1. Introduction

Potatoes (

Solanum tuberosum L.) are among the most important field crops in the world [

1]. Their production frequently faces serious challenges posed by wireworms (

Agriotes spp.) as one of the most important potato pests. Wireworms cause damage and consequential economic harm by boring into tubers, which reduces the market value of the yield and increases susceptibility to secondary infections [

2,

3]. Although wireworm attack does not affect crop yield directly, it reduces crop quality considerably [

4]. The use of synthetic insecticides for wireworm control is often ineffective [

5] and subject to criticism due to its negative impact on non-target organisms [

6].

To this end, the use of environmentally acceptable methods has become a focal point of wireworm control research. These methods include, for example, the biological control of wireworms, where entomopathogenic bacteria, fungi, nematodes, and predators from the family Staphylinidae can be used [

7]. Biofumigation is also a method for the environmentally acceptable control of soil-borne pests and diseases, which is most often based on mulching and ploughing wild crucifers into the soil, where the breakdown of glucosinolates forms natural compounds with insecticidal, herbicidal, and nematicidal activity in the soil [

6,

8].

Brassica carinata and

Brassica hirta were chosen based on the fact that they contain a lot of glucosinolates and their derivates are important for wireworm suppression [

8]. In our investigation, however, we wanted to determine the potential of biofumigation combined with biological control agents for reducing wireworm abundance [

9].

Among the environmentally acceptable ways of reducing wireworm damage are also attractants, intercrops, and trap crops, crop rotation, tillage, flooding or drainage of the soil, the use of semiochemicals, and tolerant varieties [

7,

10].

Strategies for the environmentally acceptable reduction in wireworms in agricultural land below the economic damage threshold therefore most often do not involve the use of a single control method, but rather several of these methods should be combined and used over a longer period [

3]. It is evident from the literature that the preventive treatment of winter oats as a trap crop with the entomopathogenic fungi

Metarhizium brunneum Petch shows promising results [

11]. The results of research conducted in Switzerland are also promising [

12], where pre-crops (

Avena strigosa,

Trifolium alexandrinum,

Guizotia abyssinica,

Phacelia tanacetifolia) before potatoes were also treated with the fungus

M. brunneum. The inclusion of trap crops in crop rotation can also improve functional biodiversity and nutrient availability in the soil and is also an important factor in plant protection as it suppresses weed growth [

7].

In addition to the previously mentioned methods of wireworm control, we are also aware of the insecticidal effect of various fertilizers, such as calcium cyanamide [

13], or plant extracts that have a repellent effect on wireworms. Thus, we can talk about the encouraging effect of cinnamaldehyde, which can be added to the field during irrigation, and azadirachtin as the active substance in Neem cake, which also acts as a repellent against wireworms [

14].

The main purpose of our research was to precisely study and evaluate the synergistic effect of a large number of environmentally acceptable methods for reducing wireworm abundance in the soil and damage to potato tubers. Since even one hole in a tuber is enough to make potatoes unmarketable [

15], we wanted to determine whether it is possible to produce completely healthy tubers using any of the tested methods. We also hypothesized that we would be able to confirm differences in the yield of tubers among the individual treatments. In addition, we anticipated that the combination of zeolites and entomopathogens would be one of the most effective combinations against wireworms in potato fields. At the same time, we also examined the effect of the substances used in the experiment on tuber yield and on the most important soil parameters.

3. Results

3.1. Soil Excavation

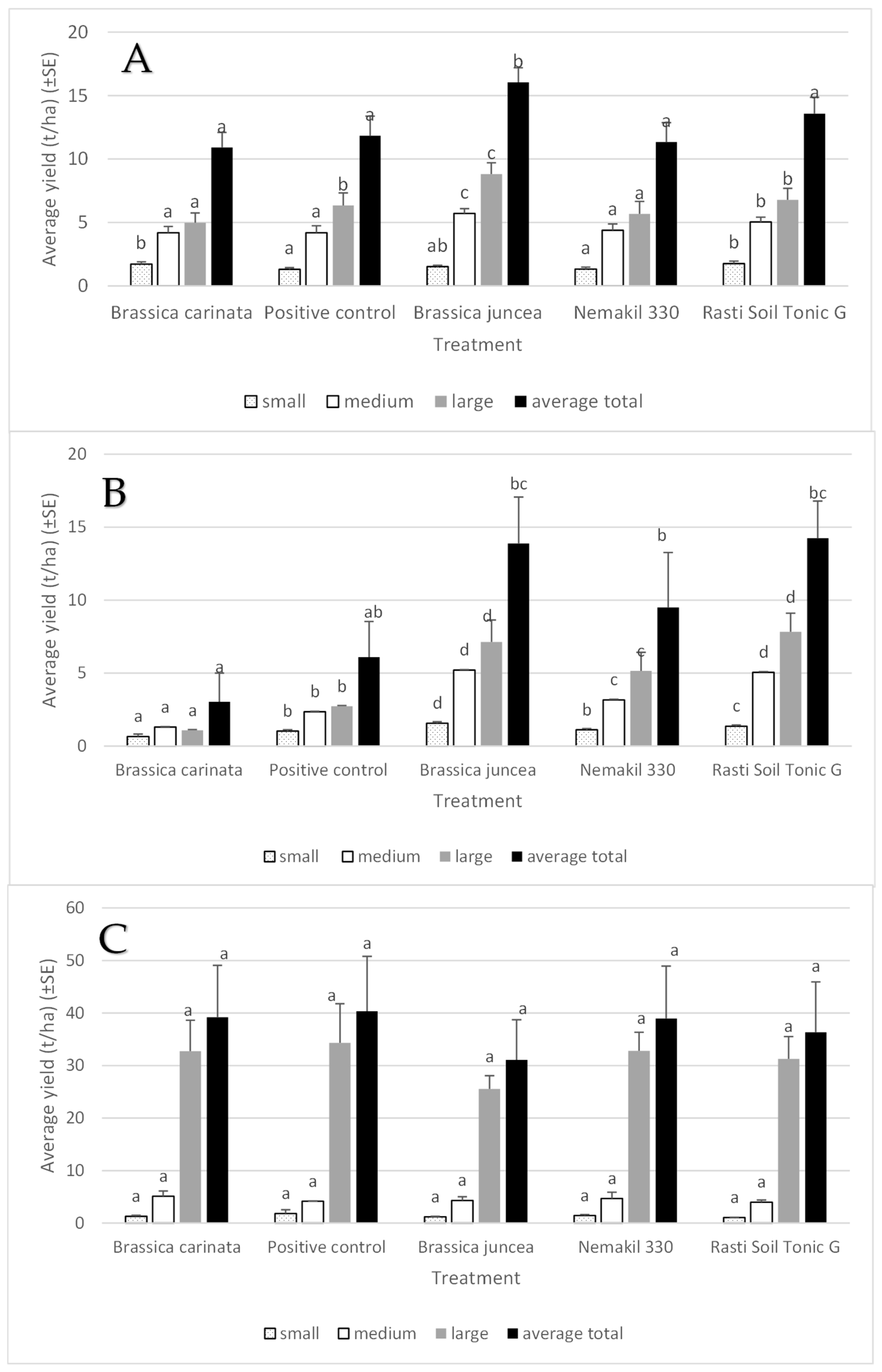

We found that the average number of wireworms in the soil differed significantly between the first-order treatments in the first (F4,18 = 120.40, p < 0.05), second (F4,18 = 117.14, p < 0.05), and third years of the study (F4,18 = 203.20, p < 0.05). The average number of wireworms was significantly affected by the date of excavation in the first (F2,18 = 30.20, p < 0.05), second (F2,18 = 25.17, p < 0.05), and third (F5,27 = 26.10, p < 0.05) years of the study.

In the first year, the lowest average number of wireworms was found in the Nemakil 330 treatment group (0.88 wireworm per 1 m

2), but this number did not differ significantly from the other treatment groups. In the first term of soil excavation (i.e., before the Brassica species were ploughed or other products were applied to the field), the average number of wireworms was the highest in all treatment groups; namely, 6 wireworms per m

2 were found in the positive control group, and 3.33 wireworms per m

2 were confirmed in the

Brassica juncea treatment group. After the application of the products or ploughing of the cruciferous vegetables, strings were found only in the soil of the Rasti Soil Tonic and

Brassica carinata treatment groups (

Figure 1A).

In the second year of research, we also recorded the highest average number of wireworms in the soil before ploughing of the crucifers or applying the products to the soil surface. During the only soil excavation after the application, we detected wireworms only in the

Brassica juncea treatment group, specifically less than 1 wireworm per m

2 (

Figure 1B).

In the third year of the research, on the first soil excavation date, we found 5 wireworms per m

2 in the

Brassica carinata treatment group, 3 wireworms per m

2 in the

Brassica juncea treatment group, and 2 wireworms per m

2 in the Nemakil 330 treatment group. On the first soil excavation date after applying the products to the soil surface or after ploughing in the crucifers, we still found more than 2 wireworms per m

2 in the

Brassica juncea treatment group. On the aforementioned date, no wireworms were found in the soil excavations in the Nemakil 330 and Rasti Soil Tonic treatment groups (

Figure 1C).

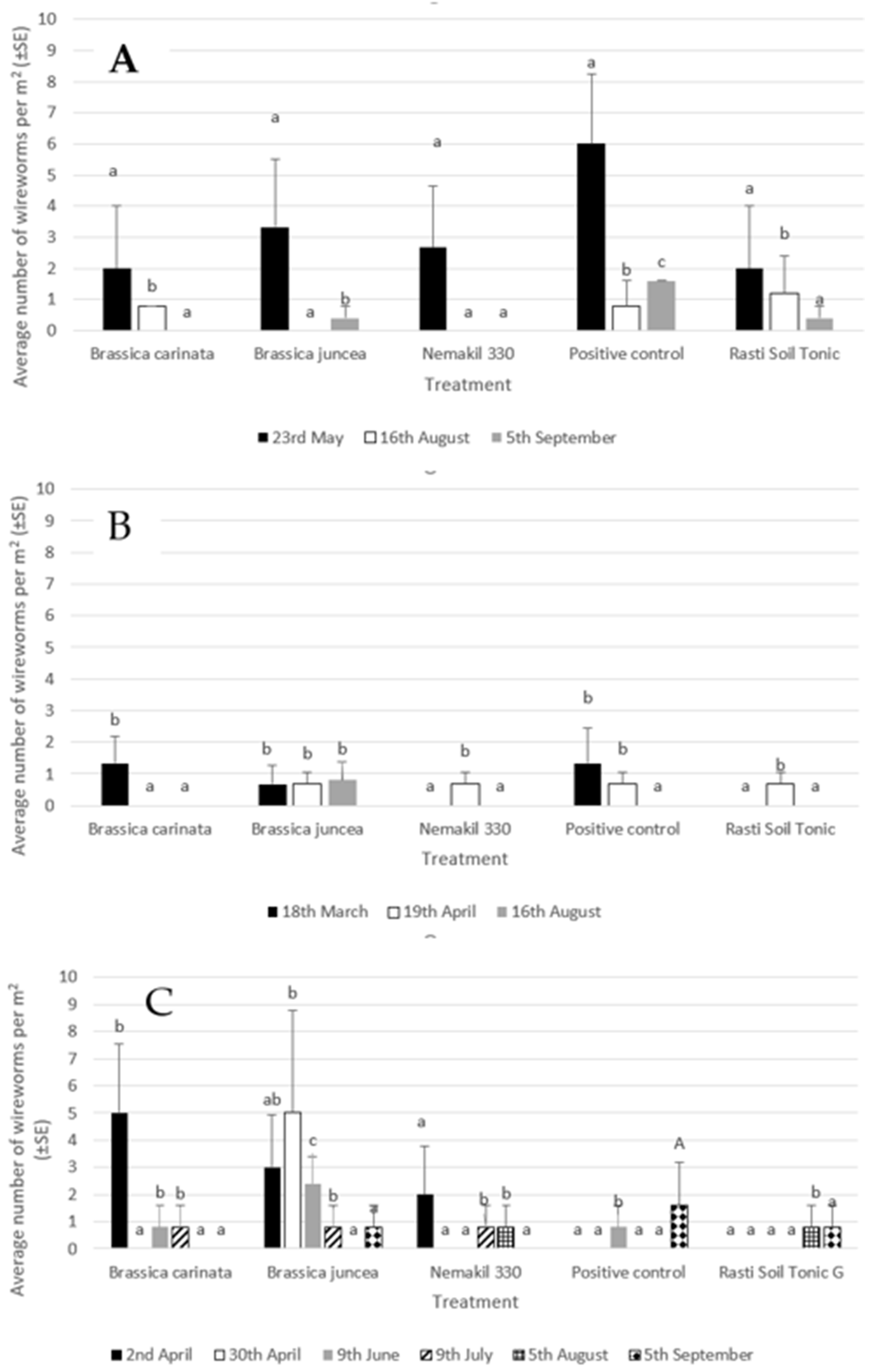

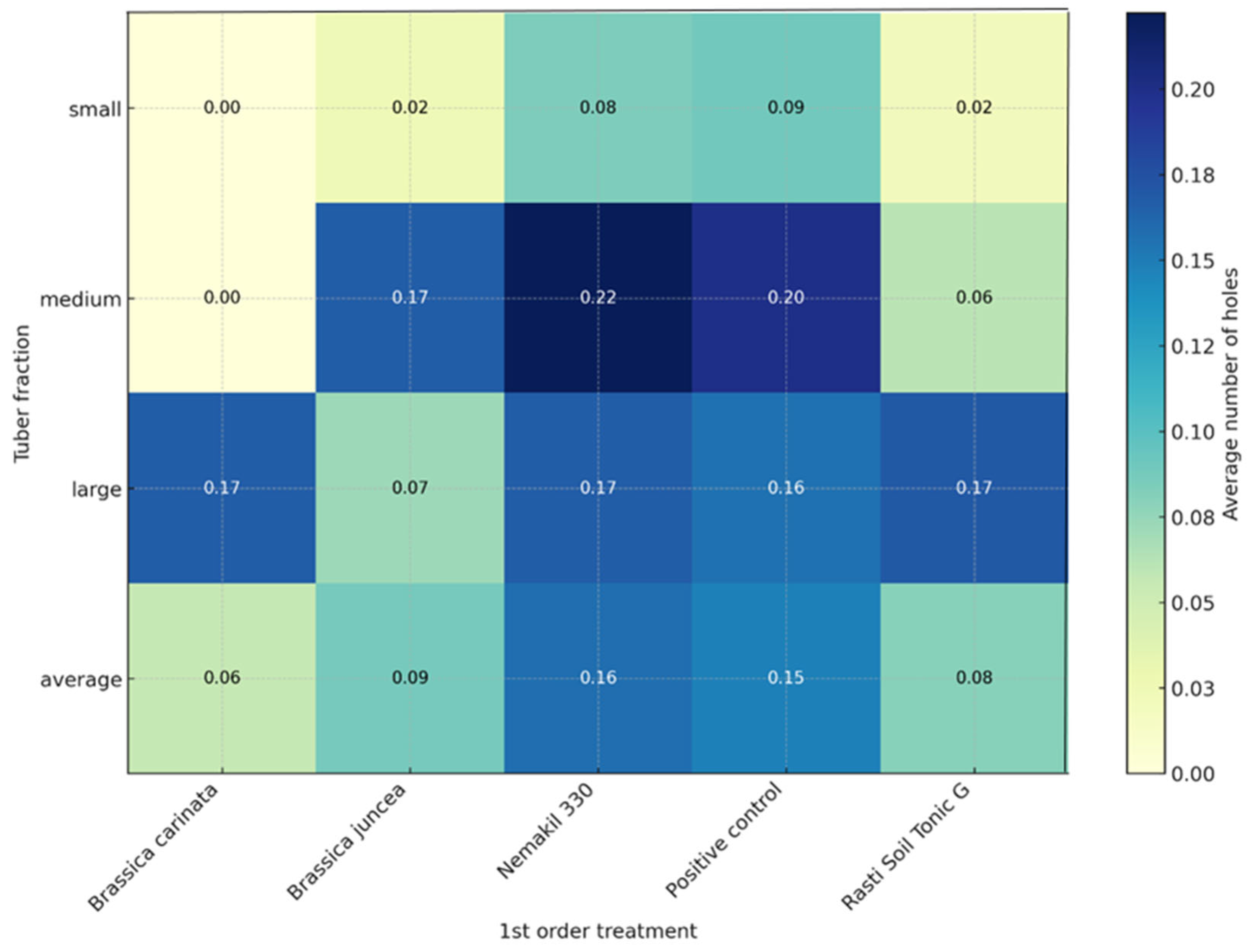

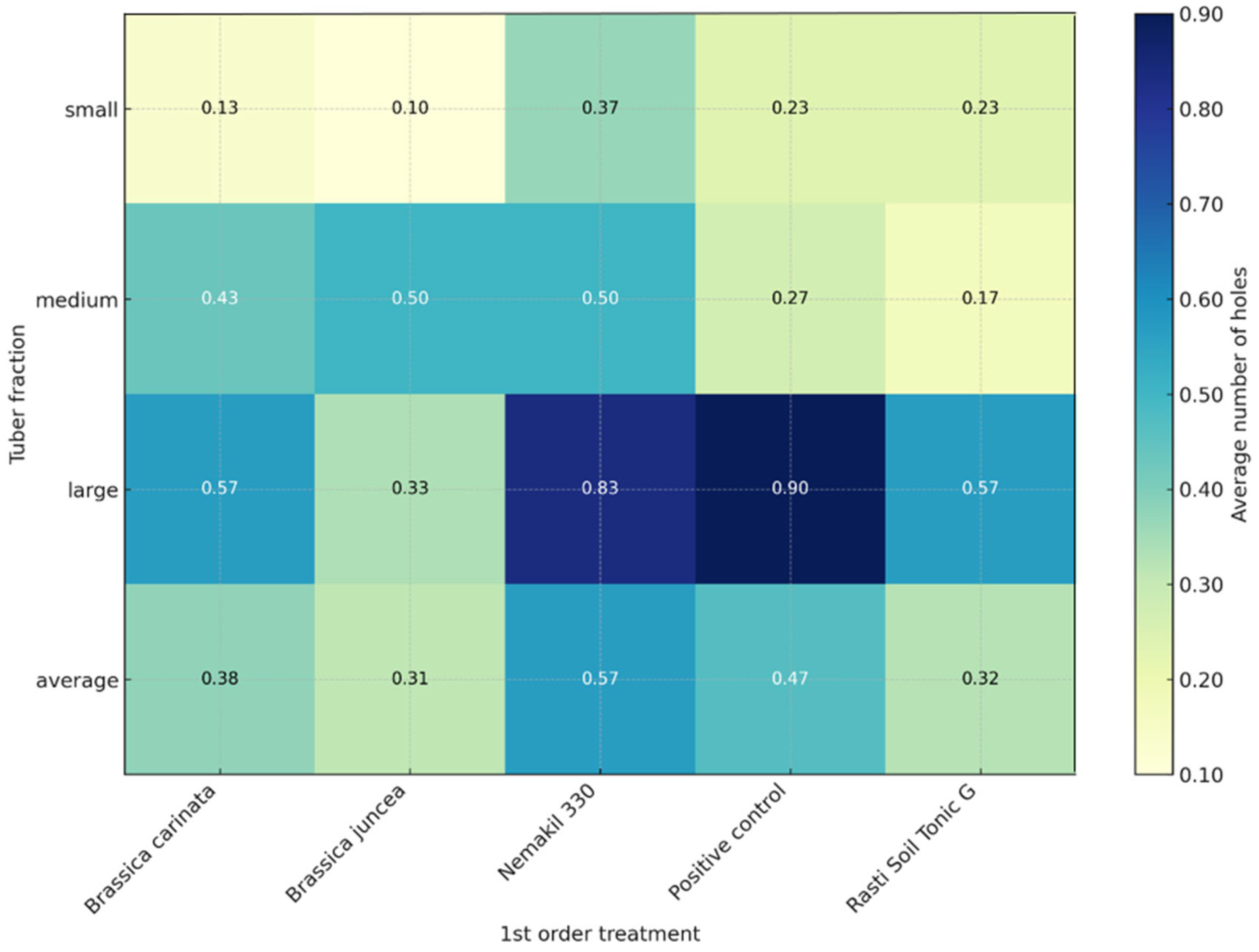

3.2. Damage on Tubers Due to Wireworm Feeding According to First-Order Treatments

We found that the average number of holes on potatoes differed according to the fraction in the first (F2,45 = 12.10, p < 0.05), second (F2,60 = 16.14, p < 0.05), and third (F2,49 = 17.10, p < 0.05) years of the experiment. Similarly, tuber damage depended on the type of treatment in the first (F4,16 = 8.05, p < 0.05), second (F4,16 = 12.10, p < 0.05), and third (F4,16= 8.90, p < 0.05) years.

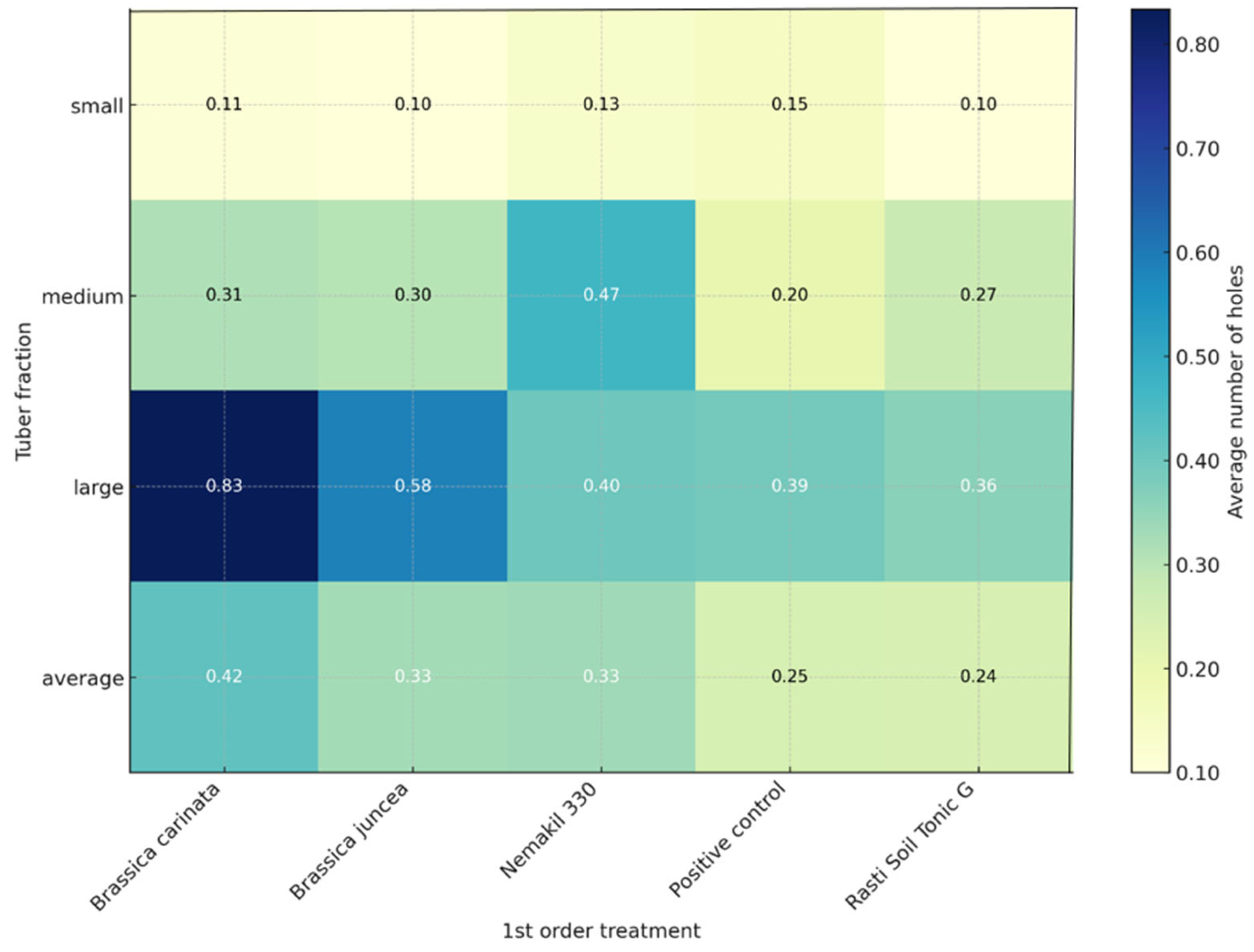

In the first year of the research, we demonstrated the highest number of holes in small-fraction tubers in the positive control group (0.15 ± 0.08 holes per tuber), while in medium-fraction tubers, we noted the highest average number of holes for the Nemakil 330 treatment (0.46 ± 0.24), and the least damage on tubers from this fraction was found in the positive control group (0.20 ± 0.08 holes per tuber). The healthiest tubers of the largest fraction were found in the Rasti Soil Tonic G treatment group (0.36 ± 0.0 holes/tuber). In the second year of the research, no damage was recorded on the small and medium tubers grown using the Brassica carinata treatment, while the lowest number of holes on large tubers was found in the Brassica juncea treatment group (0.07 ± 0.05). The average number of holes due to wireworm feeding was the lowest in the Brassica juncea treatment group for small tubers (0.10 ± 0.05 holes/tuber), medium-fraction tubers were least damaged in the Rasti Soil Tonic G treatment group (0.16 ± 0.07 holes/tuber), and for large-fraction tubers, the least damaged were the tubers from the Brassica juncea treatment group (0.33 ± 0.16 holes per tuber)

In the first year, we recorded the lowest average number of holes on tubers in the positive control (0.25 ± 0.09) and Rasti Soil Tonic treatment (0.25 ± 0.07) groups (

Figure 2). Detailed statistical descriptions for

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 are given in the

Supplementary File.

In the second year, the

Brassica carinata,

Brassica juncea, and Rasti Soil Tonic G treatments stood out in the same regard, with 0.05 ± 0.05, 0.08 ± 0.05, and 0.08 ± 0.04 holes per tuber, respectively (

Figure 3). The average number of holes per tuber in the last year of the research was among the lowest in the

Brassica juncea (0.31 ± 0.17 holes/tuber) and Rasti Soil Tonic G (0.32 ± 0.13 holes/tuber) treatment groups (

Figure 4).

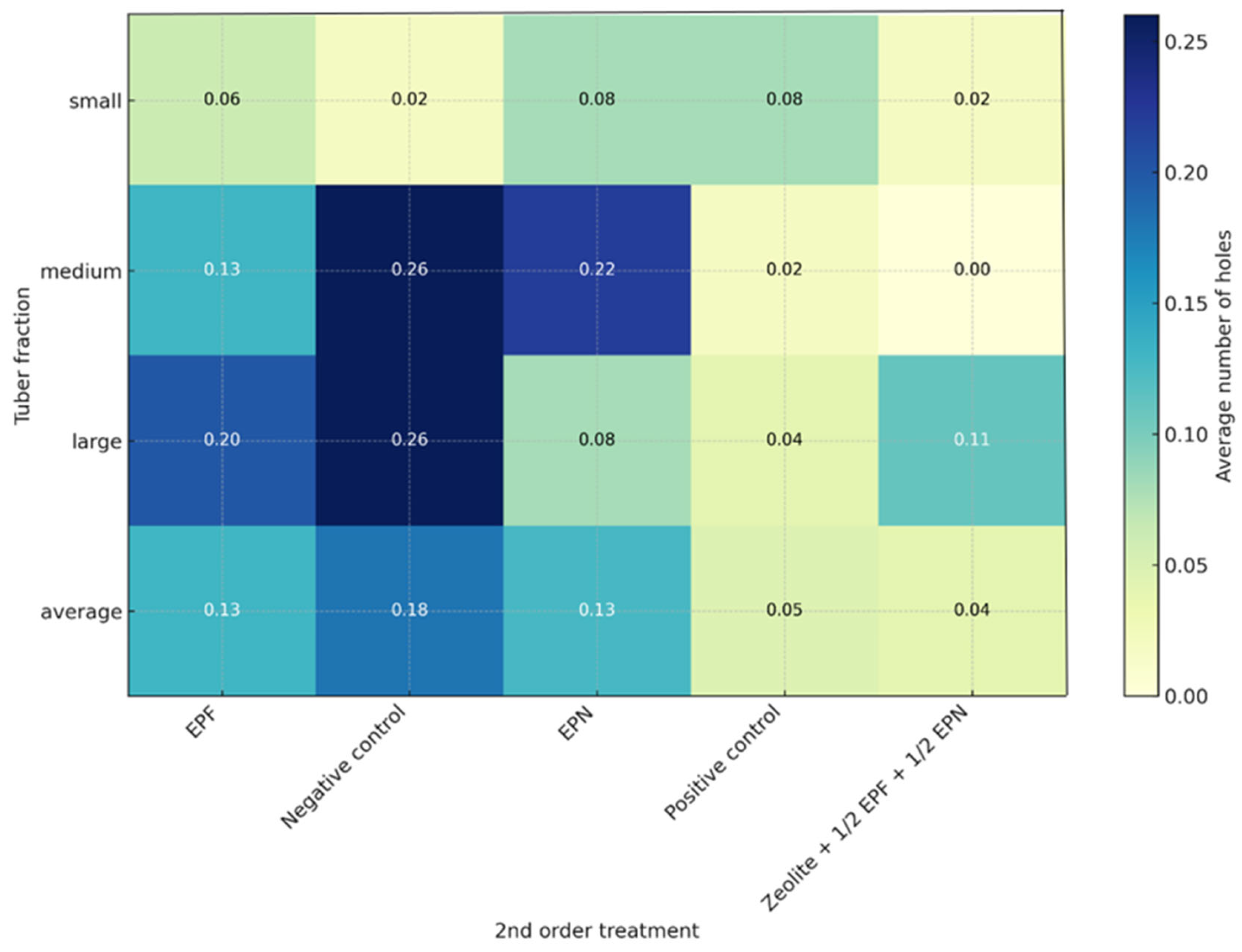

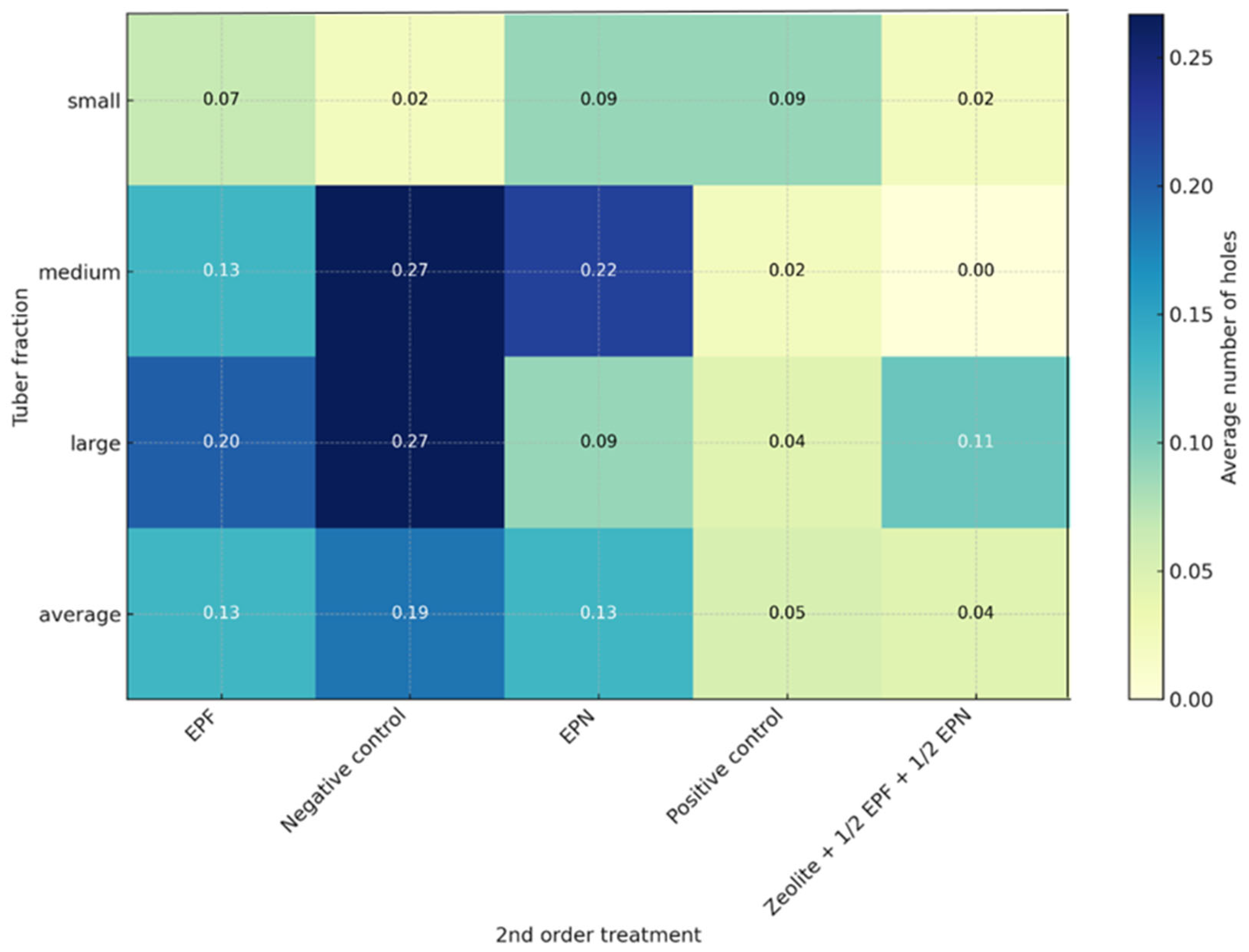

3.3. Damage on Tubers Due to Wireworm Feeding According to Second-Order Treatments

We found that the average number of holes on potato tubers differs according to the potato fraction in the first (F2,45 = 7.14, p < 0.05), second (F2,60 = 11.30, p < 0.05), and third (F2,49 = 19.60, p < 0.05) years of the experiment. Similarly, tuber damage was affected by the treatment in the first (F4,16 = 10.70, p < 0.05) and second (F4,16 = 13.13, p < 0.05) years, while no such differences were detected in the third year (F4,16 = 21.30, p = 0.0927).

In the first year of the research, we found the largest average extent of damage in the EPN treatment group (0.13 ± 0.07 holes per tuber), and 0.22 ± 0.08 holes per tuber were confirmed for the medium fraction of tubers that were sprayed with the EPN product (

Figure 5). In the second year, the largest extent of damage was found on the tubers from the negative control group (0.18 ± 0.08 holes per tuber), with medium- and large-fraction tubers being more severely damaged (

Figure 6). In the third year, we did not find differences in the average number of holes per tuber based on the treatment (

Figure 7). On average, the small-fraction tubers were most damaged in the zeolite + ½ EPF + ½ EPN treatment group. Detailed statistical descriptions for

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 are given in the

Supplementary File.

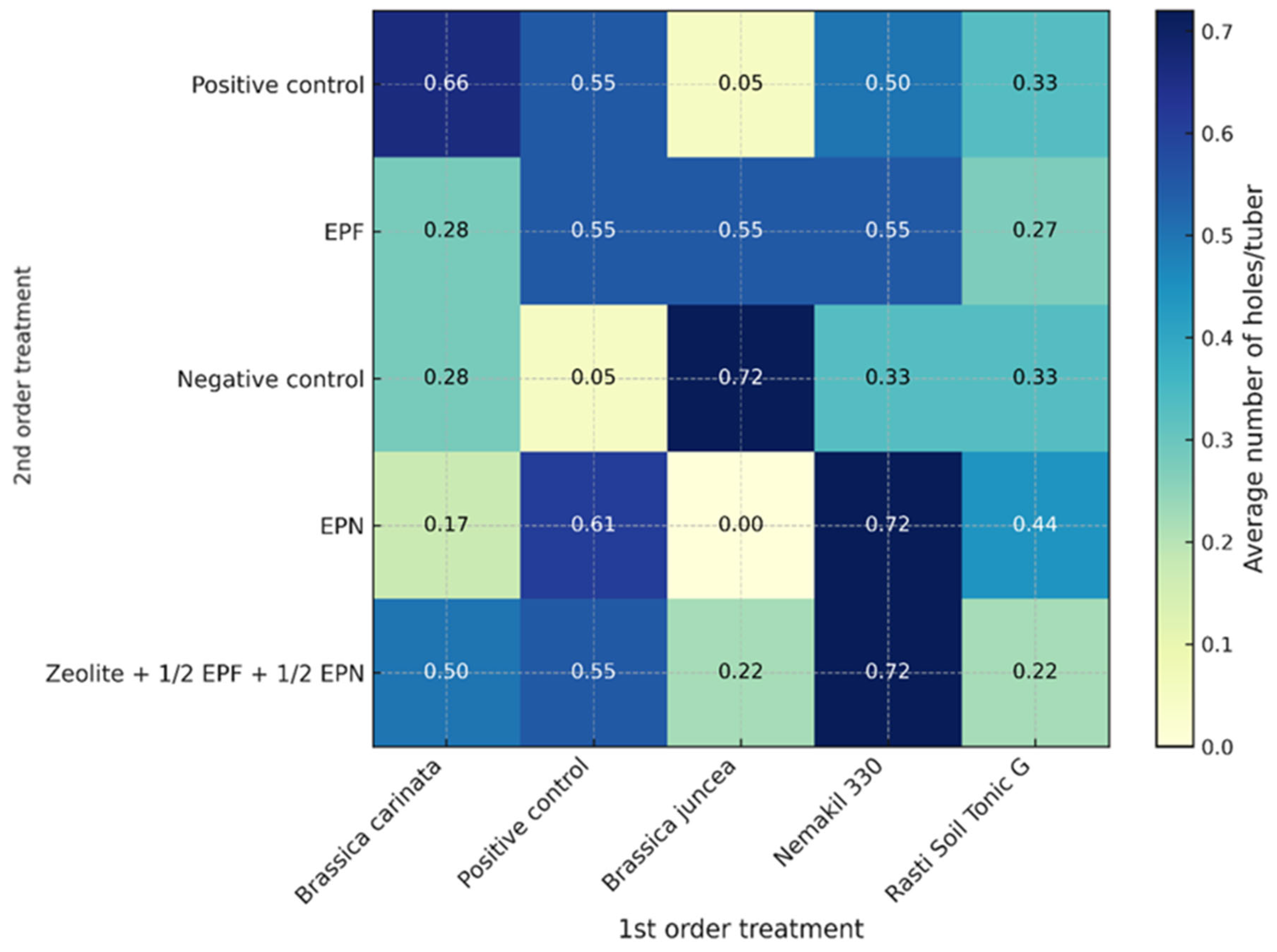

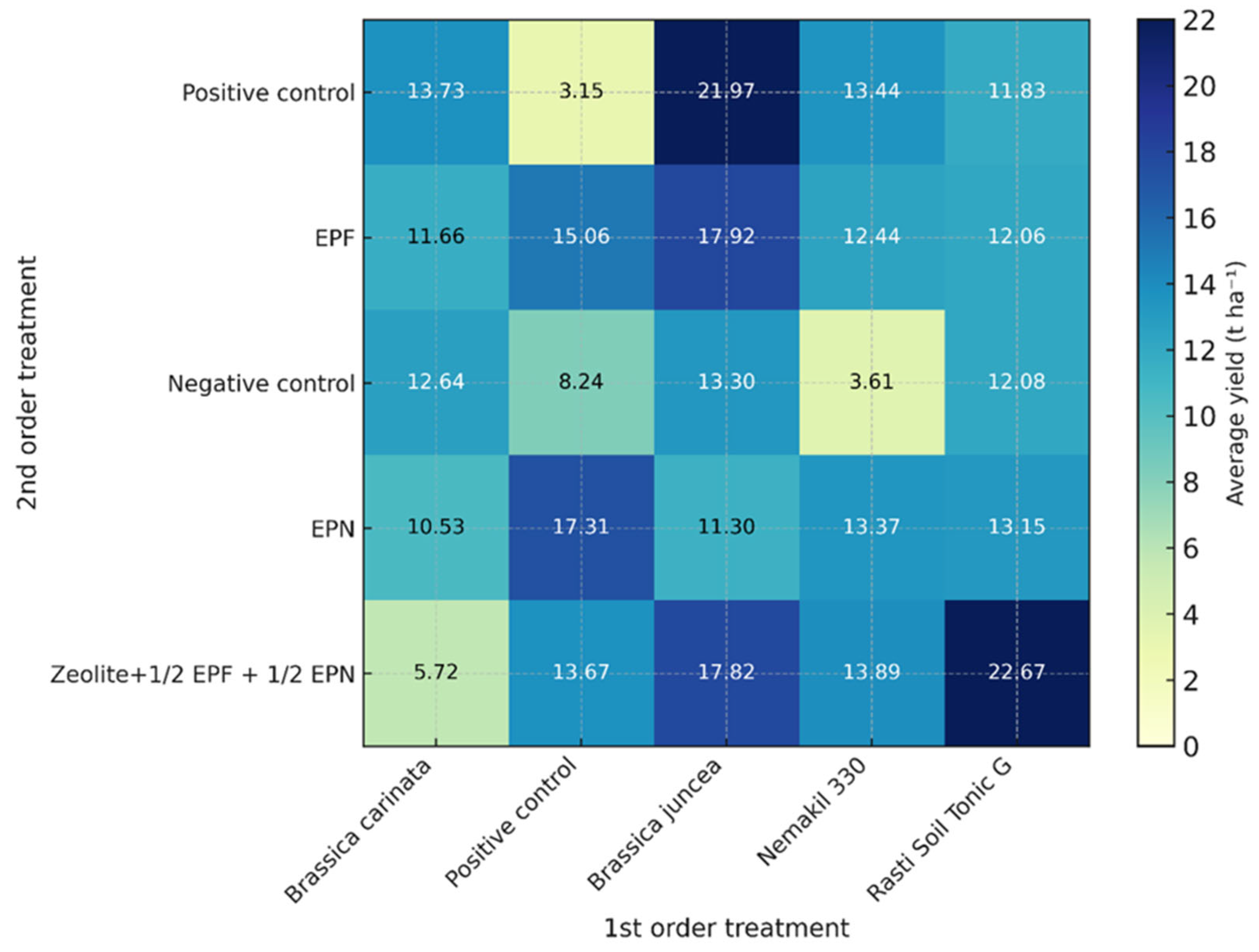

3.4. Display of Average Number of Holes/Tuber by Individual Treatments

We found that the average number of holes per potato tuber depends on the year of assessment (F2,55 = 10.06, p < 0.05). The influence of individual combinations was observed in the first year (F24,130 = 99.15, p < 0.05), the second year (F24,130 = 140.30, p < 0.05), and the third year of the experiment (F24,130 = 150.16, p < 0.05).

In the first year (

Figure 8), we found the highest number of holes per tuber (an average of almost 1 borehole per tuber) on tubers where

Brassica carinata was used as the first-order treatment while zeolites in combination with a reduced concentration of entomopathogens were used as the second-order treatment. In the second year (

Figure 9), for all second-order treatments involving

Brassica carinata as the first-order treatment, the extent of damage on tubers did not exceed 0.2 boreholes per tuber. In the third year (

Figure 10), following the lowest extent of damage per tuber in the

Brassica carinata treatment group, the EPN treatment stood out (an average of 0.2 holes per tuber).

While the combination of insecticide use in both first- and second-order treatments did not result in undamaged tubers, in the combination where Brassica juncea was used as the first-order treatment and an insecticide was added for the second-order treatment, we produced almost undamaged tubers in two out of the three years of research. In two out of the three years of research, when using Brassica juncea (first-order treatment) and the combination of zeolites plus half the concentration of entomopathogens, we recorded an average of less than 0.4 holes per tuber, and in the second year of the research, the tubers from the abovementioned combination of methods were undamaged.

Regarding the solitary use of the Nemakil 330 product (only as a first-order treatment), the average number of holes per tuber did not exceed 0.6 holes per tuber across all three years. When we used the Rasti Soil Tonic G product as the first-order treatment and added the combination of zeolites plus half the concentration of entomopathogens as the second-order treatment, we found damage that did not exceed 0.2 holes per tuber in all three years of research.

3.5. Average Tuber Yield in First-Order Treatments

We found that the average tuber yield differed significantly according to fraction in the first (F2,70 = 25.12, p < 0.05), second (F2,65 = 30.10, p < 0.05), and third (F2,63 = 27.27, p < 0.05) years of research. We also found significant differences in the average total yield among treatments in the first (F4,83 = 2.63, p < 0.05) and second (F4,50 = 7.66, p < 0.05) years, while no differences in the average total yield were found in the third year of research (F4,42 = 9.15, p = 0.0675).

In the first year of research, the average yield of small-fraction tubers was among the lowest in the positive control group (1.30 ± 0.14 t/ha), while we recorded a yield of 1.72 ± 0.17 t/ha in the

Brassica carinata treatment group. The average yield of medium-fraction tubers stood out in the

Brassica juncea treatment group, where we recorded 5.71 ± 0.38 t/ha. The average yield of large-fraction tubers was highest in the

Brassica juncea treatment group, where we detected almost 9 t/ha. The average total yield did not exceed 12 t/ha in the

Brassica carinata treatment group, while we recorded 16t/ha in the

Brassica juncea treatment group (

Figure 11A).

Small-fraction tubers weighed almost 2t/ha when we used

Brassica juncea as the first-order treatment. The highest yield of medium-fraction tubers (almost 6t/ha) and the highest yield of larger tubers (almost 7 t/ha) were also found in the

Brassica juncea treatment group. The average total yield was among the lowest in the

Brassica carinata treatment group, where it exceeded 6 t/ha. The average total yield was among the highest in the

Brassica juncea and Rasti Soil Tonic treatments, reaching 14 t/ha (

Figure 11B).

The average yield of small-fraction tubers did not exceed 5 t/ha in any of the treatment groups. We did not find significant differences among them. We also did not find significant differences in the average yield of medium-fraction tubers, as none exceeded 6 t/ha. In the

Brassica juncea treatment group, we recorded the lowest average yield of large-fraction tubers (25.55 ± 2.52 t/ha), but this did not differ significantly compared to the average yields of the large fraction in the other treatments. We found no differences in the average total yield among the individual treatments, and for all first-order treatments, it was higher than 30 t/ha (

Figure 11C).

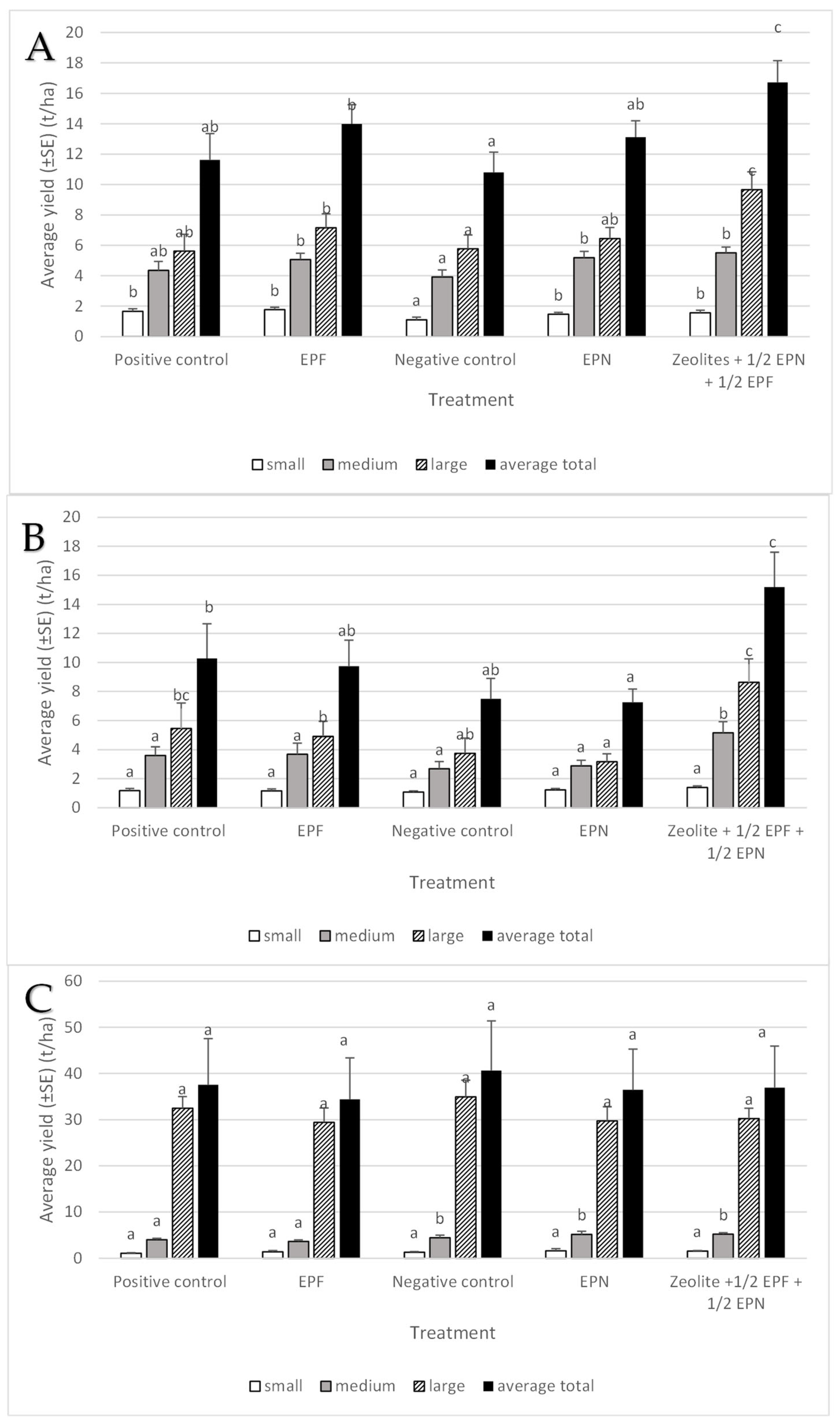

3.6. Average Tuber Yield in Second-Order Treatment

We found that the average yield differed significantly according to the tuber fraction in the first (F

2,70 = 30.40,

p < 0.05), second (F

2,65 = 35.12,

p < 0.05), and third (F

2,63 = 30.05,

p < 0.05) years of research. We also found differences in the average total yield among treatments in the first (F

4,83 = 7.07,

p < 0.05) and second (F

4,50 = 7.66,

p < 0.05) years, while no differences in the average total yield were found in the third year of research (F

4,42 = 20.40,

p = 0.07255). The sorting of potatoes is presented in the

Supplementary File.

The average yield of small-fraction tubers did not exceed 2 t/ha for any of the second-order treatments, although the lowest yield of small-fraction tubers was found in the negative control group (1.10 ± 0.17 t/ha). The average yield of medium-fraction tubers was again among the lowest in the negative control group, at 3.92 ± 0.47 t/ha. The average yield of large-fraction tubers (almost 10 t/ha) was significantly higher when we used zeolites in combination with half the concentration of entomopathogens as the second-order treatment, which were applied to the tubers during planting and to the soil surface just before potato hilling. We also confirmed one of the highest average total yields in the aforementioned treatment group, namely 16 t/ha (

Figure 12A).

Figure 11.

Average tuber yield by fraction according to treatment and average total potato yield in first-order treatments in 2023 (

A), 2024 (

B), and 2025 (

C) (letters indicate differences within the fraction among individual treatments). Details from the statistical analysis are presented in the

Supplementary File.

Figure 11.

Average tuber yield by fraction according to treatment and average total potato yield in first-order treatments in 2023 (

A), 2024 (

B), and 2025 (

C) (letters indicate differences within the fraction among individual treatments). Details from the statistical analysis are presented in the

Supplementary File.

Figure 12.

Average tuber yield by fraction according to treatment and average total potato yield in second-order treatments in the years 2023 (

A), 2024 (

B), and 2025 (

C) (letters indicate differences within the fraction among individual treatments or the yield category (average total) among treatments). Details from the statistical analysis are presented in the

Supplementary File.

Figure 12.

Average tuber yield by fraction according to treatment and average total potato yield in second-order treatments in the years 2023 (

A), 2024 (

B), and 2025 (

C) (letters indicate differences within the fraction among individual treatments or the yield category (average total) among treatments). Details from the statistical analysis are presented in the

Supplementary File.

In 2024, we found low average yields of small-fraction tubers across all the second-order treatments, and the yield did not exceed 1.5 t/ha in any of the treatment groups. The average yield of the medium (approximately 5 t/ha) and large (approximately 8 t/ha) fractions stood out with the combined use of zeolites and half the concentration of both the studied entomopathogens. The average total yield was also highest in the aforementioned treatment group, amounting to 14 t/ha (

Figure 12B).

When we compared the average total yield among individual second-order treatments, we did not find significant differences. However, the average total yield was higher than 30 t/ha for all of them. Similarly, the average yield of large-fraction tubers was higher than 30 t/ha in all treatment groups. The average yield of medium-fraction tubers did not exceed 10 t/ha in any of the treatment groups, and the average yield of the small fraction did not exceed 2t/ha in any of the treatment groups (

Figure 12C).

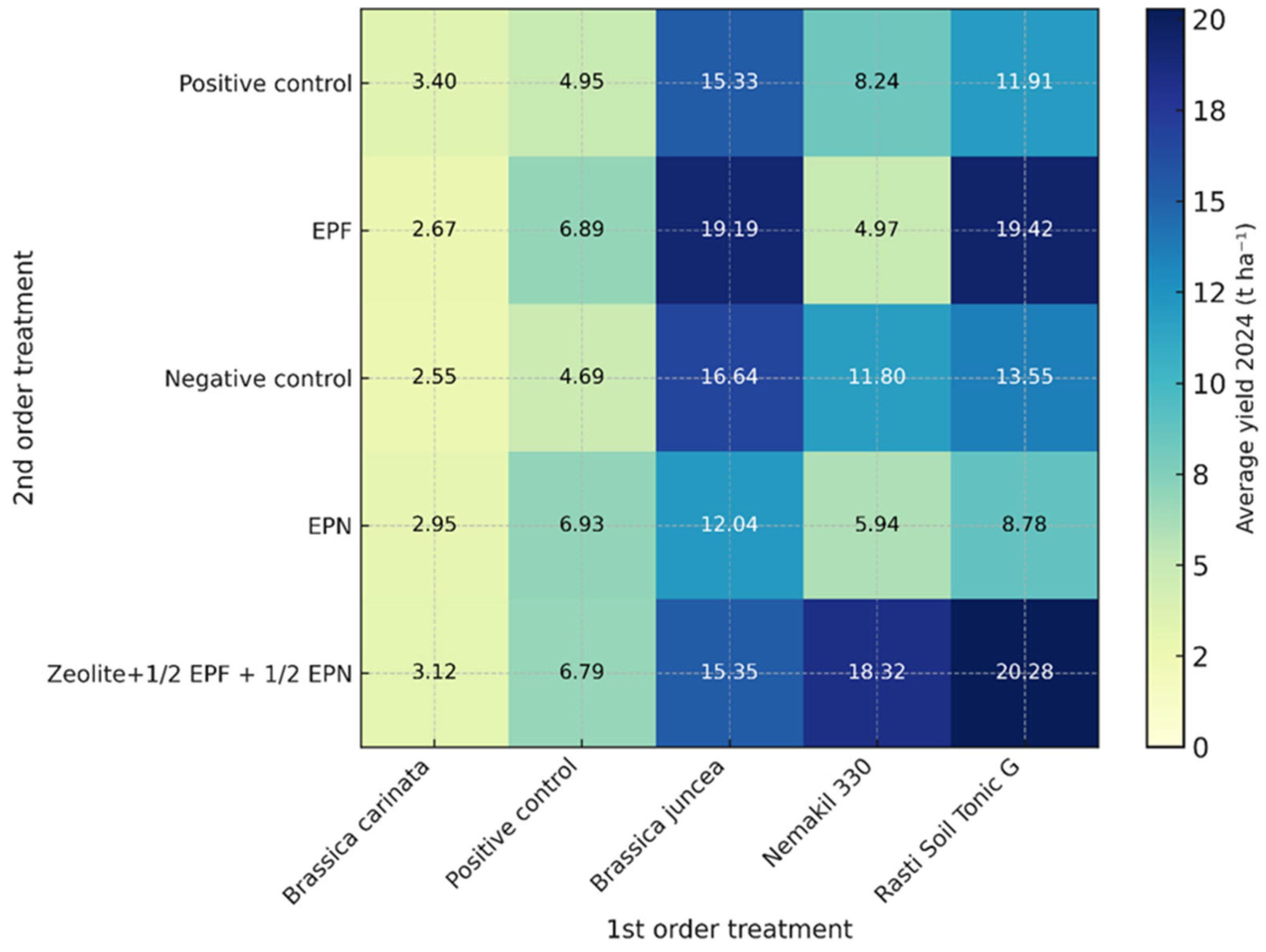

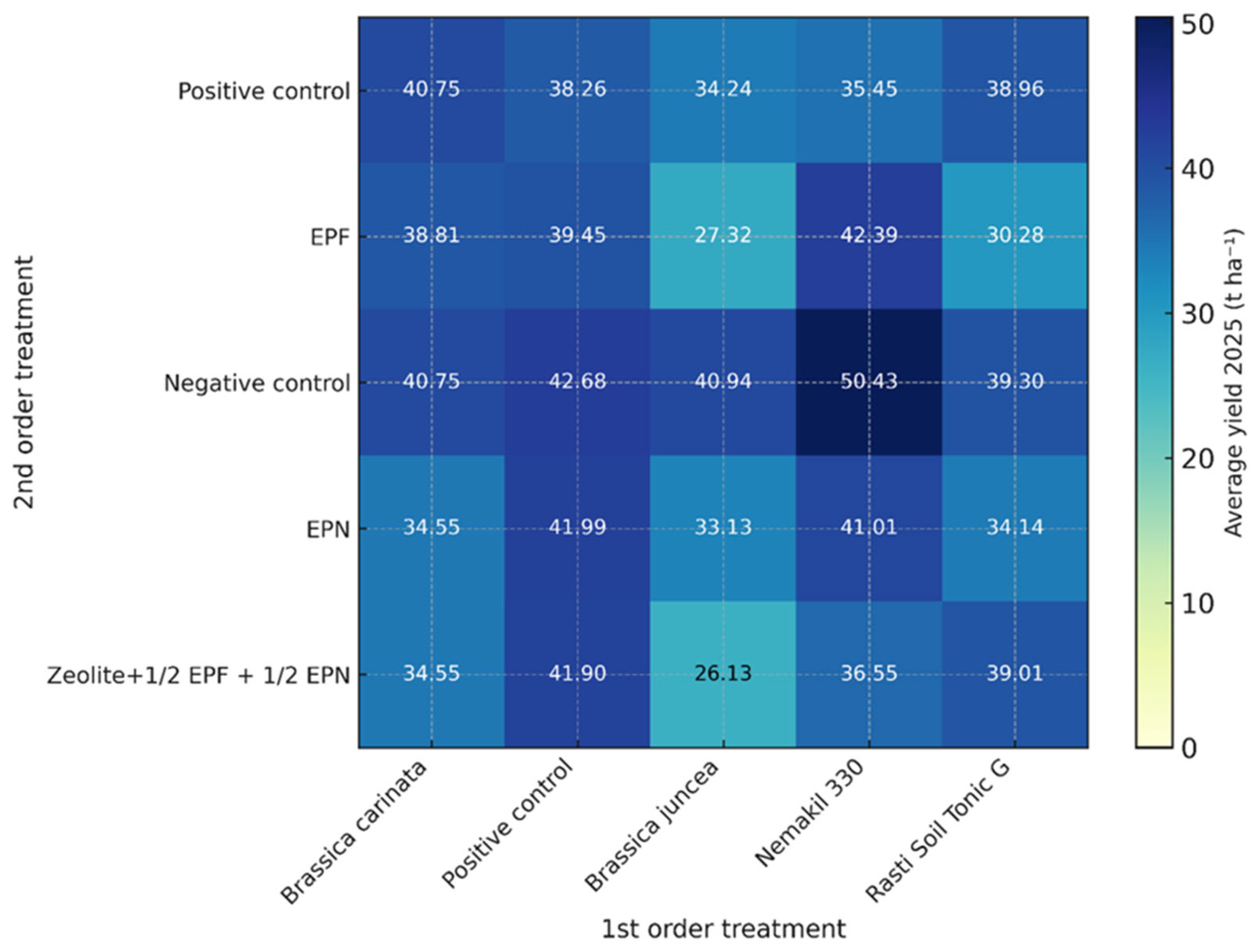

3.7. Display of Average Tuber Yield by Individual Treatments

We found that the average yield differed among the individual combinations in the first (F24,130 = 130.14, p < 0.05), second (F24,130 = 141.12, p < 0.05), and third (F24,130 = 154.60, p < 0.05) years of research.

In the first year of research, we found some of the highest yields for the combination of the

Brassica juncea treatment and the positive control (almost 22 t/ha) and for the combination of the Rasti Soil Tonic G product (first-order treatment) and zeolites plus half the concentration of entomopathogens (almost 23 t/ha). The lowest yields in the first year were found in the positive control treatment group (first- and second-order treatments), where the yield did not exceed 4 t/ha. Similarly, the yield did not exceed 4 t/ha for the combination of the Nemakil 330 treatment (first order) and the negative control (second order) (

Figure 13).

In the second year of research, we obtained a yield of 19.19 ± 0.40 t/ha for the combination of

Brassica juncea (first order) and spraying with EPF (second order). With the combination of the Rasti Soil Tonic G product and zeolites with half the concentration of entomopathogens, we achieved a yield of more than 20 t/ha. On average, the yields were lowest when we used the crucifer

Brassica carinata (first order) and the following second-order treatments: positive control (3.40 ± 0.3 t/ha), EPF (2.68 ± 0.15 t/ha), negative control (2.55 ± 0.20 t/ha), EPN (2.95 ± 0.10 t/ha), and zeolites in combination with half the concentration of entomopathogens (3.12 ± 0.25 t/ha) (

Figure 14).

In the third year of research, we obtained a yield of more than 40 t/ha for the following treatment combinations: Brassica carinata (first order) with positive control (second order), positive control (first order) with negative control (second order), a product based on EPN, and the treatment where we used half the concentration of entomopathogens in combination with zeolites. With the solitary use/sowing of the crucifer Brassica juncea (first order), we also achieved a yield higher than 40 t/ha. Similarly, the solitary use of the Nemakil 330 product led to the highest yield in the third year of research, as we recorded approximately 50 t/ha of potatoes in this treatment group. When we applied Rasti Soil Tonic G as the first-order treatment and zeolites plus half the concentration of entomopathogens as the second-order treatment, we also recorded a yield of almost 40 t/ha (

Figure 15).

3.8. Chemical Analysis of Soil

According to the analysis, P2O5 differed between treatments in the years 2023 (F4,16 = 15.14; p < 0.05), 2024 (F4,16 = 19.13, p < 0.05), and 2025 (F4,16 = 20.10, p < 0.05). There was also a difference between treatments regarding the K2O value in the years 2023 (F4,16 = 15.15, p < 0.05), 2024 (F4,16 = 20.13, p < 0.05), and 2025 (F4,16 = 14.12, p < 0.05). The treatments also influenced the pH value in the years 2023 (F4,16 = 10.14, p < 0.05), 2024 (F4,16 = 24.12, p < 0.05), and 2025 (F4,16 = 9.09, p < 0.05), as well as influencing organic matter in 2023 (F4,16 = 16.10, p < 0.05), 2024 (F4,16 = 22.55, p < 0.05), and 2025 (F4,16 = 11, p < 0.05).

The P

2O

5 content was among the highest in the first year in samples taken from the Nemakil 330 treatment group, while a significantly lower content was recorded in samples where the crucifer

Brassica carinata was sown. The P

2O

5 content in samples taken from the

Brassica carinata treatment group was also among the lowest in the second year of research (19.25 mg/100 g of sample). The P

2O

5 content in soil samples taken from the

Brassica carinata treatment group was among the highest in the third year of research (36.20 ± 6.93 mg/100 g of sample), but we did not find significant differences compared to the other treatments. The K2O content was among the highest in the first two years in the treatment where we used

Brassica juncea, while in the third year, the highest K

2O content was found in samples from the Rasti Soil Tonic G treatment group. In all three years, the lowest pH value was confirmed in soil samples where we used

Brassica carinata. The organic matter content stood out in the Nemakil 330 treatment group in the first and third years, while the largest amount of organic mass in the second year of research was detected in samples taken from the

Brassica carinata and

Brassica juncea treatment groups. Details are presented in the

Supplementary File, specifically Table S2.

4. Discussion

In our research, we focused on studying the effectiveness of various environmentally acceptable methods for wireworm control to reduce the damage they cause to potato tubers. In addition to the primary goal, i.e., pest control or damage reduction (holes) in tubers, we were also interested in the effect of these methods on potato yield and key soil parameters. We studied various environmentally acceptable wireworm control methods in the potato field through both solitary and combined use, as we were primarily interested in the synergistic effects of their combined application. It has already been confirmed in several cases that the solitary use of environmentally acceptable methods does not ensure satisfactory efficacy in controlling wireworms [

15,

16,

20,

21], while their combined use has resulted in greater effectiveness in reducing the harmfulness of these important soil pests [

22,

23].

The timing of product application was carefully adjusted to the bionomics of the target pest group and the specific instructions of the manufacturers to ensure maximum effectiveness of the treatments. In Slovenia, previous studies on biofumigation for wireworm control have used rapeseed, oilseed radish, white mustard, oilseed rape, and kale [

16], but their efficacy was negligibly low. In our research, we included two

Brassica species known for their high glucosinolate content [

8], namely Ethiopian mustard and brown mustard. There are several ways to incorporate crucifers into the soil [

8]; in our research, we ploughed the mulched plant mass into the soil. The actual effect of the plant mass intended for biofumigation on the yield of the cultivated plants has been very rarely explained in previous research, as most of these studies were conducted in pots, e.g., regarding the use of brown mustard (

Brassica juncea) [

6].

Brassica carinata is supposed to enable easier adaptation of plants to summer drought or optimization of plant growth due to dry springs [

24].

In our research, the potato yield among combinations that included

Brassica carinata differed in the first two years, but there were no differences in the third year. This could be attributed to the amount of precipitation in 2025, as June was modest in rainfall, and due to the smaller amount of precipitation in spring (compared to the ten-year average), the water reserves were more distributed, enabling plant growth. The combination of the positive control in the first- and second-order treatments represents the lowest yields in all years of the experiment, which can be attributed to the fact that the remaining first-order treatments (Nemakil 330, Rasti Soil Tonic G, and the two types of crucifers) also function as fertilizers [

25].

High tuber yields were achieved in every year of the three-year study, and this successful outcome was driven by two treatments: Rasti Soil Tonic G (comprising zeolite and unlisted plant extracts) and the mixture of zeolites and entomopathogens at half their standard concentration. The product Nemakil 330, characterized by a substantial proportion of organic matter and supplemented with Neem cake and castor meal, exhibited a synergistic interaction when used as a first-order treatment with the zeolite and half-strength entomopathogen mixture. The addition of Neem cake and castor meal, specifically, contributed to reducing the degree of wireworm feeding damage on potato tubers. Azadirachtin, the main active substance in Neem cake, acts as a repellent to wireworms [

26], while castor acts as an insecticide [

27]. The organic matter in the Nemakil 330 product, on the other hand, acts as a fertilizer. In the literature, we found positive effects of zeolite use on soil [

28], as they improve the soil structure, etc. The potato yields, with the combined use of the Rasti Soil Tonic G product and zeolites in combination with entomopathogens, always exceeded 20 t/ha, and even reached 40 t/ha in the last year. The application of zeolites has been shown to positively affect potato yield, particularly in irrigated production systems [

29]. Notably, zeolite application reduced water consumption. This suggests that incorporating zeolites into potato production systems could significantly improve efficiency across Europe by mitigating water shortages—a growing concern that negatively impacts tuber bulking [

1]—and reducing the overall need for irrigation.

Among the entomopathogenic fungi recognized for having high efficacy against wireworms,

Metarhizium brunneum [

12] and

Metarhizium anisopliae [

5] are frequently cited. However, due to regulatory restrictions on their use in Slovenia, our research utilized

Beauveria bassiana ATCC 74040 [

30], which is locally approved for wireworm management on potato crops.

For the control of wireworms in potatoes, the most commonly referenced entomopathogenic nematodes are

Heterorhabditis bacteriophora and

Steinernema feltiae [

5]. In our study, we selected a commercial product based on

S. feltiae, as it is the only species currently registered in Slovenia for wireworm control [

31]. By applying a combination of the entomopathogenic fungi and nematode products at a reduced concentration along with the addition of zeolite, we achieved control results that were statistically comparable to those of the positive control treatment.

Tuber damage reached its peak significance in the third year of the study. We attribute this increased damage to the crop rotation history [

9]; specifically, the field’s preceding long-term grass cover provided an extremely favourable habitat for wireworm reproduction [

32], which consequently led to a higher incidence of damaged tubers [

3]. Across all years of research, we found no statistical differences in the average number of holes per tuber among the first-order treatments. However, a consistent pattern emerged: damage intensity varied significantly based on tuber size. Specifically, larger tubers consistently exhibited a greater number of wireworm feeding holes across all three years of the experiment [

16,

33].

During the first two years of the experiment, a significant reduction in the average number of holes per tuber was observed among the second-order treatments when utilizing the combination of zeolites and a reduced concentration of entomopathogens (zeolite + 1/2 EPN + ½ EPF). The level of damage recorded in this specific treatment group was statistically comparable to the results achieved using the positive control.

These findings underscore the critical importance of appropriate entomopathogen species selection for effective wireworm control, as studies indicate that choosing an unsuitable species can lead to high ineffectiveness [

34]. Furthermore, our results align with prior research [

10], demonstrating that entomopathogenic fungi are more effective when combined with other environmentally sustainable methods, such as the use of winter oats as a trap crop [

11].

Despite the fact that the average amount of precipitation in the first two years of research was higher than the ten-year average, this did not contribute to more effective action of the entomopathogens, which require soil moisture for optimal functioning [

7].

All treatment methods investigated in our study demonstrated significant efficacy or repellent effects, as evidenced by a statistically significant reduction in the density of wireworms (individuals per m2) following application, as determined by soil excavations.

Our research corroborated the previously documented insecticidal effect of

Brassica juncea and

Brassica carinata on wireworms [

7].

In a study on the effect of cruciferous seed meal on soil microorganisms, no negative effects were found [

24], despite the fact that the concentration of glucosinolates and other substances in the meal was significantly higher than in the mulched and subsequently ploughed above-ground parts of the crucifers. The authors also found that soil amendment with

Brassica carinata seed meal improved the fertility of the soil, since this method has shown positive effects in terms of increasing the total organic carbon content and humified carbon in the soil. With this, we can also confirm for our research the absence of undesirable effects from glucosinolate decomposition products and their suitability for environmentally friendly methods of controlling harmful soil-borne organisms.

According to the manufacturer’s instructions, the Nemakil 330 product [

35] contains 3% total phosphorus pentoxide, which is also evident in the soil analysis samples, as the this compound is most abundant in the Nemakil 330 soil samples. However, this surplus did not significantly affect the yield, as phosphorus does not represent a critical element in potato fertilization [

36].