Abstract

Biochar produced from phosphorus (P)-rich feedstocks has often been promoted as an alternative P fertilizer. However, existing evidence has mainly been obtained from incubation experiments and field trials with a rather short duration, leaving uncertainty about whether repeated low-rate applications of biochar can meaningfully supply P and increase soil P pools over time. This study evaluates the agronomic effects of 10 years of application of biochar derived from plant biowaste (BIO) and bones (BC) at an application rate of 4 t ha−1 yr−1, compared with a mineral P fertilizer (MIN), compost application (COM), and a zero-P control. The application of P through BC and COM led to higher total soil P concentrations than the control. Changes in labile P pools (H2O–P, NaHCO3–P, Bray-P) were generally modest, but BC again tended to yield higher values relative to the other treatments. The ratio of organic to inorganic P was not influenced by fertilizer type. A clear effect of the amendments on maize yield was observed, with BC producing the highest yields among all amendments (6.4 t ha−1; average 2020–2023), and yields were occasionally further increased when BC was combined with COM. The BIO treatments also achieved yields that were at least comparable to those of the MIN treatment (4.7 t ha−1). Despite the limited effects on labile soil P pools, the amendments increased yields and can be considered effective substitutes for mineral P fertilizers at this application rate.

1. Introduction

In modern agriculture, mineral phosphorus (P) fertilizers are challenged by several factors, such as depletion of rock phosphate reserves [1,2], high prices, and limited access for smallholder farmers [3,4], as well as environmental concerns (i.e., contamination with heavy metals) [5]. Over 40% of agricultural soils are estimated to be severely deficient in P [6]. In most tropical African countries, the Green Revolution was not successful among smallholder farmers, who are responsible for the majority of food production. Therefore, innovative approaches for P recovery must be developed to address both environmental concerns and the increasing global demand for agricultural P. Substantial amounts of P are present in various waste streams, including human excreta, wastewater, sludge, crop residues, manure, and animal bones [7,8,9]. For example, the recovery of P from wastewater alone has the potential to meet 15–20% of global P demand [10].

Biochar—a carbon-rich by-product produced under an oxygen-depleted environment (i.e., pyrolysis)—is gaining traction as the next-generation intervention to intensify food production with reduced climate impacts [11]. Charring concentrates P to levels several times higher than those in unpyrolyzed organic materials, making biochar a potential P soil amendment [12,13]. It also reduces waste volume and pathogen risk [14,15] and increases the proportion of highly recalcitrant carbon, thereby enhancing long-term soil carbon storage [16].

Biochar research has grown almost exponentially over the last decade because of its wider areas of application, including climate change mitigation and adaptation [17,18,19], as an alternative for mineral P fertilizer [8,20,21], and environmental remediation [22]. The recalcitrant nature of biochar makes it suitable for technology on highly weathered tropical soil, where rapid depletion of applied organic matter due to fast mineralization is a challenge for sustainable agriculture and a healthy ecosystem.

Despite the fact that biochar research largely expanded over the last two decades, many of the previous studies were incubation, greenhouse, and short-term field trials [8,23]. Short-term studies often fail to capture the complex and time-dependent interactions between biochar, soil properties, climate, and management practices [11,24]. Biochar is persistent/recalcitrant in the soil system and long-term field experiments, like our study, provide a more realistic and reliable assessment of biochar’s agronomic and environmental benefits.

Soil P exists in inorganic (35 to 70%) and organic (approximately 30 to 65%) forms that range from ions in solution to very stable inorganic and organic compounds [25]. The inorganic P (Pi) primarily couples with amorphous and crystalline forms of Al, Fe, and Ca, and exists in three distinct pools: plant-available, sorbed, and mineral P [26,27]. Conventionally, agricultural research on P has primarily focused on its plant-available forms. In soils with low Olsen P, the decline in Olsen P accounted for only about 10% of the total P removed in harvested crops, suggesting that plant-available P was replenished by P derived from other soil pools not captured by the Olsen method [28]. This underscores the need for precise characterization of the various P forms to improve understanding of P dynamics and to provide a foundation for more effective P management.

Although biochar generally improves soil quality [8], its effects on plant-available P vary, ranging from positive [8,29] to negligible or neutral [30]. Such a variability is caused by the heterogeneity of biochar resulting from feedstock, soil properties, climate, experimental duration, and pyrolysis conditions, and due to the complexity of the physio-biochemical characteristics and microbiological processes underlying its effects, biochar exhibits different responses under different conditions [29,31]. For instance, biochar has a greater positive effect on poor and acidic soil than on fertile soil [13,29].

Biochar application could alter soil P forms through liming effects [21,29], direct release of P to the soil [8], and altering soil’s physicochemical properties [20,21]. Additionally, biochar can alter P fractions through its effects on P-solubilizing enzyme activities [32,33]. Nevertheless, previous studies on the impact of biochar-based fertilizer management have mostly focused on plant-available P and agronomic yields [8,31]. However, single extraction methods often fail to predict P availability as they do not provide quantitative information on the P replenishing ability of soils [34]. Depending on the chemical extractants in use, the amount of P that could be mobilized and taken up by plants is either overestimated or underestimated [35]. For instance, many standard soil test P methods overlook parts of organic P, which is a major source of plant-available P during times of scarcity, particularly in heavily weathered tropical soils like our experimental site [36]. P fractionation is important for diagnosing the current bioavailability and gives insight into future long-term soil P supply. Part of biochar’s P, taking part in medium and longer-term transformations to replenish available P, can be best examined by sequential fractionation [37]. Additionally, other methods like the soil P-sorption capacity (PSC) are in use to describe P behavior and availability in soil based on the amounts of iron and aluminum oxides (Fe-ox and Al-ox).

While some studies have investigated the effect of BIO and BC based soil amendments on soil P pools, they have mainly been carried out for short periods [15,23]. Information on continuous long-term biochar applications under field conditions is limited. As biochar ages in the soil, the physical fragmentation increases, functional groups are formed, and surface charge changes from net positive to net negative [38,39], thereby accelerating interactions of biochar with soil. The physical and biochemical transformation of biochar in soil is expected to have different effects on soil P fractions as compared to short-term studies. Stable P in biochar or bone char accounts for more than half of the total P [40] and is thus expected to gradually increase labile and bioavailable P over time, which would be best explained by long-term studies like our experiment. In addition, many previous studies have applied at a high rate (>10 t ha−1 to 150 t ha−1) to optimize its positive effects [8]. Nevertheless, high application rates are not practically applicable under low-input farming systems due to limited biomass availability, production, transportation, and application cost. Therefore, we applied 4 t ha−1 of the soil amendments continuously for nine years to mimic the low-input cropping systems. We hypothesized that (1) long-term application of biochar derived from plant biowaste (BIO) and bones (BC) enhances plant P nutrition even at a low application rate, and that (2) the application of BIO and BC affects labile as well as stable soil P fractions, which can be better described by sequential fractionation of P pools than by standard soil P tests.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Site Description and Long-Term Experiment

The long-term field trial was commenced in a collaboration between Jimma University (Ethiopia) and Cornell University (USA) on the Eladalle research site of Jimma University in 2012. The field experiment is located at an altitude of 1814 m.a.s.l and at latitude 7°42′05″ N and longitude 36°48′40″ E. The climate is humid subtropical with annual rainfall ranging from 1450 to 1800 mm. Temperature is fairly constant throughout the year, with the maximum temperature ranging from 24 to 29 °C, while the minimum temperature is 9–14 °C. The experimental site soil type is Nitisols with soil texture 50% clay, 48% silt, and 2% sand [23]. The long-term field experiment contains 12 different soil amendments to evaluate the P fertilizer value of bone char- and biochar-based soil amendments in a low-input cropping system, but only nine treatments were selected for this study. A detailed description of the treatments is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Description of soil fertilizer management applied in the long-term field experiment.

Biochar was produced from coffee husks at a temperature of 500 °C with a residence time of 3 h and passed through a sieve before land application. Bone char was produced from animal bones at a temperature of 500 °C with a 3 h residence time. Both chars, the BIO and BC, were produced through pyrolysis, a thermal decomposition process in which biomass is heated in an oxygen-limited or oxygen-depleted environment, which is essential to prevent the biomass from burning and instead allows it to undergo chemical transformation into a stable, carbon-rich solid. Before bone char production, the bones were oven-dried at 70 °C for 72 h. Coffee husks, cow manure, and poultry manure, which are locally available agricultural wastes, were mixed in a 1:1:1 ratio (on a dry weight basis) to produce compost. During compost preparation, water was sprayed regularly to adjust the moisture content of the mixture to 50–60%. The compost pile was rotated once a week during the composting period of 90 days. For the compost mixtures, the pre-prepared compost made from coffee husk, cow manure, and poultry manure was co-composted with BIO and BC. The site was under maize (Zea mays L.) cultivation continuously for the last 10 years. Biochar, bone char, and their mixture with organic and inorganic fertilizers have been applied every year since 2012 in a 4 m × 5 m plot size. The treatments were arranged in a randomized complete block design with three replicates (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of soil, bone char, and biochar soil amendments.

2.2. Soil Sampling and Analysis

The treatments were applied on the surface and mechanically mixed into a depth of 10 cm. Plowing was undertaken with a hand hoe to avoid the mixing of plot soils during land preparation. Considering land preparation and treatment application depth, soil samples were collected from 0 to 10 cm soil depth. Samples were a composite of five random cores per plot and thoroughly mixed to provide a representative soil sample. Samples were collected well within the interior of each plot to avoid borders where fertilizer movement, runoff, or root intrusion from adjacent treatments may occur. The biochar and bone char treatment plots also have a buffer zone of 0.5 m wide for smooth field operation and to avoid mixing of soil during land preparation. Samples were collected after the maize harvest. The composite soil samples were air-dried and sieved through a 2 mm mesh before analysis. To determine the effects of BIO and BC soil amendments on the P pools of different solubility and availability to plants, we conducted a sequential P fractionation using the procedure originally proposed by [26] with modifications, as described by [36]. A series of four sequential extractions was carried out using aqueous solutions of increasing strength.

To determine the mobile and readily available P fraction, 0.5 g of dry soil (<2 mm) was shaken with an end-over-end horizontal shaker with 30 mL of deionized water in a 50 mL centrifuge tube for 18 h. After centrifugation for 18 h, the soil suspension was centrifuged at 3500 rpm for 20 min and the supernatant was filtered and collected for measurement. Then, the labile inorganic and organic fractions weakly adsorbed to mineral surfaces, and some microbial P was extracted by 30 mL of 0.5 M NaHCO3 after 18 h of end-over-end shaking and centrifugation at 3500 rpm for 20 min. The supernatant was filtered (Whatman no. 42 filter) and collected for measurements.

The inorganic P adsorbed and bound to Al- and Fe oxide minerals and organic P from humic substances were extracted using 30 mL of 0.1 M NaOH solution and repeating the second step as described above. The relatively insoluble/occluded fraction of P bound to Al and Fe oxide minerals and apatite was extracted by 30 mL of 1 M H2SO4 in the same way as in the previous steps. The inorganic P (Pi) concentration in the extracts was determined colorimetrically using the molybdate blue method using a UV-Spectrometer (Vario EL, Elementar Analysensysteme, Hanau, Germany). Total P (Pt) in the extracts was measured using an inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES). Concentration of organic P (Po) in the extracts was calculated by subtracting Pi from Pt concentration in the extracts.

Interpretation of the P fraction is based on understanding the mechanism of action of each extractant, their order, and their relationship to soil chemical and biological properties [36]. Ref. [36] considered that bicarbonate extracts the Pi fraction, which is likely to be plant-available. Because bicarbonate introduced minor chemical changes, it is somewhat representative of root action (respiration). Labile-Po is easily mineralized and contributes to plant-available P.

The total P in the soil was analyzed from 0.5 g of a fine-ground soil sample transferred to the Teflon vessels. In brief, the dry fine-ground soil was dissolved with 8 mL of Aqua regia (6 mL of conc. HCl plus 2 mL conc. HNO3) overnight and digested for 20 min at 180 °C in a microwave-digestion system (Mars 6, CEM, Kamp-Lintfort, Germany). Then, samples were left to cool under the hood for 30 min, filtered from the volumetric flask into the respective Erlenmeyer flask, and filled up to 50 mL for measurement. Finally, the measurement of total soil P was conducted by inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectrometry. SOC and total nitrogen (Nt) were determined by the Walkley and Black and Kjeldahl methods, respectively, and available P using the Bray II extraction solution.

2.3. Phosphorus Sorption

Oxalate-extractable Fe (Feox), Al (Alox), (Mnox), and P (Pox) were determined after extraction with oxalate solution using a method modified from [41]. Briefly, 1.5 g of 2 mm sieved dry soil was extracted with 30 mL of oxalate buffer and shaken for 2 h using an overhead shaker in the dark at 35 rpm. After filtration (cellulose round filter, 3–5 m), 1 mL of filtrate was transferred into a 15 mL centrifuge tube and mixed with 11 mL of deionized water for dilution. P-ox, Fe-ox, and Al-ox in the diluted solution were determined by inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES). Phosphorus sorption capacity (PSC) and degree of phosphorus saturation (DPS) were calculated according to Equations (1) and (2) as proposed by [42].

where Alox, Feox, and Mnox are oxalate-extractable Al, Fe, and Mn expressed in mmol kg−1, PSC is PSC (mmol/kg), and α is the applied scaling factor of 0.56. The DPS was calculated by

where Pox is oxalate-extractable P (mmol/kg) and PSC is (mmol/kg)

2.4. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS (version 22.0). Normal distribution of residuals and homogeneity of variance were checked for all analyses using the function Shapiro test and Levene test. The normality of residuals was assessed by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov normality test [43], and it was shown that our data were normally distributed. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to determine the effect of the fertilizer treatments on P fractions, total P, Bray-P, and oxalate-soluble P-ox, Al-ox, Fe-ox, and Mn-ox. The mean values were analyzed for significant differences by using the Tukey multiple-comparison test.

3. Results

3.1. Plant-Available Phosphorus

The long-term application of BIO and BC tended to increase Bray-extraction P as compared to the control and mineral fertilizer treatments (Table 3). In tendency, BC affected Bray-P more than the other treatments, but due to variation, it was not statistically significant as compared to the control and mineral P fertilizer. Bray-extraction P in BC amended soils tended to be higher than with BIO (lignocellulose biochar) application. Overall, the result revealed that with continuous application of BIO and BC, the soil amendments showed a tendency for higher plant-available P compared to the control. Neither the BC nor the BIO treatments affected soil pH compared to the control and mineral fertilizer. Similarly, neither BIO nor BC had any effect on SOC or Nt.

Table 3.

Characteristics of soil samples taken in April 2022. The amendments have been applied since 2012.

3.2. Phosphorus Sorption and Degree of Phosphorus Saturation

The P-ox contents ranged between 143.4 in the control and 277.3 mg kg −1 in the BC treatment. Although the magnitude of differences was not statistically significant between the treatments, P-ox contents tended to be higher under the BIO/BC-char-based soil amendments as compared to the control and mineral fertilizer treatments (Table 4). The Al-ox, Fe-ox, and Mn-ox contents were very similar between the treatments, and hence, no significant differences were observed between the treatments and the control. Similarly, although the PSC values tended to be lowest in the BC treatments (136 mmol kg−1 soil), they were not significantly different compared to the control (Table 4). The degree of soil phosphorus saturation (DPS) did not vary between the treatments. Nevertheless, the BIO and BC soil amendments tended to increase the DPS values.

Table 4.

Oxalate-soluble contents of aluminum, iron, manganese, and phosphorus (Al-ox, Fe-ox, Mn-ox, and P-ox), P-sorption capacity (PSC), and degree of P saturation (DPS) of the soil samples taken in April 2022 after continuous treatment application since 2012.

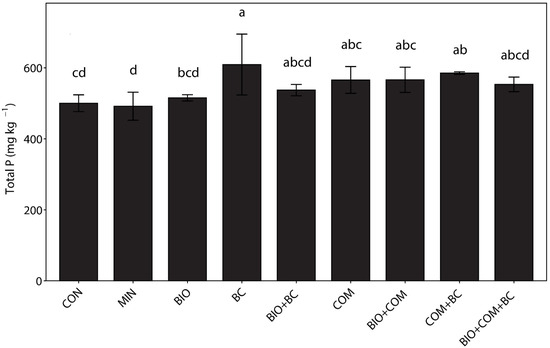

3.3. Total Soil Phosphorus

The result showed that BIO and BC increased the Ptot content as compared to the control and mineral fertilizer treatment (Figure 1). However, only bone char exhibited a significant increase (p < 0.05) in Ptot content. However, other biobased treatments also tended to raise the Ptot content. The highest total soil P content (617 mg P kg−1 soil) was observed under the bone char treatment, whereas the lowest value (531 mg P kg−1) was recorded under the control (p = 0.018). Bone char containing soil amendments showed a higher Ptot (i.e., 18% higher) content compared to coffee husk biochar soil amendments.

Figure 1.

The effect of continuous application of BIO and BC soil amendments on the total soil phosphorus content (means ± SEM). Different letters denote significant differences at p < 0.05; error bars indicate standard error of the mean (n = 3); CON = Control, MIN = Mineral fertilizer, BIO = Biochar, BC = Bone char, BIO + BC = Biochar + bone char, COM = Compost, COM + BC = Compost + bone char, and BIO + COM + BC = Biochar + compost + bone char.

3.4. Labile, Moderately Labile, and Stable Phosphorus Pools

The effect of long-term application of BIO and BC soil amendments on the different P fractionations was analyzed (Table 5). Higher labile P fraction (i.e., the sum of H2O–P and NaHCO3–P) was recorded under the BC treatment (105.9 mg P kg −1), while both pools tended to be lowest in the control (52.2 mg P kg −1). The labile P in the mineral fertilizer treatment tended to be lower than the biobased amendments (57.2 P kg −1). The labile P proportion (H2O–Pi + H2O–Po + NaHCO3–Pi + NaHCO3–Po) represented about 9.5% of the P pools. Within the labile pool, Po was consistently lower than Pi, regardless of the type of biochar feedstock.

Table 5.

The distribution of inorganic P (Pi) and organic P (Po) concentrations of sequentially extracted P fractions of the soil samples taken in April 2022 after continuous treatment application since 2012.

Similar to the labile P pools, there were no significant differences among the treatments in the stable P pools (Table 5). However, certain trends were also apparent here. BC and COM treatments tended to have higher content of the moderately labile P fraction than the other treatments. The present study showed that the effects of BIO- and BC-based fertilizer management tended to decline on stable P pools compared to labile and moderately labile P fractions.

Irrespective of the treatment types, NaOH extracted the majority of fractionated P (i.e., 59.29 to 76.82% of P), followed by the stable P fraction (19.53 to 30.10%) and labile P fractions H2O–P + NaHO3–P (ranging from 6.85 to 14.34%). Comparatively, the NaOH–P fraction tended to be higher under the bone char treatment. Although differences among treatments in the H2SO4–extractable P fraction were not statistically significant, the BC treatment exhibited the highest concentration (185.58 mg P kg−1), whereas BIO showed the lowest (135.4 mg P kg−1). The stable P fraction accounts for the second largest P proportion (ranges from 19.53 to 30.10%) next to the NaOH–P fraction. In the non-labile P fraction, the difference between Pi and Po is marginal, as compared to in the NaOH P fraction, where Po is 3.5 times higher than Pi.

3.5. Organic Phosphorus Fractions

Table 5 presents the distribution of organic phosphorus (Po) in soils amended with BIO- and BC-based fertilizer management and in the control treatment. The concentration of Po was not significantly influenced by either inorganic or organic P fertilizers. However, bone char and compost, when applied individually or in combination with other amendments, exhibited a consistent trend toward higher Po fractions relative to the control and mineral fertilizers. Across all P fractions, the proportion of Po exceeded that of Pi, except for the H2O–P fraction. On average, Po accounted for 71% of total P fractions, with values ranging from 61% to 77%. Comparable to Pi, the majority of Po was extracted by NaOH, followed by H2SO4–Po (19.41%), NaHCO3–Po (8.11%), and H2O–Po (1.55%). The Pi to Po ratio was not affected by fertilizer type (organic vs. inorganic). Notably, across all treatments and irrespective of feedstock P content or fertilizer type, NaOH-extractable Po consistently represented approximately 50% of the total fractionated P.

3.6. Maize Grain Yield

The maize yield varied depending on fertilizer management (Table 6). Across all years, maize grain yield was lowest in the control. Reflecting soil P availability, on average BC application produced higher yields than BIO application (6.4 t ha−1 vs. 5.9 t ha−1). Combining BC with compost further boosted yields compared to applying either amendment alone. Mineral P fertilizer resulted in lower yields than the BIO and BC treatments. From 2020 to 2023, maize yield increased under BIO and BC management but declined in the control (e.g., from 3.9 to 2.2 t ha−1). Overall, fertilizer treatments had a stronger effect on maize yield than on soil P pools, and the combined application of BC and COM seems to be the best option.

Table 6.

The effect of continuous application of BIO and BC soil fertilizer management amendments since 2012 on maize grain yield for the years 2020 to 2023.

4. Discussions

4.1. Standard Soil P Tests

Although the fertilizer treatments affected the total P content in the soil, they did not contribute to a significant increase in bioavailable soil P. However, there was a general tendency for the more readily available P concentrations to increase following the application of the soil amendments. With lower variability in the measurements, significant increases—particularly for the BC treatment—would likely have been observed. One also has to consider that the application rate was only 60% of the recommended rate (which mimics the low-input subsistence farming system). Meta-analysis reported that a higher biochar application rate of above 10 Mg ha−1 can significantly increase the P availability of agricultural soils [8]. However, such a high application rate of BIO and BC fertilizers is a challenge for smallholder farmers, where biomass, including crop residue, has competing uses such as livestock feed, energy, and income sources [4]. Another reasonable explanation is the considerably high amounts of amorphous Al and Fe and very low DPS (i.e., ranging from 4 to 6.6%), which possibly lead to P fixation. Furthermore, downward movement of applied P physically during land preparation, and biologically with plant roots below our sampling depth of only 10 cm, could also be an explanation for missing significant effects. Maize root depth on highly weathered deep tropical soil ranges from 1.5 to 1.8 m and thus may shift P from the top to the deeper layer. In agreement with our explanation, it was reported that the translocation of fertilizer P by plant roots or root material below P fertilizer application depth was a factor responsible for gaps in P budgets [44].

Biochar application can influence soil P content through multiple direct and indirect mechanisms, which may differ between the short and long term. In the short term, when applied, biochar can directly release P to the soil [45]. The long-term effects of biochar involve multiple mechanisms and are strongly shaped by soil properties, particularly pH and its influence on the soil’s physicochemical and biological characteristics. For example, a decade-long field study showed that applying a woody biochar with low initial P content to a Ferralsol led to a sustained increase in soil P availability [46]. This increase in available P is likely attributable to biochar’s ability to modulate the transformation of soil P fractions through a network of biological and physicochemical processes, rather than the direct release of P from low-P feedstock. For example, previous studies have shown that biochar amendments can significantly enhance phosphatase activity, which mobilizes soil P [47], and that the diversity and abundance of P-solubilizing bacteria are key drivers of increased plant-available P following biochar application [48].

4.2. Phosphorus Sorption Capacity and Degree of Soil Phosphorus Saturation

The marginal differences in DPS between the fertilizer treatments and the control can also be attributed to the low application rate, as well as the high P adsorption capacity of such a highly weathered tropical soil. The P-ox contents on soil followed the trends of plant-available P and labile P, with a tendency for higher values in BIO and BC fertilizer management compared to the control and mineral fertilizers. Relatively high amounts of oxalate-soluble Al-ox, Fe-ox, and Mn-ox contents reflect the properties of highly weathered tropical soils and contribute to their strong P-sorption capacity. On the other hand, high P-sorption capacity can help prevent P losses through leaching. Critical DPS values are typically defined within the range of 20–45% [49]. The PSC values, averaging around 140 mmol kg−1, fall at the higher end of the range reported for highly weathered tropical soils [50].

4.3. Total Phosphorus

The total phosphorus (Ptot) as affected by P fertilizer management and soil weathering represents the long-term potential of the soil P supply and is an indicator of the soil development stage [51,52,53]. In our study, BIO application showed a weaker effect on Ptot as compared to its counterpart, BC. The higher amounts of soil Ptot with applications of BC support the recent conclusion that biochar produced from high P content feedstock is a promising P recycling fertilizer [54]. In this field experiment, Ptot was relatively high, with an overall average of 580 mg P kg−1 soil—greater than the total P reported for highly weathered tropical soils [55], but comparable to values observed in Nitisols from the region [56]. Highly weathered tropical soils typically contain low total P because most primary P minerals have long been depleted.

While plant-available P is influenced by many factors—such as soil properties (particularly soil pH) and a network of biological and physicochemical processes—total P is determined mainly by the stage of soil weathering and by fertilizer inputs, regardless of whether these inputs are organic or inorganic. A decade-long experiment involving the application of a woody biochar with low initial P content reported a sustained increase in available P but no significant differences in total P among treatments [45], reflecting the lower dependency of total P on soil physiochemical properties and biochemical processes. Therefore, the increase in total P observed in our study under bone char treatment, compared with the control and the low-P coffee husk biochar, clearly demonstrates the phosphorus accumulation effect of bone char application due to its higher P content.

4.4. Labile and Stable Phosphorus Pools

The Hedley P fractions were not significantly affected by the amendments, but they tended to show higher values following the application of BC. Previous studies have shown that biochar application can increase labile P through a liming effect [8,23] and release P from the biochar itself [20]. However, neither pH was affected by the treatment application which could be explained by the relatively low application rate. Overall, the results for available P after biochar application are inconsistent, being similar [30], higher [23,42,57,58], or lower [31] than that in the control soil. Such inconsistent results could be due to differences in biochar properties, including feedstock’s P contents, pyrolysis temperature and soil properties like pH, and the status of soil available P and organic carbon [31,59]. Although biochar is persistent in the soil system, its effects on P are different over the short term and long term. Generally, studies showed that the marked or substantial increase in available P in incubation and short-term studies is not reported under field conditions [30,60]. Therefore, the modest effects of the present study on labile P are reasonably acceptable. Although plant-available P (Bray-test) and the labile soil P fractions followed the same pattern, labile P was on average about thirty times higher than the Bray-P values, suggesting the importance of considering this in terms of practical fertilizer management. Several studies were conducted in tropical agroecosystems to understand the impact of long-term management systems on P fractions. Findings showed that continuous cultivation of different tropical soils with little input of P drastically decreased the concentration of all P fractions as compared with their respective uncultivated soils [25], and that relatively high amounts of P up to 90 kg per ha and year are necessary to maintain the status quo [61]. In this study, the modest effects of BIO and BC on labile P are expected, likely due to the low amendment rates and strong P fixation in the highly weathered Nitisols.

Moderately labile P (NaOH–P) and stable P (H2SO4–P) were not affected by the fertilizer treatments. The low sensitivity of NaOH–P and P–H2SO4–P following low and moderate rates of P application to agricultural soils was previously also reported [62]. The order of sequentially extracted P fractions (i.e., H2O–Po < H2O–Pi < NaHCO3–Po < NaHCO3–Pi < H2SO4–Pi < H2SO4–Po < NaOH–Pi < NaOH–Po) is in accordance with other findings [57,58,63], reflecting the general status of P pools on highly weathered tropical soils. The high proportion of non-labile P fractions in highly weathered tropical soils is driven by their abundant sesquioxides and low-activity clay minerals, which strongly sequester P [64].

NaOH-extractable P represented the largest P fraction, likely due to the strong extraction capacity of NaOH and the soil’s high Al, Fe, and clay contents. In highly weathered soils, this fraction also serves as an important buffer for labile inorganic P [65]. Therefore, long-term fertilization strategies for highly weathered, P-fixing tropical soils should place greater emphasis on the moderately labile P fraction; when plants deplete the labile P pool, the moderately labile pool helps replenish it.

4.5. Organic Phosphorus Is Independent of Fertilizer Type

Results from sequential fractionation revealed that organic phosphorus (Po) was independent of fertilizer type (organic or inorganic). If Po had been strongly influenced by fertilizer type, the proportion of Po in the control and mineral fertilizer treatments would be expected to be lower compared with the biobased soil amendments. However, the formation and stabilization of organic P compounds which arise in soils not only form organic matter supply but are complex turnover processes regulated also by plants, microorganisms, abiotic factors, and soil management practices [55,66]. Consistent with our findings, ref. [67] also reported that organic P forms remained largely unchanged in soils with contrasting fertilizer histories, including mineral fertilizers and various organic amendments.

Organic P represents the largest proportion of total soil P in our study (especially in the NaOH–P fraction), accounting for approximately 70% on average. Soil organic P is strongly influenced by the degree of soil development (weathering) and by intrinsic soil properties, particularly texture and organic C content. In this study, the high proportion of Po is most likely attributable to the advanced stage of soil weathering and the soil’s physical characteristics.

During early soil development, the weathering of primary minerals releases P in various forms. The soluble P released can either be taken up by biota—entering the organic P pool—or adsorbed onto secondary mineral surfaces. As soils progress through later stages of development, organic P tends to dominate the total soil P pool [36]. Furthermore, the high clay content of the studied soil (50% clay and 48% silt) likely contributes to the elevated Po levels. Clay particles physically protect Po from mineralization [57,58], thereby enhancing its stability and reducing enzymatic hydrolysis [68]. Consistent with our findings, highly weathered tropical soils often contain a high proportion of Po [69].

With H2O extraction, however, the Po fraction was lower than its inorganic counterpart (Pi), and also in the NaHCO3–P fraction, the Po content was not clearly higher than Pi. Studies reported that the labile Po fraction does not accumulate because of its rapid turnover, serving instead as a major P source for plants, particularly in highly weathered tropical and subtropical soils [70]. However, the labile fractions accounted for only a relatively small proportion of the total soil P content. In highly weathered soils such as Ultisols, up to 80% of the variation in labile P is attributed to organic forms, indicating that Po mineralization can be a key determinant of P fertility [36]. A similar study described that soil organic P contributes significantly to the nutrition of tropical trees, yet is often overlooked in standard soil P tests [71].

4.6. Biochar- and Bone Char-Based Fertilizer Management Enhanced Maize Yield

The priority of soil fertilizer management in agricultural fields is usually the agronomic yield. The present study demonstrated that BIO and BC soil amendments consistently enhanced the grain yield of maize compared with control and mineral fertilizer treatments across the four years evaluated. Positive yield responses to BIO and BC fertilizer applications have also been reported in previous studies [29,54]. However, the magnitude and direction of these effects vary across studies, largely depending on environmental factors such as soil properties, biochar feedstock type, biochar production conditions, and application rates. The enhanced maize grain yield following BIO and BC applications highlights the potential of these materials to improve plant nutrition in developing countries. Many previous studies applied biochar at a higher rate to maximize its positive effect [8,31], which is not in line with the majority of subsistence farmers in developing countries. Smallholder farmers apply less than the recommended rate of fertilizer due to inaccessibility and unaffordability [4]. We recognize that this effect is not solely attributable to P input, as reflected in the soil P pool results. Improvements in bulk density, water retention, soil structure, and microbial biomass [72,73] likely also contributed to these outcomes. Furthermore, similar to other organic soil amendments, BIO and BC also supplied other plant nutrients [54,74]. In highly weathered tropical soils, deficiencies of cations such as calcium and magnesium are common; the additional supply of these nutrients through biochar- and bone char-based fertilizers likely supported plant growth and contributed to the observed increase in maize grain yield. This observation is consistent with the findings of previous studies, which reported that the positive effects of biochar on crop yields are generally more pronounced in nutrient-poor soils than in fertile ones [24,29].

5. Conclusions

Although long-term amendment applications had only modest effects on soil P pools, a yield response was still observed. While this response cannot be attributed solely to the P content of the amendments, the results suggest that even low biochar application rates can support plant P nutrition. Combined applications of biochar and compost produced the greatest benefits, which should be considered in fertilizer recommendations. The lack of significant treatment effects on soil P concentrations can also be explained by the relatively high variability of the measurements. Therefore, a more intensive sampling approach would likely provide clearer insights. Results from the complementary soil analysis methods suggest that P availability may be higher than expected even under conditions of strongly P-fixing soils. Given the high proportion of organic P in our study, we recommend that this fraction be considered more strongly in fertilizer recommendations, even though it is not always captured by standard soil P tests.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.T., A.N. (Abebe Nigussie) and B.E.-L.; methodology, A.T., A.N. (Abebe Nigussie), B.E.-L., A.N. (Amsalu Nebiyu), G.W. and M.A.; formal analysis, A.T., B.E.-L., A.N. (Amsalu Nebiyu) and A.N. (Abebe Nigussie); investigation, A.T., B.E.-L., A.N. (Abebe Nigussie), A.N. (Amsalu Nebiyu), G.W. and M.A.; data curation, A.T., B.E.-L., A.N. (Abebe Nigussie) and M.A.; writing—original draft preparation, A.T., B.E.-L., G.W. and A.N. (Abebe Nigussie); writing—review and editing, B.E.-L., A.T., A.N. (Amsalu Nebiyu), G.W., A.N. (Abebe Nigussie) and M.A.; visualization, A.N. (Abebe Nigussie) and G.W.; supervision, B.E.-L., A.N. (Abebe Nigussie), G.W., A.N. (Amsalu Nebiyu) and M.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive external funding. Rostock University covered the article processing charge (APC) through the University Library. Financial support for this study was provided by the KfW Project No. 51235 through the ExiST Project Ethiopia: Excellence in Science and Technology.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the KfW Development Bank, Germany, for its financial support and the Ministry of Education of Ethiopia for its effective coordination of this project. We sincerely thank Marcel Maria Ackermann and Brigitte Claus for their support and guidance during the laboratory soil sample analyses, and Yue Hu for technical assistance during data analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- MacDonald, G.K.; Bennett, E.M.; Potter, P.A.; Ramankutty, N. Agronomic Phosphorus Imbalances across the World’s Croplands. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 3086–3091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Vuuren, D.P.; Bouwman, A.F.; Beusen, A.H.W. Phosphorus Demand for the 1970–2100 Period: A Scenario Analysis of Resource Depletion. Glob. Environ. Change 2010, 20, 428–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adjognon, S.G.; Liverpool-Tasie, L.S.O.; Reardon, T.A. Agricultural Input Credit in Sub-Saharan Africa: Telling Myth from Facts. Food Policy 2017, 67, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nigussie, A.; Kuyper, T.W.; Neergaard, A.D. Agricultural Waste Utilisation Strategies and Demand for Urban Waste Compost: Evidence from Smallholder Farmers in Ethiopia. Waste Manag. 2015, 44, 82–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, K.; Qiu, M.; Han, L.; Jin, J.; Wang, Z.; Pan, Z.; Xing, B. Speciation of Phosphorus in Plant- and Manure-Derived Biochars and Its Dissolution under Various Aqueous Conditions. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 634, 1300–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solangi, F.; Zhu, X.; Khan, S.; Rais, N.; Majeed, A.; Sabir, M.A.; Iqbal, R.; Ali, S.; Hafeez, A.; Ali, B.; et al. The Global Dilemma of Soil Legacy Phosphorus and Its Improvement Strategies under Recent Changes in Agro-Ecosystem Sustainability. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 23271–23282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruun, S.; Harmer, S.L.; Bekiaris, G.; Christel, W.; Zuin, L.; Hu, Y.; Jensen, L.S.; Lombi, E. The Effect of Different Pyrolysis Temperatures on the Speciation and Availability in Soil of P in Biochar Produced from the Solid Fraction of Manure. Chemosphere 2017, 169, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, B.; Lehr, V.-I. Biochar Effects on Phosphorus Availability in Agricultural Soils: A Meta-Analysis. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 9338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Luo, J.; Zhang, Q.; Aleem, M.; Fang, F.; Xue, Z.; Cao, J. Potentials and Challenges of Phosphorus Recovery as Vivianite from Wastewater: A Review. Chemosphere 2019, 226, 246–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Pratt, S.; Batstone, D.J. Phosphorus Recovery from Wastewater through Microbial Processes. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2012, 23, 878–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, J.; Rillig, M.C.; Thies, J.; Masiello, C.A.; Hockaday, W.C.; Crowley, D. Biochar Effects on Soil Biota—A Review. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2011, 43, 1812–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Feng, X.; Song, W.; Guo, M. Transformation of Phosphorus in Speciation and Bioavailability During Converting Poultry Litter to Biochar. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2018, 2, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manolikaki, I.I.; Mangolis, A.; Diamadopoulos, E. The Impact of Biochars Prepared from Agricultural Residues on Phosphorus Release and Availability in Two Fertile Soils. J. Environ. Manag. 2016, 181, 536–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glæsner, N.; Hansen, H.C.B.; Hu, Y.; Bekiaris, G.; Bruun, S. Low Crystalline Apatite in Bone Char Produced at Low Temperature Ameliorates Phosphorus-Deficient Soils. Chemosphere 2019, 223, 723–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwetsloot, M.J.; Lehmann, J.; Bauerle, T.; Vanek, S.; Hestrin, R.; Nigussie, A. Phosphorus Availability from Bone Char in a P-Fixing Soil Influenced by Root-Mycorrhizae-Biochar Interactions. Plant Soil 2016, 408, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, J.; Cowie, A.; Masiello, C.A.; Kammann, C.; Woolf, D.; Amonette, J.E.; Cayuela, M.L.; Camps-Arbestain, M.; Whitman, T. Biochar in Climate Change Mitigation. Nat. Geosci. 2021, 14, 883–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, B.; Peng, Y.; Lin, L.; Zhang, D.; Ma, L.; Jiang, L.; Li, Y.; He, T.; Wang, Z. Drivers of Biochar-Mediated Improvement of Soil Water Retention Capacity Based on Soil Texture: A Meta-Analysis. Geoderma 2023, 437, 116591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Xiao, J.; Xue, J.; Zhang, L. Quantifying the Effects of Biochar Application on Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Agricultural Soils: A Global Meta-Analysis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Li, C.; Li, G.; Lin, Q.; Zhao, X.; He, Y.; Liu, Y.; Luo, Z. Biochar Alters Inorganic Phosphorus Fractions in Tobacco-Growing Soil. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2021, 21, 1689–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; DeLuca, T.H.; Cleveland, C.C. Biochar Additions Alter Phosphorus and Nitrogen Availability in Agricultural Ecosystems: A Meta-Analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 654, 463–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Sun, J.; Shao, H.; Chang, S.X. Biochar Had Effects on Phosphorus Sorption and Desorption in Three Soils with Differing Acidity. Ecol. Eng. 2014, 62, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngaba, M.J.Y.; Yemele, O.M.; Hu, B.; Rennenberg, H. Biochar Application as a Green Clean-up Method: Bibliometric Analysis of Current Trends and Future Perspectives. Biochar 2025, 7, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melaku, T.; Ambaw, G.; Nigussie, A.; Woldekirstos, A.N.; Bekele, E.; Ahmed, M. Short-Term Application of Biochar Increases the Amount of Fertilizer Required to Obtain Potential Yield and Reduces Marginal Agronomic Efficiency in High Phosphorus-Fixing Soils. Biochar 2020, 2, 503–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffery, S.; Abalos, D.; Prodana, M.; Bastos, A.C.; Van Groenigen, J.W.; Hungate, B.A.; Verheijen, F. Biochar Boosts Tropical but Not Temperate Crop Yields. Environ. Res. Lett. 2017, 12, 053001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negassa, W.; Leinweber, P. How Does the Hedley Sequential Phosphorus Fractionation Reflect Impacts of Land Use and Management on Soil Phosphorus: A Review. Z. Pflanzenernähr. Bodenk. 2009, 172, 305–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedley, M.J.; Stewart, J.W.B.; Chauhan, B.S. Changes in Inorganic and Organic Soil Phosphorus Fractions Induced by Cultivation Practices and by Laboratory Incubations. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1982, 46, 970–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, K.R.; Kadlec, R.H.; Flaig, E.; Gale, P.M. Phosphorus Retention in Streams and Wetlands: A Review. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1999, 29, 83–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syers, J.K.; Johnston, A.E.; Curtin, D. Efficiency of Soil and Fertilizer Phosphorus Use: Reconciling Changing Concepts of Soil Phosphorus Behaviour with Agronomic Information; FAO Fertilizer and Plant Nutrition Bulletin; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2008; ISBN 978-92-5-105929-6. [Google Scholar]

- Mekonnen, B.; Wilske, B.; Addisu, B.; Nigussie, A.; Siegfried, K.; Gizachew, S.; Yimer, T.; Mohammed, B.; Ahmed, M.; Abera, T.; et al. Biochar-based Fertilizers Increase Crop Yields in Acidic Tropical Soils. Biofuels Bioprod. Bioref. 2025, 19, 1124–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Chen, H.; Chen, G.; Wang, S. Seven Years of Biochar Amendment Has a Negligible Effect on Soil Available P and a Progressive Effect on Organic C in Paddy Soils. Biochar 2022, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornø, M.L.; Müller-Stöver, D.S.; Liu, F. Contrasting Effects of Biochar on Phosphorus Dynamics and Bioavailability in Different Soil Types. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 627, 963–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul, S.; Whalen, J.K.; Thomas, B.W.; Sachdeva, V.; Deng, H. Physico-Chemical Properties and Microbial Responses in Biochar-Amended Soils: Mechanisms and Future Directions. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2015, 206, 46–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichler, B.; Caus, M.; Schnug, E.; Köppen, D. Soil Acid and Alkaline Phosphatase Activities in Regulation to Crop Species and Fungal Treatment. Landbauforsch. Volkenrode 2004, 54, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y.; Jarosch, K.A.; Kavka, M.; Eichler-Löbermann, B. Fate of P from Organic and Inorganic Fertilizers Assessed by Complementary Approaches. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 2022, 124, 189–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan-Meille, L.; Rubæk, G.H.; Ehlert, P.A.I.; Genot, V.; Hofman, G.; Goulding, K.; Recknagel, J.; Provolo, G.; Barraclough, P. An Overview of fertilizer-P Recommendations in Europe: Soil Testing, Calibration and Fertilizer Recommendations. Soil Use Manag. 2012, 28, 419–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiessen, H.; Stewart, J.W.B.; Cole, C.V. Pathways of Phosphorus Transformations in Soils of Differing Pedogenesis. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1984, 48, 853–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, P.P.; Liang, B.; Turner-Walker, G.; Rathod, J.; Lee, Y.-C.; Wang, C.-C.; Chang, C.-K. Systematic Changes of Bone Hydroxyapatite along a Charring Temperature Gradient: An Integrative Study with Dissolution Behavior. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 766, 142601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.-H.; Lehmann, J.; Engelhard, M.H. Natural Oxidation of Black Carbon in Soils: Changes in Molecular Form and Surface Charge along a Climosequence. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2008, 72, 1598–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mia, S.; Singh, B.; Dijkstra, F.A. Aged Biochar Affects Gross Nitrogen Mineralization and Recovery: A 15N Study in Two Contrasting Soils. GCB Bioenergy 2017, 9, 1196–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Liang, X.; Niyungeko, C.; Sun, T.; Liu, F.; Arai, Y. Effects of Biochar Amendments on Soil Phosphorus Transformation in Agricultural Soils. In Advances in Agronomy; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; Volume 158, pp. 131–172. ISBN 978-0-12-817412-8.41. [Google Scholar]

- Schwertmann, U. Differenzierung der Eisenoxide des Bodens durch Extraktion mit Ammoniumoxalat-Lösung. Z. Pflanzenernaehr. Dueng. Bodenk. 1964, 105, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Zee, S.E.A.T.M.; Van Riemsdijk, W.H. Model for Long-term Phosphate Reaction Kinetics in Soil. J. Environ. Qual. 1988, 17, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drezner, Z.; Turel, O.; Zerom, D. A Modified Kolmogorov–Smirnov Test for Normality. Commun. Stat.—Simul. Comput. 2010, 39, 693–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauke, S.L.; Landl, M.; Koch, M.; Hofmann, D.; Nagel, K.A.; Siebers, N.; Schnepf, A.; Amelung, W. Macropore Effects on Phosphorus Acquisition by Wheat Roots—A Rhizotron Study. Plant Soil 2017, 416, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Q.; Gao, Y.; Ma, G.; Wu, H.; Li, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, S.; Jie, X.; Zhang, D.; Wang, D. The Long-Term Effect of Biochar Amendment on Soil Biochemistry and Phosphorus Availability of Calcareous Soils. Agriculture 2025, 15, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavich, P.G.; Sinclair, K.; Morris, S.G.; Kimber, S.W.L.; Downie, A.; Van Zwieten, L. Contrasting Effects of Manure and Green Waste Biochars on the Properties of an Acidic Ferralsol and Productivity of a Subtropical Pasture. Plant Soil 2013, 366, 213–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Lu, S. Straw and Straw Biochar Differently Affect Phosphorus Availability, Enzyme Activity and Microbial Functional Genes in an Ultisol. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 805, 150325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Heal, K.; Tigabu, M.; Xia, L.; Hu, H.; Yin, D.; Ma, X. Biochar Addition to Forest Plantation Soil Enhances Phosphorus Availability and Soil Bacterial Community Diversity. For. Ecol. Manag. 2020, 455, 117635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Campos, M.; Antonangelo, J.A.; Van Der Zee, S.E.A.T.M.; Alleoni, L.R.F. Degree of Phosphate Saturation in Highly Weathered Tropical Soils. Agric. Water Manag. 2018, 206, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koopmans, G.F.; Chardon, W.J.; Dekker, P.H.M.; Römkens, P.F.A.M.; Schoumans, O.F. Comparing different extraction methods for estimating phosphorus solubility in various soil types. Soil Sci. 2006, 171, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, D.; Zhang, C.; Li, H.; Lambers, H.; Zhang, F. Changes in Soil Phosphorus Fractions Following Sole Cropped and Intercropped Maize and Faba Bean Grown on Calcareous Soil. Plant Soil 2020, 448, 587–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meena, M.D.; Narjary, B.; Sheoran, P.; Jat, H.S.; Joshi, P.K.; Chinchmalatpure, A.R.; Yadav, G.; Yadav, R.K.; Meena, M.K. Changes of Phosphorus Fractions in Saline Soil Amended with Municipal Solid Waste Compost and Mineral Fertilizers in a Mustard-Pearl Millet Cropping System. Catena 2018, 160, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Boitt, G.; Black, A.; Wakelin, S.; Condron, L.M.; Chen, L. Accumulation and Distribution of Phosphorus in the Soil Profile under Fertilized Grazed Pasture. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2017, 239, 228–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakweya, T.; Nigussie, A.; Worku, G.; Biresaw, A.; Aticho, A.; Hirko, O.; Ambaw, G.; Mamuye, M.; Dume, B.; Ahmed, M. Long-term Effects of Bone Char and Lignocellulosic Biochar-based Soil Amendments on Phosphorus Adsorption–Desorption and Crop Yield in Low-input Acidic Soils. Soil Use Manag. 2022, 38, 703–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Augusto, L.; Goll, D.S.; Ringeval, B.; Wang, Y.; Helfenstein, J.; Huang, Y.; Yu, K.; Wang, Z.; Yang, Y.; et al. Global Patterns and Drivers of Soil Total Phosphorus Concentration. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2021, 13, 5831–5846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilahun, A.; Cornelis, W.; Sleutel, S.; Nigussie, A.; Dume, B.; Van Ranst, E. The Potential of Termite Mound Spreading for Soil Fertility Management under Low Input Subsistence Agriculture. Agriculture 2021, 11, 1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, Y.; Watanabe, Y. Combined Applications of Chemical Fractionation, Solution 31P-NMR and P K-Edge XANES to Determine Phosphorus Speciation in Soils Formed on Serpentine Landscapes. Geoderma 2014, 230–231, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDowell, R.W.; Stewart, I. The Phosphorus Composition of Contrasting Soils in Pastoral, Native and Forest Management in Otago, New Zealand: Sequential Extraction and 31P NMR. Geoderma 2006, 130, 176–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesfaye, F.; Liu, X.; Zheng, J.; Cheng, K.; Bian, R.; Zhang, X.; Li, L.; Drosos, M.; Joseph, S.; Pan, G. Could Biochar Amendment Be a Tool to Improve Soil Availability and Plant Uptake of Phosphorus? A Meta-Analysis of Published Experiments. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res 2021, 28, 34108–34120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joseph, S.; Cowie, A.L.; Van Zwieten, L.; Bolan, N.; Budai, A.; Buss, W.; Cayuela, M.L.; Graber, E.R.; Ippolito, J.A.; Kuzyakov, Y.; et al. How Biochar Works, and When It Doesn’t: A Review of Mechanisms Controlling Soil and Plant Responses to Biochar. GCB Bioenergy 2021, 13, 1731–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, J.E.; Bates, T.E.; Sheppard, S.C. Changes in the Forms and Distribution of Soil Phosphorus Due to Long-Term Corn Production. Can. J. Soil Sci. 1995, 75, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klotzbücher, A.; Kaiser, K.; Klotzbücher, T.; Wolff, M.; Mikutta, R. Testing Mechanisms Underlying the Hedley Sequential Phosphorus Extraction of Soils. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2019, 182, 570–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morshedizad, M.; Panten, K.; Klysubun, W.; Leinweber, P. Bone Char Effects on Soil: Sequential Fractionations and XANES Spectroscopy. Soil 2018, 4, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, T.W.; Syers, J.K. The Fate of Phosphorus during Pedogenesis. Geoderma 1976, 15, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penn, C.; Camberato, J. A Critical Review on Soil Chemical Processes That Control How Soil pH Affects Phosphorus Availability to Plants. Agriculture 2019, 9, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Requejo, M.I.; Eichler-Löbermann, B. Organic and Inorganic Phosphorus Forms in Soil as Affected by Long-Term Application of Organic Amendments. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 2014, 100, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annaheim, K.E.; Rufener, C.B.; Frossard, E.; Bünemann, E.K. Hydrolysis of Organic Phosphorus in Soil Water Suspensions after Addition of Phosphatase Enzymes. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2013, 49, 1203–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mortland, M.M.; Gieseking, J.E. The Influence of Clay Minerals on the Enzymatic Hydrolysis of Organic Phosphorus Compounds. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1952, 16, 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Post, W.M. Phosphorus Transformations as a Function of Pedogenesis: A Synthesis of Soil Phosphorus Data Using Hedley Fractionation Method. Biogeosciences 2011, 8, 2907–2916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, A.G.; Turner, B.L.; Tanner, E.V.J. Soil Organic Phosphorus Dynamics Following Perturbation of Litter Cycling in a Tropical Moist Forest. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2010, 61, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darch, T.; Blackwell, M.S.A.; Chadwick, D.; Haygarth, P.M.; Turner, B.L. Assessment of Bioavailable Organic Phosphorus in Tropical Forest Soils by Organic Acid Extraction and Phosphatase Hydrolysis. Geoderma 2016, 284, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, E.; Kim, K.-H.; Kwon, E.E. Biochar as a Tool for the Improvement of Soil and Environment. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1324533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razzaghi, F.; Obour, P.B.; Arthur, E. Does Biochar Improve Soil Water Retention? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Geoderma 2020, 361, 114055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerssa, G.W.; Kim, D.-G.; Koal, P.; Eichler-Löbermann, B. Combination of Compost and Mineral Fertilizers as an Option for Enhancing Maize (Zea mays L.) Yields and Mitigating Greenhouse Gas Emissions from a Nitisol in Ethiopia. Agronomy 2021, 11, 2097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).