Nitrates of Synthetic Cellulose

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Substrate for Study

Physicochemical Analysis of SC

2.2. Nitration and Stabilization of SC

2.3. Calculation of the Actual Yield of SC-Based NC

2.4. Physicochemical Analysis of SC-Based NC

2.5. Structural Analysis of SC and SC-Based NC

2.5.1. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) of SC and SC-Based NC

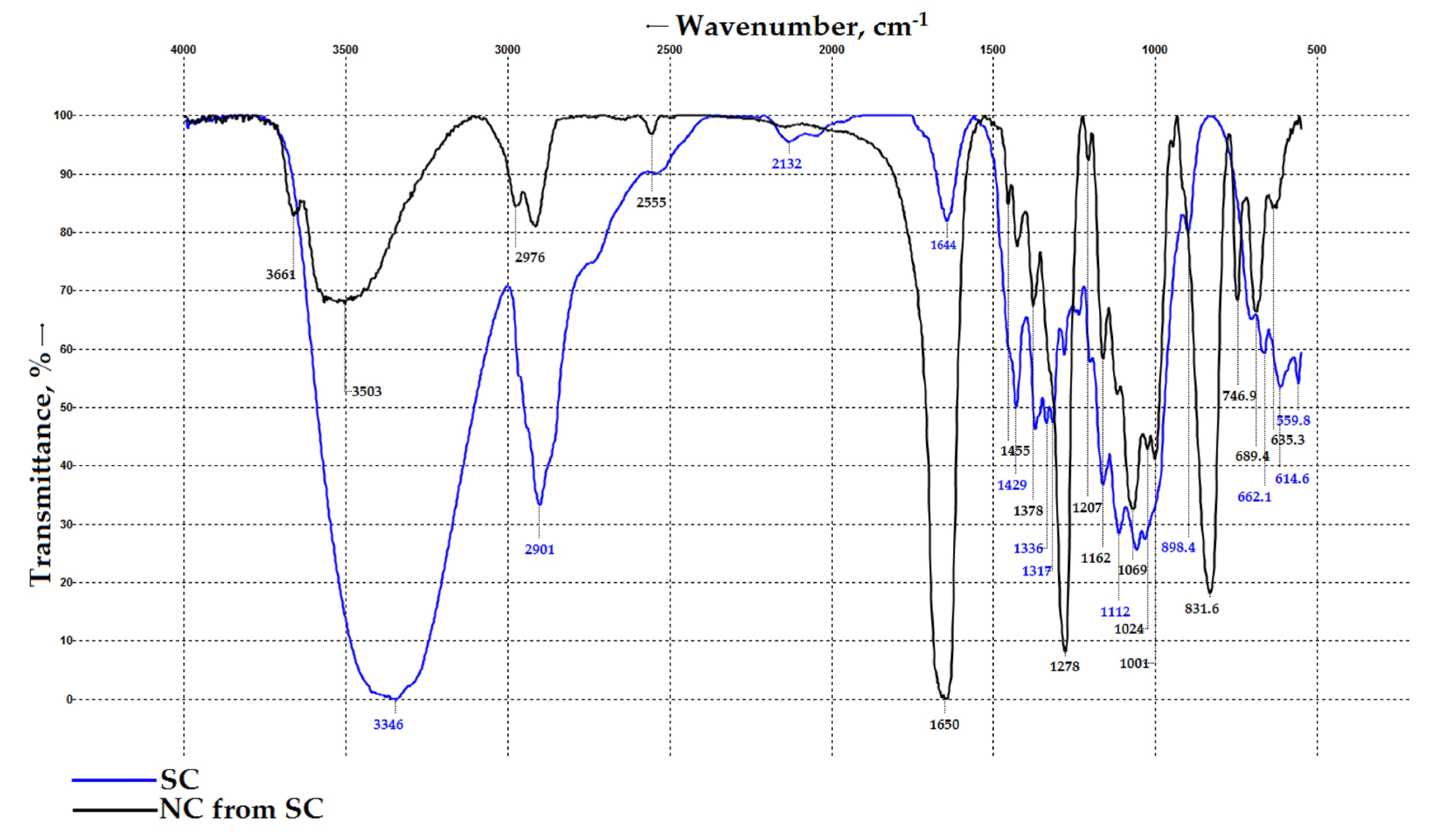

2.5.2. IR Fourier Spectroscopy of SC and SC-Based NC

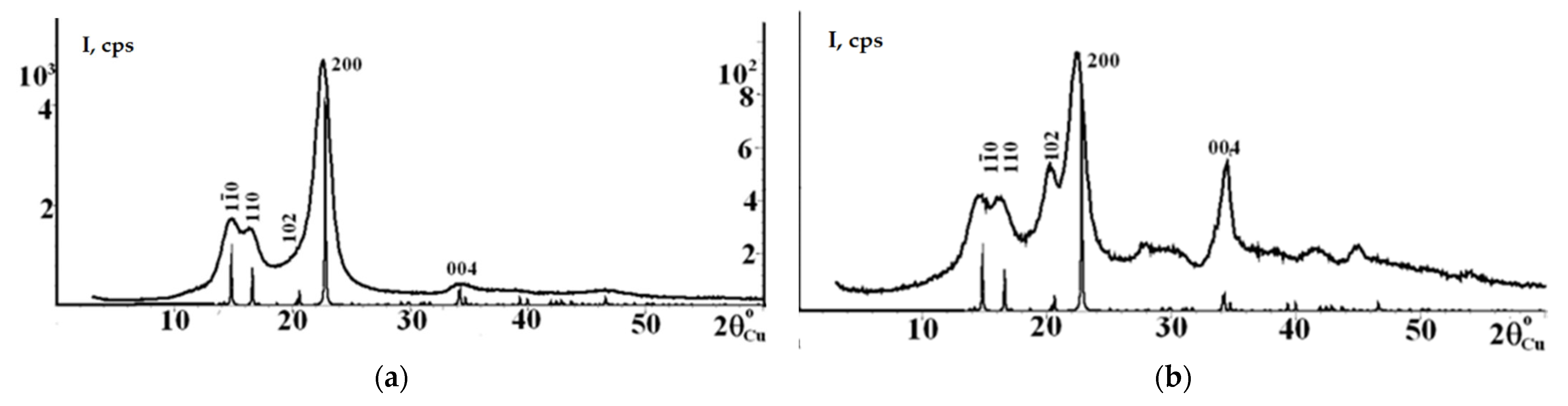

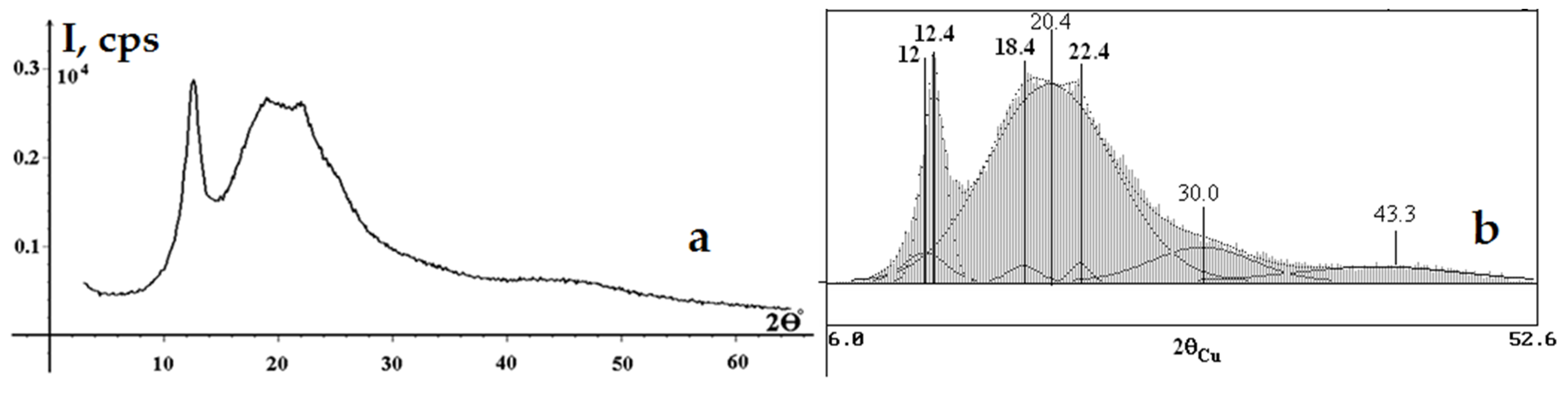

2.5.3. X-Ray Diffraction Analysis (XRD) of SC and SC-Based NC

2.5.4. Coupled Thermogravimetric and Differential Thermal Analysis (TGA-DTA)

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Physicochemical Properties of the SC Sample

3.2. Physicochemical Properties of SC-Based NC

3.3. SEM Results for SC and SC-Based NC

3.4. FT-IR Spectroscopy Results for SC and SC-Based NC

3.5. XRD Results for SC and SC-Based NC

3.6. TGA/DTA Results for SC and SC-Based NC

3.7. Potential Applications of Synthetic Cellulose Nitrates

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Amelia, S.T.W.; Widiyastuti, W.; Nurtono, T.; Setyawan, H.; Widyastuti, W.; Ardhyananta, H. Acid hydrolysis roles in transformation of cellulose-I into cellulose-II for enhancing nitrocellulose performance as an energetic polymer. Cellulose 2024, 31, 9583–9595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Nan, F.; Zheng, Y.; Chen, L.; He, W. Hygroscopicity of nitrocellulose with different nitrogen content. Propellants Explos. Pyrotech. 2024, 49, e202300035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, J.; Archana, K.S.; Thomas, A.M.; Thomas, R.L.; Thomas, J.; Thomas, V.; Unnikrishnan, N.V. Nitrocellulose unveiled: A brief exploration of recent research progress. SCE 2024, 5, 146–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Lei, M.; Ren, J.; Li, Z.; Duan, X.; Shen, J.; Pei, C. Influence of solvents on solubility, processability, thermo-stability, and mechanical properties of nitrocellulose gun propellants. Cellulose 2025, 32, 1539–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Chen, L.; Nan, F.; Wang, B.; Cao, X.; Meng, D.; He, W. The integration of civilian nitrocellulose in propellant with highly improved mechanical property and thermal stability, and study on its combustion behavior. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2024, 221, 110689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahim, A.K.S.; Samsuri, A.; Jamal, S.H.; Nor, S.A.M.; Rusly, S.N.A.; Ariff, H.; Latif, N.S.A. Redefining biofuels: Investigating oil palm biomass as a promising cellulose feedstock for nitrocellulose-based propellant production. Def. Technol. 2024, 37, 111–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarchoun, A.F.; Trache, D.; Hamouche, M.A.; Abdelaziz, A.; Boukeciat, H.; Chentir, I.; Klapötke, T.M. Elucidating the characteristics of a promising nitrate ester polysaccharide derived from shrimp shells and its blends with cellulose nitrate. Cellulose 2023, 30, 4941–4955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Li, H.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, F.; Li, H.; Xu, K. Enhanced thermal decomposition, laser ignition and combustion properties of NC/Al/RDX composite fibers fabricated by electrospinning. Cellulose 2021, 28, 6089–6105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, K.; Saito, Y.; Akiyoshi, M.; Endo, T.; Matsunaga, T. Preparation and Characterization of Nitrocellulose Nano-fiber. Propellants Explos. Pyrotech. 2021, 46, 962–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, M.J., Jr. Wildlife toxicity assessment for nitrocellulose. In Wildlife Toxicity Assessments for Chemicals of Military Concern; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaing, E.M.; Jitrangsri, K.; Chomto, P.; Phaechamud, T. Nitrocellulose for Prolonged Permeation of Levofloxacin HCl-Salicylic Acid In Situ Gel. Polymers 2024, 16, 989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senarat, S.; Rojviriya, C.; Sarunyakasitrin, K.; Charoentreeraboon, J.; Pichayakorn, W.; Phaechamud, T. Moxifloxacin HCl-incorporated aqueous-induced nitrocellulose-based in situ gel for periodontal pocket delivery. Gels 2024, 9, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, R.; Xie, M.Y.; Li, M.; Cao, L.; Feng, S.; Li, Z.; Xu, F. Nitrocellulose membrane for paper-based biosensor. Appl. Mater. Today 2022, 26, 101305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, R.; Xie, M.; Yan, X.; Qian, L.; Giesy, J.P.; Xie, Y. A nitrocellulose/cotton fiber hybrid composite membrane for paper-based biosensor. Cellulose 2023, 30, 6457–6469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toader, G.A.; Nitu, F.R.; Ionita, M. Graphene Oxide/Nitrocellulose Non-Covalent Hybrid as Solid Phase for Oligo-DNA Extraction from Complex Medium. Molecules 2023, 28, 4599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, W.; Cao, Y.; Lin, S.; Wu, T. Development of porous nitrocellulose membrane for lateral flow immunoassays. J. Membr. Sci. 2025, 735, 124591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.; Li, Z.; Peng, X.; Yang, F.; Cao, Y.; Xiang, M.; Wu, T. Formation mechanism of ordered porous nitrocellulose membranes by breath figure templating. Polymer 2024, 294, 126733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, R.; Alam, N.; Li, M.; Xie, M.; Ni, Y. Dissolvable sugar barriers to enhance the sensitivity of nitrocellulose membrane lateral flow assay for COVID-19 nucleic acid. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 268, 118259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesas Gómez, M.; Molina-Moya, B.; de Araujo Souza, B.; Boldrin Zanoni, M.V.; Julián, E.; Domínguez, J.; Pividori, M.I. Improved biosensing of Legionella by integrating filtration and immunomagnetic separation of the bacteria retained in filters. Microchim. Acta 2024, 191, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, J.G.; Almeida, C.A.; Fernández-Baldo, M.A.; Felici, E.; Raba, J.; Sanz, M.I. Development of nitrocellulose membrane filters impregnated with different biosynthesized silver nanoparticles applied to water purification. Talanta 2016, 146, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J. Nitrate Esters Chemistry and Technology; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 1–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhegrov, E.F.; Milekhin, Y.M.; Berkovskaya, E.V. Chemistry and Technology of Ballistit Powders, Solid Rocket and Special Propellants (Khimiya i Tekhnologiya Ballistitnykh Porokhov, Tverdykh Raketnykh i Spetsial’nykh Topliv); RITs MGUP Named After I. Fedorov: Moscow, Russia, 2011; Volume 2, pp. 35–101. Available online: https://studfile.net/preview/19992815/ (accessed on 10 November 2025). (In Russian)

- Gashtroudkhani, A.K.; Dahmardeh Ghalehno, M.; Abadi, S.S.; Pouyani, M. A novel, low-cost, and high-efficiency method for nitrocellulose synthesis from plasma-modified cellulose. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 6281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizkiansyah, R.R.; Mardiyati, Y.; Hariyanto, A.; Dirgantara, T. Selecting appropriate cellulose morphology to enhance the nitrogen content of nitrocellulose. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 28260–28271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ioelovich, M. Thermodynamic analysis of cellulose nitration. World J. Adv. Res. Rev. 2024, 21, 485–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gashtroudkhani, A.K.; Ghalehno, M.D.; Abadi, S.S.; Pouyani, M.; Salimi, A. A new process for producing of commercial nitrocellulose with chipping technology of sheet wood pulp. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 17470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torgun, I.N.; Nikishov, V.P.; Buchnev, I.I.; Ryzhov, A.I.; Gubkin, A.M.; Kutsenko, G.V.; Ibragimov, N.G.; Ivanova, I.P.; Zakharov, A.G.; Prusov, A.N.; et al. Flax in Powder Industry (Len v Porokhovoi Promyshlennosti); Grigorov, S.I., Ed.; FGUP TsNIIKhM: Moscow, Russia, 2015; 348p. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Kashcheyeva, E.I.; Korchagina, A.A.; Gismatulina, Y.A.; Gladysheva, E.K.; Budaeva, V.V.; Sakovich, G.V. Simulta-neous production of cellulose nitrates and bacterial cellulose from lignocellulose of energy crop. Polymers 2024, 16, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korchagina, A.A.; Gorbatova, P.A.; Budaeva, V.V.; Zolotukhin, V.N. Nitration of Miscanthus var. Soranovskii cellulose with a high degree of polymerization. J. Sib. Fed. Univ. Chem. 2024, 17, 268–278. [Google Scholar]

- Yolhamid, M.N.A.G.; Ibrahim, F.; Zarim, M.A.U.A.A.; Ibrahim, R.; Adnan, S.; Yahya, M.Z.A. The processing of nitrocellulose from rhizophora, palm oil bunches (EFB) and kenaf fibres as a propellant grade. Int. J. Eng. Technol. 2018, 7, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khorasani, A.C.; Bajestani, S.Z.; Bajestani, A.S. Comparative techno-economic assessment of production of microcrystalline cellulose, microcrystalline nitrocellulose, and solid biofuel for biorefinery of pistachio shell. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2023, 24, 101673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, X.; Li, Z.; Shi, X.; Pe, C. Giant panda feces: Potential raw material in preparation of nitrocellulose for propellants. Cellulose 2023, 30, 3127–3140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muvhiiwa, R.; Mawere, E.; Moyo, L.B.; Tshuma, L. Utilization of cellulose in tobacco (Nicotiana tobacum) stalks for nitrocellulose production. Heliyon 2021, 7, e07598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korchagina, A.A.; Gismatulina, Y.A.; Budaeva, V.V.; Kukhlenko, A.A.; Vdovina, N.P.; Ivanov, P.P. Autoclaving cellulose nitrates obtained from fruit shells of oats. Izv. Vyssh. Uchebn. Zaved. Khim. Khim. Tekhnol. 2020, 63, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarchoun, A.F.; Trache, D.; Klapötke, T.M.; Chelouche, S.; Derradji, M.; Bessa, W.; Mezroua, A. A Promising ener-getic polymer from Posidonia oceanica Brown Algae: Synthesis, characterization, and kinetic modeling. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2019, 220, 1900358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizkiah, R.; Kencanawati, K.; Rosidin, A.; Wibowo, L. Sintesis Nitroselulosa Dari Serat Rami (Boechmerianivea) Menggunakan Trietilamin. Sainteks J. Sain Teknik 2021, 3, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jesuet, M.S.G.; Musa, N.M.; Idris, N.M.; Musa, D.N.S.; Bakansing, S.M. Properties of Nitrocellulose from Acacia mangium. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2019, 1358, 012035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trache, D.; Khimeche, K.; Mezroua, A.; Benziane, M. Physicochemical properties of microcrystalline nitrocellulose from Alfa grass fibres and its thermal stability. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2016, 124, 1485–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gismatulina, Y.A.; Budaeva, V.V.; Sakovich, G.V. Cellulose nitrates from intermediate flax straw. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2016, 65, 2920–2924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roslan, N.J.; Jamal, S.H.; Rashid, J.I.A.; Norrrahim, M.N.F.; Ong, K.K.; Yunus, W.M.Z.W. Response surface meth-odology for optimization of on nitrocellulose preparation from nata de coco bacterial cellulose for propellant formulation. Heliyon 2024, 10, e25993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gismatulina, Y.A. Promising Energetic Polymers from Nanostructured Bacterial Cellulose. Polymers 2023, 15, 2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gismatulina, Y.A.; Budaeva, V.V. Cellulose nitrates-blended composites from bacterial and plant-based celluloses. Polymers 2024, 16, 1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehrhofer, A.F.; Goto, T.; Kawada, T.; Rosenau, T.; Hettegger, H. The in vitro synthesis of cellulose—A mini-review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 285, 119222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Infotek Grup. A Process for Synthetic Cellulose. RU Patent 2663434, 6 August 2018. Available online: https://i.moscow/patents/ru2663434c1_20180806 (accessed on 30 October 2025). (In Russian).

- TAPPI. Alpha-, Beta-, and Gamma-Cellulose in Pulp, Test Method T 203 cm-22; TAPPI Press: Atlanta, GA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- TAPPI. Ash in Wood, Pulp, Paper and Paperboard: Combustion at 525 °C. Test method T. 211 om-02; TAPPI: Peachtree Corners, GA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bogolitsyn, K.; Parshina, A.; Aleshina, L. Structural features of brown algae cellulose. Cellulose 2020, 27, 9787–9800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotton Cellulose, Specifications. USSR State Committee for Product Quality Management and Standards: Moscow, Russia, 1980. Available online: https://docs.cntd.ru/document/1200018162 (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- van den Hurk, R.S.; Lemmin, I.B.; van Schaik, J.R.; Hulsbergen, A.W.; Peters, R.A.; Pirok, B.W.; van Asten, A.C. Characterizing nitrocellulose by nitration degree and molecular weight: A user-friendly yet powerful forensic comparison meth-od for smokeless powders. Forensic Chem. 2025, 42, 100637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, D.; Iop, G.D.; Bizzi, C.A.; Mello, P.A.; Mesko, M.F.; Balbinot, F.P.; Flores, E.M.M. A single step ultrasound-assisted nitrocellulose synthesis from microcrystalline cellulose. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021, 72, 105453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gismatulina, Y.A.; Budaeva, V.V.; Sakovich, G.V. Nitrocellulose synthesis from Miscanthus cellulose. Propellants Explos. Pyrotech. 2018, 43, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishiyama, Y.; Sugiyama, J.; Chanzy, H.; Langan, P. Crystal structure and hydrogen bonding system in cellulose Iα from synchrotron X-ray and neutron fiber diffraction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 14300–14306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishiyama, Y.; Langan, P.; Chanzy, H. Crystal Structure and Hydrogen-Bonding System in Cellulose Iβ from Synchrotron X-ray and Neutron Fiber Diffraction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 9074–9082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, U.J.; Eom, S.H.; Wada, M. Thermal decomposition of native cellulose: Influence on crystallite size. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2010, 95, 778–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, A.D. Idealized powder diffraction patterns for cellulose polymorphs. Cellulose 2014, 21, 885–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, A.D. Increment in evolution of cellulose crystallinity analysis. Cellulose 2020, 27, 5445–5448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, S.; French, A.D.; Condon, B.D.; Concha, M. Segal crystallinity index revisited by the simulation of X-ray dif-fraction patterns of cotton cellulose Iβ and cellulose II. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 135, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleshina, L.A.; Gladysheva, E.K.; Budaeva, V.V.; Mironova, G.F.; Skiba, E.A.; Sakovich, G.V. X-ray diffraction data on the bacterial nanocellulose synthesized by Komagataeibacter xylinus B-12429 and B-12431 Microbial Producers in Miscanthus- and oat hull-derived enzymatic hydrolyzates. Crystallogr. Rep. 2022, 67, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gromyko, D.V.; Prusskii, A.I.; Tokko, O.V.; Kotel’nikova, N.E. Structural Study of Silver-modified Powder Lignocel-lulose by Computer Simulation of Atomic Structure. Russ. J. Bioorg. Chem. 2024, 50, 2765–2772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessa, W.; Trache, D.; Derradji, M.; Bentoumia, B.; Tarchoun, A.F.; Hemmouche, L. Effect of silane modified micro-crystalline cellulose on the curing kinetics, thermo-mechanical properties and thermal degradation of benzoxazine resin. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 180, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarchoun, A.F.; Trache, D.; Klapötke, T.M.; Krumm, B.; Mezroua, A.; Derradji, M.; Bessa, W. Design and characterization of new advanced energetic biopolymers based on surface functionalized cellulosic materials. Cellulose 2021, 28, 6107–6123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinzadeh, J.; Abdulkhani, A.; Ashori, A.; Dmirievich, P.S.; Abdolmaleki, H.; Hajiahmad, A.; Zadeh, Z.E. Comparative study on liquid versus gas phase hydrochloric acid hydrolysis for microcrystalline cellulose isolation from sugarcane bagasse. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 264, 130674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yasemin, S. Isolation and characterization of cellulose from spent ground coffee (Coffea arabica L.): A comparative study. Waste Manag. 2025, 193, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalmis, R.; Köktaş, S.; Seki, Y.; Kılınç, A.Ç. Characterization of a new natural cellulose based fiber from Hierochloe Odarata. Cellulose 2020, 27, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismaeilimoghadam, S.; Sepahvand, S.; Mahdavi, S.; Shahraki, A.; Jonoobi, M. Investigating the effect of bleaching (HEQPH) intensity on cellulose content, crystallinity, degree of polymerization, and physico-mechanical properties of bleached wheat straw and cotton linter fluff pulps. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 311, 143682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, M.; Fulchiron, R.; Gouanvé, F. Water Sorption and Mechanical Properties of Cellulosic Derivative Fibers. Polymers 2022, 14, 2836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montoya-Escobar, N.; Ospina-Acero, D.; Velásquez-Cock, J.A.; Gómez-Hoyos, C.; Serpa Guerra, A.; Gañan Rojo, P.F.; Stefani, P.M. Use of fourier series in X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis and fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) for estimation of crystallinity in cellulose from different sources. Polymers 2022, 14, 5199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trache, D.; Donnot, A.; Khimeche, K.; Benelmir, R.; Brosse, N. Physico-chemical properties and thermal stability of microcrystalline cellulose isolated from Alfa fibres. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014, 104, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarchoun, A.F.; Trache, D.; Klapötke, T.M.; Krumm, B.; Kofen, M. Synthesis and characterization of new insensitive and high-energy dense cellulosic biopolymers. Fuel 2021, 292, 120347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarchoun, A.F.; Trache, D.; Klapötke, T.M.; Abdelaziz, A.; Derradji, M.; Bekhouche, S. Chemical design and characterization of cellulosic derivatives containing high-nitrogen functional groups: Towards the next generation of energetic biopolymers. Def. Technol. 2021, 18, 537–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y. Cellulose. In The Handbook of Paper-Based Sensors and Devices: Volume 1: Materials and Technologies; Korotcenkov, G., Ed.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 73–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahim, K.S.A.; Samsur, A.; Jamal, S.H.; Nor, S.A.M.; Rusly, S.N.A.; Ariff, H.; Latif, N.S.A. Key attributes of nitrocellulose-based energetic materials and recent developments. Heliyon 2025, 11, e41282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bekhouche, S.; Trache, D.; Akbi, H.; Abdelaziz, A.; Tarchoun, A.F.; Boudouh, H. Thermal decomposition behavior and kinetic study of nitrocellulose in presence of ternary nanothermites with different oxidizers. FirePhysChem 2023, 3, 208–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample Name | * Mass Content, % | DP | Wettability, g | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α-Cellulose | Ash | ||||

| SC | 99.4 ± 0.4 | 0.24 ± 0.05 | 3140 ± 10 | 59 ± 5 | present study |

| CC (highest-grade) | (98.2–99.0) ± 0.4 | 0.10 ± 0.05 | (1000–5000) ± 10 | 150 ± 10 | [22] |

| CC (first grade) | (97.2–98.0) ± 0.4 | 0.20 ± 0.05 | (1000–5000) ± 10 | 140 ± 10 | [22] |

| CC | 98.0 ± 0.4 | no data | 2700 ± 10 | no data | [25] |

| WC S | 93.0 ± 0.4 | 0.16 ± 0.05 | (400–5500) ± 10 | 135 ± 10 | [22] |

| WC RP | 94.0 ± 0.4 | 0.20 ± 0.05 | (400–5500) ± 10 | no data | [22] |

| Sample Name | Actual Yield, % | Nitrogen Content, % | Viscosity of the 2% Solution in Acetone mPa·s (°E) | Solubility in Alcohol–Ether Solvent, % | Ash Content, % | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NC from SC | 138 ± 2 | 11.83 ± 0.05 | 198 ± 2 (32.4) | 91 ± 2 | 0.05 ± 0.01 | present study |

| “H”-type NC | ~142 | 11.75–12.09 | 8.5–12.3 (1.9–2.6) | at least 98 | at most 0.5 | [21] |

| Film NC | ~142 | 11.38–12.00 | 5–20 * | at least 99.2 | at most 0.3 | [21] |

| NC for spray paint | ~142 | 11.56–12.19 | 0.25–40 * | at least 98.5 | at most 0.2 | [21] |

| Commercial NC | no data | 12.50 | 42 ± 2 | no data | 0.19 | [32] |

| NC from commercial MCC | no data | 12.50 | 17 (3.2) | 90 | no data | [50] |

| NC from avocado seed-derived MCC | no data | 12.23 | no data | 90.36 ± 1.91 | 12.76 ± 1.99 | [1] |

| no data | 12.26 | no data | 93.28 ± 2.34 | 9.80 ± 2.20 |

| Sample | Geometry | a, Å | b, Å | c, Å | γ, ° | Rwp, % | Rp, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SC | reflection | 7.952(1) | 8.167(4) | 10.35(2) | 96.3(1) | 7.5 | 5.4 |

| transmission | 7.952(2) | 8.163(8) | 10.36(1) | 96.3(3) | 9.4 | 7.6 |

| Geometry | Reflection | Transmission | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CrI, % | 81 ± 5 | 86 ± 5 | |

| [hkl] | (hkl) | Dhkl, Å (Cauchy-Gauss average) | |

| 0 | 0 | 44 ± 5 | 43 ± 5 |

| 110 | 110 | 62 ± 5 | 63 ± 5 |

| 100 | 200 | 59 ± 5 | 58 ± 5 |

| 001 | 004 | 94 ± 5 | 93 ± 5 |

| Sample | CrI, % | Crystallite Size (Dhkl, Å) for Crystallographic Plane Spacings (dhkl, Å) and Diffraction Peaks (2θ) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SC-derived NC | 17 ± 5 | 29 ± 5 | 62 ± 5 | 26 ± 5 | 38 ± 5 |

| 7.38 ± 0.05 | 7.14 ± 0.05 | 4.82 ± 0.05 | 3.97 ± 0.05 | ||

| 12.00 | 12.40 | 18.40 | 22.40 | ||

| Sample Name | Actual Yield, % | Nitrogen Content, %/DP | Viscosity of the 2% Solution in Acetone mPa·s | Solubility in Alcohol–Ether Solvent, % | Ash Content, % | FT-IR Spectroscopy, cm−1 | TGA/DTA | CrI, %/Crystallite Sizes, Å | Morphology |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TOnset/TPeak, °C/Q, kJ/g | |||||||||

| NC from SC (SC DP of 3140) | 138 ± 2 | 11.83 ± 0.05/2.21 | 198 ± 2 | 91 ± 2 | 0.05 ± 0.01 | 1644, 1278, 832, 746, 662 | 200/208/7.74 | 17 ± 5/29 × 62 × 26 × 38 | NC fibers have a cylindrical shape with a diameter increasing to 25 µm; the surface is covered with numerous microcracks and roughness |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Budaeva, V.V.; Korchagina, A.A.; Gismatulina, Y.A.; Kashcheyeva, E.I.; Gorbatova, P.A.; Mironova, G.F.; Zolotukhin, V.N.; Bychin, N.V.; Lyukhanova, I.V.; Aleshina, L.A.; et al. Nitrates of Synthetic Cellulose. Polymers 2026, 18, 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010010

Budaeva VV, Korchagina AA, Gismatulina YA, Kashcheyeva EI, Gorbatova PA, Mironova GF, Zolotukhin VN, Bychin NV, Lyukhanova IV, Aleshina LA, et al. Nitrates of Synthetic Cellulose. Polymers. 2026; 18(1):10. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010010

Chicago/Turabian StyleBudaeva, Vera V., Anna A. Korchagina, Yulia A. Gismatulina, Ekaterina I. Kashcheyeva, Polina A. Gorbatova, Galina F. Mironova, Vladimir N. Zolotukhin, Nikolay V. Bychin, Inna V. Lyukhanova, Lyudmila A. Aleshina, and et al. 2026. "Nitrates of Synthetic Cellulose" Polymers 18, no. 1: 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010010

APA StyleBudaeva, V. V., Korchagina, A. A., Gismatulina, Y. A., Kashcheyeva, E. I., Gorbatova, P. A., Mironova, G. F., Zolotukhin, V. N., Bychin, N. V., Lyukhanova, I. V., Aleshina, L. A., & Sakovich, G. V. (2026). Nitrates of Synthetic Cellulose. Polymers, 18(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010010