Controlled Sequential Oxygenation of Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids with a Recombinant Unspecific Peroxygenase from Aspergillus niger

Abstract

1. Introduction

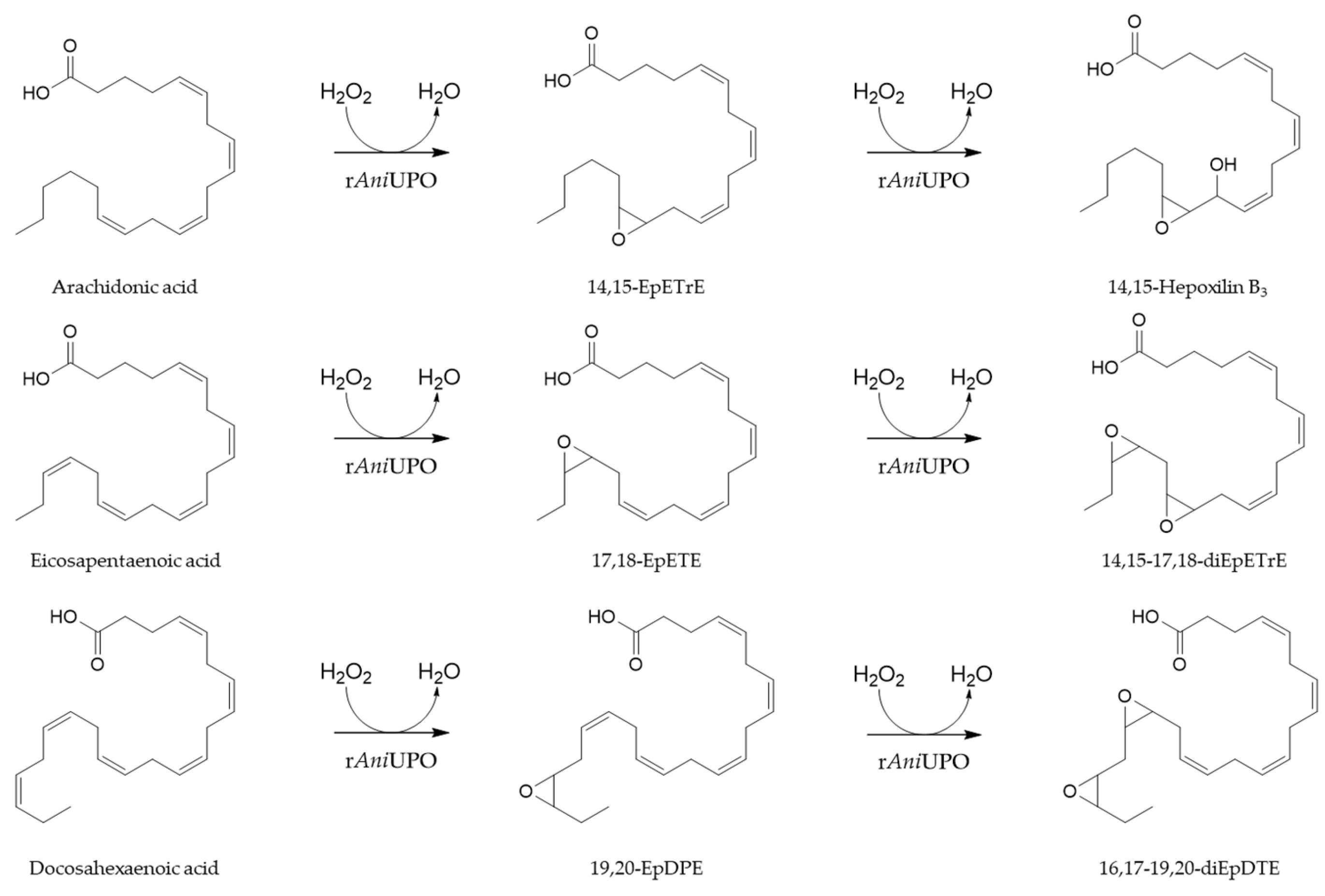

2. Results

2.1. Enzyme Testing

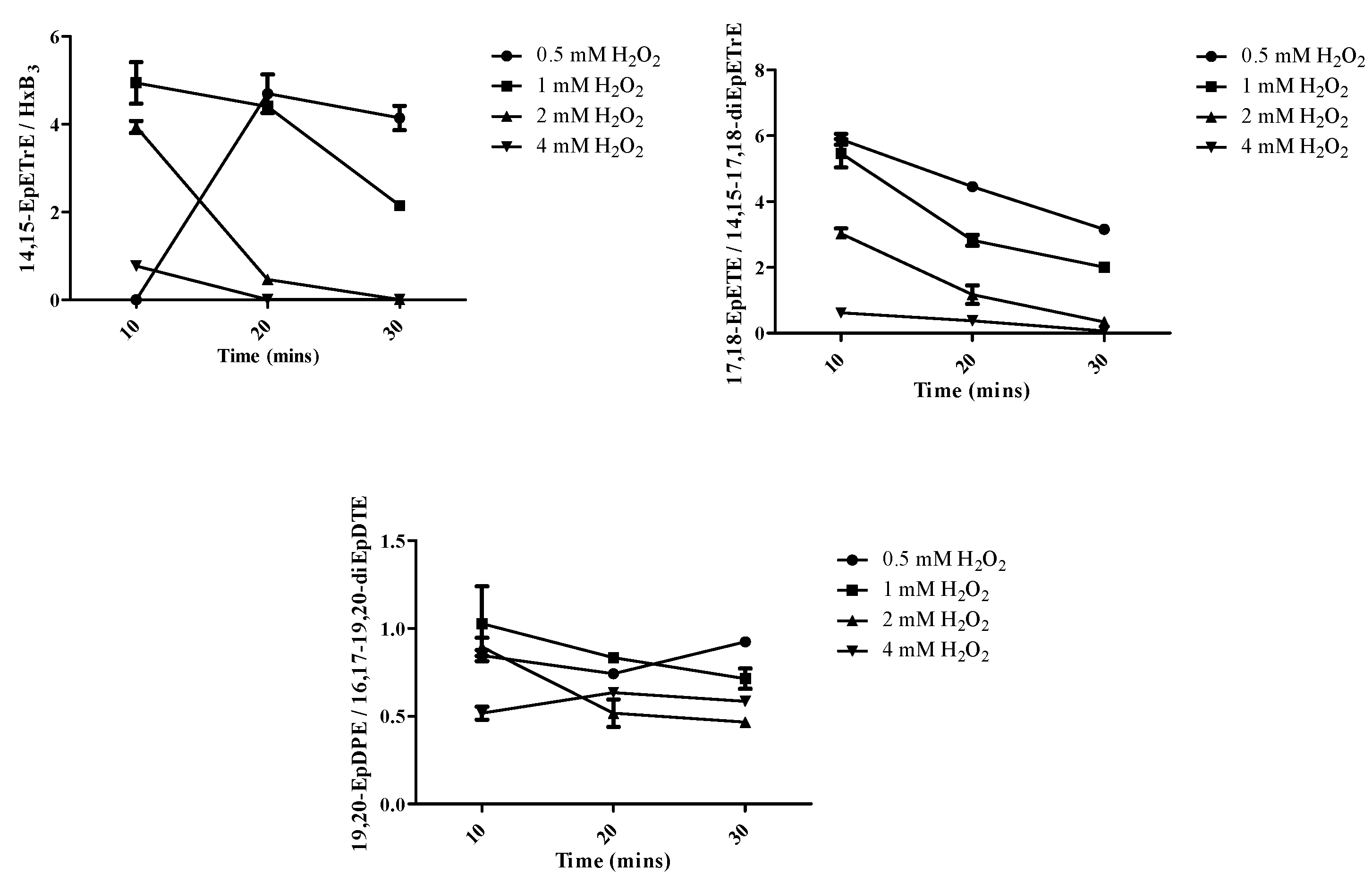

2.2. Role of Hydrogen Peroxide in Mono- and Di-Oxygenated Product Formation

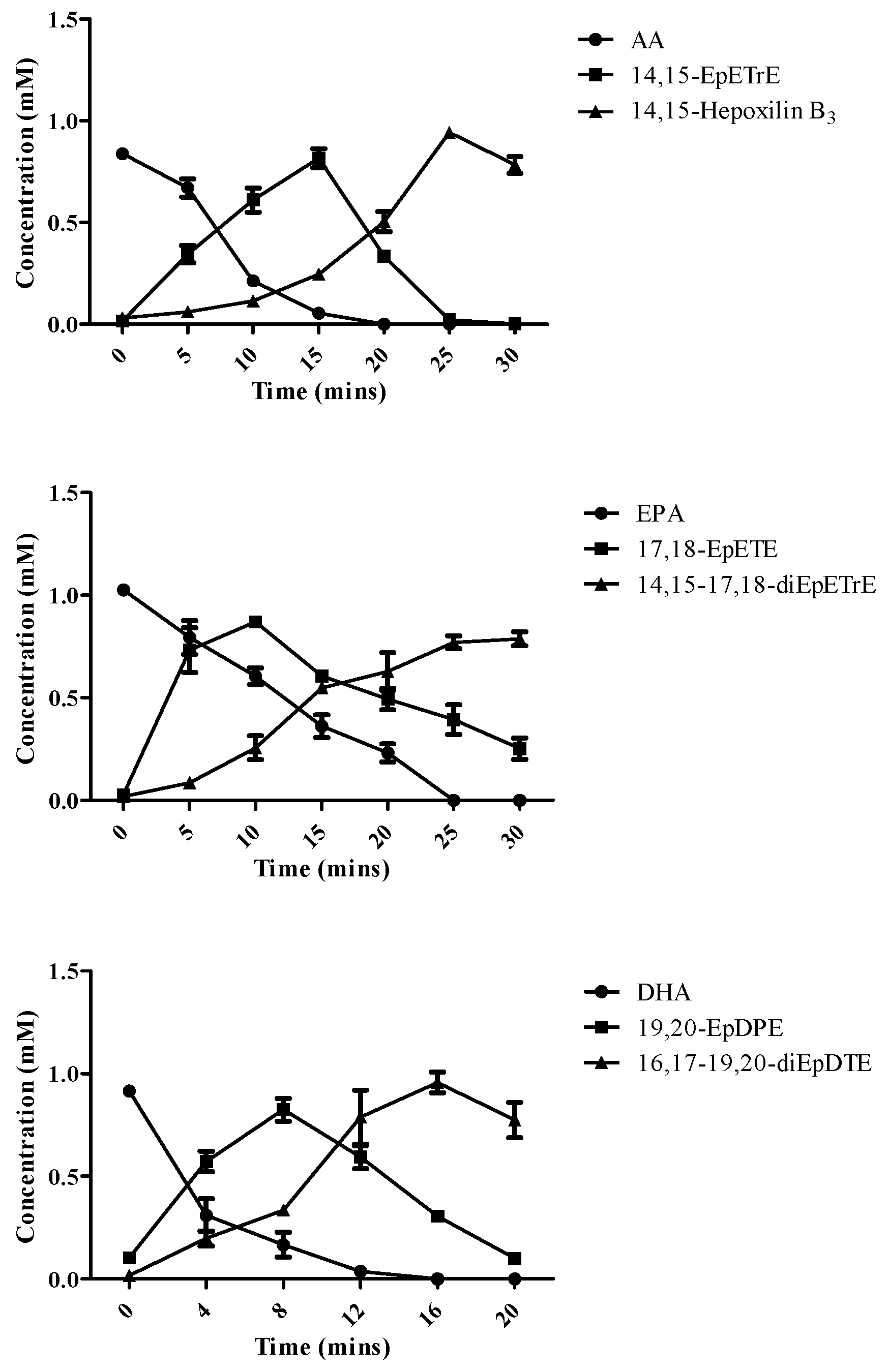

2.3. Time Course of Product Formation at Larger Scale

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Chemicals

4.2. Enzymes

4.3. Enzymatic Test for AA, EPA and DHA

4.4. Evaluation of Hydrogen Peroxide Dependence

4.5. Upscaling and Time Course of EpFA Synthesis

4.6. Analytical Methods

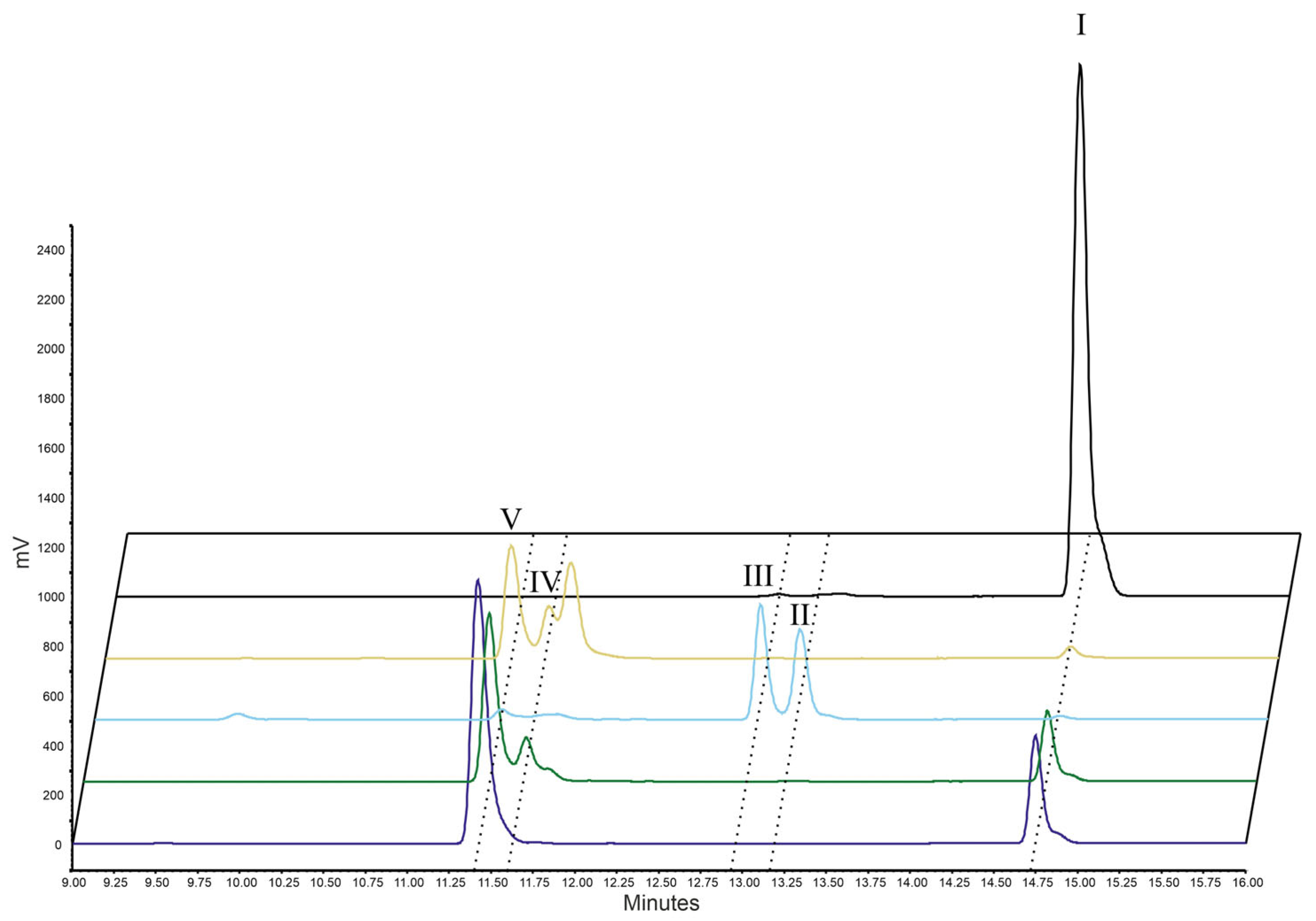

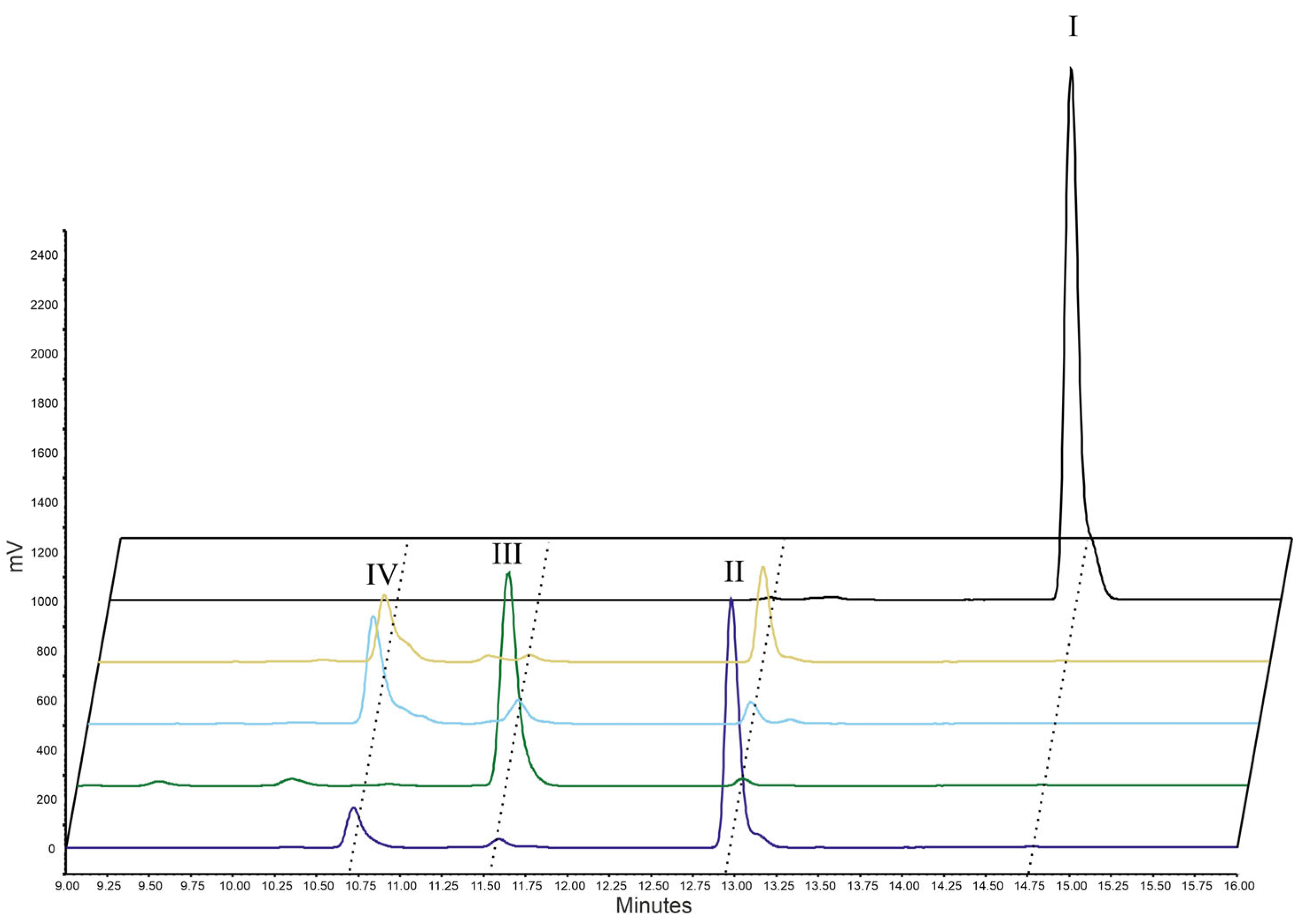

4.6.1. Preparative HPLC Chromatography

4.6.2. HPLC-ELSD

4.6.3. UHPLC Coupled with High Resolution Mass Spectrometry

4.6.4. NMR

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 11,12;14,15-diEpEDE | 11,12-14,15-diepoxyeicosadienoic acid |

| 11,12-EpETrE | 11,12-epoxyeicosatrienoic acid |

| 14,15;17,18-diEpETrE | 14,15-17,18-diepoxyeicosatrienoic acid |

| 14,15-EpETrE | 14,15-epoxyeicosatrienoic acid |

| 14,15-HxB3 | 14,15-Hepoxilin B3 |

| 16,17;19,20-diEpDTE | 16,17-19,20-diepoxydocosatetraenoic acid |

| 17,18-EpETE | 17,18-epoxyeicosatetraenoic acid |

| 19,20-EpDPE | 19,20-epoxydocosapentaenoic acid |

| AA | Arachidonic acid |

| CglUPO | Unspecific peroxygenase from Chaetomium globosum |

| CYP | Cytochrome P450 monooxygenase |

| DHA | Docosahexaenoic acid |

| diHFA | Dihydroxy fatty acid |

| EPA | Eicosapentaenoic acid |

| EpFA | Epoxy fatty acid |

| MroUPO | Unspecific peroxygenase from Marasmius rotula |

| PaDa-I UPO | Recombinant mutant of an unspecific peroxygenase from Agrocybe aegerita |

| PAA | Polyacrylic acid |

| rAniUPO | Recombinant unspecific peroxygenase from Aspergillus niger |

| rPabUPO-I | Recombinant unspecific peroxygenase I from Psathyrella (syn. Candolleomyces) abendarensis |

| rPabUPO-II | Recombinant unspecific peroxygenase II from Psathyrella (syn. Candolleomyces) abendarensis |

| sEH | Soluble epoxide hydrolase |

| TanUPO | Unspecific peroxygenase from Truncatella angustata |

| TOF | Turnover frequency |

| UPO | Unspecific peroxygenase |

References

- Marion-Letellier, R.; Savoye, G.; Ghosh, S. Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids and Inflammation. IUBMB Life 2015, 67, 659–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salter, A.M. Dietary Fatty Acids and Cardiovascular Disease. Animal 2013, 7, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricciotti, E.; FitzGerald, G.A. Prostaglandins and Inflammation. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2011, 31, 986–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Crooks, S.W.; Stockley, R.A. Leukotriene B4. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 1998, 30, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heller, A.; Koch, T.; Schmeck, J.; van Ackern, K. Lipid Mediators in Inflammatory Disorders. Drugs 1998, 55, 487–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serhan, C.N.; Chiang, N.; Van Dyke, T.E. Resolving Inflammation: Dual Anti-Inflammatory and pro-Resolution Lipid Mediators. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2008, 8, 349–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajeyah, A.A.; Griffiths, W.J.; Wang, Y.; Finch, A.J.; O’Donnell, V.B. The Biosynthesis of Enzymatically Oxidized Lipids. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 591819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morisseau, C.; Kodani, S.D.; Kamita, S.G.; Yang, J.; Lee, K.S.S.; Hammock, B.D. Relative Importance of Soluble and Microsomal Epoxide Hydrolases for the Hydrolysis of Epoxy-Fatty Acids in Human Tissues. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darwesh, A.M.; Fang, L.; Altamimi, T.R.; Jamieson, K.L.; Bassiouni, W.; Valencia, R.; Huang, A.; Wang, F.; Zhang, H.; Ahmed, M.; et al. Cardioprotective Effect of 19,20-Epoxydocosapentaenoic Acid (19,20-EDP) in Ischaemic Injury Involves Direct Activation of Mitochondrial Sirtuin 3. Cardiovasc. Res. 2024, 121, cvae252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, G.J.; Hsu, A.; Falck, J.R.; Nithipatikom, K. Mechanisms by Which Epoxyeicosatrienoic Acids (EETs) Elicit Cardioprotection in Rat Hearts. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2007, 42, 687–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morin, C.; Fortin, S.; Rousseau, E. 19,20-EpDPE, a Bioactive CYP450 Metabolite of DHA Monoacyglyceride, Decreases Ca2+ Sensitivity in Human Pulmonary Arteries. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2011, 301, H1311–H1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tajima, Y.; Ishikawa, M.; Maekawa, K.; Murayama, M.; Senoo, Y.; Nishimaki-Mogami, T.; Nakanishi, H.; Ikeda, K.; Arita, M.; Taguchi, R.; et al. Lipidomic Analysis of Brain Tissues and Plasma in a Mouse Model Expressing Mutated Human Amyloid Precursor Protein/Tau for Alzheimer’s Disease. Lipids Health Dis. 2013, 12, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, N.; Yang, C.; Fan, Q.; Wang, M.; Liu, X.; Zhao, H.; Zhao, C. The Anti-Inflammatory Effect of Soluble Epoxide Hydrolase Inhibitor and 14, 15-EET in Kawasaki Disease Through PPARγ/STAT1 Signaling Pathway. Front. Pediatr. 2020, 8, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Xu, X.; Wu, H.; Yang, J.; Chen, J.; Morisseau, C.; Hammock, B.D.; Bettaieb, A.; Zhao, L. Differential Effects of 17,18-EEQ and 19,20-EDP Combined with Soluble Epoxide Hydrolase Inhibitor t-TUCB on Diet-Induced Obesity in Mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khot, S.N.; Lascala, J.J.; Can, E.; Morye, S.S.; Williams, G.I.; Palmese, G.R.; Kusefoglu, S.H.; Wool, R.P. Development and Application of Triglyceride-Based Polymers and Composites. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2001, 82, 703–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juita; Dlugogorski, B.Z.; Kennedy, E.M.; Mackie, J.C. Low Temperature Oxidation of Linseed Oil: A Review. Fire Sci. Rev. 2012, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Larock, R.C. Vegetable Oil-Based Polymeric Materials: Synthesis, Properties, and Applications. Green Chem. 2010, 12, 1893–1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borugadda, V.B.; Goud, V.V. Epoxidation of Castor Oil Fatty Acid Methyl Esters (COFAME) as a Lubricant Base Stock Using Heterogeneous Ion-Exchange Resin (IR-120) as a Catalyst. Energy Procedia 2014, 54, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supanchaiyamat, N.; Shuttleworth, P.S.; Hunt, A.J.; Clark, J.H.; Matharu, A.S. Thermosetting Resin Based on Epoxidised Linseed Oil and Bio-Derived Crosslinker. Green Chem. 2012, 14, 1759–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Ding, R.; Kessler, M.R. Reduction of Epoxidized Vegetable Oils: A Novel Method to Prepare Bio-Based Polyols for Polyurethanes. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2014, 35, 1068–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Li, Y.; Chen, R.; Kessler, M.R. Polyurethanes from Solvent-Free Vegetable Oil-Based Polyols. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2014, 2, 2465–2476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, P.; Zhang, M.; Hu, L.; Zhou, Y. Green Plasticizers Derived from Soybean Oil for Poly(Vinyl Chloride) as a Renewable Resource Material. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2016, 33, 1080–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandula, S.; Stolp, L.; Grass, M.; Woldt, B.; Kodali, D. Synthesis and Functional Evaluation of Soy Fatty Acid Methyl Ester Ketals as Bioplasticizers. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2014, 91, 1967–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S.H.; Wagner, K.; Xu, J.; Yang, J.; Li, X.; Cao, Z.; Morisseau, C.; Lee, K.S.S.; Hammock, B.D. Chemical Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of ω-Hydroxy Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2017, 27, 620–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scala, J.L.; Wool, R.P. The Effect of Fatty Acid Composition on the Acrylation Kinetics of Epoxidized Triacylglycerols. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2002, 79, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, J.-J.; Heo, S.-Y.; Ju, J.-H.; Oh, B.-R.; Son, W.S.; Seo, J.-W. Synthesis of Two New Lipid Mediators from Docosahexaenoic Acid by Combinatorial Catalysis Involving Enzymatic and Chemical Reaction. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 18849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campanella, A.; La Scala, J.J.; Wool, R.P. The Use of Acrylated Fatty Acid Methyl Esters as Styrene Replacements in Triglyceride-Based Thermosetting Polymers. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2009, 49, 2384–2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, P.H.; Zhang, W.V.; Hook, J.; Tattam, B.N.; Duke, C.C.; Murray, M. Synthesis and NMR Characterization of the Methyl Esters of Eicosapentaenoic Acid Monoepoxides. Chem. Phys. Lipids 2009, 159, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devansh; Patil, P.; Pinjari, D.V. Oil-Based Epoxy and Their Composites: A Sustainable Alternative to Traditional Epoxy. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2024, 141, e55560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanfilippo, C.; Paterna, A.; Biondi, D.M.; Patti, A. Lyophilized Extracts from Vegetable Flours as Valuable Alternatives to Purified Oxygenases for the Synthesis of Oxylipins. Bioorganic Chem. 2019, 93, 103325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piazza, G.J.; Nuñez, A.; Foglia, T.A. Epoxidation of Fatty Acids, Fatty Methyl Esters, and Alkenes by Immobilized Oat Seed Peroxygenase. J. Mol. Catal. B Enzym. 2003, 21, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, C.; Schwab, W. Epoxidation, Hydroxylation and Aromatization Is Catalyzed by a Peroxygenase from Solanum lycopersicum. J. Mol. Catal. B Enzym. 2013, 96, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonafini, S.; Giontella, A.; Tagetti, A.; Marcon, D.; Montagnana, M.; Benati, M.; Gaudino, R.; Cavarzere, P.; Karber, M.; Rothe, M.; et al. Possible Role of CYP450 Generated Omega-3/Omega-6 PUFA Metabolites in the Modulation of Blood Pressure and Vascular Function in Obese Children. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borsini, A.; Nicolaou, A.; Camacho-Muñoz, D.; Kendall, A.C.; Di Benedetto, M.G.; Giacobbe, J.; Su, K.-P.; Pariante, C.M. Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids Protect against Inflammation through Production of LOX and CYP450 Lipid Mediators: Relevance for Major Depression and for Human Hippocampal Neurogenesis. Mol. Psychiatry 2021, 26, 6773–6788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullrich, R.; Nüske, J.; Scheibner, K.; Spantzel, J.; Hofrichter, M. Novel Haloperoxidase from the Agaric Basidiomycete Agrocybe aegerita Oxidizes Aryl Alcohols and Aldehydes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004, 70, 4575–4581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranda, C.; Municoy, M.; Guallar, V.; Kiebist, J.; Scheibner, K.; Ullrich, R.; del Río, J.C.; Hofrichter, M.; Martínez, A.T.; Gutiérrez, A. Selective Synthesis of 4-Hydroxyisophorone and 4-Ketoisophorone by Fungal Peroxygenases. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2019, 9, 1398–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez de Santos, P.; Cañellas, M.; Tieves, F.; Younes, S.H.H.; Molina-Espeja, P.; Hofrichter, M.; Hollmann, F.; Guallar, V.; Alcalde, M. Selective Synthesis of the Human Drug Metabolite 5′-Hydroxypropranolol by an Evolved Self-Sufficient Peroxygenase. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 4789–4799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiebist, J.; Schmidtke, K.-U.; Zimmermann, J.; Kellner, H.; Jehmlich, N.; Ullrich, R.; Zänder, D.; Hofrichter, M.; Scheibner, K. A Peroxygenase from Chaetomium globosum Catalyzes the Selective Oxygenation of Testosterone. ChemBioChem 2017, 18, 563–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinbrecht, S.; Kiebist, J.; König, R.; Thiessen, M.; Schmidtke, K.-U.; Kammerer, S.; Küpper, J.-H.; Scheibner, K. Synthesis of Cyclophosphamide Metabolites by a Peroxygenase from Marasmius rotula for Toxicological Studies on Human Cancer Cells. AMB Express 2020, 10, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiebist, J.; Schmidtke, K.-U.; Schramm, M.; König, R.; Quint, S.; Kohlmann, J.; Zuhse, R.; Ullrich, R.; Hofrichter, M.; Scheibner, K. Biocatalytic Syntheses of Antiplatelet Metabolites of the Thienopyridines Clopidogrel and Prasugrel Using Fungal Peroxygenases. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiebist, J.; Hofrichter, M.; Zuhse, R.; Scheibner, K. Oxyfunctionalization of Pharmaceuticals by Fungal Peroxygenases. In Pharmaceutical Biocatalysis; Jenny Stanford Publishing: Singapore, 2019; ISBN 978-0-429-35311-6. [Google Scholar]

- Hofrichter, M.; Kellner, H.; Herzog, R.; Karich, A.; Liers, C.; Scheibner, K.; Kimani, V.W.; Ullrich, R. Fungal Peroxygenases: A Phylogenetically Old Superfamily of Heme Enzymes with Promiscuity for Oxygen Transfer Reactions. In Grand Challenges in Fungal Biotechnology; Nevalainen, H., Ed.; Grand Challenges in Biology and Biotechnology; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 369–403. ISBN 978-3-030-29541-7. [Google Scholar]

- Hofrichter, M.; Kellner, H.; Herzog, R.; Karich, A.; Kiebist, J.; Scheibner, K.; Ullrich, R. Peroxide-Mediated Oxygenation of Organic Compounds by Fungal Peroxygenases. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, W.X.Q.; Mielke, T.; Melling, B.; Cuetos, A.; Parkin, A.; Unsworth, W.P.; Cartwright, J.; Grogan, G. Comparing the Catalytic and Structural Characteristics of a ‘Short’ Unspecific Peroxygenase (UPO) Expressed in Pichia pastoris and Escherichia coli. ChemBioChem 2023, 24, e202200558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schramm, M.; Friedrich, S.; Schmidtke, K.-U.; Kiebist, J.; Panzer, P.; Kellner, H.; Ullrich, R.; Hofrichter, M.; Scheibner, K. Cell-Free Protein Synthesis with Fungal Lysates for the Rapid Production of Unspecific Peroxygenases. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walter, R.M.; Zemella, A.; Schramm, M.; Kiebist, J.; Kubick, S. Vesicle-Based Cell-Free Synthesis of Short and Long Unspecific Peroxygenases. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 964396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedrich, S.; Schramm, M.; Kiebist, J.; Schmidtke, K.-U.; Scheibner, K. Development of Translationally Active Cell Lysates from Different Filamentous Fungi for Application in Cell-Free Protein Synthesis. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 2025, 185, 110588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Benjumea, A.; Marques, G.; Herold-Majumdar, O.M.; Kiebist, J.; Scheibner, K.; del Río, J.C.; Martínez, A.T.; Gutiérrez, A. High Epoxidation Yields of Vegetable Oil Hydrolyzates and Methyl Esters by Selected Fungal Peroxygenases. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 8, 605854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Benjumea, A.; Linde, D.; Carro, J.; Ullrich, R.; Hofrichter, M.; Martínez, A.T.; Gutiérrez, A. Regioselective and Stereoselective Epoxidation of N-3 and n-6 Fatty Acids by Fungal Peroxygenases. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carro, J.; González-Benjumea, A.; Fernández-Fueyo, E.; Aranda, C.; Guallar, V.; Gutiérrez, A.; Martínez, A.T. Modulating Fatty Acid Epoxidation vs Hydroxylation in a Fungal Peroxygenase. ACS Catal. 2019, 9, 6234–6242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Benjumea, A.; Carro, J.; Renau-Mínguez, C.; Linde, D.; Fernández-Fueyo, E.; Gutiérrez, A.; Martínez, A.T. Fatty Acid Epoxidation by Collariella virescens Peroxygenase and Heme-Channel Variants. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2020, 10, 717–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friesen, R.W.; Innis, S.M. Dietary Arachidonic Acid to EPA and DHA Balance Is Increased among Canadian Pregnant Women with Low Fish Intake. J. Nutr. 2009, 139, 2344–2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham-Lorence, S.; Truan, G.; Peterson, J.A.; Falck, J.R.; Wei, S.; Helvig, C.; Capdevila, J.H. An Active Site Substitution, F87V, Converts Cytochrome P450 BM-3 into a Regio- and Stereoselective (14S,15R)-Arachidonic Acid Epoxygenase. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 1127–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, K.M.; Gomes, A.; McReynolds, C.B.; Hammock, B.D. Soluble Epoxide Hydrolase Regulation of Lipid Mediators Limits Pain. Neurotherapeutics 2020, 17, 900–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Visser, S.P.; Ogliaro, F.; Sharma, P.K.; Shaik, S. What Factors Affect the Regioselectivity of Oxidation by Cytochrome P450? A DFT Study of Allylic Hydroxylation and Double Bond Epoxidation in a Model Reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 11809–11826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pace-Asciak, C.R. Pathophysiology of the Hepoxilins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA-Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2015, 1851, 383–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siangjong, L.; Goldman, D.H.; Kriska, T.; Gauthier, K.M.; Smyth, E.M.; Puli, N.; Kumar, G.; Falck, J.R.; Campbell, W.B. Vascular Hepoxilin and Trioxilins Mediate Vasorelaxation through TP Receptor Inhibition in Mouse Arteries. Acta Physiol. 2017, 219, 188–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubala, S.A.; Patil, S.U.; Shreffler, W.G.; Hurley, B.P. Pathogen Induced Chemo-Attractant Hepoxilin A3 Drives Neutrophils, but Not Eosinophils across Epithelial Barriers. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2014, 108, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Brunnström, Å.; Hamberg, M.; Griffiths, W.J.; Mannervik, B.; Claesson, H.-E. Biosynthesis of 14,15-Hepoxilins in Human L1236 Hodgkin Lymphoma Cells and Eosinophils. Lipids 2011, 46, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Kim, T.-H.; Oh, D.-K. Bioconversion of Arachidonic Acid into Human 14,15-Hepoxilin B3 and 13,14,15-Trioxilin B3 by Recombinant Cells Expressing Microbial 15-Lipoxygenase without and with Epoxide Hydrolase. Biotechnol. Lett. 2020, 42, 2001–2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoieb, S.M.; Dakarapu, R.; Falck, J.R.; El-Kadi, A.O.S. Novel Synthetic Analogues of 19(S/R)-Hydroxyeicosatetraenoic Acid Exhibit Noncompetitive Inhibitory Effect on the Activity of Cytochrome P450 1A1 and 1B1. Eur. J. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 2021, 46, 613–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoieb, S.M.; El-Kadi, A.O.S. S-Enantiomer of 19-Hydroxyeicosatetraenoic Acid Preferentially Protects Against Angiotensin II-Induced Cardiac Hypertrophy. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2018, 46, 1157–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidayat, R.; Shoieb, S.M.; Mosa, F.E.S.; Barakat, K.; Brocks, D.R.; Isse, F.A.; Gerges, S.H.; El-Kadi, A.O.S. 16R-HETE and 16S-HETE Alter Human Cytochrome P450 1B1 Enzyme Activity Probably through an Allosteric Mechanism. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2024, 479, 1379–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porretti, M.; Impellitteri, F.; Caferro, A.; Albergamo, A.; Litrenta, F.; Filice, M.; Imbrogno, S.; Di Bella, G.; Faggio, C. Assessment of the Effects of Non-Phthalate Plasticizer DEHT on the Bivalve Molluscs Mytilus galloprovincialis. Chemosphere 2023, 336, 139273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherepanova, A.; Savel’ev, E.; Alieva, L.; Kuznetsova, I.; Sapunov, V. A New Green Method for the Production Polyvinylchloride Plasticizers from Fatty Acid Methyl Esters of Vegetable Oils. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2020, 97, 1265–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandula, S.; Stolp, L.; Grass, M.; Woldt, B.; Kodali, D. Functionalization of Soy Fatty Acid Alkyl Esters as Bioplasticizers. J. Vinyl Addit. Technol. 2017, 23, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sustaita-Rodríguez, A.; Vega-Rios, A.; Bugarin, A.; Ramos-Sánchez, V.H.; Camacho-Dávila, A.A.; Rocha-Gutiérrez, B.; Chávez-Flores, D. Chemoenzymatic Epoxidation of Highly Unsaturated Fatty Acid Methyl Ester and Its Application as Poly(Lactic Acid) Plasticizer. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 17016–17024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanderNoot, V.A.; VanRollins, M. Capillary Electrophoresis of Cytochrome P-450 Epoxygenase Metabolites of Arachidonic Acid. 2. Resolution of Stereoisomers. Anal. Chem. 2002, 74, 5866–5870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeldin, D.C.; Wei, S.Z.; Falck, J.R.; Hammock, B.D.; Snapper, J.R.; Capdevila, J.H. Metabolism of Epoxyeicosatrienoic Acids by Cytosolic Epoxide Hydrolase: Substrate Structural Determinants of Asymmetric Catalysis. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1995, 316, 443–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daikh, B.E.; Lasker, J.M.; Raucy, J.L.; Koop, D.R. Regio- and Stereoselective Epoxidation of Arachidonic Acid by Human Cytochromes P450 2C8 and 2C9. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1994, 271, 1427–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, D.; Kisselev, P.; Ericksen, S.S.; Szklarz, G.D.; Chernogolov, A.; Honeck, H.; Schunck, W.-H.; Roots, I. Arachidonic and Eicosapentaenoic Acid Metabolism by Human CYP1A1: Highly Stereoselective Formation of 17(R),18(S)-Epoxyeicosatetraenoic Acid. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2004, 67, 1445–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, C.; Fischer, R.; Markovic, M.; Morisseau, C.; Hammock, B.D.; Schunck, W.-H. Stereoselective Hydrolysis of Epoxy-Eicosanoids by Mammalian Soluble Epoxide Hydrolases. FASEB J. 2008, 22, 479.32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynaud, D.; Ali, M.; Demin, P.; Pace-Asciak, C.R. Formation of 14,15-Hepoxilins of the A3 and B3 Series through a 15-Lipoxygenase and Hydroperoxide Isomerase Present in Garlic Roots*. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 28213–28218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullrich, R.; Poraj-Kobielska, M.; Scholze, S.; Halbout, C.; Sandvoss, M.; Pecyna, M.J.; Scheibner, K.; Hofrichter, M. Side Chain Removal from Corticosteroids by Unspecific Peroxygenase. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2018, 183, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- König, R.; Kiebist, J.; Kalmbach, J.; Herzog, R.; Schmidtke, K.-U.; Kellner, H.; Ullrich, R.; Jehmlich, N.; Hofrichter, M.; Scheibner, K. Novel Unspecific Peroxygenase from Truncatella angustata Catalyzes the Synthesis of Bioactive Lipid Mediators. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez de Santos, P.; González-Benjumea, A.; Fernandez-Garcia, A.; Aranda, C.; Wu, Y.; But, A.; Molina-Espeja, P.; Maté, D.M.; Gonzalez-Perez, D.; Zhang, W.; et al. Engineering a Highly Regioselective Fungal Peroxygenase for the Synthesis of Hydroxy Fatty Acids. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202217372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez de Santos, P.; Hoang, M.D.; Kiebist, J.; Kellner, H.; Ullrich, R.; Scheibner, K.; Hofrichter, M.; Liers, C.; Alcalde, M. Functional Expression of Two Unusual Acidic Peroxygenases from Candolleomyces aberdarensis in Yeasts by Adopting Evolved Secretion Mutations. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2021, 87, e00878-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monterrey, D.T.; Menés-Rubio, A.; Keser, M.; Gonzalez-Perez, D.; Alcalde, M. Unspecific Peroxygenases: The Pot of Gold at the End of the Oxyfunctionalization Rainbow? Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2023, 41, 100786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bormann, S.; Kellner, H.; Hermes, J.; Herzog, R.; Ullrich, R.; Liers, C.; Ulber, R.; Hofrichter, M.; Holtmann, D. Broadening the Biocatalytic Toolbox—Screening and Expression of New Unspecific Peroxygenases. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schramm, M.; Carrillo Avilés, C.R.; Kalmbach, J.; Schmidtke, K.-U.; Kiebist, J.; Kellner, H.; Hofrichter, M.; Scheibner, K. Rapid Screening System to Identify Unspecific Peroxygenase Activity*. Clin. Hemorheol. Microcirc. 2025, 89, 13860291241306566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otey, C.R. High-Throughput Carbon Monoxide Binding Assay for Cytochromes P450. In Directed Enzyme Evolution: Screening and Selection Methods; Arnold, F.H., Georgiou, G., Eds.; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2003; pp. 137–139. ISBN 978-1-59259-396-5. [Google Scholar]

| Enzymes | AA | EPA | DHA | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relative Conversion (%) 2 | Yield 14,15-EpETrE (%) | Relative Conversion Rate (%) | Yield 17,18-EpETE (%) | Relative Conversion Rate (%) | Yield 19,20-EpDPE (%) | |

| FettUPO (l) 3 | 62.2 ± 0.4 | - | 94.9 ± 0.2 | 50.9 ± 0.5 | 80.2 ± 0.3 | 50.8 ± 0.8 |

| rPabUPO-I (l) | 68.7 ± 0.8 | - | 88.6 ± 3.0 | 33.8 ± 2.0 | 86.9 ± 2.7 | 47.3 ± 1.7 |

| rPabUPO-II (l) | 96.0 ± 1.4 | 40.7 ± 0.6 | 95.6 ± 0.3 | 78.2 ± 0.9 | 97.6 ± 1.0 | 67.5 ± 0.4 |

| PaDa I UPO (l) | 90.3 ± 1.1 | - | 96.0 ± 0.2 | 73.5 ± 0.2 | 96.0 ± 2.1 | 76.3 ± 4.5 |

| MroUPO (s) | 97.6 ± 1.6 | 20.8 ± 0.9 | 97.8 ± 0.2 | - | 97.5 ± 0.6 | 16.2 ± 2.5 |

| TanUPO (s) | 97.9 ± 0.2 | 29.5 ± 7.3 | 98.2 ± 2.0 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 97.4 ± 0.8 | 9.0 ± 0.1 |

| rAniUPO (s) | 98.1 ± 0.1 | 58.4 ± 0.7 | 97.6 ± 0.3 | 12.8 ± 2.7 | 95.7 ± 0.2 | 21.5 ± 3.4 |

| CglUPO (s) | 97.1 ± 1.4 | 12.2 ± 0.6 | 96.5 ± 0.3 | - | 95.8 ± 0.5 | 8.1 ± 1.5 |

| Substrate | Products 1 | Yield (%) | TOF (h−1) 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| AA | 15.8 mg (14,15-Hepoxilin B3) | 43.2 | 939.2 |

| EPA | 22.1 mg (14,15-17,18-diEpETrE) | 60.8 | 1321.4 |

| DHA | 24.2 mg (16,17-19,20-diEpDTE) | 61.8 | 1798.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Carrillo Avilés, C.R.; Schramm, M.; Petzold, S.; Alcalde, M.; Hofrichter, M.; Scheibner, K. Controlled Sequential Oxygenation of Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids with a Recombinant Unspecific Peroxygenase from Aspergillus niger. Catalysts 2025, 15, 1162. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121162

Carrillo Avilés CR, Schramm M, Petzold S, Alcalde M, Hofrichter M, Scheibner K. Controlled Sequential Oxygenation of Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids with a Recombinant Unspecific Peroxygenase from Aspergillus niger. Catalysts. 2025; 15(12):1162. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121162

Chicago/Turabian StyleCarrillo Avilés, Carlos Renato, Marina Schramm, Sebastian Petzold, Miguel Alcalde, Martin Hofrichter, and Katrin Scheibner. 2025. "Controlled Sequential Oxygenation of Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids with a Recombinant Unspecific Peroxygenase from Aspergillus niger" Catalysts 15, no. 12: 1162. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121162

APA StyleCarrillo Avilés, C. R., Schramm, M., Petzold, S., Alcalde, M., Hofrichter, M., & Scheibner, K. (2025). Controlled Sequential Oxygenation of Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids with a Recombinant Unspecific Peroxygenase from Aspergillus niger. Catalysts, 15(12), 1162. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121162