CoRu Alloy/Ru Nanoparticles: A Synergistic Catalyst for Efficient pH-Universal Hydrogen Evolution

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

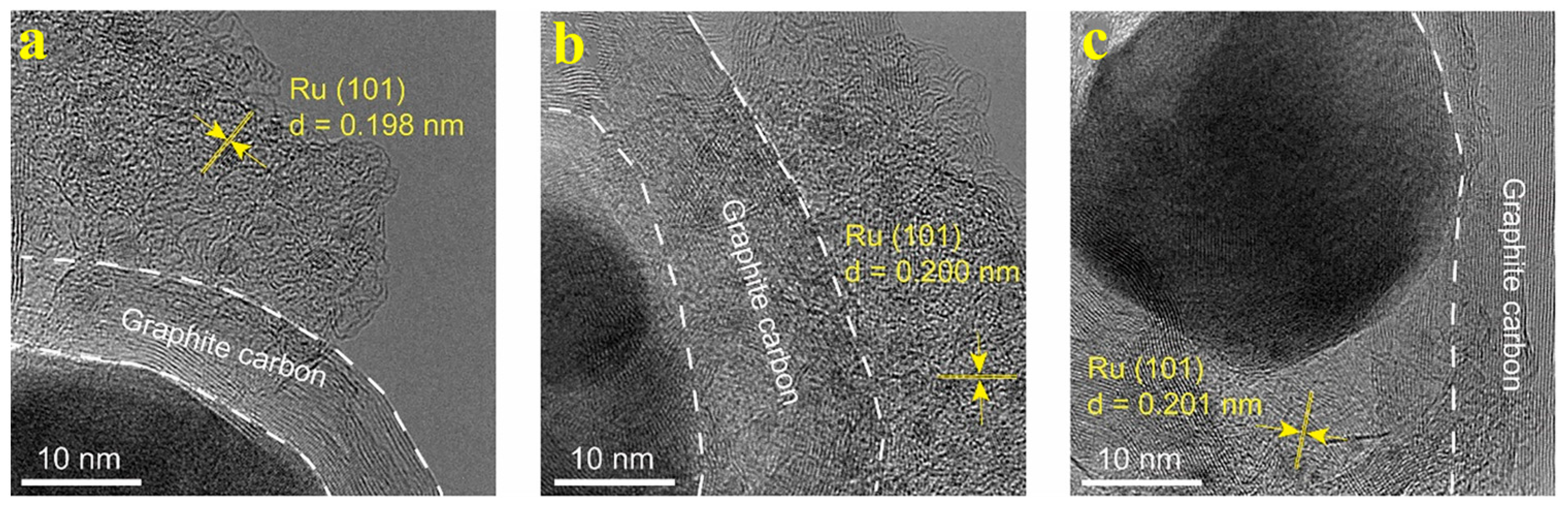

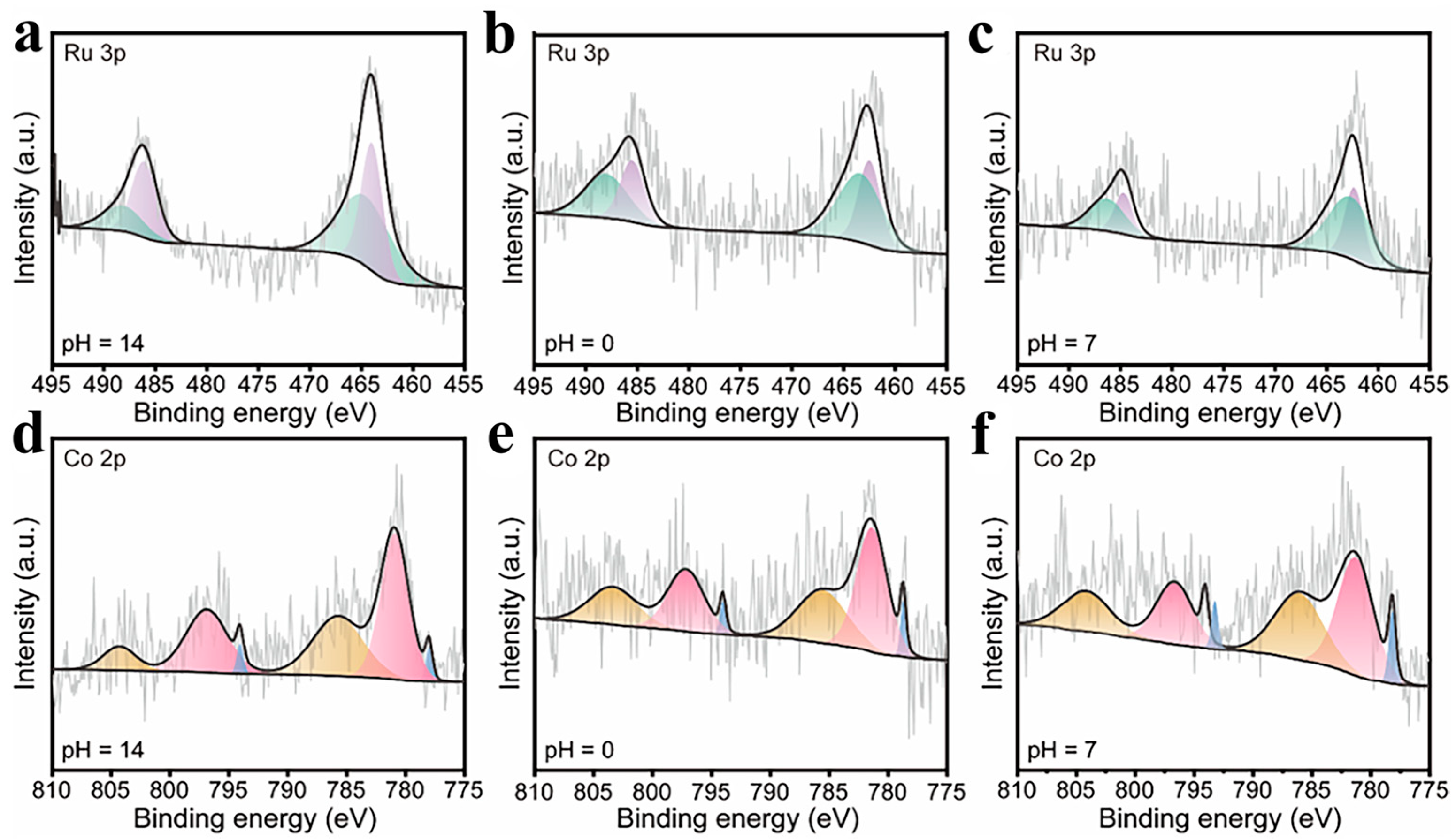

2.1. The Structure and Composition of CoRu/CNB Electrocatalysts

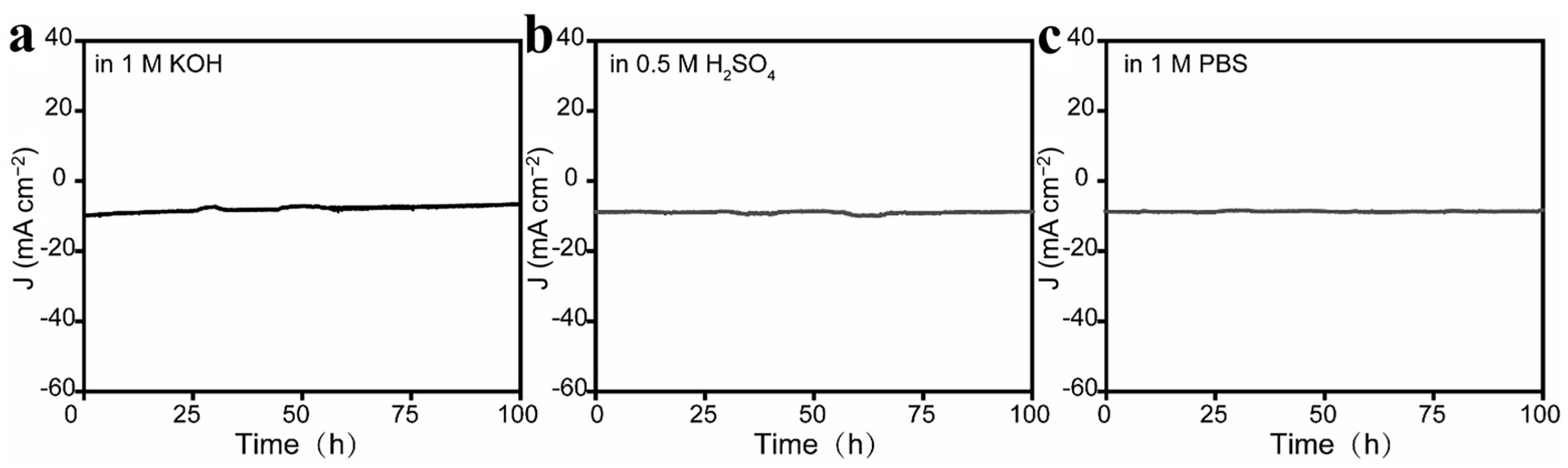

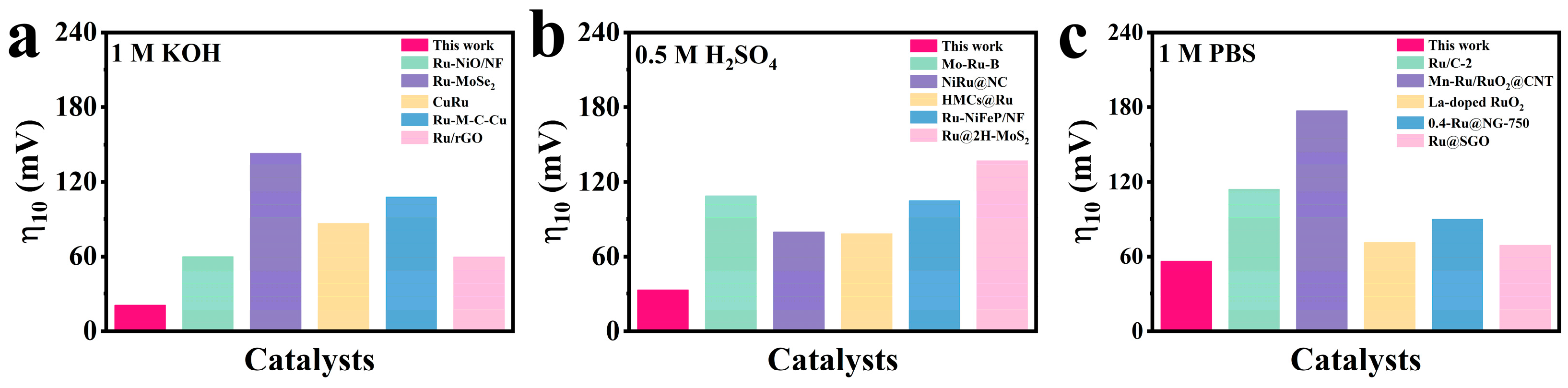

2.2. Electrocatalytic Performance of CoRu/CNB

3. Materials and Methods

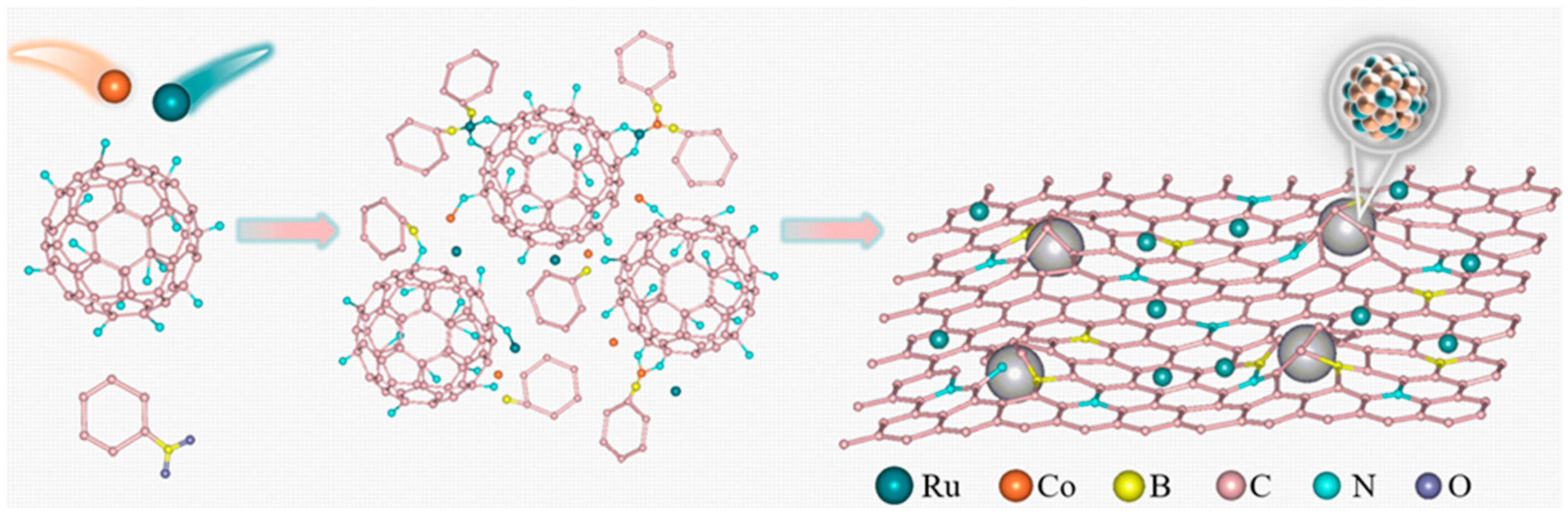

3.1. Preparation of C60-EDA Precursors

3.2. Preparation of CoRu/CNB Electrocatalysts

3.3. Characterization

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Malaiyarasan, V.; Umamageshwari, R.; Sunil Kumar, M.; Beem Kumar, N.; Subbiah, G.; Priya, K.K. Advances in electrocatalyst development for hydrogen production by water electrolysis. Rev. Inorg. Chem. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pashaei, B.; Aghaei, A.; Ghaderian, A.; Fardood, S.T. Abundant transition metal sulfides as promising class of materials for electrochemical hydrogen evolution: Design and synthesis strategies. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1035, 181395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, F. How renewable energy and non-renewable energy affect environmental excellence in N-11 economies? Renew. Energy 2022, 196, 526–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.H.; Ko, Y.-J.; Kim, J.H.; Choi, C.H.; Chae, K.H.; Kim, H.; Hwang, Y.J.; Min, B.K.; Strasser, P.; Oh, H.-S. High crystallinity design of Ir-based catalysts drives catalytic reversibility for water electrolysis and fuel cells. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhou, D.; Deng, T.; He, G.; Chen, A.; Sun, X.; Yang, Y.; Miao, P. Research Progress of Oxygen Evolution Reaction Catalysts for Electrochemical Water Splitting. ChemSusChem 2021, 14, 5359–5383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizan, M.T.; Aqsha, A.; Ameen, M.; Syuhada, A.; Klaus, H.; Abidin, S.Z.; Sher, F. Catalytic reforming of oxygenated hydrocarbons for the hydrogen production: An outlook. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2023, 13, 8441–8464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amini Horri, B.; Ozcan, H. Green hydrogen production by water electrolysis: Current status and challenges. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2024, 47, 100932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molaei, M.J. Recent advances in hydrogen production through photocatalytic water splitting: A review. Fuel 2024, 365, 131159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, L.; He, T.; Xiang, Y.; Guan, Y. Study on the reaction pathways of steam methane reforming for H2 production. Energy 2020, 207, 118296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Gao, Y.; Li, Y.; Weragoda, D.M.; Tian, G.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, X.; Chen, B. Research progress on MOFs and their derivatives as promising and efficient electrode materials for electrocatalytic hydrogen production from water. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 24393–24411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Qi, F.; Ren, R.; Gu, Y.; Gao, J.; Liang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, H.; Kong, X.; Zhang, Q.; et al. Recent Advances in Green Hydrogen Production by Electrolyzing Water with Anion-Exchange Membrane. Research 2025, 8, 0677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Lu, A.; Zhong, C.-J. Hydrogen production from water electrolysis: Role of catalysts. Nano Converg. 2021, 8, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.Y.; Duan, Y.; Feng, X.Y.; Yu, X.; Gao, M.R.; Yu, S.H. Clean and Affordable Hydrogen Fuel from Alkaline Water Splitting: Past, Recent Progress, and Future Prospects. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2007100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Jang, H.; Liu, S.; Li, Z.; Kim, M.G.; Li, C.; Qin, Q.; Liu, X.; Cho, J. The Heterostructure of Ru2P/WO3/NPC Synergistically Promotes H2O Dissociation for Improved Hydrogen Evolution. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 60, 4110–4116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wang, D.; Lu, Q.; Meng, T.; Yan, M.; Fan, L.; Xing, Z.; Yang, X. Identifying the Activation Mechanism and Boosting Electrocatalytic Activity of Layered Perovskite Ruthenate. Small 2020, 16, 1906380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lu, Q.; Li, F.; Guan, D.; Bu, Y. Atomic-Scale Configuration Enables Fast Hydrogen Migration for Electrocatalysis of Acidic Hydrogen Evolution. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2213523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.-B.; Sherpa, K.; Chen, C.-W.; Chen, L.; Dong, C.-D. Breakthroughs and prospects in ruthenium-based electrocatalyst for hydrogen evolution reaction. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 968, 172020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, M.; Du, X.; Hou, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Ji, H.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Yi, S.; Chen, D. In-Situ growth of ruthenium-based nanostructure on carbon cloth for superior electrocatalytic activity towards HER and OER. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2022, 317, 121729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.-R.; Jiang, X.; Sun, T.; Wang, X.; Li, B.; Wu, Z.; Liu, H.; Wang, L. Ru branched nanostructure on porous carbon nanosheet for superior hydrogen evolution over a wide pH range. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 947, 169393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Cai, L.; Tu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, W. Emerging ruthenium single-atom catalysts for the electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution reaction. J. Mater. Chem. A 2022, 10, 15370–15389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Hu, Y.; Fu, Y.; Yang, J.; Song, D.; Li, B.; Xu, W.; Wang, N. Single Ru Sites on Covalent Organic Framework-Coated Carbon Nanotubes for Highly Efficient Electrocatalytic Hydrogen Evolution. Small 2023, 20, 2305978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yang, X.; Pei, G.; Yang, J.; Liu, J.; Zhao, F.; Jin, F.; Jiang, W.; Ben, H.; Zhang, L. Strong metal–support interaction boosts the electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution capability of Ru nanoparticles supported on titanium nitride. Carbon Energy 2023, 6, e391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.-F.; Xiao, H.; Jing, Y.-Y.; Gao, Y.; He, Y.-L.; Zhao, M.; Jia, J.-F.; Wu, H.-S. Site difference influence of anchored Ru in mesoporous carbon on electrocatalytic performance toward pH-universal hydrogen evolution reaction. Rare Met. 2023, 42, 4015–4028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, T.; Huang, J.; Hu, Y.; Yuan, C.; Chen, J.; Cao, L.; Kajiyoshi, K.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Li, Z.; et al. Fullerene Lattice-Confined Ru Nanoparticles and Single Atoms Synergistically Boost Electrocatalytic Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2213058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Mukoyoshi, M.; Kusada, K.; Yamamoto, T.; Toriyama, T.; Murakami, Y.; Ina, T.; Kawaguchi, S.; Kubota, Y.; Kitagawa, H. RuIn Solid-Solution Alloy Nanoparticles with Enhanced Hydrogen Evolution Reaction Activity. ACS Mater. Lett. 2024, 6, 353–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Tang, L.; Wang, P.; He, M.; Yang, C.; Li, Z. Rare Earth-Based Alloy Nanostructure for Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. ACS Catal. 2023, 13, 13804–13815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huihui, Z.; Xinghao, Z.; Dingxuan, K.M. Covalent organic framework-derived CoRu nanoalloy doped macro–microporous carbon for efficient electrocatalysis. J. Mater. Chem. A Mater. Energy Sustain. 2022, 10, 25272–25278. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, H.; Jung, H.; Park, C.-Y.; Kim, S.; Lee, A.; Jun, H.; Choi, J.; Han, J.W.; Lee, J. Surface conversion derived core-shell nanostructures of Co particles@RuCo alloy for superior hydrogen evolution in alkali and seawater. Appl. Catal. B Environ. Energy 2022, 315, 121554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, C.; Liu, K.; Zhu, Y.; Li, P.; Wang, Q.; Liu, B.; Chen, S.; Li, H.; Zhu, L.; Li, H.; et al. Optimizing Hydrogen Binding on Ru Sites with RuCo Alloy Nanosheets for Efficient Alkaline Hydrogen Evolution. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 61, e202113664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhou, M.; Bo, X.; Guo, L. Rapid and facile laser-assistant preparation of Ru-ZIF-67-derived CoRu nanoalloy@N-doped graphene for electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution reaction at all pH values. Electrochim. Acta 2021, 382, 138337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, K.; Wang, K.; Wang, M.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, J.; Liu, T.; Liang, E.; Li, B. Out-of-plane CoRu nanoalloy axially coupling CosNC for electron enrichment to boost hydrogen production. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2022, 318, 121890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Zhu, W.; Xu, J.; Zhang, D.; Ma, Q.; Zhao, L.; Lin, L.; Su, Q.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Q.; et al. Steering the Electronic Microenvironment of Ruthenium Sites via Boron Buffering Enables Enhanced Hydrogen Evolution under a Universal pH Range. ACS Nano 2025, 19, 7948–7961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, L.; Zhao, Y.; Zhou, H.; Li, D.; Qi, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Yu, F. Edge-oriented N-Doped WS2 Nanoparticles on Porous Co3N Nanosheets for Efficient Alkaline Hydrogen Evolution and Nitrogenous Nucleophile Electrooxidation. Small 2022, 18, 2203171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, J.; Zhang, N.N.; Zhang, C.; Sun, N.; Pan, Y.; Chen, C.; Li, J.; Tan, M.; Cui, R.; Shi, Z.; et al. Doping Ruthenium into Metal Matrix for Promoted pH-Universal Hydrogen Evolution. Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, 2200010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Luo, D.; Jiang, F.; Zhang, K.; Wang, S.; Li, S.; Zha, Q.; Huang, Y.; Ni, Y. Electronic Modulation of Metal-Organic Frameworks Caused by Atomically Dispersed Ru for Efficient Hydrogen Evolution. Small 2023, 19, 2301850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, L.; Cheng, C.; Zhou, H.; Qi, Y.; Li, D.; Cai, F.; Yu, B.; Long, R.; Yu, F. Accelerating pH-universal hydrogen-evolving activity of a hierarchical hybrid of cobalt and dinickel phosphides by interfacial chemical bonds. Mater. Today Phys. 2022, 22, 100589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, C.; Luo, M.; Song, H.; Zhang, S.; Wang, F.; Liu, X.; Huang, Z. Highly Active Porous Carbon-Supported CoNi Bimetallic Catalysts for Four-Electron Reduction of Oxygen. Energy Fuels 2023, 37, 4026–4037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, X.; Wu, Q.; Li, H.; Zeng, S.; Yao, Q.; Li, R.; Chen, H.; Zheng, Y.; Qu, K. Identifying the roles of Ru single atoms and nanoclusters for energy-efficient hydrogen production assisted by electrocatalytic hydrazine oxidation. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2023, 323, 122145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; Cheng, X.; Wu, Q. Ru-modified NiO electrocatalysts for HER: Lower energy barriers and prolonged stability. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2026, 37, 111308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z.; Duan, S.; Yao, S.; Pan, T.; Dai, D.; Gao, H. Investigation of the Electrocatalytic Activity of CuRu Alloy and Its Mechanism for Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. ChemElectroChem 2021, 8, 705–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Qian, L.; Wang, F.; Yuan, Z.; Dai, Y.; Zhang, T.; Xue, S.; Yang, D.; Qiu, F. Integrated doped-Ru electrocatalyst with excellent H adsorption–desorption and active site on hollow tubular structures for boosting efficient hydrogen evolution. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2025, 677, 1005–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Que, X.; Lin, T.; Li, S.; Chen, X.; Hu, C.; Wang, Y.; Shi, M.; Peng, J.; Li, J.; Ma, J.; et al. Radiation synthesis of size-controllable ruthenium-based electrocatalysts for hydrogen evolution reaction. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 541, 148345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Zhou, B.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Wang, X.; Wang, L.; Liu, F.; Wu, Z. Molten salt assisted to synthesize molybdenum–ruthenium boride for hydrogen generation in wide pH range. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 21568–21577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Xiao, W.; Fu, Y.; Jia, B.; Ma, T.; Wang, L. Metallic-Bonded Pt–Co for Atomically Dispersed Pt in the Co4N Matrix as an Efficient Electrocatalyst for Hydrogen Generation. ACS Nano 2022, 16, 18038–18047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Zhang, M.; Zhao, L.; Wang, L.; Cao, D.; Gong, Y. Ru doped bimetallic phosphide derived from 2D metal organic framework as active and robust electrocatalyst for water splitting. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 536, 147952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Chen, Z.; Fu, Y.; Xiao, W.; Ma, T.; Dong, B.; Chai, Y.; Wu, Z.; Wang, L. Co-Mo microcolumns decorated with trace Pt for large current density hydrogen generation in alkaline seawater. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2022, 317, 121762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Li, Q.; Xiang, H.; Wang, Y.; Yang, P.; Dai, C.; Zhang, H.; Xiao, W.; Wu, Z.; Wang, L. Hierarchical porous NiFe-P@NC as an efficient electrocatalyst for alkaline hydrogen production and seawater electrolysis at high current density. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2023, 10, 1493–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Huang, H.; Wu, X.; Yuan, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, D.; Qin, Y.; Lai, J.; Wang, L. Mn-doped Ru/RuO2 nanoclusters@CNT with strong metal-support interaction for efficient water splitting in acidic media. Compos. Part B Eng. 2022, 242, 110013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Yao, R.; Zhao, Q.; Li, J.; Liu, G. La-RuO2 nanocrystals with efficient electrocatalytic activity for overall water splitting in acidic media: Synergistic effect of La doping and oxygen vacancy. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 439, 135699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Lian, Z.; Wei, B.; Li, Y.; Bondarchuk, O.; Zhang, N.; Yu, Z.; Araujo, A.; Amorim, I.; Wang, Z.; et al. Strong Electronic Coupling between Ultrafine Iridium–Ruthenium Nanoclusters and Conductive, Acid-Stable Tellurium Nanoparticle Support for Efficient and Durable Oxygen Evolution in Acidic and Neutral Media. ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 3571–3579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.-M.; Zhang, J.; Ding, L.-W.; Du, Z.-Y.; He, C.-T. Metal-organic frameworks derived transition metal phosphides for electrocatalytic water splitting. J. Energy Chem. 2022, 68, 494–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Song, X.; Liu, J.; Shen, T.; Wu, S.; Ouyang, H.; Feng, Y. CoRu Alloy/Ru Nanoparticles: A Synergistic Catalyst for Efficient pH-Universal Hydrogen Evolution. Catalysts 2025, 15, 1106. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121106

Song X, Liu J, Shen T, Wu S, Ouyang H, Feng Y. CoRu Alloy/Ru Nanoparticles: A Synergistic Catalyst for Efficient pH-Universal Hydrogen Evolution. Catalysts. 2025; 15(12):1106. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121106

Chicago/Turabian StyleSong, Xinrui, Jiaqi Liu, Tianzhan Shen, Sirui Wu, Haibo Ouyang, and Yongqiang Feng. 2025. "CoRu Alloy/Ru Nanoparticles: A Synergistic Catalyst for Efficient pH-Universal Hydrogen Evolution" Catalysts 15, no. 12: 1106. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121106

APA StyleSong, X., Liu, J., Shen, T., Wu, S., Ouyang, H., & Feng, Y. (2025). CoRu Alloy/Ru Nanoparticles: A Synergistic Catalyst for Efficient pH-Universal Hydrogen Evolution. Catalysts, 15(12), 1106. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121106