1. Introduction

The global edible oil industry is a crucial component of the food sector and the world economy. The considerable worldwide production of diverse oils reached a combined total of 223.8 million metric tons in 2024. This magnitude of production, achieved with bleaching earth dosages between 0.1% and 3% in oil refining, results in the generation of approximately 2.5 million tons of SBE annually [

1,

2].

The most widely used bleaching earths are acid-activated bentonites, considered fundamental for guaranteeing the quality of refined oil due to their large surface area and porosity, providing a remarkable adsorption capacity. During bleaching, these adsorbents mainly retain oxidation products, peroxides, pigments, fatty acids, residual salts, phosphatides, mucilages, trace metals, soaps, carotenoids, chlorophyll, tocopherols, and other undesirable compounds [

3,

4]. The presence of these impurities directly affects the appearance, taste, odor, and oxidative stability of the oil, thereby influencing its commercial acceptability. Chlorophyll imparts green hues, while carotenoids produce reddish or yellowish colors, making chlorophyll adsorption a common benchmark for evaluating bleaching efficiency [

5,

6].

However, the microporous structure of the clay, combined with its large surface area and the presence of retained oil and phosphorus, favors spontaneous auto-ignition, as rapid oxidation generates heat. This property poses significant risks during the handling, transportation, and final disposal of SBEs [

7]. Improper handling practices can have serious environmental consequences, including soil contamination, impairment of fertility, and bioaccumulation of heavy metals; water pollution due to the leaching of oils and pollutants; and air pollution from volatile organic compound emissions and odors that degrade air quality and affect nearby communities [

8,

9].

Placxedes et al. (2024) [

10] noted that the recovery of vegetable oil from SBEs and its subsequent reactivation offers numerous opportunities for cleaner production and cost savings in the vegetable oil processing industry. This finding highlights the need for sustainable strategies that reduce waste while adding value to a significant by-product of the refining process.

Various methods have been investigated for the reuse of SBFs including composting; use as a bioorganic fertilizer [

11] ingredient in animal feed, in situ biodiesel production [

12]; and reactivation for industrial reuse using various strategies such as the application of supercritical carbon dioxide extraction [

13] by heat [

14] and chemical treatments or solvent extraction [

7], or combinations of these methods [

14]. However, many of these technologies have significant limitations, such as high energy requirements (temperatures above 600 °C), the use of expensive and toxic solvents, and short reuse cycles [

11].

Previous studies have explored the enzymatic hydrolysis of SBEs for purposes other than reactivation. Tippkötter et al. (2014) demonstrated the use of glycerol obtained from the enzymatic hydrolysis of SBE as a substrate for Acetone–butanol–ethanol fermentation [

15]. Similarly, Park et al. (2008) and Kojima et al. (2004) applied lipase-catalyzed hydrolysis on SBEs to produce fatty acid methyl esters (FAMEs) as biodiesel precursors [

16,

17]. These works highlight the potential of enzymatic biocatalysis for valorizing spent bleaching earth, although none have focused on its regeneration and reuse as an adsorbent material.

Compared to these methods, enzymatic hydrolysis has emerged as a sustainable alternative for SBE reactivation due to its mild operating conditions and selective action [

18]. This method utilizes the catalytic power of enzymes to break down residual oils and impurities and restore the adsorption capacity of SBEs without the harsh chemical treatments often associated with traditional reactivation methods [

19,

20]. This gentler approach not only minimizes environmental impact but also preserves the structural integrity of the clay, which can extend its life cycle for multiple reuses in industrial applications.

In this context, this paper explores enzymatic hydrolysis as a novel and environmentally sustainable approach for SBE reactivation. Efficient SBE management is essential not only to mitigate environmental impact but also to enhance the economic sustainability of the edible oil industry. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report addressing the use of enzymatic hydrolysis for SBE reactivation, although processes catalyzed by lipase have been previously applied to SBEs for other valorization purposes This pioneering approach offers a promising alternative to conventional techniques, often associated with high energy demand and secondary pollutions.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Physicochemical Characterization of Bleached Soybean Oil

Table 1 summarizes the parameters measured at an intermediate stage of soybean oil refining (bleaching processes), which serve as critical indicators for process monitoring and compliance with edible oil industry standards (

Supplementary Material Figures S4–S8). The free fatty acid content was 0.28%, indicating an efficient neutralization step and minimal triglyceride hydrolysis during the preceding operation [

21,

22].

The color value, 70 yellow units and 5.3 red units, demonstrates a substantial reduction in pigments and chromophoric compounds, ensuring adequate feed quality for the deodorization stage. Residual phosphorus content (0.560 ppm) remained within the recommended threshold to prevent gum formation and thermal darkening during deodorization, while the low moisture level (0.20%) minimized the risk of hydrolytic and oxidative degradation reaction [

21,

23].

2.2. Characterization of Untreated Bleaching Earth (Virgin) and Soybean Oil SBEs

Table 2 summarizes the physicochemical analyses performed on both untreated bleaching earth (virgin) and SBEs, providing a reference for their original properties. Soybean oil SBEs usually contain a significant amount of retained oil along with phosphatides, which saturate the clay and deactivate its adsorption capacity for impurities [

24]. The content of retained oil in the SBEs (20%) was sufficiently high to evaluate the removal of phosphorus in the subsequent phases of this study.

The pH of the untreated bleaching earth (4.52) reflects the acidic nature of the material, resulting from the sulfuric acid activation used in Sepigel Active (Guadalajara, Spain) [

25]. The decrease in pH observed in the SBE (3.32) can be associated with the adsorption of free fatty acids and phosphatides present in the oil. This phenomenon not only alters the surface chemistry of the adsorbent but also provides important insights for defining reactivation strategies.

As a result of the homogenization tests, four measurements were obtained, with the moisture and phosphorus content values summarized in

Table 3. The pretreatment process (maceration and drying) yielded an initial SBE sample with phosphorus contents ranging from 0.62% to 0.66% P

2O

5, effectively reducing the variability observed in non-pretreated samples, where differences exceeded 1.0 ppm of phosphorus. Moisture values ranged from 3.19% to 3.21%, showing minimal variation and confirming the effectiveness of the homogenization step.

In addition, analyzing the moisture content further contributes to understanding these changes, as bentonite-based clays such as Sepigel are rich in montmorillonite, a layered mineral with remarkable swelling capacity due to water absorption within its interlayer spaces. This hydration increases the moisture content of the clay and alters its physical state, since bentonites are known for their ability to absorb both water and dissolved substances [

26,

27].

2.3. Enzymatic Hydrolysis on SBE

The hydrolytic activity of the enzyme was initially measured, yielding a result of 32,883 U/g of enzyme and a protein concentration of 12.3 mg/mL.

Figure 1 shows the phosphorus removal obtained in each experimental run. Because the hydrolysis assays were performed in random order, any differences in performance can be attributed solely to the variations in the treatments studied. The phosphorus removal values ranged from 83.7% to 89.7%, which are considered highly favorable for the proposed hydrolysis system.

Regarding the effect of reaction time, experiments conducted for 8 h (runs 9–12) consistently achieved higher removals (85.7–87.7%), particularly when combined with temperatures of 50 °C and enzyme loads of 200 mg. This result indicates that longer reaction times favor the hydrolysis releasing phosphorus compounds. The central points (runs 5–8; 50 °C, 100 mg, 6 h) also showed high removals, suggesting that this intermediate condition supports high enzymatic activity while maintaining enzyme stability.

Compared to conventional reactivation methods, the overall high removal percentages (>83%) confirm that the process is both efficient and competitive, despite being conducted under much milder operating conditions. Thermal reactivation methods for SBEs, for example, typically require temperatures above 500 °C to achieve a phosphorus removal of more than 95%, which is associated with huge energy consumption and can lead to structural deterioration of the clay [

9,

28]. Chemical or solvent-based methods have been shown to be less effective, achieving approximately 60% removal from oil [

9] while also requiring the use of expensive and potentially hazardous reagents that generate secondary waste streams [

29]. In contrast, this new enzymatic hydrolysis-based method works at low temperatures (40–60 °C) and uses only water and a biocatalyst, preserving the structural integrity of the clay.

2.3.1. Statistical Analysis of the First Experimental Design: Effect of Enzyme Load, Time and Temperature on Phosphorus Removal

Before performing the ANOVA, the assumptions of normality and homoscedasticity were verified to ensure the validity of the statistical analysis. The Shapiro–Wilk test confirmed that the residuals of the response variable, phosphorus removal, followed a normal distribution for both Experimental Design 1 and Experimental Design 2 (p = 0.8985 and p = 0.2225, respectively). The homogeneity of variances was confirmed through Levene’s test and residual plots, showing no significant deviations across factor levels (p > 0.05). Although the independent variables exhibited p-values below 0.05, this behavior is expected in factorial designs due to the use of discrete and controlled factor levels. Therefore, both statistical assumptions were satisfied, supporting the reliability of the ANOVA results.

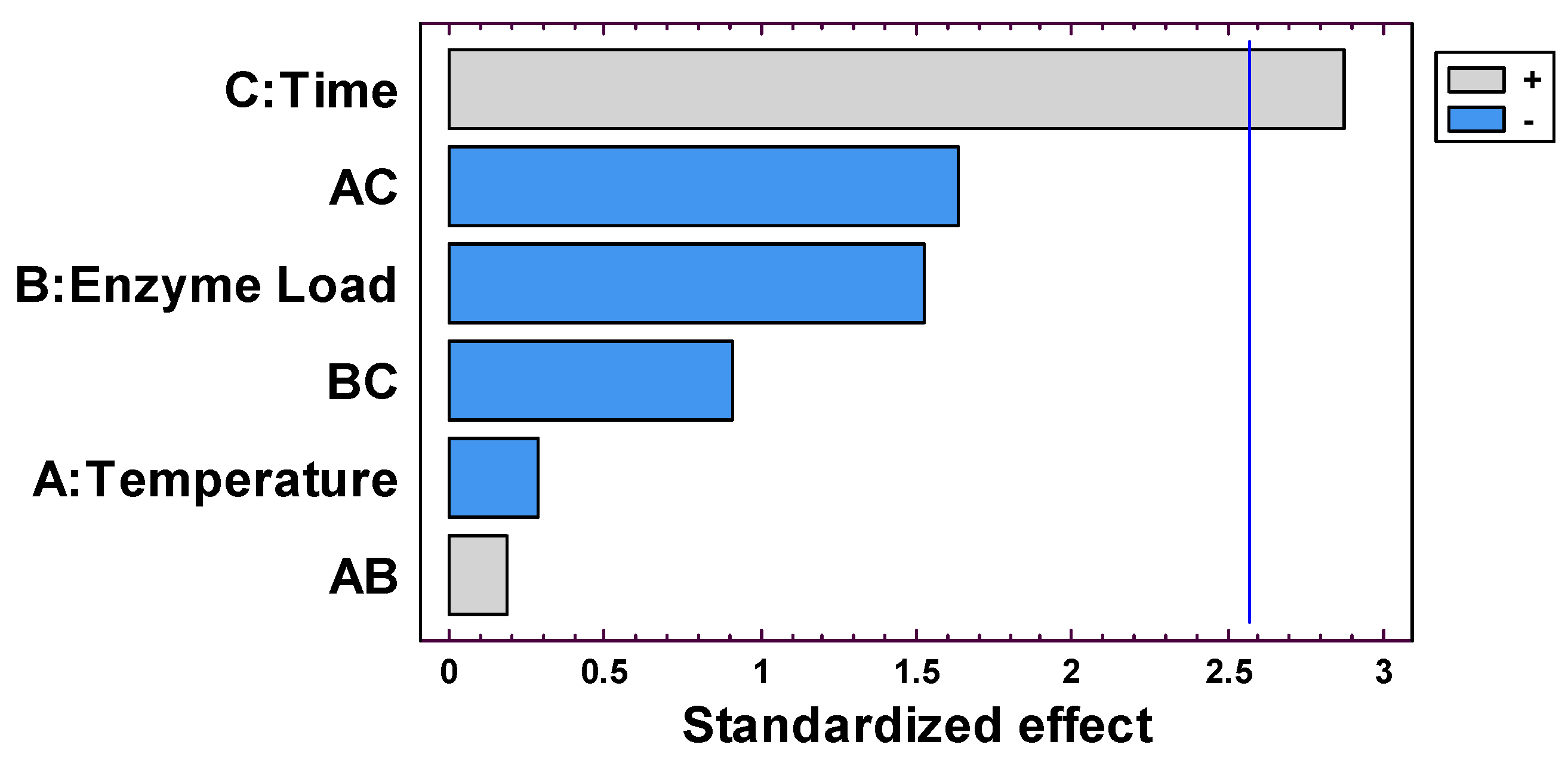

Figure 2 presents the standardized effects of the factors evaluated (temperature, enzyme load, and time) on phosphorus removal. Reaction time was the only factor with a statistically significant positive effect (

p < 0.05), indicating that longer hydrolysis times enhanced phosphorus removal. Temperature showed a very limited influence, suggesting that operating at lower temperatures was sufficient to achieve satisfactory results. Interestingly, enzyme load exerted a negative effect, meaning that higher enzyme concentrations did not translate into higher phosphorus removal, which may be related to the saturation effects.

Regarding interaction effects, both time–temperature (AC) and enzyme load–time (BC) interactions showed negative contributions to phosphorus removal, although neither was statistically significant. The temperature–enzyme load interaction (AB) was positive but very small, confirming its negligible influence on the response. Overall, this result indicates that the process was mainly driven by reaction time, while interactions between factors played only minor roles in the system.

The ANOVA results (

Table 4) indicated that reaction time was the only statistically significant factor affecting phosphorus removal (

p = 0.0351), while temperature and enzyme load had no significant effects (

p > 0.05). Time accounted for the largest proportion of the explained variability, confirming its role as the main determinant of hydrolysis efficiency. In contrast, the negligible influence of temperature within the studied range (40–60 °C) suggests that operating at lower temperatures is sufficient, whereas enzyme load showed a non-significant negative trend, possibly related to saturation phenomena at higher dosages.

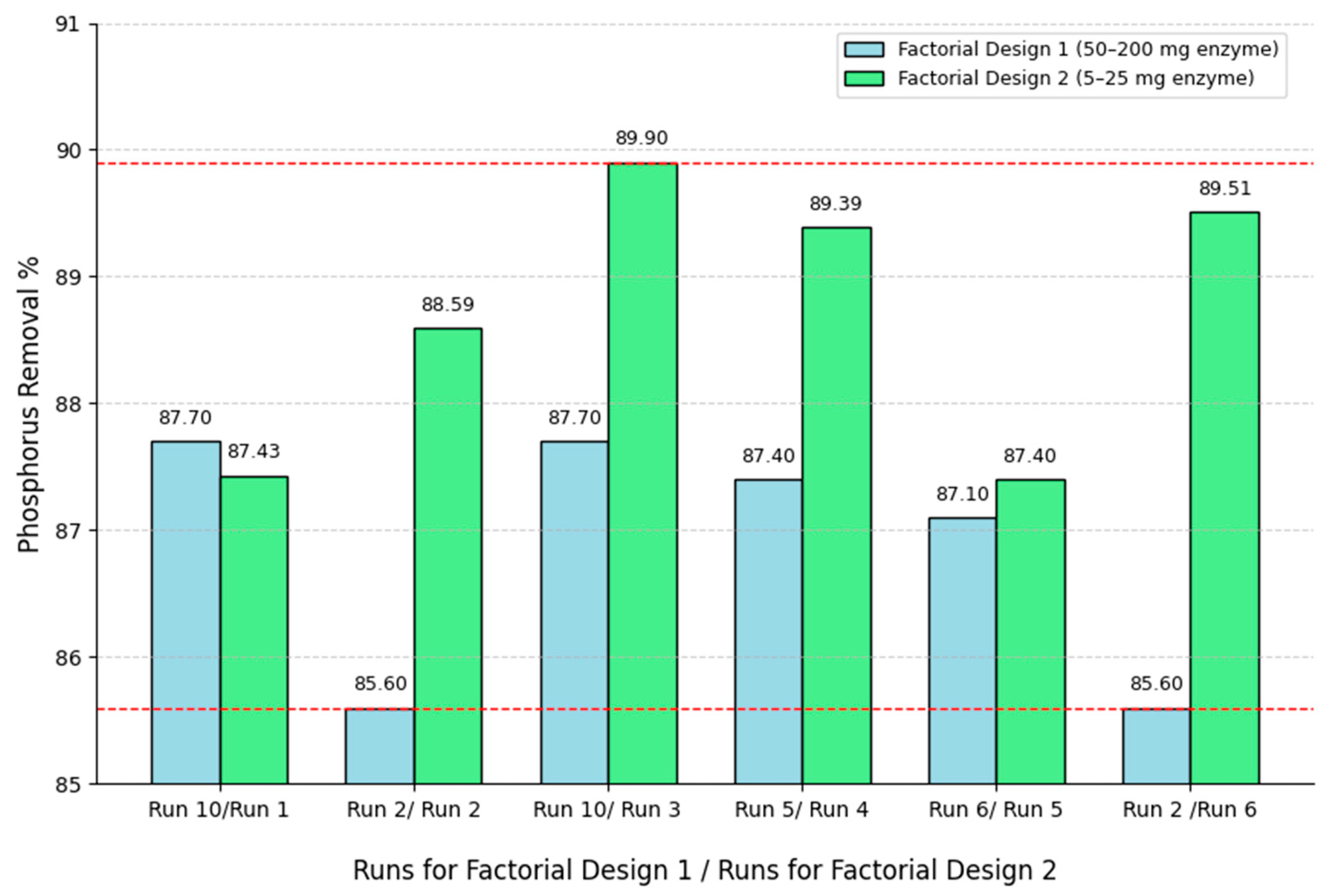

Based on these findings, a second experimental design was conducted by drastically reducing the enzyme load to 5–25 mg while fixing the temperature at 60 °C and varying time. Remarkably, the results confirmed that the phosphorus removal efficiencies remained consistently high (87.4–89.9%), comparable to those obtained in the initial factorial design with much higher enzyme concentrations (see

Figure 3).

Figure 4 compares the phosphorus removal efficiencies obtained in Design 2 (enzyme load: 5–25 mg) with those from Design 1 (50–200 mg), maintaining the same temperature and time conditions, except for runs 4 and 5, which were compared with the central points of the first design. The results demonstrate that despite the significant reduction in enzyme dosage, removal efficiencies remained within a similar range (87–90%), and in some cases, even outperformed those obtained in the first design. This finding confirms the robustness of the system and validates the relevance of conducting a second experimental design. In addition, it demonstrates that the enzymatic hydrolysis of SBEs can be achieved with minimal enzyme usage, substantially improving the economic feasibility of the process without compromising performance.

2.3.2. Statistical Analysis of the Second Experimental Design: Effect of Reduced Enzyme Load on Phosphorus Removal

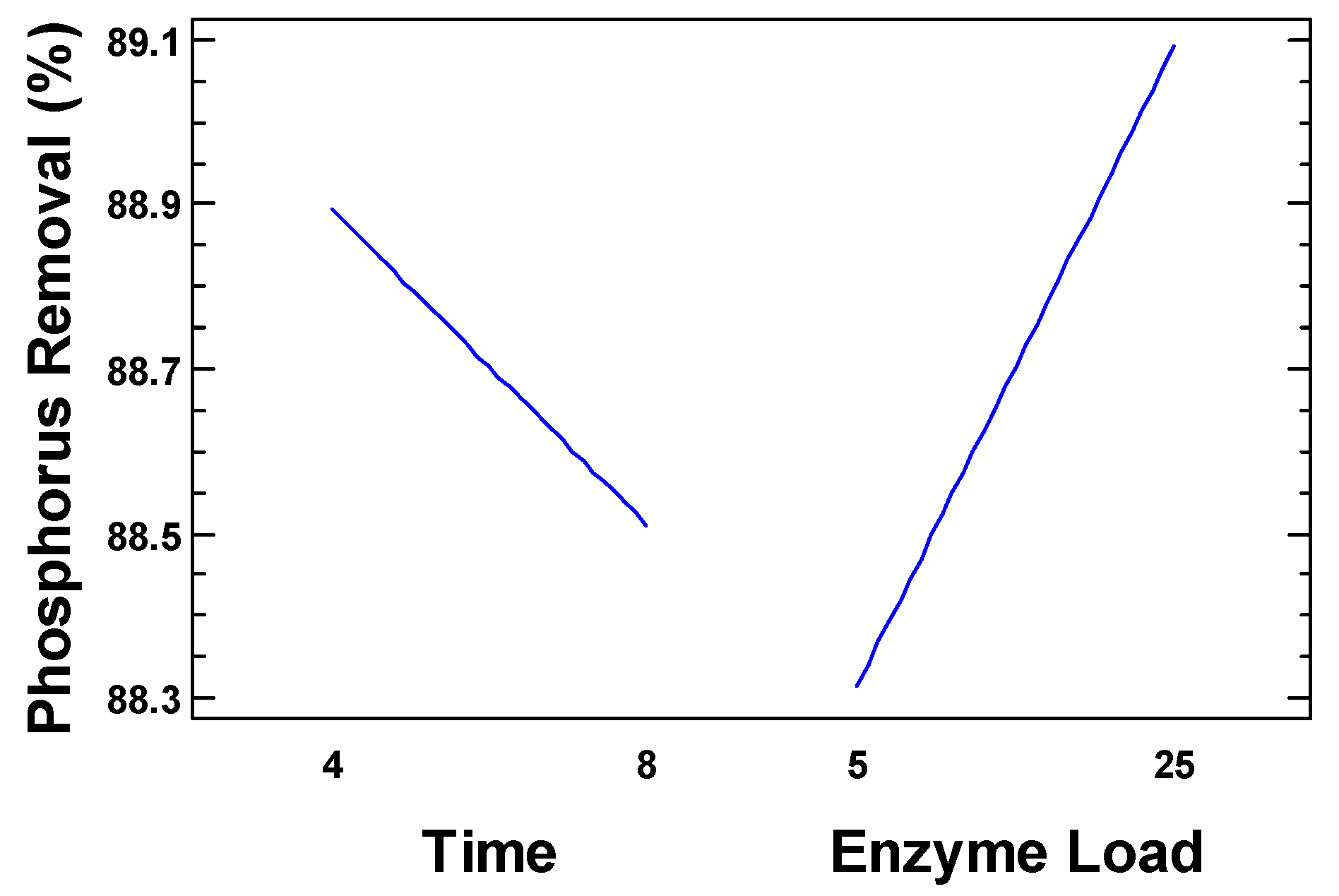

The main effects analysis for phosphorus removal in the second experimental design, shown in

Figure 5, indicate that although none of the factors reached statistical significance (

p > 0.05), enzyme load at low concentrations exhibited a positive effect on phosphorus removal from the initial SBE. This outcome suggests that within the reduced range of enzyme dosage (5–25 mg), the system still benefits from an increase in enzyme load, in contrast to the trend observed in the first design at higher concentrations.

Therefore, such behavior indicates that at very low levels, the enzyme may become limiting, and a slight increase in dosage enhances hydrolytic activity. Phosphorus removal values remained within a narrow range (88.3–89.1%) across all treatments, indicating that under the conditions tested, the system maintained high efficiency regardless of the specific factor levels applied.

The opposite trends observed for enzyme load between Experimental Designs 1 and 2 can be explained by mass transfer and diffusional effects inherent to heterogeneous enzymatic systems. At higher enzyme concentrations, the hydrolysis rate increases, leading to a greater release of free fatty acids into the aqueous medium. The accumulation of these products can raise the viscosity of the reaction mixture, which in turn restricts substrate diffusion toward the active sites of the enzyme. Moreover, excessive enzyme concentrations may promote local crowding of catalytic molecules, limiting substrate accessibility and generating apparent saturation effects. Conversely, at lower enzyme loads, the catalytic sites are more evenly dispersed throughout the medium, reducing diffusional resistance, and allowing more effective enzyme–substrate interactions.

2.3.3. Absence and Presence of the Response Variable

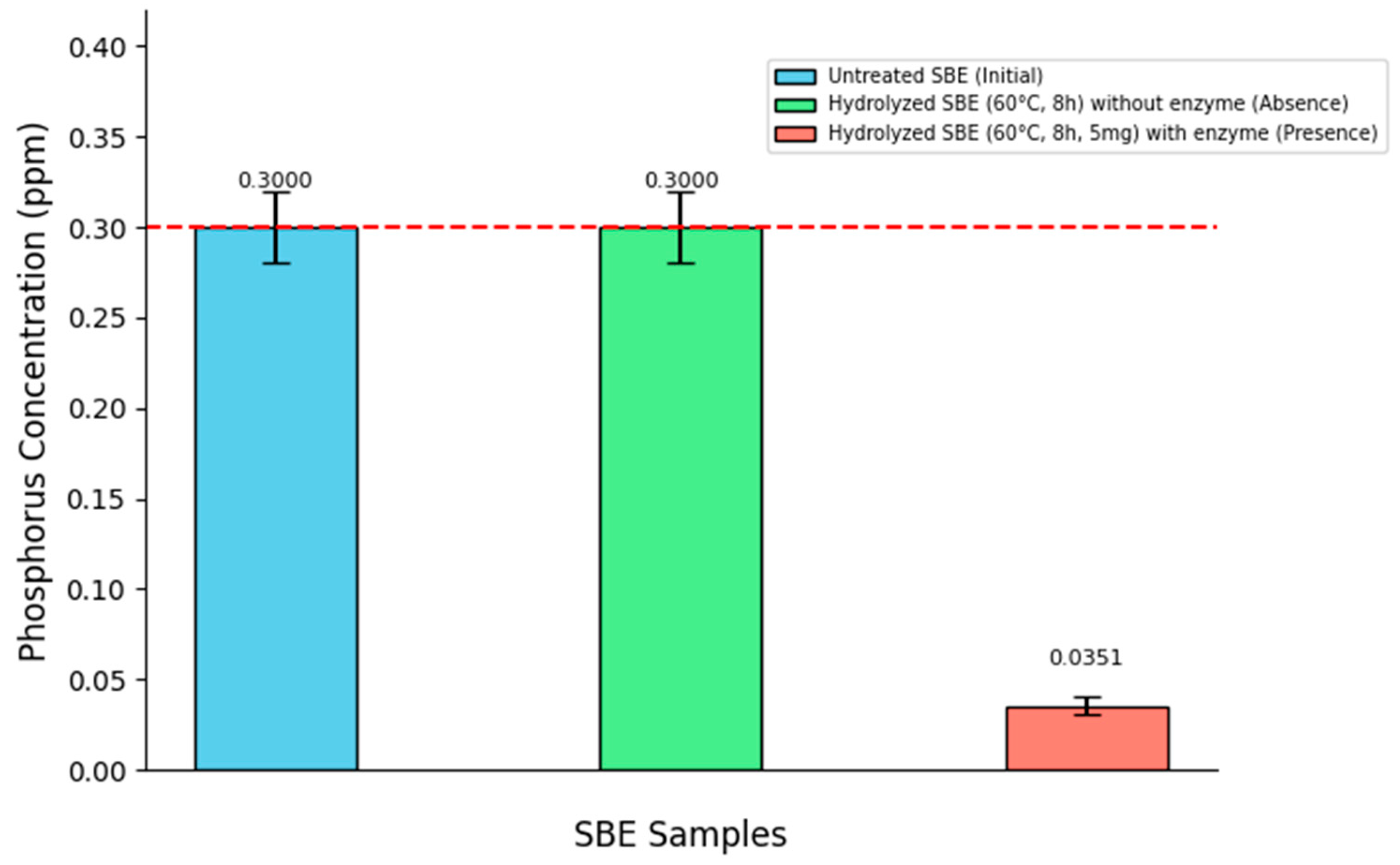

As an alternative analysis, a hydrolysis test was conducted in the complete absence of enzyme load, while maintaining a reaction time of 8 h and a temperature of 60 °C. This control confirmed that under enzyme-free conditions, the SBE showed no phosphorus removal. The results of this test are presented in

Figure 6.

Although enzyme load did not reach statistical significance in the previous factorial analysis (p = 0.1815), the observed trend suggests that enzyme dosage still plays an explanatory role in the process. This result becomes particularly relevant since the dichotomous comparison (absence vs. presence) showed no differences, whereas the factorial approach—by systematically varying enzyme load and reaction time—was able to capture subtle effects that would otherwise remain unnoticed.

Therefore, the statistical evaluation supports the conclusion that reaction time is the most determinant variable, while enzyme load—although not statistically significant in the first design—became relevant at low concentrations in the second design, showing a positive effect on phosphorus removal. This behavior highlights that enzyme dosage cannot be disregarded, as its influence emerges particularly under reduced conditions. Both factors are thus essential for a proper understanding and optimization of the enzymatic hydrolysis system.

Finally, the scope of this research culminated in the identification of the operational conditions that provide the best cost–benefit balance, as summarized in

Table 5.

2.4. Evaluation of Phosphorus Removal Efficiency in Soybean Oil Treated with Reactivated Bleaching Earth

The analysis of phosphorus in chemically refined soybean oil showed concentrations of 14.29 ppm before bleaching and 0.53 ppm after treatment with untreated (virgin) bleaching earth. The difference between these values corresponds to an ideal removal of 13.76 ppm.

Subsequently, the phosphorus concentration in the oil treated with reactivated bleaching earth was determined using the same procedure. Two measurements were performed, yielding an average concentration of 0.8465 ppm, equivalent to a reactivation efficiency of 97.67% for phosphorus (Equation (2)). This result highlights the high effectiveness of the reactivation process for this parameter.

This result highlights the high effectiveness of the reactivation process for this parameter, which is particularly important when compared to conventional reactivation methods such as thermal or chemical treatments that often require harsher operating conditions to achieve a similar level of phosphorus removal.

2.5. Evaluation of Color Reduction in Soybean Oil Treated with Reactivated Bleaching Earth

Table 6 summarizes the color units obtained for each treatment: neutral soybean oil, soybean oil bleached with virgin earth, and soybean oil bleached with reactivated earth. The difference between oils treated with virgin and reactivated earth was approximately 1.7 red units, indicating a lower removal of pigments such as chlorophylls and carotenoids for reactivated bleaching earth. Considering an expected removal of 2.6 units, the percentage of reactivation reached was 34%, substantially lower than that observed for the phosphorus variable.

This limited performance may be associated with the reduced activity of acidic sites in Sepigel Active clay after reactivation. This clay is particularly used in soybean oil bleaching due to its affinity for pigments such as chlorophyll, which is a primary precursor of dark coloration in the oil [

27]. However, during enzymatic hydrolysis, residual hydrochloric acid present in the reactivated matrix may react with water, generating hydronium and chloride ions that could partially deactivate the acidic sites responsible for pigment adsorption.

The FTIR analysis revealed that the Si–O stretching region (~1000–1100 cm−1) remained comparable between the virgin and hydrolyzed samples, indicating no significant disruption of the clay mineral lattice. The spent SBE spectrum displayed stronger absorption in the organic fingerprint region (~1700–1300 cm−1), consistent with adsorbed oils and phospholipids. In contrast, the hydrolyzed SBE showed a marked reduction in these organic-related bands, confirming the partial removal of residual lipids and fatty materials through enzymatic hydrolysis. However, since phosphate (P–O) vibrations overlap with Si–O stretching signals, FTIR alone cannot accurately quantify alterations in phosphate binding sites. These findings and their implications were further discussed in the revised manuscript. Moreover, the persistence of structural integrity alongside the partial loss of surface acidity likely explains the limited color removal efficiency (34%), suggesting that mild acid reactivation could help restore the pigment adsorption capacity of the regenerated clay.

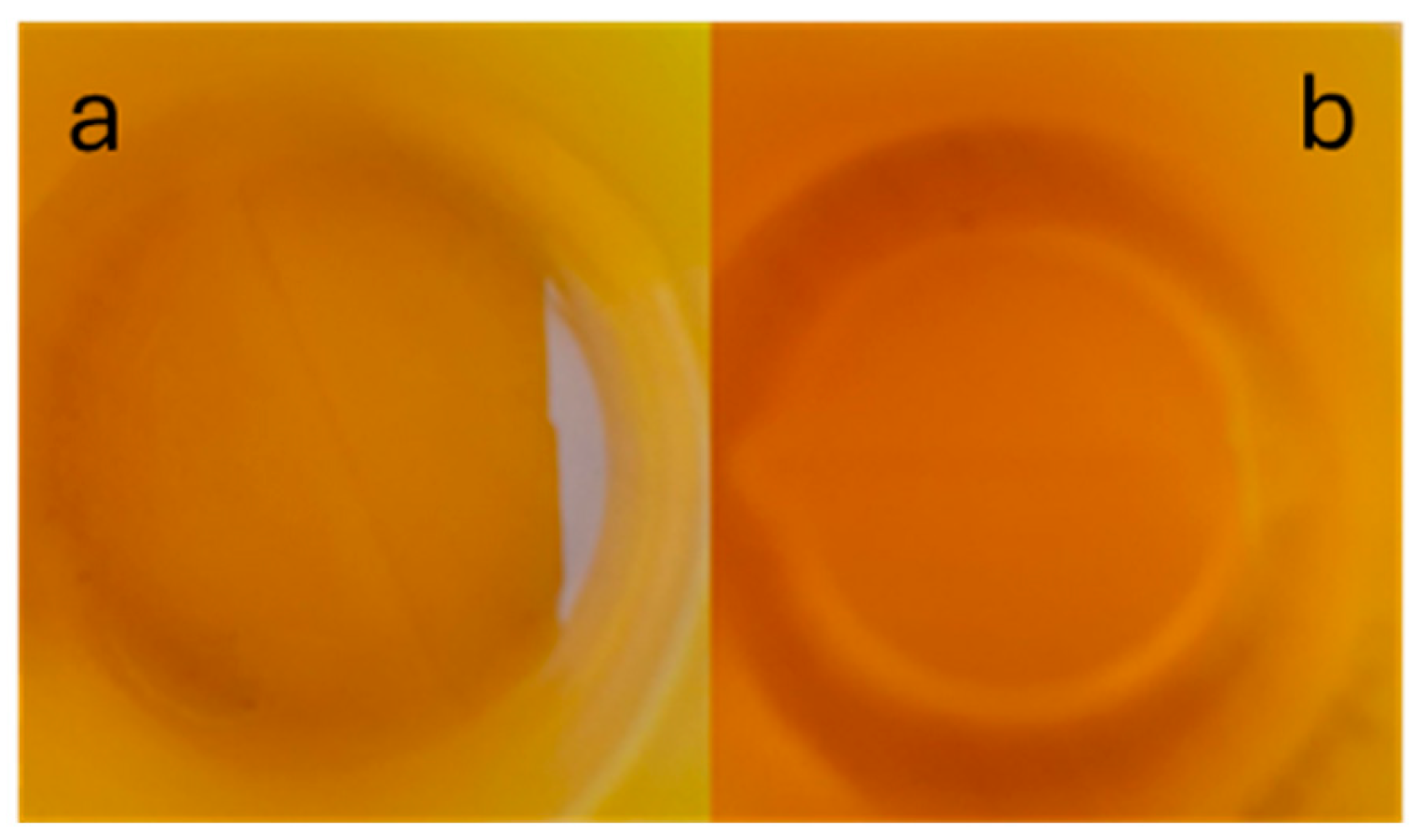

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 illustrate the physical changes observed in the earth and oils. The reactivated earth did not exhibit significant changes in appearance compared to the spent material, as residual oil remained in its pores; however, this did not prevent efficient phosphorus capture. In contrast, the oil treated with reactivated earth exhibited a brighter and less saturated color.

To complement this visual comparison, quantitative color measurements were performed using a Lovibond

® Tintometer (Model PFX i Series, Wiltshire, UK) with a 5.25-inch glass cell, following the official AOCS Cc 13b-45 method (Lovibond scale) [

30]. The decolorized oil obtained with regenerated bleaching earth (sample A) showed Lovibond indices of Red 7.9, Yellow 70.0, Blue 0.0, and Neutral 0.9, while the neutral soybean oil reference (sample B) presented values of Red 5.2, Yellow 70.0, Blue 0.0, and Neutral 0.9.

It is important to note that the bleaching stage represents an intermediate step in the physical refining of vegetable oils, for which no international standard specifies fixed color limits. In industrial practice, refineries typically use internal control criteria to verify bleaching efficiency prior to deodorization. For soybean oil, red color values below 7.0 Lovibond units (5.25-inch cell) are generally acceptable to ensure that the refined (RBD) oil achieves a final color ≤ 2.0 red units. Although the oil bleached with regenerated earth exhibited a slightly higher value (7.9 red units), this result is considered satisfactory given that 100% regenerated material was used.

2.6. Analysis of Chemical Elements in Liquid Hydrolysate

The liquid hydrolysate was analyzed using inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES). The results, listed in

Table 7, showed the presence of several elements with potential fertilizing value. The analysis detected the presence of key nutrients: phosphorus (750 µg/L), an essential nutrient for root and flower development; potassium (690 µg/L), which plays a key role in photosynthesis, water regulation, and resistance to plant diseases; and magnesium (16 mg/L), a central component of chlorophyll and therefore essential for photosynthesis [

31,

32]. Consequently, the nutrient-rich hydrolysate could be used as a cost-effective biofertilizer, which is consistent with reported strategies for phosphorus recovery from waste streams [

33].

In addition, sulfur (980 µg/L), which supports protein synthesis in plants, especially in high-yielding crops, and calcium (1.7 mg/L), which helps to strengthen plant cell walls and improve soil quality, were identified. The liquid hydrolysate also contained iron (3.1 mg/L) and manganese (57 µg/L) in amounts that do not pose a risk and could even be beneficial in soils deficient in these elements [

31].

Overall, the results indicate that liquid resulting from hydrolysis has an interesting profile as a complementary liquid fertilizer, mainly due to its content of phosphorus, potassium, magnesium, and sulfur. Nevertheless, controlled pilot-scale trials are recommended prior to large-scale application to assess its effects on plants and interactions with soil.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

Crude soybean oil, bleached oil, refined-bleached deodorized oil (RBD), SBE, and untreated bleaching earth were supplied by a food refinery in Barranquilla, Colombia. The commercial lipase from Candida rugosa (LIPASE 20) was donated by the company Merquiand (Itagüí, Colombia). All reagents used in this study were of analytical grade.

3.2. Oil Characterization

The oil samples were analyzed for the following parameters: moisture content, color, peroxide value (meq O

2/kg), phosphorus content (ppm), Lovibond color (yellow/red), fat content (% dry weight), and acidity. These determinations were carried out according to the official procedures laid down in the ICONTEC NTC and AOCS standards, as summarized in

Table 8.

3.3. Determination of the Phosphorus Content in Spent Bleaching Earth

The determination of total phosphorus in the samples was carried out according to the Colombian technical standard NTC 6259:2018 (Calidad del suelo—Determinación de fósforo total) [

41] and the official AOCS method Ca 12-55 (Phosphorus) [

33]. For this purpose, 3 g of SBE was mixed with 0.5 g of zinc oxide and calcined for 2 h. The residue was digested with 5 mL of concentrated hydrochloric acid and 5 mL of distilled water and then heated for 10 min. The resulting solution was transferred to a 100 mL volumetric flask, diluted to volume with distilled water, homogenized, and filtered through No. 1 filter paper. An aliquot of 5 mL of the filtrate was added to a 100 mL volumetric flask to which 1 mL of citric acid, 5 mL of metol sulfite solution, and 5 mL of ammonium molybdate solution were successively added, mixing after each addition. After a standing time of 20 min, 10 mL of buffer solution was added, and the volume was made up with distilled water. In parallel, a reagent blank was prepared, and the absorbance was measured at 640 nm.

3.4. Homogenization of Spent Bleaching Earth

The bleaching of crude or chemically refined oils produces a by-product commonly referred to as “oil loss in spent clay”. This loss is not uniform throughout the bleaching phase as it depends on the dosage of bleaching clay and the saturation capacity of the clay. As a result, the SBE obtained for the analysis may have a heterogeneity that can affect the reliability of the response variables. To minimize this variability and ensure consistent phosphorus determination across different samples of the same matrix, a homogenization procedure was introduced. Samples were first dried at 45 °C for 72 h and then ground to a particle size of 0.5 mm using a 911PESTLX ring grinder (911Metallurgist, Langley, BC Canada) designed for mineral samples. When hydrolysis treatment was required, the material was additionally dried at 45 °C for 24 h.

3.5. Determination of Lipase Hydrolytic Activity

The hydrolytic activity of the enzyme was initially measured, yielding 252 U/g of enzyme with a protein concentration of 12.3 mg/mL. The activity was determined at 40 °C through the hydrolysis of olive oil (emulsified with gum Arabic) in phosphate buffer at pH 8 for 10 min of reaction, using 25 mg of enzyme in 8 mL of buffer and 10 mL of emulsion. The reaction was stopped by adding 15 mL of an acetone/ethanol mixture (1:1, v/v), and the hydrolytic activity was determined by titration of the released free fatty acids using 50 mM KOH solution with phenolphthalein as an indicator. A blank control containing the same reaction medium as the assays was maintained under identical conditions but received only 1 mL of buffer instead of enzymatic solution before the addition of the acetone/ethanol mixture. The control was titrated in the same way as the enzymatic assays to determine the initial acidity of the substrate. One unit of activity was defined as the amount of enzyme required to release 1 µM of fatty acid per minute under the assay conditions.

3.6. Enzymatic Hydrolysis

For the hydrolysis experiment, approximately 8 g of previously dried, macerated, and pulverized spent bleaching earth was weighed and mixed with 160 mL of distilled water in a 250 mL beaker. The beaker was covered with aluminum foil and placed on a resistance heating plate connected to a thermocouple that allowed for precise control of the temperature and heating time. The reaction temperature was maintained with a deviation of ±0.5 °C (

Supplementary Material Figure S2). Enzymatic hydrolysis was carried out using commercial lipase (Lipase 20,

Candida rugosa), with enzyme loads ranging from 5 to 200 mg, reaction temperatures between 40 and 60 °C, and reaction times from 4 to 8 h, according to the conditions established in the two factorial experimental designs. The suspension was continuously stirred with a magnetic stirrer at 300 rpm to disperse the solids. Once hydrolysis was complete, the mixture was filtered through class 1 filter paper, and the solid fraction was transferred to a convection oven at 103 °C for 1 h for complete drying.

3.6.1. Bleaching of Crude Soybean Oil

The bleaching of crude soybean oil was carried out under conditions designed to simulate the industrial process, following the parameters summarized in

Table 9. The procedure consisted of two steps: the addition of citric acid at low temperature, followed by the addition of activated clay or silica under moderate heating conditions to promote the adsorption of impurities.

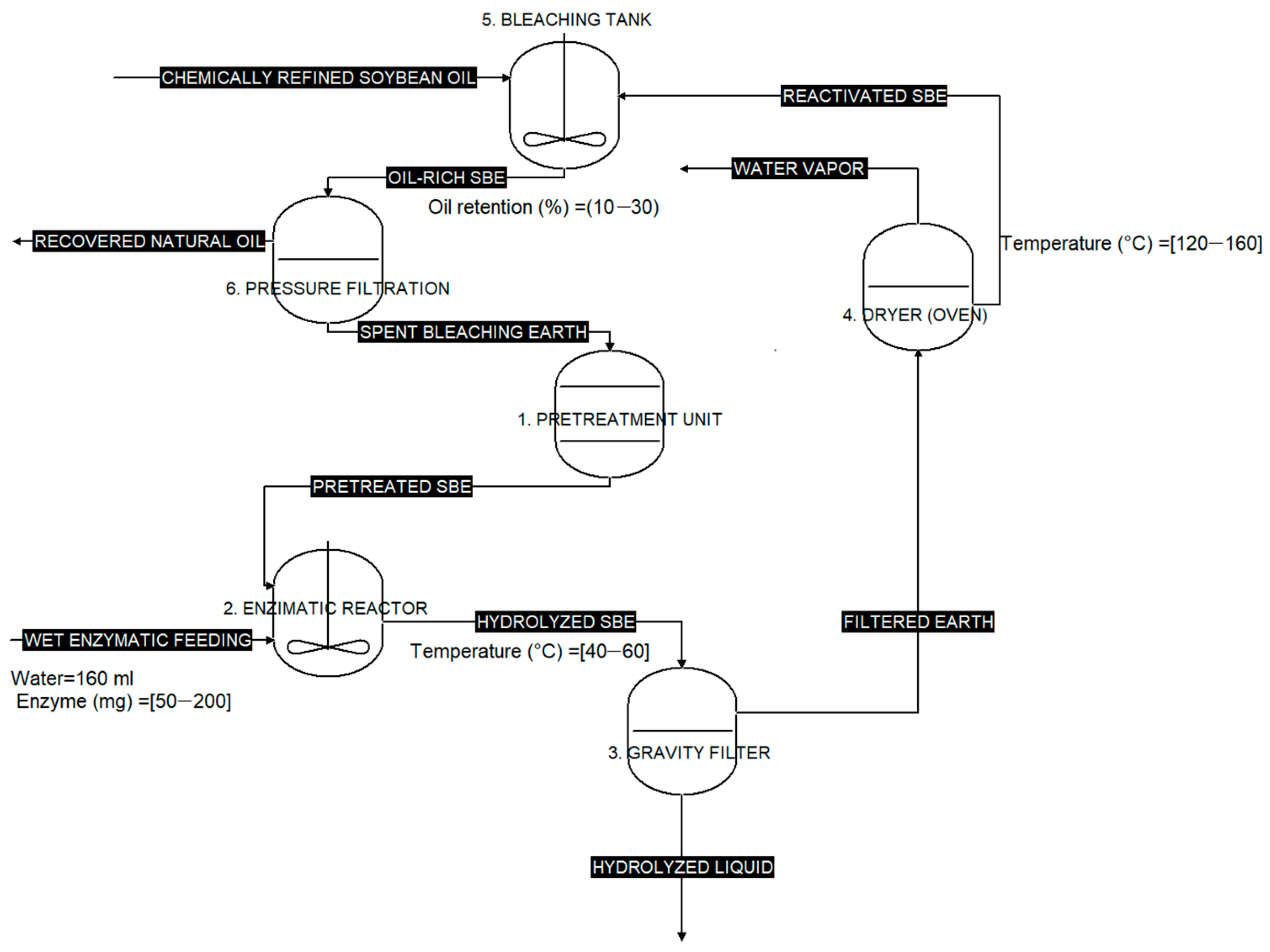

3.6.2. Spent Bleaching Earth Reactivation Cycle

Figure 9 illustrates the reactivation cycle of the SBE. The process started with the pre-treatment unit (1), where the SBE was homogenized to obtain a particle size of 50–90 µm and a moisture content of 0.1–0.2%. The pretreated SBE (a) was then fed into the enzymatic reactor (2), which had two inlets (water with enzyme-load and pretreated SBE) and one outlet, resulting in an aqueous suspension of hydrolyzed SBE (b). This suspension was passed into the gravity filter (3), resulting in a hydrolyzed liquid (c) that was collected for storage, and a solid phase, referred to as filtered SBE (d). The solid phase was subsequently fed into the dryer (4) to reduce its moisture content. The dried material, referred to as reactivated SBE (e), was then fed into the bleaching tank (5) together with chemically refined soybean oil (f). The cycle was completed by drying the oil-rich SBE obtained after bleaching and returning it to the pre-treatment unit (1).

3.6.3. Experimental Designs

An initial 2

3 factorial experimental design with four central points was implemented (

Table 10), resulting in a total of 12 runs. The design evaluated the effects of three factors at two levels: temperature (40 and 60 °C), enzyme load (50 and 200 mg), and reaction time (4 and 8 h). For the central points, the experiments were conducted at 50 °C, with an enzyme load of 100 mg, and a reaction time of 6 h. The response variable was defined as the phosphorus concentration in the solid phase at the reactor outlet, since this matrix represented the main object of study. Although both solid and liquid phases were generated, only the solid phase was analyzed. ANOVA was obtained using the Design of Experiments (DOE) module of STATGRAPHICS 19

® (Washington, DC, USA), focusing on single-response analysis with representativity plots and interaction plots among the factors.

A second factorial experimental design evaluating low enzymatic load (5–25 mg) in times of 4, 6, and 8 h was implemented, as shown in

Table 11.

3.6.4. Calculation of Efficiencies and Percentages of Removal

Equation (1) was applied to determine the amount of phosphorus removed from the earth before and after enzymatic hydrolysis:

where

P corresponds to the phosphorus concentration, and the subscripts

and

denote the initial and final states, respectively.

The bleaching efficiency of the process was evaluated through two parameters (phosphorous or color) according to the following equations:

where %

Reactivation is the percentage of reactivation of parameter

i;

parameterSBO,i is the value of parameter

i in soybean oil (SO);

parametersample,i is the value obtained for the same parameter in the evaluated sample; and

is the removal obtained when bleaching with untreated earth.