Esterification of Free Fatty Acids Under Heterogeneous Catalysis Using Ultrasound

Abstract

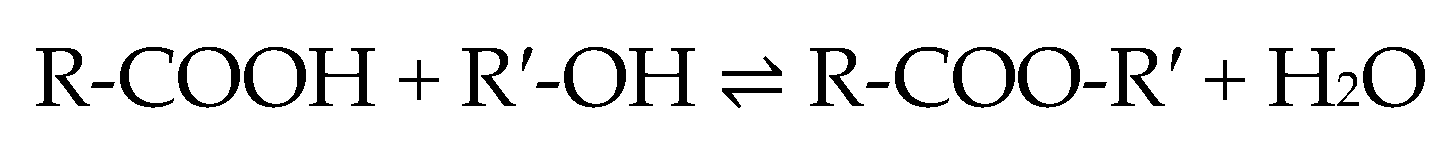

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Comparison Between the Catalysts from Different Sources

2.1.1. Structure and Morphology Characterization

2.1.2. The Effect of Particle Size of the WS2 from Various Sources on the Yield of Esterification Reaction

2.2. Effect of WS2 Concentration on the Reaction Yield

2.3. Effect of FFAs-to-Methanol Molar Ratio on the Reaction Yield

2.3.1. Screening of FFAs-to-Methanol Molar Ratio Under Ultrasonic Activation Without External Heating

2.3.2. Temperature-Controlled Esterification

2.4. The Effect of the Reaction Time

2.5. Esterification Under Ultrasonic and Thermal Activation

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. Methods

3.2.1. Catalyst Characterization

3.2.2. Ultrasound-Assisted Esterification

3.2.3. Product Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FFA | Free Fatty Acids |

| NP | Nanoparticles |

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscope |

| TEM | Transmission Electron Microscope |

| WS2 | Tungsten Disulfide |

| XRD | X-Ray Diffraction |

References

- Anil, N.; Rao, P.K.; Sarkar, A.; Kubavat, J.; Vadivel, S.; Manwar, N.R.; Paul, B. Advancements in sustainable biodiesel production: A comprehensive review of bio-waste derived catalysts. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 318, 118884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramasamy, D.; Hasan, M.A.; AbdulRTh, A.Z. Biodiesel and Its Potential to Mitigate Transport-Related CO2 Emissions. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2023, 25, 2281–2293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeswani, H.K.; Chilvers, A.; Azapagic, A. Environmental Sustainability of Biofuels: A Review. Proc. R. Soc. A 2020, 476, 20200351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreo-Martínez, P.; Ortiz-Martínez, V.M.; Salar-García, M.J.; Quesada-Medina, J.; Hernández-Fernández, F.J. Waste Animal Fats as Feedstock for Biodiesel Production Using Non-Catalytic Supercritical Alcohol Transesterification: A Perspective by the PRISMA Methodology. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2022, 69, 150–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha-Meneses, L.; Hari, A.; Inayat, A.; Yousef, L.A.; Alarab, S.; Abdallah, M.; Shanableh, A.; Ghenai, C.; Shanmugam, S.; Kikas, T. Recent Advances on Biodiesel Production from Waste Cooking Oil (WCO): A Review of Reactors, Catalysts, and Optimization Techniques Impacting the Production. Fuel 2023, 348, 128514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farouk, S.M.; Tayeb, A.M.; Abdel-Hamid, S.M.S.; Osman, R.M. Recent Advances in Transesterification for Sustainable Biodiesel Production, Challenges, and Prospects: A Comprehensive Review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 12722–12747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camilo, G.L.; Queiroz, A.; Ribeiro, A.E.; Gomes, A.; Brito, P. Review of biodiesel production using various feedstocks and its purification through several methodologies, with a specific emphasis on dry washing. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2024, 136, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, M.; Rokhum, S.L.; Ma, X.; Wang, T.; Li, H.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, Y.; Li, H. Recent advances of biodiesel production enhanced by external field via heterogeneous catalytic transesterification system. Chem. Eng. Process.–Process Intensif. 2024, 205, 109997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, M.C.; Liao, P.-H.; Lan, N.V.; Hou, S.S. Enhancement of Biodiesel Production from High-Acid-Value Waste Cooking Oil via a Microwave Reactor Using a Homogeneous Alkaline Catalyst. Energies 2021, 14, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekonnen, K.D.; Degefa, T.H.; Rachapudi, V.S.P.; Kumar, N. NaOH-Catalyzed Methanolysis Optimization of Biodiesel Production from Waste Cooking Oil. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 25256–25266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A.A.; Smith, J.D. Investigation of Microwave-Assisted Transesterification Reactor of Waste Cooking Oil. Renew. Energy 2020, 162, 1735–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhtar, A.; Saqib, S.; Lin, H. Current Status and Challenges in the Heterogeneous Catalysis for Biodiesel Production. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 157, 112012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, N.; Patra, M.; Halder, G. Current Advances and Future Outlook of Heterogeneous Catalytic Transesterification towards Biodiesel Production from Waste Cooking Oil. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2024, 8, 1105–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, B.O.; Oladepo, S.A.; Ganiyu, S.A. Efficient and Sustainable Biodiesel Production via Transesterification: Catalysts and Operating Conditions. Catalysts 2024, 14, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A.S.I.; Gözmen, B.; Sönmez, Ö. Esterification of oleic acid using CoFe2O4@MoS2 solid acid catalyst under microwave irradiation. Fuel 2024, 371, 131988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Li, B.; Li, H.; Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Zhao, B.; Zhang, X.; Wang, J. The efficient and green synthesis of biodiesel from crude oil without degumming catalyzed by sodium carbonate supported MoS2. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 24456–24464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, V.C.; Durndell, L.J.; Isaacs, M.A.; Parlett, C.M.A.; Wilson, K.; Lee, A.F. A new application for transition metal chalcogenides: WS2 catalysed esterification of carboxylic acids. Catal. Commun. 2017, 9, 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivanesh, S.; Aswin, K.N.; Antony, A.; Varma, M.S.; Kamalesh, K.; Naageshwaran, M.; Soundarya, S.; Subramanian, S. Biodiesel Production from Custard Apple Seeds and Euglena sanguinea Using CaO Nano-Catalyst. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 344, 126418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, J.; Huang, X.; Choi, S.; Zhu, R.; Tang, S.; Bond, J.Q.; Tavlarides, L.L. Heterogeneous Catalytic Esterification of Oleic Acid under Sub/Supercritical Methanol over γ-Al2O3. Fuel 2020, 268, 117359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chipurici, P.; Vlaicu, A.; Călinescu, I.; Vinatoru, M.; Vasilescu, M.; Ignat, N.D.; Mason, T.J. Ultrasonic, Hydrodynamic and Microwave Biodiesel Synthesis: A Comparative Study for Continuous Process. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2019, 57, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruatpuia, J.V.L.; Halder, G.; Mohan, S.; Gurunathan, B.; Li, H.; Chai, F.; Basumatary, S.; Rokhum, S.L. Microwave-Assisted Biodiesel Production Using ZIF-8 MOF-Derived Nanocatalyst: Process Optimization, Kinetics, Thermodynamics, and Life-Cycle Cost Analysis. Energy Convers. Manag. 2023, 292, 117418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomanbhay, S.; Ong, M.Y. A Review of Microwave-Assisted Reactions for Biodiesel Production. Bioengineering 2017, 4, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korkut, I.; Bayramoğlu, M. Selection of Catalyst and Reaction Conditions for Ultrasound-Assisted Biodiesel Production from Canola Oil. Renew. Energy 2018, 116, 543–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malani, R.S.; Shinde, V.; Ayachit, S.; Goyal, A.; Moholkar, V.S. Ultrasound-Assisted Biodiesel Production Using Heterogeneous Base Catalyst and Mixed Non-Edible Oils. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2019, 52, 232–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Kodgire, P.; Kachhwaha, S.S. Investigation of Ultrasound-Assisted KOH and CaO Catalyzed Transesterification for Biodiesel Production from Waste Cotton-Seed Cooking Oil: Process Optimization and Conversion Rate Evaluation. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 259, 120982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veljković, V.B.; Avramović, J.; Stamenković, O.S. Biodiesel production by ultrasound-assisted transesterification: State of the art and the perspectives. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2012, 16, 1193–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolet, M.; Zerbib, D.; Nakonechny, F.; Nisnevitch, M. Production of Biodiesel from Brown Grease. Catalysts 2020, 10, 1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolet, M.; Atrash, M.; Molina, K.; Zerbib, D.; Albo, Y.; Nakonechny, F.; Nisnevitch, M. Sol-Gel Entrapped Lewis Acids as Catalysts for Biodiesel Production. Molecules 2020, 25, 5936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atrash, M.; Molina, K.; Sharoni, E.-O.; Azwat, G.; Nisnevitch, M.; Albo, Y.; Nakonechny, F. Toward Efficient Continuous Production of Biodiesel from Brown Grease. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, J.; Ji, M.; Jiao, P.; Yin, Z.; Xia, Q.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, J.; Pan, H. Heterogeneous Acid Catalysts for Biodiesel Production: Effect of Physicochemical Properties on Their Activity and Reusability. Catalysts 2025, 15, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, P.; Stelmachowski, P.; Broś, P.; Makowski, W.; Kotarba, A. Demonstration of the Influence of Specific Surface Area on Reaction Rate in Heterogeneous Catalysis. J. Chem. Educ. 2021, 98, 935–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caballero, K.V.; Guerrero-Amaya, H.; Baldovino-Medrano, V.G. Revisiting Glycerol Esterification with Acetic Acid over Amberlyst-35 via Statistically Designed Experiments: Overcoming Transport Limitations. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2019, 207, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenne, R.; Margulis, L.; Genut, M.; Hodes, G. Polyhedral and Cylindrical Structures of Tungsten Disulphide. Nature 1992, 360, 444–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenne, R. Inorganic Nanotubes and Fullerene-Like Nanoparticles. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2006, 1, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Levi, R.; Cohen, S.R.; Tenne, R. Gold Nanoparticles as Surface Defect Probes for WS2 Nanostructures. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2010, 1, 540–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhowalla, M.; Amaratunga, G.A.J. Thin Films of Fullerene-like MoS2 Nanoparticles with Ultra-Low Friction and Wear. Nature 2000, 407, 164–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voiry, D.; Yang, J.; Chhowalla, M. Recent Strategies for Improving the Catalytic Activity of 2D TMD Nanosheets toward the Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 6197–6206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erchamo, Y.S.; Mamo, T.T.; Workneh, G.A.; Mekonnen, Y.S. Improved biodiesel production from waste cooking oil with mixed methanol-ethanol using enhanced eggshell-derived CaO nano-catalyst. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 6708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attari, A.; Abbaszadeh-Mayvan, A.; Taghizadeh-Alisaraie, A. Process optimization of ultrasonic-assisted biodiesel production from waste cooking oil using waste chicken eggshell-derived CaO as a green heterogeneous catalyst. Biomass Bioenergy 2022, 158, 106357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, S.H.Y.S.; Hanapi, N.H.M.; Azid, A.; Umar, R.; Juahir, H.; Khatoon, H.; Endut, A. A review of biomass-derived heterogeneous catalyst for a sustainable biodiesel production. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev. 2017, 70, 1040–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgharbawy, A.S.; Osman, A.I.; El Demerdash, A.G.M.; Sadik, W.A.; Kasaby, M.A.; Ali, S.E. Enhancing Biodiesel Production Efficiency with Industrial Waste-Derived Catalysts: Techno-Economic Analysis of Microwave and Ultrasonic Transesterification Methods. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 321, 118945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, L.S.G.; Assis, J.C.R.; Mendonça, D.R.; Santos, I.T.V.; Guimarães, P.R.B.; Pontes, L.A.M.; Teixeira, J.S. Comparison between Conventional and Ultrasonic Preparation of Beef Tallow Biodiesel. Fuel Process. Technol. 2009, 90, 1164–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thawornprasert, J.; Somnuk, K. Two-Step Esterification Process of Palm Fatty Acid Distillate Using Soaking Coupled with Ultrasound: Process Optimization and Reusable Solid Acid Catalysts. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 50427–50438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaz, L.M.O.; Martins, M.I.; Filho, U.C.; Cardoso, V.L.; Reis, M.H.M. Ultrasound-assisted transesterification reactions for biodiesel production with sodium zirconate supported in polyvinyl alcohol as catalyst. Environ. Prog. 2017, 36, 1262–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malani, R.S.; Singh, S.; Goyal, A.; Moholkar, V.S. Ultrasound-Assisted Biodiesel Production Using KI-Impregnated Zinc Oxide (ZnO) as Heterogeneous Catalyst: A Mechanistic Approach. In Conference Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Recent Advances in Bioenergy Research; Springer: Singapore, 2016; pp. 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A.K.; Khan, M.E.; Pal, A.; Singh, B. Ultrasonic-assisted optimization of biodiesel production from Karabi oil using heterogeneous catalyst. Biofuels 2016, 9, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| WS2 Lot | Particles Size | Reaction Yield, % |

|---|---|---|

| Sample A | 2 µm | 20.0 ± 1.4 |

| Sample B | 2 µm | 18.2 ± 1.5 |

| Sample C | 90 nm | 14.3 ± 1.7 |

| Sample D | 90 nm | 7.1 ± 0.9 |

| Catalyst | Catalyst Loading | Feedstock | Acid-to-Methanol Ratio | Temperature (°C) | Time | Ultrasonication Conditions | Yield (%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WS2 | 16 wt% | Oleic + linoleic acids (85:15) | 1:15 | 75 | 1 h | US bath, 80 kHz, 320 W | 95 | This study |

| Amberlyst-15 | 60 wt% | Palm FFA distillate | 36 wt% FFA | 60 | 130 min soak + 8.5 min US | US horn, 18 kHz, 1000 W | 89 | [43] |

| Na2ZrO3/PVA film | 3 wt% | Soybean oil | 1:6 | 55 | 8 h | US bath, 25 kHz, 360 W | 80 | [44] |

| KI–ZnO | 6 wt% | Soybean oil | 1:10 | 82 | 40 min | US bath, 35 kHz, 35 W | 95 | [45] |

| CaO | 5 wt% | Karabi seed oil | 1:12 | 60 | 2 h | US horn, 20–30 kHz, 50 W | 94 | [46] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Semenova, O.; Dargie, Z.A.; Yadgarov, L.; Nakonechny, F.; Nisnevitch, M. Esterification of Free Fatty Acids Under Heterogeneous Catalysis Using Ultrasound. Catalysts 2025, 15, 1161. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121161

Semenova O, Dargie ZA, Yadgarov L, Nakonechny F, Nisnevitch M. Esterification of Free Fatty Acids Under Heterogeneous Catalysis Using Ultrasound. Catalysts. 2025; 15(12):1161. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121161

Chicago/Turabian StyleSemenova, Olga, Zinabu Adhena Dargie, Lena Yadgarov, Faina Nakonechny, and Marina Nisnevitch. 2025. "Esterification of Free Fatty Acids Under Heterogeneous Catalysis Using Ultrasound" Catalysts 15, no. 12: 1161. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121161

APA StyleSemenova, O., Dargie, Z. A., Yadgarov, L., Nakonechny, F., & Nisnevitch, M. (2025). Esterification of Free Fatty Acids Under Heterogeneous Catalysis Using Ultrasound. Catalysts, 15(12), 1161. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121161