CO2 Valorization by CH4 Tri-Reforming on Al2O3-Supported NiCo Nanoparticles

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Characterization of NiCo/γ-Al2O3 Catalysts

2.1.1. Fresh Samples

2.1.2. Used Samples

2.1.3. Raman Characterization

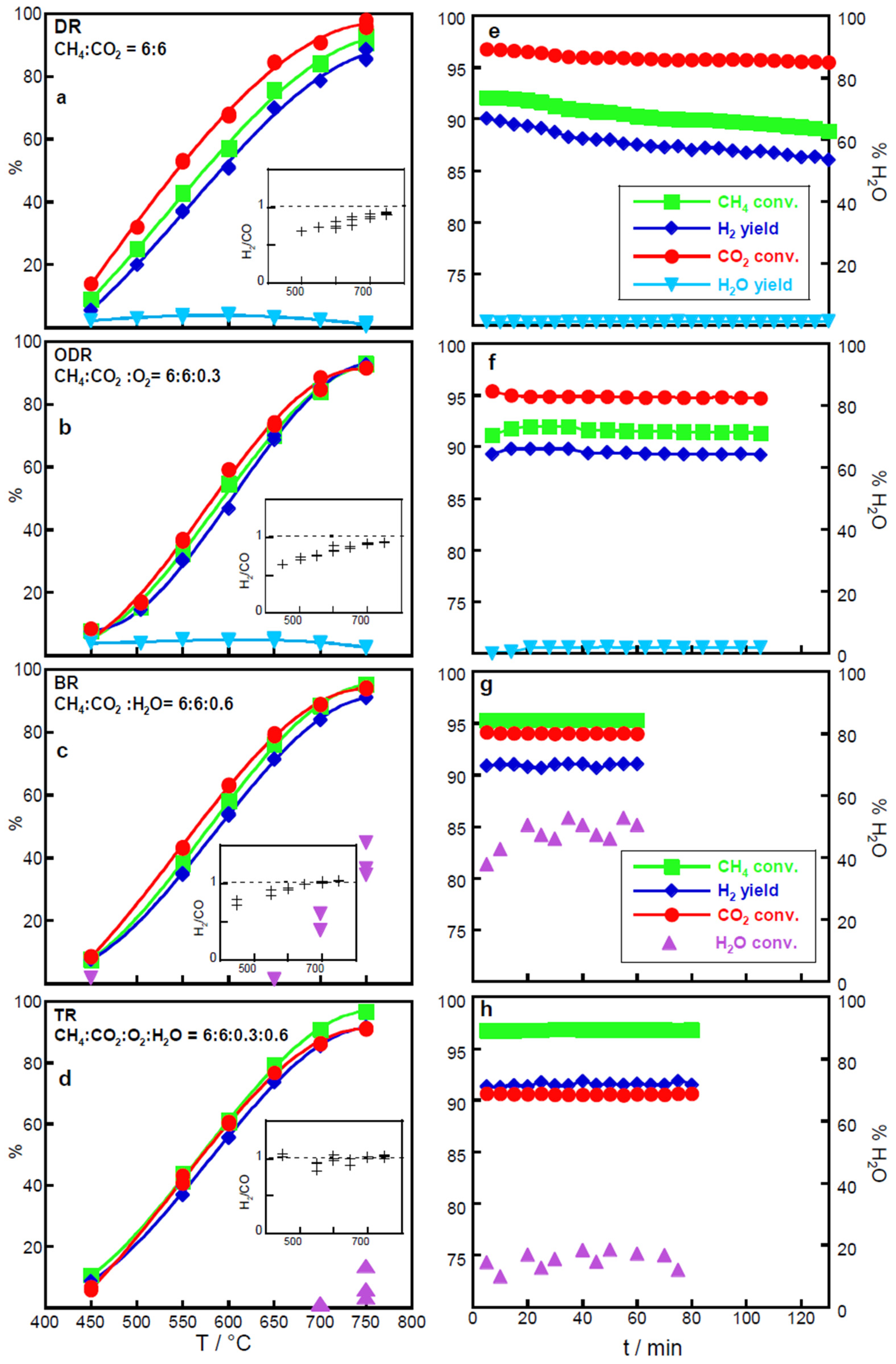

2.2. Catalytic Performances for CO2 Valorization Across Reforming Processes

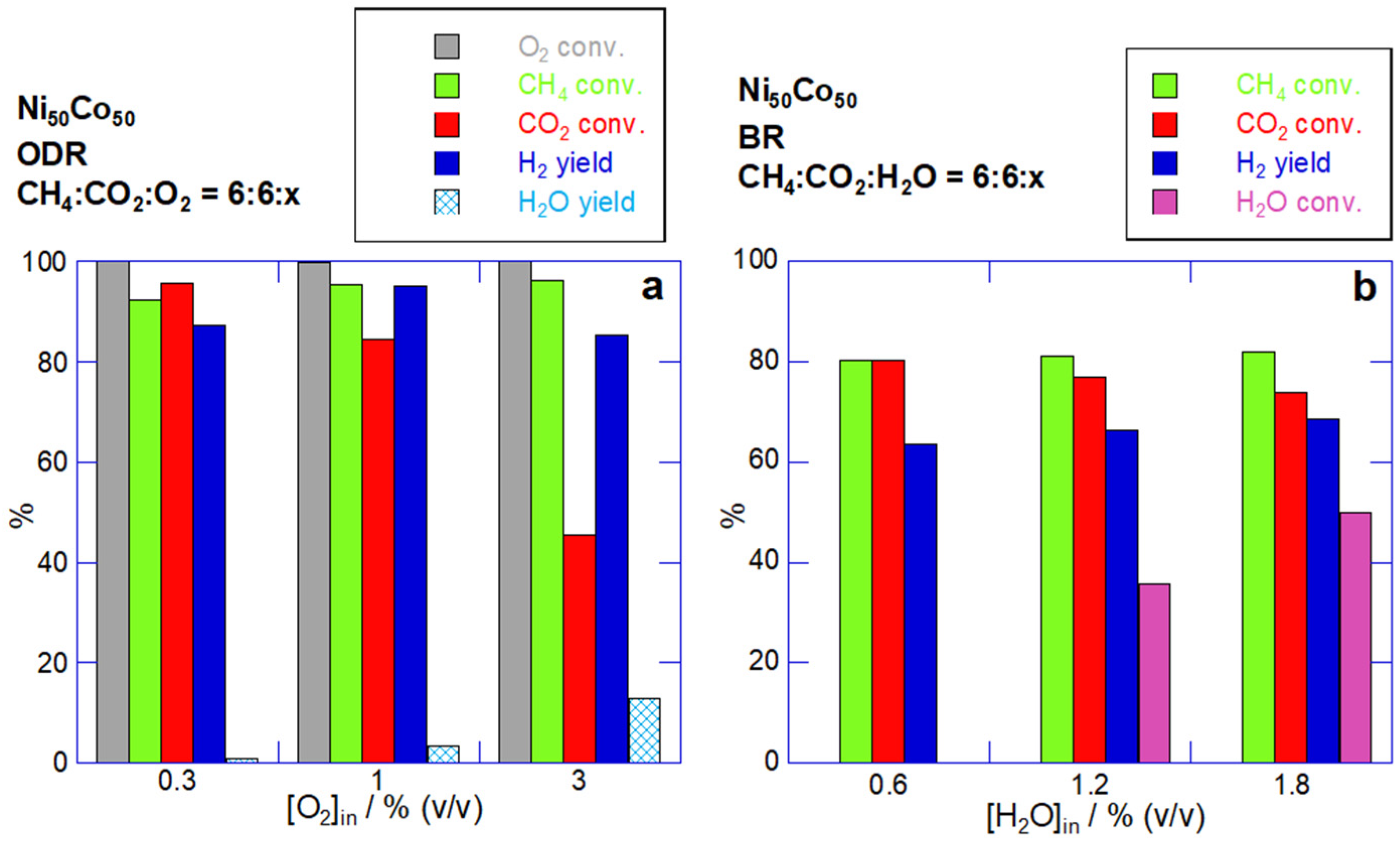

2.2.1. Effect of O2 and H2O Co-Reactants

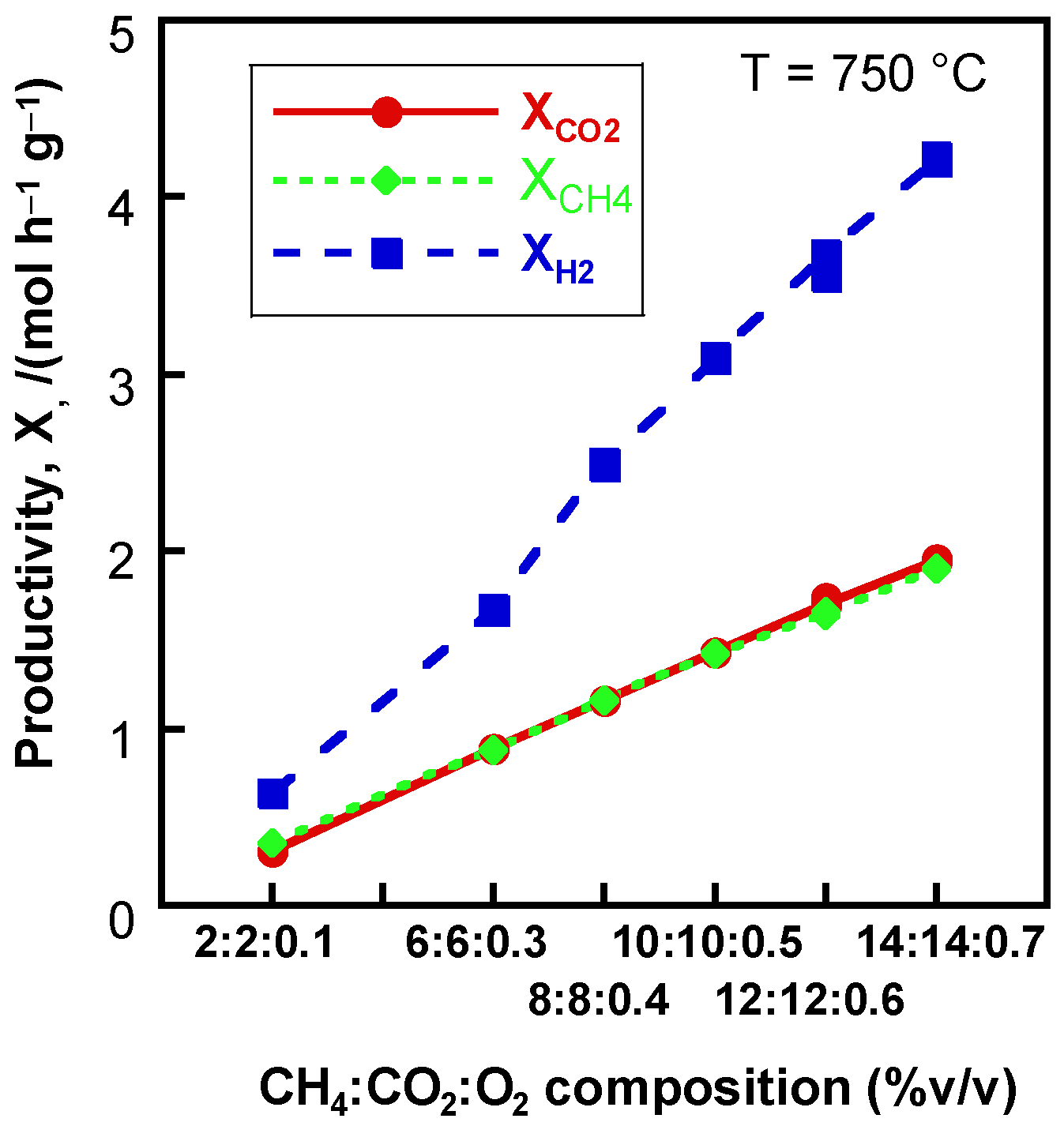

2.2.2. Effect of Feed Concentration and Contact Time

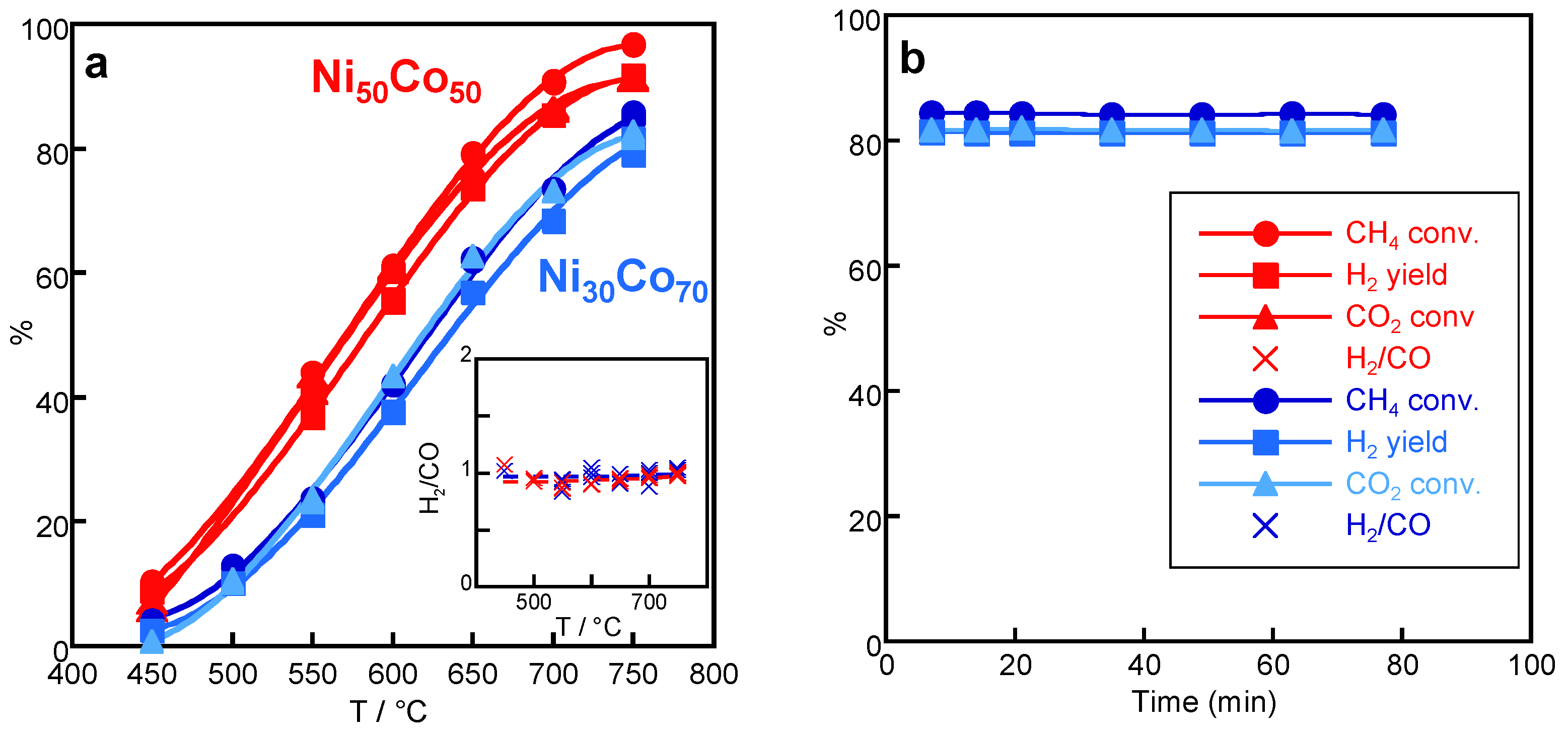

2.3. Catalytic Performances of NiCo Catalysts for CH4 Tri-Reforming (TR)

2.3.1. Effect of Reactant Mixture Composition

2.3.2. Effect of Ni/Co Ratio

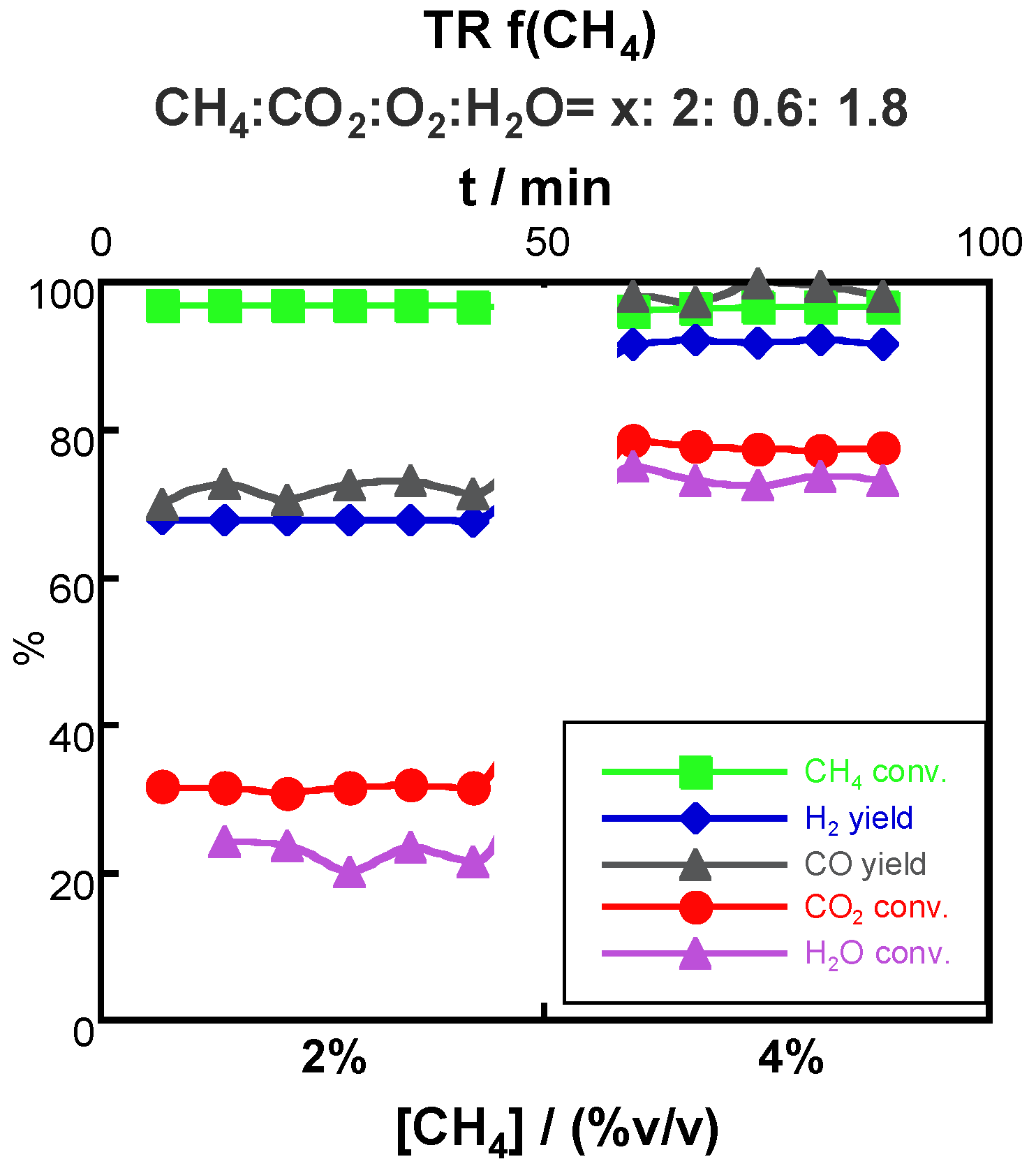

2.3.3. Effect of CH4 Content

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. Catalysts Characterization

3.3. Catalytic Activity Measurements

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, N.; Bai, Y.; Guo, Z.; Fan, Y.; Meng, F. Synergies between the circular economy and carbon emission reduction. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 951, 175603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olajire, A.A. Valorization of greenhouse carbon dioxide emissions into value-added products by catalytic processes. J. CO2 Util. 2013, 3-4, 74–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wei, Z.; Hao, D.; Jing, L.; Liu, Y.; Dai, H.; Wei, W.; Deng, J. Recent advances in synergistic catalytic valorization of CO2 and hydrocarbons by heterogeneous catalysis. Acta Phys.-Chim. Sin. 2025, 41, 100073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Pan, W. Tri-reforming of methane: A novel concept for catalytic production of industrially useful synthesis gas with desired H2/CO ratios. Catal. Today 2024, 98, 463–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soleimani, S.; Lehner, M. Tri-Reforming of Methane: Thermodynamics, Operating Conditions, Reactor Technology and Efficiency Evaluation-A Review. Energies 2022, 15, 7159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lino, A.V.P.; Assaf, E.M.; Assaf, J.M. Adjusting Process Variables in Methane Tri-reforming to Achieve Suitable Syngas Quality and Low Coke Deposition. Energy Fuels 2020, 34, 16522−16531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunkara, S.; Pankhedkar, N.; Gudi, R. Valorization of refinery flue gas through tri-reforming and direct hydrogenation routes. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 2024, 102, 2136–2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmal, M.; Toniolo, F.S.; Kozonoe, C.E. Perspective of catalysts for (Tri) reforming of natural gas and flue gas rich in CO2. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2018, 568, 23–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minh, D.P.; Pham, X.-H.; Siang, T.J.; Vo, D.-V.N. Review on the catalytic tri-reforming of methane—Part I: Impact of operating conditions, catalyst deactivation and regeneration. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2021, 621, 118202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, X.-H.; Ashik, U.P.M.; Hayashi, J.-I.; Alonso, A.P.; Pla, D.; Gómez, M.; Minh, D.P. Review on the catalytic tri-reforming of methane—Part II: Catalyst development. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2021, 623, 118286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alli, R.D.; de Souza, P.A.L.; Mohamedali, M.; Virla, L.D.; Mahinpey, N. Tri-reforming of methane for syngas production using Ni catalysts: Current status and future Outlook. Catal. Today 2023, 407, 107–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boakye, O.Y.; Hashemi, S.M.; Mahinpey, N. Investigation of Al2O3, ZrO2, SiO2, and CeO2 supported nickel catalysts for tri-reforming of Methane. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 109, 802–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Medeiros, F.G.M.; Lopes, F.W.B.; Lotfi, S.; de Vasconcelos, B.R. One-step upgrading of real flue gas streams into syngas over alumina-supported catalysts. Fuel 2023, 338, 127324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Hou, Z.; Liu, X.; Zeng, Y.; Luo, M.; Zheng, X. Methane autothermal reforming with CO2 and O2 to synthesis gas at the boundary between Ni and ZrO2. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2009, 34, 3734–3742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foo, S.Y.; Cheng, C.K.; Nguyen, T.-H.; Adesina, A.A. Oxidative CO2 Reforming of Methane on Alumina-Supported Co−Ni Catalyst. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2010, 21, 10450–10458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Fatesh, A.S.; Patel, N.; Fakeeha, A.H.; Alotibi, M.F.; Alreshaidan, S.B.; Kumar, R. Reforming of methane: Effects of active metals, supports, and promoters. Catal. Rev. 2024, 66, 2209–2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Li, Y.; Bai, J. Review article. Bimetallic Nickel-Cobalt catalysts and their application in dry reforming reaction of methane. Fuel 2024, 358, 130290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.N.; Li, D.; Tian, D.; Jiang, L.; Li, Z.; Wang, H.; Li, K. Optimization of Ni-Based Catalysts for Dry Reforming of Methane via Alloy Design: A Review. Energy Fuels 2022, 36, 5102−5151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, Z.; Das, S.; Wai, M.H.; Hongmanorom, P.; Kawi, S. A Review on Bimetallic Nickel-Based Catalysts for CO2 Reforming of Methane. ChemPhysChem 2017, 18, 3117–3134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Yang, B.; Miao, S.; Liu, W.; Xie, J.; Lee, S.; Pellin, M.J.; Xiao, D.; Su, D.; Ma, D. Lattice Strained Ni-Co Alloy as High-Performance Catalyst for Catalytic Dry-Reforming of Methane. ACS Catal. 2019, 9, 2693–2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horlyck, J.; Lawrey, C.; Lovell, E.C.; Amal, R.; Scott, J. Elucidating the impact of Ni and Co loading on the selectivity of bimetallic NiCo catalysts for dry reforming of methane. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 352, 572–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centi, G.; Perathoner, S. Catalysis for an electrified chemical production. Catal. Today 2023, 423, 113935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordet, A.; Leitner, W.; Chaudret, B. Magnetically Induced Catalysis: Definition, Advances, and Potential. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2025, 64, e202424151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chidhambaram, N.; Kay, S.J.J.; Priyadharshini, S.; Meenakshi, R.; Sakthivel, P.; Dhanbalan, S.; Shanavas, S.; Kamaraj, S.-K.; Thirumurugan, A. Magnetic Nanomaterials as Catalysts for Syngas Production and Conversion. Catalysts 2023, 13, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinum, M.G.; Almind, M.R.; Engbæk, J.S.; Vendelbo, S.B.; Hansen, M.F.; Frandsen, C.; Bendix, J.; Mortensen, P.M. Dual-Function Cobalt–Nickel Nanoparticles Tailored for High Temperature Induction-Heated Steam Methane Reforming. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2018, 57, 10569–10573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varsano, F.; Bellusci, M.; La Barbera, A.; Petrecca, M.; Albino, M.; Sangregorio, C. Dry reforming of methane powered by magnetic induction. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 21037–21044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarfiello, C.; Bellusci, M.; Pilloni, L.; Pietrogiacomi, D.; La Barbera, A.; Varsano, F. Supported catalysts for induction-heated steam reforming of methane. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 134–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poletto Dotsenko, V.; Bellusci, M.; Masi, A.; Pietrogiacomi, D.; Varsano, F. Improving the performances of supported NiCo catalyst for reforming of methane powered by magnetic induction. Catal. Today 2023, 418, 114049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malandrino, S.; Bellusci, M.; Campa, M.C.; Pietrogiacomi, D.; Varsano, F. Bi-reforming of Methane Powered by Induction heating on Supported Magnetic NiCo Nanoparticles. Emerg. Mater. 2026, unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Varsano, F.; Bellusci, M.; Provino, A.; Petrecca, M. NiCo as catalyst for magnetically induced dry reforming of methane. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 323, 012005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divi, S.; Chatterjee, A. Generalized nano-thermodynamic model for capturing size-dependent surface segregation in multi-metal alloy nanoparticles. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 10409–10424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, K.-J.; Plant, S.R.; Ellis, P.R.; Brown, C.M.; Bishop, P.T.; Palmer, R.E. Atomic Resolution Observation of a Size-Dependent Change in the Ripening Modes of Mass-Selected Au Nanoclusters Involved in CO Oxidation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 15161−15168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjiev, V.G.; Iliev, M.N.; Vergilov, I.V. The Raman spectra of Co3O4. J. Phys. C Solid State Phys. 1988, 21, L199–L201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mironova-Ulmane, N.; Kuzmin, A.; Steins, I.; Grabis, J.; Sildos, I.; Pärs, M. Raman scattering in nanosized nickel oxide NiO. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2007, 93, 012039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bala, N.; Singh, H.K.; Verma, S.; Rath, S. Magnetic-order induced effects in nanocrystalline NiO probed by Raman spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. B 2020, 102, 024423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, R.; Versluis, C.; Frijsen, R.; Prins, P.T.; Vogt, E.T.C.; Rabouw, F.T.; Weckhuysen, B.M. The Coking of a Solid Catalyst Rationalized with Combined Raman and Fluorescence Lifetime Microscopy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202409503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Park, E.D. Recent Advances in Coke Management for Dry Reforming of Methane over Ni-Based Catalysts. Catalysts 2024, 14, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczygieł, J.; Postawa, K.; Chojnacka, K.; Skrzypczak, D.; Izydorczyk, G.; Kułażyński, M. Thermodynamical Analysis and Optimization of Dry Reforming and Trireforming of Greenhouse Gases: A Statistical Approach. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 33536–33547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halmann, M.; Steinfeld, A. Thermoneutral tri-reforming of flue gases from coal- and gas-fired power stations. Catal. Today 2006, 115, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jilani, S.; Kumar, A. Simulation of Tri-Reforming Reaction Using Flue Gases of Thermal Power Plant (Natural Gas Fired). Inter. J. Appl. Eng. Res. 2020, 15, 953–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, C.A.; Rasband, W.S.; Eliceiri, K.W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 671–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergeret, G.; Gallezot, P. Particle size and dispersion measurement. In Handbook of Heterogeneous Catalysis; Ertl, G., Knozinger, H., Weitkamp, J., Eds.; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 1997; Volume 2, pp. 439–464. [Google Scholar]

| Sample | S.A. (m2/g) a | Vtot (cm3/g) b | %wttot (AAS) | Ni/Co (AAS) | dXRD/ (nm) | dSEM (nm) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ni50Co50 | Fresh | 145 | 0.51 | 24.2 | 51:49 | 30 | 37 |

| Used | 37 | 51 | |||||

| Ni30Co70 | Fresh | 140 | 0.51 | 24.4 | 31:69 | 40 | 42 |

| Used | 26 | 67 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pietrogiacomi, D.; Caponera, C.; Leone, M.; Campa, M.C.; Bellusci, M.; Varsano, F. CO2 Valorization by CH4 Tri-Reforming on Al2O3-Supported NiCo Nanoparticles. Catalysts 2026, 16, 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010062

Pietrogiacomi D, Caponera C, Leone M, Campa MC, Bellusci M, Varsano F. CO2 Valorization by CH4 Tri-Reforming on Al2O3-Supported NiCo Nanoparticles. Catalysts. 2026; 16(1):62. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010062

Chicago/Turabian StylePietrogiacomi, Daniela, Chiara Caponera, Michele Leone, Maria Cristina Campa, Mariangela Bellusci, and Francesca Varsano. 2026. "CO2 Valorization by CH4 Tri-Reforming on Al2O3-Supported NiCo Nanoparticles" Catalysts 16, no. 1: 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010062

APA StylePietrogiacomi, D., Caponera, C., Leone, M., Campa, M. C., Bellusci, M., & Varsano, F. (2026). CO2 Valorization by CH4 Tri-Reforming on Al2O3-Supported NiCo Nanoparticles. Catalysts, 16(1), 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010062