Hydrogen Sulfide Is Involved in Melatonin-Induced Drought Tolerance in Maize (Zea mays “Beiqing340”)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design

2.2. Endogenous H2S Content

2.3. Endogenous Melatonin Content

2.4. Plant Dry Weight, Photosynthetic Parameters, and Fv/Fm

2.5. Starch and Sugar Contents

2.6. Lipid Peroxidation

2.7. Antioxidant Enzyme Activities

2.8. Non-Enzymatic Antioxidant Content

2.9. RNA Extraction and Quantitative RT-PCR

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

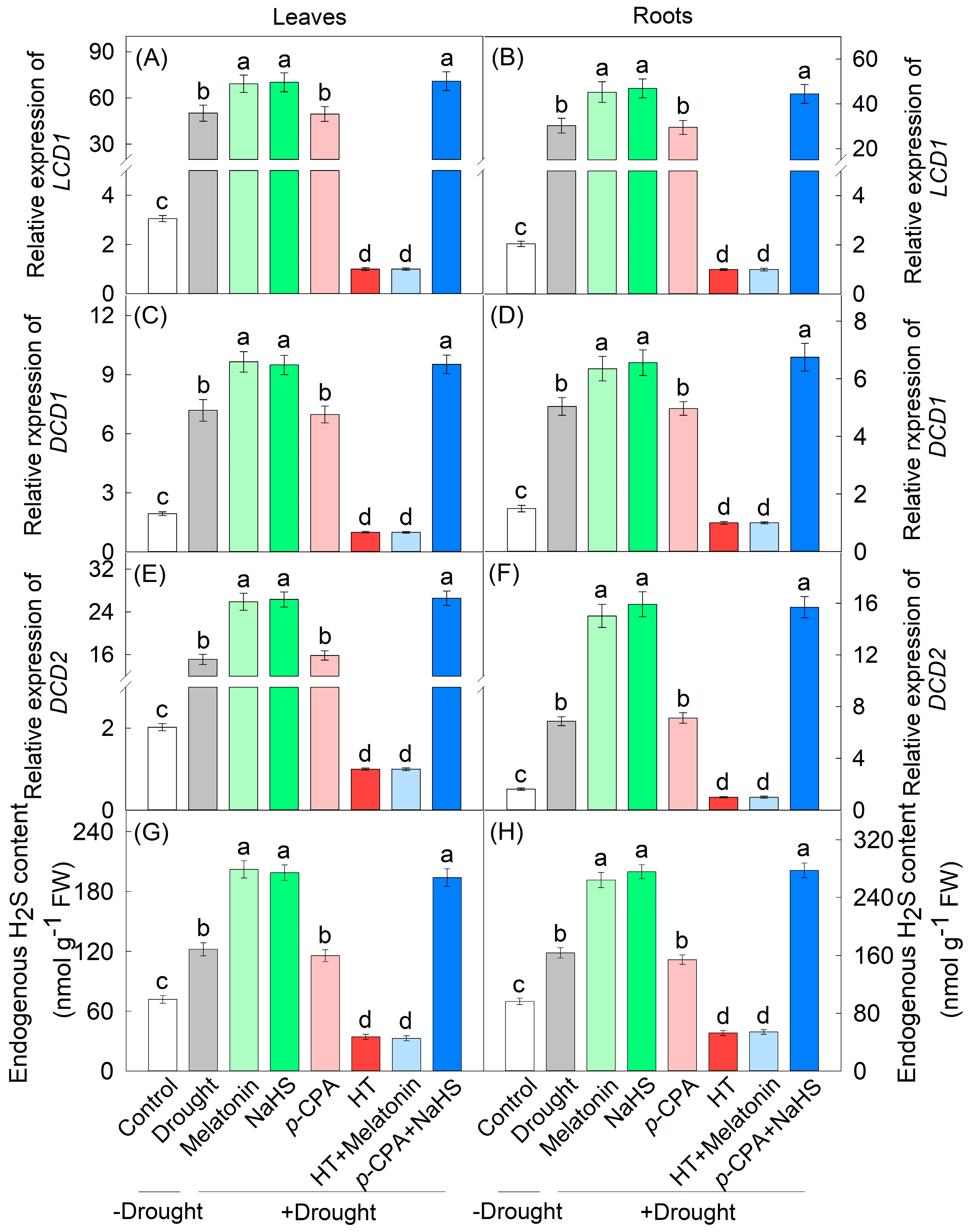

3.1. Induction of H2S Production by Drought Stress and Melatonin

3.2. Melatonin and NaHS Promote Plant Growth Under Drought Stress

3.3. Melatonin and NaHS Improve Photosynthesis in Drought-Stressed Maize Seedlings

3.4. Melatonin and NaHS Enhance Osmotic Adjustment Capacity in Drought-Stressed Maize Seedlings

3.5. Melatonin and NaHS Alleviate Oxidative Damage in Drought-Stressed Maize Seedlings

3.6. Melatonin and NaHS Enhance Antioxidant Capacity in Drought-Stressed Maize Seedlings

3.7. Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| H2S | Hydrogen sulfide |

| HT | Hydroxylamine |

| p-CPA | P-chlorophenylalanine |

| H2O2 | Hydrogen peroxide |

| O2·− | Superoxide anion |

| MDA | Malondialdehyde |

| SOD | Superoxide dismutase |

| CAT | Catalase |

| POD | Peroxidase |

| ASA | Ascorbic acid |

| DHA | Dehydroascorbic acid |

| GSH | Glutathione |

| GSSG | Oxidized glutathione |

| LCD/DCD | L-/D-cysteine desulfhydrase |

| T5H | Tryptamine 5-hydroxylase |

| SNAT | Serotonin-N-acetyltransferase |

| ASMT | Acetylserotonin O-methyltransferase |

| AMY | Alpha-amylase |

| BMY | Beta-amylase |

| SPS | Sucrose phosphate synthase |

| SuSy | Sucrose synthase |

| INV | Invertase |

References

- Seki, M.; Umezawa, T.; Urano, K.; Shinozaki, K. Regulatory metabolic networks in drought stress responses. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2007, 10, 296–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahedi, S.M.; Karimi, M.; Venditti, A. Plants adapted to arid areas: Specialized metabolites. Nat. Prod. Res. 2021, 35, 3314–3331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvi, P.; Manna, M.; Kaur, H.; Thakur, T.; Gandass, N.; Bhatt, D.; Muthamilarasan, M. Phytohormone signaling and crosstalk in regulating drought stress response in plants. Plant Cell Rep. 2021, 40, 1305–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.N.; Khan, Z.; Luo, T.; Liu, J.; Rizwan, M.; Zhang, J.; Xu, Z.; Wu, H.; Hu, L. Seed priming with gibberellic acid and melatonin in rapeseed: Consequences for improving yield and seed quality under drought and non-stress conditions. Ind. Crops Prod. 2020, 156, 112850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, T.; Wang, Z.X.; Dong, Y.L.; Cao, J.; Lin, R.T.; Wang, X.T.; Yu, Z.Q.; Chen, Y.X. Role of melatonin in sleep deprivation induced intestinal barrier dysfunction in mice. J. Pineal Res. 2019, 67, e12574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombage, R.; Singh, M.B.; Bhalla, P.L. Melatonin and abiotic stress tolerance in crop plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 7447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Geng, G.; Mei, S.; Wang, G.; Yu, L.; Xu, Y.; Wang, Y. Melatonin modulates the tolerance of plants to water stress: Morphological response of the molecular mechanism. Funct. Plant Biol. 2024, 51, FP23199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dzinyela, R.; Manda, T.; Hwarari, D.; Ramakrishnan, M.; Ahmad, Z.; Agassin, R.H.; Movahedi, A. Melatonin-mediated phytohormonal crosstalk improves salt stress tolerance in plants. Planta 2025, 262, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Chen, A.; Wei, Q.; Wang, C.; Zhao, Q.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, Q.; Wang, Q.; Zheng, X.; He, T.; et al. Exogenous melatonin inhibits the expression of GmABI5 and enhances drought resistance in fodder soybean through an ABA-independent pathway. Plant Cell Environ. 2025, 48, 8341–8355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, C.; Wang, L.; Mao, Y.; Li, Y.; Peng, Y.; Fan, Y.; Li, J.; Zhu, Y.; Xu, X.; Li, P. Melatonin integrates multiple biological and phytohormonal pathways to enhance drought tolerance in rice. Planta 2025, 262, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahammed, G.J.; Li, Z.; Chen, J.; Dong, Y.; Qu, K.; Guo, T.; Wang, F.H.; Liu, A.R.; Chen, S.C.; Li, X. Reactive oxygen species signaling in melatonin-mediated plant stress response. Plant Physiol. Bioch. 2024, 207, 108398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corpas, F.J.; Rivero, R.M.; Freschi, L.; Palma, J.M. Functional interactions among H2O2, NO, H2S, and melatonin in the physiology, metabolism, and quality of horticultural Solanaceae. J. Exp. Bot. 2025, 76, 3634–3656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, S.; Singh, S.P.; Singh, S.; Gupta, R.; Tripathi, D.K.; Corpas, F.J.; Singh, V.P. Hydrogen sulphide: A key player in plant development and stress resilience. Plant Cell Environ. 2025, 48, 2445–2459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Xie, Y.; Van Breusegem, F.; Huang, J. Hydrogen sulfide and protein persulfidation in plant stress signaling. J. Exp. Bot. 2025, 76, eraf100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.L.; Zhang, W.; Niu, J.; Ren, Y.; Zhang, F. Hydrogen sulfide may function downstream of hydrogen peroxide in salt stress-induced stomatal closure in Vicia faba. Funct. Plant Biol. 2018, 46, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Zhu, Y.Q.; He, X.S.; Yong, B.; Peng, Y.; Zhang, X.Q.; Ma, X.; Yan, Y.H.; Huang, L.K.; Nie, G. The hydrogen sulfide, a downstream signaling molecule of hydrogen peroxide and nitric oxide, involves spermidine-regulated transcription factors and antioxidant defense in white clover in response to dehydration. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2019, 161, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Ma, C.; Kang, X.; Zhang, L.; Wang, J.; Zheng, S.; Zhang, T. Hydrogen sulfide and nitric oxide are involved in melatonin-induced salt tolerance in cucumber. Plant Physiol. Bioch. 2021, 167, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Pei, Z.Q.; Zhu, Q.; Chai, C.H.; Guo, T.; Mou, X.X.; Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Zhang, T.; Zheng, S. Hydrogen sulfide as a key mediator in melatonin-induced enhancement of cold tolerance in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) seedlings. Plant Sci. 2025, 362, 112784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, A. Osmotic adjustment is a prime drought stress adaptive engine in support of plant production. Plant Cell Environ. 2017, 40, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supriya, L.; Shukla, P.; Dake, D.; Gudipalli, P.; Muthamilarasan, M. Physio-biochemical and molecular analyses decipher distinct dehydration stress responses in contrasting genotypes of foxtail millet (Setaria italica L.). J. Plant Physiol. 2025, 311, 154549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.H.; Yang, X.X.; Zhang, N.; Feng, L.; Ma, C.Y.; Wang, Y.L.; Yang, Z.P.; Zhao, J. Melatonin alleviates aluminum-induced growth inhibition by modulating carbon and nitrogen metabolism, and reestablishing redox homeostasis in Zea mays L. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 423, 127159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Wei, S.; Chen, D.; Guo, Y.; Ma, B.; Riao, D.; Zhang, J.; Tong, Z.; Liu, X.; Zhao, C. Determining the dynamic response of maize to compound low-temperature and drought stress. Eur. J. Agron. 2026, 172, 127842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagal, D.; Guleria, A.; Chowdhary, A.A.; Verma, P.K.; Mishra, S.; Rathore, S.; Srivastava, V. Unveiling the role and crosstalk of hydrogen sulfide with other signalling molecules enhances plant tolerance to water scarcity. Physiol. Plant. 2025, 177, e70222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rai, K.K.; Corpas, F.J. Interplay between transcription factors and redox-related genes in ROS, RNS and H2S signalling during plant stress responses. Plant Cell Environ. 2025, 48, 7796–7814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Yan, R.; Zhang, H.; Yin, L.; Lei, W.; Cheng, J.; Hua, C.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, X.; Shen, S. p-chlorophenylalanine treatment accelerates tomato fruit ripening through hormone synthesis and glycolytic pathway during storage. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2025, 225, 113517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basak, G.; Barman, C.; Subba, R.; Sk, B.; Aktar, S.; Ghosh, N.; Mukherjee, S. Melatonin priming elevates hydrogen sulfide metabolism, reduces Na+ uptake and reprograms NaCl stress-induced metabolic signatures in sunflower seedling leaves. Plant Physiol. Bioch. 2025, 229, 110305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardıç, Ş.K.; Szafrańska, K.; Havan, A.; Karaca, A.; Aslan, M.Ö.; Sözeri, E.; Yakupoglu, G.; Korkmaz, A. Endogenous melatonin content confers drought stress tolerance in pepper. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2023, 216, 105536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Zou, Q.; Yang, G.; Jiang, S.; Fang, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, N.; Chen, X. MdMYB6 regulates anthocyanin formation in apple both through direct inhibition of the biosynthesis pathway and through substrate removal. Hortic. Res. 2020, 7, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reguera, M.; Peleg, Z.; Abdel-Tawab, Y.M.; Tumimbang, E.B.; Delatorre, C.A.; Blumwald, E. Stress-induced cytokinin synthesis increases drought tolerance through the coordinated regulation of carbon and nitrogen assimilation in Rice. Plant Physiol. 2013, 163, 1609–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.L.; Tian, Y.; Li, L.; Yu, M.; Hou, R.P.; Ren, X.M. H2S alleviates salinity stress in cucumber by maintaining the Na+/K+ balance and regulating H2S metabolism and oxidative stress response. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Peng, Y.; Zhu, L.; Huang, Y.; Bie, Z.; Wu, H. CS nanoparticles improved cucumber salt tolerance is associated with its induced early stimulation on antioxidant system. Chemosphere 2022, 299, 134474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, C.; Ugurlar, F.; Ashraf, M.; Alyemeni, M.N.; Bajguz, A.; Ahmad, P. The involvement of hydrogen sulphide in melatonin-induced tolerance to arsenic toxicity in pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) plants by regulating sequestration and subcellular distribution of arsenic, and antioxidant defense system. Chemosphere 2022, 309, 136678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Guo, L.; Liu, L. Exogenous silicon alleviates drought stress in maize by improving growth, photosynthetic and antioxidant metabolism. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2022, 201, 104974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, C.; Ashraf, M.; Alyemeni, M.N.; Ahmad, P. Responses of nitric oxide and hydrogen sulfide in regulating oxidative defence system in wheat plants grown under cadmium stress. Physiol. Plant. 2020, 168, 345–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, C.N.; Ávila, R.G.; de Souza, K.R.D.; Azevedo, L.M.; Alves, J.D. Melatonin reduces oxidative stress and promotes drought tolerance in young Coffea arabica L. plants. Agric. Water Manag. 2019, 211, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.X.; He, J.; Ding, H.D.; Zhu, Z.W.; Chen, J.L.; Xu, S.; Zha, D.S. Modulation of zinc-induced oxidative damage in Solanum melongena by 6-benzylaminopurine involves ascorbate–glutathione cycle metabolism. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2015, 116, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catala, R.; Lopez-Cobollo, R.; Castellano, M.M.; Angosto, T.; Alonso, J.M.; Ecker, J.R.; Salinas, J. The Arabidopsis 14-3-3 protein RARE COLD INDUCIBLE 1A links low-temperature response and ethylene biosynthesis to regulate freezing tolerance and cold acclimation. Plant Cell 2014, 26, 3326–3342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, N.; Huang, W.; Li, X.; Gao, X.; Liu, X.; Wang, L.; Xing, W. Drilling into the physiology, transcriptomics, and metabolomics to enhance insight on Vallisneria denseserrulata responses to nanoplastics and metalloid co-stress. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 448, 141653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, H.; Wen, X.; Wang, Z.; Yin, S. Microbial memory of drought reshapes root-associated communities to enhance plant resilience. Plant Cell Environ. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Liu, J.; Suo, L.; Li, D.; He, L.; Duan, J.; Wang, Y.; Feng, W.; Guo, T. Exogenous melatonin alleviates drought stress in wheat by enhancing photosynthesis and carbon metabolism to promote floret development and grain yield. Plant Stress 2025, 16, 100885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Yazied, A.A.; Ibrahim, M.F.; Ibrahim, M.A.; Nasef, I.N.; Al-Qahtani, S.M.; Al-Harbi, N.A.; Alzuaibr, F.M.; Alaklabi, A.; Dessoky, E.S.; Alabdallah, N.M.; et al. Melatonin mitigates drought induced oxidative stress in potato plants through modulation of osmolytes, sugar metabolism, ABA homeostasis and antioxidant enzymes. Plants 2022, 11, 1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muslemyar, Q.S.; Kaya, C. Melatonin and L-cysteine desulfhydrase: Unraveling hydrogen sulfide signaling for drought tolerance in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum). Food Energy Secur. 2025, 14, e70103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; He, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Quinet, M.; Meng, Y. Exogenous melatonin enhances drought tolerance and germination in common buckwheat seeds through the coordinated effects of antioxidant and osmotic regulation. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 613. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, R.; Alsahli, A.A.; Alansi, S.; Altaf, M.A. Exogenous melatonin confers drought stress by promoting plant growth, photosynthetic efficiency and antioxidant defense system of pea (Pisum sativum L.). Sci. Hortic. 2023, 322, 112431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, L.; Yu, Y.; Zeng, H.; Deng, L.; Zhu, L.; Chen, G.; Wang, Y. Melatonin-induced resilience strategies against the damaging impacts of drought stress in rice. Agronomy 2022, 12, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.; Wang, D.; Delaplace, P.; Pan, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Tang, W.; Chen, K.; Chen, J.; Xu, Z.; Ma, Y.; et al. Melatonin enhances drought tolerance by affecting jasmonic acid and lignin biosynthesis in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Plant Physiol. Bioch. 2023, 202, 107974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Sehar, Z.; Fatma, M.; Mir, I.R.; Iqbal, N.; Tarighat, M.A.; Abdi, G.; Khan, N.A. Involvement of ethylene in melatonin-modified photosynthetic-N use efficiency and antioxidant activity to improve photosynthesis of salt grown wheat. Physiol. Plant. 2022, 174, e13832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Shi, Q.; Wang, X.; Zhang, T.; Feng, K.; Wang, G.; Zhao, J.; Yuan, X.; Ren, J. Melatonin-induced chromium tolerance requires hydrogen sulfide signaling in maize. Plants 2024, 13, 1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, M.H.; Khan, M.N.; Mukherjee, S.; Basahi, R.A.; Alamri, S.; Al-Amri, A.A.; Alsubaie, Q.D.; Ali, H.M.; Al-Munqedhi, B.M.A.; Almohisen, I.A.A. Exogenous melatonin-mediated regulation of K+/Na+ transport, H+-ATPase activity and enzymatic antioxidative defence operate through endogenous hydrogen sulphide signalling in NaCl-stressed tomato seedling roots. Plant Biol. 2021, 23, 797–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Liang, X.; Liu, R.; Liu, C.; Luo, S.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Z.; Xue, S. Hydrogen sulfide inhibits Arabidopsis inward potassium channels via protein persulfidation. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2025, 67, 1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Zhang, W.; Cheng, H.; Deng, Y.; Yao, B.; Shangguan, Z.; Wei, G.; Chen, J. Rhizobia cystathionine γ-lyase-derived H2S delays nodule senescence in soybean. Plant Physiol. 2024, 196, 2232–2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.; Li, W.; Wang, J.; Sun, G.; Ma, Y.; Li, F.; Shi, W.; Hu, Y.; Jia, H.; Li, J. Hydrogen sulfide enhances Cd tolerance through persulfidation of SlGSTU24 in Solanum lycopersicum L. Plant Soil 2025, 514, 3101–3118. Plant Soil 2025, 514, 3101–3118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Zhao, M.; Liu, R.; Xue, C.; Xia, Z.; Hu, B.; Rennenberg, H. Drought-mediated oxidative stress and its scavenging differ between citrus hybrids with medium and late fruit maturation. Plant Stress 2024, 14, 100670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.Z.; Liu, J.; Li, N.Y.; Zhang, D.D.; Fan, P.; Liu, H.T.; Chen, Y.L.; Seth, C.S.; Ge, Q.; Guo, T.C.; et al. TaERFL1a enhances drought resilience through DHAR-mediated ASA-GSH biosynthesis in wheat. Plant Physiol. Bioch. 2025, 220, 109587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, R.; Zhang, X.; Feng, C.; Zhang, S.; Song, L.; Qi, J. Exogenous hydrogen promotes germination and seedling establishment of barley under drought stress by mediating the ASA-GSH cycle and sugar metabolism. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2023, 42, 2749–2762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, C.; Ashraf, M.; Alyemeni, M.N.; Ahmad, P. The role of endogenous nitric oxide in salicylic acid-induced up-regulation of ascorbate-glutathione cycle involved in salinity tolerance of pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) plants. Plant Physiol. Bioch. 2020, 147, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Ou, Y.; Lin, X.; Liu, X.; Sun, C. Novel application of cyclo (-Phe-Pro) in mitigating aluminum toxicity through oxidative stress alleviation in wheat roots. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 363, 125241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, G.; Zhao, X.; Liu, S.; Sun, F.; Zhang, C.; Xi, Y. Beneficial effects of melatonin in overcoming drought stress in wheat seedlings. Plant Physiol. Bioch. 2017, 118, 138–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, G.; Zhao, Y.; Yu, X.; Kiprotich, F.; Han, H.; Guan, R.; Wang, R.; Shen, W. Nitric oxide is required for melatonin-enhanced tolerance against salinity stress in rapeseed (Brassica napus L.) seedlings. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.N.; Mobin, M.; Abbas, Z.K.; Siddiqui, M.H. Nitric oxide-induced synthesis of hydrogen sulfide alleviates osmotic stress in wheat seedlings through sustaining antioxidant enzymes, osmolyte accumulation and cysteine homeostasis. Nitric Oxide 2017, 68, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ren, J.; Yan, X.; Wu, W.; Yang, X.; Dong, Y. Hydrogen Sulfide Is Involved in Melatonin-Induced Drought Tolerance in Maize (Zea mays “Beiqing340”). Agronomy 2025, 15, 2592. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15112592

Ren J, Yan X, Wu W, Yang X, Dong Y. Hydrogen Sulfide Is Involved in Melatonin-Induced Drought Tolerance in Maize (Zea mays “Beiqing340”). Agronomy. 2025; 15(11):2592. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15112592

Chicago/Turabian StyleRen, Jianhong, Xinru Yan, Wenjing Wu, Xiaoxiao Yang, and Yanhui Dong. 2025. "Hydrogen Sulfide Is Involved in Melatonin-Induced Drought Tolerance in Maize (Zea mays “Beiqing340”)" Agronomy 15, no. 11: 2592. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15112592

APA StyleRen, J., Yan, X., Wu, W., Yang, X., & Dong, Y. (2025). Hydrogen Sulfide Is Involved in Melatonin-Induced Drought Tolerance in Maize (Zea mays “Beiqing340”). Agronomy, 15(11), 2592. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15112592