Multi-Omics Dissection of Gene–Metabolite Networks Underlying Lenticel Spot Formation via Cell-Wall Deposition in Pear Peel

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials

2.2. Electron Microscopy Observation

2.3. Lignin, Cellulose and Hemicellulose Content Determination

2.4. Transcriptome Analysis and RNA-Seq Data Validation

2.5. Metabolomics Identification and Statistical Analysis

2.6. RNA Extraction and RT-qPCR

2.7. Bioinformatics and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

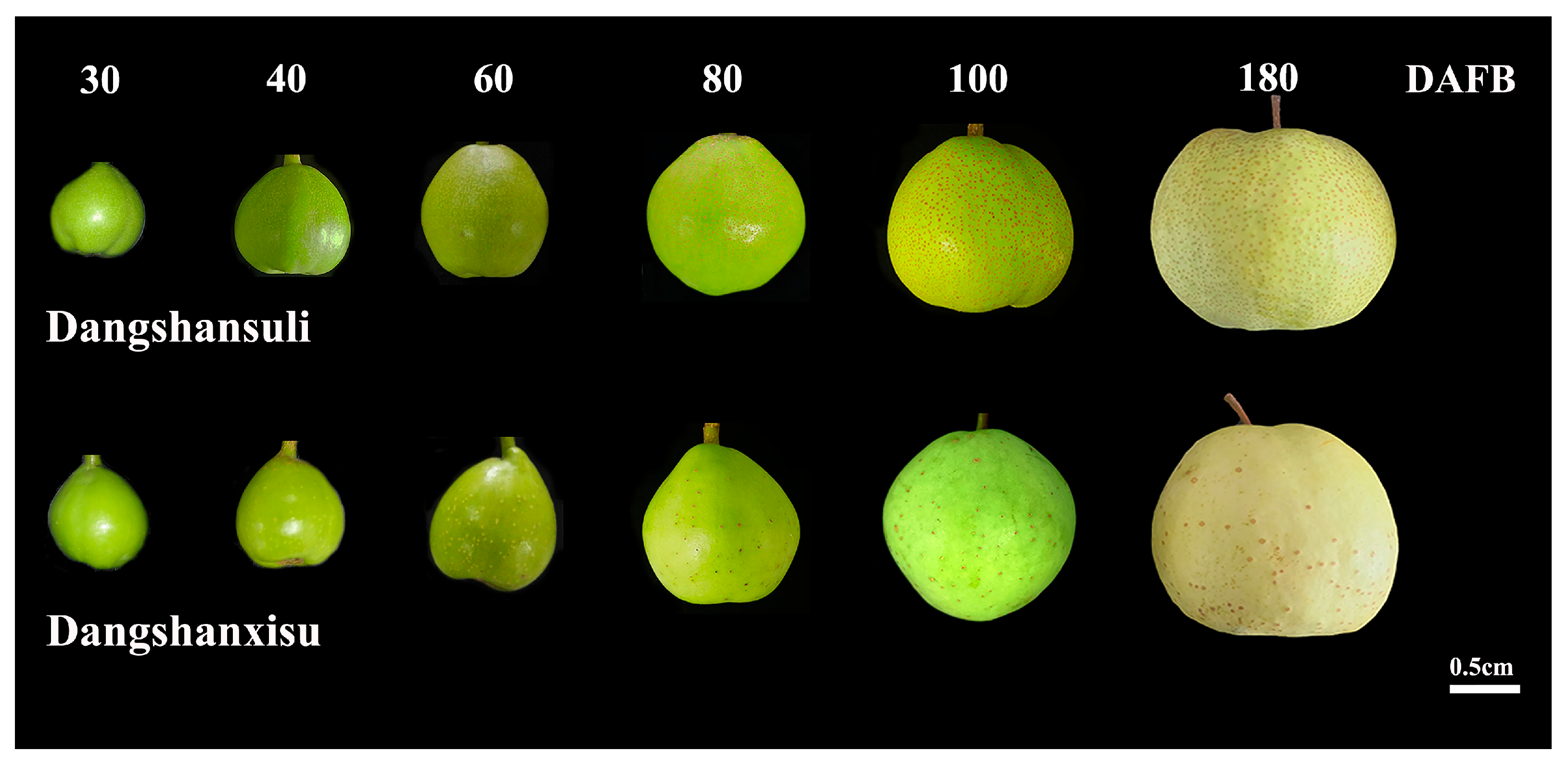

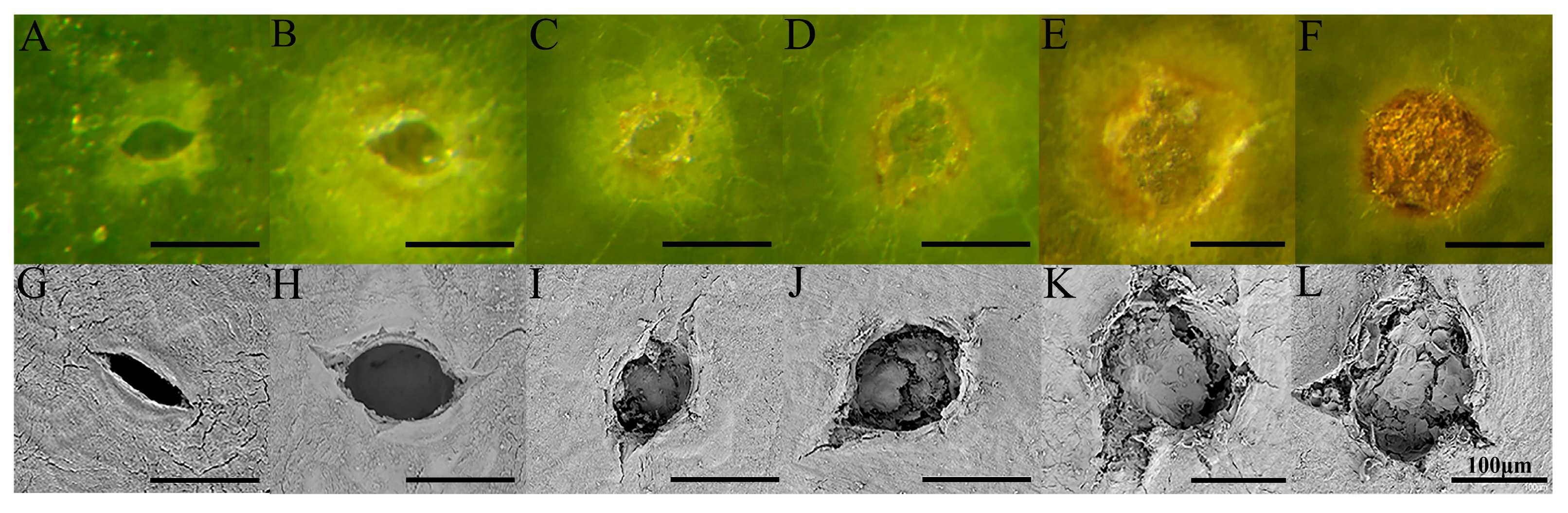

3.1. Development and Formation of Pear Lenticel Spots

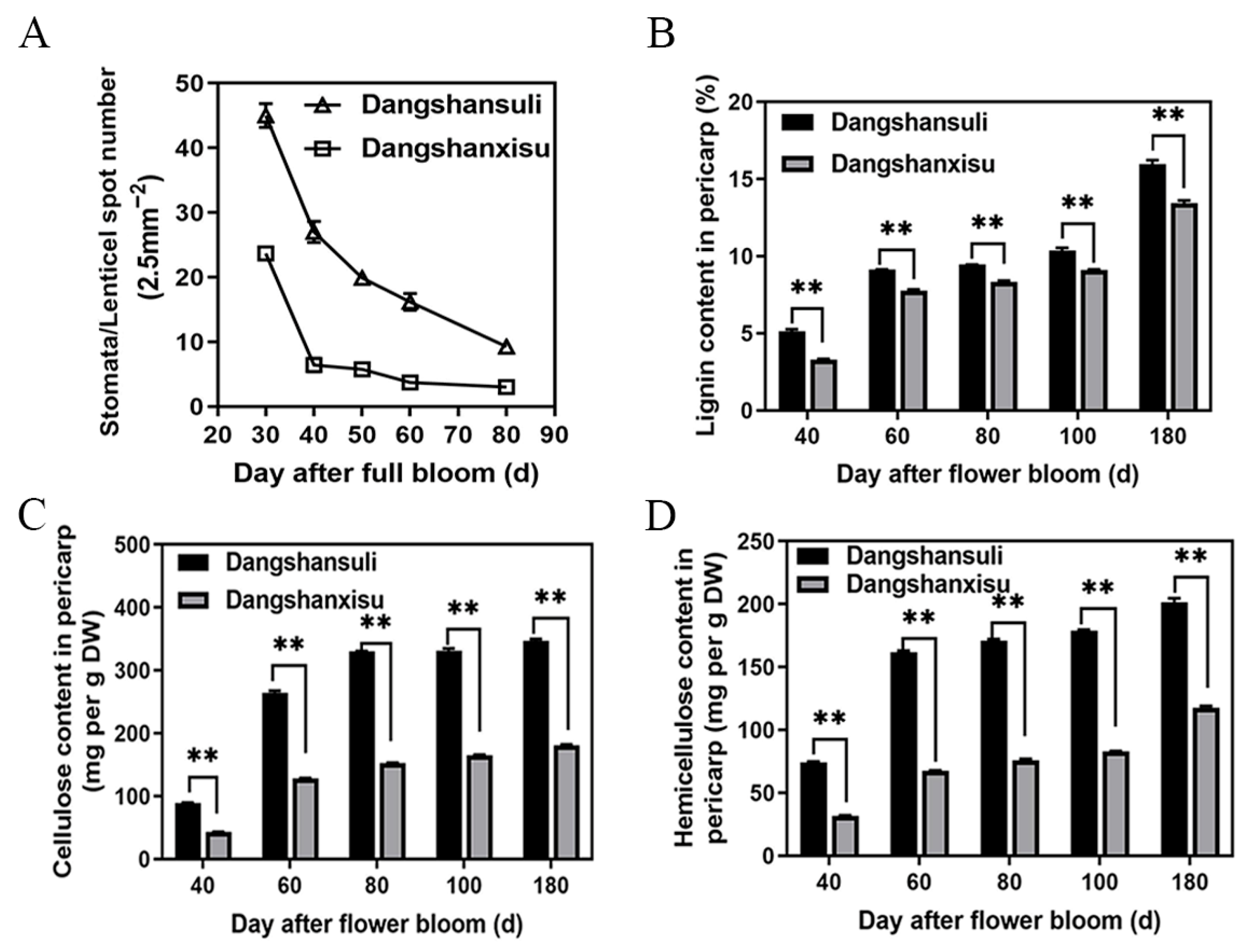

3.2. Lenticel Density and Cell-Wall Composition During Fruit Development

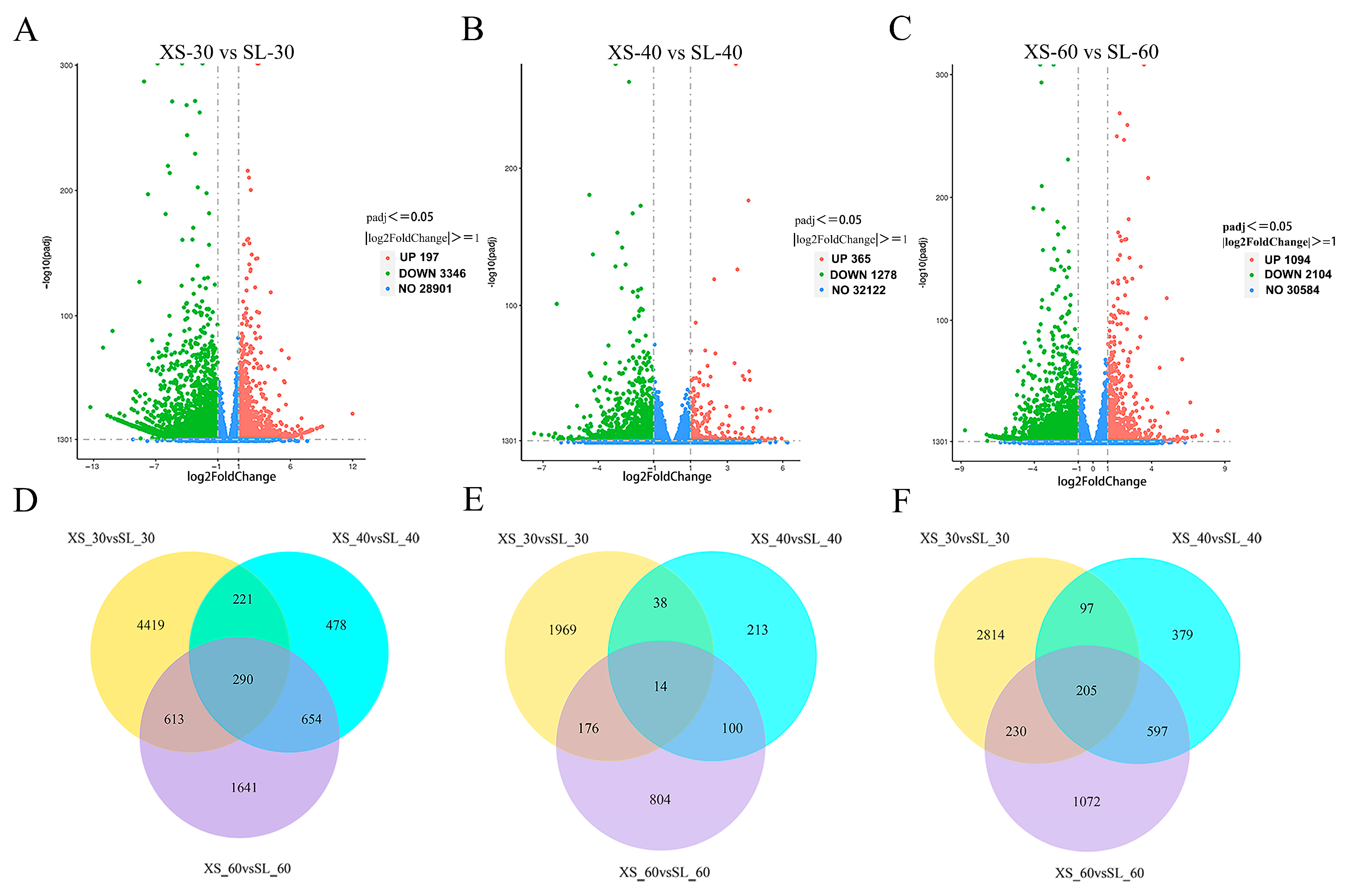

3.3. Overview of RNA Sequencing

3.4. Analysis of Differentially Expressed Genes

3.5. GO and KEGG Enrichment Analysis of DEGs

3.6. Transcription Factors (TFs) Involved in Lenticel Spot Formation

3.7. Comprehensive Analysis of Transcripts and Metabolites Involved in Pear Lenticel Spot Formation

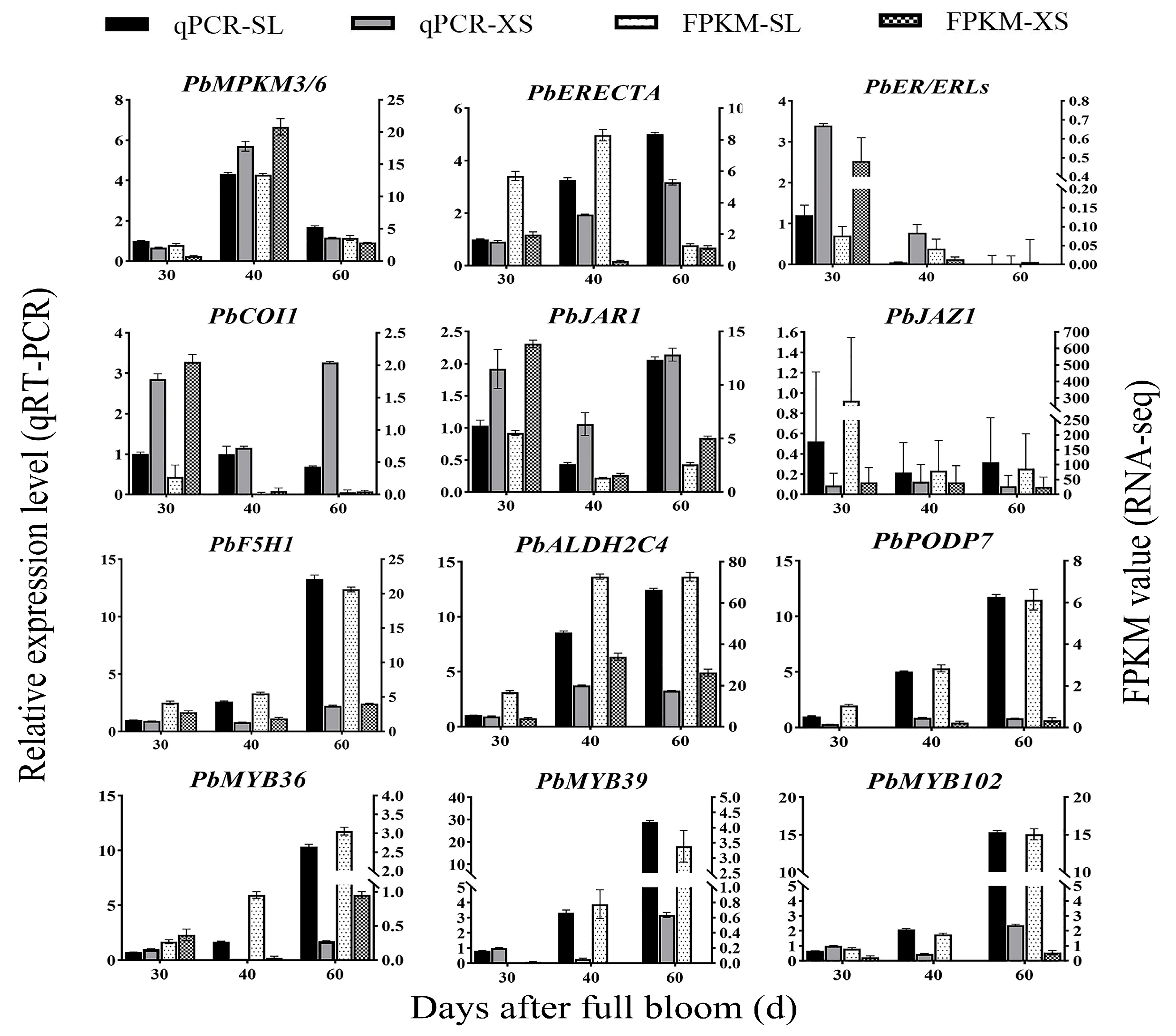

3.8. Comfirmation of Transcriptome Data Using qRT-PCR

4. Discussion

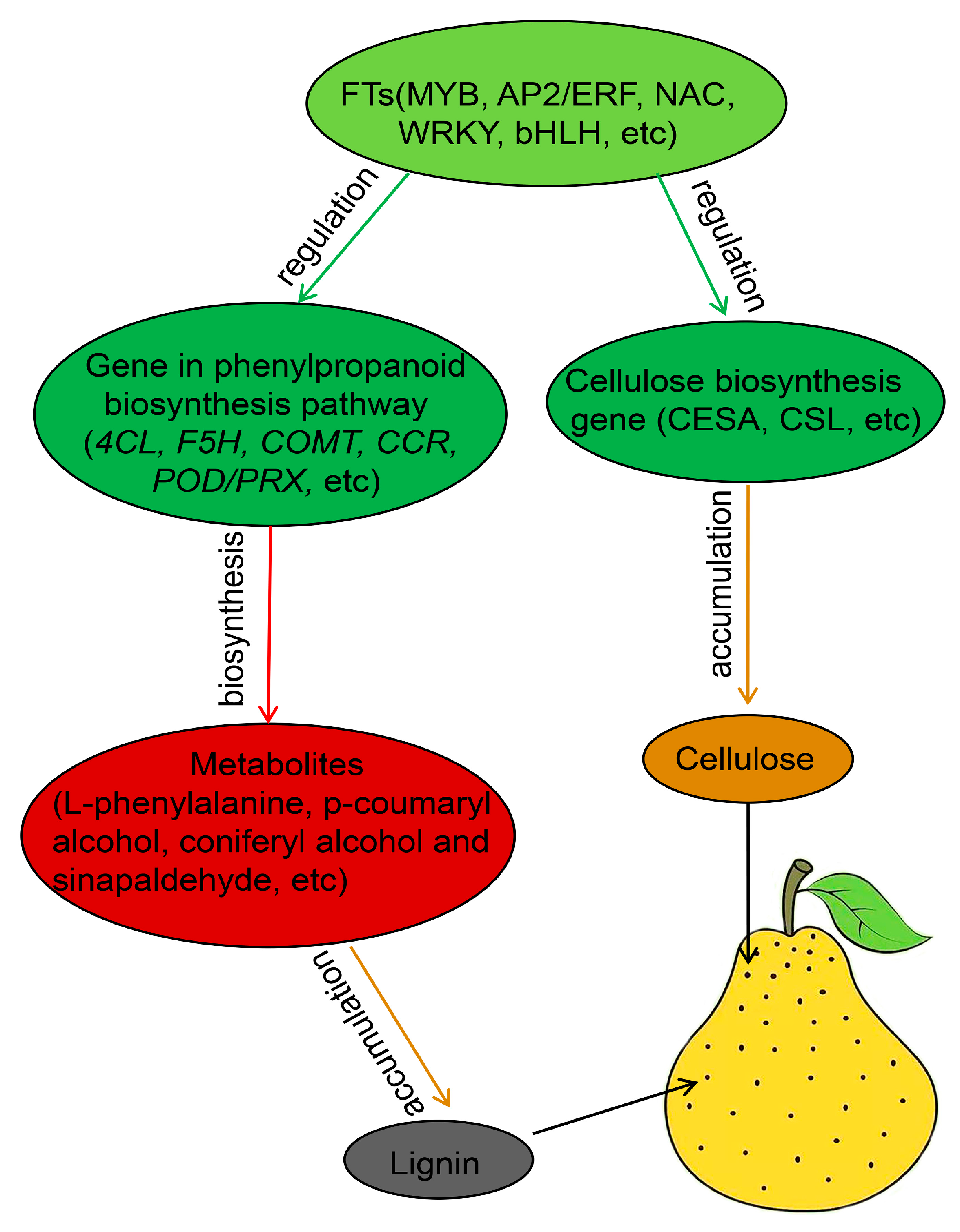

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sheng, J.; Chen, X.; Song, B.; Liu, H.; Li, J.; Wang, R.; Wu, J. Genome-wide identification of the MATE gene family and functional characterization of PbrMATE9 related to anthocyanin in pear. Hortic. Plant J. 2023, 9, 1079–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, R.W.; Zhang, X.Z.; Li, B.; Wang, M.R.; Xie, Y.R.; Li, P.; Wang, L.; Yang, J.; Xue, H.B. Comprehensive evaluation of fruit spots in 296 pear germplasm resources. Acta Hortic. Sin. 2023, 50, 2305–2322. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.L.; Zhang, X.F.; Wang, R.; Bai, Y.X.; Liu, C.L.; Yuan, Y.B.; Yang, Y.J.; Yang, S.L. Differential gene expression analysis of ‘Chili’ (Pyrus bretschneideri) fruit pericarp with two types of bagging treatments. Hortic. Res. 2017, 4, 17005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Jia, X.B. Anatomical observation on the process of pear fruitlet stomata changing to fruit dots. J. Fruit. Sci. 2002, 19, 62–63. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, M.M.; Anwar, R.; Yousef, A.F.; Li, B.; Luvisi, A.; Bellis, L.; Aprile, A.; Chen, F. Influence of bagging on the development and quality of fruits. Plants 2021, 10, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, M.Q.; Li, H.; Xu, K.; Chen, Z.T.; Gao, Y.B. The Effect of bagging on the appearance quality of ‘Huanghua’ pear fruit. South. China Fruit. 2019, 48, 100–106. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, R.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; Wang, L.; Yang, J.; Wang, L.; Wang, S.; Su, Y.; Xue, H. Transcriptome and physiological analysis highlight lignin metabolism of the fruit dots disordering during postharvest cold storage in ‘Danxiahong’ pear. Genes 2023, 14, 1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.J. Deciphering the enigma of lignification: Precursor transport, oxidation, and the topochemistry of lignin assembly. Mol. Plant 2012, 5, 304–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, M.; Smith, R.A.; Samuels, L. The transport of monomers during lignification in plants: Anything goes but how? Curr. Opin. Biotech. 2019, 56, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.H.; Wang, H.; Cheng, X.; Su, X.Q.; Zhao, Y.; Jiang, T.S.; Jin, Q.; Lin, Y.; Cai, Y.P. Comparative genomic analysis of the PAL genes in five Rosaceae species and functional identification of Chinese white pear. PeerJ 2019, 7, e8064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Cheng, Y.D.; Dong, Y.; Shang, Z.L.; Guan, J.F. Effects of low temperature conditioning on fruit quality and peel browning spot in ‘Huangguan’ pears during cold storage. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2017, 131, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, G.Y.; Peng, D.; Yu, Z.Q.; Chen, X.L.; Cheng, X.R.; Yang, Y.Z.; Ye, T.; Lv, Q.; Ji, W.J.; Deng, X.W.; et al. Advances in the role of auxin for transcriptional regulation of lignin biosynthesis. Funct. Plant Biol. 2021, 48, 743–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.L.; Zhang, X.N.; Lu, G.L.; Wang, C.R.; Wang, R. Regulation of gibberellin on gene expressions related with the lignin biosynthesis in ‘Wangkumbae’ pear (Pyrus pyrifolia Nakai) fruit. Plant Growth Regul. 2015, 76, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Lyu, K.; Zeng, S.; Wang, X.; Chen, X. A Combined metabolome and transcriptome reveals the lignin metabolic pathway during the developmental stages of peel coloration in the ‘Xinyu’ pear. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, X.; Li, M.L.; Li, D.H.; Zhang, J.Y.; Jin, L.; Sheng, L.L.; Cai, Y.P.; Lin, Y. Characterization and analysis of CCR and CAD gene families at the whole-genome level for lignin synthesis of stone cells in pear (Pyrus bretschneideri) Fruit. Biol. Open 2017, 6, 1602–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.Y.; Wang, Q.; Wang, Y.J.; Wang, M.C.; Liu, Y.P.; Hu, H.J.; Ja, B.; Ye, Z.F.; Liu, L.; Tang, X.M.; et al. Multi-omics analysis of green and russet skin pear cultivars identify key regulators of skin russeting. Sci. Hortic. 2023, 318, 112116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, R.; Zhang, C.; Guo, X.; Li, H.; Lu, H. MYB transcription factors and its regulation in secondary cell wall formation and lignin biosynthesis during xylem development. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Han, Y.; Li, D.; Lin, Y.; Cai, Y. Transcription factors in Chinese pear (Pyrus bretschneideri Rehd.): Genome-wide identification, classification, and expression profiling during fruit development. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Lam, P.Y.; Lee, M.H.; Jeon, H.S.; Tobimatsu, Y.; Park, O.K. The Arabidopsis R2R3-MYB transcription factor MYB15 is a key regulator of lignin biosynthesis in effector-triggered immunity. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 583153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Q.; Chen, W.Y.; Zhang, H.; Liu, P.; Zhang, Y.X. PbrMYB14 Enhances Pear Resistance to Alternaria alternata by Regulating Genes in Lignin and Salicylic Acid Biosynthesis Pathways. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, P.; Zhang, S.; Liu, J.Y.; Zhao, C.H.; Wu, J.; Cao, Y.P.; Fu, C.X.; Han, X.; He, H.; Zhao, Q. MYB20, MYB42, MYB43, and MYB85 regulate phenylalanine and lignin biosynthesis during secondary cell wall formation. Plant Physiol. 2020, 182, 1272–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.H.; Cho, J.S.; Bae, E.K.; Choi, Y.I.; Eom, S.H.; Lim, Y.J.; Lee, H.; Park, E.J.; Ko, J.H. PtrMYB120 functions as a positive regulator of both anthocyanin and lignin biosynthetic pathway in a hybrid poplar. Tree Physiol. 2021, 41, 2409–2423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, C.; Sheng, L.P.; Dong, X.P.; Wang, Y.J.; Zhang, Y.; Song, A.P.; Jiang, J.F.; Guan, Z.Y.; Fang, W.M.; Chen, F.D.; et al. Overexpression of CmMYB15 provides chrysanthemum resistance to aphids by regulating the biosynthesis of lignin. Hortic. Res. 2019, 6, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Guerriero, G.; Berni, R.; Sergeant, K.; Guignard, C.; Lenouvel, A.; Hausman, J.F.; Legay, S. MdMYB52 regulates lignin biosynthesis upon the suberization process in apple. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1039014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, Y.S.; Shan, Y.F.; Yao, J.L.; Wang, R.Z.; Xu, S.Z.; Liu, D.L.; Ye, Z.C.; Lin, J.; Li, X.G.; Xue, C.; et al. The transcription factor PbrMYB24 regulates lignin and cellulose biosynthesis in stone cells of pear fruits. Plant Physiol. 2023, 192, 1997–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, J.; Luo, L.; Zhong, Y.; Sun, J.; Umezawa, T.; Li, L. Phosphorylation of LTF1, an MYB transcription factor in populus, acts as a sensory switch regulating lignin biosynthesis in wood cells. Mol. Plant 2019, 12, 1325–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, Y.J.; Feng, X.F.; Hong, J.Y.; Manzoor, M.A.; Zhou, X.Y.; Zhou, Q.F.; Cai, Y.P. Transcription factor PbMYB80 regulates lignification of stone cells and undergoes RING finger protein PbRHY1-mediated degradation in pear fruit. J. Exp. Bot. 2023, 75, 833–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vroemen, C.W.; Mordhorst, A.P.; Albrecht, C.; Kwaaitaal, M.A.; deVries, S.C. The CUP-SHAPED COTYLEDON3 gene is required for boundary and shoots meristem formation in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2003, 15, 1563–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, R.Q.; Ye, Z.H. Regulation of cell wall biosynthesis. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2007, 10, 564–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, R.Q.; Ye, Z.H. Transcriptional regulation of lignin biosynthesis. Plant Signal. Behav. 2009, 4, 1028–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.J.; Li, X.; Yin, X.R.; Grierson, D.; Chen, K.S. EjNAC3 transcriptionally regulates chilling-induced lignification of loquat fruit via physical interaction with an atypical CAD-like gene. J. Exp. Bot. 2017, 68, 5129–5136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Jiang, C.; Jiang, R.; Wang, F.; Zhang, Z.; Zeng, J. A novel NAC transcription factor from Eucalyptus, EgNAC141, positively regulates lignin biosynthesis and increases lignin deposition. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 642090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.T.; Cheng, C.X.; Zhang, X.F.; Zhou, S.P.; Wang, C.H.; Ma, C.H.; Yang, S.L. PpNAC187 enhances lignin synthesis in ‘Whangkeumbae’ pear (Pyrus pyrifolia) ‘Hard-End’ Fruit. Molecules 2019, 24, 4338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahala, J.; Felten, J.; Love, J.; Gorzsas, A.; Gerber, L.; Lamminmaki, A.; Kangasjarvi, J.; Sundberg, B. A genome-wide screen for ethylene-induced Ethylene Response Factors (ERFs) in hybrid aspen stem identifies ERF genes that modify stem growth and wood properties. New Phytol. 2013, 200, 511–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambavaram, M.M.R.; Krishnan, A.; Trijatmiko, K.R.; Pereira, A. Coordinated activation of cellulose and repression of lignin biosynthesis pathways in rice. Plant Physiol. 2011, 155, 916–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Cheng, C.; Qi, Q.; Zhou, S.; Wang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, C.; Wang, Y.; Dang, R.; Yang, S. PpERF1b-like enhances lignin synthesis in pear (Pyrus pyrifolia) ‘hard-end’ fruit. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1087388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahiwal, S.; Pahuja, S.; Pandey, G.K. Review: Structural-functional relationship of WRKY transcription factors: Unfolding the role of WRKY in plants. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 257, 128769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Yu, X.; Chen, W.P.; Zhuang, W.B.; Wang, S.H.; Sun, C.; Cao, L.F.; Zhou, T.T.; Qu, S.C. MdWRKY75e enhances resistance to Alternaria alternata in Malus domestica. Hortic. Res. 2021, 8, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.Y.; Shen, X.X.; Ding, Y.; Li, Y.K.; Liu, S.Y.; Yang, Y.; Ding, Y.D.; Guan, C.F. DkWRKY transcription factors enhance persimmon resistance to Colletotrichum horii by promoting lignin accumulation through DkCAD1 promotor interaction. Stress Biol. 2024, 4, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.L.; Wang, D.; Zhao, M.R.; Yu, M.Y.; Zheng, X.D.; Tian, Y.K.; Sun, Z.J.; Liu, X.L.; Wang, C.H.; Ma, C.Q. A transcription factor, PbWRKY24, contributes to russet skin formation in pear fruits by modulating lignin accumulation. Hortic. Res. 2025, 12, uhae300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.Q.; Ding, L.; Liu, J.Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, S.; Zhao, K.K.; Guan, Y.X.; Song, A.P.; Wang, H.B.; Chen, S.M.; et al. Regulation of lignin biosynthesis by an atypical bHLH protein CmHLB in Chrysanthemum. J. Exp. Bot. 2022, 73, 2403–2419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Li, S.J.; Liu, X.F.; Yin, X.R.; Grierson, D.; Chen, K.S. Ternary complex EjbHLH1-EjMYB2-EjAP2-1 retards low temperature-induced flesh lignification in loquat fruit. Plant Physiol. Bioch. 2019, 139, 731–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Acker, R.; Vanholme, R.; Storme, V.; Mortimer, J.C.; Dupree, P.; Boerjan, W. Lignin biosynthesis perturbations affect secondary cell wall composition and saccharification yield in Arabidopsis thaliana. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2013, 6, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svinterikos, E.; Kormányos, A.; Zuburtikudis, I.; Al-Marzouqi, M. Activated carbon nanofibers from lignin/recycled-PET and their adsorption capacity of refractory sulfur compounds from fossil fuels. Energy Procedia 2019, 161, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.Z.; Xue, Y.S.; Fan, J.; Yao, J.L.; Qin, M.F.; Lin, T.; Lian, Q.; Zhang, M.Y.; Li, X.L.; Li, J.M.; et al. A systems genetics approach reveals PbrNSC as a regulator of lignin and cellulose biosynthesis in stone cells of pear fruit. Genome Biol. 2021, 22, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yusuf, A.O.; Möllers, C. Inheritance of cellulose, hemicellulose and lignin content in relation to seed oil and protein content in oil seed rape. Euphytica 2024, 220, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortazavi, A.; Williams, B.A.; McCue, K.; Schaeffer, L.; Wold, B. Mapping and quantifying mammalian transcriptomes by RNA-Seq. Nat. Methods 2008, 5, 621–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anders, S.; Pyl, P.T.; Huber, W. HTSeq-a python framework to work with high-through put sequencing data. Bioinformatics 2014, 31, 166–169. [Google Scholar]

- Trapnell, C.; Williams, B.A.; Pertea, G.; Mortazavi, A.; Kwan, G.; van Baren, M.J.; Salzberg, S.L.; Wold, B.J.; Pachter, L. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat. Biotechnol. 2010, 28, 511–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, M.D.; Wakefield, M.J.; Smyth, G.K.; Oshlack, A. Gene ontology analysis for RNA-seq: Accounting for selection bias. Genome Biol. 2010, 11, R14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.R.; Zhou, J.H.; Deng, L.Z.; Zhang, S.Q.; Golding, J.B.; Wang, B.G. Transcriptomics Integrated with Metabolomics Analysis of Cold-induced Lenticel Disorder via the Lignin Pathway upon Postharvest ‘Xinli No.7’ Pear Fruit. Postharvest Biol. Tec. 2025, 220, 113315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y.Q.; Qin, X.L.; Pei, Y.; Li, X.L.; Feng, Y.X.; Wei, C.Q.; Cheng, Y.D.; Guan, J.F. Effect of exogenous chlorogenic acid on fruit dot formation and expression of related genes in ‘Xuehua’ pear (Pyrus bretschneideri). J. Agric. Biotech. 2021, 29, 258–267. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, Y.; Qin, X.; Wei, C.; Feng, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Guan, J. Influence of bagging on fruit quality, incidence of peel browning spots, and lignin content of ‘Huangguan’ pears. Plants 2024, 13, 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Sun, H.L.; Cheng, Z.Y.; Jia, B.; Liu, P.; Ye, Z.F.; Zhu, L.W.; Heng, W. Cloning and expression of enzyme genes related to lignin biosynthesis in the pericarp of russet mutant of Dangshansuli. Acta Agric. Boreali Sin. 2013, 28, 88–92. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, W.L.; Li, X.G.; Yang, Q.S.; Lin, J.; Sheng, B.L.; Chang, Y.H.; Wang, H. Comparative metabolic and transcriptomic analysis of the pericarp of Sucui 1, Cuiguan and Huasu pears. J. Fruit Sci. 2022, 39, 1989–2006. [Google Scholar]

- O’Malley, D.M.; Whetten, R.W.; Bao, W.; Chen, C.L.; Sederoff, R.R. The role of laccase in lignification. Plant J. 1993, 4, 751–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanholme, R.; Ralph, J.; Akiyama, T.; Lu, F.; Pazo, J.R.; Kim, H.; Christensen, J.H.; Brecht, V.R.; Storme, V.; Rycke, R.D.; et al. Engineering traditional monolignols out of lignin by concomitant up-regulation of F5H1 and down-regulation of COMT in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2010, 64, 885–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sipahi, H.; Haiden, S.; Berkowitz, G. Genome-wide analysis of cellulose synthase (CesA) and cellulose synthase-like (Csl) proteins in Cannabis sativa L. PeerJ 2024, 12, e17821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Wen, L.; Chen, J.; Pan, G.; Wu, Z.; Li, Z.; Xiao, Q.; Wang, Y.; Qiu, C.; Long, S.; et al. Comparative transcriptomic analysis identifies key cellulose synthase genes (CESA) and cellulose synthase-like genes (CSL) in fast growth period of flax stem (Linum usitatissimum L.). J. Nat. Fibers 2022, 19, 10431–10446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, N.G.; Howells, R.M.; Huttly, A.K.; Vickers, K.; Turner, S.R. Interactions among three distinct CesA proteins essential for cellulose synthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 1450–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Xue, C.; Li, J.; Qiao, X.; Li, L.; Yu, L.; Huang, Y.; Wu, J. Genome-wide identification, evolution and functional divergence of MYB transcription factors in Chinese white pear (Pyrus bretschneideri). Plant Cell Physiol. 2016, 57, 824–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.S.; Wang, Y.C.; Jiang, H.Y.; Liu, W.J.; Zhang, S.H.; Hou, X.K.; Zhang, S.S.; Wang, N.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, Z.Y.; et al. Transcriptome analysis reveals that PbMYB61 and PbMYB308 are involved in the regulation of lignin biosynthesis in pear fruit stone cells. Plant J. 2023, 116, 217–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.L.; Xue, Y.S.; Wang, R.Z.; Song, B.B.; Xue, C.; Shan, Y.F.; Xue, Z.L.; Wu, J. PbrMYB4, a R2R3-MYB Protein, Regulates Pear Stone Cell Lignification through Activation of Lignin Biosynthesis Genes. Hortic. Plant J. 2024, 11, 105–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.Z.; Sun, M.Y.; Yao, J.L.; Liu, X.X.; Xue, Y.S.; Yang, G.Y.; Zhu, R.X.; Jiang, W.T.; Wang, R.Z.; Xue, C.; et al. Auxin inhibits lignin and cellulose biosynthesis in stone cells of pear fruit via the PbrARF13-PbrNSC-PbrMYB132 transcriptional regulatory cascade. Plant Biotech. J. 2023, 21, 1408–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Yoo, C.G.; Rottmann, W.; Winkeler, K.A.; Collins, C.M.; Gunter, L.E.; Jawdy, S.S.; Yang, X.H.; Pu, Y.Q.; Ragauskas, A.J.; et al. PdWND3A, a wood-associated NAC domain-containing protein, affects lignin biosynthesis and composition in Populus. BMC Plant Biol. 2019, 19, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Gao, S.Y.; Yin, M.X.; Xu, M.Y.; Wang, T.Y.; Li, X.Y.; Du, G.D. A Ca2+-induced PuNAC21–PuDof2.5–PuPRX42-like/PuCCoAOMT1 Module Represses Lignin Biosynthesis in Pear Fruit. Hort. Res. 2025, 12, uhaf102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.B.; Wang, S.G.; Zhang, B.C.; Shang-Guan, K.K.; Shi, Y.Y.; Zhang, D.M.; Liu, X.L.; Wu, K.; Xu, Z.P.; Fu, X.D.; et al. A gibberellin-mediated DELLA-NAC signaling cascade regulates cellulose synthesis in rice. Plant Cell 2015, 27, 1681–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Qi, K.J.; Zhao, L.Y.; Xie, Z.H.; Pan, J.H.; Yan, X.; Shiratake, K.; Zhang, S.L.; Tao, S.T. PbAGL7–PbNAC47–PbMYB73 Complex Coordinately Regulates PbC3H1 and PbHCT17 to Promote the Lignin Biosynthesis in Stone Cells of Pear Fruit. Plant J. 2024, 120, 1933–1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.W.; Wang, Q.; Wang, D.; Guo, W.; Hu, M.X.; Liu, Y.L.; Zhou, G.K.; Chai, G.H.; Zhao, S.T.; Lu, M.Z. PagERF81 regulates lignin biosynthesis and xylem cell differentiation in poplar. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2023, 65, 1134–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.H.; Fan, G.F.; Jiang, J.H.; Yao, W.J.; Zhang, X.M.; Zhao, K.; Zhou, B.R.; Jiang, T.B. Transcription factor PagERF110 inhibits xylem differentiation by direct regulating PagXND1d in poplar. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2024, 215, 118622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yin, X.R.; Li, H.; Xu, M.; Zhang, M.X.; Li, S.J.; Liu, X.F.; Shi, Y.N.; Grierson, D.; Chen, K.S. ETHYLENE RESPONSE FACTOR39-MYB8 complex regulates low-temperature-induced lignification of loquat fruit. J. Exp. Bot. 2020, 71, 3172–3184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, M.Y.; He, S.; Zhang, H.; Gao, S.Y.; Yin, M.X.; Li, X.Y.; Du, G.D. Gibberellin Regulates the Synthesis of Stone Cells in ‘Nanguo’ Pear via the PuMYB91-PuERF023 Module. Physiol. Plant. 2025, 177, e70074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Q.; Xiao, S.; Wang, X.; Ao, C.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, L. GhWRKY1-like enhances cotton resistance to Verticillium Dahliae via an increase in defense-induced lignification and S monolignol content. Plant Sci. 2021, 305, 110833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shun, X.J.; Zhang, F.B.; Song, H.D.; Liang, K.L.; Wang, J.X.; Zhang, X.Y.; Wang, X.W.; Yang, J.G.; Han, W.H. Genome-wide analysis of the WRKY family in Nicotiana benthamiana reveals key members regulating lignin synthesis and Bemisia tabaci resistance. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2024, 222, 119655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.Y.; Zhang, X.F.; Jiang, F.; Zhang, H.; Yan, N.; Li, X.Y.; Du, G.D. The PuWRKY29-PuMYB62 Module Responds to Salicylic Acid to Inhibit the Synthesis of Stone Cells in ‘Nanguo’ Pear. Plant Physiol. Bioch. 2025, 228, 110238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Xu, C.H.; Kang, Y.L.; Gu, T.W.; Wang, D.X.; Zhao, S.Y.; Xia, G.M. The heterologous expression in Arabidopsis thaliana of sorghum transcription factor SbbHLH1 downregulates lignin synthesis. J. Exp. Bot. 2013, 64, 3021–3032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ma, N.; Xiao, Z.; Lu, L.; Zhang, H.; Liu, C.; Xu, Y.; Qi, Y.; Gao, Z. Multi-Omics Dissection of Gene–Metabolite Networks Underlying Lenticel Spot Formation via Cell-Wall Deposition in Pear Peel. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2564. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15112564

Ma N, Xiao Z, Lu L, Zhang H, Liu C, Xu Y, Qi Y, Gao Z. Multi-Omics Dissection of Gene–Metabolite Networks Underlying Lenticel Spot Formation via Cell-Wall Deposition in Pear Peel. Agronomy. 2025; 15(11):2564. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15112564

Chicago/Turabian StyleMa, Na, Ziwen Xiao, Liqing Lu, Haiqi Zhang, Chunyan Liu, Yiliu Xu, Yongjie Qi, and Zhenghui Gao. 2025. "Multi-Omics Dissection of Gene–Metabolite Networks Underlying Lenticel Spot Formation via Cell-Wall Deposition in Pear Peel" Agronomy 15, no. 11: 2564. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15112564

APA StyleMa, N., Xiao, Z., Lu, L., Zhang, H., Liu, C., Xu, Y., Qi, Y., & Gao, Z. (2025). Multi-Omics Dissection of Gene–Metabolite Networks Underlying Lenticel Spot Formation via Cell-Wall Deposition in Pear Peel. Agronomy, 15(11), 2564. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15112564