Design and Experiment of an Inter-Plant Obstacle-Avoiding Oscillating Mower for Closed-Canopy Orchards

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

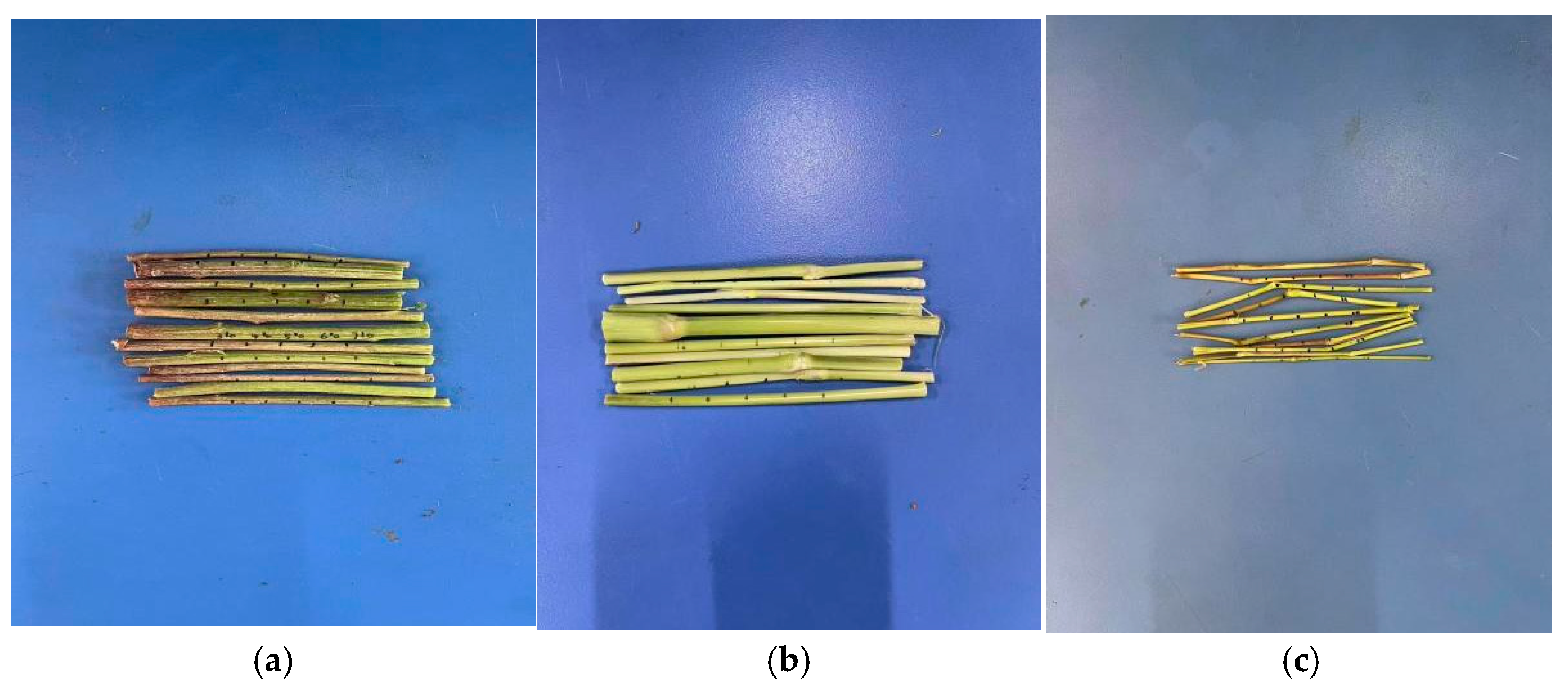

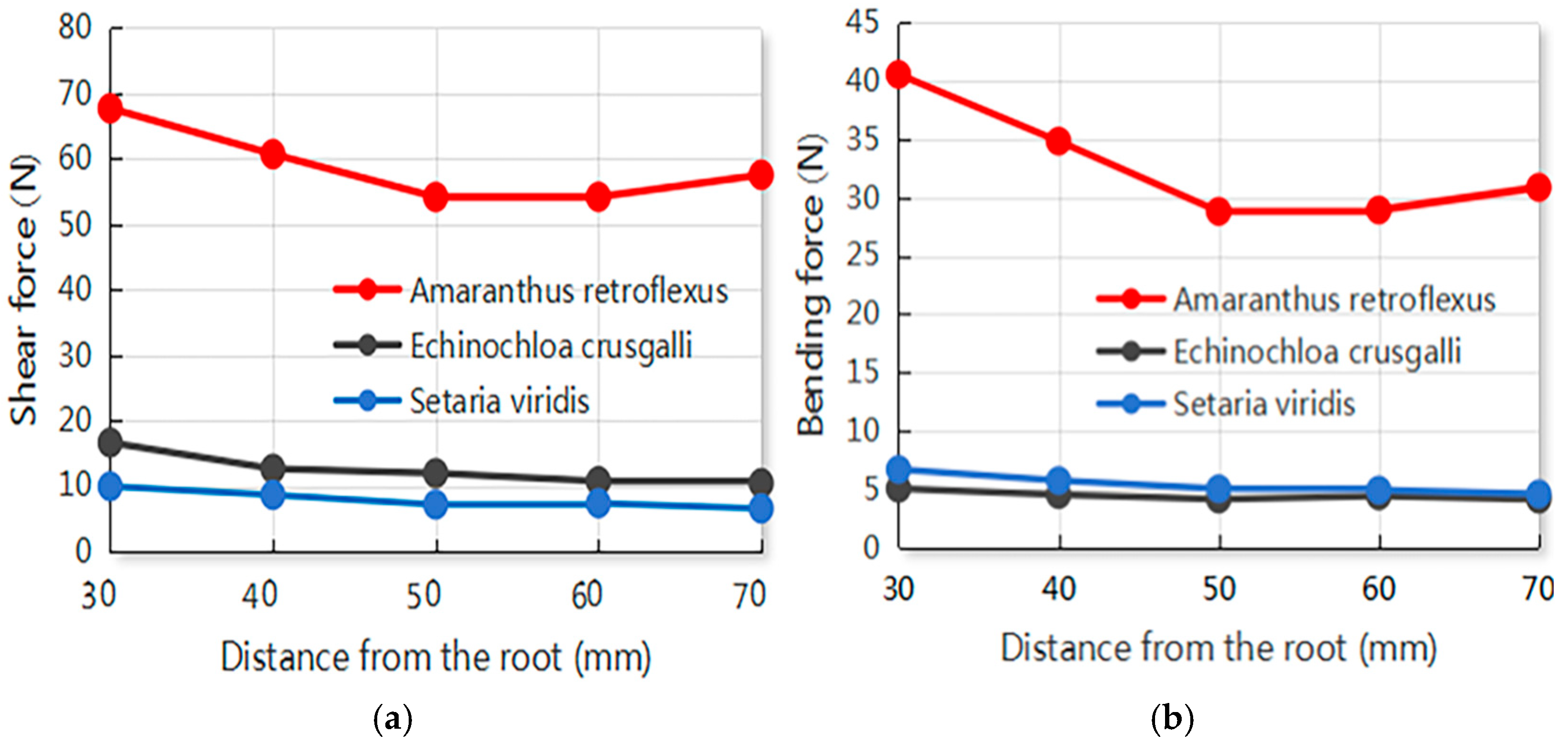

2.1. Shear and Bending Tests of Orchard Weeds

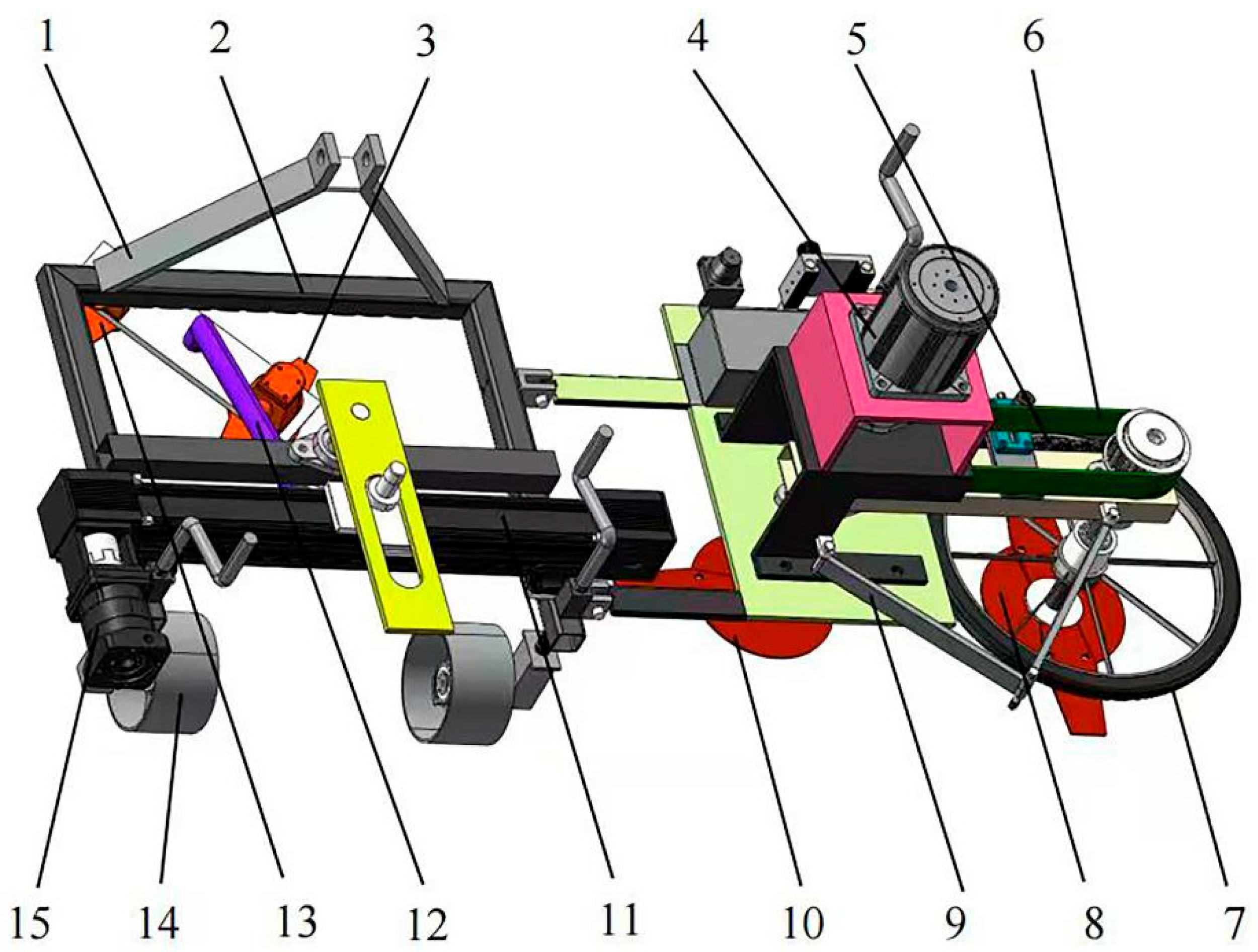

2.2. Overall Design Complete Machine Structure and Working Principles

2.2.1. Design Requirements

- (1)

- Adaptability and Trafficability. To operate effectively in the interlacing canopies, disordered tree structures, narrow rows and complex terrain of mountainous closed-canopy orchards, the mower should have a compact and simplified structure. The total cutting width should be under 2 m, and the overall height should not exceed 1.2 m to ensure smooth passage through the confined, low-clearance environment [5].

- (2)

- Mowing Quality and Adjustability. During mowing operations, if the stubble height exceeds 10 cm, it encourages weed regrowth; if it falls below 5 cm, it severely damages the grass and undermines soil and water conservation [27]. Given the dense and complex growth of weeds in closed-canopy orchards, to accommodate varying agronomic requirements for different weed species, growth stages, and regions, the mower should be equipped with an adjustable stubble height mechanism, providing a cutting height range of 50–100 mm [5].

- (3)

- Obstacle Avoidance and Lightweight Design. Since the propulsion power in a mobile system’s energy model is approximately proportional to its total mass, weight reduction directly lowers the energy cost for travel, steering, and obstacle avoidance [28]. The mower should be capable of intra-plant obstacle avoidance to prevent damage to fruit trees. A lightweight design is crucial to minimize the load on the unmanned crawler vehicle and ensure adequate operating time for the power system.

2.2.2. Complete Machine Structure and Working Principles

2.3. Key Components and Main Parameters

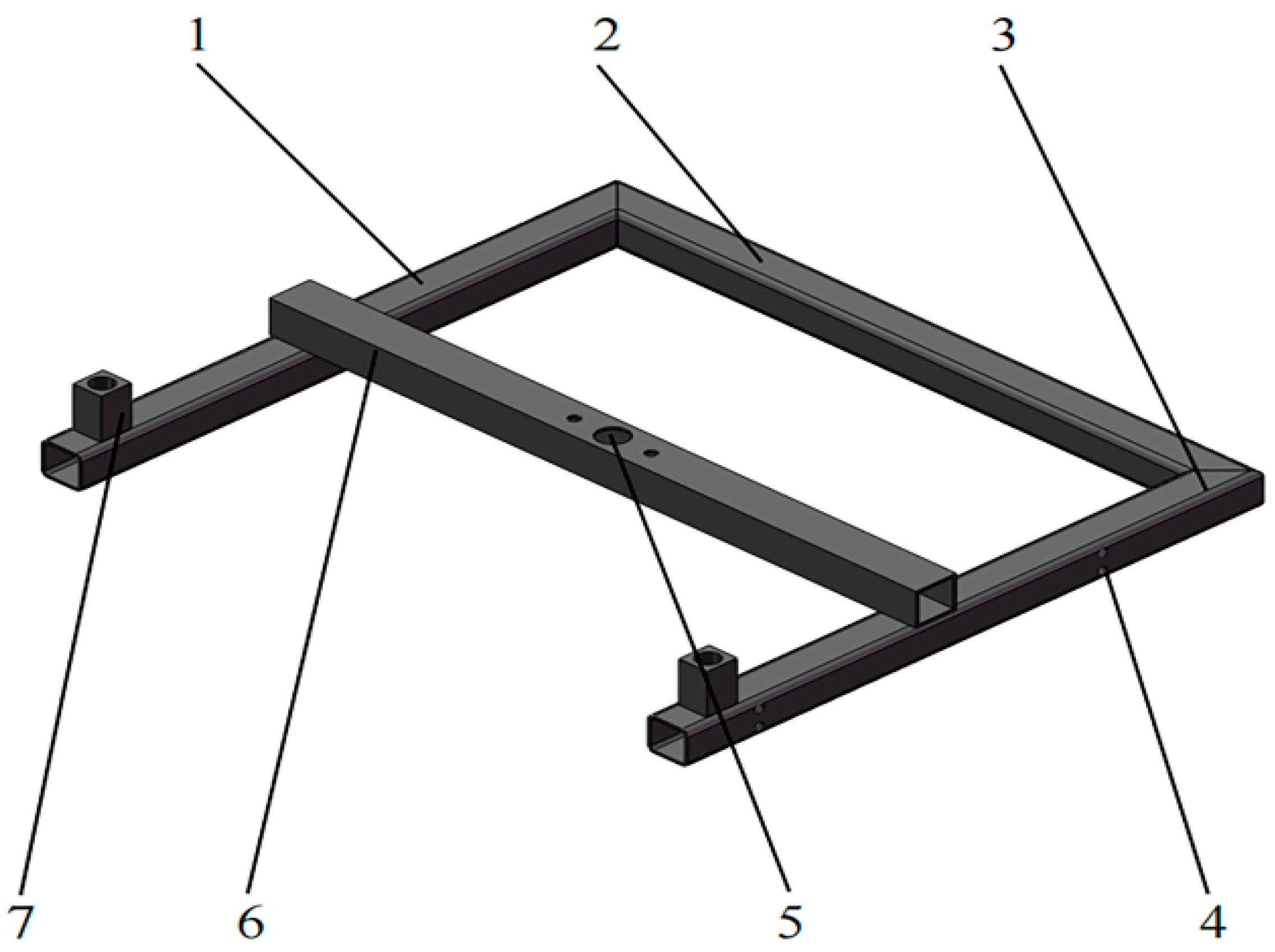

2.3.1. Frame Design

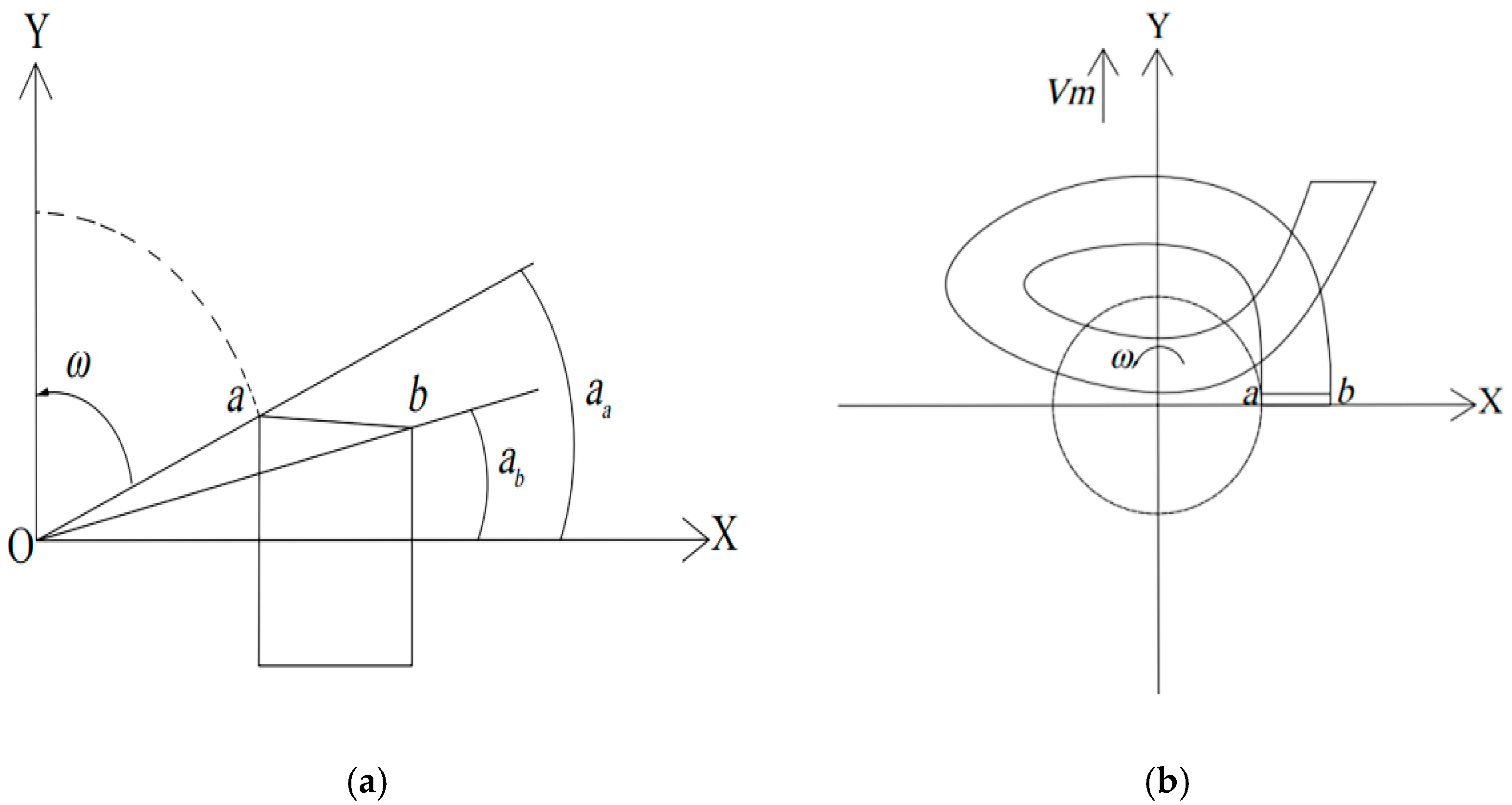

2.3.2. Cutting System Design

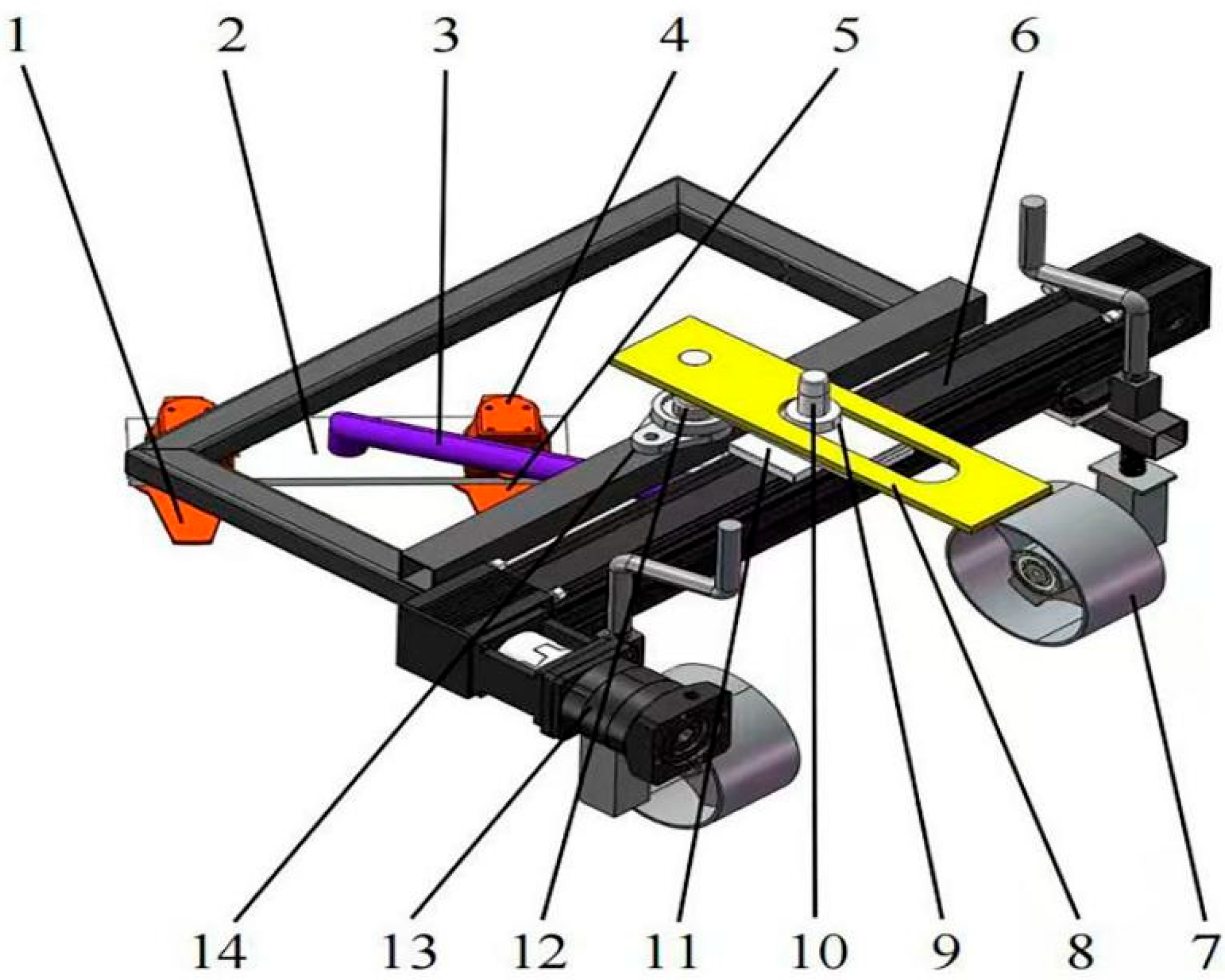

2.3.3. Obstacle Avoidance Mechanism Design

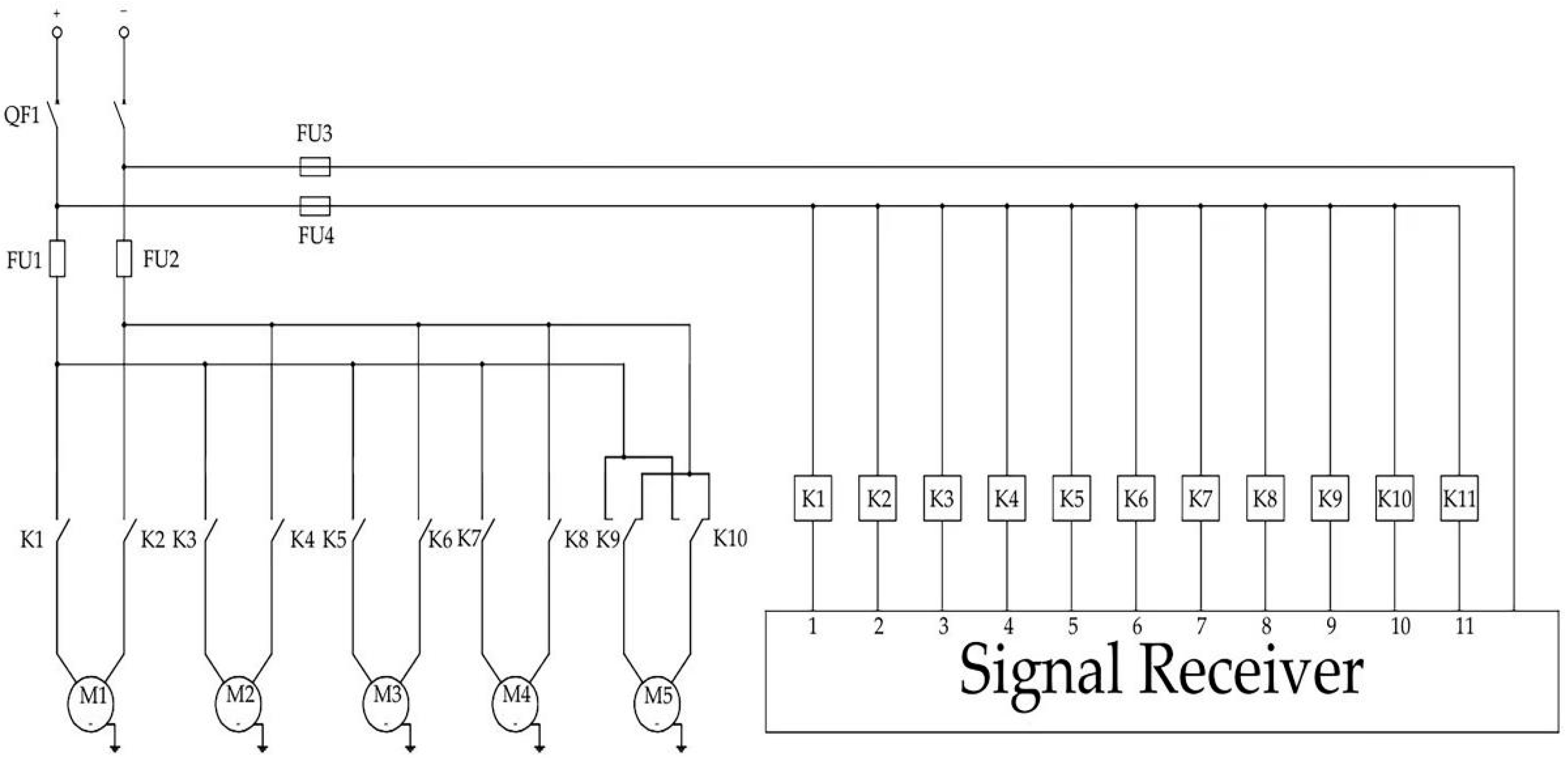

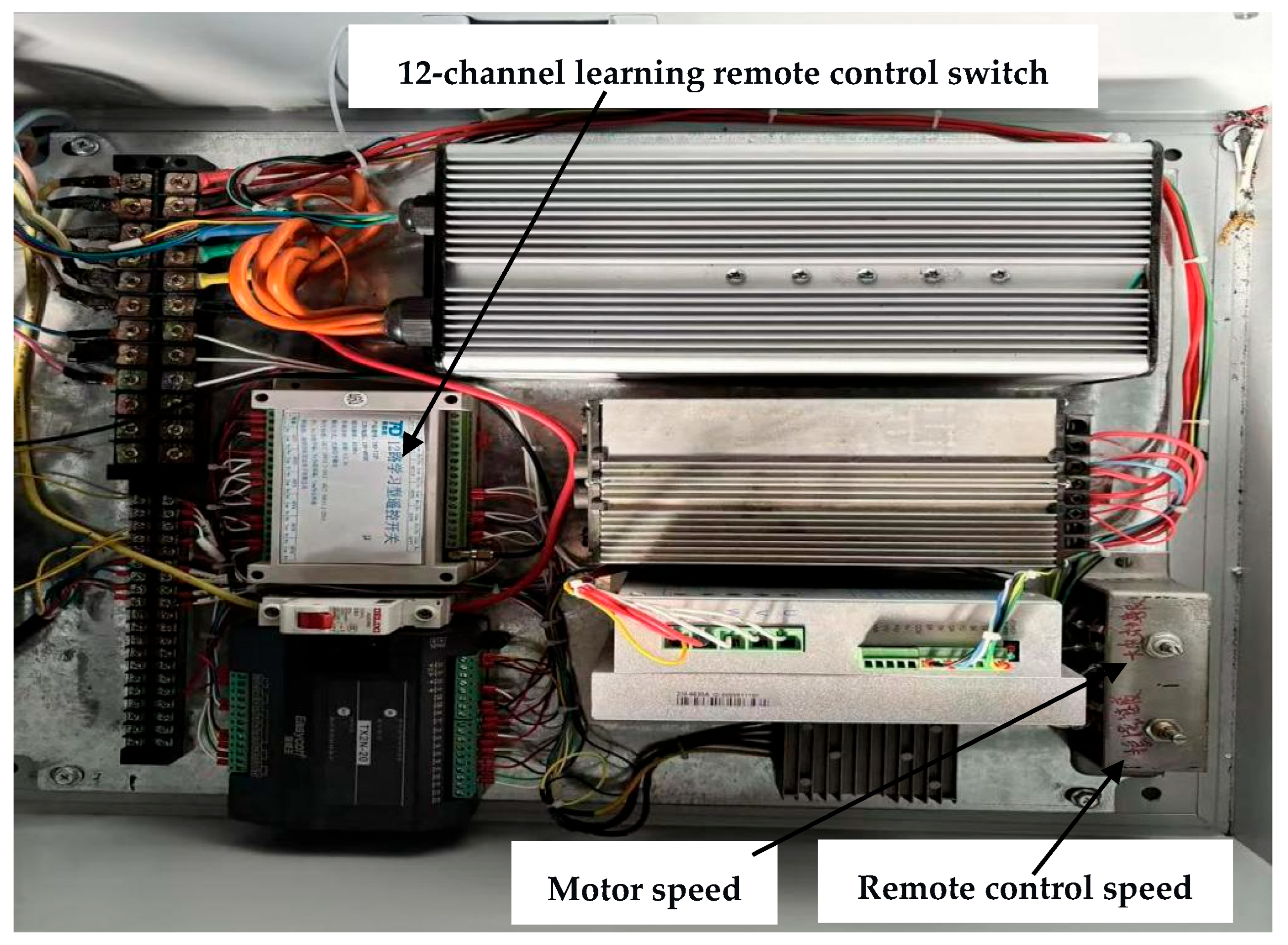

2.4. Design of the Mowing Control System

2.5. Field Operation Performance Test

2.5.1. Test Conditions

2.5.2. Test Method

2.6. Data Processing

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Analysis of Shear Force and Bending Resistance of Orchard Weeds

3.2. Mowing Power Consumption

3.3. Power and Transmission System Design

3.4. Field Performance Test Results and Analysis of Mower

3.4.1. Field Performance Test Results and Analysis

3.4.2. Advantages of the Oscillating Mechanism

3.4.3. Practical Limitations and Future Work

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, Y.; Han, L.; Qi, K.; Hou, J. Transaction Costs and Farm-to-Market Linkages in China: Empirical Evidence from Apple Producers. J. Agric. Sci. 2024, 12, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.X. Thoughts on the development of China’s fruit industry. J. Fruit Sci. 2021, 38, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.J.; Jiang, S.J.; Chen, B.T.; Lü, H.T.; Wan, C.; Kang, F. Review on Technology and Equipment of Mechanization in Hilly Orchard. J. Agric. Mach. 2020, 51, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.C. Application Status and Development Suggestion of Orchard Agriculture Mechanization in Shanxi Province. J. Fruit Res. 2022, 3, 85–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.Z.; Sun, J.B.; Li, Y.N.; Zhang, Y.Z.; Liu, Z.J. Design and performance test of image transmission remote control mower in closed orchard. J. Jilin Univ. Eng. Tech. Ed. 2024, 54, 281–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Zhao, Q.F.; Li, L.; Zhang, J.C.; Du, J.J.; Niu, Z.M. Major cultivation techniques suitable for fruit high quantityand efficiency production Shanxi Province in 2020. J. Fruit Res. 2020, 1, 52–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.N.; Wang, C.; He, J.Z.; Zhang, D. Causes and Reformation Strategies of Apple Closed-in Orchards. Xiandai Nongcun Keji 2019, 12, 43+99. [Google Scholar]

- Shang, G.K. Causes of Canopy Closure and Improvement Measures in Standard Apple Orchards. Northwest Hortic. 2022, 12, 15–16. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, J.S.; Li, F.; Yin, C.J. Orchard grass safeguards sustainable development of fruit industry in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 382, 135291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.P.; Zhang, T.; Pan, G.J.; Gao, D.S.; Wang, Z.; Gao, X. Research Progress of Domestic and Foreign Growing Grass Technologies and Cutting Machines in Orchard. J. Chin. Agric. Mech. 2017, 38, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.; Xiang, Y.Z.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.E. Effects of sod cultivation on soil nutrients in orchards across China: A meta-analysis. Soil Till. Res. 2017, 169, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, G.T.; Yang, F.Z.; Sun, J.B.; Liu, Z.J. Analysis and test of the obstacle negotiation performance of a small hillside crawler tractor during climbing process. J. Agric. Mach. 2020, 51, 374–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.F.; Weng, W.X.; Ju, J.Y.; Chen, J.S.; Wang, J.W.; Wang, H.L. Design and experiment of weeder between rows in rice field based on remote control steering. J. Agric. Mach. 2021, 52, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, M.; Pei, Y.; Liu, Z.H. Cutting weed with an improved test bench and measurement of cutting resistance. J. Hunan Agric. Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2013, 39, 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, F.B. Design and Experimental Study on Profiling Obstacle Avoidance Mower for Mountain Orchard. Master’s Thesis, Jiangsu University, Zhenjiang, China, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.N. Design and Optimization of a Remote-Controlled Weeding Machine for Hilly and Mountainous Orchards. Master’s Thesis, Chongqing Three Gorges University, Chongqing, China, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.H.; Zhang, F.W.; Cao, Z.Z. Experiment on stalk mechanical properties of legume forage and grasses. Tran. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2009, 25, 122–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Y.X.; Xue, K.X.; Feng, G.J.; Zhu, X.W.; Wang, R.Y.; Liu, X. Experimental Study on Mechanical Properties of Roots and Stems of Three Herbaceous Plants in Kunming. For. Eng. 2022, 38, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.P. Design and Experimental Study of Electronic Controlled Lawn Mower for Mountain Orchard. Master’s Thesis, Jiangsu University, Zhenjiang, China, 2020. Available online: https://d.wanfangdata.com.cn/thesis/CiBUaGVzaXNOZXdTMjAyNTA2MTMyMDI1MDYxMzE2MTkxNhIJRDAyMzg3MDI5Ggh5YXluNmxseQ%3D%3D (accessed on 8 November 2024).

- Xie, S.Y.; Zhao, H.; Yang, S.H.; Xie, Q.J.; Yang, M.J. Design, Analysis and Test of Small Rotary Lawn Mower of Single-Disc Type. INMATEH Agric. Eng. 2020, 62, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.C.; Zhong, B.; Min, L.Q.; Liu, X.F.; Sun, S.G.; Zhang, Q.F. Design and Test of 9GS-2.0 Field Mower. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2020, 41, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.S.; Wang, J.S.; Xu, Z.W. The Small Type Reciprocating Mower of Orchard. J. Agric. Mech. Res. 2007, 06, 68–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouwenhoven, J.K. Intra-row mechanical weed control—Possibilities and problems. Soil Till. Res. 1997, 41, 87–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xi, X.B.; Chen, M.; Shi, Y.J.; Zhang, Y.F.; Zhang, B.F.; Qu, J.W.; Zhang, R.H. Design of and experiment on reciprocating inter-row weeding machine for strip-seeded rice. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Yi, X.K.; He, Y.C.; Tang, Z.H.; Liu, W.T. Design and experiment of obstacle avoidance mower for trunk orchards. J. Tarim Univ. 2023, 35, 78–87. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, C.C.; Xu, L.M.; Wang, Q.J.; Yuan, Q.C.; Ma, S.; Niu, C.; Yuan, X.T.; Zeng, J.; Wang, S.S.; Chen, C. Design and experiment of bilateral operation intra-row auto obstacle avoidance weeder for trellis cultivated grape. Tran. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2019, 35, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.W.; Hao, M.D.; Tang, T. Effects of Stubble Application on Soil and Water Loss Under Simulated Rainfall. Bull. Soil Water Conserv. 2009, 29, 134–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.M.; Li, Z.S.; Yang, L.; Ren, K.X.; Yang, F.Y.; Wang, K. Overall design of long-endurance multi-rotor fuel cell UAV. J. Aerosp. Power 2025, 40, 20230551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.P.; Liu, J.F.; Li, J.Y. The Analysis and Design of Orchard Mower Stubble Height of the Mechanism Motion. J. Agric. Mech. Res. 2013, 35, 43–45+49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.Y.; Li, Q.J. Orchard simulation environment construction based on undulating terrain and SLAM algorithm testing. J. For. Eng. 2024, 9, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 10395.25-2020; National Technical Committee for Standardization of Agricultural Machinery (SAC/TC 201). Agricultural and Forestry Machinery—Safety—Part 25:Rotary Disc and Drum Mowers and Flail Mowers. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2020. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=m8Pzpa6JQHJHTjsuMUtOKYWD-WgPYF-SVOebD4lVO9vM3ydOO6ZOD-CSkoTKeKfoVlVkVbnKcYpUyUeFFHedgvEAbT_4w9wWqHkILjnjt7wTbOp3l11ZgZGv-92g1aEJlx2-TKGE8SVbAwwEJJfWxA14vr14xCcDc43ikeWWTx8H5UgGd4wg8Q==&uniplatform=NZKPT&languag (accessed on 10 November 2024).

- Cheng, X.L. Design and Experimental Research of Self-Propelled Riding of Orchard Mower. Master’s Thesis, Hebei Agriculture University, Baoding, China, 2016. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=m8Pzpa6JQHLBlbFQfBYNvNkE6zY_LdNUykBIbM9WVohrZvR-NK2750GjvEOwCd-I1lL7hpOYcfKKdcQKTuYLZyp31N4SgTP-iSPmiqlwZ7MJLIKeiq-AiXQZsXg3vLn84ocQ9aVQgzJiYAGNKu-6J_fTrDDmO0W4CgbilR2Ec9id_HkT0T6xXLNloEfr5pnh&uniplatform=NZKPT (accessed on 9 November 2024).

- Wang, P.F.; Liu, J.F.; Cheng, X.L.; Li, J.P. Experimental Study on Riding Mower’s Cutting Blade Performance. J. Agric. Mech. Res. 2015, 37, 181–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.J. Discussion about the Design and Dynamic Characteristics of Lawn Mower. Tim. Agric. Mach. 2016, 43, 80–81. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.F.; Lai, X.M.; Li, H.T.; Ni, J. Modeling of three-dimensional cutting forces in micro-end-milling. J. Micromech. Microeng. 2007, 17, 671–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.C.; Huang, X.D.; Fang, C.G.; Guo, E.K. Key parameter optimization of duplex cutter gear milling based on space envelope theory. Compu. Integr. Manuf. Syst. 2014, 20, 2194–2202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, N. Design and Experimental Research on Closed Orchard Lawn Mowers. Master’s Thesis, Shanxi Agricultural University, Jinzhong, China, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, T.Q. Development of Double Disc Mower. Master’s Thesis, Lanzhou Agricultural University, Lanzhou, China, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, P.Y. Design and Test of Mountain Orchard Profile Mower. Master’s Thesis, Huazhong Agricultural University, Wuhan, China, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertozzi, M.; Bombini, L.; Cerri, P.; Coati, A.; Debattisti, S.; Grisleri, P.C.; Medici, P.; Panciroli, M.; Zani, P. Obstacle detection and classification fusing radar and vision. In Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium, Eindhoven, The Netherlands, 4–6 June 2008; pp. 608–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z.G.; Yang, X.; Jiang, Z.H.; Wang, P.F. Dynamics Analysis and Experiment of Obstacle Avoidance Cutting Mechanism for Ridge Grass in Orchard. J. Agric. Mech. Res. 2024, 46, 27–32+41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.P.; Liu, J.F.; Li, J.Y.; Wang, P.F.; Hao, Y.J.; Zheng, C. The Performance and Working Quality Analysis of the Orchard Mower. J. Agric. Mech. Res. 2013, 35, 198–201+206. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.S.; Kang, J.M.; Peng, Q.J.; Chen, Y.K.; Fang, H.M.; Niu, M.M.; Wang, S.W. Design and experiment of obstacle avoidance weeding machine for fruit trees. J. Jilin Univ. Eng. Tech. Ed. 2023, 53, 2410–2420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Q.Y.; Lei, X.H.; Ma, Z.B.; Li, J. Experimental Study on F. US–UFO Mower for Avoiding Obstacles in Orchards. J. Chin. Agric. Mech. 2021, 42, 65–71+77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item | Value |

|---|---|

| Unmanned vehicle chassis power (kW) | 13.4 |

| Mower overall size (L × W × H mm) | 1510 × 610 × 510 |

| Mower overall weight (kg) | 80 |

| Walking mode | Self-propelled |

| Operation mode | Remote mode |

| Operation speed (m/s) | 0–1.5 |

| Reciprocating mechanism motor power (kW) | 0.75 |

| Inter-row cutting disc motor power (kW) | 2 × 2.2 |

| Intra-plant mowing motor power (kW) | 3 |

| Inter-row cutting disc rotational speed (r/min) | 8000 |

| Intra-plant cutting disc rotational speed (r/min) | 3000 |

| Inter-row working width (mm) | 1000 |

| Intra-plant working width (mm) | 800 |

| Item | Value |

|---|---|

| Inter-row cutter disc diameter (mm) | 255 |

| Intra-plant cutter disc diameter (mm) | 400 |

| Oscillating arm diameter (mm) | 33 |

| Oscillating arm length (mm) | 400 |

| Reciprocating speed (mm/s) | 800 |

| Pulley Width (mm) | 40 |

| Synchronous belt model | 8M-1072 |

| Synchronous pulley model | 8 M-30 teeth |

| Synchronous pulley diameter (mm) | 75 |

| Distance from the Root | Shear Force (N) | Bending Force (N) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amaranthus retroflexus | Echinochloa crus-galli | Setaria viridis | Amaranthus retroflexus | Echinochloa crus-galli | Setaria viridis | |

| 30 (mm) | 67.66 ± 49.53 a | 16.59 ± 11.68 a | 9.90 ± 2.83 a | 40.53 ± 27.24 a | 5.06 ± 3.28 a | 6.70 ± 2.30 a |

| 40 (mm) | 60.66 ± 50.02 a | 12.59 ± 6.77 a | 8.59 ± 3.40 ab | 34.82 ± 23.88 a | 4.53 ± 2.89 a | 5.75 ± 1.70 ab |

| 50 (mm) | 54.11 ± 37.13 a | 11.92 ± 6.72 a | 7.12 ± 3.03 ab | 28.80 ± 20.04 a | 4.15 ± 2.69 a | 5.05 ± 1.71 ab |

| 60 (mm) | 54.13 ± 43.04 a | 10.69 ± 9.13 a | 7.33 ± 3.00 ab | 28.91 ± 18.31 a | 4.42 ± 3.10 a | 4.94 ± 1.69 ab |

| 70 (mm) | 57.49 ± 46.05 a | 10.39 ± 9.13 a | 6.52 ± 1.83 b | 30.85 ± 19.22 a | 4.14 ± 3.12 a | 4.61 ± 1.91 b |

| Row Number | Number of Fruit Trees Planted (Plant) | Number of Successfully Passed Trees (Plant) | Obstacle Avoidance Pass Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Row 1 | 26 | 26 | 100 |

| Row 2 | 22 | 22 | 100 |

| Row 3 | 23 | 23 | 100 |

| Working Pass | Inter-Row Cutting Width (mm) | Mean ± SD (mm) | Cutting Width Utilization Rate (%) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |||

| 1 | 971 | 962 | 953 | 956 | 963 | 984 | 949 | 981 | 958 | 973 | 965 ± 11.83 | 96.5% |

| 2 | 967 | 981 | 948 | 957 | 985 | 989 | 956 | 964 | 978 | 975 | 970 ± 13.70 | 97.0% |

| 3 | 982 | 964 | 979 | 989 | 949 | 969 | 956 | 976 | 974 | 982 | 972 ± 12.54 | 97.2% |

| Working Pass | Stubble Height (mm) | Mean ± SD (mm) | Coefficient of Variation (%) | Stability Coefficient (%) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | ||||

| 1 | 73 | 69 | 76 | 62 | 77 | 79 | 70 | 75 | 69 | 61 | 70.7 ± 5.58 | 7.90 | 92.10 |

| 65 | 72 | 79 | 67 | 74 | 63 | 64 | 73 | 75 | 71 | ||||

| 2 | 73 | 65 | 74 | 75 | 76 | 61 | 79 | 78 | 64 | 74 | 71.8 ± 5.39 | 7.51 | 92.49 |

| 78 | 72 | 68 | 66 | 76 | 71 | 73 | 74 | 63 | 75 | ||||

| 3 | 67 | 72 | 65 | 63 | 72 | 71 | 79 | 78 | 64 | 66 | 71.1 ± 5.96 | 8.39 | 91.61 |

| 78 | 75 | 76 | 62 | 64 | 78 | 77 | 73 | 76 | 65 | ||||

| Working Pass | Number of Uncut Weeds (Plant) | Total Number of Weeds (Plant) | Missed-Cutting Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 8 | 461 | 1.74% |

| 2 | 9 | 478 | 1.88% |

| 3 | 6 | 445 | 1.35% |

| Mean | 7.67 | 461.3 | 1.66% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, J.; Pan, W.; Wang, X.; An, Y.; An, N.; Duan, X.; Zhao, F.; Han, F. Design and Experiment of an Inter-Plant Obstacle-Avoiding Oscillating Mower for Closed-Canopy Orchards. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2893. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122893

Wang J, Pan W, Wang X, An Y, An N, Duan X, Zhao F, Han F. Design and Experiment of an Inter-Plant Obstacle-Avoiding Oscillating Mower for Closed-Canopy Orchards. Agronomy. 2025; 15(12):2893. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122893

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Juxia, Weizheng Pan, Xupeng Wang, Yifang An, Nan An, Xinxin Duan, Fu Zhao, and Fei Han. 2025. "Design and Experiment of an Inter-Plant Obstacle-Avoiding Oscillating Mower for Closed-Canopy Orchards" Agronomy 15, no. 12: 2893. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122893

APA StyleWang, J., Pan, W., Wang, X., An, Y., An, N., Duan, X., Zhao, F., & Han, F. (2025). Design and Experiment of an Inter-Plant Obstacle-Avoiding Oscillating Mower for Closed-Canopy Orchards. Agronomy, 15(12), 2893. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122893