Effects of Cassava Brown Streak Disease and Harvest Time on Two Cassava Mosaic Disease-Resistant Varieties in Eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Location and Experimental Design

2.2. Planting Material and Virus Status Confirmation

2.3. Planting

2.4. Soil Characteristics and Climatic Conditions

2.5. Assessment of CBSD Foliar and Root Symptoms

2.6. Growth and Yield Assessment

2.7. Data Analysis

3. Results

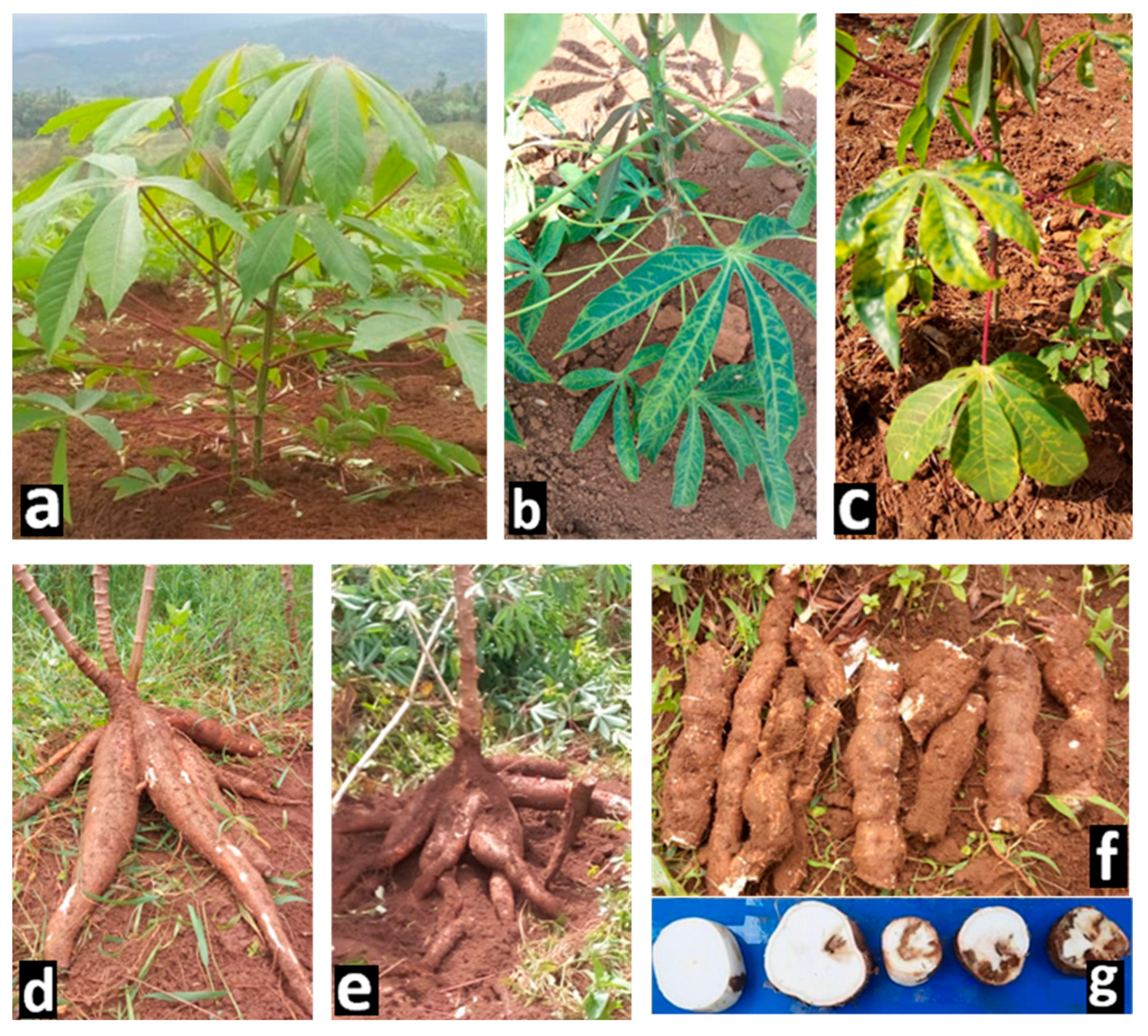

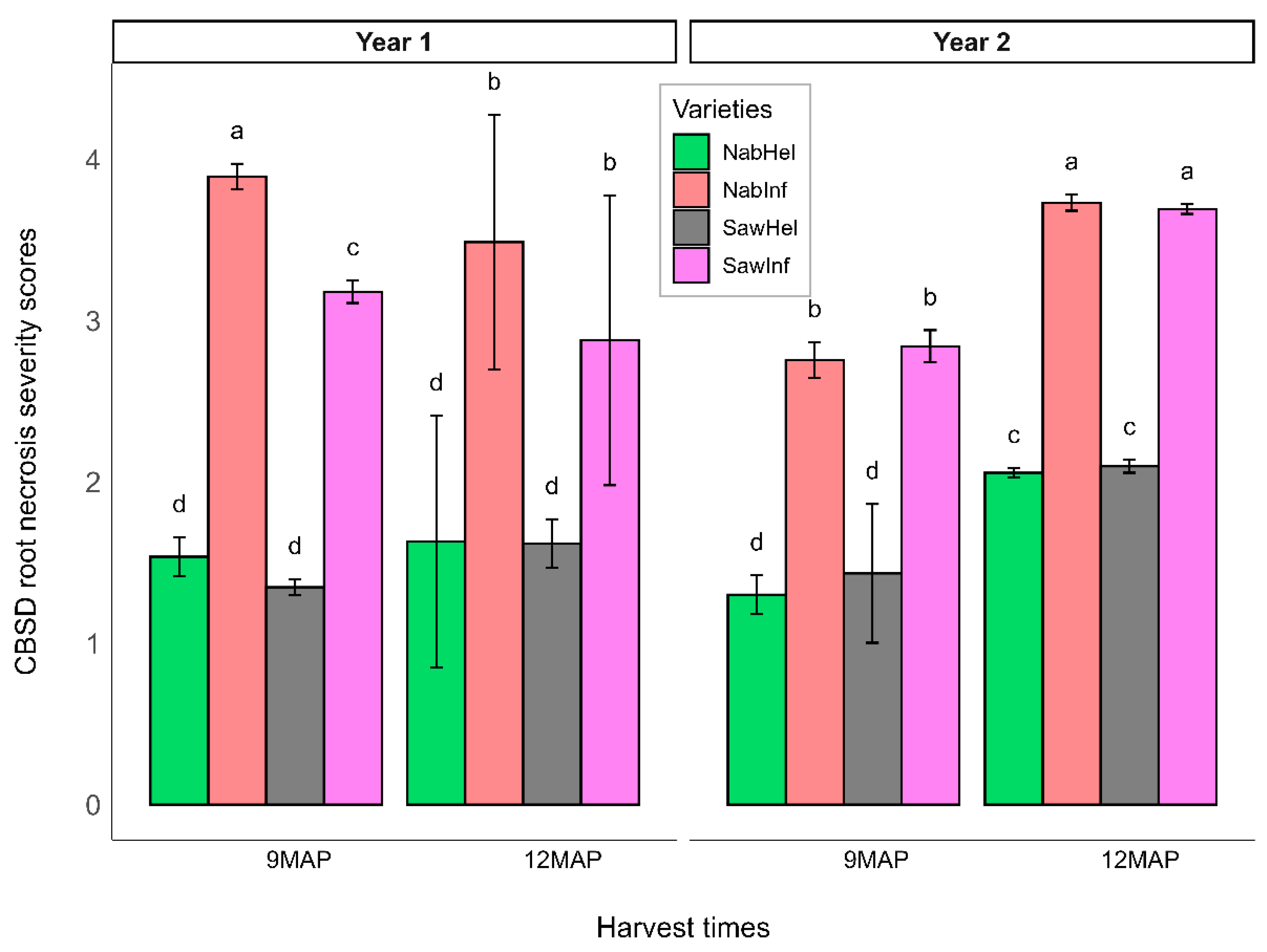

3.1. Cassava Brown Streak Disease Foliar and Roots Symptoms

3.2. Effect of CBSD on Vegetative Growth of Nabana and Sawasawa Cassava Varieties

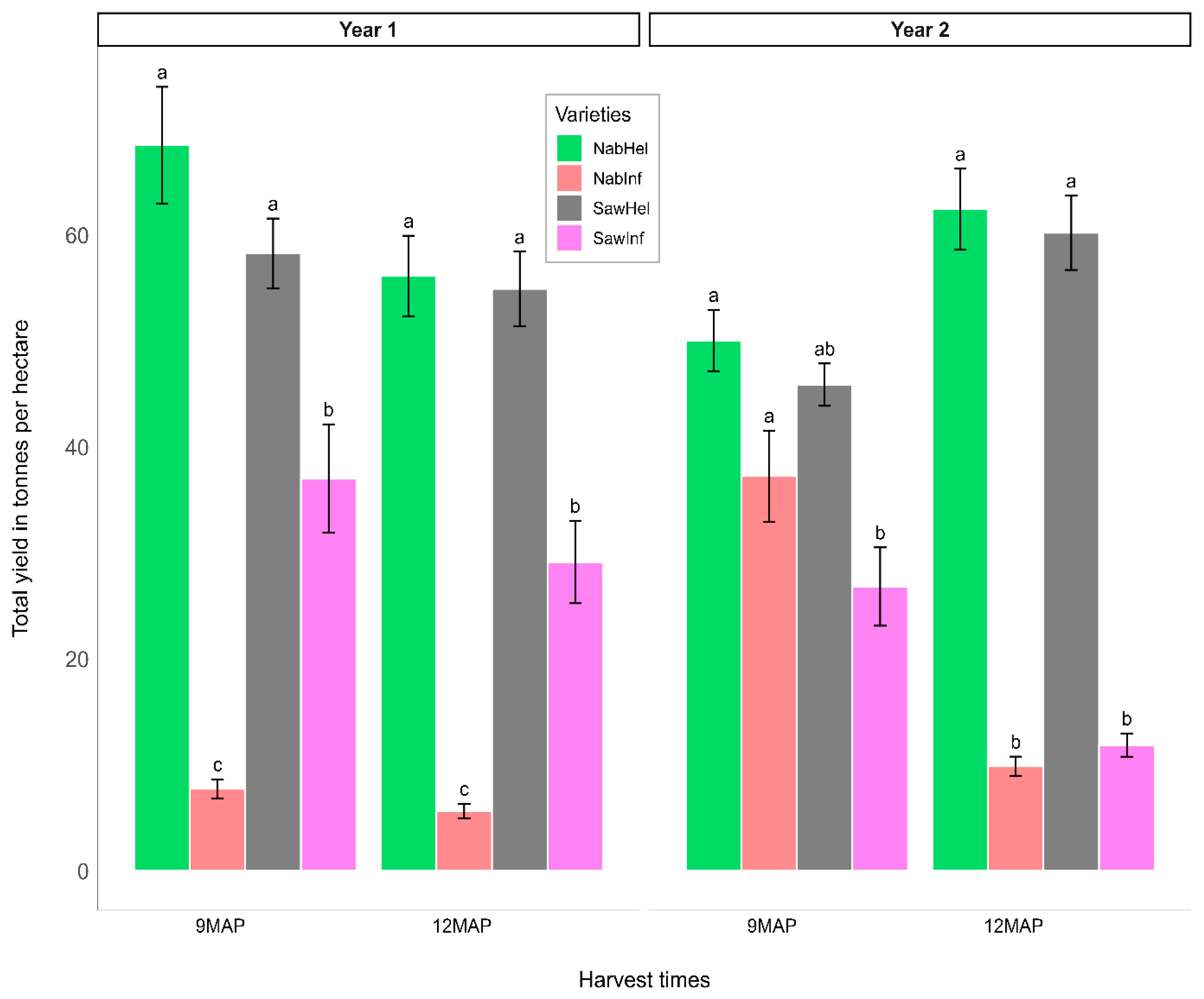

3.3. Total Fresh Root Yield Assessment (t/ha)

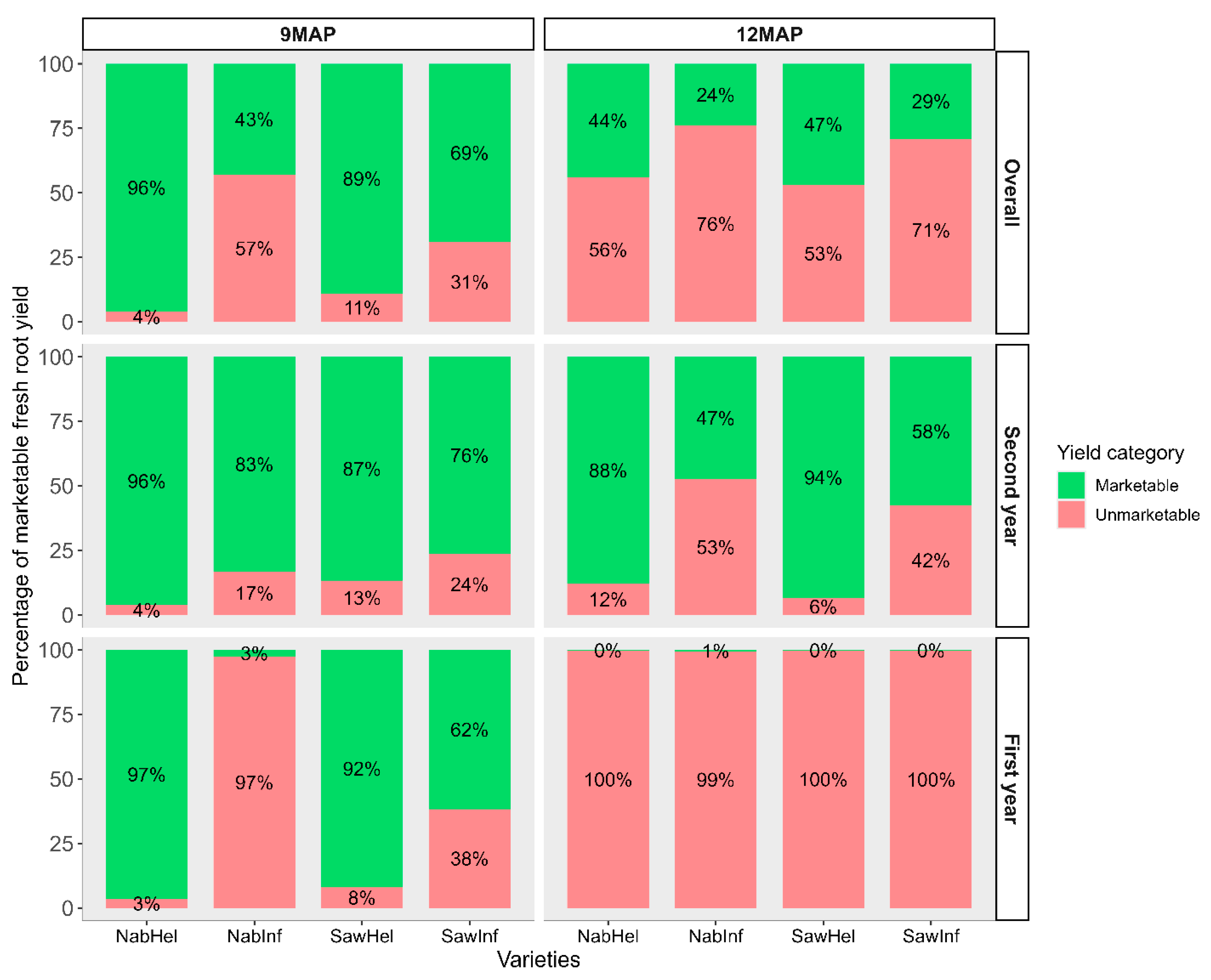

3.4. Assessment of Marketable Fresh Root Yield

3.5. Cassava Brown Streak Disease Percentage Reduction Losses Effects

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chikoti, P.C.; Tembo, M. Expansion and impact of cassava brown streak and cassava mosaic diseases in Africa: A review. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 6, 1076364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houngue, J.A.; Pita, J.S.; Cacaï, G.H.T.; Zandjanakou-Tachin, M.; Abidjo, E.A.E.; Ahanhanzo, C. Survey of farmers’ knowledge of cassava mosaic disease and their preferences for cassava cultivars in three agro-ecological zones in Benin. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2018, 14, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanginga, N.; Mbabu, A. Root and Tuber Crops (Cassava, Yam, Potato and Sweet Potato), Feeding Africa, Background Paper on Action Plan for African Agricultural Transformation. In Proceedings of the Feeding Africa, Abdou Diouf International Conference Center, Dakar, Senegal, 21–23 October 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Casinga, C.M.; Shirima, R.R.; Mahungu, N.M.; Tata-Hangy, W.; Bashizi, K.B.; Munyerenkana, C.M.; Ughento, H.; Enene, J.; Sikirou, M.; Dhed’a, B.; et al. Expansion of the cassava brown streak disease epidemic in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. Plant Dis. 2021, 105, 2177–2188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaweesi, T.; Kawuki, R.; Kyaligonza, V.; Baguma, Y.; Tusiime, G.; Morag, E.F. Field evaluation of selected cassava genotypes for cassava brown streak disease based on symptom expression and virus load. Virol. J. 2014, 11, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storey, H.H. Virus diseases of East African plants: VI-A progress report on studies of the diseases of cassava. East Afr. Agric. J. 1936, 2, 34–39. [Google Scholar]

- Hillocks, R.J.; Raya, M.; Mtunda, K.; Kiozia, H. Effects of brown streak virus disease on yield and quality of cassava in Tanzania. J. Phytopathol. 2001, 149, 389–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manyong, V.M.; Maeda, C.; Kanju, E.; Legg, J. Economic damage of cassava brown streak disease in sub-Saharan Africa. In Tropical Roots and Tuber Crops and the Challenges of Globalization and Climate Changes = Plantes à Racines et Tubercules Tropicales et les Défis de Mondialisation et du Changement Climatique, 1st ed., Proceedings of the 11th Triennial Symposium of the ISTRC-AB, Kinshasa, RD Congo, 4–8 October 2010; Okechukwu, R.U., Ntawururuhunga, P., Eds.; ISTRC-AB: Oyo State, Nigeria, 2012; Volume 1, pp. 78–82. [Google Scholar]

- Kwibuka, Y.; Nyirakanani, C.; Bizimana, J.P.; Bisimwa, E.; Brostaux, Y.; Lassois, L.; Vanderschuren, H.; Massart, S. Risk factors associated with cassava brown streak disease dissemination through seed pathways in Eastern D.R. Congo. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 803980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mbanzibwa, D.R.; Tian, Y.P.; Tugume, A.K.; Mukasa, S.B.; Tairo, F. Genetically distinct strains of Cassava brown streak virus in the Lake Victoria basin and the Indian Ocean coastal area of East Africa. Arch. Virol. 2009, 154, 353–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, S.; Koerbler, M.; Stein, B.; Pietruszka, A.; Paape, M. Analysis of cassava brown streak viruses reveals the presence of distinct virus species causing cassava brown streak disease in East Africa. J. Gen. Virol. 2010, 91, 1365–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanju, E.; Uzokwe, V.N.E.; Ntawuruhunga, P.; Tumwegamire, S.; Yabeja, J.; Pariyo, A.; Kawuki, R. Varietal response of cassava root yield components and root necrosis from cassava Brown streak disease to time of harvesting in Uganda. Crop Prot. 2019, 120, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndunguru, J.; Sseruwagi, P.; Tairo, F.; Stomeo, F.; Maina, S.; Djinkeng, A.; Monica, K.M.; Boykin, L.M. Analyses of twelve new whole genome sequences of cassava brown streak viruses and Ugandan cassava brown streak viruses from East Africa: Diversity, supercomputing and evidence for further speciation. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e01411939. [Google Scholar]

- Patil, B.L.; Legg, J.P.; Kanju, E.; Fauquet, C.M. Cassava brown streak disease: A threat to food security in Africa. J. Gen. Virol. 2015, 96, 956–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulenga, R.M.; Boykin, L.M.; Chikoti, P.C.; Sichilima, S.; Ng’uni, D.; Alabi, O.J. Cassava brown streak disease and Ugandan cassava brown streak virus reported for the first time in Zambia. Plant Dis. 2018, 102, 1410–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robson, F.; Hird, D.L.; Boa, E. Cassava brown streak: A deadly virus on the move. Plant Pathol. 2023, 73, 221–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, R.F.J. The brown streak disease of cassava: Distribution, climatic effects and diagnostic symptoms. East. Afr. Agr. J. 1950, 15, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillocks, R.J.; Raya, M.D.; Thresh, J.M. Distribution and symptom expression of cassava brown streak disease in southern Tanzania. East Afr. J. Root Tuber. Crops 1999, 3, 57–61. [Google Scholar]

- Bock, K.R. Studies on cassava brown streak disease in Kenya. Trop. Sci. 1994, 34, 134–145. [Google Scholar]

- Munganyinka, E.; Ateka, E.M.; Kihurani, A.W.; Kanyange, M.C.; Tairo, F.; Sseruwagi, P.; Ndunguru, J. Cassava brown streak disease in Rwanda, the associated viruses and disease phenotypes. Plant Pathol. 2018, 67, 377–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillocks, R.J.; Jennings, D.L. Cassava brown streak disease: A review of present knowledge and research needs. Int. J. Pest. Manag. 2003, 49, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruthi, M.N.; Kimata, B.; Masinde, E.A.; Mkamilo, G. Effect of time of harvesting and disease resistance in reducing Cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz) yield losses by two viral diseases. Mod. Concepts Dev. Agron. 2020, 6, 606–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndyetabula, I.L.; Merumba, S.M.; Jeremiah, S.C.; Kasele, S.; Mkamilo, G.S.; Kagimbo, F.M.; Legg, J.P. Analysis of interactions between cassava brown streak disease symptom types facilitates the determination of varietal responses and yield losses. Plant Dis. 2016, 100, 1388–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, I.U.; Ghosh, S.; Maruthi, M.N. Host and virus effects on reversion in cassava affected by cassava brown streak disease. Plant Pathol. 2016, 65, 593–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigirimana, S.; Barumbanze, P.; Ndayihanzamaso, P.; Shirima, R.R.; Legg, J.P. First report of cassava brown streak disease and associated Ugandan cassava brown streak virus in Burundi. New Dis. Rep. 2011, 24, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulimbi, W.; Phemba, X.; Assumani, B.; Kasereka, P.; Muyisa, S.; Ugentho, H.; Reeder, R.; Legg, J.P.; Laurenson, L.; Weekes, R.; et al. First report of Ugandan cassava brown streak virus on cassava in Democratic Republic of Congo. New Dis. Rep. 2012, 26, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casinga, C.M.; Wosula, E.N.; Sikirou, M.; Shirima, R.R.; Munyerenkana, C.M.; Nabahungu, L.N.; Bashizi, B.K.; Ugentho, H.; Monde, G.; Legg, J.P. Diversity and Distribution of Whiteflies Colonizing Cassava in Eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. Insects 2022, 13, 849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neuenschwander, P.; Hughes, J.; Ogbe, F.d’A.; Ngatse, J.M.; Legg, J.P. The occurrence the Uganda Variant of East African Cassava Mosaic Virus (EACMV-Ug) in western Democratic Republic of Congo and the Congo Republic defines the westernmost extent of the CMD pandemic in East/Central Africa. Plant Pathol. 2001, 51, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muengula-Manyi, M.; Nkongolo, K.K.; Bragard, C.; Tshilenge-Djim, P.; Winter, S.; Kalonji-Mbuyi, A. Incidence, Severity and Gravity of Cassava Mosaic Disease in Savannah Agro-Ecological Region of DR-Congo: Analysis of Agro-Environmental Factors. Am. J. Plant Sci. 2012, 3, 512–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisimwa, E.; Walangululu, J.; Bragard, C. Cassava Mosaic Disease Yield Loss Assessment under Various Altitude Agroecosystems in the Sud-Kivu Region, Democratic Republic of Congo. Tropicultura 2015, 33, 101–110. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon, A.G.O.; Bandyopadhyay, R.; Coyne, D.; Ferguson, M.; Ferris, R.S.B.; Hanna, R.; Hughes, J.; Ingelbrecht, I.; Legg, J.; Mahungu, N.; et al. Cassava: From a poor farmer’s crop to a pacesetter of African rural development. Chronica Hort. 2003, 43, 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- Bundi, M.; Kasoma, C.; Mbugua, F.; Williams, F.; Tambo, J.; Rwomushana, I. Cassava Brown Streak Disease: An Evidence notes on impacts and management strategies for Zambia. CABI 2022, 1, 45. [Google Scholar]

- Yabeja, J.W.; Manoko, M.L.K.; Legg, J.P. Comparing fresh root yield and quality of certified and farmer-saved cassava seed. Crop Prot. 2025, 187, 106932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jandrain, A. Politique semencière de la RDC: Politique importée, des bailleurs pour l’implémenter. Conj Afr. Cent. 2020, 1, 213–238. [Google Scholar]

- Masinde, E.A.; Ogendo, J.; Mkamilo, G.; Maruthi, M.N.; Hillocks, R.; Mulwa, R.M.S.; Arama, P.F. Occurrence and estimated losses caused by cassava viruses in Migori County, Kenya. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2016, 11, 2064–2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SENASEM. Catalogue National Variétal des Cultures Vivrières: Répertoire des variétés homologuées de plantes à racines, tubercules et du bananier. Min. Agr. 2019, 1, 124. [Google Scholar]

- Alicai, T.; Omongo, C.A.; Maruthi, M.N.; Hillocks, R.J.; Baguma, Y.; Kawuki, R.; Bua, A.; Otim-Nape, G.W.; Colvin, J. Re-emergence of cassava brown streak disease in Uganda. Plant Dis. 2007, 91, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogwok, E.; Ilyas, M.; Alicai, T.M.E.; Taylor, N.J. Comparative analysis of virus-derived small RNAs within cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz) infected with cassava brown streak viruses. Virus Res. 2016, 215, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centre de Recherche en Sciences Naturelles de Lwiro. Les données climatiques de la station météorologique de Civanga. CRSN-Lwiro 2022, 7, 35–47. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, I.P.; Abidrabo, P.; Miano, D.W.; Alicai, T.; Kinyua, Z.M.; Clarke, J.; Macarthur, R.; Weekes, R.; Laurenson, L.; Hany, U.; et al. High throughput real-time RTPCR assays for specific detection of cassava brown streak disease causal viruses and their application to testing planting material. Plant Pathol. 2013, 62, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirima, R.R.; Maeda, D.G.; Kanju, E.; Ceasar, G.; Tibazarwa, F.I.; Legg, J.P. Absolute quantification of cassava brown streak virus mRNA by real-time qPCR. J. Virol. Methods 2017, 245, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, D.R.; Gigliolli, A.A.; Falco, J.R.; Julio, A.H.; Volnistem, E.A.; Chagas, F.; Toledo, V.A.; Ruvolo-Takasusuki, M.C. Toxicity and effects of the neonicotinoid thiamethoxam on Scaptotrigona bipunctatalepeletier, 1836 (Hymenoptera: Apidae). Environ. Toxicol. 2018, 33, 463–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- French and European Standards. Norme NF X31-107. Available online: https://www.boutique.afnor.org/fr-fr/norme/nf-x31107/qualite-du-sol-determination-de-la-distribution-granulometrique-des-particu/fa124875/21997 (accessed on 12 March 2022).

- French and European Standards. ISO 11263: 1994—Soil Quality—Determination of Phosphorus—Spectrometric Determination of Phosphorus Soluble in Sodium Hydrogen Carbonate Solution. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/19241.html (accessed on 12 March 2022).

- French and European Standards. ISO 10390: 2021—Soil, Treated Biowaste and Sludge—Determination of pH. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/75243.html (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- French and European Standards. ISO 11261: 1995—Soil Quality—Determination of Total Nitrogen—Modified Kjeldahl Method. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/19239.html (accessed on 12 March 2022).

- Globalspex. AFNOR—NF X31-130—Soil Quality—Chemical Methods—Determination of Cationic Exchange Capacity (CEC) and Extractible Cations|GlobalSpec. Available online: https://standards.globalspec.com/std/675558/nf-x31-130 (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- Okul, V.A.; Ochwo-Ssemakula, M.; Kaweesi, T.; Ozimati, A.; Mrema, E.; Mwale, S.; Gibson, P.; Achola, E.; Edema, R.; Baguma, Y.; et al. Plot based heritability estimates and categorization of cassava genotype response to cassava brown streak disease. Crop Prot. 2018, 108, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gondwe, F.M.; Mahungu, N.M.; Hillocks, R.J.; Raya, M.D.; Moyo, C.C.; Soko, M.M.; Chipungu, F.P.; Benesi, I.R. Economic losses experienced by small-scale farmers in Malawi due to CBSVD. In Cassava Brown Streak Virus Disease: Past Present and Future, 1st ed., Proceedings of an International Workshop, Mombasa, Kenya, 27–30 October 2005; Legg, J., Hillocks, R., Eds.; Natural Resources International Limited: Aylesford, UK, 2002; Volume 1, pp. 28–36. [Google Scholar]

- Bakayoko, S.; Soro, D.; N’dri, B.; Kouadio, K.K.; Tschannen, A.; Nindjin, C.; Dao, D.; Girardin, O. Etude de l’architecture végétale de 14 variétés améliorées de manioc (Manihot esculenta Crantz) dans le centre de la Côte d’Ivoire. J. Appl. Biosci. 2013, 61, 4471–4477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillocks, R.; Maruthi, M.; Kulembeka, H.; Jeremiah, S.; Alacho, F.; Masinde, E.; Ogendo, J.; Arama, P.; Mulwa, R.; Mkamilo, G.; et al. Disparity between leaf and root symptoms and crop losses associated with cassava Brown streak disease in four countries in eastern Africa. J. Phytopathol. 2015, 164, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. Available online: https://www.R-project.org (accessed on 22 March 2025).

- Kruskal, W.H.; Wallis, W.A. Use of ranks in one-criterion variance analysis. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1952, 47, 583–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H.; Averick, M.; Bryan, J.; Chang, W.; McGowan, L.D.; François, R.; Grolemund, G.; Hayes, A.; Henry, L.; Hester, J.; et al. Welcome to the tidyverse. J. Open Source Softw. 2019, 4, 1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirima, R.R.; Maeda, D.G.; Kanju, E.E.; Tumwegamire, S.; Ceasar, G.; Mushi, E.; Sichalwe, C.; Mtunda, K.; Mkamilo, G.; Legg, J.P. Assessing the degeneration of cassava under high virus inoculum conditions in Coastal Tanzania. Plant Dis. 2019, 103, 2652–2664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Production Volume of Cassava in Thailand from 2016 to 2024 with a Forecast for 2025. Thailand: Production Volume of Cassava 2025|Statista. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1041126/thailand-cassava-production-volume/ (accessed on 17 January 2025).

- Fermont, A.M.; Van Asten, P.J.; Tittonell, P.; Van Wijk, M.T.; Giller, K.E. Closing the cassava yield gap: An analysis from smallholder farms in East Africa. Field Crops Res. 2009, 112, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahungu, N.; Ndonda, A.; Frangoie, A.; Moango, A. Effet du labour et du mode de bouturage sur les rendements en racines et en feuilles de manioc dans les zones de savane et de jachères forestières de la République Démocratique du Congo. Tropicultura 2015, 33, 176–185. [Google Scholar]

- Mondo, J.M.; Irenge, A.B.; Ayagirwe, R.B.B.; Dontsop-Nguezet, P.; Karume, K.; Njukwe, E.; Mapatano, S.M.; Zamukulu, P.M.; Basimine, G.C.; Musungayi, E.M.; et al. Determinants of Adoption and Farmers’ Preferences for Cassava Varieties in Kabare Territory, Eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. Am. J. Rural Dev. 2017, 7, 44–52. [Google Scholar]

- Munyahali, W.; Pypers, P.; Swennen, R.; Walangululu, J.; Vanlauwe, B.; Merckx, R. Responses of cassava growth and yield to leaf harvesting frequency and NPK fertilizer in South Kivu, Democratic Republic of Congo. Field Crops Res. 2017, 214, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mtunguja, M.K.; Henry, S.L.; Kanju, E.; Ndunguru, J.; Muzanila, Y.C. Effect of genotype and genotype by environment interaction on total cyanide content, fresh root, and starch yield in farmer-preferred cassava landraces in Tanzania. Food Sci. Nutr. 2016, 4, 791–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birindwa, D.R.; Van Laere, J.; Munyahali, W.; De Bauw, P.; Dercon, G.; Kintche, K.; Merckx, R. Early planting of cassava enhanced the response of improved cultivars to potassium fertilization in South Kivu, Democratic Republic of Congo. Field Crops Res. 2023, 296, 108903. [Google Scholar]

- Hillocks, R.J.; Raya, M.; Thresh, J.M. The association between root necrosis and above-ground symptoms of brown streak virus infection of cassava in southern Tanzania. Int. J. Pest. Manag. 1996, 42, 285–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukuru, B.N.; Archana, T.S.; Bisimwa, E.B.; Birindwa, D.R.; Sharma, S.; Kurian, J.A.; Casinga, C.M. Screening of cultivars against cassava brown streak disease and molecular identification of the phytopathogenic infection-associated viruses. Arch. Phytopathol. Plant Prot. 2022, 55, 1899–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawuki, R.S.; Kaweesi, T.; Esuma, W.; Pariyo, A.; Kayondo, I.S.; Ozimati, A.; Kyaligonza, V.; Abaca, A.; Orone, J.; Tumuhimbise, R.; et al. Eleven years of breeding efforts to combat cassava brown streak disease. Breed Sci. 2016, 66, 560–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nweke, F.I.; Spencer, D.S.C.; Lynam, J.K. The Cassava Transformation: Africa’s Best-Kept Secret, 1st ed.; Michigan State University Press: East Lansing, MI, USA, 2002; Volume 1, pp. 239–257. [Google Scholar]

- Wongnoi, S.; Banterng, P.; Vorasoot, N.; Jogloy, S.; Theerakulpisut, P. Physiology, Growth and Yield of Different Cassava Genotypes Planted in Upland with Dry Environment during High Storage Root Accumulation Stage. Agronomy 2020, 10, 576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbanzibwa, D.R.; Tian, Y.P.; Tugume, A.K.; Patil, B.L.; Yadav, J.S.; Bagewadi, B.; Abarshi, M.M.; Alicai, T.; Changadeya, W.; Mkumbira, J.; et al. Evolution of cassava brown streak disease-associated viruses. J. Gen. Virol. 2011, 92, 974–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fresco, L.O. Cassava in Shifting Cultivation. In A Systems Approach to Agricultural Technology Development in Africa in Experimental Agriculture; Royal Tropical Institute: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1986; Volume 24, pp. 265–266. [Google Scholar]

| Replications | pH | % N | P-Bray1 | Exchangeable Bases cmol/kg | CEC | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mg/kg | K | Ca | Mg | cmol/kg | |||

| I | 6.89 | 0.19 | 20.59 | 0.86 | 12.42 | 2.47 | 28.46 |

| II | 7.28 | 0.19 | 21.52 | 2.11 | 16.85 | 4.96 | 38.54 |

| III | 7.17 | 0.2 | 110.99 | 2.07 | 18.12 | 4.87 | 39.58 |

| IV | 7.01 | 0.2 | 67.03 | 1.55 | 15.37 | 4.25 | 35.1 |

| Average | 7.07 | 0.2 | 77.27 | 1.61 | 15.6 | 4.09 | 35.2 |

| Year 1 | Year 2 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 MAP | 6 MAP | 9 MAP | 12 MAP | Mean | 3 MAP | 6 MAP | 9 MAP | 12 MAP | Mean | |

| Height (cm) | ||||||||||

| Nabana Healthy | 46.30 (2.54) | 97.56 (4.35) | 160.84 (5.40) | 216.65 (4.88) | 130.3 c | 52.08 (3.39) | 88.25 (4.41) | 153.40 (5.19) | 204.43 (7.11) | 125 c |

| Nabana Infected | 34.35 (2.41) | 73.00 (4.05) | 120.30 (5.34) | 142.65 (5.72) | 92.6 d | 41.35 (3.83) | 78.22 (5.64) | 117.10 (6.12) | 168.72 (7.40) | 101 d |

| Sawasawa Healthy | 68.36 (3.53) | 120.29 (4.91) | 220.01 (7.94) | 274.46 (5.67) | 170.8 a | 86.50 (4.36) | 122.60 (4.58) | 201.07 (6.25) | 277.80 (8.88) | 172 a |

| Sawasawa Infected | 52.17 (2.88) | 118.30 (4.54) | 196.43 (7.36) | 263.57 (6.81) | 157.6 b | 60.62 (4.77) | 103.00 (6.14) | 162.30 (8.21) | 250.05 (7.33) | 144 b |

| Mean | 50.3 | 102.3 | 174.4 | 224.3 | 60.1 | 98.0 | 158.5 | 225.2 | ||

| CV (%) | 63.6 | 57.9 | ||||||||

| MSD MAP | 27.9 (***) | 23.4 (***) | ||||||||

| MSD Cassava Varieties | 6.36 (***) | 7.45 (***) | ||||||||

| MSD MAP × Cassava Varieties | 12.7 (***) | 14.9 (***) | ||||||||

| Diameter (cm) | ||||||||||

| Nabana Healthy | 0.76 (0.04) | 1.54 (0.08) | 2.18 (0.08) | 2.74 (0.07) | 1.80 b | 0.96 (0.05) | 1.43 (0.05) | 1.96 (0.08) | 2.56 (0.08) | 1.73 c |

| Nabana Infected | 0.62 (0.05) | 1.18 (0.06) | 1.85 (0.07) | 2.14 (0.08) | 1.45 c | 0.84 (0.07) | 1.33 (0.07) | 1.75 (0.08) | 2.47 (0.11) | 1.60 d |

| Sawasawa Healthy | 0.94 (0.06) | 1.78 (0.09) | 2.49 (0.10) | 3.05 (0.06) | 2.07 a | 1.25 (0.08) | 1.71 (0.08) | 2.24 (0.08) | 2.90 (0.09) | 2.03 a |

| Sawasawa Infected | 0.75 (0.05) | 1.88 (0.08) | 2.51 (0.10) | 3.16 (0.08) | 2.08 a | 0.96 (0.07) | 1.62 (0.09) | 2.10 (0.09) | 2.91 (0.07) | 1.90 b |

| Mean | 0.767 | 1.598 | 2.257 | 2.770 | 1.01 | 1.52 | 2.02 | 2.71 | ||

| CV (%) | 56.1 | 45.2 | ||||||||

| MSD MAP | 0.264 (***) | 0.245 (***) | ||||||||

| MSD Cassava Varieties | 0.0949 (**) | 0.097 (*) | ||||||||

| MSD MAP × Cassava Varieties | 0.19 (***) | 0.195 (ns) | ||||||||

| CBSD leaf score | ||||||||||

| Nabana Healthy | 1.00 (0.00) | 1.31 (0.08) | 1.29 (0.08) | 1.12 (0.05) | 1.18 b | 1.00 (0.00) | 1.27 (0.11) | 1.18 (0.10) | 1.25 (0.10) | 1.18 c |

| Nabana Infected | 2.88 (0.04) | 2.99 (0.08) | 2.71 (0.12) | 3.35 (0.08) | 2.98 a | 2.90 (0.06) | 2.90 (0.11) | 1.98 (0.13) | 3.52 (0.12) | 2.83 b |

| Sawasawa Healthy | 1.00 (0.00) | 1.35 (0.08) | 1.34 (0.09) | 1.10 (0.05) | 1.20 b | 1.00 (0.00) | 1.32 (0.12) | 1.10 (0.06) | 1.20 (0.09) | 1.16 c |

| Sawasawa Infected | 2.85 (0.04) | 3.05 (0.07) | 2.98 (0.06) | 3.08 (0.10) | 2.99 a | 2.77 (0.07) | 2.92 (0.08) | 2.85 (0.08) | 3.48 (0.11) | 3.01 a |

| Mean | 1.93 | 2.17 | 2.08 | 2.16 | 1.92 | 2.11 | 1.77 | 2.36 | ||

| CV (%) | 53.2 | 53.7 | ||||||||

| MSD MAP | 0.19 (***) | 0.244 (***) | ||||||||

| MSD Cassava Varieties | 0.097 (***) | 0.125 (***) | ||||||||

| MSD MAP × Cassava Varieties | 0.195 (***) | 0.25 (***) | ||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Casinga, C.M.; Shirima, R.R.; Kangela, A.; Wosula, E.N.; Bashizi, B.; Ugentho, H.U.; Nabahungu, L.N.; Monde, G.; Bamba, Z.; Kumar, L.; et al. Effects of Cassava Brown Streak Disease and Harvest Time on Two Cassava Mosaic Disease-Resistant Varieties in Eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2891. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122891

Casinga CM, Shirima RR, Kangela A, Wosula EN, Bashizi B, Ugentho HU, Nabahungu LN, Monde G, Bamba Z, Kumar L, et al. Effects of Cassava Brown Streak Disease and Harvest Time on Two Cassava Mosaic Disease-Resistant Varieties in Eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo. Agronomy. 2025; 15(12):2891. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122891

Chicago/Turabian StyleCasinga, Clerisse M., Rudolph R. Shirima, Alain Kangela, Everlyne N. Wosula, Benoit Bashizi, Henry U. Ugentho, Leon N. Nabahungu, Godefroid Monde, Zoumana Bamba, Lava Kumar, and et al. 2025. "Effects of Cassava Brown Streak Disease and Harvest Time on Two Cassava Mosaic Disease-Resistant Varieties in Eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo" Agronomy 15, no. 12: 2891. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122891

APA StyleCasinga, C. M., Shirima, R. R., Kangela, A., Wosula, E. N., Bashizi, B., Ugentho, H. U., Nabahungu, L. N., Monde, G., Bamba, Z., Kumar, L., & Legg, J. P. (2025). Effects of Cassava Brown Streak Disease and Harvest Time on Two Cassava Mosaic Disease-Resistant Varieties in Eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo. Agronomy, 15(12), 2891. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122891