Enhanced Micropropagation of Lachenalia ‘Rainbow Bells’ and ‘Riana’ Bulblets Using a Temporary Immersion Bioreactor Compared with Solid Medium Cultures

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material

2.2. Culture Systems Used for Propagation

2.3. Morphometric Observations

2.4. Biochemical Analysis

2.4.1. Photosynthetic Pigment Content

2.4.2. Total Phenolic Compounds Content

2.4.3. Soluble Sugar Content

2.5. Statistical Data Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

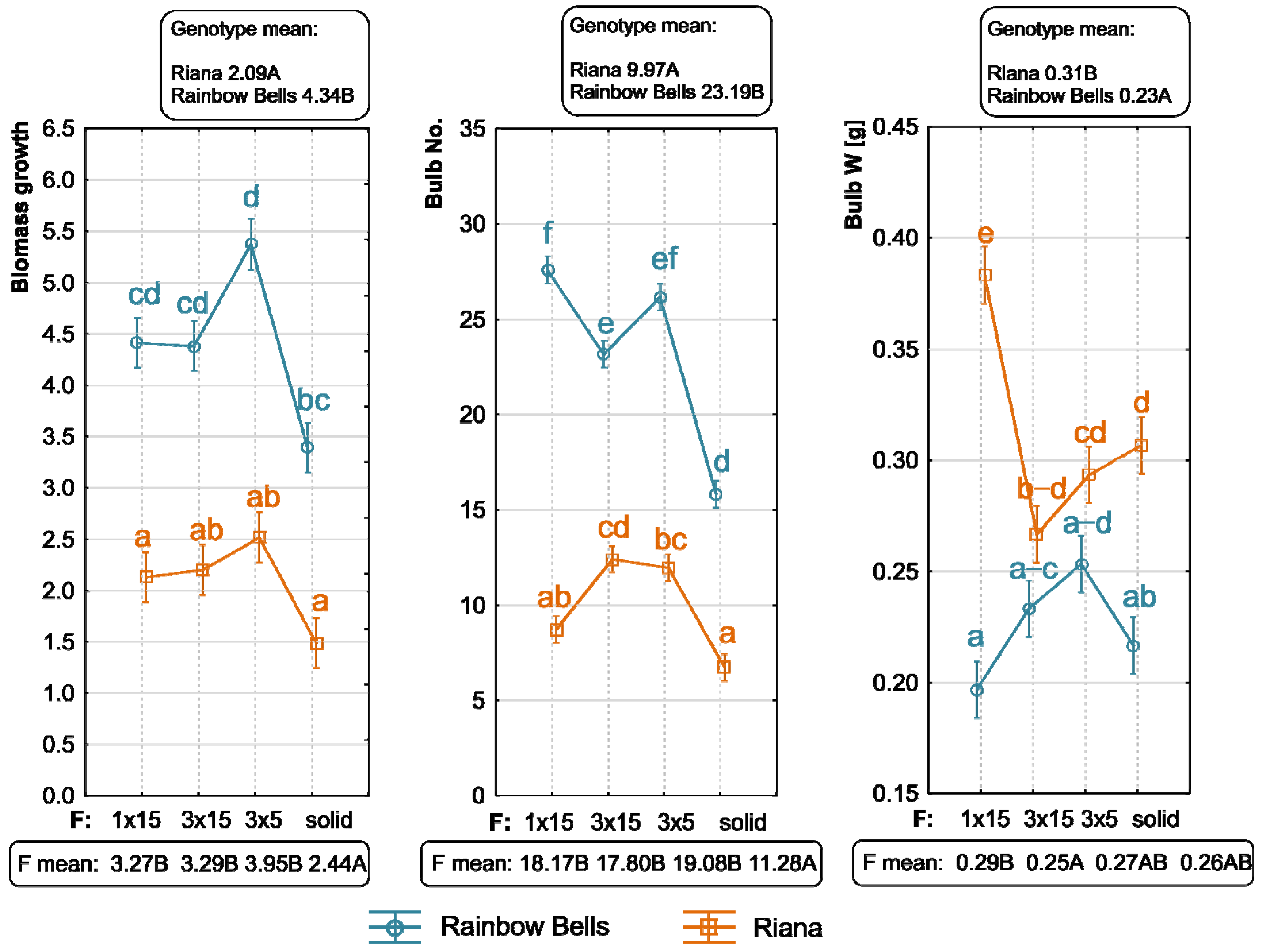

3.1. Genotype Effect

3.2. TIB Effect

3.3. Interaction Between Genotype and Immersion Frequency

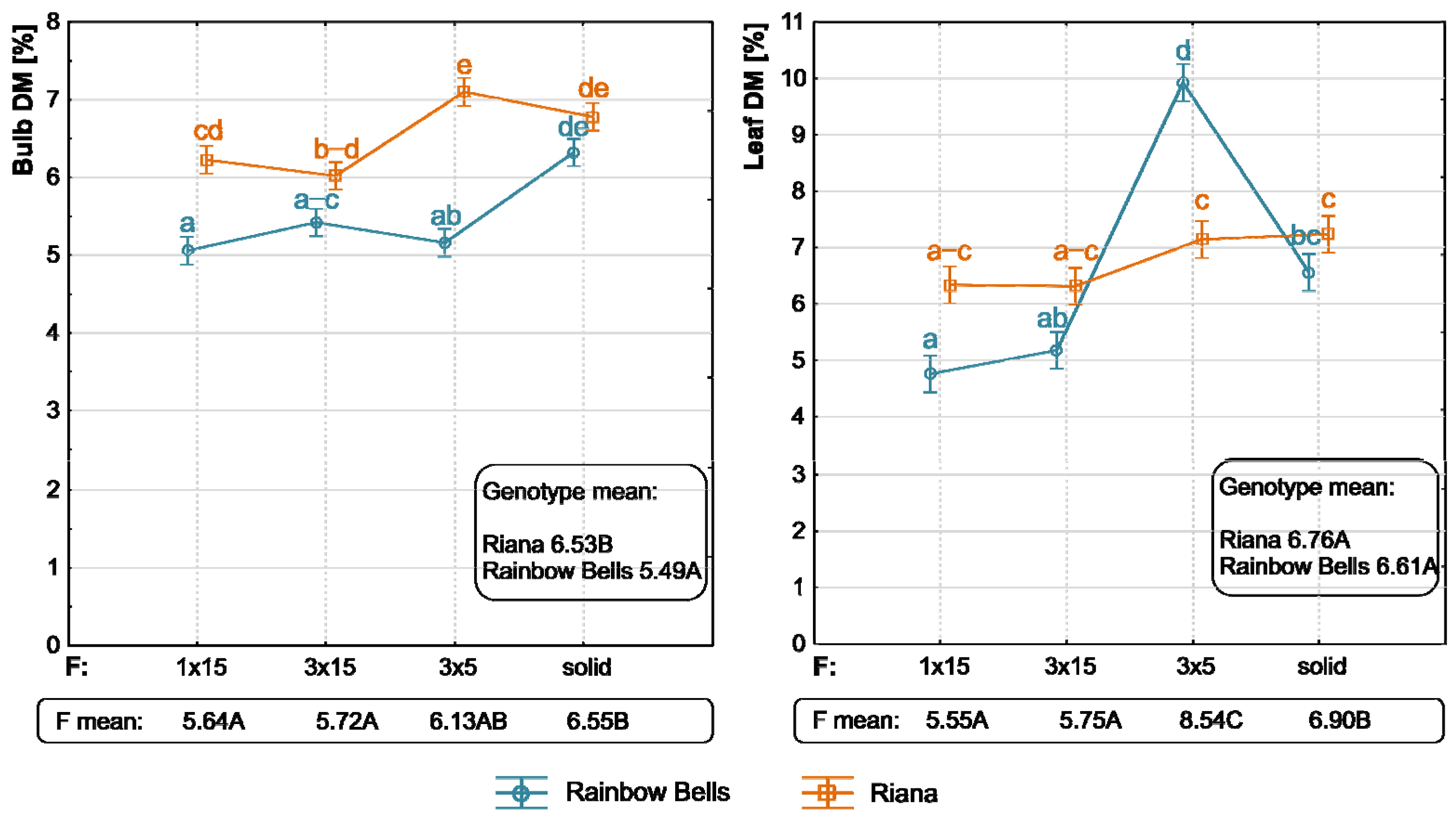

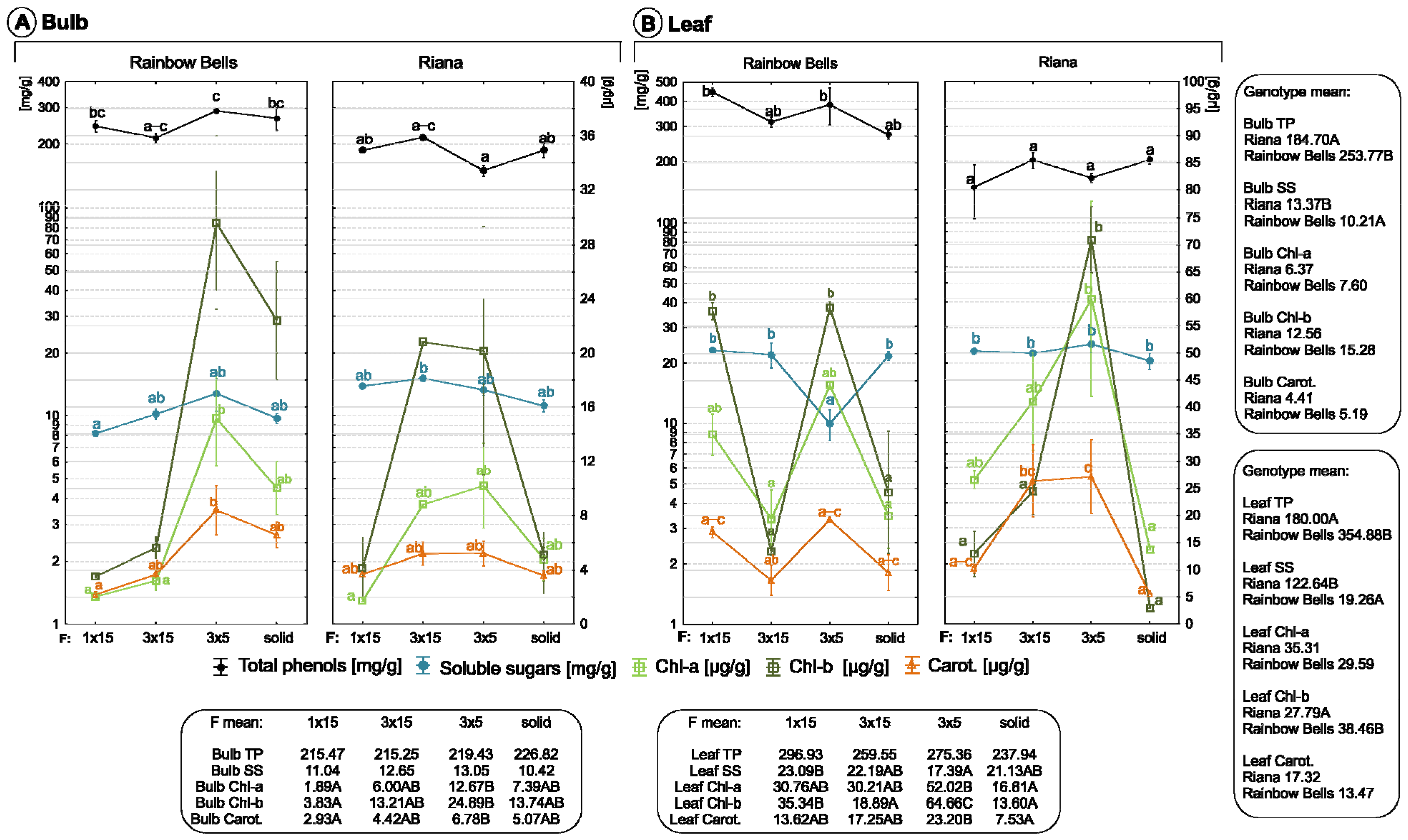

3.4. Effect of Culture System on Biochemical Parameters

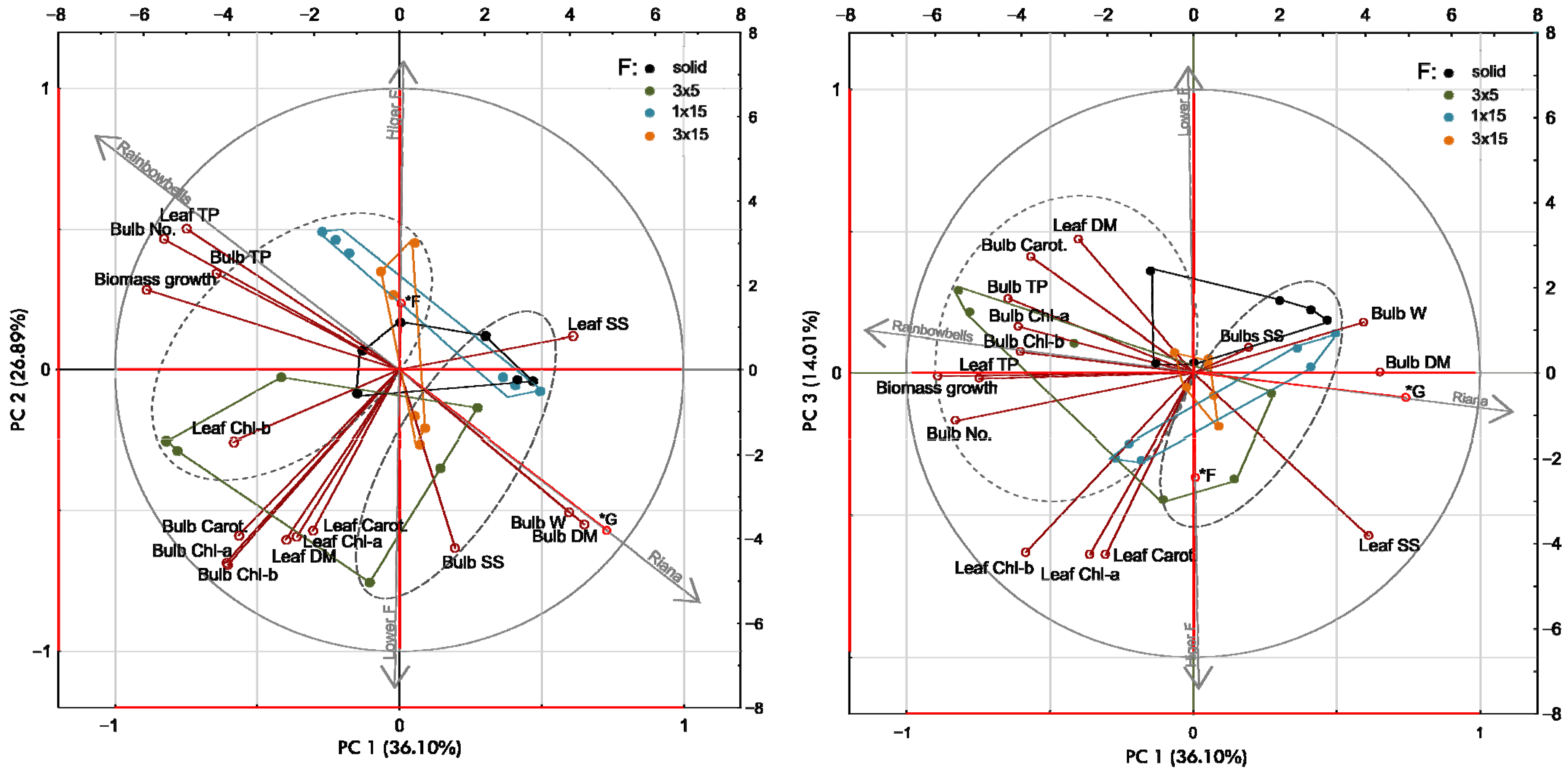

3.5. Structure of Trait Interrelations

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TIB | Temporary immersion bioreactor |

| MS | Murashige and Skoog (1962) medium |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| Bulb W | Bulb weight |

| Bulb No. | Bulb number per 1 g of initial tissue |

| Bulb DM | Bulb dry matter content |

| Bulb TP | Total phenolics content in bulbs |

| Bulb SS | Soluble sugars content in bulbs |

| Bulb Chl-a | Chlorophyll a content in bulbs |

| Bulb Chl-b | Chlorophyll b content in bulbs |

| Bulb Carot. | Carotenoid content in bulbs |

| Leaf DM | Leaf dry matter content |

| Leaf TP | Total phenolics content in leaves |

| Leaf SS | Soluble sugars content in leaves |

| Leaf Chl-a | Chlorophyll a content in leaves |

| Leaf Chl-b | Chlorophyll b content in leaves |

| Leaf Carot. | Carotenoid content in leaves |

References

- Kleynhans, R. Lachenalia, spp. In Flower Breeding & Genetics: Issues, Challenges, and Opportunities for the 21st Century; Anderson, N.O., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2006; pp. 491–516. [Google Scholar]

- Kapczyńska, A. Morphological and botanical profile of Lachenalia cultivars. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2022, 147, 472–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapczyńska, A.; Maślanka, M.; Mazur, J. Longevity of Lachenalia cut flowers. Acta Hortic. 2025, 1435, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, G. The Genus Lachenalia: A Botanical Magazine Monograph; Kew Publishing, Royal Botanic Gardens: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Maślanka, M.; Kapczyńska, A. Cold treatment promotes in vitro germination of two endangered Lachenalia species. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2021, 142, 430–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maślanka, M.; Mazur, J.; Kapczyńska, A. In Vitro Organogenesis of Critically Endangered Lachenalia viridiflora. Agronomy 2022, 12, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapczyńska, A. Propagation of Lachenalia cultivars from leaf cuttings. Acta Sci. Pol. Hortorum Cultus 2019, 18, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapczyńska, A. Effect of chipping and scoring techniques on bulb production of Lachenalia cultivars. Acta Agrobot. 2019, 72, 1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapczyńska, A. Critically endangered Lachenalia viridiflora—From seeds to flowering bulbs. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2023, 157, 228–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Naggar, H.M.; Shehata, A.M.; Moubarak, M.; Osman, A.R. Optimization of Morphogenesis and In Vitro Production of Five Hyacinthus orientalis Cultivars. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkov, S.; Georgieva, L.; Sidjimova, B.; Nikolova, M.; Stanilova, M.; Bastida, J. In vitro propagation and biosynthesis of Sceletium-type alkaloids in Narcissus pallidulus and Narcissus cv. Hawera. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2021, 136, 190–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi Khonakdari, M.; Rezadoost, H.; Heydari, R.; Mirjalili, M.H. Effect of photoperiod and plant growth regulators on in vitro mass bulblet proliferation of Narcissus tazzeta L. (Amaryllidaceae), a potential source of galantamine. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2020, 142, 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sochacki, D.; Marciniak, P.; Ciesielska, M.; Zaród, J.; Sutrisno. The Influence of Selected Plant Growth Regulators and Carbohydrates on In Vitro Shoot Multiplication and Bulbing of the Tulip (Tulipa L.). Plants 2023, 12, 1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podwyszyńska, M.; Marasek-Ciolakowska, A. Micropropagation of Tulip via Somatic Embryogenesis. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bach, A.; Kapczyńska, A.; Dziurka, K.; Dziurka, M. Phenolic compounds and carbohydrates in relation to bulb formation in Lachenalia ‘Ronina’ and ‘Rupert’ in vitro cultures under different lighting environments. Sci. Hortic. 2015, 188, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bach, A.; Kapczyńska, A.; Dziurka, K.; Dziurka, M. The importance of applied light quality on the process of shoot organogenesis and production of phenolics and carbohydrates in Lachenalia sp. cultures in vitro. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2018, 114, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etienne, H.; Berthouly, M. Temporary immersion systems in plant micropropagation. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2002, 69, 215–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziv, M. Simple bioreactors for mass propagation of plants. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2005, 81, 277–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiev, V.; Schumann, A.; Pavlov, A.; Bley, T. Temporary immersion systems in plant biotechnology. Eng. Life Sci. 2014, 14, 607–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mujib, A.; Ali, M.; Isah, T.; Dipti. Somatic embryo mediated mass production of Catharanthus roseus in culture vessel (bioreactor)—A comparative study. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2014, 21, 442–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Carlo, A.; Tarraf, W.; Lambardi, M.; Benelli, C. Temporary Immersion System for Production of Biomass and Bioactive Compounds from Medicinal Plants. Agronomy 2021, 11, 2414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afreen, F. Temporary Immersion Bioreactor. In Plan Tissue Culture Engineering; Gupta, S.D., Ibaraki, Y., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2007; Volume 6, pp. 187–201. [Google Scholar]

- Mirzabe, A.H.; Hajiahmad, A.; Fadavi, A.; Rafiee, S. Temporary immersion systems (TISs): A comprehensive review. J. Biotechnol. 2022, 357, 56–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskaran, P.; Van Staden, J. Ultrastructure of somatic embryo development and plant propagation for Lachenalia montana. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2017, 109, 269–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascough, G.D.; van Staden, J.; Erwin, J.E. In Vitro Storage Organ Formation of Ornamental Geophytes. In Horticultural Reviews; Janick, J., Ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007; Volume 34, pp. 417–445. [Google Scholar]

- Murashige, T.; Skoog, F. A Revised Medium for Rapid Growth and Bio Assays with Tobacco Tissue Cultures. Physiol. Plant. 1962, 15, 473–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenthaler, H.K. [34] Chlorophylls and carotenoids: Pigments of photosynthetic biomembranes. In Plant Cell Membranes, Methods in Enzymology; Packer, L., Douce, R., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1987; Volume 148, pp. 350–382. [Google Scholar]

- Singleton, V.L.; Rossi, J.A. Colorimetry of Total Phenolics with Phosphomolybdic-Phosphotungstic Acid Reagents. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1965, 16, 144–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, B.K.; Choudhury, B.K.; Kar, M. Quantitative estimation of changes in biochemical constituents of mahua (Madhuca indica syn. bassia latifolia) flowers during postharvest storage. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2010, 34, 831–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis, 8th ed.; Cengage: Andover, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kornbrot, D. Point Biserial Correlation. In Wiley StatsRef: Statistics Reference Online; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Jasenovska, L.; Brestic, M.; Barboricova, M.; Ferencova, J.; Filacek, A.; Zivcak, M. Analysis of the effects of various light spectra on microgreen species. Folia Hortic. 2024, 36, 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Sarsaiya, S.; Pan, X.; Jin, L.; Xu, D.; Zhang, B.; Duns, G.J.; Shi, J.; Chen, J. Optimization of nutritional conditions using a temporary immersion bioreactor system for the growth of Bletilla striata pseudobulbs and accumulation of polysaccharides. Sci. Hortic. 2018, 240, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minchala-Buestán, N.; Hoyos-Sánchez, R.A.; Correa-Londoño, G.A. Micropropagation of iraca palm (Carludovica palmata Ruiz y Pav) using a temporary immersion system. Vitr. Cell. Dev. Biol. Plant 2023, 59, 563–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez-Hernández, H.A.; Loyola-Vargas, V.M. Plant Micropropagation and Temporary Immersion Systems. In Plant Cell Culture Protocols. Methods in Molecular Biology; Loyola-Vargas, V., Ochoa-Alejo, N., Eds.; Humana: New York, NY, USA, 2024; Volume 2827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Mosqueda, M.A.; Cruz-Cruz, C.A.; Cano-Ricárdez, A.; Bello-Bello, J.J. Assessment of different temporary immersion systems in the micropropagation of anthurium (Anthurium andreanum). 3 Biotech 2019, 9, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bello-Bello, J.J.; Schettino-Salomón, S.; Ortega-Espinoza, J.; Spinoso-Castillo, J.L. A temporary immersion system for mass micropropagation of pitahaya (Hylocereus undatus). 3 Biotech 2021, 11, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monja-Mio, K.M.; Olvera-Casanova, D.; Herrera-Alamillo, M.Á.; Sánchez-Teyer, F.L.; Robert, M.L. Comparison of conventional and temporary immersion systems on micropropagation (multiplication phase) of Agave angustifolia Haw. ‘Bacanora’. 3 Biotech 2021, 11, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uma, S.; Karthic, R.; Kalpana, S.; Backiyarani, S.; Saraswathi, M.S. A novel temporary immersion bioreactor system for large scale multiplication of banana (Rasthali AAB—Silk). Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 20371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarraf, W.; İzgü, T.; Şimşek, Ö.; Cicco, N.; Benelli, C. Saffron In Vitro Propagation: An Innovative Method by Temporary Immersion System (TIS), Integrated with Machine Learning Analysis. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aremu, A.O.; Plačková, L.; Masondo, N.A.; Amoo, S.O.; Moyo, M.; Novák, O.; Doležal, K.; Van Staden, J. Regulating the regulators: Responses of four plant growth regulators during clonal propagation of Lachenalia montana. Plant Growth Regul. 2017, 82, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pałka, P.; Malik, M.; Pawłowska, B. Effects of pretreatment in a temporary immersion bioreactor on organogenesis efficacy of Lilium candidum L. bulbscales. Acta Soc. Bot. Pol. 2024, 93, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arano-Avalos, S.; Gómez-Merino, F.C.; Mancilla-Álvarez, E.; Sánchez-Páez, R.; Bello-Bello, J.J. An efficient protocol for commercial micropropagation of malanga (Colocasia esculenta L. Schott) using temporary immersion. Sci. Hortic. 2020, 261, 108998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gago, D.; Vilavert, S.; Bernal, M.Á.; Sánchez, C.; Aldrey, A.; Vidal, N. The Effect of Sucrose Supplementation on the Micropropagation of Salix viminalis L. Shoots in Semisolid Medium and Temporary Immersion Bioreactors. Forests 2021, 12, 1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daurov, D.; Daurova, A.; Sapakhova, Z.; Kanat, R.; Akhmetzhanova, D.; Abilda, Z.; Toishimanov, M.; Raissova, N.; Otynshiyev, M.; Zhambakin, K.; et al. The Impact of the Growth Regulators and Cultivation Conditions of Temporary Immersion Systems (TISs) on the Morphological Characteristics of Potato Explants and Microtubers. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mommer, L.; Pons, T.L.; Wolters-Arts, M.; Venema, J.H.; Visser, E.J.W. Submergence-Induced Morphological, Anatomical, and Biochemical Responses in a Terrestrial Species Affect Gas Diffusion Resistance and Photosynthetic Performance. Plant Physiol. 2005, 139, 497–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grace, S.C.; Logan, B.A. Energy dissipation and radical scavenging by the plant phenylpropanoid pathway. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 2000, 355, 1499–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akula, R.; Ravishankar, G.A. Influence of abiotic stress signals on secondary metabolites in plants. Plant Signal. Behav. 2011, 6, 1720–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Ren, Z.; Gao, C.; Sun, M.; Li, S.; Min, R.; Wu, J.; Li, D.; Wang, X.; Wei, Y.; et al. Change in Sucrose Cleavage Pattern and Rapid Starch Accumulation Govern Lily Shoot-to-Bulblet Transition in vitro. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 11, 564713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Le Gourrierec, J.; Jiao, F.; Demotes-Mainard, S.; Perez-Garcia, M.-D.; Ogé, L.; Hamama, L.; Crespel, L.; Bertheloot, J.; Chen, J.; et al. Convergence and Divergence of Sugar and Cytokinin Signaling in Plant Development. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wingler, A.; Henriques, R. Sugars and the speed of life—Metabolic signals that determine plant growth, development and death. Physiol. Plant. 2022, 174, e13656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gago, D.; Sánchez, C.; Aldrey, A.; Christie, C.B.; Bernal, M.Á.; Vidal, N. Micropropagation of Plum (Prunus domestica L.) in Bioreactors Using Photomixotrophic and Photoautotrophic Conditions. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Estrada, E.; Islas-Luna, B.; Pérez-Sato, J.A.; Bello-Bello, J.J. Temporary immersion improves in vitro multiplication and acclimatization of Anthurium andreanum Lind. Sci. Hortic. 2019, 249, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Source of Variations | df | Mean Squares | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biomass Growth | Bulb No. | Bulb W [g] | Bulb DM [%] | Leaf DM [%] | ||

| Genotype (G) | 1 | 31.8782 *** | 1049.801 *** | 0.045938 *** | 6.5208 *** | 0.141 NS |

| Immersion frequency (F) | 3 | 2.2817 *** | 76.782 *** | 0.001749 ** | 1.0515 *** | 11.293 *** |

| G × F | 3 | 0.2422 NS | 28.005 *** | 0.007515 *** | 0.6784 ** | 5.939 *** |

| Error | 16 | 0.1778 | 1.481 | 0.000483 | 0.094 | 0.319 |

| Source of Variations | df | Mean Squares | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bulb SS [mg/g] | Bulb TP [mg/g] | Bulb Chl-a [µg/g] | Bulb Chl-b [µg/g] | Bulb Carot. [µg/g] | Leaf SS [mg/g] | Leaf TP [mg/g] | Leaf Chl-a [µg/g] | Leaf Chl-b [µg/g] | Leaf Carot. [µg/g] | ||

| Genotype (G) | 1 | 59.63 ** | 28.614 *** | 9.064 NS | 44.4 NS | 3.7143 NS | 68.41 * | 183.479 *** | 196.25 NS | 681.99 ** | 89.258 NS |

| Immersion frequency (F) | 3 | 9.542 NS | 175 NS | 118.71 ** | 445.5 * | 15.328 * | 37.6 * | 3730 NS | 1270.66 ** | 3166.07 *** | 259.008 ** |

| G × F | 3 | 9.783 NS | 5154 * | 38.929 NS | 295.4 * | 10.548 NS | 89.01 *** | 15.946 * | 348.2 NS | 1143.46 *** | 197.849 * |

| Error | 16 | 4.289 | 1085 | 16.861 | 85.08 | 3.5066 | 9.15 | 3765 | 182.41 | 76.74 | 41.529 |

| Characters | Principal Components | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| PC1 | PC2 | PC3 | |

| Bulb SS | 0.196538 | −0.633739 | 0.089258 |

| Bulb TP | −0.643259 | 0.341587 | 0.261829 |

| Bulb Chl-a | −0.607619 | −0.682935 | 0.162195 |

| Bulb Chl-b | −0.602440 | −0.691973 | 0.074118 |

| Bulb Carot. | −0.565218 | −0.587924 | 0.408866 |

| Biomass growth | −0.890462 | 0.284464 | −0.011190 |

| Bulb No. | −0.827668 | 0.464977 | −0.170425 |

| Bulb W | 0.595261 | −0.503824 | 0.178352 |

| Bulb DM | 0.650620 | −0.548805 | 0.000380 |

| Leaf DM | −0.398980 | −0.603072 | 0.471821 |

| Leaf SS | 0.612175 | 0.118090 | −0.573838 |

| Leaf TP | −0.747682 | 0.500871 | −0.020421 |

| Leaf Chl-a | −0.359915 | −0.593045 | −0.637310 |

| Leaf Chl-b | −0.583516 | −0.255991 | −0.630953 |

| Leaf Carot. | −0.304452 | −0.571616 | −0.638755 |

| Eigen Value | 5.42 | 4.03 | 2.10 |

| Percentage of Variance | 36.1 | 26.89 | 9.45 |

| Cumulative% of Variance | 36.10 | 62.99 | 77.00 |

| *G | 0.728975 | −0.568443 | −0.085398 |

| *F | 0.006678 | 0.237165 | −0.360214 |

| Characters | Genotype |

|---|---|

| Bulb SS | 0.565863 |

| Bulb TP | −0.679555 |

| Bulb Chl-a | −0.109804 |

| Bulb Chl-b | −0.110616 |

| Bulb Carot. | −0.164387 |

| Biomass Growth | −0.868160 |

| Bulb No. | −0.869722 |

| Bulb weight | 0.750939 |

| Bulb DM | 0.702457 |

| Leaf DM | 0.049772 |

| Leaf SS | 0.339187 |

| Leaf TP | −0.778492 |

| Leaf Chl-a | 0.156907 |

| Leaf Chl-b | −0.214384 |

| Leaf Carot. | 0.204982 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Malik, M.; Kapczyńska, A.; Copetta, A.; Mazur, J.; Savona, M.; Cassetti, A.; Montone, M.; Maślanka, M. Enhanced Micropropagation of Lachenalia ‘Rainbow Bells’ and ‘Riana’ Bulblets Using a Temporary Immersion Bioreactor Compared with Solid Medium Cultures. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2757. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122757

Malik M, Kapczyńska A, Copetta A, Mazur J, Savona M, Cassetti A, Montone M, Maślanka M. Enhanced Micropropagation of Lachenalia ‘Rainbow Bells’ and ‘Riana’ Bulblets Using a Temporary Immersion Bioreactor Compared with Solid Medium Cultures. Agronomy. 2025; 15(12):2757. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122757

Chicago/Turabian StyleMalik, Małgorzata, Anna Kapczyńska, Andrea Copetta, Justyna Mazur, Marco Savona, Arianna Cassetti, Michela Montone, and Małgorzata Maślanka. 2025. "Enhanced Micropropagation of Lachenalia ‘Rainbow Bells’ and ‘Riana’ Bulblets Using a Temporary Immersion Bioreactor Compared with Solid Medium Cultures" Agronomy 15, no. 12: 2757. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122757

APA StyleMalik, M., Kapczyńska, A., Copetta, A., Mazur, J., Savona, M., Cassetti, A., Montone, M., & Maślanka, M. (2025). Enhanced Micropropagation of Lachenalia ‘Rainbow Bells’ and ‘Riana’ Bulblets Using a Temporary Immersion Bioreactor Compared with Solid Medium Cultures. Agronomy, 15(12), 2757. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122757