Intelligent Modeling of Erosion-Corrosion in Polymer Composites: Integrating Fuzzy Logic and Machine Learning

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Method

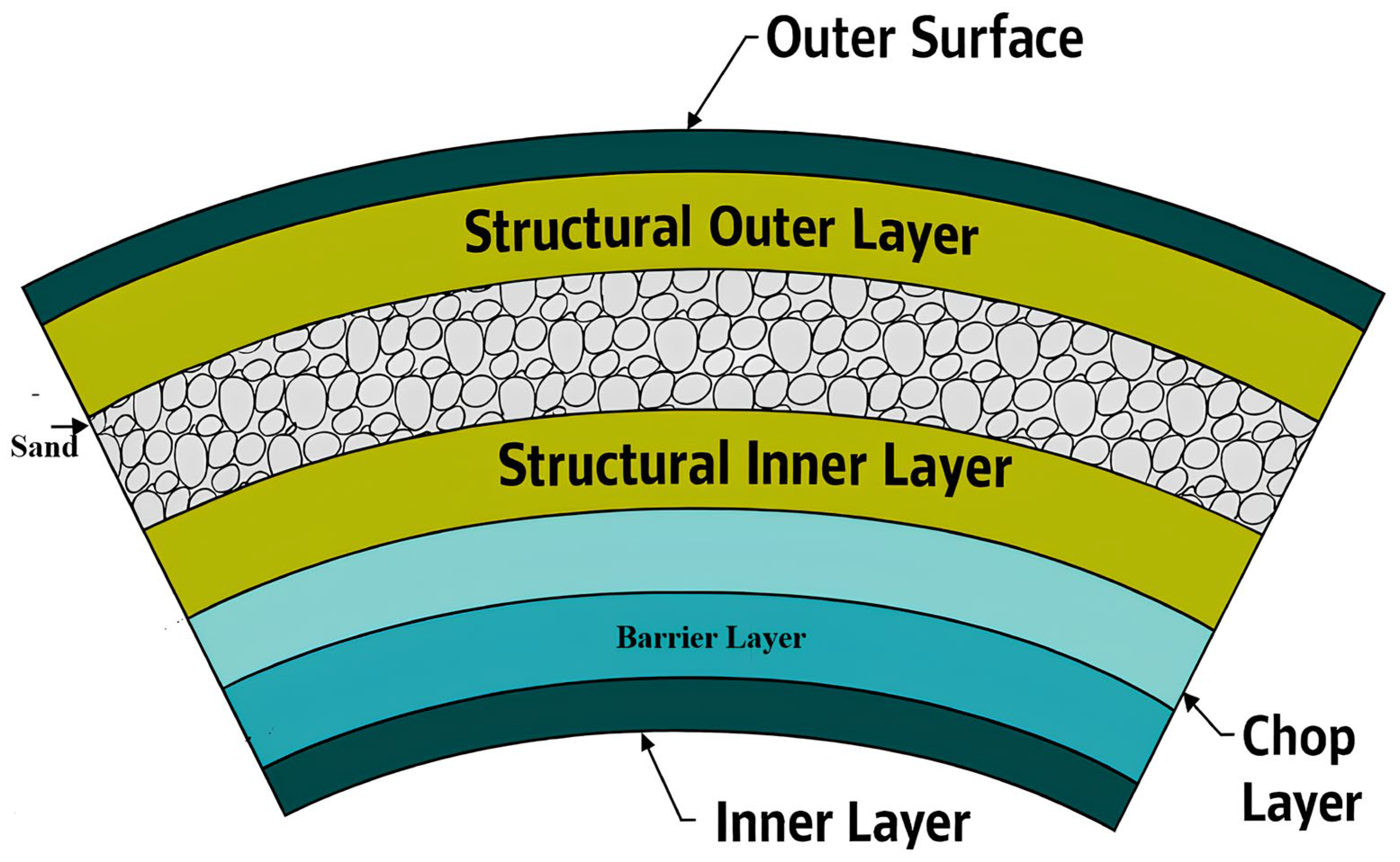

2.1. Glass-Fiber-Reinforced Pipe (GRP)

2.2. Experimental Basis and Dataset Parameters

- Abrasive Agent: Silica sand with a mean particle size of 65 µm.

- Sand Concentration: Three discrete sand masses were used per test: 250 g, 400 g, and 500 g, each mixed with the total water volume of 0.015 m3 in the apparatus reservoir.

- Fluid Volume: A constant water volume of 0.015 m3 was used for all slurry mixtures.

- Corrosive Agent: A chlorine concentration of 10 wt.% was added to the slurry for a subset of tests to investigate chemical corrosion.

- Flow Rate: Three flow rate conditions were applied: 0.0067 m3/min, 0.01 m3/min, and 0.015 m3/min.

- Impact Angle: The slurry jet impacted on the sample surface at a constant 90-degree angle.

- Exposure Time: Tests were conducted for five discrete durations: 1 h, 2 h, 3 h, 4 h, and 5 h.

3. Methodology: Hybrid Intelligent Modeling Framework

4. Result and Discussion

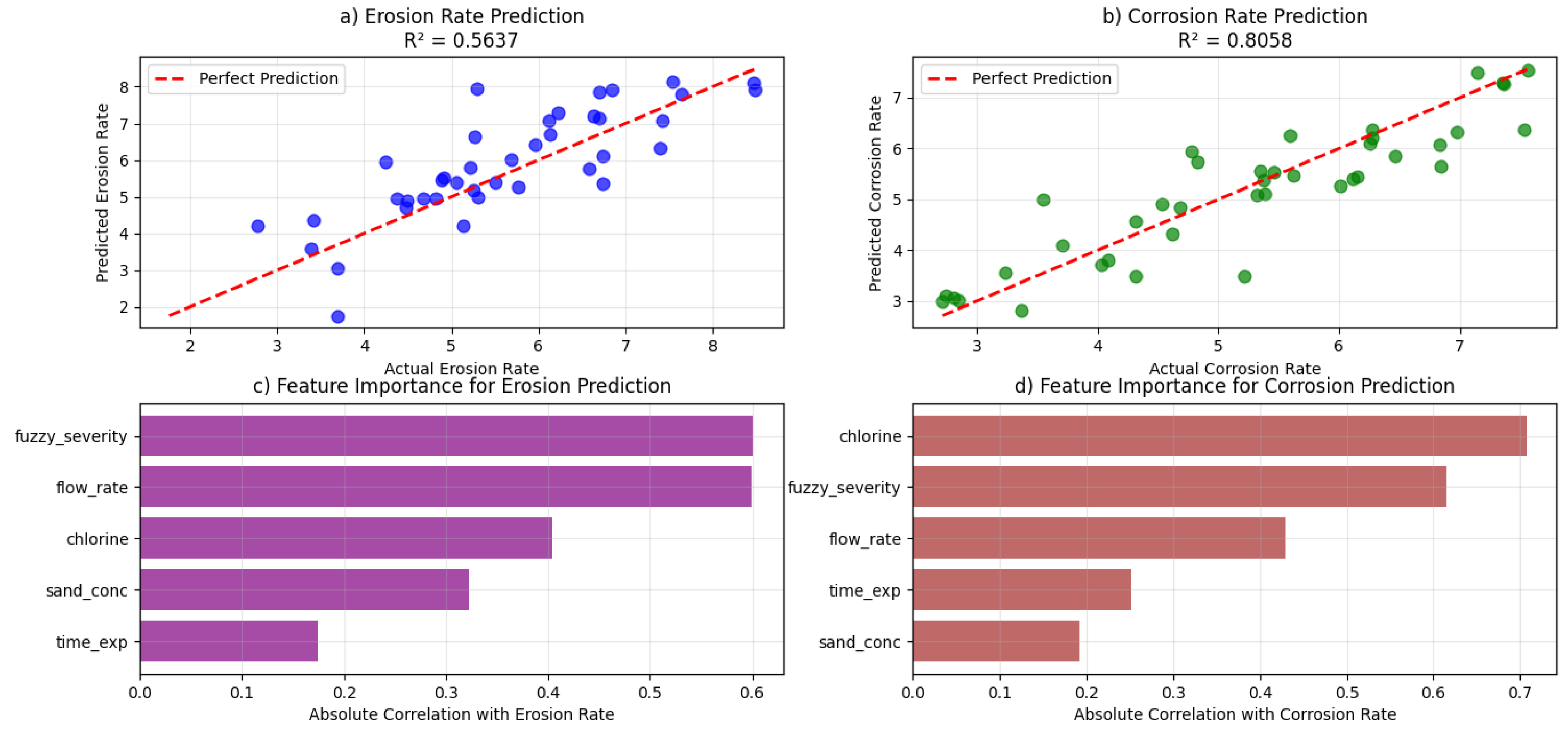

4.1. Fuzzy Logic and ANN Models

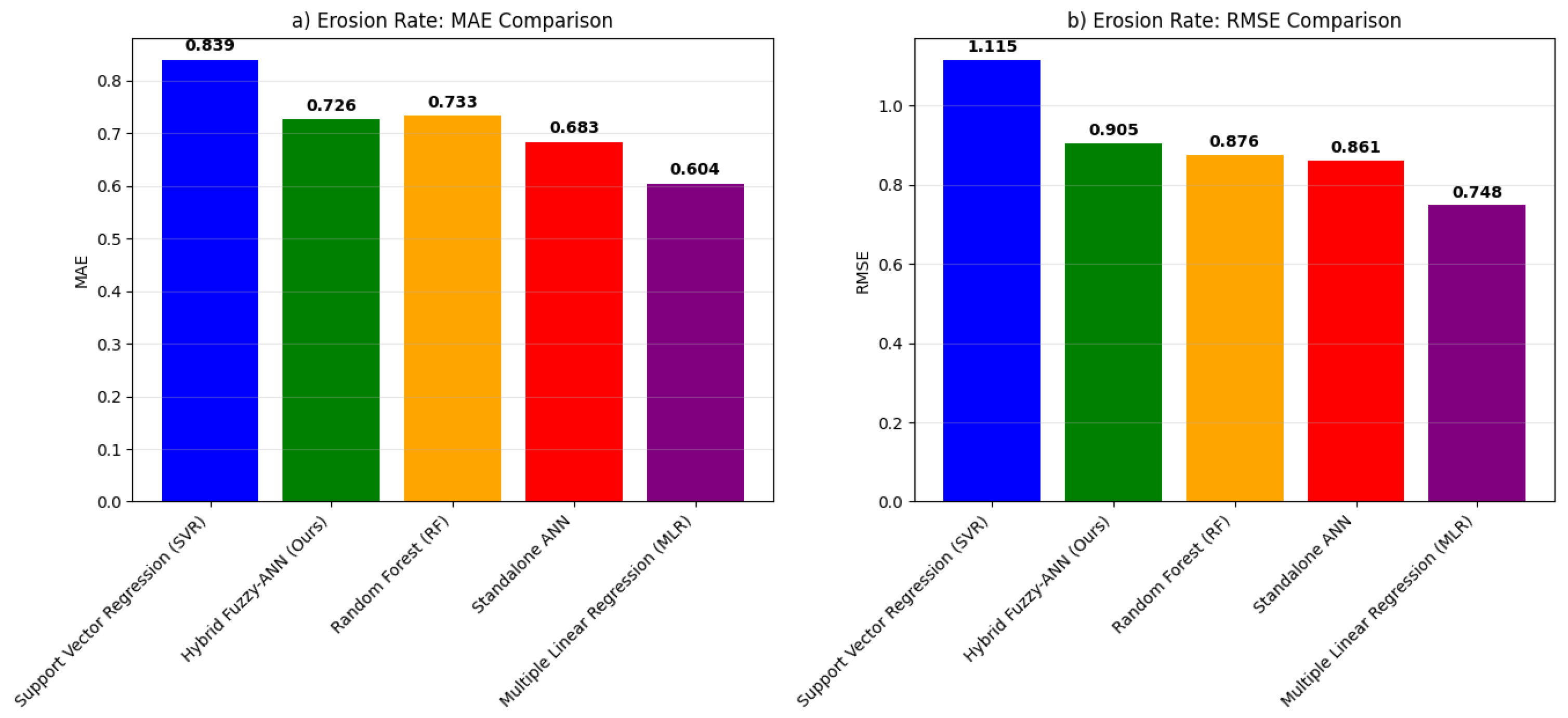

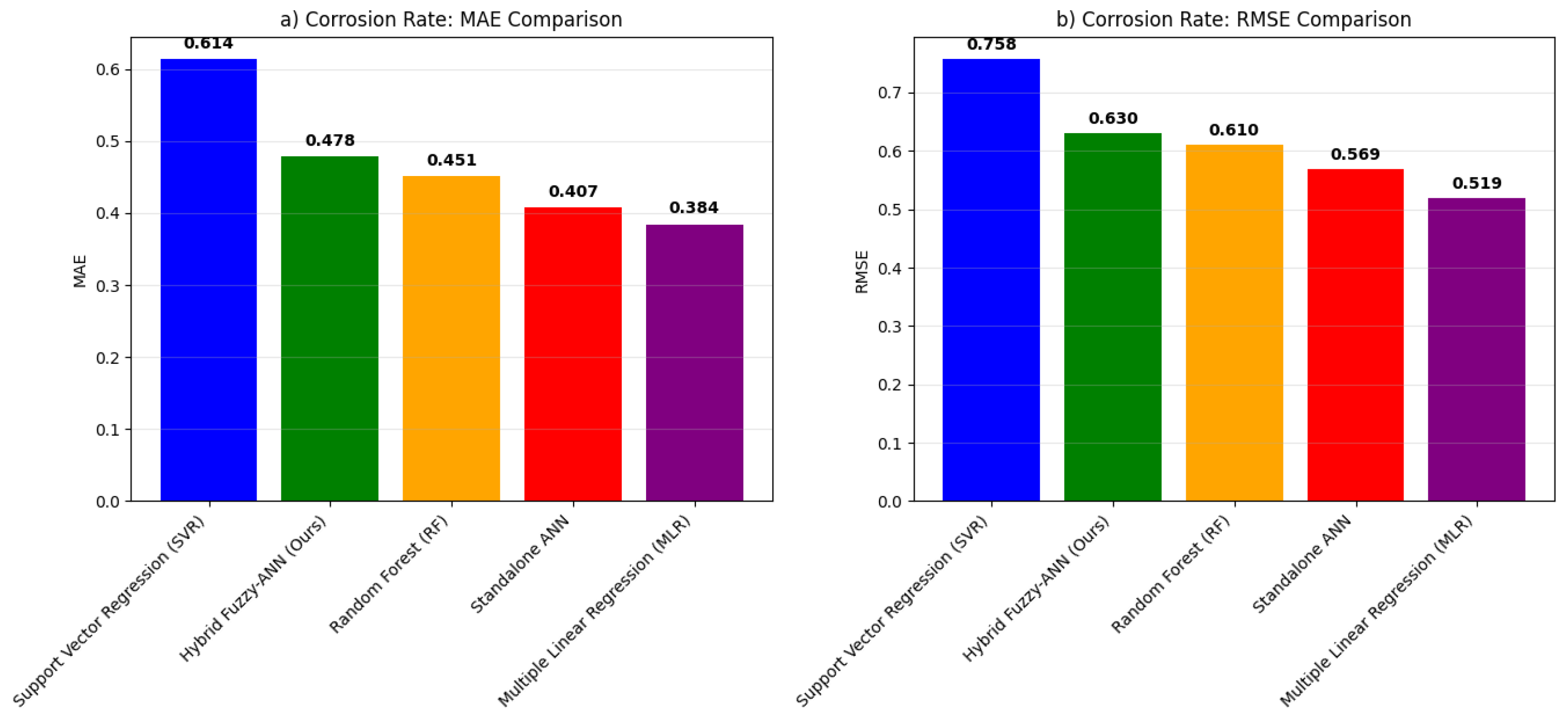

4.2. Model Performance and Benchmarking

4.3. Physicochemical Analysis of Prediction Discrepancy: Erosion vs. Corrosion Mechanisms

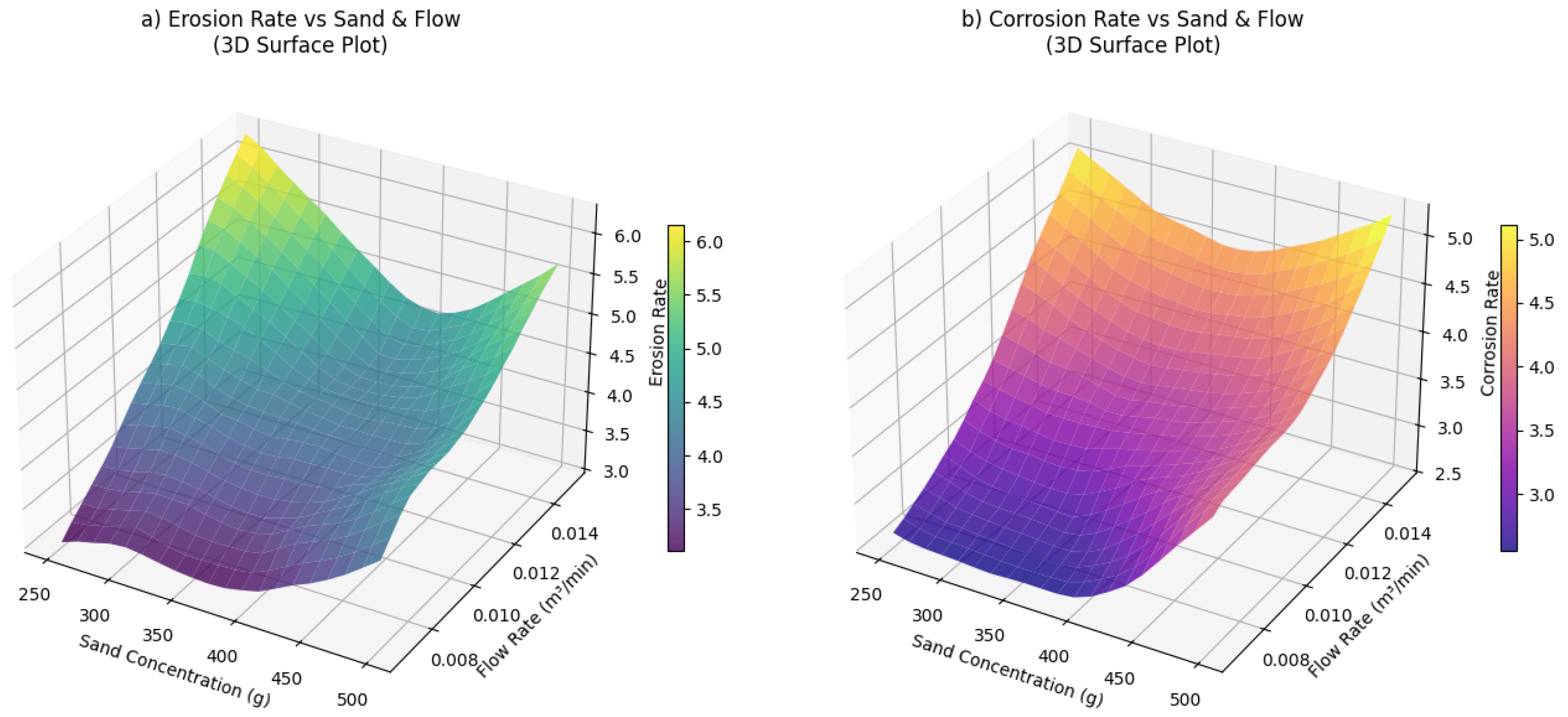

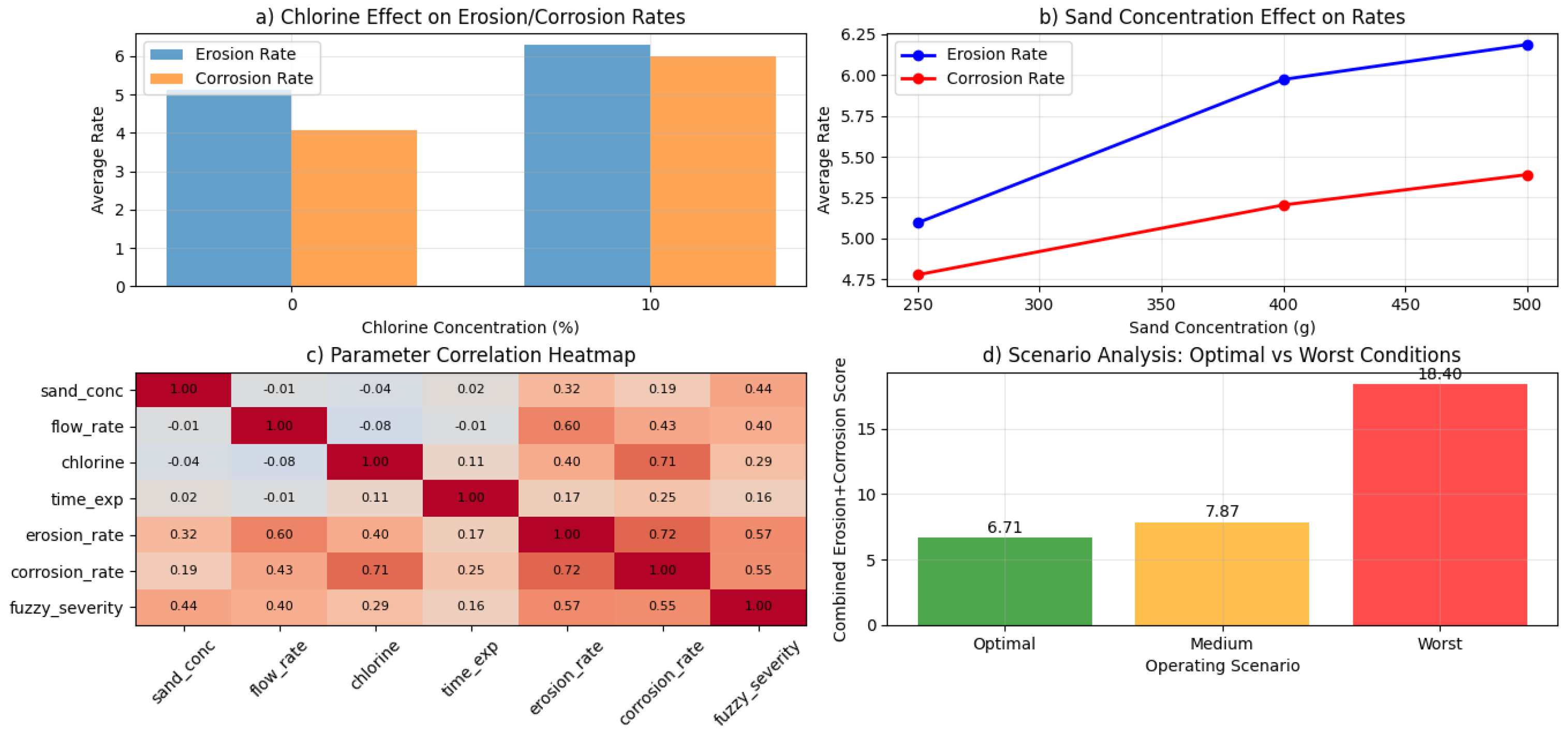

4.3.1. Erosion as a Stochastic, Mechanics-Dominated Process

4.3.2. Corrosion as a Deterministic, Chemistry-Driven Process

4.3.3. Synergistic Effects and Practical Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fukushima, K.; Cai, H.; Nakada, M.; Miyano, Y. Determination of time-temperature shift factor for long-term life prediction of polymer composites. In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Composite Materials, Edinburgh, UK, 27–31 July 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Plota, A.; Masek, A. Lifetime prediction methods for degradable polymeric materials—A short review. Materials 2020, 13, 4507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdellah, M.Y. Comparative study on prediction of fracture toughness of CFRP laminates from size effect law of open hole specimen using cohesive zone model. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2018, 191, 277–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyano, Y.; Nakada, M.; Sekine, N. Accelerated Testing for Long-term Durability of FRP Laminates for Marine Use. J. Compos. Mater. 2005, 39, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Parvatareddy, H.; Chang, T.; Iyengar, N.; Dillard, D.; Reifsnider, K. Physical aging behavior of high-performance composites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 1995, 54, 405–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbero, E.J.; Julius, M.J. Time-Temperature-Age Viscoelastic Behavior of Commercial Polymer Blends and Felt Filled Polymers. Mech. Adv. Mater. Struct. 2004, 11, 287–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.K.; Redhwi, A.M.N.; Mohamed, A.F.; Backar, A.H.; Abdellah, M.Y. Investigation of Erosion/Corrosion Behavior of GRP under Harsh Operating Conditions. Polymers 2022, 14, 5388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdellah, M.Y.; Alfattani, R.; Alnaser, I.A.; Abdel-Jaber, G.T. Stress Distribution and Fracture Toughness of Underground Reinforced Plastic Pipe Composite. Polymers 2021, 13, 2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouri, M.; Ashenai-Ghasemi, F.; Rahimi-Sherbaf, G.; Kashyzadeh, K.R. Experimental and Numerical Study of the Static Performance of a Hoop-Wrapped CNG Composite Cylinder Considering Its Variable Wall Thickness and Polymer Liner. Mech. Compos. Mater. 2020, 56, 339–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, J.H.S., Jr.; Ribeiro, M.L.; Tita, V.; Amico, S.C. Damage and failure in carbon/epoxy filament wound composite tubes under external pressure: Experimental and numerical approaches. Mater. Des. 2016, 96, 431–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pani, B.; Chandrasekhar, P.; Singh, S. A study on erosion wear behavior of iron-mud/glass fiber reinforced epoxy composite. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Velosa, J.; Nunes, J.; Antunes, P.; Silva, J.; Marques, A. Development of a new generation of filament wound composite pressure cylinders. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2009, 69, 1348–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Soutis, C.; Ando, D.; Sutou, Y.; Narita, F. Application of deep neural network learning in composites design. Eur. J. Mater. 2022, 2, 117–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulkir, O.; Akgun, G.; Karadag, A. Mechanical Behavior Prediction of 3D-Printed PLA/Wood Composites Using Artificial Neural Network and Fuzzy Logic. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2025, 36, e70103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almtori, S.A.; Al-Fahad, I.O.B.; Al-temimi, A.H.T.; Jassim, A.K. Characterization of polymer based composite using neuro-fuzzy model. Mater. Today: Proc. 2021, 42, 1934–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldırım, H. Optimized neural networks and fuzzy logic for predicting post-buckling loads in polymer composite tubes. Arch. Appl. Mech. 2025, 95, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D3171-99; Standard Test Methods for Constituent Content of Composite Materials. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2015.

- Shi, H.; An, Z.; Gao, R. Simulation of Mechanical Behavior and Structural Analysis of Glass Fiber Reinforced Mortar Pipes. Rev. Romana De Mater. 2020, 50, 198–204. [Google Scholar]

- Abdellah, M.Y.; Hassan, M.K.; Alsoufi, M.S. Fracture and Mechanical Characteristics Degradation of Glass Fiber Reinforced Petroleum epoxy Pipes. J. Manuf. Sci. Prod. 2016, 16, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faria, H. Failure Analysis of GRP Pipes Under Compressive Ring Loads. Master’s Thesis, Universidade do Porto, Porto, Portugal, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan, T.; Suresh, G.; Ramu, P.; Vignesh, R.; Harshan, A.V.; Vignesh, K. Effect of hygrothermal ageing on the compressive behavior of glass fiber reinforced IPN composite pipes. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 45, 1354–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM G31-72; Standard Practice for Laboratory Immersion Corrosion Testing of Metals. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2004.

- Zadeh, L.A. Fuzzy sets. Inf. Control. 1965, 8, 338–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, T.J. Fuzzy Logic with Engineering Applications; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Mendel, J.M. Uncertain Rule-Based Fuzzy Systems: Introduction and New Directions; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mamdani, E.H.; Assilian, S. An experiment in linguistic synthesis with a fuzzy logic controller. Int. J. Man-Mach. Stud. 1975, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumelhart, D.E.; Hinton, G.E.; Williams, R.J. Learning representations by back-propagating errors. Nature 1986, 323, 533–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingma, D.P. Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1412.6980. [Google Scholar]

- Haykin, S. Neural Networks and Learning Machines, 3rd ed.; Pearson Education India: Chennai, India, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hojo, H.; Tsuda, K.; Kubouchi, M.; Kim, D.S. Corrosion of plastics and composites in chemical environments. Met. Mater. 1998, 4, 1191–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farshad, M.; Necola, A. Effect of aqueous environment on the long-term behavior of glass fiber-reinforced plastic pipes. Polym. Test. 2004, 23, 163–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, A.; Kim, I. Solid particle erosion of CFRP composite with different laminate orientations. Wear 2009, 267, 1922–1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouad, Y.; El-Meniawi, M.; Afifi, A. Erosion behaviour of epoxy based unidirectionl (GFRP) composite materials. Alex. Eng. J. 2011, 50, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.K.; Mohamed, A.F.; Khalil, K.A.; Abdellah, M.Y. Numerical and Experimental Evaluation of Mechanical and Ring Stiffness Properties of Preconditioning Underground Glass Fiber Composite Pipes. J. Compos. Sci. 2021, 5, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farshad, M.; Necola, A. Strain corrosion of glass fibre-reinforced plastics pipes. Polym. Test. 2004, 23, 517–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julius, M.J. Time, Temperature and Frequency Viscoelastic Behavior of Commercial Polymers. Master’s Thesis, West Virginia University, Morgantown, WV, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, J.; Ziegmann, G. Equivalence of moisture and temperature in accelerated test method and its application in prediction of long-term properties of glass-fiber reinforced epoxy pipe specimen. Polym. Test. 2006, 25, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Alqurashi, H.F.; Abdellah, M.Y.; Alshareef, M.; Hassan, M.K.; Alabdullah, F.T.; Moamed, A.F. Intelligent Modeling of Erosion-Corrosion in Polymer Composites: Integrating Fuzzy Logic and Machine Learning. Polymers 2026, 18, 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010009

Alqurashi HF, Abdellah MY, Alshareef M, Hassan MK, Alabdullah FT, Moamed AF. Intelligent Modeling of Erosion-Corrosion in Polymer Composites: Integrating Fuzzy Logic and Machine Learning. Polymers. 2026; 18(1):9. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010009

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlqurashi, Hazzaa F., Mohammed Y. Abdellah, Mubark Alshareef, Mohamed K. Hassan, Fadhel T. Alabdullah, and Ahmed F. Moamed. 2026. "Intelligent Modeling of Erosion-Corrosion in Polymer Composites: Integrating Fuzzy Logic and Machine Learning" Polymers 18, no. 1: 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010009

APA StyleAlqurashi, H. F., Abdellah, M. Y., Alshareef, M., Hassan, M. K., Alabdullah, F. T., & Moamed, A. F. (2026). Intelligent Modeling of Erosion-Corrosion in Polymer Composites: Integrating Fuzzy Logic and Machine Learning. Polymers, 18(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010009