Seed Coatings as Biofilm Micro-Habitats: Principles, Applications, and Sustainability Impacts

Abstract

1. Introduction

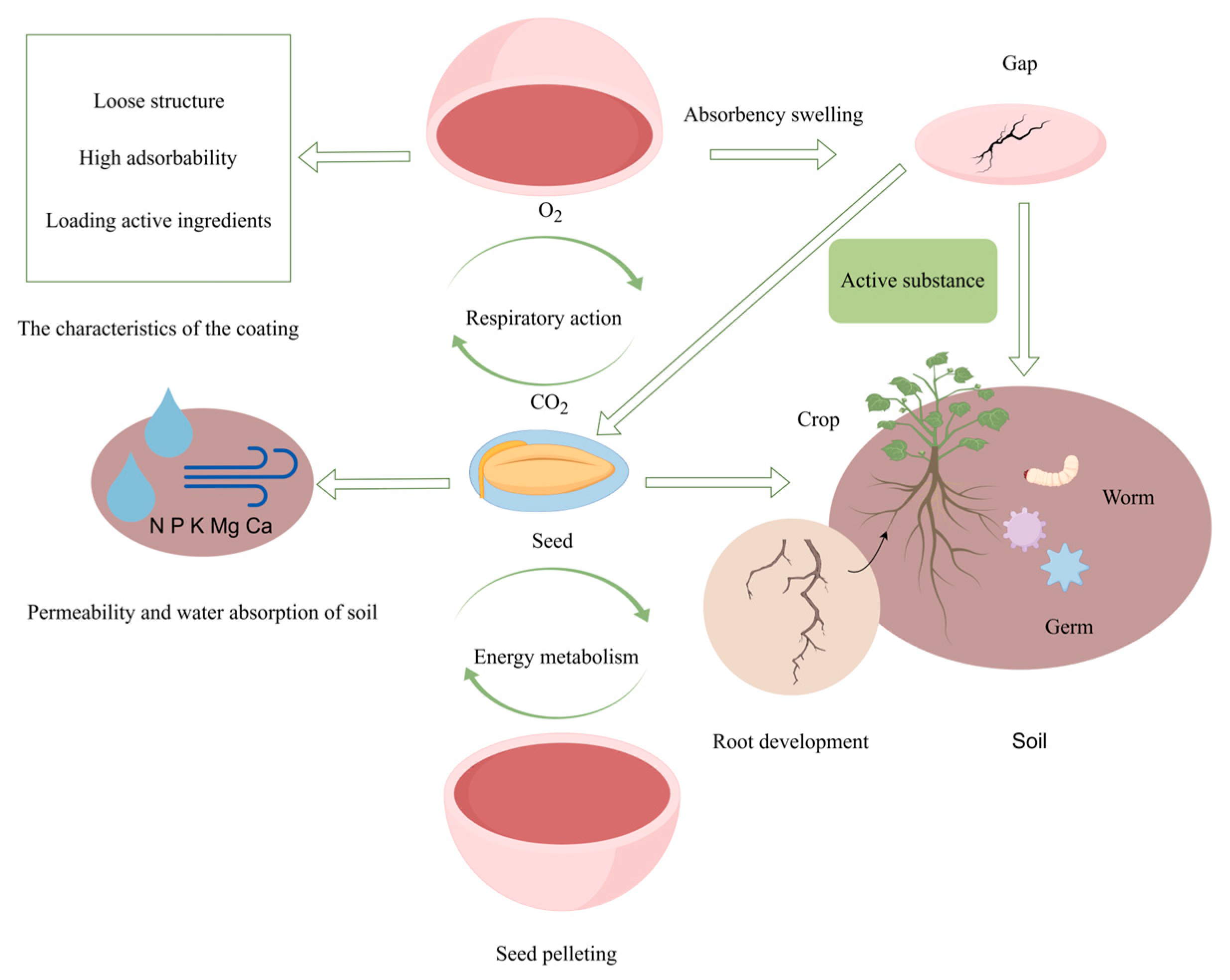

2. Seed Coatings: From Inert Carriers to Living Biofilm Micro-Habitats

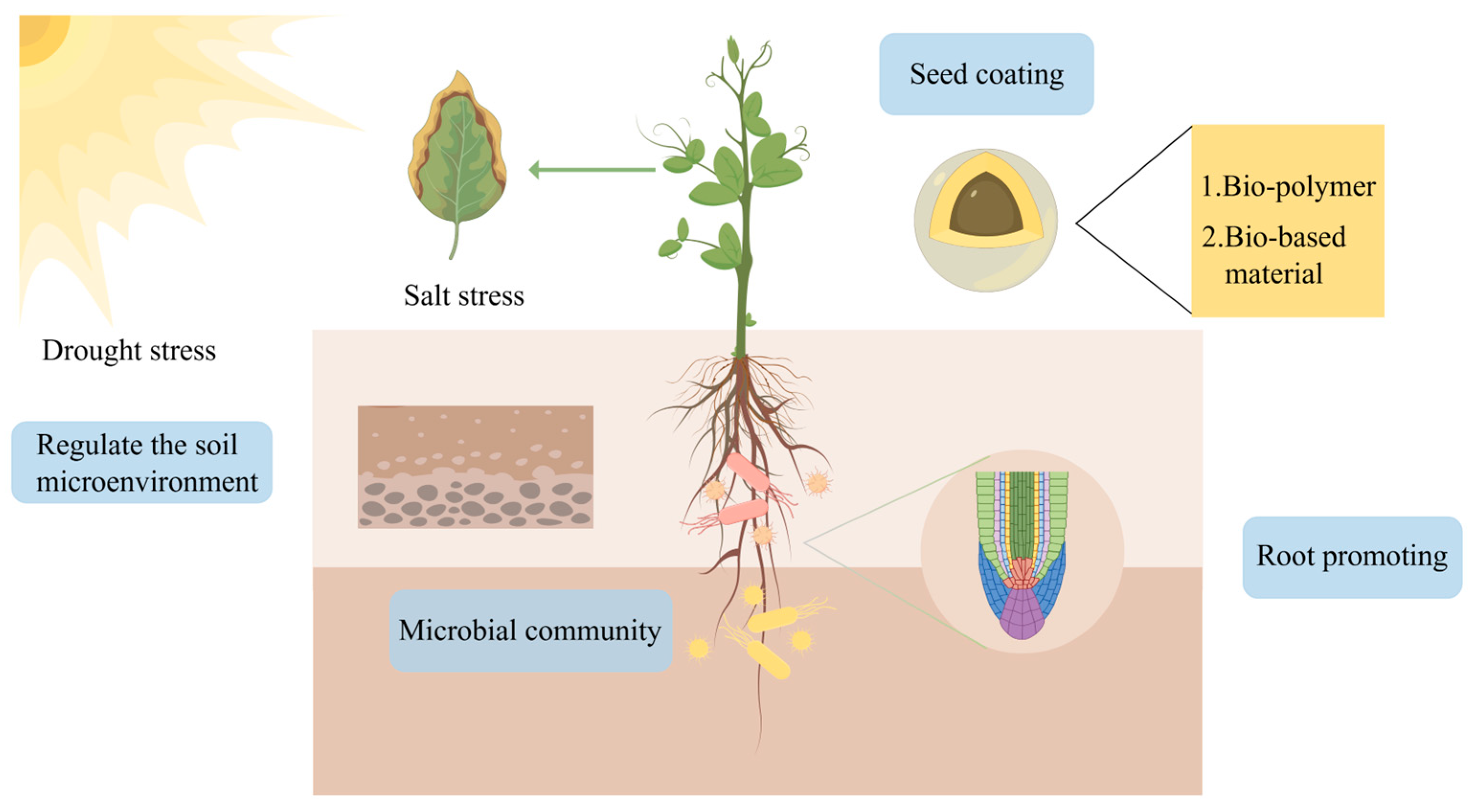

3. Fundamental Principles of Biofilm Microhabitat Establishment

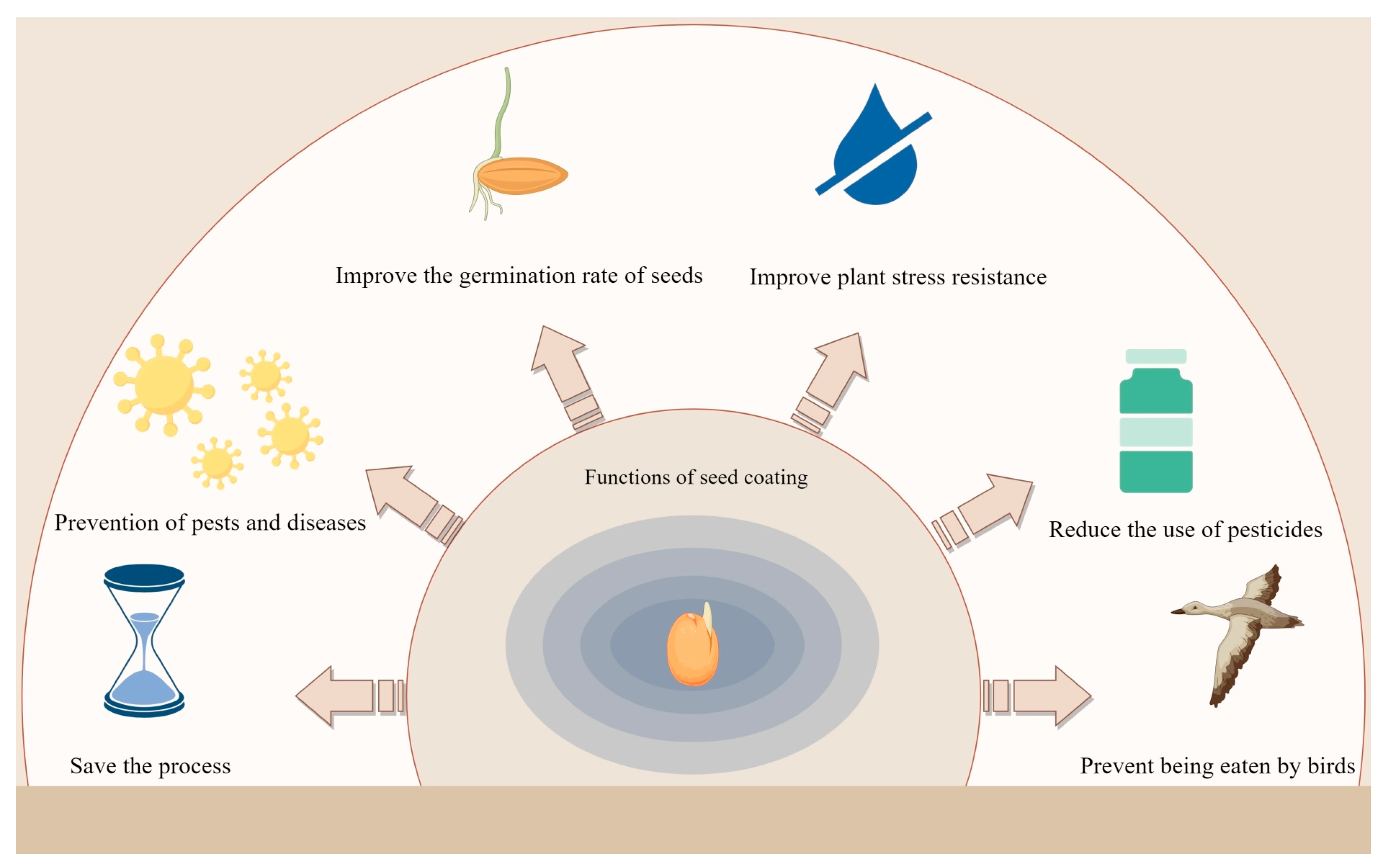

4. Multifunctional Roles of Biofilm Micro-Habitats in Crop Growth

4.1. Save Processes and Physical Protection

4.2. Nutrient Mobilization and Growth Promotion

4.3. Biocontrol and Immune Induction

4.4. Stress Resilience and Abiotic Stress Alleviation

4.5. Soil Amendment and Ecological Remediation

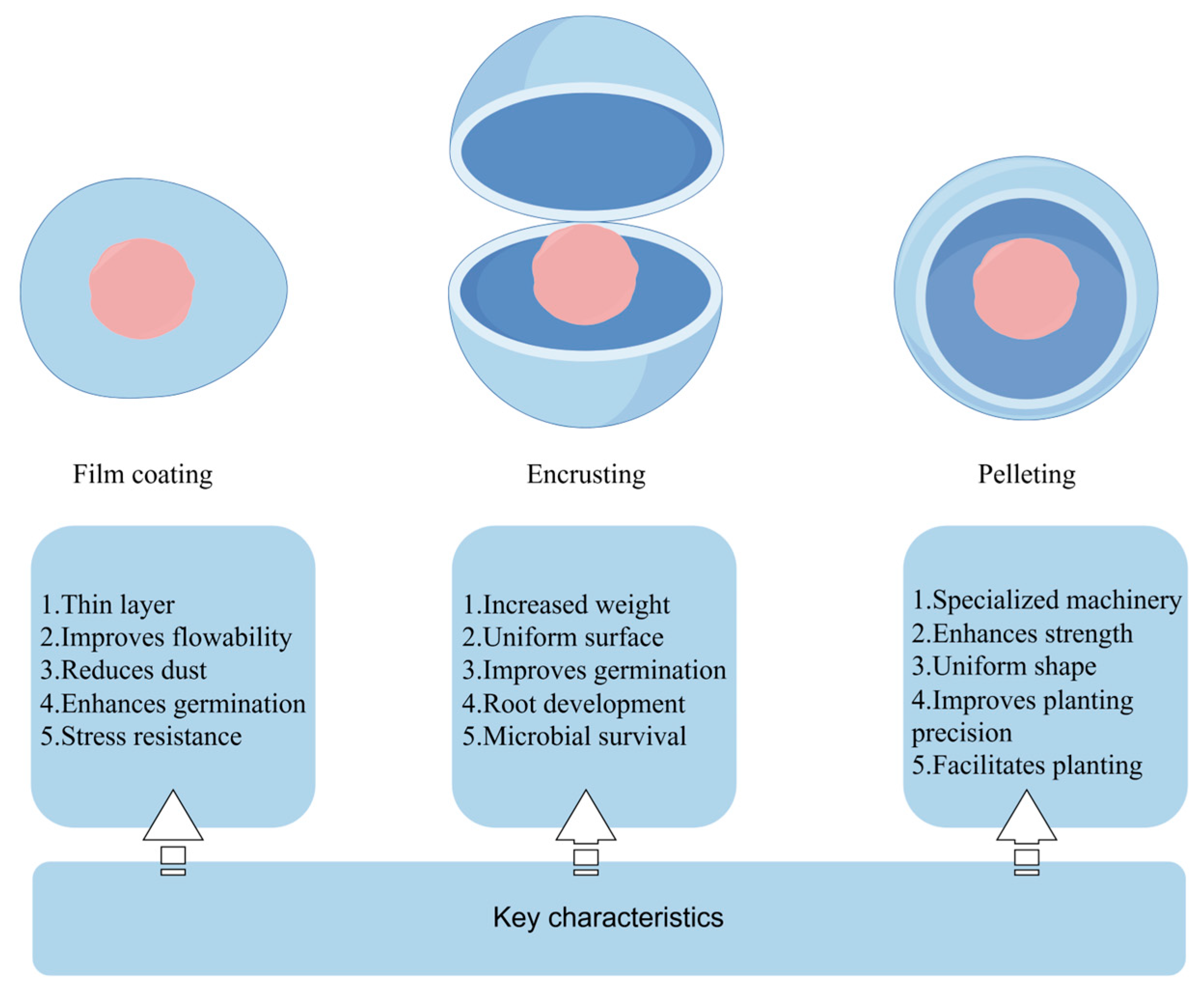

5. Three Methods of Seed Coating

6. Applications of Seed Coating Across Different Crop Types

6.1. Cereal Crops

6.2. Vegetable Crops

6.3. Oil Crops

7. Discussion

7.1. Sustainability Contributions

7.2. Key Challenges and Constraints

7.3. Pathways Forward

8. Future Perspectives and Concluding Remarks

8.1. Advancing Smart Coating Materials

8.2. Harnessing Microbial Synergies Through Systems Biology

8.3. Integrated Life-Cycle and Resilience Assessment

8.4. Promoting Inclusive and Adaptive Innovation

8.5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PGPR | Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria |

| ISR | Induced Systemic Resistance |

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| H2O2 | Hydrogen Peroxide |

References

- Franzino, T.; Boubakri, H.; Merlin, L.; M’Sakni, A.; Droux, M.; Mermillod-Blondin, F.; Moënne-Loccoz, Y.; Bendahmane, M.; Szécsi, J.; Haichar, F.e.Z. Carbon source utilization regulates biofilm formation and plant-beneficial interactions of Pseudomonas ogarae F113. iScience 2025, 28, 113639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thakur, R.; Yadav, S. Exopolysaccharides and biofilm forming microbial inoculant AB-13 acting in a consortium promotes growth of economically important medicinal plant Catharanthus roseus. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 319, 145122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, E.; Teixeira, J.A.; Pereira, M.O.; Rocha, C.M.R.; Sousa, A.M. Evolving biofilm inhibition and eradication in clinical settings through plant-based antibiofilm agents. Phytomedicine 2023, 119, 154973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Narayanan, M.; Shi, X.; Chen, X.; Li, Z.; Ma, Y. Biofilms formation in plant growth-promoting bacteria for alleviating agro-environmental stress. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 907, 167774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çam, S.; Küçük, Ç.; Almaca, A. Bacillus strains exhibit various plant growth promoting traits and their biofilm-forming capability correlates to their salt stress alleviation effect on maize seedlings. J. Biotechnol. 2023, 369, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haq, M.Z.U.; Bai, Z.; Gu, G.; Liu, Y.; Yang, D.; Yang, H.; Yu, J.; Wu, Y. Continuous cropping obstacles in medicinal plants: Driven by soil microbial communities and root exudates. A review. Plant Sci. 2025, 359, 112686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Liang, Q.; Wang, G. Soil moisture influences wheat yield by affecting root growth and the composition of microbial communities under drip fertigation. Agric. Water Manag. 2024, 305, 109102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arellano-Wattenbarger, G.L.; Córdoba-Agudelo, M.; Rocha, J. Ancestral roots: Exploring microbial communities in traditional agroecosystems for sustainable agriculture. Geoderma Reg. 2025, 41, e00960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Feng, Y.; Dang, K.; Jiang, Y.; Qi, H.; Feng, B. Linkages of microbial community structure and root exudates: Evidence from microbial nitrogen limitation in soils of crop families. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 881, 163536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanikawa, T.; Maie, N.; Fujii, S.; Sun, L.; Hirano, Y.; Mizoguchi, T.; Matsuda, Y. Contrasting patterns of nitrogen release from fine roots and leaves driven by microbial communities during decomposition. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 855, 158809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, O.; Li, L.; Duan, G.; Gustave, W.; Zhai, W.; Zou, L.; An, X.; Tang, X.; Xu, J. Root exudates increased arsenic mobility and altered microbial community in paddy soils. J. Environ. Sci. 2023, 127, 410–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, T.; Yu, G.-H.; Hong, W.-D.; Yuan, J.; Niu, G.-Q.; Xie, P.-H.; Sun, F.-S.; Guo, L.-D.; Kuzyakov, Y.; Shen, Q.-R. Root exudate chemistry affects soil carbon mobilization via microbial community reassembly. Fundam. Res. 2022, 2, 697–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magaña Ugarte, R.; Hurtado Martínez, M.; Díaz-Santiago, E.; Pugnaire, F.I. Microbial controls on seed germination. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2024, 199, 109576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhao, K.; Stirling, E.; Wang, X.; Gao, Z.; Ma, B.; Xu, C.; Chen, S.; Chu, G.; Zhang, X.; et al. Heterosis of endophytic microbiomes in hybrid rice varieties improves seed germination. mSystems 2024, 9, e00004-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corredor-Perilla, I.C.; Cuervo Andrade, J.L.; Olejar, K.J.; Park, S.-H. Beneficial properties of soil bacteria from Cannabis sativa L.: Seed germination, phosphorus solubilization and mycelial growth inhibition of Fusarium sp. Rhizosphere 2023, 27, 100780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrika, K.S.V.P.; Prasad, R.D.; Prasanna, S.L.; Shrey, B.; Kavya, M. Impact of biopolymer-based Trichoderma harzianum seed coating on disease incidence and yield in oilseed crops. Heliyon 2024, 10, e38816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Wang, X.; Deng, Q.; Wang, H.; Luo, B.; Tang, T. Modified red clay with calcium carbonate: Experimental testing and mechanical characterisation. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Ground Improv. 2025, 178, 138–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Cao, M.; Shi, X.; Chen, X.; Li, Z.; Ma, Y. Mitigating salt stress in Zea mays: Harnessing Serratia nematodiphila-biochar-based seed coating for plant growth promotion and rhizosphere microecology regulation. Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 223, 120164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, T.; Afzal, I.; Shabbir, R.; Ikram, K.; Saqlain Zaheer, M.; Faheem, M.; Haider Ali, H.; Iqbal, J. Seed coating technology: An innovative and sustainable approach for improving seed quality and crop performance. J. Saudi Soc. Agric. Sci. 2022, 21, 536–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yu, X.; He, H.; Zhu, W.; Yuan, X.; Wang, H. Engineering high-performance and multifunctional seed coating agents from lignocellulosic components. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 222, 119768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fertahi, S.; Elhaissoufi, W.; Bargaz, A.; Touchaleaume, F.; Habibi, Y.; Oukarroum, A.; Zeroual, Y.; Barakat, A. Lignin-rich extracts as slow-release coating for phosphorus fertilizers. Prog. Org. Coat. 2024, 190, 108394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, P.; Kumari, N.; Mohan, C.; Chinglenthoiba, C.; Amesho, K.T.T. Environmentally benign approach to formulate nanoclay/starch hydrogel for controlled release of zinc and its application in seed coating of Oryza sativa plant. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 257, 128278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Accinelli, C.; Abbas, H.K.; Little, N.S.; Kotowicz, J.K.; Mencarelli, M.; Shier, W.T. A liquid bioplastic formulation for film coating of agronomic seeds. Crop Prot. 2016, 89, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, C.-M.; Kim, J.; Choi, O.; Kim, S.H.; Park, C.S. Improvement of biological control capacity of Paenibacillus polymyxa E681 by seed pelleting on sesame. Biol. Control 2006, 39, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Jain, A.; Sarma, B.K.; Upadhyay, R.S.; Singh, H.B. Rhizosphere competent microbial consortium mediates rapid changes in phenolic profiles in chickpea during Sclerotium rolfsii infection. Microbiol. Res. 2014, 169, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Amirkhani, M.; Mayton, H.; Chen, Z.; Taylor, A.G. Biostimulant Seed Coating Treatments to Improve Cover Crop Germination and Seedling Growth. Agronomy 2020, 10, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosini, D.; Adamou, M.; Tchindebe, G.; Goudoungou, J.W.; Fotso, T.G.; Moukhtar, M.; Nukenine, E.N. Insecticidal potential of diatomaceous earth against Callosobruchus maculatus (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) infesting stored cowpea, Bambara groundnut and soybean in the Sudano-Guinean climatic conditions of Cameroon. J. Stored Prod. Res. 2025, 111, 102533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, M.G.; Emira, H.S.; Ahmed, N.M. Empowering the anticorrosive coatings performance via employing ZnO.CoO @ sand core-shell pigment. Prog. Org. Coat. 2025, 199, 108947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrini, S.; Merritt, D.J.; Stevens, J.; Dixon, K. Seed Coating: Science or Marketing Spin? Trends Plant Sci. 2017, 22, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzal, A.; Bano, A.; Fatima, M. Higher soybean yield by inoculation with N-fixing and P-solubilizing bacteria. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 30, 487–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, I.; Ma, Y.; Souza-Alonso, P.; Vosátka, M.; Freitas, H.; Oliveira, R.S. Seed Coating: A Tool for Delivering Beneficial Microbes to Agricultural Crops. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yousuf, S.; Maktedar, S.S. Exploring the use of quince seed mucilage as novel coating material for enhancing quality and shelf-life of fresh apples during refrigerated storage. Sustain. Food Technol. 2024, 2, 1527–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahedi, Y.; Zandi, M.; Bimakr, M. Effect of Balangu seed mucilage/gelatin coating containing dill essential oil and ZnO nanoparticles on sweet cherry quality during cold storage. Heliyon 2024, 10, e41057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, X.; Zhang, J.; Cheng, T.; Guo, Y.; Han, X.; Liu, H.; Qin, Y.; Li, J.; Xiang, D. Preparation of Tartary Buckwheat Seed Coating Agent and Its Effect on Germination. Phyton-Int. J. Exp. Bot. 2024, 93, 699–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrini, S.; Balestrazzi, A.; Madsen, M.D.; Bhalsing, K.; Hardegree, S.P.; Dixon, K.W.; Kildisheva, O.A. Seed enhancement: Getting seeds restoration-ready. Restor. Ecol. 2020, 28, S266–S275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kangsopa, J.; Hynes, R.K.; Siri, B. Lettuce seeds pelleting: A new bilayer matrix for lettuce (Lactuca sativa) seeds. Seed Sci. Technol. 2018, 46, 521–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohail, M.; Pirzada, T.; Opperman, C.H.; Khan, S.A. Recent advances in seed coating technologies: Transitioning toward sustainable agriculture. Green Chem. 2022, 24, 6052–6085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauer, M.; Hansen, A.L.; Manderyck, B.; Olsson, Å.; Raaijmakers, E.; Hanse, B.; Stockfisch, N.; Märländer, B. Neonicotinoids in sugar beet cultivation in Central and Northern Europe: Efficacy and environmental impact of neonicotinoid seed treatments and alternative measures. Crop Prot. 2017, 93, 132–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krupke, C.H.; Long, E.Y. Intersections between neonicotinoid seed treatments and honey bees. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 2015, 10, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, K.; Cheng, Q.; Zeng, C.; Shen, H.; Lu, C. The fate and transport of pesticide seed treatments and its impact on soil microbials. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2025, 290, 117508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Xiong, W.; Zhang, C.; Wang, D.; Zhou, C.; Li, W.; Zeng, G.; Song, B.; Zeng, Z. Neonicotinoid insecticides in non-target organisms: Occurrence, exposure, toxicity, and human health risks. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 383, 125432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Chen, L.; Wang, J.; Wang, L.; Han, B.; Li, Y.; Yu, L.; Liu, W. Neonicotinoid metabolites in farmland surface soils in China based on multiple agricultural influencing factors: A national survey. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 483, 136633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, A.; Khan, M.A.; Mashlawi, A.M.; Kumar, A.; Rahayuningsih, S.; Wuryantini, S.; Endarto, O.; Gusti Agung Ayu Indrayani, I.; Suhara, C.; Rahayu, F.; et al. Environmental contaminants and insects: Genetic strategies for ecosystem and agricultural sustainability. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 982, 179660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rydz, J. Sustainability and Environmental Degradability of Synthetic Polymers. In Encyclopedia of Green Chemistry, 1st ed.; Török, B., Ed.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2025; pp. 144–153. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, B.; Iqbal, J.; Marwat, S.; Ahmad, M.N.; Khan, A.A.; Jabbir, F.; Aziz, T.; Alghamdi, S.A.; Alamri, A.S.; Alhomrani, M. Sorption and desorption of bisphenol A on agricultural soils and its implications for surface and groundwater contamination. Desalin. Water Treat. 2025, 322, 101180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, K.A.; Geary, B.; Allen, P.S.; Hulet, A.; Gunnell, K.L.; Landeen, M.; Nelson, S.V.; Johansen, S.K.; McKee, C.T.; Madsen, M.D. Improving Winterfat Seedling Emergence Using Hydrophobic Seed Coatings. Rangel. Ecol. Manag. 2025, 103, 288–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paravar, A.; Piri, R.; Balouchi, H.; Ma, Y. Microbial seed coating: An attractive tool for sustainable agriculture. Biotechnol. Rep. 2023, 37, e00781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, J.E.; Bledsoe, R.B.; Guha, S.; Omari, H.; Crandall, S.G.; Burghardt, L.T.; Couradeau, E. The activity of soil microbial taxa in the rhizosphere predicts the success of root colonization. mSystems 2025, 10, e00458-25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhl, J.; van der Heijden, L.; Butterbach, P.; Gaildry, T.; Haas, L.G.-d.; Houwers, I.; de Lange, E.; Lopez, G.; van Nieuwenhoven, A.; Touceda, M. Survival of seed-coated microbial biocontrol agents during seed storage. Biol. Control 2025, 207, 105809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varma, K.N.; Govindasamy, V.; Vijaysri, D.; Kavya, T.; Bhargava, K.; Sai Akhil, V. Chapter 21—Seed biopriming: Harnessing microbial inoculants for enhanced crop yield. In Enzyme Biotechnology for Environmental Sustainability; Dahiya, P., Singh, J., Kumar, A., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2024; pp. 531–545. [Google Scholar]

- Rojas-Padilla, J.; Díaz-Rodríguez, A.M.; Villalobos, S.d.l.S. Chapter 11—Bioformulation of bacterial inoculants. In New Insights, Trends, and Challenges in the Development and Applications of Microbial Inoculants in Agriculture; Villalobos, S.d.l.S., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2024; pp. 105–116. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, Z.; Yu, P.; Shen, J.; Lambers, H. Do rhizosphere microbiomes match root functional traits? Trends Ecol. Evol. 2025, 40, 885–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouwmeester, H.; Dong, L.; Wippel, K.; Hofland, T.; Smilde, A. The chemical interaction between plants and the rhizosphere microbiome. Trends Plant Sci. 2025, 30, 1002–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, W.; Coffman, L.; Ray, R.; Woldesenbet, S.; Singh, G.; Khan, A.L. Flooding episodes and seed treatment influence the microbiome diversity and function in the soybean root and rhizosphere. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 982, 179554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandhu, S.S.; Alom, J.; Ansari, B.H.; Singh, D. The secret dialogue between plant roots and the soil microbiome: A hidden force shaping plant growth and development. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2025, 140, 102908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoose, B.W.; Call, R.S.; Bates, T.H.; Anderson, R.M.; Roundy, B.A.; Madsen, M.D. Seed conglomeration: A disruptive innovation to address restoration challenges associated with small-seeded species. Restor. Ecol. 2019, 27, 959–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Wu, S. Chitosan–Perilla frutescens essential oil composite coating improves microbial safety and vigor of peanut seeds during long-term storage. J. Stored Prod. Res. 2026, 115, 102843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrika, K.S.V.P.; Singh, A.; Prasad, R.D.; Yadav, P.; Dhara, M.; Kavya, M.; Kumar, A.; Gopalan, B. Porous crosslinked CMC-PVA biopolymer films: Synthesis, standardization, and application in seed coating for improved germination. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl. 2025, 11, 100900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riseh, R.S.; Vazvani, M.G.; Vatankhah, M.; Kennedy, J.F. Chitosan coating of seeds improves the germination and growth performance of plants: A Rreview. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 278, 134750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khatun, M.; Prasanna, R.; Bhardwaj, A.; Makur, S.; Lal, S.K.; Basu, S.; Kumar, P.R. Developing microbial seed coating for enhancing seed vigour and prolonging storability in chickpea. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2024, 172, 289–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, C.A.; Wu, R.; Selles, F.; Harker, K.N.; Clayton, G.W.; Bittman, S.; Zebarth, B.J.; Lupwayi, N.Z. Crop yield and nitrogen concentration with controlled release urea and split applications of nitrogen as compared to non-coated urea applied at seeding. Field Crops Res. 2012, 127, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildirim, K.C.; Orel, D.C.; Okyay, H.; GÜRsan, M.M.; Yildiz, G. Enhancing seed quality and plant growth through modification of seed microbiome with beneficial endophytic bacteria. Sci. Hortic. 2025, 354, 114531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maitra, S.; Sairam, M.; Ray, S.; Praharaj, S.; Gouda, H.S.; Gitari, H.I.; Santosh, D.T.; Atapattu, A.J.; Gaikwad, D.J.; Pramanick, B.; et al. Chapter 7—Seed priming with endophytic microbiome enhances crop yield. In Microbial Inoculants; Kumar, A., Singh, J., Queijeiro López, A.M., Kharwar, R.N., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2025; pp. 111–130. [Google Scholar]

- Bridges, D.F.; Hendricks, A.R.; Colella, N.J.; Compel, W.S.; Melotto, M. Treatment of Alfalfa Seeds with Food-grade Organic Acid Mixtures Reduces Loads of Pathogenic Escherichia coli O157:H7 and Salmonella typhimurium on Sprouts Without Reducing Germination Percentage or Sprout Mass. J. Food Prot. 2025, 88, 100513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etesami, H. The dual nature of plant growth-promoting bacteria: Benefits, risks, and pathways to sustainable deployment. Curr. Res. Microb. Sci. 2025, 9, 100421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Angelis, M.; Napoletano, P.; Cofelice, M.; Di Iorio, E.; Colombo, C.; Baglioni, M.; Rossi, C.; Sorrentino, E.; Alvino, A.; Lopez, F.; et al. Agronomic evaluation of hydrogels containing antimicrobial agents applied on Lactuca sativa L. seeds and plantlets. J. Agric. Food Res. 2025, 24, 102496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giroto, A.S.; Valle, S.F.; Guimarães, G.G.F.; Ohrem, B.; Bresolin, J.; Lücke, A.; Wissel, H.; Hungria, M.; Ribeiro, C.; Mattoso, L.H.C.; et al. Polyglycerol citrate: A novel coating and inoculation material for soybean seeds. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2024, 34, 103627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodi, L.A.; Borges, R.; Bortoletto-Santos, R.; Oliveira-Paiva, C.A.d.; Ribeiro, C.; Farinas, C.S. Biodegradable PVA-based films for delivery of Bacillus megaterium as seed coating. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 114539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdukerim, R.; Li, L.; Li, J.-H.; Xiang, S.; Shi, Y.-X.; Xie, X.-W.; Chai, A.L.; Fan, T.-F.; Li, B.-J. Coating seeds with biocontrol bacteria-loaded sodium alginate/pectin hydrogel enhances the survival of bacteria and control efficacy against soil-borne vegetable diseases. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 279, 135317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menéndez-Cañamares, S.; Blázquez, A.; Albertos, I.; Poveda, J.; Díez-Méndez, A. Probiotic Bacillus subtilis SB8 and edible coatings for sustainable fungal disease management in strawberry. Biol. Control 2024, 196, 105572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, J.M.; Lim, Y.Y.; Ting, A.S.Y. Biopriming Pseudomonas fluorescens to vegetable seeds with biopolymers to promote coating efficacy, seed germination and disease suppression. J. Saudi Soc. Agric. Sci. 2022, 21, 493–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kangsopa, J.; Hynes, R.K.; Siri, B. Lettuce seed pelleting with Pseudomonas sp. 31-12: Plant growth promotion under laboratory and greenhouse conditions. Can. J. Microbiol. 2024, 70, 529–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perveen, S.; Pablos, C.; Reynolds, K.; Stanley, S.; Marugán, J. Growth and prevalence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria in microplastic biofilm from wastewater treatment plant effluents. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 856, 159024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nag, M.; Lahiri, D.; Mukherjee, I.; Ghosh, S.; Dutta, B.; Dey, A.; Ray, R.R. Chapter 11—Efficacy of green synthesized silver nanoparticles (AgNP) over crude plant extract of Allium cepa and standard antibiotic against bacterial biofilms. In Contemporary Medical Biotechnology Research for Human Health; Joshi, S., Mukherjee, S., Nag, M., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022; pp. 103–114. [Google Scholar]

- Kranjec, C.; Mathew, J.P.; Ovchinnikov, K.; Fadayomi, I.; Yang, Y.; Kjos, M.; Li, W.-W. A bacteriocin-based coating strategy to prevent vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium biofilm formation on materials of interest for indwelling medical devices. Biofilm 2024, 8, 100211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Zeng, N.; Pang, J.; Li, C.; Zhang, D.; Ge, J.; Zhao, D.; Li, J.; Ran, R.; Gao, X.; et al. Synergistic interaction in mixed pant growth promoting rhizobacteria consortium enhances biofilm formation and rhizosphere colonization to promote tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) growth. Sci. Hortic. 2025, 351, 114383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, D.K.; Johri, B.N. Interactions of Bacillus spp. and plants—With special reference to induced systemic resistance (ISR). Microbiol. Res. 2009, 164, 493–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar Behera, R.; Muralimohan, K. Seed treatment with diamides provides protection against early and mid-stage larvae of the fall armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae), in maize. J. Asia-Pac. Entomol. 2024, 27, 102187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liaqat, M.; Riaz, S.; Yahya, I.; Pervez, M. Synthesis and application of biodegradable seed coatings to assess the infestation of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) seeds by pests. J. Saudi Soc. Agric. Sci. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, T.-F.; Luan, Y.-Y.; Xiang, S.; Shi, Y.-X.; Xie, X.-W.; Chai, A.L.; Li, L.; Li, B.-J. Seed coating with biocontrol bacteria encapsulated in sporopollenin exine capsules for the control of soil-borne plant diseases. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 281, 136093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morcuende, J.; Martín-García, J.; Velasco, P.; Sánchez-Gómez, T.; Santamaría, Ó.; Rodríguez, V.M.; Poveda, J. Effective biological control of chickpea rabies (Ascochyta rabiei) through systemic phytochemical defenses activation by Trichoderma roots colonization: From strain characterization to seed coating. Biol. Control 2024, 193, 105530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo-Agudo, M.; Dregni, J.; González-Cabrera, J.; Dicke, M.; Heimpel, G.E.; Tena, A. Neonicotinoids from coated seeds toxic for honeydew-feeding biological control agents. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 289, 117813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hladik, M.L.; Bradbury, S.; Schulte, L.A.; Helmers, M.; Witte, C.; Kolpin, D.W.; Garrett, J.D.; Harris, M. Neonicotinoid insecticide removal by prairie strips in row-cropped watersheds with historical seed coating use. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2017, 241, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgado, L.D.; Groves, R.L.; Owens, D.; Waters, T.D.; Burkness, E.C.; Hutchison, W.D.; Yang, F.; Nault, B.A. Performance of novel alternatives to neonicotinoid insecticide seed treatments for managing maggots (Diptera: Anthomyiidae) in large-seeded vegetable crops. Crop Prot. 2025, 197, 107355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Yan, F.; Shi, C.; Zhang, H.; Tiến, L.H.; Tín, H.T.; Yang, N.; Fu, R.; Yu, Z.; Zhou, Y.; et al. Enhancing beneficial microbe viability and tobacco black shank disease control via sodium alginate–polyethylene glycol–glycerol hydrogel seed coating. Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 238, 122308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, P.; Sharma, N.; Agrawal, R. Chapter 21—Seed treatment with biopolymers for alleviation of abiotic stresses in plants. In Nanotechnology for Abiotic Stress Tolerance and Management in Crop Plants; Pudake, R.N., Tripathi, R.M., Gill, S.S., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2024; pp. 327–334. [Google Scholar]

- Hosseini-Moghaddam, M.; Moradi, A.; Piri, R.; Glick, B.R.; Fazeli-Nasab, B.; Sayyed, R.Z. Seed coating with minerals and plant growth-promoting bacteria enhances drought tolerance in fennel (Foeniculum vulgare L.). Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2024, 58, 103202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martí-Guillén, J.M.; Martínez-Lorente, S.E.; Pedreño, M.Á.; Almagro, L.; Sabater-Jara, A.B. Grapevine cell culture-based biostimulant alleviates salt stress in tomato seeds. J. Agric. Food Res. 2025, 22, 102145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, A.; Malla, M.A.; Kumar, A.; Khan, M.L.; Kumari, S. Seed bio-priming with ACC deaminase-producing bacterial strains alleviates impact of drought stress in Soybean (Glycine max (L.) Merr.). Rhizosphere 2024, 30, 100873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Pan, S.; Guo, G.; Gu, Q.; Pan, R.; Guan, Y.; Hu, J. Preparation of a thermoresponsive maize seed coating agent using polymer hydrogel for chilling resistance and anti-counterfeiting. Prog. Org. Coat. 2020, 139, 105452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafi, Z.; Shahid, M. Root exudates as molecular architects shaping the rhizobacterial community: A review. Rhizosphere 2025, 36, 101212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Niu, S.; Wei, Y.; Liu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, P.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, J.J. The role of extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) in chemical-degradation of persistent organic pollutants in soil: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 912, 168877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, Y.; Tan, H.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, J. Unraveling the role of dark septate endophytes and extracellular polymeric substances in soil aggregate formation and alfalfa growth enhancement. Rhizosphere 2025, 34, 101093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, W.; Ge, Z.; Zheng, T.; Wu, N.; Wang, M.; Zhi, L.; Ma, J.; Wei, W.; Feng, Y.; Liu, Y.; et al. Isolation, Identification, and Potential Biotechnological Application on Soil Porosity of the Microbial Exopolysaccharides (EPS) from Bacillus polymyxa. Biomacromolecules 2025, 26, 3771–3785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, M.; Zhang, M.; Cai, P.; Wu, Y.; Fu, Q.; Zhang, X.; Miao, F.; Xing, W.; Chen, S.; Xiao, K.-Q.; et al. Increased microbial extracellular polymeric substances as a key factor in deep soil organic carbon accumulation. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2026, 212, 109998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmile-Gordon, M.; Gregory, A.S.; White, R.P.; Watts, C.W. Soil organic carbon, extracellular polymeric substances (EPS), and soil structural stability as affected by previous and current land-use. Geoderma 2020, 363, 114143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishad, H.; Kashyap, S.; Khan, A.; Kumar, R.; Mohapatra, R.K.; Nayak, M. Microalgal EPS as a bio-flocculant for sustainable biomass harvesting: A review. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 378, 134844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Zhang, H.; Lv, Z.; Zhang, J.; Li, G. Microbial inoculation improves soil aggregation by enhancing exopolysaccharides and lipopolysaccharides-related gene abundance in saline soil. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2025, 214, 106388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zouitane, I.; Ferioun, M.; Tirry, N.; Derraz, K.; Louahlia, S.; El Ghachtouli, N. Chapter 18—EPS producing plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria for stress tolerance. In Phytomicrobiome and Stress Regulation; Ilyas, N., Sayyed, R., Khan, A., Mix, K.D., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2025; pp. 371–397. [Google Scholar]

- Procházka, P.; Štranc, P.; Vostřel, J.; Řehoř, J.; Brinar, J.; Křováček, J.; Pazderů, K. The influence of effective soybean seed treatment on root biomass formation and seed production. Plant Soil Environ. 2019, 65, 588–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q.; Gu, Y.; Du, L.; Zhou, M.; Yang, D. Effects of lignin/polyethylene glycol as film-forming agents in 5 wt% of chlorantraniliprole flowable concentrate for seed coating on coating performance, germination and growth of different seeds. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 217, 118834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irshad, M.K.; Ansari, J.R.; Noman, A.; Javed, W.; Lee, J.C.; Aqeel, M.; Waseem, M.; Lee, S.S. Seed priming with Fe3O4-SiO2 nanocomposites simultaneously mitigate Cd and Cr stress in spinach (Spinacia oleracea L.): A way forward for sustainable environmental management. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 286, 117195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Feng, H.; Yang, C.; Ma, X.; Li, P.; Feng, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, L.; Zhou, J.; Xu, X.; et al. Integrated microbiology and metabolomics analysis reveal responses of cotton rhizosphere microbiome and metabolite spectrum to conventional seed coating agents. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 333, 122058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Huang, J.; Li, Y.; Wan, L.; Ma, X.; Song, J.; Liu, Z. Numerical simulation method of seed pelletizing: Increasing seed size by powder adhesion. Powder Technol. 2024, 444, 119991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardak, M.H.; Nkede, F.N.; Van, T.T.; Meng, F.; Xirui, Y.; Jothi, J.S.; Tanaka, F.; Tanaka, F. Development of a coating material composed of sodium alginate and kiwifruit seed essential oil to enhance persimmon fruit quality using a novel partial coating technique. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2024, 45, 101331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrini, S.; Lullfitz, D.; Fontaine, A.; Just, M.; Turner, S. Effectiveness and economic viability of native seed pelleting in large-scale seedling production for revegetation. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 993, 180008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrini, S.; Webber, Z.; D’Agui, H.; Dixon, K.; Just, M.; Arya, T.; Turner, S. Customise the seeds, not the seeder: Pelleting of small-seeded species for ecological restoration. Ecol. Eng. 2023, 196, 107105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotfi, N.; Soleimani, A.; Vahdati, K.; Wei, W.; Mohammadi, P. Bio-priming walnut seeds with novel PGPR strains enhances germination and drought resilience under osmotic stress. Sci. Hortic. 2025, 344, 114073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, K.W.; Clenet, D.R.; Madsen, M.D.; Brown, V.S.; Ritchie, A.L.; Svejcar, L.N. Activated carbon seed technologies: Innovative solutions to assist in the restoration and revegetation of invaded drylands. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 371, 123281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Liu, X.; Gu, A.; Chang, X.; Shi, X.; Li, X.; Hao, J.; Liu, P. Nano-formulated prothioconazole seed coating improves rice bakanae control and seedling establishment via metabolome and respiration modulation. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 524, 169529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, D.; Wang, H. Preparation of a Novel Highly Effective and Environmental Friendly Wheat Seed Coating Agent. Agric. Sci. China 2010, 9, 937–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yonsel, Ş.; Demir, M. Coating of wheat seeds with the PGP fungus Trichoderma harzianum KUEN 1581. New Biotechnol. 2012, 29, S23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lira, A.C.d.; Mascarin, G.M.; Delalibera Júnior, Í. Microsclerotia production of Metarhizium spp. for dual role as plant biostimulant and control of Spodoptera frugiperda through corn seed coating. Fungal Biol. 2020, 124, 689–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasan Naqvi, S.A.; Rehman, A.U.; Din Umar, U.U. Synergistic interplay of microbial probiotics in rice rhizosphere: A sustainable strategy for bacterial blight management through microbiome engineering. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2025, 136, 102568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, N.D.; Vaughan, M.M.; McCormick, S.P.; Brown, J.A.; Bakker, M.G. Sarocladium zeae is a systemic endophyte of wheat and an effective biocontrol agent against Fusarium head blight. Biol. Control 2020, 149, 104329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayat, H.S.; Rehman, A.-u.; Farooq, S.; Naveed, M.; Ali, H.M.; Hussain, M. Boron seed coating combined with seed inoculation with boron tolerant bacteria (Bacillus sp. MN-54) and maize stalk biochar improved growth and productivity of maize (Zea mays L.) on saline soil. Heliyon 2023, 9, e22075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandit, N.R.; Mulder, J.; Hale, S.E.; Martinsen, V.; Schmidt, H.P.; Cornelissen, G. Biochar improves maize growth by alleviation of nutrient stress in a moderately acidic low-input Nepalese soil. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 625, 1380–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Q.; Huang, T.; Zhou, C.; Wan, X.; He, X.; Miao, P.; Cheng, H.; Wang, X.; Yu, H.; Hu, M.; et al. Nano-priming with selenium nanoparticles reprograms seed germination, antioxidant defense, and phenylpropanoid metabolism to enhance Fusarium graminearum resistance in maize seedlings. J. Adv. Res. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alegbeleye, O.; Boas, D.M.V.; Sant’Ana, A.S. Harnessing the microbiota of vegetables and ready-to-eat (RTE) vegetables for quality and safety. Food Res. Int. 2025, 214, 116667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, A.; Ghate, V.; Zhou, W. Direct seeding compromised the vitamin C content of baby vegetables and the glucosinolate content of mature vegetables in Asian leafy brassicas. Food Chem. 2024, 437, 137783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, K.; Qin, Y. Seed-borne bacterial infections: From infection mechanisms to sustainable control strategies. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2025, 139, 102858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolomiiets, Y.; Butsenko, L.; Yemets, A.; Blume, Y. The Use of PGPB-based Bioformulations to Control Bacterial Diseases of Vegetable Crops in Ukraine. Open Agric. J. 2024, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaidi, A.; Ahmad, E.; Khan, M.S.; Saif, S.; Rizvi, A. Role of plant growth promoting rhizobacteria in sustainable production of vegetables: Current perspective. Sci. Hortic. 2015, 193, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Li, H.; Ma, Q.; Dong, Q.; Gao, J.; Zhang, F.; Xie, H. Mitigating continuous cropping challenges in alkaline soils: The role of biochar in enhancing soil health, microbial dynamics, and pepper productivity. Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 234, 121576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Li, H.; Ma, Q.; Mu, S.; Zhao, Z.; Gao, J.; Zhang, F.; Xie, H. Exploring the mitigation effect of microbial inoculants on the continuous cropping obstacle of capsicum. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 338, 113507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.-W.; Zhu, Y.-X.; Xu, M.; Cai, X.-Y.; Tian, F. Co-application of spent mushroom substrate and PGPR alleviates tomato continuous cropping obstacle by regulating soil microbial properties. Rhizosphere 2022, 23, 100563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Xu, M.; Yan, X.-L.; Xing, R.; Kang, Y.-J.; Wang, H.-W. Co-inoculation of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens and Pleurotus ostreatus alleviates replanting obstacles in continuously cropped soil by enhancing the soil nutrient cycle and beneficial microorganisms. Rhizosphere 2025, 36, 101175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez-Estrella, F.; Jurado, M.M.; López-González, J.A.; Toribio, A.; Martínez-Gallardo, M.R.; Estrella-González, M.J.; López, M.J. Seed priming by application of Microbacterium spp. strains for control of Botrytis cinerea and growth promotion of lettuce plants. Sci. Hortic. 2023, 313, 111901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nivedha, R.M.; Prasanna, R.; Khatun, M.; Varsha, D.; Bhardwaj, A.; Lal, S.K.; Basu, S.; Rej, S.; Singh, A.K.; Shivay, Y.S. Beneficial cyanobacteria as seed coatings to enhance the storability and viability indices of spinach seeds. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2025, 70, 103844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Shao, D.; Wang, C.; Wang, J.; Wang, B.; Zhao, J.; Xu, Z.; et al. Biochar-based pelletized seed enhances the yield of late-sown rapeseed by improving the relative growth rate and cold resistance of seedlings. Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 223, 119993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, H.; Yaghoubi Hamgini, E.; Jafari, S.M.; Bolourian, S. Improving the oxidative stability of sunflower seed kernels by edible biopolymeric coatings loaded with rosemary extract. J. Stored Prod. Res. 2020, 89, 101729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, A.; Hassan, A.; Akram, W.; Anjum, T.; Aftab, Z.-e.-H.; Ali, B. Seed coating with the synthetic consortium of beneficial Bacillus microbes improves seedling growth and manages Fusarium wilt disease. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 325, 112645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasbaji, M.; Atmani, F.E.; Kasbaji, M.A.; Grimi, N.; M’Barki, M.; El Achaby, M.; Moubarik, A.; Oubenali, M. Chapter 3—Biocompatibility, biodegradability, toxicity, life cycle analysis, social economic aspects, environmental, and health impact of biopolymers. In Functionalized Biopolymers; Sharma, S., Nadda, A.K., Deshmukh, K., Hussain, C.M., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2026; pp. 89–121. [Google Scholar]

- Moulahoum, H.; Ghorbanizamani, F. Chapter 15—Functionalized biopolymer-based coatings and adhesives. In Functionalized Biopolymers; Sharma, S., Nadda, A.K., Deshmukh, K., Hussain, C.M., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2026; pp. 557–601. [Google Scholar]

- Pinaeva, L.G.; Noskov, A.S. Biodegradable biopolymers: Real impact to environment pollution. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 947, 174445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Peng, J. Recognizing ecosystem service’s contribution to SDGs: Ecological foundation of sustainable development. Geogr. Sustain. 2024, 5, 511–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garduño-Jiménez, A.-L.; Gomes, R.L.; López-Maldonado, Y.; Carter, L.J. Addressing the global data imbalance of contaminants of emerging concern in the context of the United Nations sustainable development goals. RSC Sustain. 2025, 3, 3384–3391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarrete, S.D.S.; Borini, F.M.; Avrichir, I. Environmental upgrading and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 264, 121563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Y.; Li, S.; Wang, Y.; Yao, Z.; Yu, Z.; Zhang, W.; Yang, J. Seed Coatings as Biofilm Micro-Habitats: Principles, Applications, and Sustainability Impacts. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2854. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122854

Wang Y, Li S, Wang Y, Yao Z, Yu Z, Zhang W, Yang J. Seed Coatings as Biofilm Micro-Habitats: Principles, Applications, and Sustainability Impacts. Agronomy. 2025; 15(12):2854. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122854

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Yujie, Shunjin Li, Yuan Wang, Zhi Yao, Zhi Yu, Wei Zhang, and Jingzhi Yang. 2025. "Seed Coatings as Biofilm Micro-Habitats: Principles, Applications, and Sustainability Impacts" Agronomy 15, no. 12: 2854. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122854

APA StyleWang, Y., Li, S., Wang, Y., Yao, Z., Yu, Z., Zhang, W., & Yang, J. (2025). Seed Coatings as Biofilm Micro-Habitats: Principles, Applications, and Sustainability Impacts. Agronomy, 15(12), 2854. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122854