Nonmetallic Heteroatom Engineering in Copper-Based Electrocatalysts: Advances in CO2 Reduction

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Nonmetallic Heteroatom Doping

2.1. Nitrogen (N) Doping

2.1.1. N Doping into Carbon Support

2.1.2. N Doping into Cu-Based Catalyst

2.2. Sulfur (S) Doping

2.3. Boron (B) Doping

2.4. Phosphorus (P) Doping

2.5. Halogen Doping

3. Nonmetal-Heteroatom-Functionalized Ligands

4. Conclusions and Outlook

4.1. Current Challenges and Outlook for Heteroatom-Doped Copper-Based Catalysts

4.2. Key Challenges in Heteroatom Functionalization of Ligands

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HER | hydrogen evolution reactions |

| CO2RR | electrochemical carbon dioxide reduction |

| CCS | carbon capture and storage |

| AFM | atomic force microscopy |

| XAS | X-ray absorption spectroscopy |

| XANES | X-ray absorption near edge structure |

| XPS | X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy |

| FTIR | Fourier Transform infrared spectroscopy |

| DFT | Density functional theory |

| FE | Faradaic efficiency |

| EE | energy efficiency |

| VO | oxygen vacancies |

| OC | open circuit |

| Cu-N-C | copper-based nitrogen-doped carbon |

| SWCNTs | single-walled carbon nanotubes |

| PDOS | Projected density of states |

| LSN-Cu | lattice-strain-stabilized N-doped Cu |

| HFB | high-frequency band |

| LFB | low-frequency band |

| ATR-FTIR | attenuated total reflection Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy |

| SERS | surface-enhanced Raman scattering |

| SM-OD-Cu | sulfur-modified polycrystalline Cu and oxide-derived Cu electrodes |

| CSVE | core–shell-vacancy engineering |

| MOF | Metal–organic framework |

| h-BN | hexagonal boron nitride |

| HF | hollow-fiber penetration electrode |

| TEM | Transmission Electron Microscopy |

| HOMO | highest occupied molecular orbital |

| GDEs | gas diffusion electrodes |

References

- Jia, S.; Ma, X.; Sun, X.; Han, B. Electrochemical Transformation of CO2 to Value-Added Chemicals and Fuels. CCS Chem. 2022, 4, 3213–3229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Pérez-Ramírez, J.; Gong, J.; Dewangan, N.; Hidajat, K.; Gates, B.C.; Kawi, S. Core–shell structured catalysts for thermocatalytic, photocatalytic, and electrocatalytic conversion of CO2. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020, 49, 2937–3004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, Z.; He, X.; Lin, R. Electrochemical Carbon Dioxide Reduction in Acidic Media. Electrochem. Energy Rev. 2024, 7, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Chen, X.; Liu, J.; Guan, J. Advances in the CO2 electroreduction to multi-carbon products. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 516, 164199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.-H. The doping–defect interplay in carbon capturing materials: From atomic design to practical feasibility. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2026, 226, 116485. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, H.; Tian, J.; Jiang, M.; Wu, D. Dynamic valence engineering of CuOx catalysts for selective and stable CO2 electroreduction to ethylene and ethanol. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Rep. 2025, 166, 101060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jouny, M.; Luc, W.; Jiao, F. General Techno-Economic Analysis of CO2 Electrolysis Systems. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2018, 57, 2165–2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luna, P.; Hahn, C.; Higgins, D.; Jaffer, S.A.; Jaramillo, T.F.; Sargent, E.H. What would it take for renewably powered electrosynthesis to displace petrochemical processes? Science 2019, 364, eaav3506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Xia, C.; Yang, F.; Wang, J.; Wang, H.; Lu, Y. Strategies in catalysts and electrolyzer design for electrochemical CO2 reduction toward C2+ products. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaav3111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, C.; Wang, X.; He, C.; Qi, R.; Zhu, D.; Lu, R.; Li, F.-M.; Chen, Y.; Chen, S.; You, B.; et al. Highly Selective Electrocatalytic CO2 Conversion to Tailored Products through Precise Regulation of Hydrogenation and C-C Coupling. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 20530–20538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luc, W.; Fu, X.; Shi, J.; Lv, J.-J.; Jouny, M.; Ko, B.H.; Xu, Y.; Tu, Q.; Hu, X.; Wu, J.; et al. Two-dimensional copper nanosheets for electrochemical reduction of carbon monoxide to acetate. Nat. Catal. 2019, 2, 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seh, Z.W.; Kibsgaard, J.; Dickens, C.F.; Chorkendorff, I.; Nørskov, J.K.; Jaramillo, T.F. Combining theory and experiment in electrocatalysis: Insights into materials design. Science 2017, 355, eaad4998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möller, T.; Scholten, F.; Thanh, T.N.; Sinev, I.; Timoshenko, J.; Wang, X.; Jovanov, Z.; Gliech, M.; Roldan Cuenya, B.; Varela, A.S.; et al. Electrocatalytic CO2 Reduction on CuOx Nanocubes: Tracking the Evolution of Chemical State, Geometric Structure, and Catalytic Selectivity using Operando Spectroscopy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 17974–17983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Fu, J.; Zhou, Y.; Chang, Y.-C.; Min, Q.; Zhu, J.-J.; Lin, Y.; Zhu, W. Insights on forming N, O-coordinated Cu single-atom catalysts for electrochemical reduction CO2 to methane. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, R.; Zhu, H.; Yang, F.; Ju, M.; Huang, X.; Wang, J.; Gu, M.D.; Gao, J.; Yang, S. The Proximal Protonation Source in Cu-NHx-C Single Atom Catalysts Selectively Boosts CO2 to Methane Electroreduction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2025, 64, e202424098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, W.; Yang, J.; Chen, H.; Hou, Y.; Wang, Q.; Gu, M.; He, F.; Xia, Y.; Xia, Z.; Li, Z. Atomically defined undercoordinated active sites for highly efficient CO2 electroreduction. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 1907658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, F.; Fang, L.; Li, B.; Yang, X.; O’Carroll, T.; Li, H.; Li, T.; Wang, G.; Chen, K.-J.; Wu, G. N and OH-Immobilized Cu3 Clusters In Situ Reconstructed from Single-Metal Sites for Efficient CO2 Electromethanation in Bicontinuous Mesochannels. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 1423–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Zhi, X.; Vasileff, A.; Wang, D.; Jin, B.; Jiao, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Qiao, S.-Z. Highly selective two-electron electrocatalytic CO2 reduction on single-atom Cu catalysts. Small Struct. 2021, 2, 2000058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Jing, W.; Bai, S.; Liu, Y.; Guo, L. Enhanced formate production from sulfur modified copper for electrocatalytic CO2 reduction. Energy 2024, 313, 133817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.J.; Si, D.H.; Sun, P.P.; Dong, Y.L.; Zheng, S.; Chen, Q.; Ye, S.H.; Sun, D.; Cao, R.; Huang, Y.B. Atomically Precise Copper Nanoclusters for Highly Efficient Electroreduction of CO2 towards Hydrocarbons via Breaking the Coordination Symmetry of Cu Site. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202306822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Yuan, Y.; Qu, G.; Xiang, K.; Ning, P.; Du, W.; Pan, K.; Cai, Y.; Li, J. Preparation of phosphorus-doped Cu-based catalysts by electrodeposition modulates* CHxO adsorption to facilitate electrocatalytic reduction of CO2 to CH4. Appl. Catal. B Environ. Energy 2025, 360, 124525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, H.; Liu, Y.; Jang, J.; Qiu, X.; Delmo, E.P.; Zhao, Q.; Gao, P.; Shao, M. A sulfur-doped copper catalyst with efficient electrocatalytic formate generation during the electrochemical carbon dioxide reduction reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202313858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, C.; Xue, W.; Zhang, M.; Zhao, D.; Xue, J.; Li, J.; Luo, L.; Liu, C. Manipulating local coordination of copper single atom catalyst enables efficient CO2-to-CH4 conversion. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 3382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Downes, C.A.; Libretto, N.J.; Harman-Ware, A.E.; Happs, R.M.; Ruddy, D.A.; Baddour, F.G.; Ferrell, J.R., III; Habas, S.E.; Schaidle, J.A. Electrocatalytic CO2 reduction over Cu3P nanoparticles generated via a molecular precursor route. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2020, 3, 10435–10446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, K.; Shen, F.; Fu, Y.; Wu, L.; Wang, Z.; Yi, H.; Liu, X.; Wang, P.; Liu, M.; Lin, Z.; et al. Boosting CO2 electroreduction towards C2+ products via CO* intermediate manipulation on copper-based catalysts. Environ. Sci. Nano 2022, 9, 911–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, P.; Yang, Z.; Jin, Y.; Li, S.; Hao, Y.; Duan, Y.; Huang, W.; Liu, L.; Yan, K.; Abudula, A. Surface Behavior Regulation of Intermediates on the Copper-Based Catalysts for Enhancing Electrocatalytic CO2 Reduction to Ethylene. Small 2025, 21, e10845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Bian, L.; Tian, H.; Liu, Y.; Bando, Y.; Yamauchi, Y.; Wang, Z.L. Tailoring the Surface and Interface Structures of Copper-Based Catalysts for Electrochemical Reduction of CO2 to Ethylene and Ethanol. Small 2022, 18, e2107450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, W.; He, X.; Wang, W.; Xie, S.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Y. Electrocatalytic reduction of CO2 and CO to multi-carbon compounds over Cu-based catalysts. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 12897–12914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, W.; Zhou, H.; Yang, P.; Huang, H.; Tian, J.; Ratova, M.; Wu, D. Pulse Manipulation on Cu-Based Catalysts for Electrochemical Reduction of CO2. ACS Catal. 2024, 14, 13697–13722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Yu, H.; Chow, Y.L.; Webley, P.A.; Zhang, J. Toward Durable CO2 Electroreduction with Cu-Based Catalysts via Understanding Their Deactivation Modes. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2403217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; She, X.; Yu, Q.; Zhu, X.; Li, H.; Xu, H. Minireview on the Commonly Applied Copper-Based Electrocatalysts for Electrochemical CO2 Reduction. Energy Fuels 2021, 35, 8585–8601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tountas, A.A.; Ozin, G.A.; Sain, M.M. Solar methanol energy storage. Nat. Catal. 2021, 4, 934–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, J.; Cao, X.; Gao, L.; Li, J.; Li, L.; Xie, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wu, M.; Liu, H. Electrochemical carbon dioxide reduction to ethylene: From mechanistic understanding to catalyst surface engineering. Nano-Micro Lett. 2023, 15, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, D.; Zhang, G.; Li, L.; Shi, X.; Zhen, S.; Zhao, Z.-J.; Gong, J. Guiding catalytic CO2 reduction to ethanol with copper grain boundaries. Chem. Sci. 2023, 14, 7966–7972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhimi, B.; Zhou, M.; Yan, Z.; Cai, X.; Jiang, Z. Cu-based materials for enhanced C2+ product selectivity in photo-/electro-catalytic CO2 reduction: Challenges and prospects. Nano-Micro Lett. 2024, 16, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, J.; Wu, J.; Hu, W.; Wang, Y.; Duan, Y.; Xia, L.; Yu, D.; Tao, X.; Gan, L.; Zhou, X. Non-Metallic Element Modification: A Promising Strategy Toward Efficient Electrocatalytic CO2 Reduction. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2423433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, A.; Fan, Y.; Xi, S.; Huang, H.; Zhang, Q.; Lyu, N.; Wu, B.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Z.; Yang, C. Nitrogen-adsorbed hydrogen species promote CO2 methanation on Cu single-atom electrocatalyst. ACS Mater. Lett. 2022, 5, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Li, Q.; Shi, L.; Niu, X.; Ling, C.; Wang, J. Hybrid Cu0 and Cux+ as atomic interfaces promote high-selectivity conversion of CO2 to C2H5OH at low potential. Small 2020, 16, 1901981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, A.; Chen, Z.; Quan, Y.; Peng, C.; Wang, Z.; Sham, T.-K.; Yang, C.; Ji, Y.; Qian, L.; Xu, X. Boosting CO2 electroreduction to CH4 via tuning neighboring single-copper sites. ACS Energy Lett. 2020, 5, 1044–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Nie, X.; Wang, H.; Chen, S.; Quan, X.; Yu, H.; Choi, W.; Zhang, G.; Kim, B.; Chen, J.G. Selective electroreduction of CO2 to acetone by single copper atoms anchored on N-doped porous carbon. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 2455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Jiang, Z.; Zhou, J.; Liu, H.; Zhou, D.; Shang, H.; Ni, X.; Peng, Z.; Yang, F.; Chen, W.; et al. Complementary Operando Spectroscopy identification of in-situ generated metastable charge-asymmetry Cu2-CuN3 clusters for CO2 reduction to ethanol. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M.; Wang, P.; Zhi, X.; Yang, K.; Jiao, Y.; Duan, J.; Zheng, Y.; Qiao, S.-Z. Electrocatalytic CO2-to-C2+ with Ampere-Level Current on Heteroatom-Engineered Copper via Tuning *CO Intermediate Coverage. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 14936–14944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Jing, H.; Wu, Z.; Yu, J.; Gao, H.; Zhang, Y.; He, G.; Lei, W.; Hao, Q. High Efficient Catalyst of N-doped Carbon Modified Copper Containing Rich Cu-N-C Active Sites for Electrocatalytic CO2 Reduction. ChemistrySelect 2022, 7, e202200557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karapinar, D.; Huan, N.T.; Ranjbar Sahraie, N.; Li, J.; Wakerley, D.; Touati, N.; Zanna, S.; Taverna, D.; Galvão Tizei, L.H.; Zitolo, A. Electroreduction of CO2 on single-site copper-nitrogen-doped carbon material: Selective formation of ethanol and reversible restructuration of the metal sites. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 15098–15103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Huang, K.; Wang, Z.; An, G.; Zhang, M.; Liu, W.; Fu, S.; Guo, H.; Zhang, B.; Lian, C. Functional Group Engineering of Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes for Anchoring Copper Nanoparticles Toward Selective CO2 Electroreduction to C2 Products. Small 2025, 2502733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Y.; Qian, L.; Xu, Q.; Wang, S.; Chen, Y.; Lu, H.; Zhou, Y.; Ye, J.; Zhao, J.; Gao, X. N-doped Cu2O with the tunable Cu0 and Cu+ sites for selective CO2 electrochemical reduction to ethylene. J. Environ. Sci. 2025, 150, 246–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, N.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; An, T.; Xiang, D.; Cai, K. Electron Delocalization and dp Orbital Coupling Regulation: Nitrogen-Mediated Efficient CO2 Electroreduction to Ethylene and Enhanced Rechargeable Zn-CO2 Battery Performance. Appl. Catal. B Environ. Energy 2025, 384, 126161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Zhang, L.; Li, Y. Imidazolium ligand-modified Cu2O catalysts for enhancing C2+ selectivity in CO2 electroreduction via local* CO enrichment. Ind. Chem. Mater. 2025, 3, 431–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuo, L.L.; Chen, P.; Zheng, K.; Zhang, X.W.; Wu, J.X.; Lin, D.Y.; Liu, S.Y.; Wang, Z.S.; Liu, J.Y.; Zhou, D.D. Flexible cuprous triazolate frameworks as highly stable and efficient electrocatalysts for CO2 reduction with tunable C2H4/CH4 selectivity. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202204967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.; Guo, C.; Shi, P.; Zhao, G. Amino Assisted Protonation for Carbon-Carbon Coupling During Electroreduction of Carbon Dioxide to Ethylene on Copper (I) Oxide. ChemCatChem 2021, 13, 4325–4333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, W.; Feng, J.; Chen, J.; Deng, L.; Guo, W.; Li, H.; Zhang, L.; Li, Y.; Zhang, B. High-efficiency C3 electrosynthesis on a lattice-strain-stabilized nitrogen-doped Cu surface. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 7070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, K.; Qin, Y.; Huang, H.; Lv, Z.; Cai, M.; Su, Y.; Huang, F.; Yan, Y. Stabilized Cu0-Cu1+ dual sites in a cyanamide framework for selective CO2 electroreduction to ethylene. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 7820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, R.; Huang, K.; Yang, X.; Xu, J.; Tong, Z. Copper electrocatalyst modified with pyridinium-based ionic liquids for the efficient synthesis of ethylene through electrocatalytic CO2 reduction reaction. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 502, 158067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Pan, Y.; Wang, Z.; Yu, Y.; Xiong, J.; Du, H.; Lai, J.; Wang, L.; Feng, S. Coordination engineering of cobalt phthalocyanine by functionalized carbon nanotube for efficient and highly stable carbon dioxide reduction at high current density. Nano Res. 2022, 15, 3056–3064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boas, C.; Focassio, B.; Marinho, E., Jr.; Larrude, D.; Salvadori, M.C.; Leão, C.R.; Dos Santos, D.J. Characterization of nitrogen doped graphene bilayers synthesized by fast, low temperature microwave plasma-enhanced chemical vapour deposition. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 13715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, L.; Jiao, M.; Ye, C. Single-Atom Catalysts for Hydrogen Evolution Reaction: The Role of Supports, Coordination Environments, and Synergistic Effects. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.-X.; Hou, S.-Z.; Zhang, X.-D.; Xu, M.; Yang, H.-F.; Cao, P.-S.; Gu, Z.-Y. Cathodized copper porphyrin metal–organic framework nanosheets for selective formate and acetate production from CO2 electroreduction. Chem. Sci. 2019, 10, 2199–2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, W.; Bagger, A.; Hao, G.-P.; Varela, A.S.; Sinev, I.; Bon, V.; Roldan Cuenya, B.; Kaskel, S.; Rossmeisl, J.; Strasser, P. Understanding activity and selectivity of metal-nitrogen-doped carbon catalysts for electrochemical reduction of CO2. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, A.; Marcandalli, G.; Mints, V.A.; Koper, M.T. Competition between CO2 reduction and hydrogen evolution on a gold electrode under well-defined mass transport conditions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 4154–4161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, C.F.; Zhou, M.; Liu, P.F.; Liu, Y.; Wu, X.; Mao, F.; Dai, S.; Xu, B.; Wang, X.L.; Jiang, Z.; et al. Highly Ethylene-Selective Electrocatalytic CO2 Reduction Enabled by Isolated Cu-S Motifs in Metal-Organic Framework Based Precatalysts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 61, e202111700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Zhang, L.H.; Du, J.; Wang, H.; Guo, J.; Zhan, J.; Li, F.; Yu, F. A Tandem Strategy for Enhancing Electrochemical CO2 Reduction Activity of Single-Atom Cu-S1N3 Catalysts via Integration with Cu Nanoclusters. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 24022–24027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, F.M.; Yuan, S.; Loh, J.Y.; Wang, J.; Zeng, X.; Ong, W.J. In-Situ Probing CO Activation in Sulfur-Enhanced Paired Electrocatalysis for CO2-to-C2+ Conversion with Alcohol Oxidation. Angew. Chem. 2025, 137, e202513840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, T.-T.; Liang, Z.-Q.; Seifitokaldani, A.; Li, Y.; De Luna, P.; Burdyny, T.; Che, F.; Meng, F.; Min, Y.; Quintero-Bermudez, R. Steering post-C-C coupling selectivity enables high efficiency electroreduction of carbon dioxide to multi-carbon alcohols. Nat. Catal. 2018, 1, 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, Q.; Feng, G.; Su, L.; Zhang, A.; Zhai, W.; Yang, Y.; Li, J.; Luo, M.; Mei, H.; Tian, H. Atomic Coordination Engineering of Sub-Nanometer Cu Clusters for Selective CO2 Electroreduction to Multi-Carbon Alcohols. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2025, e202518377. [Google Scholar]

- Kasatkin, I.; Kurr, P.; Kniep, B.; Trunschke, A.; Schlögl, R. Role of lattice strain and defects in copper particles on the activity of Cu/ZnO/Al2O3 catalysts for methanol synthesis. Angew. Chem. 2007, 119, 7465–7468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, X.; Zhou, B.; Law, W.C.; Cartwright, A.N.; Swihart, M.T. Size-controlled synthesis of Cu2-xE (E= S, Se) nanocrystals with strong tunable near-infrared localized surface plasmon resonance and high conductivity in thin films. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2013, 23, 1256–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luther, J.M.; Jain, P.K.; Ewers, T.; Alivisatos, A.P. Localized surface plasmon resonances arising from free carriers in doped quantum dots. Nat. Mater. 2011, 10, 361–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.-Q.; Zhuang, T.-T.; Seifitokaldani, A.; Li, J.; Huang, C.-W.; Tan, C.-S.; Li, Y.; De Luna, P.; Dinh, C.T.; Hu, Y. Copper-on-nitride enhances the stable electrosynthesis of multi-carbon products from CO2. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 3828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Che, F.; Liu, M.; Zou, C.; Liang, Z.; De Luna, P.; Yuan, H.; Li, J.; Wang, Z.; Xie, H. Dopant-induced electron localization drives CO2 reduction to C2 hydrocarbons. Nat. Chem. 2018, 10, 974–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, T.; Qian, Y.; Zhang, F.; Lin, B.-L. Cloride-derived copper electrode for efficient electrochemical reduction of CO2 to ethylene. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2019, 30, 314–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.-Z.; Gao, F.-Y.; Gao, M.-R. Regulating the oxidation state of nanomaterials for electrocatalytic CO2 reduction. Energy Environ. Sci. 2021, 14, 1121–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Tan, H.Y.; Zhu, Y.; Chu, H.; Chen, H.M. Linking the dynamic chemical state of catalysts with the product profile of electrocatalytic CO2 reduction. Angew. Chem. 2021, 133, 17394–17407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arán-Ais, R.M.; Scholten, F.; Kunze, S.; Rizo, R.; Roldan Cuenya, B. The role of in situ generated morphological motifs and Cu (i) species in C2+ product selectivity during CO2 pulsed electroreduction. Nat. Energy 2020, 5, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.; Yu, C.; Zhao, Z.; Guo, X.; Shen, M.; Li, N.; Muzzio, M.; Li, J.; Liu, H.; Lin, H. Cu3N nanocubes for selective electrochemical reduction of CO2 to ethylene. Nano Lett. 2019, 19, 8658–8663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.-C.; Chang, C.-C.; Chiu, S.-Y.; Pai, H.-T.; Liao, T.-Y.; Hsu, C.-S.; Chiang, W.-H.; Tsai, M.-K.; Chen, H.M. Operando time-resolved X-ray absorption spectroscopy reveals the chemical nature enabling highly selective CO2 reduction. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Lin, J.C.; Farmand, M.; Landers, A.T.; Feaster, J.T.; Avilés Acosta, J.E.; Beeman, J.W.; Ye, Y.; Yano, J.; Mehta, A. Oxidation state and surface reconstruction of Cu under CO2 reduction conditions from in situ X-ray characterization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 143, 588–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco-Velez, J.-J.; Mom, R.V.; Sandoval-Diaz, L.-E.; Falling, L.J.; Chuang, C.-H.; Gao, D.; Jones, T.E.; Zhu, Q.; Arrigo, R.; Roldan Cuenya, B. Revealing the active phase of copper during the electroreduction of CO2 in aqueous electrolyte by correlating in situ X-ray spectroscopy and in situ electron microscopy. ACS Energy Lett. 2020, 5, 2106–2111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinh, Q.T.; Banerjee, A.; Yang, Y.; Mushrif, S.H. Sub-surface boron-doped copper for methane activation and coupling: First-principles investigation of the structure, activity, and selectivity of the catalyst. J. Phys. Chem. C 2017, 121, 1099–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Yang, X.; Fang, Q.; Cheng, T.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Tang, J. Boron-modified CuO as catalyst for electroreduction of CO2 towards C2+ products. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2024, 647, 158919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, K.K.; Park, S.; Song, H.; Kim, B.; Kim, W.; Oh, J. Operando spectroscopic investigation of a boron-doped CuO catalyst and its role in selective electrochemical C-C coupling. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2020, 3, 11343–11349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, D.; Chi, X.; Wang, X.; Zhao, R.; Zhang, H.; Sun, Y. Restraining lattice oxygen of Cu2O by enhanced Cu-O hybridization for selective and stable production of ethylene with CO2 electroreduction. J. Mater. Chem. A 2022, 10, 20914–20923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Yao, Y.; Zhao, R.; Wang, X.; Fu, Z.; Wang, D.; Wang, H.; Zhao, L.; Ni, W.; Yang, Z. Stabilization of Cu+ via strong electronic interaction for selective and stable CO2 electroreduction. Angew. Chem. 2022, 134, e202205832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Zhu, C.; Mao, J.; Li, G.; Li, S.; Dong, X.; Chen, A.; Song, Y.; Feng, G.; Liu, X. Ampere-level CO2-to-ethanol conversion via boron-incorporated copper electrodes. ACS Energy Lett. 2023, 8, 4867–4874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Song, Y.; Dong, X.; Li, G.; Chen, A.; Chen, W.; Wu, G.; Li, S.; Wei, W.; Sun, Y. Ampere-level CO2 reduction to multicarbon products over a copper gas penetration electrode. Energy Environ. Sci. 2022, 15, 5391–5404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Chen, W.; Dong, X.; Zhu, C.; Chen, A.; Song, Y.; Li, G.; Wei, W.; Sun, Y. Hierarchical micro/nanostructured silver hollow fiber boosts electroreduction of carbon dioxide. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 3080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, A.; Dong, X.; Mao, J.; Chen, W.; Zhu, C.; Li, S.; Wu, G.; Wei, Y.; Liu, X.; Li, G. Gas penetrating hollow fiber Bi with contractive bond enables industry-level CO2 electroreduction. Appl. Catal. B Environ. Energy 2023, 333, 122768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Dong, X.; Mao, J.; Chen, W.; Chen, A.; Wu, G.; Zhu, C.; Li, G.; Wei, Y.; Liu, X. Highly efficient CO2 reduction at steady 2 A cm−2 by surface reconstruction of silver penetration electrode. Small 2023, 19, 2301338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Y.; Chen, C.; Zou, Z.; Hu, Z.; Fu, Z.; Li, W.; Pan, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Yu, Z. Geometric and electronic effects of Co@NPC catalyst in chemoselective hydrogenation: Tunable activity and selectivity via N, P co-doping. J. Catal. 2023, 421, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, S.; Xiao, J.; Liang, S.; Xie, W.; Zhang, T.; Li, M.; Zhong, Z.; Wang, Q.; He, H. Doping engineering of Cu-based catalysts for electrocatalytic CO2 reduction to multi-carbon products. Energy Environ. Sci. 2024, 17, 5795–5818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhuang, Z.; Chen, C.; Li, J.; Xiao, F.; Chen, C. Atomic-level regulation strategies of single-atom catalysts: Nonmetal heteroatom doping and polymetallic active site construction. Chem. Catal. 2023, 3, 100586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, F.; Chen, W. Copper-based single-atom alloys for heterogeneous catalysis. Chem. Commun. 2021, 57, 2710–2723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Li, Y.; Zeng, L.; Pan, Y. Atomic-Level Regulation of Cu-Based Electrocatalyst for Enhancing Oxygen Reduction Reaction: From Single Atoms to Polymetallic Active Sites. Small 2024, 20, 2307384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Xia, W.; Jia, S.; Jiao, J.; Yao, T.; Dong, X.; Wang, M.; Zhai, J.; Yang, J.; Xie, Y. Boosting promote C2 products formation in electrochemical CO2 reduction reaction via phosphorus-enhanced proton feeding. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 479, 147735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Qin, X.; Jiang, T.; Ma, X.Y.; Jiang, K.; Cai, W.B. Changing the product selectivity for electrocatalysis of CO2 reduction reaction on plated Cu electrodes. ChemCatChem 2019, 11, 6139–6146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.; Wang, C.; Zheng, H.; Geng, Z.; Bao, J.; Zeng, J. Enhance the activity of multi-carbon products for Cu via P doping towards CO2 reduction. Sci. China Chem. 2021, 64, 1096–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Qiu, Z.F.; Zhang, X.Y.; Chen, J.Q.; Zhao, Y.; Gong, F.; Sun, W.Y. Tailoring Coordination Microenvironment of Cu(I) in Metal-Organic Frameworks for Enhancing Electroreduction of CO2 to CH4. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2203677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, L.; You, W.; Jin, J. Mechanistic insights into the effect of halide anions on electroreduction pathways of CO2 to C1 product at Cu/H2O electrochemical interfaces. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2023, 13, 7149–7161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela, A.S.; Ju, W.; Reier, T.; Strasser, P. Tuning the Catalytic Activity and Selectivity of Cu for CO2 Electroreduction in the Presence of Halides. ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 2136–2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.F.; Dong, L.Z.; Liu, J.; Yang, R.X.; Liu, J.J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Y.R.; Li, S.L.; Lan, Y.Q. Predesign of catalytically active sites via stable coordination cluster model system for electroreduction of CO2 to ethylene. Angew. Chem. 2021, 133, 26414–26421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Liu, J.; Huang, Q.; Dong, L.Z.; Li, S.L.; Lan, Y.Q. Partial Coordination-Perturbed Bi-Copper Sites for Selective Electroreduction of CO2 to Hydrocarbons. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 19829–19835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Xie, S.; Liu, T.; Fan, Q.; Ye, J.; Sun, F.; Jiang, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Cheng, J.; Wang, Y. Electrocatalytic reduction of CO2 to ethylene and ethanol through hydrogen-assisted C-C coupling over fluorine-modified copper. Nat. Catal. 2020, 3, 478–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Chen, C.; Wu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, J.; Feng, R.; Zhang, J.; Han, B. Boosting CO2 electroreduction to C2+ products on fluorine-doped copper. Green Chem. 2022, 24, 1989–1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Tang, H.; Zhou, Y.; Lin, B.-L. Improved catalytic performance of CO2 electrochemical reduction reaction towards ethanol on chlorine-modified Cu-based electrocatalyst. Nano Res. 2024, 17, 3761–3768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Liu, T.; Wei, P.; Lin, L.; Gao, D.; Wang, G.; Bao, X. High-rate CO2 electroreduction to C2+ products over a copper-copper iodide catalyst. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 14329–14333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Ma, Y.; Chen, J.; Lawrence, R.; Luo, W.; Sacchi, M.; Jiang, W.; Yang, J. Residual chlorine induced cationic active species on a porous copper electrocatalyst for highly stable electrochemical CO2 reduction to C2+. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 11487–11493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.; Sinev, I.; Scholten, F.; Arán-Ais, R.M.; Divins, N.J.; Kvashnina, K.; Timoshenko, J.; Roldan Cuenya, B. Selective CO2 electroreduction to ethylene and multicarbon alcohols via electrolyte-driven nanostructuring. Angew. Chem. 2019, 131, 17203–17209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.; Goddard, W.A., III; Cheng, T.; Liu, Y. Cu metal embedded in oxidized matrix catalyst to promote CO2 activation and CO dimerization for electrochemical reduction of CO2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 6685–6688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Wang, Q.; Yang, H.; Feng, J.; Chen, J.; Song, S.; Meng, C.; Wang, K.; Tong, Y. Surface Facets Reconstruction in Copper-Based Materials for Enhanced Electrochemical CO2 Reduction. Small 2024, 20, 2401530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nitopi, S.; Bertheussen, E.; Scott, S.B.; Liu, X.; Engstfeld, A.K.; Horch, S.; Seger, B.; Stephens, I.E.; Chan, K.; Hahn, C. Progress and perspectives of electrochemical CO2 reduction on copper in aqueous electrolyte. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 7610–7672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.; Wagner, P.; Wagner, K.; Mozer, A.J. Electrochemical CO2 reduction catalyzed by copper molecular complexes: The influence of ligand structure. Energy Fuels 2022, 36, 4653–4676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.; Shi, G.; Liu, Y.; Luo, X.; Shen, Y.; Chang, M.; Wu, Y.; Gao, X.; Wu, J.; Li, Y. Local Coordination Environment-Driven Structural Dynamics of Single-Atom Copper and the CO2 Electroreduction Pathway. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025, 147, 26425–26436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conte, A.; Alberoni, C.; Carlotto, S.; Baron, M.; Bonacchi, S.; Aliprandi, A.; Antonello, S. Modulating C2 Selectivity in CO2 Electroreduction through Molecular Surface Engineering of Copper Nanowires. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2025, 8, 16818–16828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, C.; Shi, Y.; Li, J.; Johannessen, B.; Liang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Song, Q.; Zhang, H.; et al. Ligand-tuning copper in coordination polymers for efficient electrochemical C-C coupling. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 6316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

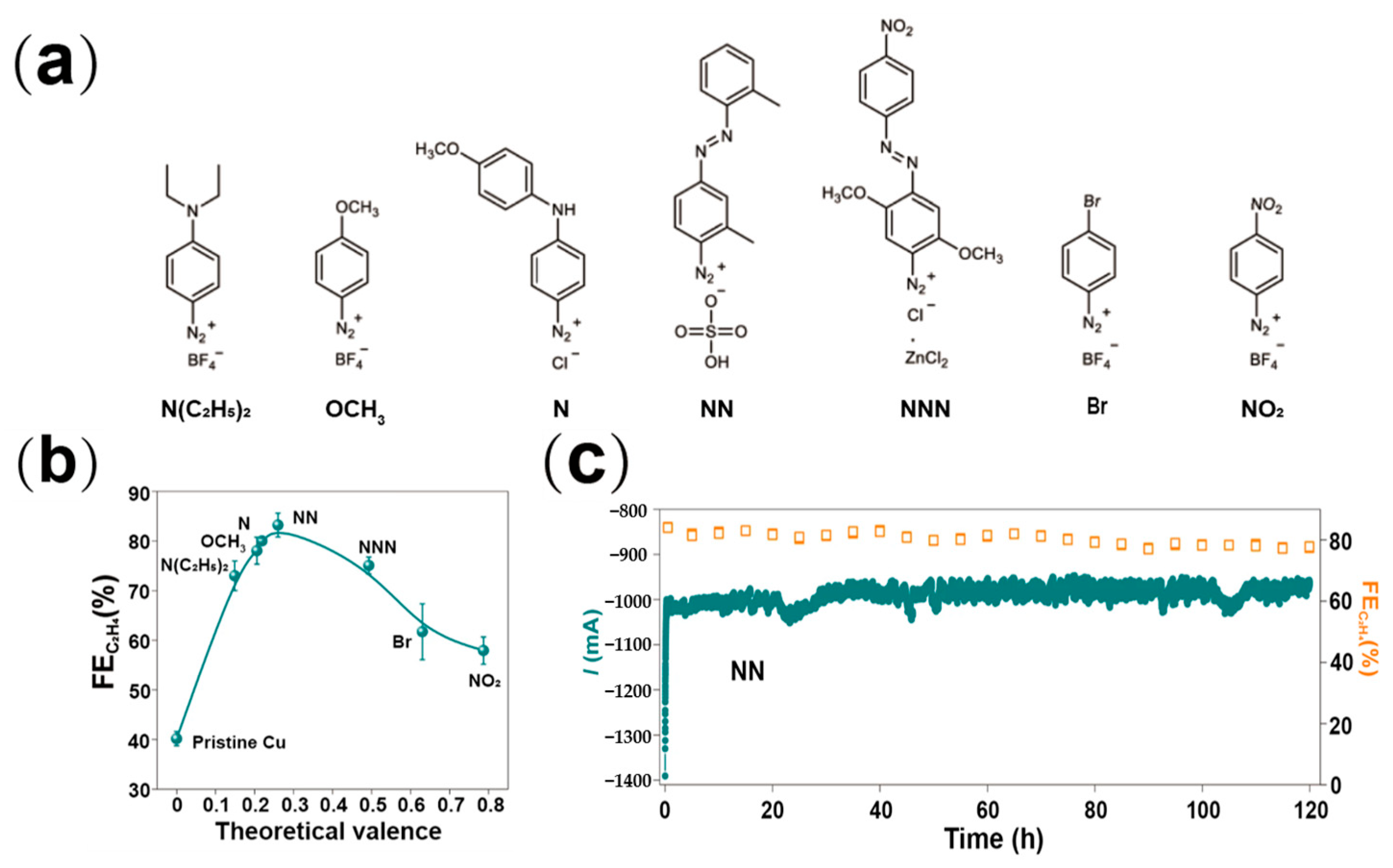

- Wu, H.; Huang, L.; Timoshenko, J.; Qi, K.; Wang, W.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, S.; Petit, E.; Flaud, V.; et al. Selective and energy-efficient electrosynthesis of ethylene from CO2 by tuning the valence of Cu catalysts through aryl diazonium functionalization. Nat. Energy 2024, 9, 422–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Chen, W.; Hao, B.; Jiang, Z.J.; Jin, G.; Jiang, Z. Garnet-Type Solid-State Electrolytes: Crystal-Phase Regulation and Interface Modification for Enhanced Lithium Metal Batteries. Small 2025, 21, 2407983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Type | Reactor Type | Electrocatalyst | Main Products | FE (%) | Potential (V vs. RHE) | Current Density (mA cm−2) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N doping into carbon support | Flow cell | Cu-Nx | C2H4 | 24.8 | −0.76 | −25 | [39] |

| H-type cell | Cu-N-C | C2H5OH | 31 | −0.93 | −22 | [43] | |

| GDE | Cu-N-C | C2H5OH | 55 | −1.2 | −100 | [44] | |

| Flow cell | R-SWCNTs | C2+ | 66.2 | −1.08 | −270 | [45] | |

| H-type cell | Cu-SA/NPC | CH3COCH3 | 36.7 | −0.5 | −1 | [40] | |

| H-type cell | Cu2-CuN3 | C2H5OH | 51 | −1.1 | −14.4 | [41] | |

| GDE | Cu–Nx | C2+ | 73.7 | −1.15 | −1100 | [42] | |

| N doping into Cu-based catalyst | GDE | OMIm-Cu2O | C2+ | 63.3 | −0.5 | −600 | [48] |

| H-type cell | MAF-2 | C2H4 | 51.2 | −1.3 | −12 | [49] | |

| H-type cell | NH2-Cu2O | C2H4 | 18 | −0.9 | −10 | [50] | |

| Flow cell | C3 | n-propanol | 54 | −0.53 | −300 | [51] | |

| Flow cell | Cuδ+NCN | C2H4 | 77.7 | −1.6 | −77.7 | [52] | |

| Flow cell | Cu@PyILs | C2H4 | 31.88 | −1.15 | −188 | [53] |

| Electrocatalyst | Reactor Type | Main Products | FE (%) | Potential (V vs. RHE) | Current Density (mA cm−2) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S-HKUST 1 | H-type cell | C2H4 | 60 | −1.32 | −400 | [60] |

| Cu2S | GDE | C2H5OH | 32 | −0.95 | −126 | [63] |

| Cu/SNC | GDE | C2+ alcohols | 59.1 | −1.4 | −200 | [64] |

| Electrocatalyst | Reactor Type | Main Products | FE (%) | Potential (V vs. RHE) | Current Density (mA cm−2) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cu(B)-2 | H-type cell | C2+ | 79 | −1 | −55 | [70] |

| B-CuO NS | H-type cell | C2+ | 54.78 | −1.2 | −16.75 | [79] |

| B-CuO | GDE | C2+ | 62.1 | −0.62 | −125 | [80] |

| B-Cu2O | H-type cell | C2H4 | 26.13 | −1.2 | −35 | [81] |

| Cu2O-BN | H-type cell | C2H4 | 7 | −1.4 | −35 | [82] |

| B-Cu HF | Flow cell | C2+ | 78.9 | −0.91 | −2400 | [83] |

| Electrocatalyst | Reactor Type | Main Products | FE (%) | Potential (V vs. RHE) | Current Density (mA cm−2) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCB/NG | Flow-cell | C2+ | 92.4 | −1.8 | −50 | [62] |

| P-Cu | H-type cell | C2+ | 80.2 | −1.2 | −40.4 | [93] |

| Cu-P | H-type cell | C2+ | 53.5 | −1.15 | −16 | [94] |

| Cu0.92P0.08 | Flow-cell | C2+ | 64 | −2 | −210 | [95] |

| Electrocatalyst | Reactor Type | Main Products | FE (%) | Potential (V vs. RHE) | Current Density (mA cm−2) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cu3-X | GDE | C2H4 | 55.01 | −1.05 | −15 | [99] |

| Cu-PzH | Flow cell | C2H4 | 60 | −1 | −346.46 | [100] |

| Cu-PzI | Flow cell | CH4 | 52 | −0.9 | −287.52 | [100] |

| F-Cu | GDE | C2+ | 80 | −0.8 | −1600 | [101] |

| Cu-Cl | GDE | C2H5OH | 26.2 | −0.74 | −343.2 | [103] |

| Cu-CuI | GDE | C2+ | 71 | −1 | −550 | [104] |

| Cu-F | GDE | C2+ | 70.4 | −1.1 | −400 | [102] |

| Cu4(OH)6FCl | H-cell | C2+ | 53.8 | −1 | −15 | [105] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, N.; Peng, H.; Liu, X.; Li, J.; Chen, J.; Wang, L. Nonmetallic Heteroatom Engineering in Copper-Based Electrocatalysts: Advances in CO2 Reduction. Catalysts 2026, 16, 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010061

Li N, Peng H, Liu X, Li J, Chen J, Wang L. Nonmetallic Heteroatom Engineering in Copper-Based Electrocatalysts: Advances in CO2 Reduction. Catalysts. 2026; 16(1):61. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010061

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Ningjing, Hongzhen Peng, Xue Liu, Jiang Li, Jing Chen, and Lihua Wang. 2026. "Nonmetallic Heteroatom Engineering in Copper-Based Electrocatalysts: Advances in CO2 Reduction" Catalysts 16, no. 1: 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010061

APA StyleLi, N., Peng, H., Liu, X., Li, J., Chen, J., & Wang, L. (2026). Nonmetallic Heteroatom Engineering in Copper-Based Electrocatalysts: Advances in CO2 Reduction. Catalysts, 16(1), 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010061