1. Introduction

Intensifying crop production to meet the growing global demands for food, fiber, and bioenergy requires, among other measures, greater fertilizer use to raise yields on already cleared lands, thereby helping to conserve remaining natural vegetation [

1]. This reliance on nitrogen fertilizers, however, brings a persistent challenge that is low nitrogen use efficiency (NUE), typically below 50% in many commercial crops [

2]. This limitation is particularly relevant for cereals just as maize, which accounts for about 40% of global cereal production [

3].

The fraction of N fertilizer not taken up by crops has severe environmental consequences. It contributes to biodiversity loss, the formation of fine particulate matter (PM

2.5) that degrades air quality, and stratospheric ozone depletion through the release of volatile N oxides. It also increases atmospheric warming via emissions of N

2O, a potent greenhouse gas [

4]. This latter effect is especially important given the urgency to limit the global warming to 1.5 °C [

5]. Beyond these environmental concerns, inefficient fertilization also has implications for production costs and crop yields. Countries dependent on importing N fertilizers are particularly vulnerable to economy oscillations that can severely restrict imports, with serious consequences for soil health and agricultural production [

6]. Such vulnerability underscores the need for approaches that reduce dependence on synthetic N inputs and enhance the efficiency at which N is used by crops.

The current challenges related to N fertilization call for additional strategies to improve NUE, beyond the 4R stewardship that is likely already adopted in many countries. The application of plant growth-promoting bacteria (PGPB) or even fungi as bioinputs has emerged as a sustainable strategy to enhance the utilization of soil resources in an integrated approach, as discussed for N and P by Adesemoye and Kloepper [

7]. A key demonstration of PGPB as part of an integrated fertilization strategy was provided by Hungria et al. [

8], who reported positive results using selected strains of

Azospirillum brasilense inoculated into wheat and maize in Brazil, concluding that this technology could allow reductions in N fertilization rates by up to 50%. This not only lowers production costs but also mitigates the environmental impacts associated with excessive N application.

Among the PGPB,

A. brasilense has been extensively studied for its beneficial effects on cereals, although results vary depending on the bacterial strain and the environmental conditions [

9]. Regarding N fertilization, the use of a combination of

A. brasilense strains Ab-V5 and Ab-V6 in inoculants has demonstrated significant improvements in maize biomass, grain yield, and NUE, particularly under conditions of reduced N fertilization [

8]. The use of such strains has increased the

15N-based urea recovery in maize shoots to as much as 58%, compared with 34% in non-inoculated controls [

10]. Another bacterial species that has been effectively used as a PGPB is

Nitrospirillum viridazoti strain BR 11145 (=CBAmC), reclassified from

N. amazonense and previously known as

Azospirillum amazonense. This species, which has maize among its hosts [

11], has also been shown to promote sugarcane growth [

12].

Some strains of PGPB exhibit genomic profiles directly associated with denitrification. For example,

A. brasilense is an aerophilic bacterium capable of fixing N

2, but it can also survive under anaerobic conditions by using alternative electron acceptors to O

2, since it carries the complete set of genes involved in the denitrification pathway [

13]. This implies that it has the capacity to produce N

2O in the presence of nitrate or other intermediate N oxides, but also to reduce N

2O to N

2. In contrast,

N. viridazoti is also capable of fixing N

2, but it exhibits a more limited denitrification capacity, primarily associated with the presence of only the

nosZ gene, which encodes the enzyme nitrous oxide reductase [

11]. This genomic trait suggests a potential greater ability to reduce N

2O rather than contribute to its production.

To date, specific studies evaluating the impact of inoculation with A. brasilense strains or N. viridazoti on N2O emissions from N-fertilized crops are scarce or even lacking. This knowledge gap highlights the need for experiments designed to assess whether inoculation with these strains can alter N2O fluxes under controlled and field conditions, which was the objective of the present study. Accordingly, the pot experiment focused on isolating the direct effects of bacterial inoculation under controlled soil and moisture conditions, whereas the field experiment evaluated whether similar effects could be observed under agronomically realistic management.

2. Materials and Methods

The study included

Azospirillum brasilense [

14] strains Ab-V5 and Ab-V6, which are recommended for the inoculation of several crops in Brazil, including maize [

7], as well as

Nitrospirillum viridazoti [

11] strain BR 11145 (=CBAmC), which is commercially recommended for sugarcane in Brazil. In addition,

A. brasilense strain Wa3 was included to explore possible contrasting effects, a strain that was studied as potential inoculants for several grasses including maize [

15].

Two experiments were carried out, with one in pots under controlled conditions to evaluate the effect of inoculation with the strains of A. brasilense (Ab-V5 and Ab-V6, and Wa3) and of N. viridazoti (BR 11145) to a soil treated with N fertilizer on N2O emissions. A second experiment was conducted under field conditions, where inoculants prepared with A. brasilense strains Ab-V5 and Ab-V6 and N. viridazoti strain BR 11145 were applied to maize fertilized with urea.

2.1. Pot Experiment

This first study served as proof of concept for the use of these bacteria as a potential strategy to mitigate N2O emissions from fertilized soils. The pot experiment was conducted under controlled conditions at Embrapa Agrobiologia (Seropédica, RJ, Brazil) from 16 February to 16 April 2025 to evaluate N2O emissions following N application in soils treated with different microbial inoculants. The soil used in the study was collected from the 0–20 cm layer of a Typic Hapludult, and presented the following chemical properties: pHH2O 6.0; total C 0.98%, Al3+ 0.00 cmolc dm−3; Ca2+ 3.91 cmolc dm−3; Mg2+ 2.11 cmolc dm−3; K+ 86.9 mg dm−3; P (Mehlich I) 9.1 mg dm−3. It is a sandy-loam with 18% clay. The collected soil was shade-dried, sieved through a 1 mm mesh, and thoroughly homogenized.

Each pot was filled with 70 g of soil, adopting a procedure aiming at maintaining uniform porosity among treatments. Briefly, identical pots were filled with 60 mL of water and externally marked at the water level to delimit this volume. The pots were then emptied and dried with tissue paper. From this, 70 g of soil were transferred into each pot and gently tapped to achieve uniform compaction until the soil surface matched the water-level mark (see

Supplementary Materials Figure S1). This procedure resulted in a bulk density of 1.17 g cm

−3 and was adopted to standardize porosity and bulk density across pots, a critical aspect for gas studies where soil structure strongly influences gas diffusion and emission dynamics.

Seven treatments with four replicates each were established: (1) control without medium and without N addition, (2) BP medium (BP glycerol medium) without N addition, (3) BP sucrose medium (sucrose replacing glycerol) without N addition, (4) 50 ppm of N, (5) strain BR 11145 + 50 ppm N, (6) strain Wa3 + 50 ppm N and (7) a combination of strains Ab-V5 and Ab-V6 + 50 ppm N. The treatments receiving only BP media were included to evaluate whether the organic and inorganic components of the media could stimulate soil bacterial activity and consequently increase background N2O fluxes.

After pot preparation, each pot was gently watered with 21 mL of one of the following solutions: water alone, water with N, or growth medium with or without N. For the treatments receiving only N, the 21 mL volume consisted of 16 mL of water plus 5 mL of KNO3 solution, providing a final N concentration of 50 ppm on a soil basis. A 50 μL aliquot of either growth medium or bacterial culture was added to the water or to the water + N solution, according to the treatment. An additional 50 μL of water was applied to the pots receiving only water or water + N to equalize the final volume to 21 mL across all treatments. The flasks with 21 mL solution were manually stirred to ensure homogenization.

For inoculant preparation, bacterial strains were first grown on solid media in Petri dishes. NFb medium was used for

A. brasilense, while LGI medium was used for

N. viridazoti [

16], with incubation at 28–30 °C. Colonies were then transferred to test tubes containing 5 mL of the respective liquid medium and maintained on a shaker for 2 days at 28–30 °C. Subsequently, cultures were scaled up in 50 mL Erlenmeyer flasks (

A. brasilense strains in BP glycerol medium and

N. viridazoti in BP sucrose medium [

17];

Supplementary Materials Table S1) and shaken until reaching an optical density of 1.5–2.0 absorbance units using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Shimadzu UV-1280, Kyoto, Japan). Bacterial populations were on the order of 10

8 cells mL

−1, and culture purity was also verified.

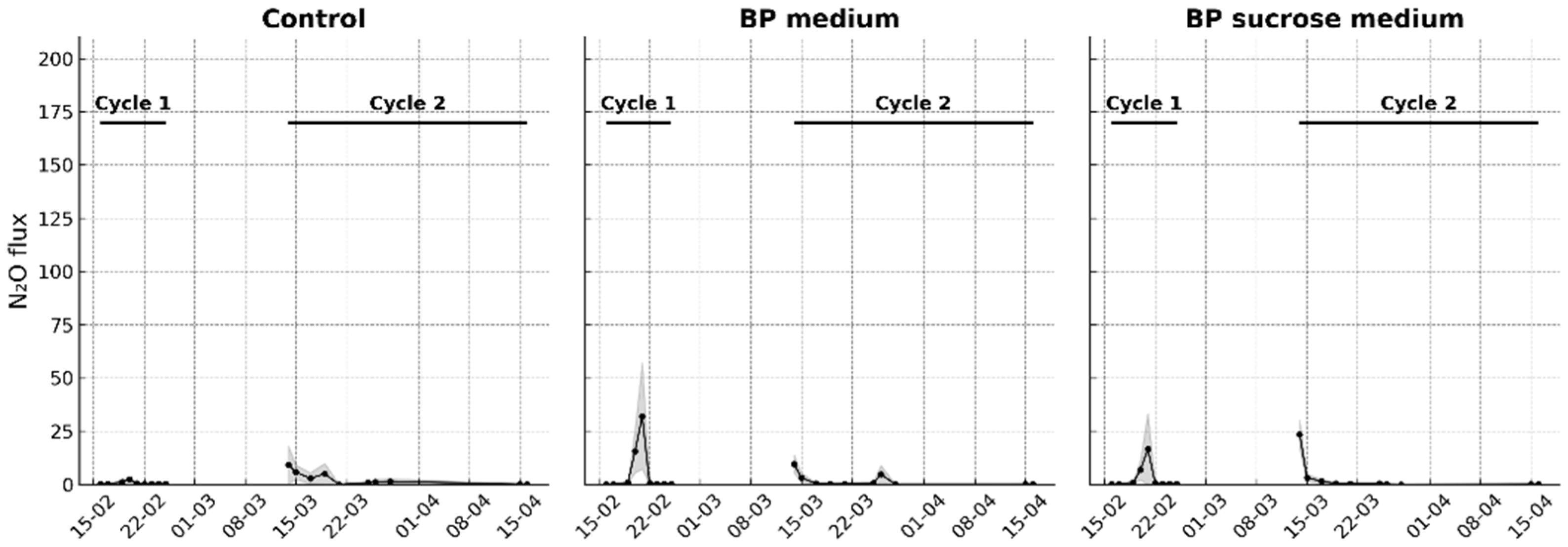

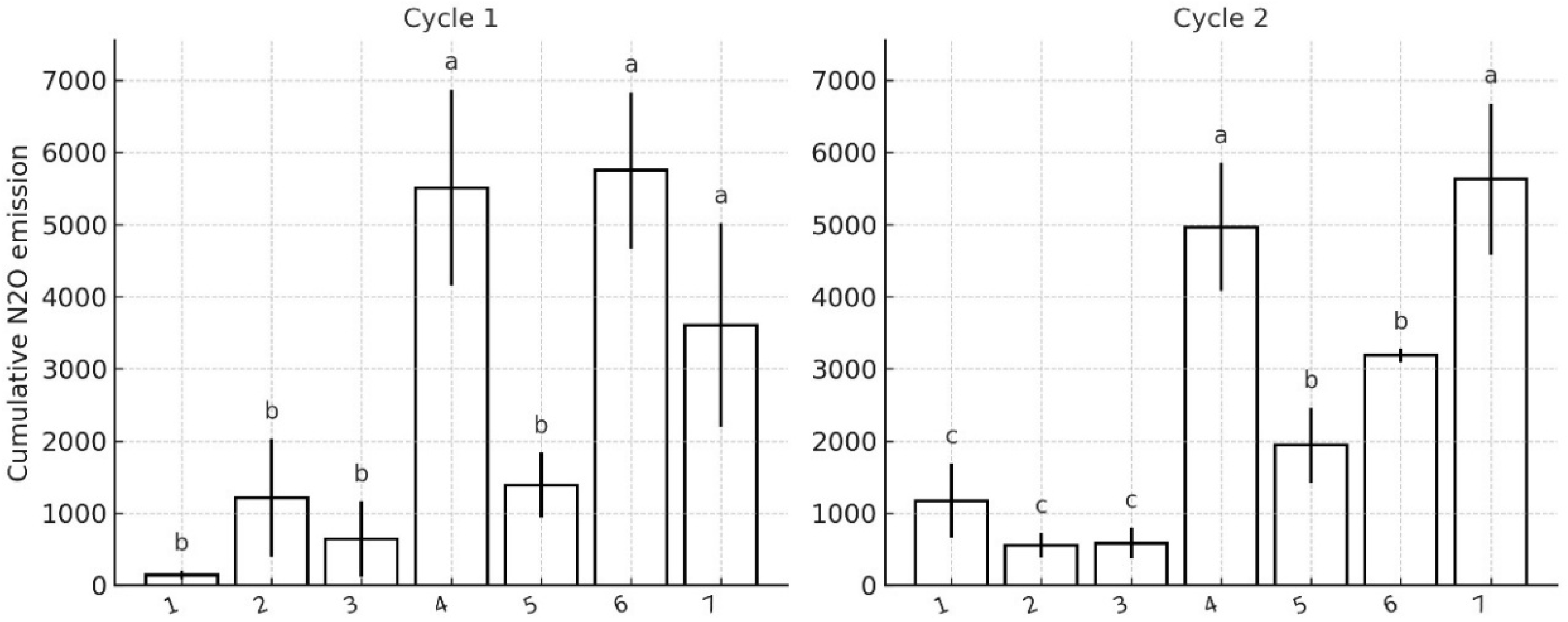

Nitrous oxide monitoring began immediately after the treatment application to the respective pots and continued for 10 days, after which it was paused because water addition was no longer inducing N2O fluxes above those of the control. This interval was maintained to allow the soil to stabilize before rewetting, since the experiment was structured around distinct wetting events rather than continuous monitoring. We called this first monitoring period as Cycle 1. During the subsequent 15-day pause, pearl millet (Pennisetum glaucum var. BRS 1501) was sown (five seeds per pot), seedlings emerged, and were thinned to two per pot. At the end of this interval, the treatments were reapplied, and gas monitoring was resumed two days later, marking the beginning of Cycle 2. The soil moisture level in each pot was maintained by daily weighing and adding water to reach 80% of the water-filled pore space. Ambient air temperature was monitored for use in the N2O flux calculation.

Fluxes of N2O were measured with an off-axis integrated cavity output spectroscopy analyzer (ABB LGR-ICOS, Los Gatos, CA, USA). For each measurement, a pot was placed inside a 2.5 L glass jar fitted with inlet and outlet ports connected to the analyzer, forming a closed dynamic loop that continuously recirculated the headspace air. After a 2 min stabilization period, the linear increase in N2O over a 2 min interval was used to calculate flux from each pot, expressed as μg N2O-N g−1 dry soil h−1. The first three measurements served as baselines (soil + water only). Beginning with the fourth, the full set of treatments was included.

For each sampling date, N2O flux observations were available as replicate measurements within each treatment. For every treatment, we computed the arithmetic mean and the standard error of the mean (SEM). The predefined gap between cycles (no samples collected) was excluded from calculations.

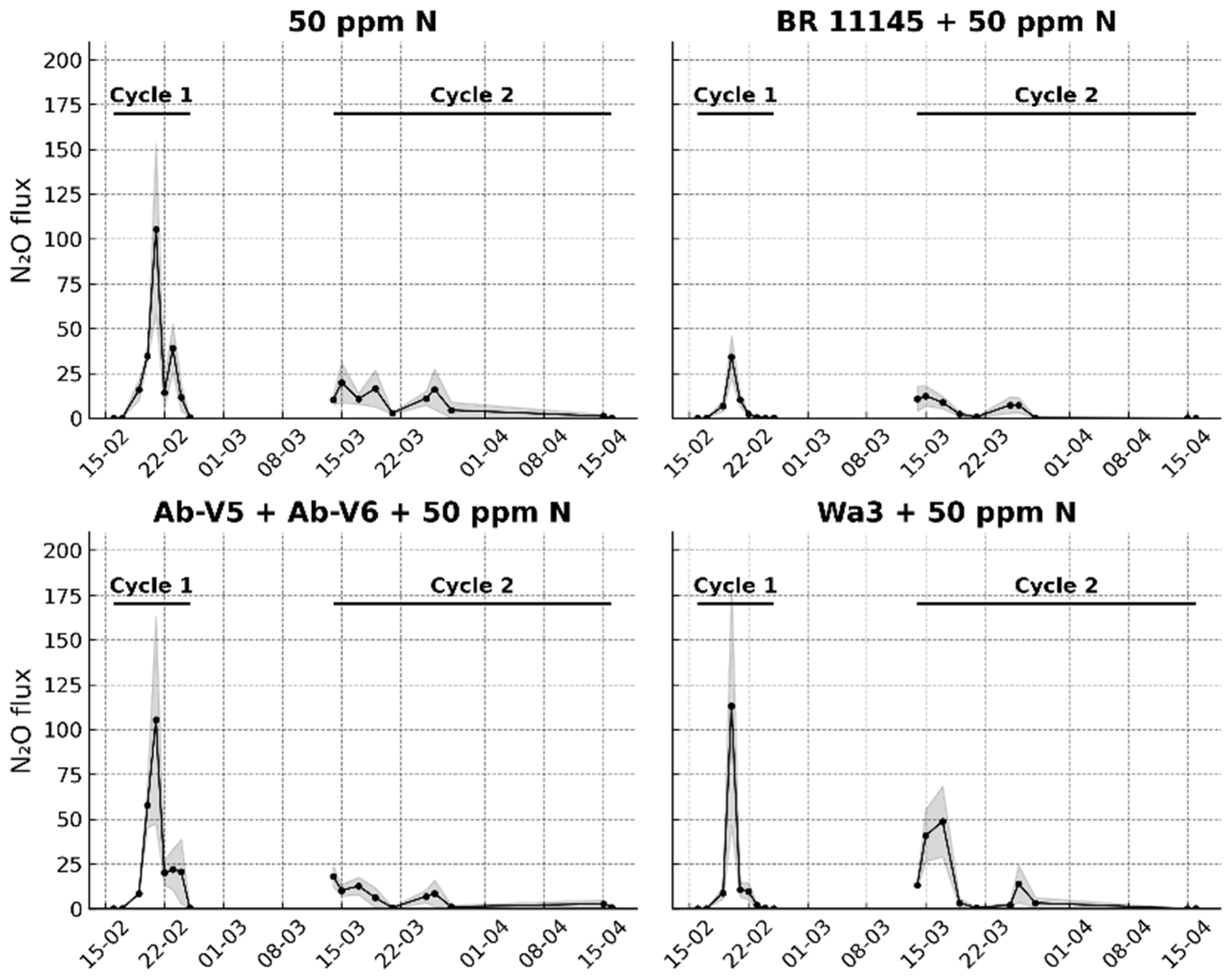

Cumulative N2O emissions for each treatment and replicate were calculated using the trapezoidal rule, which integrates fluxes over time by estimating the area under the curve between consecutive sampling points. This approach accounts for irregular time intervals between measurements. Integrated values were expressed as mg N2O-N pot−1 cycle−1, considering the pot’s dry soil mass. Treatment means and SEM were then computed from the pot-level totals.

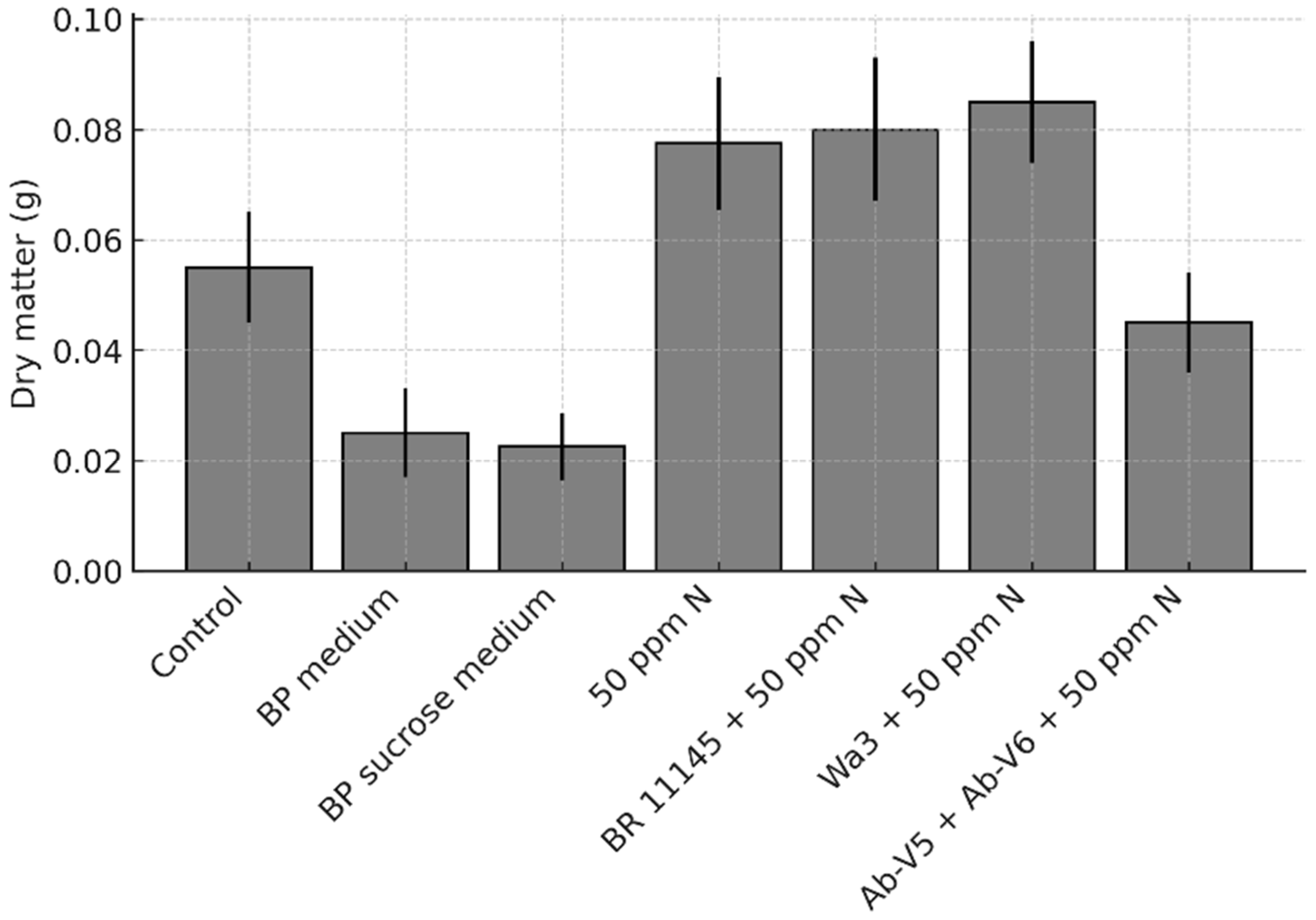

The pearl millet plants grown in pots during Cycle 2 were collected and oven-dried at 65 °C to determine their dry matter content.

2.2. Field Experiment

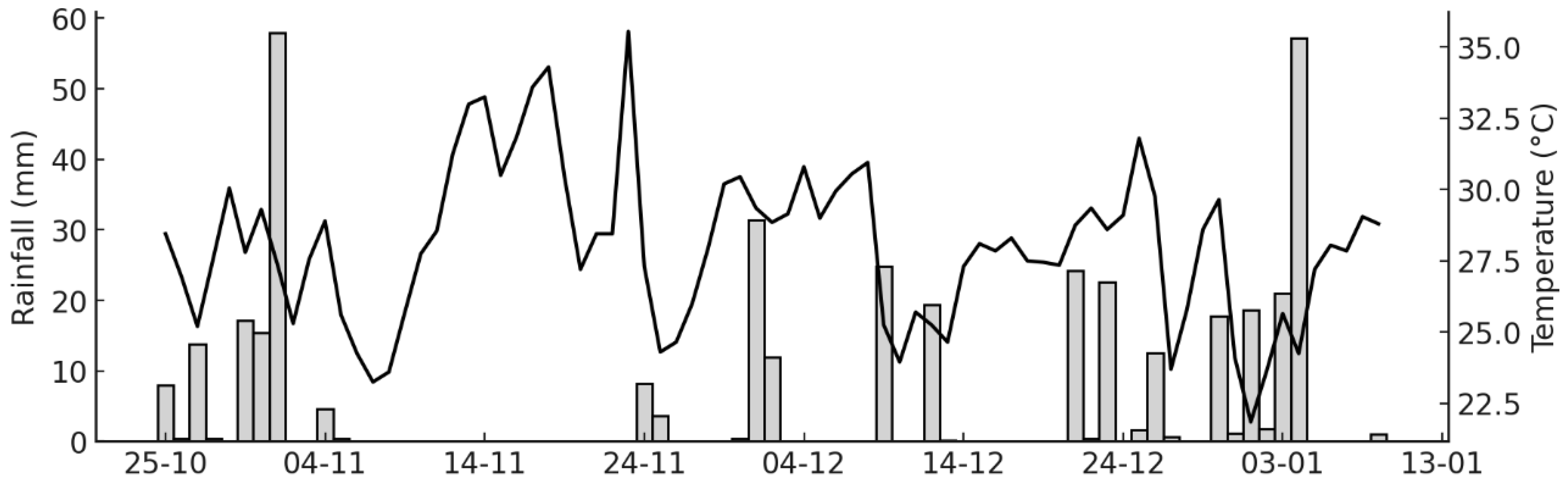

This second experiment was carried out as a field trial in an experimental area of the Fluminense Federal Institute of Education, Science and Technology (IFF), in Bom Jesus de Itabapoana, Rio de Janeiro State. The city lies in the northwestern region of the State, at 21°08′02″ S and 41°40′47″ W, at an altitude of 88 m, with an Aw climate (tropical savanna, sub-humid to dry). The mean annual temperature ranges from 22 to 25 °C, and mean annual precipitation is 1200–1300 mm. The soil in the area was relatively flat and presented a loamy texture being classified as an Oxisol. Soil samples collected from the 0–20 cm layer showed the following chemical properties prior to experimental setup: pHH2O 5.02; Al3+ 0.25 cmolc dm−3; H + Al 3.50 cmolc dm−3; Ca2+ 2.14 cmolc dm−3; Mg+2 0.89 cmolc dm−3; K+ 32.3 mg dm−3; P (Mehlich I) 4.12 mg dm−3. A meteorological station at the Institute continuously recorded daily rainfall and air temperature data, which was the data source for the field experiment.

A single-factor experiment comprised five treatments: (1) Control (without N applied), (2) Urea-N applied either at 82.5 kg N ha−1 (Urea-N 82.5) or (3) at 165 kg N ha−1, (4) Urea-N 82.5 + seed inoculation with A. brasilense strains Ab-V5 and Ab-V6, and (5) Urea-N 82.5 + seed inoculation with N. viridazoti strain BR 11145. The treatments fertilized with N corresponded to the side-dressing application. Each inoculant contained approximately 108 cells mL−1 and was mixed to maize seed at 3 mL kg−1 immediately before sowing.

The treatments were arranged in a randomized complete block design with four replicates. Each experimental plot comprised six 8 m rows spaced 0.5 m apart, with a seeding density of 3–4 plants per linear meter, sown at a depth of 2.5 cm. The two outermost rows served as guard rows, and the first and last 1 m of each row were also used as borders.

Conventional tillage was used, consisting of one plowing followed by two harrowing, producing a clod-free seedbed that enabled proper sowing and facilitated seedling emergence. The maize (Zea mays L.) cultivar RB7510 VIP3 (KWS), recommended for grain production, was used as the reference crop.

After soil preparation, fertilization and corn seeding were carried out using a sowing machine. Fertilization applied to seedbed consisted of 166 kg ha−1 of monoammonium phosphate (MAP), 133 kg ha−1 of K2O, and 20 kg ha−1 of fritted trace elements. At 23 days after emergence, a side-dress application of urea was performed, corresponding to the N fertilization treatments.

The monitoring of N

2O fluxes was carried out for all treatments, except for the one receiving 165 kg N ha

−1 and was initiated the day after side-dress fertilization using the closed static chamber technique [

18].

The chambers consisted of a metal frame measuring 40 × 60 cm with a soil insertion depth of 10 cm, featuring a trough along the upper edge. The lower edge of the frame was inserted into the soil so that its side walls penetrated the soil until the trough rested on the soil surface. Chamber bases were installed after maize seeding, one per experimental plot, positioned in the interrow space. A known amount of N-fertilizer equivalent to the N rate used in side-dressing was applied inside the chamber base according to each treatment. Chamber deployment was performed daily between 9:00 and 11:00 am during gas monitoring. The chamber top was fitted to the base by insertion into the trough, with sealing achieved by adding water to the trough. The top had the same dimensions as the base, with a height of 23 cm. It was covered with an adhesive aluminum foil mantle to serve as thermal insulation for the chamber. The upper side of the chamber top was sealed and equipped with a three-way valve, through which headspace gas samples were collected at 20 min intervals for 1 h after chamber deployment. Headspace gas sampling was performed using a 60 mL polypropylene syringe. Before sample collection, the valve connections were flushed with 10 mL of chamber air, after which 40 mL were withdrawn and retained in the syringe. Following sampling of all chambers, 25 mL of the syringe content were transferred to 20 mL evacuated chromatography vials sealed with chlorobutyl septa, immediately prior to air transfer. The vials were sent to Embrapa Agrobiology for N2O concentration analysis in a GC-2010 gas chromatograph (Shimadzu GC-2010, Kyoto, Japan) and subsequent soil flux calculations, which were expressed as μg N2O-N m−2 h−1. Fluxes were calculated from the linear increase in N2O concentration over time inside the chambers.

Cumulative N

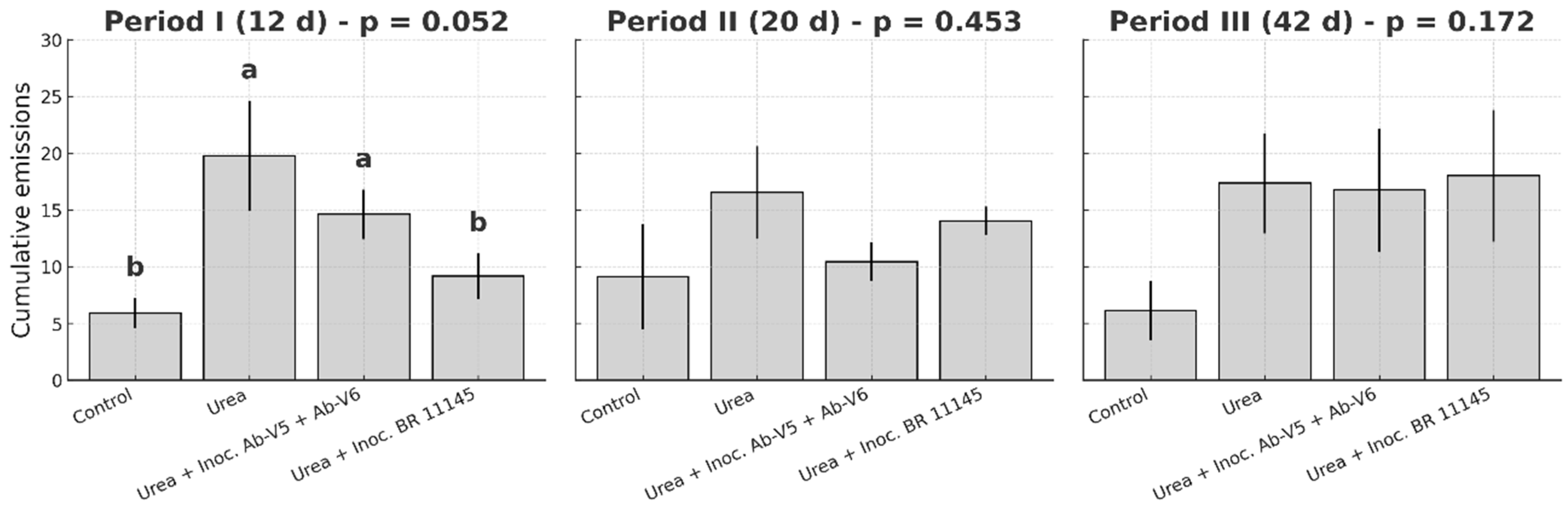

2O emissions were calculated as the area under the flux-time curve using the trapezoidal rule. Apart from integrating the whole time series, fluxes were also integrated with a boundary-aware trapezoidal rule within pre-defined windows counted from the first sampling day. This was performed based on the understanding that, in tropical environments, the highest N

2O fluxes induced by N fertilization typically occur within the first weeks following the onset of rainfall, and tend to level off thereafter [

19]. Therefore, the proposed inoculants are likely to have their greatest impact in the first weeks after N fertilization. To avoid placing cut points on non-sampled calendar days, each nominal boundary was “snapped” to the first sampling date on or after the target day. The experimental timeline was divided into three distinct periods: Period I-the first 12 days; Period II-the subsequent 20 days; and Period III-the remaining duration of the study. When a trapezoid straddled a window edge, flux values at the edge were linearly interpolated from adjacent measurements and only the overlapping fraction was integrated.

To calculate the fraction of added N converted into N2O, emissions were integrated over the entire experimental period. Net N2O emissions were determined by subtracting the cumulative emissions from the control treatment from those of each fertilized treatment. The resulting values were then divided by the amount of N applied as fertilizer to estimate the proportion of fertilizer-derived N lost as N2O.

Maize plants were harvested at maturity to determine grain yield, as well as thousand-kernel weight, number of kernel rows per ear, and ear dimensions (diameter and length), in order to assess soil responses to N fertilization and the possible effects of inoculation on plant growth promotion.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

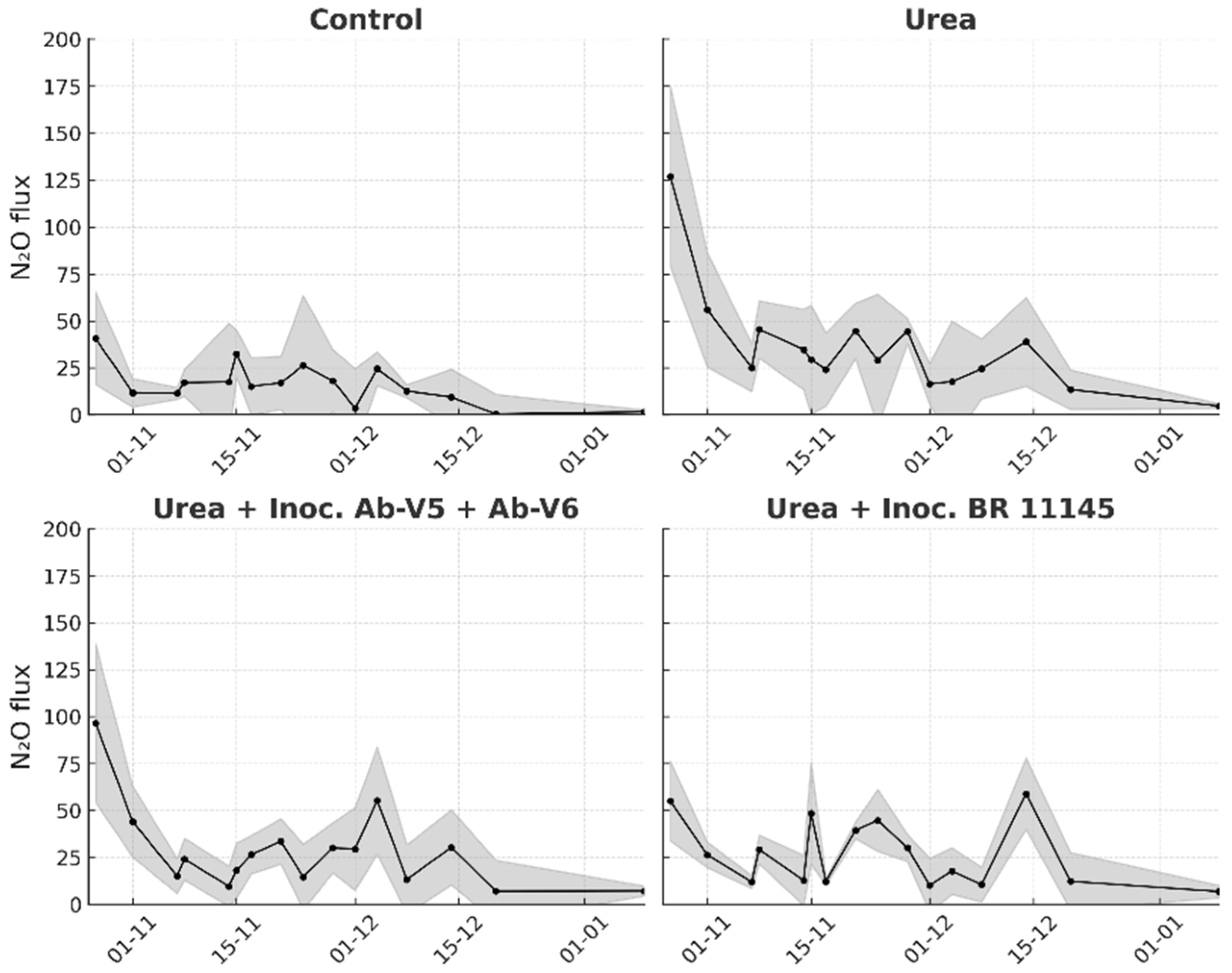

Regardless of the specific experiments, descriptive statistics of the instantaneous N2O fluxes were used to plot their variation over the monitoring period. Each plot displays a dark central line representing the mean, surrounded by a shaded envelope indicating the standard error of the mean.

For the pot experiment, all statistical analyses were performed with seven treatments and four replicated pots per treatment. Because the experiment comprised two measurement periods with distinct biological contexts, we treated Cycle 1 (soil without plants) and Cycle 2 (soil with plants) as separate analyses. The two cycles are displayed as disconnected data series (no line connecting cycles). Axes were harmonized within and across panels to facilitate visual comparison. For each cycle, a one-way ANOVA with treatment as the fixed effect on cumulative emissions was used. When the F test was significant (p < 0.05), means were separated using Fisher’s LSD test for pairwise mean comparisons. Normality and homogeneity of variances were assessed on model residuals by Shapiro–Wilk’s test and Levene’s test, respectively.

In the field experiment, cumulative emissions within each time window were analyzed using a randomized complete block design. Normality and homogeneity of variances were assessed based on model residuals, following standard procedures. When the F-test was significant at p < 0.05 or marginally significant at p < 0.10, Fisher’s LSD test was applied to separate treatment means.

Analyses were conducted and figures were produced using the Python (v.3.13, 2025) programming language and the packages Pandas (v2.2.3, 2024), SciPy (v1.16.0, 2025), and NumPy (v2.3.0, 2025) for data processing, and Matplotlib (v3.10.0, 2024) for panel visualization.

4. Discussion

This study evaluated the potential of associative, plant growth-promoting bacteria, already used in commercial inoculants for N-fertilized grain crops and carrying the

nosZ gene, as an approach to mitigate soil N

2O emissions. This process is generally attributed either to the total or partial replacement of fertilizer-derived N by symbiotic bacteria, or to the enhanced N uptake of plants whose growth is stimulated by phytohormones and other complementary mechanisms provided by the inoculated bacteria [

20,

21]. However, the capacity of some associative bacteria, already used as commercial inoculants, to reduce N

2O to N

2 represents an additional pathway through which gas emissions can be mitigated, an overlooked potential that could be exploited to lessen the environmental impact of N fertilization.

In the present study, direct soil inoculation was adopted in the pot experiment to maximize early contact between the inoculant and the soil environment, which is typical in controlled-environment mechanistic studies. In contrast, seed inoculation was used in the field because it reflects the standard application method recommended for commercial inoculants and aligns with common farmer practice.

The pot experiment of this study provided robust evidence of an N

2O mitigation effect, both in the presence and absence of a plant sink, particularly when

N. viridazoti strain BR 11145 was included in the inoculant. Indeed, this was the first study to provide proof of concept that

N. viridazoti can consume N

2O under soil conditions, which supports Baldani et al. [

11], who described the genomic profile of this species as containing only the

nosZ gene, responsible for the enzymatic reduction of N

2O to N

2. It is important to note that the consistently low N

2O production observed in pots containing

N. viridazoti was not detected in those inoculated with

A. brasilense strains Ab-V5 + Ab-V6, and was only weakly expressed with strain Wa3.

The field applicability of plant growth-promoting bacteria depends largely on their ability to survive in the soil after inoculation, and the same applies to their potential N

2O-reducing effect. In this study, the population of inoculated bacteria in the soil was not monitored over time. However, previous research with root-associative bacteria like those used here has shown that these organisms can maintain, or even increase, their populations relative to the initial inoculum and may persist in bare soil at relatively high densities for several weeks. Their survival is strongly influenced by soil characteristics such as organic matter, nitrogen and clay contents, and especially by water availability [

22]. Indeed, water has been identified as a key factor capable of extending bacterial survival beyond 20 days, with populations of

A. brasilense and

A. amazonense (now

N. viridazoti) remaining above 10

4 cells g

−1 of soil under adequate moisture [

23]. These findings suggest that, in our pot experiment, where soil moisture was replenished daily, the inoculated bacteria were likely maintained at relatively high densities for several weeks, even during the first monitoring cycle when plants were absent. This is consistent with evidence that bacterial populations remain high when plants are present and supported by root exudates [

22]. Although the cited studies used the same bacterial species but not the same strains, their results reinforce the confidence that the variation observed in N

2O fluxes in the current experiment was indeed driven by the inoculated bacteria.

The complete denitrification pathway in

A. brasilense [

13] may enable both N

2O production and consumption, with the predominance of either process depending on factors that regulate denitrification. There is experimental evidence that

A. brasilense, but strain Sp7, exhibits oxygen-sensitive N

2O reduction, which means it can reduce N

2O in the presence of O

2, but at a substantially lower rate than under anoxic conditions [

24]. In this regard, Sanford et al. [

25] analyzed the genomes of bacteria from diverse environments, including agricultural soils, and revealed an unexpectedly high diversity of

nosZ genes in these soils. In that study, functional

nosZ was found in many non-denitrifying bacteria that lacked key denitrification genes such as

nir and

nor, a profile like that of

N. viridazoti. The so-called atypical

nosZ genes were shown to form a distinct phylogenetic lineage, later recognized as Clade II, which differs structurally and functionally from the classical

nosZ Clade I found in typical denitrifiers such as

Azospirillum,

Pseudomonas and

Bradyrhizobium [

26]. The contrasting kinetic behavior of

nosZ clades, as demonstrated by Yoon et al. [

27], provides a physiological basis for their distinct ecological roles. Bacteria of Clade I exhibit high maximum N

2O reduction rates but low affinity for N

2O, and their activity is strongly inhibited by oxygen. In contrast, those of Clade II show slower maximum rates but a much higher affinity for N

2O and greater tolerance to O

2, allowing them to function effectively under low N

2O concentrations and microaerobic conditions.

In the pot experiment of the present study, the restricted soil volume likely caused greater fluctuations in water content, although it was not continuously monitored but measured once a day, when water was added to maintain the target soil moisture level. Such conditions may have favored the prevalence of N

2O-consuming microorganisms more adapted to these fluctuations, particularly those classified within Clade II. Although a

nosZ clade affiliation of

N. viridazoti has not yet been formally determined, its genomic profile, containing solely the

nosZ gene and lacking the other denitrification genes, suggests an alignment with Clade II that gathers broader environmental tolerance and higher N

2O-reduction efficiency [

28]. Consequently, one hypothesis is that

A. brasilense may act as a transient N

2O source under certain soil conditions, whereas

N. viridazoti consistently functions as an effective biological sink for N

2O.

Apart from the increased variability that is commonly observed in field N

2O monitoring, the results obtained during the first two weeks, when the effects of N fertilization on the gas fluxes are most consistently detected, especially following rainfall events [

19], demonstrated a clear reduction in N

2O emissions when

N. viridazoti was inoculated to maize. The similar magnitude of N

2O emissions observed during period II (calculated for 20 days) and period III (calculated for 42 days) indicates a declining daily flux, suggesting that fertilization was acting as only a minor stimulus for N

2O production. Under tropical conditions, N

2O fluxes induced by N fertilization typically persist for no longer than two to three weeks [

19], which coincides with the period during which inoculated bacterial population are more likely to persist in soil and root systems [

22,

23]. The differences in inoculation procedures may have contributed to the magnitude of results between pot and field experiments, particularly because seed inoculation leads to stronger dependence on rhizosphere colonization and environmental conditions that influence early bacterial survival and establishment as discussed earlier.

As a potential field strategy, the marginal significance in N

2O mitigation observed in the inoculated treatments was not fully reflected in the corresponding direct N

2O emission factors when compared with non-inoculated treatments. The way EF is calculated, requiring integration of emissions over the entire crop cycle, substantially increases variability, which likely masked statistically significant differences among treatments. Despite this, the temporal emission patterns clearly indicated a mitigation effect, which was not fully captured by the cumulative EF metric even though an apparent 15% reduction was estimated with the use of both inoculants. This is far from the N

2O mitigation levels reported by Hiis et al. [

29] in Norway following soil inoculation with

Cloacibacterium sp., another Clade II representative, which may be attributed to the contrasting experimental conditions. Their study was carried out under more controlled conditions, with high inoculum loads delivered through an organic carrier substrate. However, the environmental impact of even more modest reductions could be substantial, considering that a large proportion of the nearly 10 million tons of N applied as fertilizers in South America corresponds to maize, wheat, and sugarcane crops, which are potential targets for commercial

Azospirillum and

Nitrospirillum inoculants aimed at promoting plant growth.

In this study, inoculation did not significantly affect plant growth or yield. Under controlled conditions, plant growth was inherently limited, preventing statistical significance and revealing only a trend in response to N addition, with no detectable effect of inoculation. A similar pattern was observed in the field experiment, where neither N fertilization nor inoculation increased yield, suggesting that other factors constrained crop performance. Although rainfall was generally adequate, prolonged dry spells, one lasting about 20 days and others of 7 to 10 days, combined with high temperatures, may have restricted growth, and limiting yield. The experimental site and available infrastructure also restricted additional measurements, such as root biomass and N accumulation which prevented us from assessing potential physiological benefits commonly associated with plant growth-promoting bacteria. Galindo et al. [

30] reported that

A. brasilense inoculation in maize modestly increased grain yield (7%) but significantly enhanced N uptake, emphasizing its potential to improve the sustainability of maize production in tropical regions. Likewise, studies involving

N. viridazoti (referred to as

A. amazonense at that time) inoculation in maize showed greater root biomass and N accumulation, indicating improved nutrient uptake efficiency [

31].

Because inoculation did not affect plant growth or N uptake in either experiment, plant-mediated mechanisms cannot explain the observed reductions in N2O emissions. Instead, the mitigation patterns, consistently lower fluxes in the N. viridazoti treatment and, to a lesser extent, in A. brasilense, are more plausibly attributed to the denitrification capacity of these strains. In particular, the isolated presence of the nosZ gene in N. viridazoti provides a mechanistic explanation for its stronger mitigation effect. This interpretation is consistent with the temporal flux dynamics observed and with previous reports on the functional potential of these bacteria.