Calibration and Testing of Discrete Element Simulation Parameters for the Presoaked Cyperus esculentus L. Rubber Interface Using EDEM

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- The response of C. esculentus seed germination characteristics to different soaking durations was analyzed. By conducting comparative experiments with varying soaking times and a non-soaked control group and integrating germination indicators with root and shoot growth traits, the optimal soaking time for promoting germination and growth was determined.

- (2)

- Key interaction parameters between soaked C. esculentus seeds and rubber materials were systematically calibrated. Using Plackett Burman design, the steepest ascent test, and Box Behnken response surface methodology, the contact parameters at the seed–rubber interface were obtained and their optimal combination was identified, filling the research gap in parameters for soaked seed–rubber material interactions.

- (3)

- A dynamic stacking angle test platform was established. Using the physical dynamic stacking angle as a benchmark, the optimized parameter set was applied in discrete element simulations for comparative validation. The results showed good agreement between simulation and experimental outcomes, confirming the validity of the model and providing a reliable simulation tool and parametric basis for the design of precision seed metering devices for soaked C. esculentus.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. A Study on the Response of C. esculentus Seed Germination Characteristics to Different Soaking Durations

Soaking Experiment: Materials and Methods Design

2.2. Model Establishment

Physical Model of C. esculentus Seeds

2.3. Determination of Contact Parameters for C. esculentus Seeds

2.3.1. Measurement of Static and Dynamic Friction Coefficients

2.3.2. Coefficient of Restitution

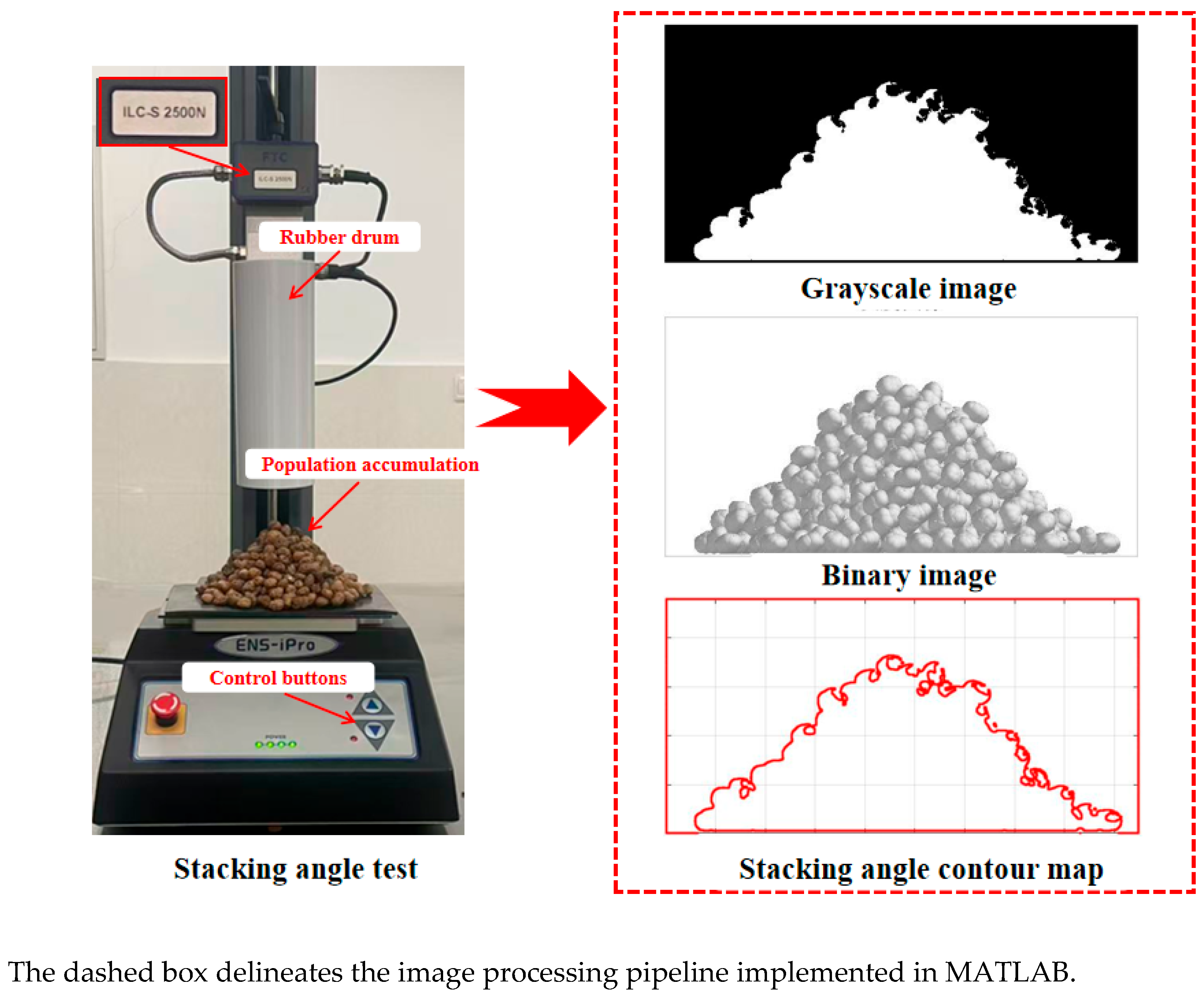

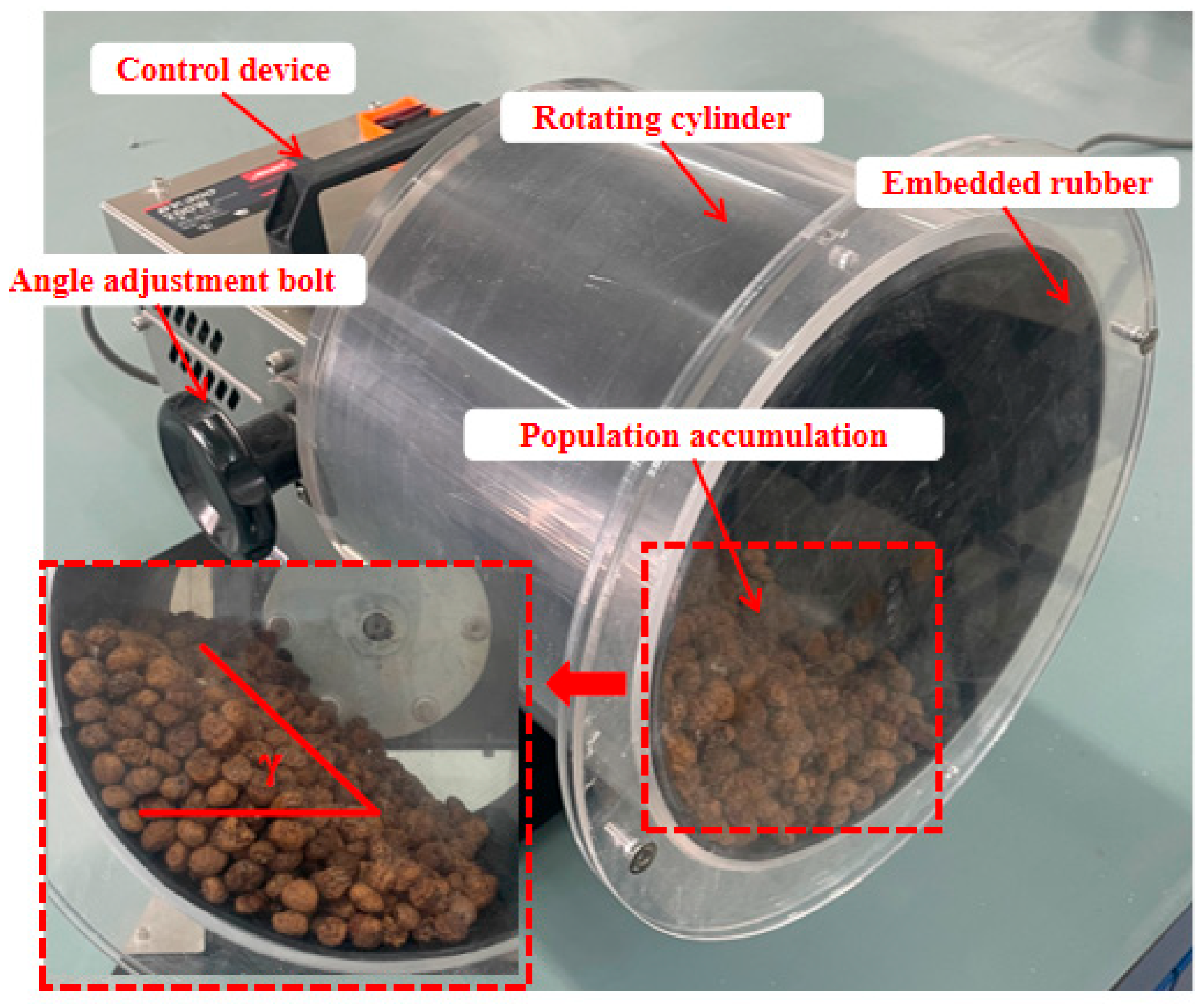

2.4. Stacking Angle Test

2.4.1. Physical Stacking Angle Measurement

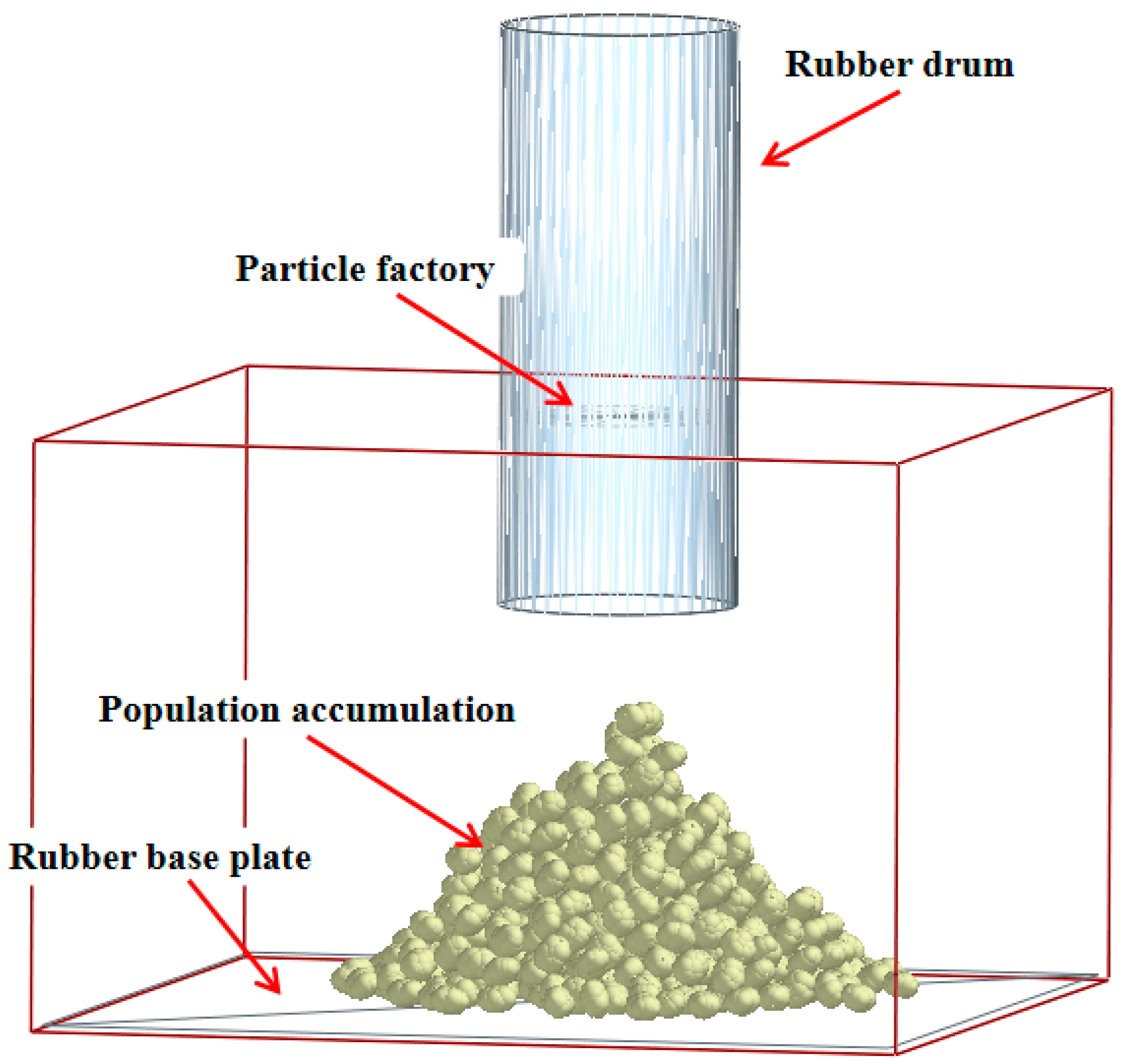

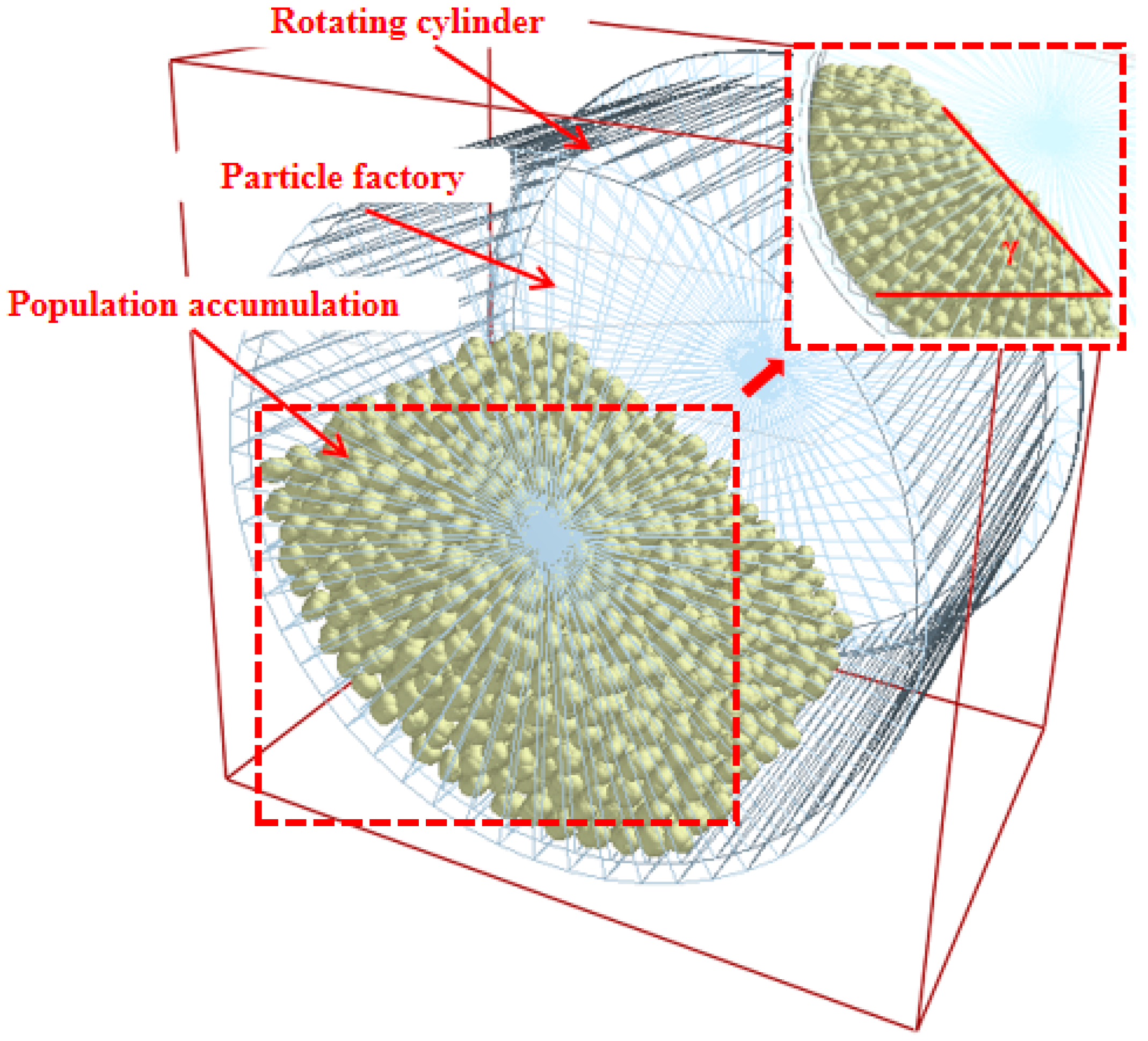

2.4.2. Simulated Stacking Angle Measurement

2.5. Plackett Burman Experimental Design

2.6. Steepest Ascent Experiment Design

2.7. Box Behnken Experimental Design

2.8. Validation Experiment Design

3. Results

3.1. Comprehensive Analysis of Germination Indicators of C. esculentus Under Different Soaking Durations

3.2. Effects of Different Soaking Treatments on Root and Shoot Traits of C. esculentus After Development

3.3. Pot Experiment in Illuminated Growth Chamber

3.4. Analysis of Plackett Burman Test Results for the Stacking Angle

3.5. Analysis of Steepest Ascent Test Results

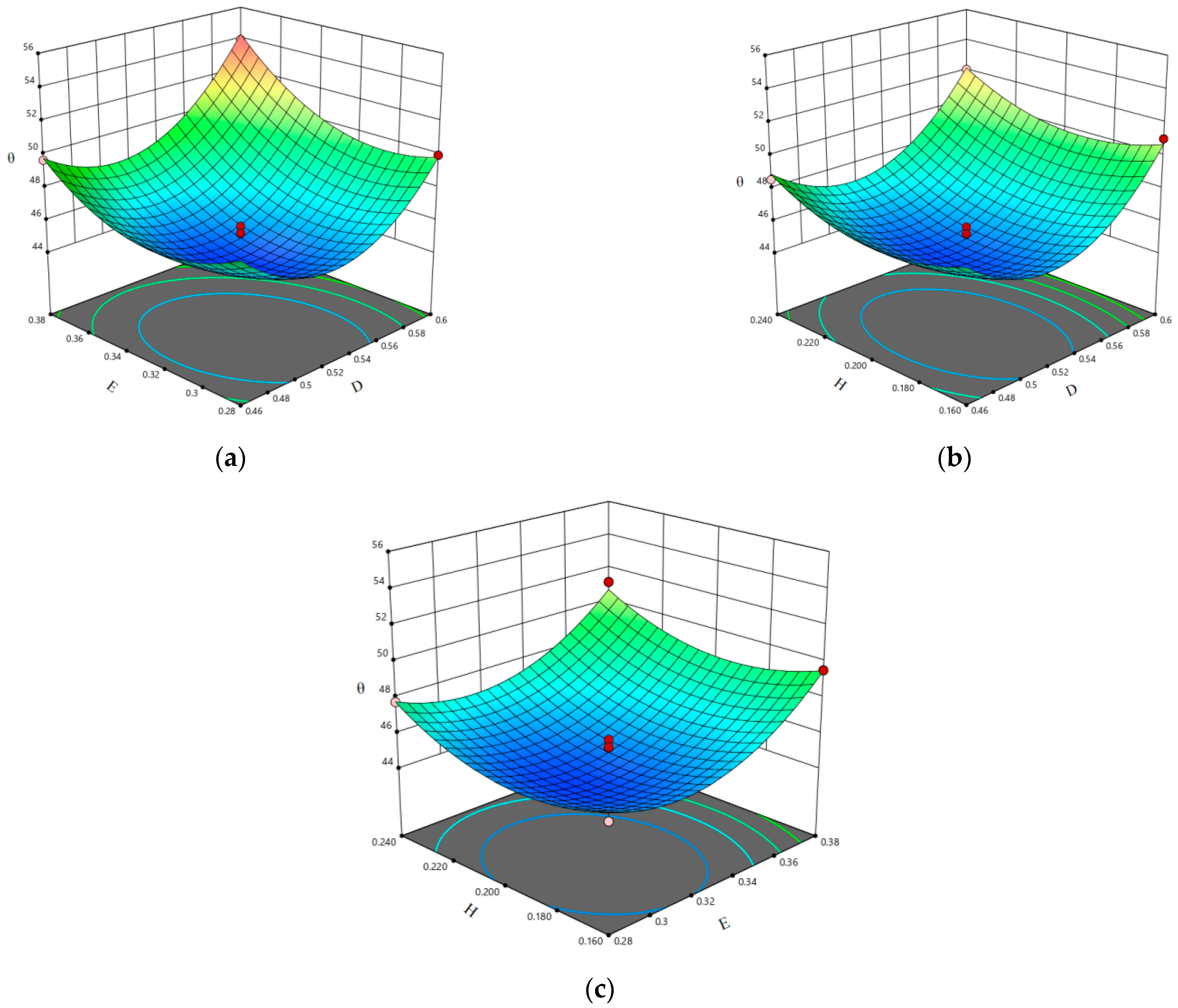

3.6. Analysis of Box Behnken Test Results

3.7. Determination of the Optimal Parameter Combination

3.8. Analysis of Validation Test Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Calibration Differences in Seeds Before and After Soaking

4.2. Seeding Optimization for Other Seeds

4.3. Optimization of Seeding Performance Using Rubber Suction Holes

4.4. Research Limitations and Breakthrough Pathways in Tiger Nut Seeding

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Four soaking time gradients (0, 24, 48, and 72 h) were set to determine the optimal soaking time for C. esculentus seeds. One-way ANOVA indicated that soaking time had a significant effect (p = 0.05) on seed germination and root-shoot traits. The 48 h treatment showed the highest values across all indicators, while longer soaking times led to a decline in germination metrics, reflecting an inhibitory effect. Pot experiments further confirmed that the 48 h soaking treatment resulted in the highest seedling emergence rate, identifying it as the optimal soaking duration.

- (2)

- Physical tests were conducted on pre-soaked C. esculentus seeds, measuring a coefficient of restitution of 0.54 against rubber, along with static and rolling friction coefficients of 0.26 and 0.21, respectively.

- (3)

- Plackett Burman design was employed to screen significant parameters affecting the stacking angle. The results showed that the static friction coefficient between seeds (D) and the rolling friction coefficient between seeds (E) had extremely significant effects, while the rolling friction coefficient between seeds and rubber (H) was significant. The steepest ascent experiment was used to approach the optimal region of these significant parameters.

- (4)

- A second-order regression model for the relative error of the stacking angle was developed using Box Behnken design. With the objective of minimizing the deviation from the physical stacking angle, the optimal parameter combination was determined as follows: static friction coefficient between seeds (D) = 0.592, rolling friction coefficient between seeds (E) = 0.325, and rolling friction coefficient between seeds and rubber (H) = 0.171. Validation through dynamic stacking angle tests yielded a physical value of 48.13° and a simulated value of 47.25°, with a relative error of 1.96%, indicating good agreement with physical experiments and confirming the reliability of the optimal parameter set. The calibrated discrete element parameters can provide reference for the design of precision seed metering devices for C. esculentus.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhou, Q.; Liu, Y.; Liu, L.; Tian, Z.; He, Y. Genome-Wide Identification and Expression Analysis of the GRF Gene Family in C. esculentus. Southwest China J. Agric. Sci. 2025, 38, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Hu, X.; Liu, P.; Bai, C.; Liu, G. Research Progresses on Cultivation and Utilization of Cyperus esculentus. Chin. J. Trop. Agric. 2017, 37, 56–60. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, R.Y.; Wang, X.S.; Xiang, H. An Emerging Multipurpose Oil-Bearing Crop: Tiger Nut (Cyperus esculentus). China Oils Fats 2019, 44, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, C. Research status and prospect of seeding technology for cyperus. China Agric. Mach. Equip. 2025, 8, 123–125. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Tiger Nut Achieved a Record Yield of 858 kg per Mu in Henan Province. J. Seed Ind. Guide 2019, 33. (In Chinese)

- Yan, F.; Zhu, W. Research status and prospect of Cyperus esculentus. Grain Oil Sci. Technol. 2020, 33, 4–6. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Xue, Z.; Liu, X.; Meng, W.; Zhang, J.; Chen, G.; Nan, J.; Zhong, P. Research Progress on Nutritional Components and Biological Functions of Cyperus esculentus and Its Application. Feed Ind. 2025, 46, 56–60. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turck, D.; Bohn, T.; Cámara, M.; Castenmiller, J.; De Henauw, S. Hirsch—Ernst. Safety of Tiger nuts (Cyperus esculentus) oil as a novel food pursuant to Regulation. EFSA J. 2024, 22, e9102. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, F.A.; Roriz, C.; Calhelha, R.C.; Rodrigues, P.; Pires, T.C.S.P.; Prieto, M.A.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R.; Barros, L.; Heleno, S.A. Valorization of natural resources—Development of a functional plant-based beverage. Food Chem. 2025, 472, 142813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adedeji, O.E.; Abiodun, O.A.; Adedeji, O.G.; Kang, H.J.; Istiana, N.; Min, J.H.; Ayo, J.A.; Chinma, C.E.; Jung, Y.H. Cellulose synthesis from germinated tiger nut residue and its application in the production of a functional cookie. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 61, 1965–1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Feng, X.; Zhao, Y.; Xia, C.M. Research progress and prospect of precision seeder seeding technology and drive technology. J. Chin. Agric. Mech. 2025, 46, 64–69.82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, W.; Li, W.; Zeng, J.; Han, H.; Yun, X. Study on Formula and Properties of Rubber Track Compound for Agricultural Machinery. China Rubber Ind. 2022, 69, 445–448. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. The application of NBR. China Elastomerics 2022, 41–44. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Wang, X.; Zheng, Z.; Li, X.; Huang, Y. Research Status and Progress of Discrete Element Method Applications in Agricultural Equipment. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2025, 56, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Fang, Q.; Li, M.; Wang, Z.; Wang, C.; Zhang, L. Parameter Calibration for Discrete Element Simulation of Red Clay Soilsin Sloping Cropland in Central Yunnan. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2024, 55, 185–193. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, F.; Zhang, J.; Li, B.; Chen, J. Calibration of parameters of wheat required in discrete element method simulation based on repose angle of particle heap. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2016, 32, 247–253. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Y.; Qi, Y.; Wang, H.; Teng, D.; Chen, J.; Liu, D. Discrete Element Simulation Parameter Calibration and Experiment of Corn Straw—Cow Manure Mixture. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2024, 55, 441–450+504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yu, Z.; Zhang, D.; Chen, Y.; Ni, D. Calibration of Simulation Parameters for Roasted Green TeaBased on Discrete Element Method. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2024, 55, 418–427. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, Y.; You, Y.; Wang, D.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, H.; Ma, W. Parameter Calibration and Experiment of Discrete Element Model forMixed Seeds of Oat and Arrow Pea. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2022, 53, 14–22. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Gao, X.; Jin, X.; Ma, X.; Hu, B.; Zhang, X. Calibration and Analysis of Seeding Parameters of Cyperus esculentus Seeds Based on Discrete Element Simulation. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2023, 54, 58–69. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, S.K.; He, X.N.; Zhu, H.; Liu, Z.X.; Wang, D.W.; Shang, S.Q.; Li, G.H. Vibration Parameter Calibration and Test of Tiger Nut Based on Discrete Element Method. INMATEH Agric. Eng. 2024, 73, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; He, X.; Shang, S.; Wang, D.; Li, C.; Shi, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Lu, Y. Calibration of Discrete Element Simulation Parameters for Tiger Nut Seeds and Experimental Validation. J. Agric. Mech. Res. 2024, 46, 172–178. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.L.; Zhao, H.; Xu, G.H.; Song, J.N.; Dong, X.Q.; Zhang, C.; Wang, J.C. Gradient throwing characteristics of oscillating slat shovel for rhizome crop harvesters. Adv. Mod. Agric. 2022, 3, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Yin, X.; Ma, W.; Jin, C.; Liao, Y. Contact Parameter Calibration for Discrete Element Potato Minituber Seed Simulation. Agriculture 2024, 14, 2298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Y.L.; Zhao, Y.H.; Yuan, S.; Li, F.F.; Ye, C.C.; Chen, H.B.; Chen, R.F. Establishment of Discrete Element Model of Corn Seeds and Parameter Calibration. Jiangsu Agric. Sci. 2024, 52, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, H.Y.; Yan, Y.N.; Shen, Y.; Liu, X.J.; Zhang, J.; Han, X.; Shi, L.; Liu, J. Calibration of discrete element parameters in wheat-corn farming straw mixed soil returning mode. Agric. Eng. 2024, 14, 72–81. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Z.H.; Shang, S.; Xu, N.; Wang, D.W. Parameter Calibration of Discrete Element Simulation Model of Wheat Straw-Soil Mixture in Huang Huai Hai Production Area. INMATEH Agric. Eng. 2022, 66, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y. Study on the Influencing Factors of Cyperus esculentus L. Tuber Germination. Master’s Thesis, Jilin Agricultural University, Changchun, China, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhong, P.; Yang, Z.; Xu, Y.; Chai, H.; Li, S.; Wang, J.; Wu, Y.; Gao, H.; Li, X.; et al. Effects of Soaking Time and Germinating Bed on Germination of Cyperus Esculentus. Mod. Anim. Husb. Sci. Technol. 2023, 98, 93–95. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Liu, Z.; Liu, F. Calibration and Analysis of Seeding Parameters of Soaked Cyperus esculentus L. Seeds. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 2951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, D.; Gao, Y.; Qi, Y.; Wang, H.; Wu, R.; Weng, H. DEM Parameter Calibration and Experimental Definition for White Tea Granular Systems. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, W.; Wang, X.; Han, D.; Enema Ohiemi, I. Design and Testing of Film Picking–Unloading Device of Tillage Residual Film Recycling Machine Based on DEM Parameter Calibration. Agronomy 2025, 15, 955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhai, Q.; Zhang, S.; Li, Q.; Zhou, H. Efficient and Accurate Calibration of Discrete Element Method Parameters for Black Beans. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yang, D.; Liu, M.; Li, Y.; Chen, X.; Cheng, Z. Parameter Optimization and Experiment of Picking Device ofSelf-propelled Potato Collecting Machine. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2023, 54, 20–29. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, H.; Li, K.T.; Qin, Z.Y.; Wang, S.S.; Wang, X.Z.; Sun, F.Y. Discrete Element Model of Oil Peony Seeds and the Calibration of Its Parameters. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.X.; Liu, Y.; Chen, X.B.; Sun, K.; Lai, Q.H. Calibration and Experiment of Simulation Parameters for Panax notoginseng Seeds Based on DEM. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2020, 51, 123–132. [Google Scholar]

| Material | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|

| NBR | Poisson’s Ratio | 0.3 |

| Shear Modulus (MPa) | 38.46 | |

| Density (kg/m3) | 1800 |

| Serial Number | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | Mean Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stacking Angle (°) | 47.82 | 50.24 | 48.53 | 49.87 | 46.75 | 50.76 | 48.13 | 49.55 | 47.28 | 50.57 | 49.03 |

| Factors | Code | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| −1 | 0 | 1 | |

| A Poisson’s Ratio of C. esculentus Seeds | 0.32 | 0.41 | 0.49 |

| B Shear Modulus of C. esculentus Seeds (MPa) | 25 | 33 | 37 |

| C Coefficient of Restitution between C. esculentus Seeds | 0.32 | 0.46 | 0.58 |

| D Static Friction Coefficient between C. esculentus Seeds | 0.42 | 0.56 | 0.69 |

| E Rolling Friction Coefficient between C. esculentus Seeds | 0.22 | 0.31 | 0.43 |

| F Coefficient of Restitution between C. esculentus Seeds and Rubber | 0.34 | 0.54 | 0.74 |

| G Static Friction Coefficient between C. esculentus Seeds and Rubber | 0.20 | 0.26 | 0.32 |

| H Rolling Friction Coefficient between C. esculentus Seeds and Rubber | 0.15 | 0.21 | 0.27 |

| J, K, L Dummy Parameters | — | — | — |

| Serial Number | Factor | Stacking Angle (°) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | J | K | L | ||

| 1 | 1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | −1 | −1 | 51.23 |

| 2 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | 28.86 |

| 3 | −1 | 1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | −1 | −1 | 1 | 1 | 41.04 |

| 4 | 1 | 1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | −1 | 33.16 |

| 5 | 1 | −1 | 1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | 45.72 |

| 6 | 1 | −1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | 49.75 |

| 7 | 1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | −1 | −1 | 1 | 1 | −1 | 55.19 |

| 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 50.16 |

| 9 | 1 | 1 | 1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 40.09 |

| 10 | −1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | −1 | 61.41 |

| 11 | −1 | −1 | −1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | 1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | 34.37 |

| 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 51.23 |

| 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 50.62 |

| 14 | −1 | −1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | −1 | −1 | 1 | 45.70 |

| 15 | −1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | 1 | 45.56 |

| Serial Number | Factor | Stacking Angle θ (°) | Relative Error (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Static Friction Coefficient Between C. esculentus Seeds (D) | Rolling Friction Coefficient Between C. esculentus Seeds (E) | Rolling Friction Coefficient Between C. esculentus Seeds and Rubber (H) | |||

| 1 | 0.4 | 0.22 | 0.12 | 40.24 ± 0.16 | 18.9 |

| 2 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.18 | 44.45 ± 0.25 | 10.42 |

| 3 | 0.6 | 0.38 | 0.24 | 48.68 ± 0.13 | 1.89 |

| 4 | 0.7 | 0.46 | 0.3 | 55.77 ± 0.46 | 12.39 |

| Code | Experimental Factor | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Static Friction Coefficient Between C. esculentus Seeds (D) | Rolling Friction Coefficient Between C. esculentus Seeds (E) | Rolling Friction Coefficient Between C. esculentus Seeds and Rubber (H) | |

| −1 | 0.46 | 0.28 | 0.16 |

| 0 | 0.53 | 0.33 | 0.20 |

| 1 | 0.6 | 0.38 | 0.24 |

| Serial Number | Factor | Stacking Angle θ (°) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| D | E | H | ||

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 44.32 |

| 2 | 0 | 1 | −1 | 49.55 |

| 3 | 1 | 0 | −1 | 51.06 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 44.17 |

| 5 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 52.07 |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 45.16 |

| 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 45.21 |

| 8 | 0 | −1 | −1 | 45.98 |

| 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 45.63 |

| 10 | 1 | −1 | 0 | 49.99 |

| 11 | −1 | 1 | 0 | 49.69 |

| 12 | −1 | −1 | 0 | 48.56 |

| 13 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 53.91 |

| 14 | −1 | 0 | 1 | 48.57 |

| 15 | −1 | 0 | −1 | 47.98 |

| 16 | 0 | −1 | 1 | 47.77 |

| 17 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 51.16 |

| Soaking Duration (h) | Germination Rate (%) | Germination Potential (%) | Germination Delay (d) | Germination Period (d) | Germination Index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 52.00 ± 8.72 c | 63.33 ± 7.57 c | 3.67 ± 0.58 a | 14.33 ± 0.58 a | 2.93 ± 0.39 c |

| 24 | 68.00 ± 2.00 b | 73.33 ± 1.15 b | 3 b | 13.67 ± 0.58 a | 4.06 ± 0.07 b |

| 48 | 89.33 ± 1.15 a | 92.67 ± 2.31 a | 2 c | 8.67 ± 1.16 b | 5.41 ± 0.04 a |

| 72 | 40.00 ± 2.00 d | 40.67 ± 2.31 d | 2 c | -- | 2.69 ± 0.12 c |

| Soaking Duration (h) | Root Fresh Weight (mg) | Shoot Fresh Weight (mg) | Total Root Length (cm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 40.47 ± 4.64 c | 49.2 ± 7.83 c | 22.61 ± 5.03 c |

| 24 | 64.2 ± 9.31 b | 60.93 ± 10.24 b | 44.15 ± 7.34 b |

| 48 | 100.4 ± 10.82 a | 102.5 ± 9.52 a | 78.07 ± 4.58 a |

| Source of Variation | Contribution (%) | F-Value | p-Value | Significance Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | -- | 10.85 | 0.0089 | -- |

| A | 2.52 | 2.57 | 0.1695 | 5 |

| B | 3.30 | 3.37 | 0.1259 | 7 |

| C | 0.10 | 0.103 | 0.7613 | 4 |

| D | 20.53 | 20.95 | 0.006 | 3 |

| E | 44.62 | 45.55 | 0.0011 | 2 |

| F | 3.59 | 3.67 | 0.1137 | 1 |

| G | 1.86 | 1.9 | 0.2265 | 8 |

| H | 8.54 | 8.71 | 0.0318 | 6 |

| Source of Variation | Mean Square | Sum of Squares | Degrees of Freedom | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 14.51 | 130.63 | 9 | 0.0001 |

| D | 18.7 | 18.7 | 1 | 0.0002 |

| E | 18.03 | 18.03 | 1 | 0.0002 |

| H | 3.13 | 3.13 | 1 | 0.0218 |

| DE | 1.95 | 1.95 | 1 | 0.0535 |

| DH | 0.0441 | 0.0441 | 1 | 0.7374 |

| EH | 0.0081 | 0.0081 | 1 | 0.8853 |

| D2 | 50.76 | 50.76 | 1 | 0.0001 |

| E2 | 19.78 | 19.78 | 1 | 0.0002 |

| H2 | 10.11 | 10.11 | 1 | 0.0011 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, Z.; Yan, J.; Liu, F.; Wang, L. Calibration and Testing of Discrete Element Simulation Parameters for the Presoaked Cyperus esculentus L. Rubber Interface Using EDEM. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2440. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15102440

Liu Z, Yan J, Liu F, Wang L. Calibration and Testing of Discrete Element Simulation Parameters for the Presoaked Cyperus esculentus L. Rubber Interface Using EDEM. Agronomy. 2025; 15(10):2440. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15102440

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Zhenyu, Jianguo Yan, Fei Liu, and Lijuan Wang. 2025. "Calibration and Testing of Discrete Element Simulation Parameters for the Presoaked Cyperus esculentus L. Rubber Interface Using EDEM" Agronomy 15, no. 10: 2440. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15102440

APA StyleLiu, Z., Yan, J., Liu, F., & Wang, L. (2025). Calibration and Testing of Discrete Element Simulation Parameters for the Presoaked Cyperus esculentus L. Rubber Interface Using EDEM. Agronomy, 15(10), 2440. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15102440