Soil Fertility Assessment and Spatial Heterogeneity of the Natural Grasslands in the Tibetan Plateau Using a Novel Index

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

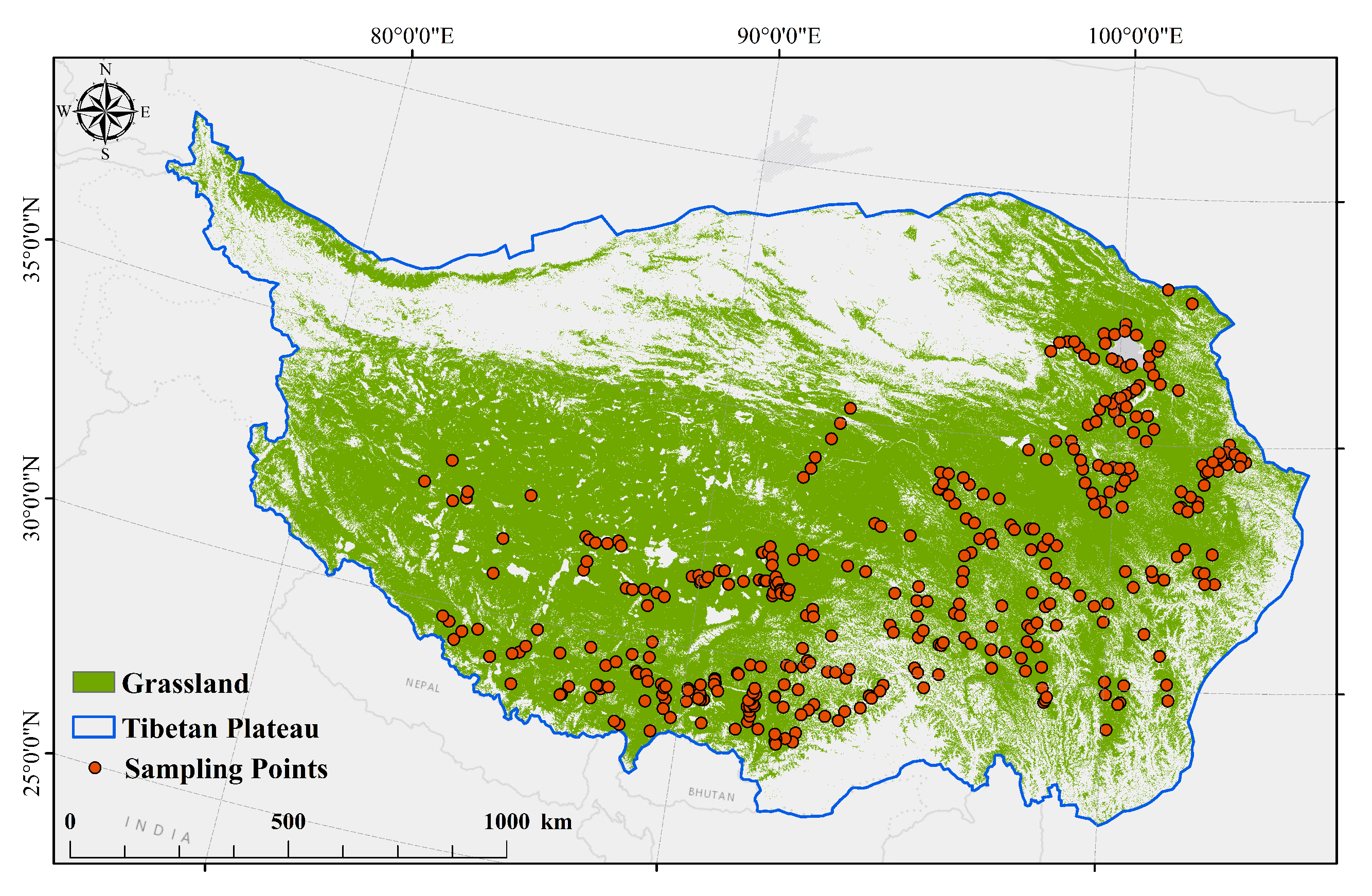

2.1. Study Area and Field Sampling

2.2. Soil Fertility Evaluation Indicator for Natural Grasslands

2.3. Soil Fertility Evaluation Index of Natural Grasslands in the Tibetan Plateau

2.3.1. Membership Functions for Indicators

2.3.2. Assigning Weights for Indicators

2.3.3. Soil Fertility Evaluation Index Calculation

2.4. Evaluation Metric

3. Results

3.1. Variations of Evaluation Indicators Across Fertility Grades

3.2. Membership Degrees and Weights for Evaluation Indicators

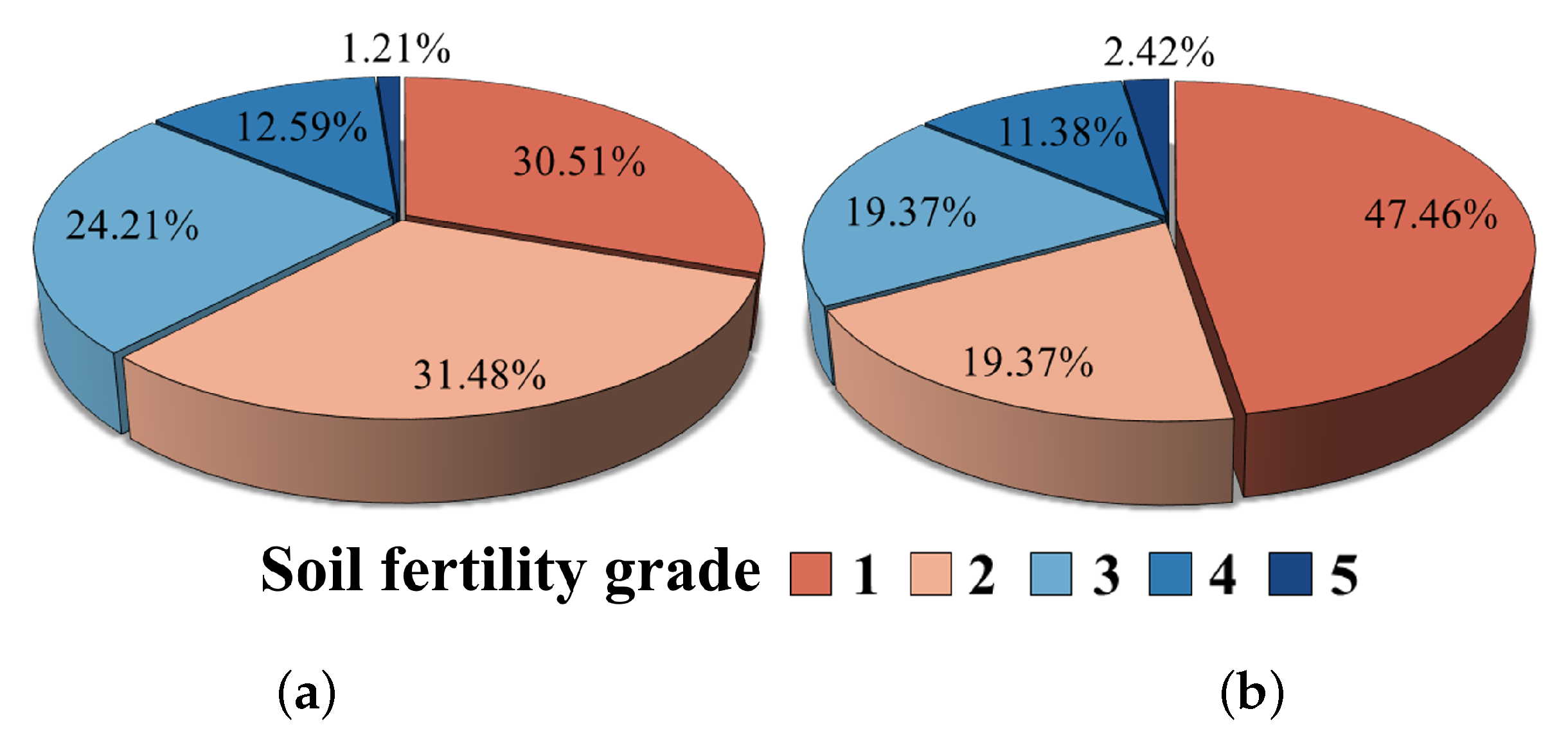

3.3. Soil Fertility Evaluation Results

3.4. Relative Contributions of Individual Indicators to the SFEI

3.5. Performance of the SFEI in Assessing Natural Grassland Fertility on the Tibetan Plateau

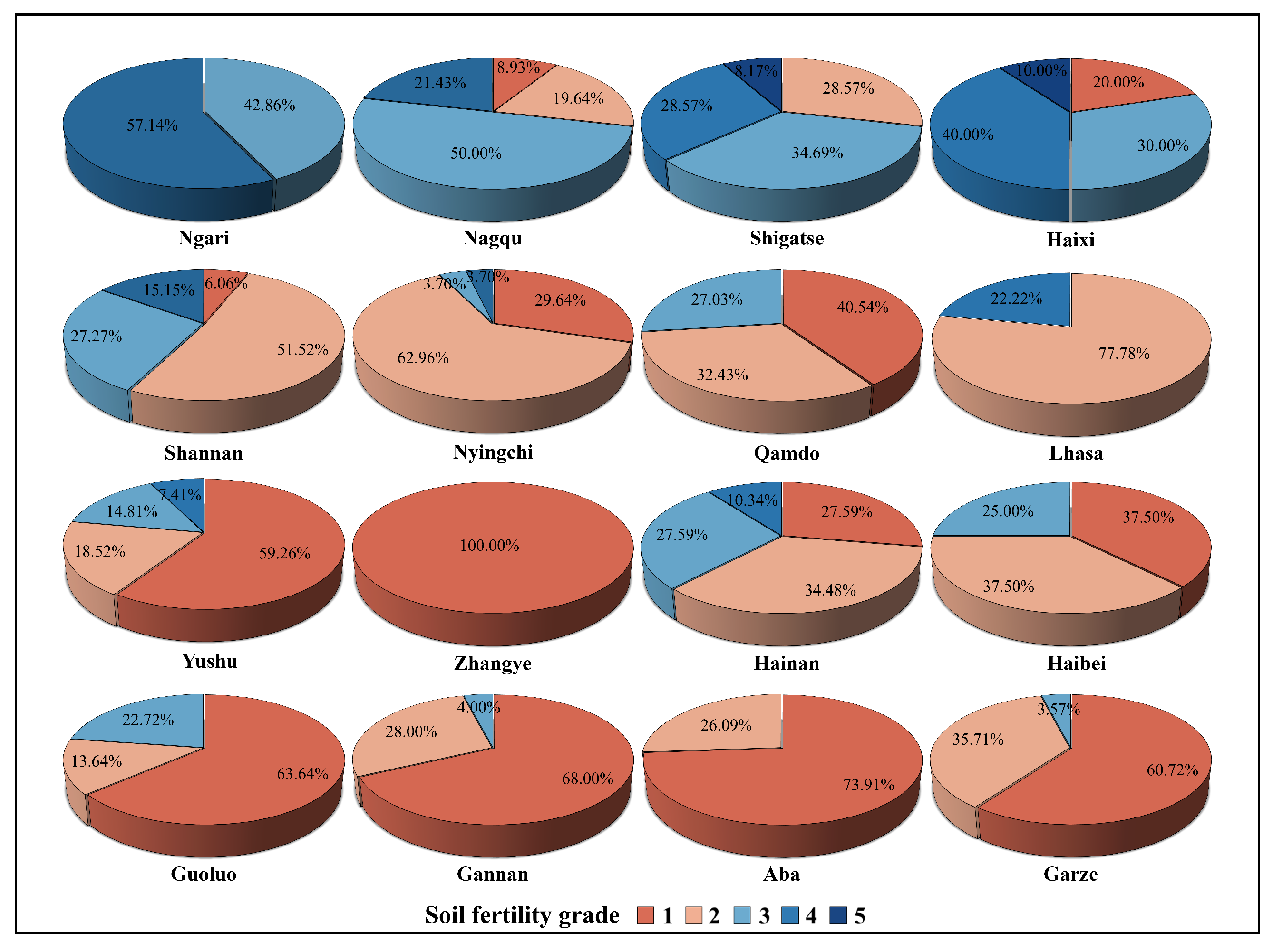

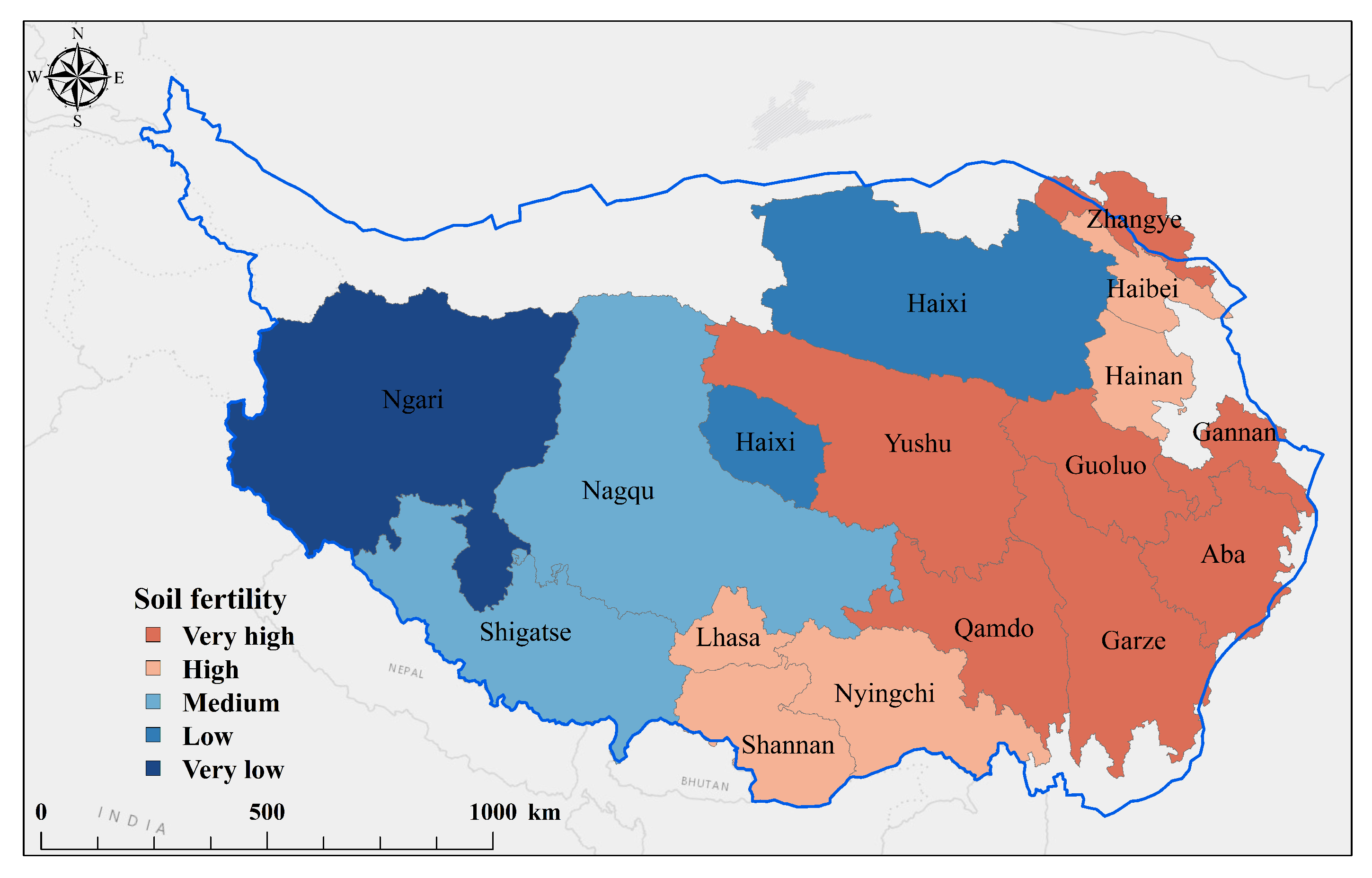

3.6. Spatial Patterns of Soil Fertility Across the Tibetan Plateau

3.7. Spatial Heterogeneity of Natural Grassland Soil Fertility on the Tibetan Plateau

4. Discussion

4.1. Contributions

4.2. Indicator Selection and Model Performance

4.3. Spatial Patterns and Environmental Drivers

4.4. Limitations and Future Work

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Muro, J.; Linstädter, A.; Magdon, P.; Wöllauer, S.; Männer, F.; Schwarz, L.M.; Ghazaryan, G.; Schultz, J.; Malenovskỳ, Z.; Dubovyk, O. Predicting Plant Biomass and Species Richness in Temperate Grasslands across Regions, Time, and Land Management with Remote Sensing and Deep Learning. Remote Sens. Environ. 2022, 282, 113262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punalekar, S.; Verhoef, A.; Quaife, T.; Humphries, D.; Bermingham, L.; Reynolds, C. Application of Sentinel-2A Data for Pasture Biomass Monitoring Using a Physically Based Radiative Transfer Model. Remote Sens. Environ. 2018, 218, 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, K.; Senf, C.; Okujeni, A.; Hostert, P. Large-scale Remote Sensing Analysis Reveals an Increasing Coupling of Grassland Vitality to Atmospheric Water Demand. Glob. Change Biol. 2024, 30, e17315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doran, J.; Parkin, T. Defining and Assessing Soil Quality. In Defining Soil Quality for a Sustainable Environment; Soil Science Society of America, Inc.: Madison, WI, USA, 1994; Volume 35, pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, M.; Lu, R.; Zhao, J.; Ma, L. Assessment of Soil Quality in Typical Wind Erosion Area of Qaidam Basin. J. Desert Res. 2023, 43, 199–209. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, T.; Wang, W.; An, B.; Piao, S.; Chen, F. The Scientific Expedition and Research Activities on the Tibetan Plateau in 1949–2017. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2022, 77, 1586–1602. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Lv, W.; Xue, K.; Wang, S.; Zhang, L.; Hu, R.; Zeng, H.; Xu, X.; Li, Y.; Jiang, L.; et al. Grassland Changes and Adaptive Management on the Qinghai–Tibetan Plateau. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2022, 3, 668–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Lu, H.; Wang, J.; Wang, X.; Sun, J. Dual Influence of Climate Change and Anthropogenic Activities on the Spatiotemporal Vegetation Dynamics over the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau from 1981 to 2015. Earth’s Future 2022, 10, e2021EF002566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chongyi, E.; Yang, F.; Shi, Y.; Xie, L. OSL Ages and Pedogenic Mode of Kobresia Mattic Epipedon on the Northeastern Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Catena 2023, 223, 106912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wu, T.; Zou, D.; Liu, L.; Wu, X.; Gong, W.; Zhu, X.; Li, R.; Hao, J.; Hu, G.; et al. Magnitudes and Patterns of Large-Scale Permafrost Ground Deformation Revealed by Sentinel-1 InSAR on the Central Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Remote Sens. Environ. 2022, 268, 112778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.; Pang, B.; Zhao, L.; Shu, S.; Feng, P.; Liu, F.; Du, Z.; Wang, X. Soil Phosphorus Crisis in the Tibetan Alpine Permafrost Region. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 6204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, J.; Bossio, D.; Kögel-Knabner, I.; Rillig, M.C. The Concept and Future Prospects of Soil Health. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2020, 1, 544–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Gan, Q.; Huang, L.; Pan, X.; Liu, T.; Wang, R.; Wang, L.; Zhang, L.; Li, H.; Wang, L.; et al. Effects of Forest Thinning on Soil Microbial Biomass and Enzyme Activity. Catena 2024, 239, 107938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommer, L.; Donath, T.; Harvolk-Schöning, S.; Kleinebecker, T.; Schneider, S.; Voß, N.; Klinger, Y.P. Grassland Restoration Practice in Central Europe: Drivers of Success across a Broad Moisture Gradient. Restor. Ecol. 2025, 33, e70106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Zou, C.; Chen, F.; Yuan, Y.; Pan, J.; Zhao, Q.; Wang, M.; Qiao, L.; Cheng, H.; Ding, C.; et al. Response of 2, 4, 6-trichlorophenol-reducing Biocathode to Burial Depth in Constructed Wetland Sediments. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 426, 128066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, G.; Huang, X.; Chen, S.; Hu, C.; Zhong, C.; Xu, C.; Zhang, Z. Biotic and Abiotic Factors Affecting Soil C, N, P and Their Stoichiometries under Different Land-Use Types in a Karst Agricultural Watershed, China. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Gonzalez, F.; Vuelvas, J.; Correa, C.; Vallejo, V.E.; Patino, D. Machine Learning and Remote Sensing Techniques Applied to Estimate Soil Indicators–Review. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 135, 108517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Wang, T.; Ji, X.; Wei, L.; Wei, J.; Cao, Y.; Ding, J. Grazing Reverses Climate-Induced Soil Carbon Gains on the Tibetan Plateau. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 6978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Du, W.; Song, C.; Li, H.; Zhu, J.; Liang, N. Long-Term Multi-Nutrient Enrichment Enhances Aboveground Biomass without Compromising Ecosystem Temporal Stability in a Tibetan Alpine Meadow. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2025, 394, 109917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Dong, S.; Xu, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, S.; Wu, S.; Shen, H.; Liu, S.; Fry, E.L. Revegetation Significantly Increased the Bacterial-Fungal Interactions in Different Successional Stages of Alpine Grasslands on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Catena 2021, 205, 105385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Wu, L.; He, C.; Shao, H. Study on Spatiotemporal Variation Pattern of Vegetation Coverage on Qinghai–Tibet Plateau and the Analysis of Its Climate Driving Factors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Hou, X.; Xu, L.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, Y.; Guo, Z.; Adomako, M.O.; Ma, Q. Belowground Bud Banks and Land Use Change: Roles of Vegetation and Soil Properties in Mediating the Composition of Bud Banks in Different Ecosystems. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 14, 1330664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NY/T 1121.24-2012; Soil Testing—Part 24: Determination of Total Nitrogen in Soil by Automatic Kjeldahl Apparatus. Ministry of Agriculture of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2012. (In Chinese)

- NY/T 1121.6-2006; Soil Testing—Part 6: Determination of Soil Organic Matter. Ministry of Agriculture of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2006. (In Chinese)

- Mu, X.; Song, W.; Gao, Z.; McVicar, T.R.; Donohue, R.J.; Yan, G. Fractional vegetation cover estimation by using multi-angle vegetation index. Remote Sens. Environ. 2018, 216, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Li, W.; Wei, T.; Huang, R.; Zeng, Z. Patterns and Mechanisms of Legume Responses to Nitrogen Enrichment: A Global Meta-Analysis. Plants 2024, 13, 3244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NY/T 1121.4-2006; Soil Testing—Part 4: Determination of Bulk Density of Soil. Ministry of Agriculture of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2006. (In Chinese)

- He, J.; Zhang, X.; Xue, Y.; Yu, L.; Zhang, P. Fuzzy Comprehensive Evaluation of Effectiveness Based on Improved Membership Function. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE International Conference on Mechatronics and Automation (ICMA), Beijing, China, 3–6 August 2025; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2025; pp. 426–431. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, J.; Wang, L.; Müller, K.; Wu, J.; Wang, H.; Zhao, K.; Berninger, F.; Fu, W. A 10-year monitoring of soil properties dynamics and soil fertility evaluation in Chinese hickory plantation regions of southeastern China. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 23531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhry, H.; Vasava, H.B.; Chen, S.; Saurette, D.; Beri, A.; Gillespie, A.; Biswas, A. Evaluating the soil quality index using three methods to assess soil fertility. Sensors 2024, 24, 864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, A.; Sun, Y.; Wang, J.; Pang, H.; Peng, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, J.; Giannico, V.; Legesse, T.G.; et al. Deep Multi-Order Spatial–Spectral Residual Feature Extractor for Weak Information Mining in Remote Sensing Imagery. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Zhai, L.; Sang, H.; Cheng, S.; Li, H. Effects of hydrothermal factors and human activities on the vegetation coverage of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 12488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Wu, T.; Li, R.; Xie, C.; Hu, G.; Qin, Y.; Wang, W.; Hao, J.; Yang, S.; Ni, J.; et al. Impacts of summer extreme precipitation events on the hydrothermal dynamics of the active layer in the Tanggula permafrost region on the Qinghai-Tibetan plateau. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2017, 122, 11–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, K.; Don, A.; Tiemeyer, B.; Freibauer, A. Determining soil bulk density for carbon stock calculations: A systematic method comparison. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2016, 80, 579–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Yang, J.; Guan, W.; Liu, Z.; He, G.; Zhang, D.; Liu, X. Soil fertility evaluation and spatial distribution of grasslands in Qilian Mountains Nature Reserve of eastern Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. PeerJ 2021, 9, e10986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenka, N.K.; Meena, B.P.; Lal, R.; Khandagle, A.; Lenka, S.; Shirale, A.O. Comparing four indexing approaches to define soil quality in an intensively cropped region of Northern India. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 865473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Statistic | TN (g/kg) | SOM (g/kg) | BD (g/cm3) | FVC (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min | 0.20 | 1.94 | 0.89 | 5.00 |

| Max | 12.64 | 206.65 | 2.01 | 100.00 |

| Mean | 2.74 | 43.31 | 1.39 | 74.69 |

| Std | 2.04 | 35.58 | 0.22 | 25.2 |

| K | 2.59 | 2.28 | −0.63 | −0.48 |

| CV | 0.74 | 0.82 | 0.16 | 0.34 |

| SFEI | >0.8 | ≤0.2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Interpretation | Highest | High | Medium | Low | Lowest |

| Cluster | TN (g/kg) | SOM (g/kg) | BD (g/cm3) | FVC (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | >7.8 | >115 | <1.14 | >90 |

| 2 | 4.5–7.8 | 75–115 | 1.14–1.31 | 75–90 |

| 3 | 2.7–4.5 | 45–75 | 1.31–1.48 | 50–75 |

| 4 | 1.3–2.7 | 21.5–45 | 1.48–1.66 | 30–50 |

| 5 | <1.3 | <21.5 | >1.66 | <30 |

| Grade | TN (g/kg) | SOM (g/kg) | BD (g/cm3) | FVC (%) | Membership Degree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | >7.8 | >80 | <1.14 | >80 | 1.0 |

| 2 | 4.5–7.8 | 60–80 | 1.14–1.48 | 70–80 | 0.8 |

| 3 | 2.7–4.5 | 40–60 | 1.31–1.48 | 60–70 | 0.6 |

| 4 | 1.3–2.7 | 20–40 | 1.48–1.66 | 50–60 | 0.4 |

| 5 | <1.3 | <20 | >1.66 | <50 | 0.2 |

| Indicator | TN | SOM | BD | FVC |

| Weight | 0.2625 | 0.2625 | 0.2250 | 0.2500 |

| TN | SOM | BD | FVC | F1-Score (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 69.89 |

| ∘ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 32.87 |

| ✓ | ∘ | ✓ | ✓ | 32.60 |

| ✓ | ✓ | ∘ | ✓ | 68.78 |

| ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ∘ | 46.69 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, X.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, K.; Shao, C.; Zhang, A.; Chen, Y.; Hou, L. Soil Fertility Assessment and Spatial Heterogeneity of the Natural Grasslands in the Tibetan Plateau Using a Novel Index. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2743. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122743

Zhang X, Zhang K, Zhang K, Shao C, Zhang A, Chen Y, Hou L. Soil Fertility Assessment and Spatial Heterogeneity of the Natural Grasslands in the Tibetan Plateau Using a Novel Index. Agronomy. 2025; 15(12):2743. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122743

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Xizhen, Kun Zhang, Kun Zhang, Changliang Shao, Aiwu Zhang, Youliang Chen, and Lulu Hou. 2025. "Soil Fertility Assessment and Spatial Heterogeneity of the Natural Grasslands in the Tibetan Plateau Using a Novel Index" Agronomy 15, no. 12: 2743. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122743

APA StyleZhang, X., Zhang, K., Zhang, K., Shao, C., Zhang, A., Chen, Y., & Hou, L. (2025). Soil Fertility Assessment and Spatial Heterogeneity of the Natural Grasslands in the Tibetan Plateau Using a Novel Index. Agronomy, 15(12), 2743. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122743