Sustainable Synthesis of Copper Oxide Nanoparticles: Data-Driven Photocatalysis, Pt-Free Hydrogen Production, and Antibacterial Assessment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Characterization of the Nanostructures

2.1. Zeta Potential

2.2. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

2.3. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD)

2.4. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

2.5. Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM)

2.6. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) and SAED Analysis: Resolving Primary and Secondary Particle Size

2.7. X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS)

2.8. Photocatalytic Activity Against NOR

2.8.1. CCD and Statistical Analysis

2.8.2. Model Testing and Statistical Analysis

2.8.3. ANOVA Analysis

2.8.4. Contour and RSM Plotting

2.8.5. Optimization

2.8.6. Recyclability Test of the Synthesized Photocatalyst

2.8.7. Interpretation of the Photocatalytic NOR Removal Results

Elaboration of the Results of RSM

Kinetics Studies

Mechanism of Photocatalytic Degradation and Effect of Radical Scavengers

- π-π stacking/cation-π interaction: Interaction between the electron-rich NOR aromatic rings and the positively charged catalyst surface or residual carbon from the plant extract.

- Hydrogen bonding: between the carbonyl (-C=O), ketone, and carboxylic acid groups of NOR and the surface hydroxyl groups (-OH) of CuO.

- Surface complexation: coordination of the ketone and carboxylate oxygen atoms of NOR with the Lewis acid sites (copper cations) on the catalyst surface.

2.8.8. Importance and Relationship of the Synthesized Nanoparticles on the Synergistic NOR Removal

Morphology and Photocatalytic Activity

Synergistic Effects of CuO Nanostructures

Specific Structural Roles

2.8.9. Examination of the Turnover Number (TON) and Turnover Frequency (TOF)

2.8.10. Mechanism of the ROS Generation Responsible for the Photocatalytic NOR Degradation and Antimicrobial Activity

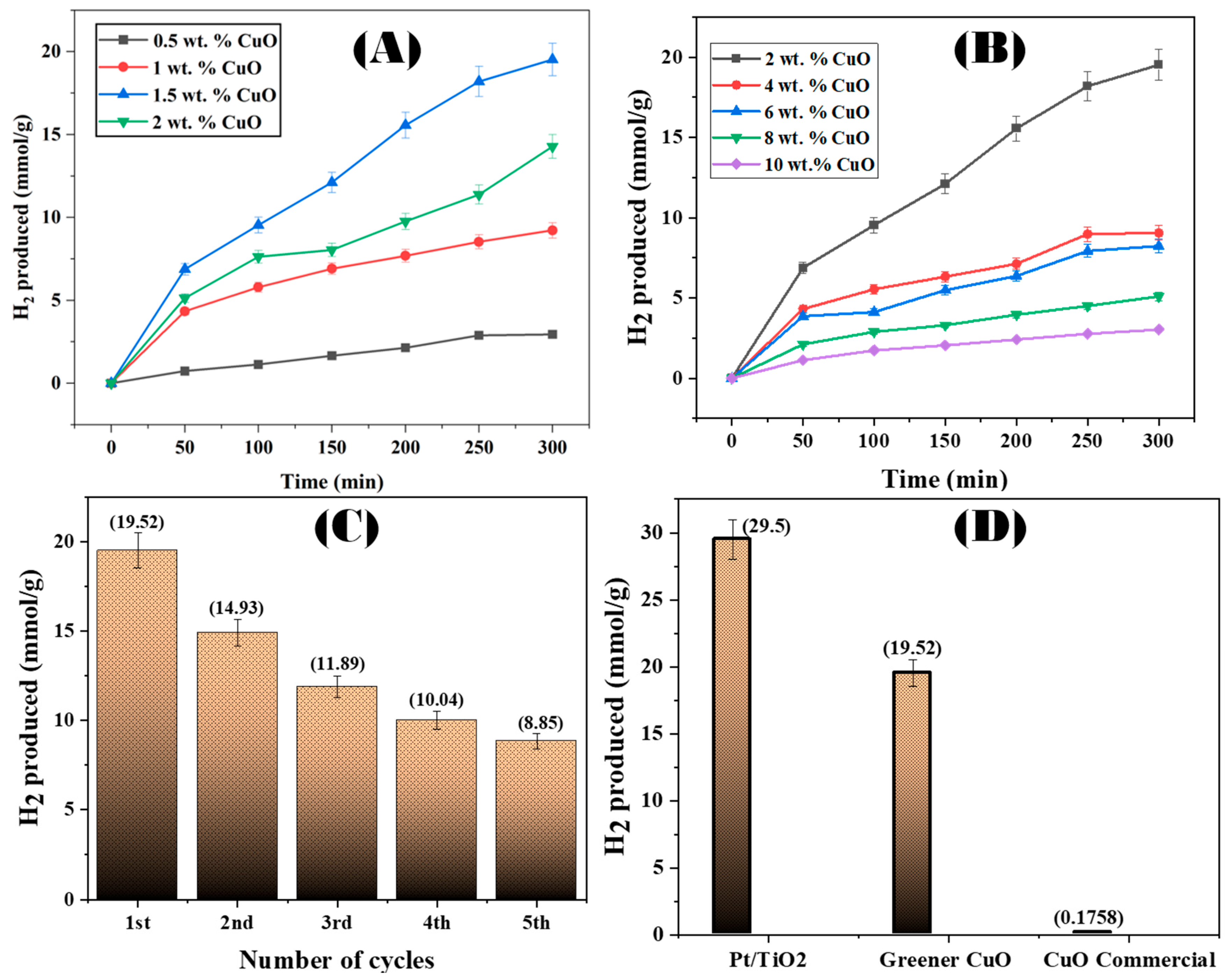

2.9. Photocatalytic H2 Production

2.10. Antibacterial Activity

2.11. In Vitro Anticancer Activity

2.12. In Vitro Antifungal Activity

2.13. Comparison

2.14. Calculation of the Data for Standard Deviation (SD)

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Chemicals

3.2. Preparation of Aqueous Plant Extract

3.3. Green Synthesis of Copper Oxide Nanostructures

3.4. Photocatalytic Degradation of NOR by Using Copper Oxide Nanostructures

3.4.1. Central Composite Design (CCD)-Based Optimization Methodology for Photocatalysis

3.4.2. Experimental Section

3.4.3. Statistical Analysis

3.4.4. CCD-RSM-Based Standard Table Development

3.5. Photocatalytic H2 Production Test

3.6. Antibacterial Assay

3.7. Anticancer Activity Protocol

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Guo, X.; Li, R.; Zhang, Y.; Pan, S. Systematic investigation of peracetic acid activation by UV/ferric (III) hydrate oxide for efficient degradation of norfloxacin: Mechanisms and applications. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 481, 148468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.-H.; He, C.-S.; He, Y.-L.; Yang, S.-R.; Yu, S.-Y.; Xiong, Z.; Du, Y.; Liu, Y.; Pan, Z.-C.; Yao, G.; et al. Peracetic acid activation via the synergic effect of Co and Fe in CoFe-LDH for efficient degradation of pharmaceuticals in hospital wastewater. Water Res. 2023, 232, 119666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez, E.; Cestaro, R.; Philippe, L.; Serra, A. Electrodeposition of nanostructured Bi2MoO6@ Bi2MoO6–x homojunction films for the enhanced visible-light-driven photocatalytic degradation of antibiotics. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2022, 317, 121703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.H.; Aziz, H.A.; Palaniandy, P.; Naushad, M.; Zouli, N. Ciprofloxacin adsorption onto CNT loaded Pumice: Adsorption Modelling, kinetics, equilibriums and reusability studies. J. Mol. Liq. 2024, 399, 124388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangla, D.; Sharma, A.; Ikram, S. Critical review on adsorptive removal of antibiotics: Present situation, challenges and future perspective. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 425, 127946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gahrouei, A.E.; Vakili, S.; Zandifar, A.; Pourebrahimi, S. From wastewater to clean water: Recent advances on the removal of metronidazole, ciprofloxacin, and sulfamethoxazole antibiotics from water through adsorption and advanced oxidation processes (AOPs). Environ. Res. 2024, 252, 119029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhao, L.; Feng, M.; Huang, C.-H.; Sun, P. Abiotic transformation and ecotoxicity change of sulfonamide antibiotics in environmental and water treatment processes: A critical review. Water Res. 2021, 202, 117463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganeshbabu, M.; Priya, J.S.; Manoj, G.M.; Puneeth, N.P.N.; Shobana, C.; Shankar, H.; Selvan, R.K. Photocatalytic degradation of fluoroquinolone antibiotics using chitosan biopolymer functionalized copper oxide nanoparticles prepared by facile sonochemical method. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 253, 127027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Hu, L.; Zhao, M.; Dai, L.; Hrynsphan, D.; Tatsiana, S.; Chen, J. Bamboo charcoal fused with polyurethane foam for efficiently removing organic solvents from wastewater: Experimental and simulation. Biochar 2022, 4, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Zhao, Z.; Yin, X.-A.; Zhu, Y. Impacts of biochars on bacterial community shifts and biodegradation of antibiotics in an agricultural soil during short-term incubation. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 771, 144751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.A.; López-Maldonado, E.A.; Majumder, A.; Singh, S.; Varshney, R.; López, J.; Méndez, P.; Ramamurthy, P.C.; Khan, M.A.; Khan, A.H.; et al. A state-of-art-review on emerging contaminants: Environmental chemistry, health effect, and modern treatment methods. Chemosphere 2023, 344, 140264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schafhauser, B.H.; Kristofco, L.A.; de Oliveira, C.M.R.; Brooks, B.W. Global review and analysis of erythromycin in the environment: Occurrence, bioaccumulation and antibiotic resistance hazards. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 238, 440–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, S.; Zhou, C.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, K.; Ye, W.; Zhao, X.; Cai, L.; Hui, B. Natural wood-derived charcoal embedded with bimetallic iron/cobalt sites to promote ciprofloxacin degradation. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 414, 137569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Fan, B.; Zhao, J.; Yang, B.; Zheng, X. Benzothiazole derivatives-based supramolecular assemblies as efficient corrosion inhibitors for copper in artificial seawater: Formation, interfacial release and protective mechanisms. Corros. Sci. 2023, 212, 110957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, Z.; Alam, P.; Islam, R.; Khan, A.H.; Samaraweera, H.; Hussain, A.; Zargar, T.I. Recent developments in moving bed biofilm reactor (MBBR) for the treatment of phenolic wastewater-A review. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2024, 166, 105517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.; Arora, U.; Zaman, K. Antibiotics, antibiotic-resistant bacteria, and the environment. In Degradation of Antibiotics and Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria from Various Sources; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 117–142. [Google Scholar]

- Alam, A.; Rahman, W.U.; Rahman, Z.U.; Khan, S.A.; Shah, Z.; Shaheen, K.; Suo, H.; Qureshi, M.N.; Khan, S.B.; Bakhsh, E.M.; et al. Photocatalytic degradation of the antibiotic ciprofloxacin in the aqueous solution using Mn/Co oxide photocatalyst. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2022, 33, 4255–4267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosa-Hernández, J.E.; Rodas-Zuluaga, L.I.; López-Pacheco, I.Y.; Melchor-Martínez, E.M.; Aghalari, Z.; Limón, D.S.; Iqbal, H.M.; Parra-Saldívar, R. Sources of antibiotics pollutants in the aquatic environment under SARS-CoV-2 pandemic situation. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2021, 4, 100127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben, Y.; Fu, C.; Hu, M.; Liu, L.; Wong, M.H.; Zheng, C. Human health risk assessment of antibiotic resistance associated with antibiotic residues in the environment: A review. Environ. Res. 2019, 169, 483–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattopadhyay, I.; Usman, T.M.; Varjani, S. Exploring the role of microbial biofilm for industrial effluents treatment. Bioengineered 2022, 13, 6420–6440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Lu, G.; Yan, Z.; Liu, J.; Wang, P.; Wang, Y. Bioaccumulation and trophic transfer of pharmaceuticals in food webs from a large freshwater lake. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 222, 356–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, M.; Ahmed, S.; Abdullah, A.Z.; Hakami, J.; Chaudhary, A.A.; Rudayni, H.A.; Khan, S.; Khan, A.; Basher, N.S. Nanostructured material-based optical and electrochemical detection of amoxicillin antibiotic. Luminescence 2023, 38, 1064–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanna, N.; Sun, P.; Sun, Q.; Li, X.; Yang, X.; Ji, X.; Zou, H.; Ottoson, J.; Nilsson, L.E.; Berglund, B.; et al. Presence of antibiotic residues in various environmental compartments of Shandong province in eastern China: Its potential for resistance development and ecological and human risk. Environ. Int. 2018, 114, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, A.H.; Aziz, H.A.; Palaniandy, P.; Naushad, M.; Cevik, E.; Zahmatkesh, S. Pharmaceutical residues in the ecosystem: Antibiotic resistance, health impacts, and removal techniques. Chemosphere 2023, 339, 139647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sathya, K.; Nagarajan, K.; Carlin Geor Malar, G.; Rajalakshmi, S.; Raja Lakshmi, P. A comprehensive review on comparison among effluent treatment methods and modern methods of treatment of industrial wastewater effluent from different sources. Appl. Water Sci. 2022, 12, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora-Gamboa, M.P.; Rincón-Gamboa, S.M.; Ardila-Leal, L.D.; Poutou-Piñales, R.A.; Pedroza-Rodríguez, A.M.; Quevedo-Hidalgo, B.E. Impact of antibiotics as waste, physical, chemical, and enzymatical degradation: Use of laccases. Molecules 2022, 27, 4436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, F.; Zhu, D.; Sun, J. Environmental fate of tetracycline antibiotics: Degradation pathway mechanisms, challenges, and perspectives. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2021, 33, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abutaleb, A.; Ahmed, S.; Imran, M. Synergistic photocatalysis: Harnessing WSe2-ZnO nanocomposites for efficient malachite green dye degradation. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 2023, 138, 1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, T.; Khandelwal, V.; Gupta, S.; Singh, A.; Kaur, R.; Pathak, S.; Sharma, M.K.; Sharma, A.; Sharma, B.P.; Singh, J.; et al. Pharmaceutical wastewater management: Physicochemical, chemical, and biological approaches. In Development in Wastewater Treatment Research and Processes; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Ezaier, Y.; Hader, A.; Latif, A.; Khan, M.E.; Ali, W.; Ali, S.K.; Khan, A.U.; Bashiri, A.H.; Zakri, W.; Yusuf, M.; et al. Solving the fouling mechanisms in composite membranes for water purification: An advance approach. Environ. Res. 2024, 250, 118487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonopoulou, M.; Kosma, C.; Albanis, T.; Konstantinou, I. An overview of homogeneous and heterogeneous photocatalysis applications for the removal of pharmaceutical compounds from real or synthetic hospital wastewaters under lab or pilot scale. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 765, 144163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Wen, J.; Shen, Y.; He, F.; Mi, L.; Gan, Z.; Ma, J.; Liu, S.; Ma, H.; Zhang, Y. Dissolution and homogeneous photocatalysis of polymeric carbon nitride. Chem. Sci. 2018, 9, 7912–7915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelosato, R.; Bolognino, I.; Fontana, F.; Sora, I.N. Applications of heterogeneous photocatalysis to the degradation of oxytetracycline in water: A review. Molecules 2022, 27, 2743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silerio-Vázquez, F.; Alarcón-Herrera, M.T.; Proal-Nájera, J.B. Solar heterogeneous photocatalytic degradation of phenol on TiO2/quartz and TiO2/calcite: A statistical and kinetic approach on comparative efficiencies towards a TiO2/glass system. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 42319–42330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izzudin, N.M.; Jalil, A.A.; Aziz, F.F.A.; Azami, M.S.; Ali, M.W.; Hassan, N.S.; Rahman, A.F.A.; Fauzi, A.A.; Vo, D.V.N. Simultaneous remediation of hexavalent chromium and organic pollutants in wastewater using period 4 transition metal oxide-based photocatalysts: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2021, 19, 4489–4517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, U.; Raza, M.; Khan, S.A.; Alam, S.; Khan, M.E.; Ali, W.; Al Zoubi, W.; Ali, S.K.; Bashiri, A.H.; Zakri, W. Fabrication and characterization of binary composite MgO/CuO nanostructures for the efficient photocatalytic ability to eliminate organic contaminants: A detailed spectroscopic analysis. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2024, 315, 124264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.E.; Khan, M.M.; Cho, M.H. Ce3+-ion, surface oxygen vacancy, and visible light-induced photocatalytic dye degradation and photocapacitive performance of CeO2-graphene nanostructures. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 5928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.E.; Mohammad, A.; Ali, W.; Khan, A.U.; Hazmi, W.; Zakri, W.; Yoon, T. Excellent visible-light photocatalytic activity towards the degradation of tetracycline antibiotic and electrochemical sensing of hydrazine by SnO2–CdS nanostructures. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 349, 131249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.E.; Khan, M.M.; Min, B.-K.; Cho, M.H. Microbial fuel cell assisted band gap narrowed TiO2 for visible light-induced photocatalytic activities and power generation. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karthikeyan, C.; Arunachalam, P.; Ramachandran, K.; Al-Mayouf, A.M.; Karuppuchamy, S. Recent advances in semiconductor metal oxides with enhanced methods for solar photocatalytic applications. J. Alloys Compd. 2020, 828, 154281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, S. DLS and zeta potential–what they are and what they are not? J. Control. Release 2016, 235, 337–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, U.; Qureshi, A.K.; Farhan, M.; Romman, U.; Khan, M.E.; Ali, W.; Bashiri, A.H.; Zakri, W. Environmentally sustainable fabrication of palladium nanoparticles from the ethanolic crude extract of Oxystelma esculentum towards effective degradation of organic dye. Mater. Today Sustain. 2023, 23, 100463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, U.; Akter, S.; Qureshi, A.K.; Alhuthali, H.M.; Almehmadi, M.; Allahyani, M.; Alsaiari, A.A.; Aljuaid, A.; Farzana, M.; Alhazmi, A.Y.M.; et al. Arbutin stabilized silver nanoparticles: Synthesis, characterization, and its catalytic activity against different organic dyes. Catalysts 2022, 12, 1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, M.; Raza, M.; Noor, H.; Faraz, S.M.; Raza, A.; Farooq, U.; Khan, M.E.; Ali, S.K.; Bakather, O.Y.; Ali, W.; et al. Insight into mechanism of excellent visible-light photocatalytic activity of CuO/MgO/ZnO nanocomposite for advanced solution of environmental remediation. Chemosphere 2024, 359, 142224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, M.; Mishra, S.; Verma, R.; Shikha, D. Synthesis of ZnO and CuO nanoparticles via Sol gel method and its characterization by using various technique. Discov. Mater. 2022, 2, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekar, M.; Subash, M.; Logambal, S.; Udhayakumar, G.; Uthrakumar, R.; Inmozhi, C.; Al-Onazi, W.A.; Al-Mohaimeed, A.M.; Chen, T.-W.; Kanimozhi, K. Synthesis and characterization studies of pure and Ni doped CuO nanoparticles by hydrothermal method. J. King Saud Univ.-Sci. 2022, 34, 101831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vindhya, P.; Kavitha, V. Effect of cobalt doping on antimicrobial, antioxidant and photocatalytic activities of CuO nanoparticles. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2023, 289, 116258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesan, K.; Jothi, V.K.; Natarajan, A.; Rajaram, A.; Ravichandran, S.; Ramalingam, S. Green synthesis of Copper oxide nanoparticles decorated with graphene oxide for anticancer activity and catalytic applications. Arab. J. Chem. 2020, 13, 6802–6814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, W.; Li, L.; Meng, Q.; Zhang, X. Molybdenum-doped CuO nanosheets on Ni foams with extraordinary specific capacitance for advanced hybrid supercapacitors. J. Mater. Sci. 2020, 55, 2492–2502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, M.; Farooq, U.; Khan, M.E.; Naseem, K.; Alam, S.; Khan, M.Y.; Ali, W.; Ali, S.K.; Bakather, O.Y.; Al Zoubi, W.; et al. Development of simplistic and stable Co-doped ZnS nanocomposite towards excellent removal of bisphenol A from wastewater and hydrogen production: Evaluation of reaction parameters by response surface methodology. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2024, 163, 105654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, S.; Dutta, R.K. Enhanced ROS generation by ZnO-ammonia modified graphene oxide nanocomposites for photocatalytic degradation of trypan blue dye and 4-nitrophenol. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 4776–4787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazrafshan, E.; Mohammadi, L.; NadeemZafar, M.; Dargahi, A.; Pirdadeh, F. Synthesis of magnesium oxide nanoparticles and its application for photocatalytic removal of furfural from aqueous media: Optimization using response surface methodology. Arab. J. Chem. 2023, 16, 104998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waqar, A.; Bheel, N.; Shafiq, N.; Othman, I.; Khan, M.B.; Mansoor, M.S.; Benjeddou, O.; Yaseen, G. Effect of volcanic pumice powder ash on the properties of cement concrete using response surface methodology. J. Build. Pathol. Rehabil. 2023, 8, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moztahida, M.; Lee, D.S. Photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue with P25/graphene/polyacrylamide hydrogels: Optimization using response surface methodology. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 400, 123314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, M.; Farooq, U.; Khan, S.A.; Ullah, Z.; Khan, M.E.; Ali, S.K.; Bakather, O.Y.; Alam, S.; Khan, M.Y.; Ali, W.; et al. Preparation and Spectrochemical characterization of Ni-doped ZnS nanocomposite for effective removal of emerging contaminants and hydrogen Production: Reaction Kinetics, mechanistic insights. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2024, 318, 124513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alhasan, H.S.; Omran, A.R.; Al Mahmud, A.; Mady, A.H.; Thalji, M.R. Toxic Congo red dye photodegradation employing green synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles using gum arabic. Water 2024, 16, 2202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Gao, S.; Lv, J.; Hou, S.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, J. Assessing the photocatalytic transformation of norfloxacin by BiOBr/iron oxides hybrid photocatalyst: Kinetics, intermediates, and influencing factors. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2017, 205, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, U.; Qureshi, A.K.; Noor, H.; Farhan, M.; Khan, M.E.; Hamed, O.A.; Bashiri, A.H.; Zakri, W. Plant extract-based fabrication of silver nanoparticles and their effective role in antibacterial, anticancer, and water treatment applications. Plants 2023, 12, 2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.-Y.; Zhao, L.; Guo, L.-H.; Zhang, H.; Chen, F.-J.; Yu, W.-C. Roles of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the photocatalytic degradation of pentachlorophenol and its main toxic intermediates by TiO2/UV. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 369, 719–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotiou, T.; Triantis, T.M.; Kaloudis, T.; O’Shea, K.E.; Dionysiou, D.D.; Hiskia, A. Assessment of the roles of reactive oxygen species in the UV and visible light photocatalytic degradation of cyanotoxins and water taste and odor compounds using C–TiO2. Water Res. 2016, 90, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.-T.; Jovic, V.; Sun-Waterhouse, D.; Idriss, H.; Waterhouse, G.I. The role of CuO in promoting photocatalytic hydrogen production over TiO2. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2013, 38, 15036–15048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, U.; Rafique, H.; Akram, S.; Chen, S.S.; Naseem, K.; Najeeb, J.; Tayyab, M. Facile green synthesis of Phyllanthus emblica extract based Ag-NPs for antimicrobial and response surface methodology based catalytic reduction applications. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 434, 140003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awais, S.; Munir, H.; Najeeb, J.; Anjum, F.; Naseem, K.; Kausar, N.; Shahid, M.; Irfan, M.; Najeeb, N. Green synthesis of iron oxide nanoparticles using Bombax malabaricum for antioxidant, antimicrobial and photocatalytic applications. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 406, 136916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, S.; Khan, S.U.; Najeeb, J.; Naeem, S.; Rafique, H.; Munir, H.; Al-Masry, W.A.; Nazar, M.F. Synthesis of cadmium oxide nanostructures by using Dalbergia sissoo for response surface methodology based photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 365, 132822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danish, M.; Ayub, H.; Sandhu, Z.A.; Shoaib, A.; Akram, S.; Najeeb, J.; Naeem, S. Synthesis of cerium oxide/cadmium sulfide nanocomposites using inverse microemulsion methodology for photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue. Appl. Nanosci. 2021, 11, 2503–2515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.I.; Akhtar, M.N.; Ashraf, N.; Najeeb, J.; Munir, H.; Awan, T.I.; Tahir, M.B.; Kabli, M.R. Green synthesis of magnesium oxide nanoparticles using Dalbergia sissoo extract for photocatalytic activity and antibacterial efficacy. Appl. Nanosci. 2020, 10, 2351–2364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chelladurai, S.J.S.; Murugan, K.; Ray, A.P.; Upadhyaya, M.; Narasimharaj, V.; Gnanasekaran, S. Optimization of process parameters using response surface methodology: A review. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 37, 1301–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qadir, R.; Anwar, F.; Naseem, K.; Tahir, M.H.; Alhumade, H. Enzyme-assisted extraction of Phenolics from Capparis spinosa fruit: Modeling and optimization of the process by RSM and ANN. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 33031–33038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayat, M.; Manzoor, S.; Raza, N.; Abbas, A.; Khan, M.I.; Elboughdiri, N.; Naseem, K.; Shanableh, A.; Elbadry, A.M.M.; Al Arni, S.; et al. Molecularly imprinted polymeric sorbent for targeted dispersive solid-phase microextraction of fipronil from milk samples. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 41437–41448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhou, L.; Shehzad, H.; Farooqi, Z.H.; Sharif, A.; Ahmed, E.; Habiba, U.; Qaisar, F.; Fatima, N.-E.; Begum, R.; et al. Innovative free radical induced synthesis of WO3-doped diethyl malonate grafted chitosan encapsulated with phosphorylated alginate matrix for UO22+ adsorption: Parameters optimisation through response surface methodology. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 353, 128455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Arellano, S.; Torres-Martinez, L.; Luévano-Hipólito, E.; Aleman-Ramirez, J.; Sebastian, P. Biologically mediated synthesis of CuO nanoparticles using corn COB (Zea mays) ash for photocatalytic hydrogen production. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2023, 301, 127640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khashan, K.S.; Sulaiman, G.M.; Abdulameer, F.A. Synthesis and antibacterial activity of CuO nanoparticles suspension induced by laser ablation in liquid. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2016, 41, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, S.M.A.; Nayef, U.M.; Rasheed, M. Synthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles via laser ablation in liquid for en-hancing spectral responsivity. Plasmonics 2025, 20, 2869–2879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banu, T.; Jamal, M.; Gulshan, F. Opto-structural properties and photocatalytic activities of CuO NPs synthesized by modified sol-gel and Co-precipitation methods: A comparative study. Results Mater. 2023, 19, 100419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jan, T.; Azmat, S.; Mansoor, Q.; Waqas, H.M.; Adil, M.; Ilyas, S.Z.; Ismail, M. Superior antibacterial activity of ZnO-CuO nanocomposite synthesized by a chemical Co-precipitation approach. Microb. Pathog. 2019, 134, 103579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayaprakash, J.; Srinivasan, N.; Chandrasekaran, P.; Girija, E.K. Synthesis and characterization of cluster of grapes like pure and Zinc-doped CuO nanoparticles by sol–gel method. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2015, 136, 1803–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, F.; Zhang, H.; Lu, W.; Li, X. Synthesis of ZnO/CuO composite coaxial nanoarrays by combined hydrothermal–solvothermal method and potential for solar cells. J. Compos. Mater. 2015, 49, 2009–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajesh, S.; Geetha, A.; Guganathan, L.; Suthakaran, S.; Anbuvannan, M.; Pragadeswaran, S.; Palaniappan, S.K. Enhanced photocatalytic performance of CuO nanoparticles synthesized via surfactant assisted hydrothermal method. Appl. Phys. A 2024, 130, 661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigore, M.E.; Biscu, E.R.; Holban, A.M.; Gestal, M.C.; Grumezescu, A.M. Methods of synthesis, properties and biomedical applications of CuO nanoparticles. Pharmaceuticals 2016, 9, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naz, S.; Gul, A.; Zia, M.; Javed, R. Synthesis, biomedical applications, and toxicity of CuO nanoparticles. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2023, 107, 1039–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannan, K.; Chanda, D.; Gautam, J.; Behera, A.; Meshesha, M.M.; Jang, S.G.; Yang, B. Hydrothermally synthesized mixed metal oxide nanocomposites for electrochemical water splitting and photocatalytic hydrogen production. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 36412–36426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Dai, F.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, R.; Wang, L.; Feng, S. Synthesis of CdSe/SrTiO3 nanocomposites with enhanced pho-tocatalytic hydrogen production activity. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 467, 1033–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miwa, T.; Kaneco, S.; Katsumata, H.; Suzuki, T.; Ohta, K.; Verma, S.C.; Sugihara, K. Photocatalytic hydrogen pro-duction from aqueous methanol solution with CuO/Al2O3/TiO2 nanocomposite. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2010, 35, 6554–6560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafeez, H.Y.; Lakhera, S.K.; Bellamkonda, S.; Rao, G.R.; Shankar, M.V.; Bahnemann, D.W.; Neppolian, B. Con-struction of ternary hybrid layered reduced graphene oxide supported g-C3N4-TiO2 nanocomposite and its photocatalytic hydrogen production activity. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2018, 43, 3892–3904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diab, K.R.; El-Maghrabi, H.H.; Nada, A.A.; Youssef, A.M.; Hamdy, A.; Roualdes, S.; Abd El-Wahab, S. Facile fab-rication of NiTiO3/graphene nanocomposites for photocatalytic hydrogen generation. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2018, 365, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Runs | Variables | D% | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actual Variables | Coded Variables | ||||||||

| Reaction Time (min) | CuO-NPs Dose (mg) | NOR Dose (ppm) | pH (Units) | A (min) | B (mg) | C (ppm) | D (units) | ||

| 1 | 60 | 20 | 45 | 10 | +1 | −1 | +1 | +1 | 74.23 |

| 2 | 60 | 20 | 45 | 5 | +1 | −1 | +1 | −1 | 79.99 |

| 3 | 30 | 20 | 20 | 10 | −1 | −1 | −1 | +1 | 91.63 |

| 4 | 45 | 35 | 32.5 | 7.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 87.6 |

| 5 | 30 | 50 | 20 | 5 | −1 | +1 | −1 | −1 | 86.19 |

| 6 | 45 | 35 | 32.5 | 7.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 91.07 |

| 7 | 45 | 35 | 32.5 | 7.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 90.34 |

| 8 | 60 | 50 | 45 | 10 | +1 | +1 | +1 | +1 | 76.87 |

| 9 | 60 | 20 | 20 | 10 | +1 | −1 | −1 | +1 | 86.08 |

| 10 | 60 | 50 | 20 | 10 | +1 | +1 | −1 | +1 | 87.18 |

| 11 | 45 | 65 | 32.5 | 7.5 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 82.2 |

| 12 | 60 | 50 | 45 | 5 | +1 | +1 | +1 | −1 | 94.26 |

| 13 | 45 | 35 | 32.5 | 2.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | - | 93.86 |

| 14 | 45 | 5 | 32.5 | 7.5 | 0 | - | 0 | 0 | 69.98 |

| 15 | 45 | 35 | 57.5 | 7.5 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 71.1 |

| 16 | 30 | 20 | 45 | 10 | −1 | −1 | 1 | 1 | 73.51 |

| 17 | 45 | 35 | 7.5 | 7.5 | 0 | 0 | - | 0 | 79.59 |

| 18 | 60 | 50 | 20 | 5 | +1 | +1 | −1 | −1 | 85.75 |

| 19 | 45 | 35 | 32.5 | 7.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 92.67 |

| 20 | 45 | 35 | 32.5 | 12.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | 88.73 |

| 21 | 30 | 50 | 20 | 10 | −1 | +1 | −1 | +1 | 82.38 |

| 22 | 45 | 35 | 32.5 | 7.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 90.05 |

| 23 | 45 | 35 | 32.5 | 7.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 92.49 |

| 24 | 30 | 20 | 20 | 5 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | 78.99 |

| 25 | 75 | 35 | 32.5 | 7.5 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | 84.15 |

| 26 | 30 | 50 | 45 | 5 | −1 | +1 | +1 | −1 | 91.12 |

| 27 | 30 | 50 | 45 | 10 | −1 | +1 | +1 | +1 | 77.56 |

| 28 | 60 | 20 | 20 | 5 | +1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | 79.32 |

| 29 | 30 | 20 | 45 | 5 | −1 | −1 | +1 | −1 | 84.12 |

| 30 | 15 | 35 | 32.5 | 7.5 | − | 0 | 0 | 0 | 84.62 |

| Model | p-Value | R2 | Predicted R2 | Adjusted-R2 | Lack-of-Fit p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quadratic | 0.0001 | 0.9541 | 0.7897 | 0.9113 | 0.3948 |

| Model Fit Summary | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source | Standard deviation | Sequential p-value | Lack of Fit p-value | R2 | Adjusted R2 | Predicted R2 | PRESS | Remarks |

| Linear | 6.65 | 0.2028 | 0.0032 | 0.2049 | 0.0776 | −0.14788 | 1596.38 | Not suggested |

| 2-factor interaction (2FI) | 6.15 | 0.1729 | 0.0041 | 0.4838 | 0.2120 | 0.13292 | 1205.86 | Not suggested |

| Quadratic | 2.06 | <0.0001 | 0.3948 | 0.9541 | 0.9112 | 0.78973 | 292.42 | Suggested |

| Cubic | 2.69 | 0.9742 | 0.0684 | 0.9634 | 0.84857 | −2.4812 | 4841.35 | Aliased |

| Sequential Model Sum of Squares [Type-1] | ||||||||

| Source | Sum of Squares | Degrees of freedom | Mean Square | F-value | p-value | Remarks | ||

| Mean vs. Total | 2.130 × 105 | 1 | 2.130 × 105 | -- | ||||

| Linear vs. mean | 284.92 | 4 | 71.23 | 1.61 | 0.2028 | Not suggested | ||

| 2FI vs. Linear | 387.85 | 6 | 64.64 | 1.71 | 0.1729 | Not suggested | ||

| Quadratic vs. 2FI | 654.14 | 4 | 163.53 | 38.44 | <0.0001 | Suggested | ||

| Cubic vs. Quadratic | 12.98 | 8 | 1.62 | 0.2234 | 0.9742 | Aliased | ||

| Residual | 50.83 | 7 | 7.26 | -- | ||||

| Total | 2.144 × 105 | 30 | 7145.15 | -- | ||||

| Lack of fit tests | ||||||||

| Source | Sum of Squares | Degrees of freedom | Mean Square | F-value | p-value | Remarks | ||

| Linear | 1088.41 | 20 | 54.42 | 15.65 | 0.0032 | -- | ||

| 2FI | 700.56 | 14 | 50.04 | 14.39 | 0.0041 | -- | ||

| Quadratic | 46.42 | 10 | 4.64 | 1.34 | 0.3948 | Suggested | ||

| Cubic | 33.45 | 2 | 16.72 | 4.81 | 0.0684 | Aliased | ||

| Pure Error | 17.38 | 5 | 3.48 | -- | ||||

| Source | Sum of Squares | Degree of Freedom | Mean Square | F-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 1326.90 | 14 | 94.78 | 22.28 | <0.0001 |

| A | 0.3174 | 1 | 0.3174 | 0.0746 | 0.7885 |

| B | 139.59 | 1 | 139.59 | 32.82 | <0.0001 |

| C | 76.47 | 1 | 76.47 | 17.98 | 0.0007 |

| D | 68.55 | 1 | 68.55 | 16.11 | 0.0011 |

| AB | 14.90 | 1 | 14.90 | 3.50 | 0.0809 |

| AC | 0.0006 | 1 | 0.0006 | 0.0001 | 0.9905 |

| AD | 0.0090 | 1 | 0.0090 | 0.0021 | 0.9639 |

| BC | 31.58 | 1 | 31.58 | 7.43 | 0.0157 |

| BD | 82.63 | 1 | 82.63 | 19.42 | 0.0005 |

| CD | 258.73 | 1 | 258.73 | 60.82 | <0.0001 |

| A2 | 51.01 | 1 | 51.01 | 11.99 | 0.0035 |

| B2 | 324.11 | 1 | 324.11 | 76.19 | <0.0001 |

| C2 | 360.18 | 1 | 360.18 | 84.67 | <0.0001 |

| D2 | 3.63 | 1 | 3.63 | 0.8532 | 0.3703 |

| Residual | 63.81 | 15 | 4.25 | ||

| Lack of Fit | 46.42 | 10 | 4.64 | 1.34 | 0.3948 |

| Pure Error | 17.38 | 5 | 3.48 | ||

| Cor Total | 1390.71 | 29 |

| Bacterial Strain | DMSO (Control) | Ciprofloxacin (Control) | CuO NPs |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1 (Klebsiella) | 3 nm | 15 nm | 8 nm |

| -ve (E. coli) | 7 nm | 10 nm | - |

| 38 (Bacillus) | 5 nm | 20 nm | 9 nm |

| Fungus | Sample Growth (nm) | Control Growth (nm) | % Inhibition | Standard Drug |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trichophyton rubrum (ATCC MYA 4438) | 10 | 100 | 90% | Miconazole |

| Candida albicans (ATCC 36082) | 10 | 100 | 90% | Amphotericin B |

| Aspergillus niger (ATCC 1015) | 30 | 100 | 70% | Miconazole |

| Microsporum canis (ATCC 10214) | 10 | 100 | 90% | Miconazole |

| Fusarium lini (VNRL 2204) | 30 | 100 | 70% | Miconazole |

| Candida glabrata (ATCC 2001) | 30 | 100 | 70% | Miconazole |

| Aspergillus fumigatus (Clinical isolate) | 10 | 100 | 90% | Miconazole |

| Variables | Label | Units | Low (−1) | High (+1) | Mean (0) | Standard Deviation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reaction time | A | min | 30.00 | 60.00 | 15.00 | 75.00 | 45.00 | 13.65 |

| CuO-NPs dose | B | mg | 20.00 | 50.00 | 05.00 | 65.00 | 35.00 | 13.65 |

| NOR dose | C | ppm | 20.00 | 45.00 | 07.50 | 57.50 | 32.50 | 11.37 |

| pH | D | units | 05.00 | 10.00 | 02.50 | 12.50 | 07.50 | 02.27 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Farooq, U.; Khan, M.E.; Mohammad, A.; Hasan, N.; Alamri, A.A.; Sharma, M. Sustainable Synthesis of Copper Oxide Nanoparticles: Data-Driven Photocatalysis, Pt-Free Hydrogen Production, and Antibacterial Assessment. Catalysts 2025, 15, 1163. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121163

Farooq U, Khan ME, Mohammad A, Hasan N, Alamri AA, Sharma M. Sustainable Synthesis of Copper Oxide Nanoparticles: Data-Driven Photocatalysis, Pt-Free Hydrogen Production, and Antibacterial Assessment. Catalysts. 2025; 15(12):1163. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121163

Chicago/Turabian StyleFarooq, Umar, Mohammad Ehtisham Khan, Akbar Mohammad, Nazim Hasan, Abdullah Ali Alamri, and Mukul Sharma. 2025. "Sustainable Synthesis of Copper Oxide Nanoparticles: Data-Driven Photocatalysis, Pt-Free Hydrogen Production, and Antibacterial Assessment" Catalysts 15, no. 12: 1163. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121163

APA StyleFarooq, U., Khan, M. E., Mohammad, A., Hasan, N., Alamri, A. A., & Sharma, M. (2025). Sustainable Synthesis of Copper Oxide Nanoparticles: Data-Driven Photocatalysis, Pt-Free Hydrogen Production, and Antibacterial Assessment. Catalysts, 15(12), 1163. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121163