Effects of Different Sod-Seeding Patterns on Soil Properties, Nitrogen Cycle Genes, and N2O Mitigation in Peach Orchards

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site

2.2. Experiment Design

2.3. Measurements

2.3.1. Soil Physiochemical and Enzymic Indicators

2.3.2. Soil N2O Flux and Accumulative Emission

2.3.3. Soil Metagenomic Sequencing

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

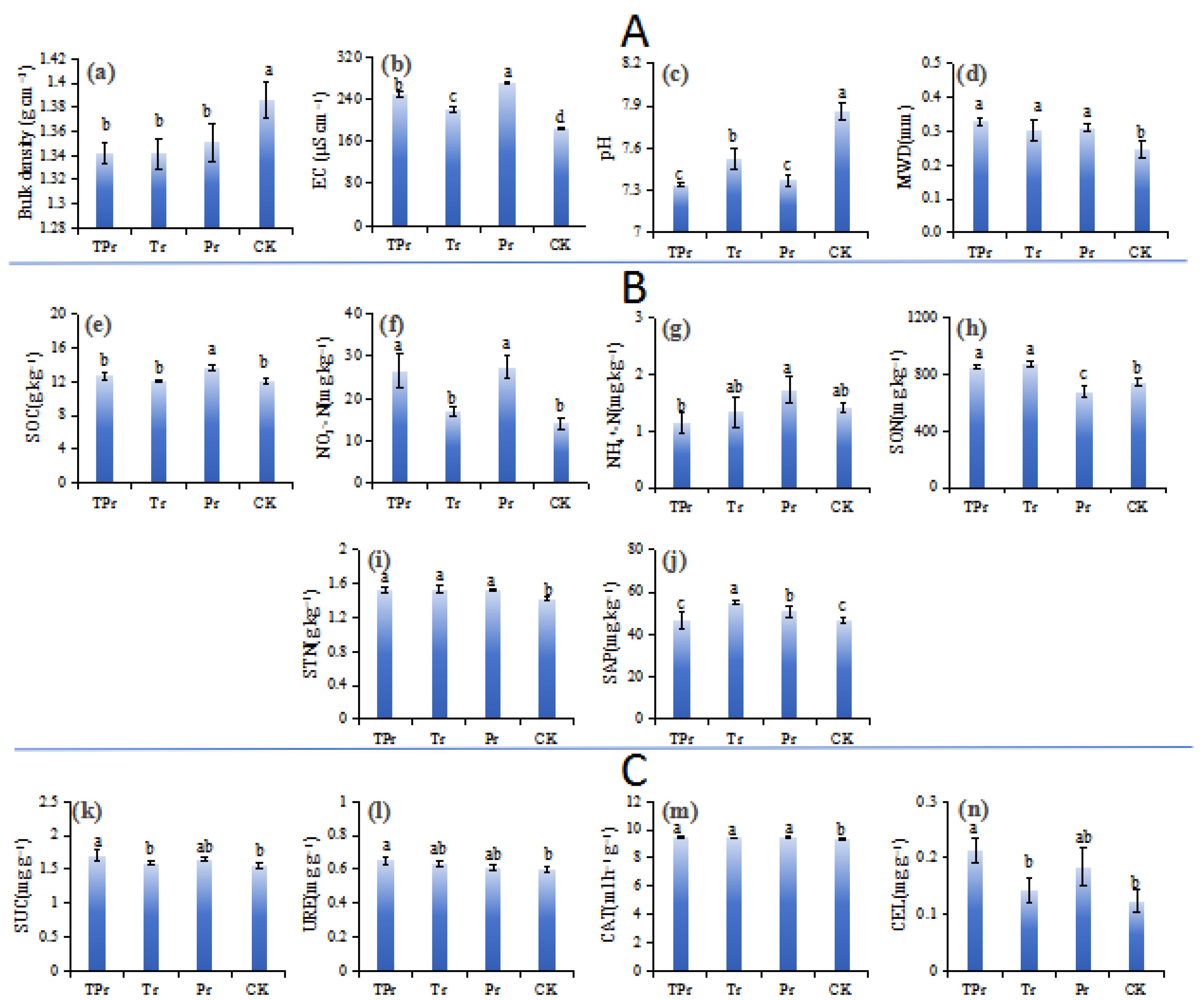

3.1. Effects on Soil Properties

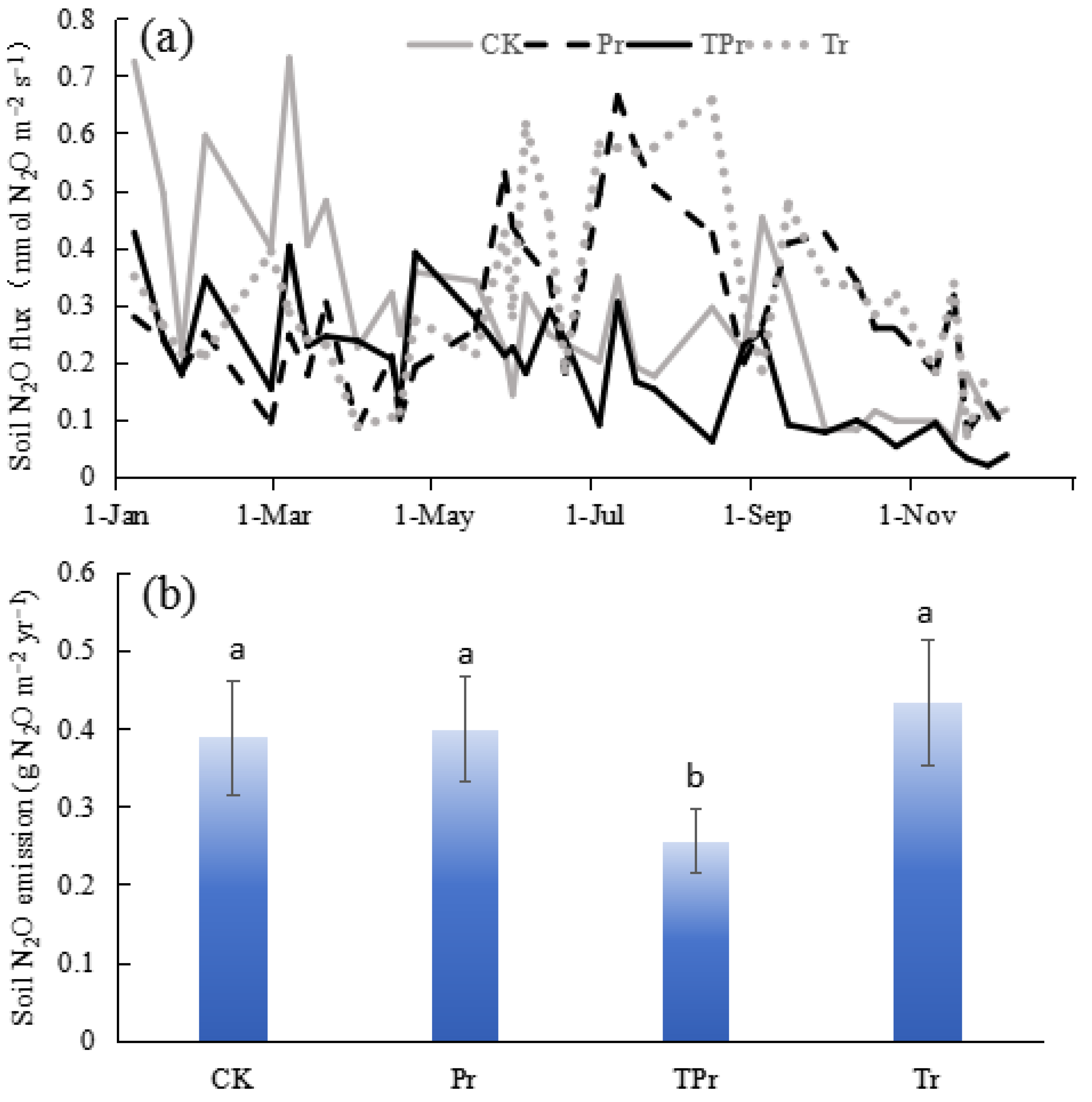

3.2. Effects on N2O Emission

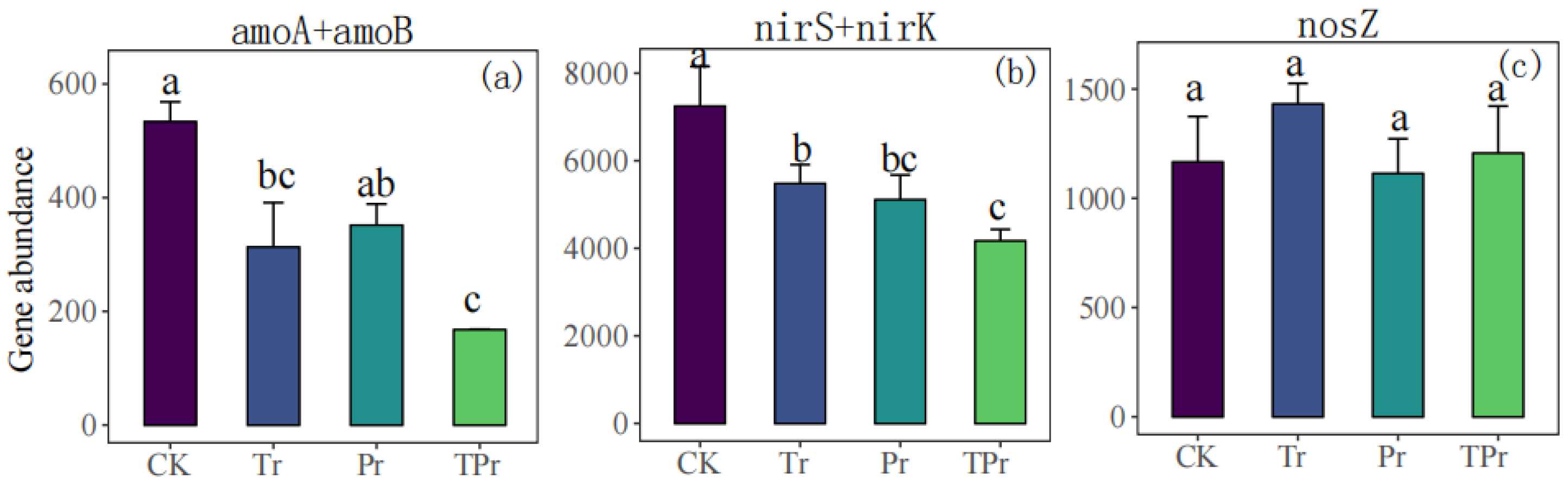

3.3. Effects on Nitrogen Cycle Genes

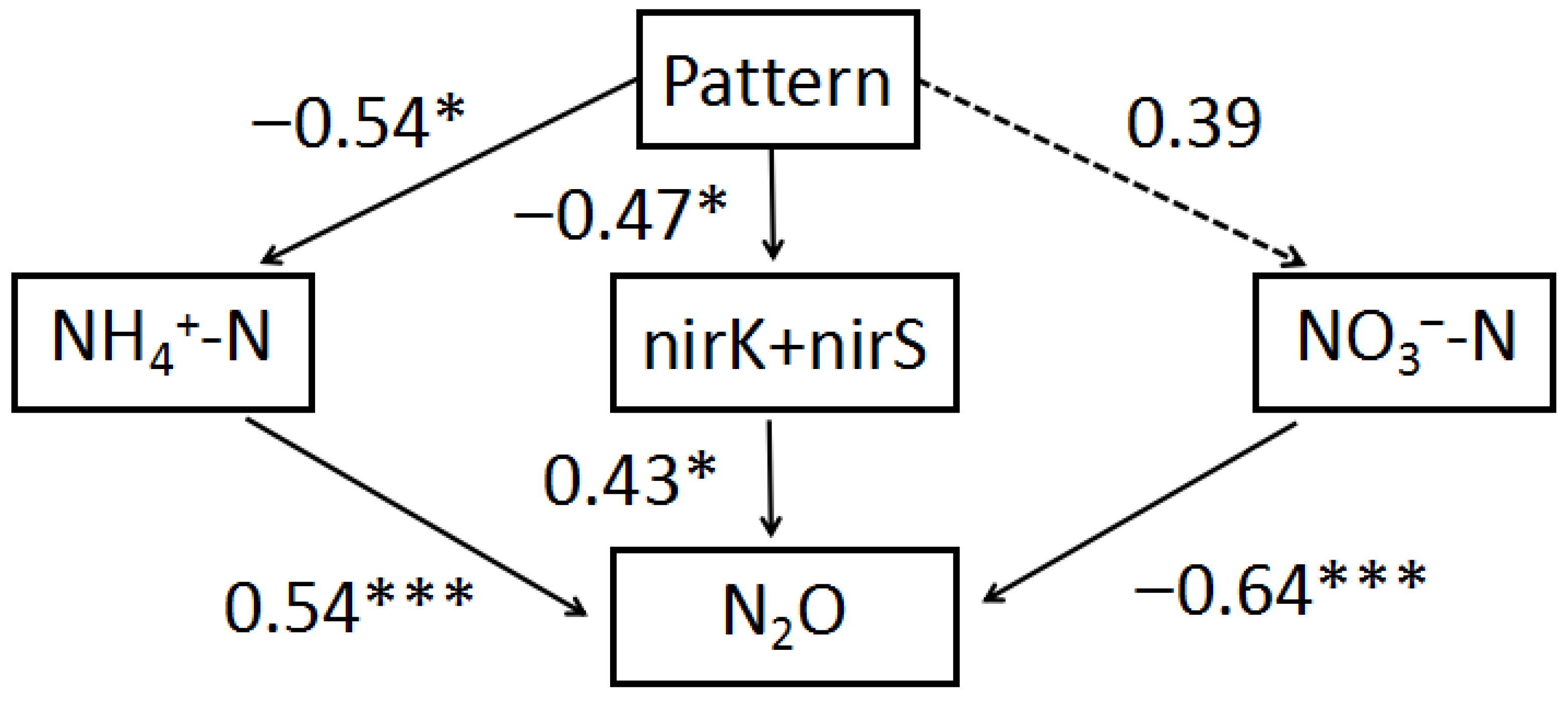

3.4. The Impact of Sod-Seeding Pattern on N2O Emission: Pathways and Correlations

4. Discussion

4.1. Impacts on Soil Quality and Health

4.2. Pathways from Sod-Seeding Pattern to Nitrogen Substrates and Functional Genes

4.3. Direct Effects of Nitrogen Substrates and Functional Genes on N2O

4.4. Integrated Mechanisms and Implications

- (1)

- Substrate-driven pathway: The pattern regulates NH4+-N, which directly fuels N2O production by providing substrates for nitrification and denitrification [51].

- (2)

- Microbial-functional pathway: The pattern controls the abundances of nirK + nirS, changing the denitrification potential and N2O formation [54].

- (3)

- Competitive-denitrification pathway: The pattern has a weak direct effect on NO3−-N but strongly influences N2O through NO3−-mediated completion of denitrification, reducing the intermediate N2O [55].

4.5. Implications, Limitations, and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, Z.; Lin, Y.; Lu, H.; Ding, M.; Tan, Y.; Xu, S.; Fu, S. Maintenance of a living understory enhances soil carbon sequestration in subtropical orchards. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e76950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; Ma, Q.; Chen, H.; Wu, L.; Ye, Y. Mitigating Soil Phosphorus Leaching Risk and Improving Pear Production Through Planting and Mowing Ryegrass Mode. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinbaum, S.; Johnson, R.; DeJong, T. Causes and Consequences of Overfertilization in Orchards. HortTechnology 1992, 2, 112b–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montanaro, G.; Xiloyannis, C.; Nuzzo, V.; Dichio, B. Orchard management, soil organic carbon and ecosystem services in Mediterranean fruit tree crops. Sci. Hortic. 2017, 217, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathore, A.; Singh, C.; Jayaprakash, J.; Gupta, A.; Doharey, V.; Jinger, D.; Singh, D.; Yadav, D.; Barh, A.; Islam, S.; et al. Impact of conservation practices on soil quality and ecosystem services under diverse horticulture land use system. Front. For. Glob. Chang. 2023, 6, 1289325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Ciais, P.; Tzompa-Sosa, Z.; Saunois, M.; Qiu, C.; Tan, C.; Sun, T.; Ke, P.; Cui, Y.; Tanaka, K.; et al. Comparing national greenhouse gas budgets reported in UNFCCC inventories against atmospheric inversions. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2022, 14, 1639–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Wolf, J.; Zhang, F. Towards sustainable intensification of apple production in China—Yield gaps and nutrient use efficiency in apple farming systems. J. Integr. Agric. 2016, 15, 716–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsina, M.; Fanton-Borges, A.; Smart, D. Spatiotemporal variation of event related N2O and CH4 emissions during fertigation in a California almond orchard. Ecosphere 2013, 4, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Li, C.; Burger, M.; Horwáth, W.; Smart, D.; Six, J.; Guo, L.; Salas, W.; Frolking, S. Assessing Short-Term Impacts of Management Practices on N2O Emissions from Diverse Mediterranean Agricultural Ecosystems Using a Biogeochemical Model. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 2018, 123, 1557–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, S.; Frøseth, R.; Stenberg, M.; Stalenga, J.; Olesen, J.; Krauss, M.; Radzikowski, P.; Doltra, J.; Nadeem, S.; Torp, T.; et al. Reviews and syntheses: Review of causes and sources of N2O emissions and NO3 leaching from organic arable crop rotations. Biogeosciences 2019, 16, 2795–2819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberson, A.; Jarosch, K.; Frossard, E.; Hammelehle, A.; Fließbach, A.; Mäder, P.; Mayer, J. Higher than expected: Nitrogen flows, budgets, and use efficiencies over 35 years of organic and conventional cropping. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2023, 362, 108802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.; Xiao, S.; Liao, Y.; Huang, J.; Li, H. Effects of Rainfall Variability and Land Cover Type on Soil Organic Carbon Loss in a Hilly Red Soil Region of Southern China. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Gao, B.; Hu, X.K.; Lu, X.; Well, R.; Christie, P.; Bakken, L.R.; Ju, X.T. Ammonia-oxidation as an engine to generate nitrous oxide in an intensively managed calcareous fluvo-aquic soil. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 3950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graf, D.R.; Jones, C.M.; Hallin, S. Intergenomic comparisons highlight modularity of the denitrification pathway and underpin the importance of community structure for N2O emissions. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e114118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, D.; Ray, A.; Kasrija, L.; Christian, J. Impacts of Climate Change and Agricultural Practices on Nitrogen Processes, Genes, and Soil Nitrous Oxide Emissions: A Quantitative Review of Meta-Analyses. Agriculture 2024, 14, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobbie, K.; Smith, K. The effects of temperature, water-filled pore space and land use on N2O emissions from an imperfectly drained gleysol. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2001, 52, 667–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, K.; Xu, X.; Zhao, Y.; Bai, T.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, H.; Sheng, X.; Bloszies, S.; et al. Intermediate soil acidification induces highest nitrous oxide emissions. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 2695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Guo, J.; Vogt, R.D.; Mulder, J.; Wang, J.; Zhang, X. Soil pH as the chief modifier for regional nitrous oxide emissions: New evidence and implications for global estimates and mitigation. Glob. Change Biol. 2018, 24, e617–e626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Lakshmanan, P.; Wang, X.; Xiong, H.; Yang, L.; Liu, B.; Shi, X.; Chen, X.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Global reactive nitrogen loss in orchard systems: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 821, 153462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zhang, N.; Li, Y.; Xu, S.; Liu, Y.; Miao, S.; Ding, W. Extreme Rainfall Amplified the Stimulatory Effects of Soil Carbon Availability on N2O Emissions. Glob. Change Biol. 2025, 31, e70164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, R.; Wakelin, S.A.; Liang, Y.; Hu, B.; Chu, G. Nitrous oxide emission and denitrifier communities in drip-irrigated calcareous soil as affected by chemical and organic fertilizers. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 612, 739–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blesh, J. Functional traits in cover crop mixtures: Biological nitrogen fixation and multifunctionality. J. Appl. Ecol. 2017, 55, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fageria, N.; Baligar, V.; Bailey, B. Role of Cover Crops in Improving Soil and Row Crop Productivity. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2005, 36, 2733–2757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalal, R.; Wang, W.; Robertson, G.; Parton, W. Nitrous oxide emission from Australian agricultural lands and mitigation options: A review. Soil Res. 2003, 41, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, S.; Dou, J.; Chen, F.; Ju, L.; Li, A. Analysis of observations on the urban surface energy balance in Beijing. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2012, 55, 1881–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Cai, Y.P.; Yang, Z.F.; Yin, X.A.; Tan, Q. Microbial nitrification, denitrification and respiration in the leached cinnamon soil of the upper basin of Miyun Reservoir. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 42032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Hu, S.; Guo, Z.; Cui, T.; Zhang, L.; Lu, C.; Yu, Y.; Luo, Z.; Fu, H.; Jin, Y. Effect of balanced nutrient fertilizer: A case study in Pinggu District, Beijing, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 754, 142069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhang, X.; Meng, Z.; Liu, G. Responses of peach trees to modified pruning 2. Cropping and fruit quality. N. Z. J. Crop Hortic. Sci. 1994, 22, 411–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, F.; Shi, H.; Gou, J.; Zhang, L.; Dai, Q.; Yan, Y. Responses of soil aggregate stability and soil erosion resistance to different bedrock strata dip and land use types in the karst trough valley of Southwest China. Int. Soil Water Conserv. Res. 2023, 12, 684–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mina, M.; Rezaei, M.; Sameni, A.; Ostovari, Y.; Ritsema, C. Predicting wind erosion rate using portable wind tunnel combined with machine learning algorithms in calcareous soils, southern Iran. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 304, 114171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, C.; Whisson, K.; Treble, K.; Roper, M.; Micin, S.; Ward, P. Biological nitrification inhibition by weeds: Wild radish, brome grass, wild oats and annual ryegrass decrease nitrification rates in their rhizospheres. Crop Pasture Sci. 2017, 68, 798–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Song, X.; Jiang, L.; Lin, H.; Yu, X.; Gao, X.; Zheng, F.; Tan, D.; Wang, M.; Shi, J.; et al. Strategies for Managing Soil Nitrogen to Prevent Nitrate-N Leaching in Intensive Agriculture System; InTech eBooks; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.J.; Truong, H.A.; Trịnh, C.S.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, S.; Hong, S.W.; Lee, H. NITROGEN RESPONSE DEFICIENCY 1-mediated CHL1 induction contributes to optimized growth performance during altered nitrate availability in Arabidopsis. Plant J. Cell Mol. Biol. 2020, 104, 1382–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piotrowska-Długosz, A.; Wilczewski, E. Effects of Catch Crops Cultivated for Green Manure on Soil C and N Content and Associated Enzyme Activities. Agriculture 2024, 14, 898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.; Xie, Y.; Wang, X. Enhancing soil health through balanced fertilization: A pathway to sustainable agriculture and food security. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1536524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, P.; Ma, H.; Deng, X.; Li, Y.; Tian, J.; Li, J.; Ma, E.; Xu, Z.; Xiao, D.; Bezemer, T.M.; et al. Microbiome-mediated alleviation of tobacco replant problem via autotoxin degradation after long-term continuous cropping. iMeta 2024, 3, e189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagner, M.; Räty, M.; Nikama, J.; Rasa, K.; Peltonen, S.; Vepsäläinen, J.; Keskinen, R. Slow pyrolysis liquid in reducing NH3 emissions from cattle slurry—Impacts on plant growth and soil organisms. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 784, 147139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saghaï, A.; Pold, G.; Jones, C.; Hallin, S. Phyloecology of nitrate ammonifiers and their importance relative to denitrifiers in global terrestrial biomes. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 8249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Tang, S.; Hu, R.; Wang, J.; Duan, P.; Xu, C.; Zhang, W.; Xu, M. Increased N2O emission due to paddy soil drainage is regulated by carbon and nitrogen availability. Geoderma 2023, 432, 116422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourenço, K.; Costa, O.; Cantarella, H.; Kuramae, E. Ammonia-oxidizing bacteria and fungal denitrifier diversity are associated with N2O production in tropical soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2022, 166, 108563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.F.; Huang, J.W.; Cai, Z.X.; Li, Q.S.; Sun, Y.Y.; Zhou, H.Z.; Zhu, H.; Song, X.S.; Wu, H.M. Differential Nitrous oxide emission and microbiota succession in constructed wetlands induced by nitrogen forms. Environ. Int. 2024, 183, 108369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, K.; Mary, B.; Renault, P. Nitrous oxide production by nitrification and denitrification in soil aggregates as affected by O2 concentration. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2004, 36, 687–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarlett, K.; Denman, S.; Clark, D.R.; Forster, J.; Vanguelova, E.; Brown, N.; Whitby, C. Relationships between nitrogen cycling microbial community abundance and composition reveal the indirect effect of soil pH on oak decline. ISME J. 2021, 15, 623–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Peng, L.; Gao, W.; Wu, D.; Zhang, W.; Wang, X.; Liu, H.; Li, Q.; Fan, C.; Chen, M. PBAT microplastics exacerbates N2O emissions from tropical latosols mainly via stimulating denitrification. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 495, 153681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.H.; Feng, J.; Bodelier, P.L.E.; Yang, Z.; Huang, Q.; Delgado-Baquerizo, M.; Cai, P.; Tan, W.; Liu, Y.R. Metabolic coupling between soil aerobic methanotrophs and denitrifiers in rice paddy fields. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 3471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlüter, S.; Lucas, M.; Grosz, B.; Ippisch, O.; Zawallich, J.; He, H.; Dechow, R.; Kraus, D.; Blagodatsky, S.; Şenbayram, M.; et al. The anaerobic soil volume as a controlling factor of denitrification: A review. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2024, 61, 343–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, S.; Liu, J.; Wang, J.; Xin, Y.; Sun, S.; Xia, X. Tracing Microbial Production and Consumption Sources of N2O in Rivers on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau via Isotopocule and Functional Microbe Analyses. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 7196–7205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, D.; Zhang, X.; Yu, Q.; Jin, Y.; Jiang, P.; Wu, S.; Liu, S.; Zou, J. Mitigation of N2O emissions in water-saving paddy fields: Evaluating organic fertilizer substitution and microbial mechanisms. J. Integr. Agric. 2024, 23, 3159–3173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, Z.; Sun, K.; Ren, J.; Xiao, Y.; Li, Y.; Gao, B.; Gunina, A.; Aloufi, A.; Kuzyakov, Y. Biochar and Microplastics Affect Microbial Necromass Accumulation and CO2 and N2O Emissions from Soil. ACS EST Eng. 2023, 4, 603–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harter, J.; Krause, H.M.; Schuettler, S.; Ruser, R.; Fromme, M.; Scholten, T.; Kappler, A.; Behrens, S. Linking N2O emissions from biochar-amended soil to the structure and function of the N-cycling microbial community. ISME J. 2014, 8, 660–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Elrys, A.S.; Merwad, A.M.; Zhang, H.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, J.; Cai, Z.; Müller, C. Global Patterns and Drivers of Soil Dissimilatory Nitrate Reduction to Ammonium. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 3791–3800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timilsina, A.; Neupane, P.; Yao, J.; Raseduzzaman, M.; Bizimana, F.; Pandey, B.; Feyissa, A.; Li, X.; Dong, W.; Yadav, R.K.P.; et al. Plants mitigate ecosystem nitrous oxide emissions primarily through reductions in soil nitrate content: Evidence from a meta-analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 949, 175115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.H.; Kim, H.; Park, Y.L.; Horn, M.A.; Kim, J.; Lee, J.; Toyoda, S.; Yun, J.; Kang, H.; Kim, S.Y.; et al. Exploring Sulfate as an Alternative Electron Acceptor: A Potential Strategy to Mitigate N2O Emissions in Upland Arable Soils. Glob. Change Biol. 2025, 31, e70428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Q.; Moeskjær, S.; Cotton, A.; Dai, W.; Wang, X.; Yan, X.; Daniell, T.J. Organic fertilization reduces nitrous oxide emission by altering nitrogen cycling microbial guilds favouring complete denitrification at soil aggregate scale. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 946, 174178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Xia, X.; Liu, S.; Zhang, S.; Yan, W.; McDowell, W.H. Distinctive Patterns and Controls of Nitrous Oxide Concentrations and Fluxes from Urban Inland Waters. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 8422–8431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carciochi, W.; Gabriel, J.; Wyngaard, N. Editorial: Cover crops and green manures: Providing services to agroecosystems. Front. Soil Sci. 2024, 4, 1518511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoogsteen, M.; Bakker, E.; Eekeren, N.; Tittonell, P.; Groot, J.; Ittersum, M.; Lantinga, E. Do Grazing Systems and Species Composition Affect Root Biomass and Soil Organic Matter Dynamics in Temperate Grassland Swards? Sustainability 2020, 12, 1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Liu, L.; Qin, S.; Yang, G.; Fang, K.; Zhu, B.; Kuzyakov, Y.; Chen, P.; Xu, Y.; Yang, Y. Regulation of priming effect by soil organic matter stability over a broad geographic scale. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 5112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Fang, J.; Ma, W.; Smith, P.; Mohammat, A.; Wang, S.; Wang, W. Soil carbon stock and its changes in northern China’s grasslands from 1980s to 2000s. Glob. Change Biol. 2010, 16, 3036–3047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, H.; Liu, J.; Huang, S.; Li, C.; Li, Y.; Xu, L.; Huang, Z.; Li, Q.; Shaghaleh, H.; Hamoud, Y.; et al. Subsurface Drainage and Biochar Amendment Alter Coastal Soil Nitrogen Cycling: Evidence from 15N Isotope Tracing—A Case Study in Eastern China. Water 2025, 17, 2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sennett, L.B.; Roco, C.A.; Lim, N.Y.N.; Yavitt, J.B.; Dörsch, P.; Bakken, L.R.; Shapleigh, J.P.; Frostegård, Å. Determining how oxygen legacy affects trajectories of soil denitrifier community dynamics and N2O emissions. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 7298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Patterns | CK | TPr | Tr | Pr |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatments | clean tillage | Trifolium repens and Lolium perenne mixed sowing | Trifolium repens monoculture | Lolium perenne monoculture |

| Seed amounts | 0 kg·667 m−2 | 0.5 and 1 kg·667 m−2 | 1 kg·667 m−2 | 2 kg·667 m−2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pang, Z.; Li, Y.; Xu, H.; Zhang, G.; Chen, C.; Lu, A.; Kan, H. Effects of Different Sod-Seeding Patterns on Soil Properties, Nitrogen Cycle Genes, and N2O Mitigation in Peach Orchards. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2744. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122744

Pang Z, Li Y, Xu H, Zhang G, Chen C, Lu A, Kan H. Effects of Different Sod-Seeding Patterns on Soil Properties, Nitrogen Cycle Genes, and N2O Mitigation in Peach Orchards. Agronomy. 2025; 15(12):2744. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122744

Chicago/Turabian StylePang, Zhuo, Yufeng Li, Hengkang Xu, Guofang Zhang, Chao Chen, Anxiang Lu, and Haiming Kan. 2025. "Effects of Different Sod-Seeding Patterns on Soil Properties, Nitrogen Cycle Genes, and N2O Mitigation in Peach Orchards" Agronomy 15, no. 12: 2744. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122744

APA StylePang, Z., Li, Y., Xu, H., Zhang, G., Chen, C., Lu, A., & Kan, H. (2025). Effects of Different Sod-Seeding Patterns on Soil Properties, Nitrogen Cycle Genes, and N2O Mitigation in Peach Orchards. Agronomy, 15(12), 2744. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122744