Selective Dehydration of 1,3-Cyclopentanediol to Cyclopentadiene over Lanthanum Phosphate Catalysts

Abstract

1. Introduction

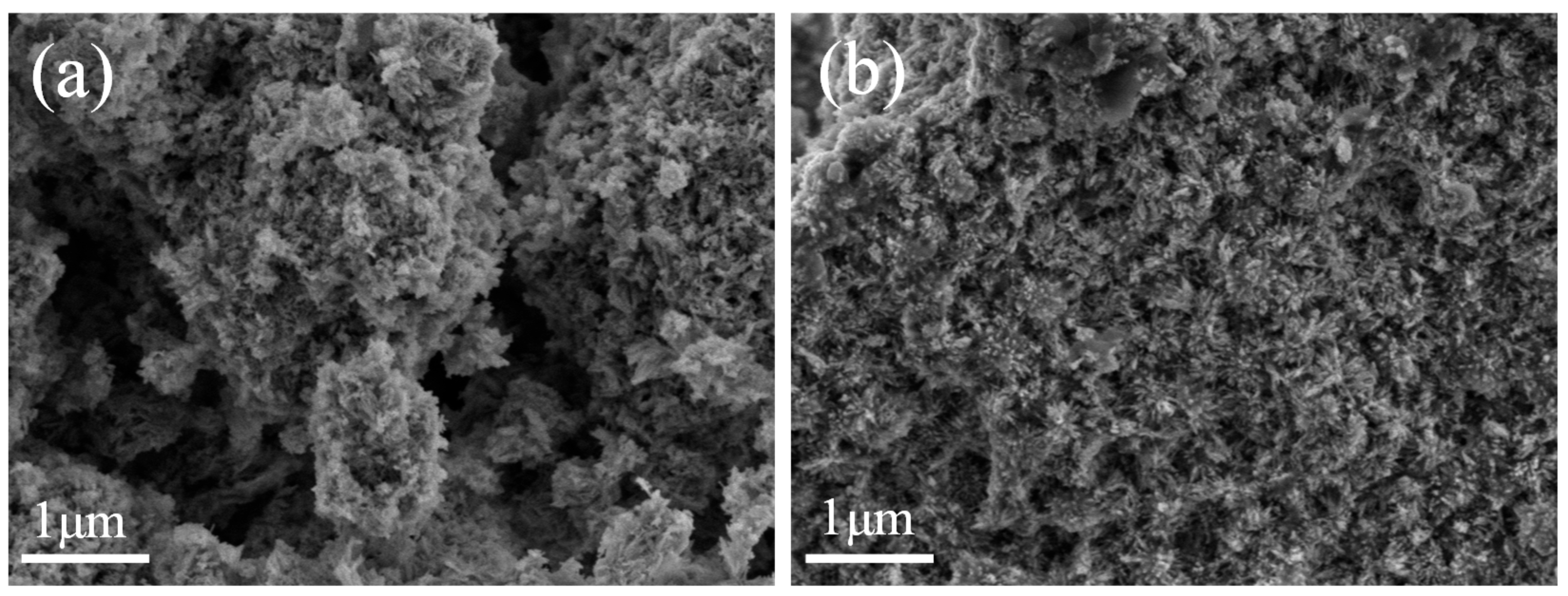

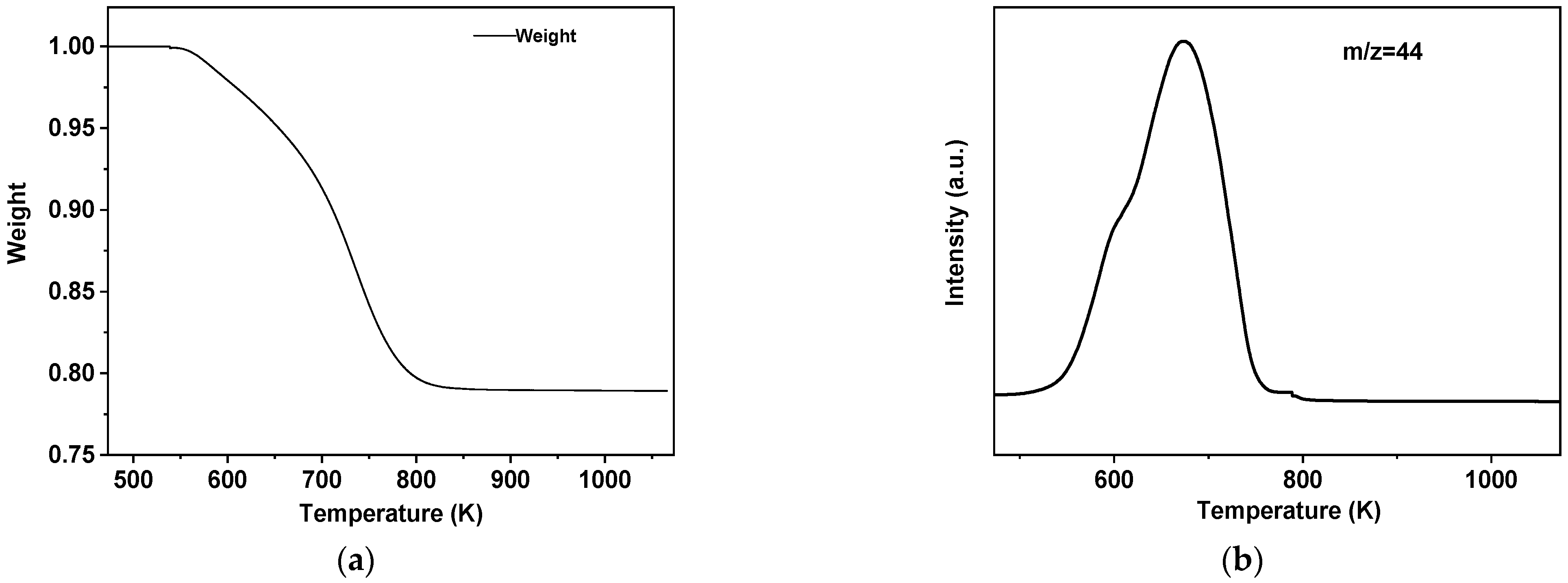

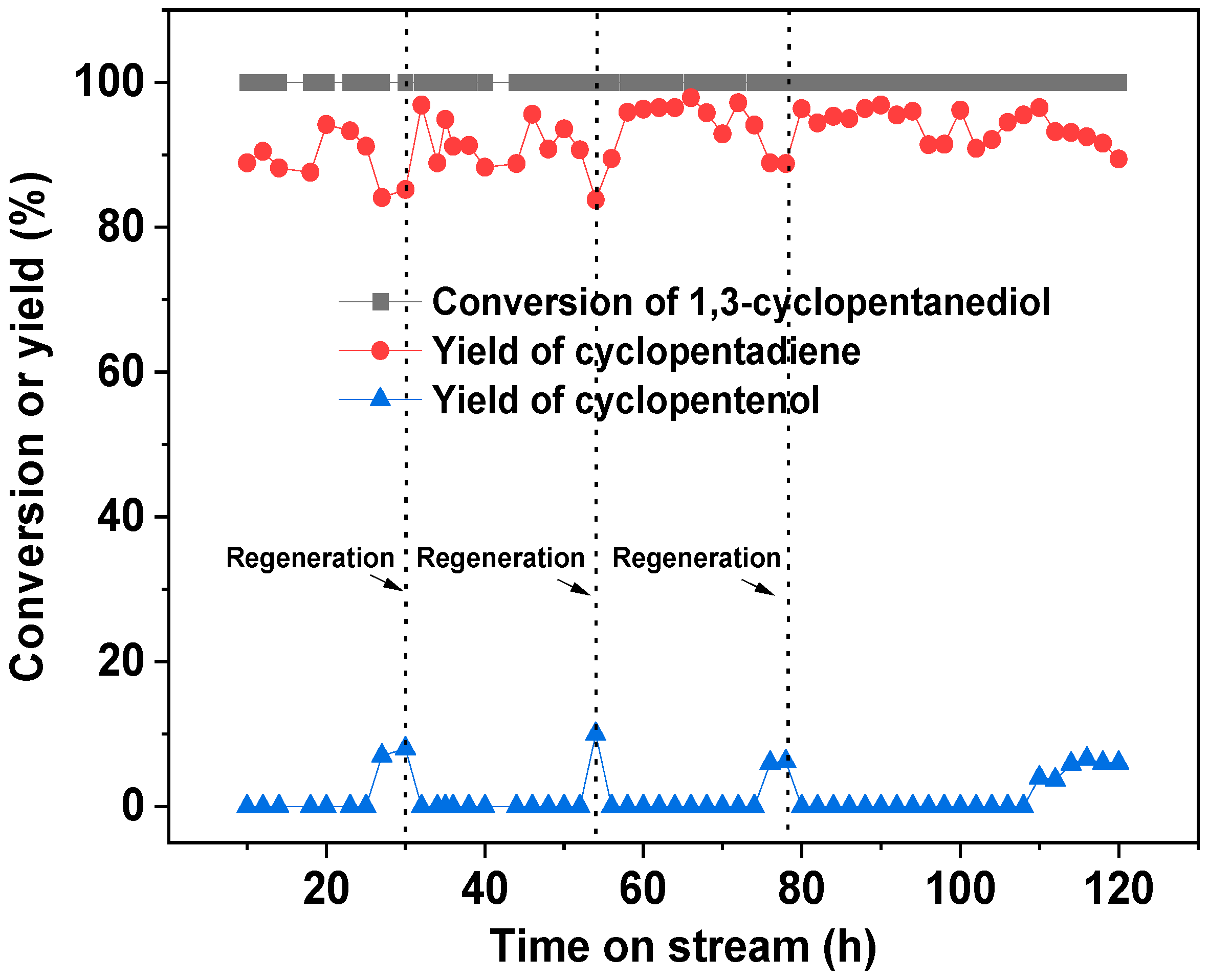

2. Results

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. Preparation of Catalysts

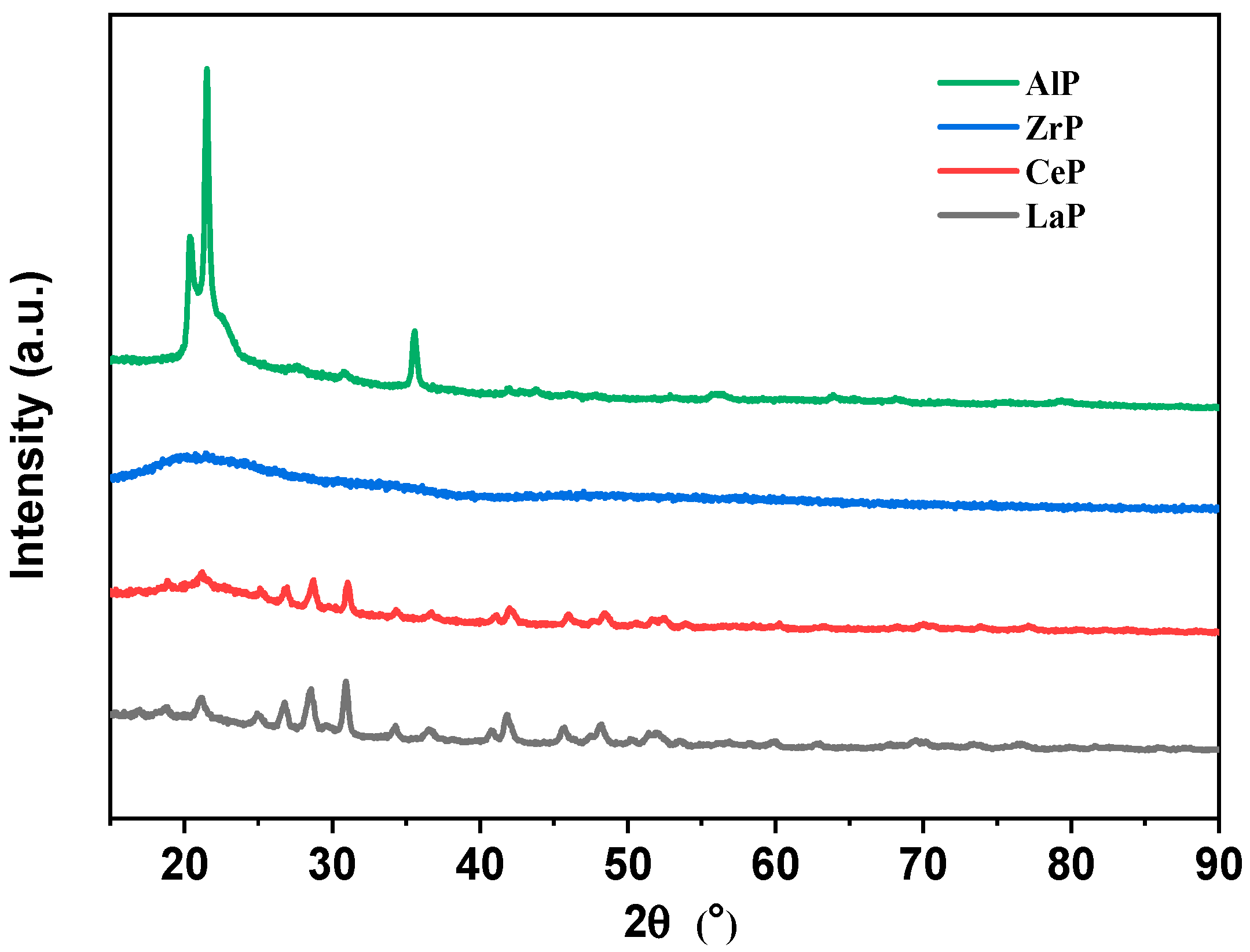

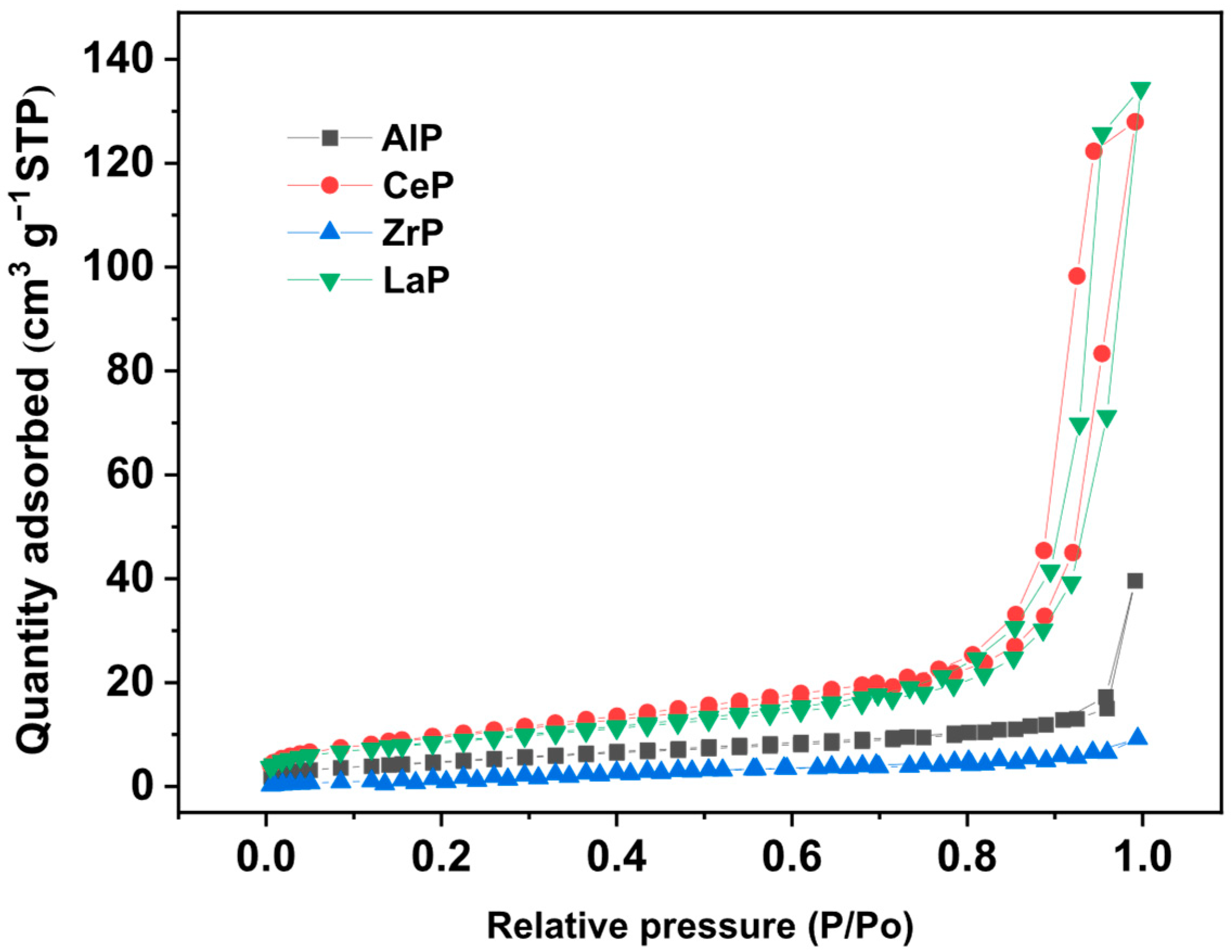

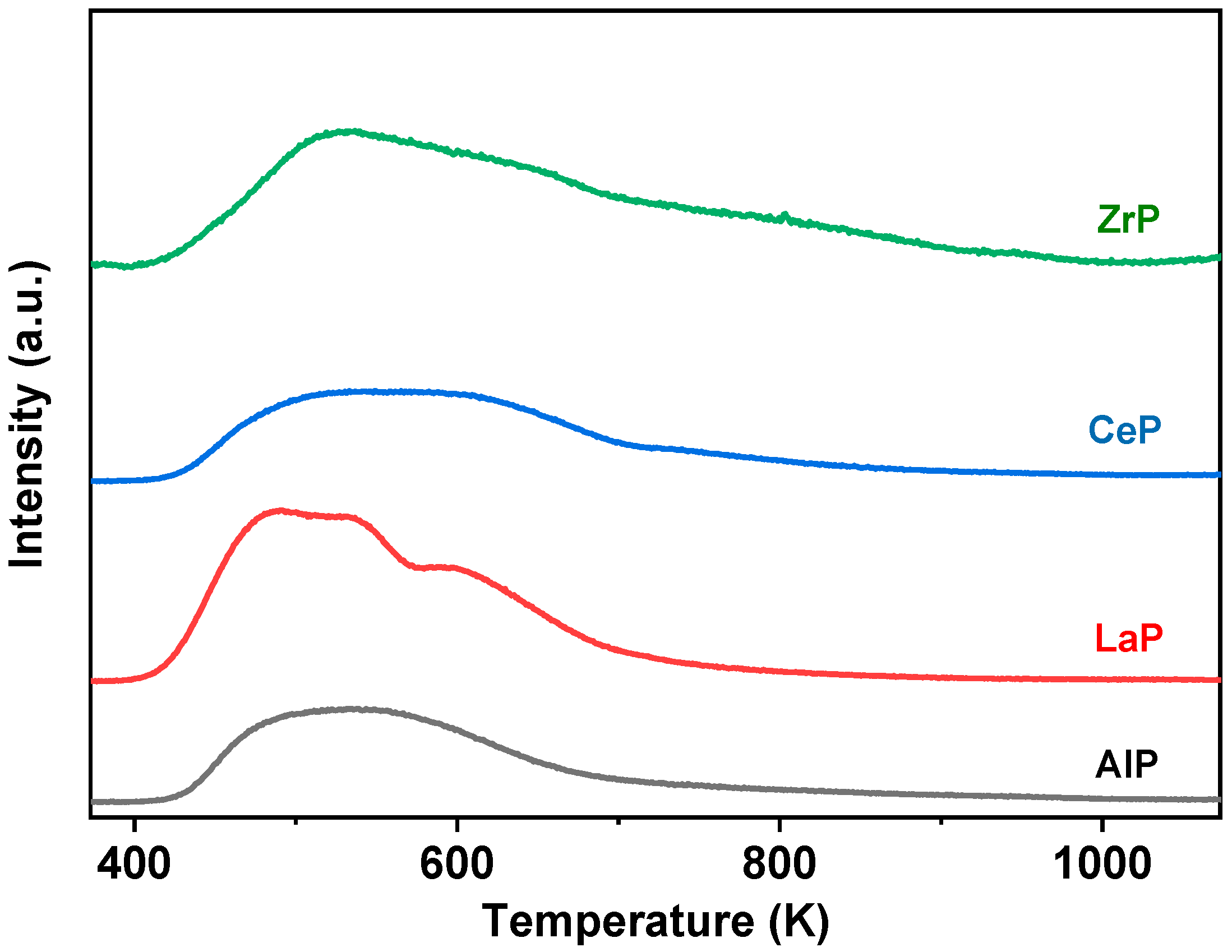

3.3. Catalyst Characterization

3.4. Dehydration of 1,3-Cyclopentanediol

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Huber, G.W.; Iborra, S.; Corma, A. Synthesis of transportation fuels from biomass: Chemistry, catalysts, and engineering. Chem. Rev. 2006, 106, 4044–4098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhao, X.; Wang, A.; Huber, G.W.; Zhang, T. Catalytic Transformation of Lignin for the Production of Chemicals and Fuels. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 11559–11624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Wang, R.; Pang, J.; Wang, A.; Li, N.; Zhang, T. Production of Renewable Hydrocarbon Biofuels with Lignocellulose and Its Derivatives over Heterogeneous Catalysts. Chem. Rev. 2024, 124, 2889–2954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, J.Q.; Upadhye, A.A.; Olcay, H.; Tompsett, G.A.; Jae, J.; Xing, R.; Alonso, D.M.; Wang, D.; Zhang, T.; Kumar, R.; et al. Production of renewable jet fuel range alkanes and commodity chemicals from integrated catalytic processing of biomass. Energy Environ. Sci. 2014, 7, 1500–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corma, A.; de la Torre, O.; Renz, M. Production of high quality diesel from cellulose and hemicellulose by the sylvan process: Catalysts and process variables. Energy Environ. Sci. 2012, 5, 6328–6344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, B.G.; Quintana, R.L. Synthesis of renewable jet and diesel fuels from 2-ethyl-1-hexene. Energy Environ. Sci. 2010, 3, 352–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Pan, L.; Nie, G.; Xie, J.; Liu, Y.; Ma, C.; Zhang, X.; Zou, J.-J. Photoinduced cycloaddition of biomass derivatives to obtain high-performance spiro-fuel. Green Chem. 2019, 21, 5886–5895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muldoon, J.A.; Harvey, B.G. Bio-Based Cycloalkanes: The Missing Link to High-Performance Sustainable Jet Fuels. ChemSusChem 2020, 13, 5777–5807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Besson, M.; Gallezot, P.; Pinel, C. Conversion of biomass into chemicals over metal catalysts. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 1827–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mika, L.T.; Cséfalvay, E.; Németh, Á. Catalytic Conversion of Carbohydrates to Initial Platform Chemicals: Chemistry and Sustainability. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 505–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, Y.; Guo, Y.; Xia, Q.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y. Catalytic Production of Value-Added Chemicals and Liquid Fuels from Lignocellulosic Biomass. Chem 2019, 5, 2520–2546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; Xia, Q.; Dong, L.; Liu, X.; Han, X.; Parker, S.F.; Cheng, Y.; Daemen, L.L.; Ramirez-Cuesta, A.J.; Yang, S.; et al. Selective production of arenes via direct lignin upgrading over a niobium-based catalyst. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 16104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.L.; Deng, W.P.; Wang, B.J.; Zhang, Q.H.; Wan, X.Y.; Tang, Z.C.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, C.; Cao, Z.X.; Wang, G.C.; et al. Chemical synthesis of lactic acid from cellulose catalysed by lead(II) ions in water. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 2141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.; Yan, J.; Wu, R.; Liu, H.; Sun, Y.; Wu, N.; Xiang, J.; Zheng, L.; Zhang, J.; Han, B. Sustainable production of benzene from lignin. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, W.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Gupta, K.M.; Hülsey, M.J.; Asakura, H.; Liu, L.; Han, Y.; Karp, E.M.; Beckham, G.T.; et al. Catalytic amino acid production from biomass-derived intermediates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 5093–5098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levandowski, B.J.; Raines, R.T. Click Chemistry with Cyclopentadiene. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 6777–6801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Pan, L.; Wang, L.; Zou, J.-J. Review on synthesis and properties of high-energy-density liquid fuels: Hydrocarbons, nanofluids and energetic ionic liquids. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2018, 180, 95–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claus, M.; Claus, E.; Claus, P.; Honicke, D.; Fodish, R.; Olson, M. ULLMANN’S Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry; Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA: Weinheim, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Li, G.; Hou, B.; Wang, A.; Xin, X.; Cong, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, N.; Zhang, T. Making JP-10 Superfuel Affordable with a Lignocellulosic Platform Compound. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 12154–12158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodroffe, J.-D.; Harvey, B.G. Synthesis of Bio-Based Methylcyclopentadiene from 2,5-Hexanedione: A Sustainable Route to High Energy Density Jet Fuels. ChemSusChem 2021, 14, 339–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, G.; Shi, C.; Dai, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Ma, C.; Liu, Q.; Pan, L.; Zhang, X.; Zou, J.-J. Producing methylcyclopentadiene dimer and trimer based high-performance jet fuels using 5-methyl furfural. Green Chem. 2020, 22, 7765–7768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Li, N.; Zheng, M.; Li, S.; Wang, A.; Cong, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, T. Industrially scalable and cost-effective synthesis of 1,3-cyclopentanediol with furfuryl alcohol from lignocellulose. Green Chem. 2016, 18, 3607–3613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, G.; Yu, H.; Xing, L.; Wang, A.; Wang, W.; Zhao, Z.; Li, N. Integration of bio-JP-10 synthetic route from furfuryl alcohol. Catal. Today 2025, 443, 114987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armaroli, T.; Busca, G.; Carlini, C.; Giuttari, M.; Raspolli Galletti, A.M.; Sbrana, G. Acid sites characterization of niobium phosphate catalysts and their activity in fructose dehydration to 5-hydroxymethyl-2-furaldehyde. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem. 2000, 151, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weingarten, R.; Tompsett, G.A.; Conner, W.C.; Huber, G.W. Design of solid acid catalysts for aqueous-phase dehydration of carbohydrates: The role of Lewis and Brønsted acid sites. J. Catal. 2011, 279, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pholjaroen, B.; Li, N.; Wang, Z.; Wang, A.; Zhang, T. Dehydration of xylose to furfural over niobium phosphate catalyst in biphasic solvent system. J. Energy Chem. 2013, 22, 826–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Theng, D.S.; Tang, K.Y.; Zhang, L.L.; Huang, L.; Borgna, A.; Wang, C. Dehydration of lactic acid to acrylic acid over lanthanum phosphate catalysts: The role of Lewis acid sites. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016, 18, 23746–23754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shivhare, A.; Kumar, A.; Srivastava, R. Metal phosphate catalysts to upgrade lignocellulose biomass into value-added chemicals and biofuels. Green Chem. 2021, 23, 3818–3841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, R.; Qi, Y.; Liu, S.; Cui, L.; Dai, Q.; Bai, C. Production of renewable 1,3-pentadiene over LaPO4 via dehydration of 2,3-pentanediol derived from 2,3-pentanedione. Appl. Catal. A 2022, 633, 118514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corma, A. Inorganic Solid Acids and Their Use in Acid-Catalyzed Hydrocarbon Reactions. Chem. Rev. 1995, 95, 559–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

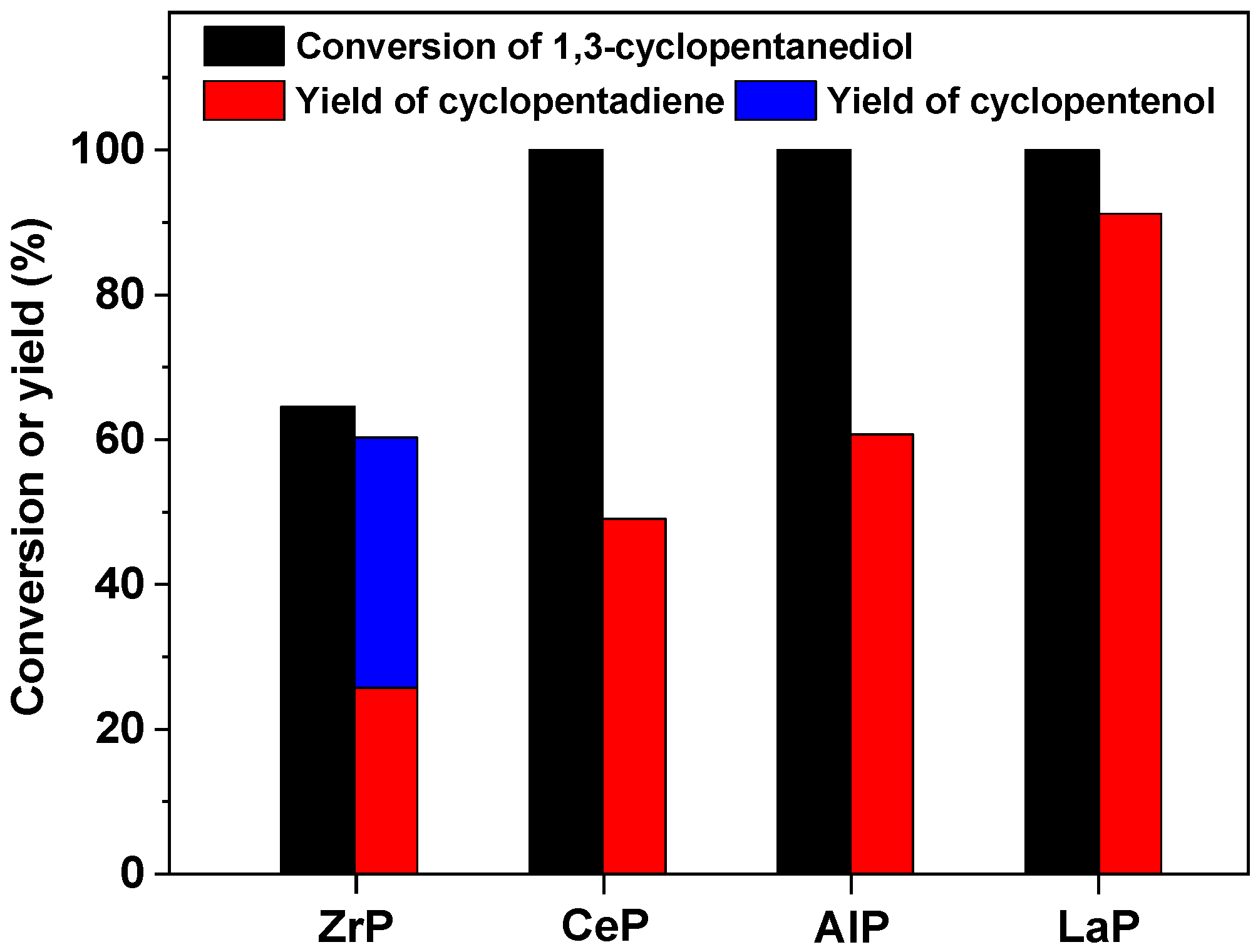

| Catalyst | SBET (m2 g−1) 1 | Average Pore Size (nm) 1 | Amount of Acid Sites (mmol g−1) 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| ZrP | 8.5 | 6.4 | 0.051 |

| CeP | 35.9 | 18.8 | 0.060 |

| AlP | 17.9 | 12.7 | 0.105 |

| LaP | 30.8 | 22.0 | 0.159 |

| Catalyst | SBET (m2 g−1) 1 | Average Pore Size (nm) 1 | Amount of Acid Sites (mmol g−1) 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fresh LaP | 30.8 | 22.0 | 0.159 |

| Used LaP | 19.0 | 14.6 | 0.113 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, H.; Zhang, X.; Sun, X.; Cong, Y.; Li, N. Selective Dehydration of 1,3-Cyclopentanediol to Cyclopentadiene over Lanthanum Phosphate Catalysts. Catalysts 2025, 15, 1125. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121125

Liu H, Zhang X, Sun X, Cong Y, Li N. Selective Dehydration of 1,3-Cyclopentanediol to Cyclopentadiene over Lanthanum Phosphate Catalysts. Catalysts. 2025; 15(12):1125. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121125

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Hao, Xing Zhang, Xiannian Sun, Yu Cong, and Ning Li. 2025. "Selective Dehydration of 1,3-Cyclopentanediol to Cyclopentadiene over Lanthanum Phosphate Catalysts" Catalysts 15, no. 12: 1125. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121125

APA StyleLiu, H., Zhang, X., Sun, X., Cong, Y., & Li, N. (2025). Selective Dehydration of 1,3-Cyclopentanediol to Cyclopentadiene over Lanthanum Phosphate Catalysts. Catalysts, 15(12), 1125. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121125