Efficient Adsorptive Desulfurization of Dibenzothiophene Using Bimetallic Ni-Cr/ZSM-5 Zeolite Catalysts

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

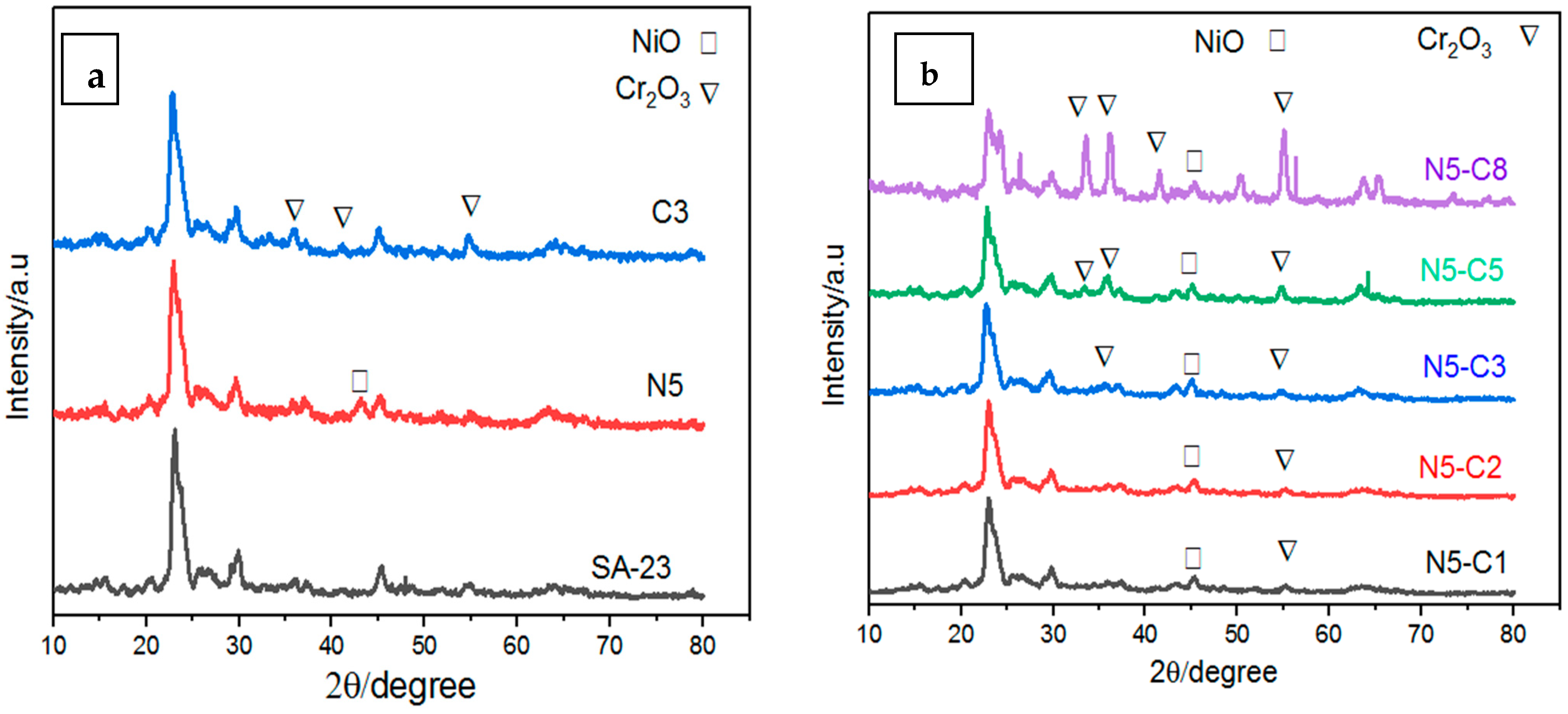

2.1. XRD Results of the Catalyst

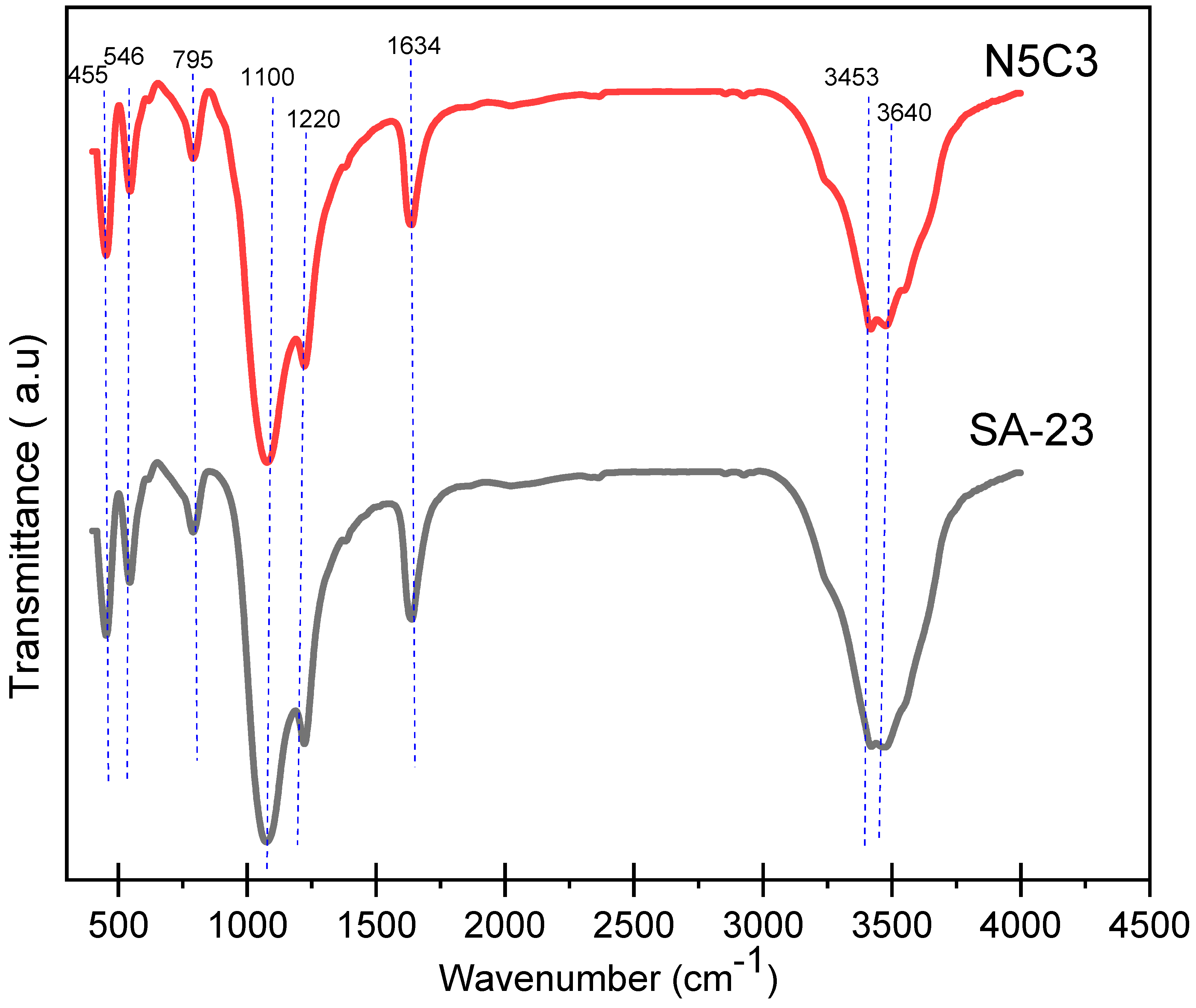

2.2. FTIR

2.3. BET

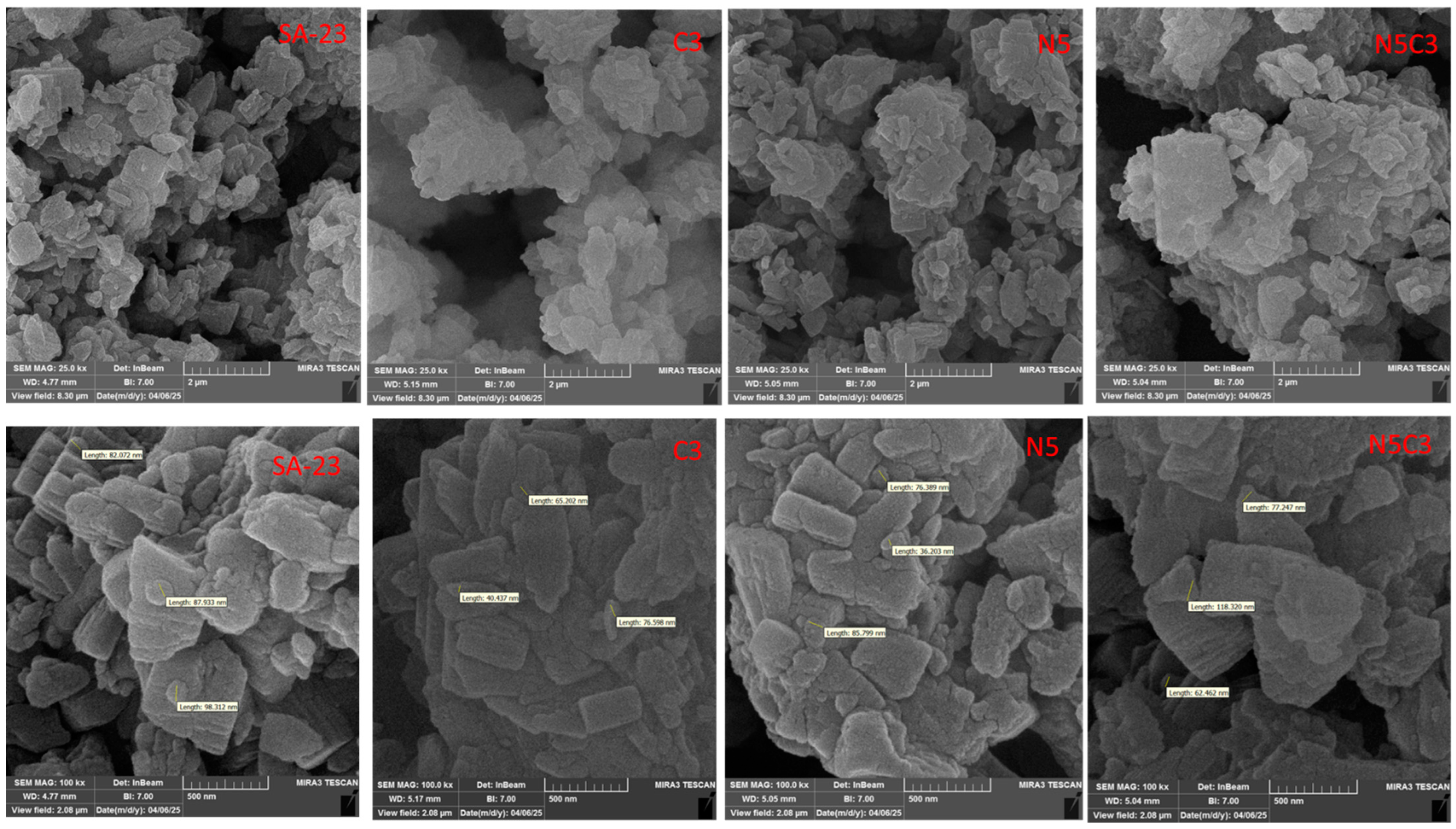

2.4. FESEM

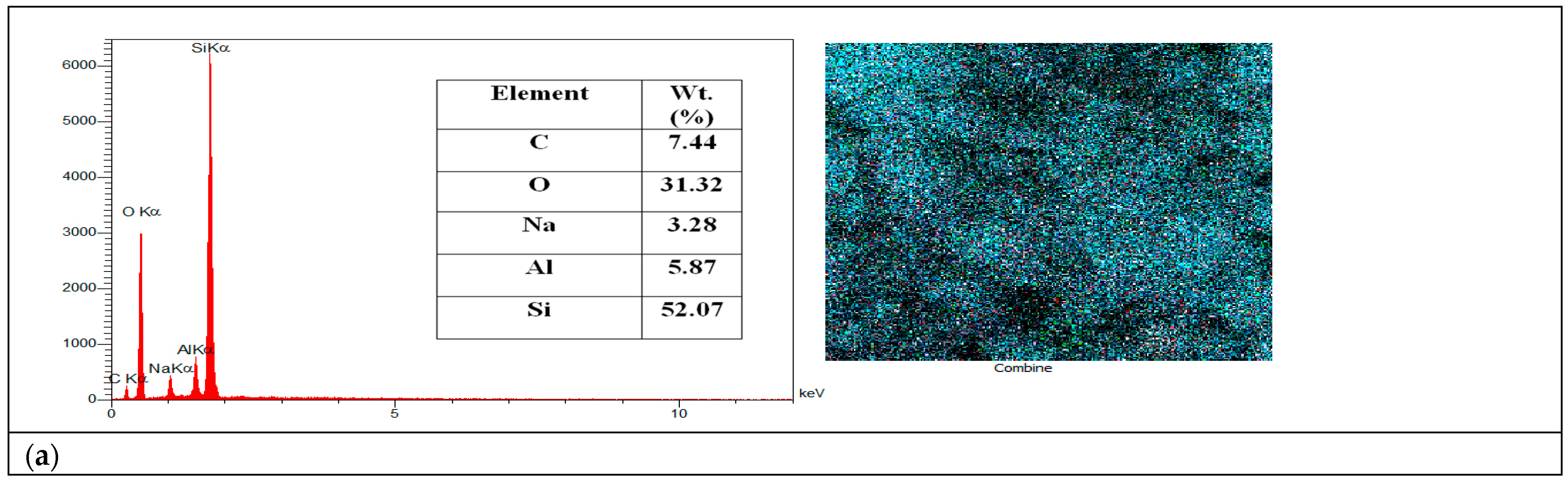

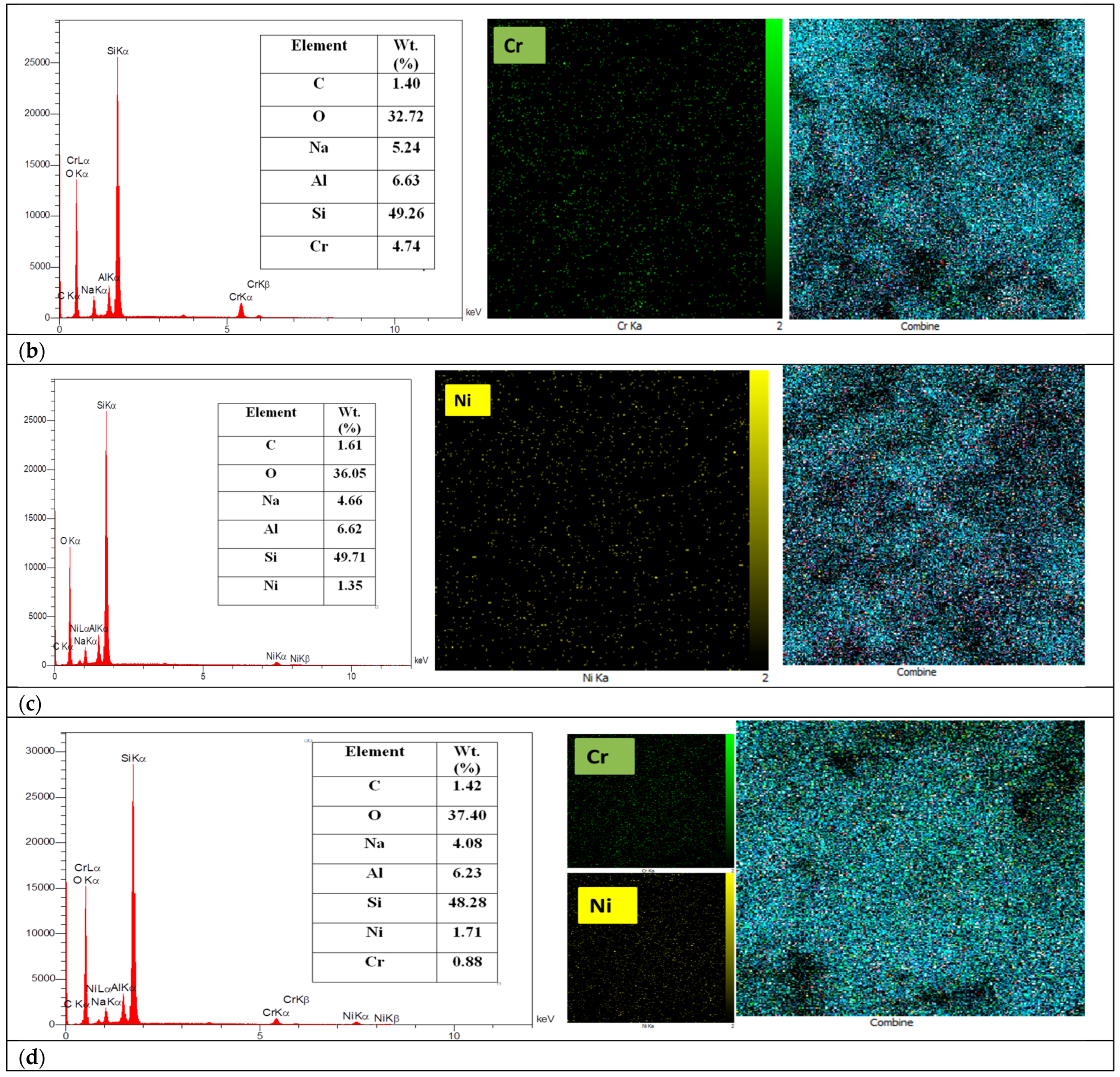

2.5. EDX Mapping

3. Discussion

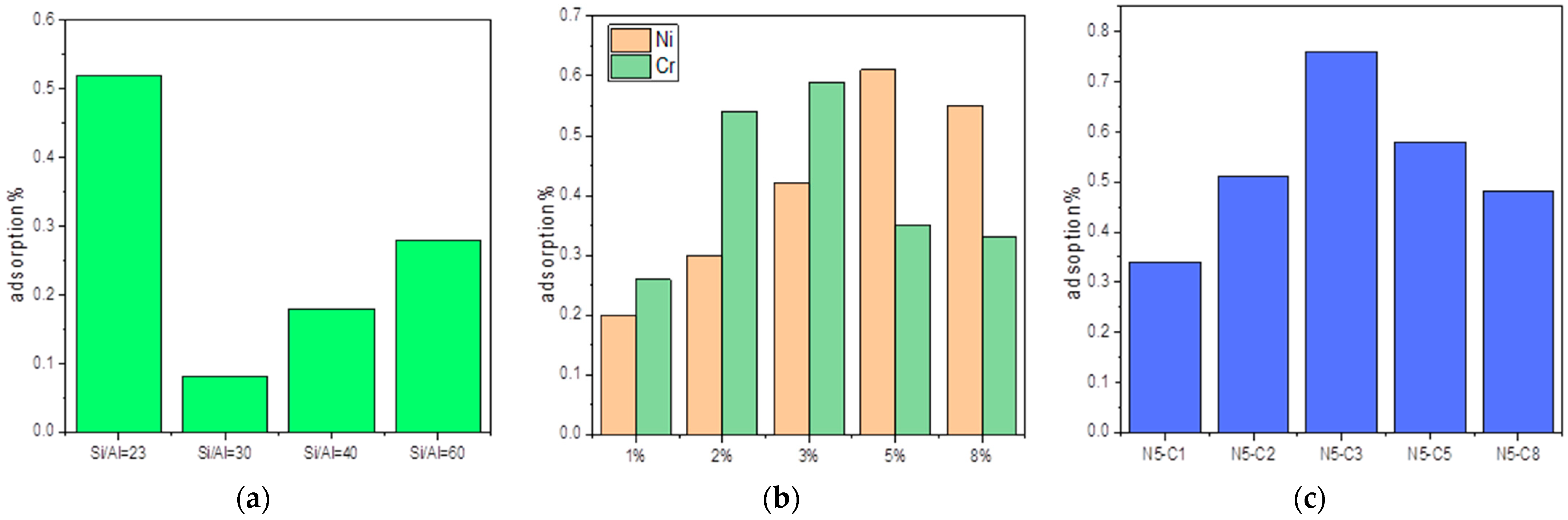

3.1. Effect of the Si/Al Ration

3.2. Performance of Either Ni or Cr Addition

3.3. Combined Ni and Cr Addition

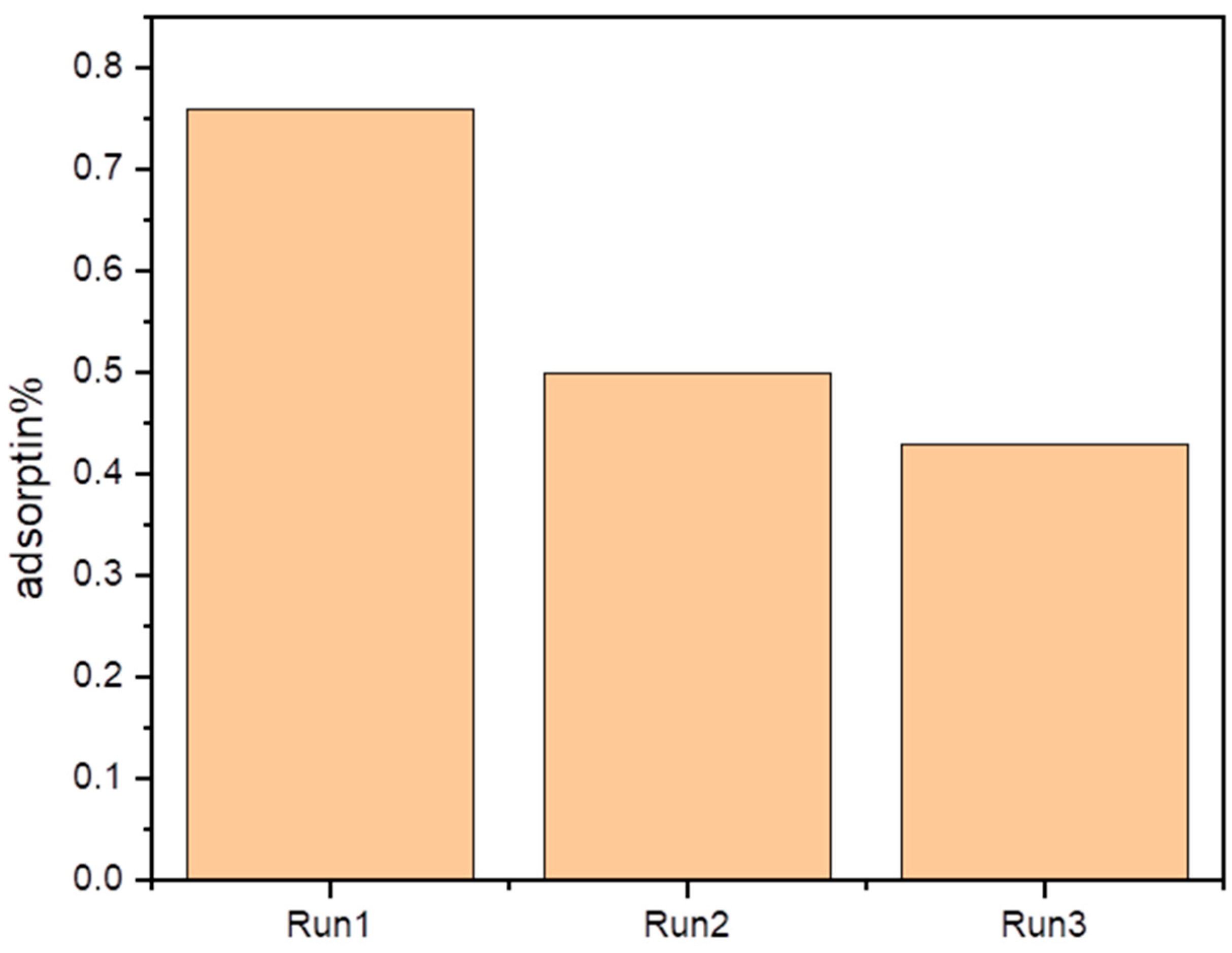

3.4. Stability and Reusability

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Characterization of Catalyst

4.3. Washing Zeolite with Sodium Hydroxide (NaOH)

4.4. Adding Metal to Zeolite

4.5. Adsorption Experiments

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Robinson, E.; Robbins, R.C. Gaseous sulfur pollutants from urban and natural sources. J. Air Pollut. Control Assoc. 1970, 20, 233–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullis, C.F.; Hirschler, M.M. Atmospheric sulphur: Natural and man-made sources. Atmos. Environ. 1980, 14, 1263–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, T.A. Advanced Desulfurization Technologies and Mechanisms. In Nanocomposites for the Desulfurization of Fuels; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2020; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava, V.C. An evaluation of desulfurization technologies for sulfur removal from liquid fuels. RSC Adv. 2012, 2, 759–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, B.R.; Brinich, B.L.; Male, J.L.; Hubbard, R.L.; Siddiqui, M.N.; Saleh, T.A.; Tyler, D.R. Enhanced oxidative desulfurization in a film-shear reactor. Fuel 2015, 156, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Wang, X.; Deng, H.; Zhao, J.; Li, Y. Molecular mechanism and experimental study of fuel oil extractive desulfurization technology based on ionic liquid. J. Energy Inst. 2024, 112, 101452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, A.E.S.; Roces, S.; Dugos, N.; Wan, M.W. Oxidation by H2O2 of benzothiophene and dibenzothiophene over polyoxometalate catalysts assisted by ultrasound and mixing. Fuel 2016, 180, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garba, Z.N.; Zango, Z.U.; Adamu, H.; Haruna, A.; Menkiti, N.D.; Danmallam, U.N.; Ali, A.F.; Zango, M.U.; Ratanatamskul, C. A review on zeolites for adsorptive desulfurization of crude oil and natural gas. Prog. Eng. Sci. 2025, 2, 100063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haruna, A.; Merican, Z.M.A.; Musa, S.G.; Abubakar, S. Sulfur removal technologies from fuel oil for sustainable environment. Fuel 2022, 329, 125370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkarabad, K.M.; Ghaemi, A. Comprehensive review of desulfurization technologies: Performance, innovation, challenges and directions. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2025, 11, 101164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulut, B.; Atakül, H.; Aksoylu, A.E.; Tantekin-Ersolmaz, Ş.B. Deep adsorptive desulfurization of LPG over Cu–Y zeolite. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 338, 126431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Xu, Y.; Guo, K.; Zhang, P.; Zeng, Y. Adsorptive desulfurization using Cu+ modified UiO-66. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 108578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Ran, H.; Zhang, Y.; Yin, J.; Zhang, J.; He, J.; Jiang, W.; Zhu, L.; Li, H. Atomically dispersed aluminum sites in boron nitride nanofibers for desulfurization. Inorg. Chem. 2023, 62, 17883–17893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeole, N.R. Overview of adsorptive desulfurization using zeolites. Environ. Prog. Sustain. Energy 2023, 42, e13960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghan, R.; Anbia, M. Zeolites for adsorptive desulfurization from fuels. Fuel Process. Technol. 2017, 167, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Han, X.; Huang, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, L.; Cao, L.; Shen, B.; Gao, J.; Xu, C. Competitive adsorption desulfurization over K–doped NiY zeolite. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2016, 483, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarda, K.K.; Bhandari, A.; Pant, K.K.; Jain, S. Deep desulfurization of diesel via adsorption over Ni/Al2O3 and Ni/ZSM-5. Fuel 2012, 93, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subhan, F.; Aslam, S.; Yan, Z.; Liu, Z.; Etim, U.J.; Wadood, A.; Ullah, R. Mesoporous ZSM-5 functionalized with Ni NPs for desulfurization. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 354, 706–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Dong, L.; Zhao, L.; Cao, L.; Gao, J.; Xu, C. Alkali-treated mesoporous ZSM-5 for enhanced desulfurization. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2017, 56, 3813–3821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojeda, M.; Osterman, N.; Dražić, G.; Žilnik, L.F.; Meden, A.; Kwapinski, W.; Balu, A.M.; Likozar, B.; Tušar, N.N. Conversion of palmitic acid over Ni/ZSM-5 catalysts. Top. Catal. 2018, 61, 1757–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garba, Z.N.; Hamza, S.A.; Ratanatamskul, C. Cu–MCC adsorbent for crude oil–contaminated water. J. Water Process Eng. 2024, 67, 106293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Kong, F.; Zhou, R. Cr-Pt/ZSM-5 catalysts for CVOC removal. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 107629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thommes, M.; Kaneko, K.; Neimark, A.V.; Olivier, J.P.; Rodriguez-Reinoso, F.; Rouquerol, J.; Sing, K.S. Physisorption of gases for surface area measurement. Pure Appl. Chem. 2015, 87, 1051–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, R.; Stöcker, M.; Hansen, E.; Akporiaye, D.; Ellestad, O.H. MCM-41 as a model adsorption system. Microporous Mater. 1995, 3, 443–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabarish, R.; Unnikrishnan, G. ZSM-5 synthesis using starch. SN Appl. Sci. 2019, 1, 989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampouraki, Z.C.; Giannakoudakis, D.A.; Nair, V.; Hosseini-Bandegharaei, A.; Colmenares, J.C.; Deliyanni, E.A. MOFs for desulfurization. Molecules 2019, 24, 4525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kassaye, S.; Gupta, D.; Pant, K.K.; Jain, S. Valorization of MCC via protonated zeolite. Reactions 2022, 3, 283–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baamran, K.; Rownaghi, A.A. CO2 conversion over Cr2O3/ZSM-5@CaO. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 17783–17792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Liu, Y.; Tian, S.; Zhao, E.; Zhang, J.; Liu, C. NiPb/ZnO–diatomite–ZSM-5 for RDS. Fuel 2013, 104, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirazi, L.; Jamshidi, E.; Ghasemi, M.R. Effect of Si/Al ratio of ZSM-5. Cryst. Res. Technol. 2008, 43, 1300–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camplo, J.M.; Garcia, A.; Herencia, J.F.; Luna, D.; Marinas, J.M.; Romero, A.A. Conversion of alcohols on ALPO4 catalysts. J. Catal. 1999, 151, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Zheng, B.; Wu, G.; Ma, F.; Liu, C. Si/Al ratio effect on hierarchical ZSM-5. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 83581–83588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.-L.; Wang, H.Q.; Xiang, M.; Yu, P.; Li, R.Q.; Ke, Q.P. Ni-ZSM-5 for biomass pyrolysis. Front. Chem. 2020, 8, 790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mguni, L.L.; Nkomzwayo, T.; Yao, Y. Effect of support and NiO loading on desulfurization. Sep. Sci. Technol. 2024, 59, 122–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimura, K.; Yoshida, S.; Oikawa, H.; Fujitani, T. Ni-loading effects on NiO/SiO2–Al2O3. Catalysts 2023, 13, 1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Zheng, Y.; Tang, Y.; Jehng, J.-M.; Grybos, R.; Handzlik, J.; Wachs, I.E.; Podkolzin, S.G. Cr oxide structures on ZSM-5. ACS Catal. 2015, 5, 3078–3092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohiuddin, E.; Mdleleni, M.M.; Key, D. Cracking of naphtha over Fe/Cr-ZSM-5. Appl. Petrochem. Res. 2018, 8, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, E.; Bang, S.; Cho, J.H.; Jung, K.D.; Shin, C.H. Reductive amination over Ni–Fe/γ-Al2O3. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2017, 542, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambursa, M.M.; Ali, T.H.; Lee, H.V.; Sudarsanam, P.; Bhargava, S.K.; Abd Hamid, S.B. Hydrodeoxygenation of dibenzofuran. Fuel 2016, 180, 767–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Fu, J.; Zhu, H.; Zhao, Q.; Zhou, L. Ag/ZSM-5 zeolite for adsorptive desulfurization. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2022, 288, 120698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, G.; Khezeli, F.; Hemmati, H. Syngas production via dry reforming over Ni/ZSM-5. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2016, 33, 657–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample Name | Si/Al | BET (m2/g) | Pore Size | Total Pore Volume (p/p0 = 0.990) [cm3 g−1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SA-23 | 23 | 19.2 | 16.4 nm | 0.081957 |

| SA-30 | 30 | 7.6 | 40.7 nm | 0.075359 |

| SA-40 | 40 | 22 | 16.2 nm | 0.089594 |

| SA-60 | 60 | 9.5 | 1.2 nm | 0.070002 |

| Sample Name | Si/Al | Tdi (°C) | Amount of NH3 (mmol/g-cat) | Total Acidity (mmol/g Dry) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SA-23 | 23 | 195 | 1.505 | 2.608 |

| 510 | 1.103 | |||

| SA-30 | 30 | 189 | 1.145 | 2.351 |

| 514 | 1.205 | |||

| SA-40 | 40 | 192 | 0.987 | 2.358 |

| 520 | 1.370 | |||

| SA-60 | 60 | 192 | 0.678 | 2.207 |

| 523 | 1.520 |

| Sample Name | BET (m2/g) | Pore Size | Total Pore Volume (p/p0 = 0.990) [cm3 g−1] |

|---|---|---|---|

| N5C1 | 20.21 | 18.15 | 0.091716 |

| N5C2 | 16.15 | 19.63 | 0.079305 |

| N5C3 | 14.4 | 20.87 | 0.075148 |

| N5C5 | 17.15 | 18.94 | 0.081373 |

| N5C8 | 15.67 | 22.47 | 0.099283 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Juboori, S.A.-d.A.; Moradi, G. Efficient Adsorptive Desulfurization of Dibenzothiophene Using Bimetallic Ni-Cr/ZSM-5 Zeolite Catalysts. Catalysts 2025, 15, 1164. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121164

Juboori SA-dA, Moradi G. Efficient Adsorptive Desulfurization of Dibenzothiophene Using Bimetallic Ni-Cr/ZSM-5 Zeolite Catalysts. Catalysts. 2025; 15(12):1164. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121164

Chicago/Turabian StyleJuboori, Safa Al-deen A., and Gholamreza Moradi. 2025. "Efficient Adsorptive Desulfurization of Dibenzothiophene Using Bimetallic Ni-Cr/ZSM-5 Zeolite Catalysts" Catalysts 15, no. 12: 1164. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121164

APA StyleJuboori, S. A.-d. A., & Moradi, G. (2025). Efficient Adsorptive Desulfurization of Dibenzothiophene Using Bimetallic Ni-Cr/ZSM-5 Zeolite Catalysts. Catalysts, 15(12), 1164. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121164