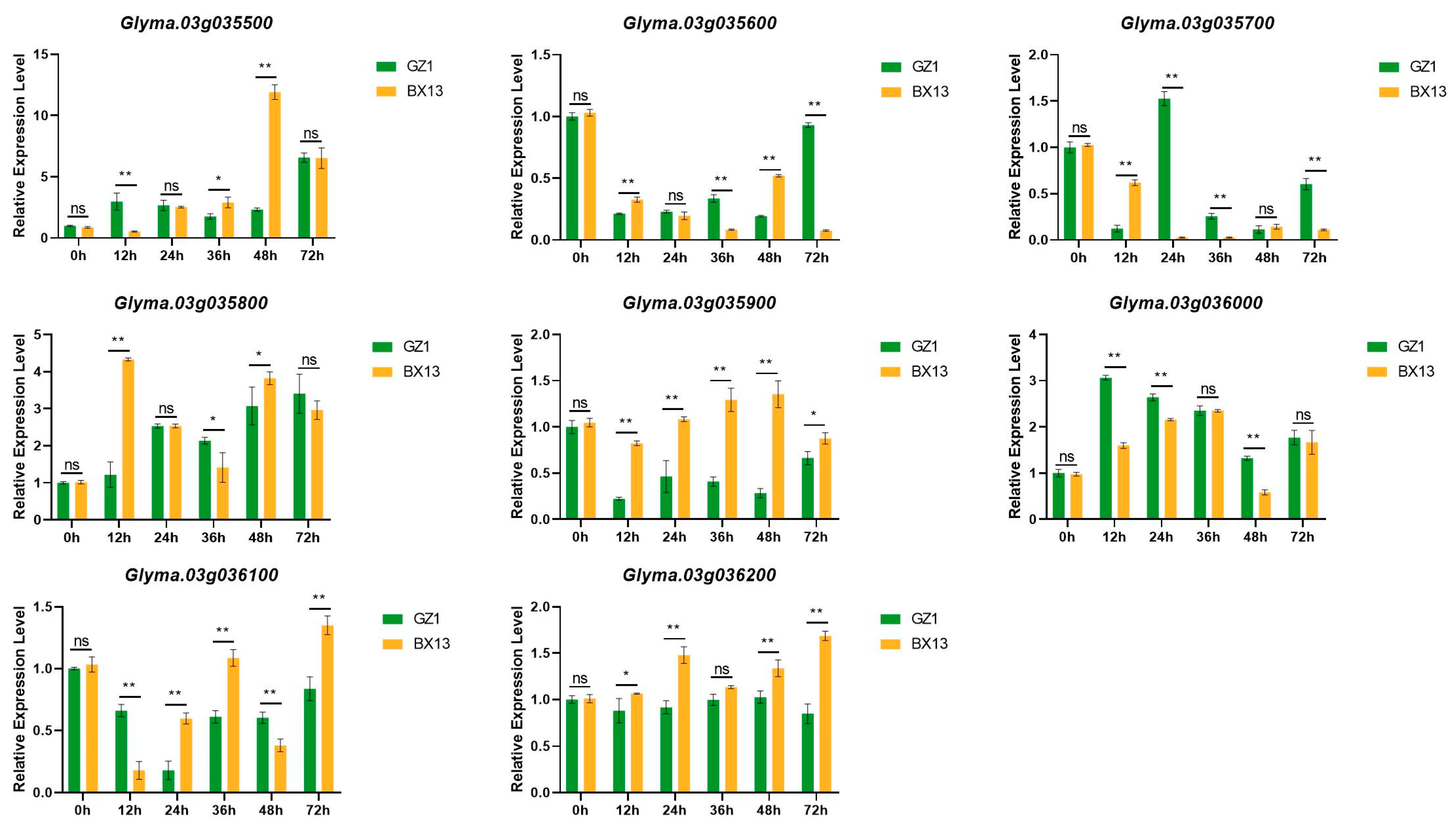

3.5. Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR) Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Comparison Between Rps15 and Other Reported Rps Genes on Chromosome 3

4.2. The Selection of Potential Rps Genes

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hao, Q.; Yang, H.; Chen, S.; Zhang, C.; Chen, L.; Cao, D.; Yuan, S.; Guo, W.; Yang, Z.; Huang, Y.; et al. An pair of an atypical NLR encoding genes confer Asian soybean rust resistance in soybean. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 3310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, C.; Li, Y.H.; Li, D.; Zhang, X.; Kong, L.; Zhou, Y.; Lyu, X.; Ji, R.; Wei, X.; Cheng, Q.; et al. PH13 improves soybean shade traits and enhances yield for high-density planting at high latitudes. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 6813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Chen, L.; Fengler, K.; Bolar, J.; Llaca, V.; Wang, X.; Clark, C.B.; Fleury, T.J.; Myrvold, J.; Oneal, D.; et al. A giant NLR gene confers broad-spectrum resistance to Phytophthora sojae in soybean. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 6263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, B.; Cheng, Y.; Cai, Z.; Li, M.; Jiang, Z.; Ma, R.; Yuan, Y.; Xia, Q.; Nian, H. Fine mapping of a Phytophthora-resistance locus RpsGZ in soybean using genotyping-by-sequencing. BMC Genom. 2020, 21, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; Li, L.; Zhao, J.; Huang, J.; Yan, Q.; Xing, H.; Guo, N. Genetic analysis and fine mapping of RpsJS, a novel resistance gene to Phytophthora sojae in soybean [Glycine max (L.) Merr]. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2014, 127, 913–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Xia, C.; Wang, X.; Duan, C.; Sun, S.; Wu, X.; Zhu, Z. Genetic characterization and fine mapping of the novel Phytophthora resistance gene in a Chinese soybean cultivar. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2013, 126, 1555–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugimoto, T.; Kato, M.; Yoshida, S.; Matsumoto, I.; Kobayashi, T.; Kaga, A.; Hajika, M.; Yamamoto, R.; Watanabe, K.; Aino, M.; et al. Pathogenic diversity of Phytophthora sojae and breeding strategies to develop Phytophthora-resistant soybeans. Breed. Sci. 2012, 61, 511–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorrance, A.E.; McClure, S.A.; St. Martin, S.K. Effect of Partial Resistance on Phytophthora Stem Rot Incidence and Yield of Soybean in Ohio. Plant Dis. 2003, 87, 308–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clevinger, E.M.; Biyashev, R.; Schmidt, C.; Song, Q.; Robertson, A.E.; Dorrance, A.E.; Maroof, M.A.S. Mapping of Phytophthora sojae resistance in soybean genotypes PI 399079 and PI 408132. Crop Sci. 2025, 65, e70027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, F.; Salman, M.; Zhang, Z.; McCoy, A.G.; Li, W.; Magar, R.T.; Mitchell, D.; Zhao, M.; Gu, C.; Chilvers, M.I.; et al. Identification and molecular mapping of a major gene conferring resistance to Phytophthora sansomeana in soybean ‘Colfax’. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2024, 137, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, H.J.; Jang, I.H.; Moon, J.K.; Kang, I.J.; Kim, J.M.; Kang, S.; Lee, S. Genetic dissection of resistance to Phytophthora sojae using genome-wide association and linkage analysis in soybean [Glycine max (L.) Merr.]. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2024, 137, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clevinger, E.M.; Biyashev, R.; Schmidt, C.; Song, Q.; Batnini, A.; Bolanos-Carriel, C.; Robertson, A.E.; Dorrance, A.E.; Saghai Maroof, M.A. Comparison of Rps loci toward isolates, singly and combined inocula, of Phytophthora sojae in soybean PI 407985, PI 408029, PI 408097, and PI424477. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1394676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahoo, D.K.; Das, A.; Huang, X.; Cianzio, S.; Bhattacharyya, M.K. Tightly linked Rps12 and Rps13 genes provide broad-spectrum Phytophthora resistance in soybean. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 16907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Wang, W.; Ping, J.; Fitzgerald, J.C.; Cai, G.; Clark, C.B.; Aggarwal, R.; Ma, J. Identification and molecular mapping of Rps14, a gene conferring broad-spectrum resistance to Phytophthora sojae in soybean. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2021, 134, 3863–3872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, C.; Li, Y.; Sun, S.; Duan, C.; Zhu, Z. Genetic Mapping and Molecular Characterization of a Broad-spectrum Phytophthora sojae Resistance Gene in Chinese Soybean. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, C.; Sun, S.; Li, Y.; Duan, C.; Zhu, Z. Next-generation sequencing to identify candidate genes and develop diagnostic markers for a novel Phytophthora resistance gene, RpsHC18, in soybean. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2018, 131, 525–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, C.; Sun, S.; Yao, L.; Ding, J.; Duan, C.; Zhu, Z. Fine Mapping and Identification of a Novel Phytophthora Root Rot Resistance Locus RpsZS18 on Chromosome 2 in Soybean. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Y.; Ma, Q.; Ren, H.; Xia, Q.; Song, E.; Tan, Z.; Li, S.; Zhang, G.; Nian, H. Fine mapping of a Phytophthora-resistance gene RpsWY in soybean (Glycine max L.) by high-throughput genome-wide sequencing. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2017, 130, 1041–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Sun, S.; Zhong, C.; Wang, X.; Wu, X.; Zhu, Z. Genetic mapping and development of co-segregating markers of RpsQ, which provides resistance to Phytophthora sojae in soybean. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2017, 130, 1223–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Hao, J.; Yuan, J.; Song, Q.; Hyten, D.L.; Cregan, P.B.; Zhang, G.; Gu, C.; Li, M.; Wang, D. Phytophthora Root Rot Resistance in Soybean E00003. Crop Sci. 2014, 54, 492–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, F.; Zhao, M.; Ping, J.; Johnson, A.; Zhang, B.; Abney, T.S.; Hughes, T.J.; Ma, J. Molecular mapping of two genes conferring resistance to Phytophthora sojae in a soybean landrace PI 567139B. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2013, 126, 2177–2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.L.; Zhang, B.Q.; Sun, S.; Zhao, J.M.; Yang, F.; Guo, N.; Gai, J.Y.; Xing, H. Identification, Genetic Analysis and Mapping of Resistance to Phytophthora sojae of Pm28 in Soybean. Agric. Sci. China 2011, 10, 1506–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Wu, X.L.; Zhao, J.M.; Wang, Y.C.; Tang, Q.H.; Yu, D.Y.; Gai, J.Y.; Xing, H. Characterization and mapping of RpsYu25, a novel resistance gene to Phytophthora sojae. Plant Breed. 2011, 130, 139–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugimoto, T.; Yoshida, S.; Biggs, A.R.; Ishimoto, M.; Kaga, A.; Hajika, M.; Watanabe, K.; Aino, M.; Tatsuda, K.; Yamamoto, R.; et al. Genetic analysis and identification of DNA markers linked to a novel Phytophthora sojae resistance gene in the Japanese soybean cultivar Waseshiroge. Euphytica 2011, 182, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan AiYing, W.X.F.X. Molecular identification of Phytophthora resistance gene in soybean cultivar Yudou 25. Acta Agron. Sin. 2009, 35, 1844–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Bhattacharyya, M.K. The soybean-Phytophthora resistance locus Rps1-k encompasses coiled coil-nucleotide binding-leucine rich repeat-like genes and repetitive sequences. BMC Plant Biol. 2008, 8, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugimoto, T.; Yoshida, S.; Watanabe, K.; Aino, M.; Kanto, T.; Maekawa, K.; Irie, K. Identification of SSR markers linked to the Phytophthora resistance gene Rps1-d in soybean. Plant Breed. 2008, 127, 154–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Narayanan, N.N.; Ellison, L.; Bhattacharyya, M.K. Two classes of highly similar coiled coil-nucleotide binding-leucine rich repeat genes isolated from the Rps1-k locus encode Phytophthora resistance in soybean. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2005, 18, 1035–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, C.; Yu, K.; Anderson, T.R.; Poysa, V. Mapping genes conferring resistance to Phytophthora root rot of soybean, Rps1a and Rps7. J. Hered. 2001, 92, 442–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernard, R.L.; Smith, P.E.; Kaufmann, M.J.; Schmitthenner, A.F. Inheritance of resistance to Phytophthora root and stem rot in the soybean. Agron. J. 1957, 49, 3391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, A.L.; Xu, P.F.; Wang, J.S.; Zhang, S.Z.; Wu, J.J.; Li, W.; Chen, W.Y.; Li, N.H.; Fan, S.J.; Wang, X.; et al. Genetic analysis and SSR mapping of gene resistance to Phytophthora sojae race 1 in soybean cv Suinong 10. Chin. J. Oil Crop Sci. 2010, 32, 462–466. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, S.G.; St Martin, S.K.; Dorrance, A.E. Rps8 maps to a resistance gene rich region on soybean molecular linkage group F. Crop Sci. 2006, 46, 168–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnham, K.D.; Dorrance, A.E.; Francis, D.M.; Fioritto, R.J.; St. Martin, S.K. Rps8, A New Locus in Soybean for Resistance to Phytophthora sojae. Crop Sci. 2003, 43, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirbas, A.; Rector, B.G.; Lohnes, D.G.; Fioritto, R.J.; Graef, G.L.; Cregan, P.B.; Shoemaker, R.C.; Specht, J.E. Simple Sequence Repeat Markers Linked to the Soybean Rps Genes for Phytophthora Resistance. Crop Sci. 2001, 41, 1220–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, D.K.; Abeysekara, N.S.; Cianzio, S.R.; Robertson, A.E.; Bhattacharyya, M.K. A Novel Phytophthora sojae Resistance Rps12 Gene Mapped to a Genomic Region That Contains Several Rps Genes. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e169950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ping, J.; Fitzgerald, J.C.; Zhang, C.; Lin, F.; Bai, Y.; Wang, D.; Aggarwal, R.; Rehman, M.; Crasta, O.; Ma, J. Identification and molecular mapping of Rps11, a novel gene conferring resistance to Phytophthora sojae in soybean. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2016, 129, 445–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.; Wang, X.; Wu, X.; Xiao, Y.; Zhu, Z. Molecular Mapping of Phytophthora Resistance Gene in Soybean Cultivar Zaoshu18. J. Plant Genet. Resour. 2010, 11, 213–217. [Google Scholar]

- de Ronne, M.; Santhanam, P.; Cinget, B.; Labbe, C.; Lebreton, A.; Ye, H.; Vuong, T.D.; Hu, H.; Valliyodan, B.; Edwards, D.; et al. Mapping of partial resistance to Phytophthora sojae in soybean PIs using whole-genome sequencing reveals a major QTL. Plant Genome 2022, 15, e20184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elshire, R.J.; Glaubitz, J.C.; Sun, Q.; Poland, J.A.; Kawamoto, K.; Buckler, E.S.; Mitchell, S.E. A robust, simple genotyping-by-sequencing (GBS) approach for high diversity species. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e19379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.R.; Dunham, J.P.; Amores, A.; Cresko, W.A.; Johnson, E.A. Rapid and cost-effective polymorphism identification and genotyping using restriction site associated DNA (RAD) markers. Genome Res. 2007, 17, 240–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Meyer, E.; McKay, J.K.; Matz, M.V. 2b-RAD: A simple and flexible method for genome-wide genotyping. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 808–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, G.J.; Markell, S.G.; Song, Q.J.; Qi, L.L. Genotyping-by-sequencing targeting of a novel downy mildew resistance gene Pl (20) from wild Helianthus argophyllus for sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.). Theor. Appl. Genet. 2017, 130, 1519–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Chao, J.; Cheng, X.; Wang, R.; Sun, B.; Wang, H.; Luo, S.; Xu, X.; Wu, T.; Li, Y. Mapping of a Novel Race Specific Resistance Gene to Phytophthora Root Rot of Pepper (Capsicum annuum) Using Bulked Segregant Analysis Combined with Specific Length Amplified Fragment Sequencing Strategy. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e151401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Han, Y.; Li, Y.; Liu, D.; Sun, M.; Zhao, Y.; Lv, C.; Li, D.; Yang, Z.; Huang, L.; et al. Loci and candidate gene identification for resistance to Sclerotinia sclerotiorum in soybean (Glycine max L. Merr.) via association and linkage maps. Plant J. 2015, 82, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; Wang, Y.; Chen, M.S.; Edae, E.; Poland, J.; Akhunov, E.; Chao, S.; Bai, G.; Carver, B.F.; Yan, L. Precisely mapping a major gene conferring resistance to Hessian fly in bread wheat using genotyping-by-sequencing. BMC Genom. 2015, 16, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Niu, J.; Guo, N.; Sun, J.; Li, L.; Cao, Y.; Li, S.; Huang, J.; Zhao, J.; Zhao, T.; Xing, H. Fine Mapping of a Resistance Gene RpsHN that Controls Phytophthora sojae Using Recombinant Inbred Lines and Secondary Populations. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandhu, D.; Gao, H.; Cianzio, S.; Bhattacharyya, M.K. Deletion of a disease resistance nucleotide-binding-site leucine-rich- repeat-like sequence is associated with the loss of the Phytophthora resistance gene Rps4 in soybean. Genetics 2004, 168, 2157–2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Cheng, Y.; Ma, Z.; Liu, X.; Ma, Q.; Xia, Q.; Zhang, G.; Mu, Y.; Nian, H. Fine-mapping of QTLs for individual and total isoflavone content in soybean (Glycine max L.) using a high-density genetic map. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2018, 131, 555–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.J.; Sugano, S.; Kaga, A.; Lee, S.S.; Sugimoto, T.; Takahashi, M.; Ishimoto, M. Evaluation of Resistance to Phytophthora sojae in Soybean Mini Core Collections Using an Improved Assay System. Phytopathology 2017, 107, 216–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Guo, N.; Li, Y.; Sun, J.; Hu, G.; Zhang, H.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, J.; Xing, H.; et al. Phenotypic evaluation and genetic dissection of resistance to Phytophthora sojae in the Chinese soybean mini core collection. BMC Genet. 2016, 17, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Sun, S.; Wang, G.; Duan, C.; Wang, X.; Wu, X.; Zhu, Z. Characterization of Phytophthora resistance in soybean cultivars/lines bred in Henan province. Euphytica 2014, 196, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyle, D.E.; Nickell, C.D.; Nelson, R.L.; Pedersen, W.L. Response of Soybean Accessions from Provinces in Southern China to Phytophthora sojae. Plant Dis. 1998, 82, 555–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Z.Q.; Xue, J.Y.; Wu, P.; Zhang, Y.M.; Wu, Y.; Hang, Y.Y.; Wang, B.; Chen, J.Q. Large-Scale Analyses of Angiosperm Nucleotide-Binding Site-Leucine-Rich Repeat Genes Reveal Three Anciently Diverged Classes with Distinct Evolutionary Patterns. Plant Physiol. 2016, 170, 2095–2109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Z.Q.; Zhang, Y.M.; Hang, Y.Y.; Xue, J.Y.; Zhou, G.C.; Wu, P.; Wu, X.Y.; Wu, X.Z.; Wang, Q.; Wang, B.; et al. Long-term evolution of nucleotide-binding site-leucine-rich repeat genes: Understanding gained from and beyond the legume family. Plant Physiol. 2014, 166, 217–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meziadi, C.; Richard, M.; Derquennes, A.; Thareau, V.; Blanchet, S.; Gratias, A.; Pflieger, S.; Geffroy, V. Development of molecular markers linked to disease resistance genes in common bean based on whole genome sequence. Plant Sci. 2016, 242, 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, Y.J.; Kim, K.H.; Shim, S.; Yoon, M.Y.; Sun, S.; Kim, M.Y.; Van, K.; Lee, S.H. Genome-wide mapping of NBS-LRR genes and their association with disease resistance in soybean. BMC Plant Biol. 2012, 12, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.S.; Yoo, M.H.; Jung, J.K.; Bilyeu, K.D.; Lee, J.D.; Kang, S. Detection of novel QTLs for foxglove aphid resistance in soybean. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2015, 128, 1481–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Njiti, V.N.; Meksem, K.; Iqbal, M.J.; Johnson, J.E.; Kassem, M.A.; Zobrist, K.F.; Kilo, V.Y.; Lightfoot, D.A. Common loci underlie field resistance to soybean sudden death syndrome in Forrest, Pyramid, Essex, and Douglas. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2002, 104, 294–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.J.C.; Doubler, T.W.; Kilo, V.; Suttner, R.; Klein, J.; Schmidt, M.E.; Gibson, P.T.; Lightfoot, D.A. Two Additional Loci underlying Durable Field Resistance to Soybean Sudden Death Syndrome (SDS). Crop Sci. 1996, 36, 1684–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luckew, A.S.; Leandro, L.F.; Bhattacharyya, M.K.; Nordman, D.J.; Lightfoot, D.A.; Cianzio, S.R. Usefulness of 10 genomic regions in soybean associated with sudden death syndrome resistance. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2013, 126, 2391–2403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Y.; Kurle, J.E.; Anderson, G.; Young, N.D. Association mapping and genomic prediction for resistance to sudden death syndrome in early maturing soybean germplasm. Mol. Breed. 2015, 35, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, R.; Chen, J.; Jiang, J.; Liu, G.; Liu, Y.; Tian, L.; Yu, L.; Chang, R.; Qiu, L. Mapping and validation of a dominant salt tolerance gene in the cultivated soybean (Glycine max) variety Tiefeng 8. Crop J. 2014, 2, 358–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cultivar | Rps | Phytophthora sojae Strains | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PNJ1 | PGD1 | Pm14 | Pm28 | PNJ3 | PNJ4 | P6497 | ||

| Harlon | 1a | R | S | S | S | S | S | R |

| Harosoy13XX | 1b | R | S | S | S | S | S | S |

| Williams79 | 1c | R | R | S | S | S | S | R |

| PI103091 | 1d | S | R | S | S | S | S | R |

| Williams82 | 1k | R | S | S | S | S | S | R |

| L76-1988 | 2 | S | S | S | S | S | S | S |

| Chapman | 3a | R | S | S | R | R | R | R |

| PRX146-36 | 3b | Ss | R | R | S | S | S | R |

| PRX145-48 | 3c | S | S | S | S | S | S | S |

| L85-2352 | 4 | S | S | S | R | R | S | R |

| L85-3059 | 5 | R | S | S | S | S | R | R |

| Harosoy62XX | 6 | S | S | S | S | R | S | R |

| Harosoy | 7 | S | S | S | S | S | R | S |

| Williams | rps | S | S | S | S | S | S | S |

| Huachun 2 | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | |

| Wayao | R | R | R | R | S | S | R | |

| Guizao 1 | R | S | S | S | S | R | S | |

| B13 | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | |

| Cross or Parent (1) | Total No. of Plants/Lines | Expected Ratio and Goodness of Fit | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resistance | Susceptibility | Expected ratio | χ2 | p | |

| Guizao 1 (R) | 200 | 0 | |||

| B13 (S) | 0 | 200 | |||

| F1 | 12 | 0 | |||

| F2 | 151 | 59 | 3:1 | 0.3 | 0.583 |

| F8:11 | 138 | 110 | 1:1 | 3.16 | 0.075 |

| Population (1) | No. | Gene Name (2) | Annotation | Ortholog (3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GB | 1 | Glyma.03g035500 | Plant mobile domain | AT2G04865.1 |

| 2 | Glyma.03g035600 | Lipid transfer protein 1 (LTP) | AT3G08770.1 | |

| 3 | Glyma.03g035700 | Lipid transfer protein 5 (LTP) | AT5G59310.1 | |

| 4 | Glyma.03g035800 | Pollen allergen; Rare lipoprotein A (RlpA)-like double-psi beta-barrel | AT5G05290.1 | |

| 5 | Glyma.03g035900 | MAC/Perforin domain-containing protein (MACPF) | AT1G29690.1 | |

| 6 | Glyma.03g036000 | Serine/threonine protein kinase (Ser/Thr) | AT5G01850.1 | |

| 7 | Glyma.03g036100 | No items to show | ||

| 8 | Glyma.03g036200 | Multidrug resistance protein | AT2G38510.1 | |

| CY | 1 | Glyma.03g034000 | (bHLH) DNA-binding superfamily protein | AT4G00050.1 |

| 2 | Glyma.03g034100 | Preprotein translocase Sec, Sec61-beta subunit protein | AT3G60540.1 | |

| 3 | Glyma.03g034200 | Leucine-rich repeat protein kinase family protein | AT3G56370.1 | |

| 4 | Glyma.03g034300 | No items to show | ||

| 5 | Glyma.03g034400 | Disease resistance protein (NBS-LRR class), putative | AT3G14470.1 | |

| 6 | Glyma.03g034500 | Disease resistance protein (NBS-LRR class), putative | AT3G14470.1 | |

| 7 | Glyma.03g034600 | No items to show | AT1G62130.1 | |

| 8 | Glyma.03g034700 | No items to show | AT2G01050.1 | |

| 9 | Glyma.03g034800 | Disease resistance protein (NBS-LRR class), putative | AT3G14470.1 | |

| 10 | Glyma.03g034900 | Disease resistance protein (NBS-LRR class), putative | AT3G14470.1 | |

| 11 | Glyma.03g035000 | Domain of unknown function DUF223 | AT2G05642.1 | |

| 12 | Glyma.03g035100 | PIF1-like helicase | AT3G51690.1 | |

| 13 | Glyma.03g035200 | CW-type Zinc Finger; B3 DNA binding domain | AT4G32010.1 | |

| 14 | Glyma.03g035300 | Disease resistance protein (NBS-LRR class), putative. Protein tyrosine kinase | AT3G08760.1 | |

| 15 | Glyma.03g035400 | PPR repeat | AT3G42630.1 | |

| 16 | Glyma.03g035500 | Plant mobile domain | AT2G04865.1 |

| No. | Rps Gene | Molecular Marker Interval | Physical Posistion (bp) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Rps1a | Satt159 | Satt009 | 3,197,845 | 3,932,116 |

| 2 | Rps1b | Satt530 | Satt584 | 5,669,877 | 9,228,144 |

| 3 | Rps1c | Satt530 | Satt584 | 5,669,877 | 9,228,144 |

| 4 | Rps1d | Satt152 | Sat_186 | 3,366,405 | 3,488,905 |

| 5 | Rps1k | 4,457,810 | 4,641,921 | ||

| 6 | Rps7 | Satt009 | Satt125 | 3,931,955 | 18,415,710 |

| 7 | RpsYu25 | Satt152 | Sat_186 | 3,366,405 | 3,488,905 |

| 8 | Rps9 | Satt631 | Satt152 | 2,943,883 | 3,366,655 |

| 9 | RpsYD29 | SattWM82–50 | Satt1 k4b | 3,857,715 | 4,062,474 |

| 10 | RpsHN | SSRSOYN-25 | SSRSOYN-44 | 4,227,863 | 4,506,526 |

| 11 | Rps gene in Waseshiroge | Satt009 | T003044871 | 3,910,260 | 4,486,048 |

| 12 | Rps gene in E00003 | 4,475,877 | 4,563,799 | ||

| 13 | RpsUN1 | BARCSOYSSR_03_0233 | BARCSOYSSR_03_0246 | 4,020,587 | 4,171,402 |

| 14 | RpsWY | 4,466,230 | 4,502,773 | ||

| 15 | RpsQ | BARCSOYSSR_03_0165 | InDel281 | 2,968,566 | 3,087,579 |

| 16 | RpsHC18 | BARCSOYSSR_03_0265 | BARCSOYSSR_03_0272 | 4,446,594 | 4,611,282 |

| 17 | RpsX | 2,910,913 | 3,153,254 | ||

| 18 | RpsGZ | 4,003,401 | 4,370,772 | ||

| 19 | Rps14 | Satt631 | BARCSOYSSR_03_0266 | 2,944,031 | 4,470,352 |

| 20 | RpsSDB | AX-90419199 | AX-90317436 | 3,373,644 | 4,295,128 |

| 21 | Rpsan1 | Gm03_4487138_A_C | Gm03_5451606_A_C | 4,296,322 | 5,354,087 |

| 22 | Rps gene in Ilpumgeomjeong | 3,990,383 | 4,260,579 | ||

| 23 | Rps15 | 4,292,416 | 4,370,772 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, B.; Bai, S.; Yang, X.; Niu, C.; Xia, Q.; Cai, Z.; Jia, J.; Ma, Q.; Lian, T.; Nian, H.; et al. Fine Mapping of Phytophthora sojae PNJ1 Resistance Locus Rps15 in Soybean (Glycine max (L.) Merr.). Agronomy 2025, 15, 2736. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122736

Chen B, Bai S, Yang X, Niu C, Xia Q, Cai Z, Jia J, Ma Q, Lian T, Nian H, et al. Fine Mapping of Phytophthora sojae PNJ1 Resistance Locus Rps15 in Soybean (Glycine max (L.) Merr.). Agronomy. 2025; 15(12):2736. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122736

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Bo, Si Bai, Ximeng Yang, Chanyu Niu, Qiuju Xia, Zhandong Cai, Jia Jia, Qibin Ma, Tengxiang Lian, Hai Nian, and et al. 2025. "Fine Mapping of Phytophthora sojae PNJ1 Resistance Locus Rps15 in Soybean (Glycine max (L.) Merr.)" Agronomy 15, no. 12: 2736. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122736

APA StyleChen, B., Bai, S., Yang, X., Niu, C., Xia, Q., Cai, Z., Jia, J., Ma, Q., Lian, T., Nian, H., & Cheng, Y. (2025). Fine Mapping of Phytophthora sojae PNJ1 Resistance Locus Rps15 in Soybean (Glycine max (L.) Merr.). Agronomy, 15(12), 2736. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122736